Abstract

Walnut glutelin is a storage protein of high nutritional value, but its composition, structure, and applications in foods have not been fully studied. In this work, walnut glutelin was obtained using the Osborne fractionation method and identified by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. The main components of the extracted walnut glutelin were legumin B-like, 11S globulin-like, 11S globulin seed storage protein Jug r 4, and 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like. Besides, the adsorption behaviors of walnut glutelin and its linear as well as nonlinear rheological properties at the air–water interface were investigated. Results showed that at a low concentration of 10 μg/mL (<critical aggregation concentration), walnut glutelin reduced the interfacial tension to 59 mN/m after adsorption, permeation, and rearrangement at the air–water interface, suggesting that walnut glutelin has the ability to stabilize the air–water interface. Meanwhile, the solid-like interfacial film formed by walnut glutelin exhibited a high elastic modulus (35–45 mN m−1) and good mechanical properties over the tested amplitudes (8–40%). These findings demonstrate that walnut glutelin is a promising stabilizer for foamed food products.

1 Introduction

With the rapid growth of the global population and the improvement of people’s living standards, there has been an increasing demand for protein [1]. The production of animal protein not only requires a substantial consumption of water, land, and feed resources but also leads to greenhouse gas emissions [2]. Moreover, excessive consumption of animal protein may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In contrast, plant protein has numerous advantages, including diverse sources, environmental sustainability, and health safety [3]. It is critical to explore high-quality plant protein to meet the increasing demand.

Walnut (Juglans regia L.) is an extensively cultivated oilcrop [4], which is rich in lipid (a content ranging from 62.3 to 73.6%) [5] and protein (a content ranging from 18 to 24%) [5]. The walnut production in China reached approximately 5.4 million tons in 2021 (data sources: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/zhzs/509875.jhtml). The residual cake or meal generated after oil production is mainly used as animal feed or directly discarded, leading to a waste of resources [6,7]. Walnut meal contains a high content of protein (∼53%) [8], and the amino acid composition is well-balanced [7]. The walnut protein exhibits superior quality, along with high nutritional and biological values, indicating that it is a high-quality source of plant protein [4,9]. Since glutelin accounts for approximately 70% of the total walnut proteins [10], it has limited water solubility under neutral pH, and its functionalities have not been fully exploited.

Several studies have attempted to elucidate the composition, structure, and functionalities of walnut protein. The sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) results showed that walnut protein is usually linked by two subunits with relative molecular weights (MWs) ranging from 30 to 35 kDa (pI 5.5–7.5) and 17 to 22 kDa (pI 9.0–10.0) through disulfide bonds. Further identification via MALDI-TOF/TOF-MS found that the main components of walnut proteins were vicilin and legumin-like proteins [11]. In the pH range (3–7) relevant to food applications, the solubility of walnut protein remains lower than 30% [8], and the emulsifying activity index (EAI) and the emulsifying stability index (ESI) are less than 9.2 m2 g−1 and 22 min, respectively [12]. Yan et al. [12] modified walnut protein by phosphorylation, raising its EAI to 41.7 m2 g−1 and its ESI to 149 min. Zhu et al. [13] treated the walnut protein with ultrasound, and its EAI and ESI increased by 26 and 41%, respectively. Nevertheless, the role of walnut protein, especially glutelin, in stabilizing the air–water interface is still relatively limited.

This study identified the components of walnut glutelin prepared by the Osborne fractionation method by using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and then investigated the structure of walnut glutelin through FTIR spectroscopy, zetasizer, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Finally, interfacial dilatational rheology was employed to elucidate the interfacial properties of walnut glutelin. The results provide fundamental data that support the high-value utilization of walnut protein in food applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The walnut meal with a residual lipid content of 12.84 ± 0.65% was obtained from Guanghua Modern Agriculture Co. (Xinjiang, China). All reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2 Preparation of walnut glutelin

2.2.1 Removal of residue lipids in walnut meal

The residue lipids in the walnut meal were removed using a subcritical fluid extractor (Henan Sub-critical Extraction Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Anyang, Henan, China). n-Hexane was used as the solvent, and the process was carried out at 45°C and 0.52 MPa pressure for 40 min. This process was repeated four times until the content of residual lipids in the walnut meal was below 1%.

2.2.2 Extraction of walnut glutelin using the Osborne fractionation method

Extraction of walnut glutelin was carried out using the Osborne fractionation method with slight modifications [10]. The details are shown in Figure 1. The isolated walnut protein was extracted by alkaline dissolution (pH 11) and acid precipitation (pH 4.5). Subsequently, the isolated protein was sequentially eluted with ultrapure water, 1 M NaCl solution, and 70% ethanol solution to remove albumin, globulin, and prolamin. The elution process for each solvent involved mixing the isolated protein with solvent at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v), continuous magnetic stirring at 25°C for 2 h, centrifugation at 10,000×g at 4°C for 10 min, and collection of the resulting precipitate. Then, the precipitate was washed three times by repeating the procedure. Finally, the remaining walnut glutelin precipitate was thoroughly mixed with ultrapure water in a ratio of 1:4 (w/v) and stirred for 1 h at 25°C to ensure complete mixing before freeze-drying treatment.

Schematic diagram of graded extraction of walnut glutelin.

2.3 Determination of the basic component of defatted walnut meal and walnut glutelin

The contents of crude protein, fat, ash, and moisture were measured according to methods described in AOAC as 2001.11, 2003.05, 923.03, and 934.01, respectively [14,15]. Briefly, the contents of crude protein and lipid were determined using the Kjeldahl method and Soxhlet extraction, respectively. The carbohydrate content was determined by subtracting the mass of all other components from the sample.

2.4 Reducing and non-reducing SDS-PAGE

The SDS-PAGE commercial kit was utilized for the analysis following the protocol described in a previous study [16]. Sampling buffer (β-mercaptoethanol was not used in non-reducing SDS-PAGE) was mixed with the samples (2 mg mL−1) at a ratio of 1:4 (v:v), heated in a boiling water bath for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 3,500×g for 5 min. An electrophoresis gel containing 5% stacking gel and 12% resolving gel was configured and subjected to electrophoresis at 150 V for 60 min.

2.5 Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

2.5.1 Trypsin digestion of the protein

Samples taken from –80°C are processed with four times their volume of lysis buffer (1% SDS and 1% protease inhibitor) for sonication lysis. After centrifugation at 4°C and 12,000×g for 10 min, the supernatant is transferred to another tube for determination of protein concentration using the BCA assay. Equal amounts of protein from each sample are adjusted with lysis buffer to the same volume, mixed with five volumes of pre-chilled acetone, and precipitated at −20°C for 2 h. After centrifuging at 4,500×g for 5 min, the sediment is washed 2–3 times with pre-chilled acetone. After drying, the sediment is resuspended in 200 mM TEAB using sonication and digested overnight with trypsin at a 1:50 ratio (enzyme: protein, w/w).

2.5.2 LC-MS/MS analysis and database searching

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using the method of Yang et al. [17] with slight modifications. Peptides are dissolved in mobile phase A and separated using an EASY-nLC 1200 UHPLC system. The mobile phase A is an aqueous solution containing 0.1% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile, while the mobile phase B contains 0.1% formic acid and 90% acetonitrile. The LC gradient is configured as follows: 0–68 min: 6–23% B; 68–82 min: 23–32% B; 82–86 min: 32–80% B; 86–90 min: 80% B. The flow rate is set as 500 nl/min. After separation, peptides are ionized in an NSI ion source and analyzed using an Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer. The ion source voltage is set at 2,300 V, and the FAIMS compensation voltage is adjusted accordingly. Both parent ions and fragment ions are detected and analyzed with high resolution by the Orbitrap. The MS1 scan range is 400–1,200 m/z with a resolution of 60,000; the MS2 scan starts at 110 m/z with a resolution of 15,000, and TurboTMT is disabled. Data acquisition was performed using a data-dependent scanning (DDA) protocol, selecting the 25 most intense parent ions for HCD fragmentation with 27% collision energy. To optimize mass spectrometry efficiency, the automatic gain control is set at 100%, the ion threshold is 50,000 ions/s, the maximum injection time is set to auto, and the dynamic exclusion time for MS/MS scans is 20 s to prevent repetitive scanning of parent ions.

2.6 Determination of the particle size, ζ-potential, and microstructure observation

Walnut glutelin was dispersed in ultrapure water and stirred at 25°C for 2 h to prepare the stock solution (10 mg mL−1). Equal volumes of the solution were taken, and their pH values were adjusted to 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0, respectively. The particle size of walnut glutelin at different pH values was determined by a Mastersizer 3000 (Malvern, UK). The refractive index of the protein and continuous phase was set as 1.45 and 1.33, respectively. Subsequently, walnut glutelin solutions with various pH values were diluted to 1.0 mg/mL with the same pH buffer, and their ζ-potentials were measured using a Zetasizer (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) [18]. The morphology of walnut glutelin was captured by SEM (GeminiSEM 300, ZEISS, Germany). The powder of walnut protein was attached to a substrate with conductive adhesive and sputter-coated with gold for 45 s [19].

2.7 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

Following the method reported by Yan and Zhou [20], with slight modification, 1 mg of protein sample was mixed with 50 mg of potassium bromide (KBr) and compressed into a disc. FTIR spectroscopy (8400S, Shimadzu, Japan) was used to conduct scans in the range of 4,000–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 2 cm−1, with a total of 32 scans. The spectra file was imported into the Peakfit software, and the amide band I (1,700–1,600 cm−1) was selected for peak fitting. There are five points where the second derivative of the spectrum of amide band I is zero, which are attributed to α-helix (1,660 cm−1), β-turn (1,680 cm−1), random coil (1,640 cm−1), and β-sheet (1,620 and 1,690 cm−1), respectively [20].

2.8 Critical aggregation concentration (CAC)

The CAC of walnut glutelin was determined using the methods of Niu et al. [21] and Tizzotti et al. [22] with minor modifications. The protein solution was prepared in a 20 mM phosphate buffer solution at pH 7.0 within a concentration range of 0.1–3,000 μg/mL. A 12 mM pyrene solution (m/v) was prepared in acetone, and then 1 μL of this solution was mixed with 2.4 mL of the protein solution. The resulting mixture was thoroughly mixed, and the emission spectrum was recorded using a fluorescence spectrometer (F-7000, Hitachi, Japan). The excitation wavelength, excitation slit width, emission slit width, and excitation voltage were set to 334 nm, 5 nm, 2.5 nm, and 700 V, respectively. The intensity ratio between the first and third peaks in the emission spectrum (I 374/I 384) was plotted as a function of protein concentration to determine its inflection point, which could be used to predict the CAC value of walnut glutelin.

2.9 Interfacial adsorption behaviors

By referring to the method proposed by Yang et al. [23] and Peng et al. [24], the surface tension of walnut glutelin below the CAC as a function of time at the air–water interface was measured using a drop tensiometer (Tracker, Teclis, France). A rising droplet with a volume of 6 mm3 was injected using a G18 bent needle, and a continuous 3 h static adsorption experiment was conducted at 25°C. The Young–Laplace equation was employed to fit the drop profile and calculate its surface tension (γ). The surface pressure (π) was calculated using equation (1):

where γ 0 is the surface tension of the pure solvent, and γ represents the surface tension of the samples over time.

By monitoring the evolution of surface tension over time, valuable insights pertaining to several stages of the adsorption process can be obtained. When the stage is diffusion-controlled adsorption, the Ward and Tordai model diffusion rate can be used to describe the change in π with time (equation (2)) [25]:

where C 0 is the initial protein concentration, K B is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, D is the diffusion coefficient, and t is the adsorption time. Based on equation (2), the plot of π–t 1/2 is linear, and its slope can be used to evaluate the diffusion rate (K diff).

After the protein diffuses onto the interface, it begins to permeate and rearrange at the interface. This process can be calculated using the following first-order equation (equation (3)) [25]:

The final value of the surface pressure is denoted π f , while π 0 represents the initial value of the surface pressure, and π t represents the surface pressure at any given time. k i denotes the first-order rate constant. This equation typically yields two linear regions. The slopes of these two regions represent the protein penetration constant (K p) and the rearrangement constant (K r) at the interface.

2.10 Interfacial dilatational rheology

The method of interfacial dilatational rheology testing was moderately modified, as reported by Yang et al. [26]. In order to ensure sufficient protein adsorption at the air–water interface, static adsorption was performed for a duration of 3 h while maintaining a constant drop volume of 6 mm3. After this static adsorption stage, amplitude and frequency sweeps were conducted. For amplitude sweep, the fixed frequency was set to 0.1 Hz, while the amplitudes were configured as 5, 8, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 40%. Here, it is worth mentioning that when the amplitude was 40%, the bond number of the compression drop was larger than 0.1, and the standard error was within the range of ±0.002. These reflected that the obtained data at the deformation of 40% were accurate. Therefore, the data at amplitudes of 5–40% were recorded in this work. Each amplitude underwent five oscillation cycles, followed by pausing for 50 s. With regard to frequency sweep, the amplitude was consistently maintained at a fixed value of 8%, and subsequent measurements were conducted at frequencies of 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.05, and 0.1 Hz. By amplitude sweep experiments, the Lissajous plot can be generated by plotting the surface pressure (π, the surface tension during oscillation minus the surface tension after 3 h of adsorption) against the deformation ((V–V 0)/V 0). Here, V and V 0 represent the volume of the deformed and nondeformed interface, respectively.

2.11 Statistical analysis

The experiments were repeated three times, and the data are presented as mean ± standard error. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple comparison test (P < 0.05). Graphs were plotted using Origin 2022 software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Basic components, appearance, and microstructure of walnut glutelin

The basic composition of the defatted walnut meal is shown in Table 1. It mainly consisted of proteins (50.98 ± 0.84%, N × 5.3), carbohydrate (33.42 ± 0.54%), moisture (8.28 ± 0.14%), ash (6.71 ± 0.13%), and lipid (0.61 ± 0.31%). These results showed that the walnut meal contains a high content of protein. Our study found components similar to the results reported by Yan and Zhou. Specifically, Yan and Zhou reported that defatted walnut flour (with pellicles) contained 55.5 ± 2.65% protein, 29.3 ± 1.05% carbohydrate, and 8.59 ± 1.35% moisture [20]. The extract obtained by Osborne fractionation had a protein content of 80.42 ± 0.70% (N × 5.3), revealing that the purity of walnut glutelin is relatively high after graded extraction and purification. After Osborne fractionation, the walnut glutelin exhibited a pale yellow color (Figure 2a). The microstructure of walnut glutelin showed irregular blocky aggregates, and the surface appeared loose (Figure 2b).

Basic composition of defatted walnut meal and walnut glutelin

| Content | Protein (wt%) | Carbohydrate (wt%) | Moisture (wt%) | Ash (wt%) | Lipid (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defatted walnut meal | 50.98 ± 0.84 | 33.42 ± 0.54 | 8.28 ± 0.14 | 6.71 ± 0.13 | 0.61 ± 0.31 |

| Walnut glutelin | 80.42 ± 0.70 | 14.28 ± 0.40 | 4.36 ± 0.15 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.47 ± 0.23 |

Visual appearance (a) and SEM images (b) and (c) of walnut glutelin.

3.2 Subunit composition of walnut glutelin

Figure 3 exhibits the non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE of walnut glutelin. Under non-reducing conditions, the predominant band of walnut glutelin was located at 50 kDa MW, while the minor bands displayed MWs of 150, 37, and 32 kDa. The non-reducing and reducing SDS-PAGE result revealed that reduction split the band at the MW of approximately 50 kDa into two distinct subunits (17–20 and 30–35 kDa), suggesting that walnut glutelin consists of a basic subunit (17–20 kDa) and an acidic subunit (30–35 kDa) connected by disulfide bonds. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting similar results. The main protein bands of walnut glutelin have MWs of 20.1 and 30 kDa [27].

Non-reducing (a) and reducing (b) SDS-PAGE of walnut glutelin.

3.3 Protein composition of walnut glutelin

As shown in Table 2, the predominant proteins identified from walnut meal and walnut glutelin included legumin B-like (A0A2I4GEH1), 11S globulin-like (A0A2I4F6R4), 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like (A0A2I4EG83), and 11S globulin seed storage protein Jug r 4 (Q2TPW5). In particular, legume B-like was the most abundant protein in both walnut glutelin and defatted walnut meal. Legumin B-like is a member of the 11S globulin family and serves as a major seed storage protein, playing a critical role in nutrient delivery during seed development and germination [28]. In addition, several other proteins were identified within walnut glutelin, including small amounts of 2S seed storage albumin protein (P93198), Vicilin Car i 2.0101 (A0A2I4DYF1), Vicilin Jug r 6.0101 (A0A2I4E5L6), and Vicilin Jug r 2.0101 (Q9SEW4), and oil body-associated protein 2A-like (A0A2I4FEE8).

Major protein components in walnut meal (WMP) and walnut glutelin (GLU)

| No. | Accession | Protein description | Mw (kDa) | WMP | GLU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A0A2I4GEH1 | Legumin B-like | 55.86 |

|

|

| 2 | P93198 | 2S seed storage albumin protein | 16.37 |

|

|

| 3 | A0A2I4F6R4 | 11S globulin-like | 58.29 |

|

|

| 4 | A0A2I4EG83 | 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like | 54.31 |

|

|

| 5 | Q2TPW5 | 11S globulin seed storage protein Jug r 4 | 58.14 |

|

|

| 6 | A0A2I4DYF1 | Vicilin Car i 2.0101 | 94.40 |

|

|

| 7 | A0A2I4E5L6 | Vicilin Jug r 6.0101 | 57.40 |

|

|

| 8 | A0A2I4F669 | 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like | 53.44 |

|

|

| 9 | A0A2I4GEI2 | Legumin B-like | 55.83 |

|

|

| 10 | Q9SEW4 | Vicilin Jug r 2.0101 (Fragment) | 69.99 |

|

|

| 11 | A0A2I4FEE8 | Oil body-associated protein 2A-like | 28.02 |

|

|

Note: The bars on the right side of the table indicate the normalized percentage values calculated from the LC-MS intensity data after normalization procedures.

As shown in Figure 4, the protein composition of defatted walnut meal primarily consisted of 66.5% 11S globulin, 17.1% 2S albumin, 15.9% 7S globulin, and 0.5% oil body protein; in contrast, that of walnut glutelin comprised 72.9% 11S globulin, 19.6% 7S globulin, 7.1% 2S globulin, and 0.4% oil body protein. After Osborne fractionation, the percentage content of 2S albumin observably decreased from 17.1 to 7.1%, while that of 7S globulins increased from 15.9 to 19.6%, and that of 11S globulin increased from 66.5 to 72.9%. These variations could be attributed to the differential solubility of different solvent systems toward different protein fractions during Osborne fractionation.

Protein composition of defatted walnut meal (a) and walnut glutelin (b).

By using the Protein BLAST function on NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) [29], we compared the four major proteins (11S globulin-like (Juglans regia), 11S globulin seed storage protein Jug r 4 (Juglans regia), 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like (Juglans regia), and vicilin Jug r 2.0101 (Juglans regia)) in walnut glutelin with the most abundant legume B-like (Juglans regia). The comparison results are presented in Table 3, indicating significant sequence similarity primarily within the 11S protein family. However, it should be noted that vicilin Jug r 2.0101 (Juglans regia), which belongs to the distinct 7S protein family, showed some variations compared with the above-mentioned members of the 11S protein family.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of legumin B-like [Juglans regia], the most abundant walnut glutelin, with those of other major proteins in walnut glutelin

| Description | Total score | Query cover (%) | E value | Per. ident | Acc. Len |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legumin B-like (Juglans regia) | 1,001 | 100 | 0 | 100.00 | 490 |

| 11S globulin-like (Juglans regia) | 507 | 98 | 0 | 51.87 | 511 |

| 11S globulin seed storage protein Jug r 4 (Juglans regia) | 466 | 97 | 5.00 × 10−165 | 51 | 507 |

| 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like (Juglans regia) | 367 | 87 | 2.00 × 10−126 | 43.37 | 481 |

| Vicilin Jug r 2.0101 (Juglans regia) | 38.5 | 63 | 2.00 × 10−06 | 19.58 | 789 |

Note: Total score reflects the overall similarity of two protein sequences at the amino acid level, with a higher value indicating a greater similarity. Query Cover represents the percentage of the query sequences matched in the comparison results. E value indicates the number of comparison results expected to have the same or better scores, with a lower value indicating a lower probability for the appearance of the result and a higher level of confidence. Per. identity represents the percentage of identical sites in two sequences in a sequence comparison. The comparative data in Table 3 were obtained using the Protein BLAST function on NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Table 4 shows that the legumin B-like (Juglans regia) from walnut glutelin exhibited significant sequence similarities to legumin B-like proteins from Carya illinoinensis, 11S globulin subunit beta from Morella rubra, and an unnamed protein product from Linum tenue in the NCBI protein database. These results suggested potential structural and functional similarities among these proteins. For protein-related structural analysis, the Uniprot database (https://www.uniprot.org) was used to retrieve the primary structures of walnut proteins, which were then entered into the ProtScale tool (https://web.expasy.org/protscale/) to analyze the water affinity properties of the proteins.

Amino acid sequences of legumin B-like (Juglans regia) in walnut glutelin compared with the NCBI protein database for amino acid sequencing

| Accession | Description | Total score | Query cover (%) | E value | Per. ident (%) | Acc. Len |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XP_018842296.1 | Legumin B-like (Juglans regia) | 1,001 | 100 | 0.0 | 100 | 490 |

| XP_042942791.1 | Legumin B-like (Carya illinoinensis) | 845 | 97 | 0.0 | 93.54 | 492 |

| KAB1219252.1 | 11S globulin subunit beta (Morella rubra) | 691 | 98 | 0.0 | 73.40 | 487 |

| CAI0558948.1 | Unnamed protein product (Linum tenue) | 549 | 96 | 0.0 | 55.81 | 473 |

Note: The comparative data in Table 4 were obtained using the Protein BLAST function on NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Legumin B-like (Juglans regia) is a member of the 11S seed storage protein (globulin) family, which is known as a storage globulin widely distributed in various plant species, particularly in legume seeds. Each legumin B-like protein consists of a hexameric structure formed by an acidic and basic chain derived from a single precursor and connected through disulfide bonds. According to the UniProtKB sequence prediction (Figure 5a), the amino acid residues at positions 123–137 of legumin B-like (Juglans regia) are polar residues (highlighted in green), while those at positions 209–233 represent both basic and acidic residues (highlighted in red). In addition, cupin type-1 domains are present at positions 48–264 and 317–466 (highlighted in yellow) within the protein structure. The cupin superfamily refers to proteins with specific barrel-shaped structural domains [30]. To assist the structure–function prediction, the Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale was used to calculate the hydrophobicity score of each amino acid residue within the legumin B-like (Juglans regia) protein sequence, with positive values indicating relative hydrophilicity and negative values indicating relative hydrophobicity. As shown in Figure 5b, most amino acids of legumin B-like (Juglans regia) had relatively high hydrophobicity scores, which contribute significantly to the storage of nitrogen elements during seed development. As depicted in Figure 5c, the crystal structure of legumin B-like (Juglans regia) exhibited an MW of approximately 55.86 kDa.

Primary structure (a), protein sequence water affinity (b), and three-dimensional structure (c) of legumin B-like (Juglans regia). The data presented in the figure were obtained from the Uniprot database, a reputable source for scientific information (https://www.uniprot.org).

The 2S seed storage protein (Juglans regia) is a protein with an MW of approximately 12 kDa (measured by the MALDI-TOF method), consisting of a ∼4 kDa small subunit and an ∼8 kDa large subunit [31]. As shown in Figure 6a, the small subunit spanned the positions at 32–57, while the large subunit occupied positions at 72–135. Disulfide bonds at positions 39 ↔ 88 and 52 ↔ 77 connected the two peptide chains, while within the large subunit, intrachain disulfide bonds connected positions 78 ↔ 125 and 90 ↔ 132 to ensure the stability of the walnut 2S protein. According to Figure 6b, hydrophobicity was observed at most amino acid positions in walnut 2S seed storage protein. However, compared with 11S legumin B-like, 2S seed storage protein contained a higher proportion of hydrophilic amino acids, making it relatively more hydrophilic. The crystal structure of 2S seed storage albumin protein (Juglans regia) had an MW of approximately 16.37 kDa (Figure 6c).

Primary structure (a), protein sequence water affinity (b), and three-dimensional structure (c) of 2S seed storage albumin protein (Juglans regia). The data presented in the figure were obtained from the Uniprot database, a reputable source for scientific information (https://www.uniprot.org).

The Vicilin Car i 2.0101 (Juglans regia) protein, which belongs to the 7S seed storage protein family, exhibited a composition of basic and acidic residues at positions 177–214 and 346–376 (highlighted in red in Figure 7a). Furthermore, the amino acids at positions 383–537 and 582–752 form the cupin type-1 domain. Based on the Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity scale calculation, this protein demonstrates high hydrophobicity across most sites, which plays a crucial role in the seed protein storage process. The crystal structure of Vicilin Car i 2.0101 (Juglans regia) had an MW of approximately 94.40 kDa (Figure 7c).

Primary structure (a), protein sequence water affinity (b), and three-dimensional structure (c) of Vicilin Car i 2.0101 (Juglans regia). The data presented in the figure were obtained from the Uniprot database, a reputable source for scientific information (https://www.uniprot.org).

3.4 Secondary structure of walnut glutelin

The infrared spectra of walnut glutelin are exhibited in Figure 8. The amide I band at 1,700–1,600 cm–1 primarily corresponds to the C═O stretching vibration of the protein, which is directly related to its main chain conformation. By fitting the infrared data, walnut glutelin showed a secondary structure composition of approximately 24.17 ± 1.23% of α-helix, 34.91 ± 1.93% of β-sheet, 20.90 ± 0.27% of β-turn, and 20.02 ± 1.02% of the random coil, with β-sheet as the predominant secondary structure, which is consistent with the report by Yan and Zhou [20].

Infrared spectra of walnut glutelin (a) and infrared spectral split-peak fitting (b).

3.5 Particle size, ζ-potential, and isoelectric point of walnut glutelin

As shown in Figure 9(b), walnut glutelin possessed a positive charge at pH 4.0 and a negative charge at pH 6.0, suggesting that its isoelectric point was in the range of 4–5. Based on the previous sequence analysis of the main components of walnut glutelin, namely legumin B-like and 11S globulin seed storage protein 2-like, it was shown that the predicted isoelectric points for these proteins were indeed within the range of 4–5. Figure 9(a) shows the particle size distribution of walnut glutelin under different pH conditions. As the shift of pH from neutral to the isoelectric point, there is an increase in the particle size of walnut glutelin. However, as the pH further decreases from the isoelectric point attachment to 2, there is a rapid decrease in the particle size due to increased electrostatic repulsion between walnut glutelin molecules.

Particle size (a) and ζ-potential (b) of walnut glutelin at different pH values.

3.6 Air–water interfacial adsorption behaviors of walnut glutelin

CAC is one of the important parameters in investigating the aggregation behavior of biological macromolecules [32]. With regard to a polymeric self-assembling system, CAC can estimate the lowest concentration that fabricates aggregates [33]. Therefore, in this work, we used the term CAC to discuss the influence of walnut glutelin concentration on its aggregation behavior. The pyrene fluorescence probing method is one of the commonly utilized approaches to capture the CAC of amphiphilic substances [22]. Here, we adopted this method to investigate the CAC of walnut glutelin in the aqueous phase. Formation of protein aggregates was observed when the concentration exceeded the CAC, with the hydrophobic region effectively trapping pyrene molecules and resulting in a significant decrease in I 374/I 384 [34]. This inflection point represents the CAC of walnut glutelin. As depicted in Figure 10, the CAC of walnut glutelin was 15.85 μg mL−1. Therefore, we adopted a concentration of 10 μg mL−1 (below the CAC) to investigate the interfacial adsorption kinetics, viscoelasticity, and mechanical properties of walnut glutelin at the air/water interface, which will be discussed in the following sections.

Variation in the I 374/I 384 fluorescence intensity ratio with walnut glutelin concentration.

The adsorption process of proteins at the air–water interface can be classified into several stages, including diffusion toward the interface, penetration, and structural unfolding at the interface, followed by rearrangement [25]. These stages could be determined by monitoring the changes in surface tension or surface pressure as a function of time. As depicted in Figure 11a, an obvious lag phase was observed before 2,400 s. This might be because the adsorption of walnut glutelin (10 μg mL−1) at the air–water interface during this period was very limited, resulting in no noticeable decrease in surface tension. Between 2,400 and 6,000 s, the surface tension decreased rapidly, implying that a large amount of walnut glutelin attached to the air–water interface. Based on the plot of π–t 1/2 (Figure 11b), a straight line was observed during this stage, reflecting that this adsorption process was controlled by diffusion. By calculating the slope of this plot, we concluded that the walnut glutelin diffused to the air–water interface with a diffusion rate (K diff) of 0.341 mN m−1 s−0.5. After 6,000 s, the adsorption rate gradually decreased, mainly resulting from the penetration, unfolding, and rearrangement. Here, the penetration and rearrangement process of proteins can be monitored using first-order equations [35], and the results are displayed in Figure 11c. The slope (K p) of the first linear region (6,000–8,600 s) corresponds to the penetration process, and the slope (K r) of the second linear region (8,600–10,800 s) corresponds to the rearrangement rate. The walnut glutelin possessed a permeation rate (K p) of 3.45 × 10−4 s−1, followed by a rearrangement rate (K r) of 1.36 × 10−3 s−1. The K r was larger than K p, illustrating that the rearrangement process of walnut glutelin was faster than the penetration process.

Adsorption process of walnut glutelin at the air–water interface. (a) Changes in interfacial tension with adsorption time, (b) the curve of surface pressure (π) with the square root of adsorption time (t 1/2), and (c) fitting of π during the late adsorption stage according to equation (3).

3.7 Interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

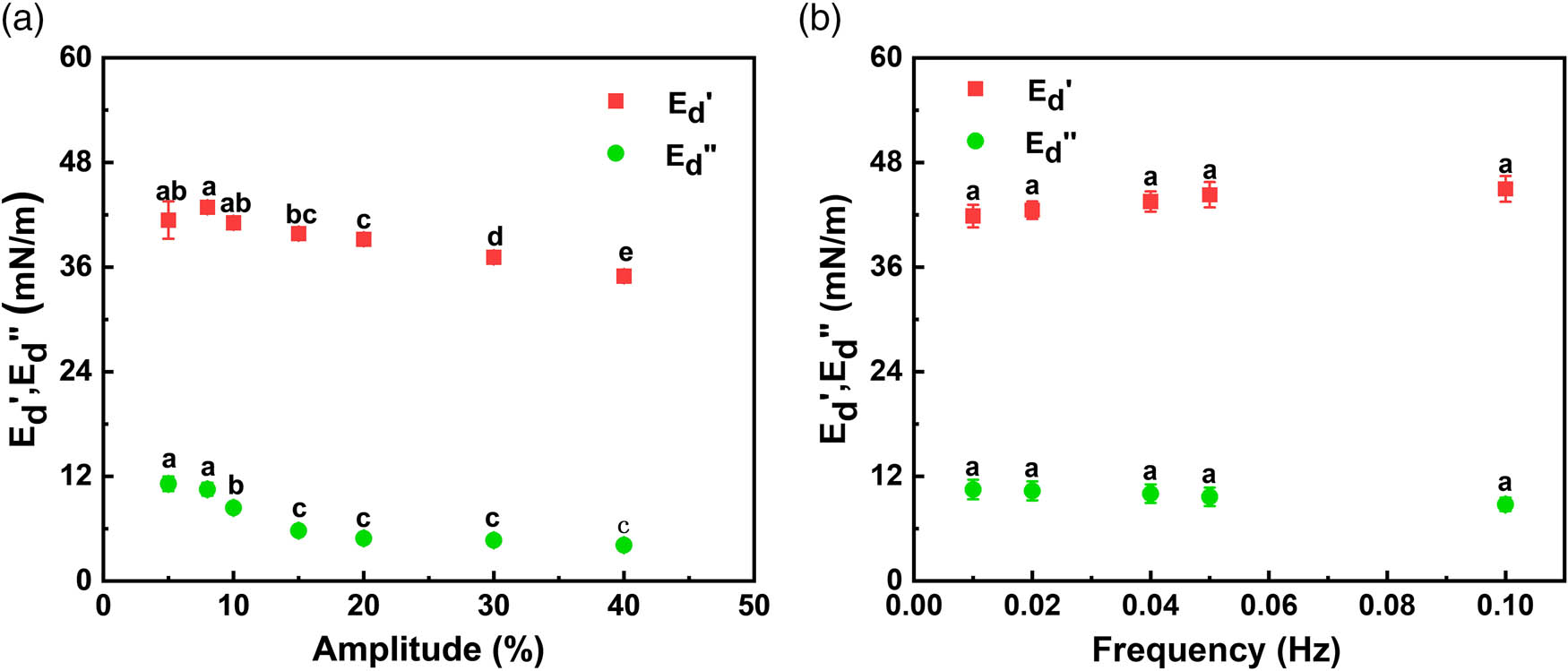

Figure 12 displays the elastic modulus (

Variations in the elastic modulus (

For frequency sweep (Figure 12b), the results revealed a weak dependence of

The Lissajous plot is a powerful tool to evaluate the mechanical properties of interface films and analyze interfacial interactions among adsorbed proteins [39]. These properties of the surface film can be visualized in two ways. First, the angle between the curve and transverse axis is correlated with surface film mechanics. A steeper curve (closer to the vertical axis) indicates greater stiffness. Second, the curve shape is closely associated with the viscoelastic properties of the surface film: a straight line represents fully elastic responses; a circular curve indicates fully viscous responses; a symmetric oval curve represents linear viscoelastic responses; and a non-symmetric ellipse curve stands for non-linear viscoelastic responses [39,40]. By observing the asymmetry of the curve, the interaction among adsorbed protein molecules can be conjectured. At 8–10% deformation, the Lissajous plot (Figure 13) showed a symmetric and very narrow shape, indicating a linear viscoelastic behavior with an elastic-dominated response. At amplitudes of 15–30%, the loops exhibited a minor and narrow asymmetry, and the maximum π values of the compression part were slightly larger than those of the extension part. This indicated that the interface covered by walnut glutelin still displayed a nearly linear and predominantly elastic behavior, even when the amplitude was as high as 30%.

Lissajous plots of walnut glutelin with concentration below the CAC at different amplitudes.

Meanwhile, walnut glutelin could form an interface network structure with high resistance against larger deformations. As the amplitude increased to 40%, the asymmetry of the plot increased, indicating a nonlinear viscoelastic behavior. For the expansion stage (upper loop), from the left-bottom corner to the right-upper corner, the interfacial film first showed an elastic-dominated response. When the tangential modulus (the slope at each point of the loop) gradually decreased, the interface displayed an intra-cycle strain softening behavior. This reflected that the interfacial structure was slightly disrupted. The elastic component began to diminish, and the viscous component started to dominate. During the compression stage (lower loop), intra-cycle strain hardening occurred as indicated by a higher maximum π in compression (point B in Figure 13) compared with the maximum π in expansion (point A in Figure 13). This phenomenon might be because the dense protein clustered regions were formed and began to jam upon compression. All of these reflected that the walnut glutelin could form a viscoelastic solid-like interfacial structure with an elastic-dominated response, probably resulting from the strong in-plane interaction among adsorbed glutelin.

4 Conclusion

In this work, the composition, structure, interfacial adsorption kinetics, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin were comprehensively discussed. The walnut glutelin is composed of legumin B-like and 11S globulin seed storage protein, which consists of a basic subunit (17–20 kDa) and an acidic subunit (30–35 kDa) linked by disulfide bonds. Walnut glutelin showed a β-sheet content of 34.91, which was the predominant secondary structure. The isoelectric point of walnut glutelin was approximately 4.0–5.0. With regard to interfacial properties, walnut glutelin exhibited a good ability to decrease air–water interfacial tension even at a low concentration of 10 μg/mL (below the CAC). Walnut glutelin possessed the ability to form a viscoelastic solid-like interfacial layer with an elastic-dominated response. This probably resulted from the higher β-sheet content in the secondary structure of glutelin, which might contribute to the stronger in-plane interaction among adsorbed glutelin and lead to the formation of interface network structures with high resistance against larger deformations. This study provides crucial information for the functional performance of walnut glutelin in foam systems.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022A02004), the Key Research Projects of Hubei Province (2023BBB068), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD2100400 and 2023YFD2100402). The authors thank the financial support from the “Young Talents of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences” and “Wuhan Yellow Crane Talents.”

-

Author contributions: Jisong Zhou: investigation, formal analysis, validation, data curation, writing original draft, and visualization. Jing Yang: formal analysis, methodology. Jiaqi Shao: formal analysis and methodology. Ping Wu: writing review and editing. Xiaoli Yang: writing review and editing. Qianchun Deng: conceptualization and supervision. Weiping Jin: conceptualization, methodology, writing review and editing, and supervision. Dengfeng Peng: conceptualization, methodology, writing review and editing, supervision, and project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Yang J, Kornet R, Ntone E, Meijers MGJ, van den Hoek IAF, Sagis LMC, et al. Plant protein aggregates induced by extraction and fractionation processes: Impact on techno-functional properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;155:110223.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110223Search in Google Scholar

[2] Sim SY, Srv A, Chiang JH, Henry CJ. Plant proteins for future foods: a roadmap. Foods. 2021;10:1967. 10.3390/foods10081967.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Sá AGA, Moreno YMF, Carciofi BAM. Plant proteins as high-quality nutritional source for human diet. Trends Food Sci Technology. 2020;97:170–84.10.1016/j.tifs.2020.01.011Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wen C, Zhang Z, Cao L, Liu G, Liang L, Liu X, et al. Walnut protein: a rising source of high-quality protein and its updated comprehensive review. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71:10525–42.10.1021/acs.jafc.3c01620Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Martínez ML, Labuckas DO, Lamarque AL, Maestri DM. Walnut (Juglans regia L.): genetic resources, chemistry, by-products. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:1959–67.10.1002/jsfa.4059Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Musati M, Menci R, Luciano G, Frutos P, Priolo A, Natalello A. Temperate nuts by-products as animal feed: A review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2023;305:115787.10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2023.115787Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang M, Cai S, Wang O, Zhao L, Zhao L. A comprehensive review on walnut protein: Extraction, modification, functional properties and its potential applications. J Agric Food Res. 2024;16:101141.10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101141Search in Google Scholar

[8] Mao X, Hua Y. Composition, structure and functional properties of protein concentrates and isolates produced from walnut (Juglans regia L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1561–81. 10.3390/ijms13021561.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Li X, Guo M, Chi J, Ma J. Bioactive peptides from walnut residue protein. Molecules. 2020;25:1285.10.3390/molecules25061285Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Sze-Tao KWC, Sathe SK. Walnuts (Juglans regia L): proximate composition, protein solubility, protein amino acid composition and protein in vitro digestibility. J Sci Food Agric. 2000;80:1393–401.10.1002/1097-0010(200007)80:9<1393::AID-JSFA653>3.0.CO;2-FSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Kong X, Zhang L, Lu X, Zhang C, Hua Y, Chen Y. Effect of high-speed shearing treatment on dehulled walnut proteins. LWT. 2019;116:108500.10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108500Search in Google Scholar

[12] Yan C, Zhou Z. Solubility and emulsifying properties of phosphorylated walnut protein isolate extracted by sodium trimetaphosphate. LWT. 2021;143:111117.10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111117Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhu Z, Zhu W, Yi J, Liu N, Cao Y, Lu J, et al. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res Int. 2018;106:853–61.10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.060Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ismail BP. Ash content determination. In: Nielsen SS, editor. Food analysis laboratory manual. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 117–9.10.1007/978-3-319-44127-6_11Search in Google Scholar

[15] Thiex N. Evaluation of analytical methods for the determination of moisture, crude protein, crude fat, and crude fiber in distillers dried grains with solubles. J AOAC Int. 2009;92:61–73.10.1093/jaoac/92.1.61Search in Google Scholar

[16] Jin W, Pan Y, Wu Y, Chen C, Xu W, Peng D, et al. Structural and interfacial characterization of oil bodies extracted from Camellia oleifera under the neutral and alkaline condition. LWT. 2021;141:110911.10.1016/j.lwt.2021.110911Search in Google Scholar

[17] Yang X, Zhou J, Fu Q, Jin W, Shen W, Tian Y, et al. Mild acid extraction of Camellia protein with low saponin: Composition identification and interfacial stabilization. Food Hydrocoll. 2025;160:110720.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110720Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jiang F, Pan Y, Peng D, Huang W, Shen W, Jin W, et al. Tunable self-assemblies of whey protein isolate fibrils for pickering emulsions structure regulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;124:107264.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107264Search in Google Scholar

[19] Chen J, Jia B, Wang S, Li Z, Ji Z, Li X, et al. Inhibition of the interactions of myofibrillar proteins with gallic acid by β-cyclodextrin-metal-organic frameworks improves gel quality under oxidative stress. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;154:110065.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110065Search in Google Scholar

[20] Yan C, Zhou Z. Walnut pellicle phenolics greatly influence the extraction and structural properties of walnut protein isolates. Food Res Int. 2021;141:110163.10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110163Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Niu Y, Li Y, Qiao Y, Li F, Peng D, Shen W, et al. In-situ grafting of dextran on oil body associated proteins at the oil–water interface through maillard glycosylation: Effect of dextran molecular weight. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;146:109154.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109154Search in Google Scholar

[22] Tizzotti MJ, Sweedman MC, Schäfer C, Gilbert RG. The influence of macromolecular architecture on the critical aggregation concentration of large amphiphilic starch derivatives. Food Hydrocoll. 2013;31:365–74.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.11.023Search in Google Scholar

[23] Yang J, Duan Y, Geng F, Cheng C, Wang L, Ye J, et al. Ultrasonic-assisted pH shift-induced interfacial remodeling for enhancing the emulsifying and foaming properties of perilla protein isolate. Ultrason Sonochem. 2022;89:106108.10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106108Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Peng D, Shang W, Yang J, Li K, Shen W, Wan C, et al. Interfacial arrangement of tunable gliadin nanoparticles via electrostatic assembly with pectin: Enhancement of foaming property. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;143:108852.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108852Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wen J, Zhao J, Jiang L, Sui X. Oil-water interfacial behavior of zein-soy protein composite nanoparticles in high internal phase Pickering emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;149:109659.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109659Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yang J, Duan Y, Zhang H, Huang F, Wan C, Cheng C, et al. Ultrasound coupled with weak alkali cycling-induced exchange of free sulfhydryl-disulfide bond for remodeling interfacial flexibility of flaxseed protein isolates. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;140:108597.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108597Search in Google Scholar

[27] Mao X, Hua Y, Chen G. Amino acid composition, molecular weight distribution and gel electrophoresis of walnut (Juglans regia L.) proteins and protein fractionations. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:2003–14. 10.3390/ijms15022003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Shutov AD, Kakhovskaya IA, Braun H, Bäumlein H, Müntz K. Legumin-like and vicilin-like seed storage proteins: Evidence for a common single-domain ancestral gene. J Mol Evol. 1995;41:1057–69.10.1007/BF00173187Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–402.10.1093/nar/25.17.3389Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Cechin AL, Sinigaglia M, Lemke N, Echeverrigaray S, Cabrera OG, Pereira GAG, et al. Cupin: A candidate molecular structure for the Nep1-like protein family. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:50.10.1186/1471-2229-8-50Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Downs ML, Semic-Jusufagic A, Simpson A, Bartra J, Fernandez-Rivas M, Rigby NM, et al. Characterization of low molecular weight allergens from English walnut (Juglans regia). J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:11767–75.10.1021/jf504672mSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yan M, Li B, Zhao X. Determination of critical aggregation concentration and aggregation number of acid-soluble collagen from walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) skin using the fluorescence probe pyrene. Food Chem. 2010;122:1333–7.10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.03.102Search in Google Scholar

[33] Aydin F, Chu X, Uppaladadium G, Devore D, Goyal R, Murthy NS, et al. Self-assembly and critical aggregation concentration measurements of ABA triblock copolymers with varying B block types: model development, prediction, and validation. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120:3666–76.10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b12594Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Basak R, Bandyopadhyay R. Encapsulation of hydrophobic drugs in Pluronic F127 micelles: effects of drug hydrophobicity, solution temperature, and pH. Langmuir. 2013;29:4350–6.10.1021/la304836eSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Tao Y, Cai J, Wang P, Chen J, Zhou L, Zhang W, et al. Application of rheology and interfacial rheology to investigate the emulsion stability of ultrasound-assisted cross-linked myofibrillar protein: Effects of oil phase types. Food Hydrocoll. 2024;154:110086.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110086Search in Google Scholar

[36] Xia W, Botma TE, Sagis LMC, Yang J. Selective proteolysis of β-conglycinin as a tool to increase air-water interface and foam stabilising properties of soy proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;130:107726.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107726Search in Google Scholar

[37] Yang J, Yang Q, Waterink B, Venema P, de Vries R, Sagis LMC. Physical, interfacial and foaming properties of different mung bean protein fractions. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;143:108885.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108885Search in Google Scholar

[38] Wan Z, Yang X, Sagis LMC. Nonlinear surface dilatational rheology and foaming behavior of protein and protein fibrillar aggregates in the presence of natural surfactant. Langmuir. 2016;32:3679–90.10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b00446Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Peng D, Yang J, de Groot A, Jin W, Deng Q, Li B, et al. Soft gliadin nanoparticles at air/water interfaces: The transition from a particle-laden layer to a thick protein film. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;669:236–47.10.1016/j.jcis.2024.04.196Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Yang J, Shen P, de Groot A, Mocking-Bode HCM, Nikiforidis CV, Sagis LMC. Oil-water interface and emulsion stabilising properties of rapeseed proteins napin and cruciferin studied by nonlinear surface rheology. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;662:192–207.10.1016/j.jcis.2024.02.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II

- Revealing the interfacial dynamics of Escherichia coli growth and biofilm formation with integrated micro- and macro-scale approaches

- Construction of a model for predicting sensory attributes of cosmetic creams using instrumental parameters based on machine learning

- Effect of flaw inclination angle and crack arrest holes on mechanical behavior and failure mechanism of pre-cracked granite under uniaxial compression

- Special Issue on The rheology of emerging plant-based food systems

- Rheological properties of pea protein melts used for producing meat analogues

- Understanding the large deformation response of paste-like 3D food printing inks

- Seeing the unseen: Laser speckles as a tool for coagulation tracking

- Composition, structure, and interfacial rheological properties of walnut glutelin

- Microstructure and rheology of heated foams stabilized by faba bean isolate and their comparison to egg white foams

- Rheological analysis of swelling food soils for optimized cleaning in plant-based food production

- Multiscale monitoring of oleogels during thermal transition

- Influence of pea protein on alginate gelation behaviour: Implications for plant-based inks in 3D printing

- Observations from capillary and closed cavity rheometry on the apparent flow behavior of a soy protein isolate dough used in meat analogues

- Special Issue on Hydromechanical coupling and rheological mechanism of geomaterials

- Rheological behavior of geopolymer dope solution activated by alkaline activator at different temperature

- Special Issue on Rheology of Petroleum, Bitumen, and Building Materials

- Rheological investigation and optimization of crumb rubber-modified bitumen production conditions in the plant and laboratory