Abstract

This study aims to enhance the sensory evaluation of skin creams by using machine learning to predict sensory attributes based on instrumental parameters, addressing the limitations of conventional methods. Extensive instrumental parameters, including rheological, tribological, and textural properties of ten different skin creams, were collected, and 22 sensory attribute scores were obtained from trained expert evaluations. Pearson’s correlation analyses and multiple supervised learning algorithms were applied to establish relationships between each sensory attribute and the instrumental parameters, respectively. The results showed that K-Nearest Neighbors, AdaBoost, and LightGBM were the algorithms with the best performance for most sensory attributes, and the overall model achieved over 95% prediction accuracy for 80% of the sensory dimensions, demonstrating strong reproducibility and accuracy in the verification test, with predicted sensory scores closely aligning with actual values. However, issues such as model overfitting, discrepancies between training and testing data distributions, and increased noise in the testing data, which result in the residuals from the testing set exceeding those from the training set, need to be further addressed in future research. In summary, this data-driven approach offers a more efficient, accurate, and standardized method for sensory evaluations, with the potential to support the development and optimization of skincare products.

1 Introduction

Skincare products are generally designed to maintain health and improve the appearance of the skin through retaining skin moisture, repairing the skin barrier, reducing melanin, and alleviating signs of skin aging [1,2]. Equally important to these benefits are the sensory attributes of the product, such as texture, spreadability, and absorption, which directly impact consumers’ satisfaction and willingness to use the product [2,3]. Research has shown that skincare formulas and key ingredients can trigger emotional changes, as evaluated through prosody, ethological, and electroencephalography analyses [4,5]. Additionally, some studies have revealed a relationship between the frequency use of products that reduce skin laxity and self-esteem, highlighting the involvement of psychological factors in the cosmetic field [6]. However, the evaluation of sensory attributes often relies on panel sensory tests, which are not only time-consuming and expensive, but may also fluctuate due to individual differences and environmental factors [7]. Therefore, developing a faster, precise, and quantitative method to predict the sensory attributes of cosmetics has broad prospects. Quantitative data obtained through instrument testing can be used to objectively analyze the physical characteristics of cosmetics. Associating these results with the sensory experience of actual product application can not only improve the accuracy of product research, but also predict the user’s experience during the early stages of product development, thereby enhancing market competitiveness [8]. Currently, the advanced instrumental analysis methods mostly used in the cosmetics industry include texture analyzers, rheometers, and tribometers. Texture analyzers measure the physical properties of cosmetics under conditions of pressure, tension, or shear, which is closely related to sensory attributes like thickness and density [9,10]. Rheometers measure rheological parameters such as viscosity, elastic modulus, and shear stress by simulating the flow and deformation behavior of cosmetics under different patterns and conditions [11,12]. This helps predict the fluidity and smoothness of the product during application. Friction measurements evaluate the friction coefficient of cosmetics on the skin surface, providing quantitative information about the smoothness, lubricity, and absorption performance [13].

Ahuja et al. investigated the correlation between rheological properties and sensory attributes of 33 commercial moisturizers, finding that the instantaneous maximum viscosity was the best predictor of most sensory attributes. Additionally, the G′/G″ ratio was important for spreading properties such as thickness and spreadability, indicating that repeated finger rubbing actions can be simulated in a rheometer through oscillatory testing [12]. Jiang et al. attempted to establish the relationship between the rheological properties and melting sensation of oil-in-water (O/W) cream cosmetics, and they found that lower values for parameters such as viscosity in the first Newtonian zone, the area of the hysteresis loop, and the viscoelastic modulus correlated with higher melting sensation index and stronger melting sensation overall [14]. Lin and Yu explored the correlation between the sensory properties and texture instrument test parameters of five foundation creams with different thickening agent contents. Their results showed that the softness of skin sensation during application was strongly correlated with texture hardness and cohesiveness, with correlation coefficients of 0.909 and 0.745, respectively. They also found that cream spreadability was significantly negatively correlated with texture hardness, with a correlation coefficient of −0.512 [15]. Zhou et al. conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis on the compression mode test parameters from a texture analyzer and skin feel indicators of seven different creams. They found that texture hardness, peak pressure, and viscosity were significantly negatively correlated with a product pick up property, with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.783 to −0.865 [16]. Timm et al. prepared cosmetic powder suspensions of different particle sizes and concentrations and explored the correlation between the friction coefficient and skin feel under in vitro conditions. They discovered that small powder particles with irregular shapes provided better lubrication between the fingertips and the skin surface, and as particle concentration increased, skin sensations such as powdery, silky, and soft were enhanced [17].

Considering that the prediction accuracy of a single instrument for sensory attributes may not always meet expectations, some studies have combined the parameters of multiple instruments to improve predictions. For example, Yarovaya et al. successfully established correlations between sensory attributes and rheological and texture parameters of sunscreen formulations using principal component analysis and partial least square regression [18]. Although these techniques are effective in addressing collinearity by identifying latent variables, it is important to note that they do not establish causal correlations between the parameters and are limited to describing nonlinear correlations between the variables. Cyriac et al. combined rheological and tribological evaluation methods, demonstrating that flow curves, oscillatory strain sweeps (small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) and large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS)), and coefficient of friction (CoF) measurements could be used for sensory screening of a large number of prototype formulations [19]. Gilbert et al. conducted rheological property analysis on nine O/W emulsions with different polymer contents, including flow, creep, and oscillation tests, and used a texture analyzer to determine the penetration, compression, stretching, and spreadability of the emulsions. The results revealed that the stress value (σ) obtained from oscillatory strain scanning, the area value from the texture analyzer’s friction test, and the fracture length from the compression/stretching test were well correlated with the shape retention ability, spreadability, and viscosity in the sensory evaluation of the products, with R p values of 0.974, 0.986, and 0.974, respectively [20]. Surprisingly, most of these research studies only emphasized the correlation between instrumental parameters and sensory attributes from a qualitative perspective, which was not clearly expressed through predictive models. Furthermore, validation steps were often not performed, which limited the reliability of using instrumental parameters to predict the skin sensory properties of products.

Machine learning (ML) enables computers to learn from data without being explicitly programmed, significantly advancing the development of artificial intelligence (AI) in recent years [21]. By using algorithms and statistical models, ML systems identify patterns based on historical data and make predictions or decisions for previously unseen data. The central challenge in ML is to develop adaptive models that address the parsimony problem-finding the right balance between model complexity and generalizability. This involves creating models that are flexible enough to capture underlying patterns in the data while avoiding over-fitting, which would reduce their effectiveness on new, unseen data. ML can address a variety of core problems, such as classification, regression, clustering, and reinforcement-driven decision-making, which are applied across fields like healthcare, finance, and customer service. Depending on the type of algorithms used, ML can be divided into unsupervised learning, supervised learning, and reinforcement learning [22]. In unsupervised learning, the system works with unlabeled data, identifying hidden patterns or structures without predefined labels, and it is commonly used for clustering, anomaly detection, and association rule learning. In contrast, supervised learning involves training a model on labeled data, where the system learns to map inputs to correct outputs, typically for classification and regression tasks [22]. Reinforcement learning trains a model through trial and error, with the system interacting with its environment and learning from rewards or penalties to optimize cumulative rewards, making it particularly effective in decision-making tasks within dynamic environments, such as robotics, gaming, and autonomous systems [22]. In the cosmetics industry, ML has demonstrated significant potential beyond traditional applications. It can be used to optimize formulations, assist in selecting ingredients such as surfactants, polymers, preservatives, and fragrances, predict product performance, and analyze structure–property relationships [23]. By facilitating the collection, classification, and interpretation of large datasets during product development, ML enhances efficiency, precision, and innovation. Shim et al. established a model based on ML that can quickly, cost-effectively, and efficiently predict the sun protection factors (SPF and PFA) of sunscreens. By incorporating additional factors such as active ingredient information, pigment presence, pigment-grade titanium dioxide concentrations, formulation types, and product types, the model significantly improved its accuracy and showed a strong correlation with actual clinical test results [24]. Goussard et al. used the COSMO-RS σ-moment-based neural network and graph ML methods to establish a model for quickly estimating the viscosity of pure liquids below 25°C, particularly for cosmetic oils. They found that the graph machine method provided the most accurate results in predicting the viscosity of a set of independent cosmetic oils. Additionally, the results of the σ-moment-based neural network and graph machine methods can be easily reproduced through a demonstration tool supported by Docker technology, allowing users to predict the viscosity of any medium-sized liquid (M < 600 Da) containing C, H, O, or Si atoms at 25°C [25]. Ragno et al. improved the quantitative structure–activity relationship of complex mixtures using data enhancement technology based on ML methods. They constructed a model with high statistical coefficients and identified some clues related to the specific antibacterial effects of essential oil components through model inspection [26]. Although much of the research remains at the proof-of-concept stage, the future application prospects of ML and AI are vast. These technologies could simulate the complex interactions between cosmetic ingredients, aid in designing new components, and pave the way for groundbreaking advances in formulation science [27].

In this study, we aim to establish a prediction model for instrumental parameters and sensory attributes by combining textural, tribological, and rheological data. We collected extensive basic data on the physical properties of ten skin creams with different formulations using a texture analyzer, a friction and wear tester, and a rheometer. Simultaneously, a team of trained experts conducted sensory evaluations of the creams. For these data, we first performed a Pearson’s correlation analysis to identify a one-to-one linear relationship between the instrument parameters and sensory attributes at a qualitative level. Next, we applied ML methods based on the characteristics and application processes of different algorithms. By comparing the fitting performance of various algorithms for different sensory attributes, we selected the best-fitting algorithm for each sensory attribute and integrated it into a sensory prediction model. Finally, we tested the model with four additional samples, which were not used in the model-building process, to evaluate the model’s generalization ability and accuracy.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Fourteen skin creams used in this study were commercially available and provided by Proya Cosmetics Co., Ltd. Among them, ten samples (labeled SC1–SC10) were randomly selected as the training set for physical property analysis, Pearson’s correlation analysis, and ML to establish the sensory prediction model, while four samples (labeled YZ1–YZ4) were used as the testing set for model evaluation.

2.2 Sensory evaluations

A panel of 12 trained experts was recruited to evaluate the sensory performance of the samples. The sensory properties were classified into four categories: Appearance, Finger contact for the first time, In-use sensory attributes, and After-use sensory attributes. For each sample, an amount of 0.05 mL was placed on the inner arm, and the panelist smeared it slowly in circular motion with fingers. Each attribute was scored on a scale of 0–15, and all samples were evaluated twice to ensure accuracy. The detailed attributes protocol is listed in Table S1 of the supplementary material. The sensory evaluation environment adhered to the American Society for Testing and Materials standards and was conducted in an environment maintained at a constant temperature of 23 ± 2℃ and a relative humidity of 50 ± 10% RH.

2.3 Texture analyzer measurements

The texture properties of products were measured using a texture analyzer (iTexture, ThinkSenso&Senso, China) equipped with a stainless steel plate probe of 15 mm diameter. Briefly, 30–40 g sample was loaded into a small beaker to reach equilibrium before measurements. The probe moved vertically downward at a speed of 0.25 mm/s until reaching a trigger force of 0.02 N, at which point it penetrated the sample at a speed of 0.5 mm/s until a depth of 20 mm was achieved. After holding for 1 s at this position, the probe withdrew vertically to its initial position at a speed of 0.5 mm/s. This process was performed twice, with texture parameters, except spreadability, provided directly by the instrument. Texture spreadability was calculated as the integral of the area under the first downward movement. All samples were tested in triplicate.

2.4 Friction measurements

Friction measurements were conducted using a friction and wear tester (MPT-1, Limei Electromechanical Technology, China) equipped with a spherical probe of 26 mm diameter. A sufficient amount of samples was placed on the 5-mm-thick bio skin (Beaulax, Tokyo) substrate made of polyurethane elastomer. The probe pressed the sample while sliding back and forth at a velocity of 5 mm/s for 40 min to observe the friction change during the spreading process. The test involved a reciprocating stroke of 100 mm with a normal load of 2 N.

2.5 Rheological measurements

Rheological measurements were carried out using a rheometer (Discovery HR-20, TA Instruments, USA) equipped with a 40 mm parallel plate geometry. An appropriate amount of samples was loaded onto the lower plate, and the upper plate was lowered to cover the sample with a testing gap of 1 mm (except for compression measurements). The experiment temperature was set at 25℃.

2.5.1 Steady-state flow measurements

The steady-state flow curve was obtained by setting the shear rate between 10−5–102 s−1 with 10 pts dec−1. Based on the yield stress of the sample obtained from the flow curve test, the rheological destruction and recovery tests were performed. The tests were divided into three stages, with 15 min of testing time for each stage. In the first stage, the shear rate was set within the yield stress of the sample. In the second stage, the shear rate was set to ten times that of the previous stage, resulting in a corresponding stress that exceeded the yield stress. The shear rate in the third stage was the same as that in the first stage, allowing the sample to recover from the rheological destruction.

2.5.2 Oscillatory measurements

Oscillatory amplitude sweep measurements were performed within a strain amplitude range of 0.01–1000% at a frequency of 1 Hz and 10 pts dec−1. This process included traditional SAOS testing and LAOS testing. Lissajous plots were generated according to sinusoidal deformation at various strains and a single frequency. Additionally, oscillatory frequency sweep measurements were performed from 0.05 to 100 rad/s within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR).

2.5.3 Creep and creep recovery

Creep and creep recovery measurements were carried out in two steps to analyze the viscoelastic behaviors of the sample. A stress within LVR (depending on the sample) was applied for creep testing and maintained for 5 min. Creep recovery testing followed for 10 min without any applied stress.

2.5.4 Compression measurements

Compression measurements were conducted with an initial gap of 2 mm. The parallel plate moved vertically downward to a gap of 0.5 mm at a speed of 0.1 mm/s over 15 s. Subsequently, the parallel plate moved vertically upward to a gap of 3 mm at the same speed over 25 s.

2.6 Data processing and Pearson’s correlation analysis

The model fitting was performed using Origin 2024 (OriginLab, USA). Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests were used to determine the significant differences among the ten skin creams (SC1–SC10) from sensory and instrumental texture attributes. The results were presented as letters, where the same letter in a column indicated that the corresponding skin creams were not significantly different for the attribute considered (p < 0.05). Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to determine the linear correlation between sensory attributes and instrumental parameters. All the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 27.0 (IBM, USA).

2.7 ML modeling

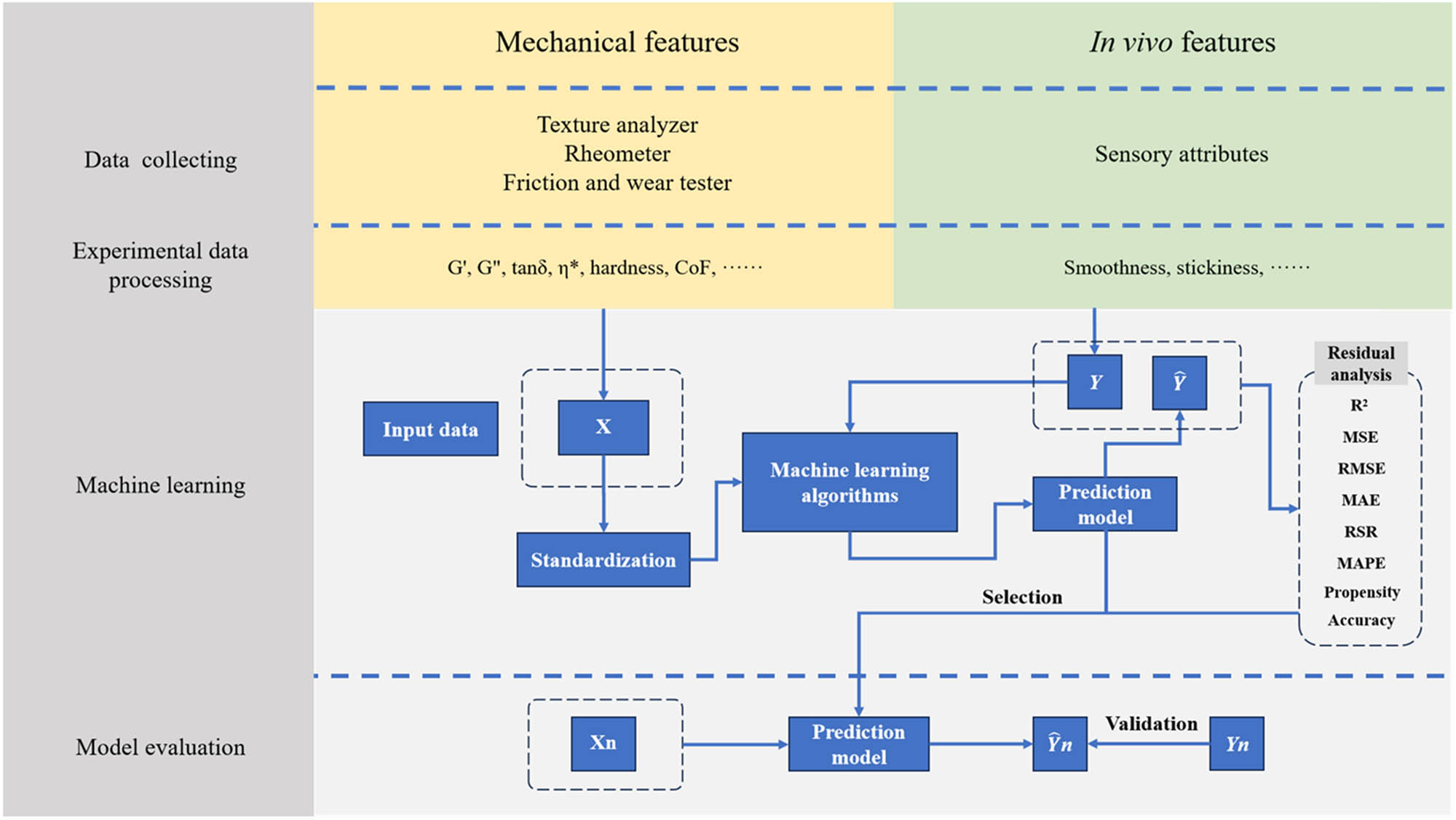

Considering the complexity of the sensory attribute evaluation data, we employed supervised learning regression models with multiple regression and multi-feature input to perform separate fitting and training for each dimension of the sensory attribute. This approach more accurately establishes the mappings between the data input and each sensory attribute dimension, thereby improving the model’s prediction accuracy. The process schematic diagram of a model for predicting sensory attributes using instrument parameters based on ML is shown in Figure 1. In brief, we first used the obtained instrument parameters as the independent variable X and standardized the data to eliminate the impact of dimension, thereby accelerating the model convergence and improving the stability of the model. Simultaneously, we used the sensory evaluation data as the dependent variable Y, which contains 22 dimensions in total. All data of X and Y include error ranges due to measurement errors, calculation errors, and individual differences among subjects. Therefore, we use the Monte Carlo simulation method to simulate the dataset, simulating 1,000 sets of data for each sensory dimension. Next, we divided the prepared data into a training set (80%) and a validation set (20%) as the model’s input data. The training set was used to train the model to learn the relationship between the input features and the target data, while the validation set was used to monitor the model performance and prevent over-fitting. Then, we selected algorithms with good predictive performance for discrete data, including Linear Regression, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, Ridge, ElasticNet, AdaBoost (Ada), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BR), Light Gradient Boosting Machin (LightGBM), and Gaussian Process Regression. Each dimension of Y was trained separately, and residual analysis was performed to set rules for selecting the optimal algorithm for each dimension of Y. The screening rules were as follows: (1) the coefficient of determination (R-Square, R 2) must be greater than 0.7; and (2) algorithms were ranked according to the priority of mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE), from smallest to largest, and the algorithm with the smallest residual was selected. Finally, the best algorithm for each dimension of Y was integrated into a sensory property prediction model. The same physical and sensory property data of four additional samples were collected and processed. These data were input into the model to obtain the sensory prediction values of the products, which were then compared with the actual sensory test values to evaluate the accuracy and usability of the model.

Process schematic diagram of a model for predicting sensory attributes using instrument parameters based on ML.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Sensory analysis

The skin feel of products provides a unique sensory experience for consumers, both physically and mentally. It is crucial for cosmetic formulation engineers to consider skin feel when designing their formulations. Sensory evaluations carried out by professional panelists can provide relatively objective sensation results regardless of some personal preference, which is a useful tool to study sensation-related research and to develop cosmetic products. The average sensory scores of SC1–SC10 were presented in Table S2, where Tukey’s HSD tests were performed to confirm differences among the products. The results indicated that most sensory attributes were significantly different among the samples, as evidenced by the varying scores and HSD tests. However, some sensory attributes showed similar scores, such as Skin stickiness (2 min) and Skin watery (2 min). This similarity may be attributed to the evaporation of volatile compounds, thereby leading to a comparable after-feel among the skin creams. In terms of appearance, SC5 and SC6 exhibited the highest values of Fineness of texture (10.8 ± 1.0 and 11.2 ± 0.9, respectively) and Reflection of product (10.5 ± 0.9 and 10.8 ± 0.9, respectively). The Pick up attribute describes the initial sensation when the finger first contacts the skin cream. SC9 had the lowest Bounce (5.4 ± 1.3) and was softer than other skin creams, making it relatively difficult to pick up (6.9 ± 1.2), with the lower Peaking (2.5 ± 0.7). Notably, the Skin watery decreased to some extent in all samples after 2 min of application, likely due to water evaporation from the surface of skin.

3.2 Instrumental texture analysis

The texture analyzer is widely used in the food industry to test the physical properties related to human sensory evaluation. As the instrument’s functions diversify and interdisciplinary integration advances, the texture analyzer has also become a valuable tool in the pharmaceutical, material, and cosmetic industries. As shown in Table 1, texture parameters such as hardness, fracturability, adhesiveness, springiness, cohesiveness, and resilience were obtained through compression tests on the texture analyzer. Figure 2 illustrates the texture plot of SC1, depicting the force and time relationship during the compression of the sample by the plate probe. Texture springiness reflected the initial skin feel of the cream, of which SC7 exhibited the highest value, positively influencing consumer preference in a positive way, while SC5 had the lowest springiness. Texture hardness quantified the deformation of the cream before application. SC10, SC4, and SC1 had relatively higher hardness, suggesting that consumers require a larger force to apply these creams. HSD multiple comparison tests categorized the ten skin creams into several groups based on their texture properties. For example, all samples could be divided into seven groups according to texture adhesiveness, indicating differences in user experience, particularly regarding spreadability and wateriness. Nevertheless, some characteristics lacked clear distinctions, as observed in terms of texture fracturability, cohesiveness, or resilience, suggesting that the skin creams had similar initiate contact attributes to some extent.

Average values (± standard deviation) of texture properties with Tukey’s post hoc test

| Skin creams | Hardness (g) | Fracturability (g) | Adhesiveness (g s) | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Resilience | Spreadability (g s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 16.2446 ± 0.29b | 2.5568 ± 0.29ab | 274.5315 ± 6.16c | 0.9463 ± 0.02abc | 0.9202 ± 0.02ab | 0.0677 ± 0.08b | 403.35 ± 11.80b |

| SC2 | 9.7280 ± 0.34d | 2.3816 ± 0.30ab | 137.6232 ± 14.37e | 0.9556 ± 0.01abc | 0.8606 ± 0.02ab | 0.0603 ± 0.06b | 246.96 ± 8.93c |

| SC3 | 11.5831 ± 0.31c | 2.2934 ± 0.06ab | 197.4645 ± 9.42d | 0.9682 ± 0.01ab | 0.8901 ± 0.02ab | 0.0517 ± 0.02b | 269.20 ± 4.21c |

| SC4 | 16.2886 ± 0.51b | 2.3081 ± 0.21ab | 321.5973 ± 15.71b | 0.9679 ± 0.01ab | 0.8167 ± 0.02b | 0.0460 ± 0.01b | 181.61 ± 16.30e |

| SC5 | 9.1201 ± 0.04d | 2.0942 ± 0.16ab | 132.0061 ± 7.82e | 0.9146 ± 0.02c | 0.8697 ± 0.07ab | 0.0720 ± 0.01b | 206.69 ± 4.21d |

| SC6 | 6.3787 ± 0.15e | 1.8789 ± 0.08b | 51.2315 ± 2.06f | 0.9441 ± 0.01bc | 0.8953 ± 0.03ab | 0.1034 ± 0.01ab | 157.52 ± 5.10f |

| SC7 | 5.1185 ± 0.16f | 1.8287 ± 0.27b | 12.8417 ± 2.80g | 0.9908 ± 0.02a | 0.9060 ± 0.03ab | 0.1356 ± 0.05a | 129.27 ± 2.98g |

| SC8 | 5.9094 ± 0.21ef | 2.0696 ± 0.16ab | 45.9744 ± 11.20f | 0.9759 ± 0.03ab | 0.8616 ± 0.03ab | 0.0975 ± 0.04ab | 145.71 ± 3.17fg |

| SC9 | 6.2866 ± 0.33e | 1.9071 ± 0.26b | 43.5501 ± 6.55f | 0.9637 ± 0.01ab | 0.9243 ± 0.06a | 0.0829 ± 0.02ab | 148.16 ± 4.07fg |

| SC10 | 18.1896 ± 0.15a | 3.1678 ± 1.08a | 366.2281 ± 14.53a | 0.9567 ± 0.01abc | 0.9163 ± 0.01ab | 0.0455 ± 0.01b | 449.38 ± 6.34a |

The same letter in a column indicated that the corresponding skin creams were not significantly different for the attribute considered (p < 0.05).

Force–time plot of SC1 obtained from the texture analyzer.

3.3 Friction analysis

Friction measurements provide a macroscopic simulation that effectively describes the changes in CoF during the skin cream spreading process, which corresponds to sensory changes. Skin creams can be viewed as lubricants when applied onto human skin. The lubrication process can be divided into three regimes as film thickness decreases: hydrodynamic, mixed, and boundary [2]. The hydrodynamic regime occurs when the skin cream is initially spread on the skin or substrate, and the lubrication layer is thick enough. In this stage, the perception of the skin cream primarily depends on the formulation’s characteristics, particularly the ingredients in the oil phase (such as plant oils, silicones, and fatty alcohols) and the emulsifiers used. These components influence the texture, smoothness, spreadability, and initial skin feel, while the characteristics of the skin or substrate have less impact at this stage. As the spreading action continues and the film between the finger and the skin or substrate becomes thinner, the perception of the skin cream is mainly influenced by the film. In the mixed regime, the CoF usually increases, which may be attributed to the evaporation of compounds and the hydration of moisturizers. The boundary regime occurs when the residue film continues to thin during spreading. At this point, the CoF is stabilized, and the perception of the skin cream is dominant by the surface of the skin or substrate [13,28]. Figure 3 illustrates the unidirectional CoF changes during the probe sliding on the bio-skin with SC1. The sliding process could be divided into three stages. The CoF was relatively low initially but increased after 5 min, indicating a brief hydrodynamic regime, followed by the mixed regime. The CoF continued to increase and stabilized within 15 min, transitioning to the boundary regime. Overall, the CoF during the sliding process remained below that of the bare substrate (0.0673, dotted line), indicating that SC1 provided a lubricating effect. Additionally, the fluctuations at the edges of the stroke were due to the machine's instability and could be disregarded. Figure 4 demonstrates the CoF of SC1–SC10 at different sliding times. The CoF of SC2, SC4, SC5, SC7, SC8, and SC9 showed slight changes (always below the bare bio-skin) over 40 min of sliding, indicating good lubrication effects, which might be relevant to certain sensory attributes, such as thickness, watery, greasiness, and smoothness. SC10 exhibited a higher CoF than that of the bare bio-skin after 10 min, indicating increased stickiness and residue. On the contrary, SC3 and SC6 displayed a similar trend of the CoF change, which exhibited a decrease at the beginning and an increase at the end of the friction test. This suggested that SC3 and SC6 experienced a prolonged hydrodynamic regime, and the mixed regime occurred much later than SC1 and SC10. The possible reason was that the involatile squalene in SC3 and the stronger interactions caused by a higher content of ammonium acryloyldimethyltaurate/VP copolymer in SC6 hindered the volatilization process. In contrast, the volatile decamethylcyclopentasiloxan in SC1 and isocetane in SC10 led to relatively quick volatilization. Overall, friction situations vary based on usage conditions such as spreading strength, speed, and direction, and human skin absorbs substances in the formulations, thereby leading to changes in the friction coefficient. Although sliding on the bio-skin was a simulation scenario, it provides insights into tribological changes and potential relationships between the CoF and sensory attributes.

Unidirectional CoF changes of SC1 after different time intervals.

(a) CoF of SC1–SC10 at different sliding times and (b) the enlarged details.

3.4 Rheological analysis

3.4.1 Flow curve measurements

Continuous shear rate testing captured the shear rates encountered during the application of skin creams, providing a practical reference for simulating their sensory characteristics in daily use. For example, a shear rate of 100 s−1 represents the terminal rate of pouring semisolid products and the starting rate of spreading on the skin [29], while 200 s−1 is the typical rate of spreading [18]. To analyze the transition from a solid-like bulk state to a fluid-like flow state, viscosity versus shear rate and shear stress versus shear rate were plotted separately (Figure 5a and b). A high viscosity plateau was observed under a low shear rate, and viscosity decreased as the shear rate increased, demonstrating shear thinning behavior (Figure 5a). High shear rates disrupted the polymer structure and intermolecular force, resulting in viscosity decline. This shear-thinning behavior was consistent across all tested skin creams. Fitting the experimental data to rheology flow models provided additional parameters to describe the fluid flow behavior. The viscosity curves were fitted to the Cross model (Figure 5c), and the stress curves were fitted to the Herschel–Bulkley model (Figure 5d). From the Cross model, the zero shear rate viscosity η 0, power law exponent m, and the critical shear rate at which a fluid transitions from Newton’s law to power law behavior γ c were obtained. Yield stress σ y (the longitudinal intercept of fitting curves at zero shear rates), consistency index k, and shear thinning coefficient n were obtained from the Herschel–Bulkley model. As can be seen from Table 2, η 0 and σ y of the skin creams were between 965–1,1391 Pa s and 8.43–74.31 Pa, respectively, indicating good stability against spontaneous flow caused by gravity. The difference in η 0 and σ y of the creams was attributed to intermolecular interactions of the formulations, which might influence the sensory attributes, like the initial spreadability. SC4 and SC10 exhibited relatively high η 0 and σ y , indicating a heavy texture and poor spreadability. Moreover, all samples showed n < 1, confirming shear thinning behaviors.

(a) Viscosity versus shear rate, (b) shear stress versus shear rate, (c) cross model fitting curve, and (d) Herschel–Bulkley model fitting curve of SC6 were plotted from continuous shear rate testing.

Fitting model data of experimental flow curves

| Skin creams | Cross model | Herschel–Bulkley model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η 0 (Pa s) | m | γ c (s−1) | σ y (Pa) | k (Pa sn) | n | |

| SC1 | 6378.69 ± 1245.74 | 0.90 ± 0.23 | 0.019 ± 0.010 | 48.45 ± 3.43 | 110.27 ± 3.49 | 0.64 ± 0.05 |

| SC2 | 3577.95 ± 220.53 | 0.90 ± 0.14 | 0.030 ± 0.006 | 8.43 ± 6.92 | 62.82 ± 7.14 | 0.37 ± 0.05 |

| SC3 | 7700.45 ± 1003.54 | 0.90 ± 0.21 | 0.012 ± 0.005 | 24.61 ± 3.82 | 69.52 ± 4.07 | 0.59 ± 0.06 |

| SC4 | 11391.40 ± 1966.78 | 0.90 ± 0.24 | 0.022 ± 0.010 | 74.31 ± 12.36 | 76.94 ± 13.02 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| SC5 | 2364.82 ± 226.59 | 0.90 ± 0.15 | 0.036 ± 0.009 | 43.80 ± 1.23 | 19.61 ± 1.26 | 0.38 ± 0.01 |

| SC6 | 1265.40 ± 97.96 | 0.90 ± 0.14 | 0.035 ± 0.008 | 26.51 ± 0.34 | 12.53 ± 0.33 | 0.40 ± 0.01 |

| SC7 | 965.33 ± 91.44 | 0.90 ± 0.16 | 0.022 ± 0.006 | 13.07 ± 0.24 | 6.53 ± 0.23 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| SC8 | 1455.78 ± 147.85 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.025 ± 0.008 | 20.58 ± 0.24 | 10.36 ± 0.23 | 0.43 ± 0.00 |

| SC9 | 1821.45 ± 270.94 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.028 ± 0.011 | 25.66 ± 0.70 | 9.08 ± 0.69 | 0.46 ± 0.02 |

| SC10 | 8239.87 ± 1407.66 | 0.90 ± 0.22 | 0.019 ± 0.009 | 52.42 ± 4.36 | 203.88 ± 3.61 | 0.50 ± 0.04 |

3.4.2 Rheodestruction and recovery measurements

Figure 6 presents the rheodestruction and recovery measurements of SC7. The viscosity of the formulation remarkably declined under high shear rates (the second stage), indicating interior structure destruction. However, the viscosity recovered to a certain extent during the third stage, where the shear rate was within the LVR. Similar results were obtained for other skin creams. The percentages of destruction and recovery could be calculated using the following equations:

where η 1, η 2, and η 3 represent the viscosity of the three stages, respectively. The calculated destruction and recovery percentages for SC1–SC10 are presented in Table 3. All skin creams exhibited destruction percentages exceeding 90%, indicating that outside the LVR, interior interactions were disrupted, allowing the creams to flow. Notably, SC1, SC3, SC6, SC7, SC8, and SC9 showed destruction percentages of over 99%, indicating excellent spreadability. The recovery percentage reflects the degree of the sample returning to its original structure after removing the high shear rate. A lower recovery percentage meant more irreversible structure destruction at the second stage, which could lead to issues such as self-dripping if consumers removed the action in the middle of smearing. SC6 had a recovery percentage of only 33.53%, while the remaining skin creams had recovery percentages of over 60%. Interestingly, SC8 exhibited a recovery percentage of 108.51%, which was possibly due to the macromolecule rearrangement or the intermolecular structure rebuilt [30,31].

Rheodestruction and recovery curve of SC7.

Percentage of rheodestruction and recovery of SC1–SC10

| Skin creams | % Destruction | % Recovery |

|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 99.17 ± 11.81 | 62.44 ± 6.41 |

| SC2 | 94.83 ± 7.59 | 81.45 ± 6.59 |

| SC3 | 99.87 ± 5.49 | 77.43 ± 3.22 |

| SC4 | 91.78 ± 4.97 | 86.18 ± 12.52 |

| SC5 | 98.58 ± 6.35 | 62.09 ± 3.80 |

| SC6 | 99.60 ± 5.72 | 33.53 ± 1.62 |

| SC7 | 99.72 ± 14.41 | 94.25 ± 8.20 |

| SC8 | 99.58 ± 12.24 | 108.51 ± 10.18 |

| SC9 | 99.86 ± 16.31 | 89.54 ± 13.04 |

| SC10 | 97.59 ± 4.83 | 76.41 ± 3.93 |

3.4.3 Oscillatory amplitude sweep measurements

The mechanical properties of samples under varying deformation can be assessed through oscillatory amplitude sweeps, especially regarding the extreme extent to which the sample can endure. A larger LVR and higher yield force indicate greater extreme deformation capacity and better mechanical stability. At a fixed frequency, applying a strain ranging from 0.01 to 1,000% will initially result in a SAOS response, which provides information on the LVR. As the strain increases beyond this range, an LAOS response occurs, during which the microstructure may undergo irreversible changes. Key formulation parameters, such as storage modulus (G′), loss modulus (G″), loss factor (tan δ = G″/G′), complex viscosity (η * ), and yield stress (σ y , the inflection point of the stress–strain curve), can be obtained from SAOS. As shown in Figure 7a, the sample initially displayed a linear elastic response (G′ > G″). As the strain increased, both G′ and G″ decreased, with G″ gradually dominating. When the stress exceeded the intersection point of G′ and G″ (σ cross), the response of the sample was dominated by viscous shear, resulting in the loss of cohesive structural interaction. σ y was considered the transition stress of the sample from viscoelasticity to viscoplasticity. Below σ y , the sample exhibited elastic deformation, at which point stress and deformation were linearly related. σ VE-V was calculated as σ cross minus σ y , which quantified the required stress that transferred the sample from viscoelasticity to viscous flow.

(a) Oscillatory amplitude sweep curve of SC10 and (b) oscillatory frequency sweep curve of SC5.

Table 4 presents the rheological parameters obtained from oscillatory amplitude sweeps. G′ of SC1, SC3, SC4, and SC10 were relatively high, indicating stronger structural rigidity and integrity. Nevertheless, formulation rigidity is not in direct proportion to mechanical stability. For instance, SC3 showed high G′ but low σ y , suggesting strong rigidity but sensitivity to mechanical deformation during oscillatory. In contrast, SC4 exhibited a relatively high σ y , resulting in better mechanical stability. Furthermore, SC1 and SC10 required more energy to turn into viscous flow according to σ VE-V. Typical oscillatory frequency sweep curves are shown in Figure 7b. In the frequency range of 0.05–100 rad/s, all samples exhibited G′ > G″, further confirming good storage stability while the skin creams were in a static state.

Rheological parameters obtained from oscillatory amplitude sweep

| Skin creams | G′ (Pa) | G″ (Pa) | tan δ | η * (Pa s) | σ y (Pa) | σ cross (Pa) | σ VE-V (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 1348.0 ± 20.6 | 205.0 ± 0.3 | 0.20 | 217.0 ± 3.2 | 15.73 ± 0.07 | 138.6 ± 3.1 | 122.87 |

| SC2 | 834.0 ± 2.3 | 314.0 ± 5.5 | 0.40 | 142.0 ± 0.5 | 13.15 ± 0.07 | 19.8 ± 0.6 | 6.65 |

| SC3 | 2554.0 ± 25 | 768.0 ± 15 | 0.30 | 424.0 ± 4.0 | 6.36 ± 0.03 | 89.8 ± 2.2 | 83.44 |

| SC4 | 4358.0 ± 24.2 | 1372.0 ± 19.5 | 0.30 | 727.0 ± 3.6 | 21.29 ± 0.16 | 29.4 ± 0.5 | 8.11 |

| SC5 | 320.0 ± 0.8 | 24.0 ± 0.3 | 0.10 | 51.0 ± 0.1 | 14.76 ± 0.06 | 49.6 ± 2.6 | 34.84 |

| SC6 | 197.0 ± 0.9 | 20.0 ± 0.7 | 0.10 | 31.0 ± 0.1 | 10.64 ± 0.08 | 47.3 ± 2.8 | 36.66 |

| SC7 | 194.0 ± 1.1 | 30.0 ± 1.0 | 0.20 | 31.0 ± 0.2 | 5.37 ± 0.05 | 20.2 ± 0.9 | 14.83 |

| SC8 | 316.0 ± 2.1 | 51.0 ± 1.0 | 0.16 | 51.0 ± 0.3 | 7.13 ± 0.05 | 31.8 ± 1.3 | 24.67 |

| SC9 | 764.0 ± 10.6 | 168.0 ± 7.7 | 0.20 | 124.0 ± 1.8 | 5.91 ± 0.04 | 30.0 ± 0.9 | 24.09 |

| SC10 | 2400.0 ± 7.2 | 750.0 ± 6.7 | 0.31 | 400.0 ± 1.2 | 15.68 ± 0.02 | 192.8 ± 1.9 | 177.12 |

However, information from SAOS and LVR primarily reflect the relatively static spatial conformation of the microstructure in the formulation, which cannot fully explain the skin feel associated with large and rapid deformations during the daily application of skin creams. Fortunately, Lissajous plots can help engineers comprehend the skin feel change during the application process. It serves as a valuable tool to understand the structural change of formulations under LAOS, effectively illustrating the relationship between stress and strain or shear rate. Given a specific strain amplitude, Lissajous curves for linear viscoelastic materials are ellipses, ideal elastic materials are diagonal lines, and Newtonian materials are circles. In plots of stress versus shear rate, Lissajous curves of elastic materials and Newtonian materials will reverse [32,33]. Figure 8 presents the Lissajous plots of SC4 and SC6. As illustrated in Figure 8a and c, both SC4 and SC6 exhibited greater elasticity (more resembling a diagonal line) at small strains, and the curves became irregular ellipses with the strain increasing, indicating increased viscous flow. Correspondingly, SC6 behaved very elastically (displaying elliptical rings) at low shear rates (Figure 8d). This elastic behavior was associated with high-stress values and generally indicated that the sample had strong buffering properties during the initial pick-up process in sensory testing. As the shear rate increased, SC6 transitioned from a symmetrical ellipse to a distorted ellipse with a thin Lissajous tail, ultimately exhibiting Newtonian characteristics in the high shear region. This transformation indicated that the microstructure of the sample was disrupted and demonstrated a shear-thinning behavior. Additionally, SC4 exhibited a superposition of stress curves at high shear rates (Figure 8b), and similar phenomena were also observed in SC2 and SC10. This phenomenon may be attributed to similarities in their emulsification systems, thickeners, oil phase components, and emulsion droplet size distribution. These products likely use similar emulsifiers (such as PEG-based or phospholipid emulsifiers), rheology modifiers (such as carbomer and xanthan gum), and oil phase ingredients like silicone oil and squalane, resulting in comparable viscoelasticity and shear-thinning behavior at high rates. Additionally, they may exhibit similar thixotropy properties, which originate from a nonlinear stress response and the stress lagging behind the shear rate. SC4, SC2, and SC10 possess less thixotropy than other samples, as a larger thixotropic ring area indicates greater thixotropy. This means that the structure breakdown and recovery due to shear in SC4, SC2, and SC10 are less dependent on time.

Lissajous plots of (a) and (b) SC4 and (c) and (d) SC6.

A batch of parameters could be obtained from Lissajous plots. The zero strain tangent modulus

Nonlinear viscoelastic parameters of SC1–SC10 obtained from Lissajous plots under the strain amplitudes of 180, 450, 700, and 1,000%

| Skin creams | γ (%) |

|

|

Δ Stiff | e 3 (Pa) |

|

|

Δ Thick | ν 3 (Pa s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 180 | 21.81 ± 0.11 | 56.49 ± 0.40 | 0.614 | 8.67 ± 0.13 | 15.43 ± 0.12 | 12.15 ± 0.05 | −0.270 | −0.82 ± 0.04 |

| 450 | 5.02 ± 0.09 | 24.78 ± 0.17 | 0.797 | 4.94 ± 0.07 | 11.22 ± 0.14 | 7.20 ± 0.21 | −0.558 | −1.01 ± 0.09 | |

| 700 | 1.49 ± 0.08 | 17.07 ± 0.05 | 0.913 | 3.90 ± 0.03 | 10.41 ± 0.16 | 5.65 ± 0.17 | −0.842 | −1.19 ± 0.08 | |

| 1,000 | 0.46 ± 0.06 | 10.81 ± 0.08 | 0.957 | 2.59 ± 0.04 | 8.43 ± 0.15 | 4.25 ± 0.05 | −0.984 | −1.05 ± 0.05 | |

| SC2 | 180 | 10.04 ± 0.16 | 35.27 ± 0.37 | 0.715 | 6.31 ± 0.13 | 18.41 ± 0.32 | 8.37 ± 0.08 | −1.200 | −2.51 ± 0.10 |

| 450 | −0.06 ± 0.03 | 14.13 ± 0.15 | 1.004 | 3.55 ± 0.05 | 10.63 ± 0.36 | 2.93 ± 0.02 | −2.628 | −1.93 ± 0.10 | |

| 700 | −0.82 ± 0.02 | 8.24 ± 0.76 | 1.100 | 2.27 ± 0.20 | 5.91 ± 0.22 | 2.18 ± 0.20 | −1.711 | −0.93 ± 0.11 | |

| 1,000 | −0.16 ± 0.26 | 5.43 ± 0.08 | 1.029 | 1.40 ± 0.09 | 5.06 ± 0.19 | 1.49 ± 0.06 | −2.396 | −0.89 ± 0.06 | |

| SC3 | 180 | 16.36 ± 0.07 | 42.45 ± 0.40 | 0.615 | 6.52 ± 0.12 | 22.85 ± 0.33 | 9.37 ± 0.13 | −1.439 | −3.37 ± 0.12 |

| 450 | 3.51 ± 0.08 | 17.23 ± 0.16 | 0.796 | 3.43 ± 0.06 | 14.83 ± 0.30 | 5.83 ± 0.13 | −1.544 | −2.25 ± 0.11 | |

| 700 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 10.90 ± 0.02 | 0.952 | 2.60 ± 0.02 | 11.04 ± 0.26 | 4.17 ± 0.17 | −1.647 | −1.72 ± 0.11 | |

| 1,000 | −0.23 ± 0.03 | 6.93 ± 0.13 | 1.033 | 1.79 ± 0.04 | 8.60 ± 0.22 | 2.90 ± 0.03 | −1.966 | −1.43 ± 0.06 | |

| SC4 | 180 | 11.08 ± 0.15 | 59.48 ± 0.41 | 0.814 | 12.10 ± 0.14 | 29.19 ± 0.98 | 12.07 ± 0.15 | −1.418 | −4.28 ± 0.28 |

| 450 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 23.10 ± 0.08 | 0.976 | 5.64 ± 0.04 | 16.47 ± 0.76 | 5.91 ± 0.10 | −1.787 | −2.64 ± 0.22 | |

| 700 | −1.02 ± 0.05 | 13.75 ± 0.21 | 1.074 | 3.69 ± 0.07 | 10.70 ± 0.53 | 4.03 ± 0.17 | −1.655 | −1.67 ± 0.18 | |

| 1,000 | −1.15 ± 0.02 | 8.09 ± 0.02 | 1.142 | 2.31 ± 0.01 | 8.70 ± 0.39 | 2.78 ± 0.05 | −2.129 | −1.48 ± 0.11 | |

| SC5 | 180 | 11.56 ± 0.10 | 33.68 ± 0.09 | 0.657 | 5.53 ± 0.05 | 6.71 ± 0.06 | 6.80 ± 0.19 | 0.013 | 0.02 ± 0.06 |

| 450 | 1.28 ± 0.04 | 13.92 ± 0.13 | 0.908 | 3.16 ± 0.04 | 4.88 ± 0.07 | 3.56 ± 0.01 | −0.371 | −0.33 ± 0.02 | |

| 700 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 8.94 ± 0.04 | 0.989 | 2.21 ± 0.02 | 4.08 ± 0.07 | 2.66 ± 0.30 | −0.534 | −0.36 ± 0.09 | |

| 1,000 | −0.27 ± 0.01 | 5.93 ± 0.06 | 1.046 | 1.55 ± 0.02 | 3.51 ± 0.07 | 1.93 ± 0.05 | −0.819 | −0.40 ± 0.03 | |

| SC6 | 180 | 8.44 ± 0.08 | 21.98 ± 0.05 | 0.616 | 3.39 ± 0.03 | 3.95 ± 0.04 | 4.44 ± 0.20 | 0.110 | 0.12 ± 0.06 |

| 450 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 9.02 ± 0.06 | 0.910 | 2.05 ± 0.02 | 2.91 ± 0.03 | 2.34 ± 0.03 | −0.244 | −0.14 ± 0.02 | |

| 700 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 6.01 ± 0.03 | 0.990 | 1.49 ± 0.01 | 2.51 ± 0.04 | 1.86 ± 0.05 | −0.349 | −0.16 ± 0.02 | |

| 1,000 | −0.11 ± 0.00 | 4.01 ± 0.02 | 1.027 | 1.03 ± 0.01 | 2.07 ± 0.03 | 1.30 ± 0.08 | −0.592 | −0.19 ± 0.03 | |

| SC7 | 180 | 3.09 ± 0.03 | 10.11 ± 0.03 | 0.694 | 1.76 ± 0.02 | 2.96 ± 0.03 | 2.60 ± 0.21 | −0.138 | −0.09 ± 0.06 |

| 450 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 4.46 ± 0.02 | 0.897 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 2.16 ± 0.03 | 1.36 ± 0.04 | −0.588 | −0.20 ± 0.02 | |

| 700 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 2.89 ± 0.03 | 0.958 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 1.75 ± 0.03 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | −0.716 | −0.18 ± 0.05 | |

| 1,000 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 1.91 ± 0.05 | 0.995 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 1.57 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.12 | −0.764 | −0.17 ± 0.04 | |

| SC8 | 180 | 5.37 ± 0.05 | 15.01 ± 0.06 | 0.642 | 2.41 ± 0.03 | 4.62 ± 0.05 | 3.45 ± 0.06 | −0.339 | −0.29 ± 0.03 |

| 450 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 6.44 ± 0.04 | 0.842 | 1.36 ± 0.02 | 3.25 ± 0.05 | 2.02 ± 0.01 | −0.609 | −0.31 ± 0.02 | |

| 700 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 4.29 ± 0.03 | 0.944 | 1.01 ± 0.01 | 2.74 ± 0.05 | 1.57 ± 0.18 | −0.745 | −0.29 ± 0.06 | |

| 1,000 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 2.82 ± 0.03 | 0.996 | 0.70 ± 0.01 | 2.39 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.05 | −0.867 | −0.28 ± 0.03 | |

| SC9 | 180 | 6.47 ± 0.04 | 15.37 ± 0.14 | 0.579 | 2.23 ± 0.05 | 4.30 ± 0.06 | 3.19 ± 0.11 | −0.348 | −0.28 ± 0.04 |

| 450 | 1.62 ± 0.03 | 6.64 ± 0.04 | 0.756 | 1.26 ± 0.02 | 3.08 ± 0.04 | 2.02 ± 0.11 | −0.525 | −0.27 ± 0.04 | |

| 700 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 4.37 ± 0.03 | 0.883 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 2.62 ± 0.05 | 1.57 ± 0.18 | −0.669 | −0.26 ± 0.06 | |

| 1,000 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 2.87 ± 0.03 | 0.930 | 0.67 ± 0.01 | 2.17 ± 0.04 | 1.27 ± 0.06 | −0.709 | −0.23 ± 0.03 | |

| SC10 | 180 | 24.10 ± 0.18 | 83.82 ± 1.16 | 0.712 | 14.93 ± 0.34 | 29.08 ± 0.58 | 15.46 ± 0.18 | −0.881 | −3.41 ± 0.19 |

| 450 | 2.73 ± 0.10 | 30.67 ± 4.31 | 0.911 | 6.99 ± 1.10 | 17.93 ± 0.39 | 8.30 ± 0.09 | −1.160 | −2.41 ± 0.12 | |

| 700 | −0.07 ± 0.06 | 20.95 ± 0.11 | 1.003 | 5.26 ± 0.04 | 14.45 ± 0.37 | 6.29 ± 0.10 | −1.297 | −2.04 ± 0.12 | |

| 1,000 | −1.04 ± 0.05 | 13.00 ± 0.21 | 1.080 | 3.51 ± 0.07 | 11.03 ± 0.30 | 4.44 ± 0.04 | −1.484 | −1.65 ± 0.09 |

3.4.4 Creep and creep recovery measurements

Creep and creep recovery measurements provide insights into the elastic and viscous response of skin creams, which are expected to connect with various sensory attributes. As illustrated in Figure 9, the sample first underwent a rapid instantaneous elastic response and then recovered immediately. This was followed by a delayed viscoelastic response, where the resulting deformation gradually recovered over time. Finally, a steady-state viscous response occurred, resulting in permanent deformation that could not recovered. Figure 10 shows the fitting curves of the experimental data using the Burgers four-element model composed of the Maxwell model and Kelvin model in series. From the fitting model, the instantaneous elastic modulus (G 1), the Kelvin Voigt elastic modulus (G 2), the steady-state viscosity (η 1), and the Kelvin viscosity (η 2) were obtained, as listed in Table 6. Additionally, the creep recovery parameters such as the compliance at the end of the creep test (J MAX), the compliance corresponding to irreversible deformation (J ∞), the elastic compliance corresponding to secondary recovery (J KV), the instantaneous elastic compliance (J SM), the creep recovery speed parameters (B and C) are listed in Table 7, and the contribution of each model element to the maximum deformation (expressed as percentages, J SM%, J KV%, and J ∞%), are calculated using the following equations:

Creep and creep recovery curve of SC2.

(a) and (b) Fitting curves of the experimental data obtained from the creep and creep recovery test of SC2 using the Burgers four-element model.

Creep parameters obtained from fitting the experimental data using the Burgers four-element model

| Skin creams | G 1 (Pa) | G 2 (Pa) | η 1 (Pa s) | η 2 (Pa s) | η 2/G 2 (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 6.66 ± 0.03 | 6.34 ± 0.07 | 1922.17 ± 38.46 | 103.69 ± 2.17 | 16.35 |

| SC2 | 5.58 ± 0.07 | 2.46 ± 0.03 | 424.02 ± 5.48 | 46.96 ± 1.09 | 19.09 |

| SC3 | 15.13 ± 0.16 | 5.68 ± 0.06 | 1440.20 ± 22.94 | 128.14 ± 2.25 | 22.56 |

| SC4 | 30.88 ± 0.43 | 7.20 ± 0.08 | 1361.62 ± 16.41 | 205.03 ± 3.09 | 28.48 |

| SC5 | 2.18 ± 0.01 | 3.60 ± 0.03 | 1439.59 ± 31.75 | 43.40 ± 0.95 | 12.06 |

| SC6 | 1.14 ± 0.00 | 2.14 ± 0.02 | 855.07 ± 19.03 | 20.84 ± 0.51 | 9.74 |

| SC7 | 1.48 ± 0.01 | 1.85 ± 0.02 | 538.41 ± 10.64 | 29.62 ± 0.69 | 16.01 |

| SC8 | 1.96 ± 0.01 | 1.51 ± 0.01 | 536.24 ± 11.24 | 24.36 ± 0.49 | 16.13 |

| SC9 | 1.96 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 181.24 ± 2.47 | 21.93 ± 0.44 | 22.84 |

| SC10 | 14.22 ± 0.15 | 7.36 ± 0.08 | 2163.34 ± 41.75 | 115.63 ± 2.63 | 15.71 |

Creep recovery parameters obtained from fitting the experimental data using the equations

| Skin creams | J MAX (Pa−1) × 10−3 | J ∞ (Pa−1) × 10−3 | J KV (Pa−1) × 10−3 | J SM (Pa−1) × 10−3 | B | C | J SM (%) | J KV (%) | J ∞ (%) | R (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC1 | 4.44 | 1.59 | 1.79 | 1.06 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 23.87 | 40.32 | 35.81 | 64.19 |

| SC2 | 12.32 | 6.51 | 3.88 | 1.93 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 15.67 | 31.49 | 52.84 | 47.16 |

| SC3 | 4.30 | 1.97 | 1.96 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.51 | 8.60 | 45.58 | 45.81 | 54.19 |

| SC4 | 3.76 | 1.52 | 2.01 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 6.12 | 53.46 | 40.43 | 59.57 |

| SC5 | 9.14 | 3.55 | 2.05 | 3.54 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 38.73 | 22.43 | 38.84 | 61.16 |

| SC6 | 16.41 | 6.97 | 2.26 | 7.18 | 0.06 | 0.51 | 43.75 | 13.77 | 42.47 | 57.53 |

| SC7 | 17.04 | 6.09 | 5.78 | 5.17 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 30.34 | 33.92 | 35.74 | 64.26 |

| SC8 | 16.56 | 7.39 | 5.31 | 3.86 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 23.31 | 32.07 | 44.63 | 55.37 |

| SC9 | 30.68 | 18.47 | 10.05 | 2.16 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 7.04 | 32.76 | 60.20 | 39.80 |

| SC10 | 3.27 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.49 | 22.94 | 39.14 | 37.92 | 62.08 |

SC4 exhibited the largest G 1, indicating stronger molecular cohesion within the formulation. Meanwhile, SC4 showed a relatively high G 2, demonstrating better resistance to deformation. In addition, SC10, SC1, SC3, SC4, and SC5 also displayed good abilities to resist deformation caused by external stress, as evidenced by their η 1 values being an order of magnitude higher than those of the other skin creams. The ratio of η 2/G 2 represented the response speed of the sample to instantaneous constant stress, with smaller values indicating less response times, and SC6 possessed the fastest response speed. Notably, SC9 had the lowest reversion rate (R% = 39.80%) among all the skin creams, suggesting that the internal structure could be easily disrupted under low stress, which was in agreement with its relatively low σ y value observed in the flow curve and oscillatory amplitude sweep.

3.4.5 Compression measurements

Compression measurements on the rheometer provide an alternative method for testing spreadability compared to the texture analyzer. Similar curves (Figure 11a) to those obtained with the texture analyzer can also be generated using the rheometer, requiring less material. The spreadability obtained from the rheometer was calculated as the integral of the downward compression of the parallel plate on the force–time curve. Figure 11b shows that the relationship between the CoF for 40 min and the rheological spreadability could be well-fitted using a quadratic polynomial. Notably, the CoF for other time intervals could also be well-fitted with a quadratic polynomial. It could be inferred that a higher CoF corresponded to more work required to spread the skin cream. However, it should be emphasized that the absolute values of spreadability obtained from the texture analyzer and the rheometer may be different. In this study, spreadability obtained from the texture analyzer was utilized for subsequent statistical analysis.

![Figure 11

(a) Force–time curve of SC3 obtained from the compression measurement using the rheometer and (b) the fitting line of the experimental data [CoF (40 min)-spreadability (obtained from the rheometer)] using a quadratic polynomial.](/document/doi/10.1515/arh-2025-0044/asset/graphic/j_arh-2025-0044_fig_011.jpg)

(a) Force–time curve of SC3 obtained from the compression measurement using the rheometer and (b) the fitting line of the experimental data [CoF (40 min)-spreadability (obtained from the rheometer)] using a quadratic polynomial.

3.5 Pearson’s correlation analysis

Pearson’s correlation analyses between instrumental parameters and sensory attributes visualized by the heatmap is shown in Figure 12, and Table S3 presents some typical associations with detailed Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCC). PCC ranges from −1 to 1, indicating strong negative and positive linear correlation, respectively. Several texture parameters demonstrated strong associations with sensory attributes. For example, texture adhesiveness was positively correlated with Thickness, Firmness, Peaking, and Cushion, with PCCs of 0.947, 0.907, 0.922, and 0.936, respectively. Conversely, it was negatively correlated with Spreadability and Product watery, with PCCs of −0.880 and −0.830. Additionally, texture spreadability was positively correlated with Thickness, Firmness, and Cushion, while being negatively correlated with sensory Spreadability and Skin watery (instant and 2 min), with PCCs of 0.805, 0.745, 0.788, −0.788, −0.747, and −0.810, respectively. The relationship between friction and sensory attributes was also evident. The CoF was positively correlated with Thickness, Firmness, Peaking, and Cushion within 5–40 min, and negatively correlated with Spreadability and Skin watery (instant and 2 min) within 15–35 min. Although previous studies have reported that hydration from moisturizers could reduce smoothness during sample application [2], but unfortunately, no significant correlation between CoF and the skin smoothness of the products was observed in this research.

Pearson’s correlation analyses between instrumental parameters and sensory attributes visualized by the heatmap. Blue and red colors represent significant negative and positive correlations, respectively. Darker color represents stronger correlations.

Rheological testing simulated the actual application process of skincare products to some extent, and this study revealed that many rheological parameters were linearly correlated with sensory attributes. Generally, the relevancy between parameters obtained from LAOS (Lissajous plots) and sensory attributes was stronger than that obtained from SAOS (oscillatory amplitude sweep measurements), further verifying that high shear strain was more representative of the smearing application process. Notably, η 0 obtained from flow curve fitting showed significant correlations with sensory attributes such as Thickness, Firmness, Peaking, Pick up, Cushion, and Spreadability, indicating that it effectively described the skin feel changes from a quiescent state to initial product contact. These findings suggested that steady-state parameters could effectively describe early skin feel. Furthermore, sensory attributes including Thickness, Firmness, Peaking, Pick up, and Cushion were positively correlated with creep parameters, but negatively correlated with creep recovery parameters. This is understandable, as materials with weak interactions tend to exhibit fast creep and slow creep recovery behavior.

3.6 ML analysis

To further clarify the connection between instrumental parameters and sensory attributes, we developed predictive models for the sensory attributes of skin creams using various ML algorithms, such as KNN, LightGBM, AdaBoost, RF, CatBoost, and BR. The models were evaluated based on R 2, MAPE, MAE, and RMSE, with the goal of selecting the best prediction algorithm for sensory attributes that are suitable for different stages of product use. Accuracy was calculated based on the formula for the probability of landing points to conveniently evaluate the model fitting results. The results are presented in Table 8, and the corresponding regression plots (with 95% confidence intervals) are shown in Table S4. The overall performance of the predictive models demonstrated a high level of accuracy across a wide range of sensory attributes. Notably, KNN, AdaBoost, and LightGBM stood out as the best-performing algorithms, achieving R 2 values of 0.96 or higher for most attributes, coupled with low MAPE, MAE, and RMSE values. For instance, KNN consistently delivered perfect or near-perfect predictions for several texture and tactile-related attributes, such as Fineness of texture (R 2 = 0.99, MAPE = 0.72%) and Spreadability (R 2 = 1.00, MAPE = 0.33%), highlighting its suitability for localized sensory attributes. Similarly, AadBoost also showed significant success for attributes like Firmness (R 2 = 1.00, MAPE = 0.57%) and Skin smoothness (instant) (R 2 = 0.96, MAPE = 0.43%), emphasizing its ability to integrate weak learners into a strong predictive framework. In addition, LightGBM also exhibited outstanding performance, particularly for attributes like Reflection of product and skin oiliness (instant), with R² values of 1.00 and 0.98, respectively. These algorithms effectively predicted both immediate and long-term sensory experiences associated with skin creams, not only confirming the feasibility of using ML models to predict sensory attributes with high accuracy but also underscoring the importance of algorithm selection based on the specific characteristics of each sensory attribute.

Optimal prediction algorithm for each sensory attribute dimension based on the screening criteria

| Sensory attributes list | Best fit algorithm | R 2 | MAPE (%) | MAE | RMSE | Accuracy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Fineness of texture | KNN | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 100 |

| Reflection of product | LightGBM | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 98.9 | |

| Thickness/Flow | KNN | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 92.4 | |

| Finger contact for the first time | Bounce | KNN | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 100 |

| Firmness | AdaBoost | 1.00 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 100 | |

| Peaking | KNN | 1.00 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 100 | |

| Pick up | RF | 0.99 | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 100 | |

| Cushion | KNN | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 92.8 | |

| In-use sensory attributes | Spreadability | KNN | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 100 |

| Product watery | AdaBoost | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 100 | |

| Product greasiness | AdaBoost | 0.99 | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 98.9 | |

| After-use sensory attributes | Cooling | LightGBM | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 100 |

| Skin smoothness (instant) | AdaBoost | 0.96 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 97.4 | |

| Skin stickiness (instant) | AdaBoost | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 100 | |

| Skin residue (instant) | BR | 0.99 | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 97.0 | |

| Skin watery (instant) | KNN | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 100 | |

| Skin oiliness (instant) | LightGBM | 0.98 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 100 | |

| Skin smoothness (2 min) | AdaBoost | 0.97 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 100 | |

| Skin stickiness (2 min) | KNN | 0.91 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 100 | |

| Skin residue (2 min) | AdaBoost | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 85.7 | |

| Skin watery (2 min) | AdaBoost | 0.98 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 100 | |

| Skin oiliness (2 min) | KNN | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 89.4 | |

The predictive performance of the above-established model was evaluated using four additional skin care products, with the outcomes depicted in Figure 13. Upon comparing the model’s prediction values (orange dots) with actual measurements (blue dots with error bars), we found, in many instances, that the predicted values fell within those ranges of actual sensory scores, affirming the model’s reliability. The occasional deviations were likely due to sensory evaluation errors and potential model limitations. The residual plots (Figure 14) presented provided a critical evaluation of our model’s predictive capabilities by comparing the residual from the training set (represented by blue points) with those from the testing set (represented by red points). A random scatter of residuals around the zero line across sensory attributes suggested that the model was well-calibrated, with no systematic prediction errors. However, any discernible patterns or trends in the residuals could indicate areas where the model’s assumption does not align with the underlying structure of the data. Our analysis revealed that, while there is generally randomness in the distribution of residuals, there are instances where the residuals from the testing set exceed those from the training set. This phenomenon could be attributed to the following reasons: (1) The model may over-fit the training data, capturing noise or specific patterns that do not generalize to the testing set; (2) The training and testing sets may have different underlying distributions, causing the model to perform poorly on the testing set; (3) A small testing set may not adequately represent the overall data distribution, leading to higher residuals and performance instability; (4) The testing set might contain more noise, making it harder for the model to fit the data. Additionally, the magnitude of residuals across different sensory attributes should ideally remain consistent for a model considered robust. Significant deviations suggest that the model’s predictive performance varies across attributes, potentially due to the difference in complexity or the nature of the data associated with each attribute.

Comparison plots of predicted and actual evaluation scores of sensory attributes for four skincare products.

Comparison plots of the training set residuals and the testing set residuals: (a) RMSE, (b) MAPE, and (c) MAE.

To address the above issues, we propose several future strategies. First, simplifying the model to reduce the risk of over-fitting or increasing its complexity if under-fitting is suspected could be considered. Second, ensuring that both the training and testing datasets are representative of the same distribution could provide a more accurate assessment of the model’s generalization capabilities. Third, a reevaluation of the feature selection and engineering processes may be necessary to ensure that the model is informed by the most relevant data. Finally, exploring different modeling approaches could uncover methods better suited to the data’s characteristics. Furthermore, future work should also focus on addressing limitations such as the variability introduced by individual skin types, experimental conditions, and the dynamic and time-dependent nature of certain attributes (e.g., Skin residue or Skin oiliness). Incorporating a wider range of instrumental parameters, temporal data, and user demographics, along with advanced hyper-parameter optimization, further enhances model robustness and generalizability. In conclusion, while the established model demonstrated competent predictive performance, there is much room for refinement to enhance its reliability and consistency across sensory attributes. This study lays the foundation for data-driven approaches in sensory evaluation and product optimization, enabling more efficient and precise development of skincare products.

4 Conclusion

This study successfully established an ML-based model to predict sensory attribute scores of skin creams using instrumental parameters derived from texture, tribological, and rheological analyses. The results demonstrated that the model achieved high predictive accuracy for the majority of sensory dimensions, with 80% of the attributes achieving over 95% accuracy, and KNN, AdaBoost, and LightGBM turned out to be algorithms with better performance for most sensory attributes. Additionally, the testing set confirmed the model’s stability and applicability, with predicted sensory scores aligning closely with actual values. However, it cannot be ignored that model overfitting, discrepancies between training and testing data distributions, an unrepresentative testing set, or increased noise in the testing data may cause the residuals from the testing set to exceed those from the training set. Therefore, further refinement is needed to improve the model’s reliability and consistency across all sensory attributes. This research highlights the potential of data-driven approaches in enhancing sensory evaluation processes and offers a more efficient, accurate, and standardized method for product development and optimization in the skincare industry.

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank Haotu Enterprise Management Consulting (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. for providing us with sensory evaluation support.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Jingru He – conceptualization, project administration, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization and writing-original draft; Xuedan Qian – project administration, methodology, formal analysis, validation, visualization and writing – review & editing; Hu Huang – conceptualization, project administration, supervision and writing – review & editing; Bao Lin, Jun Zhang and Chunxiao Zhang – methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, resources and software; Yuyan Chen – resources. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Ahmed IA, Mikail MA, Zamakshshari N, Abdullah AH. Natural anti-aging skincare: role and potential. Biogerontology. 2020;21(3):293–310. 10.1007/s10522-020-09865-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Guest S, McGlone F, Hopkinson A, Schendel ZA, Blot K, Essick G. Perceptual and sensory-functional consequences of skin care products. J Cosmet Dermatological Sci Appl. 2013;3(1):66–78. 10.4236/jcdsa.2013.31A010.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Vergilio MM, de Freitas ACP, da Rocha-Filho PA. Comparative sensory and instrumental analyses and principal components of commercial sunscreens. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(2):729–39. 10.1111/jocd.14113.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Roso A, Aubert A, Cambos S, Vial F, Schäfer J, Belin M, et al. Contribution of cosmetic ingredients and skin care textures to emotions. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2024;46:262–83. 10.1111/ics.12928.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Gabriel D, Merat E, Jeudy A, Cambos S, Chabin T, Giustiniani J, et al. Emotional effects induced by the application of a cosmetic product: A real-time electrophysiological evaluation. Appl Sci. 2021;11(11):4766. 10.3390/app11114766.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Evangelista M, Mota S, Almeida IF, Pereira MG. Usage patterns and self-esteem of female consumers of antiaging cosmetic products. Cosmetics. 2022;9(3):49. 10.3390/cosmetics9030049.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Cyriac F, Yi TX, Chow PS. Predicting textural attributes and frictional characteristics of topical formulations based on non-linear rheology. Biotribology. 2023;35–36:100249. 10.1016/j.biotri.2023.100249.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zhou WR, He JB, Jiao Q, Wang ZD, Su QQ, Jia Y. Research progress of the correlation between sensory evaluation and instrumental analysis of cosmetics in O/W emulsion system. China Surfactant Detergent Cosmetics. 2024;54(3):344–52. 10.3969/j.issn.2097-2806.2024.03.014.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Tai A, Bianchini R, Jachowicz J. Texture analysis of cosmetic/pharmaceutical raw materials and formulations. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014;36(4):291–304. 10.1111/ics.12125.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Vieira GS, Lavarde M, Freville V, Rocha-Filho PA, Pense-Lheritier AM. Combining sensory and texturometer parameters to characterize different type of cosmetic ingredients. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2020;42(2):156–66. 10.1111/ics.12598.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Gilbert L, Picard C, Savary G, Grisel M. Rheological and textural characterization of cosmetic emulsions containing natural and synthetic polymers: relationships between both data. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2013;421:150–63. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.01.003.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ahuja A, Lu J, Potanin A. Rheological predictions of sensory attributes of lotions. J Texture Stud. 2019;50(4):295–305. 10.1111/jtxs.12401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Skedung L, Buraczewska-Norin I, Dawood N, Rutland MW, Ringstad L. Tactile friction of topical formulations. Skin Res Technol. 2016;22(1):46–54. 10.1111/srt.12227.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Jiang T, Zhang C, Zhang ZW, Zhang WP, Fang B. Study on rheological properties and melting sensation of oil-in-water creams. China Surfactant Detergent Cosmetics. 2019;49(11):705–10. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1803.2019.11.002.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Lin MY, Yu WH. Study of the correlations between the sensory characteristics of elastic foundation creams and their textural parameters. China Surfactant Detergent Cosmetics. 2021;51(3):208–26. 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1803.2021.03.007.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhou ZF, Meng X, Gong SZ. Correlation study between the results of texture analyzer testing of creams with different anionic emulsifier systems and sensory evaluation. J Guangdong Ind Polytechnic. 2022;21(2):6–10. 10.13285/j.cnki.gdqgxb.2022.0017.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Timm K, Myant C, Nuguid H, Spikes HA, Grunze M. Investigation of friction and perceived skin feel after application of suspensions of various cosmetic powders. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012;34(5):458–65. 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2012.00734.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Yarovaya L, Waranuch N, Wisuitiprot W, Khunkitti W. Correlation between sensory and instrumental characterization of developed sunscreens containing grape seed extract and a commercial product. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2022;44(5):569–87. 10.1111/ics.12807.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Cyriac F, Yi TX, Chow PS, Macbeath C. Tactile friction and rheological studies to objectify sensory properties of topical formulations. J Rheol. 2022;66(2):305–26. 10.1122/8.0000341.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gilbert L, Savary G, Grisel M, Picard C. Predicting sensory texture properties of cosmetic emulsions by physical measurements. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2013;124:21–31. 10.1016/j.chemolab.2013.03.002.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Mahesh B. Machine learning algorithms – a review. Int J Sci Res (IJSR). 2020;9(1):381–6. 10.21275/ART20203995.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Black JE, Kueper JK, Williamson TS. An introduction to machine learning for classification and prediction. Fam Pract. 2023;40(1):200–4. 10.1093/fampra/cmac104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Xin H, Virk AS, Virk SS, Akin-Ige F, Amin S. Applications of artificial intelligence and machine learning on critical materials used in cosmetics and personal care formulation design. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;73:101847. 10.1016/j.cocis.2024.101847.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Shim J, Lim JM, Park SG. Machine learning for the prediction of sunscreen sun protection factor and protection grade of UVA. Exp Dermatol. 2019;28(7):872–4. 10.1111/exd.13958.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Goussard V, Duprat F, Ploix JL, Dreyfus G, Nardello-Rataj V, Aubry JM. A new machine-learning tool for fast estimation of liquid viscosity. Application to cosmetic oils. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60(4):2012–23. 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Ragno A, Baldisserotto A, Antonini L, Sabatino M, Sapienza F, Baldini E, et al. Machine learning data augmentation as a tool to enhance quantitative composition-activity relationships of complex mixtures. A new application to dissect the role of main chemical components in bioactive essential oils. Molecules. 2021;26(20):6279. 10.3390/molecules26206279.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Tseng YJ, Chuang PJ, Appell M. When machine learning and deep learning come to the big data in food chemistry. ACS Omega. 2023;8(18):15854–64. 10.1021/acsomega.2c07722.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Ali A, Ringstad L, Skedung L, Falkman P, Wahlgren M, Engblom J. Tactile friction of topical creams and emulsions: Friction measurements on excised skin and VitroSkin using ForceBoard. Int J Pharm. 2022;615:121502. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121502.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Moravkova T, Filip P. The influence of emulsifier on rheological and sensory properties of cosmetic lotions. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2013;2013(1):168503. 10.1155/2013/168503.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lee JCW, Porcar L, Rogers SA. Recovery rheology via rheo-SANS: Application to step strains under out-of-equilibrium conditions. AIChE J. 2019;65:e16797. 10.1002/aic.16797.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Wang SH, Gu HY, Xia YZ, He ZG. The recovery process of the coastal mud after being sheared by external loads. Appl Ocean Res. 2024;142:103846. 10.1016/j.apor.2023.103846.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Hyun K, Wilhelm M, Klein CO, Cho KS, Nam JG, Ahn KH, et al. A review of nonlinear oscillatory shear tests: Analysis and application of large amplitude oscillatory shear (LAOS). Prog Polym Sci. 2011;36(12):1697–753. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ozkan S, Alonso C, McMullen RL. Rheological fingerprinting as an effective tool to guide development of personal care formulations. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2020;42(6):536–47. 10.1111/ics.12628.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Lie symmetry analysis of bio-nano-slip flow in a conical gap between a rotating disk and cone with Stefan blowing

- Mathematical modelling of MHD hybrid nanofluid flow in a convergent and divergent channel under variable thermal conductivity effect

- Advanced ANN computational procedure for thermal transport prediction in polymer-based ternary radiative Carreau nanofluid with extreme shear rates over bullet surface

- Effects of Ca(OH)2 on mechanical damage and energy evolution characteristics of limestone adsorbed with H2S

- Effect of plasticizer content on the rheological behavior of LTCC casting slurry under large amplitude oscillating shear

- Studying the role of fine materials characteristics on the packing density and rheological properties of blended cement pastes

- Deep learning-based image analysis for confirming segregation in fresh self-consolidating concrete

- MHD Casson nanofluid flow over a three-dimensional exponentially stretching surface with waste discharge concentration: A revised Buongiorno’s model

- Rheological behavior of fire-fighting foams during their application – a new experimental set-up and protocol for foam performance qualification

- Viscoelastic characterization of corn starch paste: (II) The first normal stress difference of a cross-linked waxy corn starch paste

- An innovative rheometric tool to study chemorheology

- Effect of polymer modification on bitumen rheology: A comparative study of bitumens obtained from different sources

- Rheological and irreversibility analysis of ternary nanofluid flow over an inclined radiative MHD cylinder with porous media and couple stress

- Rheological analysis of saliva samples in the context of phonation in ectodermal dysplasia

- Analytical study of the hybrid nanofluid for the porosity flowing through an accelerated plate: Laplace transform for the rheological behavior

- Brief Report

- Correlations for friction factor of Carreau fluids in a laminar tube flow

- Special Issue on the Rheological Properties of Low-carbon Cementitious Materials for Conventional and 3D Printing Applications

- Rheological and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled coarse aggregate from the demolition of large panel system buildings

- Effect of the combined use of polyacrylamide and accelerators on the static yield stress evolution of cement paste and its mechanisms

- Special Issue on The rheological test, modeling and numerical simulation of rock material - Part II