Abstract

To improve the utilization rate of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ash and achieve resource recycling, this article conducted research on grinding MSWI ash into fine powder for use as a concrete admixture. Initially, the physical and chemical properties of the MSWI ash micro-powder were tested. Subsequently, different amounts of MSWI ash powder concrete were prepared. The macro and micro properties of the concrete were then tested. Finally, a life cycle assessment was utilized to evaluate and compare ordinary concrete with MSWI ash micro-powder concrete. The results indicate that the chemical composition of the MSWI ash micro-powder is similar to that of cement clinker. It exhibits potential hydraulicity and a slow hydration reaction, making it an active admixture suitable for concrete raw materials. With the increasing proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder, the rate of hydration reaction in concrete slows down, resulting in decreased mechanical properties. The microhardness value of the hardened cement paste in MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is lower than that of ordinary concrete. Moreover, the addition of MSWI ash micro-powder helps mitigate the environmental impact of concrete in terms of non-biological energy loss and CO2 emissions.

1 Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used building material in the world [1]. It plays an irreplaceable role in construction projects such as construction, water conservancy, highway, bridge, and tunnel. With the increase in concrete demand, the production of cement, sand, and stone has also been on the rise [2]. The mass production of commercial concrete has led to excessive sales of various concrete materials and pressure on the natural environment. China has announced efforts to peak carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 [3]. Based on this, experts and scholars such as Poon, CS, and Xiao Jianzhuang have carried out research on the application of solid waste instead of some building materials to concrete and proved its feasibility [4,5,6].

According to statistics from the National Bureau of Statistics on garbage removal, the amount of municipal solid waste removed in China has increased from 134.70 million tons in 2001 to 163.95 million tons in 2011, and then to 267.08 million tons in 2021 [7]. The accumulation of municipal solid waste and finding appropriate ways to manage it have become significant challenges hindering the sustainable and healthy development of China. Municipal solid waste incineration is considered the most favorable treatment method, with 80% of the substances produced after incineration being bottom ash, and the remainder being fly ash [8]. Due to the limited reuse of fly ash and its significant environmental impact, most experimental studies have focused on bottom ash produced by waste incineration, referred to as MSWI ash.

Many scholars have conducted extensive research on the application of solid waste in concrete [9,10,11,12,13]. Waste raw materials can be used to make alkali-activated materials (sometimes called geopolymer) as the new generation of cement. There are also numerous studies on the use of MSWI ash [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Some research indicates that the chemical composition of MSWI ash in some areas is similar to that of cement clinker raw materials, making it suitable for use in concrete [21]. MSWI ash undergoes hydration reaction and volume expansion due to hydrogen. It was found that MSWI bottom ash causes both a hydration effect due to existing calcium oxide, calcium sulfate, and silica dioxide and volume expansion due to hydrogen gas evolution [22]. Weng utilized MSWI ash as a component in the concrete mixture to produce specialized aerated blocks [23], while Shi et al. substituted fine aggregate in concrete with MSWI ash and investigated its mechanical properties [24]. The research indicates that the strength of MSWI ash concrete is inferior to that of conventional concrete; however, it remains suitable for preparing concrete that satisfies basic functional requirements. Dong et al. prepared high ductility engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with MSWI as mineral admixture [25]. Liu et al. novel application of MSWIBA to produce cold-bonded aggregates (CBA) [26]. Goulouti studies have shown that MSWI has the potential to be used as building materials. Life cycle assessment (LCA) has also become an assessment tool applied to building materials [27].

This article seeks to analyze the raw materials of MSWI ash, study the physical and chemical properties of MSWI ash, grind it into micro-powder, and examine its workability and environmental impact when added to concrete as an admixture. The MSWI ash powder was added to the concrete instead of cement to prepare the specimen. The compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and elastic modulus of the MSWI ash powder concrete were tested to evaluate the effect of the MSWI ash powder on the concrete. At the same time, these concretes were tested microscopically to explain the influence of different amounts of MSWI ash powder on concrete under different water–binder ratios. Then, LCA was used to evaluate the environmental impact of MSWI ash powder to prove its usefulness.

2 Experiment

2.1 Material

The test sand used is natural washed sand from the Dahei River in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. The gravel consists of first-class granite gravel from Daqingshan, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. The cement used is P.O. 42.5 ordinary Portland cement, and the water reducer is a polycarboxylate superplasticizer. The water used meets the concrete water standard.

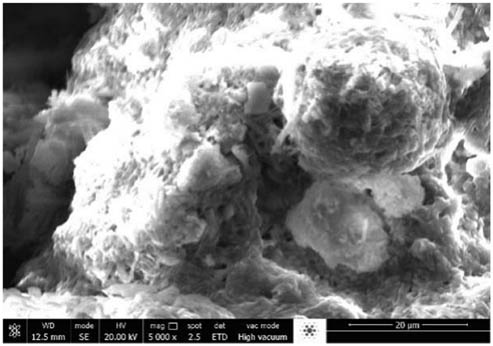

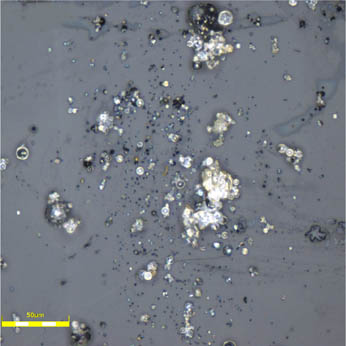

The MSWI ash micro-powder utilized in this experiment was processed from the MSWI ash of a solid waste treatment plant in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. The processing flow includes transportation, primary screening, drying, grinding, and fine screening. Untreated MSWI ash is transported from the waste disposal site to the laboratory for convenient grinding. Upon arrival, it undergoes screening to eliminate impurities such as metals and ceramics. The morphology of sieved MSWI ash particles resembles that of natural sand (Figure 1). To comprehensively analyze the morphology, microscopic particles were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Figure 2). The SEM microstructure reveals an uneven and irregular surface with numerous fine pores. After coarse screening, the MSWI ash undergoes drying at 105°C for 8 h and grinding in a planetary ball mill for 45 min at a speed of 120 rpm. Sodium silicate solid is used as a grinding aid to improve efficiency and prevent powder agglomeration. The resulting MSWI ash micro-powder undergoes a second screening using a vibrating screen machine with a 75 μm sand sieve. The collected micro-powder is then bagged, and the residue from the sieve is recovered for secondary grinding. The resulting MSWI ash micro-powder after grinding and screening appears as brownish-yellow powder particles (Figure 3).

MSWI ash.

Microscopic view of MSWI ash.

MSWI ash micro-powder.

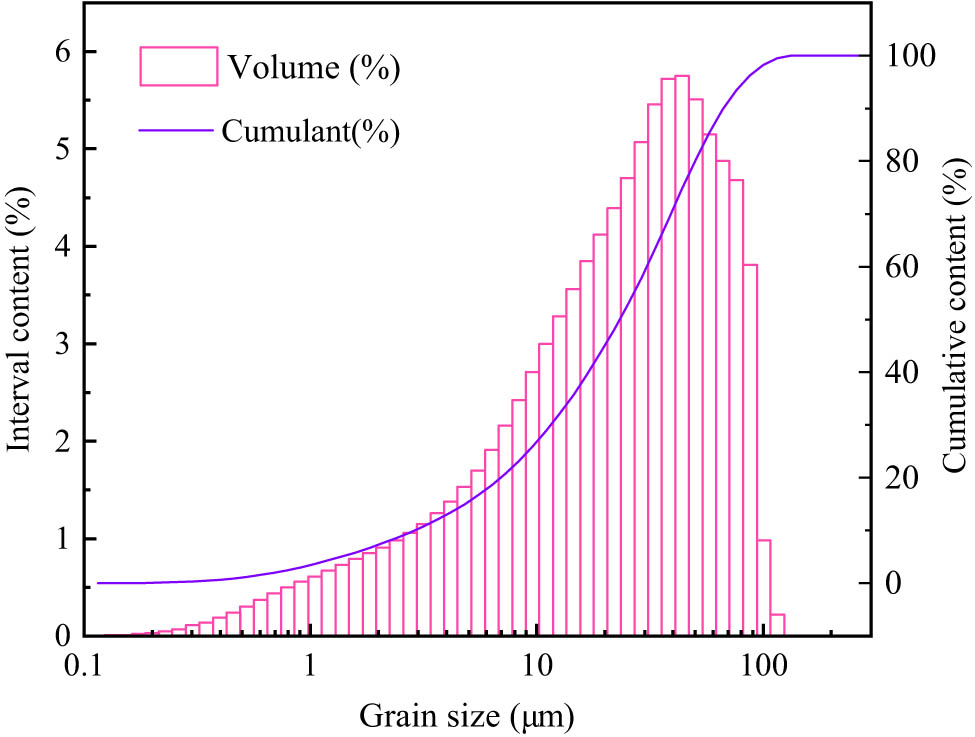

The laser particle size test indicates a refractive index of the MSWI ash micro-powder sample as 1.61-0.1i, with a medium refractive index of 1.33. The cumulative rate of particle size for 30 μm is 60%, for 50 μm is 80.1%, and the average particle size falls within the range of 30–40 μm. The distribution map of particle size accumulation is shown in Figure 4. A leaching test was conducted on the MSWI ash micro-powder to assess the presence of toxic substances. The results indicate that the concentration of each heavy metal substance complies with the “Hazardous Waste Identification Standard” (GB5085.3-2019) [28]. The chemical composition comparison of MSWI ash micro-powder and cement is presented in Table 1.

Accumulation and distribution of particle size.

Examples of chemical composition of MSWI ash and cement clinker (%)

| Item | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | Fe2O3 | MgO | K2O | SO3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSWI ash micro-powder | 35.72 | 18.81 | 28.19 | 6.23 | 3.83 | 0.48 | 2.15 |

| Cement | 21.20 | 5.21 | 64.19 | 2.78 | 1.51 | 0.48 | 2.01 |

2.2 Macroscopic test of concrete

This section aims to investigate the macroscopic properties of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete, focusing on parameters such as compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, elastic modulus, and other mechanical properties. The objective is to assess the suitability of MSWI ash micro-powder as a concrete admixture.

2.2.1 Cementitious sand specimen test

The MSWI ash micro-powder is mixed with cement in proportions of 10, 20, and 30%, based on the “Cement Mortar Strength Test Method (ISO Method)” standard (GB/T 17671-2021) [29]. The concrete mix ratio is presented in Table 2, and the cement mortar specimens are molded using a 40 mm × 40 mm × 40 mm mold.

Different dosing of MSWI ash admixture cementitious sand specimen fitting ratio

| Material | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dosage (%) | Binding material (g) | Standard sand (g) | Water (g) | |

| Cement | MSWI ash micro-powder | |||

| 0 | 450 | 0 | 1350 ± 5 | 225 ± 1 |

| 10 | 405 | 45 | 1350 ± 5 | 225 ± 1 |

| 20 | 360 | 90 | 1350 ± 5 | 225 ± 1 |

| 30 | 315 | 135 | 1350 ± 5 | 225 ± 1 |

The broken state of the MSWI ash micro-powder mortar specimens is similar to that of the ordinary cement mortar specimen, but the internal failure structure is significantly different. The compressive strength of the MSWI ash micro-powder mortar specimens is presented in Figure 5. As the blending rate of MSWI ash micro-powder increases, the compressive strength of the mortar specimens gradually decreases. The compressive strength of the 10% MSWI ash micro-powder specimen is almost the same as that of the ordinary cement mortar specimen, with only a 3.16% decrease. However, the compressive strength of the 20 and 30% specimens significantly decreases with increasing dosage. The 30% specimens show a significant decrease in compressive strength, with a reduction of 28.34%. The failure morphology of the mortar specimens confirms that the incorporation of a small amount of MSWI ash micro-powder has no effect on the strength, while an increase in the content of MSWI ash micro-powder reduces the internal hydration reaction rate of the specimens, resulting in a decrease in compressive strength.

Compressive strength of mortar specimen.

2.2.2 Mix proportion design and preparation of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete

The test mix ratio is derived and calculated using the volume method described in the “Ordinary Concrete Mix Ratio Design Specification” (JGJ 55-2011) [30]. Utilizing the adaptive method, mix ratios of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete that meet the working performance requirements, with a slump of 15–20 cm and no aggregate separation, are obtained. To investigate the influence of MSWI ash micro-powder on concrete of different strength grades, three water–binder ratios (0.2, 0.4, 0.6) were selected. Four different admixture dosages (0, 10, 20, and 30%) are set for each water–binder ratio, resulting in a total of 12 mix ratios. The basic mechanical properties of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete under different water–binder ratios and dosages are studied using these 12 mix ratios, as presented in Table 3.

Concrete mix proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder

| W/B | Dosage (%) | Water (kg) | Water reducer (kg) | Cement (kg) | Ash micro-powder (kg) | Sand (kg) | Stone (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.60 | 0 | 180 | 1.2 | 300.0 | 0.0 | 742 | 1,064 |

| 10 | 180 | 1.2 | 270.0 | 30.0 | 742 | 1,064 | |

| 20 | 180 | 2.4 | 240.0 | 60.0 | 742 | 1,064 | |

| 30 | 180 | 2.4 | 210.0 | 90.0 | 742 | 1,064 | |

| 0.40 | 0 | 170 | 2.5 | 425.0 | 0.0 | 777 | 985 |

| 10 | 170 | 2.5 | 382.5 | 42.5 | 777 | 985 | |

| 20 | 170 | 2.9 | 340.0 | 85.0 | 777 | 985 | |

| 30 | 170 | 5.1 | 297.5 | 127.5 | 777 | 985 | |

| 0.20 | 0 | 165 | 10.8 | 825.0 | 0.0 | 700 | 726 |

| 10 | 165 | 10.8 | 742.5 | 82.5 | 700 | 726 | |

| 20 | 165 | 13.0 | 660.0 | 165.0 | 700 | 726 | |

| 30 | 165 | 13.0 | 577.5 | 247.5 | 700 | 726 |

Explanation: The water is the sum of water consumption and water reducer.

The specimens used in the test were prepared according to the requirements of the “Standard for Test Methods for Mechanical Properties of Concrete” (GB/T 50081-2019) [31]. Compressive strength and splitting tensile strength were measured using cube specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm, while the elastic modulus was measured using cuboid specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 300 mm. The curing ages of the specimens were set at 7, 28, and 90 days. The choice of the 90-day age was based on previous test results of solid waste concrete with similar components, considering the longer time required for the hydraulicity of the MSWI ash micro-powder to have an effect [32,33].

2.2.3 Mechanical performance test of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete

Following the “Standard for Testing Methods for Mechanical Properties of Ordinary Concrete” (GB/T 50081-2019) [31], a 200-ton universal testing machine was utilized to test the compressive strength of 7-, 28-, and 90-day concrete cubes, with the test blocks were adjusted to dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm. Continuous uniform loading was applied in the test, with a loading rate ranging from 0.3 to 1.0 MPa·s−1. The loading rate varied based on the cube compressive strength, with specific rates detailed in the methodology. Additionally, the splitting tensile strength (100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm cubes) and elastic modulus of the 28-day and 90-day specimens were tested, and the results are presented in Table 4.

Experimental data on mechanical properties of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete (MPa)

| Types of mechanical properties | Water–binder ratio | Blending rate (%) | Curing age (days) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 28 | 90 | |||

| Compressive strength (MPa) | 0.6 | 0 | 36.58 | 39.29 | 44.47 |

| 10 | 28.93 | 36.03 | 42.22 | ||

| 20 | 29.01 | 33.51 | 41.26 | ||

| 30 | 26.85 | 32.95 | 39.92 | ||

| 0.4 | 0 | 55.94 | 59.18 | 63.60 | |

| 10 | 57.32 | 61.58 | 68.59 | ||

| 20 | 40.94 | 56.71 | 61.91 | ||

| 30 | 32.26 | 40.28 | 45.53 | ||

| 0.2 | 0 | 66.96 | 68.76 | 75.37 | |

| 10 | 61.94 | 65.12 | 72.60 | ||

| 20 | 55.16 | 60.56 | 66.17 | ||

| 30 | 53.88 | 55.64 | 58.21 | ||

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 0.6 | 0 | / | 2.67 | 2.86 |

| 10 | / | 2.54 | 2.71 | ||

| 20 | / | 2.40 | 2.57 | ||

| 30 | / | 2.21 | 2.36 | ||

| 0.4 | 0 | / | 3.02 | 3.10 | |

| 10 | / | 2.93 | 3.05 | ||

| 20 | / | 2.68 | 2.84 | ||

| 30 | / | 2.54 | 2.66 | ||

| 0.2 | 0 | / | 3.36 | 3.42 | |

| 10 | / | 3.10 | 3.21 | ||

| 20 | / | 3.03 | 3.12 | ||

| 30 | / | 2.89 | 3.03 | ||

| Splitting tensile strength (104 N·mm−2) | 0.6 | 0 | / | 2.02 | 2.28 |

| 10 | / | 1.70 | 2.02 | ||

| 20 | / | 1.58 | 1.93 | ||

| 30 | / | 1.54 | 1.87 | ||

| 0.4 | 0 | / | 2.78 | 2.83 | |

| 10 | / | 2.99 | 3.07 | ||

| 20 | / | 2.76 | 2.80 | ||

| 30 | / | 2.11 | 2.21 | ||

| 0.2 | 0 | / | 4.40 | 4.62 | |

| 10 | / | 3.70 | 3.78 | ||

| 20 | / | 3.40 | 3.57 | ||

| 30 | / | 3.33 | 3.40 | ||

As depicted in Figure 6, the compressive strength of ordinary concrete and MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is generally similar. However, as the water–binder ratio increases, the compressive strength of concrete gradually decreases. With an increase in curing age, the compressive strength of concrete with the same mix ratio tends to increase. Nonetheless, the increase in compressive strength is higher in MSWI ash micro-powder concrete compared to ordinary concrete. When the water–binder ratio remains the same, the compressive strength of concrete gradually decreases with a higher proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder. For instance, the compressive strength of specimens with a 7-day curing age, a water–binder ratio of 0.4, and a 30% MSWI ash micro-powder blending rate decreases by 42.33%. Conversely, the compressive strength of specimens with a 90-day curing age, a water–binder ratio of 0.2, and a 10% MSWI ash micro-powder blending rate decreases by only 3.68%. The addition of a small amount (10%) of MSWI ash micro-powder has minimal effect on the compressive strength of concrete specimens, with only an 8% decrease. Interestingly, the compressive strength of certain MSWI ash micro-powder concrete specimens is even higher than that of ordinary concrete (with a water–binder ratio of 0.4 and MSWI ash micro-powder content of 10%). This is attributed to the potential hydraulic properties of MSWI ash micro-powder.

The relationship between cube compressive strength and age, as well as the mixing rate of MSWI ash micro-powder.

In evaluating the growth rate of compressive strength, it is evident that MSWI ash micro-powder concrete surpasses ordinary concrete, particularly during the crucial curing periods of 7–28 days and 28–90 days. During the initial curing phase of 7–28 days, ordinary concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.6 exhibits a growth rate of 7.41%. In contrast, MSWI ash micro-powder concrete outperforms, with the 10% blending rate showcasing the highest growth rate at 24.54%. The growth rates of concrete specimens with water–binder ratios of 0.4 and 0.6 are comparable, but MSWI ash micro-powder concrete, especially at 20 and 30% blending rates, achieves growth rates of approximately 30%. The compressive strength of these specimens significantly improves from 30–40 to 50–60 MPa between the 7- to 28-day timeframe, indicating a substantial enhancement.

As the curing period extends from 28 to 90 days, the growth pattern remains consistent. Ordinary concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.6 sees a growth rate of 13.18%, while MSWI ash micro-powder concrete outpaces it, especially at 20 and 30% blending rates, exceeding 20%. For ordinary concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.4, the growth rate is 7.47%, yet MSWI ash micro-powder concrete maintains a higher growth rate. In specimens with a water–binder ratio of 0.2, both ordinary concrete and 10% MSWI ash micro-powder concrete experience significant changes, with the 10% blend exhibiting particularly notable alterations.

The overarching comparative analysis underscores that the growth rate of compressive strength in ordinary concrete lags behind that of concrete mixed with MSWI ash micro-powder admixture as the curing period progresses. This discrepancy is attributed to the faster hydration reaction rate in ordinary concrete, essentially completing within 28 days, resulting in minimal changes in compressive strength. Conversely, MSWI ash micro-powder concrete demonstrates a slower hydration reaction, leading to a gradual and sustained increase in compressive strength with the prolonged curing age.

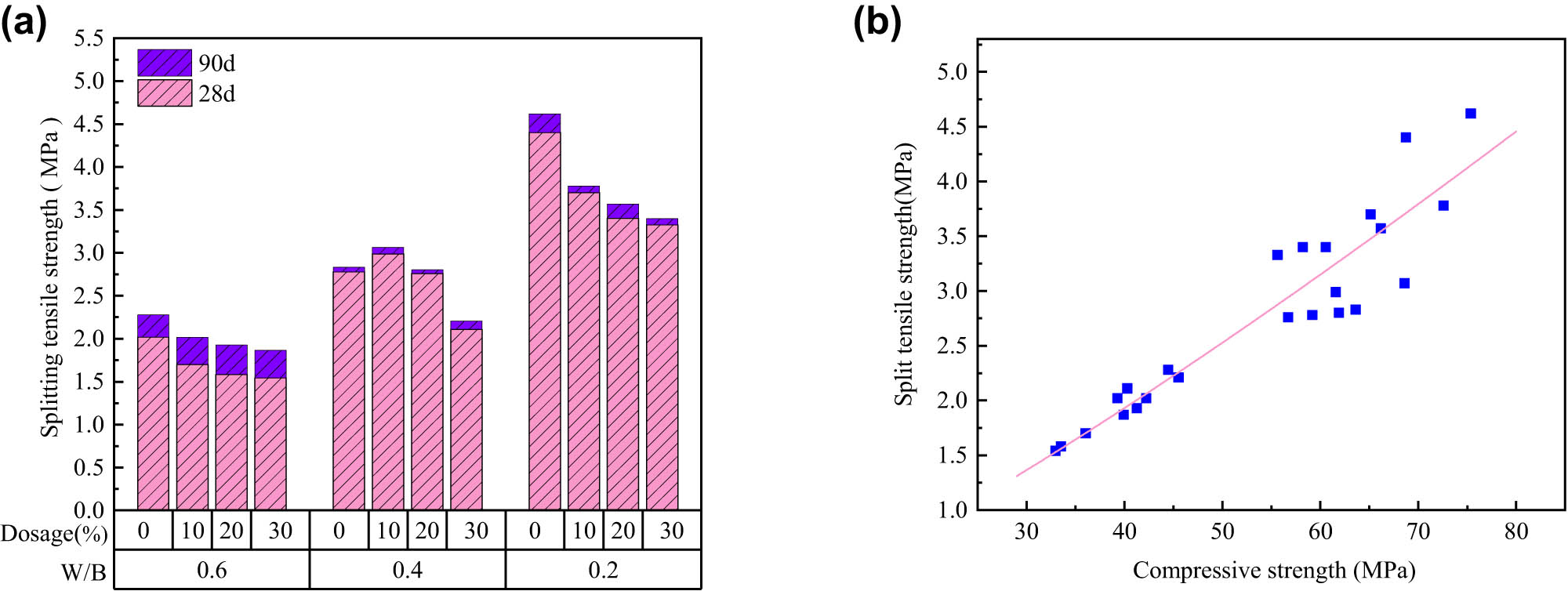

As shown in Figure 7a, the change pattern of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete aligns with that of ordinary concrete. The splitting tensile strength of concrete gradually decreases with an increase in the water–binder ratio, while it increases with the rise in curing age for concrete with the same mix ratio. Notably, the splitting tensile strength of ordinary concrete (water–binder ratio 0.6) undergoes significant changes, whereas that of medium and high-strength concrete (water–binder ratio 0.4, 0.2) shows minor variations. In instances where the water–binder ratio remains constant, the splitting tensile strength of concrete gradually decreases as the proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder admixture increases. Among these cases, the specimen with a curing age of 90 days, a water–binder ratio of 0.2, and a 30% MSWI ash micro-powder admixture rate exhibits the highest decrease of 26.41%. Conversely, the specimen with a curing age of 90 days, a water–binder ratio of 0.6, and a 10% MSWI ash micro-powder content shows the lowest decrease of 12.87%. In fact, the splitting tensile strength of certain specimens (water–binder ratio 0.4, MSWI ash micro-powder content 10%) even surpasses that of ordinary concrete.

(a) Splitting tensile strength of specimen and (b) linear fitting of compressive strength and splitting tensile strength.

Figure 7b represents the nonlinear fitting of compressive strength and splitting tensile strength data. It illustrates a nonlinear correlation between the two properties in MSWI ash micro-powder concrete, with scattered points on both sides of the regression nonlinear line. The coefficient of determination (R 2) is 0.86, indicating a good overall fit. The fitting equation is represented by formula (1):

From the analysis, it is evident that the splitting tensile strength and compressive strength of concrete specimens with the same mix ratio exhibit a nonlinear positive correlation. Points with higher compressive strength and splitting tensile strength are more scattered on both sides of the regression line, while points with lower compressive strength and splitting tensile strength are more concentrated, especially in high-strength concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.2.

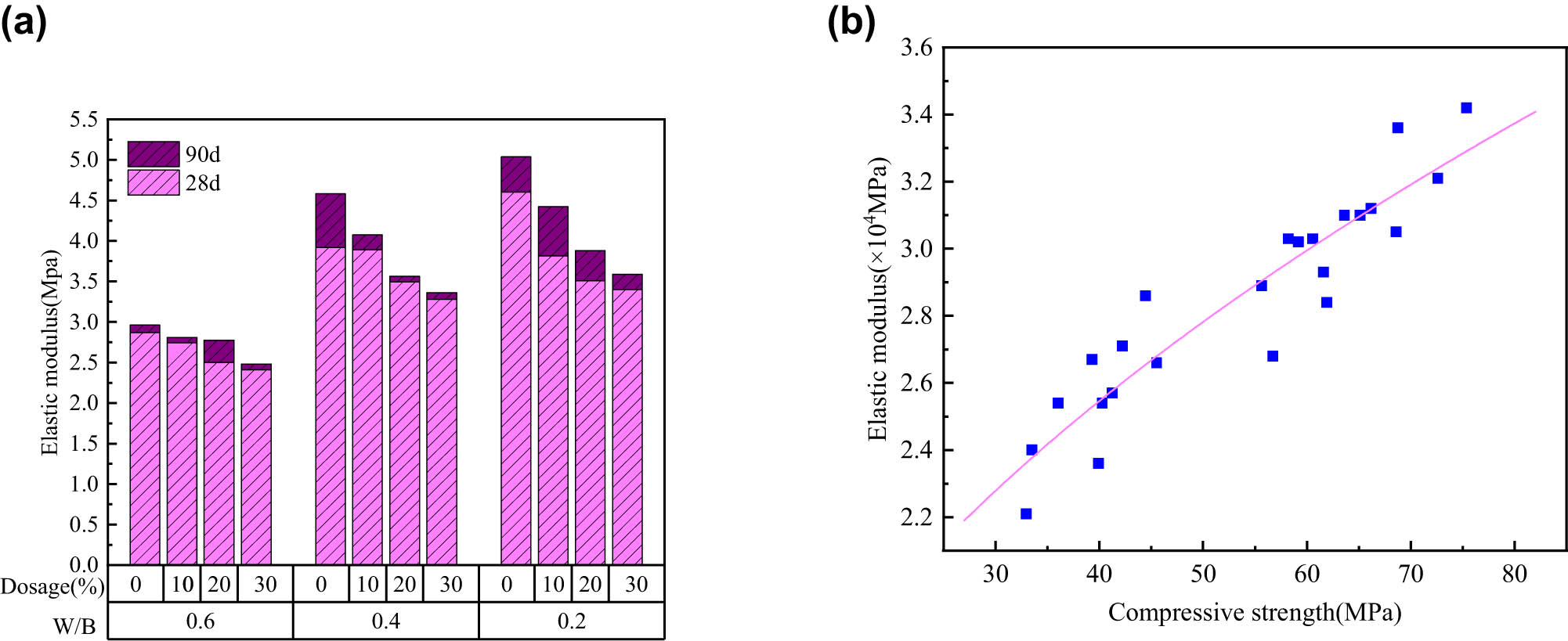

In Figure 8a, the elastic modulus values are relatively concentrated, ranging between 2 and 3 (104 N·mm−2). The elastic modulus values of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete and ordinary concrete are very similar, and their variation patterns are consistent. The elastic modulus of concrete specimens gradually decreases with an increase in water–binder ratio. Similarly, the elastic modulus increases with the rise in curing age, although the overall growth rate is small. Within the same water–binder ratio, the elastic modulus decreases as the proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder increases. The specimen with a curing age of 90 days, a water–binder ratio of 0.6, and a 30% MSWI ash micro-powder mixing rate experiences the largest decrease in elastic modulus, with a decrease of 17.48%. Conversely, the specimen with a curing age of 90 days, a water–binder ratio of 0.4, and a 10% MSWI ash micro-powder mixing rate exhibits the smallest decrease in elastic modulus, with a decrease of only 1.61%. Overall, the analysis indicates that a 30% MSWI ash micro-powder mixing rate leads to the greatest decrease in elastic modulus, approximately 15%, while a 10% micro-powder mixing rate results in the least decrease, around 5%. This suggests that the incorporation of MSWI ash micro-powder has minimal impact on the elastic modulus of concrete.

(a) Modulus of elasticity of specimen and (b) fitting relationship between compressive strength and elastic modulus.

The compressive strength and elastic modulus data are fitted using the empirical formula provided in the “Code for Design of Concrete Structures” (GB50010-2010) [34], as described by formula [35].

Upon performing fitting and analyzing the correlation, Figure 8b is obtained. From the diagram, it is evident that the compressive strength of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is positively correlated with the elastic modulus, aligning with the empirical formula of concrete structure design specifications. The scatter points are evenly distributed on both sides of the regression line, with an R² value of 0.85, indicating a good overall fit. Additionally, the analysis demonstrates that the elastic modulus and compressive strength of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete and ordinary concrete are consistent. The equation for the fitted curve is shown in formula (2):

2.3 Micromechanical analysis of concrete

In this section, the microhardness tester is employed to assess the micro-mechanical properties of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete, aiming to analyze the strength of the hardened cement paste and the ITZ and investigate the influence of MSWI ash micro-powder on the mechanical properties of concrete at a microstructural level. The specimens used in this experiment consist of 28- and 90-day cured samples of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete with different blending ratios.

The specific steps for specimen preparation and testing are as follows: first, a 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm cube specimen is cut into approximately 10 mm thick slices using a cutting machine. The surfaces of the concrete are then polished using a polishing machine. The test piece is placed smoothly on the polishing machine, and a solution prepared with a 1:1 ratio of silicon carbide and water is poured onto the polishing plate in increasing mesh sizes (320, 600, 800, 1,200, and 2,000). Each solution is applied for about 15 min until the surface of the test piece becomes smooth and flat. The same process is repeated for the other side of the specimen. After polishing, the specimen is cleaned, marked, and air-dried. It is then placed in an oven and dried at 60°C for 30 min to ensure complete dryness. The treated slice is cut into specimens with side lengths of about 30 mm and thicknesses of about 10 mm using an angle grinder or cutting machine. These prepared specimens are placed flat on the specimen tray of the microhardness tester for measurement, and the microhardness value is observed and calculated using the Vickers microhardness method.

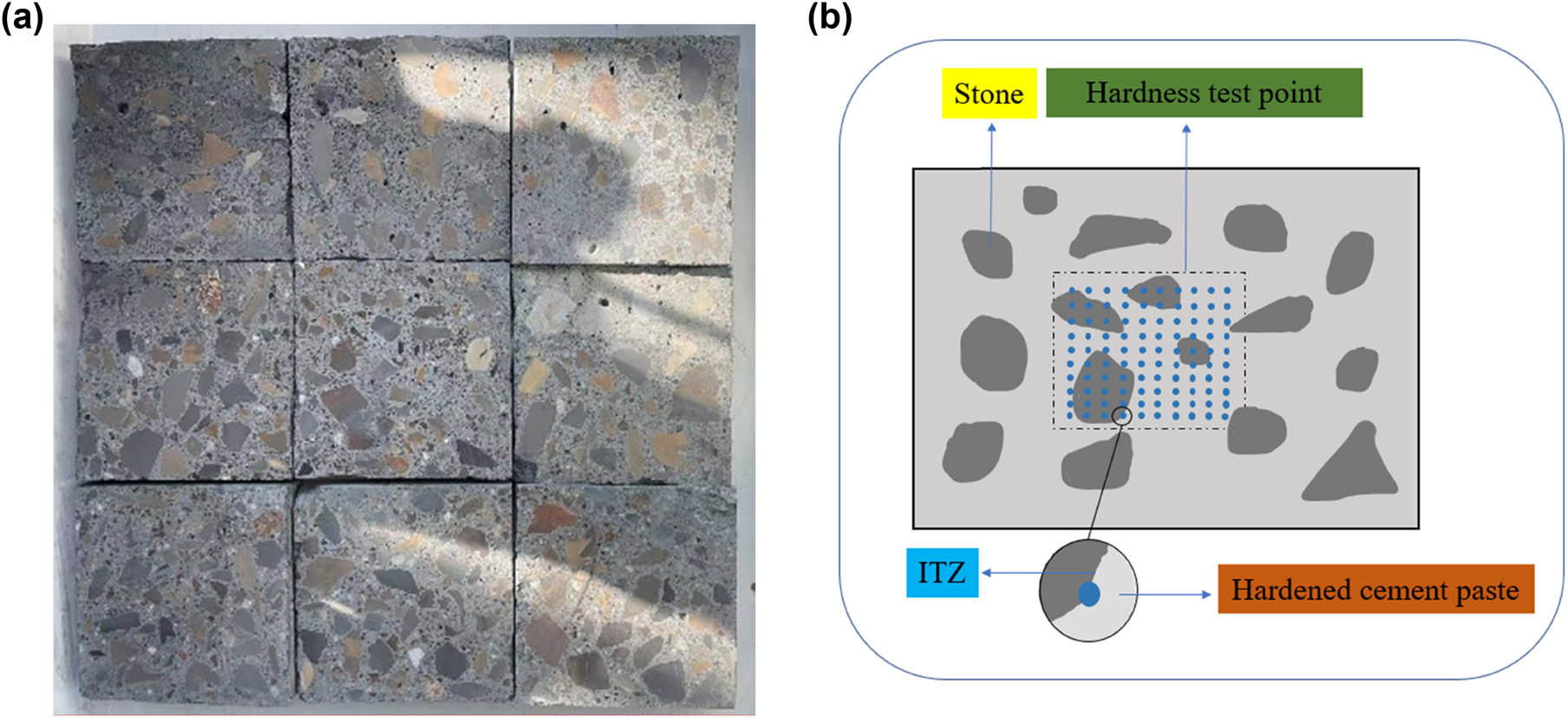

Due to the inhomogeneity of concrete materials, various arrangement methods are employed in the experiment. First, the cement stone area and aggregate area are identified and observed under a microscope. The ITZ between the aggregate and hardened cement paste is located approximately 40 μm from the aggregate area. Once the ITZ is identified, points are evenly marked in the surrounding area at intervals of 10–20 μm. Care is taken during marking to target the hardened cement paste and ITZ as much as possible, while avoiding areas that may affect the average microhardness, such as the aggregate. The specimen and point arrangement post-grinding are illustrated in Figure 9. Subsequently, confocal microscopy is used to capture images and observe the marked points. Due to the unevenness of the concrete surface, some data points may exhibit discrete variation. Data analysis eliminates potential problematic points.

(a) The specimen after grinding and (b) arrangement method for microhardness testing.

The test was conducted using Vickers microhardness calculation. The principle of Vickers microhardness involves pressing a 136° diamond quadrangular pyramid indenter into the surface of the sample under a test force of 100–200 g. After a specific duration, the test force is withdrawn, and the diagonal length of the indentation is measured. Subsequently, the microhardness test value is obtained by referencing the corresponding table correlating the diagonal length with the microhardness value.

In this experiment, a total of 24 specimens are arranged, including different curing ages (28 and 90 days), water–binder ratios (0.6, 0.4, 0.2), and blending ratios of MSWI ash micro-powder (0, 10, 20, and 30%). To clearly distinguish the microhardness differences between the ITZ and the hardened cement paste area, 100 points are designated for observation and photography using a microscope for each specimen.

The micro-morphology of the ITZ and hardened cement paste exhibits similarities, but the indentation in the ITZ appears deeper. Indentation marks are not clearly visible on the aggregate due to the insufficient pressure of the indenter to leave distinct marks on hard materials like sand and gravel.

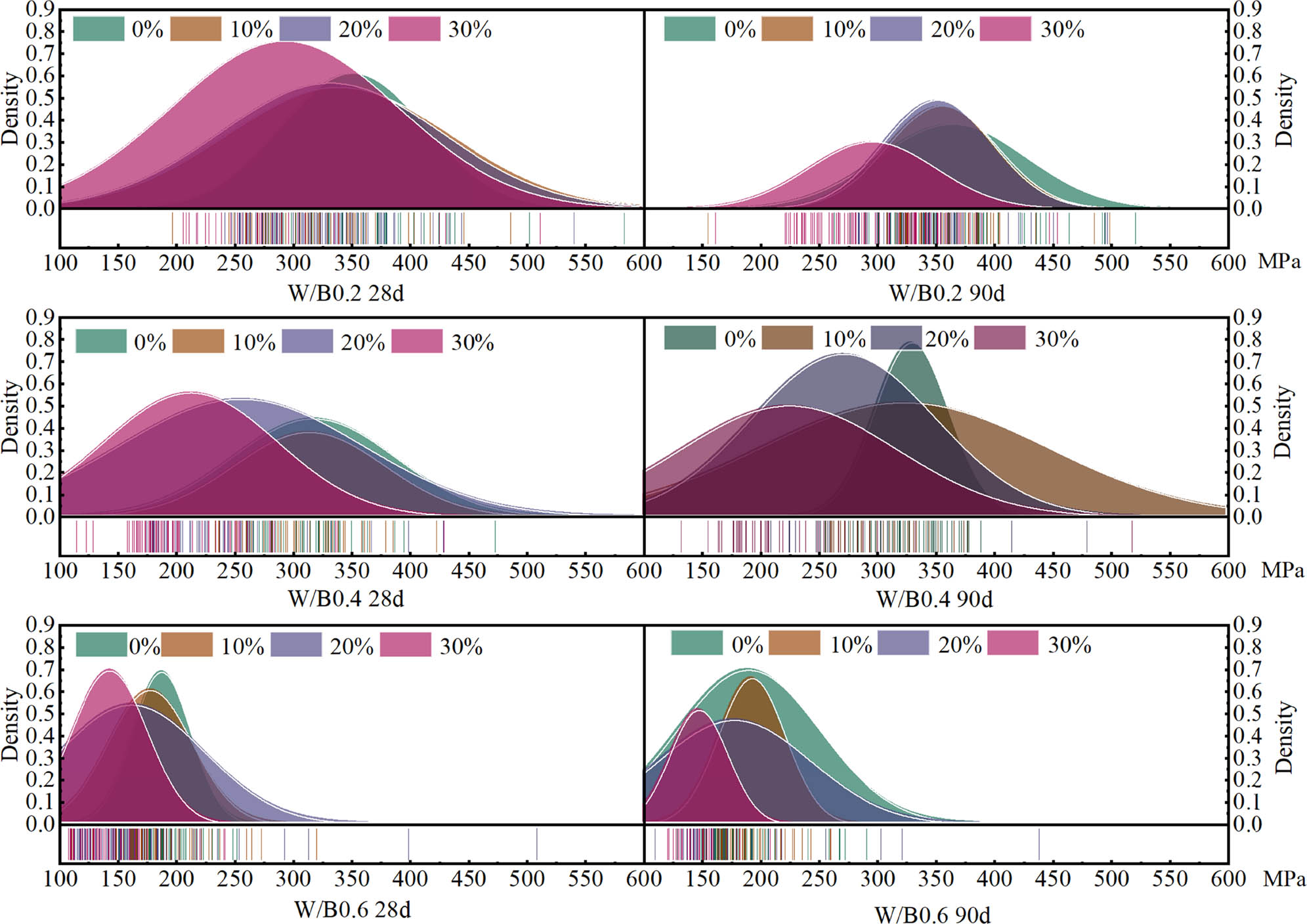

During the microhardness testing, each specimen undergoes indentation in both the hardened cement paste and ITZ, following lattice requirements. The microhardness values of the hardened cement paste and ITZ are distinguished through microscopic analysis, leading to separate data processing and analysis. This approach facilitates the determination of microhardness values for the hardened cement paste and ITZ in concrete specimens with different water–binder ratios and blending ratios of MSWI ash micro-powder. Figures 10 and 11 present the normal distribution diagrams of microhardness between the hardened cement paste region and ITZ under different proportions. These figures reveal that the peak in the low water–binder ratio is relatively gentle, and the hardness value is large. Simultaneously, the peak overlap area of different amounts of MSWI ash micro-powder at low water–binder ratio is extensive. The comparison shows that the microhardness value at 90 days is higher than that at 28 days, and the microhardness value of the hardened cement paste is greater than that of the ITZ.

ITZ microhardness value normal distribution diagram.

Hardened cement paste microhardness value normal distribution diagram.

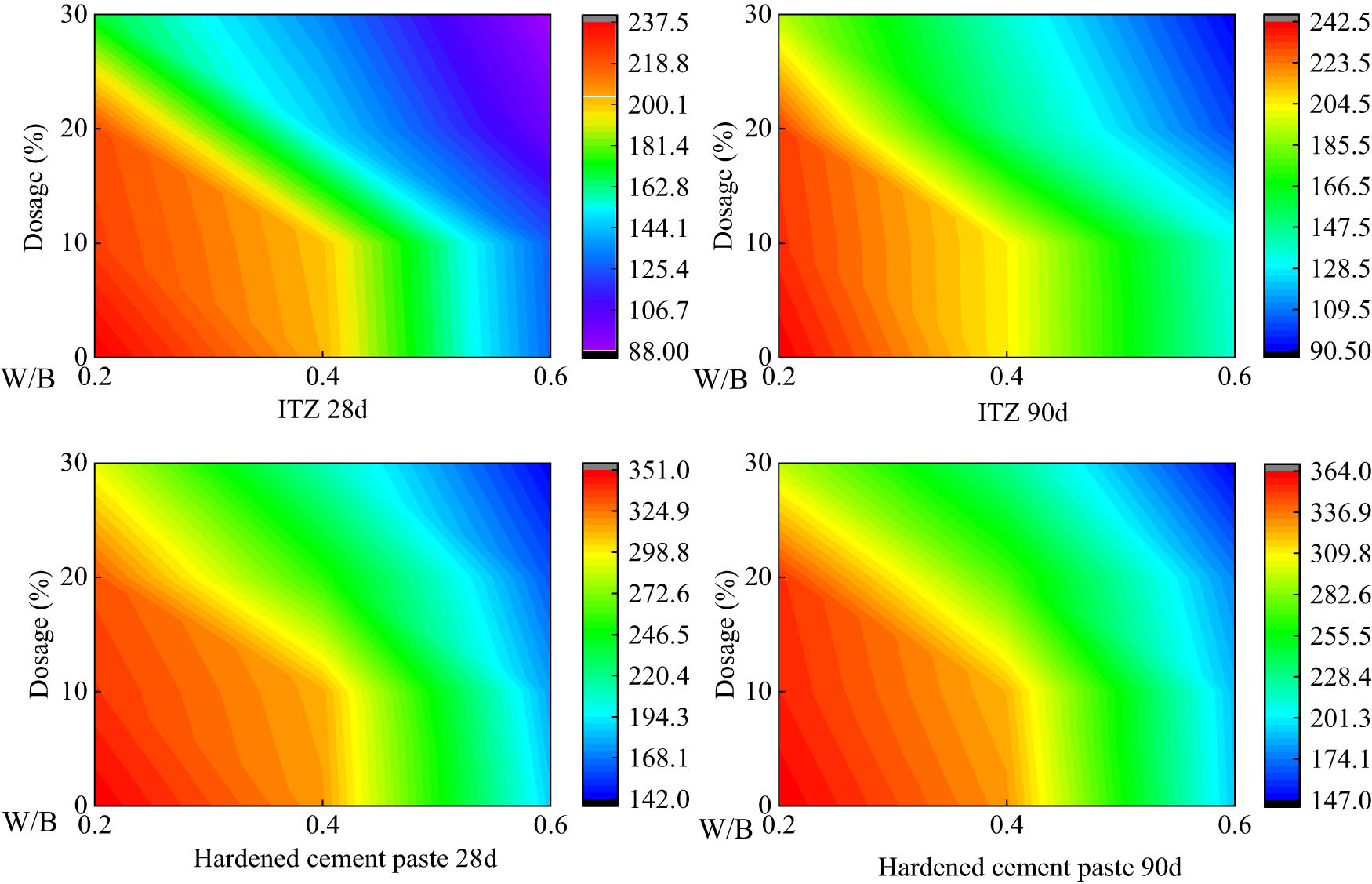

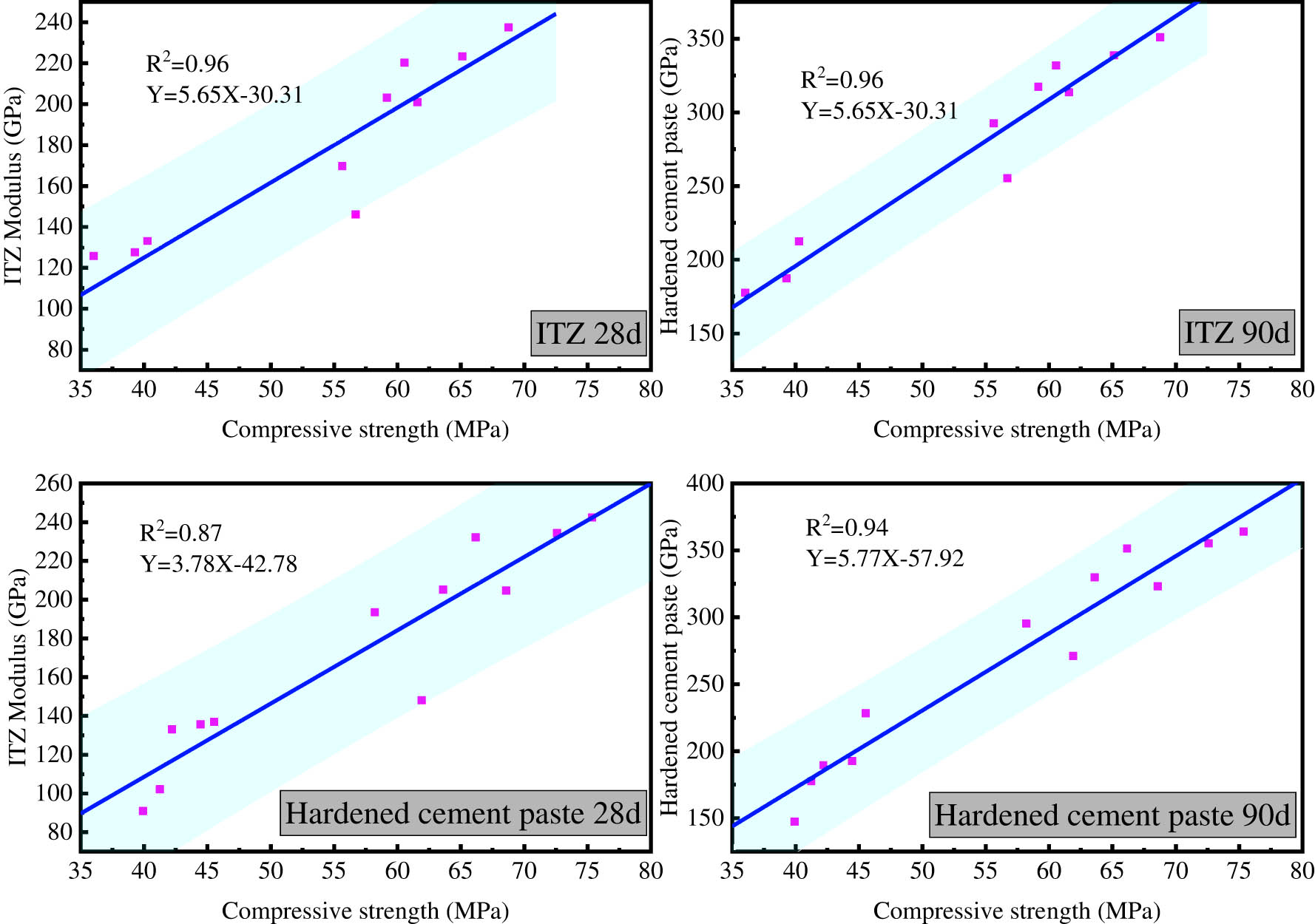

Analysis and calculation of the normal diagram allow obtaining the average microhardness values of the hardened cement paste and ITZ regions in the concrete specimens with different water–binder ratios and blending ratios of MSWI ash micro-powder. These average values are presented in Figure 12.

Average hardness distribution map/MPa.

From the comparison, the following observations can be made: As the water–binder ratio increases, the microhardness value of the hardened cement paste area decreases. For specimens with the same water–binder ratio, the microhardness value gradually decreases with an increase in MSWI ash micro-powder content. The microhardness values improve with an increase in curing age. The trend of microhardness values in the hardened cement paste area of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete follows a similar pattern as the mechanical property tests. The microhardness value of the ITZ is generally lower than that of the hardened cement paste. In the ITZ area, the microhardness values of both ordinary concrete and MSWI ash micro-powder concrete increase with a decrease in water–binder ratio. The microhardness of the ITZ for each water–binder ratio gradually decreases with an increase in MSWI ash micro-powder blending rate. A small amount (10%) of MSWI ash micro-powder in concrete has little effect on the microhardness of the ITZ, indicating good bonding between the aggregate and hardened cement paste. This effect is particularly evident in ordinary and medium-high strength concrete (water–binder ratio of 0.6 and 0.4). The microhardness value and compressive strength are linearly fitted, indicating a correlation between them. The fitting results are shown in Figure 13.

Fitting result.

These results demonstrate a good correlation between microhardness values and compressive strength, providing additional evidence that the microhardness method used in this test is feasible. This information serves as a valuable reference for future civil researchers to evaluate the performance of concrete.

3 LCA

3.1 Goal, functional unit, and system boundaries

In the LCA study, the goal is to compare the environmental impact of ordinary concrete and MSWI ash micro-powder concrete. The assessment aims to determine whether MSWI ash micro-powder concrete has a lower environmental impact than ordinary concrete. Specific data regarding the influence of various aspects in the production process of both types of concrete are obtained. The study focuses on preparing 1 L of each concrete type in the laboratory: ordinary concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.4 and MSWI ash micro-powder concrete with a water–binder ratio of 0.4 and 20% micro-powder content (refer to Table 3 for specific material amounts).

The system boundaries for concrete preparation include the production of various concrete mixing materials, transportation, and mixing in the laboratory. Additionally, the environmental impact of MSWI ash should be taken into account, considering that it is processed from municipal solid waste incineration.

3.2 Life cycle inventory analysis and data collection

The production list and data of raw materials in two types of concrete (except MSWI ash micro-powder) are determined according to the existing research and database. The production of MSWI ash micro-powder is shown in Table 5 Raw material transportation is shown in Table 6 and concrete mixing is shown in Table 7. SimaPro version 9.4.0 and Ecoinvent V3.8 were used in this study.

List of MSWI ash micro-powder

| Mode | Energy source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Size reduction | Screening | ||

| Oil consumption (L) | Distance (km) | Power consumption (MJ) | ||

| Petroleum | 0.00027 | 15 | / | / |

| Electrical | / | / | 0.378 | 0.333 |

Raw material transportation list

| Concrete type | Material | Fuel consumption (L) |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary concrete | Cement | 2.3875 |

| Sand | 3.36 | |

| Coarse aggregate | 1.71 | |

| MSWI ash micro-powder concrete | Cement | 1.91 |

| Sand | 3.36 | |

| Coarse aggregate | 1.71 | |

| MSWI ash micro-powder | 0.38 |

Concrete mixing list

| Concrete type | Power consumption | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary concrete | 6.11 | Degree |

| MSWI ash micro-powder concrete | 6.11 | Degree |

3.3 Life cycle impact assessment selection

In the life cycle impact assessment, the following impact assessment options have been selected to assess the environmental impacts of the analyzed products or processes:

Non-biodepletio (fossil fuels),

Global warming,

Ozone layer depletion,

Human toxicity,

Freshwater aquatic ecological toxins,

Marine aquatic ecotoxicity,

Terrestrial ecotoxicity,

Photochemical oxidation,

Acidification, and

Eutrophication.

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is also conducted to assess the impact of variables such as material transportation, concrete mixing, and laboratory environment on the data. This helps to understand the potential uncertainties and variations in the results.

3.5 LCA environmental analysis results

The LCA environmental analysis results you have presented in Table 8 indicate a positive environmental impact for MSWI ash micro-powder concrete compared to ordinary concrete. Here are some key points based on the information provided:

Environmental performance improvement: MSWI ash micro-powder concrete shows lower values in each impact category compared to ordinary concrete. This suggests that, across various environmental indicators, the environmental impact of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is generally lower.

Specific impact reductions: The results highlight specific reductions in environmental impact categories such as freshwater aquatic ecological toxins and global warming. For example, the freshwater aquatic ecological toxin impact of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is only 26% of that of ordinary concrete, and the global warming impact is 72% compared to ordinary concrete.

Positive impact of MSWI ash addition: The conclusion drawn is that the addition of MSWI ash powder contributes to reducing the environmental impact of concrete, particularly in terms of non-biological energy loss and CO2 emissions.

Quantitative comparison: The quantitative values provided (e.g., percentages) offer a clear comparison between MSWI ash micro-powder concrete and ordinary concrete, making it easy to understand the degree of improvement.

Holistic view: The use of multiple impact categories provides a more holistic view of the environmental performance, considering various aspects beyond just CO2 emissions.

Different concrete environmental impact category values

| Impact category | Unit | MSWI ash micro-powder concrete | Ordinary concrete | Specific value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-biodepletion (fossil fuels) | MJ | 1566.29 | 1868.21 | 0.84 |

| Global warming | kg CO2 eq | 325.07 | 449.06 | 0.72 |

| Ozone layer depletion | kg CFC-11 eq | 0.000011 | 0.000013 | 0.84 |

| Human toxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 55.75 | 81.04 | 0.69 |

| Freshwater aquatic ecological toxins | kg 1,4-DB eq | 60.75 | 232.28 | 0.27 |

| Marine aquatic ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 105072.01 | 200774.30 | 0.53 |

| Terrestrial ecotoxicity | kg 1,4-DB eq | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.67 |

| Photochemical oxidation | kg C2H4 eq | 0.029 | 0.046 | 0.64 |

| Acidify | kg SO2 eq | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.83 |

| Eutrophication | kg PO4 − eq | 0.25 | 0.508 | 0.49 |

In summary, the LCA results suggest that incorporating MSWI ash micro-powder into concrete has positive environmental implications, supporting the goal of creating more environmentally friendly construction materials. This information can be valuable for decision-makers in the construction industry, policymakers, and other stakeholders concerned with sustainable practices.

4 Conclusion

The conclusions drawn from the comprehensive study on the incorporation of MSWI ash micro-powder into concrete are insightful and provide a valuable overview of the material’s mechanical and environmental characteristics. Here’s a summary of the key points:

Mechanical properties: The macroscopic mechanical properties of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete follow a similar trend to ordinary concrete. The increase in the water–binder ratio leads to a decrease in compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and elastic modulus, a common behavior in concrete materials. Higher proportions of MSWI ash micro-powder result in a slower hydration reaction, leading to reduced mechanical properties, especially compressive strength. Specimens with a water–binder ratio of 0.4 and 10% MSWI ash micro-powder content exceed the mechanical properties of ordinary concrete, with a notable compressive strength value of 61.58 MPa at 28 days.

Microhardness: The microhardness value of cement paste in MSWI ash micro-powder concrete is lower than that of ordinary concrete. An increased proportion of MSWI ash micro-powder corresponds to a decrease in microhardness in the ITZ. This is consistent with the performance of mechanical properties.

LCA: LCA results demonstrate the positive environmental impact of incorporating MSWI ash micro-powder into concrete production. Significant reductions in non-biological energy loss and CO2 emissions are observed. Specific reductions in environmental impact categories, such as freshwater aquatic ecological toxins and global warming, highlight the environmental benefits of MSWI ash micro-powder concrete.

Sustainability implications: The findings suggest that MSWI ash micro-powder has the potential to be a green recycled building material, contributing to the reuse of solid waste resources. Despite a slight impact on mechanical properties, the positive environmental aspects make MSWI ash micro-powder a promising option for sustainable construction.

In summary, the study underscores the potential of MSWI ash micro-powder as a viable and environmentally friendly admixture in concrete production. The dual focus on mechanical performance and environmental impact provides a well-rounded understanding of its feasibility and benefits in the context of sustainable construction practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Key Laboratory of Civil Engineering Structure and Mechanics, Inner Mongolia University of Technology.

-

Funding information: This research topic has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China 51868058 and 52068058, Ordos Science and Technology Plan Project No. 2022YY006.

-

Author contributions: Shi Dongsheng: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and funding acquisition. Li Hanghang: resources, conceptualization, formal analysis, software, data curation, and writing – original draft. Lihao: resources and conceptualization. Ren Dongdong: software and data curation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Gao, Y., B. Wang, and C. Liu. Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fiber reinforced concrete. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 1, 2022, pp. 417–429.10.1515/rams-2022-0041Search in Google Scholar

[2] Lin, Y. Study on the performance of concrete with high content of slag admixture, Hebei University of Technology, Tianjin, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gao, S. and M. Yu. The historical background, significance and reform path of China’s “double carbon” goal. New Economy Leader, Vol. 2, 2021, id. 5.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Li, L., J. Lu, P. Shen, K. Sun, L. E. L. Pua, J. Xiao, et al. Roles of recycled fine aggregate and carbonated recycled fine aggregate in alkali-activated slag and glass powder mortar. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 364, 2023, pp. 132–147.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129876Search in Google Scholar

[5] Dang, J., J. Xiao, and Z. Duan. Effect of pore structure and morphological characteristics of recycled fine aggregates from clay bricks on mechanical properties of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 358, 2022, pp. 1–12.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129455Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhao, H. and C.-S. Poon. Recycle of large amount cathode ray tube funnel glass sand to mortar with supplementary cementitious materials. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 308, 2021, pp. 1–6.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124953Search in Google Scholar

[7] National Bureau of Statistics of China.2022. National statistics for 2021. 2022-01-20.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Byoung, H. C., H. N. Boo, A. Jinwoo, and Y. Heejung. Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes as construction materials—a review. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 3143, 2020, id. 3143.10.3390/ma13143143Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Xiao, R., B. Huang, H. Zhou, Y. Ma, and X. Jiang. A state-of-the-art review of crushed urban waste glass used in OPC and AAMs (geopolymer): Progress and challenges. Cleaner Materials, Vol. 4, 2022, pp. 65–74.10.1016/j.clema.2022.100083Search in Google Scholar

[10] He, J., R. Xiao, Q. Nie, J. Zhong, and B. Huang. High-volume coal gasification fly ash-cement systems: Experimental and thermodynamic investigation. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 377, 2023, pp. 1–17.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131082Search in Google Scholar

[11] Elhag, A. B., A. Raza, Q. U. Z. Khan, M. Abid, B. Masood, M. Arshad, et al. A critical review on mechanical, durability, and microstructural properties of industrial by-product-based geopolymer composites. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2023, pp. 1–13.10.1515/rams-2022-0306Search in Google Scholar

[12] Tang, Y., Y. Wang, D. Wu, M. Chen, L. Pang, J. Sun, et al. Exploring temperature-resilient recycled aggregate concrete with waste rubber: An experimental and multi-objective optimization analysis. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 62, No. 1, 2023, pp. 1–16.10.1515/rams-2023-0347Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zhang, P., S. Wei, G. Cui, Y. Zhu, and J. Wang. Properties of fresh and hardened self-compacting concrete incorporating rice husk ash: A review. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 61, No. 1, 2022, pp. 563–575.10.1515/rams-2022-0050Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zhang, L. Evaluation and utilization of the incinerator residue of municipal waste. The World of Building Materials, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2009, pp. 136–139.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang, H., P. He, L. Shao, and F. Lyu. Recycled aggregate utilization of municipal solid waste incineration ash residue. The First National Academic Conference on Research and Application of Recycled Concrete, 2008, pp. 151–156.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Li, J. Municipal solid waste incineration ash-incorporated concrete: One step towards environmental justice. Buildings, Vol. 11, 2021, pp. 495–495.10.3390/buildings11110495Search in Google Scholar

[17] Clavier, K. A., J. M. Paris, C. C. Ferraro, E. T. Bueno, C. M. Tibbetts, and T. G. Townsend. Washed waste incineration bottom ash as a raw ingredient in cement production: Implications for lab-scale clinker behavior. Resources Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2021, pp. 13–24.10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105513Search in Google Scholar

[18] Yang, Y., Q. Wu, and Q. Wu. Composition characteristics and resource utilization of municipal solid waste incineration ash. China International High-level Forum on Energy Saving and Emission Reduction of New Wall Materials in 2008 and China Building Materials Industry Scrap International Conference, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Gao, L. and S. Xiao. The study of the municipal solid waste incineration ash applied to deep mixing. Technology & Economy in Areas of Communications, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2012, pp. 1–3.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Taylor, H. F. W. Cement Chemistry, Thomas Telford Publishing, Thomas Telford Services Ltd, Chester UK, 1997.Search in Google Scholar

[21] An, J., J. Kim, and B. H. Nam. Investigation on impacts of municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash on cement hydration. ACI Materials Journal, Vol. 114, No. 5, 2017, pp. 701–711.10.14359/51689712Search in Google Scholar

[22] Kim, J., B. H. Nam, and B. Muhit. Effect of chemical treatment of MSWI bottom ash for its use in concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research, Vol. 67, No. 3–4, 2015, pp. 179–186.10.1680/macr.14.00170Search in Google Scholar

[23] Weng, R. Experimental study on autoclaved aerated concrete using MSW incinerator fly ash. New Building Materials, Vol. 4, 2013, pp. 37–42.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Shi, D., S. Liu, and J. Song. Experiment of mix design and mechanical properties about concrete using MSW bottom slag as fine aggregate. Concrete, Vol. 3, 2021, pp. 145–148 + 152.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Dong, Y., H. Lu, and D. Wu. Experimental study on mechanical behavior of regenerated ECC containing MSWI powder. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology-Transactions of Civil Engineering, Vol. 7, 2023, pp. 243–252.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Liu, J., Z. Li, and W. Zhang. The impact of cold-bonded artificial lightweight aggregates produced by municipal solid waste incineration bottom ash (MSWIBA) replace natural aggregates on the mechanical, microscopic and environmental properties, durability of sustainable concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 2022, 2022, id. 130479.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130479Search in Google Scholar

[27] Goulouti, K., P. Padey, and A. Galimshina. Uncertainty of building elements’ service lives in building LCA & LCC: What matters. Building and Environment, Vol. 2020, 2020, id. 106904.10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106904Search in Google Scholar

[28] GB5085.3-2019. Hazardous Waste Identification Standard. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China.Search in Google Scholar

[29] GB/T 17671-202. Cement mortar strength test method (ISO Method) standard. National standard of the People’s Republic of China.Search in Google Scholar

[30] JGJ 55-2011. Ordinary concrete mix ratio design specification. National standard of the People’s Republic of China.Search in Google Scholar

[31] GB/T 50081-2019. Standard for test methods for mechanical properties of concrete. National standard of the People’s Republic of China.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Shi, D., X. Xue, and K. Li. Experiment of mix proportion and mechanical performance about reactive powder concrete using granulated blast furnace slag as fine aggregate. Concrete, Vol. 9, 2019, pp. 135–138.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Shi, D. and Y. Huang. The study on mechanical of simulating component pro perties of concrete project with MSWI as fine aggregate. Inner Mongolia University of Technology, Vol. 7, No. 8, 2021, pp. 16–18.Search in Google Scholar

[34] GB50010-2010. Code for design of concrete structures. National standard of the People’s Republic of China.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Yu, B., B. Tao, and Y. Liu. Probabilistic prediction model of elastic modulus based on compressive strength of concrete. Concrete, Vol. 10, 2017, pp. 7–11.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete