Abstract

The development of auxetic materials, known for their unique negative Poisson’s ratio, is transforming various industries by introducing new mechanical properties and functionalities. These materials offer groundbreaking applications and improved performance in engineering and other areas. Initially found in natural materials, auxetic behaviors have been developed in synthetic materials. Auxetic materials boast improved mechanical properties, including synclastic behavior, variable permeability, indentation resistance, enhanced fracture toughness, superior energy absorption, and fatigue properties. This article provides a thorough review of auxetic materials, including classification and applications. It emphasizes the importance of cellular structure topology in enhancing mechanical performance and explores various auxetic configurations, including re-entrant honeycombs, chiral models, and rotating polygonal units in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional forms. The unique deformation mechanisms of these materials enable innovative applications in energy absorption, medicine, protective gear, textiles, sensors, actuating devices, and more. It also addresses challenges in research, such as practical implementation and durability assessment of auxetic structures, while showcasing their considerable promise for significant advancements in different engineering disciplines.

1 Introduction

The mechanical performance of cellular structures is influenced by material, load direction, and cell topology, leading to numerous efforts to modify or create new structures. Conventional cellular structures typically contract when stretched and expand when compressed, but there is growing interest in exploring unconventional behaviors. Poisson’s ratio is engineering materials’ negative lateral strain-to-axial strain ratio, which for most materials typically ranges from 0 to approximately 0.5 [1]. Changing the topologies of cellular structures can lead to different deformation patterns and mechanical performance. Cellular structures with negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) exhibit anomalous deformation behavior. NPR structures contract or expand under compression and tension, respectively. The difference between conventional and NPR honeycombs under axial stretching is shown in Figure 1.

![Figure 1

Schematic diagrams of (a) conventional (hexagonal) and (b) NPR (re-entrant) honeycombs under axial stretching [2].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_001.jpg)

Schematic diagrams of (a) conventional (hexagonal) and (b) NPR (re-entrant) honeycombs under axial stretching [2].

The existence of NPR materials in nature can be traced back to as early as 1882 when Voigt [3] discovered the NPR in iron pyrite monocrystals. This observation was made during experiments on how mineral rods react when they are twisted and bent. Love’s [4] subsequent work in 1927 supported Voigt’s findings and determined a Poisson’s ratio value of approximately −1/7 for iron pyrite monocrystals. Initially considered abnormal [5], NPR behavior has been confirmed in materials such as cadmium [6], arsenic crystals [7,8], zeolites [9], graphene [10,11], titanium mononitride (TiN) [12], δ-phosphorene [13], and α-cristobalite [5,14]. Figure 2a shows the NPR behavior in α-cristobalite networks. Some materials exhibit NPR behavior during phase transitions triggered by temperature changes [16]. Certain biological materials, including salamander skin [17], cow teat skin [18], cat skin [19], tendons [20], and cancellous bone [21], have been found to display NPR properties. Micro-fibrillar structures are believed to be responsible for the NPR behavior observed in these biomaterials. NPR properties have been observed in microscopic biomaterials, including the cytoskeleton of red blood cells and the nuclei of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [15,22–24]. In narrow microchannels, the embryonic stem cell nucleus (T-ESC) compresses its cytoplasm (blue), while the viscoelastic cytoskeleton (orange) exhibits NPR features, as illustrated in Figure 2b. These properties are vital in biomaterial development and medical stents [25].

NPR materials have been recognized for over a century, yet it was in the last four decades that they garnered significant renewed interest. In 1982, Gibson and Ashby described materials like aluminum honeycomb with NPR based on their deformation [26]. The 1980s [27–29] marked a pivotal period when researchers began to purposely create NPR structures, a significant advancement demonstrating the feasibility of designing materials and structures to exhibit NPR properties. This revelation opened the door to the realization of the extensive potential applications of these materials. Consequently, a broad array of synthetic NPR materials has been developed across all major material categories [5,30–33]. In 1985, Almgren developed an NPR structure using a simple arrangement of hinges and springs [34], as shown in Figure 3a and b. In 1987, Lakes introduced NPR structures by transforming a conventional foam (Figure 3c) into an isotropic re-entrant foam (Figure 3d) with enhanced resilience [36]. In addition, Friis et al. [35] detailed this conversion process, marking a significant advancement in that regard. Their collective research not only detailed the transformation process but also demonstrated the superior resilience and toughness of the isotropic re-entrant foam, pioneering the practical creation of NPR foams. In 1989, Herakovich [37] showed NPR behavior in composite laminate. The term “auxetic” emerged in 1991, derived from the Greek word for “ability to increase” [2]. Since then, researchers worldwide have been exploring this fascinating area, identifying negative Poisson ratios in various structures and materials. With development, different topologies emerge, including star [38], double arrowhead [39], and chiral [40]. By 2000, Grima and Evans [41] achieved an auxetic structure by rotating rigid units. They have continued extensive research in this area [42–48]. Alderson and Evans [49] also made a significant contribution. Recently, Portone et al. [50] developed a synthetic auxetic polymer with a cavitand crosslinker, predicting and subsequently confirming its NPR experimentally. Several studies have investigated ways to improve the properties and performance of auxetics, including hybrid [51–53], hierarchical [54–56], and tuneable [57,58] structures has been proposed.

Auxetic cellular materials, with their inherent primary properties such as NPR, synclastic behavior [59–61], and varying permeability [33,62,63], differ significantly from conventional materials. They stem from the special deformation mechanism of auxetic structures, making performance more reliant on geometry than material composition. Unlike non-auxetics that form saddle shapes when bent, auxetics display synclastic curvature, naturally adopting dome-like forms without buckling [59,60]; this allows for complex designs in structures, vehicle components, and medical applications [64,65]. Furthermore, their porous microstructure adjusts pore sizes under tension, thereby enhancing filter performance. This dynamic adaptability in response to pressure or stretching offers controlled filtration and overcomes the clogging and pressure issues common in conventional systems, presenting new opportunities [33,63].

Other properties, improved by the deformation mechanism of auxetic structures, are present in conventional structures but are enhanced in auxetics. These properties, herein referred to as secondary properties, are indentation resistance, fracture toughness, shear and bulk properties, energy absorption, and fatigue property. Auxetic materials are well-suited for applications that require unique properties and lightweight materials. While they perform similarly to conventional materials in terms of mechanics, they are particularly beneficial where their secondary properties are less important and low density is preferred. However, for tasks demanding extreme mechanical strength or where weight and space are not limited, conventional materials might be a better choice.

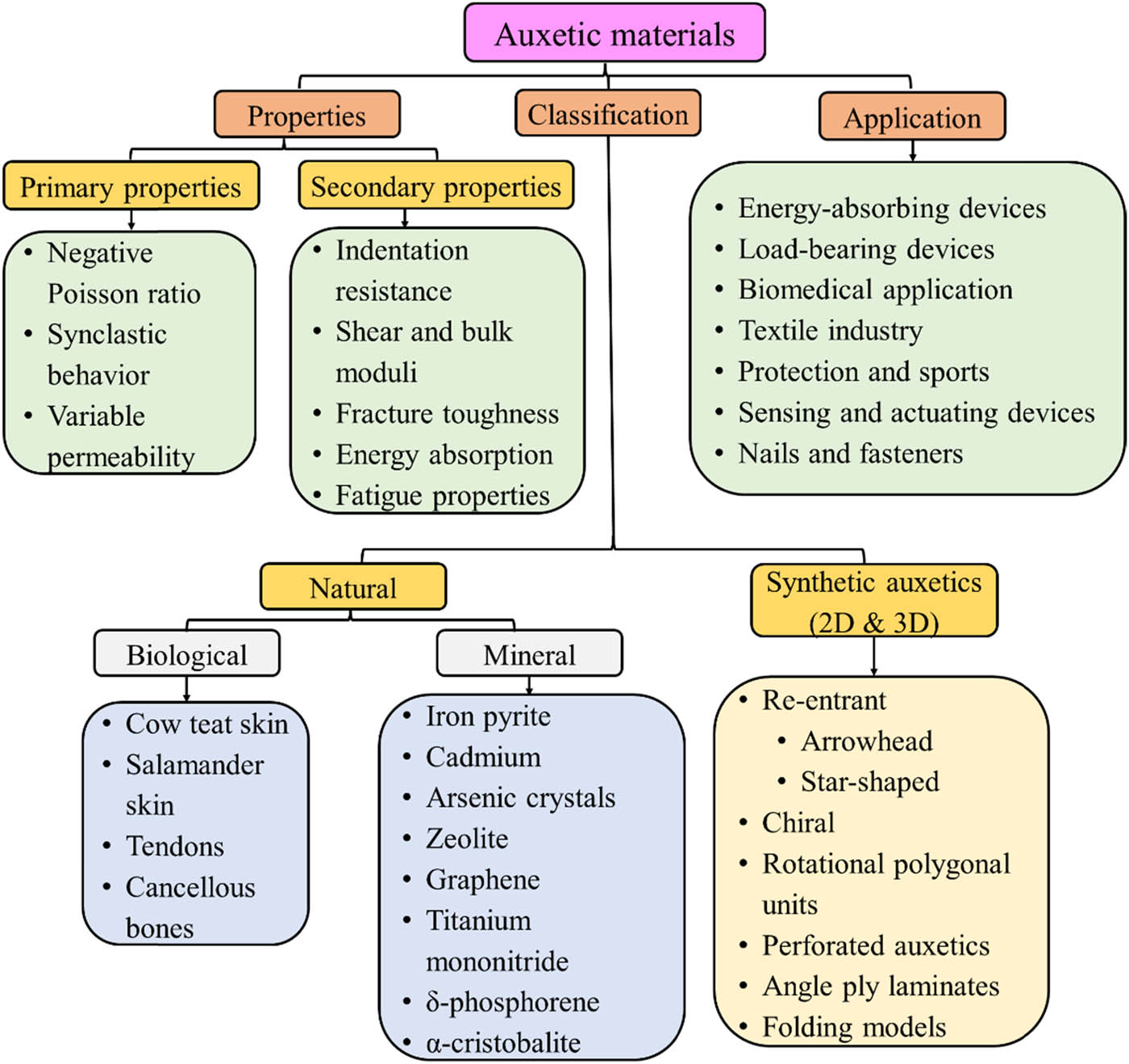

Auxetic structures also offer enhanced indentation resistance [66,67], large shear modulus [68,69], and high fracture toughness [70,71] compared to non-auxetic ones. They actively flow toward and deform in the direction of the indentation, becoming denser near the impact area. This is described by the hardness equation (equation (1)), where H is the hardness, E is the elastic modulus, and γ is 1 or 2/3 depending on the pressure type. Approaching a value of −1, hardness tends to infinity; approaching 0.5, it reaches a minimum [72]. Auxetic materials exhibit enhanced shear and bulk moduli, which can be calculated using classical elasticity theory for 3D isotropic solids [63]. This theory defined by Eqs. (2) and (3) involves Poisson’s ratio (ν) and the three interconnected moduli (elastic [E], shear [G], and bulk [K]). Despite having low stiffness and density, which restricts their use in load-bearing applications, auxetics significantly improve fracture toughness [73–75], especially as ν approaches −1, with toughness increasing substantially at higher volumetric compression ratios [76]. They also tend to have improved fatigue resistance [74,77] and good acoustic absorption [78,79]. These unique properties make auxetic structures suitable for applications in sandwich panels [80,81], medical stents [25,82–84], smart filters [62], sound absorbers [79], textiles [85–87], seat cushions [88], and human protection equipment [89,90]. In Figure 4, a summary of the properties, classification, and applications of auxetic materials is shown.

Summary of auxetic materials properties, classification, and application.

The growing interest in auxetic metamaterials and their applications has led to numerous reviews in recent years. However, most reviews focused on the classifications of auxetic geometric designs, mechanisms, and the mechanical properties of the most commonly studied 2D auxetic structures. This article extends the scope to both 2D and 3D auxetic structures. The main focus of this article is on synthetic auxetic structures, with a brief mention of naturally occurring auxetics for context. It aims to inform future developments through an analysis of current research. Consequentially, this article includes an overview of auxetic cellular structures, their classification, and uses, and also points out areas that need more research and suggests possible future directions.

2 Classification of auxetics

Over the years, researchers have proposed, studied, and tested various geometric structures and models that exhibit auxetic effects. These include re-entrant structures, chiral structures, rotating polygonal units, and angle-ply laminates. This section categorizes and explores various auxetic metamaterials, emphasizing the importance of their designed architecture in achieving unique mechanical properties.

2.1 Re-entrant structures

This well-known class of auxetic mechanisms showcases a distinctive pattern that quickly demonstrates the auxetic effect. Extensive research within this class has led to the creation and definition of various structures. The pioneering re-entrant honeycomb, by Gibson et al. [91] in 1982, was the first auxetic honeycomb with regular unit cells. Under axial tension, the re-entrant honeycomb demonstrates auxetic behavior by undergoing in-plane rotation of inclined cell wall bars at hinged joints, resulting in an auxetic phenomenon. Likewise, when subjected to compression, the structure displays an auxetic shrinkage. Figure 1a and b show a 2D hexagonal honeycomb and a 2D re-entrant honeycomb. The re-entrant auxetic honeycomb is extensively studied for its simplicity and high NPR [56,92–94]. Masters and Evans [95] examined the deformation behavior of both conventional and auxetic honeycombs and derived equations for their elastic moduli and Poisson ratios. Table 1 summarizes the mechanical properties of these honeycombs from cited references. Lee et al. [101] and Scarpa et al. [102] utilized finite-element analysis (FEA) to illustrate how the geometric parameters of re-entrant hexagonal honeycombs influence Poisson’s ratio and elastic modulus. However, existing analytical models have limitations in predicting nonlinear behavior during large deformations, and when applying these models to real cases or validation, they overlook specimen size and depth effects. However, an analytical solution by Wan et al. [103] and Mizzi et al. [104] addressed that respectively.

Derived equations for relative density (

| Auxetic structure | Mechanical properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

|

|

[26,96] |

|

|

[95] |

|

|

[95] | |

|

|

[95] | |

|

|

[96] | |

|

|

[96] | |

|

|

[95] | |

|

|

[97,98] |

|

|

[97] | |

|

|

[97] | |

|

|

[97] | |

|

|

[98] | |

|

|

[99] |

|

|

[100] | |

|

|

[100] | |

|

|

E

s is the elastic modulus of the parent material,

Re-entrant auxetic honeycombs, with their various configurations, including the double arrowhead [105–107] and star-shaped [99,100], are shown in Figure 5 and Table 1. The study by Darling Larsen et al. [39] introduced a new method in the field of compliant micro-mechanisms and structures with an NPR, featuring the innovative “double arrowhead structure.” This design element, a first of its kind, is pivotal in enabling NPR materials to exhibit their unique vertical contraction when subjected to horizontal compression. The methodology combines topology optimization with silicon micromachining for efficient design and fabrication. While the double arrowhead designs have potential applications, like in coronary stents and knitted fabrics, their mechanical characteristics remain less explored compared to the re-entrant honeycomb structure.

![Figure 5

Various configurations of re-entrant auxetic structure (a) classical re-entrant, (b) double arrowhead [108], (c) hexagonal re-entrant honeycomb [109], (d) structure formed from sinusoidal ligaments [110], (e) various auxetic star-shaped structures [111], and (f) three types of 2D periodic star-shaped re-entrant lattice configurations [112].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_005.jpg)

Various configurations of re-entrant auxetic structure (a) classical re-entrant, (b) double arrowhead [108], (c) hexagonal re-entrant honeycomb [109], (d) structure formed from sinusoidal ligaments [110], (e) various auxetic star-shaped structures [111], and (f) three types of 2D periodic star-shaped re-entrant lattice configurations [112].

Further exploring the mechanical properties, Qiao and Chen [97,107] investigated double arrowhead honeycombs collapse stress under various impacts, their in-plane mechanical behavior, and energy absorption. These studies highlight the potential of double arrowhead honeycombs in advanced applications, especially under high-velocity impacts, and emphasize the unique impact resistance and energy dissipation capabilities of functionally graded double arrowhead honeycombs. Additionally, Zhao et al. [98] focused on the directional crushing behavior, deformation modes, and dynamic strength of double arrowhead auxetic structures in different directions. Their findings stress the crucial role of impact direction in the deformation and energy absorption of these structures, suggesting that these properties can be tuned or optimized by considering the specific direction of expected loads in application environments. The double arrowhead honeycomb (Figure 5b) exhibits auxetic behavior through arrowhead opening and closing under uniaxial loading [39]. Figure 5d depicts an auxetic structure similar to the classical re-entrant honeycomb, with its auxetic behavior originating from inward and outward movements of sinusoidal ligaments [110].

Theocaris et al. [38] first showed that the shape of star-shaped micro-inclusions predominantly dictates the NPR in materials. Through numerical homogenization, their study highlights the microstructure’s role in determining the mechanical properties, crucial for advanced structural and aerospace applications. Building upon this, Grima et al. [111] investigated connected stars as auxetic systems, focusing on structures with stars of rotational symmetry order 3, 4, and 6 (Figure 5e). Systems with order 6 and 4 stars show greater auxetic potential than those with order 3. Their innovative use of the empirical modeling using dummy atoms technique underscores the critical interplay between geometric configuration, rotational symmetry, and auxetic properties. Recently, Ai and Gao [112] further advanced the field with an analytical model based on Castigliano’s theorem and Timoshenko beam theory, predicting the mechanical behavior of 2D star-shaped re-entrant lattice structures (Figure 5f). This model, corroborated by simulations, enables tailored material properties for diverse applications. Meng et al. [100] found that NPR of a star-shaped honeycomb enhances the elastic modulus and affects band gaps at lower frequencies. Wang et al. [99] went further to introduce a hybrid re-entrant star-shaped honeycomb, analyzing its impact responses. It identifies unique deformation modes, superior impact resistance, and the influences of impact velocity and cell wall thickness on performance. Table 1 provides a summary of the mechanical properties of these honeycombs based on the cited references.

Multiple studies have extended 2D re-entrant honeycombs into 3D re-entrant configurations [51,113–116]. Figure 6 depicts a 3D re-entrant structure, evolving from its 2D counterpart, the initial design adopted an open-celled foam cell [120]. Yang et al. [117] extensively studied these structures (Figure 6a), establishing a clear link between geometry and mechanical performance. They developed an analytical model, based on large deflection and Timoshenko beam theories, to predict crucial mechanical attributes like modulus, Poisson’s ratios, and yield strength in 3D re-entrant structures auxetic structures. However, their assumption of negligible axial shrinkage in re-entrant struts, while suitable for slender struts, falls short for stubbier configurations. Addressing this gap, Wang et al. [121] refined the model to incorporate considerations for strut stubbiness, overlap, and axial deformation, highlighting the pivotal role of strut slenderness and deformation dynamics in defining mechanical properties. Furthermore, Wang et al. [118] introduced an interlocking assembly method, revolutionizing the construction of complex 3D re-entrant structures using traditional manufacturing techniques, as shown in Figure 6b. Hengsbach and Lantada [119] focused on creating variants of 3D re-entrant auxetic structures using direct laser writing, illustrated in Figure 6c. It delved into the fabrication of complex, miniaturized auxetic geometries without support structures, representing a significant step in manufacturing auxetic materials. The 3D re-entrant auxetic structure was modified by Chen and Fu [122] by adding some struts, resulting in better stiffness compared to the typical re-entrant design.

Furthermore, 3D arrowhead [123–129] and star-shaped [130,131] auxetic structures have also been studied. Lim [127] introduced a 3D auxetic linkage model, an extension of the double arrowhead design, and uncovered a correlation between the structure’s geometry and its Poisson ratio. Dudek et al. [126] examined a 3D metamaterial made up of arrowhead-like units, demonstrating that this model exhibits auxetic characteristics regardless of the direction of loading and exhibits negative linear compressibility under specific loading directions. Gao et al. [128] introduced a novel theoretical model (Figure 7a) to predict the mechanical properties of a 3D double-V structure, considering boundary effects. It validates the model through FEA and experiments, revealing that adjacent cell constraints significantly enhance elastic modulus without affecting the NPR. Guo et al. [123] investigated three types of 3D double arrowhead plate-lattice (DAPL) auxetic structures, focusing on their mechanical properties under quasi-static and dynamic loading. One of the specimens is shown in Figure 7b. Utilizing 3D printing with thermoplastic polyurethanes, the study conducts both experimental and numerical analysis to explore the stiffness, energy absorption, and auxetic behavior of these structures. The findings highlighted the enhanced mechanical performance of DAPL structures compared to traditional truss-lattices, offering potential applications in lightweight engineering and energy absorption. Recently, Orhan and Erden [129] conducted a numerical study on the mechanical properties of 2D and 3D re-entrant, arrowhead, elliptic holes, and lozenge grids, as shown in Figure 7c. Li et al. [130] introduced a 3D star-shaped NPR structure, using simulations and experiments, emphasizing its energy absorption capabilities and suitability for lightweight protective structures in shipbuilding. Research combining 3D printing, simulations, and compression tests reveals the impact of design, material, and size on mechanical stability and energy absorption (Figure 8a) [131]. Notably, Xue et al. [132] study revealed that star-rhombic auxetic structures (Figure 8b) exhibit superior properties like higher elastic modulus and compressive strength, promising for protective devices and energy dissipation applications. These insights pave the way for tailored material use in sectors requiring specific mechanical characteristics, marking significant progress in the field of material science. Despite the mechanical advantages of auxetic structures, their long-term durability, real-world performance, scalability, and economic integration into manufacturing are underexplored, hindering widespread industry adoption.

2.2 Chiral structures

Chiral structures, formed by connecting straight ribs to core cylinders and arranged with rotating nodes, constitute a unique type of auxetic structure design. This special arrangement allows the ribs to wrap and unwrap around the cylinders under external forces, leading to the fascinating auxetic behavior that has captured the attention of researchers [133–138]. In 1991, Lakes initially proposed chiral configurations as potential auxetic structures [109]. Later, Prall and Lakes [40] found that the hexa-chiral structure’s Poisson’s ratio value was approximately −1 under in-plane deformations, maintaining a strong auxetic effect across a wide strain range and mechanical isotropy. Chiral honeycombs fall into two categories: chiral and anti-chiral. In chiral topology, adjacent cylinders are placed on opposite sides by interconnecting ribs (Table 2), while anti-chiral topology positions adjacent cylinders on the same side of the ribs (Table 2). Chiral configurations involve nodes rotating in the same direction, whereas anti-chiral configurations have nodes rotating clockwise or anticlockwise. Each topology features distinct connecting systems based on the coordination or number of ligaments attached to each cylinder. These systems are tri-chiral, tetra-chiral, and hexa-chiral structures for 3-, 4-, and 6-coordinated ligaments, respectively [141]. Alderson et al. [142] found that the deformation mechanism for chiral honeycombs with 3-, 4-, and 6-coordinated ribs involves flexing the ribs due to the rotation of cylinders under applied loads.

Derived equations for in-plane Poisson’s ratio (ν), elastic modulus (E), and shear modulus (G) in different rotating polygonal units

| Chiral structures | Mechanical properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

|

|

[139] |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[139] | |

|

|

[140] |

|

|

[140] | |

|

|

[140] | |

|

|

[140] | |

|

|

[66] |

|

|

[66] | |

|

|

[66] |

Note: K h is the stiffness constant and A represents the unit cell’s area.

Prall and Lakes [40] used beam theory to predict the in-plane Poisson’s ratio, which is valid for slender beams with a relative density below 0.29 [26,40]. The predicted Poisson’s ratio, always with a value of −1, results in a structure with an infinite shear modulus. Spadoni and Ruzzene [140] used a micro-polar-continuum model to describe the behavior of the chiral lattice (Table 2), aimed at addressing the indeterminacy in its constitutive law resulting from the NPR. Their findings revealed that while this indeterminacy is resolved, the shear modulus becomes an independent parameter. Notably, for specific configurations, the shear modulus equals that of the triangular lattice, despite the chiral lattice being more compliant due to the bending deformation of its internal members. Liu et al. [143] developed a continuum theory adding a chiral parameter to model 2D chiral solids’ behavior, analyzing triangular chiral lattices to deduce material constants. Bacigalupo and Gambarotta [144] employed two homogenization methods, micro-polar and second gradient, for hexa-chiral and tetra-chiral honeycombs, capturing micro-structural effects on macroscopic properties. While Liu et al. [143] focused on theoretical advancements in continuum models for chiral materials, Bacigalupo and Gambarotta [144] combined theoretical modeling with experimental validation, offering a comprehensive approach to understanding and predicting the complex behaviors of chiral cellular solids, emphasizing the interplay between microstructure and overall material performance.

Mousanezhad et al. [139] employed an energy-based approach, utilizing Castigliano’s second theorem, to derive the elastic moduli of tri-chiral, anti-tri-chiral, tetra-chiral, anti-tetra-chiral, and hierarchical honeycombs (Table 2). Their method combined theoretical derivation, validation through FEA, and comparison with existing data. The study revealed how chirality and hierarchy influence elasticity in 2D honeycombs, notably affecting stiffness, Poisson’s ratio, and shear properties, depending on the honeycomb’s base shape. These insights are crucial for the design of materials with tailored mechanical characteristics. Furthermore, Smith et al. [66] introduced a novel model, the chiral missing rib foam model, to explain the auxetic behavior observed in certain foams. This model suggested that the auxetic properties arise from removing select cell ribs, rather than altering internal cell angles. It proved effective in predicting the strain-dependent behavior of materials like honeycomb and foam, aligning closely with experimental data. The research provided insights into a new approach for manufacturing auxetic foams directly, offering potential advancements in materials science. The study by Tang et al. [145] examined the deformation of chiral missing rib and mixed structures, focusing on how the structure’s size and beam angles influence auxetic behavior. Utilizing both experimental and numerical methods on 3D-printed samples, the research highlighted the importance of beam-wall contacts in auxetic materials. The findings confirmed model reliability, and advanced understanding of auxetic structures, offering insights for diverse applications.

Multiple design methods suggested for transforming 2D chiral honeycombs into 3D chiral configurations have been proposed, as shown in Figure 9 [146–156]. Fu et al. [146] designed a novel chiral 3D structure, as shown in Figure 9a. This design is achieved by orthogonally assembling a 2D chiral honeycomb with four ligaments. Their findings, consistent with finite-element method calculations, indicate that the structure’s material is macroscopically isotropic and has a Poisson’s ratio near −1, indicating a higher ratio of shear modulus to elastic modulus. Moreover, Fu et al. [149] introduced a novel design for 3D auxetic materials using chiral structures with circular and square loops and inclined rods (Figure 9d). It explores two cell types developed from tetra-chiral honeycombs, emphasizing the material’s deformation is largely influenced by ligament and rod design, allowing flexibility in loop shapes. The research also discussed the effects of layer spacing and conditions for achieving isotropy in these materials. Farrugia et al. [154], Wu et al. [150], Xia et al. [152], and Huang et al. [157] have innovatively extended the design principles of auxetic materials into 3D by replacing the 2D auxetic cylinders with cubes. This evolution into 3D chiral mechanical metamaterials marks a significant step forward. These advanced structures are not just theoretical achievements, and they hold considerable promise for practical applications across a broad spectrum. From enhancing airfoil systems and developing smart structure technologies to creating more efficient auxetic stents for medical purposes and improving electronic components, the potential uses are as diverse as they are impactful [155].

![Figure 9

(a) 3D tetra-chiral auxetic structure [146], (b) 3D auxetic structure based on an anti-tetra-chiral design [147], (c) 3D helical hexa-chiral structure [148], (d) 3D tetra-chiral auxetic structures with square and circular loops [149], (e) chiral-chiral-anti-chiral metamaterials and chiral- anti-chiral-anti-chiral metamaterials [150], (f) 3D anti-chiral structure [151], (g) 3D isotropic anti-tetra-chiral structure with cubic nodes [152,153].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_009.jpg)

(a) 3D tetra-chiral auxetic structure [146], (b) 3D auxetic structure based on an anti-tetra-chiral design [147], (c) 3D helical hexa-chiral structure [148], (d) 3D tetra-chiral auxetic structures with square and circular loops [149], (e) chiral-chiral-anti-chiral metamaterials and chiral- anti-chiral-anti-chiral metamaterials [150], (f) 3D anti-chiral structure [151], (g) 3D isotropic anti-tetra-chiral structure with cubic nodes [152,153].

2.3 Rotating polygonal structures

Auxetic structures were created using a rotation mechanism, demonstrated with interconnected shapes at vertices. Under the influence of load, these structures undergo rotation, resulting in either expansion or contraction, thereby producing auxetic effects. Extensive research was conducted by Grima and co-workers [41–48] to investigate the mechanical properties of structures made up of rotating polygons. Grima and Evans [41] first introduced a novel mechanism for achieving NPR using rigid squares and triangles connected by hinges (Figure 10a and b). In idealized scenarios with perfectly rigid components, they found that Poisson’s ratio value equals −1 and exhibits isotropic behavior. This structure, which can be seen as a two-dimensional arrangement of squares or a projection of a three-dimensional crystalline structure, demonstrates how altering the angles between the squares influences their auxetic behavior. Their study also provided a thorough mathematical analysis of this configuration, contributing to the understanding of how geometry and deformation mechanisms can produce auxetic materials. Other models incorporate rotating rectangles [43,47,48], triangles [42], rhombi [158], and parallelograms [44,159]. It is worth noting that these idealized rigid models overestimate the auxetic properties, but real materials show less pronounced auxeticity [160]. Consequently, semi-rigid models with Poisson’s ratios dependent on square rigidity and loading direction, and stretching connected plates, were introduced to better approximate real-world behavior [160,161].

![Figure 10

Deformation mechanism of (a) rotating squares [41], (b) rotating triangles [42], (c) rotating rectangles type I, (d) rotating rectangle type II [43], (e) rotating rhombi of Type α [44], (f) rotating rhombi of Type β [44], (g) rotating parallelograms of Type I-α [44], (h) rotating parallelograms of Type I-β [44], (i) rotating parallelograms of Type II-α [44], and (j) rotating parallelograms of Type II-β [44].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_010.jpg)

Deformation mechanism of (a) rotating squares [41], (b) rotating triangles [42], (c) rotating rectangles type I, (d) rotating rectangle type II [43], (e) rotating rhombi of Type α [44], (f) rotating rhombi of Type β [44], (g) rotating parallelograms of Type I-α [44], (h) rotating parallelograms of Type I-β [44], (i) rotating parallelograms of Type II-α [44], and (j) rotating parallelograms of Type II-β [44].

Recently, Sorrentino et al. [162] investigated bio-inspired titanium metamaterials with NPRs based on rotating squares. They optimized these structures through FEA, proposing a combined auxetic rotating/chiral design with enhanced mechanical properties and a Poisson’s ratio value of −0.94. Experimental validation on a 3D-printed prototype confirmed their potential for tailored mechanical properties and improved elastic strain capabilities. Grima et al. [43] showed that auxetic behavior can result from rotating rigid rectangles, offering advantages over square-based models. Rectangles allow for both positive and more NPRs, dependent on geometry, strains, and relative rigidity, providing insights into versatile auxetic behavior generation. Rotating rectangles offer alternative connectivity arrangements, with Type I configurations (Figure 10c) exhibiting anisotropic mechanical behavior and Type II configurations (Figure 10d) displaying isotropy with a constant Poisson’s ratio value of −1. Despite using the same rigid rectangle building block and rotation mechanism, the connectivity arrangement results in significantly different mechanical properties (Table 3). Type I involves corner-sharing rectangles forming rhombi, while Type II features parallelogram connectivity, both having implications for the mechanical behavior of systems with these structures, as shown in Figure 10c and d.

Derived equations for in-plane Poisson’s ratio (ν), elastic modulus (

| Auxetic structure | Mechanical properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

|

|

[41] |

|

|

[41] | |

|

|

[41] | |

|

|

[47,48] |

|

|

[47] | |

|

|

[47] | |

|

|

[47] | |

|

|

[48] |

|

|

[48] | |

|

|

[48] | |

|

|

[42] |

|

|

[42] | |

|

|

[42] | |

|

|

[158] |

|

|

[158] | |

|

|

[158] | |

|

|

[158] | |

|

|

[158] |

|

|

[158] | |

|

|

[158] | |

|

|

[159] |

|

|

[159] | |

|

|

[159] | |

|

|

[159] | |

|

[159] | |

|

|

[159] | |

|

|

[159] | |

|

|

[159] | |

|

|

[44] |

|

|

[44] | |

|

|

[44] | |

|

|

||

|

|

[159] |

|

|

[159] |

Note: Original elastic moduli equations multiply denominators by plate thickness, for consistency, unit thickness is assumed.

K h is the stiffness constant and A represents the unit cell’s area.

Grima et al. [44] also studied the auxetic behavior of rhombi and parallelograms, as shown in Figure 10. Type α structures have smaller angles of rhombi or parallelograms attached to the larger angles of adjacent units, while in comparison, Type β structures have smaller angles attached. Analytical models were developed to understand the mechanical properties of these structures (Table 3). Rotating rhombi, whether Type α or Type β, introduce further complexity, with Type α exhibiting anisotropic behavior and Type β displaying isotropy with a constant Poisson’s ratio value of −1 [158]. Rotating parallelograms expand the possibilities with four configurations: Type I-α, Type II-α, Type I-β, and Type II-β [159]. Each configuration exhibits unique mechanical properties, with some showing a variation in Poisson’s ratio with nominal strain, while others maintain a constant NPR. However, the rigid rotating units limit plastic deformation, concentrating it on hinges, and reducing structural durability. Additionally, to address increased mass associated with low porosity, some scholars propose employing lightweight rotationally rigid structures as an alternative solution [162–164]. Rotating triangular plates, particularly equilateral triangles, provide an interesting case study [42]. In an ideal configuration featuring perfectly rigid plates and hinges, a constant NPR of −1 is observed. The modulus of elasticity tends toward infinity when fully contracted or expanded, while the shear modulus remains infinite for all configurations. However, irregular triangles exhibit behaviors closer to those seen in honeycomb auxetic systems, displaying anisotropic properties and Poisson’s ratios that fluctuate with nominal strain.

Innovative research has extended beyond 2D systems to develop rotating rigid units in three dimensions (Figure 11) [165,166,169–171]. A key development in this area is the “rotating tetrahedra,” inspired by auxetic crystalline structures like α-cristobalite [14]. Gaspar et al. [170] developed a 3D model built from a connected-nodes model rather than rotating rigid units, enhancing understanding and design implications by revealing geometric constraints on simultaneous auxetic behavior in multiple planes of the model. Attard and Grima [165] developed new three-dimensional models (Figure 11a) based on structures made of rigid cuboids that deform through relative rotation. Their research demonstrates that, under axial loading, these systems have the potential to exhibit negative values for all six on-axis Poisson’s ratios. Another innovation by Farrugia et al. [166] involved a mechanism (Figure 11b) similar to that in “push drill tools,” effectively converting rotational to linear motion, applied in connecting rotating squares from two to three dimensions. The research by Grima et al. [46] introduced a novel concept for transforming a 2D rotating squares’ mechanism into a 3D structure with unique negative properties. By stretching the base structure, they utilized a “triangular elongation mechanism” (TEM) to achieve negative out-of-plane Poisson’s ratios and negative linear compressibilities, which are independent of scale. The study also explored the possibility of using different base structures. The authors hope that their work will inspire experimentalists to design new materials and metamaterials based on their model, particularly highlighting the TEM concept and its synergistic relationship with the rotating rigid units’ mechanism as innovative contributions in the field of mechanical metamaterials.

Galea et al. [169] introduced a novel method for creating 3D auxetic metamaterials by strategically placing continuous voids with constant cross-sectional areas within a solid block (Figure 11e). This approach, exemplified using voids with diamond-shaped cross-sections, allows for the production of these materials through additive and subtractive manufacturing, as well as casting. The resulting structures, formed as connected polygons, demonstrate negative or zero Poisson’s ratios, maintaining this characteristic up to at least 7% strain. This design method holds promise for making three-dimensional auxetic metamaterials more accessible in the consumer market. Another approach is converting the structure’s plane into a three-dimensional shape, like a cylinder, effective for creating tubular auxetics [168]. An extensive review of the thermomechanical behavior of rotating rigid units is available in the work by Grima-Cornish et al. [167].

The study of rotating polygonal units presents an area of interesting mechanical behavior and potential applications. The studied literature showed the significance of understanding the relationship of geometry, rigidity, and connectivity to generate auxetic behavior. While idealized models provide insights, semi-rigid structures, and real-world considerations bring these materials closer to practical application. The versatility exhibited by rotating rectangles, triangles, and other quadrangular shapes lays the foundation for innovative solutions in engineering, materials science, and beyond.

2.4 Other auxetic structures

2.4.1 Perforated auxetic structures

Perforated structures are auxetic structures created by introducing cuts or voids [172–179] into a sheet. These cuts or voids induce NPR behavior when the sheet is stretched or compressed. Shan et al. [173] studied a 2D elastomeric sheet with elongated cuts arranged periodically (Figure 12a) and found that adjusting the cut geometry could modify the auxetic behavior. Those with threefold and sixfold symmetry displayed isotropic responses among the five cut patterns investigated. Grima et al. [174] proposed perforated auxetic structures with random cuts (Figure 12b) and discovered that these structures displayed NPR characteristics despite the randomness. Mizzi et al. [177] employed laser cutting to create twelve perforated auxetic geometries from a 1 mm rubber sheet, while Carta et al. [176] milled a Lexan polycarbonate sheet for a porous auxetic structure (Figure 12c).

![Figure 12

(a) A picture showing a specimen featuring a Kagome cut pattern with close-up images showcasing the central area of specimens exhibiting varying (θ) angles of the Kagome cut pattern and of the square cut pattern [173], (b) simulated and experimental stretching of auxetic metamaterial [174], and (c) (i) undeformed, (ii) tensile deformation and (iii) compressive deformation of auxetic perforated structure [176].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_012.jpg)

(a) A picture showing a specimen featuring a Kagome cut pattern with close-up images showcasing the central area of specimens exhibiting varying (θ) angles of the Kagome cut pattern and of the square cut pattern [173], (b) simulated and experimental stretching of auxetic metamaterial [174], and (c) (i) undeformed, (ii) tensile deformation and (iii) compressive deformation of auxetic perforated structure [176].

2.4.2 Angle-ply laminates

Angle-ply laminated composites, designed with auxetic properties, have been developed and manufactured [180–182]. Milton [183] proposed a design, depicted in Figure 13, which includes stiff inclusions and a compliant matrix. This approach, utilizing strategic layering of materials on different length scales, enables the creation of composites having a Poisson’s ratio of about −1, leading to near-isotropic elasticity in two and three dimensions. Fan and Wang [184] carried out a comprehensive study on the auxetic properties of a composite beam, focusing on its out-of-plane NPR characteristics. This unique characteristic was achieved by employing specially designed symmetric stacking sequences of layers guided by the principles of the classical laminate theory. Wang’s [185] study consistently demonstrated lower tensile damage in both fiber and matrix across all plies in auxetic laminates, showing up to a 40% average reduction compared to non-auxetic counterparts. While auxetic laminates may offer some benefits, more research is needed to explore whether auxetic laminates can effectively mitigate delamination and compressive matrix damage.

![Figure 13

(a) Auxetic composite laminate model and (b) rod-and-hinge structure of the laminate: (i) original and (ii) stretched [183].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_013.jpg)

(a) Auxetic composite laminate model and (b) rod-and-hinge structure of the laminate: (i) original and (ii) stretched [183].

2.4.3 Folding models

Origami means “folding paper” in Japanese. While not all “folding paper” was initially called Origami, its exact widespread adoption is unknown. With the advancement of computational power and parametric design tools, origami has started influencing engineering and structural theory. The mechanical behavior of origami-based metamaterials is mainly influenced by their unique fold and crease patterns [186–188]. The mechanical behavior of folded sheets can differ significantly from the original paper and may depend more on the origami’s geometry than the paper itself [189]. In auxetic structure studies, origami is frequently explored for its potential, even though it is not commonly discussed in traditional reviews. This research includes origami in the classification because it’s possible to design origami patterns exhibiting auxetic behavior [190–193]. The research by Schenk et al. [194] explored metallic cellular cores in sandwich structures for blast mitigation. The novel stacked folded core offers unique anisotropic properties and versatile design possibilities, showing promising blast mitigation effectiveness. Zhang et al. [195] also investigated the ballistic performance of rectangular sandwich panels with aluminum origami cores and the result shows comparable ballistic performance with honeycomb cores.

Architects, designers, and engineers have started exploring the technological potential of origami patterns, which exhibit NPR behaviors. The development of parametric design software has made it easier to study and define a wide range of origami structures mathematically. This software simplifies the design process and enables the creation of complex three-dimensional origami structures without requiring extensive calculations. OriMetric, developed by Mads Jeppe Hansen [196] (Figure 14), exemplified the application of folding auxetic surfaces. This rubber-based material incorporates an intelligent pattern that imparts various functional properties, including shock absorption, fracture resistance, expansion, collapse, and the ability to recover its original shape. OriMetric is available in different patterns, some with enhanced functionality, while others serve purely decorative purposes. Thin-film materials are no longer confined to paper in origami and kirigami structures, instead, they have diversified to include various materials such as metals, polymers, and graphene [197]. The utilization of origami and kirigami-inspired metamaterials has also extended to the development of various functional materials [198,199].

![Figure 14

Mads Jeppe Hansen’s folding auxetic surface [196].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_014.jpg)

Mads Jeppe Hansen’s folding auxetic surface [196].

3 Applications of auxetic structures

This geometric classification offers valuable insights into achieving and optimizing auxetic effects. Despite this understanding, a gap exists in applying these concepts practically. This section delves into the practical and potential application of auxetic structures.

3.1 Energy-absorbing devices

Auxetic structures dissipate energy through the bending of cell walls and the formation of plastic hinges. Their increased porosity leads to a reduction in weight, thereby enhancing their specific energy absorption capacity. Previous research has indicated that, when compared to traditional cellular structures of similar mass, auxetic structures demonstrate enhanced energy absorption capabilities [200–202]. Numerous experimental, numerical, and analytical approaches have investigated the potential applications of auxetic structures in energy absorption [202–204]. This includes their implementation in modern vehicles, where structures such as bumpers [205–207], crash boxes [90,208–210], and pillars are used to absorb energy during blast [80,211] and impact loading [205,212–214]. Wang et al.’s [207] innovative bumper design represents a significant advancement in vehicle safety technology (Figure 15a). By harnessing the unique properties of auxetic materials and employing smart optimization techniques, they have paved the way for safer and more efficient vehicles.

Auxetic cores have shown to be game changers for impact resistance. Researchers introduced a novel auxetic crash box design, enhancing energy absorption over traditional counterparts [208]. This innovative crash box boasts superior rigidity, increased energy absorption in medium-speed collisions, and improved capacity and efficiency, all while extending buffer time for occupant safety. This breakthrough promises a significant leap in automotive safety technology [216]. Wang et al. [210] designed an NPR bio-inspired crash box (Figure 15b), enhancing crashworthiness through innovative structure and advanced optimization algorithms. Moreover, a study by Lan et al. [215] examined how sandwich panels with three distinct core materials, namely, aluminum foam, traditional honeycomb, and auxetic honeycomb, perform when subjected to dynamic loading conditions. The researchers found that auxetic honeycomb panels outperformed the others in both energy absorption and resistance to dynamic loads. Figure 15c illustrates the deformation patterns and material flow of auxetic and conventional cores used in the panels. Imbalzano et al. [80] showed they densify under the impact, absorb energy, and protect the panel more effectively than conventional cores. Further research by Xiao et al. [217] confirmed this, observing unique contraction and expansion of the re-entrant auxetic core under impulsive loads, hinting at a more efficient energy dissipation mechanism. Auxetic structures have also shown promising applications in seismic loading like vibration isolation and damping [178,218–220]. Huang et al. [219] explored a seismic auxetic metamaterial for wave attenuation and identified its benefits in damping devices to mitigate seismic effects.

3.2 Load-bearing devices

Auxetic structures are used in load-bearing devices for their ability to safely support and distribute loads, preventing deformation or failure under various conditions. This is unlike energy absorption devices, which aim to minimize damage through energy dissipation. For instance, in cars, the chassis supports the vehicle’s weight (load-bearing), while crumple zones dissipate energy during collisions (energy absorption), illustrating the dual application of these principles. Conventional auxetics’ low stiffness restricts their use in applications needing both NPR and load-bearing capacity [221]. With this several investigations were put forward on how to improve the load-bearing of auxetic structures [222–226]. Gao et al. [225] developed innovative auxetic designs with high stiffness and controllable elasticity. They achieve this through intricate stretching mechanisms within the auxetic structure. This paves the way for auxetics that are not only strong but also adaptable, with properties tailored for specific applications. The study by Menon et al. [226] introduced innovative auxetic beam designs in structural engineering, achieving a 64% mass reduction and superior efficiency compared to traditional beams. Demonstrated in lightweight footbridges (Figure 16a), these designs highlight the potential of auxetic materials for sustainable and lightweight construction, surpassing conventional beams in performance. Ma [231] further explores this potential by proposing NPR auxetics as alternatives for various structural components, including bushings, mounts, and springs. The potential of auxetics goes beyond just strength. Researchers like Heo et al. [227,232] envision using chiral auxetic structures to create morphing airfoil wings (Figure 16b). These adaptable wings could significantly improve an aircraft’s aeroelastic performance. However, this area remains in its early stages, and manufacturing such composite structures is crucial for achieving optimal results.

![Figure 16

(a) Deflection of lightweight footbridge made of (i) aluminum sheet and (ii) auxetic structure [226]; (b) airfoil made of chiral auxetic structure [227]; (c) multilayer orthogonal auxetic structure showcased in 3D view, y–z and x–z cross-sections, and x-direction contraction under compression [228]; (d) mortar cube reinforced with octagonal lattice [229], and (e) cement mortar reinforced with re-entrant lattice [230].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_016.jpg)

(a) Deflection of lightweight footbridge made of (i) aluminum sheet and (ii) auxetic structure [226]; (b) airfoil made of chiral auxetic structure [227]; (c) multilayer orthogonal auxetic structure showcased in 3D view, y–z and x–z cross-sections, and x-direction contraction under compression [228]; (d) mortar cube reinforced with octagonal lattice [229], and (e) cement mortar reinforced with re-entrant lattice [230].

Auxetic structures can also be applied to cementitious structures, offering benefits such as lateral confinement and enhanced bonding with cement matrices [233]. Examples include reinforcement for concrete beams and columns [228,230,234,235] and enhancing the strength of porous cementitious structures [236]. They hold promise for concrete pavements, marine harbors, coastal protection dams, walls, and structural panels [229,237,238]. However, developing beams, columns, and slabs from auxetic materials is rare, as achieving the required strength and stiffness without compromising auxetic properties is a significant challenge, highlighting an area ripe for further research.

3.3 Bio-medical application

Auxetics significantly contributes to a wide range of medical applications [239]. The utilization of auxetic implants in various biomedical applications has gained recent attention [240,241]. Recent advancements have introduced auxetic patches [242–244], prostheses [200,245], and stents [25,82–84,246–248] as alternatives to traditional ones. These stents possess an NPR that closely matches the arterial endothelium, the natural tissue of blood vessels. Auxetics’ permeability suits innovative filters and smart bandages, facilitating targeted drug delivery to infected areas based on dosage requirements [62,249,250]. In Figure 17a, a proposed auxetic stent with chiral topology is seen. For individuals with esophageal cancer, foldable medical devices known as esophageal stents [251] with auxetic properties offer solutions to the difficulties of swallowing due to tumor blockages. Unique to auxetic stents, their lateral expansion and adaptability to the esophagus provide consistent support, enabling both passage opening and effective delivery of food and drugs. Innovative designs like rotating squares have been suggested for drug-carrying and hierarchical stents [54,168]. Bhullar et al. [168] proposed a rotating square auxetic stent for drug delivery (Figure 17b), while Gatt et al. [54] developed a hierarchical stent based on the same topology (Figure 17c). Coronary artery disease is widespread, and stents are commonly used to prevent blood cell accumulation [216,252]. However, traditional stents do not possess anisotropic characteristics that align with that of blood vessels. Amin et al. [61] addressed this issue by creating auxetic stents designed for coronary arteries, thereby preventing the narrowing of local blood flow. Another potential medical application is auxetic dental floss, which expands laterally when stretched, allowing for more efficient and effective cleaning [180].

Regenerating dynamic organs faces challenges due to anisotropy and volumetric distortion. Meta-biomaterials, like vascular grafts with auxetic effects, show promise in tissue regeneration with improved mechanical and biological properties, providing potential solutions for regenerative therapy challenges [253]. Auxetic behavior also enhances implant–bone contact [251,254]. Kolken et al. [251] proposed six hybrid meta-implants with varying Poisson ratios, selecting the best-performing one for hip stem fabrication. Recent research by Kolken et al. [254] confirmed that auxetic meta-biomaterials made from Ti–6Al–4V exhibit similar performance to bones. Additionally, Arjunan et al.’s [255] study on auxetic swabs, incorporating auxetic structures, demonstrated an innovative approach to improving patients’ comfort during testing by minimizing stress on surrounding tissues. This research highlights the transformative potential of 3D printing in addressing crucial challenges in biomedical device development. Auxetics are gaining momentum in bio-medicine, with potential applications in various domains. However, most are still in the prototype phase, necessitating further research. Challenges include manufacturing and long-term performance. However, auxetics are already widely utilized in sports and tissue engineering. The most transformative impact could be in medical instruments and implants, like expandable structures for minimally invasive procedures. Potential applications include expandable tubes, endoscopes, colonoscopes, and functionally graded implants. Emerging trends involve synergies between four-dimensional printing and auxetic geometries, shape-memory materials, and bio-hybrid materials for autonomous actuators.

3.4 Protection and sports

Auxetic polymers, such as auxetic foams studied by Sanami et al. [256], contribute to improved resilience in protective helmets and vests against impacts and shrapnel, enhancing human protection devices. Auxetic materials’ unique indentation behavior enables them to flow from different directions upon impact, effectively mitigating force and potentially preventing or minimizing head injuries. Their exceptional properties, including shape-adaptive properties, energy absorption, high permeability, and synclastic curvature, contribute to their growing use in protective clothing and equipment for sports [89,257]. They offer improved comfort and protection for vulnerable body parts like knees, elbows, head, and hips, as shown in Figure 18a, serving as foam replacements in protective gear and enhancing flexibility. Traditional seat belts, with a positive Poisson ratio, can pose risks during accidents [259]. An alternative braid structure with an NPR widens the contact area, enhancing safety measures, as shown in Figure 18b [258,260]. Auxetics have also found application in the sports industry, employed in mats, gloves, pads, and helmets [72]. These auxetic protective devices offer superior cushioning capacity and effective energy absorption. A notable example of an auxetic application is under armor, a sportswear company with patented Micro G for training shoe soles. In Figure 18c, polymeric auxetic foams, renowned for robust indentation performance and optimized weight absorption, were used to manufacture the skin and soles of the sports shoes. Wang et al. [88] conducted an analytical investigation on cushioning contact problems and found that using NPR cushions can reduce pressure and enhance comfort. Notably, auxetic products are already available in the commercial market [63,72].

3.5 Textile industry

The continuous production of auxetic materials in fibrous form has opened up new possibilities for utilizing the unique properties of NPR structures in various applications. These auxetic textiles are crafted from either auxetic or standard fibers, resulting in complex textile structures that exhibit auxetic characteristics [257,261–263]. Various techniques have been reported for manufacturing auxetic yarns [257]. Liu et al. [264] developed NPR weft-knitted fabrics, as illustrated in Figure 19a, using computerized flat-knitting technology. This study revealed the relationship between the fabric’s structural parameters and its NPR effects. Building on this, Steffens et al. [267] used para-aramid and polyamide fibers to create innovative auxetic textile structures through knitting technology. They explored how variations in loop lengths, cover factors, yarn densities, and machine settings influence the NPR of knitted structures, demonstrating their potential in creating protective gear such as bulletproof vests and helmets. Furthermore, Hu et al. [265] also delved into the production of auxetic weft-knitted fabrics, focusing on three geometric structures, as depicted in Figure 19d. It studies their auxetic behavior and Poisson’s ratio–strain relationships, highlighting flat-knitting technology’s potential in crafting advanced fabrics with unique mechanical properties for various applications.

![Figure 19

(a) Knitting pattern using zigzag face and reverse loops for purl structure [264]; (b) warp knit structures: (i) unstretched, (ii) stretched, and (iii) fabric structure displaying auxetic behavior [86]; (c) (i) conventional structure and (ii) auxetic structure[87]; (d) the initial knitting patterns and stretched states of auxetic fabrics created with (i) rectangular face and reverse loops, (ii) horizontal and vertical stripe face and reverse loops, (iii) rotating rectangles [265]; (e) HAY in woven fabrics [266], and (f) 3D auxetic woven structure showing the schematic and real fabric [261].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_019.jpg)

(a) Knitting pattern using zigzag face and reverse loops for purl structure [264]; (b) warp knit structures: (i) unstretched, (ii) stretched, and (iii) fabric structure displaying auxetic behavior [86]; (c) (i) conventional structure and (ii) auxetic structure[87]; (d) the initial knitting patterns and stretched states of auxetic fabrics created with (i) rectangular face and reverse loops, (ii) horizontal and vertical stripe face and reverse loops, (iii) rotating rectangles [265]; (e) HAY in woven fabrics [266], and (f) 3D auxetic woven structure showing the schematic and real fabric [261].

Nazir et al. [266] concentrated on helical auxetic yarn (HAY) in woven fabrics (Figure 19e), discovering that mat weave patterns in fabric showcase the highest NPR, suggesting optimal auxetic behavior and stability under tension, beneficial for applications such as filtration and impact energy absorption. A warp-knitted structure was created by Ugbolue et al. [86] (Figure 19b) based on the helical yarn model, demonstrating auxetic behavior when stretched. This study highlighted the potential of integrating vertical (warp) and horizontal (weft) filling yarns in such structures to transform the protective clothing industry and beyond. Another approach involves a unique winding process where a fine, stiff filament encases thick, soft filaments [180]. Different types of wrap-knitted meshed structures, both conventional and auxetic, have also been proposed using spandex polyester, as shown in Figure 19c [87]. In addition, Alderson et al. [85] introduced auxetic fabrics based on double arrowhead structures, highlighting distinct stretching behaviors compared to conventional fabrics. Lastly, Zeeshan et al. [261] discussed the potential applications of 3D auxetic woven fabrics (Figure 19f). Thanks to their distinctive in-plane auxetic behavior, these fabrics are particularly well-suited for industries requiring materials that adapt under stress or offer enhanced cushioning and protection. Auxetic fabrics are useful for children’s clothes, enabling longer use of well-fitting garments, and they offer comfort to pregnant women by naturally fitting expanding abdomens [257]. These fabrics can also enhance bras, sportswear, and safety belts.

3.6 Sensing and actuating devices

Auxetic materials, known for their unique applications in piezoelectric sensors, actuators, and shape-memory alloys (SMA), offer several benefits. For instance, auxetic metals have the potential to function as electrodes that encircle a piezoelectric polymer. Likewise, auxetic polymer matrices can incorporate piezoelectric ceramic rods [268]. These configurations are believed to double or even further increase the sensitivity of piezoelectric devices. Additionally, there is a growing interest in using auxetic materials for micro- and nanoscale mechanical and electromechanical devices. Advances in designing, analyzing, and manufacturing metamaterials have generated interest in their sensor and actuating device applications [197]. With extraordinary mechanical properties, auxetic metamaterials find use in various applications such as strain sensors [269–273], pressure sensors [274,275], multimodal sensors [276–278], mechanical actuators [279], pneumatic actuators [280,281], and thermal actuators [282].

Research in this field has led to innovative developments. For instance, Abramovitch et al. [283] proposed a novel detecting sensor consisting of a piezoelectric sensor embedded in a tetra-chiral auxetic structure unit cell, as shown in Figure 20. This device detects signals and acts as a load-bearing unit, making it suitable for structural health monitoring. Figure 20a depicts a piezoelectric sensor with an auxetic matrix, illustrating its effect [284]. Lee et al. [272] demonstrated a capacitive strain sensor with a re-entrant auxetic elastomer dielectric, achieving a gauge factor 3.2 times higher than its non-auxetic counterpart, thanks to its in-plane NPR (Figure 20b). When compressed, the radial expansion of the non-auxetic ceramic rods is helped by the radial contraction of the auxetic polymer matrix. Similarly, Lee et al. [279] created a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) auxetic tubular springs for hopping robots using fused deposition modeling, as shown in Figure 20c [150]. These springs, with their NPR, become stiffer during compression, allowing them to store more energy compared to conventional springs. Rossiter et al. [285] developed and tested a hexa-chiral topology shape-memory polymer (SMP) in shape memory, as depicted in Figure 20d. The auxetic SMP deployment function could be achieved without external actuators. Furthermore, researchers have combined the deformation capabilities of auxetics with SMAs to propose innovative functional structures [286,287]. While there have been encouraging developments in the use of auxetics for sensors and actuators, there are substantial obstacles that need to be overcome to fully exploit their capabilities. One major hurdle pertains to the production process, especially when dealing with micro- and nanoscale unit cell structures. Despite the emergence of various manufacturing techniques, predominantly driven by additive manufacturing, creating complex structures using different materials remains a challenge.

![Figure 20

(a) An auxetic tetra-chiral unit cell with an embedded sensor [283]; (b) a piezoelectric sensor with an auxetic matrix [284]; (c) the stretched shape of (i) pristine elastomer and (ii) auxetic elastomer [272]; (d) compressed auxetic tubular spring [279]; and (e) hexa-chiral auxetics made of SMP showing its original state, compressed state, and deployed shape after recovery [285].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_020.jpg)

(a) An auxetic tetra-chiral unit cell with an embedded sensor [283]; (b) a piezoelectric sensor with an auxetic matrix [284]; (c) the stretched shape of (i) pristine elastomer and (ii) auxetic elastomer [272]; (d) compressed auxetic tubular spring [279]; and (e) hexa-chiral auxetics made of SMP showing its original state, compressed state, and deployed shape after recovery [285].

3.7 Nails and fasteners

Researchers have shown interest in developing auxetic fasteners and nails (Figure 21) due to the unique behavior of auxetics [63,290,291]. Choi and Lakes [292] explored the design of a fastener using NPR foam, emphasizing its lateral contraction under compression and elastic expansion under tension. According to their study, an auxetic fastener might offer ease of insertion and increased resistance to removal. Building on this, Ren et al. [288] created the first auxetic nails, inspired by their earlier work on auxetic tubular structures. They evaluated four categories of auxetic nails, as illustrated in Figure 21a. However, it was observed in the study that the performance of auxetic nails does not demonstrate a significant advantage over conventional nails, attributed to challenges in the design and production process. Kasal et al. [289] designed, produced, and tested various 3D-printed auxetic dowels, as shown in Figure 21b, for furniture joints, analyzing their withdrawal strength and finding significant potential in furniture construction. Figure 21c shows an auxetic dowel designed by Kuskun et al. [290]. Exploring auxetic fasteners and nails is a recent but promising field, offering potential benefits like enhanced grip and resistance to loosening, especially in dynamic environments. However, further research is needed to refine their design and material choices. Unlike regular nails, auxetic materials expand sideways under compression or tension.

![Figure 21

(a) Auxetic nail behavior during (i) push-in and (ii) pull-out, and (iii) 3D-printed auxetic nails categorized into four groups made from brass and stainless steel. The left column is auxetic nails, the middle column is nails with circular holes, the right column is solid nails [288], (b) (i) a 3D view of the dowel and their (ii) cross-section [289] and (c) Kuskun et al. designed dowels [290].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0021/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0021_fig_021.jpg)

(a) Auxetic nail behavior during (i) push-in and (ii) pull-out, and (iii) 3D-printed auxetic nails categorized into four groups made from brass and stainless steel. The left column is auxetic nails, the middle column is nails with circular holes, the right column is solid nails [288], (b) (i) a 3D view of the dowel and their (ii) cross-section [289] and (c) Kuskun et al. designed dowels [290].

4 Challenges and prospects

While various potential applications for auxetic structures have been investigated in the pieces of literature reviewed, practical implementations are limited. Some challenges remain, including selecting materials with the right auxetic and mechanical properties. Standardized property tables and characterization testing for auxetic structures are essential for practical implementation. Research on the fatigue performance and toughness of auxetic structures is limited, which calls for more experiments to accurately predict their lifetime. While current research often focuses on additive manufacturing polymers, exploring other materials, such as different types of metallic and ceramic-built structures, holds potential for different applications. Further study is needed on how additive manufacturing parameters affect product mechanical properties. Additionally, the widespread adoption of additive manufacturing materials in mass production is hindered by high costs. The micro-manufacturing of auxetic structures, beyond foams, also remains underexplored. Addressing these challenges will contribute to the realization of the potential benefits offered by auxetic structures in various engineering applications. Furthermore, durability under various conditions, including cyclic loading and extreme environmental conditions, is crucial for practical use. Standardized testing and methods are needed for accurate performance assessment and comparison. Research into composites that blend auxetic materials with stronger materials can pave the way for more structural applications. Balancing auxetic behavior with enhanced mechanical properties requires meticulous design and optimization, often employing advanced simulation tools. These efforts aim to harness auxetics’ unique properties effectively, ensuring resilience and functionality across a spectrum of applications.

Auxetic materials hold great potential for the development of innovative solutions in bio-medical applications, such as tissue scaffolds, wound dressings, and various kinds of implants. Their ability to replicate the behavior of biological tissues under loading makes them viable for applications that require interaction with the human body. The possibilities are amazing: expandable tubes, endoscopes, and implants that match the shape of the human body, increasing usability and comfort during use. It can be achieved through the combination of auxetic structures with advances in manufacturing technologies, shape-memory materials, and bio-hybrid materials.

Additionally, programmable auxetics can unlock great opportunities as they may be adjusted to meet unique requirements, and they open up even more options. Consider auxetics that regulate motion, sound, or even chemical processes. This provides opportunities for wearable electronics and robotics, next-generation implants with enhanced functionality. Additionally, auxetic materials have demonstrated potential in improving the performance, comfort, and adaptability of athletics, technical textiles, and apparel. This is because of their multidirectional stretchability, which can result in a better fit and improved durability, which makes them revolutionary for athletic wear and practical apparel.

Besides the human-related applications, auxetic materials’ capacity to reduce weight and boost strength and energy absorption can have a major positive impact on aerospace and vehicle safety and fuel economy. Auxetic materials may also pave the way for the creation of earthquake-resistant and adaptable structures in design and construction. As their mechanical deformation is unique, they can be exploited to design buildings capable of adjusting to changing loads and other environmental conditions dynamically. Their mechanical deformation characteristics might be used to create piezoelectric and energy-absorbing devices that are more effective, advancing the production and storage of renewable energy. This makes auxetic materials promising options for applications involving energy harvesting and storage. Their tunable porosity and mechanical properties could lead to the development of more efficient and sustainable filtration membranes, water purification systems, and pollution control technologies. The ability to control the flow of fluids or gases through auxetic structures opens doors for advancements in filtration and microfluidics.

5 Conclusions

This article summarizes the development and applications of auxetic materials across different scales through a thorough research review. It summarizes the key types of synthetic auxetic materials, covering various unit cell structures, expected mechanical properties, and applications. It serves as a valuable resource for researchers and engineers exploring auxetic materials. It also highlights the significant benefits of auxetic materials in various fields such as medicine, sports, protective gear, textiles, and sensing and actuating devices, underlining their potential in engineering applications. However, there is a need for further research to implement on full scale and fulfil the complex and multifaceted demands of future engineering applications. There are still many obstacles in the development, production, and analysis of structures for practical applications. The creation of multi-functional, cross-disciplinary, smart, and ergonomic metamaterials is poised to become a leading area of research and development. In essence, auxetic materials represent a groundbreaking advancement with the potential to transform numerous fields. From healthcare and textiles to construction and energy, these materials offer exciting possibilities for lighter, stronger, more adaptable, and more efficient solutions across the spectrum of human endeavors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the support by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4300101), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023JJ10074), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC1011).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFB4300101), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2023JJ10074), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC1011).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Yang, W., Z.-M. Li, W. Shi, B.-H. Xie, and M.-B. Yang. Review on auxetic materials. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 39, 2004, pp. 3269–3279.10.1023/B:JMSC.0000026928.93231.e0Search in Google Scholar

[2] Evans, K. E. Auxetic polymers: A new range of materials. Endeavour, Vol. 15, No. 4, 1991, pp. 170–174.10.1016/0160-9327(91)90123-SSearch in Google Scholar

[3] Voigt, W. Allgemeine Formeln für die Bestimmung der Elasticitätsconstanten von Krystallen durch die Beobachtung der Biegung und Drillung von Prismen. Annalen der Physik, Vol. 252, No. 6, 1882, pp. 273–321.10.1002/andp.18822520607Search in Google Scholar

[4] Love, A. E. A treatise on the mathematical theory of elasticity, 4th ed., Cambridge University Press, New York, 1927.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Evans, K. E. and A. Alderson. Auxetic materials: Functional materials and structures from lateral thinking! Advanced Materials, Vol. 12, No. 9, 2000, pp. 617–628.10.1002/(SICI)1521-4095(200005)12:9<617::AID-ADMA617>3.0.CO;2-3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Li, Y. The anisotropic behavior of Poisson’s ratio, young’s modulus, and shear modulus in hexagonal materials. Physica Status Solidi (a), Vol. 38, 1976, pp. 171–175.10.1002/pssa.2210380119Search in Google Scholar

[7] Keskar, N. R. and J. R. Chelikowsky. Negative Poisson ratios in crystalline SiO2 from first principles calculations. Letters to Nature, Vol. 358, 1992, pp. 222–224.10.1038/358222a0Search in Google Scholar

[8] Gunton, D. D. and G. A. Saunders. The Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of arsenic, antimony and bismuth. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 7, 1972, pp. 1061–1068.10.1007/BF00550070Search in Google Scholar

[9] Grima, J. N., R. Jackson, A. Alderson, and K. E. Evans. Do zeolites have negative Poisson’s ratios? Advanced Materials, Vol. 12, No. 24, 2000, pp. 1912–1918.10.1002/1521-4095(200012)12:24<1912::AID-ADMA1912>3.0.CO;2-7Search in Google Scholar

[10] Pacheco-Sanjuán, A. and R. C. Batra. Insights into the auxetic behavior of graphene: A study on the temperature dependence of Poisson’s ratio and in-plane moduli. Carbon, Vol. 215, 2023, id. 118416.10.1016/j.carbon.2023.118416Search in Google Scholar

[11] Qin, R., J. Zheng, and W. Zhu. Sign-tunable Poisson’s ratio in semi-fluorinated graphene. Nanoscale, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2017, pp. 128–133.10.1039/C6NR04519GSearch in Google Scholar