Abstract

Interfacial bonding between the fibers and matrix plays a large role in mechanical properties of composites. In this paper, poly(oxypropylene) diamines (D400) and graphene oxide (GO) nanoparticles were grafted on the desized 3D multi axial warp knitted (MWK) glass fiber (GF) fabrics. The surface morphology and functional groups of modified glass fibers were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR). Out-of-plane compression properties and the failure mechanisms of composites at different temperature were tested and analyzed. The results revealed that GO nanoparticles were successfully grafted on fibers under the synergistic effect of D400. In addition, D400-GO-grafted composite possessed the highest mechanical properties than desized composite and GO-grafted composite. Their strength and modulus were improved by 10.16%, 10.06%, 8.92%, 8.75%, 7.76% and 40.38%, 32.74%, 29.85%, 26.98%, 25.16% compared to those of desized composites at 30∘C, 60∘C, 90∘C, 120∘C, 150∘C, respectively. The damage to D400-GO-grafted composite was yarns fracture accompanied with fibers breakage, matrix cracking, interface debonding. At higher temperature, interlayer slipping with matrix plasticization was the main failure mode.

1 Introduction

Graphene oxide (GO) as a kind of graphene derivative has attracted significant attention due to its unique two-dimensional nano-laminated structure, large specific surface area, and abundant carboxyl, hydroxyl and carbonyl functional groups distributed on the surface and edges, which enables various covalent chemical modification simple and convenient [1]. Das et al. [2] synthesized multilayer GO via electrochemical exfoliation method based on organic liquid-assisted solvent. Chen et al. [3] summarized that GO could be further used to fabricate graphene quantum dots which is a new kind of fluorescent carbon materials with unique structure of a single atomic layer. GO has been widely used in medicine field owning to its large plain surface area which provides advantages for drug and protein delivery [4]. Jiao et al. [5] loaded different amounts of drugs on carboxy-methyl cellulose-grafted graphene oxide, and high drug-loading efficiency and encapsulation efficiency were achieved, which could reach 39.33% and 29.50%. Innovative nano-drug (Ori@GE11-GO) was prepared to recognize the specific tumour cells, and improve anticancer efficiency [6]. Graphene-based substrates was applied as adsorbent and photocatalyst to remove oil and organic/inorganic contaminants [7]. Yu et al. [8] constructed thermally evolved and boron bridged GO framework on hollow fibers to separate organic matters, indicating the potential application in wastewater treatment. N-doped FeOOH/RGO hydrogels was researched to enhance removal rate of organic pollutants [9]. Visible-light-induced self-cleaning functional fabrics was fabricated based on graphene oxide/carbon nitride materials [10]. GO was also widely applied in electronic fields of electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding [11, 12], electrochemical

sensor [13, 14], supercapacitors and batteries [15, 16], etc. Shahzad et al. [17] synthesized a kind of fluorine-doped reduced graphene oxide which showed higher electrical conductivity of 750 S m−1 than that of undoped rGO which was 195 S m−1, and EMI was simultaneously enhanced. RGO was deposited on a screen-printed gold electrode by electrochemical method with subsequent modification of carbon-gold nanocomposites to prepare gas sensor which possessed good sensitivity and linearity [18]. Single Co atoms (≈ 5.3%) were anchored on graphene oxide to solve the problem of the decomposition of insulating Li2CO3 on the cathode, and it exhibited high sustained discharge capability [19]. GO was also been demonstrated to be effective additives in asphalt as construction and building materials [20]. Lin et al. [21] added GO into rubber asphalt, and found that GO was helpful to formation of dense and stable microstructure together with rubber powder and asphalt polymer, and the modified asphalt possessed good temperature insensitivity. Many researches were done based on graphene to form complex and hierarchical structure [22]. Ultraviolet protection cotton fabric was achieved via self-assembling graphene oxide and chitosan [23]. Graphene oxide sheets [24, 25], epoxy functionalized graphene oxide [26], and carboxylic functionalized graphene [27] were grafted on fibers, and found interfacial properties were improved. However, GO modification of fabrics was rarely reported by now, except from literature of Zhang et al. [28], who prepared antibacterial fabrics by fixing amino-capped silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) on surface of fabrics.

Three-dimensional (3D) multi axial warp knitted (MWK) fabrics were developed due to the performance of each yarn was maximized. The composites possessed the excellent performance to conform to complicated contours in fabrication process, and they were widely applied in aeronautics and astronautics and so on [29]. Many researches were carried out to investigate the mechanical properties of MWK composites. Sun et al. [30] studied the compressive behavior of MWK composite and found that it possessed the highest failure stress comparing with the 3D woven composite and 3D braided composite at the same strain rate. Sugie et al. [31] investigated the impact properties of MWK composites with carbon/glass hybrid fibers. Luo et al. [32] coated PVC on bi-axial warp knitted fabric and demonstrated that the coated fabric exhibited anisotropic properties under both mono-axial and multiaxial tensile loads. Li et al. [33, 34, 35] studied the tension fatigue behavior and failure mechanism of 3D MWK composites, and their tensile and bending properties at cryogenic temperature. Ma et al. [36] added short glass fibers between MWK fabric layers to improve interface strength. However, 3D MWK fabrics are prone to be destroyed and easily delaminate owning to weak binding strength in the through-the-thickness direction between layers. To date, the mechanical properties of composites fabricated with modified MWK fabrics have not been discussed.

By combining the advantages of GO with ample functional groups and MWK fabrics with good mechanical properties, GO modified fabrics were investigated, and their mechanical properties were discussed for the first time. In this paper, HATU was chosen as condensation agents. To improve interfacial strength between GO and fibers, D400 with highly active amino groups at both ends was grafted on fibers of MWK fabrics in advance. Then, GO nanoparticles were grafted on D400 grafted fibers in which flexible D400 also acted as a bridge to improve the interface bonding between fiber and matrix, and further improve mechanical properties of MWK composites. The out-of-plane compression curves, mechanical properties and failure mechanisms of desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite and GO-grafted composite were correspondingly compared. The effect of D400 and GO nanoparticles on interface bonding of fiber/matrix were analyzed.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

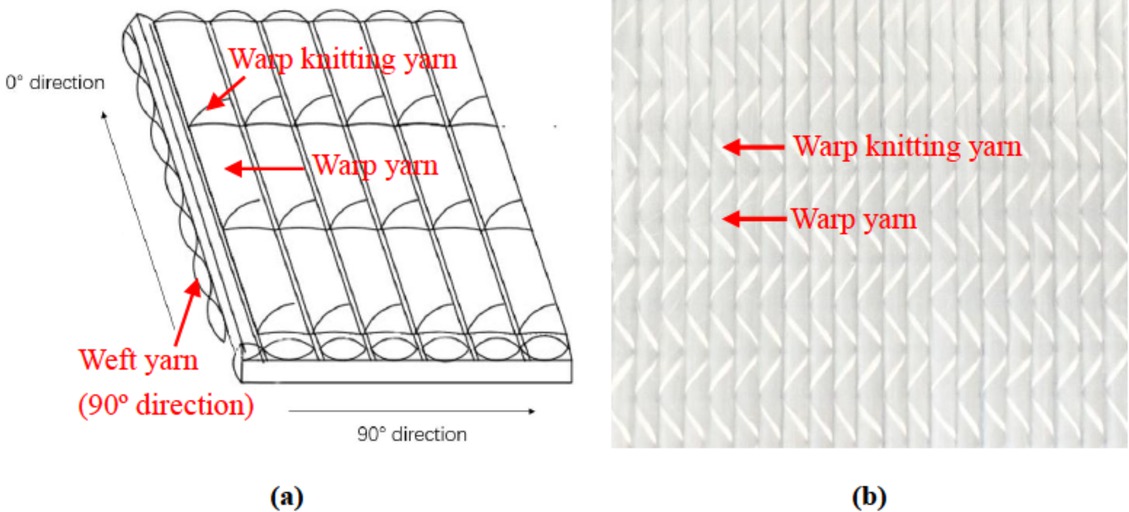

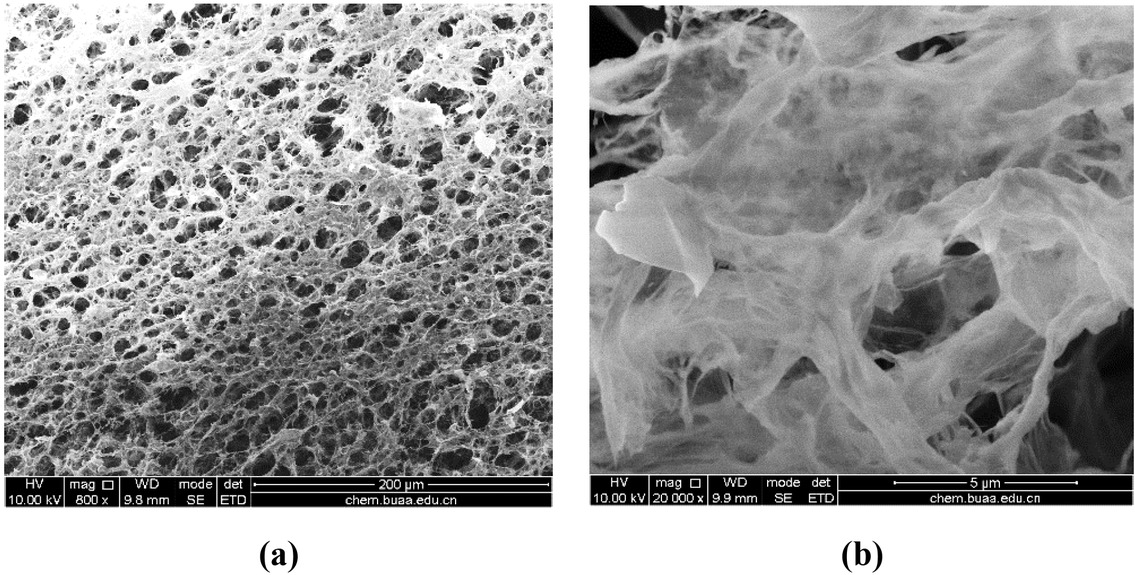

The schematic drawings of 0∘/90∘ MWK used in this study were shown in Figure 1. Epoxy resin TDE-90 (4,5-epoxycyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid diglycidyl ester) was used as matrix. m-phenylenediamine was used as curing agent (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Poly(oxypropylene) Diamines (D400, molecular mass Mn≈ 400) was purchased from Aladdin industrial corporation. N-[(dimethylamino)-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5,6]-pyridin-1-ylmethylene]-N-methylmethana minium hexafluoro-phosphate N-oxide (HATU) (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used as coupling agent. The graphene oxide (GO, Thangshan Jianhua Technology Development Co., Ltd., Tangshan, China) was dispersed in deionized water to prepare GO solution (5 mg/mL). The SEM morphology of GO was presented in Figure 2.

0∘/90∘ multi-axial warp knitted fabric: (a) schematic diagram; (b) MWK fabric

SEM images of GO: (a) magnification with ×800; (b) magnification with ×20000

2.2 Surface modifications of the 3D MWK fabrics

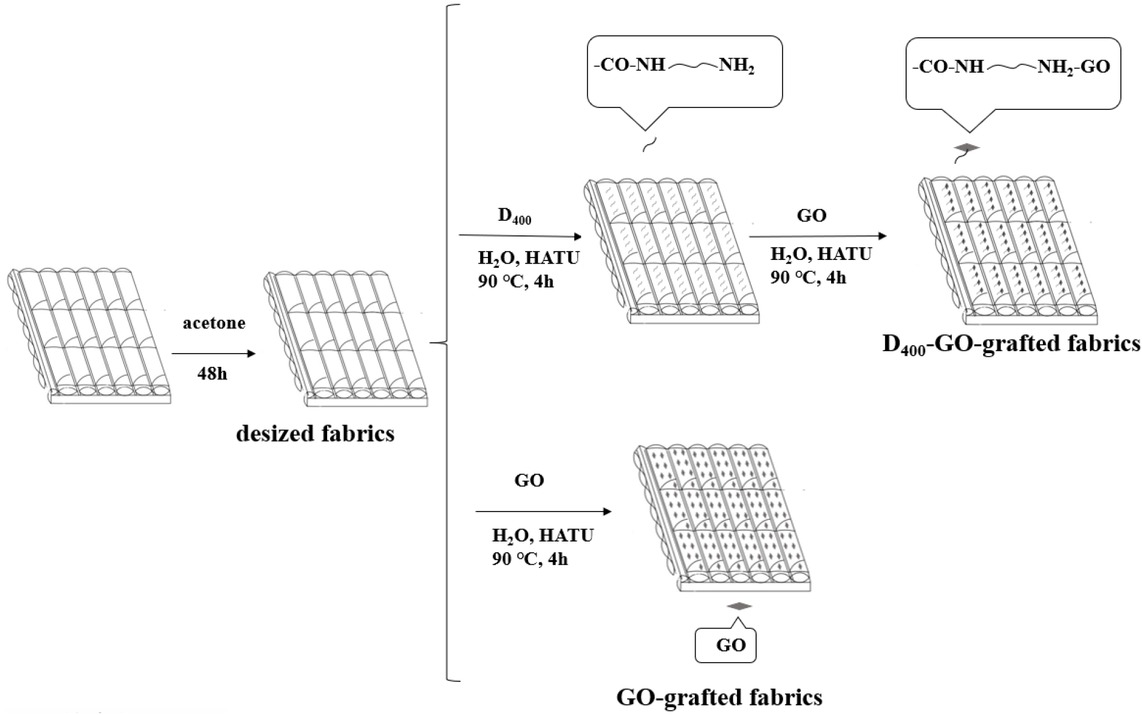

The fabrics were firstly immersed into acetone for 48h to remove the sizing agents, and marked as GF fabrics. Then, they were repeatedly washed with deionized water and dried to obtain the desized GF fabrics. To graft more GO nanoparticles, D400 was used as bridge reagent. In this case, desized fabrics were immersed into solution with 70 mL D400, 140 mg HATU, and 840 mL deionized water, and they were put into oil bath and reacted for 4 h at 90∘C. The obtained D400-grafted fabrics were flushed with excess deionized water to remove the unreacted organics. At last, to graft GO nanoparticles on fiber surface, D400-grafted fabrics were immersed into 5 mg/mL GO solution with 140 mg HATU, and reacted for 4 h at 90∘C. The relevant samples were flushed with deionized water and dried in oven, and they were denoted as D400-GO grafted fabrics. Desized fabrics were also separately immersed into GO solution with 140 mg HATU, and also reacted for 4 h at 90∘C, and the modified fabrics were named GO-grafted fabrics. The grafting schematic diagram was shown in Figure 3.

The scheme of grafting process for three kinds of composites: desized fabrics, D400-GO-grafted fabrics, GO-grafted fabrics

2.3 Fabrication of GF/epoxy composites

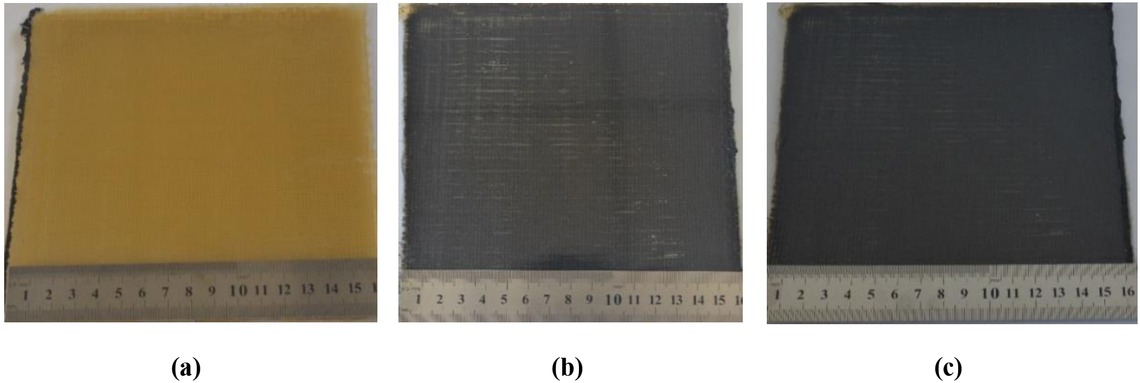

3D MWK composites were prepared by the vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding method, in which the matrix were injected into the preforms and then consolidated in oven (90∘C for 2 h, 120∘C for 2 h). Six layers of fabrics were laid up alternately in 0∘ and 90∘ direction. The desized fabrics, D400-GO-grafted fabrics and GO-grafted fabrics were used in each composite type. The composites were then cut into specimens with size of 10mm×10mm×4.0mm. The fiber volume fractions were 53.45%, 53.32% and 52.34% for desized composites, D400- GO-grafted composites and GO-grafted composites, respectively. Figure 4 showed the photographs of prepared composites. The composites fabricated with GO modified fabrics were black due to GO nanoparticles were grafted on fabrics compared with desized composite in Figure 4a.

The photographs of the prepared 3D MWK composite: (a) desized composite; (b) D400-GO-grafted composite; (c) GO-grafted composite

2.4 Characterization

The chemical structure of the grafted fabrics was examined with a KBr pellet in the range of 500-4000cm−1 on the Fourier transform infrared spectra (FT-IR,Nicolet 6700, USA).

The morphologies of the fabrics and composites were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta 250 FEG, Czech Republic).

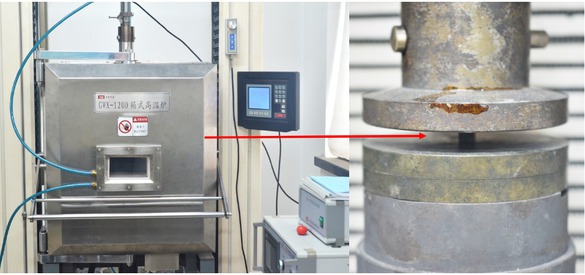

The out-of-plane compression tests were conducted following the HB 7571-1997 standard [37] with the high temperature mechanical machine (Figure 5). Compression tests were conducted at five different temperatures (30∘C, 60∘C, 90∘C, 120∘C, 150∘C), respectively. The crosshead speed was set to 0.5mm/min. During the tests, the load and deformation of all samples were automatically recorded by computer. At least three samples were tested at each temperature.

High temperature compression experiment process

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Morphology of GF with D400 and GO nanoparticles

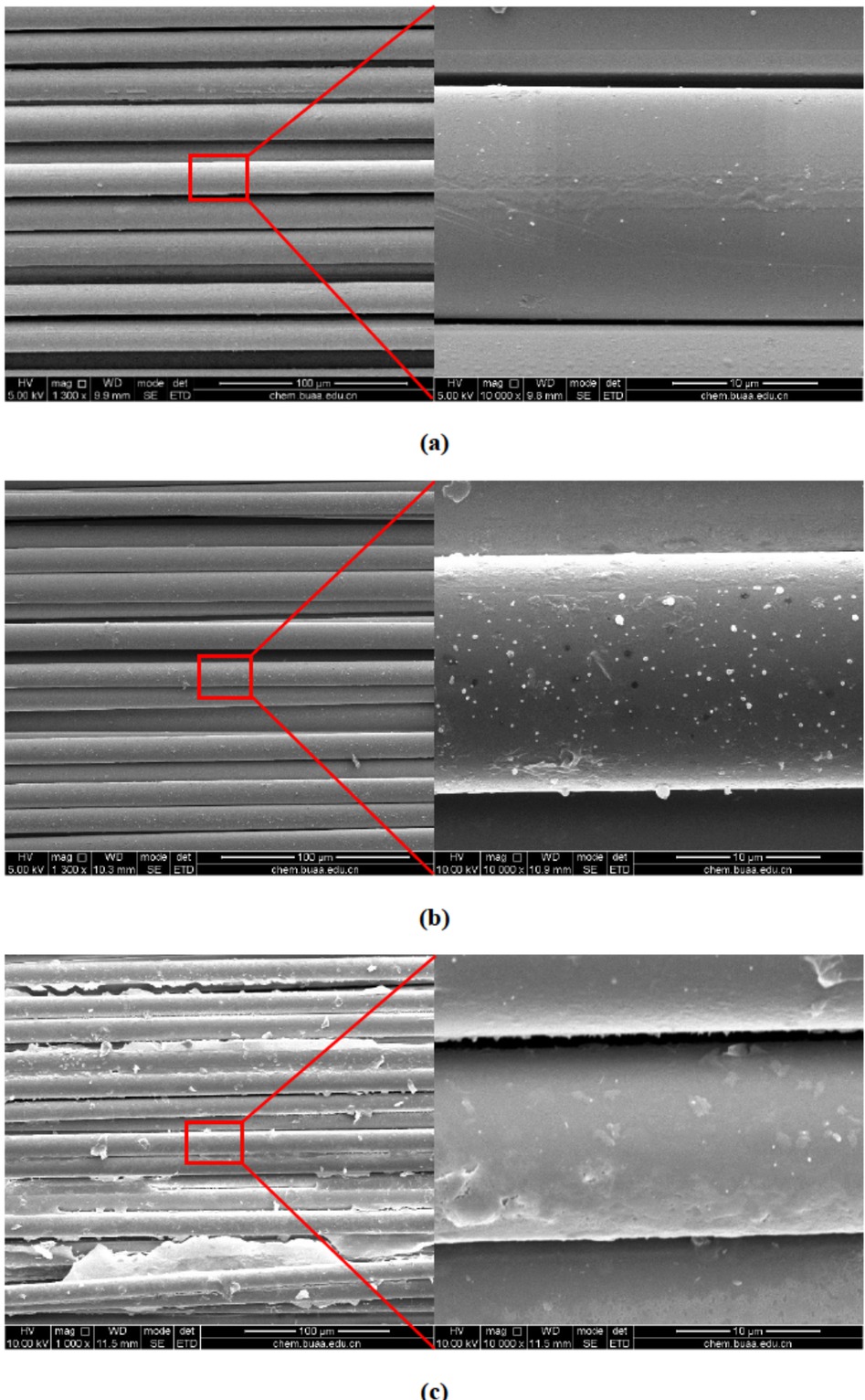

The SEM morphologies of modified GF fabrics were shown in Figure 6. It could be observed that the surface of desized GF was smooth after acetone cleaning (Figure 6a). In Figure 6b, pleat structure of GO on fibers was obvious indicating that layered graphene was successfully grafted on D400-grafted fabrics. This kind of structure could promote stress transfer between carbon fiber and matrix. In Figure 6c, GO nanoparticles coated on fabrics in abundance, and reaction groups of fibers were mostly covered which limited their contact area with matrix in the next curing stage.

SEM images (left, low magnification; right, high magnification) of the glass fiber fabrics: (a) desized GF; (b) D400-GO-grafted GF; (c) GO-grafted GF

3.2 Chemical group analysis of fabrics

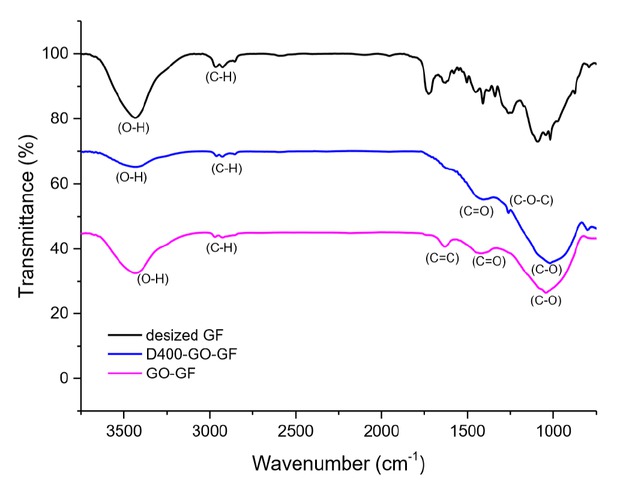

The surface functional groups of desized fibers, D400-GO-grafted fibers and GO-grafted fibers were characterized by FT-IR and the images were presented in Figure 7. It could be observed that peaks of O-H stretching vibration at 3434 cm−1, C-H stretching vibration 2925 cm−1 existed in all three kinds of fibers. Comparing with desized GF, peaks at 1417 cm−1 of C=O stretching, 1044 cm−1 of C-O stretching were obvious for D400-GO-grafted fabrics and GO-grafted fabrics, which demonstrated that GO was successfully grafted on desized fabrics. In terms of GO-grafted fabrics, peak at 1630 cm−1 of C=C stretching vibration appeared, which revealed that most of GO were just coated on the surface of fibers and not adequately reacted with surface organic groups of fibers. While for D400-GO-grafted fabrics, peak of C-O-C stretching at 1260 cm−1 was visible, which indicated that GO nanoparticles reacted well with fibers since D400 acted as a bridge reagent. Other functional groups were mostly removed after cleaning with acetone. New groups were grafted on the GF fabrics again during GO nanoparticles surface modification process.

FTIR-spectra of three kinds of GF

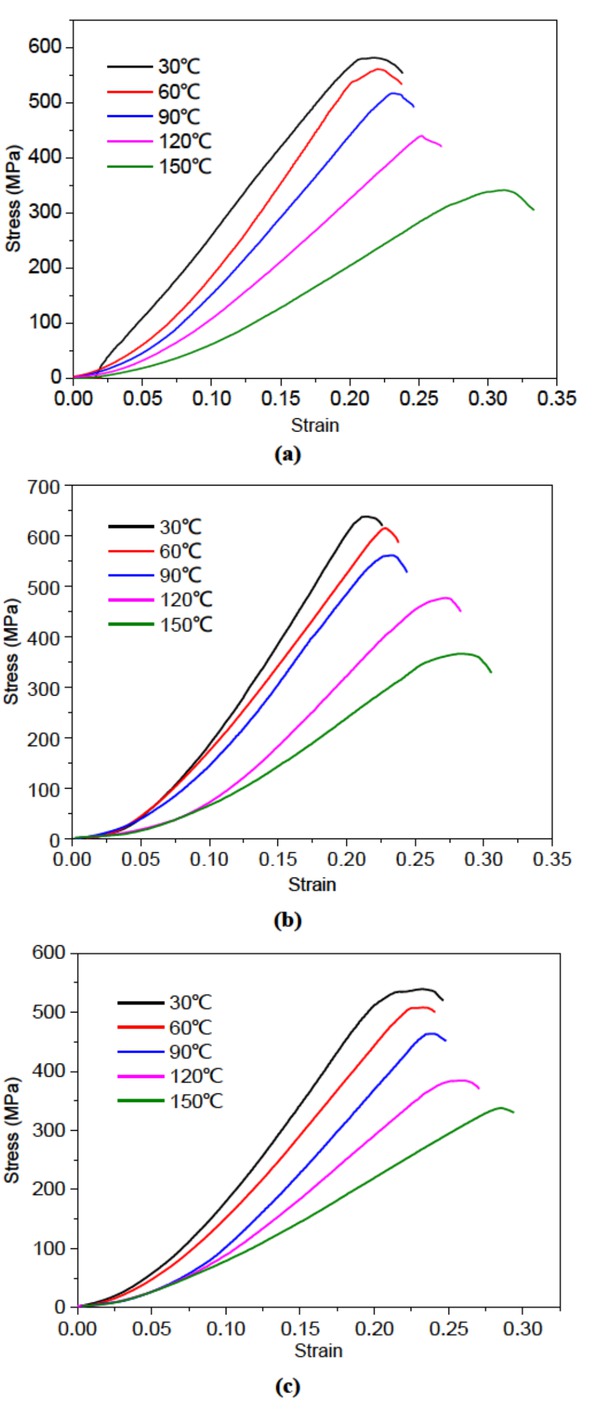

3.3 Compression stress-strain curves

Out-of-plane compression stress-strain curves of desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite, GO-grafted composite at 30∘C, 60∘C, 90∘C, 120∘C and 150∘C were displayed in Figure 8. As the figure shown, curves increased slowly with similar slopes at initial stage, then increased linearly up to the peak quickly with different slopes, and finally dropped immediately for all three kinds of composites. The reason is that the matrix supported the loading at the initial stage, and the modulus was similar at different temperatures; As the load increased, the matrix cracked, the interface bonding force of fiber/matrix bored the main load; At final stage, fibers broke resulting in samples complete failure. In addition, the performances of MWK composites were temperature sensitive, and the maximum stress decreased with increasing temperature. It was due to different thermal-expansion coefficient (CTE) of fibers, matrix and GO. The CTE of glass fiber, matrix and GO were 5.0 × 10−6/∘C [38], 31.7 × 10−6/∘C [39] and −67 × 10−6/∘C [40], respectively. In this case, stress could be effectively transmitted between fibers and matrix at room temperature. With increasing temperature, due to the large difference of CTE among the matrix, glass fibers and GO, the crystallization rate of the matrix around glass fibers and the surface of glass fibers were different. The crystallization zone with gradient distribution led to the existence

Out-of-plane compression stress-strain curves at different temperatures: (a) desized composite; (b) D400-GO-grafted composite; (c) GO-grafted composite

of residual thermal stress, thus the final performance of composites decreased. Then, the fiber/matrix interface bonding got weaker, and stress could not be transmitted effectively among fibers and matrix any more. From 30∘C to 90∘C, the slopes of curves were higher, and the failure strain was shorter. This is because interface bonding between fiber and matrix was well before 90∘C which was also gelation temperature of matrix. While at 120∘C and 150∘C, the failure strain got longer when the curves reached to the maximum stress since the matrix came to be plastic and softening, and the mechanical properties decreased at the same time.

Slopes of D400-GO-grafted composite curves was the highest and maximum stress was the largest comparing to that of desized composite and GO-grafted composite at each temperature. The reason is that GO nanoparticles were grafted on fibers with chemical bond instead of van der Waals force, and interface bonding force of fiber/matrix was improved. -NH2 of D400 at one end reacted with -COOH of fiber, another -NH2 at the other hand acted with -COOH of GO nanoparticles [41]. At the same time, amino could also participate in curing reaction of matrix. Intermolecular bond between fiber and matrix was strengthened. In addition, the structure of D400 is flexible, which could promote the uniform transfer of stress among interface between fibers and matrix. In Figure 8c, the maximum stress of GO-grafted composite was the lowest while its slopes were higher than desized composite at different temperature. Most GO nanoparticles just coated on the surface of fibers through the strength of weak van der Waals force. Therefore, the interfacial bonding between fibers and matrix decreased due to surface of a part of fibers were occupied with GO nanoparticles which limited their contact area with matrix. However, the addition of GO nanoparticles benefited for modulus improvement.

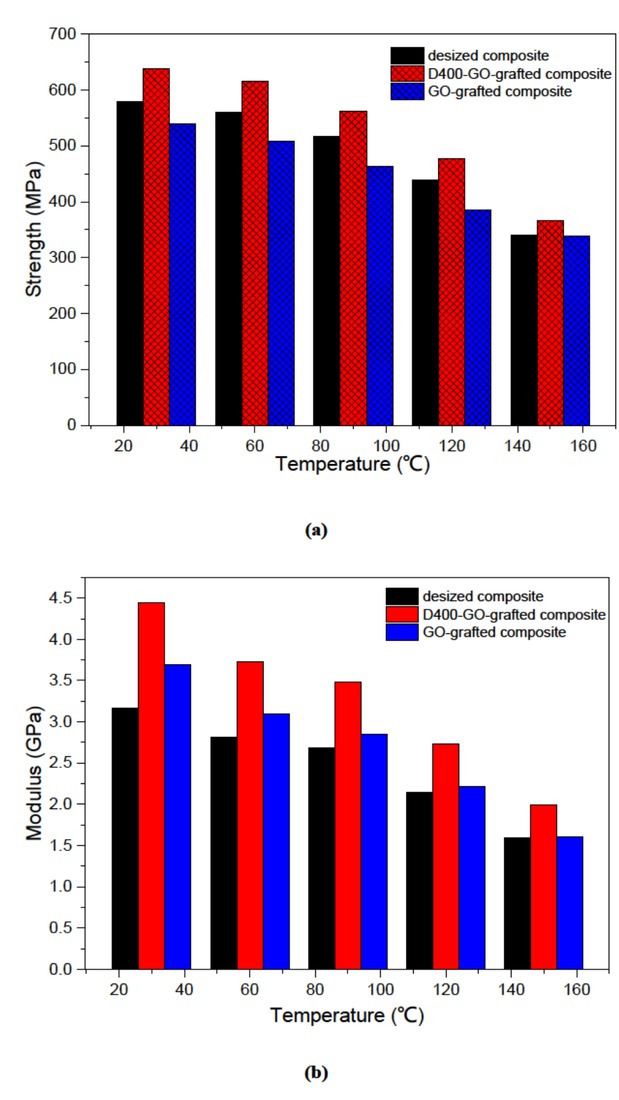

3.4 Compression properties

Out-of-plane compression properties of desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite and GO-grafted composite were shown in Figure 9 and Table 1. D400-GO-grafted composite exhibited the highest strength comparing to desized composite and GO-grafted composite (Figure 9a). Comparing to desized composite, the strength was improved by 10.16%, 10.06%, 8.92%, 8.75%, 7.76% from 30∘C to 150∘C, respectively. This could be attributed to effective graft of D400 and GO nanoparticles on fiber surface. Graft of D400 on fiber surface improved interfacial bonding between fiber and matrix in which high mechanical properties of GO nanoparticles were fully realized [42]. However, comparing to desized composite, the strength of GO-grafted composite decreased by 7.02%, 9.21%, 10.14%, 12.37%, 0.75% from 30∘C and 150∘C, respectively, which manifested that single GO nanoparticles surface modification could not improve mechanical properties of desized composite. It was because D400 played a role of bridge which connected the fibers and GO nanoparticles, and further increased interfacial bonding force of GO nanoparticles, fibers, and matrix. The single GO nanoparticles could not effectively graft on fibers and were easy to peel off.

Out-of-plane compression properties of desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite, GO-grafted composite: (a) strength; (b) modulus

Out-of-plane compression strength and modulus of composites

| Temperature (∘C) | Desized composite | D400-GO-grafted composite | GO-grafted composite | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | Modulus | Strength | Modulus | Strength | Modulus | |

| (MPa) | (GPa) | (MPa) | (GPa) | (MPa) | (GPa) | |

| 30 | 579.87 | 3.17 | 638.80 | 4.45 | 539.18 | 3.69 |

| 60 | 559.59 | 2.81 | 615.90 | 3.73 | 508.04 | 3.09 |

| 90 | 516.09 | 2.68 | 562.11 | 3.48 | 463.78 | 2.85 |

| 120 | 438.95 | 2.15 | 477.34 | 2.73 | 384.64 | 2.22 |

| 150 | 340.60 | 1.59 | 367.03 | 1.99 | 338.04 | 1.61 |

In Figure 9b, the modulus of D400-GO-grafted composite presented the highest value when temperature changed from 30∘C to 150∘C comparing to desized composite, they were improved by 40.38%, 32.74%, 29.85%, 26.98%, 25.16%, respectively. This is because high mechanical properties of GO nanoparticles which is with excellent stiffness performance improved the mechanical properties of composites [43]. Meanwhile, the modulus of GO-grafted composite was improved by 16.40%, 9.96%, 6.34%, 3.26%, 1.26% comparing to desized composite from 30∘C to 150∘C. This because many GO nanoparticles with high mechanical properties were introduced into composite. However, the effects were not good as that of D400-GO-grafted composite owning to weak interfacial bonding force without D400 acting as bridge agent.

3.5 Failure mechanism

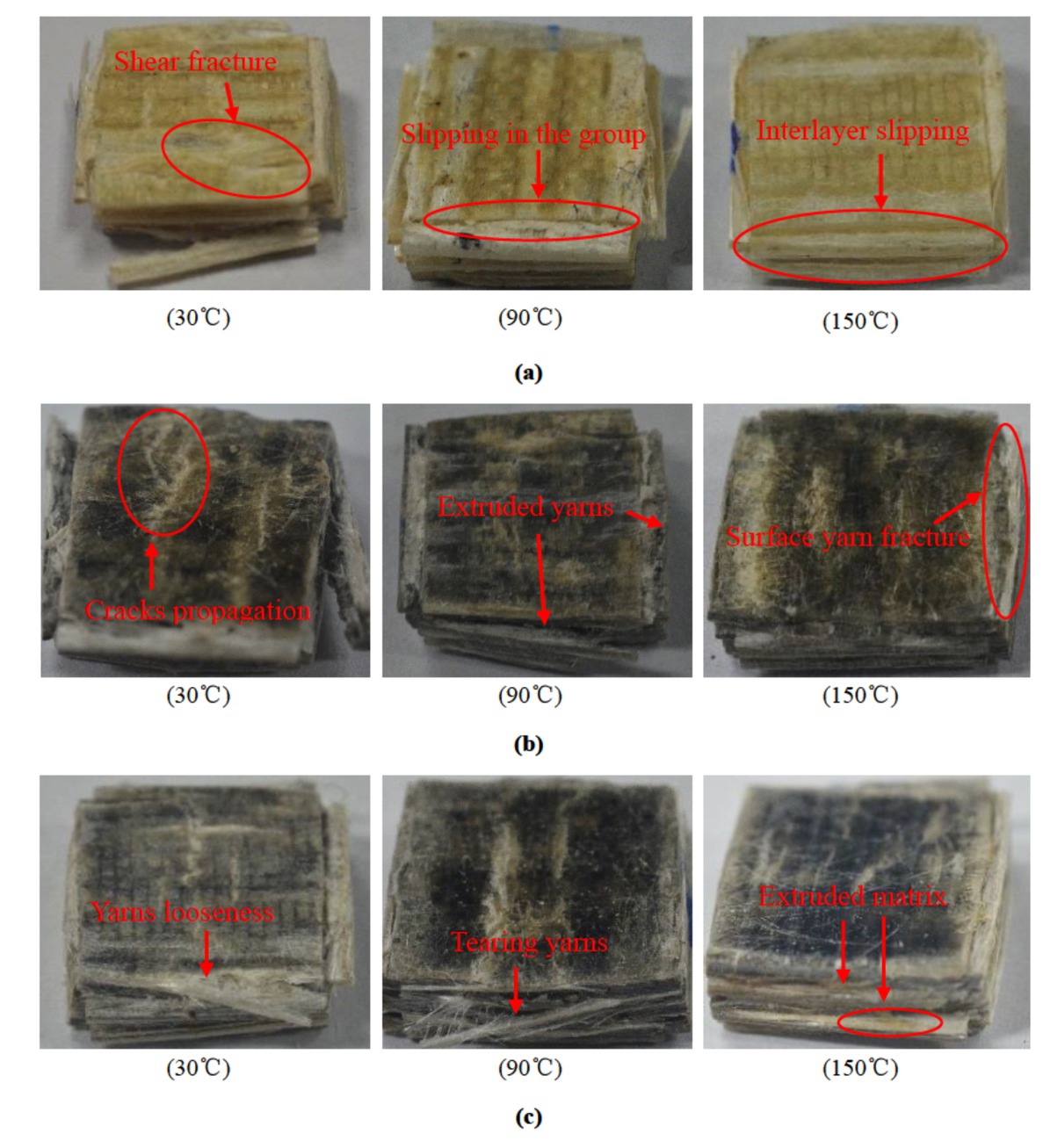

Figure 10 showed out-of-plane compression fracture morphologies of composites tested at different temperatures (30∘C, 90∘C and 150∘C). During compression, warp knitting yarns were easy to broken which finally led to yarns prone to be extruded under stress for MWK composites. At 30∘C, it could be observed that the failure mode was yarns fracture for all three kinds of composites. Surface fabrics were seriouly crushed, and cracks appeared on the surface layer. At 90∘C, extrusion of yarns could be seen due to the fracture of warp knitting yarns, and interlayer slipping feature also began to take place. This is because of that matrix began to soften and layer-to-layer bond strength

Out-of-plane compression fracture morphologies at different temperatures: (a) desized composite; (b) D400-GO-grafted composite; (c) GO-grafted composite

came to lose their effect. At 150∘C, macro-appearance of three kinds of composites maintained integrity, and the main failure mode was interlayer slipping since matrix got soft [44]. The matrix could not transmit stress to fibers effectively since its decreased mechanical properties at high temperature, resulting in fibers could not fully supporting load. The plasticity of matrix led to the final failure of composites. The damage to D400-GO-grafted composite was obvious at each temperature, and then were the desized composite and the GO-grafted composite. This was because synergiestic effects of D400 which improved the interfacial bonding of fiber/matix and GO nanoparticles which improved mechanical properties, and finally led to stress was transmitted effectively. Thus, surface cracks, yarns extrusion phenomenon was the most serious. The damage to GO-grafted composite was small owning to weak interface bonding between fiber and matrix, and stress transmission was not efficient. At the same time, interlayer slipping phenomenon was serious owning to the weakest interface bonding of fiber/matrix.

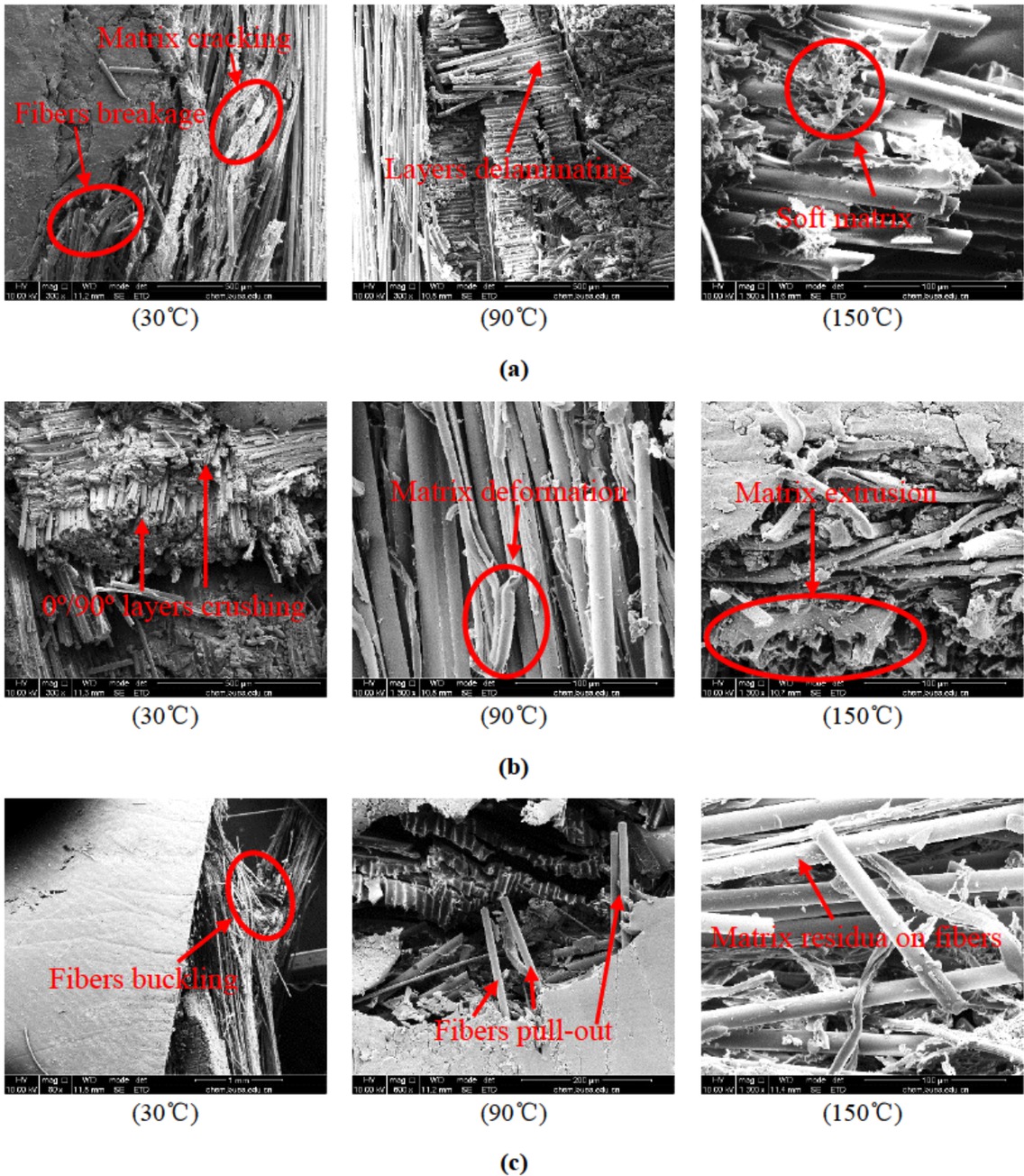

SEM morphologies in Figure 11 further demonstrated compression failure mode of desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite and GO-grafted composite (30∘C, 90∘C and 150∘C). For desized composite in Figure 10a, at 30∘C, matrix cracking and fibers breakage were obvious resulted from warp knitting yarns breakage during compression. However, fibers and matrix maintained the good adhesion since CTE of matrix and fiber matched well at 30∘C. At 90∘C, fibers fracture, layers delaminating was obvious caused by softening matrix and weak interface bonding strength. At 150∘C, matrix plasticization got more serious which led to weaker fiber/matrix interface bond. For D400- GO-grafted composite in Figure 10b, 0∘ fabric and 90∘ fabric crushing damage were the main failure mode at 30∘C. This is because that graft of D400 and GO nanoparticles improved interfacial bonding force of fiber/matrix. The fibers bore the main load, the fracture feature of fibers was severe, and multiple breaks occurred in a single fiber comparing with desized composite. At 90∘C, matrix deformation and fiber shear fracture appeared. At 150∘C, the softening matrix was extruded. For GO-grafted composite, fibers buckling phenomenon was seen at 30∘C. At 90∘C, fibers pull-out, interface debonding, fibers fracture led to the failure of composite. At 150∘C, some GO nanoparticles remained on the surface of fibers since weak bonding force with matrix without grafting D400. In addition, it could be seen that interface debonding occurred on interface of fiber/matrix for desized composite while on interface GO/matrix for D400-GO-grafted composite and GO-grafted composite.

SEM photographs of out-of-plane compression fracture for three kinds of composites: (a) desized composite; (b) D400-GO-grafted composite; (c) GO-grafted composite

4 Conclusions

GO was successfully grafted on 3D MWK fabrics based on D400, and D400-GO-grafted composite was fabricated. Out-of-plane compression stress-strain curves increased linearly at initial stage with decreased slopes with increasing temperature for desized composite, D400-GO-grafted composite and D400-grafted composite. The mechanical properties decreased with increasing temperature due to softening matrix and declined interfacial bonding. D400 and GO nanoparticles synergistically improved the binding force of 3D MWK fabrics with matrix due to reaction between matrix, D400 and GO nanoparticles took place during consolidation stage. The mechanical properties of D400-GO-grafted composite were improved especially at room temperature.

The main failure mode for MWK composite was yarns broken with fibers breakage, matrix cracking, interface debonding at low temperature. At higher temperature, the main damage was interlayer slipping owing to matrix got soft. The damage to D400-GO-grafted composite was most serious since its high interfacial bonding force between D400-GO-grafted fibers and matrix, and fibers could effectively bear load. The destruction to GO-grafted composite was less serious comparing with D400-GO-grafted composite since the bonding way was van der Waals force, and stress could not be effectively transmitted. Interface debonding between fibers and matrix mainly led to failure of composite. Interface debonding occurred on the interface between fiber and matrix for desized composite while on GO and matrix for D400-GO-grafted composite and GO-grafted composite.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Excellent Young Scientist Foundation of NSFC (No. 11522216); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11872087); Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. 2182033); Aeronautical Science Foundation of China (No. 2016ZF51054); The 111 Project (No. B14009). Project of the science and Technology Commission of Military Commission (No. 17-163-12-ZT-004-002-01); Foundation of Shock and Vibration of Engineering Materials and Structures Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (No. 18kfgk01); Foundation of State Key Laboratory for Strength and Vibration of Mechanical Structures (No. SV2019-KF-32); Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. YWF-19-BJ-J-55).

References

[1] Zhu Y.W., Murali S., Cai W.W., Li X.S., Suk J.W., Potts J.R., Ruoff R.S., Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications, Adv. Mater., 2010, 22, 3906-3924.10.1002/adma.201001068Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Das S., Ghosh C.K., Sarkar C.K., Roy S., Facile synthesis of multilayer graphene by electrochemical exfoliation using organic solvent, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018, 7, 497-508.10.1515/ntrev-2018-0094Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Chen W.F., Lv G., Hu W.M., Li D.J., Chen S.N., Dai Z.X., Synthesis and applications of graphene quantum dots: a review, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018, 7, 157-185.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0199Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Syama S., Mohanan P.V., Comprehensive Application of Graphene: Emphasis on Biomedical Concerns, Nano-Micro Lett.,2019, 11, 1-31.10.1007/s40820-019-0237-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Jiao Z.P., Zhang B., Li C.Y., Kuang W.C., Zhang J.X., Xiong Y.Q., Tan S.Z., Cai X., Huang L.H., Carboxymethyl cellulose-grafted graphene oxide for efficient antitumor drug delivery, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018, 7, 291-301.10.1515/ntrev-2018-0029Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Jiang J.H., Pi J., Jin H., Cai J.Y., Functional graphene oxide as cancer-targeted drug delivery system to selectively induce oesophageal cancer cell apoptosis, Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol., 2018, 46, S297-S307.10.1080/21691401.2018.1492418Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Park C.M., Kim Y.M., Kim K.,Wang D.J., Su C.M., Yoon Y., Potential utility of graphene-based nano spinel ferrites as adsorbent and photocatalyst for removing organic/inorganic contaminants from aqueous solutions: A mini review, Chemosphere, 2019, 221, 392-402.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.01.063Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Zhang Y., Japip S., Chung T., Thermally evolved and boron bridged graphene oxide (GO) frameworks constructed on microporous hollow fiber substrates for water and organic matters separation, Carbon, 2017, 123, 193-204.10.1016/j.carbon.2017.07.054Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Zhuang Y., Wang X.C., Liu Q.Z., Shi B.Y, N-doped FeOOH/RGO hydrogels with a dual-reaction-center for enhanced catalytic removal of organic pollutants, Chem. Eng. J., 2020, 379, 1-10.10.1016/j.cej.2019.122310Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Pedrosa M., Sampaio M.J., Horvat T., Nunes O.C., Dražić G., Rodrigues A.E., Figueiredo J.L., Silva C.G., Silva A.M.T., Faria J.L., Visible-light-induced self-cleaning functional fabrics using graphene oxide/carbon nitride materials, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2019, 497, 1-9.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.143757Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Cao M.S., Wang X.X., Cao W.Q., Yuan J., Ultrathin graphene: electrical properties and highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding, J. Mater. Chem. C, 2015, 3, 6589-6599.10.1039/C5TC01354BSuche in Google Scholar

[12] Wan Y.J., Zhu P.L., Yu S.H., Sun R., Wong C.P., LiaoW.H., Ultralight, super-elastic and volume-preserving cellulose fiber/graphene aerogel for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding, Carbon, 2017, 115, 629-639.10.1016/j.carbon.2017.01.054Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Cinti S., Arduini F., Graphene-based screen-printed electrochemical (bio)sensors and their applications: Efforts and criticisms, Biosens. Bioelectron., 2017, 89, 107-122.10.1016/j.bios.2016.07.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Fu Y.F., Li Y.Q., Liu Y.F., Huang P., Hu N., Fu S.Y., High-Performance Structural Flexible Strain Sensors Based on Graphene-Coated Glass Fabric/Silicone Composite, ACS Appl. Mater. Inter., 2018, 10, 35503-35509.10.1021/acsami.8b09424Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Farooqui U.R., Ahmad A.L., Hamid N.A., Graphene oxide: A promising membrane material for fuel cells, Renew. Sust. Energy Rev., 2018, 82, 714-733.10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.081Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Zhang R., Palumbo A., Kim J.C., Ding J., Yang E.H., Flexible Graphene-, Graphene-Oxide-, and Carbon-Nanotube-Based Supercapacitors and Batteries, Ann. Phys. Berlin, 2019, 531, 1-18.10.1002/andp.201800507Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Shahzad F., Zaidi S.A., Koo C.M., Synthesis of Multifunctional Electrically Tunable Fluorine-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide at Low Temperatures, ACS Appl. Mater. Inter., 2017, 9, 24179-24189.10.1021/acsami.7b05021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Wan H., Gan Y., Sun J.D., Liang T., Zhou S.Q., Wang P., High sensitive reduced graphene oxide-based room temperature ionic liquid electrochemical gas sensor with carbon-gold nanocomposites amplification, Sens. Actuators B Chem., 2019, 299, 1-9.10.1016/j.snb.2019.126952Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Zhang B.W., Jiao Y., Chao D.L., Ye C., Wang Y.X., Davey K., Liu H.K., Dou S.X., Qiao S.Z., Targeted Synergy between Adjacent Co Atoms on Graphene Oxide as an Efficient New Electrocatalyst for Li-CO2 Batteries, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2019, 29, 1-7.10.1002/adfm.201904206Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Zhu J.C., Zhang K., Liu K.F., Shi X.M., Performance of hot and warm mix asphalt mixtures enhanced by nano-sized graphene oxide, Constr. Build. Mater., 2019, 217, 273-282.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.054Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Lin M., Wang Z.L., Yang P.W., Li P., Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt, Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 227-235.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0021Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Kong H.X., Hybrids of carbon nanotubes and graphene/graphene oxide, Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci., 2013, 17, 31-37.10.1016/j.cossms.2012.12.002Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Tian M.W., Hu X.L., Qu L.J., Du M.Z., Zhu S.F., Sun Y.N., Han G.T., Ultraviolet protection cotton fabric achieved via layer-by-layer self-assembly of graphene oxide and chitosan, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2016, 377, 141-148.10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.03.183Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Zhang X.Q., Fan X.Y., Yan C., Li H.Z., Zhu Y.D., Li X.T., Yu L.P., Interfacial Microstructure and Properties of Carbon Fiber Composites Modified with Graphene Oxide, ACS Appl. Mater. Inter., 2012, 4, 1543-1552.10.1021/am201757vSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Luo W., Zhang B., Zou H.W., Liang M., Chen Y., Enhanced interfacial adhesion between polypropylene and carbon fiber by graphene oxide/polyethyleneimine coating, J. Ind. Eng. Chem., 2017, 51, 129-139.10.1016/j.jiec.2017.02.024Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Luo Y.C., Cheng X.T., Zhang X.Q., Lei C.H., Fabrication of a three-dimensional reinforcement via grafting epoxy functionalized graphene oxide onto carbon fibers, Mater. Lett., 2017, 209, 463-466.10.1016/j.matlet.2017.08.049Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Yao X.M., Gao X.Y., Jiang J.J., Xu C.M., Deng C.,Wang J.B., Comparison of carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide coated carbon fiber for improving the interfacial properties of carbon fiber/epoxy composites, Compos. Part B Eng., 2018, 132, 170-177.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.09.012Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Zhang G.Y., Wang D., Xiao Y., Dai J.M., Zhang W., Zhang Y., Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonw oven fabric based on aminoterminated hyperbranched polymer, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2019, 8, 100-106.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0009Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Chun H., Kim H., Byun J., Effects of through-the-thickness stitches on the elastic behavior of multi-axial warp knit fabric composites, Compos. Struct., 2006, 74, 484-494.10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Sun B.Z., Hu H., Gu B.H., Compressive behavior of multi-axial multi-layer warp knitted (MMWK) fabric composite at various strain rates, Compos. Struct., 2007, 78, 84-90.10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.08.011Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Sugie T., Nakai A., Hamada H., Effect of CF/GF fibre hybrid on impact properties of multi-axial warp knitted fabric composite materials, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manufact., 2009, 40, 1982-1990.10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.08.005Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Luo Y.X., Hu H., Mechanical properties of PVC coated bi-axial warp knitted fabric with and without initial cracks under multiaxial tensile loads, Compos. Struct., 2009, 89, 536-542.10.1016/j.compstruct.2008.11.007Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Li D.S., Chen H.R., Ge D.Y., Jiang N., Jiang L., Split Hopkinson pressure bar testing of 3D multi-axial warp knitted carbon/epoxy composites, Compos. Part B Eng., 2015, 79, 692-705.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.04.045Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Li D.S., Duan H.W., Jiang N., Jiang L., Mechanical response and failure of 3D MWK carbon/epoxy composites at cryogenic temperature, Fiber. Polym., 2015, 16, 1349-1361.10.1007/s12221-015-1349-2Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Li D.S., Jiang N., Jiang L., Ge T.Q., Experimental study on the bending properties and failure mechanism of 3D MWK composites at elevated temperatures, Fiber. Polym., 2015, 16, 2034-2045.10.1007/s12221-015-5331-9Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Ma P., Nie X.L., Interface improvement of multi axial warp-knitted layer composite with short glass fiber, Fiber. Polym., 2017, 18, 1413-1419.10.1007/s12221-017-7091-1Suche in Google Scholar

[37] China Aviation Industry Corporation. Test Method for Compression of Metals at High Temperature; HB 7571-1997; China Aviation Industry Corporation: Beijing, China, 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Deng X., Chawla N., Three-dimensional (3D) modeling of the thermoelastic behavior of woven glass fiber-reinforced resin matrix composites, J. Mater. Sci., 2008, 43, 6468-6472.10.1007/s10853-008-2982-6Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Zhai J.J., Cheng S., Zeng T., Wang Z.H., Jiang L.L., Thermomechanical behavior analysis of 3D braided composites by multiscale finite element method, Compos. Struct., 2017, 176, 664-672.10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.05.064Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Su Y.J., Wei H., Gao R.G., Yang Z., Zhang J., Zhong Z.H., Zhang Y.F., Exceptional negative thermal expansion and viscoelastic properties of graphene oxide paper, Carbon, 2012, 50, 2804-2809.10.1016/j.carbon.2012.02.045Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Zhang H.P., Han W., Tavakoli J., Zhang Y.P., Lin X.Y., Lu X., Ma Y., Tang Y.H., Understanding interfacial interactions of polydopamine and glass fiber and their enhancement mechanisms in epoxy-based laminates, Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manufact., 2019, 116, 62-71.10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.10.024Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Kalavakunda V., Hosmane N.S., Graphene and Its Analogues, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2016, 5, 369-376.10.1515/ntrev-2015-0068Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Sun T., Li M.X., Zhou S.T., Liang M., Chen Y., Zou H.W, Multi-scale structure construction of carbon fiber surface by electrophoretic deposition and electropolymerization to enhance the interfacial strength of epoxy resin composites, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2020, 499, 1-12.10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.143929Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Yang Y.M., Xian G.J., Li H., Sui L.L., Thermal aging of an anhydride-cured epoxy resin, Polym. Degrad. Stabil., 2015, 118, 111-119.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.04.017Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 H.-M. Zuo et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview