Abstract

Polymer-based nanoparticles have good solubility, stability, safety, and sustained release,which increases the absorption of loaded drugs, protects the drugs from degradation, and prolongs their circulation time and targeted delivery. Generally, we believe that prevention and control of infectious diseases through inoculation is the most efficient measure. However, these vaccines including live attenuated vaccines, inactivated vaccines, protein subunit vaccines, recombinant subunit vaccines, synthetic peptide vaccines and DNA vaccines have several defects, such as immune tolerance, poor immunogenicity, low expression level and induction of respiration pathological changes. All kinds of biodegradable natural and synthetic polymers play major roles in the vaccine delivery system to control the release of antigens for an extended period of time. In addition, these polymers also serve as adjuvants to enhance the immunogenicity of vaccine. This review mainly introduces natural and synthetic polymer-based nanoparticles and their formulation and properties. Moreover, polymer-based nanoparticles as adjuvants and delivery carriers in the applications of vaccine are also discussed. This review provides the basis for further operation of nano vaccines by utilizing the polymer-based nanoparticles as vaccine adjuvants and delivery systems. Polymer-based nanoparticles have exhibited great potential in improving the immunogenicity of antigens and the development of nano vaccines in future.

1 Introduction

Vaccines are biological preparations that can afford actively acquired immunity for a peculiar illness. Vaccines can prevent the effects of infection of many pathogens. There are several types of vaccines in development and in use, including attenuated vaccine, inactivated vaccine, toxoid vaccine, protein subunit vaccine, DNA vaccine, live attenuated vaccine, and vector vaccine [1, 2, 3, 4]. However, these traditional vaccines are susceptible to degradation, have a short duration of action, and present serious side effects and inflammatory reactions at the injection site during vaccination. Furthermore, developing countries are lagging behind in vaccine research, making it extremely difficult and challenging for multi-dose conventional vaccines to activate the required immune response in these developing countries [5]. Some diseases caused by intracellular pathogens don’t have the effective prevention or therapeutic vaccines. These diseases are required vaccine formulations that not only promote strong cellular or Th1-based immune responses, but also induce humoral or Th2 immune responses and mucosal immune responses [6]. Therefore, to enhance the vaccines immune efficacy and achieve sustained release and mucosal immunity, several strategies was carried out: utilizing an efficient adjuvant, implementing an efficient delivery system, and using appropriate effective antigen presentation targets [7, 8, 9, 10].

Alum compounds adjuvants and Freund’s adjuvants are traditionally used as vaccine carriers and adjuvants. However, paraffin oil present in Freund’s adjuvant is non-degradable

and causes toxicity problems, and the injection of alum compounds adjuvant produces a local inflammatory response [5, 11]. Compared to traditional adjuvants, polymer-based nanoparticles are non-toxic, safe, and biodegradable. Although there have been many experiments in which polymer nanoparticle adjuvants were validated using animal models, there is still a lack of clinical trials and lack of convincing treatment for human diseases. We should further research and continue to conduct clinical trials. In recent decades, innovations in the design and development of novel biomaterials for biomedical applications have shown that polymers have high physiochemical properties, biocompatibilities, and biodegradability. Their application as vaccine adjuvants and delivery carriers may be a useful alternative to conventional bacterial adjuvants and virus vectors [5]. This review mainly introduces natural and synthetic polymer-based nanoparticles, the formulation and properties of these nanoparticles, and the applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in the vaccine field.

2 Polymer-based nanoparticles

Polymer-based nanoparticles are valuable in the treatment and prevention infectious diseases, because their small particle size enables them to cross the biological barrier when administered parenterally. They are also able to improve cellular uptake [12]. Polymeric nanoparticles also provide a sustained release system and improve the stability of labile drugs from in vivo enzymatic degradation [13]. Presently, a variety of natural and synthetic biodegradable polymer-based nanoparticles can be used to enhance immunogenicity for vaccine delivery. In addition, vaccine antigens encapsulated in the polymer-based nanoparticles administered through the mucosal pathway can protect antigens from degradation and ensure that the encapsulated antigen is released at the action site to stimulate efficient immune responses [14]. Polymer-based nanoparticles have also exhibited great value and potential in improving the immunogenicity of vaccines and the development of nano vaccines.However, in order to achieve higher productivity and desired morphology, further research is needed on the clear mechanism of nanoparticle synthesis. For future therapeutic applications, it would be highly desirable to expand nanoparticle production [15].

2.1 Natural and synthetic polymer-based nanoparticles

Natural polymers such as chitosan, dextran, hyaluronic acid, β-cyclodextrin, alginate, and gelatin pullulan have been explored for preparation nanovaccines. Some natural and synthetic polymers used in vaccination can be seen in Table 1. Chitosan-based nanoparticles have been widely applied in vaccines due to their biodegradability, biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and easy modification in terms of shape and size [16, 17, 18]. Synthetic polymers mainly include chitosan derivatives, poly(lactic acid-glycolic acid) (PLGA), poly(ϵ-caprolactone) (PCL), den-drimers, poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(alkyl cyanoacrylates), polyanhydride, poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) ,and so on. Some chitosan derivatives, such as O-2’-hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (O-2′-HACC), N-2-hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (N-2-HACC), and N-2-hydroxypropyl dimethylethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (N-2-HFCC), have been synthesized and applied in animal vaccines in our previous studies [19, 20, 21]. Due to the introduction of epoxypropyl dimethylethyl ammonium chloride (EEA) on its -NH2 group, these chitosan derivatives have higher water solubility compared to chitosan. Because of their biocompatibility, low virulence, high biodegradability, and controlled and sustained release mode of PLGA and PLA, they are major synthetic polymers for mucosal delivery of antigens [22, 23, 24].

The essential information of some natural and synthetic polymers used in vaccination as adjuvants and delivery system

| Materials | Name | Advantages | Disadvantages | Polymers can loaded | Preparation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural polymers | Chitosan | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, easily modified, low allergenicity | Lower immunogenicity | Protein, DNA, RNA, peptides | Emulsification, nanoprecipitation, solvent evaporation, ionic gelation |

| Pullulan | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity | Lower immunogenicity | Protein, DNA, RNA, peptides | Solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation | |

| Alginate | Biodegradability | Lower immunogenicity, soluble in high pH, insoluble in low pH | Protein, peptides | Emulsification, ionic gelation | |

| Lentinan | Enhanced antigen presentation | Lower immunogenicity | Protein, peptides | Emulsification | |

| Inulin | Well tolerated by the body and cause minimal reactogenicity | Noimmunological activity insolubleform, not able to stimulateDC maturation in vitro | Protein | Emulsification, ionic gelation | |

| Mannan | Enhanced phagocytosis ofantigen | Lower immunogenicity | Protein | Ionic gelation | |

| Albumin | Enhanced antigen presentation | Lower immunogenicity | Protein | Solvent evaporation, emulsification, ionic gelation | |

| Heparin | Biocompatible, biodegradable | Lower immunogenicity | Protein | Solvent evaporation | |

| Synthetic polymers | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity | Low drug loading | Protein, peptides, DNA | Solvent evaporation, emulsification diffusion, nanoprecipitation, salting-out |

| Poly(D,L-lactide-co- glycolide) (PLG) | Biocompatibility, biodegradability | Use of organic solvents, not very stable, and often not effective for mucosaladministration | Protein, peptides | Solvent evaporation, emulsification diffusion, nanoprecipitation, salting-out | |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Flexibility | Exhibit poor drug loading | Protein, peptides | Solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation | |

| Polyphosphazenes | Film-forming nature, biodegradable | Not very stable | Protein, peptides | Solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation | |

| Polyelectrolytes | Self-assembled, water-soluble, non-toxic | Low drug loading | Protein | Emulsification diffusion | |

| Polyanhydrides | Biodegradable, non-toxic | Exhibit poor drug loading | Protein, peptides | Emulsification diffusion | |

| Polymethacrylates | Enhance immune responses | Exhibit poor drug loading | Protein, peptides, DNA | Emulsion polymerization | |

| Poly(ϵ-caprolactone) (PCL) | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity | Lack of intrinsic immunogenicity | Protein, peptides | Nanoprecipitation | |

| Poly(D, L -lactide) (PLA) | Biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity | Low drug loading | Protein, peptides, DNA | Solvent evaporation, nanoprecipitation, salting out | |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | Intrinsicimmunostimulatory property | Low transfection efficiency of APCs in vivo | Protein, peptides, DNA | Emulsification diffusion | |

2.2 Formulation of polymer-based nanoparticles

Numerous techniques are available for the formulation of polymer-based nanoparticles. Commonly used techniques including solvent evaporation, emulsification-solvent diffusion, nanoprecipitation, etc [25]. The different preparation methods were discussed, and the advantages and disadvantages of formulation methods are shown in Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of formulation of polymer-based nanoparticles

| Formulation methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Emulsification- solvent diffusion | High encapsulation efficiency, no need for homogenization, high batch-to-batch reproducibility, ease of scale-up, simplicity, narrow size distribution | High volumes of water to be eliminated from the suspension, leakage of water-soluble drug into the saturated-aqueous external phase during emulsification |

| Salting out | Minimizes stress to protein encapsulants | Exclusive application to lipophilic drugs, extensive nanoparticles washing steps |

| Dialysis | Simplicity and common | Not an efficient means to encapsulate water soluble drugs |

| Solvent evaporation | Simplicity, versatile | Mainly applied to liposoluble drugs, having possibility of coalescence of nanoparticles during evaporation |

| Nanoprecipitation | Simplicity, quickness and reproducibility | Need to find a suitable drug/ polymer/solvent/non-solvent system, poor encapsulatio nefficacy of hydrophilic drugs |

| Supercritical fluid | Easy and reproducible scaleup, good control of structural homogeneity Production of high purity nanomedicines | Most polymers exhibit poor solubility or even non-solubility |

| Ionotropic gelation | Simple in practice | More complex to optimize |

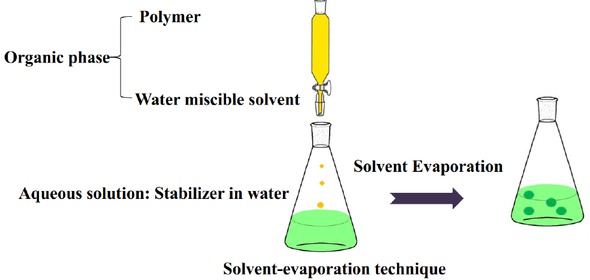

Solvent evaporation methods for the preparation of polymer-based nanoparticles can be seen in Figure 1. Polymer solution is prepared in a volatile solvent and an emulsion is formulated. The emulsion is converted to suspension as it evaporates the solvent of the polymer, allowing it to diffuse through continuous phase of the emulsion [25]. The single emulsion method isO/W that prepares the emulsion oil (O) in water (W) by adding water and a surfactant to the polymer solution [26]. The double emulsion method is also known as the W/O/W method [27]. The method utilizes high speed homogenization or sonication, and then evaporate the solvent by continuous magnetic stirring at

Schematic representation of the solvent-evaporation technique for the production of nanoparticles

room temperature or under reduced pressure [25]. After the solvent evaporates, the solidified nanoparticles can be washed and collected by centrifugation and lyophilized for long-term storage [28]. The method can be be easily performed in the laboratory, but it is only suitable for liposoluble drugs,which takes time and requires too much energy during homogenization [29].

Emulsification-solvent diffusion method (seen in Figure 2) is a technique to transform the salting out process [27]. A conventional O/W emulsion is formed between a partially water-miscible solvent that contains a polymer, a drug and an aqueous solution containing a surfactant. The polymer solvent and water are saturated with each other at room temperature and afterwards diluted with a large amount of water to induce the diffusion of the solvent from dispersed droplets into the external phase. This results in the formation of particles [30]. The advantages of this method include enhanced encapsulation efficiency, easy enlargement, narrow size distribution, and simplicity [27]. However, the disadvantage is that a large amount of water and water-soluble drugs are removed from the suspension during the emulsification process and leak into the outer phase of the saturated aqueous phase, thereby reducing the encapsulation efficiency [31].

Schematic representation of the emulsification-solvent diffusion method for the preparation of nanoparticles

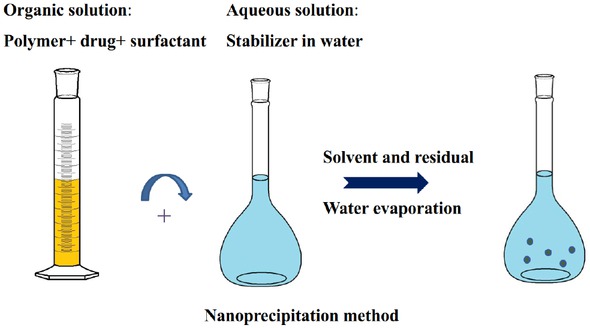

Nanoprecipitation is also called solvent displacement method (seen in Figure 3) [25]. The organic phase is formed by dissolving the polymer and drug in a polar solvent. The solution is then added dropwise to an aqueous solution containing emulsifier or surfactant and rapid diffusion of solvent occurs, resulting in the formation of nanoparticles [27, 32, 33].

Schematic representation of the nanoprecipitation method for the preparation of nanoparticles

The salting out method relies on the emulsification of the organic phase (polymer solution in acetone) into an aqueous phase by adding a high concentration of salts (electrolytes) (magnesium chloride, calcium chloride and magnesium acetate) or sucrose (non-electrolyte).However, in this technique it is necessary to wash the nanoparticles in large quantities [34]. The advantages and disadvantages of nanoprecipitation and salting out method are shown in Table 2 [28, 33].

Dialysis provides a simple and effective method for preparing small, narrowly distributed polymer-based nanoparticles. Dialysis is performed on a miscible non-solvent [35]. The basic prerequisites are the miscibility of the solvent and the presence of the diluted polymer solution. Displacement of the solvent within the membrane results in a gradual reduction of the mixture’s ability to dis-solve the polymer [28]. Based on the use of physical barriers, in particular dialysis membranes or common semipermeable membranes, the passive transport of solvents is able to slow the mixing of polymer solutions with non-solvents. The dialysis membrane contains polymer solutions [25].

The characteristics of the supercritical fluid method are that it has very fast mass transfer, near zero surface tension, and effective solvent elimination. This permits innovative processing applications that can overcome the classic limitations of liquid-based processes [36]. The principles of the nanoparticles preparation, including rapid expansion of supercritical solution (RESS) and rapid expansion of supercritical solution into liquid solvent (RESOLV) in the supercritical fluid method, have been developed [25]. RESS has been used for the micronization of compounds that exhibit good solubility in supercritical CO2. It is particularly attractive because it does not contain organic solvents. However, it is only suitable for substances that are soluble in supercritical CO2 small molecules and compounds containing a few polar bonds, which are only a small quantity of those of biomedical interest [37]. To minimize coalescence and have better control over particle size distribution, significant improvements in RESS using liquid solvents or solutions at the receiving end of the supercritical solution expansion have been proposed, under the name RESOLV. When the receiving solution is water, nanoparticles produced in this manner can prevent aggregation by the presence of a polymer or another protective agent in the receiving solution [36, 38].

Ionotropic gelation involves the spontaneous aggregation of natural polymers with multivalent counterions, the most common being sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP). The process begins by dissolving the polymers in a dilute acidic solution which is further diluted with water. TPP was then added while constantly stirring, resulting in the formation of nanoparticles [39]. Upon mixing the two phases, Nanoparticles are formed immediately through intermolecular and intramolecular ligation between the TPP phosphate and the amino group of the chitosan [40].

2.3 Physiochemical properties of polymer-based nanoparticles

Chitosan is easy to combine with DNA to form polyelectrolyte complex, which makes DNA a highly resistant to nuclease degradation. The chitosan backbone is abundant in hydroxyl and amino groups, making it easy to chemically modify and increase its targeting [41, 42]. PLGA is the commonly used polymer in vaccines [26]. PLGA nanoparticles are internalized in cells by fluid phase pinocytosis and by clathrin-mediated endocytosis [43]. Low molecular weight polymers with higher glycolide content have shorter degradation times due to their hydrophilicity and amorphous nature [44]. PEG has been used to coat PLA nanoparticles, and it usually aggrandizes the solubility of nanoparticles, decreasing their aggregation and interaction with proteins in physiological fluids. This produces spatial stability on the surface of the gene carrier to enhance transfer efficiency [45]. Compared to the bulk materials and microparticles, nanoparticles exhibit different mechanical properties. Moreover, whether the nanoparticles will fall into the surface or become distorted under immense pressure is controlled by the comparison of the stiffness between nanoparticles and the contacting exterior surface [46], which may reveal the performance of nanoparticles. Understanding the mechanical characteristics of nanoparticles and their interactions with different types of surface is essential to improve surface quality and material removal [47].

2.4 Proteins encapsulated into polymer-based nanoparticle

Protein administration alone represents a real challenge because the oral bioavailability is limited by the gastrointestinal tract epithelial barrier. The digestive enzymes are susceptible to gastrointestinal degradation as they have short half-life in the body—in fact, most of them can’t diffuse across some biological barriers [48]. Encapsulation therapeutic proteins in polymer-based nanoparticles are prospective alternatives to break through these shortcomings. To prevent hydrolysis and enzymatic degradation in the body, proteins can be incorporated into a polymer matrix,which helps them maintain their activity and integrity. Sometimes it can target therapeutic proteins to target site and increase their bio-availability [49]. For drug delivery, disparate proteins and peptides are encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles. Water-soluble chitosan-alginate carriers are made from spherical nanoparticles in order to overcome enzymatic and absorption barriers to orally administered BSA [50]. One method of encapsulating hesperidins is to utilize chitosan nanoparticles to stabilize oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion with lecithin as a low cost food grade surfactant [51]. Lately studied insulin loaded PLGA nanoparticles for keeping insulin integrality during preparation and delivery. Using these solvent evaporation techniques to prepare nanoparticles, a higher entrapment efficiency can be observed at the target load. The yields of nanoparticles prepared by different methods differ significantly [52]. Solving the problem of targeting and bioavailability of peptidic drugs such as desmopressin, the encapsulation into nanoparticles has become standard in pharmaceutics [53].

2.5 Nucleic acids encapsulated into polymer-based nanoparticles

Due to their size and negative charge, nucleic acids are weak and have undesirable inherent transfection consequence. Nucleic acids can be embedded in a polymer matrix and electrostatic adsorption on the surface of nanoparticles by a suitable surfactant or the addition of a cationic polymer to the matrix [54, 55]. Chitosan can concentrate and encapsulate plasmid DNA to form nanoparticle complexes that can adhere to intestinal epithelial cells, transport through M-cells across mucosal boundaries, and transfect epithelial cells and/or immune cells in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue [56, 57]. Our group developed the plasmid DNA of NDV F gene encapsulated in the N-2-HACC/CMCS nanoparticles, and found that intranasally immunized chickens with the nanoparticles produced higher anti-NDV IgG and sIgA antibody than the chickens in other groups did. They also had significantly stimulated lymphocyte proliferation and higher levels of induced IL-2, IL-4 and IFN-𝛾 levels, which demonstrated that the nanoparticles could serve as efficient DNA delivery systems and vaccine adjuvants for stimulating humoral, cellular, and mucosal immune [58].

3 Application of polymer-based nanoparticles

3.1 Natural polymer-based nanoparticles

3.1.1 Chitosan-based nanoparticles

Chitosan is especially suitable for nasal delivery [59]. Chitosan nanoparticles have mucoadhesive properties that prevent rapid nasal clearance and therefore increases the antigen retention time in the nasal mucosa. This may prolong the contact time between nose-associated lymphoid tissue and formulation due to a reduction in mucociliary clearance. Standard nasal residence time for dosing solution can be increased by a factor of four due to use of adherent adhesive chitosan particles [60]. Chitosan-based nanoparticles have been widely used in vaccine development—examples include vaccines against Clostridium botulinum type A neurotoxins, Neospora, hepatitis B virus, and Newcastle disease [16].

Chickens inoculated with inactivated avian influenza virus (AIV)-chitosan-nanoparticles showed the highest haemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titer weeks after the inoculation phagocytic activity, and phagocytic index in the AIV-chitosan nanoparticles group significantly increased [61]. To prevent bronchitis caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), chitosan-DNA nanospheres administered intranasally induced the expression of corresponding protein, and improved the levels of anti-RSV-specific IgG, sIgA, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, and IFN-𝛾 [62]. The chitosan-DNA nanoparticleswere effective against diseases of the T. pyogenes infection and provided strategies for further development of novel vaccines encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles [63].

3.1.2 Alginate

Sodium alginate nanoparticles are natural polymers made of sugar monomers that significantly increase the bioavailability of encapsulated drugs. Due to its anionic nature, alginate is known for its mucoadhesive properties, which allow them to alternatively stick on mucosal membranes. This is profitable for the development of drug delivery systems for using transmucosal. In addition, studies show that alginate-based substances are sensitive to pH and may be useful to “mechanically” control the releasing mechanisms that encapsulate biomolecules from alginate drug delivery vehicles [64]. Studies have demonstrated that antigen adsorption to chitosan particles, and coated with sodium alginate, that sodium alginate-coated chitosan nanoparticle carrier can inhibit rupture release of ovalbumin originally in artificial gastric acid (pH 1.2). In addition, the cytotoxicity test results of chitosan and sodium alginate polymer nanoparticles showed that cell viability was close to 100% [65].

3.1.3 Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA), also known as hyaluronan, is a natural bioadhesive polymer. HA is a mucopolysaccharide make up of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine residues discovered in vertebrates, connective tissues, synovial fluid, and extracellular tissue matrix in the eye [66]. Vaccine delivery systems based on bioadhesive hyaluronic acid produce a substantial immune response against LKT63 influenza antigens following intranasal administration [67]. Combining trimethyl chitosan with HA to form a more stable and robust nanoparticle to contain antigen increased IgG antibody compared to both unconjugated nanoparticles and free antigen [68].

3.1.4 Pullulan

Pullulan is composed of a peculiar connection of α (1→ 4) glycosidic bonds and α (1→ 6) connected maltotriose residues and natural non-ionic water-soluble linear polysaccharide. Because it has special properties including non-toxicity, non-mutagenicity, non-immunogenicity, and non-carcinogenicity, pullulan-based nanoparticles have significant research value in creating excellent vaccine transmit systems [69]. More recently, a pullulan nanogel-based PspA nasal administration delivery system based on cationic cholesteryl groups was exploited. The experiment was aimed at Streptococcus pneumoniae Xen10 bacteria and tested for efficacy in a mouse pneumococcal airway infection model. The results showed that nasal and bronchial secretions have higher PspA-specific serum IgG and IgA antibodies [70].

3.1.5 Inulin

Inulin is a complex polymeric carbohydrate (polysaccharide) that is natural and hydrophilic. It is an inexpensive dietary fiber compound that is a linear natural plant-derived polysaccharide and is linked by a fructose unit chain and linked by glycosidic bonds [71, 72]. Recently, inulin has been characterized as a more potent adjuvant as it enhances humoral and cellular immune responses when administered with antigens [73]. Studies have shown that high molecular weight inulin nanoparticles can be used as novel drug delivery systems or other molecules of interest [74]. Zhang et al. prepared methylprednisolone loaded ibuprofen modified inulin based nanoparticles have no significant cytotoxic effects under all conditions of use and have great potential for the treatment of synergistic effects of spinal cord injury [75].

3.1.6 Dextran

Dextran is a highly biocompatible and biodegradable neutral bacterial exopolysaccharide with a simple repeating glucose subunit. Its simple and unique biopolymer properties make it ideal for nanomedicine, nanomedicine carriers, and cell imaging systems or nanobiosensors. Most importantly, it is very soluble in water and does not show cytotoxicity after drug delivery [76]. Prepare various dextran coated nanoparticles and optimize for drug delivery and targeting [50]. Studies have shown that the high negative zeta potential of Zidovudine-stearic acid/Dextran nanoparticles (AZT-SA/Dex Nps) exhibits higher stability, better zidovudine controlled release, and more efficient cellular uptake [77]. Dextran and albumin-derived iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles have improved stability, biocompatibility, and blood circulation time [50].

3.2 Synthetic polymer-based nanoparticles

3.2.1 Polypeptides

Poly-L-lysine (PLL), poly(𝛾-glutamic acids) (𝛾-PGA), and polyaspartamide P[Asp(DET)] are all polypeptides. Concentrated of plasmids encoding chicken ovalbumin (OVA)with PLL peridiumed polystyrene nanoparticles. The acquired compounds can stimulate higher levels of OVA-specific antibodies and CD8+ T cells in mice and significantly inhibit tumor increase following attack with the OVA expressing EG7 tumor cells [78]. The carrier system based on a mixture of a homopolymer of a DNA polymer with a cationic polyaspartamide P[Asp(DET)] and block copolymer PEG-b-P [Asp(DET)] are presentated [79]. Optimization of homopolymers and block copolymers for DNA complexes, against non-specific eliminate stability and cells transfection efficient. The complexes are concluding DNA encoding tumor antigen SART3, CD40 and GM-CSF, are immunity intraperitoneally and by inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis to extend the life span of animals carrying CT26 colon cancer [80].

3.2.2 PLGA

PLGA-PEG nanoparticles has been prepared to encapsulate amphotericin B to improve its solubility and to target the macrophages of tissues infected with visceral leishmaniasis—the nanoparticles exhibited higher efficacy compared to free amphotericin B [81]. Pigs vaccinated with the PLGA-nanoparticles peptide did not contract fever and influenza symptoms, and swine influenza viruses (SwIV) were not detected in bronchoalveolar lavage [82]. Tetanus toxoid (TT) has been extensively studied for the controlled release from TT-PLGA microspheres [83]. PLGA/PLA-based nanoparticles are capable of delivering encapsulated antigens to antigen presenting cells in controlled and sustained means [84, 85]. Studies have shown that PEG strengthens the PLA nanoparticles in gastrointestinal (GI) fluid stability and promotes the transmit of nanoparticles to the lymphatic system through the GI mucosa [86]. Mice immunized by PLGA nanoparticles encapsulating the bivalent H1 antigen showed significant effects against tuberculosis, as the immunization provides longterm protection [87]. The limitations of PLGA nanoparticles can be overcome through extensive and comprehensive assessments of pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and toxicity [27].

3.2.3 PCL

PCL is a semi-crystalline, biodegradable, hydrophobic, biocompatible, and inexpensive polymer. Due to in vitro stability, hydrophobicity, and slow degradation pattern, PCL-based nanoparticles have the potential to be candidates for mucosal antigen delivery and DNA delivery in the future [88]. Mucoadhesive chitosan-PCL nanoparticles also have potential to combat H1N1 as a carrier for nasal vaccinations. Compared to other antigenic preparations, chitosan-coated PCL nanoparticles cause considerable cell and humoral immune responses [89]. Different amounts of antigen were adsorbed into the nanoparticles in fixed amounts, and these different doses induced the same humoral and mucosal antibodies in the nasal secretion of mice [90]. Methoxy polyethylene glycol-polycaprolactone is an ecotropic diblock copolymer for the delivery of hydrophobic drugs [91]. The quercetin-biapigenin mixture is encapsulated in PCL-loaded nanoparticles and has synergistic antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects [92].

3.2.4 Polyanhydride

Polyanhydride is a polymer formed by the polymerization of carboxylic acids, and its monomers are formed by anhydride linkage. Polyanhydride has good water instability, biodegradability, and safety [93, 94]. Various polyanhydrides have been reported containing 1,6-bis (p-carboxyphenoxy) hexane (CPH), sebacic anhydride, and 1,8- bis (p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane (CPTEG), peculiar combinations of CPH and CPTEG copolymer microparticles have been serve as antigens. The particles are validly phagocytosed through antigen-presenting cells and located in phagosomes. The amphiphilic polyanhydride nanoparticles can excite antigen-presenting cells that mimic pathogens [95].

3.2.5 Dendrimers

A dendrimers is a type of highly branched, symmetrical, and radial macromolecule similar to a dendrite. Dendrimers have many features, including a large number of branch points, three-dimensional and spherical with monodisperse, and fixed nanometer size range. The characteristic three dimensional structures of dendrimers enable them to pass through cell membranes; therefore, they are better nano delivery materials than the classical polymers [96]. Due to these unique properties, cationic den-drimers have been widely used for drug and gene delivery [97, 98, 99]. However, to date, there is no report regarding whether dendrimers can deliver a DNA vaccine in the field of veterinary vaccines.

3.2.6 Poly(lactic acid)

PLA has been widely used in biomedicine, and it is considered to be a good material for preparing micron and nanoparticles because the particle size and shape can be controlled to meet the preparation requirements [100]. Using PEG-PLA-PEG nanoparticles as a delivery carriers for oral immunization enhanced mucosal uptake results in an effective immune response that preserves the antigenicity of the encapsulated HBsAg [101]. Surfactant-free anionic PLA nanoparticles coated with HIV-1 p24 protein that induces Th1 responses were also confirmed in the macaque model; this protein delivery system demonstrates the potential of charged nanoparticles in the field of vaccine development [102].

3.3 Targeting of the immune system

Targeting nanoparticles to immune cells can enhance immune responses. CpG is a ligand of TLR9 expressed by immunizing cells. Using CpG to activate immune cells leads to an induction of various responses such as the generation of cytokines and chemokines that help to enhance the immune response [103]. Studies have shown that TLR ligands targeted to deliver to human and mouse DCs immensely increases adjuvantation. According to these studies, intracellular TLRs (TLR3 and TLR7/8) ligands were encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles and peridium with anti-DC-SIGN antibodies that recognize DC-specific receptors [104]. Hunsawong et al. found that a dengue virus serotype-2 nanovaccine induced robust humoral and cell-mediated immunity iin vaccinated mice [105]. In addition, mice immunized with amino-functionalized polymeric nanoparticles that accept human papillomavirus antigens exhibited an improved immune response compared to mice that received naive nanoparticles [106]. Nanoparticles are also used to target HIV-infected cells, and it has showed that the superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles have significant potential to improve cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) function and served as an adjunctive therapy in both the imaging and eradication of latently HIV-infected cells [107].

4 Future perspective

Polymer-based nanoparticles have great potential as adjuvants for delivery systems and vaccines [108]. In recent years, the main goal of developing polymer-based nanoparticles is to improve the efficacy of treatment while minimizing the development of drug resistance [109].However, there will be many challenges that come with the manipulation of size, shape, and other properties [110]. The local toxicity of polymer-based particle vaccines can be a detrimental problem that hinders their clinical application. Furthermore, the difficulty of synthesizing non-aggregated nanoparticles with consistent and ideal properties and considering how these properties affect their interactions with the biological system at all levels from cell through tissue and to whole body are still obstacles that we must work to overcome in the future. Ideally, the adjuvants or delivery vehicles we prepare will have the ability to stimulate humoral, cellular, and mucosal immune responses simultaneously or discretely. In the future, we can incorporate new attractive vaccine systems by incorporating some other attractive features such as sustained release, target and alternative delivery methods, and delivery routes [111, 112].

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the Heilongjiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Genetic Engineering and Biological Fermentation Engineering for Cold Region for carrying out this work. This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0500706), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570929 and 31771000), Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (C2017058), Cultivation Project of Scientific and Technological Achievements for Provincial Universities in Heilongjiang (TSTAU-C2018017), Special Project of Innovation Ability Enhancement of Science and Technology Institutions in Heilongjiang Province (YC2016D004) and Technological innovation talent of special funds for outstanding subject leaders in Harbin (2017RAXXJ001).

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

[1] Govindarajan D., Meschino S., Guan L., Clements D.E., Meulen J.T., Casimiro D.R., Coller B., Bett A.J., Preclinical development of a dengue tetravalent recombinant subunit vaccine: Immunogenicity and protective efficacy in nonhuman primates, Vaccine, 2015, 33, 4105-4116.10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.067Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Li J., Yu J., Xu S., Shi J., Xu S., Wu X., Fu F., Peng Z., Zhang L., Zheng S., Immunogenicity of porcine circovirus type 2 nucleic acid vaccine containing CpG motif for mice, Virol. J., 2016, 13, 1-7.10.1186/s12985-016-0597-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Sergeyev O., Barinsky I., Synthetic peptide vaccines, Vopr. Virusol., 2016, 61, 5-8.10.18821/0507-4088-2016-61-1-5-8Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Apte S.H., Stephenson R.J., Simerska P., Groves P., Aljohani S., Eskandari S., Toth I., Doolan D.L., Systematic evaluation of self-adjuvantinglipopeptidenano-vaccine platforms for the induction of potent CD8+ T cell responses, Nanomedicine, 2016, 11, 137-152.10.2217/nnm.15.184Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Shakya A.K., Nandakumar K.S., Applications of polymeric adjuvants in studying autoimmune responses and vaccination against infectious diseases, J. R. Soc. Interface., 2012, 10, 1-16.10.1098/rsif.2012.0536Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Vijaya B.J., Sean M.G., Aliasger K.S., Biodegradable particles as vaccine antigen delivery systems for stimulating cellular immune responses, Hum. Vacc. Immunother., 2013, 9, 2584-2590.10.4161/hv.26136Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Di G.S., Quattrocchi V., Zamorano P., Use of adjuvants to enhance the immune response induced by a DNA vaccine against Bovine herpesvirus-1, Viral. Immunol., 2015, 28, 343-346.10.1089/vim.2014.0113Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Liu F., Sun X.J., Fairman J., Lewis D.B., Katz J.M., Levine M., Tumpey T.M., Lu X.H., A cationic liposome-DNA complexes adjuvant (JVRS-100) enhances the immunogenicity and cross-protective efficacy of pre-pandemic influenza A (H5N1) vaccine in ferrets, Virology, 2016, 492, 197-203.10.1016/j.virol.2016.02.024Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Manoj S., Babiuk L.A., Approaches to enhance the efficacy of DNA vaccines, Critl. Rev. Cl. Lab. Sci., 2004, 41, 1-39.10.1080/10408360490269251Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Xu J.H., Dai W.J., Wang Z.M., Chen B., Li Z.M., Fan X.Y., Intranasal vaccination with chitosan-DNA nanoparticles expressing pneumococcal surface antigen a protects mice against nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumonia, Clin. Vaccine. Immunol., 2011, 18, 75-81.10.1128/CVI.00263-10Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Stills H.F., Bailey M.Q., The use of Freund’s complete adjuvant, Lab. Anim., 1991, 20, 25-30.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Torres M.P., Wilson-Welder J.H., Lopac S.K., Phanse Y., Carrillo-Conde B., Ramer-Tait A.E., Bellaire B.H., Wannemuehler M.J., Narasimhan B., Polyanhydride microparticles enhance dendritic cell antigen presentation and activation, Acta. Biomater., 2011, 7, 2857-2864.10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Abdelghany S., Parumasivam T., Pang A., Roediger B., Tang P., Jahn K., Britton W.J., Chan H., Alginate modified-PLGA nanoparticles entrapping amikacin and moxifloxacin as a novel host-directed therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol., 2019, 52, 642-651.10.1016/j.jddst.2019.05.025Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Zhao K., Li S.S., Li W., Yu L., Duan X.T., Han J.Y., Wang X., Jin Z., Quaternized chitosan nanoparticles loaded with the combined attenuated live vaccine against Newcastle disease and infectious bronchitis elicit immune response in chicken after intranasal administration, Drug. Deliv., 2017, 24, 1574-1586.10.1080/10717544.2017.1388450Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Fariq A., Khan T., Yasmin A., Microbial synthesis of nanoparticles and their potential applications in Biomedicine, J. Appl. Biomed., 2017, 15, 241-248.10.1016/j.jab.2017.03.004Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Chattopadhyay S., Chen J.Y., Chen H.W., Jack Hu C.M., Nanoparticle vaccines adopting virus-like features for enhanced immune potentiation, Nanotheranostics, 2017, 1, 244-260.10.7150/ntno.19796Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Bandeira A.C., de Oliveira Matos A., Evangelista B.S., da Silva S.M., Nagib P.R.A., de Moraes Crespo A., Amaral A.C., Is it possible to track intracellular chitosan nanoparticles using magnetic nanoparticles as contrast agent? Bioorg. Med. Chem., 2019, 27, 2637-2643.10.1016/j.bmc.2019.04.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Hu Q., Bae M., Fleming E., Lee J., Luo Y., Biocompatible polymeric nanoparticles with exceptional gastrointestinal stability as oral delivery vehicles for lipophilic bioactives, Food. Hydrocoll., 2019, 89, 386-395.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.10.057Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Jin Z., Li W., Cao H.W., Zhang X., Chen G., Wu H., Guo C., Zhang Y., Kang H.,Wang Y.F., Zhao K., Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of N-2-HACC and characterization of nanoparticleswith N-2-HACC and CMC as a vaccine carrier, Chem. Eng. J., 2013, 221, 331-341.10.1016/j.cej.2013.02.011Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Jin Z., Li D., Dai C.X., Cheng G.G.,Wang X.H., Zhao K., Response of live Newcastle disease virus encapsulated in N-2-Hydroxypropyl dimethylethyl ammonium chloride chitosan nanoparticles, Carbohydr. Polym., 2017, 171, 267-280.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.05.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Dai C.X., Kang H., Yang W.Q., Sun J.Y., Liu C.L., Cheng G.G., Rong G.Y., Wang X.H., Wang X., Jin Z., Zhao K., O-2′-Hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan nanoparticles for the delivery of live Newcastle disease vaccine, Carbohydr. Polym., 2015, 130, 280-289.10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.05.008Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Wickline S.A., Neubauer A.M., Winter P.M., Caruthers S.D., Lanza G.M., Molecular imaging and therapy of atherosclerosis with targeted nanoparticles, J. Magn. Reson Imaging, 2007, 25, 667-680.10.1002/jmri.20866Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Akagi T., Akashi M., Development of polymeric nanoparticles-based vaccine, Nihon. Rinsho., 2006, 64, 279-285.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Mundargi R.C., Babu V.R., Rangaswamy V., Patel P., Aminabhavi T.M., Nano/microtechnologies for delivering macromolecular therapeutics using poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) and its derivatives, J. Control. Release, 2008, 125, 193-209.10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.09.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Nagavarma B.V.N., Yadav H.K.S., Ayaz A., Vasudha L.S., Shivakumar H.G., Different techniques for preparation of polymeric nanoparticles-A review, Asian. J. Pharm. Clin. Res., 2012, 5, 16-23.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Danhier F., Ansorena E., Silva J.M., Coco R., Le Breton A., Preat V., PLGA-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications, J. Control. Release, 2012, 161, 505-522.10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Shweta S., Ankush P., Shivpoojan K., Rajat S., PLGA-based nanoparticles: A new paradigm in biomedical applications, Trend. Anal. Chem., 2016, 80, 30-40.10.1016/j.trac.2015.06.014Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Crucho C.I.C., Barros M.T., Polymeric nanoparticles: A study on the preparation variables and characterization methods, Mater. Sci. Eng. C., 2017, 80, 771-784.10.1016/j.msec.2017.06.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Sadat T.M.F., Nejati-Koshki K., Akbarzadeh A., Yamchi M.R., Milani M., Zeiqhamian V., Rahimzadeh A., Alimohammadi S., Hanifehpour Y., Joo S.W, PLGA-based nanoparticles as cancer drug delivery systems, Asian. Pac. J. Cancer Prev., 2014, 15, 517-535.10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.2.517Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Moinard-Chécot D., Chevalier Y., Briançon S., Beney L., Fessi H., Mechanism of nanocapsules formation by the emulsion-diffusion process, J. Colloid. Interface. Sci., 2008, 317, 458-468.10.1016/j.jcis.2007.09.081Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Catarina P.R., Neufeld R.J., Ribeiro A.J., Veiga F., Nanoencapsulation I. Methods for preparation of drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles, Nanomedicine: NBM., 2006, 2, 8-21.10.1016/j.nano.2005.12.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Jeong Y.I., Cho C.S., Kim S.H., Ko K.S., Kim S.I., Shim Y.H., Nah J.W., Preparation of poly(dl-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles without surfactant, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2001, 80, 2228-2236.10.1002/app.1326Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Leo E., Brina B., Forni F., Vandelli M.A., In vitro evaluation of PLA nanoparticles con-taining a lipophilic drug in water-soluble or insoluble form, Int. J. Pharm., 2004, 278, 133-141.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.03.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Masood F., Polymeric nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery system for cancer therapy,Mater. Sci. Eng. C., 2016, 60, 569-578.10.1016/j.msec.2015.11.067Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Rao J.P., Geckeler K.E., Polymer nanoparticles: Preparation techniques and size-control parameters, Prog. Polym. Sci., 2011, 36, 887-913.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.01.001Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Campardelli R., Baldino L., Reverchon E., Supercritical fluids applications in nanomedicine, J. Supercritical. Fluids., 2015, 101, 193-214.10.1016/j.supflu.2015.01.030Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Mishima K., Matsuyama K., Tanabe D., Yamauchi S., Young T.J., Johnston K.P, Microencapsulation of proteins by rapid expansion of supercritical solution with a nonsolvent, Aiche. J., 2000, 46, 857-865.10.1002/aic.690460418Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Sun Y.P., Guduru R., Lin F., Whiteside T., Preparation of nanoscale semi-conductors through the rapid expansion of supercritical solution (RESS) into liquid solution, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2000, 39, 4663-4669.10.1021/ie000114jSuche in Google Scholar

[39] Lai P., Daear W., Löbenberg R., Prenner E.J., Overview of the preparation of organic polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery based on gelatine, chitosan, poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolic acid) and polyalkylcyanoacrylate, Colloid. Surfaces. B., 2014, 118, 154-163.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.03.017Suche in Google Scholar

[40] George A., Shah P.A., Shrivastav P.S., Natural biodegradable polymers based nano-formulations for drug delivery: A review, Int. J. Pharm., 2019, 561, 244-264.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.03.011Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Zhao X., Yin L.C., Ding J.Y., Tang C., Gu S.H., Yin C.H., Mao Y.M., Thiolatedtrimethyl chitosan nanocomplexes as gene carriers with high in vitro and in vivo transfection efficiency, J. Control. Release, 2010, 144, 46-54.10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.022Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Li X., Deng X., Yuan M., Xiong C., Huang Z., Zhang Y., Jia W., In vitro degradation and release profiles of poly-DL-lactide-poly(ethylene glycol) microspheres with entrapped proteins, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2000, 78, 140-148.10.1002/1097-4628(20001003)78:1<140::AID-APP180>3.0.CO;2-PSuche in Google Scholar

[43] Vasir J.K., Labhasetwar V., Biodegradable nanoparticles for cytosolic delivery of therapeutics, Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev., 2007, 59, 718-728.10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.003Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Schliecker G., Schmidt C., Fuchs S., Kissel T., Characterization of a homologous series of D, L-lactic acid oligomers: a mechanistic study on the degradation kinetics in vitro Biomaterials, 2003, 24, 3835-3844.10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00243-6Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Namvar A., Bolhassani A., Khairkhah N., Motevalli F., Physico-chemical Properties of Polymers: An important system to overcome the cell barriers in gene transfection, Biopolymers, 2015, 103, 363-375.10.1002/bip.22638Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Guo D., Xie G., Luo J., Mechanical properties of nanopar-ticles: basics and applications, J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys., 2014, 47, 1-25.10.1088/0022-3727/47/1/013001Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Ibrahim K., Khalid S., Idrees K., Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities, Arab. J. Chem., 2017, 5, 1878-5352.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Talmadge J.E., The pharmaceutics and delivery of therapeutic polypeptides and proteins, Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev., 1993, 10, 247-299.10.1016/0169-409X(93)90049-ASuche in Google Scholar

[49] Fabienne D., Eduardo A., Joana M.S., Régis C., Aude L.B., Véronique P., PLGA-based nanoparticles: An overview of biomedical applications, J. Control. Release, 2012, 161, 505-522.10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043Suche in Google Scholar

[50] George D.M., Alexandru M.G., Cornelia B., Ludovic E.B., Polymeric protective agents for nanoparticles in drug delivery and targeting, Int. J. Pharm., 2016, 510, 419-429.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.03.014Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Dammak I., Paulo José do A.S., Formulation optimization of lecithin-enhanced pickering emulsions stabilized by chitosan nanoparticles for hesperidin encapsulation, J. Food. Eng., 2018, 229, 2-11.10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.11.001Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Kumar P.S., Ramakrishna S., Saini T.R., Diwan P.V., Influence of microencapsulation method and peptide loading on formulation of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) insulin nanoparticles, Pharmazie, 2006, 61, 613-617.Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Daniel P., Nazende G.T., Marc S., Influence of different stabilizers on the encapsulation of desmopressin acetate into PLGA nanoparticles, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm., 2017, 118, 48-55.10.1016/j.ejpb.2016.12.003Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Ribeiro S., Hussain N., Florence A.T., Release of DNA from dendriplexes encapsulated in PLGA nanoparticles, Int. J. Pharm., 2005, 298, 354-360.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.03.036Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Kim I.S., Lee S.K., Park Y.M., Lee Y.B., Shin S.C., Lee K.C., Oh I.J., Physicochemical characterization of poly( L-lactic acid) and poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles with polyethylen-imine as gene delivery carrier, Int. J. Pharm., 2005, 298, 255-262.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.04.017Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Ishii T., Okahata Y., Sato T., Mechanism of cell transfection with plasmid/chitosan complexes, Biochim. Biophys. Acta., 2001, 1514, 51-64.10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00362-5Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Mao S., Sun W., Kissel T., Chitosan-based formulations for delivery of DNA and siRNA, Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev., 2010, 62, 12-27.10.1016/j.addr.2009.08.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[58] Zhao K., Han J.Y., Zhang Y., Wei L., Yu S., Wang X.H., Jin Z., Wang Y.F., Enhancing mucosal immune response of Newcastle disease virus DNA vaccine using N-2-Hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan and N,O-carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles as delivery carrier, Mol. Pharm., 2018, 15, 226-37.10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00826Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Yu S., Xu X., Feng J., Liu M., Hu K., Chitosan and chitosan coating nanoparticles for the treatment of brain disease, Int. J. Pharm., 2019, 560, 282-293.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.02.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Bernocchi B., Carpentier R., Betbeder D., Nasal nanovaccines, Int. J. Pharm., 2017, 530, 128-138.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.07.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Mohamed S.H., Arafa A.S., Mady W.H., Fahmy H.A., Omer L.M., Morsi R.E., Preparation and immunological evaluation of inactivated avian influenza virus vaccine encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles, Biologicals, 2017, 51, 1045-1056.10.1016/j.biologicals.2017.10.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Kumar M., Behera A.K., Lockey R.F., Zhang J., Bhullar G., de la Cruz C.P., Chen L.C., Leong K.W., Huang S.K., Mohapatra S.S., Intranasal gene transfer by chitosan-DNA nanospheres protects BALB/c mice against acute respiratory syncytial virus infection, Hum. Gene. Therapy, 2002, 13, 1415-1425.10.1089/10430340260185058Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[63] Huang T., Song X.H., Jing J., Zhao K.L., Shen Y.M., Zhang X.Y., Yue B., Chitosan-DNA nanoparticles enhanced the immunogenicity of multivalent DNA vaccination on mice against Trueperella pyogenes infection, J. Nanobiotechnol., 2018, 16, 1477-3155.10.1186/s12951-018-0337-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] Mohamed E., Jie H., Mohan E., Bioinspired preparation of alginate nanoparticles using microbubble bursting, Mater. Sci. Eng. C., 2015, 46, 132-139.10.1016/j.msec.2014.09.036Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Borqes O., Silva M., de Sousa A., Borchard G., Junqinqer H.E., Cordeiro-da-Silva A., Alginate coated chitosan nanoparticles are an effective subcutaneous adjuvant for hepatitis B surface antigen, Int. Immunol., 2008, 8, 1773-1780.10.1016/j.intimp.2008.08.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[66] Ekici S., Ilgin P., Butun S., Sahiner N., Hyaluronic acid hydrogel particles with tunable charges as potential drug delivery devices, Carbohydr. Polym., 2011, 84, 1306-1313.10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.01.028Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Singh M., Briones M., O’ Hagan D.T., A novel bioadhesive intranasal delivery system for inactivated infuenza vaccines, J. Control. Release, 2001, 70, 267-276.10.1016/S0168-3659(00)00330-8Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Verheul R.J., Slutter B., Bal S.M., Bouwstra J.A., Jiskoot W., Hennink W.E., Covalently stabilized trimethyl chitosan-hyaluronic acid nanoparticles for nasal and intradermal vaccination, J. Control. Release., 2011, 156, 46-52.10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Kawada J., Wada H., Isobe M., Gnjatic S., Nishikawa H., Jung-bluth A.A., Okazaki N., Uenaka A., Nakamura Y., Fujiwara S., Mizuno N., Saika T., Ritter E., Yamasaki M., Miyata H., Ritter G., Murphy R., Venhaus R., Pan L., Old L.J., Doki Y.C., Nakayama E., Heterocliticsero-logical response in esophageal and prostate cancer patients after NY-ESO-1 protein vaccination, Int. J. Cancer., 2012, 130, 584-592.10.1002/ijc.26074Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[70] Kong I.G., Sato A., Yuki Y., Nochi T., Takahashi H., Sawada S., Mejima, M., Kurokawa S., Okada K., Sato S., Briles D.E., Kunisawa J., Inoue Y., Yamamoto M., Akiyoshi K., Kiyono H., Nanogel-based PspA intra-nasal vaccine prevents invasive disease and nasal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Infect. Immun., 2013, 81, 1625-1634.10.1128/IAI.00240-13Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[71] Zhang L., Li G., Gao M., Liu X., Ji B., Hua R., Zhou Y., Yang Y., RGD-peptide conjugated inulin-ibuprofen nanoparticles for targeted delivery of Epirubicin Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2016, 144, 81-89.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.03.077Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Gupta N., Jangid A.K., Pooja D., Kulhari H., Inulin: A novel and stretchy polysaccharide tool for biomedical and nutritional applications, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2019, 132, 852-86310.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.188Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Petrovsky N., Cooper P.D., Carbohydrate-based immune adjuvants, Expert. Rev. Vaccines., 2011, 10, 523-537.10.1586/erv.11.30Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[74] Jiménez-Sánchez M., Pérez-Morales R., Goycoolea F.M., Praznik M.M.W., Loeppert R., Bermúdez-Morales V., Guadalupe Z.P., Ayala M., Olvera C., Self-assembled high molecular weight inulin nanoparticles: Enzymatic synthesis, physicochemical and biological properties, Carbohydr. Polym 2019, 215, 160-169.10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.03.060Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Zhang L., Li Y.,Wang C., Li G., Zhao Y., Yang Y., Synthesis of methylprednisolone loaded ibuprofen modified inulin based nanoparticles and their application for drug delivery, Materials Science and Engineering C, 2014, 42, 111-115.10.1016/j.msec.2014.05.025Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[76] Banerjee A., Bandopadhyay R., Use of dextran nanoparticle: A paradigm shift in bacterial exopolysaccharide based biomedical applications, Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2016, 87, 295-301.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.02.059Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Joshy K.S., George A., Snigdha S., Joseph B., Kalarikkal N., Novel core-shell dextran hybrid nanosystem for anti-viral drug delivery, Mater. Sci. Eng. C., 2018, 93, 864-872.10.1016/j.msec.2018.08.015Suche in Google Scholar

[78] Minigo G., Scholzen A., Tang C.K., Hanley J.C., Kalkanidis M., Pietersz G.A., Apostolopoulos V., Plebanski M., Poly-L-lysinecoated nanoparticles: a potent delivery system to enhance DNA vaccine efficacy, Vaccine, 2007, 25, 1316-1327.10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.086Suche in Google Scholar

[79] Furugaki K., Cui L., Kunisawa Y., Osada K., Shinkai K., Tanaka M., Kataoka K., Nakano K., Intraperitoneal administration of a tumor-associated antigen SART3, CD40L, and GM-CSF gene-loaded polyplex micelle elicits a vaccine effect in mouse tumor models, Plos One, 2014, 9, 1-14.10.1371/journal.pone.0101854Suche in Google Scholar

[80] Zhang M.M., Hong Y.H., Chen W.J., Wang C., Polymers for DNA vaccine delivery, ACS. Biomater. Sci. Eng., 2017, 3, 108-125.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00418Suche in Google Scholar

[81] Kumar R., Sahoo G.C., Pandey K., Das V., Das P., Study the effects of PLGA-PEG encapsulated Amphotericin B nanoparticle drug delivery system against Leishmaniadonovani, Drug. Deliv., 2015, 22, 383-388.10.3109/10717544.2014.891271Suche in Google Scholar

[82] Hiremath J., Kang K-I., Xia M., Elaish M., Binjawadagi B., Ouyang K., Dhakal S., Arcos J., Torrelles J.B., X Jiang., Lee C.W., Renukaradhya G.J., Entrapment of H1N1 Influenza Virus Derived Conserved Peptides in PLGA Nanoparticles Enhances T Cell Response and Vaccine Efficacy in Pigs, Plos one, 2016,11, 1-15.10.1371/journal.pone.0151922Suche in Google Scholar

[83] Maria M., Naveed A., Asimur R., Recent applications of PLGA based nanostructures in drug delivery, Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2017,159, 217-231.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.038Suche in Google Scholar

[84] Gupta R.K., Singh M., O’ Hagan D.T., Poly (lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles for the development of single-dose controlled-release vaccines, Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev., 1998, 32, 225-246.10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00012-XSuche in Google Scholar

[85] Jaganathan K.S., Vyas S.P., Strong systemic and mucosal immune responses to surface modified PLGA microspheres containing recombinant Hepatitis B antigen administered intranasally, Vaccine, 2006, 24, 4201-4211.10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.011Suche in Google Scholar

[86] Vila A., Sánchez A., Tobío M., Calvo P., Alonso M.J., Design of biodegradable particles for protein delivery, J. Control. Release, 2002, 78, 15-24.10.1016/S0168-3659(01)00486-2Suche in Google Scholar

[87] Malik A., Gupta M., Mani R., Bhatnagar R., Single-dose Ag85B-ESAT-6 loaded–poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles confer protective immunity against tuberculosis, Int. J. Nanomed., 2019, 14, 3129-3143.10.2147/IJN.S172391Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[88] Haas J., Kumar M.N.R., Borchard G., Bakowsky U., Lehr C.M., Preparation and characterization of chitosan and trimethylchitosan-modified polyϵ-caprolactone) nanoparticles as DNA carriers, AAPS. Pharm. Sci. Tech., 2005, 6, E22-E30.10.1208/pt060106Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[89] Gupta N.K., Tomar P., Sharma V., Dixit V.K., Development and characterization of chitosan coated poly-ε-caprolactone) nanoparticulate system for effective immunization against influenza, Vaccine, 2011, 29, 9026–9037.10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[90] Jesus S., Soares E., Costa J., Borchard G., Borges O., Immune response elicited by an intranasally delivered HBsAg low-dose adsorbed to poly-epsilon-caprolactone based nanoparticles, Int. J. Pharm., 2016, 504, 59-69.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.03.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Mehdi F., Ali H., Kobra R., Soghrat F., Efficiency of flubendazoleloaded mPEG-PCL nanoparticles: A promising formulation against the protoscoleces and cysts of Echinococcus granulosus Acta. Trop., 2018, 187, 190-200.10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[92] Oliveira A.L., Pinho C., Fonte P., Sarmento B., Dias A.C.P., Development, characterization, antioxidat and hepatoprotective properties of polyε-caprolactone) nanoparticles loaded with a neuroprotective fraction of Hypericum perforatum Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2018, 110, 185-196.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.103Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[93] Li M., Rouaud O., Poncelet D., Microencapsulation by solvent evaporation: State of the art for process engineering approaches, Int. J. Pharm., 2008, 363, 26-39.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[94] Sharma R., Agrawal U., Mody N., Vyas S.P., Polymer nanotechnology based approaches in mucosal vaccine delivery: Challenges and opportunities, Biotechnol. ADV., 2015, 33, 64-79.10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.12.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[95] Petersen L.K., Ramer-Tait A.E., Broderick S.R., Kong C.S., Ulery B.D., Rajan K., Wannemuehler M.J., Narasimhan B, Activation of innate immune responses in a pathogen-mimicking manner by amphiphilicpolyanhydride nanoparticle adjuvants, Biomaterials, 2011, 32, 6815-6822.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.063Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[96] Huang D., Wu D.C., Biodegradable dendrimers for drug delivery, Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater., 2018, 90, 713-727.10.1016/j.msec.2018.03.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[97] Li J., Liang H.M., Liu J., Wang Z.Y., Poly (amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimer mediated delivery of drug and pDNA/siRNA for cancer therapy, Int. J. Pharm., 2018, 546, 215-225.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.05.045Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[98] Alemzadeh E., Dehshahri A., Izadpanah K., Ahmadi F.. Plant virus nanoparticles: novel and robust nanocarriers for drug delivery and imaging, Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2018, 167, 20-27.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.03.026Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[99] Lancelot A., Gonzalez-Pastor R., Claveria-Gimeno R., Romero P., Abian O., Martin-Duque P., Cationic poly(ester amide) dendrimers: alluring materials for biomedical applications, J. Mater. Chem. B., 2018, 6, 3956-3968.10.1039/C8TB00639CSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[100] Marcet I., Weng S., Sáez-Orviz S., Rendueles M., Díaz M., Production and characterisation of biodegradable PLA nanoparticles loaded with thymol to improve its antimicrobial effect, J. Food. Eng., 2018, 239, 26-32.10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.06.030Suche in Google Scholar

[101] Jain A.K., Goyal A.K., Mishra N., Vaidya B., Mangal S., Vyas S.P., PEG-PLA-PEG block copolymeric nanoparticles for oral immunization against hepatitis B, Int. J. Pharm., 2010, 387, 253-262.10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.12.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[102] Ataman-Önal Y., Munier S., Ganée A., Terrat C., Durand P.Y., Battail N., Martiono F., Grand R.L., Charles M.H., Delair T., Verrier B., Surfactant-free anionic PLA nanoparticles coated with HIV-1 p24 protein induced enhanced cellular and humoral immune responses in various animal models, J. Control. Release, 2006, 112, 175-185.10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.02.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[103] Mutwiri G., TLR9 agonists: immune mechanisms and therapeutic potential in domestic animals, Vet. immunol. Immunop., 2012, 148, 85-89.10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.05.032Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[104] Tacken P.J., Zeelenberg I.S., Cruz L.J., van Hout-Kuijer M.A., van de Glind G., Fokkink R.G., Lambeck, A.J.A., Figdor C.G., Targeted delivery of TLR ligands to human and mouse dendritic cells strongly enhances adjuvanticity, Blood, 2011, 118, 6836-6844.10.1182/blood-2011-07-367615Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[105] Hunsawong T., Sunintaboon P., Warit S., Thaisomboonsuk B., Jarman R.G., Yoon I.K., Ubol S., Fernandez S., A novel dengue virus serotype-2 nanovaccine induces robust humoral and cell-mediated immunity in mice, Vaccine, 2015, 33, 1702-1710.10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.02.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[106] Bonito P.D., Petrone L., Casini G., Francolini I., Ammendolia M.G., Accardi L., Piozzi A., D’llario L., Martinelli A., Amino-functionalized poly(L-lactide) lamellar single crystals as a valuable substrate for delivery of HPV16-E7 tumor antigen in vaccine development, Int. J. Nanomed., 2015, 10, 3447-3458.10.2147/IJN.S76023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[107] Williams J.P. Application of magnetic field hyperthermia and superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles to HIV-1-specific T-cell cytotoxicity, Int. J. Nanomed., 2013, 2543-2554.10.2147/IJN.S44013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[108] Kumar V., Dandapat S., Kumar A., Kumar N., Preparation and characterization of chitosan nanoparticles “Alternatively, carrying potential” for cellular and humoral immune responses, Advances in Animal and Veterinary Sciences, 2014, 2, 414-417.10.14737/journal.aavs/2014/2.7.414.417Suche in Google Scholar

[109] Gao W.W., Chen Y.J., Zhang Y., Zhang Q.Z., Zhang L.F., Nanoparticle-based local antimicrobial drug delivery, Adv. Drug. Deli. Rev., 2018, 127, 46-57.10.1016/j.addr.2017.09.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[110] Peek L.J., Middaugh C.R., Berkland C., Nanotechnology in vaccine delivery, Adv. Drug. Deli. Rev., 2008, 60, 915-928.10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.017Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[111] Gutjahr A., Phelip C., Coolen A.L., Monge C., Boisgard A.S., Paul S., Verrier B., Biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles-based vaccine adjuvants for lymph nodes targeting, Vaccine, 2016, 4, 1-16.10.3390/vaccines4040034Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[112] Zhao L., Seth A.,Wibowo N., Zhao C.X., Mitter N., Yu C.Z., Middelberg A.P.J., Nanoparticle vaccines, Vaccine, 2014, 32, 327-337.10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.11.069Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 S. Guo et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview