Abstract

Mesoporous silica microspheres were prepared by the polymerization-induced colloid aggregation (PICA) and pseudomorphic synthesis methods. The prepared microspheres have high specific surface area and MCM-41 type structure. In the PICA process, acidic silica sol was utilized as silica source and the effect of molar ration (formaldehyde/urea) was investigated. Moreover, the influences of reaction time and temperature were also studied. The specific surface area of porous and mesoporous silica microspheres were 186.4 m2/g and 900.4 m2/g, respectively. The materials were characterized by SAXS, FTIR, SEM, TEM and nitrogen sorption measurements. The prepared silica microspheres were functionalized by (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane and then used to remove the lead from aqueous solution. The result indicates that the grafted silica microspheres have rapid adsorption capacity and good reproducibility. The adsorption data was fitted well with the Langmuir isotherm model, and the maximum adsorption capacities for MCM-41 silica microspheres were 102.7 mg/g.

1 Introduction

The increasing amounts of heavy metals in water causes a serious damage to human health and ecological systems. The most abundant and harmful metals in the liquid effluents are Cr, Ni, Zn, Cu, and Cd, which are considered to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic substances [1, 2, 3, 4]. The WorldHealth Organization (WHO) proclaimed that the acceptable concentration of copper and lead in drinking water must be less than 2.0 mg/L and 0.05 mg/L, respectively [5]. In order to remove heavy metals from water, a wide variety of techniques such as ion exchange, reverse osmosis, nanofiltration, precipitation, coagulation or co-precipitation, electrodialysis, flotation, extraction, electrolysis and adsorption are available [6, 7, 8]. The adsorption technique is commonly used due to its simplicity, low-cost, reversibility, which can remove even trace quantities of metal ions from water [9]. For the adsorption processes, a variety of functional groups can be grafted or incorporated onto the surface of mesoporous channels to prepare highly effective adsorbents. The porous silica functionalized with various chelating agents have been widely applied as adsorbents, because of its high surface area, large uniform pores and tunable porous sizes. Moreover, it has good mechanical strength, high thermal stability, stability under a wide pH range and does not swell [10]. Thus, the developments of functionalized mesoporous adsorbents for removal of heavy metal ions using incorporated ligands with appropriate functional groups have attracted considerable interests [11]. The sol-gel silica functionalized with different organic reagents such as crown ether [12], 1,5-diphenylcarbazide and trialkyl phosphine oxides have been prepared and applied for removal of metals [13, 14]. In addition, polyamine-functionalized materials have been also studied due to their implication in anion removal, CO2 capture, mobilization of biological molecules and basic catalysis of fine chemistry reactions [15, 16, 17, 18, 19].

Since being prepared by a unique self-assembly process between surfactants and alkoxysilane in 1992, the mesostructured silica attracted considerable attentions because of its higher surface area, large uniform pores and tunable pore sizes [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The shape, size and structure of particles are all significant. In catalysis, control over particle size is important to transfer processes from batch experiments to continuous processes in order to avoid filter plugging by fine particles and to optimize mass transfer. In the drug delivery or galenic applications, the particle size of the host matrix is important to affect the drug or cosmetic action. For instance, particles with size of approximately 5 μm will penetrate into the skin pores and allow the diffusion of drugs or cosmetics inside the derm. Because of easily being retained at the surface of skin, the larger particles (0.5 mm to 1 mm) are required in pressure drop applications, such as in protective gas masks, where individuals must breathe or blow through a bed of particles. Thus, simultaneous and independent control of their textural and morphological properties remains a challenge. Several strategies have been investigated with the aim at producing spherical mesostructured silica with adjustable sizes. Among them, fluorine-promoted condensation, spray-drying of aerosol-generated microdroplets and of nanoparticles have been proven effective. However, particle coalescence has never been completely prevented, and the products exhibited broad size distributions [25, 26, 27].

Previously, Zhao et al. successfully prepared mesoporous silica particles by polymerization-induced colloid aggregation (PICA) [28]. These particles exhibited good chromatographic performance because of their large surface areas and good monodispersity. However, the pore structure is disordered and the pore size distribution is wide. In recent study, many researchers have successfully prepared the ordered mesoporous silica by pseudomorphic synthesis process [29, 30, 31]. First, a mild alkaline solution was used to slowly dissolve silica. Then the generated silicate was adsorbed on surfactant to form a hybrid surfactant/silicate mesophase without changing the morphology of the silica particles. Finally, silica particles with ordered mesoporous structure and initial morphology was obtained after calcination.

In the present work, porous silica microspheres (PSMs) were prepared by a sol-gel process coupled with the PICA method, and then the MCM-41 silica microspheres were synthesized by pseudomorphic synthesis process using the prepared PSMs. The effects of pH and stirring time in the PICA process as well as the amounts of NaOH and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) in the pseudomorphic synthesis process were investigated. The PSMs and MCM-41 microspheres were functionalized with (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES) under a hydrothermal condition, and then used as adsorbents for removal of lead ion from aqueous solutions [32]. Moreover, the adsorption capacities were determined using Langmuir adsorption model.

2 Experimental

2.1 Reagents

All reagents were used without further purification. Silica sol (25%), APTES (Aladdin), ammonium hydroxide (25%), EtOH (99.7%), urea (99%), formaldehyde solution (38%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 96%), CTAB (99%), HCl (38%) toluene (99.5%) and lead nitrate (99%) were received from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2 Preparation of silica sol and porous silica microspheres

Silica sol, urea and ultra-pure water were mixed in a 250 ml round-bottomed flask with a magnetic stirrer. The suspension pH was adjusted using HCl. After stirring for another 30 min, the mixed solution of formaldehyde and ultra-pure water was added into the above suspension with rapid stirring for a specific time and allowed to react in a water bath at 40∘C for 1h without stirring. The suspension turned to white color and opaque at first, and then the white particles gradually sank to the bottom of flask. Then the reaction was terminated by adding a large amount of ultrapure water. The solid particles were collected by filtration, washed with ultra-purewater and EtOH, and dried in a vacuum oven at 60∘C for 12 h. The porous silica microspheres were obtained by calcining the solid particle with a staged heating process from 30 to 550∘C, to burn off the polymer.

2.3 Pseudomorphic transformation of porous silica microspheres

The prepared PSMs, NaOH, CTAB and ultra-pure water were mixed in a flask at 90°Cunder magnetic stirring to form a suspension, which was then transferred to a PTFE-lined autoclave and reacted at 125°C for 10 h under static condition. The precipitate was recovered by filtration, washed with ultra-pure water and EtOH, and dried in a vacuum oven at 60∘C for 12 h. The MCM-41 silica microspheres were obtained after the polymer was burned off.

2.4 Modification of silica microspheres

The silica microspheres were rehydroxylated first by refluxing in 10% HCl for 12 h. The rehydroxylated silica microspheres was dispersed in toluene. Then APTES was added, and the suspension was refluxed for 24 h. The solid was recovered by filtration, and washed with toluene and EtOH, respectively. The NH2-PSMs and NH2-MCM-41 were obtained using PSM and MCM-41 silica microspheres, respectively.

2.5 Determination of the adsorption capacities and reusability

Lead (II) solution was prepared using a reagent grade lead nitrate to obtain a stock solution with the concentration of 800 mg/L. The solution was diluted by ultra-pure water to obtain desired solution for adsorption experiments. The silica adsorbents were dried at 100∘C for 1 h in prior to the measurement of sample weight. The initial and final concentrations of lead ion in solutions were determined by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). The pH of the initial solution was adjusted to 4.0 by adding NaOH or sulfuric acid solution in all adsorption experiments.

The adsorption experiments were performed as follows: The PSM (0.1 g) was placed with lead ion in solution (50 mL) to prepare the solution with different concentrations (50, 100, 200, 400, 600 and 800 mg/L, respectively) for adsorption isotherm study at 293 K, separately. The flasks were then transferred to an incubator shaker and vibrated at 140 rpm for 24 h to ensure adsorption equilibrium. All batch experiments were repeated thrice under the same conditions and all the data that appear in this article are based on the average values.

For regeneration of the adsorbent after adsorption experiments, the silica microspheres with adsorbed lead were added into a 20 mL HCl solution (pH 2.0) under stirring for 2 h, and then the adsorbent was recovered by centrifugation. For thorough desorption, the above process was repeated thrice. The extracted silica microspheres were subsequently washed with an alkaline solution for the regeneration of amino groups. Then, the regenerated adsorbent was obtained and used in a second cycle.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and characterization of porous silica microspheres

The silica source of silica microspheres is silica sol and affects the PSMs’ formation is controlled by the amount of silica sol directly. The increasing amount of silica sol leads to higher content of silica in PSMs. Moreover, the solubility of silica sol is different when the addition of silica sol, and the reaction rate is different because of its influence on solute diffusion.

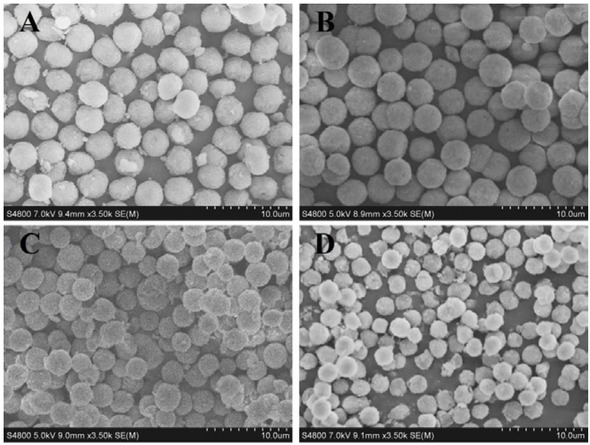

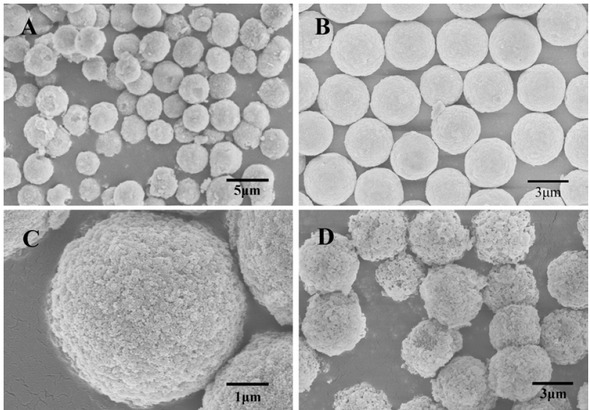

In this experiment, a series of silica gel microspheres were prepared by variation of the amount of silica sol at 12, 14, 16 and 18 g. The microspheres were characterized by scanning electron microscopy. The Figure 1 shows the SEM diagram of PSMs calcined with different amounts of silica sol under the identical conditions. It can be seen from the figure that when the amount of added silica sol is 14 g, the prepared microspheres exhibited the best sphericity. According to the reaction mechanism of PICA, if the amount of added silica sol is small, the silicon content is low in the prepared silica microspheres without a strong silica skeleton. Then, the surface of the microspheres collapses after being calcined at high temperature, and the particles deform, resulting in debris. With the increasing of silica sol dosage, the concentration of silica sol and the number of nucleation increase during the PICA process. When the amount of silica sol further increases, the particle size decreases, and the amount of silica microspheres is larger, even the particles are not completely spherical after agglomeration and precipitation, as shown in Figure 1(D). Under this preparation scale, 14 g of silica sol is the most suitable amount.

The SEM images of PSMs prepared at different silica sol addition, (A) 12g; (B) 14g; (C) 16g; (D) 18g

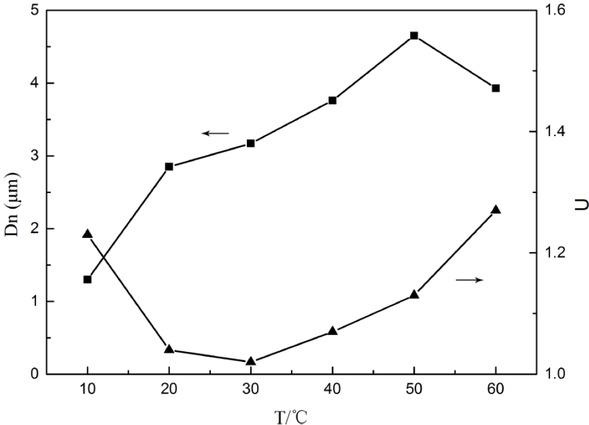

According to the reaction mechanism of PICA, temperature not only affects the polymerization rate of urea and formaldehyde, and the adsorption rate of silica particles by UF resin, but also affects the solubility of UF resin and the Brownian motion of silica particles. By calculating the average particle size Di of n (n>100) microspheres in the SEM images of the silicon microspheres under different pH conditions, the Dn and U values can be obtained by the following formula:

where, Dn is average particle size and U is width of the particle size distribution. The larger U value, the wider the particle size distribution, and the monodisperse mark is U < 1.05.

The Figure 2 shows the effect of temperature on the particle size of PSMs. The diameter of the prepared PSMs were observed to increase obviously with the increase of temperature. In addition, the particle size distribution of PSMs is narrow and the monodisperse property is good in temperature range between 20∘C and 40∘C. When the temperature is less than 20∘C or higher than 40∘C, the particle size distribution will widen.

Influence of temperature on particle size (Dn) and particle size distribution (U)

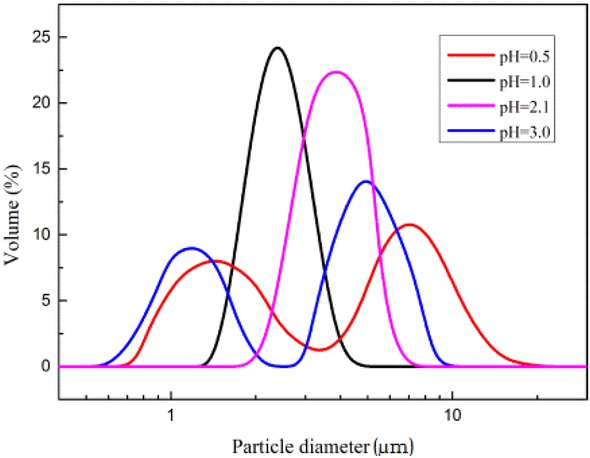

The Figure 3 shows the particle size distribution of PSMs prepared under different pH conditions. The preparation of PSMs by PICA is divided into two stages: nucleation and growth phases. During the nucleation phase, H+ in the system can promote the polymerization process of urea formaldehyde and thus increase the nucleation rate. Therefore, when pH drops during the nucleation stage, the number of generated hybrid microspheres increases in the system, resulting in the decrease of the obtained particle size. When pH is below 1.0 or above 2.1, the particle size of the PSMs becomes non-uniform.

The particle size distributions of PSMs prepared at different pH

When the pH above 2.1 in the system, urea formaldehyde polymerization rate is slow; thus, the nucleation time increases, which results in the formation of new nuclei during growth, that is, the second nucleation phenomenon, resulting in a number of peaks in the particle size distribution profile of the resulting microspheres.

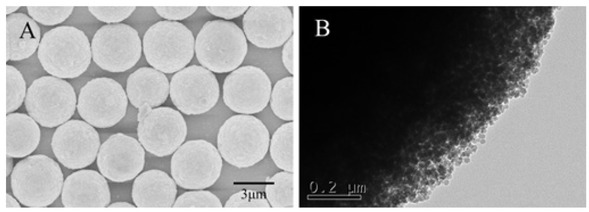

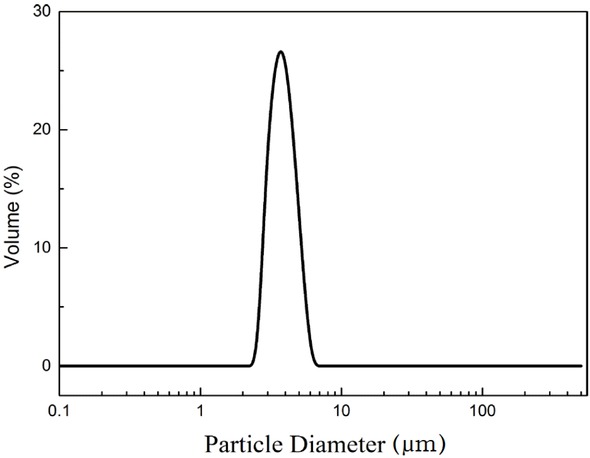

The Figure 4 exhibits the SEM and TEM images of PSMs, which were successfully synthesized by the PICA method. The figure shows the PSMs were formed by accumulation of silica particles and the PSMs have good sphericity without any aggregation. The particle size distribution of PSMs is shown in Figure 5, in which the PSMs exhibited good monodispersity with average diameter of 3.76 μm. This finding corresponds to the SEM and TEM images.

The SEM (A) and TEM (B) images of PSMs

Particle size distribution of PSMs

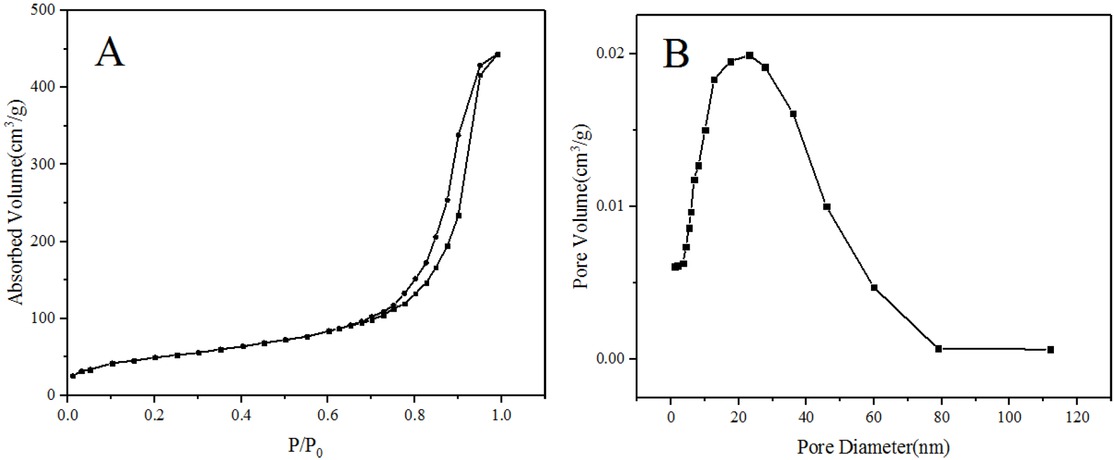

The nitrogen sorption isotherm and pore size distribution are shown in Figure 6. The isotherm is a type IV curve with a hysteresis loop near the higher relative pressure P/P0 = 0.8, indicating that the PSMs have large pore size and wide size distribution, which is corresponding to the pore size distribution [28]. The PSMs have a pore structure with the pore diameter between 1 nm and 60 nm. The specific surface area, pore volume and average pore size are 186.4 m2/g, 0.797 cm3/g and 17.1 nm, respectively.

Nitrogen sorption isotherm (A) and pore size distribution (B) of PSMs

The Figure 7 shows the SEM images of PSMs prepared at different molar ratios of formaldehyde and urea. When the molar ratio is 1.25, the silica microspheres have good sphere and excellent dispersity. When the mole ratio is 1, the urea-formaldehyde resin mainly exists as a linear structure. The molecular chain easily moves in the system, and the resin is in contact with the silica particle molecular chain. On the other hand, a large number of secondary amino groups exist on the resin molecular chain, and the effect of secondary amino groups attract silicon hydroxyl groups that can enhance the adsorption between the resin and silica particle. Therefore, the rapid adsorption between the resin and silica particle will occur, the number of hybrid microspheres will increase and the diameter of silica microspheres will decrease. Moreover, the crosslinking structure of composite microspheres is reduced,which will cause the breakage after calcination. When the molar ratio of formaldehyde urea was 1.25, the polymerization rate of urea formaldehyde accelerated, the adsorption rate of silica particles and resin decreased, which led to a balance, and the hybrid microspheres maintained spherical shape at the growth stage. When the mole ratio between formaldehyde and urea was increased, the polymerization rate was further accelerated and the adsorption rate was further reduced, resulting in less silica particles adsorbed by the resin, the silica content in the hybrid microspheres reduced, and the silica microspheres shrank after calcination, the microspheres size become small. The surface of silica microspheres is very rough as shown in Figure 7.

The SEM images of porous silica microspheres prepared at different molar ratio of formaldehyde and urea, (A) 1; (B) 1.25; (C) 1.5; (D) 2

When the molar ratio between formaldehyde and urea was further increased, the silica content in the hybrid microspheres reduced drastically and the structure became difficult to maintain and broke after calcination. Therefore, monodisperse silica microspheres can be prepared at the formaldehyde/urea molar ratio of 1.25.

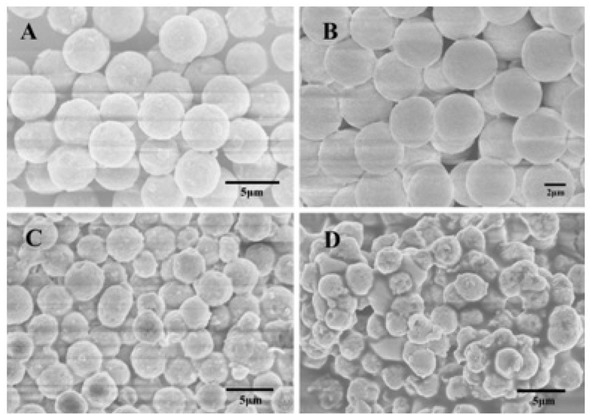

3.2 Pseudomorphic synthesis and characterization of MCM-41 microspheres

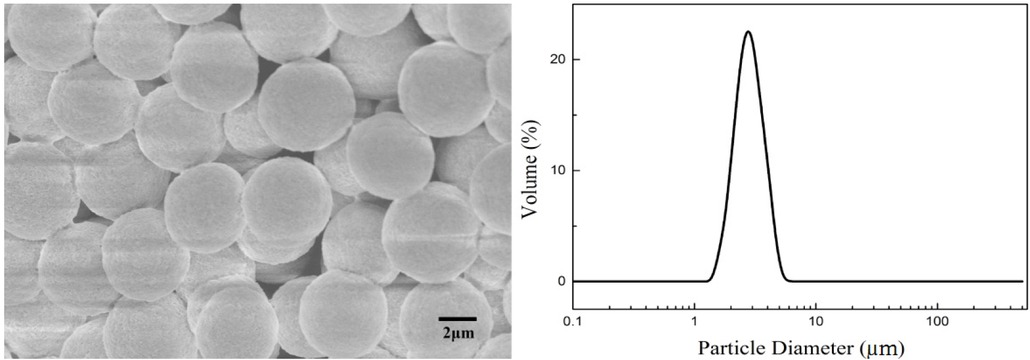

To prepare ordered mesoporous silica microspheres (MCM-41 silica microspheres), the pseudomorphic synthesis method was used to rebuild the pore structure of PSMs. The Figure 8 shows the SEM image and particle size distribution of MCM-41 silica microspheres. The SEM image shows that the morphology of the silica microspheres was preserved after the pseudomorphic synthesis, while the particle size reduced and the agglomeration phenomenon was observed. This phenomenon is attributed to the fact that the silica slowly dissolved, then the generated silicate was immediately assembled with the surfactant during the pseudomorphic synthesis. Thus, the pore size reduced, and the microspheres were slightly shrunk, resulting in the smaller particle size. Theoretically, when the silica dissolution rate is equal to the assembly rate, the silicate is immediately subjected to the assembly process to form the mesophase. The dissolved portion is immediately replaced by the mesophase, and the structure is successfully transformed to the MCM-41. However, in the reaction process, the generated silicate possibly assembled with the surfactant between the silica microspheres, resulting in agglomeration phenomenon with the particle size distribution widen.

SEM image and particle size distribution of ordered mesoporous silica microspheres

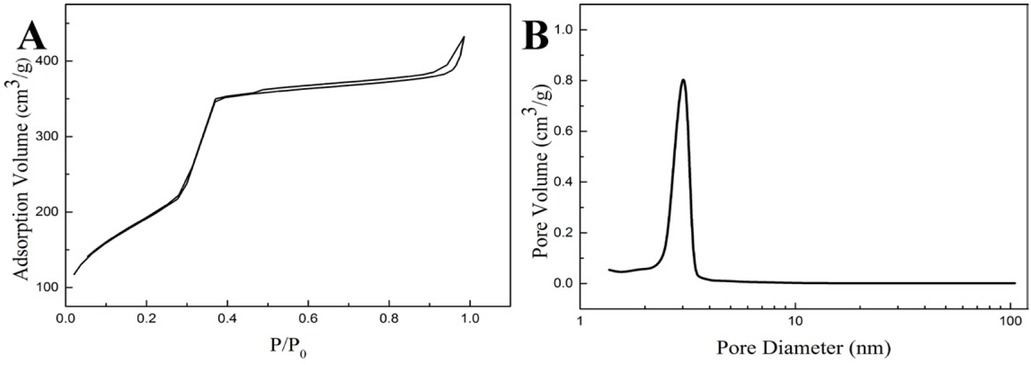

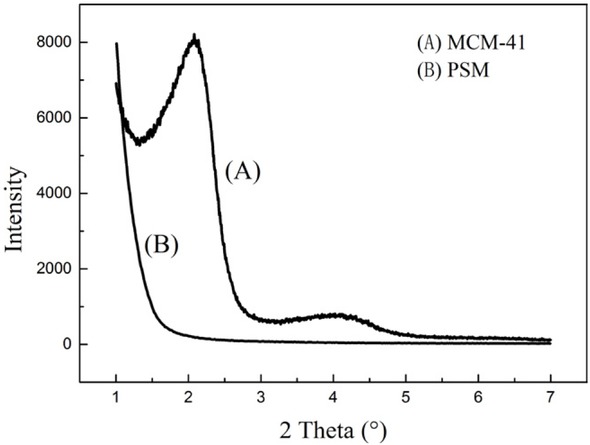

From the Figure 9, the nitrogen adsorption isotherm is standard type IV, which implies that the PSMs were transformed to mesoporous material successfully after pseudomorphic synthesis [30]. The pore size distribution indicates the MCM-41 sample has uniform pore diameter of 3.20 nm. From Figure 10, the SAXS pattern of the PSMs sample has no diffraction peak at low angles, and the MCM-41 exhibits Bragg reflections, which are consistent with the hexagonal mesoporous structure of MCM-41 [33]. These observations demonstrate that the structure of PSMs was successfully transformed into MCM-41 by pseudomorphic synthesis.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherm and pore size distribution of MCM-41 silica microspheres

SAXS patterns of (A) MCM-41 and (B) PSM

SEM images of ordered mesoporous silica microspheres prepared under different temperature, (A) 100∘C (B) 125∘C (C) 150∘C (D) 175∘C

Pseudomorphic synthesis occurred in the pores of PSMs, which is the self-assembly process of the surfactants and the silicates. This method can transform amorphous silica microspheres into silica-surfactant mesostructures without changing the shape and size of the microspheres. The pseudomorphic synthesis process is controlled by the self-assembly rate and silica dissolution rate. Thus, the effect of temperature is crucial. A series of silica microspheres were prepared under different temperatures to illustrate the influence of temperature.

3.3 Characterization of particles amine functionalized silica microspheres

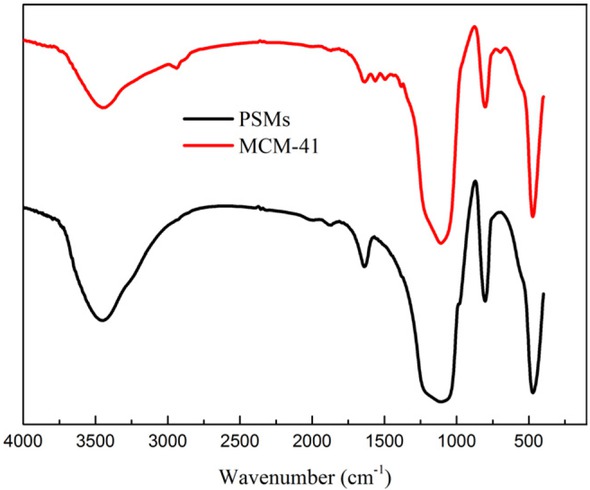

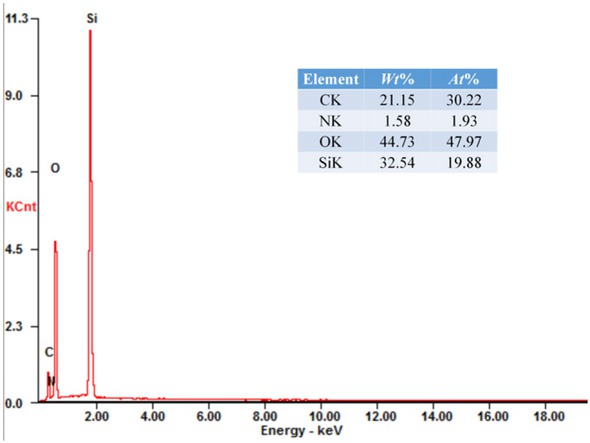

The amine functionalized MCM-41 silica microspheres were prepared using APTES as the modifier in anhydrous toluene. The silica microspheres were heated at 150∘C for 12 h to remove the physisorbed water before modification process. The Figure 12 shows the FT-IR spectra of unmodified and functionalized silica microspheres. The peaks around 1637 cm−1 and 3447 cm−1 correspond to the -OH stretching vibrations of silanol groups and the bending vibration of adsorbed water, respectively [34]. The vibration signals around 1109 cm−1, 803 cm−1 and 474 cm−1 presented in all samples, which are corresponding to Si-O-Si bands and the condensed silica network [35, 36]. The stretching band at 2936 cm−1 corresponds to C-H stretching in the propyl chain. The new peaks around 695 cm−1, 1494 cm−1 and 1564 cm−1 were attributed to the characteristic absorption peaks of -NH2 group as reported [35, 37]. The compositions of the modified MCM-41 silica microspheres were determined by EDS, which were shown in Figure 13. The strong N signal confirmed that -NH2 groups were successfully grafted onto the microspheres surface. The FT-IR and EDS spectra indicate that the -NH2 groups were successfully grafted on the surface of silica microspheres.

FT-IR spectra for unmodified and functionalized silica microspheres

EDS spectra of modified silica microspheres

3.4 Adsorption capacity and reusability of amino-functionalization silica microspheres

In order to determine the adsorption capacity of NH2-MCM-41 adsorbent, the equilibrium adsorption isotherms were investigated and the Langmuir model was used to describe adsorption process. The formula describing the equilibrium adsorption capacity (Qe, mg/g) is shown as follows:

where, C0 is the initial concentration and Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration of lead (II) in the solution, w (g) is the amount of adsorbent, and VPb (mL) is the initial volume of the lead (II) solution.

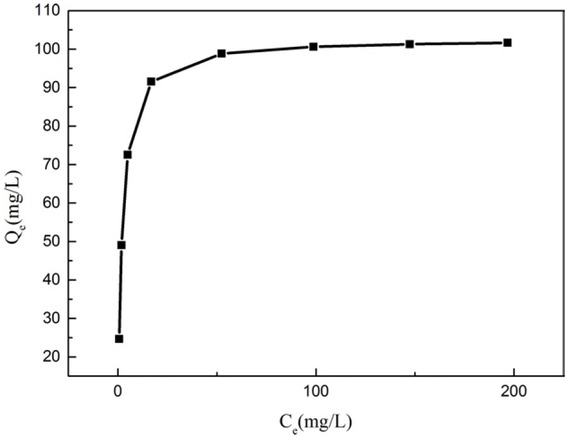

The Figure 14 displays the adsorption isotherms at 25∘C for NH2-MCM-41. The isotherms show a sharp initial slope, which indicates the NH2-MCM-41 as adsorbent have excellent adsorption properties at low metal concentration. The isotherms are consistent with the Langmuir isotherm; thus, the Langmuir model was used to describe the adsorption process. The expression of Langmuir isotherm is as follows:

Adsorption isotherms of lead ions on the amino-functionalized MCM-41 adsorbent

where, qm and b are the characteristic Langmuir parameters. qm is the maximum adsorption quantity, which shows that the metal adsorbed on material to form a complete monolayer, and b is a constant related to the intensity of adsorption.

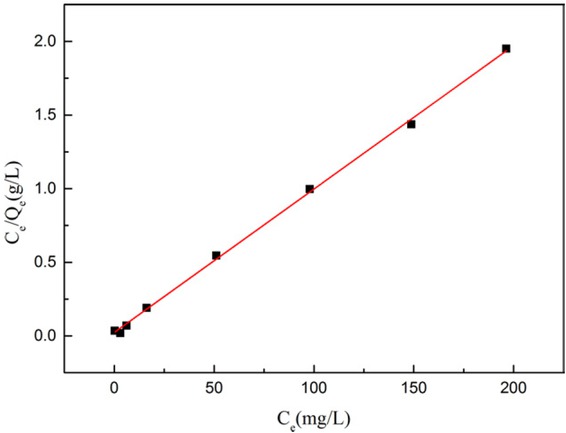

The Langmuir isotherms of lead ion adsorbed on MCM-41 are shown in Figure 15, in which the experimental data were successfully fitted by Langmuir model, and the regression coefficients of these two isotherms are 0.998. The results demonstrate that the type of lead ion adsorption on functionalized silica microspheres is monolayer fashion. From the Langmuir isotherms, the maximum adsorption capacity (qm) of NH2-MCM-41 silica microspheres is 102.7 mg/g, indicating that the silica microspheres have larger surface area with enough pore volume to support adsorption after pseudomorphic synthesis. The MCM-41 silica microspheres prepared by pseudomorphic synthesis were observed with excellent adsorption capacities after amino-functionalization.

Linearized Langmuir plots for lead ions on the amino-functionalizaed MCM-41 adsorbent

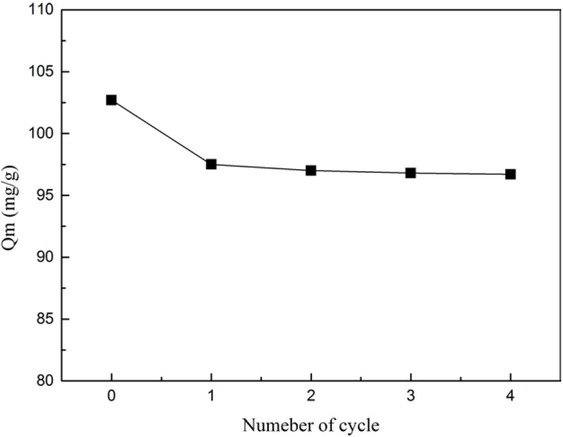

The reusability is important to evaluate the property of an adsorbent. After the adsorption experiment, the silica microspheres could be regenerated by washing with HCl and alkaline solution, and then drying in a vacuum oven. The Figure 16 shows the adsorption capacities of NH2-MCM-41 after a different number of cycles. The adsorption capacity decreased in the first cycle and then remained substantially constant. Given the presence of residual lead (II) in the pores of silica microspheres after the first cycle, the adsorption capacity decreased by 3% for NH2-PSMs after several cycles, which indicates that the MCM-41 silica microspheres have excellent regeneration capacity and reusability.

Adsorption capacities of amino-functionalized MCM-41 adsorbent after regeneration

4 Conclusions

The porous silica microspheres were synthesized by PICA method using acidic silica sol. The MCM-41 silica microspheres with large size of 3.27 μm and high specific surface area of 900.4 m2/g were successfully prepared by the pseudomorphic synthesis process using the synthesized PSMs as primary particles. The amino functionalized silica microspheres have rapid adsorption capacity and superior reproducibility. The maximum adsorption capacity for MCM-41 silica microspheres was 102.7 mg/g. Therefore, the MCM-41 silica microspheres, presenting excellent adsorption capacity after amino-functionalization, can be used as adsorbent for removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions.

Acknowledgement

This research was financially supported by the Foundation of Jiangsu Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Advanced Materials of Salt Chemical Industry (No. 82317070), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 21246002), Minjiang Scholarship of Fujian Province, Central-government Guided Special Funds for Local Economic Development (No. 830170778) and Strategic Emerging Industry Special R&D Project of Fujian Province (No. 82918001).

References

[1] Kılıç M., Kırbıyık Ç., Çepelioğullar Ö, Pütün A.E., Adsorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions by bio-char, a byproduct of pyrolysis, Appl. Surf. Sci., 2013, 283, 856-862.10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.07.033Search in Google Scholar

[2] Matusik J., Wścisło A., Enhanced heavy metal adsorption on functionalized nanotubular halloysite interlayer grafted with aminoalcohols, Appl. Clay Sci., 2014, 100, 50-59.10.1016/j.clay.2014.06.034Search in Google Scholar

[3] Chowdhury I.H., Chowdhury A.H., Bose P., Mandal S., Naskar M.K., Effect of anion type on the synthesis of mesoporous nanostructured MgO, and its excellent adsorption capacity for the removal of toxic heavy metal ions from water, RSC Adv., 2016, 6, 6038-6047.10.1039/C5RA16837FSearch in Google Scholar

[4] Scott A., Vadalasetty K.P., Chwalibog A. et al., Copper Nanoparticles As An Alternative Feed Additive In Poultry Diet: A Review, Nanotechnology Reviews, 2018, 7, 69-93.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0159Search in Google Scholar

[5] Gandhi M.R., Meenakshi S., Preparation and characterization of silica gel/chitosan composite for the removal of Cu(II) and Pb(II), Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2012, 50, 650-657.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[6] Cheremisinoff N.P., Handbook of water and wastewater treatment technologies. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2002.10.1016/B978-075067498-0/50014-0Search in Google Scholar

[7] Bennett G., Bennett G.,Standard handbook of hazardous waste treatment and disposal. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1989.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Inbaraj B.S.,Wang J.S., Lu J.F., Siao F.Y., Chen B.H., Adsorption of toxic mercury(II) by an extracellular biopolymer polyγ-glutamic acid), Bioresour. Technol., 2009, 100, 200-207.10.1016/j.biortech.2008.05.014Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ali A., Phull A.-R., Zia M., Elemental Zinc To Zinc Nanoparticles: Is Zno Nps Crucial For Life? Synthesis, Toxicological, And Environmental Concerns., Nanotechnology Reviews, 2018, 7, 413-441.10.1515/ntrev-2018-0067Search in Google Scholar

[10] Xi Y., Zhang L.Y., Wang S.S., Pore size and pore-size distribution control of porous silica, Sens Actuators B, 1995, 25, 347-352.10.1016/0925-4005(95)85078-3Search in Google Scholar

[11] Sayari A., Hamoudi S., Periodic Mesoporous Silica-Based Organic-Inorganic Nanocomposite Materials, Chem. Mater., 2001, 13, 3151-3168.10.1021/cm011039lSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Saad B., Chong C.C., Ali A.S.M., Bari M.F., Rahman I.A., Mohamad N., Saleh M.I., Selective removal of heavy metal ions using solgel immobilized and SPE-coated thiacrown ethers, Anal. Chim. Acta., 2006, 555,146-156.10.1016/j.aca.2005.08.070Search in Google Scholar

[13] Khan A., Mahmood F., Khokhar M.Y., Ahmed S., Functionalized sol-gelmaterial for extraction of mercury (II), React. Funct. Polym., 2006, 66, 1014-1020.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2006.01.009Search in Google Scholar

[14] Li F., Du P., Chen W., Zhang S.S., Preparation of silica-supported porous sorbent for heavy metal ions removal in wastewater treatment by organic-inorganic hybridization combined with sucrose and polyethylene glycol imprinting, Anal. Chim. Acta., 2007, 585, 211-218.10.1016/j.aca.2006.12.047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Yoshitake H., Yokoi T., Tatsumi T., Adsorption Behavior of Arsenate at Transition Metal Cations Captured by Amino-Functionalized Mesoporous Silicas, Chem. Mater., 2003, 15, 1713-1721.10.1021/cm0218007Search in Google Scholar

[16] Knowles G.P., Delaney S.W., Chaffee A.L. Diethylenetriamine[propyl(silyl)]-Functionalized (DT) Mesoporous Silicas as CO2 Adsorbents, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2006, 45, 2626-2633.10.1021/ie050589gSearch in Google Scholar

[17] Pandya P.H., Jasra R.V., NewalkarB.L., Bhatt P.N., Studies on the activity and stability of immobilized α-amylase in ordered mesoporous silicas, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2005, 77, 67-77.10.1016/j.micromeso.2004.08.018Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang X.G., Chan J.C.C., Tseng Y.H., Cheng S., Synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity of ordered SBA-15 materials containing high loading of diamine functional groups, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2006, 95, 57-65.10.1016/j.micromeso.2006.05.003Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ossai C., Raghavan N., Nanostructure And Nanomaterial Characterization, Growth Mechanisms, And Applications, Nanotechnology Reviews, 2018, 7, 209-231.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0156Search in Google Scholar

[20] Misra R.K., Jain S.K., Khatri P.K., Iminodiacetic acid functionalized cation exchange resin for adsorptive removal of Cr(VI), Cd(II), Ni(II) and Pb(II) from their aqueous solutions, J. Hazard. Mater., 2011, 18, 1508-1512.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.077Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Kresge C.T., Leonowicz M.E., Roth W.J., Vartuli J.C., Beck J.S., Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid-crystal template mechanism, Nat., 1992, 359, 710-712.10.1038/359710a0Search in Google Scholar

[22] Masuda Y., Kugimiya S., Kawachi Y., Kato K., Interparticle mesoporous silica as an effective support for enzyme immobilisation, RSC Adv., 2013, 4, 3573-3580.10.1039/C3RA46122JSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Shieh F.K., Hsiao C.T., Kao H.M., Sue Y.C., Lin K.W.,Wu C.C., Chen X.H., Wan L., Hsu M.H., HwuJ.R., Tsung C.K., Wu K.C.W., Size-adjustable annular ring-functionalized mesoporous silica as effective and selective adsorbents for heavy metal ions, RSC Adv., 2013, 3, 25686-25689.10.1039/c3ra45016cSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Anwar A., Kanwal Q., Akbar S., et al., Synthesis And Characterization Of Pure And Nanosized Hydroxyapatite Bioceramics, Nanotechnology Reviews, 2017, 6, 149-157.10.1515/ntrev-2016-0020Search in Google Scholar

[25] Boissière C., Lee A.V.D., Mansouri A.E., Larbot A., Prouzet E., A double step synthesis of mesoporous micrometric spherical MSU-X silica particles, Chem. Commun., 1999, 20, 2047-2048.10.1039/a906509aSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Rao G.V.R., López G.P., Bravo J., PhamH., Datye A.K., Xu H.F.,Ward T.L., Monodisperse Mesoporous Silica Microspheres Formed by Evaporation-Induced Self Assembly of Surfactant Templates in Aerosols, Adv. Mater., 2002, 14, 1301-1304.10.1002/1521-4095(20020916)14:18<1301::AID-ADMA1301>3.0.CO;2-TSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Lind A., Hohenesche C.D.F.V., Smått J.H., Lindén M., Unger K.K., Spherical silica agglomerates possessing hierarchical porosity prepared by spray drying of MCM-41 and MCM-48 Nanospheres, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2003, 66, 219-227.10.1016/j.micromeso.2003.09.011Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zhao B.B., Zhang Y., Tang T., Wang F.Y., Li T., LuQ.Y., Preparation of high-purity monodisperse silica microspheres by the sol-gel method coupled with polymerization-induced colloid, Aggregation. Particuology, 2015, 22, 177-184.10.1016/j.partic.2014.08.005Search in Google Scholar

[29] Kailasam K., Müller K., Physico-chemical characterization of MCM-41 silica spheres made by the pseudomorphic route and grafted with octadecyl chains, J. Chromatogr. A, 2008, 1191, 125-13510.1016/j.chroma.2008.02.026Search in Google Scholar

[30] Petitto C., Galarneau A., Driole M.F., Chiche B., Alonso B., Renzo F.D., Fajula F., Synthesis of Discrete Micrometer-Sized Spherical Particles of MCM-48, Chem. Mater.,2005, 17, 2120-2130.10.1021/cm050068jSearch in Google Scholar

[31] Liu X.B., Du Y., Guo Z., Gunasekaran S., Ching C.B., Chen Y., Leong S.S.J., Yang Y.H., Monodispersed MCM-41 large particles by modified pseudomorphic transformation:Direct diamine functionalization and application in protein bioseparation, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat., 2009, 122, 114-120.10.1016/j.micromeso.2009.02.023Search in Google Scholar

[32] Lu Y., Lin Q., Ren W., Zhang Y., Investigation on the preparation and properties of low-dielectric ethylene-vinyl acetate rubber / mesoporous silica composites., J. Polym. Res.,2015, 22: 56.10.1007/s10965-015-0694-6Search in Google Scholar

[33] Galarneau A., Iapichella J., Bonhomme K., Renzo F.D., Kooyman P., Terasaki O., Fajula F., Controlling the Morphology of Mesostructured Silicas by Pseudomorphic Transformation: A Route Towards Applications, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2010, 16, 1657-1667.10.1002/adfm.200500825Search in Google Scholar

[34] Shahbazi A., Younesi H., Badiei A., Functionalized SBA-15 mesoporous silica by melamine-based dendrimer amines for adsorptive characteristics of Pb(II), Cu(II) and Cd(II) heavy metal ions in batch and fixed bed column, Chem. Eng. J., 2011, 168, 505-518.10.1016/j.cej.2010.11.053Search in Google Scholar

[35] Benhamou A., Baudu M., Derriche Z., Basly J.P., Aqueous heavy metals removal on amine-functionalized Si-MCM-41 and Si-MCM-48, J. Hazard. Mater., 2009, 171, 1001-1008.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.06.106Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zhao Y.G., Li J.X., Zhang S.W., Wang X.K., Amidoxime-functionalized magnetic mesoporous silica for selective sorption of U(VI), RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 32710-32717.10.1039/C4RA05128ASearch in Google Scholar

[37] Pereira A.S., Ferreira G., Caetano L., Martines M.A.U., Padilha P.M., Santos A., Castro G.R., Preconcentration and determination of Cu(II) in a fresh water sample using modified silica gel as a solid-phase extraction adsorbent, J. Hazard. Mater., 2010, 175, 399-403.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 Y. Lin et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview