Abstract

Both selenium and reduced graphene oxide have low specific capacitance due to their chemical nature. Nevertheless, their specific capacitance could be enhanced by hybridizing Se nanomaterials with reduced graphene oxide via formation of electrochemical double layer at their interfacial area. Therefore, novel Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite was successfully synthesized by template free hot reflux route starting with graphene oxide and selenium dichloride. The composite of rGO decorated by Se-nanorods is characterized using X-ray diffractometry (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and nitrogen adsorption– desorption. The unique architecture of the composite exhibits high specific capacitance of 390 F/ g at 5 mV/s scan rate in 1.0 M KOH solution with ~ 90% cyclic stability after 5000 cycles making it very promising electrode material for supercapacitor applications.

1 Introduction

To overcome some of the limitations of batteries, supercapacitors have been introduced as the next generation energy storage devices [1]. Supercapacitors have various advantages over conventional batteries such as high power density, high charge/discharge rates and long cycle life [2, 3, 4, 5]. Supercapacitors can be categories according to their charge storage mechanism into electrical double layer capacitors (EDLCs) and pseudocapacitor [6]. Various carbonaceous materials such as carbon nanofibers, carbon nanotubes, activated carbon, and graphene have been used for supercapacitor applications. Among these materials, graphene is one of the most promising candidate for supercapacitors, as graphene offer outstanding properties like large surface area (~2700 m2/ g), high carrier mobility, and high thermal and electric conductivity [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. As a result, high theoretical capacitance has been observed whenfull area of single layer graphene is exploited [13, 14, 15, 16].

However, very low capacitance have been observed when graphene is utilized into the electrode film through different techniques, as the graphene layers stacked and aggregated, resulting in reduced chances of electrolyte access to the full surface [17, 18, 19, 20]. Therefore, several approaches are suggested to improve the capacitive performance of graphene-based electrode including surface and morphology modifications, introducing defects and doping [21, 22, 23, 24, 25].

In the search for suitable electrode materials, selenium, an indirect bandgap semiconductor, is promising candidate [26, 27, 28]. Selenium containing materials such as MoSe2 [29], NiSe2 [30], CuSe2 [31], WSe2 [32] and MnSe2 [33] are widely used in many applications, due to their proven properties and recent studies revealed that selenium with nanomorphology can enhance capacitive performance [33, 34]. Hence, the inspiring results of selenium and graphene based nanomaterials motivated this study of the synthesis of selenium incorporated graphene electrode materials.

To date, there are no reported investigations on the synthesis and applications of Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. Herein, we establish template free synthesis of Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite. More interestingly, no additional steps i.e. purification or calcination processes were required. The template free synthesis of Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite showedhigh specific capacitance value of 390 F/ g at 5 mV/ s scan rate with ~90 % retention after 5000 cycles.

The electrochemical investigation was carried out in 1.0 M KOH solution, due to its low resistivity, low corrosive and poisoning effect along with high stability, high ionic conductivity and mobility of OH− ions compared to acidic electrolytes [35, 36, 37].

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis and characterizations of Se-nanorods / rGO nanocomposite

GO was synthesized using modified Hummers’ method following previously reported method [2]. Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite was prepared with heat reflux technique. Briefly, equal amount (0.2 g) of GO and SeCl4 were dispersed in 200 ml of distilled water under vigorous stirring and then sonicated for 40 min. The mixture was then transferred to 500 ml round bottom flask. Subsequently, 0.2 ml of hydrazine hydrate was added and refluxed at 150 ∘C for 10 h. Finally, the Se-nanorods/rGO product was collected by filtration, washing and drying. The Crystallographic structure of the final product was characterized by XRD (Rigaku, Japan) over 2θ range of 10 to 70∘. Raman and FT-IR analysis were performed by using DXR- Raman microscope (Thermo Scientific) and spectrum 400 FT-IR spectrometer (PerkinElmer). The BET surface areas and pore size distributions were analyzed using ASAB 2020 (Micromeritics Instruments). The morphological characterizations were examined by FESEM (Hitachi S-7400) and TEM /HRTEM (JEOL JEM-2200FS) coupled with rapid EDAX.

3 Results and discussion

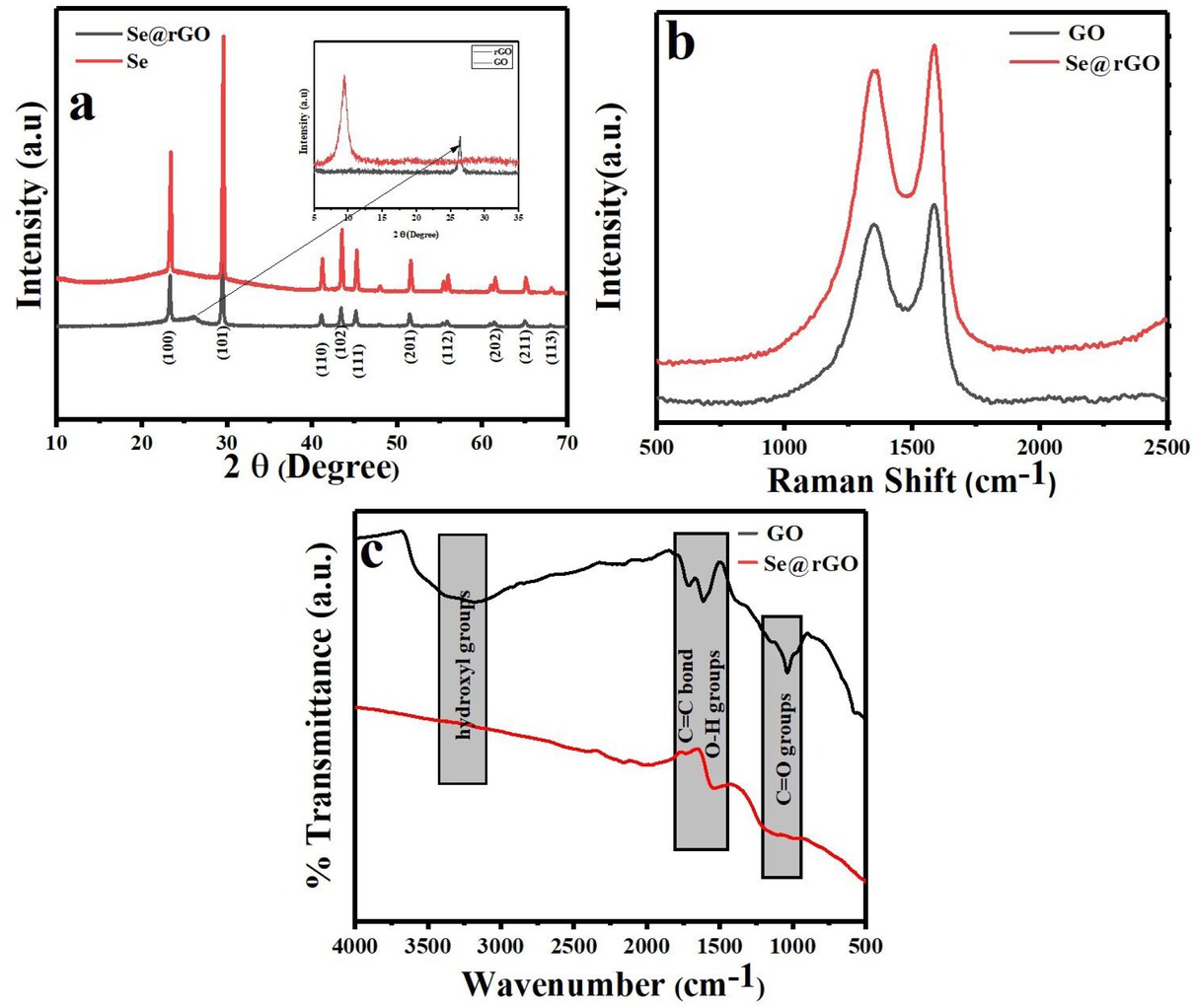

The XRD analysis was carried to reveal the crystalline structure of GO, rGO, Se and Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite and the diffraction pattern shown in Figure 1(a). As shown in Figure 1(a, inset) the XRD pattern of GO displayed a diffraction peak at 2θ ~ 10.5∘, revealing the intercalation of oxygen containing functional groups on the graphite sheets [38, 39]. For rGO, the diffraction peak at 10.5∘ completely disappeared after the reduction and replaced by a new diffraction peak at 2θ ~ 22.5∘ which confirms the reduction of GO [40]. The XRD pattern of as synthesized Senanorods / rGO nanocomposite showing a series of diffraction peeks at 23.7∘, 29.8∘, 41.4∘, 43.9∘, 45.5∘, 51.8∘, 56.3∘, 61.9∘, 65.2∘ and 68.6∘ corresponded to the (100), (101), (110), (102), (111), (201), (112), (202), (211) and (113) plans of the trigonal phase of metallic selenium correspond very well with the standard JCPDS data (JCPDS No. 06-0362) of metallic selenium with lattice parameters a and c equal to 4.357 and 4.945 Å, respectively. Moreover, broad peak appears at 2θ ~ 27.5∘ confirms the reduction of GO in a composite [41].

(a) XRD pattern of pristine Se, synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite and (inset) XRD pattern of GO and rGO, (b) Raman and (c) FT-IR pattern for the GO and synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite

The reduction of GO was further investigated by Raman spectroscopy. Typically, the Raman spectra of carbon based materials displays two characteristic bands positioned at 1342 at 1581 cm−1 assigned to the D (the symmetric A1g mode) and G bands (E2g mode of sp2 carbon atoms), respectively [42]. The reduction of GO leads to a change in the intensity ratio of the D and G band (ID/IG). As shown in Figure 1(b) the intensity ratio of D and G band of the nanocomposite are increased notably from 0.87 for GO to 0.92 for the nanocomposite, indicating reduction of GO [43, 44, 45, 46]. The increase of ID/IG ratio are very commonly observed in GO chemical reduction and reported frequently [43, 44].

The reduction of GO was also confirmed through FT-IR spectroscopy. The GO exhibits number of absorption bands located at 3440, 1631, 1384 and 1118 cm−1, associated with stretching vibration of hydroxyl groups, aromatic C=C bond, O–H groups and stretching vibrations of C=O groups, respectively [47, 48, 49]. As shown in Figure 1(c). After the reduction to rGO, the concentration of oxygen functional groups is considerably lower than that of GO, which further confirmed the reduction of GO.

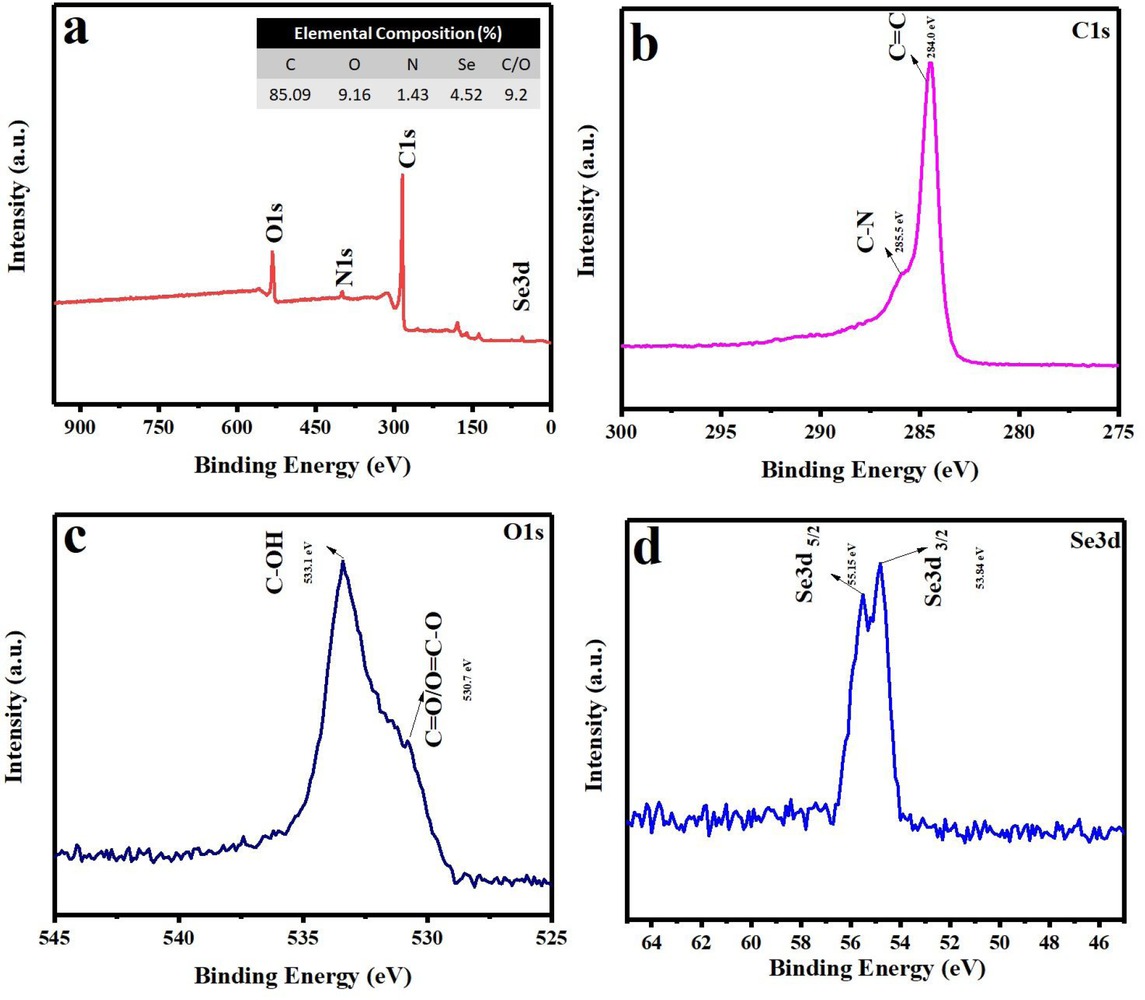

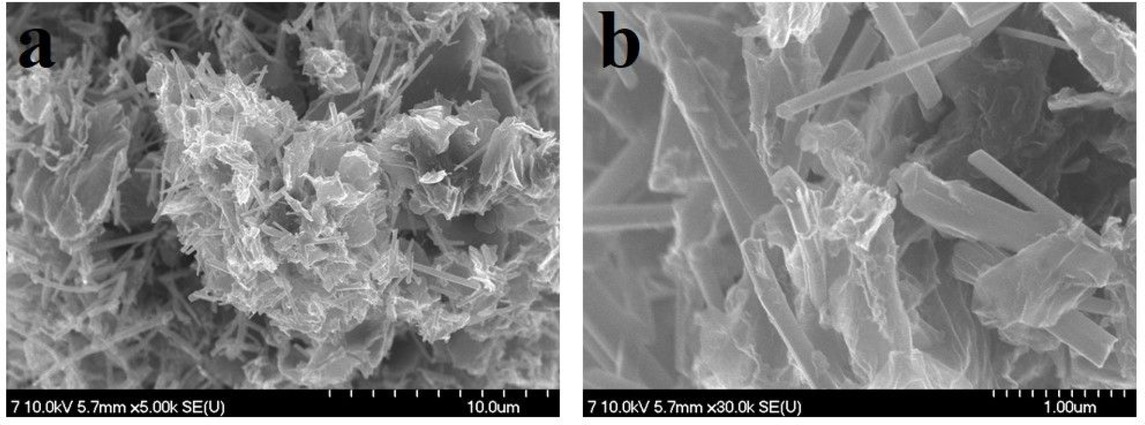

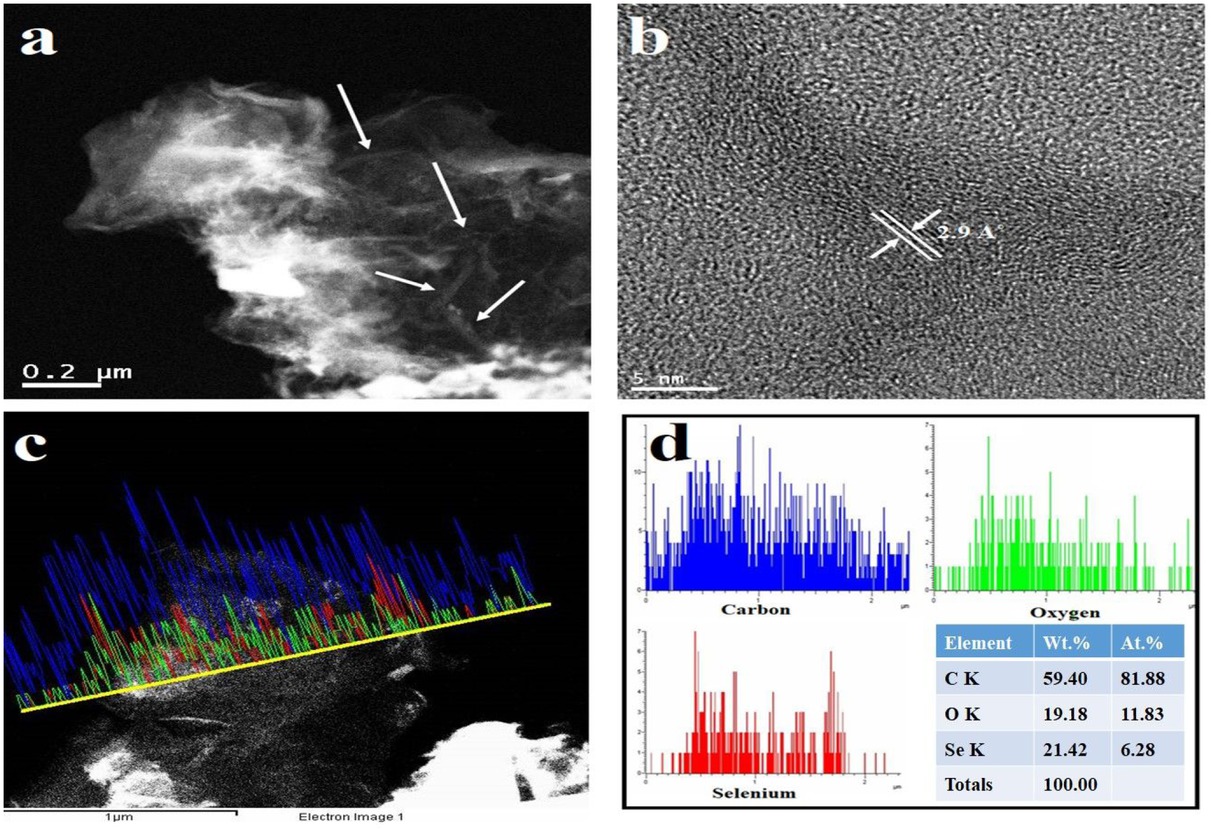

The GO reduction level and elemental composition of Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite was also investigated by XPS measurements. The XPS survey spectrum (Figure 2(a)) shows the existence of C1s (~284.5), O1s (~533.2), N1s (~399.1) and Se3d (~53.4) peaks with the elemental composition of 85.09%, 9.16%, 1.43% and 4.25%, as shown in the inset of Figure 2a, respectively. Low content of the oxygen-containing functional groups (9.16%) and high C/O ratio gave a clear indication of the reduction achieved. The C1s spectrum of the Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite (Figure 2(b))was de-convoluted with two peaks at 284.0eV and 285.5 eV, corresponding to the non-oxygenated ring (C=C) and C-N, respectively. The O1s spectrum of the nanocomposite (Figure 2(c)) was fitted into two peaks at 530.0 eV and 533.1 eV, corresponding to the different oxygen functionalities such as C=O/O=C-O and C-OH, respectively; however, the Se3d spectrum of the nanocomposite fitted very well at binding energies of 53.15 eV and 55.15 eV for Se 3d3/2 and Se 3d5/2, respectively (Figure 2(d)). Figure 3(a and b), shows the morphology of the Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite. As presented in Figure 3(a), the typical crumpled-like features of graphene are faintly visible as densely packed selenium nanorods are anchored on the graphene surface, indicting the strong physical bonding between the selenium nanorods and graphene sheets. Furthermore, the high-resolution FESEM image (Figure 3(b)) reveals the structure of selenium nanorods arrays as having average length and diameter of ~1.0 μm and ~120 nm with aspect ratio of 8. Figure 4(a) and 4(b) show the characteristic TEM and HR-TEM images of the Senanorods/rGO nanocomposite where Se nanorods are randomly distributed over the 2D rGO sheets (marked by arrows). Furthermore, lattice fringes with 2.9 Å spacing are clearly observed in the HRTEM image (Figure 4(b)), which is consistent with the (101) crystalline plane of trigonal selenium. The EDX line mapping was also carried to confirm the nanocomposite purity and the Se loading, which was found to be 21.42 wt.%. The atomic and weight percentage of carbon, oxygen and selenium are summarized in Figure 4(d). The concentration profile of C, O and Se signals are shown in panel D in Figure 4(d). EDX scanning across the randomly selected line reveals that the profiles of C have a broad spectrum and high intensity than oxygen and Se while the peaks for Se are only noticeable at the nanorods regions suggest the random distribution of selenium nanorods on the graphene sheets. However, the noticeable oxygen could be either from a thin sporadic layer of SeO on the surface of metallic nanorods or the oxygen presence in the rGO.

(a) XPS spectra survey and (inset) elemental composition of synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite, (b) C1s spectra, (c) O1s spectra and (d) Se3d spectra of synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite

(a) low and (b) high magnification FE-SEM images of the synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite

(a) TEM and (b) HR-TEM images, (c) Line EDS mapping and (d) corresponding concentration profile and elemental percentage of the synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite

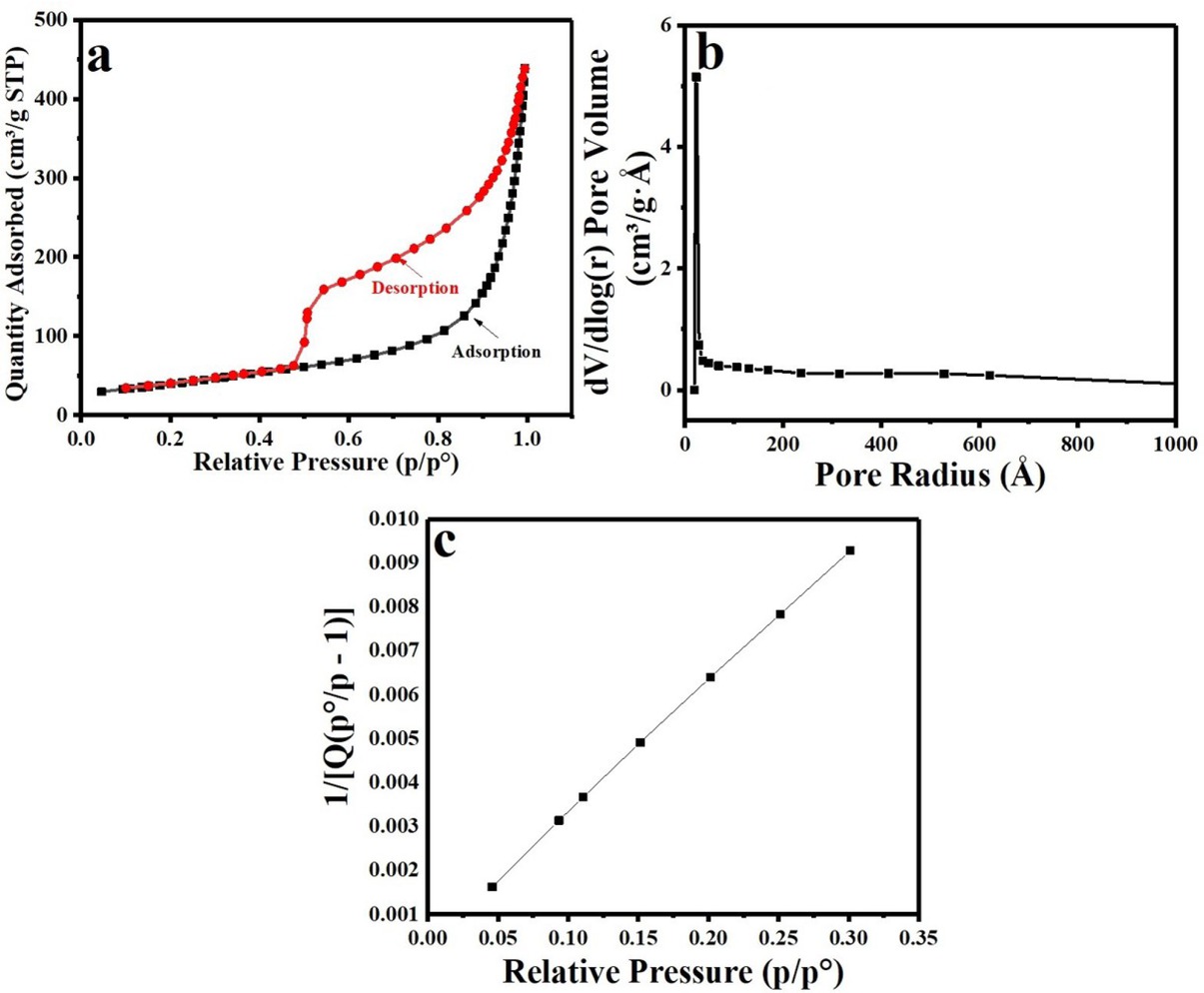

The surface area, porosity and pore size distribution of the nanocomposite were examined by the nitrogen-adsorption measurements and the characteristic N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm and the corresponding BJH pore size distribution plot are shown in Figure 5. The adsorption –desorption isotherm shows a hysteresis loops consistent with type IV isotherm indicating the mesoporous structure of the nanocomposite, Figure 5(a). Furthermore, the nanocomposite has high BET surface areas of 144.10 m2/ g and average pore size of 5 Åas determined by BJH method, Figure 5(a). All the corresponding parameters of BET and BJH analysis are listed in the inset of Figure 5(b).

(a) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm and (b) BJH pore size distribution of the synthesized Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite

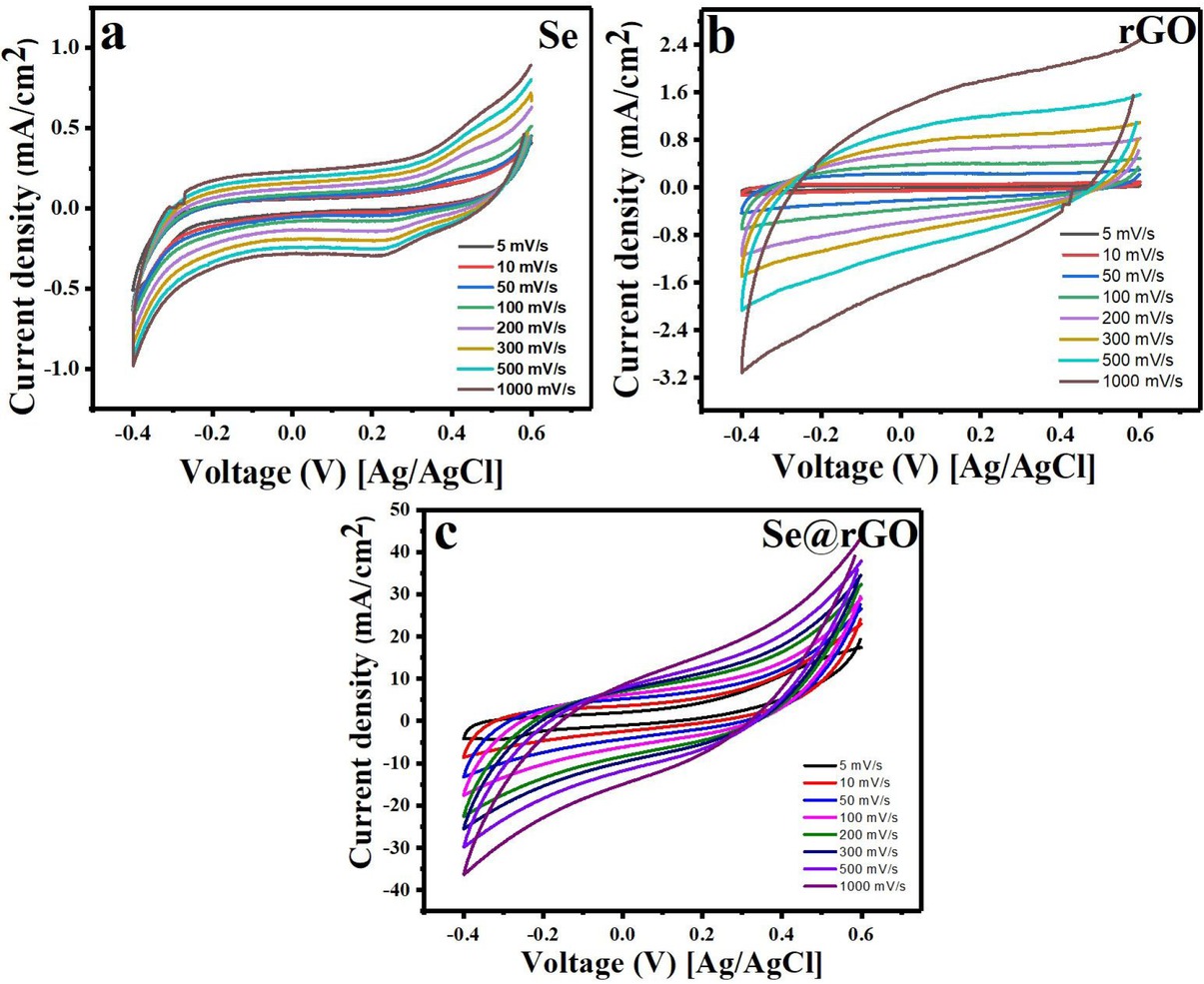

The electrochemical investigation of pristine Se, rGO and Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite were carried out in 1.0 M KOH solution using three-electrode electrochemical system (VersaSTAT 4, USA). Relative CV measurements of investigated electrodes at various scan rates over the potential window of −0.4 to 0.6 V are shown in Figure 6 (a-c). The specific capacitance (Cs) were calculated as,

Cyclic voltammograms of synthesized electrode (a) Se, (b) rGO and (c) Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite in 1M KOH solution at different scan rates (5 to 1000 mV/s)

Here, Cs is the specific capacitance, m is the active mass of nanocomposite, (Vb − Va) is potential window and I (s) is the voltammetric current. Figure 6(a and b) represents the CV curves of the pristine Se and rGO electrodes at different scan rates (5 to 1000 mV/s) in 1.0 M KOH aqueous solution. As shown, the CV curves of the selenium electrode (Figure 6(a)) exhibit non-rectangular shape, reflecting faradic capacitance behavior. On the other hand, the CV curve of pristine rGO electrode (Figure 6(b)) at different scan rates exhibits a quasi-rectangular shape without any redox peaks, which confirmed the electrical double layer behavior of rGO. Further, as shown in Figure 6(a and b), the integrated area/ current density increases with the scan rate; however, the shape of the CV curve was little distorted at high scan rate (1000 mV/s), indicating poor reversibility. Moreover, the current response from the pristine selenium and rGO electrode is very low, showed negligible specific capacitance. Interestingly, the CV curve of the nanocomposite (Figure 6(c)) shows a relatively rectangular without any obvious redox peaks, indicating that the electrical double-layer capacitance is dominated by non-faradic mechanism, instead of a pure pseudo capacitance, also the profile of the CV curve is still well retained even at high scan rate (1000 mV/s).

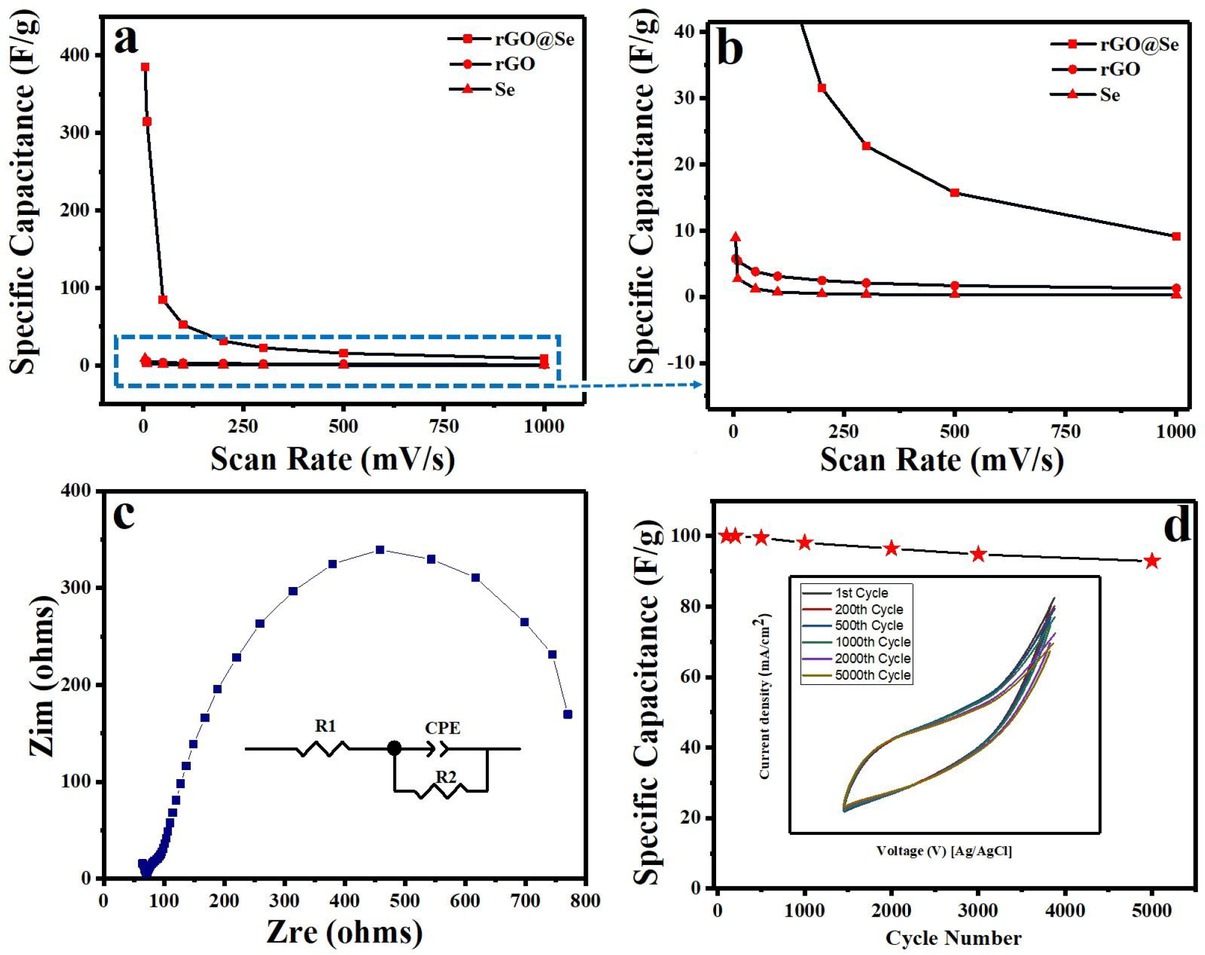

Further, the integrated area/ current density is higher than pristine Se and rGO electrodes, indicating the better electrochemical performance. However, the corresponding specific capacitance of Se, rGO and Senanorods/rGO nanocomposite were 8.9, 5.7 and 390 Fg−1, respectively. The relationship between the specific capacitance and the scan rate of pristine Se, rGO and Se-rGO nanocomposite shown in Figure 7(a&b). As shown the value significant decrease in capacitance with increase of scanning rate. This phenomenon is expected as at lower scan rate more time is available for diffusion of H+ ions from the electrolyte to the inner active sites of the electrode leading to high capacitance [2]. Therefore, the CV results confirms that Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite have high capacitance with slight dependence on scan rate, while pristine Se and rGO have very low specific capacitance with good rate capability.

(a) Effect of scan rate on specific capacitance, (b) large scale for the marked area, (c) Nyquist plot (inset) corresponding equivalent circuit diagram, and (d) Specific capacitance retention as a function of cycle number (inset) corresponding cycle numbers

The interface charge transport properties of the nanocomposite were characterized by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Figure 7(c) shows the representative Nyquist plot for the nanocomposite in 1.0 M KOH solution. It can be seen that, the EIS curve consists of a single semi-circle in higher frequency region, implying there is only one type of interface and indicates good charge transfer performance of the electrode. Based on the representative equivalent circuit (inset Figure 7(c)) the value of Rp (the charge transfer resistance) were 198.6. The constant phase element (CPE) is one of the most common circuit elements, used to describe the capacitive performance of the electrode. When the value of CPE is equal to 1, the CPE element resembles an ideal capacitor without defects and grain boundaries [50, 51, 52]. Interestingly, the fitting data shows that the CPE value of the nanocomposite is close to 1. Therefore, the synthesized nanocomposite can be used as supercapacitors electrode material.

The electrochemical stability is an important characteristic for the application of electrode materials. Therefore, electrochemical stability test was performed over 5000 consecutive cycles and the results are shown in Figure 7(d). As shown, the electrochemical stability of the nanocomposite electrode is quite good with ~ 90% capacitance retention after 5000 cycles. It is obvious that the surface of electrode was turned inactive due to surface morphology change and compact structure after 5000 cycles. Moreover, the corresponding CV curves reveal no noticeable distortion as shown in inset of Figure 7(d). The high electrochemical performance of Se-nanorods/rGO nanocomposite is attributed to the following:

The unique nanoroad morphology of selenium is beneficial for the electron transfer reaction.

The 2D conductive structure of graphene reduces the overall resistance, improves the electrical conductivity, and provides high surface area and active sites for the electron transfer.

The nanocomposite of selenium nanorods with the conductive graphene allows the effective intercalation/deintercalation of H+ ions from the electrolyte.

Furthermore, the synergetic effect of the selenium nanorods and graphene enhance the charge storage capacity of the nanocomposite through both faradaic and non-faradaic energy-storage processes.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, Se-nanorods decorated rGO nanocomposite-based electrode material was synthesized by facile heat reflux technique without any template. The CV profile of the synthesized nanocomposite-based electrode confirming that the electrical double-layer capacitance was dominated by non-faradic mechanism, instead of a pure pseudo capacitance. Furthermore, compared to pristine Se and rGO, the synthesized nanocomposite-based electrode exhibited high specific capacitance of 390 Fg−1 with ~ 90% capacitance retention after 5000 cycles. These results demonstrate that the synthesized nanocomposite is very promising candidate for energy storage devices.

Acknowledgement

The publication of this article was funded by the Qatar National Library.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

[1] Rao A. M., Energy and our future: a perspective from the Clemson Nanomaterials Center, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2015, 4, 479-484.10.1515/ntrev-2015-0046Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ghouri Z. K., Barakat N. A. M., Alam A.-M., Alsoufi M. S., Bawazeer T. M., Mohamed A. F. and Kim H. Y., Synthesis and characterization of Nitrogen-doped &CaCO3-decorated reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for electrochemical supercapacitors, Electrochim. Acta, 2015, 184, 193-202.10.1016/j.electacta.2015.10.069Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ghouri Z. K., Akhtar M. S., Zahoor A., Barakat N. A., Han W., Park M., Pant B., Saud P. S., Lee C. H. and Kim H. Y., High-efficiency super capacitors based on hetero-structured α-MnO2 nanorods, J. Alloys Compd., 2015, 642, 210-215.10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.04.082Search in Google Scholar

[4] Ghouri Z. K., Barakat N. A., Alam A.-M., Park M., Han T. H. and Kim H. Y., Facile synthesis of Fe/CeO2-doped CNFs and their capacitance behavior, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci, 2015, 10, 2064-2071.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Li Z., Xu K. and Pan Y., Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2019, 8, 35-49.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0004Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wang H., Song Y., Ye X., Wang H., Liu W. and Yan L., Asymmetric Supercapacitors Assembled by Dual Spinel Ferrites@ Graphene Nanocomposites as Electrodes, Appl. Energy Mater., 2018,10.1021/acsaem.8b00433Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhan C., Pham T. A., Cerón M. R., Campbell P. G., Vedharathinam V., Otani M., Jiang D.-e., Biener J., Wood B. C. and Biener M., Origins and Implications of Interfacial Capacitance Enhancements in C60-Modified Graphene Supercapacitors, ACS Appl. Mater., 2018, 10, 36860-36865.10.1021/acsami.8b10349Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Ghouri Z. K., Barakat N. A., Saud P. S., Park M., Kim B.-S. and Kim H. Y., Supercapacitors based on ternary nanocomposite of TiO 2 &Pt@ graphenes, J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron., 2016, 27, 3894-3900.10.1007/s10854-015-4239-xSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Liu H. and Liu Y., Controlled chemical synthesis in CVD graphene, Physical Sciences Reviews, 2017, 2,10.1515/9783110284645-005Search in Google Scholar

[10] Das S., Ghosh C. K., Sarkar C. K. and Roy S., Facile synthesis of multi-layer graphene by electrochemical exfoliation using organic solvent, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018,10.1515/ntrev-2018-0094Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yu H., Chu C. and Chu P. K., Self-assembly and enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity of reduced graphene oxide-Bi2WO6 photocatalysts, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2017, 6, 505-516.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0153Search in Google Scholar

[12] Cruz-Silva R., Endo M. and Terrones M., Graphene oxide films, fibers, and membranes, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2016, 5, 377-391.10.1515/ntrev-2015-0041Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li Q., Mahmood N., Zhu J., Hou Y. and Sun S., Graphene and its composites with nanoparticles for electrochemical energy applications, Nano Today, 2014, 9, 668-683.10.1016/j.nantod.2014.09.002Search in Google Scholar

[14] Shao Y., El-Kady M. F., Wang L. J., Zhang Q., Li Y., Wang H., Mousavi M. F. and Kaner R. B., Graphene-based materials for flexible supercapacitors, Chem. Soc. Rev., 2015, 44, 3639-3665.10.1039/C4CS00316KSearch in Google Scholar

[15] Rao C. e. N. e. R., Sood A. e. K., Subrahmanyam K. e. S. and Govindaraj A., Graphene: the new two-dimensional nanomaterial, Angew. Chem., 2009, 48, 7752-7777.10.1002/anie.200901678Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Xia J., Chen F., Li J. and Tao N., Measurement of the quantum capacitance of graphene, Nat. Nanotechnol., 2009, 4, 505.10.1038/nnano.2009.177Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Mensing J. P., Poochai C., Kerdpocha S., Sriprachuabwong C., Wisitsoraat A. and Tuantranont A., Advances in research on 2D and 3D graphene-based supercapacitors, Adv. in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2017, 8, 033001.10.1088/2043-6254/aa7214Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jung S., Kim H., Lee J., Jeong G., Kim H., Park J. and Park H., Bio-Inspired Catecholamine-Derived Surface Modifier for Graphene-Based Organic Solar Cells, Appl. Energy Mater., 2018, 1, 6463-6468.10.1021/acsaem.8b01396Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bandaru P. R., Yamada H., Narayanan R. and Hoefer M., The role of defects and dimensionality in influencing the charge, capacitance, and energy storage of graphene and 2D materials, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2017, 6, 421-433.10.1515/ntrev-2016-0099Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wang Y., Shi Z., Huang Y., Ma Y., Wang C., Chen M. and Chen Y., Supercapacitor devices based on graphene materials, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2009, 113, 13103-13107.10.1021/jp902214fSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Stankovich S., Piner R. D., Chen X., Wu N., Nguyen S. T. and Ruoff R. S., Stable aqueous dispersions of graphitic nanoplatelets via the reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide in the presence of poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate), J. Mater. Chem., 2006, 16, 155-158.10.1039/B512799HSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang L. L., Zhao X., Ji H., Stoller M. D., Lai L., Murali S., Mc-donnell S., Cleveger B., Wallace R. M. and Ruoff R. S., Nitrogen doping of graphene and its effect on quantum capacitance, and a new insight on the enhanced capacitance of N-doped carbon, Energy Environ. Sci, 2012, 5, 9618-9625.10.1039/c2ee23442dSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Chen J., Han Y., Kong X., Deng X., Park H. J., Guo Y., Jin S., Qi Z., Lee Z. and Qiao Z., The Origin of Improved Electrical Double-Layer Capacitance by Inclusion of Topological Defects and Dopants in Graphene for Supercapacitors, Angew. Chem., 2016, 55, 13822-13827.10.1002/anie.201605926Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Cuentas-Gallegos A., Rayón-López N., Mejía L., Vidales H. V., Miranda-Hernández M., Robles M. and Muńiz-Soria J., Porosity and Surface Modifications on Carbon Materials for Capacitance Improvement, Open Mater. Sci., 2006, 3,10.1515/mesbi-2016-0007Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ossai C. I. and Raghavan N., Nanostructure and nanomaterial characterization, growth mechanisms, and applications, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018, 7, 209-231.10.1515/ntrev-2017-0156Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chang A., Zhang C., Yu Y., Yu Y. and Zhang B., Plasma-Assisted Synthesis of NiSe2 Ultrathin Porous Nanosheets with Selenium Vacancies for Supercapacitor, ACS Appl. Mater., 2018, 10, 41861-41865.10.1021/acsami.8b16072Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Yin H., Xu Z., Bao H., Bai J. and Zheng Y., Single crystal trigonal selenium nanoplates converted from selenium nanoparticles, Chem. Lett., 2004, 34, 122-123.10.1246/cl.2005.122Search in Google Scholar

[28] Cao X., Xie Y., Zhang S. and Li F., Ultra-Thin Trigonal Selenium Nanoribbons Developed from Series-Wound Beads, Adv. Mater., 2004, 16, 649-653.10.1002/adma.200306317Search in Google Scholar

[29] Balasingam S. K., Lee J. S. and Jun Y., Molybdenum diselenide/reduced graphene oxide based hybrid nanosheets for supercapacitor applications, Dalton Trans., 2016, 45, 9646-9653.10.1039/C6DT00449KSearch in Google Scholar

[30] Arul N. S. and Han J. I., Facile hydrothermal synthesis of hexapodlike two dimensional dichalcogenide NiSe2 for supercapacitor, Mater. Lett., 2016, 181, 345-349.10.1016/j.matlet.2016.06.065Search in Google Scholar

[31] Pazhamalai P., Krishnamoorthy K. and Kim S. J., Hierarchical copper selenide nanoneedles grown on copper foil as a binder free electrode for supercapacitors, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, 2016, 41, 14830-14835.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.05.157Search in Google Scholar

[32] Chakravarty D. and Late D. J., Microwave and hydrothermal syntheses of WSe 2 micro/nanorods and their application in super-capacitors, RSC Adv., 2015, 5, 21700-21709.10.1039/C4RA12599ASearch in Google Scholar

[33] Balamuralitharan B., Karthick S., Balasingam S. K., Hemalatha K., Selvam S., Raj J. A., Prabakar K., Jun Y. and Kim H. J., Hybrid reduced graphene oxide/manganese diselenide cubes: a new electrode material for supercapacitors, Energy Technol., 2017, 5, 1953-1962.10.1002/ente.201700097Search in Google Scholar

[34] Shah C. P., Singh K. K., Kumar M. and Bajaj P. N., Vinyl monomers-induced synthesis of polyvinyl alcohol-stabilized selenium nanoparticles, Mater. Res. Bull., 2010, 45, 56-62.10.1016/j.materresbull.2009.09.001Search in Google Scholar

[35] Biswas P., Nodasaka Y. and Enyo M., Electrocatalytic activities of graphite-supported platinum electrodes for methanol electrooxidation, J. Appl. Electrochem., 1996, 26, 30-35.10.1007/BF00248185Search in Google Scholar

[36] Jafarian M., Moghaddam R., Mahjani M. and Gobal F., Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol on a Ni–Cu alloy in alkaline medium, J. Appl. Electrochem., 2006, 36, 913-918.10.1007/s10800-006-9155-6Search in Google Scholar

[37] Danaee I., Jafarian M., Forouzandeh F., Gobal F. and Mahjani M., Electrocatalytic oxidation of methanol on Ni and NiCu alloy modified glassy carbon electrode, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy, 2008, 33, 4367-4376.10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.05.075Search in Google Scholar

[38] Sookhakian M., Amin Y. and Basirun W., Hierarchically ordered macro-mesoporous ZnS microsphere with reduced graphene oxide supporter for a highly efficient photodegradation of methylene blue, App. Surf. Sci., 2013, 283, 668-677.10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.06.162Search in Google Scholar

[39] Xu J., Gai S., He F., Niu N., Gao P., Chen Y. and Yang P., Reduced graphene oxide/Ni 1- x Co x Al-layered double hydroxide composites: preparation and high supercapacitor performance, Dalton Trans., 2014, 43, 11667-11675.10.1039/C4DT00686KSearch in Google Scholar

[40] Golsheikh A. M., Huang N., Lim H. and Zakaria R., One-pot sono-chemical synthesis of reduced graphene oxide uniformly decorated with ultrafine silver nanoparticles for non-enzymatic detection of H 2 O 2 and optical detection of mercury ions, RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 36401-36411.10.1039/C4RA05998KSearch in Google Scholar

[41] Hummers W. S., Jr. and Offeman R. E., 1958, 1339-1339.10.1021/ja01539a017Search in Google Scholar

[42] Yang D., Velamakanni A., Bozoklu G., Park S., Stoller M., Piner R. D., Stankovich S., Jung I., Field D. A. and Ventrice Jr C. A., Chemical analysis of graphene oxide films after heat and chemical treatments by X-ray photoelectron and Micro-Raman spectroscopy, Carbon., 2009, 47, 145-152.10.1016/j.carbon.2008.09.045Search in Google Scholar

[43] Stankovich S., Dikin D. A., Piner R. D., Kohlhaas K. A., Kleinhammes A., Jia Y., Wu Y., Nguyen S. T. and Ruoff R. S., Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide, Carbon., 2007, 45, 1558-1565.10.1016/j.carbon.2007.02.034Search in Google Scholar

[44] Bose S., Kuila T., Mishra A. K., Kim N. H. and Lee J. H., Dual role of glycine as a chemical functionalizer and a reducing agent in the preparation of graphene: an environmentally friendly method, J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 9696-9703.10.1039/c2jm00011cSearch in Google Scholar

[45] Wang H., Robinson J. T., Li X. and Dai H., Solvothermal reduction of chemically exfoliated graphene sheets, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 9910-9911.10.1021/ja904251pSearch in Google Scholar

[46] Chua C. K., Ambrosi A. and Pumera M., Graphene oxide reduction by standard industrial reducing agent: thiourea dioxide, J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 11054-11061.10.1039/c2jm16054dSearch in Google Scholar

[47] Wu N., She X., Yang D., Wu X., Su F. and Chen Y., Synthesis of network reduced graphene oxide in polystyrene matrix by a two-step reduction method for superior conductivity of the composite, J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 17254-17261.10.1039/c2jm33114dSearch in Google Scholar

[48] Rana U. and Malik S., Graphene oxide/polyaniline nanostructures: transformation of 2D sheet to 1D nanotube and in situ reduction, Chem. Commun., 2012, 48, 10862-10864.10.1039/c2cc36052gSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Zhang H., Hines D. and Akins D. L., Synthesis of a nanocomposite composed of reduced graphene oxide and gold nanoparticles, Dalton Trans., 2014, 43, 2670-2675.10.1039/C3DT52573BSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Rammelt U. and Reinhard G., On the applicability of a constant phase element (CPE) to the estimation of roughness of solid metal electrodes, Electrochim. Acta, 1990, 35, 1045-1049.10.1016/0013-4686(90)90040-7Search in Google Scholar

[51] Perrier G., De Bettignies R., Berson S., Lemaître N. and Guillerez S., Impedance spectrometry of optimized standard and inverted P3HT-PCBM organic solar cells, Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C., 2012, 101, 210-216.10.1016/j.solmat.2012.01.013Search in Google Scholar

[52] Jorcin J.-B., Orazem M. E., Pébère N. and Tribollet B., CPE analysis by local electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, Electrochim. Acta, 2006, 51, 1473-1479.10.1016/j.electacta.2005.02.128Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Z. Khan Ghouri et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview