Abstract

In the field of low temperature co-fired ceramic (LTCC), it remains a challenge to design the performance of LTCC with low permittivity less than 5. Here, the K2O– B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites are prepared without the preparation of prior glass. Meanwhile, the factors of the CaO content on microstructure, phase structure and properties of the composites are considered systematically. The crystal structure measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) shows that there are quartz and alumina as the crystal phases. The results reveals that the tailoring CaO content benefits sintering densification, low dielectric loss, great mechanical properties and low thermal expansion coefficient. As CaO content increases up to 2.8 wt%, the composites sintered at 850∘C have a dielectric constant of 4.94 and tanδ of 8 × 10−4 at 1 MHz, thermal expansion coefficient (CTE) of 8.5 ppm/∘C, and flexural strength of 150 MPa. As the mass fraction of CaO increases up to 3.2 wt%, the maximum flexural strength of 173MPa is achieved. The above study provides an effective approach for preparing the novel composites as a promising candidate for LTCC applications.

1 Introduction

For light and integrated electron devices in microwave communication, low temperature co-fired ceramic (LTCC) technology has been widely applied due to its superior properties and low cost. In wireless telecommunication and microwave integrated circuits, low permittivity (low for fast signal transmission) and high quality factor (Q) are critical for practical applications. Beyond that, high flexural strength provides outstanding supporting for the electronic packaging. The matched thermal expansion coefficient (CTE) effectively promotes the reliability of the system designs [1, 2]. However, most conventional ceramics materials have a high sintering temperature of over 1000∘C. Attention is therefore focused on the role of glasses because of the effects they reduce the sintering temperature of ceramics materials. There are two approaches to obtaining ceramic composites with the sintering temperature of below 1000∘C [1].

The first approach is to add glasses prepared via high temperature melting technique. For glasses compositions, borosilicate glasses have drawn a lot of attention due to its excellent comprehensive performance. As a promising material, Al2O3 has ϵr of 9.8, making Al2O3 ceramic-filler a potential glass/ceramic candidate. In addition, Al2O3 is chosen due to its high mechanical strength and high surface energy, which is able to provide hydrodynamic lubrication for sintering densification [3]. The typical borosilicate glasses are listed as following: SiO2–B2O3–CaO– MgO [4], ZnO–B2O3–SiO2 [5], CaO–Al2O3–B2O3–SiO2– Na2O–K2O [6], B2O3–Bi2O3–SiO2–ZnO [7], BaO–B2O3– SiO2 [8], K2O–B2O3–SiO2 [9] etc. Qin Xia et al. [9] prepared K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 glass ceramics, showing a high dielectric constant of 6.1 and a heavy dielectric loss of 2×10−3 at 1 MHz. Xianfu Luo et al. [10] reported the properties of CaO–Al2O3–B2O3–SiO2 glass/Al2O3 composite with different CaO contents. They found that an appropriate addition of CaO into CABS glass enhances glass/ceramic density.

However, melting glasses are prepared at high temperature, leading to large energy consumption. And boron oxide (melting point of 450∘C) evaporates rapidly at high temperature, making it difficult for borosilicate glasses to control their composition. Hence, as a novel and low-cost method, another approach is via the glass–ceramic route. Heli Jantunen et al. [11] investigated the possibility of preparing a similar LTCC ceramic without the preparation of prior glass. Xueming Cui et al. [12] reported an effective pre-sintering method to fabricate BaO–TiO2– B2O3–SiO2 glass–ceramic, which was a simple approach that the whole mixed solid oxides were sintered at 750∘C instead of preparing melting glass over 1000∘C. There were few reports about low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2– Al2O3 glass-ceramic prepared via pre-sintering method.

Herein, we propose a novel perspective on the role of CaO, which is significant to develop a low-cost process on account of avoiding melting glass. The effects of CaO content on dielectric properties, thermal expansion coefficient, and flexural strength are presented separately.

2 Experimental procedures

The composites were prepared by the conventional solid-state ceramic route. According to the composition shown in Table 1, the K2CO3, Na2CO3, CaO, Ba(OH)2.8H2O, B2O3, SiO2, Al2O3 (the purity of all the raw materials is 99.9%) with different CaO contents (mass fraction, %) (0.5, 0.9, 1.3, 1.7, 2.1, 2.5, 2.8, 3.2, 3.6) were directly mixed and blended for 4 h by the planetary ball mill. After completely dried off, the powders were sintered at the pre-sintering temperature of 750∘C for 2 h and then we sifted the pre-sintered powders using 100 mesh sieve to guarantee uniform particle size. The uniform powers (about 150 μm) were added into the planetary ball mill at 280 r/min for 6h. Later, the slurry was dried off at 100∘C for 24 h. Then we grinded down the powers by adding Acrylic acid as the binder until we made it uniform and fluid. At the end, the powders were formed via pressing process at 20MPa and the samples were respectively sintered at 850∘C for 2 h.

Composition of different CaO content (mass fraction, wt %)

| Sample | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | B2O3 | K2O | Na2O | BaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 0.5 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A2 | 0.9 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A3 | 1.3 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A4 | 1.7 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A5 | 2.1 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A6 | 2.5 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A7 | 2.8 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A8 | 3.2 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

| A9 | 3.6 | 63 | 23 | 11 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 |

The phase analysis of the samples sintered at 850∘C was carried out by XRD using Cu Kα radiation (Philips X’Pert Pro MPD). The microstructures of the samples were examined via electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Inspect F, UK). X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on an AXIS ULTRA spectrometer (Kratos Analytical Ltd., Japan) using a monochromatic Al source. The densities of the samples were measured using a GF-3000D Density Meter. A network analyzer (Agilent Technologies E5071C, USA) and a temperature chamber (DELTA 9023, Delta Design, USA)were used to measure the microwave dielectric properties. Flexural strengths and TEC values were measured using a CMT6104 microcomputer control electronic universal testing machine and a NETZSCH DIL402PC, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

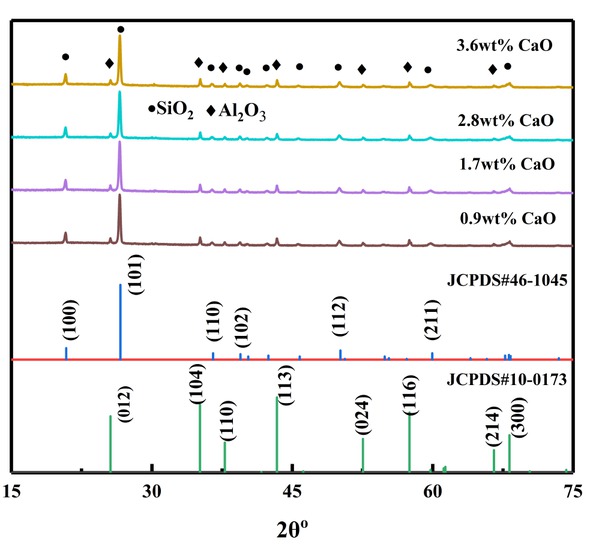

XRD patterns of the composites shown in Figure 1. From XRD results, it can be seen that SiO2 (quartz) is the main crystalline phase, and the additional crystalline phase is Al2O3. As CaO content increases, it has no significant effects on phase structure. However, the intensity of quartz phase slightly decreases. Chung Chiang et al. [13] reported CaO–B2O3–SiO2 system glass–ceramics which only consists of SiO2 (quartz structure) after sintering. Compared with the work of Chung Chiang et al. [13], the main crystalline of the composites is also SiO2 (quartz) phase due to its abundant silica. Second, and more importantly, low pre-fired temperature provides insufficient energy for forming largely an amorphous glass structure of Si-O network, resulting in the crystallization of SiO2 (quartz).

XRD patterns of samples with different CaO contents

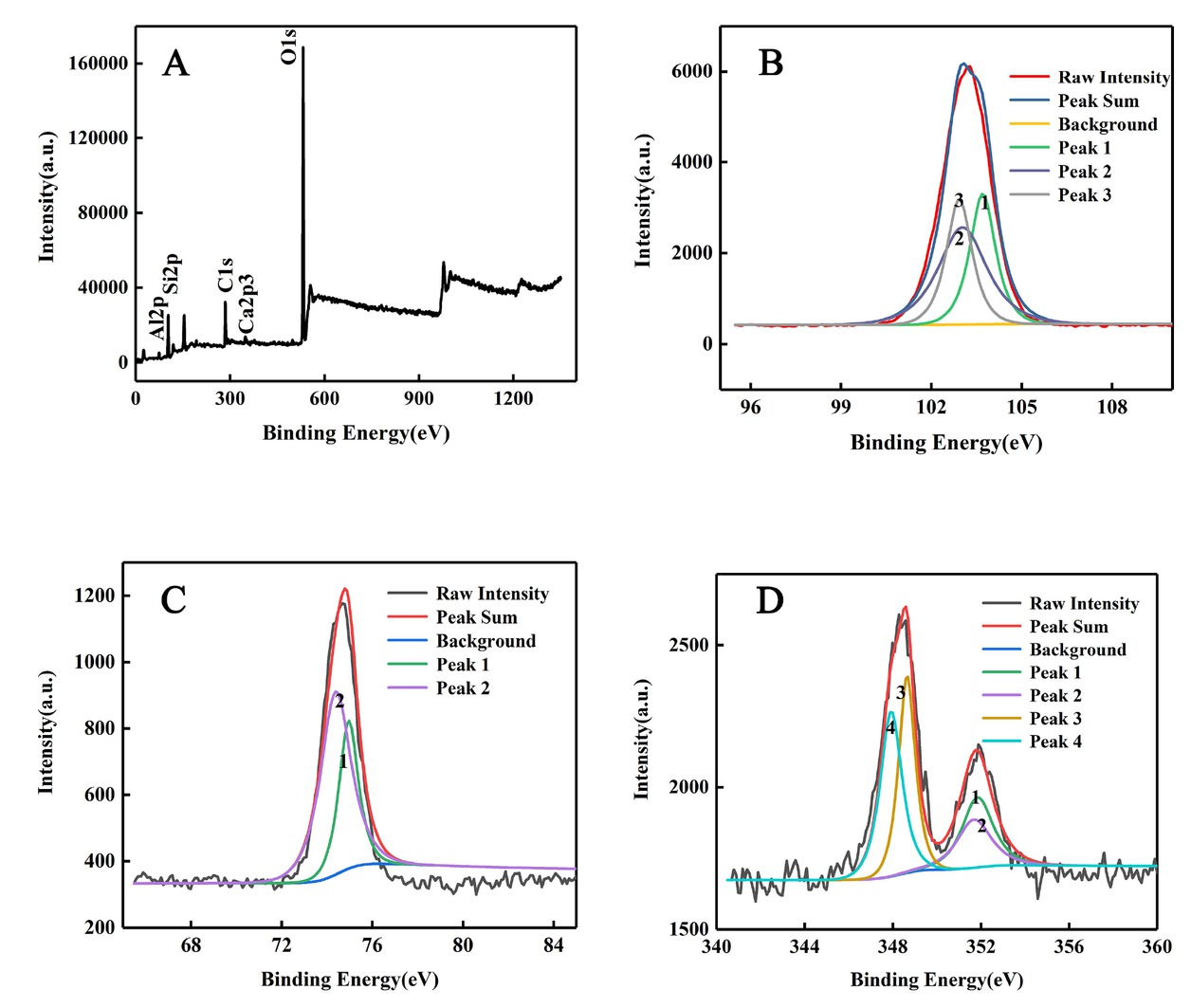

The XPS measurements is widely applied for confirming chemical state of composites [14]. In order to deepen our understanding of chemical state of composites, the XPS results are presented in Figure 2. The photoelectron binding energy peaks for each element are as follows: Al2p is at 74.17 eV, O1s is at 532.03 eV, and Si2p is at 102.86 eV. From the comparison between our experimental data and the XPS standard database [15], the XPS measurements results (Figure 2) further confirm the presence of SiO2 and Al2O3. The individual spectra of Ca shows the resolution of Ca2p spectrum into two peaks 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 at 350.85 and 348.02 eV, respectively. Ca2p spectrum possesses two

XPS patterns of the composite with CaO content of 2.8 wt.% sintered at 850∘C

peaks, which is also confirmed by this study of Aneela Anwar et al. [16].

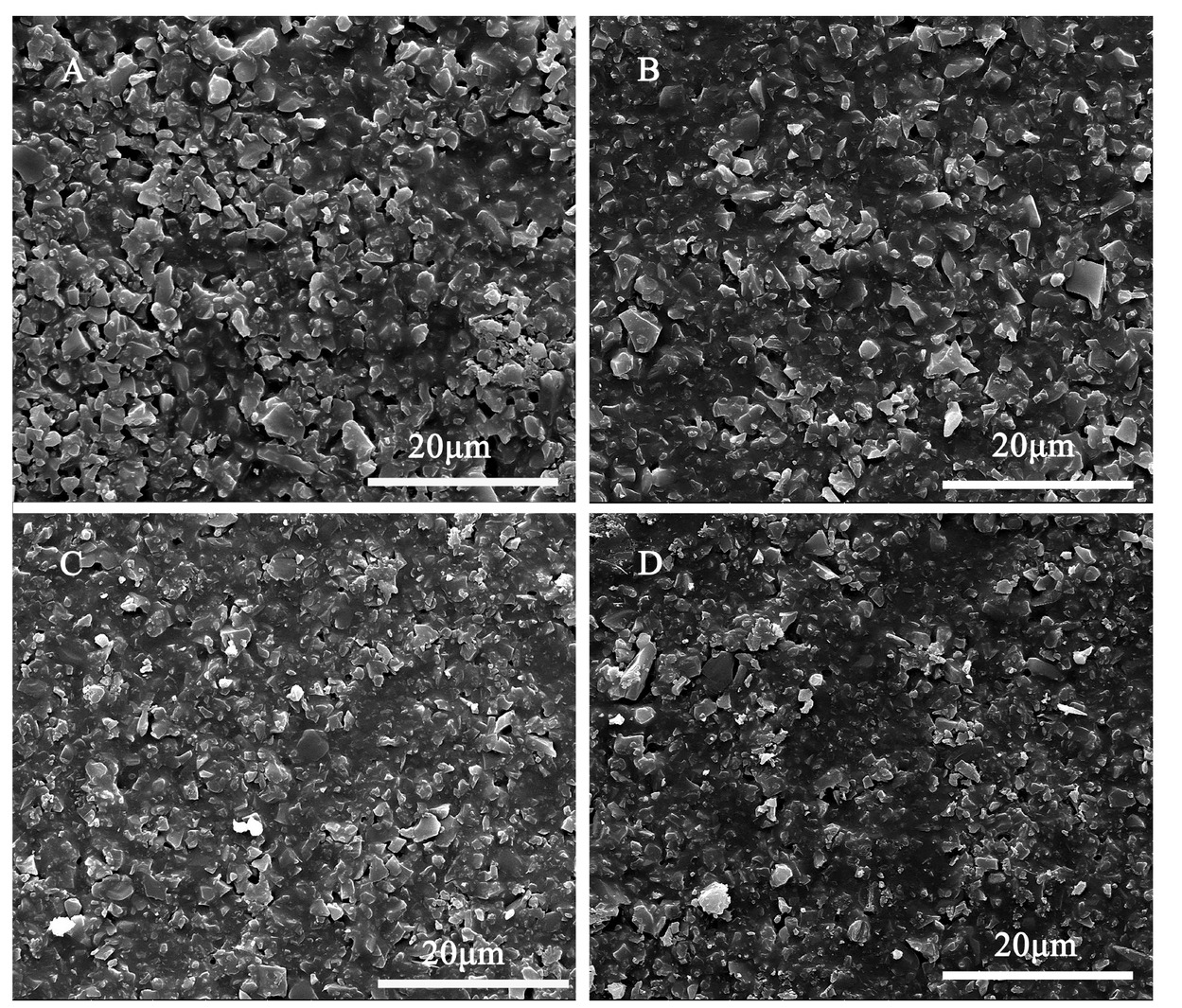

Figure 3 shows the microstructures of K2O–B2O3– SiO2–Al2O3 composites sintered at 850∘C for 2h. The research of SEM indicates that porosity, the heterogeneity of grain size as well as detectable amorphous phases are the typical microstructure of the composites. As CaO content increases up to 2.8 wt.%, Figure 3C reveals crystalline grains firmly embedded within a homogeneous liquid phase, showing a dense microstructure.

SEM micrograph of composites measured by secondary electrons mode A) S1; B) S4; C) S8; D) S9

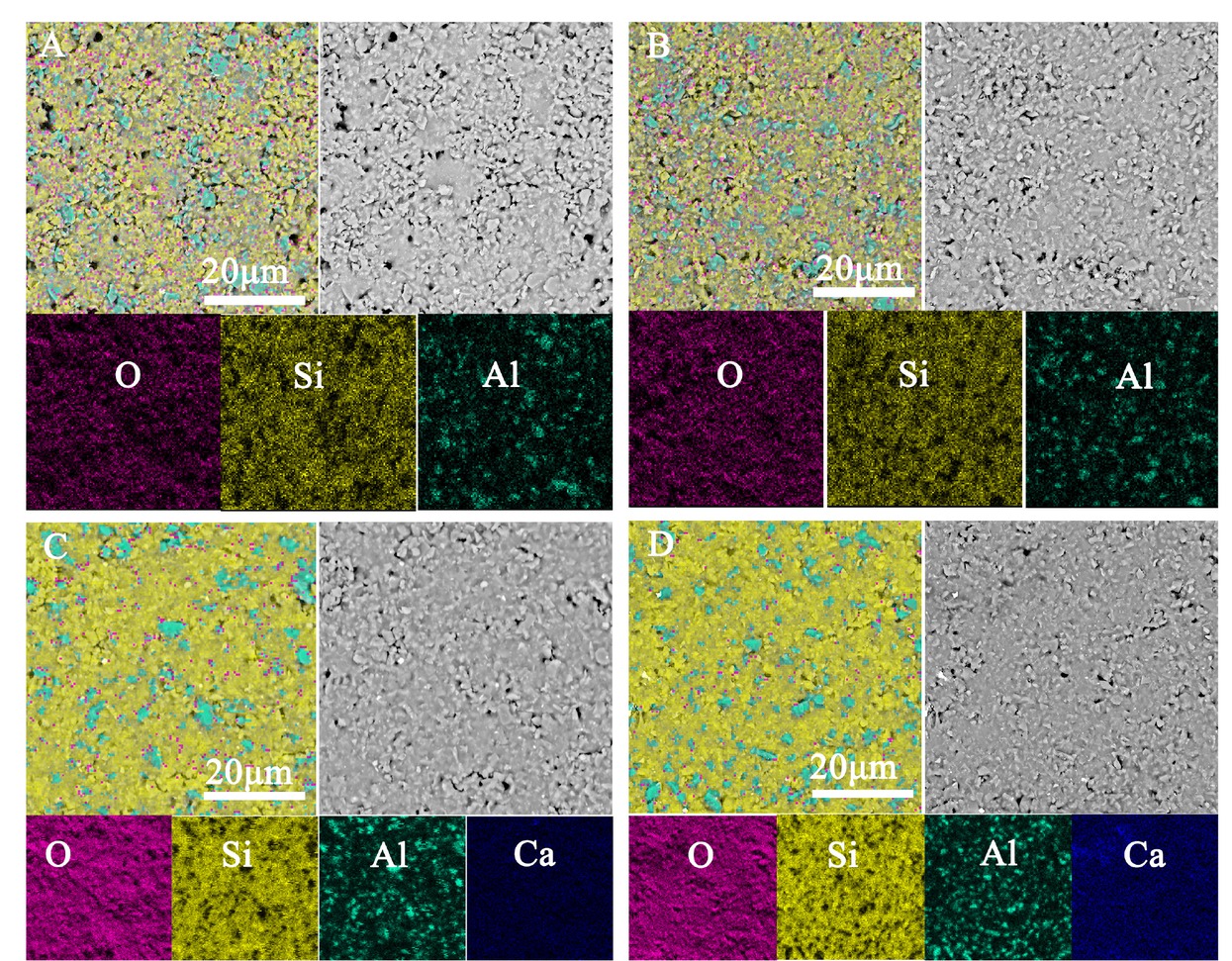

The remarkable changes in the element distributions of the composites sintered at 850∘C are shown in Figure 4A-D. Al2O3 crystals with maximal sizes of up to 7 μm are clearly discernable in the mappings C and D. Meanwhile, increasing enrichment of all the elements can be detected, indicating that it favors to efficiently increase the enrichment of elements by tailoring the addition of CaO.

Elemental map distributions measured by back scattered electron mode: A) S1; B) S4; C) S8; D) S9

The common structure of borosilicate glass is a structure of Si-O network modified by alkali ions and alkaline earth metal ions. These four metallic oxides have significant effects on breaking the network and promoting the formation of glass phase [17]. The movement of the mobile K+ and Na+ causes heavy dielectric loss but proportionate contents ofK+ and Na+ help the reduction of loss according to the mixed alkali effect in glass [18]. As the radius of Ba2+ is larger than other ions, it favors to efficiently suppress the migration of K+ and Na+ [17]. In this work, the powders sintered at 750∘C result in a certain volume fraction of liquid phase, which is available for low temperature sintering by liquid phase sintering theory.

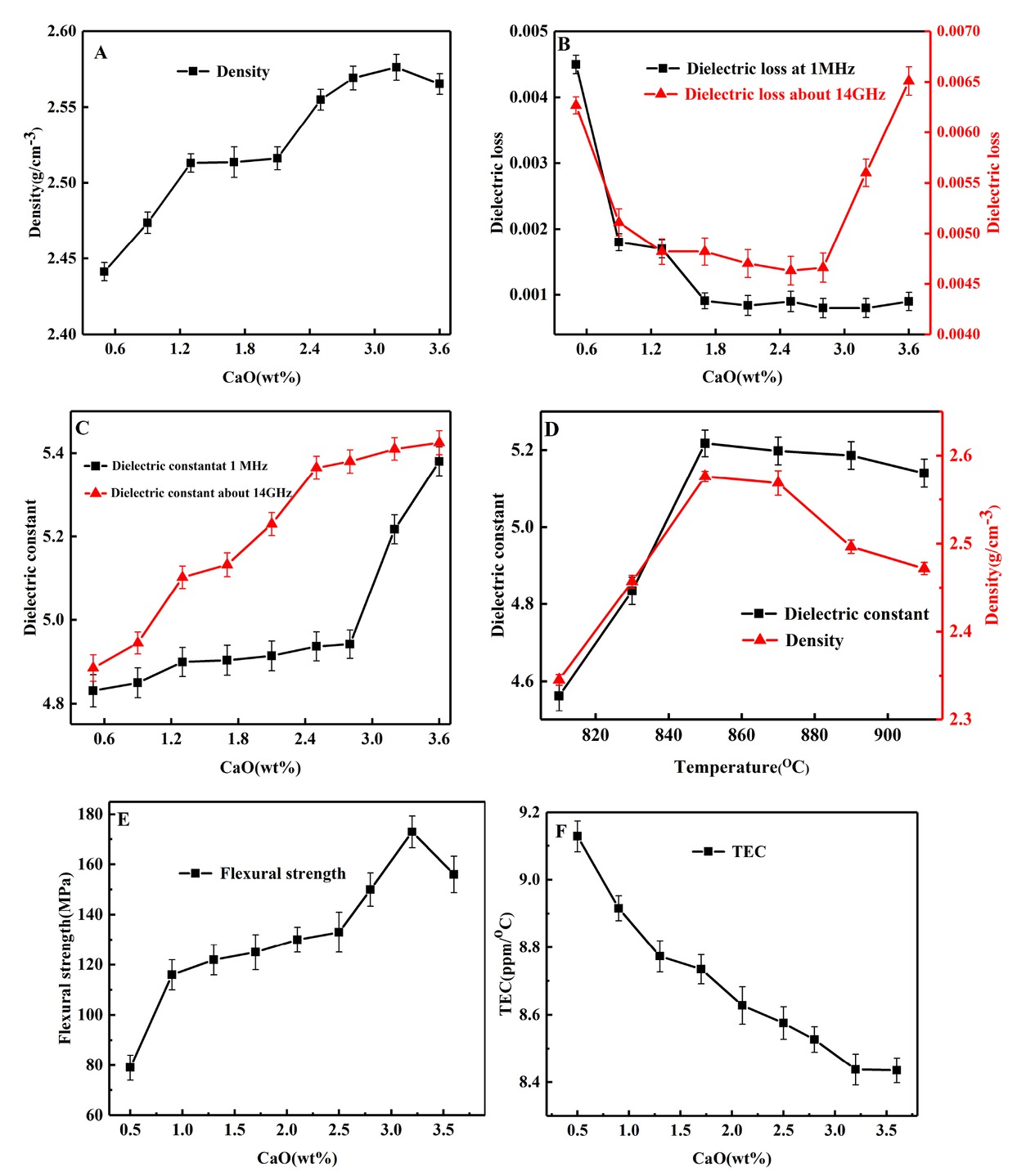

Figure 5A shows the change trend of density as a function of CaO content. The increasing density corresponds to elements enrichment reflected by the mappings in Figure 3. The results also show that the composites without melting glass addition can achieve a better density. As

Properties of composites: A) density; B) dielectric loss; C) dielectric constant; D) density and dielectric constant with different temperatures; E) strength; F) CTE

CaO content increases up to 3.2 wt%, the higher density of 2.57 g/cm3 with reasonably excellent characteristics of microstructures in Figure 3C is acceptable for the LTCC applications. Figure 4B represents dielectric loss of samples sintered at 850∘C. It appears that dielectric loss decreases as CaO content increases. In this work, dielectric loss most likely results from the movements of the mobile K+ and Na+ [17]. The effective radius of Ca2+ is close to barium ion, which shows a limited mobility in glass structure, thus preventing the migration of the alkali ions [19, 20]. Hence an increasing CaO content obviously leads to low loss and the dielectric loss is considerably below 10−3 when the addition of CaO is more than 1.5 wt%.

With respect to Figure 5C and D, it is generally believed that there is a clear relation between dielectric properties and densification [21, 22]. It can be seen in Figure 5 A and C that increasing density corresponds to the permittivity rising. In addition, permittivity is also influenced by the constituent phases. SiO2 has the low dielectric constants of 3.8, indicating that Si-rich composites have lower dielectric constant [22]. As shown in Figure 5C, the present composites emerge a low permittivity around 5 at 1MHz and 5.5 at 14 GHz with the CaO content of. 3.2 wt%.

As for physical properties shown in Figure 5E, flexural strength increases first and then decreases. In this work, the density is deemed to dominate the flexural strength of composites. The flexural strength of the composites firstly increases to 173MPa, and then slightly decreases to 156MPa as CaO content increases, closely corresponding to the density as shown in Figure 4 A. According to the theory of liquid phase sintering [1], the densification occurs through the viscous flow mechanism. When the composites are sintered at 850∘C, SiO2 and Al2O3 crystal particles dissolve easily in liquid phase and then rearrangement of grain availably makes samples compact [1, 23]. The results indicate that an excellent physical properties can be attained by the addition of CaO, showing a promising approach to preparing glass-ceramics without the addition of melting glass.

As for the thermal properties of the composites sintered at 850∘C, Figure 5F indicates that the CTE values of the composites ranging between temperatures of 25∘C~300∘C are 8~9 ppm/∘C. The CTE value of composites obviously decreases with the addition of CaO content. The reason is that tailoring CaO content contributes to densification, thus resulting in forming less pores. Because pores possess a higher CTE value (≈ 103 ppm/∘C), high densification corresponds to a decreasing thermal expansion. Obviously, the composites with CTE of 8~9 ppm/∘C is available for applications between the LTCC module and the alumina substrate [1, 24].

Finally, we make a comparison between the commercial LTCC materials and the K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites in this work. As shown in Table 2, the composites we prepared possess higher CTE, lower permittivity, and lower dielectric loss, which provides a good reliability for electronic packaging [25].

Properties of the composites in comparison with commercial LTCC materials

| Material | ϵr | Loss (10−3) | Strength (MPa) | CTE (ppm/∘C) | Sintering temperature (∘C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DuPont 951 | 7.8 | 1.5@1KHz | 320 | 5.8 | <900 |

| Ferro A6 | 5.9 | 2@10MHz | 130 | 7 | <900 |

| Heraeus CT700 | 7 | 2@1KHz | 240 | 6.7 | <900 |

| This work | 4.94 | 0.8@1MHz | 150 | 8.3 | 850 |

4 Conclusions

Without melting glass, the K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites were prepared through the simple solid state synthesis methods. The addition of CaO in the composites exerts superior effects on dielectric properties, thermal expansion coefficient and flexural strength. As CaO content increases up to 2.8wt%, the composites show a dielectric constant of 4.94 and tanδ of 8 × 10−4 at 1 MHz, thermal expansion coefficient of 8.5 ppm/∘C and flexural strength of 150 MPa, providing a useful thought for electronic packaging that K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites with dielectric constant less than 5 can be prepared by tailoring the addition of CaO.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51202021), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21603203) and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2014RZ0041).

References

[1] Sebastian M.T., Jantunen H., Low loss dielectric materials for LTCC applications: a review, Int. Mater. Rev. 2013, 53, 57-90.10.1179/174328008X277524Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Sebastian M.T., Ubic R., Jantunen H., Low-loss dielectric ceramic materials and their properties, Int. Mater. Rev., 2015, 60, 392-412.10.1002/9781119208549.appSuche in Google Scholar

[3] Feng J., Thian E.S., Applications of nanobioceramics to healthcare technology, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2013,2, 679-697.10.1515/ntrev-2012-0065Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Chen X., Zhang W., Bai S., Du Y., Densification and characterization of SiO2–B2O3–CaO–MgO glass/Al2O3 composites for LTCC application, Ceram. Int., 2013, 39, 6355-6361.10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.01.061Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Yoon S.O., Shim S.H., Kim K.S., Park J.G., Kim S., Low-temperature preparation and microwave dielectric properties of ZBS glass–Al2O3 composites, Ceram. Int., 2009, 35, 1271-1275.10.1016/j.ceramint.2008.04.003Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Liu M., Zhou H., Xu X., Yue Z., Liu M., Zhu H., Sintering, densification and crystallization of Ca–Al–B–Si–O glass/Al2O3 composites for LTCC application, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., 2013, 24, 3985-3994.10.1007/s10854-013-1351-7Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Chen M.-Y., Juuti J., Hsi C.-S., Chia C.-T., Jantunen H., Alford N., Dielectric Properties of Ultra-Low Sintering Temperature Al2O3- BBSZ Glass Composite, J. Amer. Ceram. Soc., 2015, 98, 1133-1136.10.1111/jace.13395Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Cui X.-M., He Y., Liang Z.-Y., Zhang H., Zhou J., Different microstructure BaO–B2O3–SiO2 glass/ceramic composites depending on high-temperature wetting affinity, Ceram. Int., 2010, 36, 1473-1478.10.1016/j.ceramint.2010.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Xia Q., Zhong C.-W., Luo J., Low temperature sintering and characteristics of K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 glass/ceramic composites for LTCC applications, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., 2014, 25, 4187-4192.10.1007/s10854-014-2147-0Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Luo X., Ren L., Xie W., Qian L., Wang Y., Sun Q., Zhou H., Microstructure, sintering and properties of CaO–Al2O3–B2O3–SiO2 glass/Al2O3 composites with different CaO contents, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron., 2016, 27, 5446-5451.10.1007/s10854-016-4448-ySuche in Google Scholar

[11] Jantunen H., Rautioaho R., Uusimaki A., Leppavuori S., Preparing Low-Loss Low-Temperature Cofired Ceramic Material without Glass Addition, J. Amer. Ceram., 2000, 83, 2855-2857.10.1111/j.1151-2916.2000.tb01644.xSuche in Google Scholar

[12] Cui X., Zhou J., A simple and an effective method for the fabrication of densified glass-ceramics of low temperature co-fired ceramics, Mater. Res. Bull., 2008, 43, 1590-1597.10.1016/j.materresbull.2007.07.038Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Chiang C.-C., Wang S.-F., Wang Y.-R., Wei W.-C.J., Densification and microwave dielectric properties of CaO–B2O3–SiO2 system glass–ceramics, Ceram. Int., 2008, 34, 599-604.10.1016/j.ceramint.2006.12.008Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Li Z., Xu K., Wei F., Recent progress in photodetectors based on low-dimensional nanomaterials, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2018, 7, 393-411.10.1515/ntrev-2018-0084Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Moulder J.F., Stickle W.F., Sobol P.E., Bomben K.D., Handbook of X-ray photoelectron Spectroscopy, 1995, Phys. Electron, Eden Prairie.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Anwar A., Kanwal Q., Akbar S., Munawar A., Durrani A., Hassan Farooq M., Synthesis and characterization of pure and nanosized hydroxyapatite bioceramics, Nanotechnol. Rev., 2017, 6, 149-157.10.1515/ntrev-2016-0020Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Imanaka Y., Multilayered Low Temperature Cofired Ceramics (LTCC) Technology, 2005, Springer, New York.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Isard J.O., The Mixed Alkali effect in glass, J. Non-Cryst. Solids., 1969, 1, 235-261.10.1016/0022-3093(69)90003-9Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Chen G.-H., Sintering, crystallization, and properties of CaO doped cordierite-based glass–ceramics, J. Alloys Comp., 2008, 455, 298-302.10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.01.036Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Hu Y., Tsai H.T., The effect of BaO on the crystallization behaviour of a cordierite-type glass,Mater. Chem. Phys., 1998, 52, 184-188.10.1016/S0254-0584(98)80023-0Suche in Google Scholar

[21] George S., Sebastian M.T., Raman S., Mohanan P., Novel Low Loss, Low Permittivity Glass-Ceramic Composites for LTCC Applications, J. Appl. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 8, 172-179.10.1111/j.1744-7402.2009.02423.xSuche in Google Scholar

[22] Induja I.J., Surendran K.P., Varma M.R., Sebastian M.T., Low k low loss alumina-glass composite with low CTE for LTCC microelectronic applications, Ceram. Int., 2017, 43, 736-740.10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.10.002Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Kwon O.H., Messing G.L., Kinetic Analysis of Solution-Precipitation During Liquid-Phase Sintering of Alumina, J. Amer. Ceram. Soc., 1990, 73, 275-28.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1990.tb06506.xSuche in Google Scholar

[24] Tummala R.R., Ceramic and Glass-Ceramic Packaging in the 1990s, J. Amer. Ceram., 1991, 74, 895-908.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1991.tb04320.xSuche in Google Scholar

[25] Yang H., Li E., Duan S., He H., Zhang S., Structure, microwave properties and low temperature sintering of Ta2O5 and Co2O3 codoped Zn05Ti0.5NbO4 ceramics, Mater. Chem. Phys., 2017, 199, 43-53.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.06.025Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Y. Shang et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview