Abstract

The solar power is one of the most promising renewable energy resources, but the high cost and complicated preparation technology of solar cells become the bottleneck of the wide application in many fields. The most important parameter for solar cells is the conversion efficiency, while at the same time more efficient preparation technologies and flexible structures should also be taken under significant consideration [1]. Especially with the rapid development of wearable devices, people are looking forward to the applications of solar cell technology in various areas of life. In this article the flexible solar cells, which have gained increasing attention in the field of flexibility in recent years, are introduced. The latest progress in flexible solar cells materials and manufacturing technologies is overviewed. The advantages and disadvantages of different manufacturing processes are systematically discussed.

1 Introduction

In the field of large-area and green energy supply, solar cells have wide applications [2]. As the conversion efficiency increases and cost decreases, solar cell acquires more commercial applications. The concept of flexible solar cells appeared long time ago since a flexible structure facilitates the harvest of solar power on a large extent [3, 4]. Silicon solar cells have been extensively studied since early 1950s, and an increasing number of photovoltaic materials are investigated to improve cell performances. Monocrystalline silicon and polycrystalline silicon are applied to solar cells in succession. Since 1970s the amorphous silicon solar cells were developed [5]. Compared with the crystalline silicon, amorphous silicon is much lighter and thinner. In recent years, a variety of solar cells have been designed: dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), organic solar cells, Cu(In, Ga)Se2 (CIGS) solar cells, perovskite solar cells, etc. [6]. To overcome the issue of flexibility, great efforts have been made to create different flexible component materials [7]. In particular, transparent electrode is an essential part for solar cells, and ITO conductive films are commonly used [8]. Despite flexible ITO glasses, flexible solar cells with opacity electrodes made of fibers were reported [9]. A significant progress has been achieved in manufacturing different kinds of flexible solar cells and their conversion efficiencies increase along with the technology advances.

2 Materials for flexible silicon solar cells

The silicon solar cells have been made huge progresses in these years, gaining the wildest applications in our lives. The abundant resources of silicon and the relative composite elements like boron, nitrogen enable the continuous production of such solar cells. Silicon solar cells are qualified for many operating situations for their stability, safety and outstanding service life, the flexibility of such solar cells explores the applications in more specific areas like buildings and vehicles. Presently there are three kinds of silicon solar cells including monocrystalline silicon, polycrystalline silicon and amorphous silicon.

Monocrystalline silicon solar cells possess the highest conversion efficiency up to 26% and develops fast these years. By adopting thin silicon layer to be the substrate of light-trapping layer, researchers have designed different structures of solar cells with decent properties. Fang et al. reported an ultrathin flexible solar cell with monocrystalline silicon substrate to support the silicon nanowires [10]. The cell also has a passivating layer of Al2O3 on the nanowires which enhances the light absorbing. Testing results show a conversion efficiency up to 16.61%. Lin et al. also utilized a 30 m thick silicon to be the flexible substrate [11]. The substrate is made by etching in a NaOH solution until the silicon chip is fully bendable and silicon constructs a 3D structure through a process of surface texturization. McMahon et al. utilized a glass substrate with high transition temperature to be the flexible substrate [12]. They adopted an Al catalyst layer which is deposited on the soft glass to grow silicon nanowires, the Al layer is deposited by thermal evaporation. Then the (111) oriented monocrystalline silicon subsequently by a process of electron beam evaporation. The method provides a possible approach to effectively induce electrode materials to soft substrates. To form a flexible cell, researchers also changes the outside structure of solar cells. A flexible monocrystalline silicon band is fabricated which indicates faster silicon production and solves the inconvenience of silicon ingots.

Polycrystalline silicon solar cells and amorphous silicon solar cells have a shortage in efficiency comparing with the monocrystalline silicon solar cells, but they have lower cost and the conditions of producing silicon is less rigor. Another superiority for monocrystalline silicon is the higher optical absorption coefficient which leads to better performance in weaker light and lower cost. Plentz et al. reported a flexible solar cell by rigor depositing silicon onto glass fiber fabrics [13].With advantages of highly flexibility and thermal stability, the glass fiber is a promising alternative choice for replacing traditional glass or metal substrates. For the requirement of light absorbing, an aluminum-doped zinc-oxide layer is deposited as the transparent contact layer and the back titanium layer is reduced to semi-transparent for better illumination. The Ag nano particles efficiently reflect and scatter light back and correspondingly the current density increases to 19.5% higher. Águas et al. reported an application of cellulose paper in solar cell fabrication [14]. The paper with a hydrophilic mesoporous layer provides a wide, light and high thermal stability substrate for silicon solar cells. The comparison with solar cells deposited on glass shows that the paper not only forms a flexible packing of the cell but also has no effect on performance. Silicon solar cells are relative stable power systems with a solid structure, as different flexible composites are proposed and developed, the efficiency of the flexible cells increases gradually. Different scheme of silicon solar cells’ connections like partitioning and welding also promote the multi-application of these cells. It is be expected that silicon solar cells will gain more applications in our lives with the realization of flexible technologies.

3 Materials for flexible DSSCs

In 1991, Grätzel et al. reported a new kind of solar cell: dye-sensitized solar cell (DSSC), opening up a new way for the explorations and utilizations of solar energy [15]. DSSCs have the advantages of abundant sources of raw materials, low cost and relatively simple manufacturing technique [16, 17]. With wider acceptance of material purity and relatively lower cost, the DSSCs show high competitiveness with the conventional solar cells. Till the development of DSSCs so far, the efficiency has reported up to be 13% [18, 19]. The DSSCs consist of a conductor, a dye photosensitizer, a nanoporous semiconductor membrane, counter electrodes and electrolyte. The photo anode and the counter electrode are the skeletal structure of DSSCs, thus flexible DSSCs require that both of the electrodes are flexible [20]. Usually conducting glasses, e.g. the indium doped tin oxide-coated (ITO) glass and the fluorine-doped tin oxide-coated (FTO) glass, are used to be the transparent conductor. However, the application of glasses is limited by their fragility and high weight. Actually, researchers have made efforts to deposit transparent conductive oxide on the flexible substrates. Up to now, the ITO-sputtered PEN (polyethylene naphthalate) and PET (polyethylene terephthalate) have been widely utilized in various photovoltaic devices due to their excellent electrical conductivity, light weight and good flexibility. Furthermore, by utilizing the roll-to-roll system in industry, it’s possible to mass produce ITO/PET substrate with large scales. The polymeric electrode substrates, such as the ITO-sputtered PEN and PET, are suffered with mechanical or chemical changes when treated in a high process temperature. Lee et al. reported a flexible ITO-PEN substrate via electro spray deposition to prepare hierarchically structured TiO2 on a flexible ITO-PEN under low temperatures (less than 150∘C) [21]. The simple fabrication process formed porous membranes with large surface areas and after the post processing, the cell efficiency also increases to 5.57%.

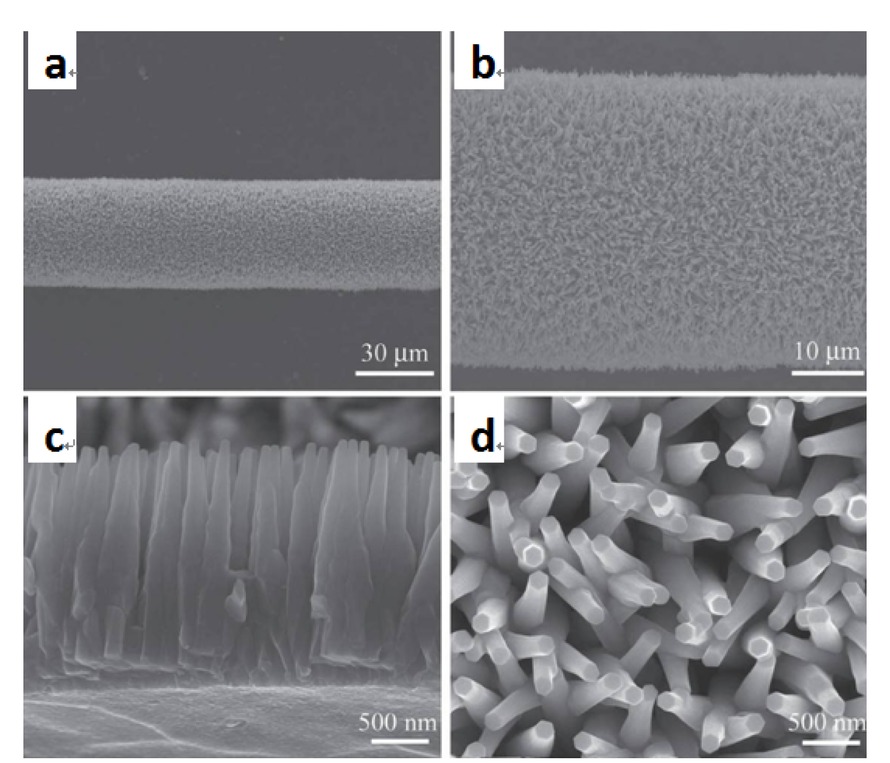

ITO plays an important role in the most field of solar cells compositing, the lack of indium resources and the producing process aggravate the cost of solar cells and present a limit in large-scale production. Therefore, it demands to find alternative materials for replacing ITO. There have been several attempts to fabricate DSSCs by using fabric-based electrodes, Kavan et al. crossed the transparent PEN woven fabric and electrochemically platinized tungsten wires in vertical directions to form a flexible cathode [22]. By contrary with the thermally platinized FTO, it shows that the flexible electrode is enhanced in ohmic resistance. On the other hand, due to the transparent PEN fiber and TiO2 film, the electrode shows better optical transparency. The electrode exhibits good stability and storage capacity at open circuit for almost a month. Wang et al. let the ZnO nanowire arrays radially grown on wires of stainless steel, Au, Ag, and Cu as the working electrodes, while Pt wires to be the counter electrodes [23]. Figure 1 shows the SEM photo of ZnO nanowire arrays from different angles. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) show that the ZnO nanowire is along the whole length of the wire of Fe. Figures 1(c) and 1(d) clearly exhibit the fully uniformity of the nanowires. The double-wire DSSCs possess merits of very good flexibility and high transparency via a simple, facile, and controllable way of disposition. Corningsr produced a type of flexible glass called Willowsr Glass whose thickness was only 100 μm, significantly increases the substrate flexibility and reduces the rigidity with bend stress less than 100 MPa at a bend radius of 5 cm [24, 25]. Such novel flexible glass has been applied in flexible applications as well as other solar cell devices, showing the potential for mass manufacturing of flexible devices. Sheehan et al. tested the DSSCs fabricated with the Willows Glass, the results demonstrate that flexible Willow Glass substrates with higher thermal stability owns the potential in roll-to-roll manufacturing for application in solar cells [20].Mean-while by comparing with the commercial ITO glasses, flexible glass substrates fabricated DSSC generates competitive efficiency with the conventional DSSCs.

(a) SEM image of ZnO nanowire arrays grown on stainless-steel microwires. (b) Magnified SEM image of a wire section, uniformly covered with high-density ZnO nanowires. (c) Cross-section and (d) top-view SEM images showing the well-aligned, high-density ZnO nanowire arrays grown on the stainless-steel microwire.

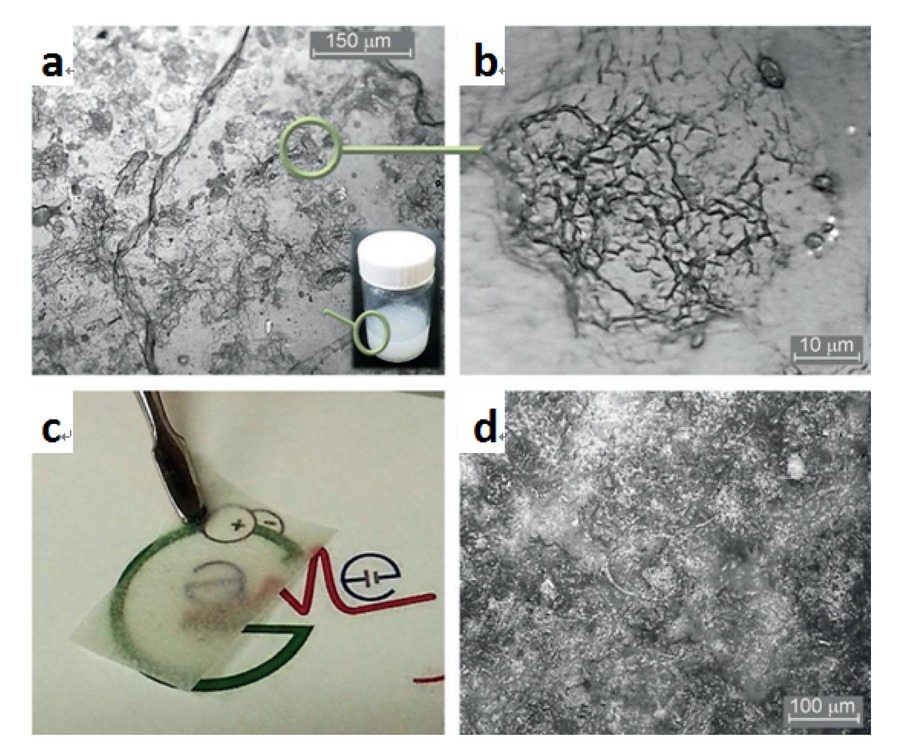

The electrolyte between the two electrodes has significant effects on the photoelectric performance and operate stability of flexible DSSCs. Conventionally high efficient DSSCs commonly used liquid electrolyte with low viscosity organic solvents, when applied in flexible DSSCs, the photo anode without high-temperature treatment cannot withstand long-term soaking. In addition, the risk of hard to encapsulate, easy to leak out and dissolving the polymer substrate are also difficult to resolve. Hence the gel or all-solid-state electrolyte becomes an important research direction for preparing stable, efficient and flexible DSSCs. Hoang et al. added lab-made platinum nanoparticles to improve the charge transfer of the gel electrolyte (based on polyethylene oxide (PEO)) [26]. The nano Pt serving as the catalyst to the gel electrolyte enhances the photovoltaic performance of DSSCs and improves the inside charge transfer between the redox layer and the oxidized dyes. The defect of the gel materials which limits its employment is that they don’t have specific forms. When the flexible cells are bent, the two electrodes will possibly come into contact, causing problems like short out. Polymer electrolyte membranes (PEMs) are good alternative materials to improve the gels’ defect, since they are self-standing with specific form which is more convenient and appropriate for the preparation of solid electrolytes for flexible DSSCs. Cellulose nanofibers, as introduced earlier, are explored to prepare PEMs. The high sunlight conversion efficiency of 7.03% is achieved at simulated light intensities of 1.0. Furthermore, the cellulose nanofibers also improve the long-term stability of the cells and excellent durability of over 95% retentive efficiency after treated by extreme aging conditions. Chiappone et al. selected Bisphenol A ethoxylate dimethacrylate (BEMA) and poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate (PEGMA) mixing with NFC solutions to prepare PEMs [27]. Figure 2(a) and 2(b) show the networks of the fibers and Figure 2(c) and 2(d) show the appearance of a stable PEM formed by 30 wt% NFCs under optical microscope. By adding the NFCs the film appears to be flexible but not rigid, free-standing and forms a stable network after drying which means great mechanical property. The addition of NFC enhances the stability of the devices and remains more than 95% of the efficiency under the over operating conditions.

(a, b) Optical microscope analysis of the NFC dried network of fibers; (c) appearance of a 30 wt% NFC-based PEM; (d) a 30 wt% NFC-based PEM observed with an optical microscope.

4 Materials for flexible perovskite solar cells

The perovskite solar cells were first put forward in 2009. The photoelectric transformation efficiency was only 3.8% at that time [28]. Zhou et al. promoted the efficiency to 16.6% on average, with the highest efficiency of 19.3% in 2014 [29]. And the efficiency has been rapidly risen up to 20.1% at present [30]. The speed of development of this technology is unprecedented and is worth high attention. The light absorption layer material of is CH3NH3PbX3 (X: I−, Br− or Cl−), the material is typically perovskite structure, and was first used as a novel dye in DSSCs. The cell structure was similar to typical DSSCs until Kim et al. reported an all-solid-state perovskite solar cell in 2012 [31]. They employed perovskite nanoparticles as light harvesters, and with standard AM-1.5 sunlight such cells generated large photocurrents exceeding 17 mA/cm2. Research on flexible perovskite solar cells subsequently made a significant progresses in the recent years. The difficulties for flexible perovskite solar cells to overcome include: flexible materials for both sides of substrates and alternative electrode materials to take place of Au or Ag to be the counter electrode. Das et al. prepared a flexible perovskite solar cell with high performance by a ultrasonic spray coating process [32]. With the PET substrate, the cell was bendable and the conversion efficiency was as high as 13%. A problem for flexible perovskite solar cells is that the high temperature requirement for producing the TiO2 layer which would limit the wider application of the device. You et al. prepared a high efficiency and flexibility perovskite solar cell using polyethylene terephthalate/ITO to be the flexible substrate [33]. The component layers were processed in solution form under 120∘C and a 9.2% efficiency was achieved. Similarly, in order to solve the low-temperature preparation problems, Dkhissi et al. reported a method to fabricate planar perovskite solar cells with controlling the entire process under the temperature of 150∘C [34]. By employing p-type poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly (styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) to replace TiO2 making up as the blocking layer, the process temperature is able to control and ensure a high efficiency of 12.3%.

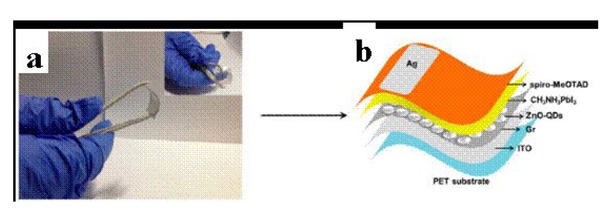

ZnO provided an alternative electron-transport layer material which is much thinner as reported by Liu et al. in 2013 [35]. Without the sintering process, the temperature can be reduced. Solar cells based on the design showed nice flexibility and exhibited conversion efficiency as high as 15.7%. Ameen et al. used ZnO quantum dots treated by the atmospheric plasma jet as the electron transport layer and ITO-PET as the substrates to assemble highly flexible perovskite solar cells [36]. In Figure ?? the ITO-PET/Gr thin film substrate and the fabricated solar cells are clearly showed. Figure 3(a) shows good flexibility of the substrate and Figure 3(b) demonstrates the cell structure. The ZnO quantum dots are coated on the ITO/Gr substrate by the atmospheric plasma jet method. Analysis shows that the jet-treated thin film fabricates the perovskite solar cell with enhanced photo current density. Additionally, the fabrication process with simplified procedures, long-term stability and flexible structure reveals the high developing potentials of such novel perovskite solar cells.

(a) Photograph of ITO-PET/Gr, (b) a schematic illustration of the fabricated ITO-PET/Gr/ZnO-QDs(AP jet)/CH3NH3PbI3/spiro-MeOTAD/Ag flexible perovskite solar cell.

5 Materials for Cu(In, Ga)Se2 solar cells

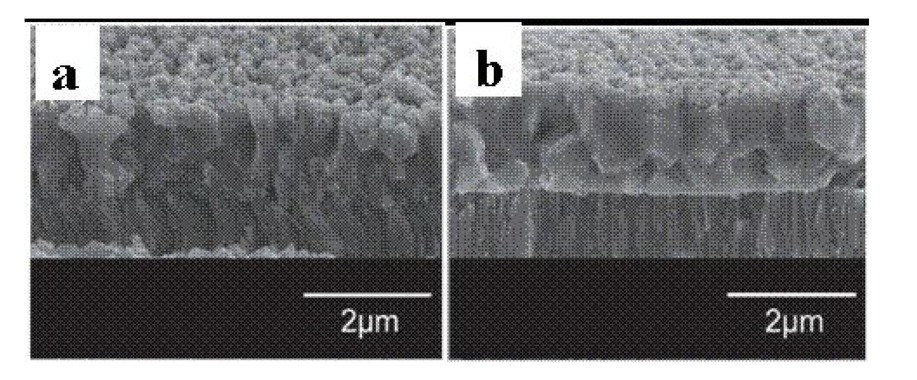

Copper indium gallium selenide thin film solar cells (CIGSs) is quickly developed after the 1980s among the various types of solar cells. With the advantages of high efficiency, low cost and flexible possible, CIGSs are considered to be the best potential choice of the next solar cell generation. The highest conversion efficiency of CIGSs reported so far is 20.8%, with the deposition on a rigid glass substrate [37]. Comparing with traditional CIGSs, the flexible CIGSs are lighter, foldable and can be applied to uneven surface [38, 39]. Flexible substrate CIGSs also open up more application possibilities in the ground and space, for instance, the transport, installation, maintenance and disassembly. Methods like evaporation, sputtering and deposition are suitable for flexible electrode producing and how to better coordinate the connection of cells also becomes the key points. The choice of flexible substrate should meet the requirements of good thermal stability, which is able to bear the high temperature environment when producing the absorption layer, chemical stability without reacting with Se, and adaptability of vacuum and suitable for coiling. Flexible foils are the most commonly used flexible substrates, they are demonstrated with cost-effectiveness and versatility [40, 41]. In particular, stainless steel is one of the most promising materials as a flexible substrate. Many reports demonstrate the possibilities of the deposition of CIGSs on stainless steel with varied methods. In attempt to increase the efficiency, Liu et al. reported a flexible CIGSs on stainless steel with a special Ti/TiN composite structure [42]. The efficiency of 9.1% is demonstrated as a consequence of the unique structure for the Fe ion diffusion barrier. Broadband nano-structured antireflection coatings are applied in flexible CIGS solar cell as reported by Pethuraja et al. [43]. In addition, combined flexible foils can also be applied as the supporting layer, and the addition of Mo and Cr on stainless steel deliver the highest conversion efficiency of 9.88% [44]. And CIGSs on stainless steel with deposited Na/Mo layer exhibit the highest efficiency of 15.04%. Polymer substrates, on the other hand, are another interesting materials, which also have been developed intensively [45, 46]. Li et al. applied the co-evaporation process to deposit CIGSs on polyimide, obtaining a conversion efficiency of 7% [47]. Figure 4 presents the SEM images of the CIGSs cross-sections made by the modified method and the traditional method, respectively.With the modified three-stage co-evaporation process, the grain size of CIGS becomes significantly larger than the traditional process. The combination of flexible foils and polymers is also found with potential to serve as a promising substrate. Yu et al. deposited and laser scribed a Mo thin film on the polyimide substrate to assess the capability of scribing on the combined film [48]. Although many of CIGSs solar cells with flexible substrates are demonstrated with high efficiency of ~10%, it still remains to be developed.

SEM images of CIGS thin films grown with (a) traditional process and (b) new process.

6 Conclusion and future outlook

Unlike solar cells based on rigid slabs or filmy cells on the glass substrates, the most important traits of flexible solar cells are of light weight, shatter-resistant and they exhibit high specific power. The technology of flexible solar cells is also reposed on the flexible substrates, for instance: the stainless steel or polymers [49, 50]. As most of the solar cells have requirements of high transparency of the electrodes, researchers are searching for flexible transparent materials to replace the hard glasses in the part of light blocking layer. The flexible structure of solar cells provides opportunities to continuous and mass production of power supply in the future. It can be expected that flexible energy applications will eventually change the energy structure profoundly and transform our life enormously.

Acknowledgement

Thework is supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2014RZ0041)

References

[1] Ruan K., Ding K., Wang Y., Flexible graphene/silicon heterojunction solar cells, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 27(3), 14370-14377.10.1039/C5TA03652FSuche in Google Scholar

[2] Archer M.D., Green M.A., Clean electricity from photovoltaics, 2014, World Scientific.10.1142/p798Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Hwang T.H., U.S. Patent Application 13/567, 2012, 314.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Chen Z., Large Area and Flexible Electronics, 2015, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Carlson D.E., Wronski C.R., Amorphous Silicon Solar Cell, Appl. Phys. Lett., 1976, 28, 671-673.10.1063/1.88617Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Fu X., Xu L., Li J., Sun X., Peng H., Flexible solar cells based on carbon nanomaterials, Carbon, 2018, 139, 1063-1073.10.1016/j.carbon.2018.08.017Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang X., Öberg V. A., Du J., Johansson E. M. J., Extremely lightweight and ultra-flexible infrared light-converting quantum dot solar cells with high power-per-weight output using a solution-processed bending durable silver nanowire-based electrode, Royal Soc. Chem., 2018, 11, 354-364.10.1039/C7EE02772ASuche in Google Scholar

[8] Cao B., Yang L., Jiang S., Lin H., and Li X., Flexible quintuple cation perovskite solar cells with high efficiency, J. Mater. Chem. A, 2019, 7, 4960-4970.10.1039/C8TA11945GSuche in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang Z., Chen X., Chen P., Integrated polymer solar cell and electrochemical supercapacitor in a flexible and stable fiber format, Adv. Mater., 2014, 26 , 466-470.10.1002/adma.201302951Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Fang X., Li Y., Wang X., Ultrathin interdigitated back-contacted silicon solar cell with light-trapping structures of Si nanowire arrays,Solar Energy , 2015, 116 , 100-107.10.1016/j.solener.2015.03.034Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Lin C. C., J Y., Chuang, Sun W. H., Ultrathin single-crystalline silicon solar cells for mechanically flexible and optimal surface morphology designs, Microelectronic Engineering, 2015, 145, 128-132.10.1016/j.mee.2015.04.013Suche in Google Scholar

[12] McMahon S., Chaudhari A., Zhao Z., Textured (111) crystalline silicon thin film growth on flexible glass by e-beam evaporation, Materials Letters, 2015, 158, 269-273.10.1016/j.matlet.2015.06.031Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Plentz J., Andrä G., Pliewischkies T., Amorphous silicon thin-film solar cells on glass fiber textiles, Materials Science and Engineering, 2015, B, 34-37.10.1016/j.mseb.2015.11.007Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Águas H., Mateus T., Vicente A., Thin Film Silicon Photovoltaic Cells on Paper for Flexible Indoor Applications, Advanced Functional Materials, 2015, 25, 3592-3598.10.1002/adfm.201500636Suche in Google Scholar

[15] O’regan B., Grätzel M., High-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films, Nature, 1991, 353, 737-740.10.4324/9781315793245-57Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Sahito I.A., Sun K., Arbab A.A., Graphene coated cotton fabric as textile structured counter electrode for DSSC, Electrochimica Acta, 2015, 173, 164-171.10.1016/j.electacta.2015.05.035Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Deepa K.G., Lekha P., Sindhu S., Efficiency Enhancement in DSSC Using Metal Nanoparticles: a Size Dependent Study, Solar Energy, 2012, 86, 326-330.10.1016/j.solener.2011.10.007Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Mathew S., Yella A., Gao P., Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells with 13% Efficiency Achieved Through the Molecular Engineering of Porphyrin Sensitizers, Nature Chem., 2014, 6, 242-247.10.1038/nchem.1861Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Lau G.P.S., Tsao H.N., Yi C., Robust High-performance Dye-sensitized Solar Cells Based on Ionic Liquid-sulfolane Composite Electrolytes, Sci. Rep., 2015, 8, 255-259.10.1038/srep18158Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Yoo K., Kim J. Y., Lee J. A.,Toward Printable Sensitized Mesoscopic Solar Cells: Light-Harvesting Management with Thin TiO2 Films, ACS Nano, 2015, 9, 3760-3771.10.1021/acsnano.5b01346Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Lee H., Hwang D., Jo S. M., Low-Temperature Fabrication of TiO2 Electrodes for Flexible Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Using an Electrospray Process, ACS Appl. Mater. Interf., 2012, 4, 3308-3315.10.1021/am3007164Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Kavan L., Liska P., Zakeeruddin S.M.,Macroscopic, Flexible, High-Performance Graphene Ribbons, ACS Appl. Mater. Interf., 2014, 6, 22343-22350.10.1021/am506324dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Wang W., Zhao Q., Li H., Transparent, Double-Sided, ITO-Free, Flexible Dye-Sensitized Solar cells Based on Metal Wire/Zno Nanowire Arrays, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2012, 22, 2775-2782.10.1002/adfm.201200168Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Wang J., Fang Z., Zhu H., Flexible, transparent, and conductive defrosting glass, Thin Solid Films, 2014, 556 ,13-17.10.1016/j.tsf.2013.12.060Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Sheehan S., Surolia P.K., Byrne O., Flexible glass substrate based dye sensitized solar cells, Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells, 2015, 132, 237-244.10.1016/j.solmat.2014.09.001Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Hoang T.T., Nguyen P.H., Huynh T.P., Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, 2013, 39, 2713-2715.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Bella F., Lambertti A., Sacco A., Bianco S., Novel electrode and electrolyte membranes: Towards flexible dye-sensitized solar cell combining vertically aligned TiO2 nanotube array and light-cured polymer network, J. Membr. Sci., 2014, 470, 125-131.10.1016/j.memsci.2014.07.020Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Kojima A., Teshima K., Shirai Y., Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells, J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 6050-6051.10.1021/ja809598rSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Zhou H., Chen Q., Li G., Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells, Science, 2014, 345, 542-546.10.1126/science.1254050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Bertoluzzi L., Sanchez R.S., Liu L., Cooperative kinetics of depolarization in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells, Energy Environ. Sci., 2015, 8, 910-915.10.1039/C4EE03171GSuche in Google Scholar

[31] Kim H.S., Lee C.R., Im J.H., Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%, Sci. Rep., 2012, 591.10.1038/srep00591Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Sanjib D., Yang B., Gu G., High-Performance Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells by Using a Combination of Ultrasonic Spray-Coating and Low Thermal Budget Photonic Curing , ACS Photonics, 2015, 2, 680-686.10.1021/acsphotonics.5b00119Suche in Google Scholar

[33] You J., Hong Z., Yang Y., Low-temperrature solution processed perovskite solar cells with high efficency and flexibility, ACS Nano, 2014, 8, 1674-1680.10.1021/nn406020dSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Dkhissi Y., Huang F., Rubanov S., Low temperature processing of flexible planar perovskite solar cells with efficiencyover 10%, J. Power Sourc., 2015, 278, 325-331.10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.12.104Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Liu D., Kelly T.L., Perovskite Solar Cells with a Planar Hetero-junction Structure Prepared Using Room-Temperature Solution Processing Techniques, Nature Photonics , 2014, 8, 133-138.10.1038/nphoton.2013.342Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Ameen S., Akhtar M.S., Seo H.K., An Insight into Atmospheric Plasma Jet Modified ZnO Quantum Dots Thin Film for Flexible Perovskite Solar Cell: Optoelectronic Transient and Charge Trapping Studies, J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 10379-10390.10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b00933Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Jackson P., Hariskos D., Wuerz R., Compositional investigation of potassium doped Cu (In,Ga)Se2 solar cells with efficiencies up to 20.8%, Phys. Stat. Solidi (RRL) - Rapid Res. Lett., 2014, 8, 219-222.10.1002/pssr.201409040Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Park S.J., Chung Y.D., Lee W.J., Flexible solar cells with a Cu(In,Ga)Se2 absorber grown by using a Se thermal cracker on a polyimide substrate, J. Korean Phys. Soc., 2015, 66, 76-81.10.3938/jkps.66.76Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Moriwaki K., Nomoto M., Ishizuka S., Effects of alkali-metal block layer to enhance Na diffusion into Cu(in,Ga)Se2 absorber on flexible solar cells, Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells, 2015, 133, 21-25.10.1016/j.solmat.2014.10.039Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Gremenok V.F., Zaretskaya E.P., Bashkirov S.A., Growth and Optical Properties of Cu(In, Ga)Se2 Thin Films on Flexible Metallic Foils, J. Adv. Microsc. Res., 2015, 10, 28-32.10.1166/jamr.2015.1233Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Elrawemi M., Blunt L., Fleming L., Metrology of Al2O3 Barrier Film for Flexible CIGS Solar Cells, Int. J. Energy Optim. Eng., 2015, 4, 48-61.10.4018/IJEOE.2015100104Suche in Google Scholar

[42] LiuW.S., Hu H.C., Pu N.W., Developing Flexible CIGS Solar Cells on Stainless Steel Substrates by using Ti/TiN Composite Structures as the Diffusion Barrier Layer, J. All. Compd., 2015, 631, 146-152.10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.12.189Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Pethuraja G.G., Welser R.E., Zeller J.W., Cambridge University Press, 2015, 1771, mrss15-2134661.10.1557/opl.2015.509Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Kim K.B., Kim M., Baek J., Influence of Cr thin films on the properties of flexible CIGS solar cells on steel substrates, Electr. Mater. Lett., 2014, 10, 247-251.10.1007/s13391-013-3158-3Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Woods L.M., Stevens H., Armstrong J.H., U.S. Patent Application 14/198, 2014, 209.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Markauskas E., Gečys P., Račiukaitis G., Evaluation of electrical shunt resistance in laser scribed thin-films for CIGS solar cells on flexible substrates, Int. Soc. Optics Photon., 2015, 9350.10.1117/12.2079867Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Li Z., Liu Y., Liu W., Modified co-evaporation process for fabrication of 4 cm × 4 cm large area flexible CIGS thin film solar cells on polyimide substrate, Mater. Res. Expr., 2015, 2, 046403.10.1088/2053-1591/2/4/046403Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Yu X., Ma J., Lei S., Femtosecond laser scribing of Mo thin film on flexible substrate using axicon focused beam, J. Manuf. Proc., 2015, 349-355.10.1016/j.jmapro.2015.05.004Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Chantana J., Hironiwa D., Watanabe T., Physical properties of Cu (In, Ga) Se2 film on flexible stainless steel substrate for solar cell application: a multi-layer precursor method, Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells, 2015, 143, 510-516.10.1016/j.solmat.2015.08.001Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Zhang Z., Yang Z., Deng J., Stretchable polymer solar cell fibers, Small, 2015, 11, 675-680.10.1002/smll.201400874Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2019 R. Zhu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview