Abstract

This review is devoted to discuss the unique characteristics of multi-jet electrospinning technique, compared to other spinning techniques, and its utilization in spinning of natural as well as synthetic polymers. The advantages and inadequacies of the current commercial chemical spinning methods; namely wet spinning, melt spinning, dry spinning, and electrospinning are discussed. The unconventional applications of electrospinning in textile and non-textile sectors are reported. Special emphasis is devoted to the theory and technology of the multijet electrospinning as well as its applications. The current status of multi-jet electrospining and future prospects are outlined. Using multi-jet electrospinning technique, various polymers have been electrospun into uniform blend nanofibrous mats with good dispersibility. In addition to the principle of multi-jet electro electrospinning, the different devices used for this technique are also highlighted.

1 Introduction

Spinning is an art that has been utilized in formation of yarn by drawing out and twisting natural or synthetic fibers. Thousands of years ago, fibers were spun manually with simple tools as distaff and spindle. The spindle was the first tool used for spinning all the threads used for clothing and fabrics manufacture. In 1738 Lewis Paul was granted a patent for roller drafting spinning machinery [1]. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the ring process was fairly well perfected, and its use was becoming standard throughout the world. Ring spinning is about 250% more productive than mule spinning and is simpler and less expensive to operate so; the mass production arose in the 18th century with the beginnings of the industrial revolution.

Yarns are usually spun from a various materials that could be natural fibers viz., animal and plant fibers, or synthetic ones.

2 Types of spinning

Spinning process is classified according to the fiber types which we want to process into: chemical spinning and mechanical spinning.

Mechanical spinning

Mechanical spinning is a multistep process in which fibers are spun into yarns physically. Viz., rotor, ring, friction, or self-twist spinning.

Chemical spinning

Making filament yarns from man-made fibers is feasible using chemical spinning operations. This is achieved by extruding the viscous polymer solution through a nozzle (spinneret). There are three main types of production processes to form synthetic fibers [2].

The wet-spinning process: in which solidification of the soluble polymer occurs after a counter current diffusion between the spinning dope and the coagulation bath.

The dry-spinning process: where the evaporation of the solvent contained in the spinning dope leads to solidification.

The melt-spinning process: where phase transformation is due to the solidification from a molten mass.

3 Different techniques of chemical spinning

3.1 Wet spinning technique

In this process a very viscous polymer solution is extruded through the small holes of a spinneret dipped in a liquid bath. Technological analysis of the wet spinning process is much more complicated than dry spinning where the spinning process is accompanied by chemical reaction. Solidification of the polymer occurs as a result of a diffusional exchange between the freshly prepared fluid filaments and this bath. During this process coagulation one or more of the bath components diffuse into the filament, while the solvent diffuses out of it [3]. The polymer precipitates or crystallizes as a consequence of this exchange, because it is rendered insoluble by chemical reaction of the polymer or by an excessive buildup of non-solvent or by both [4] (Figure 1).

![Figure 1 Wet-spinning device [3]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_001.jpg)

Wet-spinning device [3]

Wet spinning technique is found to have the advantage of producing reelable fiber that can be drawn and tested for mechanical properties. Its main disadvantages are (a) the slow rate of processing, as the produced filaments need to be washed to remove impurities, and (b) low productivity. Polymers can be regenerated by wet spinning technique like, silk [5] and cellulose [6] by dissolution in ionic liquids, followed by spinning in a coagulating baths of methanol, acetonitrile, or water. Acrylic polymer can be spun by wet spinning technique by dissolving the polymer in dimethyl formamide which can be coagulated in water [4].

3.2 Melt spinning technique

Melt spinning is the most appropriate and economic process for polymer fiber manufacturing at industrial scales. Spinning of polyester, or any other molten polymers like nylon and polypropylene, begins upon cooling the molten filament once it is withdrawn from the spinneret. At the same time, the filament is drawn towards the take-up section and the resulting tension offers a stretching in the molten filament itself [7].

Because the apparent viscosity of the molten filament increases as it cools, most of the stretching takes place in a region relatively close to the spinneret hole, whereas most of the cooling takes place after leaving the hole as shown in Figure 2. The comparatively simple and easy processing is the most important advantage of melt spinning. However, this technique has some drawbacks; Viz. possible fiber breakdown, heterogeneous thickness of the filament, and limit to the fineness of fiber and spinneret clogging.

![Figure 2 Melt-spinning process [8]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_002.jpg)

Melt-spinning process [8]

3.3 Dry spinning technique

In the process of dry spinning, the fiber structure is formed by forcing the polymer solution out through fine nozzle and then evaporating the solvent. Technological analysis of the dry spinning process is much more difficult than of melt spinning which is treated as a problem of structural formation in a one-component system. Unlike melt spinning, in both dry and wet spinning, the polymer dissolves in different solvents and the resulting solution or suspension is viscous spin dope [9]. This process mainly introduces another species, which is consequently removed, and therefore it is more expensive than conventional melt spinning processes. It is used in cases where the polymer may decompose thermally when melted or in cases where specific surface properties of the filaments are desired where melt spinning produces smooth surface filament and dry spinning produces rough surface filament. The rough surfaces may be necessary for better dyeing steps or for special yarn features (Figure 3).

![Figure 3 Dry-spinning process [10]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_003.jpg)

Dry-spinning process [10]

4 Innovative processes for fiber manufacture

A number of processing techniques such as drawing [11], template synthesis [12, 13], phase separation [14], self-assembly [15, 16], electrospinning [17, 18] etc., have been used to prepare nanofibers in recent years. The drawing process is similar to dry spinning in fiber manufacture, as it can make very long single nanofibers. As per its name, the template synthesis uses templates of nanoporous membranes which make solid nanofibers (a fibril) or hollow shape (a tubule). The importance of this method arises from the fabrication of nanometer tubules and fibrils of various raw materials such as semiconductors, metals, and electrically conducting polymers. Unlike drawing process, this method cannot make one-by-one continuous nanofibers. The phase separation process consists of several steps; namely dissolution, gelation, extraction with various solvent, freeze-drying which leads to formation of porous nano-foam. The phase separation process is found to take a relatively long time to convert the polymer into the nano-porous foam. In self-assembly process, the pre-existing components are self-organized to the required forms and functions. Like the phase separation process, the self-assembly is a time-consuming process in spinning continuous polymer nanofibers. Electrospinning is a type of dry spinning technique where the solvent is evaporated under high voltage. Thus, the electrospinning process turns out to be the most developing process for mass production of one-by-one continuous nanofibers from different polymers.

5 Electrospinning and its applications

The process of polymer fiber formation within an electric field has been known since the 1930s. This technique was named electrostatic spinning or electro-spinning in the 1990s. Electro-spinning is the proper method to produce nanofibers [19]. Since 1980s and especially in recent years, the electrospinning process especially similar to that described by Baumgarten [20], has acquired more attention probably due to the excessive interest in nanotechnology, where ultrafine fibers for various polymers with submicrons or nanometer scale can be easily fabricated with this technique. A variety of polymers can be spun each from a specific solution and collected in the form of nonwoven mats. In addition, the ability to produce highly porous nano-fibrous membranes with structural integrity is also an attractive feature of electrospinning [21]. When the diameters of spun fibers are decreased from micro-scale (e.g. 10–100 μm) to submicro-scale or nano-scale (e.g. 10–100 × 10−3 μm), then the fibers exhibit new technically fascinating features; Viz. up to 100% increase in the surface area to volume ratio, enhanced superficial functions, improved mechanical performance, and high porosity. These outstanding properties make the polymer nanofibers to be optimal candidates for many important applications for example in medical applications [22] (viz., wound dressing) [23], membrane separation [24, 25, 26] filtration [25], composite reinforcement [27], scaffolding used in tissue engineering [28] and protective clothing [29].

Electrospinning works with both polymer solutions (solution electro-spinning) and molten polymers (meltelectrospinning).Melt electro-spinning currently seems to be less efficient and requires several additional pieces of equipment (e.g. heating devices, vacuum chamber, and higher voltage power supplies), although it would be more appealing for industrial production because of the absence of solvents [30]. Mowafi et al. have developed a non-woven keratin-based mats extracted from waste keratinous materials; namely wastes of combing process of coarse wool fleece and feather [31]. In another investigation, some biopolymers; such as keratin and cellulose in the nano-fiber form, were used successfully to purify water from heavy metal ions. Extraction of cellulose was carried out by cost-effective environmental friendly method from cotton stalks, banana leaves, and rice straw. Similar method was adopted to extract keratin from coarse wool. The said polymers were electro-sputtered on the surface of untreated viscose fabrics or polyester fabric pretreated with polyurethane [32].

Membranes of electrospun keratin/polyamide 6 blended nanofiber were prepared and used as adsorbents of Cu+2 ions. The adsorption tests showed that keratin-based nanofibers adsorb Cu2+ ions and the adsorption capacity increases as the specific surface area of the nanofiber membranes increase. The adsorption onto the keratin rich nanofibers depend on pH. The optimal pH was found to be above the isoelectric point of keratin [33].

Pure keratin nanofibers can be also electrospun from formic acid solution. The obtained membranes showed higher adsorption capacity and removal efficiency with respect to a wool fabric due to the high specific surface area of keratin nanofibers [34].

Electrospun keratin/polyamide 6 nanofibers were also used for water purification from chromium ions and air depuration from formaldehyde. Infrared analysis and viscosity suggested a negligible interaction between keratin and polyamide 6 despite the similar chemical structure characterized by amide bonds. However, all the blend solutions were suitable for electrospinning producing thin nanofibers with a mean diameter of ~150 nm. Keratin-based nanofibers demonstrated a good capacity to adsorb chromium ions from water. Moreover, keratin-based nanofibers showed a chromium adsorption capacity of one order of magnitude higher than that of the films with the same composition. Keratin-based nanofibers showed a good formaldehyde absorption capacity reducing airborne formaldehyde concentration up to 70% [35].

6 Device and theory

From 1934 to 1944, Formhals published a series of patents [36, 37, 38, 39, 40], describing an experimental setup for the production of polymer filaments using the electrostatic force. A polymer solution was subjected to an electric field between two electrodes of opposite polarity to produce filaments. One of the electrodes was placed into the solution and the other on a collector. Once the polymer left the spinneret, evaporation of the charged solution jets take place forming the fibers. The molecular mass and viscosity of the spinning polymer solution are the main parameters which assign the appropriate potential difference between the two electrodes. The distance between the spinneret and the collector is also an important factor where short distance caused the spun fibers to stick to the collecting device as well as to each other, due to incomplete solvent evaporation. There are three basic components to achieve the process: a high voltage supply, a needle of fine diameter, and a metal collector. In the electrospinning process, a high voltage power supply is used to make an electrically charged jet of polymer out of the needle. Within the distance between the needle and the collector, the polymer jet solidifies, and an interconnected web of very fine fibers is found [41]. Usually, the collector is earthed, as shown in Figure 4.

![Figure 4 Nanofibers formation by electrospinning [41]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_004.jpg)

Nanofibers formation by electrospinning [41]

The charged polymer solution jet is unstable and undergoes elongation, which allows the fiber to become extremely long and thin. In case of melt polymers, solidification of the charged jet takes place while being in the air.

Up to our knowledge, around 50 polymeric materials have been efficaciously electrospun into nano-fibers of diameters in the range 3 nm - 1μm[42, 43]. Before elctrospinning, these polymers were solubilized in the respective appropriate solvents.

7 Multi-jet electrospinning

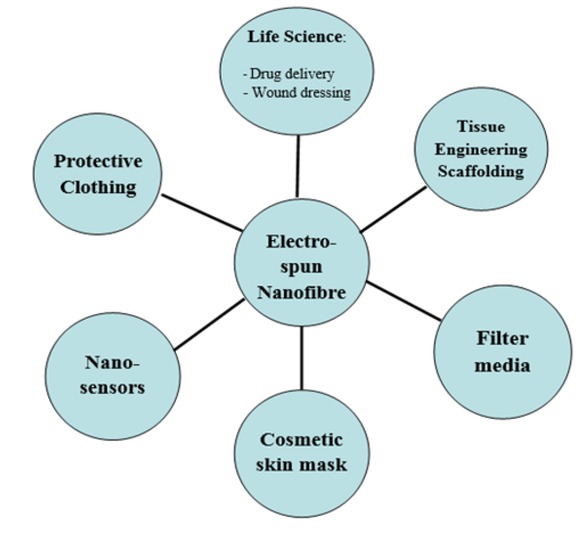

Electro-spun nanofibers have many potential applications as shown in Figure 5, and the production rate of a conventional electrospinning system is less than 10 g h−1 of nanofibers [44], depending on polymer concentration and process conditions (e.g. flow rate of solution). Multi-jet electrospinning systems are designed to increase both productivity and cover area for large scale nanofiber production.

Potential applications of electrospun polymer nanofibers.

It has been reported that, in multi-needles electrospinning can be used to prepare skin-core structures. Formation of nanofiber filaments included two processes: forming process of spun nanofiber filaments and post-drawing process. In the forming process of as-spun nanofiber filaments, when the auxiliary electrode was added, the electrostatic field interference between needles reduced, inducing the decrease of jet offsets and the enhancement of Taylor cone and jet stability, and nanofibers with skin-core structure were finally deposited on the bath in good condition [45].

Electrospun nanofibre jets can be obtained from either multi-nozzle electrospinning device or nozzleless electrospinnnig device. In other words, nanofibre mats can be produced using any of the aforementioned devices.

In our laboratories, we adopted a needleless electrospinning technique with a bottom up configuration. This technique is based on dipping a 30 cm wire with the electrospun polymer and subjecting the wire to a high voltage up to80 KV. The electrospun mat is collected on a nonwoven sheet of polyproplene with width 30cm (Figure 6).

Picture of needleless electro-spinning device at the Textile Research Division, National Research Centre (TRD-NRC) and the jets during the electro-spinning experiment (40 kV nozzles, 13 cm distance, polyamide 6, in a mixture of formic acid and acetic acid)

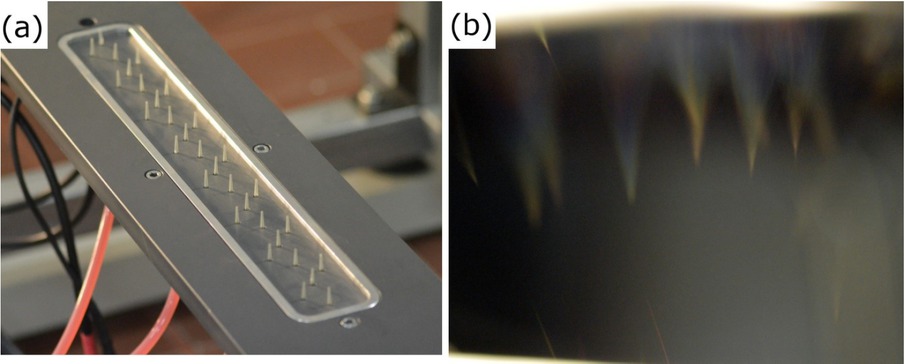

Multi-jet electrospinning device affords the opportunity for electrospinning of multi-component polymers to obtain blend of nanofibrous mats of uniform thickness and adequate dispersibility. This approach also can be used to fabricate blend nanofibrous mats with multi-polymers which cannot be dissolved in the same solvent or kept in the same container [46]. CNR-ISMAC developed a multinozzle electrospinning plant with a bottom-up configuration. It consists of 31 to 62 nozzles and a 50-cm wide metal collector (Figure 7a) [47, 48]. The developed configurations produce overlapped deposition zones in order to have an even nanofiber deposition on the collector.

(a) Picture of 31-nozzle configuration plant at CNR-ISMAC Biella. (b) Picture of jet and whipping motion during a multi-nozzle electrospinning experiment (+35 kV nozzles, −20 kV collectors, 30 cm distance, 9 wt.% PEO solution in water).

In multi-nozzle electrospinning, jet-jet repulsion may occur and can lead to a loss of nanofibers with a decrease in productivity [47], i.e. not all the solidified jets can be collected by the system. In the present plant, each electrospinning nozzle of plant produces an electrified jet. In order to tackle this effect, the metal collector is electrically charged with a polarity opposite to that of the spinneret and jets. In this way nanofibers gathering is more efficient and electrospinning is steady. Figure 7b shows the jets from the straight path to the whipping motion zones before reaching the negatively charged collector.

7.1 Different multi-jet devices

There are two main types of multi-jet electrospinning devices; namely nozzleless electrospinning and nozzles electrospinning. Different setups of these devices were designed by controlling the tips-to-collector distance and the applied voltage (working distance). Either the solution or the collector was electrically charged with positive or negative polarity. Also, varying the number of nozzles or the shape of the multi-jet electrospinning heads were designed for different applications. Some samples of the designed devices for different purposes and applications are presented below.

A device was designed to produce mats of blend nano-fibers with multi-component polymers. The movable multi-jet and movable earthed tubular layer is adopted to obtain a uniform thickness of blend nanofibrous mats with adequate dispersibility of multi-component as in (Figure 10) [46].

A multi-jet electrospinning device was designed either with movable or immovable collector. The rotatable multi-jet and movable earthed tubular layer is adopted to obtain a uniform thickness of blend nanofibrous mats with adequate dispersibility of multi-component [50].

![Figure 8 Schematics diagram of the nozzleless electrospinning setup [© 2016 Sasithorn N, Martinová L, Horáková J, Mongkholrattanasit R] [49].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_008.jpg)

Schematics diagram of the nozzleless electrospinning setup [© 2016 Sasithorn N, Martinová L, Horáková J, Mongkholrattanasit R] [49].

![Figure 9 Scheme of multi-jet electrospinning setups: (a) electrically charged solution and grounded collector, (b) electrically charged collector and grounded solution, and (c) electrically charged solution and grounded collector with secondary electrode [47].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_009.jpg)

Scheme of multi-jet electrospinning setups: (a) electrically charged solution and grounded collector, (b) electrically charged collector and grounded solution, and (c) electrically charged solution and grounded collector with secondary electrode [47].

![Figure 10 Scheme of the multi-jet with multi-nozzles [46].](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0022/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0022_fig_010.jpg)

Scheme of the multi-jet with multi-nozzles [46].

From the previous data about the different types of multi-jet devices, it can be noticed that:

Each device was built to be used in the production of nanofibres of specific properties. Also, the type of device may differ according to the type of spun polymer and its properties viz., molecular weight, viscosity and conductivity. So, it would be more p referable to use nozzleless multijet electrospinning technique for the spinning of highly viscous polymers to avoid the clogging of the needles in the multi-nozzle systems. On the other hand, it is more convenient to use the multi-nozzle system for the spinning of more than one polymer that could be soluble in different media.

8 Different substrates spun by different spinning techniques

In 1968, fiber formation of gelled solution of acrylic polymer was performed by wet spinning method. This process was called coagulation process, where diffusional interchange between the freshly prepared fluid filaments and the liquid bath results in solidification of the polymer [4].

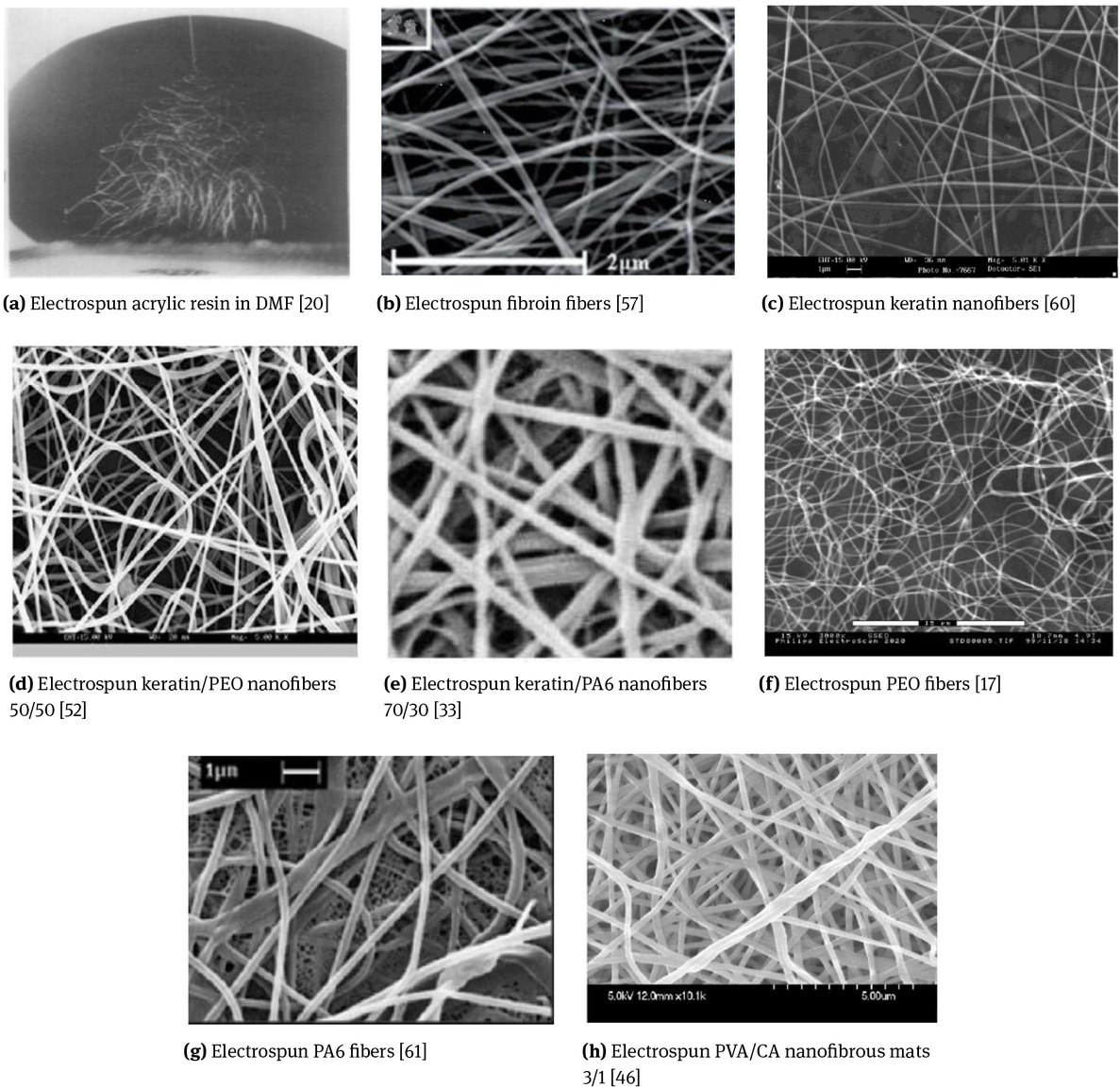

In 1971, fibers from dimethylformamide (DMF) solution of acrylic resin were spun by electrostatic means [20].

In 2001, fiber mats and yarns were electrospun from polyethylene oxide which are of interest for a variety of applications including semipermeable membranes, filters...etc [17].

In 2004, a biodegradable blended nanofibrous mat composed of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and cellulose acetate (CA) was prepared by multi-jet electrospinning [46].

In 2006, polyamide-6 fibers with average diameters below 500 nm were electrospun on conventional air filter media using a multi-nozzle head [51].

In 2008, novel cellulose fibers (Biocelsol) were spun by wet spinning technique from alkaline solution. The fibers were spun into a coagulating bath containing sulphuric acid and sodium sulphate [53].

In 2008, a direct approach to fabricate ceramic fibres of hydrous alumina from alkoxide-based precursors. These fibres were made for various applications that require faster electrospinning rates and lack of impurities from additives. Alkoxide-based solutions formed the backbone of these fibes, where the utilization of the hydrolysis and condensation kinetics allowed for stabilization of the jetn and hence continous fibre formation [54].

In 2012, activated carbon fibre webs (ACF) are prepared from electrospun PAN by air-oxidation stabilization and CO2-activation at different temperatures [55].

In 2016, wet spinning and drawing of human recombinant collagen which lead to significant progress in the field of advanced bio textile-based tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [58].

In 2017, electrospinning was used for the first time to produce nanofibers including a host/guest complex in a protein-based matrix. A lipid binding protein was the host and Irgasan, an insoluble biocide molecule,was bound within the protein internal cavity as the guest [59].

Future outlook

Electrospinning technique can be utilized to produce extremely fine fibers in the form of a non-woven mat. It has been suggested that nanofibers have better mechanical properties than microfibers. So, high productivity using the multi-jet systems is required for practical applications of polymer nanofibers where most of these applications are only considered as future prospect. The possibility of blending more than biopolymer through multi-jet electrospinning would produce nanofibers exhibiting tailored properties for certain desired future applications.

(a-h) show the scanning electron micrographs of some electro-spun polymers.

The huge surface area of the electrospun nanofibers would produce an appropriate candidate for many applications; filtration for instance. Multi-jet electrospun polymer mats can be utilized in the following possible future applications: a) capture of heavy metal ions from highly contaminated effluents, b) absorption of dyes from dye-house drainage water. Within the frame of bio-medical applications; peculiar properties of nanofibrous materials such as high surface to volume ratio and high porosity, make them promising candidates for several biomedical applications, such as cell-growth scaffolds,wound dressing and drug delivery systems.

Acknowledgement

The authors are indebted to the National Research Centre (NRC) of Egypt, and the National Research Council (CNR) of Italy for their financial support through the Joint Bilateral Agreement CNR/NRC (Biennial Programme 2018-2019), project ID: IT II 031001.

References

[1] Rusca R.A., Brown R.A., Some Historical and Technical Aspects of Spinning, Text. Res. J., 1956, 26, 460-469.10.1177/004051755602600611Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Griskey R.G., Polymer Process Engineering, Chapman & Hall, New-York, 1995, Chapter 5, 478.10.1007/978-94-011-0581-1Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Weisser P., Barbier G., Richard C., Drean J.Y., Characterization of the Coagulation Process: Wet-Spinning Tool Development and Void Fraction Evaluation, Text. Res. J., 2015, 86, 1210-1219.10.1177/0040517514551469Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Paul D. R., Diffusion During the Coagulation Step of Wet Spinning, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 1968, 12, 383 - 402.10.1002/app.1968.070120301Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Phillips D.M., Drummy L.F., Naik R.R., De Long H.C., Fox D.M., Trulovec P.C., Mantz R.A., Regenerated Silk Fiber Wet Spinning From an Ionic Liquid Solution, J. Mat. Chem., 2005, 15, 42064208.10.1039/b510069kSuche in Google Scholar

[6] Swatloski R.P., Spear S.K., Holbrey J.D., Rodgers R.D., Dissolution of Celluosewith Ionic Liquids, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 4974-4975.10.1021/ja025790mSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wente V.A., Superfine Thermoplastic Fibers, Ind. Eng. Chem., 1956, 48, 1342-1346.10.1021/ie50560a034Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Pötschke P., Brünig H., Janke A., Fischer D., Jehnichen D., Orientation of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes in Composites with Polycarbonate by Melt Spinning, Polym. J., 2005, 46, 10355 - 10363.10.1016/j.polymer.2005.07.106Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Takajima T., Kajiwara K., McIntyre J.E., Advanced Fiber Spinning Technology, Chapter 1. Fundamentals of Spinning. 1994, p. 8.10.1533/9781845693213.1Suche in Google Scholar

[10] WeiW., Zhang Y., Zhao Y., Luo J., Shao H., Hu X., Bio-Inspired Capillary Dry Spinning of Regenerated Silk Fibroin Aqueous Solution, Mater. Sci. & Eng. C., 2011, 31, 1602-1608.10.1016/j.msec.2011.07.013Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Ondarcuhu T., Joachim C., Drawing a Single Nanofibre over Hundreds of Microns, Euro. Phys. Lett., 1998, 42, 210-220.10.1209/epl/i1998-00233-9Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Feng L., Li S., Li H., Zhai J., Song Y., Jiang L., Zhu D., Super-Hydrophobic Surface of Aligned Polyacrylonitrile Nanofibers, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2002, 41, 1221-1223.10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1221::AID-ANIE1221>3.0.CO;2-GSuche in Google Scholar

[13] Martin C.R., Membrane-Based Synthesis of Nanomaterials, Chem. Mater., 1996, 8, 1739-174610.21236/ADA309882Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Ma P.X., Zhang R., Synthetic Nano-Scale Fibrous Extracellular Matrix, J. Biomed. Mat. Res., 1999, 46, 60-72.10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199907)46:1<60::AID-JBM7>3.0.CO;2-HSuche in Google Scholar

[15] Liu G.J., Ding J.F., Qiao L.J., Guo A., Dymov B.P., Gleeson J.T., Hashimoto T., Saijo K., Polystyrene-Block-Poly (2-Cinnamoylethyl Methacrylate) Nanofibers-Preparation, Characterization, and Liquid Crystalline Properties, Chem-A. European. J., 1999, 5, 2740-2749.10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19990903)5:9<2740::AID-CHEM2740>3.0.CO;2-VSuche in Google Scholar

[16] Whitesides G.M., Grzybowski B., Self-Assembly at all Scales, Science., 2002, 295, 2418-2421.10.1126/science.1070821Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Deitzel J.M., Kleinmeyer J., Hirvonen J.K., Beck T.N., Controlled Deposition of Electrospun Poly (Ethylene Oxide) Fibers, Polymer., 2001, 42, 8163-8170.10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00336-6Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Fong H., Reneker D.H., Electrospinning and Formation of Nanofibers, Salem D.R., editor; Structure Formation in Polymeric Fibers, Munich: Hanser., 2001, 225-246.10.3139/9783446456808.006Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Aluigi A., Varesano A., Montarsolo A., Vineis C., Ferrero F., Mazzuchetti G., Tonin C., Electrospinning of Keratin/Poly(ethylene oxide) Blend Nanofibers, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2007,104, 863-870.10.1002/app.25623Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Baumgarten P.K., Electrostatic Spinning of Acrylic Microfibers, J. Coll. Int. Sci., 1971, 36, 71-79.10.1016/0021-9797(71)90241-4Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Thorvaldsson A., Stenhamre H., Gatenholm P., Walkenström P., Electrospinning of Highly Porous Scaffolds for Cartilage Regeneration, Biomacromol., 2008, 9, 1044-1049.10.1021/bm701225aSuche in Google Scholar

[22] Al-Enizi A.M., Zagho M.M., Elzatahry A.A., Polymer-Based Electrospun Nanofibers for Biomedical Applications, Nanomater., 2018, 8, 259-281.10.3390/nano8040259Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Uppal R., Ramaswamy G.N., Arnold C., Goodband R., Wang Y.J., Hyaluronic Acid Nanofiber Wound Dressing-Production, Characterization, and In Vivo Behavior, Biomed. Mater. Res. B: Appl. Biomater., 2011, 97B, 20-29.10.1002/jbm.b.31776Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Shin C., Chase G.G., Reneker D.H., The Effect of Nanofibers on Liquid-Liquid Coalescence Filters Performance, AICHE. J., 2005, 51, 3109-311310.1002/aic.10564Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Gopal R., Kaur S., Ma Z., Chan C., Ramakrishna S., Matsuura T., Electrospun Nanofibrous Filtration Membrane, J. Membr. Sci., 2006, 281, 581-586.10.1016/j.memsci.2006.04.026Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Gibson P., Schreuder-Gibson H., Rivin D., Transport Properties of Porous Membranes Based on Electrospun Nanofibers, Colloids. Surf. A Physico. Chem. Eng. Asp., 2001,187, 469-481.10.1016/S0927-7757(01)00616-1Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Bhatnagar A., Sain M., Processing of Cellulose Nanofiber-Reinforced Composites, J. Rein. Plast. & Compos., 2005, 24, 1259-1268.10.1177/0731684405049864Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Min B.M., Lee G., Kim S.H., Nam Y.S., Lee T.S., Park W.H., Electro-spinning of Silk Fibroin Nanofibers and Its Effect on the Adhesion and Spreading of Normal Human Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts In Vitro, Biomat., 2004, 25, 1289-1297.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.045Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lee S., Obendorf S.K., Use of Electrospun Nanofiber Web for Protective Textile Materials as Barriers to Liquid Penetration, Text. Res. J., 2007, 77, 696-702.10.1177/0040517507080284Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Varesano A., Rombaldoni F., Mazzuchetti G., Tonina C., Comottob R., Multi-jet Nozzle Electrospinning on Textile Substrates: Observations on Process and Nanofibre Mat Deposition, Polym. Int., 2010, 59, 1606-1615.10.1002/pi.2893Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Mowafi S., AbouTaleb M., Abou El-Kheir A., El-Sayed H., Electrospun Keratin/Polyvinyl Acohol Regenerated Fibres Part 1: Preliminary Study, J. Nat. Fib., 2013,10, 341-352.10.1080/15440478.2013.816253Suche in Google Scholar

[32] El-Sayed H., El-Gabry L., Ibrahim H.S., El-Sayed A.A., Abou Taleb E.M., Ammar N.S., Salama M., Abou El-Kheir A., Mowafi S., AbouTaleb M., Treatment of Selected Man-made Fabrics with biopolymers and Their Utilization in Removal of Copper II Cations from Industrial Wastewater, Proc. of the 9th Aachen Dresden Int. Textile Conf., Aachen, German., 2015, Nov 26-27.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Aluigi A., Tonetti C., Vineis C., Tonin C., Mazzuchetti G., Adsorption of Copper (II) Ions by Keratin/PA6 Blend Nanofibres, Europ. Polym. J., 2011, 47, 1756-1764.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2011.06.009Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Aluigi A., Tonetti C., Vineis C., Tonin C., Casasola R., Ferrero F.J., Wool Keratin Nanofibres for Copper(II) Adsorption, Biobased Mater. Bioenergy., 2012, 6, 1-7.10.1166/jbmb.2012.1204Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Aluigi A., Vineis C., Tonin C., Tonetti C., Varesano A.,Mazzuchetti G., Wool Keratin-Based Nanofibres for Active Filtration of Air and Water, J. Biobased. Mater. Bioenergy., 2009, 3, 1-910.1166/jbmb.2009.1039Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Formhals A. US patent 1934, 1,975,504.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Formhals A. US patent 1939, 2,160,962.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Formhals A. US patent, 1940, 2,187,306.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Formhals A. US patent, 1943, 2,323,025.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Formhals A. US patent, 1944, 2,349,950.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Huang Z.M., Zhang Y.Z., Kotaki M., Ramakrishn S., Review on Polymer Nanofibers by Electrospinning and Their Applications in Nanocomposites, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2003, 63, 2223-2253.10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00178-7Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Ramirez D.S., Carletto R.A., Giachet F.T., Keratin Processing. In Keratin as a Protein Biopolymer, Springer, Cham., 2019, 77-121.10.1007/978-3-030-02901-2_4Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Zhong C., Cooper A., Kapetanovic A., Fang Z., Zhanga M., Rolandi M., A Facile Bottom-Up Route to Self-Assembled Biogenic Chitin Nanofibers, Soft Matter., 2010, 6, 5298-5301.10.1039/c0sm00450bSuche in Google Scholar

[44] Tsai P.P., Schreuder-Gibson H., Gibson P., Different Electrostatic Methods for Making Electret Filters, J. Electrostat., 2002, 54, 333-341.10.1016/S0304-3886(01)00160-7Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Tian L., Yan T., Li J., Pan Z., Novel Aspects of Nanofibers, Chapter 2: Nanofiber Filaments Fabricated by a Liquid-Bath Electrospinning Method. Edited by Lin T., Intech. Open Ltd, London, UK, 2018.10.5772/intechopen.75197Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Ding B., Kimura E., Sato T., Fujita S., Shiratori S., Fabrication of Blend Biodegradable Nanofibrous Nonwoven Mats Via Multi-Jet Electrospinning, Polym. J., 2004, 45, 1895-1902.10.1016/j.polymer.2004.01.026Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Varesano A., Carletto R.A., Mazzuchetti G., Experimental Investigations on the Multi-Jet Electrospinning Process, J. Mater. Process. Technol., 2009, 209, 5178-5185.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2009.03.003Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Varesano A., Rombaldoni F., Mazzuchetti G., Tonin C., Comotto R., Multi-jet Nozzle Electrospinning On Textile Substrates: Observations On Process and Nanofibremat Deposition, Polym. Int., 2010, 59, 1606-1615.10.1002/pi.2893Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Sasithorn N., Martinová L., Horáková J., Mongkholrattanasit R., Fabrication of Silk Fibroin Nanofibres by Needleless Electrospinning. In Electrospinning-Material, Techniques, and Biomedical Applications, InTech., 2016, 95-113.10.5772/65835Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Tomaszewski W., Szadkowski M., Investigation of Electrospinning with the Use of a Multi-jet Electrospinning Head, Fibres. Text. East. Eur., 2005, 52, 22-26.Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Li L., Frey M.W., Green T.B., Modification of Air Filter Media with Nylon-6 Nanofibers, J. Eng. Fib. Fab., 2006, 1, 1-23.10.1177/155892500600100101Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Aluigi A., Vineis C., Varesano A.,Mazzuchetti G., Ferrero F., Tonin C., Structure and Properties of Keratin/PEO Blend Nanofibres, Eur. Polym. J., 2008, 44, 2465-2475.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.06.004Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Vehviläinen M., Kamppuri T., Rom M., Janicki J., Ciechańska D., Grönqvist S., Siika-Aho M., Christoffersson K.E., Nousiainen P., Effect of Wet Spinning Parameters on The Properties of Novel Cellulosic Fibres, Cellulose., 2008, 15,671-680.10.1007/s10570-008-9219-3Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Maneeratana V., Sigmund W.M., Continuous Hollow Alumina Gel Fibres by Direct Electrospinnig of An Alkoxide-Based Precursor, Chem. Eng. J., 2008,137, 137-143.10.1016/j.cej.2007.09.013Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Wang G., Pan C., Wang L., Dong Q., Yu C., Zhao Z., Qiu J., Activated Carbon Nanofibre Webs Made by Electrospinning for Capacitive Deionization, Electrochimica Acta., 2012, 69, 65-70.10.1016/j.electacta.2012.02.066Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Khan M.M., Tsukada M., Zhang X., Morikawa H., Preparation and Characterization of Electrospun Nanofibers Based on Silk Sericin Powders, J. Mater. Sci., 2013, 48, 3731-3736.10.1007/s10853-013-7171-6Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Tanha N.R., Nouri M., An Experimental Study On The Coaxial Electrospinning of Silk Fibroin/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)- Salicylic Acid Core-Shell Nanofibers and Process Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology, J. Indust. Text., 2018, 48(5), 884-903.10.1177/1528083717747334Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Yaari A., Schilt Y., Tamburu C., Raviv U., Shoseyovt O., Wet Spinning and Drawing of Human Recombinant Collagen, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng., 2016, 2, 349-360.10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00461Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Tomaselli S., Ramirez D.S., Carletto R.A., Varesano A., Vineis C., Zanzoni S., Molinari H., Ragona L., Electrospun Lipid Binding Proteins Composite Nanofibers with Antibacterial Properties, Macromol Biosci., 2017,17, 1-6.10.1002/mabi.201600300Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] El-Sayed H., Vineis C., Abou Taleb M., Varesano A., Mowafi S., Carletto R.A., (un-published data)Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Aluigi A., Varesano A., Vineis C., Rio A.D., Electrospinning of Immiscible Systems: The Wool Keratin/Polyamide-6 Case Study, Mater. Desig., 2017, 127, 144-153.10.1016/j.matdes.2017.04.045Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 H. El-Sayed et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Investigation of rare earth upconversion fluorescent nanoparticles in biomedical field

- Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries

- Insight into the working wavelength of hotspot effects generated by popular nanostructures

- Novel Lead-free biocompatible piezoelectric Hydroxyapatite (HA) – BCZT (Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3) nanocrystal composites for bone regeneration

- Effect of defects on the motion of carbon nanotube thermal actuator

- Dynamic mechanical behavior of nano-ZnO reinforced dental composite

- Fabrication of Ag Np-coated wetlace nonwoven fabric based on amino-terminated hyperbranched polymer

- Fractal analysis of pore structures in graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based cementitious pastes under different ultrasonication

- Effect of PVA fiber on durability of cementitious composite containing nano-SiO2

- Cr effects on the electrical contact properties of the Al2O3-Cu/15W composites

- Experimental evaluation of self-expandable metallic tracheobronchial stents

- Experimental study on the existence of nano-scale pores and the evolution of organic matter in organic-rich shale

- Mechanical characterizations of braided composite stents made of helical polyethylene terephthalate strips and NiTi wires

- Mechanical properties of boron nitride sheet with randomly distributed vacancy defects

- Fabrication, mechanical properties and failure mechanism of random and aligned nanofiber membrane with different parameters

- Micro- structure and rheological properties of graphene oxide rubber asphalt

- First-principles calculations of mechanical and thermodynamic properties of tungsten-based alloy

- Adsorption performance of hydrophobic/hydrophilic silica aerogel for low concentration organic pollutant in aqueous solution

- Preparation of spherical aminopropyl-functionalized MCM-41 and its application in removal of Pb(II) ion from aqueous solution

- Electrical conductivity anisotropy of copper matrix composites reinforced with SiC whiskers

- Miniature on-fiber extrinsic Fabry-Perot interferometric vibration sensors based on micro-cantilever beam

- Electric-field assisted growth and mechanical bactericidal performance of ZnO nanoarrays with gradient morphologies

- Flexural behavior and mechanical model of aluminum alloy mortise-and-tenon T-joints for electric vehicle

- Synthesis of nano zirconium oxide and its application in dentistry

- Surface modification of nano-sized carbon black for reinforcement of rubber

- Temperature-dependent negative Poisson’s ratio of monolayer graphene: Prediction from molecular dynamics simulations

- Finite element nonlinear transient modelling of carbon nanotubes reinforced fiber/polymer composite spherical shells with a cutout

- Preparation of low-permittivity K2O–B2O3–SiO2–Al2O3 composites without the addition of glass

- Large amplitude vibration of doubly curved FG-GRC laminated panels in thermal environments

- Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide

- Correlation between electrochemical performance degradation and catalyst structural parameters on polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell

- Materials characterization of advanced fillers for composites engineering applications

- Humic acid assisted stabilization of dispersed single-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Test on axial compression performance of nano-silica concrete-filled angle steel reinforced GFRP tubular column

- Multi-scale modeling of the lamellar unit of arterial media

- The multiscale enhancement of mechanical properties of 3D MWK composites via poly(oxypropylene) diamines and GO nanoparticles

- Mechanical properties of circular nano-silica concrete filled stainless steel tube stub columns after being exposed to freezing and thawing

- Arc erosion behavior of TiB2/Cu composites with single-scale and dual-scale TiB2 particles

- Yb3+-containing chitosan hydrogels induce B-16 melanoma cell anoikis via a Fak-dependent pathway

- Template-free synthesis of Se-nanorods-rGO nanocomposite for application in supercapacitors

- Effect of graphene oxide on chloride penetration resistance of recycled concrete

- Bending resistance of PVA fiber reinforced cementitious composites containing nano-SiO2

- Review Articles

- Recent development of Supercapacitor Electrode Based on Carbon Materials

- Mechanical contribution of vascular smooth muscle cells in the tunica media of artery

- Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field

- Toxicity of metallic nanoparticles in the central nervous system

- Parameter control and concentration analysis of graphene colloids prepared by electric spark discharge method

- A critique on multi-jet electrospinning: State of the art and future outlook

- Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity - A mini review

- Recent progress in supercapacitors based on the advanced carbon electrodes

- Recent progress in shape memory polymer composites: methods, properties, applications and prospects

- In situ capabilities of Small Angle X-ray Scattering

- Review of nano-phase effects in high strength and conductivity copper alloys

- Progress and challenges in p-type oxide-based thin film transistors

- Advanced materials for flexible solar cell applications

- Phenylboronic acid-decorated polymeric nanomaterials for advanced bio-application

- The effect of nano-SiO2 on concrete properties: a review

- A brief review for fluorinated carbon: synthesis, properties and applications

- A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test

- Cotton fibres functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles to promote the destruction of harmful molecules: an overview