Abstract

The necessity for a shift to alternative forms of energy is highlighted by both approaching consequences of climate change and limited availability of fossil fuels. While a large portion of energy required can be generated by solar and wind, a diverse, sustainable energy generation mix is still necessary to meet our energy needs. By capturing otherwise lost heat energy and turning it into valuable electrical energy, thermoelectric can play a significant part in this. Using the Seebeck effect, thermoelectric generators (TEG) have established their capability to transform thermal energy into electrical energy directly. Furthermore, because they do not include chemical compounds, they are silent in operation and can be built on various substrates, including silicon, polymers, and ceramics. Moreover, thermoelectric generators have a long operational lifetime, are position independent, and may be integrated into bulky, flexible devices. However, the low conversion efficiency of TEG has confined their broad application, hampering them to an academic subject. Until now, recent developments in thermoelectric generators and devices are presuming the technology to catch its place among state-of-the-art energy conversion systems. This review presents the commonly used methods for producing thermoelectric modules (TEMs) and the materials currently studied for TEMs in bulk and printed thermoelectric devices.

1 Introduction

Seebeck made the initial discovery of the thermoelectric phenomena in 1821. By heating the connection between two separate electrical conductors, he demonstrated how to create an electromotive force. It is discovered that the meter registers a minor voltage when the connection between the wires is heated. It has been determined that the size of the thermoelectric voltage is proportional to the difference in temperature between the connections to the meter and the thermocouple junction. The second of the thermoelectric effects was noticed by French watchmaker Peltier 13 years after Seebeck made his discovery. He discovered that depending on the direction of the electric current, passing through a thermocouple results in a minor heating or cooling impact. Since the Joule heating effect always accompanies the Peltier effect, it is very challenging to show the Peltier effect using metallic thermocouples. Showing less heating when the current is transmitted in one way instead of the other is often all that can be done. The Peltier effect may be theoretically illustrated using the setup in Figure 1 by exchanging the meter for a direct current source and mounting a tiny thermometer on the thermocouple junction. The thermoelectric (TE) is explained using the aforementioned phenomena [1,2,3]. These three phenomena and Joule effect provide the physical foundation for TE transformation procedures [4]. Seebeck observed a magnetic field surrounding the two distinct metal wires in a loop when he warmed up one connection but kept the other at a low temperature (Figure 1(a) and (b)). The formation of the magnetic field due to the temperature difference between two junctions was named thermo-magnetism.

![Figure 1

(a) Experimental observation and (b) seebeck effect, reproduced with the permission of Chen et al. [5].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_001.jpg)

(a) Experimental observation and (b) seebeck effect, reproduced with the permission of Chen et al. [5].

A further explanation was offered by Oersted, whose experiment showed that the magnetic field near the circuit was unaffected by the temperature change. The temperature variation produced a voltage V ab and an electric current in the circuit, which produced the experiment’s magnetism. The formation of electric current due to the temperature difference was named thermoelectricity [6]. Seebeck first identified the phenomenon; since then, it has been referred to as the Seebeck (Sb). The Seebeck effect, which explains the phenomenon of the carrier’s directly pumping heat, is the reverse of the Peltier effect. Additional heat will be released or absorbed at these two junctions in addition to the Joule heat created when a current is applied to a circuit of two conductors. Since J. C. A. Peltier, a French physicist, first identified this effect in 1834, it has been named after him.

He connected the Bi and Sb wires and observed how a metal connection caused water droplets to condense when an electric current was sent across the circuit. When the current turned around, the ice disintegrated (Figure 2a). When electric current applied at junction of two different Fermi-level conductors, the electrons will either jump from the high to the low or in the opposite direction across the interface potential barrier [7]. They will absorb or release energy in the form of heat at the junction (Figure 2b). It was not until 1855 that William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) recognized this issue as being related to the link between the Seebeck and Peltier effects [8]. He reasoned that there must also be a third effect. In addition to the Joule heat, a uniform conductor should experience reversible heat absorption or release as an electric current passes through it. The Thomson effect was introduced in 1867 after this effect had been empirically verified. Several research works take the constant value of Thomson coefficients and establish that the coefficient showed a significant impression on the efficiency of thermoelectric generators (TEGs). Subsequently, Yamashita et al. [9] investigated the linear temperature-dependent effect of TE materials on TEG performance. The asymptotic solution to the nonfundamental heat control equation for TE materials was proposed by Sandoz-Rosado et al., [10] and the equations were derived from the temperature-dependent cumulative model incorporating Thomson’s effect by Kim et al. [11].

![Figure 2

(a–c) The Peltier effect, reproduced with the permission of Chen et al. [5].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_002.jpg)

(a–c) The Peltier effect, reproduced with the permission of Chen et al. [5].

2 Thermoelectric devices

Thermoelectric devices are like heat engines. Their efficiency constraint is comparable to the Carnot efficiency [12]. According to the Carnot cycle [13], the energy can be absorbed or dumped from a high- or low-temperature reservoir; it cannot be taken from room temperature. Because of the trade-off between efficiency and power that applies to all heat engines, achieving the Carnot efficiency at finite power is complicated. It is noted that without violating the trade-off relation, the Carnot efficiency at finite power might be reached in the vanishing limit of a system’s relaxation times. The TEG characteristic and outputs not only depend on the Carnot efficiency but also on the dimensionless parameter of material called a figure of merit (ZT) [14]. This dimensionless parameter depends on numerous material characteristics such as temperature [15], Seebeck coefficient [16], electrical [17], and thermal conductivity [18]. Modern TE device designs, including traditional TE module design, flexible device design, microdevice design, and applications in various sectors, require high-efficiency levels. TE devices for power generation have received significant attention due to their high reliability, solid-state operation, and stability. When designing thermoelectric power generation devices, it is necessary to consider design principles, fabrication techniques and testing methods, interface optimization, barrier layer design, electrode fabrication, protective coatings, and component and module estimation aspects of TE devices. These TE designs depend on elegant, dimensional designs that guarantee excellent stability and performance [19]. Environmental factors that may harm or improve device performance include oxidation, magnet fields, pressure, and radiation.

Usually, the metal-electrode links n- and p-type TE material to form the TE module (element) [20]. TE devices are created by joining many TE modules in series electrically and in parallel thermally due to the low output voltage of a single TE module [21]. The device is usually assembled by soldering a copper electrode to the ceramic sheet with a thermally conductive surface that acts as the electrical insulating board for both the cold and hot ends. A copper sheet is directly adhered to a ceramic substrate using the copper-cladding technique in a preset pattern [22]. The n- and p-type thermoelectric modules (TEMs) are linked using standard soldering methods to fabricate a sandwich structure. The wettability of TE can be improved with the help of Nickel, which can be used in solders and soldering surfaces. Solder alloys are essential for the fabrication of integrated circuits and electronic devices. Nickel solders are popular because of their low melting point, superior solderability, and low price [23]. Despite the simplicity and low cost of this preparation procedure, the use of ceramic leads to brittleness and mechanical stress.

For the construction of thermoelectric devices (TEDs), complex electrode preparation techniques such as arc-spraying [24], high-temperature diffusion welding [25], and a combination with Spark plasma sintering [26] have been adopted. The TE device can work at temperatures that are not constrained by the melting point of the solder when using the arc-spraying technique, which shows outstanding thermal stability [27]. A transition or intermediary layer is often formed on the electrode connection surface of TEMs in the interim to facilitate interface bonding. The arc spraying apparatus also has good mechanical stress resistance because the TEMs are fastened and packed in the gap between the frame and electrode. Recently, a one-step method for producing devices was developed that uses hot pressing or SPS to concurrently make n-type and p-type materials and sinter electrodes [28], barrier [29], and TEMs [30]. Using integrated methods, creating low interface contact resistance and high-strength bonding of TEMs and electrodes is straightforward. TEDs are divided into three types: π-type [31], O-type [32], and Y-type [5], based on their diverse designs [33]. The TE gadget of the π-type is the most well-known of them (Figure 3).

![Figure 3

(a) π-shaped TE module, (b) tube-shaped TE module, and (c) Y-shaped TE module, reproduced with the permission of Yubing et al. [34].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_003.jpg)

(a) π-shaped TE module, (b) tube-shaped TE module, and (c) Y-shaped TE module, reproduced with the permission of Yubing et al. [34].

The TE modules in π-type TE devices are housed within two efficient heat-conducting electrically insulated ceramic panels [34]. The heat flow is generally directed to a ceramic flat plate, which is appropriate for a flat source of heat’s operational environment [35]. Unidirectional heat flow makes it simple to establish uniform heat flow density in TEMs [36], and the best structure design can enhance the TE performance to achieve high efficiency. However, a TE device frequently constrains cold and hot surfaces. The temperature change caused severe thermal stress and impaired the structure’s endurance due to the different thermal expansion of other materials [37]. In an O-type TE device, the columnar heat source alternates coaxially with n- and p-type TEMs [26]. The annular insulation material’s layer is positioned in the middle of each layer of TE material to establish electrical isolation between the adjacent layers [38]. In addition, metal coil electrodes are used to connect nearby TEMs. In particular, a radial heat flow is observed in the cylindrical heat source. Therefore, a ring-like TE device is suitable for nonflat heat sources. However, the efficient design of electric fields and temperature makes achieving the radial heat flow and current difficult. Compared to a flat device, welding of specifically shaped TEM, metal electrodes, and device integration is much more complex, and the production cost is significantly higher [26].

In Y-type TED, connecting electrodes contain cylindrical or rectangular n- and p-type TEM. The connection plates of electrodes offer conductive channels for nearby n- and p-type TEM and function as heat-collecting and transmission devices [40]. The lateral series thermal expansion of n- and p-type TEM avoids stress concentration due to variations in expansion coefficients and provides better freedom in TEM design parameters [41]. Furthermore, the Y-type construction allows each TE module to be individually optimized structurally [42]. TEM could have a variety of sizes in terms of structure interface and height, which is advantageous in the fabrication of divided structures. The heat and current density nonuniformity flow in Y-shaped TED influenced the efficiency of the TEM materials and shrink device performance [39].

Figure 4 depicts the basic design criteria for TED, which applies to all TED types. The flow diagram shows that the device’s topological layout directly impacts output attributes, such as device energy density. As a result, matching the device topologies under real operating conditions is the foundation for optimizing a TE power-generating system’s comprehensive indicators [43]. The limits and affecting elements must be thoroughly studied depending on the operating mode of the TED. In the device design phase, it is critical to incorporate mathematical investigation, thermal-electric structure coupling inquiry, finite element numerical modeling, and transient structure analysis [44]. Several interconnected structural parameters must be optimized simultaneously following the device’s overall modeling. The efficiency of TED’s energy is affected by the TEM performance and the difference in temperature between the two ends of the materials and by their size [45]. When different resistivity of the p- and n-type TEM composes a TE unit, the performance is reduced, which can be countered by adopting two TE “legs.” In general, the finite element approach is beneficial for resolving such problems. When a temperature gradient (ΔT) is introduced, the change carriers (electrons for n-type materials and holes for p-type materials) starts moving from the hot side and diffuse to the cold side, this phenomenon is called material’s TE energy-harvesting mechanism. An electrostatic potential (ΔV) is consequently created. A solitary n- or p-type TE leg produces an extremely low electrostatic potential (varying from μV to mV depending upon the situation). TE generators are usually composed of dozens or even hundreds of TE couples to gain high output voltage and power.

![Figure 4

The flowchart description of the basic design criteria for TED, reproduced with the permission of Deepthi [39].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_004.jpg)

The flowchart description of the basic design criteria for TED, reproduced with the permission of Deepthi [39].

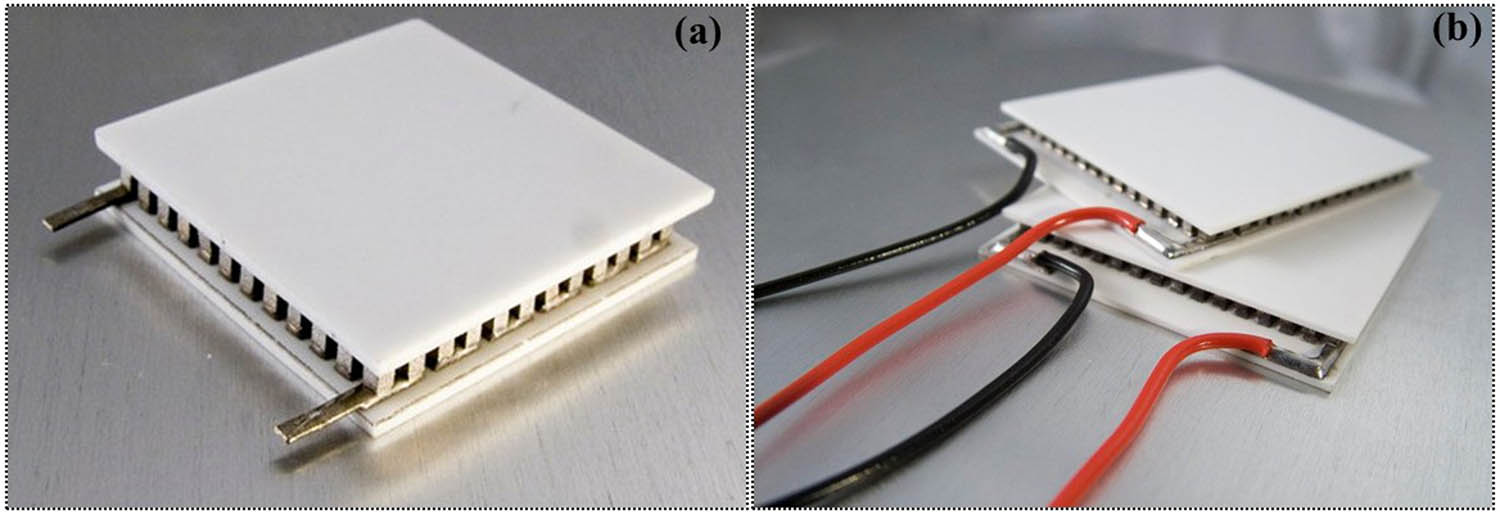

Furthermore, a single TEM’s ideal working temperature range is frequently small [46]. The efficiency is limited when utilizing a single TEM [47]. Every material has different physical characteristics; therefore, the degree of nonlinearity increases in temperature distribution. In the case of segment TED’s, they have many interfaces and complicated topologies, making it challenging to optimize device performance. Another critical component to consider in designing the device is the fill factor (F), which is the ratio of the TEM to the area of the ceramic plate [48]. In general, F must be optimized to maximize efficiency [49]. The link between electrodes and TEM is critical in TED design, particularly for high-temperature electrodes [50]. Because TEDs may remain in service for lengthy durations, interdiffusion and chemical reactions take place at the interfaces of high-temperature electrodes and TEM interfaces [51]. This reduces the efficiency due to increased electrical and thermal resistance. The reasonable remedy for this problem is to place a suitable transition layer between the electrodes and the TEMs, acting as a diffusion barrier [52]. In low temperatures, TED’s transition layer’s purpose is to increase solder and material’s wettability. It also helps reduce thermal and interface resistance. However, its selection and design are much more complicated in the case of high-temperature TEDs [53]. Here is the real example of TEM and TEG in daily life as shown in Figure 5.

(a) Thermoelectric module and (b) thermoelectric generator.

3 Nano-particle (Na-Par) preparation methods

In this section, we present some of the commonly used methods for preparing the TEMs.

3.1 Hydrothermal (HD) method

One of the most popular and efficient ways to create nano-materials (Nan-Mat) with diverse morphologies is HD. This method uses an autoclave to conduct the reaction at high temperatures and pressures while using water or an organic substance as the reactants. The name “hydrothermal process” (HD) refers to the use of water throughout the preparation process [54,55]. Comprehensive discussions on various autoclave types and their purposes have also been reported in the literature [56,57]. Teflon-lined autoclaves can often withstand high temperatures and pressures [58]. Compared to glass and quartz autoclaves, it tolerates alkaline media and greatly resists hydrofluoric acid. A Teflon-lined autoclave is the best container to react under the necessary circumstances. The main element that makes it possible to synthesize different nanostructured inorganic materials during the HD process is precise control [59]. This technique can stimulate hydrolysis by crystal growth, resulting in the self-assembled Nan-Mat in solution. It can also facilitate and speed up the interaction between the reactants. In addition, it is simple to tune the characteristics, morphology, size, and structure of Nan-Mat by adjusting the various parameters, such as temperature, reactant concentration, reaction medium, pressure, pH, reactant concentration, reaction time, as well as the filled capacity of the autoclave. The following steps are part of the HD synthesis process: (i) preparing precursors by combining soluble metal salt using aqueous solution, (ii) combining the solution into an autoclave to start the reactions at an elevated temperature and pressure, and (iii) finalizing the process by filtering, washing, and then drying [60]. Many Nan-Mat have been studied using the HD technique [61–79].

3.2 Sol–gel method

Currently, numerous methods and techniques are employed to produce nano-materials. However, the sol–gel technique is mainly used for industrial purposes because of its more comprehensive range of applications [80,81,82,83,84]. The industrial-level employment of this technique is due to producing high-quality nanoparticles in large quantities [85,86,87]. It is also used for metal oxide nanoparticles and mixed oxide composites. The surface and textural characteristics of the materials might be manipulated using this technique. The sol–gel procedure primarily goes through three steps to get the final metal oxide treatments: drying [88], hydrolysis [89], and condensation [90]. The process of creating metal oxide comprises many sequential processes (Figure 6).

![Figure 6

(a) Hydrothermal process, (b) Cold pressing and (c) Hot pressing, reproduced with the permission of Liu et al. [79].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_006.jpg)

(a) Hydrothermal process, (b) Cold pressing and (c) Hot pressing, reproduced with the permission of Liu et al. [79].

First, the matching metal precursor quickly hydrolyzes to generate a metal hydroxide solution, which is immediately condensed to form 3D gels. Depending on the drying method, the resultant gel can be transformed into Xerogel or Aerogel [91]. Depending on the solvent used, the sol–gel process may be divided into two categories: aqueous sol–gel and nonaqueous sol–gel [92]. The aqueous sol–gel technique uses water as the reaction medium, whereas the nonaqueous sol–gel technique uses organic solvents for reaction media. Figure 7 depicts the chemical route used in the sol–gel process to produce metal oxide nanostructures [93]. The metal precursor and solvent composition in the sol–gel process is essential for creating metal oxide Na-Par. In the aqueous sol–gel method, water solvent provides the oxygen, which is required for the formation of metal oxide. Typically, the metal precursors used in this process include metal acetates and nitrates. However, due to the strong attraction of alkoxides to water, metal alkoxides are often utilized as precursors for forming metal-oxide nanoparticles [94,95]. The aqueous sol–gel approach does come with specific challenges, though. In various situations, the crucial steps – hydrolysis, condensation, and drying – occur concurrently, making it challenging to regulate particle shape and ensure reproducibility of the end procedure during the sol–gel method [96]. The nonaqueous sol–gel technique uses solvents such as ketones, aldehydes, alcohols, or metal precursors to provide the oxygen needed to create metal oxide.

![Figure 7

Sol–gel method, reproduced with the permission of Adschiri et al. [100].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_007.jpg)

Sol–gel method, reproduced with the permission of Adschiri et al. [100].

These organic solvents also deliver oxygen while providing a flexible tool for adjusting several essential factors, including the final oxide material’s composition, particle size, surface characteristics, and morphology. Although nonaqueous sol–gel approaches are less well known than aqueous sol–gel approaches, they have demonstrated superior effects on synthesizing nano-oxides compared to aqueous sol–gel process. The generation of metal oxide nanoparticles, a non-aqueous sol–gel pathway, may be separated into two key strategies: surfactant-controlled and solvent-controlled approaches [93]. The hot injection approach uses a surfactant-controlled strategy that directly transforms metal precursor into metal oxide at higher temperatures. Some recent examples are as follows: Bi2Te3 is one of the most widely used materials for thermoelectric applications due to its high thermoelectric efficiency. Sol–gel methods can synthesize Bi2Te3 nanoparticles or thin films, which can then be assembled into TEMs.

Similarly, the PbTe is another commonly used thermoelectric material, especially in high-temperature applications. Sol–gel techniques can fabricate PbTe nanoparticles or thin films for constructing TEMs. Also, the SiGe alloys exhibit good thermoelectric properties, particularly at elevated temperatures. Sol–gel processes can deposit SiGe thin films or nanoparticles, which can be integrated into TEMs. Sam as copper selenide is an emerging thermoelectric material known for its nontoxicity and earth abundance. This method can synthesize Cu2Se nanoparticles or thin films, which can be incorporated into TEMs. This technique eliminates particle agglomeration and allows for excellent control over the formation and development of the Na-Par [93].

3.3 Polyol method

Different types of Na-Par with various morphologies have been created using several potential synthetic techniques [97]. Among these, the polyol approach is a flexible liquid-phase technique that uses multivalent alcohols and high boiling to create Na-Par [98]. Polyols can regulate the development of particles in addition to acting as a solvent and reducing agent. The Fievets group adopted the word polyol for synthesizing metal nanoparticles in 1989, which marked the beginning of the polyol synthetic pathway. This process has been used with various polyols, including diethylene, ethylene, propylene, triethylene, tetraethylene, butylene, and polyethylene glycol. Moreover, Carroll et al. synthesized elemental copper and nickel nanoparticles using the polyol method and investigated further with theoretical calculations [99]. However, polyols offer fantastic benefits in several ways. Several reports have been published using polyol methods, such as Grisaru et al. who reported the microwave-assisted polyol method was quite impressive for the fabrication of CuInTe2 and CuInSe2 nanoparticles. Also, simple and inexpensive metal precursors can be used as starting compounds because of polyols’ excellent beginning material solubilization properties [101,102]. Riyang et al. used the polyol reduction method to synthesize a highly dispersed Ru/SiO2-ZrO2 catalyst. The chelating characteristics of the polyol aid in controlling crucial elements of the particle nucleation, growth, and aggregation processes. Another important advantage of polyols is their ability to swiftly reduce metal solutions to produce metal Na-Par at higher temperatures [103]. When choosing a polyol to synthesize Na-Par, the boiling point and reduction potential must be considered.

3.4 Bridgman method

Single crystals may be grown under controlled conditions using the Bridgman method. The crystal formation of choice can be achieved using a regulated temperature gradient [104]. The gradient may be changed by adding various temperature regions to the system or by adjusting the system’s overall temperature. This process can produce single crystals in semiconductors and other electrical devices [105,106].

The polycrystalline material is heated over its melting point in an oven using the Bridgman method. A vertical and a horizontal orientation may be used to develop the crystals. Their somewhat differing cooling systems are what distinguish the two approaches. Dynamic vertical single-crystal development is shown in Figure 8. The approach has historically relied on a dynamic cooling mechanism, with hot and cold zones in the oven. In an ampoule, the melt (Figure 8) is swirled before being transferred through the cooling area of the oven. The nucleation takes place lengthwise in the cold end of the oven, and the single crystal formation begins at the end of the hot zone. To create a homogeneous crystal, cooling during crystallization should be gradual. The cooling rate is determined by the material and the product’s requirements. When the crystal is completely formed, the system is cooled down to room temperature. The domain crystalline substance is afterward returned to the melt [105]. In a static cooling setup, the melt does not move as an ampoule’s temperature varies over time. The procedure is carried out in a coil-equipped melting oven. Because the process requires constant regulation of the temperature gradient, the oven must support certain temperatures. Ovens can be of many sorts, some providing temperature control in a single or numerous zones. Most melting ovens are appropriate for controlling the temperature in one zone of static cooling systems. There must be several temperature zones in dynamic cooling systems. For instance, because tube ovens allow for numerous temperature zones, they are frequently employed in Bridgman techniques.

![Figure 8

Illustration of the Bridgman method, reproduced with the permission of Mohamed et al. [117].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_008.jpg)

Illustration of the Bridgman method, reproduced with the permission of Mohamed et al. [117].

3.5 Czochralski method (CZ)

In the CZ process, a small crystal is first inserted into a melt-in crucible, which pulls the seed upward to produce a single crystal [106]. This method of creating nanoparticles approach was established in 1916 by Jan Czochralski. The technique produces numerous single crystals, including Si and Ge [107]. Several researchers have used the CZ approach to create single crystalline SiGe. Kürten et al. used a prolonged pulling rate during the CZ development of Si-rich SiGe to create a stable liquid–solid interface. In addition, the gas flow shape was designed to ensure superior temperature stability. As a result, single-crystalline SiGe was produced with a Ge concentration of up to 0.2 [108]. Yonenaga et al. have thoroughly investigated

![Figure 9

Diagram illustrating the CZ development of a bulk SiGe crystal with Si being continuously added to the melt, reproduced with the permission of Wei et al. [120].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_009.jpg)

Diagram illustrating the CZ development of a bulk SiGe crystal with Si being continuously added to the melt, reproduced with the permission of Wei et al. [120].

3.6 Conjugated polymers

However, inorganic semiconductor materials have a few intrinsic drawbacks, such as high manufacturing costs, toxicity, poor processability, and scarcity. Furthermore, most high-performance inorganic TE materials work best at temperatures above 200°, so they cannot satisfy the growing need to capture waste heat below 150° [120]. However, there may be answers to the issues with organic semiconductors, which have been disregarded in recent decades because of their low energy conversion efficiency and potentially poor thermal stability. Conducting polymers, for example, are interesting candidates for organic semiconductors because they can convert low-end thermal energy into usable electricity [121]. This could lead to developing larger-area, more flexible, low-toxicity, and sustainable TEDs [122]. Over the past 10 years, significant efforts have been made to enhance the performance of organic thermoelectric materials. These efforts include the development of novel molecular design strategies and the creating of nanocomposites that combine nanomaterials and conducting polymers [123].

3.7 Graphene

Two-dimensional carbon lattice graphene has superior thermal and electrical characteristics [124]. Researchers’ interest in studying the thermoelectric properties of graphene skyrocketed following its discovery as the best conductor of heat and electricity. While graphene’s exceptional electrical conductivity can be attributed to its ultrahigh carrier mobility (15,000 cm2·V−1·s−1), its exceptionally high thermal conductivity (which can reach up to 2,500–5,000 W·m−1·K−1) poses a significant obstacle to its application as a thermoelectric element [125] Furthermore, generating an effective thermoelectric voltage in graphene is challenging due to its low Seebeck coefficient, commonly 10–100 µV·K‒1 [126]. Except for a few recent investigations, all these variables contribute to the extremely low reported ZT values for pristine graphene, which are approximately 10−4. For instance, a record-high ZT of 0.1 has been recorded in suspended graphene nanoribbons with widths of about 40 nm and lengths of about 0.25 microns. In contrast, a typical semiconductor has a respectable ZT of 1–2 [127].

4 Uniqueness of bismuth telluride

In recent years, TEMs have been extensively explored in terms of their characteristics, structure, and TE capabilities with various dopants. Many of these dopants give information about their features. This section examines the dopants utilized in the current and past and their influence on the TE characteristics of novel alloys.

From liquid to solid, from low temperature to high temperature, and from straightforward to complex methods, these can affect the production of nanoparticles, and the ZT was affected by these methods [132]. The HD process was used to synthesize nano-powders of

Doping with rare earth elements boosts electron concentrations and lowers electrical resistance. The electrical resistivity of

![Figure 10

The ZT of

R

0

.

2

Bi

1

.

8

Te

3

{{\bf{R}}}_{{\bf{0}}{\boldsymbol{.}}{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{1}}{\boldsymbol{.}}{\bf{8}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}

bulk samples versus reproduced with the permission of [153].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_010.jpg)

The ZT of

Lattice parameters of the prepared powders [138]

| Sample |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

4.382 | 4.387 | 4.382 | 4.386 |

|

|

30.485 | 30.495 | 30.492 | 30.496 |

Wu et al. [134] explored I-doped

When n and p kinds of carriers are present, the bipolar effect may occur [166]. The specimen’s power factor values are smaller than the un-doped sample’s. This is the result of the Sb coefficient and electrical resistivity working together. I-doping reduces the Sb coefficient while increasing electrical resistance. However, in contrast to an un-doped sample, the power factor of the

![Figure 11

The ZT of

Bi

2

Te

3

‒

x

I

x

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{I}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}

bulk samples versus temperature, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [134].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_011.jpg)

The ZT of

Lattice parameters of as-synthesized powders [2]

| Sample |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

4.381 | 4.377 | 4.373 | 4.370 |

|

|

30.481 | 30.435 | 30.406 | 30.364 |

Wu et al. [135] investigated ways to increase TE performance by manipulating the carrier concentration by doping. This work used encapsulated melting and hot pressing to create solid solutions of

Electrical transport characteristics and figure of merit of

| Samples | Hall coefficient (cm3·C−1) | Mobility (cm2·V−1·s−1) | Carrier Conc. (cm−3) | ZTmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15 | −0.085 | 92.58 | 7.37 × 1019 | 0.57@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.0025 | −0.076 | 85.67 | 9.38 × 1019 | 0.76@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.005 | −0.058 | 92.93 | 1.07 × 1020 | 0.90@149.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.01 | −0.046 | 81.84 | 1.36 × 1020 | 0.77@199.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.015 | −0.029 | 62.21 | 2.14 × 1020 | 0.71@199.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.03 | −0.017 | 42.65 | 3.63 × 1020 | 0.60@259.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:I0.045 | −0.015 | 48.60 | 4.22 × 1020 | 0.47@249.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Cu0.045 | −0.135 | 123.94 | 4.62 × 1019 | 0.58@149.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Cu0.0075 | −0.131 | 120.60 | 4.78 × 1019 | 0.64@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Cu0.01 | −0.175 | 144.48 | 3.56 × 1019 | 0.76@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Cu0.015 | −0.190 | 135.18 | 3.28 × 1019 | 0.71@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ag0.005 | −0.176 | 142.44 | 3.54 × 1019 | 0.65@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ag0.01 | −0.171 | 143.59 | 3.65 × 1019 | 0.75@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ag0.015 | −0.213 | 123.44 | 2.93 × 1019 | 0.68@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ag0.02 | −0.245 | 136.12 | 2.54 × 1019 | 0.68@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ag0.03 | −0.320 | 102.97 | 1.95 × 1019 | 0.40@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ni0.005 | −0.083 | 90.68 | 7.56 × 1019 | 0.56@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Ni0.01 | −0.279 | 118.41 | 2.23 × 1019 | 0.32@49.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Zn0.005 | −0.084 | 98.37 | 7.39 × 1019 | 0.57@99.85°C |

| Bi2Te2.85Se0.15:Zn0.01 | −0.176 | 113.25 | 3.56 × 1019 | 0.51@49.85°C |

Hot-pressed

Lattice parameters of the prepared powders [135]

| Sample |

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

4.438 | 3.042 |

|

|

4.437 | 3.048 |

|

|

4.437 | 3.040 |

|

|

4.437 | 3.040 |

|

|

4.438 | 3.035 |

|

|

4.437 | 3.039 |

When I resides at the Te-site, the electron is produced, increasing the carrier concentration and, thus, the electrical conductivity [171]. This led to an improvement in the PF value for the I-doped solution. In contrast, a hole is created when Cu and Ag atoms replace the Bi site, which lowers carrier concentration [172,173]. The Cu doping prevents the development of

![Figure 12

Figure of merit temperature dependency, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [135].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_012.jpg)

Figure of merit temperature dependency, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [135].

To improve TE ambient temperature efficiency of n-type polycrystalline,

![Figure 13

(a) The figures of merit (ZT) of

Ag

x

Bi

2

Te

2.7

Se

0.3

{{\rm{Ag}}}_{x}{{\rm{Bi}}}_{2}{{\rm{Te}}}_{2.7}{{\rm{Se}}}_{0.3}

samples versus temperature. (b) ZT versus

Ag

{\rm{Ag}}

content, reproduced with the permission of [137].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_013.jpg)

(a) The figures of merit (ZT) of

Wu et al. [138] studied how

![Figure 14

The ZT of

Bi

2

Te

3

‒

x

Se

x

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{Se}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}

samples with temperature, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [138].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_014.jpg)

The ZT of

Tentatively, this improvement in TE properties in nano-platelet composites is accredited to extensive grain boundaries in aligned nano-composites that filter low-energy electrons. In a study by Soni et al. [139], Pb-doped nano-crystalline n-type

![Figure 15

The ZT of

Tl

x

Bi

2

−

x

Te

3

‒

x

I

x

{{\bf{Tl}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}{\boldsymbol{-}}{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{I}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}

samples versus temperature, reproduced with the permission of Zhou et al. [140].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_015.jpg)

The ZT of

New groups of surface materials that have time reversal protection by time-reversal symmetry are named topological insulators [195]. Consequently, the delocalized surface state is unchanged by nonmagnetic dopants and defects. The unusual features of TIs, such as the anomalous quantum Hall effect [195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203], hold great promise for the development of quantum computing. It was demonstrated using ARPS in

The grain borders of these semiconductor matrices include embedded Pt nano-inclusions. The PF of a nano-composite thin film may be significantly increased by adding Pt nano-inclusions thanks to the energy-filtering outcome. At the same time, the thermal conductivity was decreased via scattering long-wavelength phonons. The PF reaches

![Figure 16

Ternary

Bi

‒

Ge

‒

Te

{\bf{Bi}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\bf{Ge}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\bf{Te}}

system, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [145].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_016.jpg)

Ternary

Among the alloy p-type (P2), the peak value of

![Figure 17

The ZT of

Bi

40

‒

y

Ge

x

Te

60

+

x

+

y

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{40}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\boldsymbol{y}}}{{\bf{Ge}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{60}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{\boldsymbol{x}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{\boldsymbol{y}}}

with temperature, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [145].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_017.jpg)

The ZT of

![Figure 18

The ZT of

Bi

40

‒

y

Ge

x

Te

60

+

x

+

y

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{40}}{\boldsymbol{‒}}{\boldsymbol{y}}}{{\bf{Ge}}}_{{\boldsymbol{x}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{60}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{\boldsymbol{x}}{\boldsymbol{+}}{\boldsymbol{y}}}

with temperature, reproduced with the permission of Wu et al. [145].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_018.jpg)

The ZT of

The recently established one-atom thick graphite, graphene (GR) [209], is crucial for understanding physics and real-world applications. Due to its extremely high mobility, it showed high electrical conductivity at approximately 22°C. A small amount of GR inserted into the

![Figure 19

The ZT of

Bi

2

Te

3

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}

:Gr samples, reproduced with the permission of [146].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_019.jpg)

The ZT of

Li et al. [146] examined the TE characteristics of two series of GR/

![Figure 20

Diagram of the two separate GR/

Bi

2

Te

3

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}

composites’ production process, reproduced with the permission of Li et al. [146].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_020.jpg)

Diagram of the two separate GR/

The GR/

![Figure 21

The ZT of

Bi

2

Te

3

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}

:Gr samples versus varied GR content, reproduced with the permission of Li et al. [146].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_021.jpg)

The ZT of

Li et al. [146] found that the impact of monolayer GR’s (G) presence on the conductivities of

![Figure 22

The ZT of

Bi

2

Te

3

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}

,

Bi

2

Te

3

/

C

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}{\boldsymbol{/}}{\bf{C}}

, and

Bi

2

Te

3

/

G

{{\bf{Bi}}}_{{\bf{2}}}{{\bf{Te}}}_{{\bf{3}}}{\boldsymbol{/}}{\bf{G}}

samples versus varied temperatures, reproduced with the permission of Ju and Kim [147].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_022.jpg)

The ZT of

5 Printable thermoelectric materials

Printing provides a possible means of producing TEMs at a cheaper cost and permits the creation of generators specifically designed to satisfy the needs of waste heat sources. The printing of TEMs has recently increased in terms of TE material and printing techniques, as well as performance with TEMs that are made commercially. According to Figure 23, at the proper temperatures, a

![Figure 23

The ZT of different technologies, reproduced with the permission of Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Electricity Generation Costs [221].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_023.jpg)

The ZT of different technologies, reproduced with the permission of Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Electricity Generation Costs [221].

The cost of producing TEG must be decreased, as must the price per kW·h of energy harvested if TEs are widely used. Reducing the price of producing TEMs is one technique to lower the cost of heat-to-electricity conversion. To create TEMs for modern marketable devices, spark plasma sintering, hot pressing, or a mixture of the two processes was used. These processes need expensive equipment, high temperatures, high pressures, and lengthy manufacturing periods. Contrarily, printing can be done in any environment, at high manufacturing rates, and with inexpensive tools. In recent years, printed thermoelectric has made substantial progress. Screen, inkjet, dispenser, and, more recently, 3D/pseudo-3D printing are some methods that have been researched (Figure 24). While not strictly categorized as a printing method, spin coating is frequently used in laboratories to measure the viability of ink mixtures before applying these inks in multiple printing methods. The center of a substrate that is stationary or rotating slowly has the ink formulation used on it. The substrate is programmed to turn rapidly once the ink has been put on it. Several spin velocities may be employed with different acceleration rates. When the procedure is followed correctly, consistent films are produced. This method’s drawbacks include the need for a flat substrate, and only thin films are made. Traditionally used to create commercially printed items like posters and textiles, screen printing (Figure 23b) has recently gained new applications in the manufacture of printed circuit boards (PCBs) and other electrical goods [216,217,218,219,220]. Screen-printed electrodes are frequently employed in many industrial applications, including displays, radio frequency identification, solar cells, and sensors.

![Figure 24

(a) Spin coating, (b) screen, (c) inkjet, (d) dispenser printing, and (e) fuse deposition modeling, reproduced with the permission of Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Electricity Generation Costs [221].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2024-0023/asset/graphic/j_rams-2024-0023_fig_024.jpg)

(a) Spin coating, (b) screen, (c) inkjet, (d) dispenser printing, and (e) fuse deposition modeling, reproduced with the permission of Department for Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, Electricity Generation Costs [221].

In traditional screen printing, a patterned stencil is affixed to the mesh, and a woven or stainless-steel mesh screen mask is used. Photolithography is used to create this stencil using a photo emulsion layer. An electrode design is deposited on the substrate through a stencil aperture, and conductive ink dispersed on the screen mask is squeezed into the woven or stainless-steel mesh. Ink is transferred to a substrate during the screen printing process, except for regions of the web that are impervious because of a hindering stencil. To fill the open holes on the screen with ink, a squeegee or blade is passed over it. After that, an opposite stroke lets the screen briefly trace the substrate along the contact line. As a result, the screen retracts when the blade has passed, causing the ink to moisten the substrate and be drawn out through mesh apertures. Various widths can be printed from a few microns to several hundred microns. Any level solid substrate can be utilized, and typical examples include polyimide for thermoelectric applications and aluminum, glass, and other common materials. Another constraint is the drying method, which might cause contraction and surface irregularity, which may result in errors or imperfections in the ultimate product. If complicated pieces are required, the restriction on feature size may cause problems in the top product. Even though the inks can have various viscosities, more excellent viscosity inks are more commonly employed than those used in other printing procedures [222,223]. Due to oxidation of the surface of films and the fact that the TE particles are not in liquid form, films made using this technique often exhibit reduced electrical conductivity, making electrical paths more challenging to cross [224,225]. The inkjet printing process entails the construction of an image on a substrate drop by drop while being electronically operated. One of the most promising techniques for the simple, low-cost production of high-resolution functional materials is inkjet printing technology. The liquid droplet transfer of ink material to a substrate is crucial to inkjet printing. As a result, there is no need for mechanical contact between the print head and the substrate [226]. The most common kind is drop-on-demand (DOD), with continuous inkjet printing as an alternative.

A voltage-activated piezoelectric diaphragm pushes ink into a chamber in a DOD system. When the diaphragm contracts due to a voltage change, there is a higher pressure inside the diaphragm than in the printing chamber. This pressure difference forces ink into the chamber. To print more ink on the subsequent initiation of the piezoelectric diaphragm, the capacity of the diaphragm diminishes when the voltage is reversed to let in air. There is minimal ink waste since ink droplets are only created when necessary. However, if the ink particle size is close to the nozzle diameter in inkjet printing, the printer head is prone to blockage and disfigurement [227]. If a bigger spout diameter is used, the image quality might be decreased [228]. Thus, research into these variables is essential to the development of functional material inkjet printing. Some applications require creating narrow, smooth structures with various geometries, such as integrated circuits and optical waveguides. Increasing printing resolution is a complex undertaking that necessitates an additional technological advancement related to the resource-intensive substrate pretreatment.

5.1 Printed TEDs

The n- and p-type components are linked in series in alternating patterns in the fundamental construction of TEDs such that the voltage created by each component sums up [229]. The output demand and the application determine how many elements are needed. Kim made a flexible TE generator on glass textiles using the screen-printing method. They bent the device to study its adaptability and showed that it maintained a constant efficiency even after 120 iterations [230]. With eight n-type

The item has 254 p and 253 n-type legs with an area of approximately 44.2854 mm2 for each leg, arranged in a checkerboard design with a 39 cross-13 matrix. In their research, they employed a folding technique that allowed for a minimal spacing among the TE legs, or effectively the substrate thickness of 0.06 m, to act as an insulating barrier between the TE components. They attained a high thermocouple density of around 190 cm2, which led to a high open-circuit voltage.

To create the TEG, they combined a hybrid

Madan et al. [240] created an n-type

Summary of the power outputs of printed TEG based on Te

| Materials | Printing method | Substrate | Thickness (mm) | Power (µW) | Power density (mW·cm−2) | Cure T (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sb2Te3/Bi1.8Te3.2 | Screen | Kapton | 0.067 | 0.048 | 180 | 523 |

| Sb2Te3/Bi2Te3 | Screen | Glass Fabric | 0.5 | — | — | 803 |

| Sb2Te3/BiTe (epoxy) | Screen | Polyimide | 0.078 | 0.44 | 180 | 523 |

| Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3/Bi2Te2.75Se0.25 with epoxy | Dispenser | Free standing | 4.4 | 0.126 | — | — |

| BiSbTe/BiSeTe | Screen | a-Si quartz/SiO2 | 0.65 | 76,480 | — | — |

| Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3/Bi with epoxy | Dispenser | Glass | — | 130 | 720 | 523 |

| Sb2Te3/Bi2Te3 (epoxy) | Dispenser | Polyimide | 0.12 | 0.85 | — | 473 |

| Sb2Te3/Bi2Te3 with epoxy | Dispenser | Polyimide/glass | 0.2 | 10.5 | — | 523 |

| Bi2Te3 (PVA) | Shadow Mask | PET | 0.265 | — | 120 | 353 |

| Bi2Te3 with epoxy | Dispenser | Polyimide | 0.1–0.12 | 25 | 720 | 623 |

| BiTeSe with aterpineol and Disperbyk – 110 | Screen | Polyimide | 0.1 | 0.004 | 45 | 703 |

| Sb1.5Bi0.5Te3/Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 | Inkjet | Glass/Polyimide | 150 layers | 341 | 673 | 673 |

| Bi0.55Sb1.45Te3/Bi2Te2.7 with Sb2Te4 2 | 3D | N/A | 0.35 | 2.8 | 723 | 723 |

| Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3/Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 with Sb2Te3 | 3D | N/A | 1.5–2.0 | 1,620 | 723 | 723 |

| Se doped Bi2Te3 with epoxy | Dispenser | Polyimide | 0.2 | 1.6 | 720 | 523 |

| Pb0.98Na0.02Te/Pb0.98Sb0.02Te | 3D | N/A | 2 | 216,300 | 3,150 | 373–1,023 |

| Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3/Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 | Laser | Bi0.4Sb1.6Te3 | 1.6 | 1,450,000 | 1,440 | 673 |

| Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3/Bi2Te3 | Inkjet | Polyimide | 0.0015 | 0.127 | 723 | 723 |

| Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3/Bi with epoxy | Dispenser | Glass | — | 130 | 720 | 523 |

6 Summary and perspectives

Despite significant progress in printed TEMs over the past 10 years, the effectiveness of printed TEDs still falls short of the capabilities of the materials they are made from. High electrical and thermal contact resistances primarily cause low conversion efficiency at the device level. In addition, most TE inks fall short in printability and mechanical properties, even though a few reports demonstrate good results [242,243]. One of the main problems is simultaneously improving the printed materials’ mechanical and TE characteristics. Another obstacle to overcome is to make the preparation process simpler. Although its morphology is poor, solid-state processing at high temperatures enables a well-controlled chemical composition [244]. In addition, higher temperatures cause the polymer substrates to break down. To increase the conversion efficiency of printed TED’s, further in-depth research on device designs, electrical contacts, and thermal contacts is needed. New types of high-efficiency printed TEMs may result from further study. Using fresh, efficient manufacturing techniques might enhance the performance and robustness of the TEDs.

In the past few years, it has been discovered that the photonic curing [245] procedure is an exceptional sintering method that enables excellent efficiency and mechanical flexibility. The procedure minimizes the possibility of oxidation because it only needs a few multiples of 10‒3 s printed TEM’s sintering. The shape of the TEDs also affects the conversion efficiency since it regulates the devices’ electrical and thermal impedance [246]. Another crucial area of research is the impact of shape on device efficiency. One of the potential production techniques for ink creation is the solution-based wet chemistry approach, which enhances the ink’s surface chemistry [247]. Significant findings from TE inks [248,249] and printed systems [250,251,252,253,254] made with various concentrations and recipes have been published recently. However, further study on the subject is required to overcome the challenges. While

To make the TE technology feasible and affordable, a shift in thinking from traditional bulk to printable TEs has been widely noted in recent years. In addition, bulk TEs do not provide shape conformity, which is necessary for numerous applications on irregular surfaces. Shape-conformable TEDs might be produced at a reasonable cost thanks to the printed TEs. To begin with, organic polymers have been the focus of efforts to transform them into powerful printed TEMs. Their low TE efficiency, however, restricts their use despite their good printing ability. Inorganic-based printed TEs have recently made advancements, as detailed in this article. Inorganic materials that can be printed provide a way around these restrictions. We have outlined the basic principles of TEs, the composition of TE ink, and current developments in inorganic and hybrid printed TE materials. Inorganic TEM materials have been the focus of most studies on printed TEs. However, other chalcogenides have also demonstrated promising abilities. However, improving TE efficiency by hybridizing organic and inorganic materials could be fruitful. There are several reasons for the competitiveness of TEDs compared with other renewable energy resources, including efficiency in waste heat recovery, low maintenance and long lifespan, scalability and flexibility, reliability and durability, low environment impact, diversified energy sources, technological innovation, and cost reduction. These findings might open the door for the production of low-cost TEDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support by the Project of State Key Laboratory of Environment-Friendly Energy Materials (227/35100011).

-

Funding information: This work was partly financially supported by the Project of State Key Laboratory of Environment-Friendly Energy Materials (227/35100011).

-

Author contributions: Writing – original draft preparation; conceptualization, funding acquisition by Syed Irfan, review – Zhiyuan Yang and supervised and edited by Sadaf Bashir Khan. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Seebeck, T. J. Magnetische polarisation der metalle und erze durch temperatur differenz. Annalen der Physik, Vol. 82, No. 2, 1822, pp. 133–160.10.1002/andp.18260820202Search in Google Scholar

[2] Peltier, J. C. A. Nouvelles Expériemences sur la Caloricite descourants électriques. Annales de Chimie et de Physique, Vol. 56, 1834, pp. 371–386.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Thomson, W. On a mechanical theory of thermoelectric currents. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Vol. 3, 1851, pp. 91–98.10.1017/S0370164600027310Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wei, Q., S. Qianfa, L. YiZhen, C. Rui, G. Xiuying, Z. Tixian, et al. Ultrathin elementary te nanocrystalline films prepared by pure physical method for NO2 detection. Journal of Electronic Materials, Vol. 52, 2022, pp. 1900–1907.10.1007/s11664-022-10154-3Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chen, L., R. Liu, and X. Shi. Thermoelectric materials and devices, Shanghai Institute of Ceramics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Indraneel, N. and N. Milankumar. Modeling and validation of the impact of electric current and ambient temperature on the thermoelectric performance of lithium-ion batteries. Energy Technology, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2021, id. 2100774.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Wanli, Y., L. Jinxi, and H. Yuantai. Mechanical tuning methodology on the barrier configuration near a piezoelectric PN interface and the regulation mechanism on I–V characteristics of the junction. Nano Energy, Vol. 81, 2020, id. 105581.10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105581Search in Google Scholar

[8] Costa, S. S. and L. C. Sampaio. Recent progress in the spin Seebeck and spin Peltier effects in insulating magnets. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Vol. 547, 2021, id. 168773.10.1016/j.jmmm.2021.168773Search in Google Scholar

[9] Yamashita O. Effect of linear temperature dependence of thermoelectric properties on energy conversion efficiency. Energy Convers Manag. Vol. 49, No. 11, 2008, pp. 3163–3169.10.1016/j.enconman.2008.05.019Search in Google Scholar

[10] Sandoz-Rosado E, Stevens RJ. Experimental characterization of thermoelectric modules and comparison with theoretical models for power generation. J Electron Mater. Vol. 38, 2009, pp. 1239–1244.10.1007/s11664-009-0744-0Search in Google Scholar

[11] Kim HS, Liu W, Ren Z. Efficiency and output power of thermoelectric module by taking into account corrected Joule and Thomson heat. J Appl Phys. Vol. 118, 2015, id. 115103.10.1063/1.4930869Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kosuke, M., I. Yuki, and O. Koji. Achieving Carnot efficiency in a finite-power Brownian Carnot cycle with arbitrary temperature difference. Physical Review E, Vol. 105, 2022, id. 034102.10.1103/PhysRevE.105.034102Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Ruihua, C., X. Weicong, D. Shuai, Z. Ruikai, C. Q. Siyoung, and Z. Li. A contemporary description of the carnot cycle featured by chemical work from equilibrium: The electrochemical carnot cycle. Energy, Vol. 280, 2023, id. 128168.10.1016/j.energy.2023.128168Search in Google Scholar

[14] Tianye, W., L. Hu, F. Yangming, Z. Xiaoxiao, H. Long, and S. Aimin. A graphene-nanoribbon-based thermoelectric generator. Carbon, Vol. 210, 2023, id. 118053.10.1016/j.carbon.2023.118053Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ruo, J. W., H. P. Yu, and L. C. Wen. A dimensionless study on thermal control of positive temperature coefficient (PTC) materials. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, Vol. 120, 2020, id. 104987.10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104987Search in Google Scholar

[16] Yang, F., X. Zhang, B. Yan, J. Lin, L. Liu, L. Tang, et al. Study of Seebeck coefficient in organic materials under nonlinear temperature distributions. Modern Physics Letters B, Vol. 37, No. 29, 2023, id. 2350102.10.1142/S0217984923501026Search in Google Scholar

[17] Dongxing, S., C. Cheng, A. Meng, D. Yanzheng, M. Weigang, W. Ke, et al. Ionic Seebeck coefficient and figure of merit in ionic thermoelectric materials. Cell Reports Physical Science, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2022, id. 101018.10.1016/j.xcrp.2022.101018Search in Google Scholar

[18] Sonya, H., F. Eric, C. Benoit, P. Christophe, Z. Marcin, W. Ś. Dorota, et al. Composites between perovskite and layered Co-based oxides for modification of the thermoelectric efficiency. Materials, Vol. 14, 2021, id. 7019.10.3390/ma14227019Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Edoardo, N., F. Walter, B. Paolo, and G. Alessandro. Leaky-wave analysis of TM-, TE-, and hybrid-polarized aperture-fed bessel-beam launchers for wireless-power-transfer links. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, Vol. 71, No. 2, 2022, pp. 1424–1436.10.1109/TAP.2022.3231086Search in Google Scholar

[20] Weihua, W., W. Quanlin, S. Lin, J. Peng, and B. Xinhe. High-performance Sb2Si2Te6 thermoelectric device. Materials Today Energy, Vol. 37, 2023, id. 101370.10.1016/j.mtener.2023.101370Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ibrahim, B. H., B. Zahia, and Z. Katir. Metal-based folded-thermopile for 2.5D micro-thermoelectric generators. Sensors and Actuators, A: Physical, Vol. 349, 2022, id. 114090.10.1016/j.sna.2022.114090Search in Google Scholar

[22] Feng, Z., J. Chen, X. Deqiao, L. Bin, Q. Mingbo, Y. Xinyu, et al. Research on laser-assisted selective metallization of a 3D printed ceramic surface. RSC Advances, Vol. 10, 2020, pp. 44015–44024.10.1039/D0RA08499ASearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Panisara, S. and S. Phairote. Improvements in the properties of low-Ag SAC105 solder alloys with the addition of tellurium. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, Vol. 34, 2023, id. 1327.10.1007/s10854-023-10704-3Search in Google Scholar

[24] Zhang, Q. H., X. Y. Huang, S. Q. Bai, X. Shi, C. Uher, and L. D. Chen. Thermoelectric devices for power generation: recent progress and future challenges. Advanced Engineering Materials, Vol. 18, 2016, pp. 194–213.10.1002/adem.201500333Search in Google Scholar

[25] Zhao, D., X. Li, L. He, W. Jiang, and L. Chen. Interfacial evolution behavior and reliability evaluation of CoSb3/Ti/Mo−Cu thermoelectric joints during accelerated thermal aging. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, Vol. 477, 2009, pp. 425–431.10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.10.037Search in Google Scholar

[26] Li, F., X. Huang, W. Jiang, and L. Chen. Interface microstructure and performance of Sb contacts in bismuth telluride-based thermoelectric elements. Journal of Electronic Materials, Vol. 42, 2013, pp. 1219–1224.10.1007/s11664-013-2566-3Search in Google Scholar

[27] Jianqiang, Z., W. Ping, Z. Huiqiang, L. Longzhou, Z. Wanting, N. Xiaolei, et al. Enhanced contact performance and thermal tolerance of Ni/Bi2Te3 joints for Bi2Te3-based thermoelectric devices. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, Vol. 15, No. 18, 2023, pp. 22705–22713.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dariusz, B., C. Artur, and D. Grzegorz. Influence of the sintering method on the properties of a multiferroic ceramic composite based on PZT-type ferroelectric material and Ni-Zn ferrite. Materials, Vol. 15, No. 23, 2022, id. 8461.10.3390/ma15238461Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Temel, V., G. Onur, B. A. Serhatcan, and C. A. Hüseyin. Novel advanced copper-silver materials produced from recycled dendritic copper powders using electroless coating and hot pressing. Powder Metallurgy, Vol. 65, 2022, pp. 390–402.10.1080/00325899.2022.2026031Search in Google Scholar

[30] Smita, H., S. Gupta, R. Vasudevan, and K. Sachdev. Synthesis and characterization of doped Mg2Si0.4Sn0.6 thermoelectric material made in exclusion of glove box. Solid State Communications, Vol. 353, 2022, id. 114847.10.1016/j.ssc.2022.114847Search in Google Scholar

[31] Shengzhi, D., W. Yifan, W. Xiaowen, W. Meihua, W. Lianyi, F. Minghao, et al. Printable graphite-based thermoelectric foam for flexible thermoelectric devices. Applied Physics Letters, Vol. 123, 2023, id. 063904.10.1063/5.0159347Search in Google Scholar

[32] Jeong, S. Y., C. Seongyun, and H. I. Sang. Advances in carbon-based thermoelectric materials for high-performance. flexible thermoelectric devices. Carbon Energy, Vol. 3, No. 5, 2021, pp. 667–708.10.1002/cey2.121Search in Google Scholar

[33] Jiaqing, Z., C. Jiayi, C. Zhewei, L. Ya, Z. Jiye, S. Tao, et al. Printed flexible thermoelectric materials and devices. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, Vol. 9, 2021, pp. 19439–19464.10.1039/D1TA03647ESearch in Google Scholar

[34] Yubing, X., T. Kechen, W. Jiang, H. Kai, X. Yani, L. Jianan, et al. High-performance wearable Bi2Te3-based thermoelectric generator. Applied Sciences, Vol. 13, No. 10, 2023, id. 5971.10.3390/app13105971Search in Google Scholar

[35] Poonam, R. and P. P. Tripathy. Experimental investigation on heat transfer performance of solar collector with baffles and semicircular loops fins under varied air mass flow rates. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, Vol. 178, 2022, id. 107597.10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2022.107597Search in Google Scholar

[36] Fuzhang, W., N. K. Rangaswamy, C. P. Ballajja, K. Umair, Z. Aurang, H. A. A. Abdel, et al. Aspects of uniform horizontal magnetic field and nanoparticle aggregation in the flow of nanofluid with melting heat transfer. Nanomaterials, Vol. 12, No. 6, 2022, id. 1000.10.3390/nano12061000Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Nidhal, B. K., B. Nirmalendu, T. Hussein, I. M. Hayder, M. M. Jasim, K. I. Raed, et al. Geometry modification of a vertical shell-and-tube latent heat thermal energy storage system using a framed structure with different undulated shapes for the phase change material container during the melting process. Journal of Energy Storage, Vol. 72, 2023, id. 108365.10.1016/j.est.2023.108365Search in Google Scholar

[38] Jiang, J. M., Y. L. Qing, F. L. Peng, Z. Ping, S. Biplab, O. Tao, et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity and anisotropic thermoelectric performance in layered materials LaMOCh (M = Cu, Ag; Ch = S, Se). Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, Vol. 24, 2022, pp. 21261–21269.10.1039/D2CP02067JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Deepthi, J. K. Theoretical modeling of Perovskite–Kesterite Tandem solar cells for optimal photovoltaic performance. Energy Technology, Vol. 10, No. 12, 2022, id. 2200635.10.1002/ente.202200635Search in Google Scholar

[40] Weinberg, F. J., D. M. Rowe, and G. Min. Novel high performance small-scale thermoelectric power generation employing regenerative combustion systems. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, Vol. 35, 2002, pp. L61–L63.10.1088/0022-3727/35/13/102Search in Google Scholar

[41] Juan, W., Y. Zhong, M. Zhijun, D. Hongbo, Z. Jiachen, T. Dong, et al. Effect of the addition of cerium on the microstructure evolution and thermal expansion properties of cast Al-Cu-Fe alloy. Materials Research Express, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2021, id. 036503.10.1088/2053-1591/abe8f4Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ya, G., L. Yousheng, H. Qing, W. Wenhao, C. Jiechao, and M. H. Si. Geometric optimization of segmented thermoelectric generators for waste heat recovery systems using genetic algorithm. Energy, Vol. 233, 2021, id. 121220.10.1016/j.energy.2021.121220Search in Google Scholar

[43] Limei, S., W. Yupeng, T. Xiao, X. Shenming, and S. Yongjun. Inverse optimization investigation for thermoelectric material from device level. Energy Conversion and Management, Vol. 228, 2021, id. 113669.10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113669Search in Google Scholar

[44] Manuela, G., C. Flaviana, and M. Francesco. Numerical and experimental investigations of a novel 3D bucklicrystal auxetic structure produced by metal additive manufacturing. Thin-Walled Structures, Vol. 180, 2022, id. 109850.10.1016/j.tws.2022.109850Search in Google Scholar

[45] Minghui, G., L. Zhenhua, W. Yeting, Z. Yulong, Z. Yu, W. Shixue, et al. Experimental study on thermoelectric power generation based on cryogenic liquid cold energy. Energy, Vol. 220, 2021, id. 119746.10.1016/j.energy.2020.119746Search in Google Scholar

[46] Fan, C., H. Kun, G. Meng, Z. Yan, X. Wei, H. Juntao, et al. Magnetocaloric properties of melt-extracted Gd-Co-Al amorphous/crystalline composite fiber. Metals, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2022, id. 1367.10.3390/met12081367Search in Google Scholar

[47] Crane, D. T. and L. E. Bell. Progress towards maximizing the performance of a thermoelectric power generator. In 2006 25th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, IEEE, 2006, pp. 11–16.10.1109/ICT.2006.331259Search in Google Scholar

[48] Chen, L., R. Liu, and X. Shi. Thermoelectric materials and devices, 1st ed., Science Press, Beijing, 2018, p. 195.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Joohyun, L., H. K. Se, A. A. Raquel, K. Olga, P. C. Pyuck, T. S. Leigh, et al. Atomic scale mapping of impurities in partially reduced hollow TiO2 nanowires. Angewandte Chemie, Vol. 59, No. 14, 2020, pp. 5651–5655.10.1002/anie.201915709Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Jun, Y. C., H. C. Joon, C. Jacob, M. Y. Jong, and D. K. Il. Bias-free graphene solid cell to realize the real-time observation on dynamical changes of electrodes. Advanced Materials Interfaces, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2022, id. 2201849.10.1002/admi.202201849Search in Google Scholar

[51] Wei, Z., Y. A. O. Shanshan, and W. Feng. In situ, operando lithium K-edge energy-loss spectroscopy of battery materials. Microscopy and Microanalysis, Vol. 26, No. S2, 2020, pp. 2538–2540.10.1017/S1431927620021960Search in Google Scholar

[52] Zhang, Q., J. Liao, Y. Tang, M. Gu, C. Ming, P. Qiu, et al. Realizing a thermoelectric conversion efficiency of 12% in bismuth telluride/skutterudite segmented modules through full-parameter optimization and energy-loss minimized integration. Energy & Environmental Science, Vol. 10, 2017, pp. 956–963.10.1039/C7EE00447HSearch in Google Scholar

[53] Shi, Y., N. Ni, Q. Ding, and X. Zhao. Tailoring high-temperature stability and electrical conductivity of high entropy lanthanum manganite for solid oxide fuel cell cathodes. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, Vol. 10, 2022, pp. 2256–2270.10.1039/D1TA07275GSearch in Google Scholar

[54] Cushing, B. L., V. L. Kolesnichenko, and C. J. O'connor. Recent advances in the liquid-phase syntheses of inorganic nanoparticles. Chemical Reviews, Vol. 104, No. 9, 2004, pp. 3893–3946.10.1021/cr030027bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Wu, M., G. Lin, D. Chen, G. Wang, D. He, S. Feng, et al. Sol-hydrothermal synthesis and hydrothermally structural evolution of nanocrystal titanium dioxide. Chemistry of Materials, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2002, pp. 1974–1980.10.1021/cm0102739Search in Google Scholar

[56] Hakuta, Y., H. Ura, H. Hayashi, and K. Arai. Continuous production of BaTiO3 nanoparticles by hydrothermal synthesis. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2005, pp. 840–846.10.1021/ie049424iSearch in Google Scholar

[57] Rabenau, A. The role of hydrothermal synthesis in preparative chemistry. Angewandte Chemie, International Edition in English, Vol. 24, No. 12, 1985, pp. 1026–1040.10.1002/anie.198510261Search in Google Scholar

[58] Shuangming, S., X. Chaoyi, L. Heping, X. Liping, L. Sen, and L. Shengbin. In situ electrical conductivity measurements of porous water-containing rock materials under high temperature and high pressure conditions in an autoclave. Review of Scientific Instruments, Vol. 92, No. 9, 2021, id. 095104.10.1063/5.0054892Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Shi, W., S. Song, and H. Zhang. Hydrothermal synthetic strategies of inorganic semiconducting nanostructures. Chemical Society Reviews, Vol. 42, No. 13, 2013, pp. 5714–5743.10.1039/c3cs60012bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Cundy, C. S. and P. A. Cox. The hydrothermal synthesis of zeolites: precursors, intermediates and reaction mechanism. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, Vol. 82, No. 1, 2005, pp. 1–78.10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.02.016Search in Google Scholar

[61] Jiao, X., D. Chen, and L. Xiao. Efefct of organic additives in hydrothermal zirconia nanocrystallites. Journal of Crystal Growth, Vol. 258, 2023, id. 158.10.1016/S0022-0248(03)01473-8Search in Google Scholar

[62] Sun, C., H. Li, H. Zhang, Z. Wang, and L. Chen. Controlled synthesis of CeO2 nanorods by a solvothermal method. Nanotechnology, Vol. 16, 2005, id. 1454.10.1088/0957-4484/16/9/006Search in Google Scholar

[63] Wang, G., Z. Wang, Y. Zhang, G. Fei, and L. Zhang. Controlled synthesis and characterization of large-scale, uniform Dy(OH)3 and Dy2O3 single-crystal nanorods by a hydrothermal method. Nanotechnology, Vol. 15, 2004, id. 1307.10.1088/0957-4484/15/9/033Search in Google Scholar

[64] Sorescu, M., L. Diamandescu, M. D. Tarabasanu, and V. S. Teodorescu. Nanocrystalline rhombohedral In2O3 synthesized by hydrothermal and postannealing pathways. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 39, 2004, id. 675.10.1023/B:JMSC.0000011529.01603.fcSearch in Google Scholar

[65] Jing, Z. and S. Wu. Synthesis and characterization of monodisperse hematite nanoparticles modified by surfactant via hydrothermal approach. Materials Letters, Vol. 58, 2004, id. 3637.10.1016/j.matlet.2004.07.010Search in Google Scholar

[66] Zheng, Y., Y. Cheng, Y. Wang, and F. Bao. Synthesis and shape evolution of alpha-Fe2O3 nanophase through two-step oriented aggregation in solvothermal system. Journal of Crystal Growth, Vol. 284, 2005, id. 221.10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2005.06.051Search in Google Scholar

[67] Li, G. S., J. R. L. Smith, H. Inomata, and K. Arai. Preparation and magnetization of hematite nanocrystals with amorphous iron oxide layers by hydrothermal conditions. Materials Research Bulletin, Vol. 37, 2002, id. 949.10.1016/S0025-5408(02)00695-5Search in Google Scholar

[68] Suber, L., D. Fiorani, P. Imperatory, S. Foglia, A. Montone, and R. Zysler. Effects of thermal treatments on thermal on structural and magnetic properties of acicular alpha-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Nanostructured Materials, Vol. 11, 1999, id. 797.10.1016/S0965-9773(99)00369-4Search in Google Scholar

[69] Cote, L. J., A. S. Teja, A. P. Wilkinson, and Z. J. Zhang. Continuous hydrothermal synthesis of CoFe2O3 nanoparticles. Fluid Phase Equilibria, Vol. 210, 2003, id. 307.10.1016/S0378-3812(03)00168-7Search in Google Scholar

[70] Cote, L. J., A. S. Teja, A. P. Wilkinson, and Z. J. Zhang. Continuous hydrothermal synthesis and crystallization of magnetic oxide nanoparticles. Journal of Materials Research, Vol. 17, 2002, id. 2410.10.1557/JMR.2002.0352Search in Google Scholar

[71] Wan, J., X. Chen, Z. Wang, X. Yang, and Y. T. Qian. A soft-template-assisted hydrothermal approach to single crystal Fe2O4 nanorods. Journal of Crystal Growth, Vol. 276, 2005, id. 571.10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.11.423Search in Google Scholar

[72] Kominami, H., M. Miyakawa, S. Murakami, T. Yasuda, M. Kohno, S. Onoue, et al. Solvothermal synthesis of tantalum (v) oxide nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activities in aqueous suspension system. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, Vol. 3, 2001, pp. 2697–2703.10.1039/b101313kSearch in Google Scholar

[73] Adschiri, T., K. Kanaszawa, and K. Arai. Rapid and continuous hydrothermal crystallization of metal oxide particles in supercritical water. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 75, 1992, id. 1019.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1992.tb04179.xSearch in Google Scholar

[74] Adschiri, T., K. Kanaszawa, and K. Arai. Rapid and continuous hydrothermal synthesis of boehmite particles in subcritical and supercritical water. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 75, 1992, id. 2615.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1992.tb05625.xSearch in Google Scholar

[75] Hakuta, Y., T. Adschiri, T. Suzuki, T. Chida, K. Seino, and K. Arai. Flow method for rapidly producing barium hexaferrite particles in supercritical water. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 81, 1998, id. 2461.10.1111/j.1151-2916.1998.tb02643.xSearch in Google Scholar

[76] Adschiri, T., Y. Hakuta, K. Sue, and K. Arai. Hydrothermal synthesis of metal oxide nanoparticles at supercritical conditions. Journal of Nanoparticle Research, Vol. 3, 2001, id. 227.10.1023/A:1017541705569Search in Google Scholar

[77] Hakuta, Y., S. Onai, H. Terayama, T. Adschiri, and K. Aria. Production of Ultra-fine ceria particles by hydrothermal synthesis under supercritical conditions. Journal of Materials Science Letters, Vol. 17, 1998, id. 1211.10.1023/A:1006597828280Search in Google Scholar

[78] Byrappa, K., R. K. M. Lokanatha, and M. Yoshimura. Hydrothermal preparation of TiO2 and Photocatalytic degradation of hexacholocyclohexane and dicholorodiphenyltricholorometane. Environmental Technology, Vol. 21, 2000, id. 1085.10.1080/09593330.2000.9618994Search in Google Scholar

[79] Liu, Y., Y. Du, Q. Meng, J. Xu, and S. Z. Shen. Effects of preparation methods on the thermoelectric performance of SWCNT/Bi2Te3 bulk composites. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 11, 2020, id. 2636.10.3390/ma13112636Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[80] Niederberger, M. and N. Pinna. Metal oxide nanoparticles in organic solvents: Synthesis, formation, assembly and application (Engineering Materials and Processes), Springer, Berlin, Germnay, 2009.10.1007/978-1-84882-671-7Search in Google Scholar

[81] Feinle, A., M. S. Elsaesser, and N. Huesing. Sol–gel synthesis of monolithic materials with hierarchical porosity. Chemical Society Reviews, Vol. 45, No. 12, 2016, pp. 3377–3399.10.1039/C5CS00710KSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[82] Liao, Y., Y. Xu, and Y. Chan. Semiconductor nanocrystals in sol-gel derived matrices. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, Vol. 15, No. 33, 2013, pp. 13694–13704.10.1039/c3cp51351cSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Owens, G. J., R. K. Singh, F. Foroutan, M. Alqaysi, C. M. Han, C. Mahapatra, et al. Sol-gel based materials for biomedical applications. Progress in Materials Science, Vol. 77, 2016, pp. 1–79.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2015.12.001Search in Google Scholar

[84] Haruta, M. Nanoparticulate gold catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation. Journal of New Materials for Electrochemical Systems, Vol. 7, 2004, pp. 163–172.10.1002/chin.200448226Search in Google Scholar

[85] Tian, N., Z. Y. Zhou, S. G. Sun, Y. Ding, and Z. L. Wang. Synthesis of tetrahexahedral platinum nanocrystals with high-index facets and high electro-oxidation activity. Science, Vol. 316, No. 5825, 2007, pp. 732–735.10.1126/science.1140484Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[86] Xu, R., D. Wang, J. Zhang, and Y. Li. Shape-dependent catalytic activity of silver nanoparticles for the oxidation of styrene. Chemistry – An Asian Journal, Vol. 1, No. 6, 2006, pp. 888–893.10.1002/asia.200600260Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Rahman, I. A. and V. Padavettan. Synthesis of silica nanoparticles by sol-gel: size-dependent properties, surface modification, and applications in silica-polymer nanocomposites – a review. Journal of Nanomaterials, Vol. 15, 2012, id. 2012.10.1155/2012/132424Search in Google Scholar