Abstract

The use of titanium gypsum instead of gypsum as a raw material for the preparation of gypsum-slag cementitious materials (GSCM) can reduce the cost and improve the utilization of solid waste. However, titanium gypsum contains impurities such as Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2, which make its effect on the performance of GSCM uncertain. To investigate this issue, GSCM doped with different ratios of Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 were prepared in this study, the setting time and the strength of GSCM at 3, 7, and 28 days were tested. The effects of different oxides on the performance of GSCM were also investigated by scanning electron microscopy, energy spectrum analysis, X-ray diffraction analysis, and thermogravimetric analysis. The experimental results showed that Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 all had a certain procoagulant effect on GSCM and a slight effect on the strength. Through micro-analysis, it was found that the main hydration products of GSCM were AFt phase and calcium–alumina–silicate–hydrate (C–(A)–S–H) gels. Fe-rich C–(A)–S–H gels were observed with the addition of Fe2O3, and Mg(OH)2 and M–S–H gels were observed with the addition of MgO. The addition of TiO2 did not result in new hydration products from GSCM.

1 Introduction

Titanium gypsum is an industrial by-product produced during titanium dioxide production by the sulfuric acid process [1]. Each production of 1t of titanium dioxide produces 6t of titanium gypsum; according to statistics, China produces about 30 million tons annually [2]. Experimental research on titanium gypsum in recent years has focused on cement retarders [3,4], preparation of composite cementitious materials [5,6,7], production of gypsum building materials [8,9], soil conditioners, and land backfill materials [10,11,12]. A large amount of titanium gypsum open pile processing will occupy many lands and bring severe environmental pollution, so the development and utilization of titanium gypsum have become urgent [4]. Super sulfate cement is mainly known as gypsum slag cement in China. Compared with ordinary Portland cement, gypsum slag cement has the advantages of low heat of hydration, good resistance to alkali-aggregate reaction, good resistance to sulfate and chloride erosion, and high late strength [13,14,15]. Gypsum is the main component of gypsum slag cement, the content of which accounts for more than 20%. Suppose the raw titanium gypsum slag can be directly used as the raw material of super sulfate cement, in that case, it will increase the effective utilization of titanium gypsum slag and reduce the environmental pollution and CO2 emission of titanium dioxide processing industry.

Some scholars studied the preparation of cementitious materials using industrial by-product gypsum instead of gypsum, but most of them focused on the modification of phosphogypsum. Some researchers investigated the effect of phosphogypsum on the hydration process and microstructure of alkali-activated slag slurry with reference to natural gypsum. The results showed that phosphogypsum reduced the early strength and increased the late strength of the specimens. The addition of phosphogypsum refined the pore structure and produced lower porosity than natural gypsum, generated calcium–alumina–silicate–hydrate (C–(A)–S–H) gels with higher polymerization degree [16]. Chinese researchers found that the engineering properties of supersulfated phosphogypsum slag cement were comparable to those of silicate cement and had good water stability, which comprised 40% phosphogypsum, 40–50% granulated blast furnace slag, and a small amount of alkali activator [17]. 10–50% of metakaolin reduced the setting time of sulfur-phosphorus gypsum cementitious materials by 13–38%. Metakaolin dosage of up to 20% effectively promoted the strength development of cementitious materials, where slag and metakaolin synergistically promoted the formation of ettringite and C–(A)–S–H gels [18]. However, some studies showed that the soluble impurities in phosphogypsum and the relatively slow hydration rate of slag could affect the performance of persulfate cement. This prolonged the setting time and reduced the compressive strength of the specimens [19].

Related studies showed that the addition of nano-Fe2O3 can improve the flowability of cementitious materials, refine the material pore structure, and promote cement hydration. Thus, the mechanical properties and durability of the low water-cement ratio cementitious material could be improved to a certain extent [20]. Researchers blended Fe2O3 into 15% fly ash cement mortar to analyze the strength change of cementitious materials. The results showed that the greatest increase in mortar compressive strength was achieved at 1.25% addition of oxide powder [21]. Similarly, researchers also studied the effect of Fe2O3 on the properties of 30% fly ash cement mortar. They found that the incorporation of Fe2O3 powder improved the mechanical properties of the composites at the optimum content [22]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observed the microstructural differences between ordinary mortars with and without Fe2O3 particles. The results showed that the composites containing Fe2O3 particles had a denser microstructure without microcracks and therefore had higher compressive and flexural strength [23]. The Fe2O3 nanoparticles could positively affect the mechanical properties of cement paste in a specific dose range, but inappropriate dosage had negative influences [24,25]. In addition, Fe2O3 particles affected the refractoriness of ordinary Portland cement paste, and studies showed that the addition of 1–2% Fe2O3 particles could improve the refractoriness of cement paste [26].

MgO is a basic oxide with more active chemical properties, which can react directly with water to form Mg(OH)2. The reaction will be accelerated under heating conditions [27]. Research showed that MgO could be used as a swelling agent for cementitious materials. MgO compensated for the shrinkage of cementitious materials and improved the cracking characteristics [28,29]. The higher the reactivity of MgO, the lower the autogenous shrinkage of the cement paste. MgO with higher activity hydrated faster and therefore produced more expansion at an early stage, which could more adequately offset the shrinkage of the cement paste. But MgO with excessive content also affected the mechanical properties of cement mortar [29]. The MgO over 8% content in ordinary Portland cement would slightly affect the compressive strength of cement mortar [30]. Researchers found that the best 28 days compressive strength and flexural strength of modified cement mortar specimens were obtained at 1.5% admixture of nano-MgO [31]. In terms of setting time, the incorporation of 5.0 and 7.5% MgO shortened the setting time of the cement mortar by 20 and 10 min, respectively, which indicated that MgO had some pro-setting effect [32]. In terms of durability, the incorporation of nano-MgO positively influenced cementitious materials, which enhanced the permeability and frost resistance of the cement mortar [33]. SEM showed that the incorporation of nano-MgO resulted in a denser internal structure of the cement paste [34], nano-MgO made the interface between cement and aggregate rougher and effectively reduced the generation of microcracks [35].

TiO2 is considered one of the best-performing white pigments in the world today, and the applications of TiO2 are mainly in the fields of coatings, cosmetics, and medicine [36]. The addition of TiO2 affected the hydration process and the development of the internal structure of the cement. The addition of TiO2 nanoparticles to ordinary Portland cement accelerated the early hydration of cement [37,38]. The hydration rate was proportional to the agglomerate size, and the TiO2 particles led to a better filling of the pores of cement mortar [39]. In cementitious materials, TiO2 nanoparticles could influence the porous structure of polymers. NMR and ultrasound were used to investigate the effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the hydration of cement. The results showed that TiO2 accelerated the formation of cement hydration products and reduced capillary porosity in the early stage of hydration [40].

Compared with natural gypsum, the main impurity components in titanium gypsum are Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2. The following problems exist in the current research works on titanium gypsum replacement in gypsum-slag cementitious materials (GSCM):

Research on industrial by-product gypsum mainly focuses on phosphogypsum and desulfurization gypsum. There is a lack of research on replacing titanium gypsum in GSCM.

The effect of specific oxide components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of GSCM is not apparent.

Whether there is any change in the microstructure of GSCM mixed with different oxide components. The mechanism of the action of oxide components on GSCM is not clear.

In order to solve the above problems, three kinds of oxide components of Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 in titanium gypsum are selected to be mixed with GSCM, respectively. This work studies the effects of the three oxides on the setting time and mechanical properties of GSCM, and explores the mechanism of the effect of the three oxide components on the GSCM. It is hoped that this research can solve the technical problems of titanium gypsum in the effective application of GSCM.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The raw materials used for the experiments are shown in Figure 1(a)–(g). The specific chemical composition for XRF analysis is shown in Table 1.

Raw materials. (a) Gypsum. (b) Slag. (c) MgO. (d) TiO2. (e) Fe2O3. (f) NaOH. (g) Sodium silicate.

Chemical composition of raw materials

| Samples | Chemical composition mass fractions (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | CaO | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | SO3 | TiO2 | MnO | Na2O | |

| Titanium gypsum | 1.69 | 36.7 | 1.06 | 8.79 | 1.48 | 37.9 | 0.876 | 0.332 | 0.168 |

| Gypsum | 0.24 | 32.47 | 0.12 | 2.90 | 0.02 | 39.14 | 0.03 | — | — |

| Slag | 27.1 | 41.2 | 13.9 | 0.387 | 7.8 | 2.565 | — | — | 0.467 |

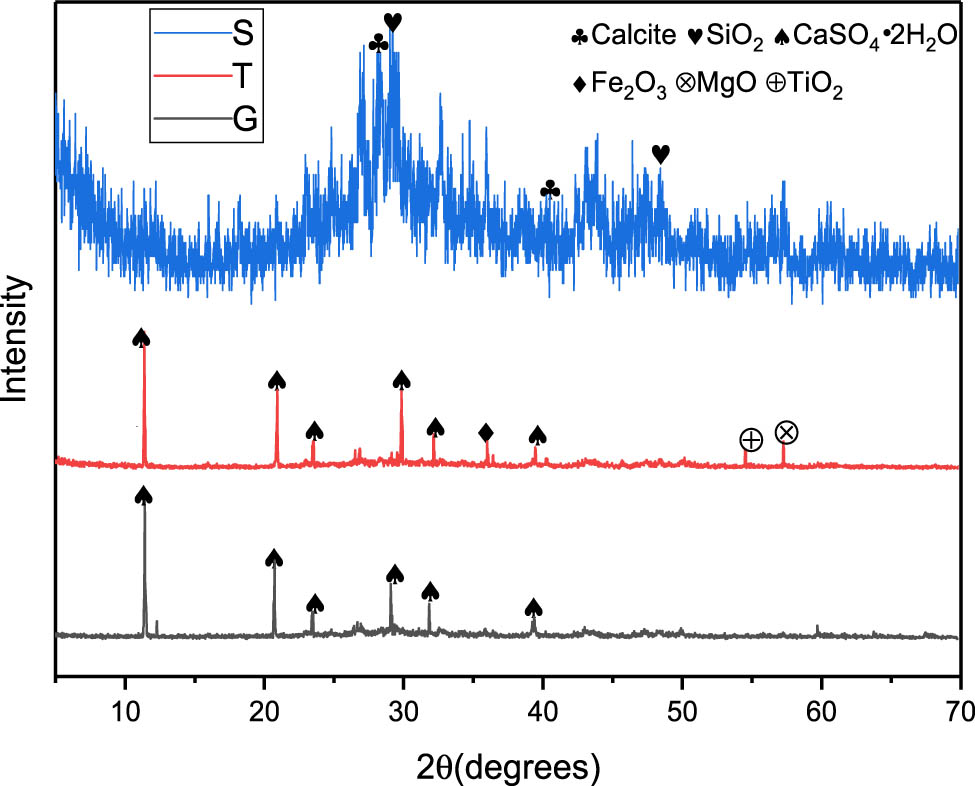

Titanium gypsum (T) is taken from the yard of Shandong Jinhong Titanium White Chemical Co., Ltd in China and has a reddish-yellow appearance. Slag (S) is taken from Lingshou County, Hebei Province, China, and has an off-white appearance. Gypsum (G) is taken from Yousheng Mineral Products Processing Plant in Lingshou County, Hebei Province, China, with a white appearance of natural gypsum dihydrate. The mineral composition of the raw materials is shown in Figure 2.

XRD analysis of raw materials.

Fe2O3 (F), MgO (M), and TiO2 (Ti) are all produced by Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co. The fineness is 325 mesh, and all are analytically pure.

The activator used in this experiment is anhydrous Na2SiO3 and NaOH, produced by the Tianjin Dengfeng Chemical Reagent Factory.

The standard sand used in the test is ISO 679 standard sand (GSB08-1337), produced by Xiamen Aisiou Standard Sand Co.

2.2 Testing design

2.2.1 Testing grouping

The precursors used in this experiment were slag and gypsum, and the alkali activator was doped at 4%. The range of three oxides doping ratio was determined by referring to impurity content in titanium gypsum shown in Table 1. Oxides were doped according to the mass fraction of precursors. 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20% were doped with Fe2O3; 0.6, 1.2, 1.8, 2.4, and 3% were doped with MgO; 0.4, 0.8, 1.2, 1.6, and 2% were doped with TiO2 and compared with the control group with 0% content of the three oxides. The specific experimental groups are shown in Table 2.

Testing groups

| Mix Id | T:S | G:S | Activator percentages (%) | Fe2O3 (%) | MgO (%) | TiO2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS | 3:7 | — | 4 | — | — | — |

| GS | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | — |

| F1 | — | 3:7 | 4 | 4 | — | — |

| F2 | — | 3:7 | 4 | 8 | — | — |

| F3 | — | 3:7 | 4 | 12 | — | — |

| F4 | — | 3:7 | 4 | 16 | — | — |

| F5 | — | 3:7 | 4 | 20 | — | — |

| M1 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | 0.6 | — |

| M2 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | 1.2 | — |

| M3 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | 1.8 | — |

| M4 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | 2.4 | — |

| M5 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | 3.0 | — |

| Ti1 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | 0.4 |

| Ti2 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | 0.8 |

| Ti3 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | 1.2 |

| Ti4 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | 1.6 |

| Ti5 | — | 3:7 | 4 | — | — | 2.0 |

Note: T:S and G:S are mass ratios.

2.2.2 Water-binder ratio

The best water consumption of paste test was determined under the Testing Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering (JTG 3420-2020) for standard consistency test. The mortar water-binder ratio (w/b) was fixed at 0.5 according to the requirements of the related technical specification [41].

2.2.3 Sample maintaining

According to the specification [41], each prepared mortar sample was placed in a standard maintenance box for 24 h before demolding. Each specimen was put into the maintenance room in turn after demolding, and the water surface height should be 2 cm higher than the top of the specimen. The temperature of the maintenance box was 20 ± 1°C, and the humidity was >90%.

2.3 Test methods

2.3.1 Setting time

According to the technical specification [41], after the standard consistency test, determine the water consumption, and pre-dissolve the solid activator in water in advance. Put the precursors and solution in a mixing pot, stir slowly for 120 s, stop for 15 s, then stir quickly for 120 s. The setting time was measured using the Vicat apparatus. Measurements should be taken at 5 min intervals (or less) as the initial setting time is approached. Measurements should be taken at 15 min intervals (or less) as the final setting time is approached. Measure again as soon as the initial or final setting is reached. The two conclusions were the same to determine the arrival of the initial or final setting time.

2.3.2 Mortar strength

According to the technical specification [41], the fresh mortar mixture was poured into the 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm triplex test mold two times, and each time it was run, it vibrated 60 times. Then, it was maintained under standard environmental conditions (temperature 20°C ± 1°C, relative humidity >90%) for 24 h. After removing from the mold, the specimens were placed in the sink and maintained under standard conditions until they reached the ages (3, 7, and 28 days) for testing. The compressive and flexural strength of the cementitious materials were measured using cement sand compressive and flexural apparatus. The average values of the three specimens were determined as the flexural and compressive strength of the mortar for the corresponding curing times.

2.3.3 Micro-analysis

Crushed specimens were kept in anhydrous ethanol for 7 days to stop the hydration reaction after the flexural and compressive strength tests [42,43]. Then, the specimens were removed from the anhydrous ethanol and dried to a dehydrated state. The morphology and elemental composition of the hydration products were determined using SEM and EDS to determine the hydration products of cementitious materials and the reaction mechanism. The instrument used was a QUANTAFEG 250 field emission scanning electron microscope manufactured by FEI, USA. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed using a diffractometer system XRD D8. The source was operated at a voltage of 40 KV using Cu Kα radiation with a scanning range of 10°–70°. The samples were scanned at a speed of 3°·min−1 with a step size of 0.02° to obtain the data for quantitative analysis. TG-DTG used the SDT650 integrated thermal analyzer made by TA, USA, with a temperature range of 30–900°C, a nitrogen atmosphere, and a heating rate of 10°C·min−1.

2.3.4 Expansion ratio

According to the technical specification [44], the 25 mm × 25 mm × 280 mm test mold was wiped clean and assembled. The inner wall was evenly brushed with a layer of machine oil, and the nail head was inserted into the small holes on the end plate of the test mold. The nail head was inserted at a depth of 10 ± 1 mm. The homogeneous mortar was mixed and filled into the triple test mold three times, and vibrated evenly. Then, the mold was taken off after curing in the standard curing box until 24 h. After demolding, the nail heads at both ends of the specimens were wiped clean and immediately put into the comparator to measure the initial length

where

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Setting time

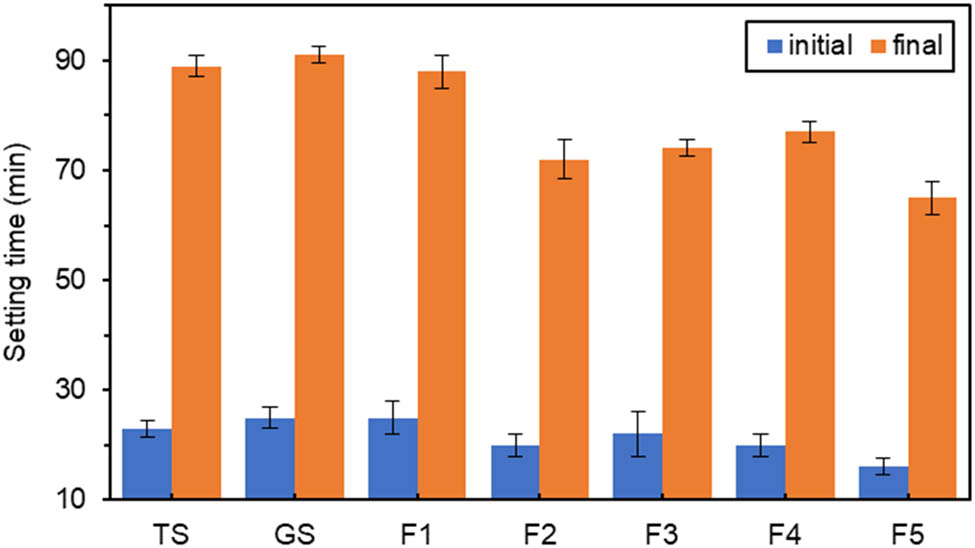

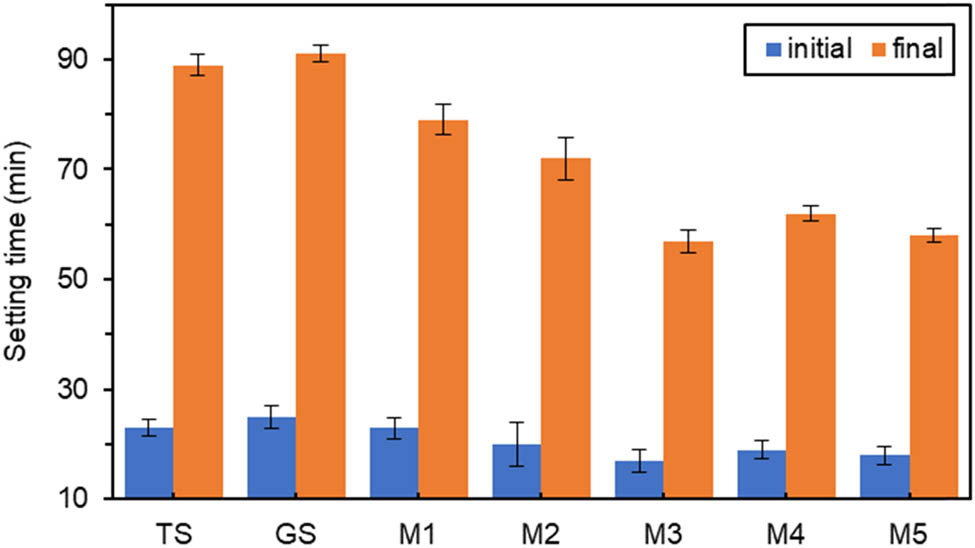

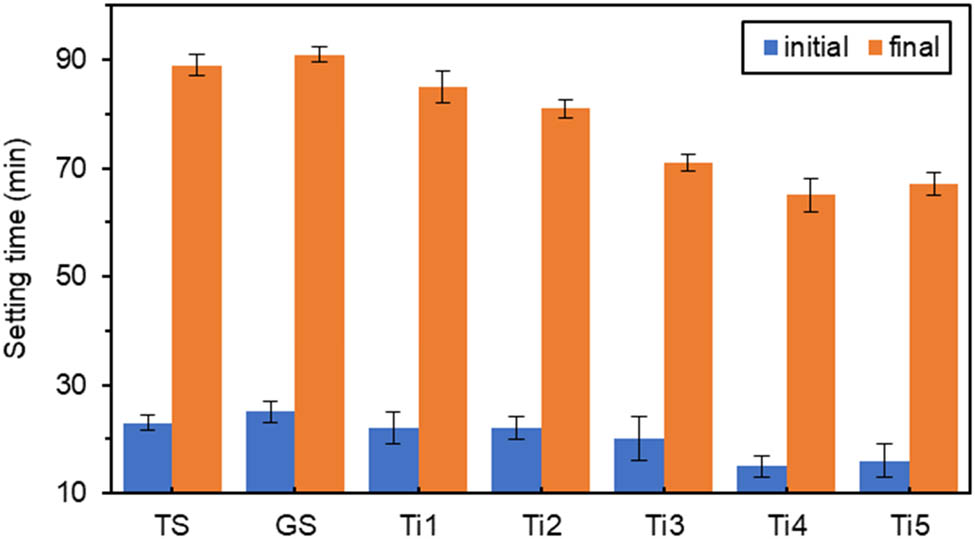

According to Figures 3–5, the initial and final setting times were slightly prolonged for GS compared to TS. Still, the difference between them was not very large, which indicated that titanium gypsum and gypsum had similar effects on the setting time properties of cementitious materials. The results showed that setting times of the specimens doped with the oxide components were all shorter than that of GS. With the increase in oxide dosage, the initial and final setting times roughly showed a decreasing trend with small fluctuations.

Effect of different amounts of Fe2O3 on setting time.

Effect of different amounts of MgO on setting time.

Effect of different amounts of TiO2 on setting time.

In Figure 3, when Fe2O3 doping was 4%, there was no significant change in the initial setting time, and the final setting time was only shortened by 3.3%, which had little effect. When the Fe2O3 doping was 8%, the initial and final setting times were significantly shortened. The initial setting time of F2 was shortened by 20%, and the final setting time was shortened by 21% compared with GS. When the Fe2O3 doping was 20%, the initial and final setting time was greatly shortened. 36% of the initial setting time and 29% of the final setting time were shortened for F5 compared with GS, which had the most significant coagulation promotion effect and significantly shortened the setting time of GSCM. This was consistent with the related study that iron-rich precursors had fast-setting properties [45].

In Figure 4, when the MgO doping was very low at 0.6%, the initial setting time of M1 was only 8% shorter than that of GS, and the final setting time was 13% shorter than that of GS. The changes were not noticeable. When the MgO content was 1.8%, the initial and final setting times were the lowest at 17 and 57 min, respectively. Compared with GS, M3 had the most significant time reduction of 32% in the initial setting time and 37.4% in the final setting time. This was consistent with the hydration of slag promoted by high-active MgO [46].

In Figure 5, when TiO2 doping was very low at 0.4%, Ti1 was shortened by 12% compared to GS initial setting time, and final setting time was only shortened by 6.6%, which was a slight change. TiO2 doping of 1.6% showed the lowest values of initial and final setting times of 15 and 65 min, respectively. Ti4 showed a significant reduction of 40% in the initial setting time and 28.6% in the final setting time compared to GS. The generated pro-setting phenomenon was similar to that of the addition of TiO2 nanoparticles to ordinary Portland cement could accelerate the early hydration of cement [37,38].

3.2 Mechanical property

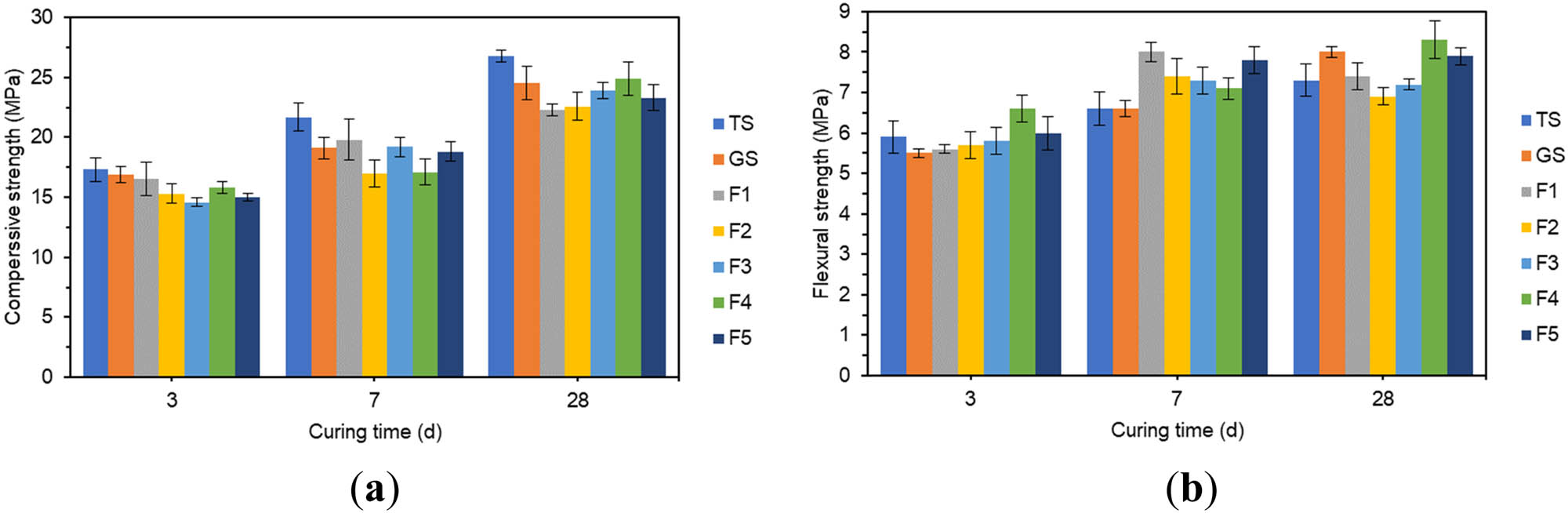

In Figure 6(a), the compressive strengths of all specimens showed an increasing trend with the increase in age. The 3 days compressive strength of GSCM with Fe2O3 reached about 65% of the 28 days compressive strength, and the 7 days compressive strength reached about 80% of the 28 days compressive strength. This indicated a rapid increase in early compressive strength. The incorporation of Fe2O3 slightly affected the early compressive strength of GSCM. 3 days compressive strength was lowest at 12% Fe2O3, which was 13.6% lower than the 3 days compressive strength of GS. 7 days compressive strength was lowest at 8% Fe2O3, which was 11% lower than the 7 days compressive strength of GS. The lowest value of 28 days compressive strength occurred at 4% Fe2O3, which was 9% lower than the 28 days compressive strength of GS. The effect of Fe2O3 doping on the variation in compressive strength of GSCM was not significant.

The effect of different amounts of Fe2O3 on compressive strength and flexural strength: (a) compressive strength and (b) flexural strength.

In Figure 6(b), the early flexural strength of GSCM grew rapidly, and the later flexural strength grew slowly. The 28 days flexural strengths of F1, F2, and F3 were 7.5, 6.8, and 1.4% lower than the 7 days flexural strengths. GSCM improved its 3 days and 7 days flexural strength due to increased Fe2O3 dosage.

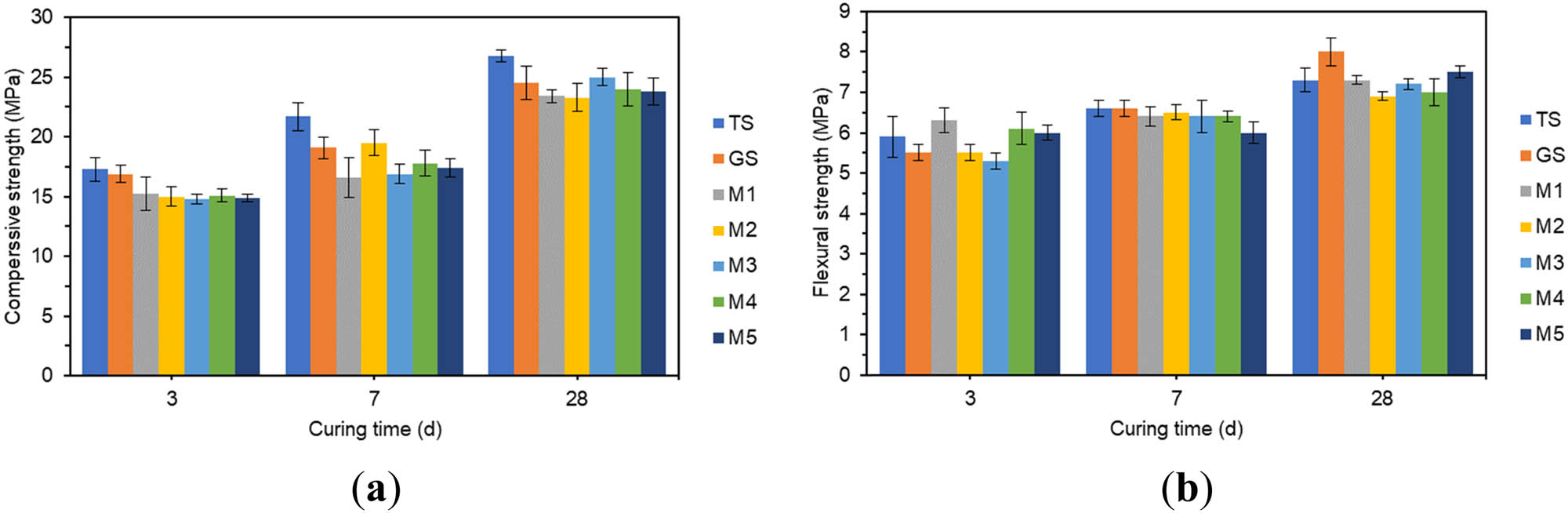

In Figure 7(a), the compressive strength of the specimens mixed with different contents of MgO all increased with the extension of the curing age. The compressive strength increased rapidly in the first 7 days. The 3 days compressive strength reached about 63% of 28 days compressive strength, and 7 days compressive strength reached about 75% of 28 days compressive strength. The specimen with 1.8% MgO doping had the lowest 3 days compressive strength. The specimen with 0.6% MgO doping had the lowest 7 days compressive strength. M3 and M1 were 11.8 and 13.1% lower than GS, respectively. With the extension of the curing age, the compressive strength of the specimens with each MgO doping amount at 28 days did not differ much. There was little difference in the compressive strength of the specimens with different MgO content at 28 days.

The effect of different amounts of MgO on compressive strength and flexural strength: (a) compressive strength and (b) flexural strength.

In Figure 7(b), the doping of MgO slightly enhanced the 3 days flexural strength of the specimens but it slightly reduced the 7 days and 28 days flexural strength. The 7 days flexural strength of specimens with 3% MgO doping was the lowest, 9.1% lower than that of GS. The 28 days flexural strength of specimens with 1.2% MgO doping was the lowest, which was 13% lower than that of GS. The effect of MgO on the flexural strength of specimens was not significant.

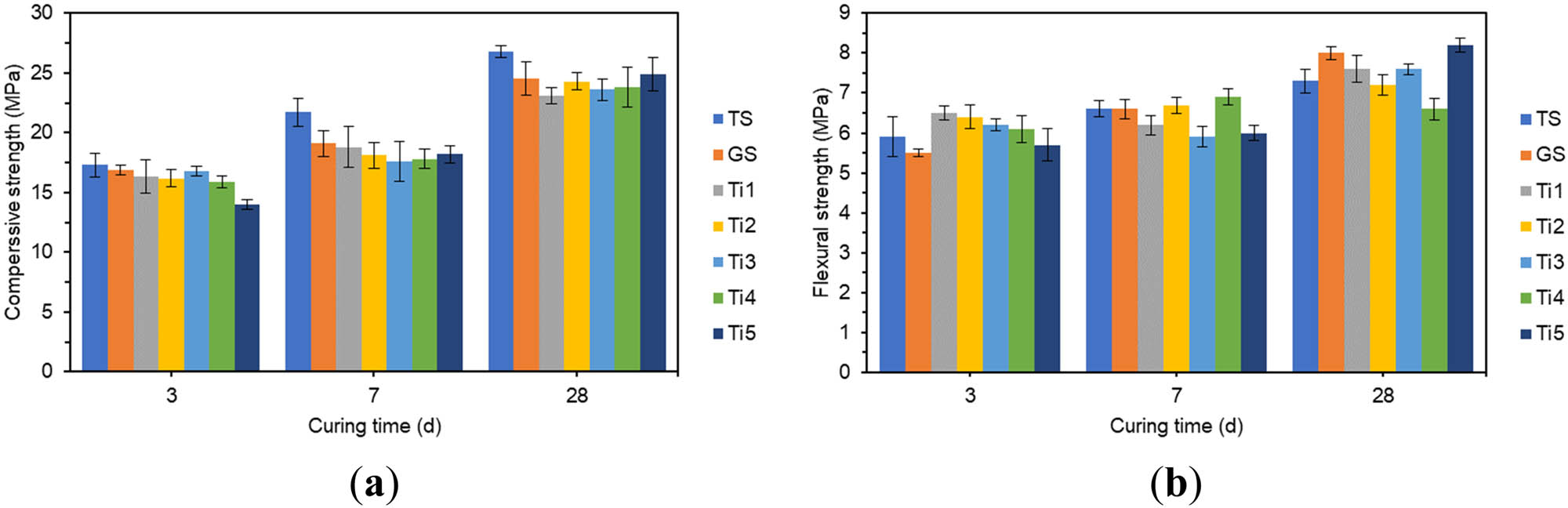

In Figure 8(a), the compressive strength of all specimens doped with TiO2 increased with the extension of the curing age. The 3 days and 7 days compressive strength increased rapidly, and the 7 days compressive strength already reached more than 70% of the 28 days compressive strength. With the increase in TiO2 doping, the 3 days compressive strength reduced with different degrees, which indicated that TiO2 adversely affected the early strength of specimens. The specimen with 2% TiO2 doping had the lowest 3 days compressive strength, which was 17.2% lower than the 3 days compressive strength of GS. The specimen with 1.2% TiO2 doping had the lowest 7 days compressive strength, which was 7.9% lower than the 7 days compressive strength of GS. The specimen with 0.4% TiO2 doping had the lowest 28 days compressive strength, which was 5.7% lower than the 28 days compressive strength of GS, and the strength effect was minimal.

The effect of different amounts of TiO2 on compressive strength and flexural strength: (a) compressive strength and (b) flexural strength.

In Figure 8(b), all the specimens doped with TiO2 showed different degrees of increase in 3 days flexural strength. The specimens with TiO2 doping of 0.4% had the highest 3 days flexural strength, which increased by 18.2% over the 3 days flexural strength of GS. The 7 days flexural strength of the specimens doped with TiO2 did not change significantly. When the TiO2 doping was 2%, the maximum 28 days flexural strength was 8.2 MPa.

3.3 Expansion ratio

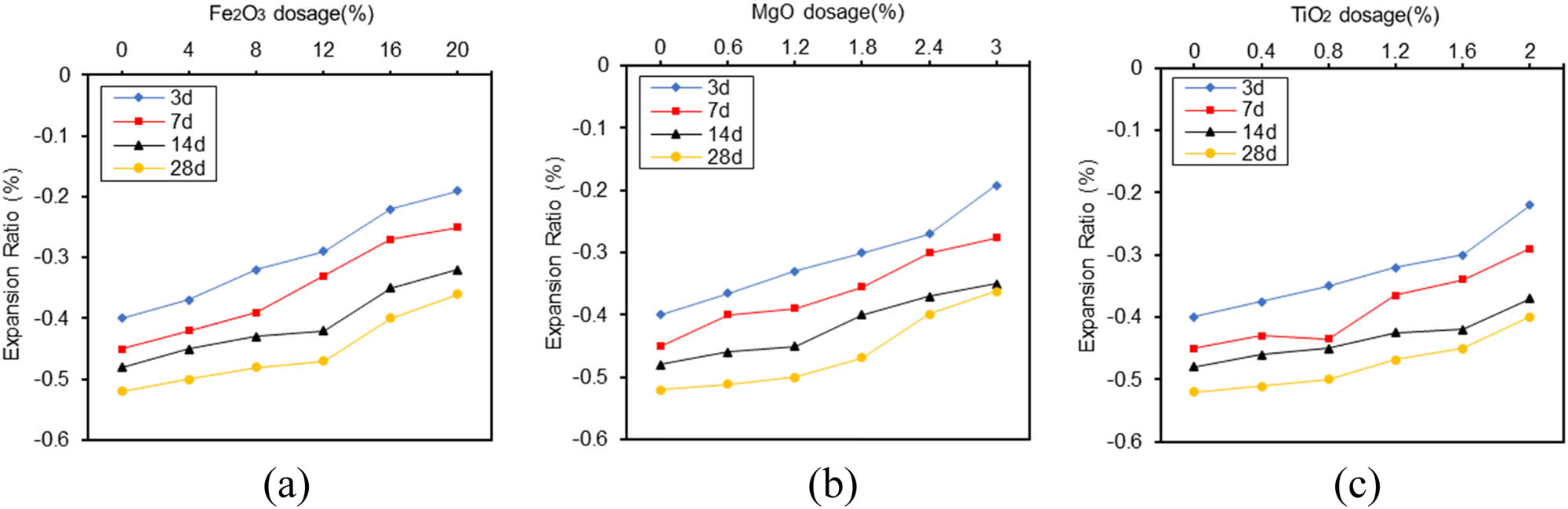

In Figure 9(a)–(c), it is shown that GSCM produced volumetric shrinkage by testing the expansion rate of GSCM at different ages. Shrinkage rate increased with the ages of maintenance. The addition of three different ratios of oxides to GSCM slightly reduced the shrinkage of GSCM. The shrinkage of GSCM decreased with the increase in oxide doping. It shows that the three oxides Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 reduce the shrinkage of GSCM.

GSCM expansion ratio at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days. (a) Fe2O3; (b) MgO; (c) TiO2.

3.4 SEM-EDS analysis

The hydration reaction products of the gelling system formed by slag and gypsum were mainly AFt crystal and C–(A)–S–H gels [47], and the main reactions are shown in Eqs. (2) and (3).

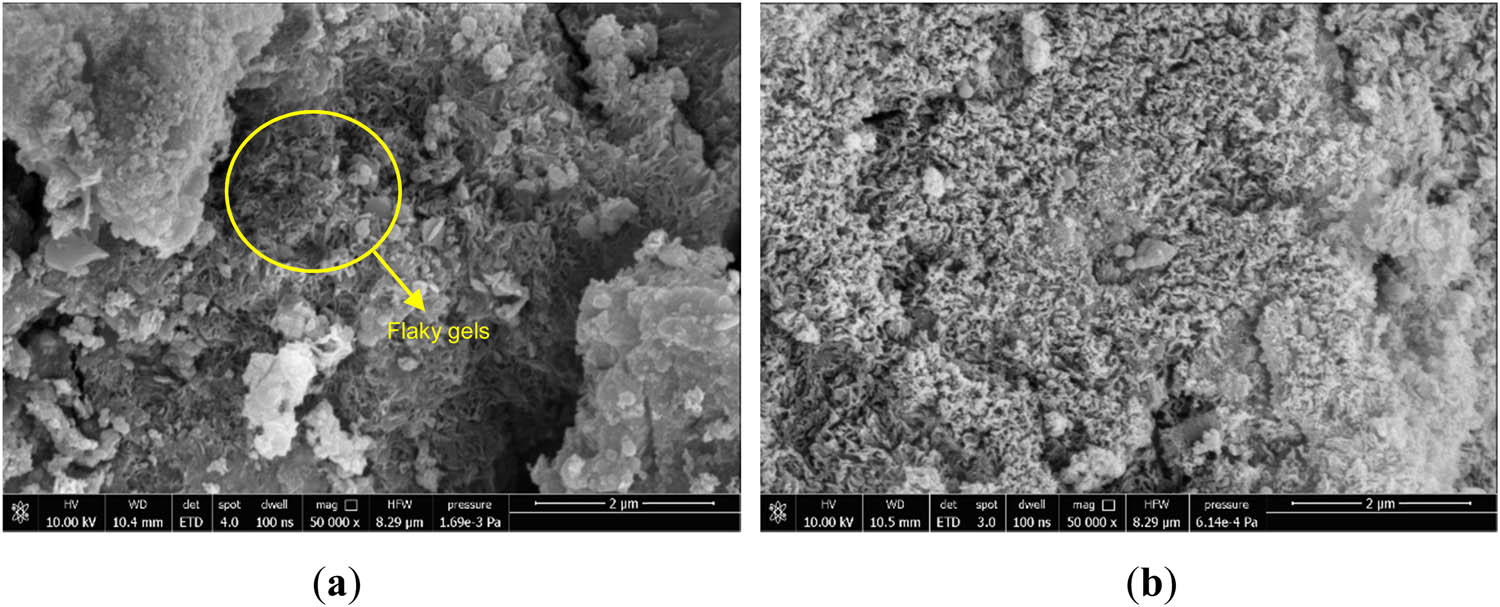

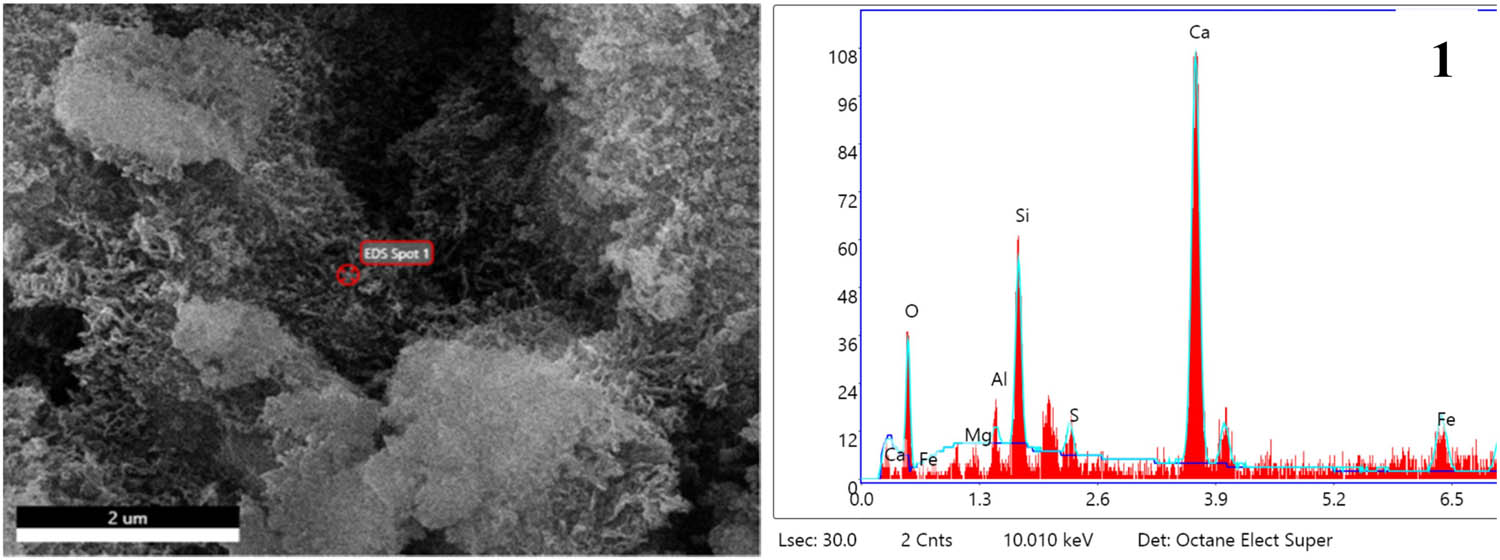

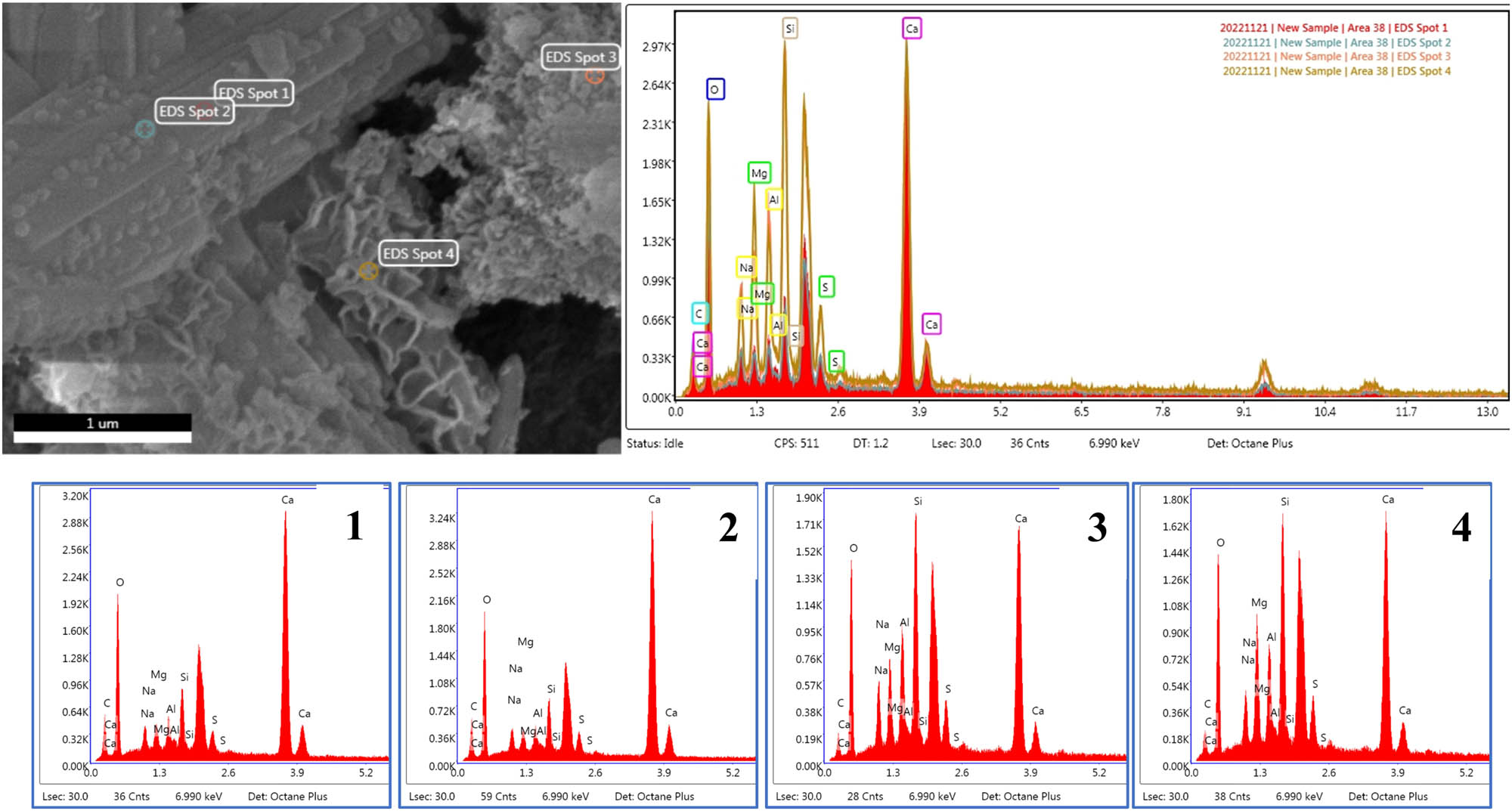

In Figure 10(a), it was found that in addition to the C–(A)–S–H gels, the incorporation of Fe2O3 resulted in the generation of some flaky gels within the hydrated system. EDS scanning was performed on the flaky gels, and the EDS analysis results in Figure 11 showed that the material should be Fe-rich C–(A)–S–H gels [48,49]. Under alkaline conditions, a large amount of

SEM morphology of F5 specimens at different maintenance ages: (a) 3 days and (b) 28 days.

EDS image of spot 1 of F5 specimen at 3 days hydration age.

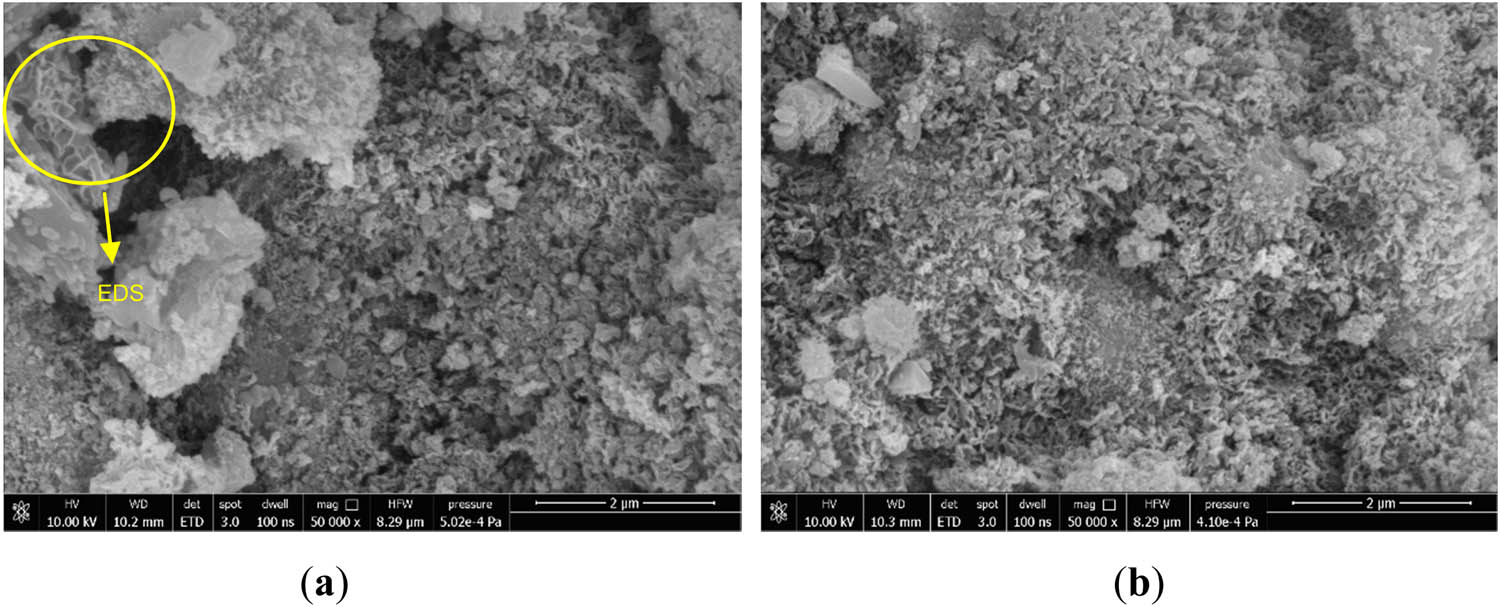

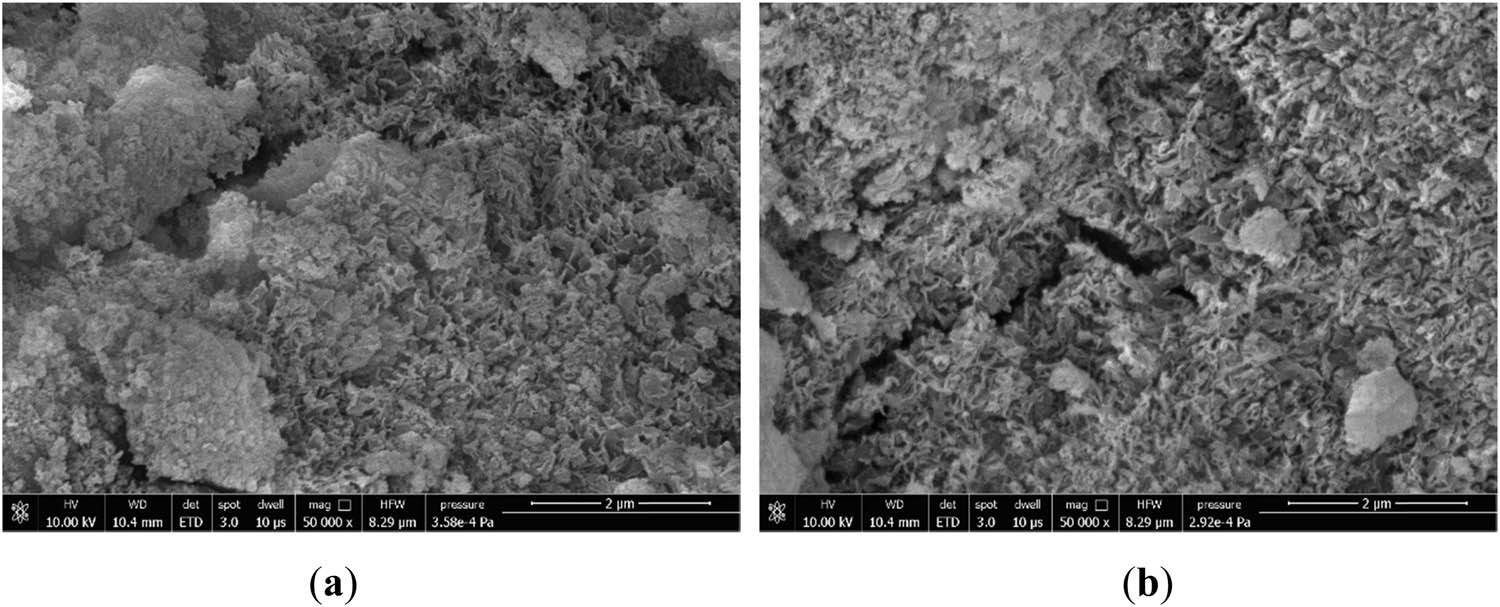

In Figure 12(a), it was observed that in addition to the C–(A)–S–H gels, the incorporation of MgO caused the generation of lamellar hydration products inside the system. Figure 13 shows the EDS analysis of the lamellar material, points 3 and 4 both contained a high content of Mg and Si elements, and the growth state of point 3 was denser than point 4. Combined with the literature analysis, point 4 was a combination of low polymerization degree M–S–H and Mg(OH)2, and point 3 was a high polymerization degree Mg(OH)2 and M–S–H [51,52]. The high polymerization degree M–S–H had properties similar to C–(A)–S–H [27]. A low degree of polymerization M–S–H and Mg(OH)2 led to a more sparse structure of the material throughout, which slightly affected the 3 days compressive strength. In Figure 12(b), the hydration reaction proceeded continuously, and the fibrous gels generated inside the system kept increasing. The dense C–(A)–S–H and M–S–H gels were mixed, and the pores within the structure were gradually filled and interlaced to grow into a dense three-dimensional mesh structure, which macroscopically exhibited a good 28 days compressive strength. The main reactions after adding MgO are shown in Eqs. (4) and (5).

SEM microscopic morphology of M5 specimens at different maintenance ages: (a) 3 days and (b) 28 days.

EDS image of spot 1–4 of M5 specimen at 3 days hydration age.

In Figure 14(a), when doped with TiO2, it was observed that the internal structure of the whole hydrated system had more tiny pores, and the structure was similar to Figures 10(a) and 12(a), which was looser. The microscopic morphological laxity was mainly due to the non-uniform dispersion of TiO2 particles in the cementitious materials at the early hydration stage [53,54], which slightly affected the early strength of the matrix. No new hydration products were found to be generated after TiO2 incorporation, but TiO2 acted as a pore filler in the matrix and accelerated hydration [55]. In Figure 14(b), as the hydration reaction continued, the microscopic morphology showed that the pores gradually became smaller, and the whole structure developed into a dense mesh-like structure similar to that of Figures 10(b) and 12(b). This was mainly due to the fact that TiO2 particles reduced the porosity and roughness and densified the C–(A)–S–H, which enhanced the strength of the polymer [39].

SEM microscopic morphology of Ti5 specimens at different maintenance ages: (a) 3 days and (b) 28 days.

Finally, the 28 days micrograph morphologies of the three oxides doped with Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 were similar, with dense reticular structures and stable morphologies. This indicated that none of the three oxide components significantly affected the 28 days strength of the cementitious materials.

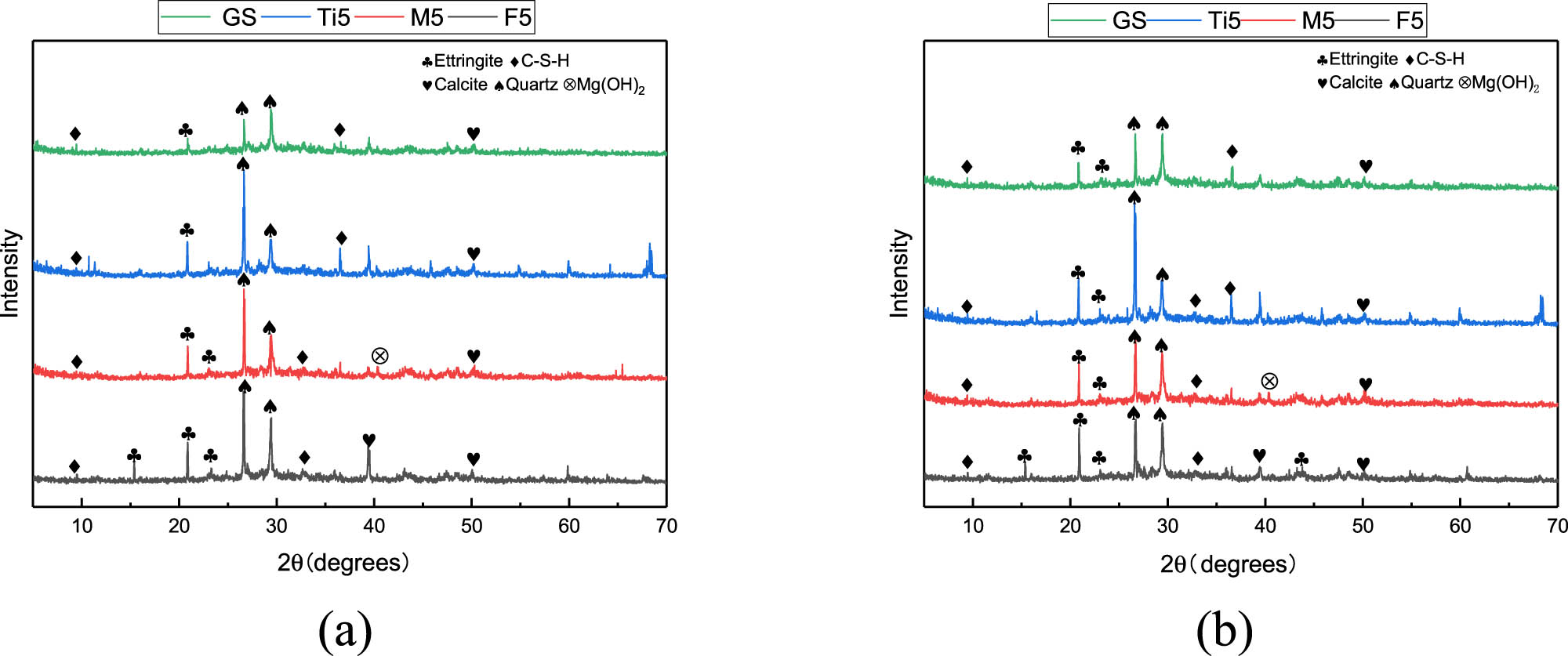

3.5 XRD

In Figure 15(a) and (b), all the XRD energy spectra can observe diffraction peaks pointing to the presence of C–(A)–S–H, ettringite, and calcite crystalline phases. For the same sample, the types of hydration products did not change with the age of hydration. It was found that with the doping of Fe2O3, more diffraction peaks pointing to ettringite and C–(A)–S–H gels could be observed. With the doping of MgO, diffraction peaks capable of pointing to the presence of Mg(OH)2 crystalline phase were detected. However, diffraction peaks pointing to M–S–H were not detected, and this finding confirmed earlier studies that the combination of Mg with silica slag consumed to form M–S–H, which was difficult to detect by XRD [46,56]. No new crystalline phase was detected with the doping of TiO2, which indicated that the doping of TiO2 did not lead to the generation of new hydration products.

XRD spectra of different specimens: (a) 3 days and (b) 28 days.

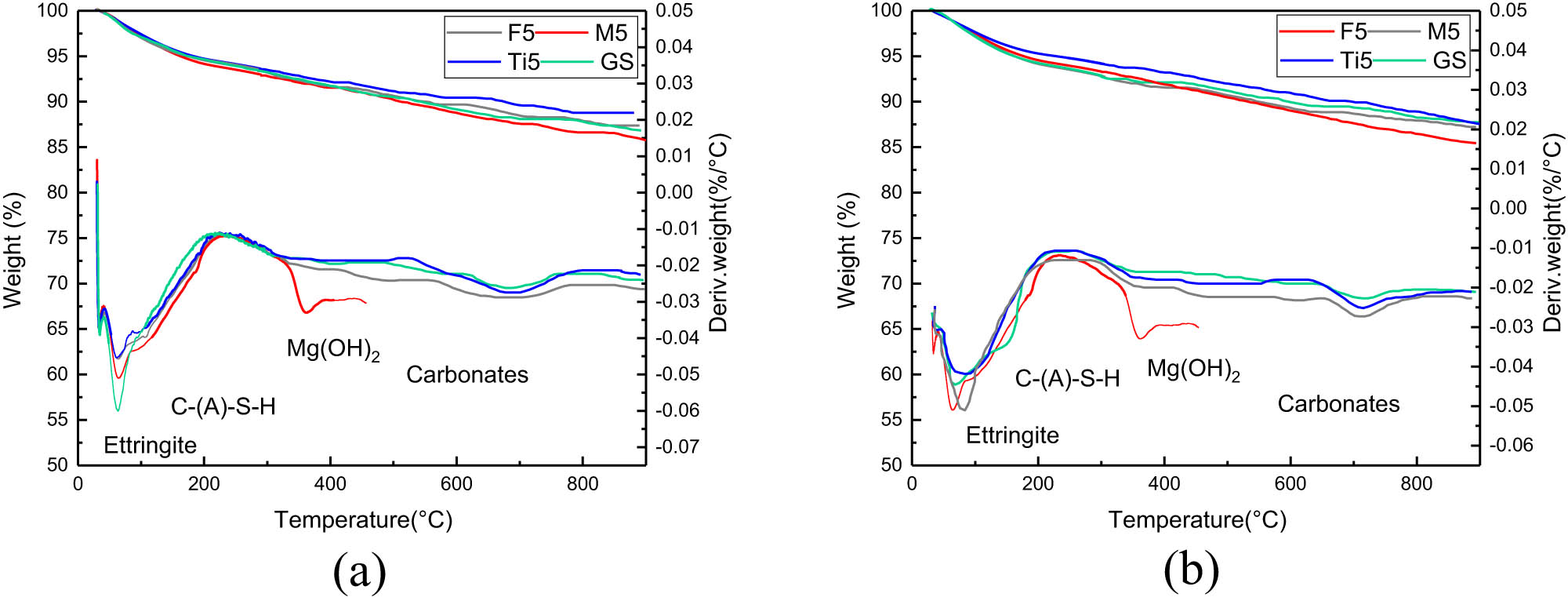

3.6 Thermogravimetric analysis (TG-DTG)

TG and the first derivative of TG (DTG) signs are direct and very fast measurements of the weight loss and its rate of occurrence during analysis, by which different materials are identified based on their thermal characteristics. The TG-DTG curves for 3 and 28 days are shown in Figure 16. From Figure 16, it can be concluded that for the same sample, the types of hydration products did not change with the age of hydration.

TG-DTG curves of specimens: (a) 3 days and (b) 28 days.

In Figure 16, significant mass loss was observed in each group of specimens when the temperature was heated from 30 to 900°C. The first heat absorption peak appeared around 100°C, which corresponded to the dehydration caused by the combined water in the C–(A)–S–H gels, Ettringite hydration products. The second heat absorption peak occurred at a temperature of about 350°C. This might be due to the dehydration of hydroxyl groups in the hydration product crystals in the specimen, while the heat absorption peaks from the decomposition of Mg(OH)2 in the specimen M5 was shown in Figure 16(a) and (b). The third heat absorption peak appeared around 700°C, this heat absorption peak was mainly caused by the decomposition of carbonate impurity in the specimen.

4 Conclusion

Based on the study of the effects of different doping amounts of Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2 on the setting time and mechanical properties of GSCM, the following conclusions were drawn:

The three oxide components, Fe2O3, MgO, and TiO2, had similar patterns of influence on the properties of GSCM. All three oxides had a certain procoagulant effect, which slightly affected the early strength of GSCM, but did not have a significant effect on 28 days strength.

The incorporation of Fe2O3 affected the hydration process of GSCM. Relatively loose Fe-rich gelatinous hydration products were generated in the early stage, and as the hydration reaction continued, an iron-rich gelatinous hydration similar to the C–(A)–S–H product was generated with a dense structure in the later stage. The incorporation of MgO affected the hydration process of GSCM. The system generated loose Mg(OH)2 in the early stage, and the dense C–(A)–S–H and M–S–H gel substances generated in the later stage would lead to continuous and stable increase in strength. No new hydration products were found to be generated by the incorporation of TiO2. Higher dosages of Fe2O3 and MgO did not affect the volume stability of cementitious materials.

The microscopic morphology of the three oxides mixed into the GSCM is similar, and the effect on the 28 days strength of the GSCM is not significant. Therefore, GSCM can be prepared using titanium gypsum instead of gypsum, but attention should be paid to the difference in setting time and early strength required for the use scenarios.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments, which have improved the quality of the work.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022ME133), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (51908342).

-

Author contributions: Yilin Li: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft preparation, and writing – review and editing. Zhirong Jia: Conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, and writing – review and editing. Shuaijun Li: conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing – original draft preparation. Peiqing Li: writing – original draft preparation, formal analysis, and investigation. Xuekun Jiang: writing – review and editing, supervision, and data curation. Zhong Zhang: data curation, investigation, and writing – review and editing. Bin Yu: writing – review and editing, investigation, and data curation. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Zhu, X., S. Zheng, Y. Zhang, Z. Z. Fang, M. Zhang, P. Sun, et al. Potentially more ecofriendly chemical pathway for production of high-purity TiO2 from titanium slag. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, Vol. 7, No. 5, 2019, pp. 4821–4830.10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05102Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zha, F., B. Qiao, B. Kang, L. Xu, C. Chu, and C. Yang. Engineering properties of expansive soil stabilized by physically amended titanium gypsum. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 303, 2021, id. 124456.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124456Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gazquez, M. J., J. P. Bolivar, F. Vaca, R. García-Tenorio, and A. Caparros. Evaluation of the use of TiO2 industry red gypsum waste in cement production. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 37, 2013, pp. 76–81.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.12.003Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang, J., Y. Yan, Z. Hu, X. Xie, and L. Yang. Properties and hydration behavior of Ti-extracted residues-red gypsum based cementitious materials. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 218, 2019, pp. 610–617.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.099Search in Google Scholar

[5] Du, C. W. and G. Z. Li. Study on effect and action mechanism of different superplasticizer on properties of titanium gypsum. Applied Mechanics and Materials, Vol. 468, 2013, pp. 24–27.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.468.24Search in Google Scholar

[6] Gázquez, M. J., M. Contreras, S. M. Pérez-Moreno, J. L. Guerrero, M. Casas-Ruiz, and J. P. Bolívar. A review of the commercial uses of sulphate minerals from the titanium dioxide pigment industry: the case of Huelva (Spain). Minerals, Vol. 11, No. 6, 2021, id. 575.10.3390/min11060575Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang, J., Y. Yan, and Z. Hu. Preparation and characterization of foamed concrete with Ti-extracted residues and red gypsum. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 171, 2018, pp. 109–119.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.072Search in Google Scholar

[8] Borhan, M. Z. and T. Y. Nee. Synthesis of TiO2 nanopowders from red gypsum using EDTA as complexing agent. Journal of Nanostructure in Chemistry, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2014, pp. 71–76.10.1007/s40097-014-0137-7Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen, Q., W. Ding, H. Sun, and T. Peng. Synthesis of anhydrite from red gypsum and acidic wastewater treatment. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 278, 2021, id. 124026.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124026Search in Google Scholar

[10] Rosli, N. A., H. A. Aziz, M. R. Selamat, and L. L. P. Lim. A mixture of sewage sludge and red gypsum as an alternative material for temporary landfill cover. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 263, 2020, id. 110420.10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110420Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Zhai, W., Y. Dai, W. Zhao, H. Yuan, D. Qiu, J. Chen, et al. Simultaneous immobilization of the cadmium, lead and arsenic in paddy soils amended with titanium gypsum. Environmental Pollution, Vol. 258, 2020, id. 113790.10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113790Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Tang, L., C. Liao, Y. Guo, and Y. Zhang. Controllable preparation of Ag-SiO2 composite nanoparticles and their applications in fluorescence enhancement. Materials, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2022, id. 201.10.3390/ma16010201Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Liu, S. and L. Wang. Investigation on strength and pore structure of supersulfated cement paste. Materials Science, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2018, pp. 319–326.10.5755/j01.ms.24.3.18300Search in Google Scholar

[14] Wu, Q., Q. Xue, and Z. Yu. Research status of super sulfate cement. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 294, 2021, id 126228.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126228Search in Google Scholar

[15] Angulski da Luz, C. and R. D. Hooton. Influence of supersulfated cement composition on hydration process. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2019, id. 04019090.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002720Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wu, M., W. Shen, X. Xiong, L. Zhao, Z. Yu, H. Sun, et al. Effects of the phosphogypsum on the hydration and microstructure of alkali activated slag pastes. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 368, 2023, id. 130391.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130391Search in Google Scholar

[17] Huang, Y., J. Lu, F. Chen, and Z. Shui. The chloride permeability of persulphated phosphogypsum-slag cement concrete. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Mater. Sci. Ed., Vol. 31, No. 5, 2016, pp. 1031–1037.10.1007/s11595-016-1486-5Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang, Z., Z. Shui, T. Sun, X. Li, and M. Zhang. Recycling utilization of phosphogypsum in eco excess-sulphate cement: Synergistic effects of metakaolin and slag additives on hydration, strength and microstructure. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 358, 2022, id. 131901.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131901Search in Google Scholar

[19] Andrade Neto, J. S., J. D. Bersch, T. S. M. Silva, E. D. Rodríguez, S. Suzuki, and A. P. Kirchheim. Influence of phosphogypsum purification with lime on the properties of cementitious matrices with and without plasticizer. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 299, 2021, id. 123935.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123935Search in Google Scholar

[20] Laanaiya, M. and A. Zaoui. Preventing cement-based materials failure by embedding Fe2O3 nanoparticles. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 260, 2020, id. 120466.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120466Search in Google Scholar

[21] Oltulu, M. and R. Şahin. Effect of nano-SiO2, nano-Al2O3 and nano-Fe2O3 powders on compressive strengths and capillary water absorption of cement mortar containing fly ash: A comparative study. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 58, 2013, pp. 292–301.10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.12.014Search in Google Scholar

[22] Siang Ng, D., S. C. Paul, V. Anggraini, S. Y. Kong, T. S. Qureshi, C. R. Rodriguez, et al. Influence of SiO2, TiO2 and Fe2O3 nanoparticles on the properties of fly ash blended cement mortars. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 258, 2020, id. 119627.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119627Search in Google Scholar

[23] Valizadeh Kiamahalleh, M., A. Alishah, F. Yousefi, S. Hojjati Astani, A. Gholampour, and M. Valizadeh Kiamahalleh. Iron oxide nanoparticle incorporated cement mortar composite: correlation between physico-chemical and physico-mechanical properties. Materials Advances, Vol. 1, No. 6, 2020, pp. 1835–1840.10.1039/D0MA00295JSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Feng, H., L. Lv, Y. Pang, Z. Wang, D. Gao, and Z. Zhang. Experimental study on the effects of the fiber and nano-Fe2O3 on the properties of the magnesium potassium phosphate cement composites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 9, No. 6, 2020, pp. 14307–14320.10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.10.030Search in Google Scholar

[25] Sanjuán, M. A., C. Argiz, J. C. Gálvez, and E. Reyes. Combined effect of nano-SiO2 and nano-Fe2O3 on compressive strength, flexural strength, porosity and electrical resistivity in cement mortars. Materiales de Construccion, Vol. 68, No. 329, 2018, id. 56211707.10.3989/mc.2018.10716Search in Google Scholar

[26] Heikal, M. Characteristics, textural properties and fire resistance of cement pastes containing Fe2O3 nano-particles. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, Vol. 126, No. 3, 2016, pp. 1077–1087.10.1007/s10973-016-5715-0Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zheng, J., X. Sun, L. Guo, S. Zhang, and J. Chen. Strength and hydration products of cemented paste backfill from sulphide-rich tailings using reactive MgO-activated slag as a binder. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 203, 2019, pp. 111–119.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.047Search in Google Scholar

[28] Mo, L., M. Deng, and A. Wang. Effects of MgO-based expansive additive on compensating the shrinkage of cement paste under non-wet curing conditions. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 34, No. 3, 2012, pp. 377–383.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.11.018Search in Google Scholar

[29] Mo, L., M. Liu, A. Al-Tabbaa, and M. Deng. Deformation and mechanical properties of the expansive cements produced by inter-grinding cement clinker and MgOs with various reactivities. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 80, 2015, pp. 1–8.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.01.066Search in Google Scholar

[30] Ye, Q., K. Yu, and Z. Zhang. Expansion of ordinary Portland cement paste varied with nano-MgO. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 78, 2015, pp. 189–193.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.12.113Search in Google Scholar

[31] Yao, K., D. An, W. Wang, N. Li, C. Zhang, and A. Zhou. Effect of nano-MgO on mechanical performance of cement stabilized silty clay. Marine Georesources & Geotechnology, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2019, pp. 250–255.10.1080/1064119X.2018.1564406Search in Google Scholar

[32] Polat, R., R. Demirboğa, and F. Karagöl. The effect of nano-MgO on the setting time, autogenous shrinkage, microstructure and mechanical properties of high performance cement paste and mortar. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 156, 2017, pp. 208–218.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.168Search in Google Scholar

[33] Hay, R. and K. Celik. Hydration, carbonation, strength development and corrosion resistance of reactive MgO cement-based composites. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 128, 2020, id. 105941.10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.105941Search in Google Scholar

[34] Moradpour, R., E. Taheri-Nassaj, T. Parhizkar, and M. Ghodsian. The effects of nanoscale expansive agents on the mechanical properties of non-shrink cement-based composites: The influence of nano-MgO addition. Composites Part B: Engineering, Vol. 55, 2013, pp. 193–202.10.1016/j.compositesb.2013.06.033Search in Google Scholar

[35] Khandaker, M., Y. Li, and T. Morris. Micro and nano MgO particles for the improvement of fracture toughness of bone-cement interfaces. Journal of Biomechanies, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2013, pp. 1035–1039.10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.12.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Zhao, P., H. Wang, S. Wang, P. Du, L. Lu, and X. Cheng. Assessment of nano-TiO2 enhanced performance for photocatalytic polymer-sulphoaluminate cement composite coating. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials, Vol. 28, No. 6, 2018, pp. 2439–2446.10.1007/s10904-018-0923-7Search in Google Scholar

[37] Bost, P., M. Regnier, and M. Horgnies. Comparison of the accelerating effect of various additions on the early hydration of Portland cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 113, 2016, pp. 290–296.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.052Search in Google Scholar

[38] Chen, J., S.-c Kou, and C.-s Poon. Hydration and properties of nano-TiO2 blended cement composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 34, No. 5, 2012, pp. 642–649.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2012.02.009Search in Google Scholar

[39] Shafaei, D., S. Yang, L. Berlouis, and J. Minto. Multiscale pore structure analysis of nano titanium dioxide cement mortar composite. Materials Today Communications, Vol. 22, 2020, id. 100779.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2019.100779Search in Google Scholar

[40] Diamantopoulos, G., M. Katsiotis, M. Fardis, I. Karatasios, S. Alhassan, M. Karagianni, et al. The role of titanium dioxide on the hydration of Portland cement: A combined NMR and ultrasonic study. Molecules, Vol. 25, No. 22, 2020, id. 5364.10.3390/molecules25225364Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] JTG3420-2020. Testing methods of cement and concrete for highway engineering, Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China, Beijing, China, 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ren, J., Z. Zhao, Y. Xu, S. Wang, H. Chen, J. Huang, et al. High-fluidization, early strength cement grouting material enhanced by nano-SiO2: formula and mechanisms. Materials (Basel), Vol. 14, No. 20, 2021, id. 6144.10.3390/ma14206144Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Zhao, Z., J. Chen, J. Wang, S. Zhuang, H. Chen, H. Zhao, et al. Effect mechanisms of toner and nano-SiO2 on early strength of cement grouting materials for repair of reinforced concrete. Buildings, Vol. 12, No. 9, 2022, id. 1320.10.3390/buildings12091320Search in Google Scholar

[44] JC/T313-2009. Test method for determining expansive ratio of expansive cement, China Architecture and Building Press, Beijing, China, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Ponomar, V., J. Yliniemi, E. Adesanya, K. Ohenoja, and M. Illikainen. An overview of the utilisation of Fe-rich residues in alkali-activated binders: Mechanical properties and state of iron. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 330, 2022, id. 129900.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129900Search in Google Scholar

[46] Jin, F., K. Gu, and A. Al-Tabbaa. Strength and drying shrinkage of reactive MgO modified alkali-activated slag paste. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 51, 2014, pp. 395–404.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.10.081Search in Google Scholar

[47] Yong-ping, A. I. and S. K. Xie. Hydration mechanism of gypsum–slag gel materials. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2020, id. 04019326.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002974Search in Google Scholar

[48] Wan, D., W. Zhang, Y. Tao, Z. Wan, F. Wang, S. Hu, et al. The impact of Fe dosage on the ettringite formation during high ferrite cement hydration. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 104, No. 7, 2021, pp. 3652–3664.10.1111/jace.17640Search in Google Scholar

[49] Peys, A., C. E. White, H. Rahier, B. Blanpain, and Y. Pontikes. Alkali-activation of CaO-FeOX-SiO2 slag: Formation mechanism from in-situ X-ray total scattering. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 122, 2019, pp. 179–188.10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.04.019Search in Google Scholar

[50] Wang, S., S. Yang, C. Gong, L. Lu, and X. Cheng. Constituent phases and mechanical properties of iron oxide-additioned phosphoaluminate cement. Materiales de Construccion, Vol. 65, No. 318, 2015, id. 59467994.10.3989/mc.2015.02214Search in Google Scholar

[51] Nied, D., K. Enemark-Rasmussen, E. L’Hopital, J. Skibsted, and B. Lothenbach. Properties of magnesium silicate hydrates (M-S-H). Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 79, 2016, pp. 323–332.10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.10.003Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sonat, C., N. T. Dung, and C. Unluer. Performance and microstructural development of MgO–SiO2 binders under different curing conditions. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 154, 2017, pp. 945–955.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.020Search in Google Scholar

[53] Nazari, A. and S. Riahi. The effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on physical, thermal and mechanical properties of concrete using ground granulated blast furnace slag as binder. Materials Science and Engineering: A, Vol. 528, No. 4–5, 2011, pp. 2085–2092.10.1016/j.msea.2010.11.070Search in Google Scholar

[54] Ren, J., Y. Lai, and J. Gao. Exploring the influence of SiO2 and TiO2 nanoparticles on the mechanical properties of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 175, 2018, pp. 277–285.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.181Search in Google Scholar

[55] Maiti, M., M. Sarkar, S. Maiti, M. A. Malik, and S. Xu. Modification of geopolymer with size controlled TiO2 nanoparticle for enhanced durability and catalytic dye degradation under UV light. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 255, 2020, id. 120183.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120183Search in Google Scholar

[56] Brew, D. R. M. and F. P. Glasser. Synthesis and characterisation of magnesium silicate hydrate gels. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2005, pp. 85–98.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.06.022Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete