Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

-

Vishal Thakur

, Sunpreet Singh

Abstract

3D printing is one of the plastic recycling processes that deliver a mechanically sustainable product and may be used for 4D printing applications, such as self-assembly, sensors, actuators, and other engineering applications. The success and implementation of 4D printing are dependent on the tendency of the shape memory with the action of external stimuli, such as heat, force, fields, light, and pH. Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and polylactic acid (PLA) are the most common materials for fused filament fabrication-based 3D printing processes. However, the low-shaped memory tendency on heating and weaker and less rigidity of ABS limit the application domains. PLA is an excellent responsive behavior when the action of heat has high stiffness. The incorporation of PLA into ABS is one of the solutions to tune the shape memory effect for better applicability in the 4D printing domain. In this study, the primary recycled PLA was incorporated into the primary recycled ABS matrix from 5 to 40% (weight%), and composites were made by extrusion in the form of cylindrical filaments for 4D printing. The tensile and shape memory properties of the recycled ABS–PLA composites were investigated to select the best combination. The results of the study were supported by fracture analysis by shape memory analysis, scanning electron microscopy, and optical microscopy. This study revealed that the prepared ABS–PLA-based composites have the potential to be applied in self-assembly applications.

1 Introduction

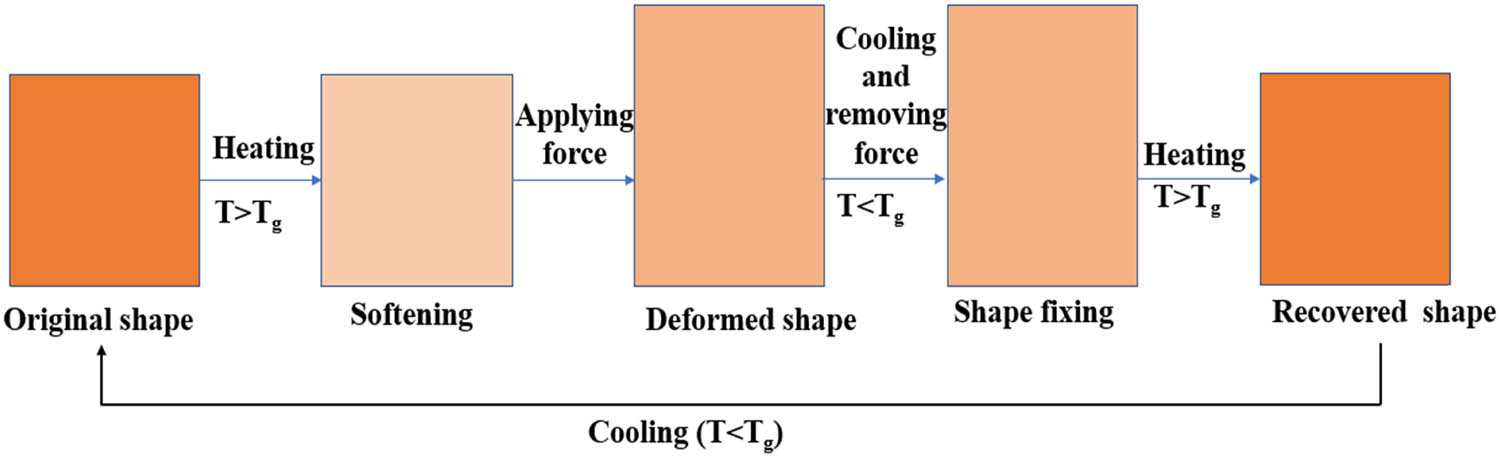

The need to manufacture sustainable products (with recycled materials) is the need of the hour. 4D printing has emerged as one of the well-established tools that fulfill the manufacturing of these products that have high sustainability and engineering acceptability. 4D printing has emerged as one of the important processes for morphing abilities of shape and size in healthcare, self-assembly, sensors, biomimetic implants, and aerospace and consumer industries. The shape memory ability of materials is one of the most important parameters for 4D printing applications. Various additive manufacturing (AM) processes are being used for 4D printing in functional uses [1]. AM comprises the process in which the part is fabricated by layer-by-layer addition of materials in various fashions, such as the extrusion process, binding of material, melting, and photo-polymerization [2]. The materials that can be used in 3D printing are metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites. Various technologies of AM are used for making parts or structures or products, including fused deposition modeling (FDM), binder jetting, photo-material jetting, stereolithography (SLA), powder bed fusion, direct energy deposition, and laser-assisted printing [3]. Polymers are used in AM techniques because of the lightweight, corrosion-resistant, good thermal, mechanical, and biocompatible properties of their printed parts [4]. Some polymers respond to external factors or stimuli such as moisture, heat, electric field, magnetic field, and pH. These responsive polymers, which show the shape memory behavior under external stimuli over time, can be used to print parts, and the process is known as “4D printing.” These external stimuli or environmental stimuli induced the changes in the size, shape, conductivity, and surface characteristics used in various medical and engineering applications [4,5]. The phase transformation of the shape memory polymer (SMP) is normally above the glass transition temperature, and the density of the SMP ranges between 0.9 and 1.25 g·cm−3. Most of the SMPs are biodegradable and biocompatible, the strain percentage is up to 800%, and the recovery speed to the original shape after deformation is several minutes; these SMPs are also cost-efficient [6]. These SMPs show the shape memory effect (SME). SME is the proficiency of polymer or the material to regain or restore the original position even after the deformation by any external stimuli. Shape recovery is defined by the comparison between the initial and final dimensions before and after exposure to the stimulus (temperature (T) > glass transition temperature (T g)). In general, as shown in Figure 1, the SME is the comparison of the dimension between the original shape and the recovered shape. The technique that is mostly used for the manufacturing of 3D structures is FDM. This technique is cost-efficient, easy to process, easy to fabricate, and also provides less material wastage.

Mechanism of SME in polymers.

The materials that are used mostly in FDM techniques are polylactic acid (PLA) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). ABS is an amorphous polymer and has high impact resistance and better toughness. The melting of ABS is between 200 and 250°C (not the true melting point, but it has a melting range). This material is used in the automotive, healthcare, and aerospace industries to manufacture a few components. Another material, PLA, is biodegradable and also responds to moisture above 60°C [7]. Polymers have unique characteristics and less modulus and strength. Therefore, the use of polymers is increasing for making products, and some challenges exist. Therefore, to eliminate these polymeric system challenges, the reinforcement of secondary materials, which may be metallic, fiber, or nanoparticles, is added to these polymers to obtain polymer matrix composite (PMC). These PMCs help to enhance the properties of the polymer and have been used for engineering applications [8]. PLA materials have high stiffness, so they cannot be extended by more than 10% without breaks. The polymers have good SMEs, but when they are mixed with other materials, a composite is formed, and the SME increases mostly. The biocompatibility of a PLA material can be increased by the addition of hydroxyapatite (HAp) to it. The HAp powder of 4–8 wt% to PLA granules is mixed and makes a filament with the help of a twin-screw extruder. As a result, it is found that the recovery rate is between 72 and 96% for temperatures between 60 and 70°C [9]. The annealing process was done at 75°C for the 3D printed part manufactured from the PLA material, which helps to increase the tensile and compressive strength. The annealing process shows its effect on the mechanical properties of the printed 3D part [10]. The PLA-based composites have been continuously used as 4D printing materials in different areas of applications such as controllable sequential deformation [11], smart textiles [12], electrically controlled local deformation [13], sustainable plastics for agriculture [14], origami structures for functional scaffolds [15], and actuators [16]. The aim of mixing PLA into ABS is to induce superior properties in each of them. For example, Jo et al. have reported the effect of compatibilizer on the mechanical properties [17]. The ABS–PLA-based materials have been reported for geospatial imaging [18]. Previous studies have reported the mixing of PLA and ABS thermoplastic composite matrix and investigated the mechanical, chemical, thermal, and morphological properties from various application perspectives [19,20,21,22,23,24]. PLA is a biocompatible polymer and also shows promising shape memory behavior [25], so the mixing of ABS and PLA may be used to program the SME, mechanical properties, thermal properties, deformation behavior, etc.

The literature survey revealed that PLA is one of the most used thermoresponsive materials in different applications (actuator, biomimetic tissue engineering, and smart textiles) by 4D printing. ABS is also one of the most used materials in fused filament fabrication (FFF)-based 3D printing processes. Most of the previous studies have investigated the mechanical, thermal, chemical, and morphological properties of the ABS–PLA composites. However, very few studies have been reported for the ABS–PLA combination as the thermoresponsive materials to be used by 4D printing in self-assembly applications. In this study, the incorporation of PLA by weight proportion (5 to 40%) in the ABS matrix was done, and the cylindrical filaments were fabricated by the extrusion process for 4D printing. The investigation of mechanical properties and shape memory properties was conducted for recycled ABS–PLA composites.

2 Materials and methods

The pellets of primary recycled ABS (size: 1.5–2.0 mm) and PLA (size: 2.0 ± 0.10 mm) (Supplier: Batra Polymers Pvt. Ltd, Ludhiana, India) have been used in this study for the preparation of the ABS–PLA composites in the form of cylindrical feedstock filaments. ABS and PLA are the most common materials used in the FDM processes for the manufacturing of customized structures [26,27,28]. Table 1 shows the details of the properties of ABS and PLA.

| Properties | ABS | PLA |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.01–1.20 g·cc−1 | 1.00–2.47 g·cm−3 |

| Ultimate tensile strength | 22.1–74.0 MPa | 46.0–49.0 MPa |

| Modulus of elasticity | 1.0–2.65 MPa | 2.96–3.60 MPa |

| Glass transition temperature | 108–109°C | 50–65°C |

| Processing temperature | 76.7–240°C | 30–300°C |

| MFI | 0.100–35.0 g/10 min | 0.200–92.8 g/10 min |

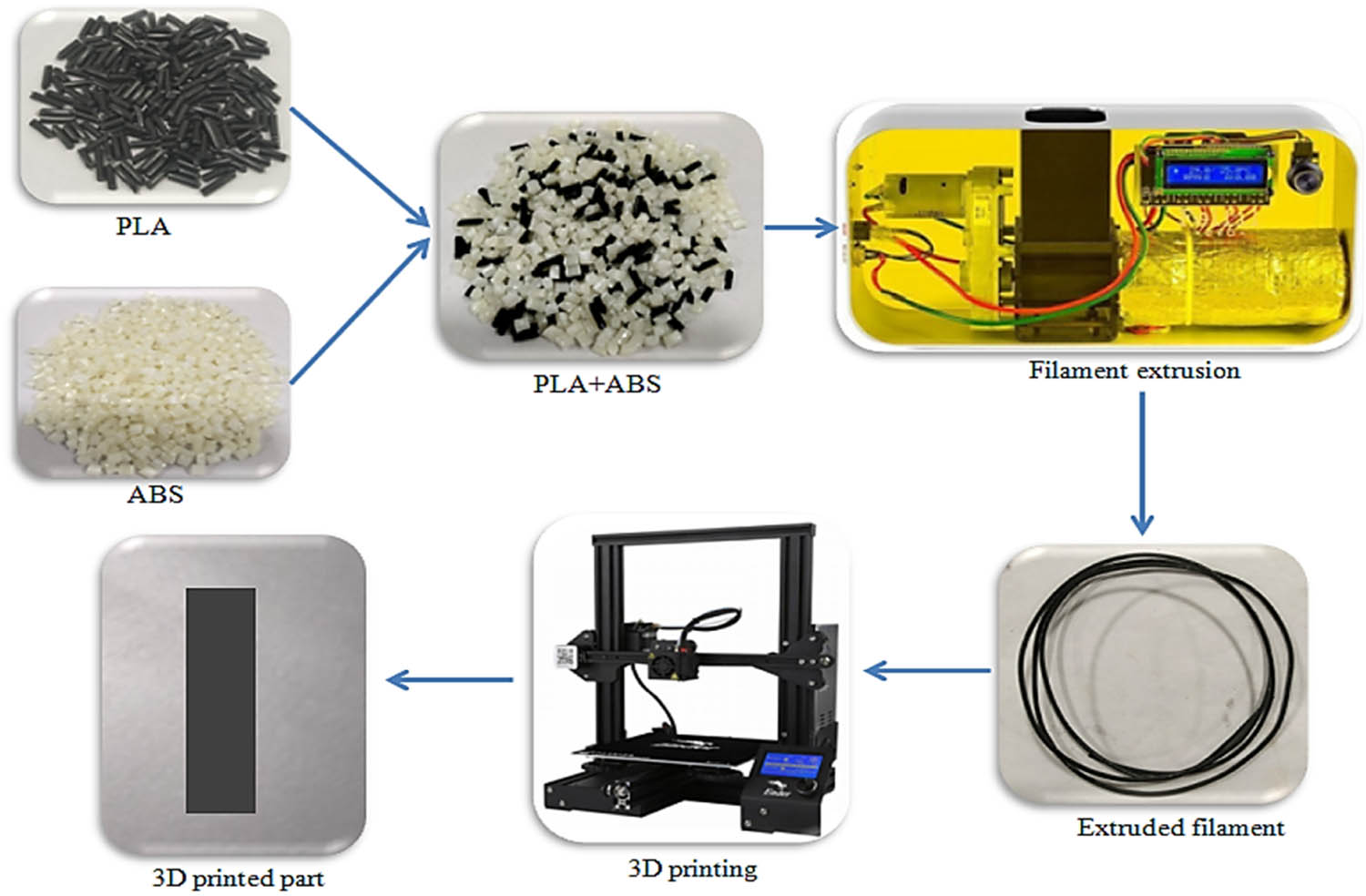

Figure 2 shows the process methodology for the in-house development of ABS–PLA-based composite structures in 4D printing applications. In the first stage, the melt flow index (MFI) of the primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40% weight% PLA was used) composite materials were determined to check the flowability.

Step-by-step procedure for the development of thermoresponsive ABS–PLA composite feedstock filaments.

In the next stage, strategies have been formulated for the in-house development of the ABS–PLA composite materials using a single-screw extruder setup. After ensuring the tensile properties and fracture mechanism of the feedstock filaments, the FFF-based 3D printing was performed by investigating the shape memory tendency of ABS–PLA composites.

3 Experimentation

Experimentation was conducted by a series of MFI investigations, followed by filament extrusion, fracture subjected to tensile loading, fracture analysis by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), composition analysis by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), surface roughness analysis, and shape memory analysis.

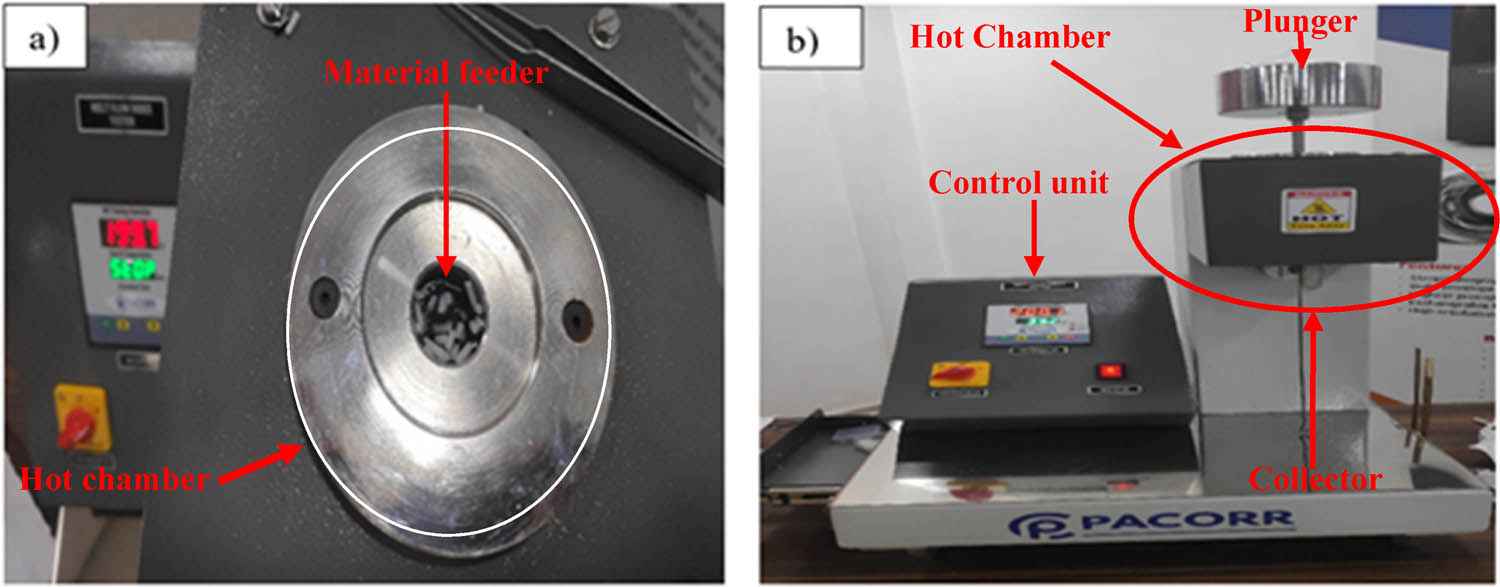

3.1 MFI

MFI is one of the rheological properties that depict the fitness of the material to be used in the FFF-based 3D printing process. An MFI is a device or equipment that is used to measure the MFI. In the evaluation process of MFI, there is a weight applied to force the material to extrude through the die. According to ASTM standards D1238, the weight specified for the primary recycled ABS material is 5 kg at 200°C applied to a plunger, and the molten material is forced through the die. A timed extrudate (i.e., for 10 min) is collected and weighed. The SI units for MFI are g/10 min. Figure 3 shows the MFI setup and process.

(a) Sample placed in the barrel of MFI and (b) filament extruded through die.

3.2 Filament extrusion

The filaments were extruded in the form of 1.75 ± 0.1 mm cylindrical feedstock on a single-screw extruder setup (Felfil, maximum temperature: 300°C). The experimentation involves the control of screw rotation at 6 RPM (suggested by the manufacturer for ABS) and at a barrel temperature of 200°C. Before the extrusion process, the granules of primary recycled ABS and primary recycled PLA were dried in the hot air oven at 60°C for 1 h, and then extrusion was processed. The composition of the primary recycled PLA in primary recycled ABS varied from 5 to 40% (by weight %).

3.3 Tensile testing

Next to filament extrusion, the extruded material combination of ABS, PLA, and ABS–PLA composites was cut into 150 mm lengths and further subjected to tensile loading. A universal testing machine (Shanta Engineering, maximum capacity: 5,000 N) was used for the tensile testing of the prepared feedstock filaments at a strain rate of 20 mm·min−1. It should be noted that the diameter of every sample was measured (repeated five times), and the mean values were used in the calculation. For the tensile testing of the feedstock filaments, there is no availability of set standards, so the ASTM D638 procedure was followed for the feedstock filament tensile testing. Before the tensile testing, the samples of feedstock filament were cut into the required length mechanically. After testing, SEM was performed further for fracture analysis of the fractured filaments.

3.4 Photomicrography

For the investigation of the morphology of fractured feedstock filaments, SEM (JEOL, JSM IT500) analysis was performed. For the investigations of the fractures, the power supply was maintained at 15 kV on a high vacuum mode. The microscopic fracture analysis was performed at magnifications of 75×, 250×, and 500×. In addition, the atomic and mass fractions of the atoms present were determined using the EDS software add-on. Optical microscopy (Nikon) was performed for fracture analysis at 50× magnification.

3.5 3D printing

The FFF-based 3D printer (Creality; Model: Ender 3 pro) was used to prepare the parts of primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA (which have better tensile strength) composites for the investigation of the SME. The 3D printing process was performed considering a layer thickness of 0.12 mm, a nozzle temperature for primary recycled PLA of 210°C, temperature for primary recycled ABS and ABS–PLA substrate (based upon the printability) of 230°C, bed temperature for the primary recycled PLA of 60°C, and temperature for primary recycled ABS and ABS–PLA of 80°C, a linear fill pattern, 80% infill, and a printing speed of 60 mm·s−1. For the SME analysis, 3D printing was performed to prepare the structure in 40 mm × 10 mm × 1 mm size. Then, the slicing of that model was done using the slicing software Ultimaker Cura software package (Version 4.5).

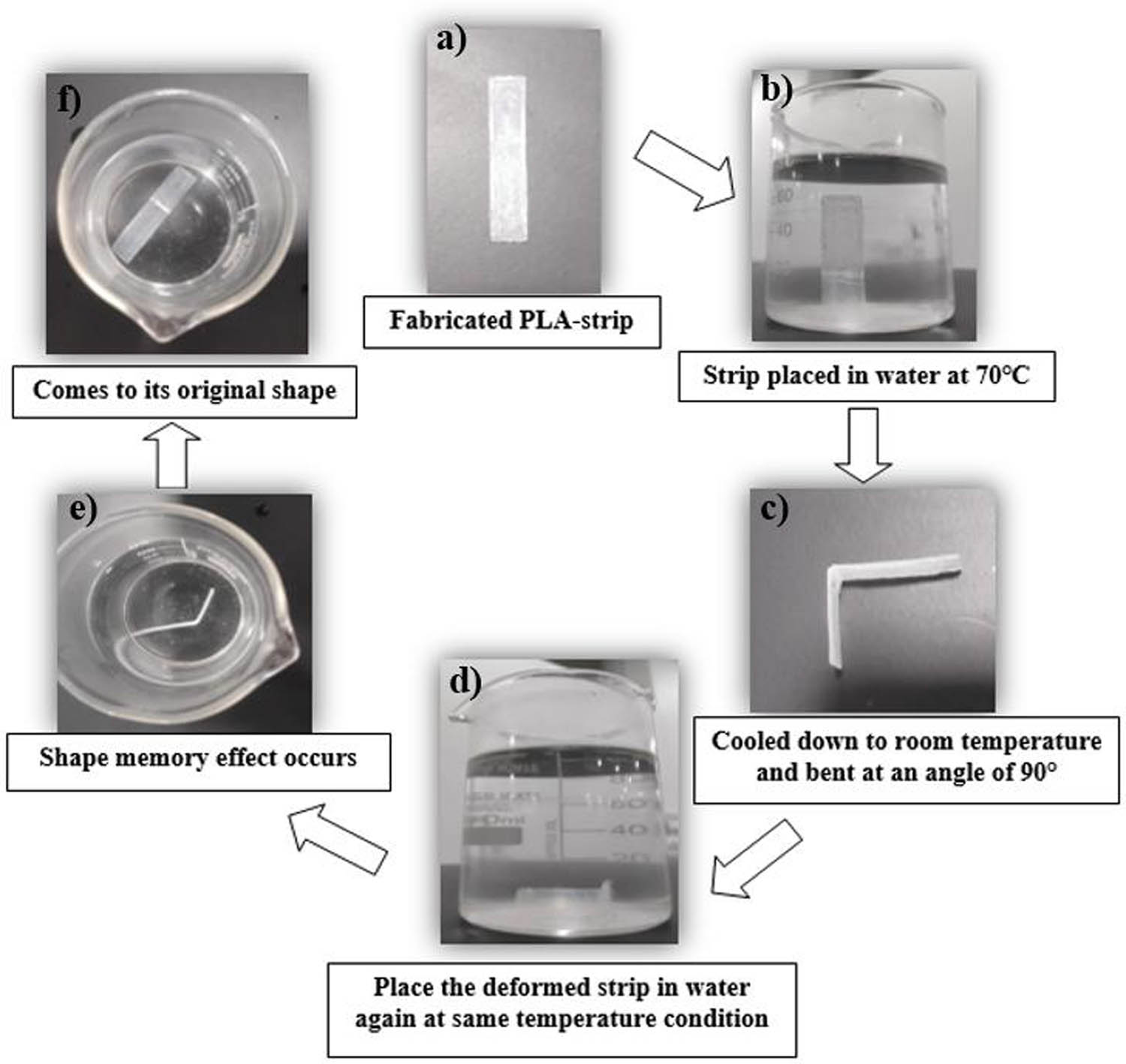

3.6 Shape memory evaluation

These SMPs have high elastic deformation, as well as, in some cases, biocompatible, biodegradable, and cost-efficient. Therefore, the experiments were performed to check the SME of the part (flat strip), which was fabricated with the FFF technique, and the feedstock filament, which was manufactured by an extruder and used as a material. These SMPs can remember their original shape and come to their original shape even after deformation. Therefore, two terms exist: one is shape fixing, and another is shaped recovery ratio (RR). Shape fixing is defined as the level of deformation that may be fixed upon rapid cooling. Shape fixing can be calculated as shown in Eq. (1):

The shape RR is the level of deformation that is recovered upon heating and is calculated as shown in Eq. (2):

where

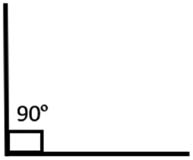

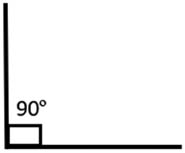

The SME was investigated using a step-by-step procedure, as shown in Figure 4. After the fabrication of the flat strip, it was soaked in a beaker filled with water. The beaker was then placed in an oven at 70°C for 1 h. Subsequently, heating was enabled, and the part became flexible to some extent.

(a) Fabricated model of the flat strip. (b) Strip placed in a beaker of water at 70°C. (c) Cooled to room temperature and bent at an angle of 90°. (d) Placed in a beaker, and the temperature was increased to 70°C. (e) Occurrence of SME. (f) Retains its original position.

Next, the flat strip was subjected to hot air oven bending, which was performed at an angle of 90° followed by cooling at room temperature. After approximately 15 min, the flat strip was cooled and fixed at a 90° bending angle. Next, it was placed in a beaker of water and kept in an oven at 70°C for 1 h. In the final stage, the measurement of the angle was compared with the initial shape and size to calculate the SME.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 MFI analysis

Table 2 shows the MFI value of the primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA composite. The experimentation was repeated three times for each composition to minimize the experimental errors, and the mean values of the three experiments are shown in Table 2. The MFI was observed at 11.85 and 45.0 g/10 min for primary recycled ABS and primary recycled PLA, respectively. The higher MFI for the primary recycled PLA shows that the PLA has a high tendency to flow through the FFF nozzle, which indicates that 3D printing may be done at a higher printing speed. Also, the addition of the PLA to the ABS matrix would significantly affect the MFI of the primary recycled ABS. The results suggest that increasing the amount of PLA in the ABS matrix leads to an increase in the MFI of the ABS–PLA composite matrix. Thus, the addition of the PLA in the ABS matrix increased the acceptability of the composite feedstock filaments. The MFI of ABS-40% PLA (31.48 g·min−1) was highest among composites.

MFI of primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA composites

| Sr. no. | Composition | ABS material (by wt%) | PLA material (by wt%) | MFI (g/10 min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Primary recycled ABS | 100 | 0.0 | 11.85 ± 0.2 |

| 2. | Primary recycled PLA | 0.0 | 100 | 45.0 ± 2.0 |

| 3. | ABS–5% PLA | 95 | 5 | 9.27 ± 0.2 |

| 4. | ABS–10% PLA | 90 | 10 | 10.60 ± 0.3 |

| 5. | ABS–15% PLA | 85 | 15 | 15.00 ± 0.4 |

| 6. | ABS–20% PLA | 80 | 20 | 15.60 ± 0.4 |

| 7. | ABS–25% PLA | 75 | 25 | 20.68 ± 0.5 |

| 8. | ABS–30% PLA | 70 | 30 | 21.47 ± 0.6 |

| 9. | ABS–35% PLA | 65 | 35 | 24.34 ± 0.9 |

| 10. | ABS-40% PLA | 60 | 40 | 31.48 ± 1.2 |

4.2 Tensile test results

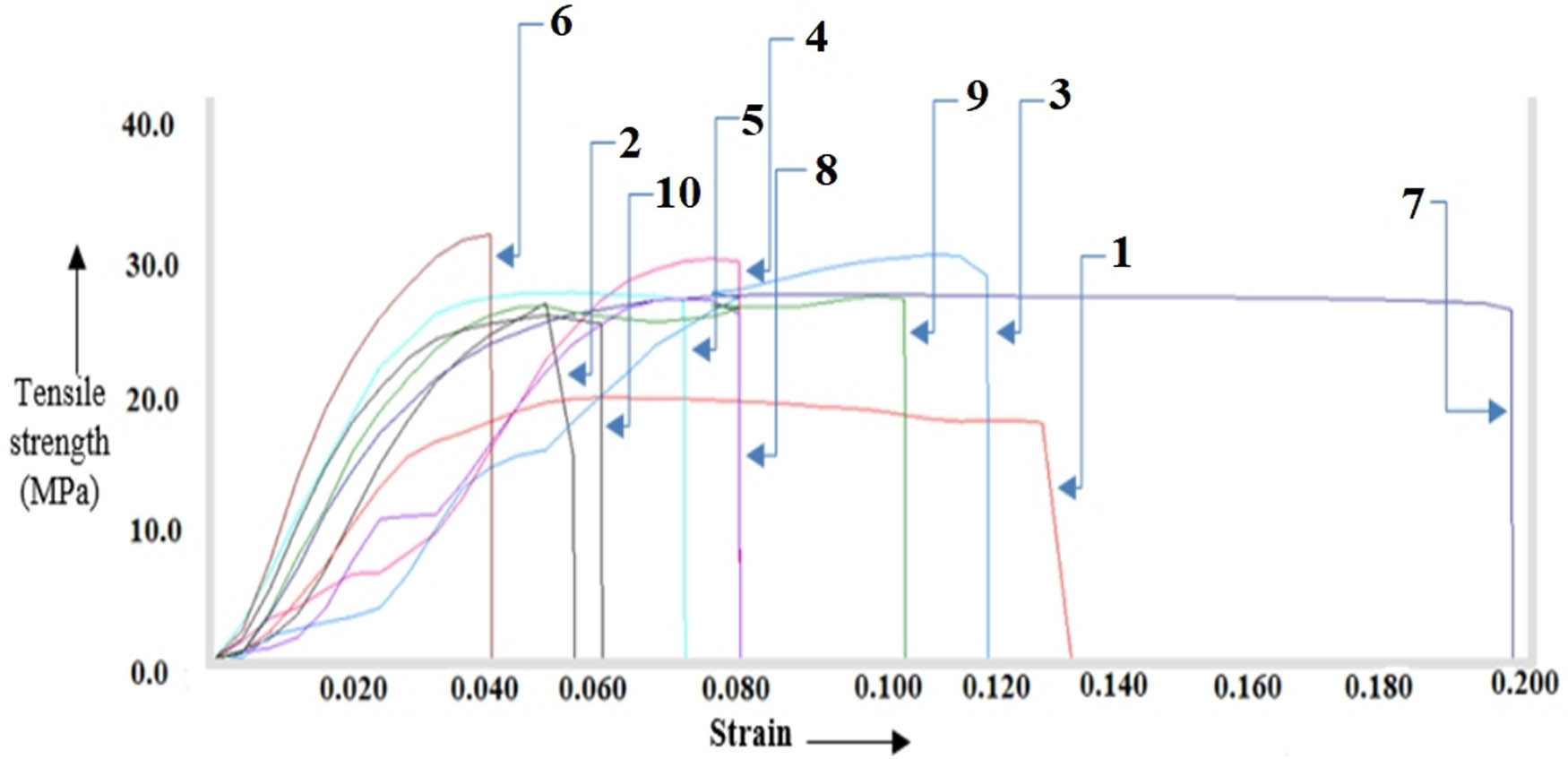

The tensile testing resulted in tensile strength (ultimate and fracture tensile strength) and percentage elongation (at peak and break), as shown in Table 3. The ultimate tensile strength of the primary recycled ABS and primary recycled PLA was 19.49 and 26.58 MPa, respectively. Although the tensile strength of the primary recycled PLA was higher than that of the primary recycled ABS, the percentage of elongation was lower. The percentage elongation of ABS was 13%, which is greater than the percentage elongation of PLA (5%). The results have confirmed that PLA has higher stiffness than ABS. More interesting outcomes of mixing PLA and ABS were observed, as combining the tensile strength and percentage elongation of ABS–PLA was higher than either primary recycled ABS or primary recycled PLA alone. In the case of PLA loading of 20%, the maximum tensile strength (31.47 MPa) of ABS–PLA composites was observed. However, the percentage elongation of ABS-20% PLA was minimal, even lower than that of PLA. This may be because the blending of ABS and PLA was very compact, and the linkages between the polymeric matrices were unable to be established. Leading to this observation, the above loading of 20% PLA in ABS, the tensile strength started decreasing as the reinforcement of PLA was increased. This trend in the reduction of tensile strength was followed by a 40% loading of PLA in ABS. In the case of 25% loading of PLA in ABS (ABS–25% PLA), the percentage of elongation was observed to be the highest among all, even greater than ABS alone. This may be because 25% of the loading of PLA was unable to disturb the matrix of ABS, so the percentage of elongation resulted in the highest percentage in the case of ABS–25% PLA.

Tensile properties of recycled primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA composites

| Sr. no. | Filament | Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | Fracture tensile strength (MPa) | Percentage elongation at peak (%) | Percentage elongation at break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Primary recycled ABS | 19.49 ± 0.34 | 17.54 ± 0.32 | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 13.0 ± 0.0 |

| 2 | Primary recycled PLA | 26.58 ± 0.68 | 23.92 ± 0.65 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| 3. | ABS–5% PLA | 29.98 ± 0.58 | 26.98 ± 0.53 | 11.0 ± 1.0 | 12.0 ± 0.0 |

| 4. | ABS–10% PLA | 29.78 ± 0.62 | 26.8 ± 0.58 | 8.0 ± 0.0 | 8.0 ± 0.0 |

| 5. | ABS–15% PLA | 27.17 ± 0.51 | 24.45 ± 0.48 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 7.0 ± 0.0 |

| 6. | ABS–20% PLA | 31.47 ± 0.41 | 28.32 ± 0.40 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | 4.0 ± 0.0 |

| 7. | ABS–25% PLA | 27.07 ± 0.58 | 24.36 ± 0.51 | 10.0 ± 0.0 | 20.0 ± 1.0 |

| 8. | ABS–30% PLA | 26.78 ± 0.84 | 24.1 ± 0.76 | 7.0 ± 0.0 | 8.0 ± 0.0 |

| 9. | ABS–35% PLA | 26.88 ± 0.62 | 24.2 ± 0.54 | 10.0 ± 0.0 | 11.0 ± 0.0 |

| 10. | ABS–40% PLA | 25.58 ± 0.54 | 23.02 ± 0.49 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 0.0 |

The modulus of toughness is one of the most important considerations when the manufactured parts are applied in an application where crash loading is involved. The higher modulus of toughness indicates the high resistivity of the manufactured parts against crash loading. Modulus of toughness results from the stress in correspondence with strain produced by the parts during tensile loading. Table 4 shows the modulus of toughness and elastic modulus of primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS–PLA composites. Although the elastic modulus of the ABS–20% PLA is maximum (786.75 MPa), at the same time, the strain is minimum in sample 6. Consequently, sample 6 cannot be used in the application where crash loading is required. Also, the strain is maximum for sample 7, but the elastic modulus for this sample is very low. Therefore, where crash loading is required, sample 7 can be used.

Modulus of toughness and elastic modulus of primary recycled ABS, primarily recycled PLA, and ABS-PLA composites

| Sr. no. | Filament | Modulus of toughness (MPa) | Elastic modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Primary recycled ABS | 1.26 | 324.83 |

| 2 | Primary recycled PLA | 0.66 | 531.60 |

| 3. | ABS–5% PLA | 1.79 | 272.54 |

| 4. | ABS–10% PLA | 1.20 | 372.25 |

| 5. | ABS–15% PLA | 0.95 | 543.40 |

| 6. | ABS–20% PLA | 0.63 | 786.75 |

| 7. | ABS–25% PLA | 2.70 | 270.70 |

| 8. | ABS–30% PLA | 1.07 | 382.57 |

| 9. | ABS–35% PLA | 1.47 | 268.80 |

| 10. | ABS–40% PLA | 0.76 | 511.60 |

Figure 5 shows the stress vs strain graph of the feedstock filaments for fractured composites under tensile load. The curves depict that ABS–20% PLA possessed maximum tensile strength, whereas ABS–25% PLA possessed maximum elongation.

Stress vs strain curves for the fractured composites.

The experimental values in the present study were obtained in line with previous studies [32,33,34,35,36], as shown in Table 5. However, the mixing of engineered polymers, such as flax, may contribute to the maximization of the elastic modulus.

Tensile properties of ABS and PLA co-polymeric composites reported by previous studies [32,33,34,35,36]

| Sr. no. | Matrix materials | Reinforced polymers (% loading) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elastic modulus (MPa) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ABS | Polypropylene (PP) (20%) | 31.90 ± 2.00 | 857 ± 46 | [32] |

| 2 | ABS | Polycarbonate (PC) (20%) | 46 | 1,953 | [33] |

| 3 | PLA | Polyurethane (PU) (30%) | 24 ± 1.5 | 544 ± 48 | [34] |

| 4 | PLA | PU (20%) | 30 ± 2 | 816 ± 64 | [34] |

| 5 | PLA | Flax (30%) | — | 8,300 ± 600 | [35] |

| 6 | PLA | Flax (40%) | — | 7,300 ± 500 | [35] |

| 7 | PLA | ABS (70%) | — | 1,400 ± 20 | [36] |

| 8 | PLA | ABS (50%) | — | 1,320 ± 20 | [36] |

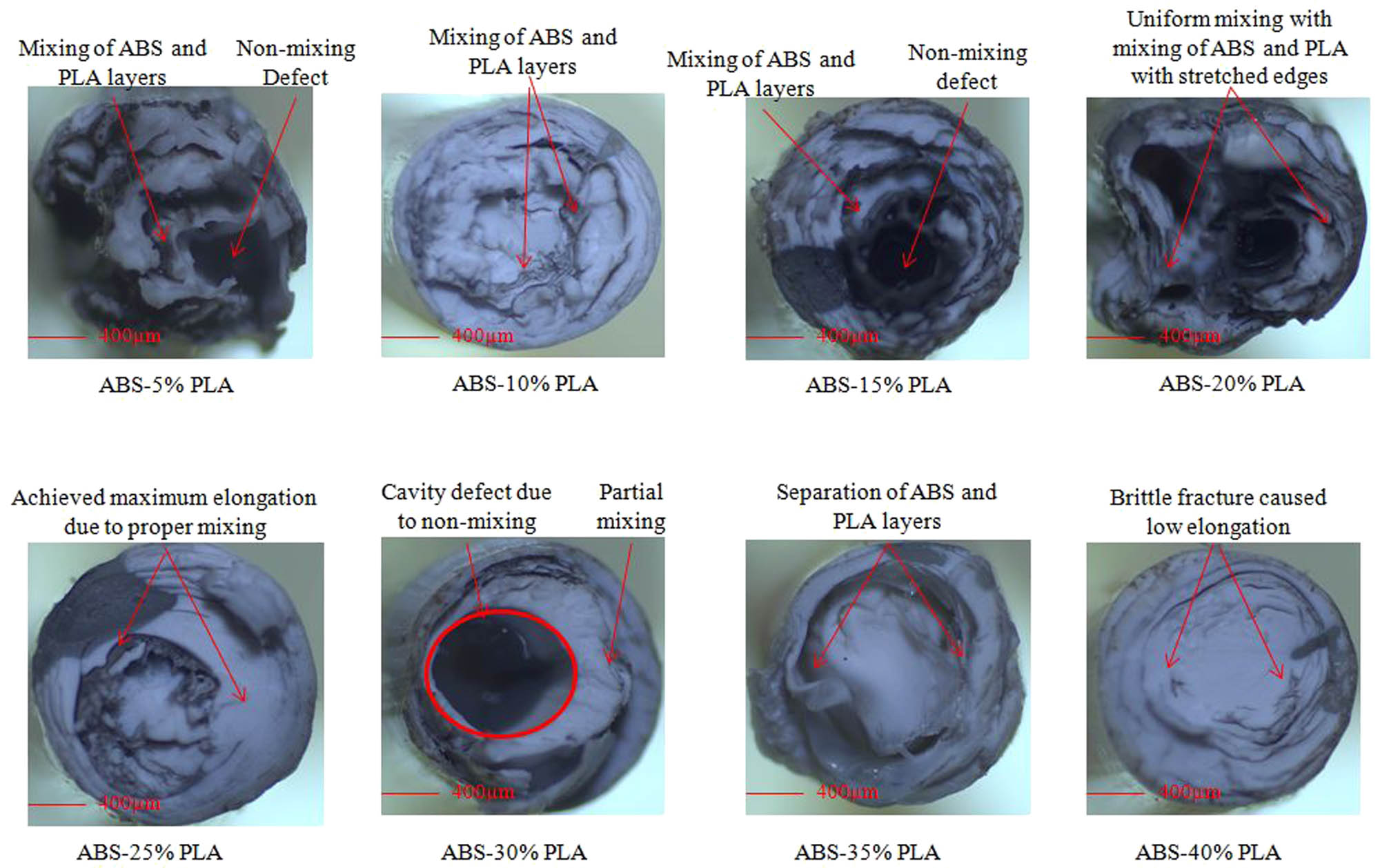

4.3 Fracture morphology

From the morphological test of the fractured filaments, various observations were made for different compositions of ABS-PLA composites (Figure 6). In ABS–5% PLA, the mixing of ABS-PLA layers was not uniform, elongation of the filament was also minimal, and there were non-mixing defects in this composition. In ABS–10% PLA, the mixing of ABS-PLA layers and elongation of filament were better than in the ABS–5% PLA composite. Subsequently, the mixing of the ABS-PLA layers was good to some extent, but the non-mixing defects occurred in ABS–15% PLA. The elongation of ABS–15% PLA was much better than that of ABS–5% PLA and ABS–10% PLA. In ABS–20% PLA, the mixing of the ABS-PLA layers was uniform with stretched edges, and also the elongation was maximum in all these samples, but the strain of ABS–20% PLA was minimal, so it cannot be used where crash loading is required. In ABS–25% PLA, the elongation was less than that in ABS–20% PLA, but the strain attained was maximum in all these samples; therefore, it can be used where crash loading is required. In ABS–30% PLA and ABS–35% PLA, the defects observed were like cavities formed due to non-mixing of the ABS-PLA layers, and somewhere these layers get separated from each other. Also, the elongation was not better than in other samples. In ABS–40% PLA, brittle fracture occurred, and the strain was also minimal.

Fracture morphological analysis of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA filaments.

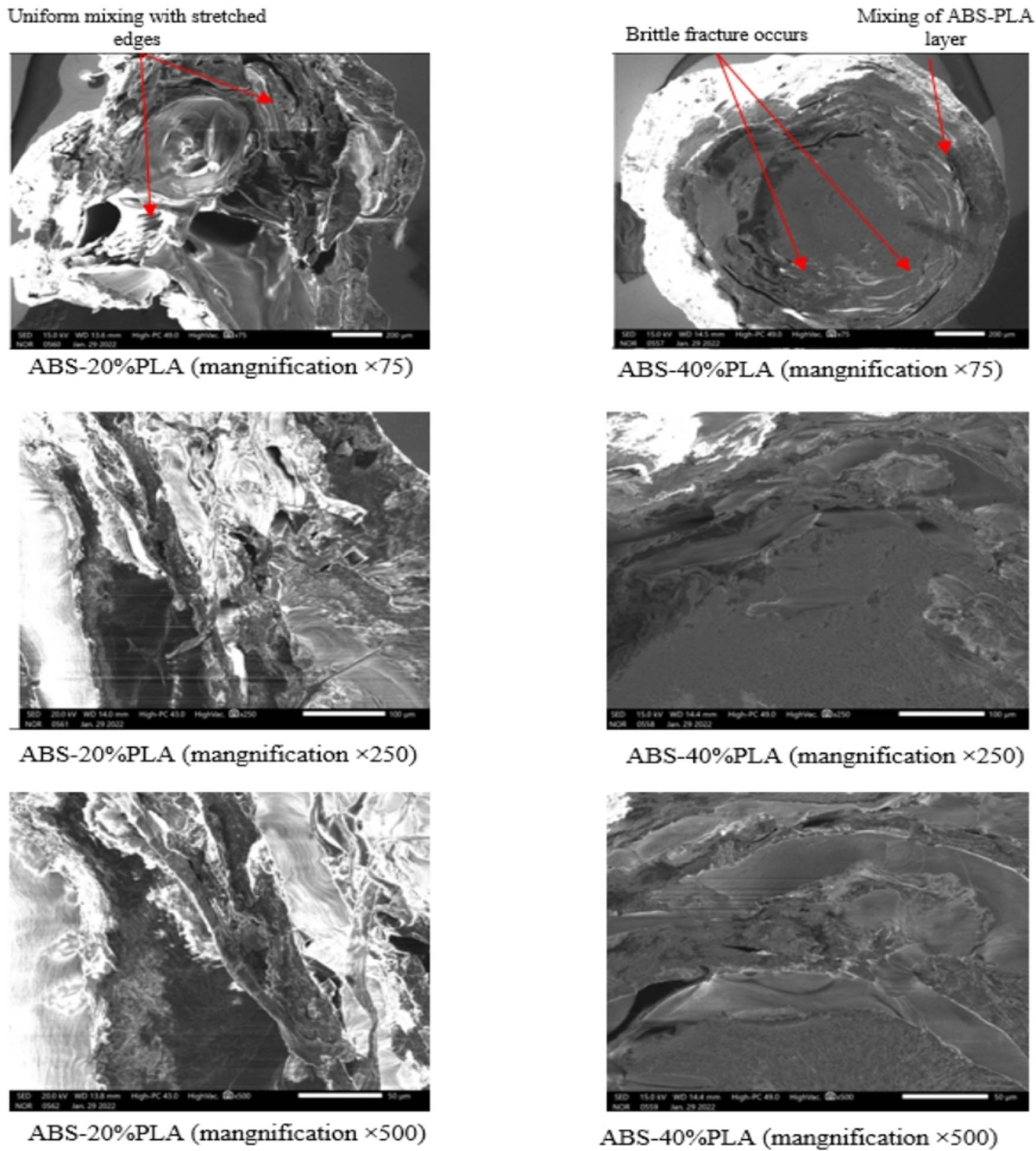

4.4 SEM analysis

Maximum and minimum tensile strengths were observed for ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA, respectively. Therefore, both combinations of materials were selected for fracture analysis using SEM and atomic fraction analysis using EDS. SEM analysis was performed after the morphological analysis of different compositions of ABS-PLA composites. From the SEM analysis, it was observed that the tensile strength in the ABS–20% PLA was better than that in all samples; however, minimum elongation was observed. Based on these results, it can be inferred that ABS–20% PLA is the most likely composition for applications that require high tensile strength.

The strain and modulus of toughness shown by ABS–20% PLA were very low, so they cannot be used in crash-loading applications. In ABS–40% PLA, the strain was better to some extent, and the mixing of the ABS-PLA layer was also better, but the brittle fracture occurred; therefore, this sample cannot be used for those applications where elongation is required. Figure 7 shows the ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA at various magnification values.

SEM analysis of samples of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA filaments.

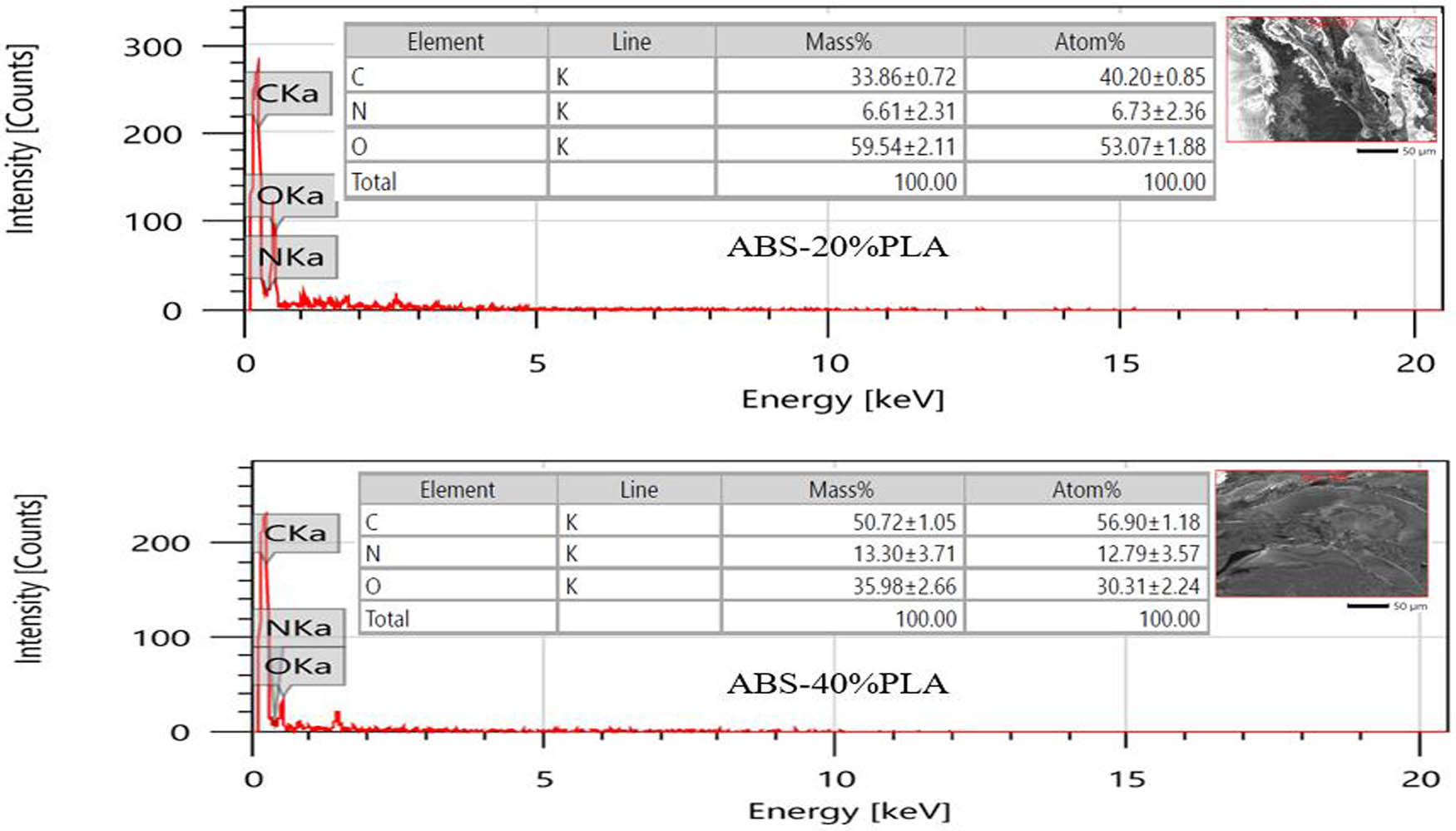

As shown in Figure 8, the carbon mass% in ABS–20% PLA is 33.68 ± 0.72, and the carbon mass% in ABS–40% PLA is 50.72 ± 1.05. In ABS–40% PLA, the brittle type of fracture that occurred may be due to more carbon content. The incorporation of carbon may lead to an increase in surface hardness as well.

EDS of samples of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA composites.

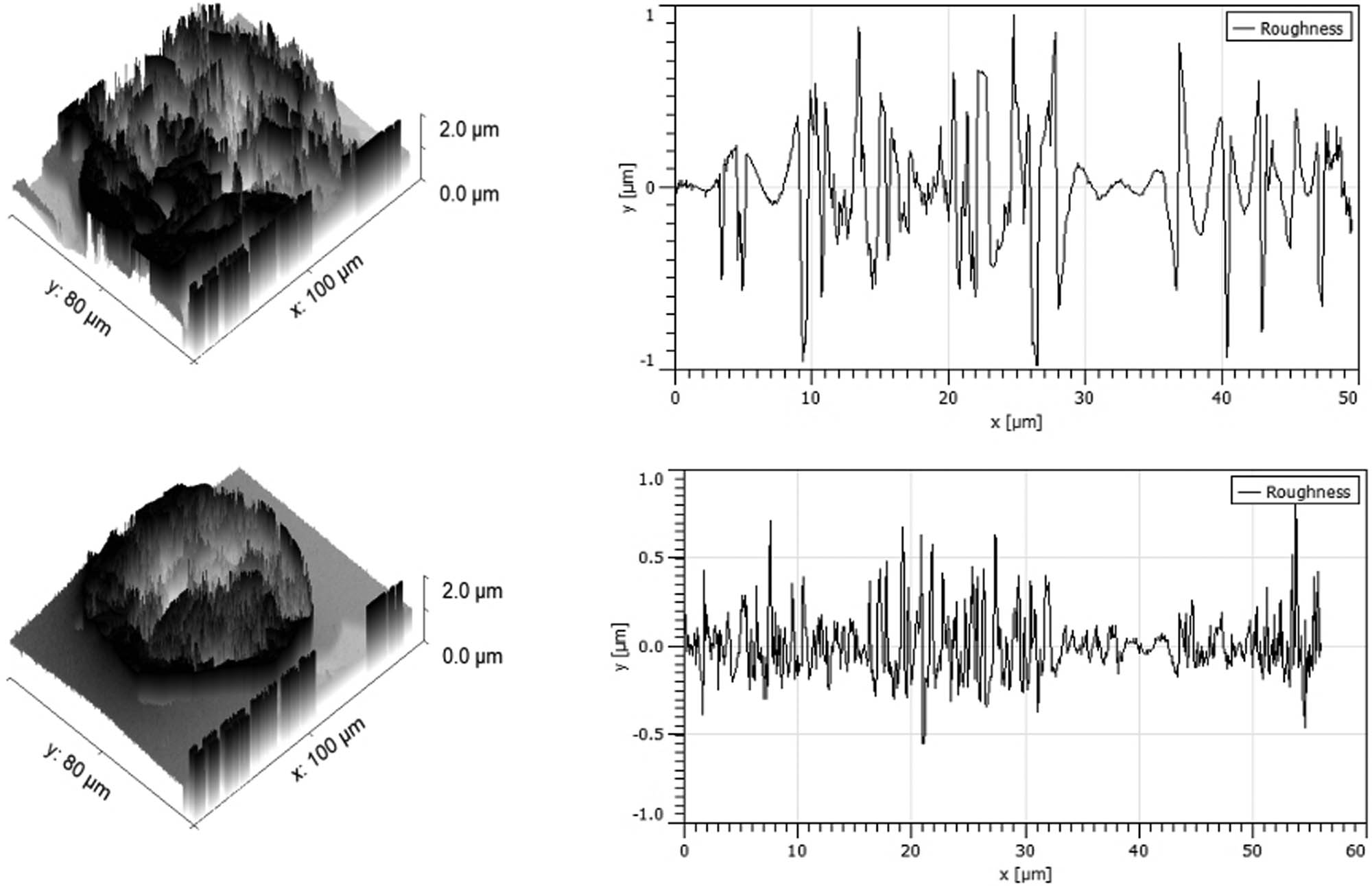

4.5 Fracture profile

The fracture images of SEM were processed using the image analysis software tool (Gwyddion 2.60) to investigate the fracture profile and average surface roughness. It should be noted that there are more pores for the fracture of ABS–20% PLA, resulting in higher surface roughness (Ra = 210.1 nm). On the other hand, the presence of lesser pores in the case of ABS–40% PLA resulted in lower surface roughness (Ra = 122.0 nm) (Figure 9). In different aspects, it may be said that higher loading of the PLA in ABS may have contributed to filling the gaps in the defected spaces, reducing surface roughness. The experimental data show better mechanical properties for recycled ABS–20% PLA composites. In previous studies, it has been reported that with an increment in the weight proportion of ABS, the mechanical properties improved [32,36]. The increment in roughness lowers the strength of composites, which directly impacts the mechanical properties [37]. The incorporation of polymers by weight proportion affects the mechanical and morphological properties, which directly change the shape memory behaviors of the polymer composites. Previous studies have reported that the incorporation of fibers and particles significantly tunes the mechanical and morphological behavior of polymers and metals [38,39]. Sustainable composites have been manufactured by blending polymer compositions to attain better mechanical properties and can be used for their prospective applications [40,41,42].

Surface profilometry of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–40% PLA.

4.6 SME analysis

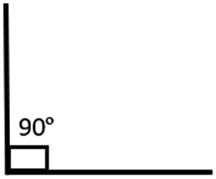

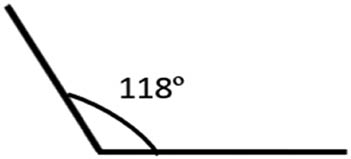

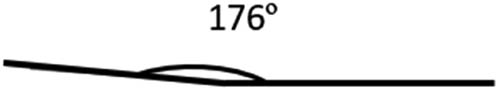

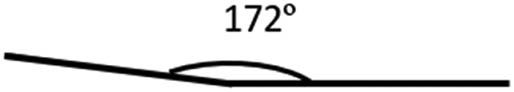

The highest tensile strength and elongation at fracture were observed in ABS–20% PLA and ABS–25% PLA, respectively. Therefore, along with the virgin ABS and virgin PLA, the SMEs of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–25% PLA 3D printed parts were also investigated (Table 6).

SMEs of ABS, PLA, and ABS–20% PLA composites under a thermal stimulus

| Materials | Initial angle | Bent angle | Angle recovered to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary recycled ABS |

|

|

|

| Primary recycled PLA |

|

|

|

| ABS–20% PLA |

|

|

|

| ABS–25% PLA |

|

|

|

It was observed that primary recycled ABS has poor SME, as it did come to its original angle (180°) in the form of a flat surface. The primary recycled ABS returned to only 118°, which is very far from the original shape (angle = 180°). The 3D-printed primary recycled PLA exhibited a good tendency to memorize its shape when the effect of the stimulus was eliminated. The primary recycled PLA recovered to 176°, which is very near to its original shape at 180°. Most importantly, part 3D printed of ABS–20% PLA also recovered to 172°, exhibiting good shape memory tendency. Also, the shape memory of ABS–25% PLA recovered to 174°, which is also very near to neat PLA. Therefore, based on these facts, it can be concluded that the combination of ABS–PLA composites has good shape memory as well as better tensile properties.

Composite materials made of polymers such as ABS and PLA have attracted significant interest in the 4D printing industry. These composites are developed by blending PLA, a biodegradable polymer made from renewable resources like corn starch or sugarcane, with ABS, a thermoplastic polymer.

The resulting ABS–PLA composite material is incredibly adaptable and has numerous potential uses in 4D printing. With the aid of an emerging technology called 4D printing, materials can gradually alter their shape or other characteristics in response to environmental factors like temperature, humidity, or light.

Self-assembling structures are produced employing ABS–PLA composites in 4D printing. These materials can be programmed to change shape or form predetermined structures in response to certain stimuli. The use of self-assembling structures to build intricate machines or devices has potential applications in fields like robotics.

The formation of smart textiles is another use of ABS–PLA composites in 4D printing. The shape or properties of these materials can be programmed to adapt to changes in humidity or temperature. This may have implications for the fashion sector, where smart textiles might be used to make clothing that changes to fit the needs or environment of the wearer.

The versatility, biodegradability, potential for self-assembly, and smart functionality of ABS–PLA composites make them promising materials for 4D printing applications overall. We will probably see several more cutting-edge applications for this fascinating technology as the 4D printing industry develops. These materials provide an exceptional set of characteristics that make them perfect for designing intricate, responsive structures that can be tailored for a variety of applications.

5 Conclusions

The followings are the conclusions of the present study:

Increasing the amount of the primary recycled PLA in the primary recycled ABS matrix leads to an increase in the MFI of the ABS–PLA composite matrix. Thus, the addition of PLA to the ABS matrix increased the acceptability of the composite feedstock filaments. The MFI of ABS–40% PLA (31.48 g·min−1) was highest among composites.

The above loading of 20% (by weight %) of primary recycled PLA in ABS decreased the tensile strength as reinforcement of PLA increased. This trend in the reduction of tensile strength was followed by a 40% loading of PLA in ABS. In the case of 25% loading of PLA in ABS (ABS–25% PLA), the percentage elongation was the highest among all. The results of the tensile properties were obtained in line and comparable with the tensile properties reported in previous studies.

Most importantly, SMEs of ABS–20% PLA and ABS–25% PLA were almost similar to those of primary recycled PLA. However, the elongation properties of ABS–25% PLA were better than primary recycled ABS, so that it may be useful for extended 4D printing applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through a large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/260/45.

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University for funding this work through a large group Research Project under grant number RGP2/260/45.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Wong, K. V. and A. Hernandez. A review of additive manufacturing. International Scholarly Research Notices, Vol. 2012, 2012, id. 208760.Search in Google Scholar

[2] de Leon, A. C., Q. Chen, N. B. Palaganas, J. O. Palaganas, J. Manapat, and R. C. Advincula. High-performance polymer nanocomposites for additive manufacturing applications. Reactive and Functional Polymers, Vol. 103, 2016, pp. 141–155.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jasiuk, I., D. W. Abueidda, C. Kozuch, S. Pang, F. Y. Su, and J. McKittrick. An overview on additive manufacturing of polymers. JOM, Vol. 703, 2018, pp. 275–283.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Tan, L. J., W. Zhu, and K. Zhou. Recent progress on polymer materials for additive manufacturing. Advanced Functional Materials, Vol. 30, 2020, id. 2003062.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Falahati, M., P. Ahmadvand, S. Safaee, Y. C. Chang, Z. Lyu, R. Chen, et al. Smart polymers and nanocomposites for 3D and 4D printing. Materials Today, Vol. 40, 2020, pp. 215–245.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Subash, A. and B. Kandasubramanian. 4D printing of shape memory polymers. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 134, 2020, id. 109771.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Dey, A., I. N. Roan Eagle, and N. Yodo. A review on filament materials for fused filament fabrication. Journal of manufacturing and materials processing, Vol. 5, 2021, pp. 1–40.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Singh, S., S. Ramakrishna, and F. Berto. 3D Printing of polymer composites: A short review. Material Design & Processing Communications, Vol. 2, 2019, pp. 1–13.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ehrmann, G. and A. Ehrmann. 3D printing of shape memory polymers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 138, 2021, id. 50847.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Slavkovic, V., N. Grujovic, A. Dišic, and A. Radovanovic. Influence of annealing and printing directions on mechanical properties of PLA shape memory polymer produced by fused deposition modeling. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Serbian Society of Mechanics, vol. 19, Mountain Tara, Serbia, 2017, pp. 19–21.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Ma, S., Z. Jiang, M. Wang, L. Zhang, Y. Liang, Z. Zhang, et al. 4D printing of PLA/PCL shape memory composites with controllable sequential deformation. Bio-Design and Manufacturing, Vol. 4, 2021, pp. 867–878.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Leist, S. K., D. Gao, R. Chiou, and J. Zhou. Investigating the shape memory properties of 4D printed polylactic acid (PLA) and the concept of 4D printing onto nylon fabrics for the creation of smart textiles. Virtual and Physical Prototyping, Vol. 12, 2017, pp. 290–300.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Shao, L. H., B. Zhao, Q. Zhang, Y. Xing, and K. Zhang. 4D printing composite with electrically controlled local deformation. Extreme Mechanics Letters, Vol. 39, 2020, id. 100793.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Maraveas, C., I. S. Bayer, and T. Bartzanas. 4D printing: Perspectives for the production of sustainable plastics for agriculture. Biotechnology Advances, Vol. 54, 2022, id. 107785.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Langford, T., A. Mohammed, K. Essa, A. Elshaer, and H. Hassanin. 4D printing of origami structures for minimally invasive surgeries using functional scaffold. Applied Sciences, Vol. 11, 2021, pp. 1–13.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Alshebly, Y. S., M. Nafea, H. A. Almurib, M. S. Ali, A. A. Faudzi, and M. T. Tan. Development of 4D Printed PLA Actuators with an Induced Internal Strain Upon Printing. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control & Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS), 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Jo, M. Y., Y. J. Ryu, J. H. Ko, and J. S. Yoon. Effects of compatibilizers on the mechanical properties of ABS/PLA composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 125, 2012, pp. E231–E238.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Salim, M. A., Z. H. Termiti, A. M. Saad, F. K. Mekanikal, and U. Teknikal. Mechanical properties on ABS/PLA materials for geospatial imaging printed product using 3D printer technology. Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, 2019, pp. 11357–11358.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Rigoussen, A., P. Verge, J. M. Raquez, Y. Habibi, and P. Dubois. In-depth investigation on the effect and role of cardanol in the compatibilization of PLA/ABS immiscible blends by reactive extrusion. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 93, 2017, pp. 272–283.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Rigoussen, A., J. M. Raquez, P. Dubois, and P. Verge. A dual approach to compatibilize PLA/ABS immiscible blends with epoxidized cardanol derivatives. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 114, 2019, pp. 118–126.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chaudry, U. M. and K. Hamad. Fabrication and characterization of PLA/PP/ABS ternary blend. Polymer Engineering & Science, Vol. 59, 2019, pp. 2273–2278.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Chaikeaw, C. and K. Srikulkit. Preparation and properties of poly (lactic acid)/PLA-g-ABS blends. Fibers and Polymers, Vol. 19, 2018, pp. 2016–2022.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Dhinesh, S. K., P. S. Arun, K. K. Senthil, and A. Megalingam. Study on flexural and tensile behavior of PLA, ABS and PLA-ABS materials. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 45, 2021, pp. 1175–1180.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Zhang, J., S. Wang, Y. Qiao, and Q. Li. Effect of morphology designing on the structure and properties of PLA/PEG/ABS blends. Colloid and Polymer Science, Vol. 294, 2016, pp. 1779–1787.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ranakoti, L., B. Gangil, S. K. Mishra, T. Singh, S. Sharma, R. A. Ilyas, et al. Critical review on polylactic acid: properties, structure, processing, biocomposites, and nanocomposites. Materials (Basel), Vol. 15, 2022, pp. 1–29.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Roberson, D., C. M. Shemelya, E. MacDonald, and R. Wicker. Expanding the applicability of FDM-type technologies through materials development. Rapid Prototyping Journal, Vol. 21, 2014, pp. 137–143.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Salem Bala, A. and S. Bin Wahab. Elements and materials improve the FDM products: A review. In Advanced Engineering Forum, Vol. 16, 2016, pp. 33–51.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Dudek, P. F. FDM 3D printing technology in manufacturing composite elements. Archives of metallurgy and materials, Vol. 58, 2013, pp. 1415–1418.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Overview of materials for Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS), Extruded, http://www.matweb.com/search/DataSheet.aspx? MatGUID = 3a8afcddac864d4b8f58d40570d2e5aa&ckck = 1/, retrieved on 12th Feb 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Overview of materials for Polylactic Acid (PLA) Biopolymer, http://www.matweb.com/search/DataSheet.aspx? MatGUID = ab96a4c0655c4018a8785ac4031b9278/, retrieved on 12th Feb 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Yan, B., S. Gu, and Y. Zhang. Polylactide-based thermoplastic shape memory polymer nanocomposites. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 49, 2013, pp. 366–378.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Bonda, S., S. Mohanty, and S. K. Nayak. Influence of compatibilizer on mechanical, morphological and rheological properties of PP/ABS blends. Iranian Polymer Journal, Vol. 23, 2014 Jun, pp. 415–425.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Hassan, A. and W. Y. Jwu. Mechanical properties of high impact ABS/PC blends–effect of blend ratio. In Polymer Symposium, Kebangsaan Ke-V, Malaysia, 2005 Aug.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Sethi, J., M. Illikainen, M. Sain, and K. Oksman. Polylactic acid/polyurethane blend reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals with semi-interpenetrating polymer network (S-IPN) structure. European Polymer Journal, Vol. 86, 2017 Jan, pp. 188–199.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Oksman, K., M. Skrifvars, and J. F. Selin. Natural fibres as reinforcement in polylactic acid (PLA) composites. Composites Science and Technology, Vol. 63, No. 9, 2003 Jul, pp. 1317–1324.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ramanjaneyulu, B., N. Venkatachalapathi, and G. Prasanthi. Thermal and mechanical properties of PLA/ABS/TCS polymer blend composites. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series C, Vol. 102, No. 3, 2021 Jun, pp. 799–806.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Kılıç, M., E. Burdurlu, S. Aslan, S. Altun, and Ö. Tümerdem. The effect of surface roughness on tensile strength of the medium-density fiberboard (MDF) overlaid with polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Materials & Design, Vol. 30, No. 10, 2009 Dec, pp. 4580–4583.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Juneja, S., J. S. Chohan, K. Raman, S. Sharma, R. A. Ilyas, M. R. M. Asyraf, et al. Impact of process variables of acetone vapor jet drilling on surface roughness and circularity of 3D-printed ABS parts: fabrication and studies on thermal, morphological, and chemical characterizations. Polymers 14, Vol. 7, 2022, id. 1367.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Jha, K., Y. K. Tyagi, R. Kumar, S. Sharma, M. R. M. Huzaifah, C. Li, et al. Assessment of dimensional stability, biodegradability, and fracture energy of bio-composites reinforced with novel pine cone. Polymers 13, Vol. 19, 2021, id. 3260.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Chohan, J. S., N. Mittal, R. Kumar, S. Singh, S. Sharma, S. P. Dwivedi, et al. Optimization of FFF process parameters by naked mole-rat algorithms with enhanced exploration and exploitation capabilities. Polymers 13, Vol. 11, 2021, id. 1702.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Rajawat, A. S., S. Singh, B. Gangil, L. Ranakoti, S. Sharma, M. R. Asyraf, et al. Effect of marble dust on the mechanical, morphological, and wear performance of basalt fibre-reinforced epoxy composites for structural applications. Polymers 14, Vol. 7, 2022, id. 1325.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Khare, J. M., S. Dahiya, B. Gangil, L. Ranakoti, S. Sharma, M. R. Huzaifah, et al. Comparative analysis of erosive wear behaviour of epoxy, polyester and vinyl esters based thermosetting polymer composites for human prosthetic applications using Taguchi design. Polymers 13, Vol. 20, 2021, id. 3607.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete