Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

-

Eliana Nope

, Gabriel Sathicq

Abstract

This work reports the influence of cationic charge on the magnetic response of hydrotalcites combined with magnetite nanoparticles. Fe3O4 particles were synthesized by the co-precipitation method, and the resulting magnetic particles were dispersed. A mixture of Mg, Me (Ni, Co, Sr), and Al nitrates with stoichiometric Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios of 2 and 3 was added. X-ray diffraction patterns revealed the presence of Fe3O4 and hydrotalcite main phases and some secondary phases in the Sr2+-modified sample. The FTIR spectra provided information on the chemical structure of the materials and confirmed the presence of representative vibrational bands for the composite structure. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms analyzed by the BET method indicated remarkable porous properties for the synthesized samples, and higher surface areas of 160 and 145 m2/g were obtained for Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 3 and Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 3, respectively, with an increasing modifying cation ratio. The morphological characterization through SEM showed that a higher content of divalent cations favors the formation of larger particles, reaching a particle size of 786 nm for the sample with Ni2+ addition. The magnetic measurements showed marked ferromagnetic behavior with variations in saturation and remanent magnetizations due to the influence of modifying cations. The analysis revealed a correlation between the cationic charge and the magnetic and structural properties of the hydrotalcites, suggesting effective control over the magnetic properties by manipulating the cationic charge in these composite materials.

1 Introduction

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs) consist of layers similar to the brucite structure containing hydroxides of divalent metal cations (Me2+ = Mg, Co, Cu, Ni, Zn) and trivalent cations (Me3+ = Al, Fe, Ga) [1]. In the layered structure, each cation is octahedrally surrounded by six

In recent years, hydrotalcites as multifunctional materials have received considerable attention due to their highly ordered lamellar structure and biocompatibility with low toxicity, presenting potential applications in fields such as environmental protection [7], catalysis [8], biomedicine, and as adsorbents [1,9,10]. Moreover, owing to the abundant ionic surface (comprising hydroxyl groups) and the intrinsic positive charge possessed by these materials, the sheets can effectively engage with other nanomaterials or polymeric molecules. This interaction leads to the formation of 3D nanocomposites with distinct structures, such as Core@LDH, Shell@LDH, functionalized LDH, and LDH-coated structures. Within the core-layer architecture, the versatility and functionality of LDH serve a dual purpose: functioning as both the shell component for modifying other particles and as a core that can be coated with additional nanomaterials [2,11]. However, the separation and recovery of these materials in some processes is still difficult. Therefore, solid materials with magnetic properties can be easily separated by applying an external magnetic field, improving their recovery, and avoiding the loss of materials.

Magnetic nanoparticles are a popular research topic in a wide range of applications, such as targeted drug delivery, environmental remediation, magnetic resonance imaging, and catalysis [12,13,14,15]. Magnetic separation has been shown to be a promising, fast, simple, and highly effective method in solid–liquid phases. In addition, in the administration of drugs, they significantly facilitate the precise transfer of molecules to a specific site, without causing side effects in the human body, and their magnetic properties, such as superparamagnetic behavior, allow the transport of pharmaceuticals to be much more efficient [16,17].

Thus, several investigations have focused on the synthesis of magnetic hydrotalcites due to the properties of these materials and their layered nanostructures with high thermal and chemical stability [2,18]. They have been studied in targeted drug delivery processes, in the selective administration of chemotherapeutic agents, in the removal of toxic metal ions and dye treatments in wastewater, and as catalytic materials for obtaining platform molecules from lignocellulosic waste. Recently, Huang et al. [19] described the synthesis of a catalyst from reconstituted magnetic hydrotalcites with graphene quantum dots (GQDs) for efficient degradation of tetrachloroguaiacol (TeCG). The results showed that GQD provided greater thermal stability, surface area, and charge transferability with a removal efficiency of 89.34% within 60 min. These results highlight the potential of modified hydrotalcite-based materials modified to be applied to environmental remediation and water treatment. On the other hand, Hu et al. [20] carried out research on the CuO modification of hydrotalcites for the improvement of their nitrate adsorption ability in wastewater. The material was synthesized by using the impregnation method and was characterized with a high adsorption capacity of 102 mg/g. Moreover, the material showed good stability, and it retained more than 83% of its adsorption capacity after four regeneration cycles. These findings demonstrate the potential of modified hydrotalcites as an application in the treatment of water with nitrates. Structural modifications in hydrotalcites enable fine-tuning their properties and broadening their potential applications. Therefore, it is essential to analyze how the Me2+/Me3+ ratio (where Me = Ni, Co, Sr) influences the structural and magnetic characteristics of hydrotalcites combined with Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles.

Magnetic hydrotalcites are generally synthesized by magnetic particle dispersion processes in the matrix of lamellar double hydroxides, where magnetic nanoparticles of magnetite (Fe3O4) or magnesium ferrite (MgFe2O4) are mainly used. The morphology of the sheets on the cores of the magnetic nanoparticles can form vertical, horizontal, or mixed orientations. This orientation will depend on the synthesis method, as well as the composition of the cations in the sheets and the solvent effect in the synthesis process [11,21,22]. In previous studies, we have observed that the synthesis of hydrotalcites with a double divalent cation or ternary hydrotalcites plays a crucial role in shaping the morphology of these materials [23]. However, the effect of the molar ratio of metal cations on the magnetic properties of Fe3O4 has been relatively underexplored.

Therefore, in this work, ternary magnetic hydrotalcites with varying y-values were synthesized in order to evaluate the impact of cationic loading on the magnetic and structural properties of these materials. Comprehensive characterizations were carried out using advanced techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), to determine the crystal structure, vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) to evaluate the magnetic properties, and N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm analysis to investigate porosity and specific surface area. This approach allows a detailed correlation between the cation charge and the magnetic and structural properties of hydrotalcites, facilitating effective control of magnetic properties through precise manipulation of the molar ratio of divalent and trivalent cations.

2 Experimental

2.1 General information

All of the chemicals (such as Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Co(NO3)2·6H2O, Sr(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O, FeCl2·6H2O, FeCl3·6H2O, NaOH, and HNO3) were purchased in analytical purity from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Beijing, China), and used without any further purification. The synthesis process of the materials is illustrated in Figure 1. It begins with the preparation of Fe₃O₄ magnetic nanoparticles via the coprecipitation method, using ferric and ferrous iron salts in a basic aqueous solution. Once Fe₃O₄ is obtained, it is combined with the precursor salts of divalent and trivalent cations for the synthesis of hydrotalcite, also using the coprecipitation method, as described below.

Schematic synthesis of the magnetic hydrotalcite samples with Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios using the coprecipitation method.

2.2 Synthesis of Fe3O4 particles

Magnetic NPs were synthesized by the co-precipitation method using the methodology proposed by Kang et al. [24]. A molar ratio of Fe(ii)/Fe(iii) = 0.5 and pH = 11–12 were used. Briefly, 0.85 mL of 12.1 N HCl and 25 mL of purified, deoxygenated water (by nitrogen gas bubbling for 30 min) were combined, and 5.2 g of FeCl3 and 2.0 g of FeCl2 were successively dissolved in the solution with stirring. The resulting solution was added dropwise to 250 mL of 1.5 M NaOH solution under vigorous stirring, generating a black precipitate, which was then centrifuged at 400 rpm and washed with deoxygenated water. Subsequently, 500 mL of 0.01 M HCl was added to neutralize the anionic charges on the NPs. The solid was obtained by centrifugation, washed with distilled water, and then dried at 353 K.

The mechanism for the synthesis of Fe3O4 involves three key steps: (1) the dissociation of iron salts in aqueous solution (1), (2) the precipitation of iron hydroxides upon the addition of NaOH, and (3) a subsequent dehydration and redox process that leads to the formation of Fe₃O₄ [25,26]:

2.3 Synthesis of magnetic ternary hydrotalcites

The synthesis of magnetic ternary hydrotalcites was carried out following the methodology proposed by Zhang et al. [22], using Fe3O4 as a magnetic source. For this, 1 g of Fe3O4 was dispersed in 100 mL of a water/methanol solution (V. water/V. methanol = 1/1, v/v), which was subjected to ultrasonification for 20 min to obtain a uniform suspension. Then, the pH was adjusted to 10 by adding a 2.0 M alkaline solution of Na2CO3 and NaOH. A mixture solution containing Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Me(NO3)2·6H2O, and Al(NO3)3·9H2O with a Me2+/Al3+ = 2 and 3 ratio (Me = Ni, Co, Sr) with y = 0.33 and 0.25, respectively, was added dropwise to the suspension and aged at 140°C for 24 h. The resulting solid was separated magnetically, washed with deionized water, and dried at 80°C overnight. The materials are denoted as Fe3O4–MgCoAl x = 3, Fe3O4–MgNiAl x = 3, Fe3O4–MgSrAl x = 3, Fe3O4–MgCoAl x = 2, Fe3O4–MgNiAl x = 2, and Fe3O4–MgSrAl x = 2. In addition, Fe3O4–MgAl x = 3 and Fe3O4–MgAl x = 2 were synthesized as control samples, where x represents the Me2+/Me3+ ratio, 2 and 3.

Hydrotalcite is synthesized with a [urea]/[

A 2M alkaline solution of NaOH and Na₂CO₃ (1:1 molar ratio) was prepared by dissolving NaOH in distilled water, followed by the gradual addition of Na₂CO₃ until the final volume was reached. The mixture was stirred continuously until a homogeneous, translucent solution was obtained.

2.4 Characterization

The XRD patterns and crystalline phases were recorded with a Panalytical X´pert PRO-MPD equipment with an ultrafast X´Celerator detector in Bragg–Brentano geometry, using Copper Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å), 2θ = 10–90° with a step of 0.0263°, and a capture time of 100 s. The patterns were analyzed with the General Structure Analysis System (GSAS II) software. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet iS50 spectrometer in the range of 4,500–600 cm−1 using pressed KBr pellets. Morphology properties of the compounds were evaluated by SEM (JSM 6610-LV JEOL equipment). The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) isotherm and Barrett, Joyner, and Halenda (BJH) method were used to calculate the specific surface area and pore volume, respectively, and N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the solids were measured at 77 K (Micromeritics ASAP 2020 equipment). The samples were previously degassed at 100°C under vacuum for 18 h. The magnetic measurements were developed using a VSM Quantum Design. The measurements as a function of temperature were carried out in the temperature range of 50–300 K using the zero-field cooled–field cooled (ZFC-FC) mode.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structural analysis

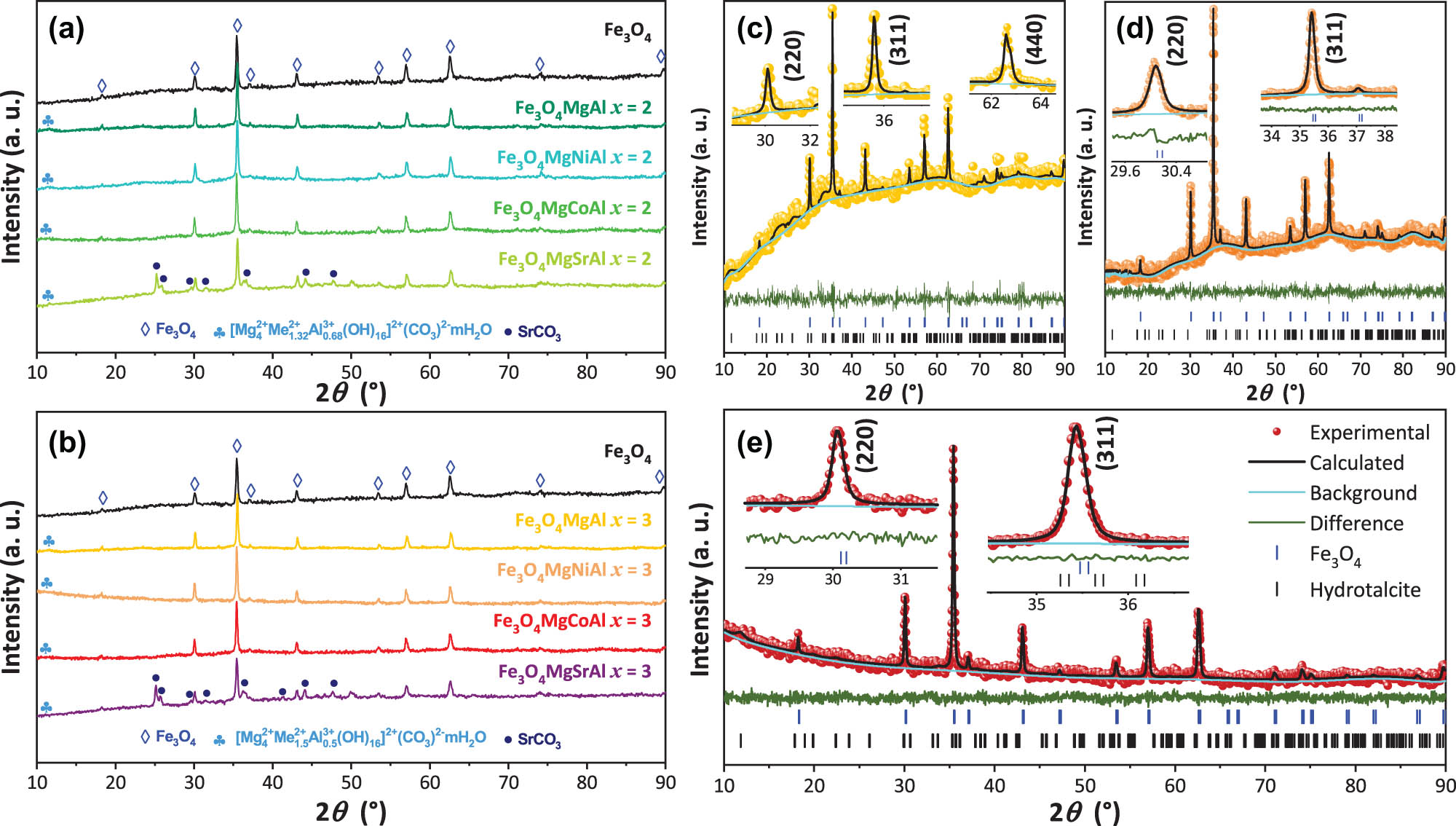

The XRD patterns of the synthesized samples (Figure 2) showed characteristic peaks corresponding to the crystal structure of hydrotalcite. The most prominent peak was observed around 11.6° 2θ, which is assigned to the (003) plane diffraction, confirming the formation of the hydrotalcite phase [3]. All of the samples were contrasted with the hexagonal phase of hydrotalcite with space group

XRD patterns of the Fe3O4MgAl magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of (a) x = 2 and (b) x = 3. Rietveld refinements for (c) Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 2, (d) Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 3, and (e) Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 3 samples. The experimental pattern, calculated profile, and Bragg peak positions are indicated by circles, a black curve, and tick marks, respectively. The bottom curve shows the difference between the observed and calculated intensities.

Structural parameters of the magnetic hydrotalcite samples with Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios (W (%) is the weight percentage of each sample)

| Sample |

|

χ 2 | R 2 | Fe3O4 | Hydrotalcite | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W (%) | a = b = c (Å) | V (Å3) | CS (nm) | W (%) | a = b (Å) | c (Å) | V (Å3) | Cs (nm) | ||||||||||

| 2θ (°) | Sch | L(||) | L(⊥) | 2θ (°) | Sch | L(||) | L(⊥) | |||||||||||

| Fe3O4 | — | 0.826 | 0.161 | 100.00 | 8.397 | 592.15 | 35.44 | 33.40 | 65.55 | 59.69 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fe3O4MgAl | 2 | 1.220 | 0.184 | 79.64 | 8.385 | 589.49 | 35.46 | 34.24 | 50.77 | 50.62 | 20.360 | 5.228 | 15.090 | 412.38 | 11.65 | 16.39 | 15.00 | 15.80 |

| 3 | 1.051 | 0.232 | 77.58 | 8.386 | 589.77 | 35.49 | 48.64 | 57.05 | 55.95 | 22.420 | 5.283 | 15.150 | 422.84 | 11.50 | 10.19 | 15.05 | 15.05 | |

| Fe3O4MgCoAl | 2 | 0.684 | 0.100 | 81.81 | 8.387 | 589.87 | 35.51 | 41.77 | 48.02 | 52.09 | 18.187 | 5.392 | 15.067 | 438.03 | 11.67 | 13.33 | 3.82 | 3.86 |

| 3 | 0.774 | 0.192 | 89.39 | 8.388 | 590.25 | 35.40 | 48.63 | 48.92 | 54.92 | 10.607 | 5.291 | 15.173 | 424.73 | 12.01 | 108.63 | 3.10 | 4.29 | |

| Fe3O4MgNiAl | 2 | 0.904 | 0.206 | 64.41 | 8.386 | 589.79 | 35.50 | 41.76 | 47.47 | 44.98 | 35.587 | 5.235 | 14.972 | 410.34 | 11.51 | 9.99 | 5.58 | 1.87 |

| 3 | 0.772 | 0.188 | 74.74 | 8.386 | 589.74 | 35.41 | 48.63 | 59.15 | 69.09 | 25.260 | 5.410 | 14.922 | 436.79 | 11.62 | 92.67 | 8.35 | 12.84 | |

| Fe3O4MgSrAl | 2 | 0.888 | 0.154 | 59.99 | 8.391 | 590.82 | 35.53 | 41.77 | 59.59 | 42.50 | 5.342 | 5.264 | 15.074 | 417.69 | 11.74 | 92.68 | 7.79 | 5.74 |

| 3 | 0.985 | 0.221 | 41.35 | 8.390 | 590.63 | 35.44 | 33.40 | 43.09 | 43.45 | 27.538 | 5.280 | 15.228 | 424.46 | 11.09 | 92.63 | 2.40 | 2.35 | |

Additionally, the presence of high-intensity peaks around 30°, 35°, 43°, 53°, 57° and 62° 2θ in all samples indicates the coexistence of Fe3O4 particles embedded in the hydrotalcite matrix, corresponding to the (220), (311), (440), (422), (511), and (440) diffraction planes, respectively. This phase was indexed to the cubic Fe3O4 phase with space group

The crystallite size (CS) of the present phases in the materials was also calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation (5) [33,34],

where K = 0.94 is the Scherrer form factor, λ = 0.1542 nm is the Cu cathode radiation, β is the full width at half-maximum of the peaks, and θ is the Bragg diffraction angle. The diffraction planes used to determine CS were (003) for the hydrotalcite phase and (311) for the Fe3O4 phase. Table 1 summarizes the findings. The CS for the Fe3O4 phase showed an increase when it coexisted with hydrotalcites with an Me2+/Me3+ ratio of 3. These hydrotalcites showed variable CS, with a tendency to increase as the molar ratio increases to x = 3.

Rietveld refinement was carried out (using GSAS-I software [35,36,37]) to determine complementary structural properties of the acquired samples and their present phases. The lattice parameters and unit cell volume may be obtained using the established refinement procedure. These, along with other important factors, are provided in Table 1. Figure 2c and d shows the plots created for the refinement of some samples. This research demonstrates that the materials crystallized in a hexagonal and cubic form, for hydrotalcite and Fe3O4 phases, respectively, which is consistent with earlier semi-quantitative investigations [31,32], as evidenced by the overlap of theoretical and experimental patterns. All the samples have lattice parameters close to 8.386 Å, which is consistent with a spinel-type structure. Quantitative analysis of the phase percentage in the synthesized samples revealed significant variation in the distribution of Fe3O4 and hydrotalcite. The percentages of Fe₃O₄ ranged from 41.35 to 89.39%, while those of hydrotalcite ranged from 5.34 to 35.59%. This variability suggests that the synthesis conditions strongly influence the phase structure and ratio, thereby affecting the physical and chemical properties of the composite material. The sample Fe3O4MgNiAl (x = 2) exhibits the highest content of hydrotalcite (35.59%), followed by Fe3O4MgNiAl (x = 3) with 25.26%. On the other hand, the samples Fe3O4MgSrAl (x = 2) and Fe3O4MgCoAl (x = 3) show the lowest contents of hydrotalcite (5.34 and 10.61%, respectively). This suggests that the addition of Sr and Co particularly stabilizes the spinel phase, significantly reducing the amount of hydrotalcite formed. In contrast, Ni appears to promote the formation of hydrotalcite due to its influence on the stability of lamellar phases, while Sr and Co seem to better stabilize the spinel-type structure.

A higher Fe3O4 content could favor magnetic properties, while a higher proportion of hydrotalcite could enhance catalytic and adsorption properties. The ability to adjust these ratios is crucial for the optimization of the material for specific applications. Furthermore, Rietveld crystallite sizes were also estimated in both perpendicular L(⊥) and parallel L(∥) directions with equations (6) and (7), based on GSAS revised Lorentzian component parameters (LX and ptec), and K and λ correspond to Scherrer parameters [38,39]. The samples reveal significant variation in L(∥) and L(⊥) parameters, suggesting a direct effect of composition on structural anisotropy. In the pure Fe3O4 sample, L(∥) and L(⊥) have values of 65.55 and 59.69 nm, respectively, indicating slight anisotropy in crystal growth. With the addition of the basal hydrotalcite, Fe3O4MgAl sample, both parameters decrease, reaching values of 55.92 and 55.07 nm, suggesting that the addition of the hydrotalcites limits the growth of the crystalline domains [40]. In general, a decrease of these parameters was observed in the Fe3O4 phase, reaching a minimum in the Fe3O4MgSrAl sample. The samples Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 3 and Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 3 exhibit the largest crystallite sizes, suggesting better crystallization or lower stresses in the lattice. For the hydrotalcite phase, these parameters presented a notable decrease with the addition of the substituent cations, reflecting a more restricted structure in terms of crystal growth and a limitation in the crystalline development with these compositional modifications. In general, the incorporation of different cations influences the size and preferential orientation of crystallite growth, which can directly impact their structural and functional properties.

In general, all systems exhibited a spinel structure obtained through various synthesis methods. Most of the methods reported in the literature produce crystallites with sizes similar to those obtained in this study. For instance, the compounds Zn1−x Ni x Fe2O4, synthesized by sol–gel, sol–gel auto-combustion, microwave combustion, auto-combustion, thermal decomposition, and chemical co-precipitation methods, exhibited crystallite sizes ranging from 18 to 70 nm, depending on the synthesis technique used [41].

Magnesium plays a significant role in determining the crystal size of the synthesized materials (Table 1). The incorporation of Mg2+ into the spinel structure, either alone or in combination with other cations (such as Ni2+, Co2+, Sr2+, and Al3+), has a marked effect on the crystallite size and stability of the resulting phase. The incorporation of magnesium generally leads to a slight reduction in the crystal size compared to pure Fe3O4. This slight reduction in the crystal size is probably due to the substitution of Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions by Mg2+, which has a smaller ionic radius (0.72 Å) compared to Fe2+ (0.78 Å). This substitution can induce local distortions in the crystal lattice, which hinders crystal growth and favors the formation of smaller crystallites.

The effect of the (Mg + Me)/Al ratio on the crystallite size of hydrotalcite could be explained in terms of the presence of cations. The presence of a larger number of trivalent cations (Al3+) in the layers enhances the rate of stacking of the layers [42]. Samples containing only magnesium exhibit an (Mg/Al) = 1 ratio, while those combining magnesium with another divalent cation (Ni, Co, Sr) show a higher ratio of 2. This implies that samples with a higher (Mg + Me)/Al ratio have a greater proportion of divalent cations relative to trivalent cations, which may affect the crystallite size and the stability of the lamellar phase due to the lower positive charge density in the layers.

On the other hand, there is a noticeable variation in the hydrotalcite lattice parameters, which is associated with the crystalline development due to the chemical modification. Finally, regarding the parameter Chi (χ 2), it can be concluded that the Rietveld refinements made for the samples obtained were adequate, given the structural conditions exhibited by both phases in the samples. In addition, the R 2 parameter, as another reliability indicator, also makes it possible to corroborate the accuracy and validity of the refinement process.

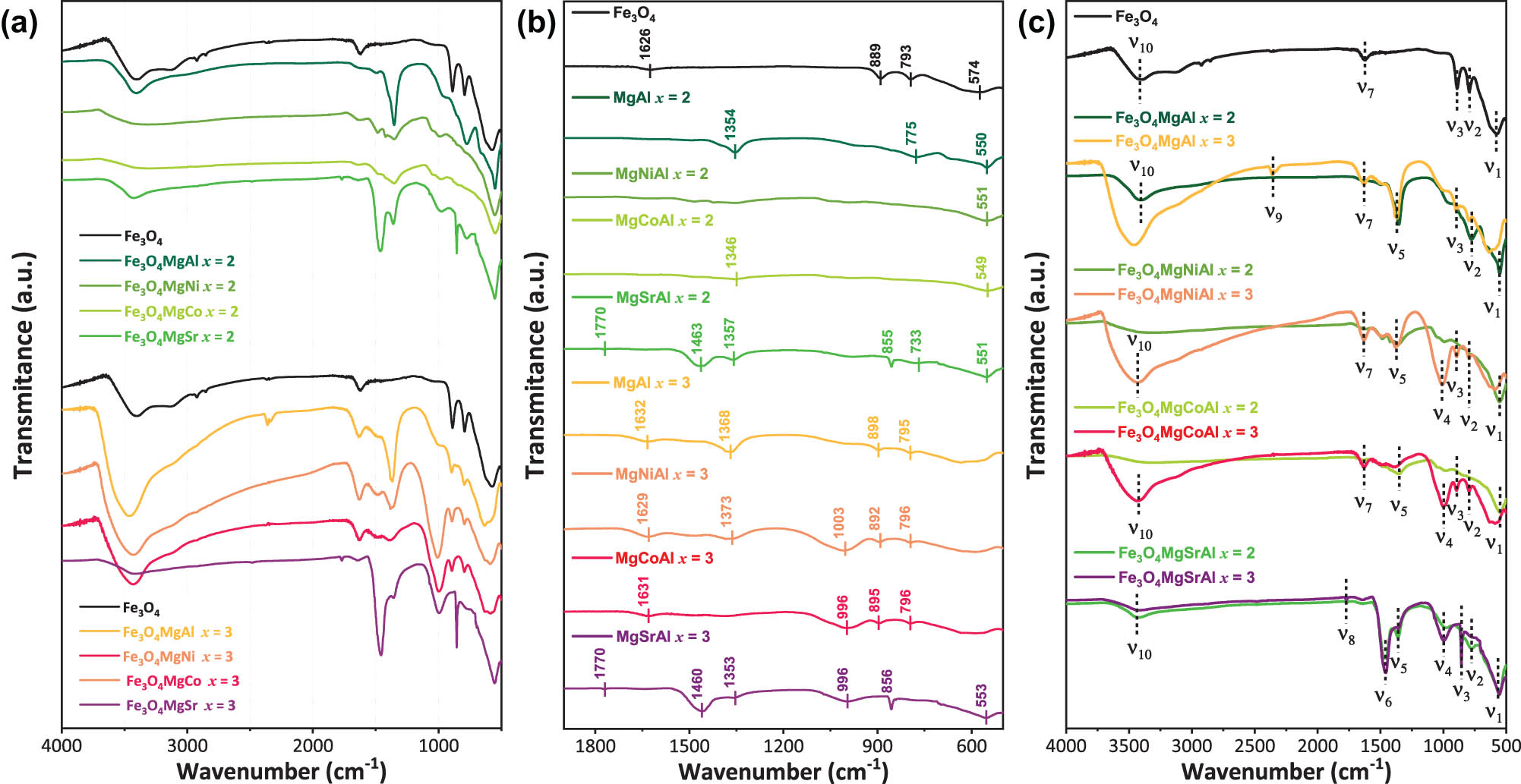

The IR spectra of hydrotalcites show variable vibrational bands assigned to high (greater than 2,000 cm−1), middle (2,000–1,000 cm−1), and low (below 1,000 cm−1) frequency ranges. The infrared spectra reveal distinctive features in the materials synthesized with Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios of 2 and 3. These spectra resemble those of hydrotalcite and magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. In Figure 3 and Table 2, a broad adsorption band with a maximum at 549–574 cm−1 (ν

1) corresponds to Fe–O bond stretching vibrations [31,32]. The stretching of Al–OH may be responsible for the bands at 667 and 733 cm−1 (ν

2). The band at 795 cm−1 (ν

2) is attributed to symmetric and antisymmetric vibrations of the Fe–O–H bond, characteristic of magnetic nanoparticles [32,43,44]. The weak band at 870 cm−1 (ν

3) was due to the characteristic O–C–O bond stretching vibrations of bidentate carbonate [45]. These signals are less intense in the synthesized ternary magnetic hydrotalcites, suggesting a potential core–shell structure, with the external layer of the hydrotalcite shielding the absorption of the Fe–O bond in the Fe3O4 phase [46]. The bands at 855 and 856 cm−1 (ν

3) are assigned to SrCO3 bending vibrations in Fe3O4-MgSrAl sample [47,48]. These results indicate that the incorporation of magnetic nanoparticles into the hydrotalcite does not alter the laminar structure, whereas changes in the Me2+/Me3+ molar ratio influence the formation of this structure. The band around 1,000 cm−1 (ν

4) represents the Me–O–Me skeletal vibrations and is pronounced in materials with Ni2+, Co2+, and Sr2+ [46]. However, this intensity is influenced by the Me2+/Me3+ molar ratio in brucite-like lamellar layers, being lower in ternary magnetic hydrotalcite due to the presence of another divalent cation. In addition, the absorption band around 1,369 cm−1 (ν

5) was considered to be caused by the asymmetric stretching bond of the intercalated NO3 [46,49] and by asymmetric vibrations of the

(a) and (b) FTIR spectra of the magnetic hydrotalcite samples with Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios of 2 and 3; (c) Me2+/Me3+ comparisons on the IR spectra of hydrotalcites. The dotted lines indicate the main bond vibrations.

Frequencies of absorption maxima (ν, cm−1) in the IR spectra of magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of Me2+/Me3+

| Sample | Fe3O4 | Fe3O4MgAl | Fe3O4MgNiAl | Fe3O4MgCoAl | Fe3O4MgSrAl | Atomic vibrations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me2+/Me3+ | – | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| ν 1 (cm−1) | 574 | 550 | — | 551 | — | 549 | — | 551 | 553 | Fe–O stretching vibrations [32]; Al–O–Al [44] |

| ν 2 (cm−1) | 793 | 775 | 795 | — | 796 | — | 796 | 773 | — | Fe–O–H vibration; Al–OH translation [53]; Al–O [44] |

| ν 3 (cm−1) | 889 | — | 898 | — | 892 | — | 895 | 855 | 856 | O–C–O stretching vibrations [45]; Sr–O bending vibrations [46] |

| ν 4 (cm−1) | — | — | — | — | 1003 | — | 996 | — | 996 | Me–O–Me [46] |

| ν 5 (cm−1) | — | 1,354 | 1,368 | — | 1,373 | 1,346 | — | 1,357 | 1,353 |

|

| ν 6 (cm−1) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1463 | 1,460 | CO3 symmetric and antisymmetric stretching [51] |

| ν 7 (cm−1) | 1,626 | — | 1,632 | — | 1,629 | — | 1,631 | — | — | H2O [52], O–H bending vibration [53] |

| ν 8 (cm−1) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1,770 | 1,770 | H2O [54] |

| ν 9 (cm−1) | — | — | 2,352 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

|

| ν 10 (cm−1) | 3,403 | 3,406 | 3,467 | — | 3,427 | — | 3,435 | 3,422 | 3,414 | OH stretching vibration [44]; Me–OH [46] |

The presence of SrCO3 in the Sr-modified samples generated a vibration band at 1,463 cm−1 (ν

6) due to the CO3 symmetric and antisymmetric stretching [51]. In addition, an intense absorption peak at 1,460 cm−1 (ν

6) was attributed to the bending mode of the –OH groups of the adsorbed water interlayer [45]. The absorption band around 1,626 and 1,632 cm−1 (ν

7) was caused by the bending oscillation peaks of water molecules between layers [52,53]. The bending vibration of the interlayer water occurs at 1,700 cm−1 (ν

8) [54]. The band at 2,352 cm−1 (ν

9) was observed at high-frequency range and corresponded to

The presence of vibrations at 3,403–3,467 cm−1 (ν 10), which indicate the presence of OH stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group in Mg–Al hydrotalcite [44], was caused by the water molecules between the layers of the laminar structure [56]. This shift is attributed to the ratio and not to the presence of magnetic nanoparticles. Additionally, characteristic vibrations of the hydrotalcite exhibit a slight shift to higher frequencies 3,467 (x = 3) – 3,414 (x = 2) cm−1 (ν 10), attributed to the symmetric stretching of the hydroxyl group linked to the Me–OH bond on the surface of the hydrotalcite [53].

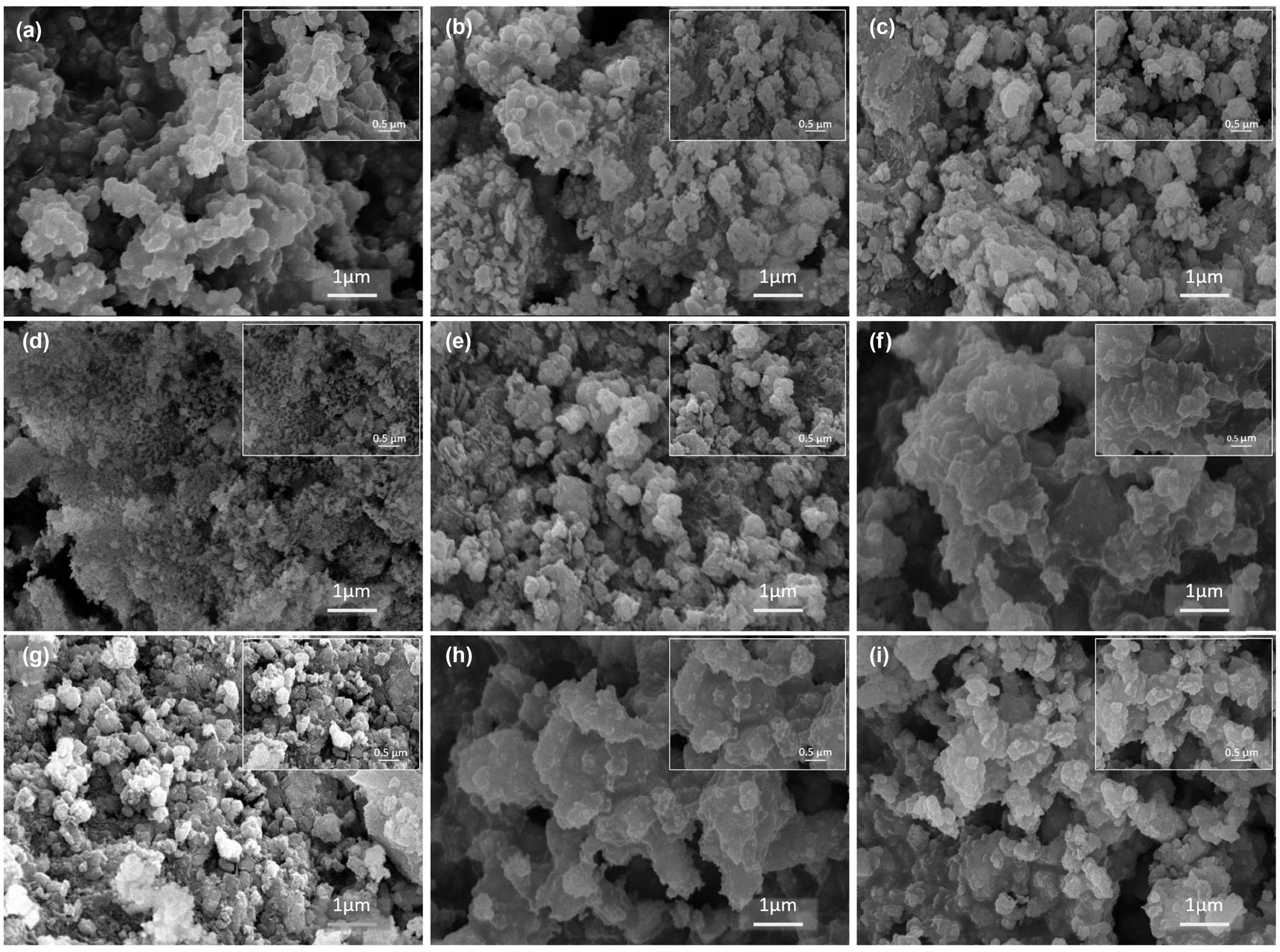

3.2 Morphological characterization

SEM images of the synthesized samples were obtained at magnifications of 15 kx and 30 kx (Figure 4). The Fe3O4 sample (Figure 4a) exhibits a granular morphology with spherical particles of uniform size, approximately 220 nm in diameter, indicating a controlled and homogeneous synthesis. A more complex structure with aggregated particles is observed in the Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 2 (Figure 4b) and x = 3 (Figure 4c) samples. The particles form larger agglomerates, increasing the surface roughness and porosity due to the presence of hydrotalcite, possibly attributed to the semi-amorphous matrix observed. The Fe3O4MgAl x = 2 (Figure 4d) and x = 3 (Figure 4g) images show a heterogeneous agglomerated structure, characteristic of hydrotalcites. The sample with x = 2 exhibits higher porosity and a more heterogeneous distribution of nanoparticles, suggesting a more intense interaction between the particles and the hydrotalcite matrix. The Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 2 (Figure 4e) and x = 3 (Figure 4f) micrographs demonstrate a more compact morphology for the sample x = 3. The Fe3O4 nanoparticles are uniformly distributed in both samples, although a slight tendency to agglomeration is observed in x = 3, causing larger agglomerates and difficult to perceive edges. Finally, the Fe3O4MgSrAl x = 2 (Figure 4h) and x = 3 (Figure 4i) images reveal a granular morphology with larger and less defined particles compared to the other samples. The presence of SrCO3 seems to significantly affect the structure, increasing the particle size and surface roughness. The distribution of Fe3O4 nanoparticles is less uniform, with a tendency to agglomerate formation for the sample x = 3. SEM analysis shows that the composition and molar ratio of metal cations significantly influence the morphology and distribution of Fe3O4 nanoparticles. These variations allow control of the morphological and structural properties of the material, which is crucial for its optimization of its potential surface applications. In general, the synthesized hydrotalcite samples show zones with irregular plate-like morphology agglomerations, which highlights the inherent characteristics of the layered materials, such as a high surface-to-volume ratio and a structural arrangement that favors the intercalation of ions and molecules. These results are comparable with previous reports [31,57].

SEM images at 15 kx and 30 kx (insets): (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 2, (c) Fe3O4MgCoAl x = 3, (d) Fe3O4MgAl x = 2, (e) Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 2, (f) Fe3O4MgNiAl x = 3, (g) Fe3O4MgAl x = 3, (h) Fe3O4MgSrAl x = 2, and (i) Fe3O4MgSrAl x = 3.

The calculated grain sizes for all systems are shown in Table 3. The Me2+/Me3+ ratio has a remarkable relationship with the particle size of the samples [58]. For the sample Fe3O4 (without metal addition), the particle size is 220.5 ± 72.3 nm, indicating a relatively large and less controlled structure, without the intervention of divalent or trivalent metals. In the case of Fe3O4MgAl (x = 2, Me2+/Me3+ = 2), the particle size decreases to 119.7 ± 59.2 nm, suggesting that the addition of Mg2+ and Al3+ favors further nucleation, reducing agglomeration and promoting smaller particles. However, when the ratio of Me2+/Me3+ in Fe3O4MgAl is increased (x = 3, Me2+/Me3+ = 3), the particle size increases to 224.3 ± 86.1 nm, suggesting that a higher Me2+ content could favor the formation of larger particles due to a lower crystallization rate or higher agglomeration. In Fe3O4MgCoAl (x = 2, Me2+/Me3+ = 2), the particle size is 180.7 ± 87.9 nm, showing an intermediate value between the Fe3O4 and Fe3O4MgAl (x = 2) samples. This size could indicate a moderate control on particle nucleation and growth, favored by the addition of Co2+. As the Me2+/Me3+ ratio is increased to 3 in Fe3O4MgCoAl (x = 3), the particle size increases to 206.1 ± 76.5 nm, suggesting increased particle agglomeration due to the higher Me2+ content. In Fe3O4MgNiAl (x = 2, Me2+/Me3+ = 2), the particle size is 235.8 ± 167.2 nm, which is considerably larger than in Fe3O4MgAl (x = 2), which might reflect the influence of Ni2+ on the formation of larger particles. Fe3O4MgNiAl (x = 3, Me2+/Me3+ = 3) exhibits the largest particle size of 785.9 ± 554.9 nm, suggesting that the higher proportion of Me2+ favors higher agglomeration or weaker crystallinity, resulting in larger and less homogeneous particles. Finally, the Fe3O4MgSrAl samples present an interesting behavior: in Fe3O4MgSrAl (x = 2, Me2+/Me3+ = 2), the particle size is 763.6 ± 260.3 nm, indicating larger agglomeration, while at Fe3O4MgSrAl (x = 3, Me2+/Me3+ = 3), the particle size is reduced to 258.9 ± 50.8 nm, suggesting that the addition of Sr2+ at this ratio may promote better formation of smaller and less agglomerated particles.

BET analysis results of Fe3O4MgAl magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of Me2+/Me3+

| Sample | Me2+/Me3+ | SEM particle size (nm) | S BET | Pore volume | Pore size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m2/g) | (cm3/g) | (nm) | |||

| Fe3O4 | — | 220.5 ± 72.3 | 17 | 0.04 | 3 |

| Fe3O4MgAl | 2 | 119.7 ± 59.2 | 52 | 0.42 | 29 |

| 3 | 224.3 ± 86.1 | 96 | 0.41 | 14 | |

| Fe3O4MgCoAl | 2 | 180.7 ± 87.9 | 33 | 0.16 | 17 |

| 3 | 206.1 ± 76.5 | 160 | 0.23 | 8 | |

| Fe3O4MgNiAl | 2 | 235.8 ± 167.2 | 19 | 0.16 | 24 |

| 3 | 785.9 ± 554.9 | 145 | 0.25 | 7 | |

| Fe3O4MgSrAl | 2 | 763.6 ± 260.3 | 6 | 0.35 | 36 |

| 3 | 258.9 ± 50.8 | 2 | 0.19 | 32 |

The textural properties of the synthesized materials were assessed through N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K, using the BET method, as shown in Figure 5. The adsorption isotherms of type III can be observed in the Sr samples. This classification is indicative of materials with limited microporosity or low porosity. This result suggests the potential partial formation of a laminar structure in these materials, possibly due to the presence of SrCO3, which was identified through FTIR and XRD analysis. Conversely, for the remaining materials, type IV isotherms were observed, characteristic of mesoporous materials, with a H3 type hysteresis loop. This pattern is typical in materials with plate-like particles and slit-shaped mesopores, which is a common feature in hydrotalcite-like materials [46,50].

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of Fe3O4MgAl magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of Me2+/Me3+.

Table 3 presents the parameters of the pore structure of the synthesized materials, including the specific surface area (S BET), pore volume, and pore size. The results reveal that different Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios lead to significant changes in textural properties. Materials with a Me2+/Me3+ molar ratio of 3 exhibit higher surface areas (S BET) compared to those with an Me2+/Me3+ ratio of 2. Thus, adjusting the ratio of metallic cations increases the pore size, leading to a decrease in the surface area. The pore size in all materials ranges from 3 to 36 nm, confirming the presence of mesopores in the laminar structure. These results indicate that the presence of magnetic nanoparticles does not impact the textural properties of the materials, and Fe3O4 acts as a magnetic separation agent. Furthermore, the potential core–shell structure seems to be favored at an Me2+/Me3+ ratio of 3, as these materials present a larger surface area, suggesting better coverage of Fe3O4 with the hydrotalcite. The Fe3O4MgNiAl and Fe3O4MgCoAl samples with Me2+/Me3+ of 3 showed a greater surface area, which is possibly associated with the nature of the synthesis that involves a heat of the suspension, which favors the simultaneous nucleation of the crystals [59].

The samples with the largest surface area are Fe3O4MgCoAl (x = 3) (160 m2/g) and Fe3O4MgAl (x = 3) (96 m2/g), which is consistent with a larger pore volume. This higher S BET could be related to higher particle dispersion and greater accessibility to active sites. On the contrary, the samples with lower surface area are Fe3O4 (17 m2/g) and Fe3O4MgSrAl (x = 3) (2 m2/g), which also present a reduced pore volume, suggesting that the incorporation of certain metals favors particle compaction and reduces the surface area available for interactions.

A trend is observed in which samples with a larger particle size (such as Fe3O4MgNiAl (x = 3) with 785.9 ± 554.9 nm) also have a reduced surface area (145 m2/g) and a smaller pore volume. This suggests that larger particle size may be related to lower surface accessibility and less porous structure. On the other hand, samples with a smaller particle size, such as Fe3O4MgAl (x = 2), show a larger surface area (52 m2/g) and significant pore volume (0.42 cm3/g), indicating greater exposure to active sites and greater potential for applications where high surface area availability is required.

3.3 Magnetic characterization

The magnetic behavior of the synthesized hydrotalcite-type materials was analyzed by magnetization as a function of magnetic field curves at 50 K (low temperature) and 300 K (room temperature). All samples showed narrow S‐shape type loops (Figure 6), indicating a superparamagnetic behavior with no significant changes observed in the magnetic curves across 50 K. The magnetic saturation (M s), remanence magnetization (M r), and coercivity field (H c) values calculated from magnetically recorded data are listed in Table 4. The M s values exhibit notable variations depending on the Me2+/Me3+ ratio and the analysis temperature. Notably, Table 4 shows that M s values are consistently lower in all magnetic hydrotalcite-type materials when compared to Fe3O4. Furthermore, it is worth noting that M s values increase at lower temperatures across all cases.

Temperature dependence of magnetization ZFC-FC measured at a 1 kOe applied field of the Fe3O4 magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of (a) x = 2 and (b) x = 3 measured at room temperature (T = 300 K).

Magnetic parameters obtained from the hysteresis loops for the Fe3O4 magnetic hydrotalcite with molar ratios of x = 2 and x = 3 at 50 K and 300 K

| Sample | Me2+/Me3+ | M s | M r | M r/M s | H c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 K | 300 K | 50 K | 300 K | 50 K | 300 K | ||||

| (emu/g) | (emu/g) | 50 K | 300 K | (Oe) | |||||

| Fe3O4 | — | 89.47 | 82.23 | 13.014 | 7.91 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.089 | 0.008 |

| Fe3O4MgAl | 2 | 34.3 | 31.54 | 5.52 | 3.79 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.031 | 0.040 |

| 3 | 34.24 | 32.43 | 5.81 | 3.19 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.060 | 0.080 | |

| Fe3O4MgCoAl | 2 | 37.79 | 31.7 | 7.45 | 5.26 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.053 | 0.003 |

| 3 | 33.67 | 31.6 | 6.42 | 4.13 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.053 | 0.090 | |

| Fe3O4MgNiAl | 2 | 39.96 | 34.25 | 7.01 | 4.8 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.072 | 0.016 |

| 3 | 48.25 | 30.54 | 8.07 | 3.66 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.064 | 0.017 | |

| Fe3O4MgSrAl | 2 | 38.16 | 34.96 | 6.71 | 4.62 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.011 | 0.066 |

| 3 | 32.13 | 29.34 | 5.43 | 3.31 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.023 | 0.017 | |

At 300 K, the M s values display minimal changes in the synthesized materials and do not exhibit significant differences concerning the Me2+/Me3+ ratio. These findings agree with the results reported by Chen et al. [21] for the Fe3O4@CuNiAl-LDH composite. Conversely, M s values obtained at 50 K show notable variations in materials containing double divalent cations, as well as in relation to the Me2+/Me3+ ratio at this analysis temperature.

The alteration of Fe3O4 magnetic properties when combined with hydrotalcite-type materials can be attributed to the coating of LDH sheets on the Fe3O4 core. This phenomenon is a consequence of the decorated structure, where the sheets may adopt a vertical orientation. This orientation is predominantly associated with the synthesis method, particularly influenced by the choice of solvent used for dispersing the Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the water/methanol solution (V water/V methanol = 1/1, v/v), which leads to this specific orientation [4]. The lower M s values observed in magnetic hydrotalcites can be attributed to the high concentration of sheets covering the Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The M r/M s ratio, which indicates magnetic stability, is generally low (<0.2), suggesting superparamagnetic behavior in samples at 300 K. It was observed to decrease in the following order: Fe3O4–MgCoAl > Fe3O4-MgNiAl > Fe3O4–MgSrAl > Fe3O4–MgAl > Fe3O4 for Me2+/Me3+ 2 and 3. This is related to the inter‐ and intragrain exchange interactions, sub‐lattice magnetization, magnetic anisotropy, and morphology of the tested sample [60].

These results indicate that the magnetic, crystalline, and textural properties of the synthesized materials are strongly influenced by the ratio and nature of the divalent cations. In general, a smaller crystallite size with a larger surface area was observed in the materials, which indicates greater surface interactions, except for the Fe3O4MgSrAl system (Me2+/M3+ = 3). This is because smaller particles have a higher surface/volume ratio, which increases the active area of the material. It was noted that the substitution of Mg2+ (0.72 Å), Co2+ (0.74 Å), and Ni2+ (0.69 Å) promotes the formation of layered structures due to their ionic radius similar to Fe3+ (0.78 Å). On the other hand, Sr2+ (1.18 Å) has a much larger ionic radius, which generates a structural disorder in the hydrotalcite. Thus, while Mg2+ stabilizes the structure and enhances the dispersion of Fe3O4, Co2+ and Ni2+ affect the magnetic properties by modifying anisotropy and coercivity. Sr2+, due to its large size, tends to destabilize the network, decreasing the active surface and the magnetization, as seen in the small M s values. The reduction in M s in these samples may be due to surface effects, where the magnetic moments at the interface do not fully contribute to the magnetic order [61]. This structural modification improves the interaction with other molecules or reagents, which is particularly relevant for catalytic and adsorption applications [62].

These modifications directly influence the magnetic properties since the decrease in saturation magnetization (M s) in the combined materials is associated with the presence of lamellar layers coating the magnetic nanoparticles. Furthermore, the remanence (M r) and coercivity (H c) show variations as a function of the type and proportion of the divalent cation, indicating that the structure affects the interaction between the magnetic domains. It is observed that samples with Ni2+ and Co2+ maintain relatively high M s values compared to other substitutions, suggesting that these species favor the preservation of the magnetic ordering of Fe3O4. Nevertheless, the slight decrease in M s with respect to the pure Fe3O4 sample could be related to the dilution of the Fe content in the crystal lattice and the possible formation of spinel phases with lower magnetic moment. Furthermore, the increase in the M r/M s ratio in samples with Co2+ indicates a higher magnetic anisotropy, suggesting a modification in the stability of the magnetic domains [63]. On the other hand, the introduction of Sr2+ generates a greater decrease in M s, possibly due to its large ionic radius, which induces structural distortions and reduces the amount of effective ferromagnetic interactions [36]. Furthermore, the increase in H c in some samples with Sr2+ indicates greater structural disorder, which affects the inversion dynamics of the magnetic domains and their stability. In this context, the adjustment in the molar composition of cations during the synthesis of hydrotalcites allows modulating the crystalline structure, as well as their textural and magnetic properties, offering precise control over the behavior of these materials in various applications.

4 Conclusions

Novel hydrotalcite-structured magnetic samples with 2 and 3 Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios have been directly assembled by coprecipitation, with Co2+, Ni2+, and Sr2+ incorporation. The adjustment in the molar composition of metal cations during the synthesis of hydrotalcites allows the modulation of the crystalline structure, as well as their textural and magnetic properties. XRD analysis confirmed the formation of hydrotalcite and the integration of Fe3O4 particles in the synthesized samples, with structural parameters validated by Rietveld refinement. The variation in the molar ratio of metal cations influences the interlamellar distance and crystallite size of Fe3O4, with a secondary SrCO3 phase observed in Sr2+ samples. The synthesis conditions affect the phase distribution, impacting the magnetic and catalytic properties of the composite material, and demonstrating an effective integration of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the hydrotalcite matrix. The characteristic functional groups of magnetic hydrotalcites with 2 and 3 Me2+/Me3+ molar ratios found were

Acknowledgments

E.N., G.S. and G.P.R. are grateful to CONICET (PIP 0111), UNLP (X941 - A 349), this work was also supported by MINCIENCIAS (Grant No 933-2023), and the Research Directorate of the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia for financial support.

-

Funding information: E.N., G.S., and G.P.R. are grateful to CONICET (PIP 0111), UNLP (X941 – A 349). This work was also supported by MINCIENCIAS (Grant No, 933-2023) and the Research Directorate of the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia for financial support.

-

Author contributions: Eliana Nope: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, visualization, writing – original draft, and review and editing. Gabriel Sathicq: writing – review and editing. José J. Martinez: methodology, writing – review and editing. Indry Milena Saavedra Gaona: formal analysis, visualization, and writing – original draft. Michael Castaneda Mendoza: formal analysis, visualization, and writing – original draft. Carlos Arturo Parra Vargas: resources, supervision, and writing – review and editing. Gustavo P. Romanelli: writing – review and editing. Rafael Luque: sources, visualization, and writing – review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Liu Z, Gao X, Liu B, Ma Q, Zhao T, Zhang J. Recent advances in thermal catalytic CO2 methanation on hydrotalcite-derived catalysts. Fuel. 2022;321:124115.10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124115Search in Google Scholar

[2] Gu Z, Atherton JJ, Xu ZP. Hierarchical layered double hydroxide nanocomposites: Structure, synthesis and applications. Chem Commun. 2015;51:3024–36.10.1039/C4CC07715FSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Bernard E, Zucha WJ, Lothenbach B, Mäder U. Stability of hydrotalcite (Mg-Al layered double hydroxide) in presence of different anions. Cem Concr Res. 2022;152:106674.10.1016/j.cemconres.2021.106674Search in Google Scholar

[4] Simeonidis K, Kaprara E, Rivera-Gil P, Xu R, Teran FJ, Kokkinos E, et al. Hydrotalcite-embedded magnetite nanoparticles for hyperthermia-triggered chemotherapy. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:1796.10.3390/nano11071796Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Zhu B, Chen L, Yan T, Xu J, Wang Y, Chen M, et al. Fabrication of Fe3O4/MgAl-layered double hydroxide magnetic composites for the effective removal of Orange II from wastewater. Water Sci Technol. 2018;78:1179–88.10.2166/wst.2018.388Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Shaw R, Kumar A. Hydrotalcite-based catalysts for 1,4-conjugate addition in organic synthesis. Catal Sci Technol. 2024;14:2090–104.10.1039/D3CY01685DSearch in Google Scholar

[7] Maggetti C, Pinelli D, Di Federico V, Sisti L, Tabanelli T, Cavani F, et al. Development and validation of an adsorption process for phosphate removal and recovery from municipal wastewater based on hydrotalcite-related materials. Sci Total Environ. 2024;951:175509.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175509Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Ur Rehman M, Yin R, Yang Z-D, Zhang G, Liu Y, Zhang FM, et al. Fabrication and modification of hydrotalcite-based photocatalysts and their composites for CO2 reduction: A critical review. ChemSusChem. 2025;18(10):e202402333.10.1002/cssc.202402333Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Jin W, Lee D, Jeon Y, Park DH. Biocompatible hydrotalcite nanohybrids for medical functions. Minerals. 2020;10:172.10.3390/min10020172Search in Google Scholar

[10] Burange AS, Gopinath CS. Catalytic applications of hydrotalcite and related materials in multi -component reactions: Concepts, challenges and future scope. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2021;22:100458.10.1016/j.scp.2021.100458Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bi X, Fan T, Zhang H. Novel morphology-controlled hierarchical core@shell structural organo-layered double hydroxides magnetic nanovehicles for drug release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:20498–509.10.1021/am506113sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Colombo M, Carregal-Romero S, Casula MF, Gutiérrez L, Morales MP, Böhm IB, et al. Biological applications of magnetic nanoparticles. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:4306–34.10.1039/c2cs15337hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Qureshi AA, Javed S, Javed HMA, Akram A, Mustafa MS, Ali U, et al. Facile formation of SnO2–TiO2 based photoanode and Fe3O4@rGO based counter electrode for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2021;123:105545. 10.1016/j.mssp.2020.105545.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Albalawi AE, Khalaf AK, Alyousif MS, Alanazi AD, Baharvand P, Shakibaie M, et al. Fe3O4@piroctone olamine magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesize and therapeutic potential in cutaneous leishmaniasis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139:111566.10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111566Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Anbarani MZ, Ramavandi B, Bonyadi Z. Modification of Chlorella vulgaris carbon with Fe3O4 nanoparticles for tetracycline elimination from aqueous media. Heliyon. 2023;9:e14356.10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14356Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Baladi M, Amiri M, Salavati-Niasari M. Green sol–gel auto-combustion synthesis, characterization and study of cytotoxicity and anticancer activity of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite. Arab J Chem. 2023;16:104575.10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104575Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hasan G, Mohammed H, Althamthami M, et al. Synergistic effect of novel biosynthesis SnO2@Fe3O4 nanocomposite: A comprehensive study of its photocatalytic of Dyes & antibiotics, antibacterial, and antimutagenic activities. J Photochem Photobiol A: Chem. 2023;443:114874. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2023.114874.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Shao M, Ning F, Zhao J, Wei M, Evans DG, Duan X. Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2@layered double hydroxide core-shell microspheres for magnetic separation of proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1071–7.10.1021/ja2086323Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Huang Y, Mu G, Huan W, Yang Y, Yuan H, Batool I, et al. Degradation of TeCG catalyzed by graphene quantum Dot-reconstituted magnetic hydrotalcite composites. Chem Eng J. 2025;507:160749.10.1016/j.cej.2025.160749Search in Google Scholar

[20] Hu L, Li Z, Huang X, Zhu J, Hussaini I, He J, et al. Enhanced adsorption performance of modified hydrotalcite with CuO for nitrate in wastewater. J Electron Mater. 2025;54:2167–79.10.1007/s11664-024-11696-4Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chen X, Mi F, Zhang H, Zhang H. Facile synthesis of a novel magnetic core-shell hierarchical composite submicrospheres Fe3O4@CuNiAl-LDH under ambient conditions. Mater Lett. 2012;69:48–51.10.1016/j.matlet.2011.11.052Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang H, Zhang G, Bi X, Chen X. Facile assembly of a hierarchical core@shell Fe3O4@CuMgAl-LDH (layered double hydroxide) magnetic nanocatalyst for the hydroxylation of phenol. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1:5934–42.10.1039/c3ta10349hSearch in Google Scholar

[23] Nope E, Sathicq ÁG, Martínez JJ, Rojas HA, Luque R, Romanelli GP. Ternary hydrotalcites in the multicomponent synthesis of 4H-Pyrans. Catalysts. 2020;10:70.10.3390/catal10010070Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kang YS, Risbud S, Rabolt JF, Stroeve P. Synthesis and characterization of nanometer-size Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3 particles. Chem Mater. 1996;8:2209–11.10.1021/cm960157jSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Niculescu A-G, Chircov C, Grumezescu AM. Magnetite nanoparticles: Synthesis methods – A comparative review. Methods. 2022;199:16–27.10.1016/j.ymeth.2021.04.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Dudchenko N, Pawar S, Perelshtein I, Fixler D. Magnetite nanoparticles: Synthesis and applications in optics and nanophotonics. Materials. 2022;15:2601.10.3390/ma15072601Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Nope E, Sathicq ÁG, Martínez JJ, ALOthman ZA, Romanelli GP, Nares EM, et al. Revisiting hydrotalcite synthesis: Efficient combined mechanochemical/coprecipitation synthesis to design advanced tunable basic catalysts. Nanotechnol Rev. 2024;13(1):20240042. 10.1515/ntrev-2024-0042.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Jurišová J, Danielik V, Malečková S, Guzikiewiczová E, Králik M, Vizárová K, et al. Preparation and characterisation of hydrotalcites colloid dispersions suitable for deacidification of paper information carriers. Chem Pap. 2024;78:1719–30.10.1007/s11696-023-03200-9Search in Google Scholar

[29] Nagarjuna R, Challagulla S, Sahu P, Roy S, Ganesan R. Polymerizable sol–gel synthesis of nano-crystalline WO3 and its photocatalytic Cr(VI) reduction under visible light. Adv Powder Technol. 2017;28(12):3265–73. 10.1016/j.apt.2017.09.030.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Elías VR, Sabre EV, Winkler EL, Casuscelli SG, Eimer GA. On the nature of Cr species on MCM-41 obtained by a one step method and their enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible radiation: New insights by a combined techniques approach. Appl Catal A: Gen. 2013;467:363–70.10.1016/j.apcata.2013.07.059Search in Google Scholar

[31] Salimi M, Zamanpour A. Ag nanoparticle immobilized on functionalized magnetic hydrotalcite (Fe3O4/HT-SH-Ag) for clean oxidation of alcohols with TBHP. Inorg Chem Commun. 2020;119:108081.10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108081Search in Google Scholar

[32] Salimi M, Esmaeli-nasrabadi F, Sandaroos R. Fe3O4@Hydrotalcite-NH2-CoII NPs: A novel and extremely effective heterogeneous magnetic nanocatalyst for synthesis of the 1-substituted 1H-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrazoles. Inorg Chem Commun. 2020;122:108287.10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108287Search in Google Scholar

[33] Monshi A, Foroughi MR, Monshi MR. Modified Scherrer equation to estimate more accurately nano-crystallite size using XRD. World J Nano Sci Eng. 2012;2:154–60.10.4236/wjnse.2012.23020Search in Google Scholar

[34] Mustapha S, Ndamitso MM, Abdulkareem AS, Tijani JO, Shuaib DT, Mohammed AK, et al. Comparative study of crystallite size using Williamson-Hall and Debye-Scherrer plots for ZnO nanoparticles. Adv Nat Sci: Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2019;10:045013.10.1088/2043-6254/ab52f7Search in Google Scholar

[35] Saavedra Gaona IM, Mendoza MC, Vargas CAP. Structural and magnetic properties of Nd3Ba5Cu8O18 + ẟ superconductor. J Low Temp Phys. 2023;211:156–65.10.1007/s10909-023-02963-5Search in Google Scholar

[36] Saavedra Gaona IM, Supelano GI, Suarez Vera SG, Fonseca LCI, Castaneda Mendoza M, Sánchez Saenz CL, et al. Magnetic and electrical behaviour of Yb substitution on Bi1-xYbxFeO3 (0.00 < x < 0.06) ceramic system. J Magn Magn Mater. 2024;593:171827.10.1016/j.jmmm.2024.171827Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ros FC. Rietveld refinement strategy of CaTa4-xNbxO11 solid solutions using GSAS-EXPGUI software package. Mater Sci Forum. 2017;888:167–71.10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.888.167Search in Google Scholar

[38] Murugesan S, Thirumurugesan R, Mohandas E, Parameswaran P. X-ray diffraction Rietveld analysis and Bond Valence analysis of nano titania containing oxygen vacancies synthesized via sol-gel route. Mater Chem Phys. 2019;225:320–30.10.1016/j.matchemphys.2018.12.061Search in Google Scholar

[39] Cuervo Farfán JA. Producción y propiedades físicas de nuevas perovskitas complejas del tipo RAMOX (R = La, Nd, Sm, Eu; A = Sr, Bi; M = Ti, Mn, Fe). PhD thesis. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/handle/unal/79915. (2021, accessed 15 August 2024).Search in Google Scholar

[40] Naranjo CEE, Hernandez JST, Salgado MJR, Tabares JA, Maccari F, Cortes A, et al. Processing and characterization of Nd2Fe14B microparticles prepared by surfactant-assisted ball milling. Appl Phys A. 2018;124:564.10.1007/s00339-018-1977-7Search in Google Scholar

[41] Abd-Elnaiem AM, Hakamy A, Afify N, Omer M, Abdelbaki RF. Nanoarchitectonics of zinc nickel ferrites by the hydrothermal method for improved structural and magnetic properties. J Alloy Compd. 2024;984:173941.10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.173941Search in Google Scholar

[42] Sharma SK, Kushwaha PK, Srivastava VK, Bhatt SD, Jasra RV. Effect of hydrothermal conditions on structural and textural properties of synthetic hydrotalcites of varying Mg/Al ratio. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2007;46:4856–65.10.1021/ie061438wSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Kloprogge JT, Frost RL. Fourier transform infrared and Raman spectroscopic study of the local structure of Mg-, Ni-, and Co-hydrotalcites. J Solid State Chem Fr. 1999;146:506–15.10.1006/jssc.1999.8413Search in Google Scholar

[44] Julianti NK, Wardani TK, Gunardi I. Effect of calcination at synthesis of Mg-Al hydrotalcite using co-precipitation method. J Pure Appl Chem Res. 2017;6:7–13.10.21776/ub.jpacr.2017.006.01.280Search in Google Scholar

[45] Mehta K, Jha MK, Divya N. Statistical optimization of biodiesel production from Prunus armeniaca oil over strontium functionalized calcium oxide. Res Chem Intermed. 2018;44:7691–709.10.1007/s11164-018-3581-zSearch in Google Scholar

[46] Yan Q, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Umar A, Guo Z, O'Hare D, et al. Hierarchical Fe3O4 core–shell layered double hydroxide composites as magnetic adsorbents for anionic dye removal from wastewater. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2015;2015:4182–91.10.1002/ejic.201500650Search in Google Scholar

[47] Zhang Y, Niu S, Han K, Li Y, Lu C. Synthesis of the SrO–CaO–Al2O3 trimetallic oxide catalyst for transesterification to produce biodiesel. Renew Energy. 2021;168:981–90.10.1016/j.renene.2020.12.132Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ikram M, Haider A, Imran M, Haider J, Naz S, Ul-Hamid A, et al. Facile synthesis of starch and tellurium doped SrO nanocomposite for catalytic and antibacterial potential: In silico molecular docking studies. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;221:496–507.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.034Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Wu Q, Olafsen A, Vistad ØB, Roots J, Norby P. Delamination and restacking of a layered double hydroxide with nitrate as counter anion. J Mater Chem. 2005;15:4695–700.10.1039/b511184fSearch in Google Scholar

[50] Yan LG, Yang K, Shan RR, Yan T, Wei J, Yu SJ, et al. Kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic investigations of phosphate adsorption onto core-shell Fe₃O₄@LDHs composites with easy magnetic separation assistance. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;448:508–16.10.1016/j.jcis.2015.02.048Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Thongtem T, Tipcompor N, Phuruangrat A, Thongtem S. Characterization of SrCO3 and BaCO3 nanoparticles synthesized by sonochemical method. Mater Lett. 2010;64:510–2.10.1016/j.matlet.2009.11.060Search in Google Scholar

[52] Aisawa S, Hirahara H, Uchiyama H, Takahashi S, Narita E. Synthesis and thermal decomposition of Mn–Al layered double hydroxides. J Solid State Chem. 2002;167:152–9.10.1006/jssc.2002.9637Search in Google Scholar

[53] Wiyantoko B, Kurniawati P, Purbaningtias TE, Fatimah I. Synthesis and characterization of hydrotalcite at different Mg/Al molar ratios. Procedia Chem. 2015;17:21–6.10.1016/j.proche.2015.12.115Search in Google Scholar

[54] Shekoohi K, Hosseini FS, Haghighi AH, Sahrayian A. Synthesis of some Mg/Co-Al type nano hydrotalcites and characterization. Methods X. 2017;4:86–94.10.1016/j.mex.2017.01.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Durgalakshmi D, Ajay Rakkesh R, Kamil S, Karthikeyan S, Balakumar S. Rapid dilapidation of alcohol using magnesium oxide and magnesium aspartate based nanostructures: A Raman spectroscopic and molecular simulation approach. J Inorg Organomet Polym. 2019;29:1390–9.10.1007/s10904-019-01105-3Search in Google Scholar

[56] Gao G, Zhu Z, Zheng J, Liu Z, Wang Q, Yan Y. Ultrathin magnetic Mg-Al LDH photocatalyst for enhanced CO2 reduction: Fabrication and mechanism. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;555:1–10.10.1016/j.jcis.2019.07.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[57] Karthikeyan C, Karuppuchamy S. Transesterification of Madhuca longifolia derived oil to biodiesel using Mg–Al hydrotalcite as heterogeneous solid base catalyst. Mater Focus. 2017;6:101–6.10.1166/mat.2017.1387Search in Google Scholar

[58] Szymaszek-Wawryca A, Summa P, Duraczyńska D, Díaz U, Motak M. Hydrotalcite-modified clinoptilolite as the catalyst for selective catalytic reduction of NO with ammonia (NH3-SCR). Materials. 2022;15:7884.10.3390/ma15227884Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Galindo R, López-Delgado A, Padilla I, Yates M. Synthesis and characterisation of hydrotalcites produced by an aluminium hazardous waste: A comparison between the use of ammonia and the use of triethanolamine. Appl Clay Sci. 2015;115:115–23.10.1016/j.clay.2015.07.032Search in Google Scholar

[60] Shafi KVPM, Gedanken A, Prozorov R, Balogh J. Sonochemical preparation and size-dependent properties of nanostructured CoFe2O4 particles. Chem Mater. 1998;10:3445–50.10.1021/cm980182kSearch in Google Scholar

[61] Stamate A-E. Layered double hydroxide-based catalysts for fine organic synthesis. Phd thesis. University of Bucharest; Doctoral School in Chemistry. https://theses.hal.science/tel-03906532. (2022, accessed 11 February 2025).Search in Google Scholar

[62] Baños JGC, Lara VEN, Puentes CO. Magnetita (Fe3O4): Una estructura inorgánica con múltiples aplicaciones en catálisis heterogénea. Rev Colomb Quím. 2017;46:42–59.10.15446/rev.colomb.quim.v46n1.62831Search in Google Scholar

[63] Yang Sun(孙洋) RL. Impact of Co2+ substitution on structure and magnetic properties of M-type strontium ferrite with different Fe/Sr ratios. Chin Phys B. 2024;33:107506.10.1088/1674-1056/ad6554Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing

- Thermal and stability analysis of silver–water nanofluid flow over unsteady stretching sheet under the influence of heat generation/absorption at the boundary

- Cobalt iron oxide-infused silicone nanocomposites: Magnetoactive materials for remote actuation and sensing

- Magnesium-reinforced PMMA composite scaffolds: Synthesis, characterization, and 3D printing via stereolithography

- Bayesian inference-based physics-informed neural network for performance study of hybrid nanofluids

- Numerical simulation of non-Newtonian hybrid nanofluid flow subject to a heterogeneous/homogeneous chemical reaction over a Riga surface

- Enhancing the superhydrophobicity, UV-resistance, and antifungal properties of natural wood surfaces via in situ formation of ZnO, TiO2, and SiO2 particles

- Synthesis and electrochemical characterization of iron oxide/poly(2-methylaniline) nanohybrids for supercapacitor application

- Impacts of double stratification on thermally radiative third-grade nanofluid flow on elongating cylinder with homogeneous/heterogeneous reactions by implementing machine learning approach

- Synthesis of Cu4O3 nanoparticles using pumpkin seed extract: Optimization, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity studies

- Cationic charge influence on the magnetic response of the Fe3O4–[Me2+ 1−y Me3+ y (OH2)] y+(Co3 2−) y/2·mH2O hydrotalcite system

- Pressure sensing intelligent martial arts short soldier combat protection system based on conjugated polymer nanocomposite materials

- Magnetohydrodynamics heat transfer rate under inclined buoyancy force for nano and dusty fluids: Response surface optimization for the thermal transport

- Fly ash and nano-graphene enhanced stabilization of engine oil-contaminated soils

- Enhancing natural fiber-reinforced biopolymer composites with graphene nanoplatelets: Mechanical, morphological, and thermal properties

- Performance evaluation of dual-scale strengthened co-bonded single-lap joints using carbon nanotubes and Z-pins with ANN

- Computational works of blood flow with dust particles and partially ionized containing tiny particles on a moving wedge: Applications of nanotechnology

- Hybridization of biocomposites with oil palm cellulose nanofibrils/graphene nanoplatelets reinforcement in green epoxy: A study of physical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties

- Design and preparation of micro-nano dual-scale particle-reinforced Cu–Al–V alloy: Research on the aluminothermic reduction process

- Spectral quasi-linearization and response optimization on magnetohydrodynamic flow via stenosed artery with hybrid and ternary solid nanoparticles: Support vector machine learning

- Ferrite/curcumin hybrid nanocomposite formulation: Physicochemical characterization, anticancer activity, and apoptotic and cell cycle analyses in skin cancer cells

- Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of Tamoxifen against breast cancer using extra virgin olive oil-based nanoemulsion delivery system

- A titanium oxide- and silver-based hybrid nanofluid flow between two Riga walls that converge and diverge through a machine-learning approach

- Enhancing convective heat transfer mechanisms through the rheological analysis of Casson nanofluid flow towards a stagnation point over an electro-magnetized surface

- Intrinsic self-sensing cementitious composites with hybrid nanofillers exhibiting excellent piezoresistivity

- Research on mechanical properties and sulfate erosion resistance of nano-reinforced coal gangue based geopolymer concrete

- Impact of surface and configurational features of chemically synthesized chains of Ni nanostars on the magnetization reversal process

- Porous sponge-like AsOI/poly(2-aminobenzene-1-thiol) nanocomposite photocathode for hydrogen production from artificial and natural seawater

- Multifaceted insights into WO3 nanoparticle-coupled antibiotics to modulate resistance in enteric pathogens of Houbara bustard birds

- Synthesis of sericin-coated silver nanoparticles and their applications for the anti-bacterial finishing of cotton fabric

- Enhancing chloride resistance of freeze–thaw affected concrete through innovative nanomaterial–polymer hybrid cementitious coating

- Development and performance evaluation of green aluminium metal matrix composites reinforced with graphene nanopowder and marble dust

- Morphological, physical, thermal, and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced arrowroot starch composites

- Influence of the graphene oxide nanosheet on tensile behavior and failure characteristics of the cement composites after high-temperature treatment

- Central composite design modeling in optimizing heat transfer rate in the dissipative and reactive dynamics of viscoplastic nanomaterials deploying Joule and heat generation aspects

- Double diffusion of nano-enhanced phase change materials in connected porous channels: A hybrid ISPH-XGBoost approach

- Synergistic impacts of Thompson–Troian slip, Stefan blowing, and nonuniform heat generation on Casson nanofluid dynamics through a porous medium

- Optimization of abrasive water jet machining parameters for basalt fiber/SiO2 nanofiller reinforced composites

- Enhancing aesthetic durability of Zisha teapots via TiO2 nanoparticle surface modification: A study on self-cleaning, antimicrobial, and mechanical properties

- Nanocellulose solution based on iron(iii) sodium tartrate complexes

- Combating multidrug-resistant infections: Gold nanoparticles–chitosan–papain-integrated dual-action nanoplatform for enhanced antibacterial activity

- Novel royal jelly-mediated green synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their multifunctional biological activities

- Direct bandgap transition for emission in GeSn nanowires

- Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with different morphologies using a microwave-based method and their antimicrobial activity

- Numerical investigation of convective heat and mass transfer in a trapezoidal cavity filled with ternary hybrid nanofluid and a central obstacle

- Halloysite nanotube enhanced polyurethane nanocomposites for advanced electroinsulating applications

- Low molar mass ionic liquid’s modified carbon nanotubes and its role in PVDF crystalline stress generation

- Green synthesis of polydopamine-functionalized silver nanoparticles conjugated with Ceftazidime: in silico and experimental approach for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria and reducing toxicity

- Evaluating the influence of graphene nano powder inclusion on mechanical, vibrational and water absorption behaviour of ramie/abaca hybrid composites

- Dynamic-behavior of Casson-type hybrid nanofluids due to a stretching sheet under the coupled impacts of boundary slip and reaction-diffusion processes

- Influence of polyvinyl alcohol on the physicochemical and self-sensing properties of nano carbon black reinforced cement mortar

- Advanced machine learning approaches for predicting compressive and flexural strength of carbon nanotube–reinforced cement composites: a comparative study and model interpretability analysis

- Review Articles

- A comprehensive review on hybrid plasmonic waveguides: Structures, applications, challenges, and future perspectives

- Nanoparticles in low-temperature preservation of biological systems of animal origin

- Fluorescent sulfur quantum dots for environmental monitoring

- Nanoscience systematic review methodology standardization

- Nanotechnology revolutionizing osteosarcoma treatment: Advances in targeted kinase inhibitors

- AFM: An important enabling technology for 2D materials and devices

- Carbon and 2D nanomaterial smart hydrogels for therapeutic applications

- Principles, applications and future prospects in photodegradation systems

- Do gold nanoparticles consistently benefit crop plants under both non-stressed and abiotic stress conditions?

- An updated overview of nanoparticle-induced cardiovascular toxicity

- Arginine as a promising amino acid for functionalized nanosystems: Innovations, challenges, and future directions

- Advancements in the use of cancer nanovaccines: Comprehensive insights with focus on lung and colon cancer

- Membrane-based biomimetic delivery systems for glioblastoma multiforme therapy

- The drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles for spinal cord injury repair

- Green synthesis, biomedical effects, and future trends of Ag/ZnO bimetallic nanoparticles: An update

- Application of magnesium and its compounds in biomaterials for nerve injury repair

- Micro/nanomotors in biomedicine: Construction and applications

- Hydrothermal synthesis of biomass-derived CQDs: Advances and applications

- Research progress in 3D bioprinting of skin: Challenges and opportunities

- Review on bio-selenium nanoparticles: Synthesis, protocols, and applications in biomedical processes

- Gold nanocrystals and nanorods functionalized with protein and polymeric ligands for environmental, energy storage, and diagnostic applications: A review

- An in-depth analysis of rotational and non-rotational piezoelectric energy harvesting beams: A comprehensive review

- Advancements in perovskite/CIGS tandem solar cells: Material synergies, device configurations, and economic viability for sustainable energy

- Deep learning in-depth analysis of crystal graph convolutional neural networks: A new era in materials discovery and its applications

- Review of recent nano TiO2 film coating methods, assessment techniques, and key problems for scaleup

- Antioxidant quantum dots for spinal cord injuries: A review on advancing neuroprotection and regeneration in neurological disorders

- Rise of polycatecholamine ultrathin films: From synthesis to smart applications

- Advancing microencapsulation strategies for bioactive compounds: Enhancing stability, bioavailability, and controlled release in food applications

- Advances in the design and manipulation of self-assembling peptide and protein nanostructures for biomedical applications

- Photocatalytic pervious concrete systems: from classic photocatalysis to luminescent photocatalysis

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Synthesis and characterization of smart stimuli-responsive herbal drug-encapsulated nanoniosome particles for efficient treatment of breast cancer”

- Special Issue on Advanced Nanomaterials for Carbon Capture, Environment and Utilization for Energy Sustainability - Part III

- Efficiency optimization of quantum dot photovoltaic cell by solar thermophotovoltaic system

- Exploring the diverse nanomaterials employed in dental prosthesis and implant techniques: An overview

- Electrochemical investigation of bismuth-doped anode materials for low‑temperature solid oxide fuel cells with boosted voltage using a DC-DC voltage converter

- Synthesis of HfSe2 and CuHfSe2 crystalline materials using the chemical vapor transport method and their applications in supercapacitor energy storage devices

- Special Issue on Green Nanotechnology and Nano-materials for Environment Sustainability

- Influence of nano-silica and nano-ferrite particles on mechanical and durability of sustainable concrete: A review

- Surfaces and interfaces analysis on different carboxymethylation reaction time of anionic cellulose nanoparticles derived from oil palm biomass

- Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

- Retraction

- Retraction of “Aging assessment of silicone rubber materials under corona discharge accompanied by humidity and UV radiation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MHD radiative mixed convective flow of a sodium alginate-based hybrid nanofluid over a convectively heated extending sheet with Joule heating

- Experimental study of mortar incorporating nano-magnetite on engineering performance and radiation shielding

- Multicriteria-based optimization and multi-variable non-linear regression analysis of concrete containing blends of nano date palm ash and eggshell powder as cementitious materials

- A promising Ag2S/poly-2-amino-1-mercaptobenzene open-top spherical core–shell nanocomposite for optoelectronic devices: A one-pot technique

- Biogenic synthesized selenium nanoparticles combined chitosan nanoparticles controlled lung cancer growth via ROS generation and mitochondrial damage pathway

- Fabrication of PDMS nano-mold by deposition casting method

- Stimulus-responsive gradient hydrogel micro-actuators fabricated by two-photon polymerization-based 4D printing

- Physical aspects of radiative Carreau nanofluid flow with motile microorganisms movement under yield stress via oblique penetrable wedge

- Effect of polar functional groups on the hydrophobicity of carbon nanotubes-bacterial cellulose nanocomposite

- Review in green synthesis mechanisms, application, and future prospects for Garcinia mangostana L. (mangosteen)-derived nanoparticles

- Entropy generation and heat transfer in nonlinear Buoyancy–driven Darcy–Forchheimer hybrid nanofluids with activation energy

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ginkgo biloba seed extract: Evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial activities

- A numerical analysis of heat and mass transfer in water-based hybrid nanofluid flow containing copper and alumina nanoparticles over an extending sheet

- Investigating the behaviour of electro-magneto-hydrodynamic Carreau nanofluid flow with slip effects over a stretching cylinder

- Electrospun thermoplastic polyurethane/nano-Ag-coated clear aligners for the inhibition of Streptococcus mutans and oral biofilm

- Investigation of the optoelectronic properties of a novel polypyrrole-multi-well carbon nanotubes/titanium oxide/aluminum oxide/p-silicon heterojunction

- Novel photothermal magnetic Janus membranes suitable for solar water desalination

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ageratum conyzoides for activated carbon compositing to prepare antimicrobial cotton fabric

- Activation energy and Coriolis force impact on three-dimensional dusty nanofluid flow containing gyrotactic microorganisms: Machine learning and numerical approach

- Machine learning analysis of thermo-bioconvection in a micropolar hybrid nanofluid-filled square cavity with oxytactic microorganisms

- Research and improvement of mechanical properties of cement nanocomposites for well cementing