Processing and effective utilization of lignocellulosic biomass: Nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

-

Nibedita Dey

, Ramesh Malarvizhi Dhaswini

and Maximilian Lackner

Abstract

Nanotechnology has proven to make the processing of lignocellulosic biomass much easier and efficient by reducing potential complications and harmful side effects. The overall cost of operations, transport, and disposal has also been reduced. Recovery, reusability, and purification of lignocellulosic biomass are found to be efficient when nanotechnological approaches are employed. Lignocellulosic biomass for enhancing the quality of water has attracted increasing interest among many researchers. Nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass include nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan. Heavy metal removal by nanocellulose has been reported to exhibit an efficiency of 99% against copper and iron metals. Membranes consisting of nanocellulose crystals extracted from shrimp shell wastes can eliminate Victoria blue dye by 98%. Escherichia coli has been treated successfully using nanocellulose composites conjugated with silver with 96.9% efficiency. Nano-lignin particles have reported 98% removal of methylene blue, while a composite of the same with palladium and iron oxide has exhibited 99% elimination of the toxic dye. Lignin-based nanomaterials are suggested to be reproducible and regenerated by heat and squeeze treatments, thus releasing the entire adsorbed contaminants to free the substrate for subsequent use. Further carbonation maximizes the absorption by 522 times more than its own weight, with a removal efficiency of 96%. Nanotization of lignocellulosic biomass gives enhanced mechanical, chemical, and biological properties that aid researchers to modify these woody polymers into membranes, flocculants, dye adsorbents, metal adsorbents, and oil separators in wastewater treatment. The present review deals with potential applications of nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass for wastewater remediation.

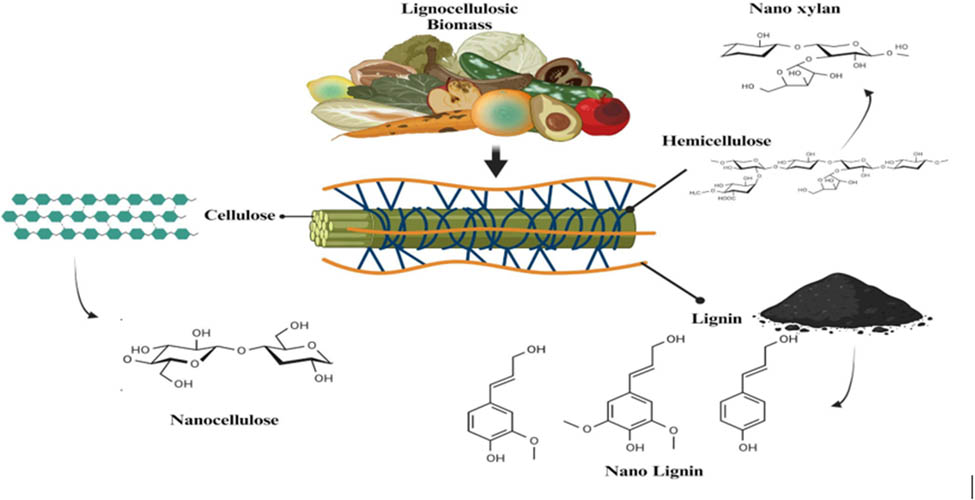

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The population has drastically increased over the past few decades due to advancements in medicine and healthcare. Industrialization has also boomed to provide a better quality of life to people. Extensive use of water for daily and commercial purposes has led to many problems pertaining to wastewater management and resource procurement [1]. Around 600 million people around the world do not have access to clean water for their needs [2]. Major contaminants found in wastewater are metal ions, anions, dyes, pesticides, phenols, detergents, pathogens, and humic matter [3]. These toxins are fatal to all living beings and the environment as a whole. Overall, ecological equilibrium is also disturbed due to the accumulation of toxins inside the food chain through water sources [4]. Conventional methods for remediation of wastewater involve processes like filtration (membrane), electrodialysis, precipitation (chemical), reverse osmosis, ion exchange, ultraviolet treatment, and ozonation [5]. The efficiency of these techniques has been proven previously in the literature, but they are expensive, tedious, time-dependent, and produce a humongous number of byproducts in the form of sludge. Disposal of secondary sludge and wastes is also of great concern. Hence, sustainable, economical, and eco-friendly alternatives are necessary to improve the quality of wastewater. Nanomaterials have been used to improve the quality of water due to their high surface-to-volume ratio. Rapid kinetics, higher affinity, lower costs, low maintenance, and targeted action, as well as mode of delivery, are key features of nanomaterials [6]. Agricultural wastes have been used for treating contaminants in effluent waters. Wastes like peels of pomegranate, orange, and jackfruit, when reduced to the nanorange, have been reported as good adsorbents of contaminants from wastewater. Cellulose is one of the main natural polymers that seems to have a major share in this remediation activity [7]. Lignocellulosic biomass is the treated or decomposed mass of wood. It consists of lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose as main ingredients. Conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into treated valuable products reduces pollution and conserves the environment [8]. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass involves approaches that are physical, biological, and chemical in nature [9]. Sugars are released by hydrolysis, which gives many value-added commodities that are quite specific to the microorganism used [10]. Nonfood-based lignocellulosic biomass in the form of residues (organic), feedstocks, wastes (inorganic), and inedible byproducts can be used as adsorbents for many contaminants [11]. Around tonnes of unused lignocellulosic biomass are produced as commercial waste, which can be reused in wastewater treatment and bioremediation. Thus, lignocellulosic biomass for enhancing the quality of water has attracted increasing interest among many researchers.

Cellulose contains a network of β-glycosidic linkages that join glucose units together to form a long polymer. In nature, they are bundled up to exhibit a microfibril structure. Adjacent to cellulose lies hemicellulose that fills up the intermediate portion of lignocellulosic biomass. This consists of units of galactose, arabinose, mannose, and xylose. They form a branched structure of heterogeneous nature [10]. Xylose consists of xylans, mannans constitute mannose, xyloglucans form arabinose, and galactans make up galactose. Dylan is found predominantly in hardwood and glucomannan in softwood. Lignin surrounds the outermost covering of lignocellulosic biomass. Based on availability, they stand second in line after cellulose. They are responsible for the defensive coating and protection in plants. Shielding from biological and physical attacks is rendered by lignin to the plant [9]. The backbone of lignin is its hydroxyphenyl units and different types of phenylpropanoid moieties. Syringyl as well as guaiacyl units are the most predominant phenylpropanoid moieties found in lignin [12]. However, the presence of these complex groups makes the processing of lignin quite burdensome. Enzymes and microbial strains used for pretreatment are deactivated by lignin monomers as well as hinder the digestion of hemicellulose and cellulose moieties [13]. Common sources of lignin are cobs of corn, bagasse of sugarcane, wheat straw, and stickers. Direct and conventional treatment of lignocellulosic biomass generates large amounts of waste that are toxic [14]. Hence, sustainable, newer, and better techniques have been experimented with to treat lignocellulosic biomass in an economical and environmentally friendly way.

Nanotechnology has proven to make the processing of lignocellulosic biomass much easier and efficient by reducing the complications and harmful side effects. The overall cost of operations, transport, and disposal has also been reduced. Valuable products from lignin and hemicellulose, which are tedious to treat, have also been reported [10]. Particles ranging from 100 to 500 nm have been used to enhance pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass by reducing the activation energies of enzymes, favoring cellular penetration, breaking bonds with substrates, rendering stability at elevated temperatures, and increasing the reaction surface area [15]. Physical and molecular characteristics of lignocellulosic biomass are improved when reduced to the nanorange. Recovery, reusability, and purification of lignocellulosic biomass are found to be efficient when nanotechnological approaches are used for the same [16]. Rewetting as well as drying of wood is improved by nanotechniques. This conserves energy and makes customization of value-added products easier [17]. Nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass include nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan. The present review deals with potential applications of nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass for wastewater remediation. Figure 1 shows the potential sources and components that form the precursor base for the synthesis of lignocellulosic nanomaterials [18,19].

2 Nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass

Extraction of nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass involves two crucial steps: pretreatment and extraction. Pretreatment generally removes non-cellulosic components, hence paving the way to extract nanocellulose alone [20,21]. Pretreatment techniques like hydrolysis by enzymes, carboxylation, oxidation using catalysts like 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxy (TEMPO), and refining by mechanical methods remove lignin and hemicellulose moieties from lignocellulosic biomass. General techniques involve acid hydrolysis, TEMPO oxidation, ammonium persulphate oxidation, ball milling, homogenization, ultrasonication, microfluidization, shear grinding, and cryo crushing. Acid and alkaline chemical treatments eliminate the amorphous region of cellulose while retaining the crystalline nanostructures of the same [22]. TEMPO oxidation lowers the energy required for mechanical processing. Extraction processes used to derive nanocellulose for wastewater remediation are discussed in the following sections. Heteropolymer lignin is made up of monomeric units of methoxylated phenylpropylene alcohol. These units are connected by stable ether and ester bonds, forming aromatic structures [23]. Alcohol mixtures in lignin are p-coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl [24]. Pretreatment for nanolignin yields different precursor forms of lignins like lignosulfonate, kraft, organosolv, and alkaline lignin. Extraction processes include treatment using acids like acetic acid, peroxyformic acid, peroxyacetic acid, and bleaching [25]. Nanoxylan requires specific alkaline treatment of hemicellulose with tedious membrane separation. Hence, nanoxylan has not been explored much in the field of remediation as its processing is still not scaled up to an industry level. Precursor sources used to derive nanocellulose, nanolignin, and nanoxylan are industrial and food wastes, which in itself is a form of remediation. This reduces the sludge load of one industry, which is processed to remediate wastewaters and is biodegradable that finally assimilates itself in nature where it belongs. Nanoderivatives of lignocellulosic biomass are very sustainable when compared to fabricated nanoderivatives of other substances and compounds. Potential hazards of metal. Polymer and ceramic-based nanomaterials are not found in nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass as they are biodegradable and organic.

Aqueous stability of nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass is quite essential when it comes to wastewater treatment. Water and nanocellulose have multiple phenomena overlapping, like condensation, diffusion, hydration, and wetting. These processes are mediated by electrostatic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals interactions. These interactions make nanocellulose hygroscopic. Colloidal stability is attributed to nanocellulose due to its surface charge density, electrostatic repulsion, and steric stability of neutral polymers [26]. Similarly, nanoxylan has also been reported to be quite stable in aqueous medium. They are insoluble in water. Their nanosize provides the high porosity and surface charge that aids them in forming stable emulsions with oil. It is not always crystalline, thus making it more crystalline is a prerequisite to the production of stable nanoxylan with good colloidal stability [27]. Modified nanolignin shows stable colloidal dispersion due to the cross-linking reaction. The predominant 97% biobased composition makes it tunable to achieve the desired size and structure with good stability in aqueous media. Stability has been seen in varying pH of 3–12 and a variety of organic solvents like ethanol, acetone, tetrahydrofuran, and dimethylformamide. Free hydroxyl and phenolic groups in nanolignin provide efficient reduction sites for metal ions, forming hybrids and complexes. Base-catalyzed reactions can also be employed on nanolignin by cationic epoxides that render it redispersion and pH-dependent agglomeration properties. High pH and structural stability of nanolignin make it a good candidate for covalent surface functionalization in an aqueous state [28].

3 Nanocellulose forms and sources

Nanocellulose is derived from natural degradation by microorganisms and ecosystems [9]. Its commercial application is utilization in packaging, hygiene, dietary, and medical materials for their enhanced barrier properties [29]. Nanocellulose is found in forms like nanocrystals, beads, fibrils, and hydrogels. These physical characteristics majorly depend on the mode of extraction employed on lignocellulosic biomass. For example, cellulose treated with acids like sulphuric and hydrochloric acid produces a rod-like structure, while controlled hydrolysis produces nanofibers. Table 1 depicts various methods used to fabricate nanocellulose and their features.

Techniques and forms of nanocellulose from commercial sources

| Types of cellulose | Method | Source | Reagent/components | Mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocellulose | Acid hydrolysis | Cotton pulp, fruit bunch pulp, kenaf bast fibers, | Sulphuric acid | Hydrogen and glycosidic bonds are broken at the amorphous region of cellulose | [30] |

| Organic acid hydrolysis | Birch, eucalyptus pulp | Weak acids | Due to the weak nature of the acid, enhanced temperature and longer duration processes are employed | [31] | |

| Acid hydrolysis | Green algae, cotton | Hydrobromic acid | Hydrogen and glycosidic bonds are broken at the amorphous region of cellulose with ultrasonication | [32] | |

| Solid acid hydrolysis | Bamboo pulp | — | Microwave and ultraviolet processes are used. Low efficiency and reaction rates | [33] | |

| Carboxymethylation | Birch, eucalyptus pulp | 1-Chloroacetic acid | Hydroxyl groups are introduced to generate carboxymethylation products | [34] | |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis | Recycled pulp | β-Glucosidase, cellobiohydrolases, and endoglucanases | Endoglucanases break the amorphous regions, cellobiohydrolases break the crystalline region, and β-glucosidase forms glucose from cellulose | [35] | |

| Sulphonation | Recycled wastes | — | Introduction of a negative charge enhances cellulose fibrillation | [36] | |

| Ionic liquid hydrolysis | Waste cotton, lyocell | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulphate | Good thermal and chemical stability, and noninflammable and low vapour pressure | [37] | |

| Functionalization | Cotton pulp, fruit bunch pulp, kenaf bast fibre | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl | Converted to a carboxylic group | [38] | |

| Functionalization | Bamboo pulp | Periodate-chlorite oxidation | Oxidation | [39] | |

| Bacterial nanocellulose | Olive wastes, waste beer yeast, and molasses | Air–liquid interface | Static culture | [40] | |

| Bacterial nanocellulose | Olive wastes, waste beer yeast, and molasses | Air–liquid interface | Stirred culture | [41] | |

| Nanocrystals | Acid hydrolysis | Cotton, polylactic acid | Hydrochloric acid | Hydrogen and glycosidic bonds are broken at the amorphous region of cellulose | [42] |

| Nanofibers | Acid hydrolysis | Bamboo | Phosphoric acid (swelling agent) | Hydrogen and glycosidic bonds are broken at the amorphous region of cellulose | [43] |

| Homogenization | Soybean pod, potato waste, pine pulp, eucalyptus pulp, and alfa | High-pressure pressing | Cellulose fibrillation | [44] | |

| Grinding | Wood pulp | — | Movable and fixed discs grind the cellulose | [45] | |

| Ball milling | Softwood kraft | 0.4–0.6 mm balls | Supermass colloider grinder | [46] | |

| Excursion method | Needle leaf kraft and wood | Twin screw | Cellulose fibrillation | [47] | |

| Cryocrushing | Sugar beet pulp, spring flax fibres, rutabaga, soybean pods, wheat straw, and soy hulls | Liquid nitrogen | Mortar grinding | [48] | |

| Aqueous counter collision | Gluconacetobacter xylinus | High pressure | Wet pulverization by collision | [49] |

Nanocellulose has been immensely useful in research areas due to its unique composition and properties [50]. Its enhanced mechanical properties with sustainable and eco-friendly nature have bagged it a position in the field of reinforcements, remediation, and biomedical applications [51]. Nanocellulose can be synthesized and characterized into various forms, dimensions, structures, and shapes. Shapes mainly consist of spheres, whiskers, and sheets. Cellulose nanofibrils are generally sheets, while nanocrystals are spherical or whisker-shaped. On the basis of length, width, dimension, crystallinity, origin, and availability of functional groups, as well as modifications, nanocellulose can be differentiated as nanocrystals, nanofibrils, and bacterial nanocellulose [52].

3.1 Cellulose nanocrystals

These are needle- or rod-shaped stiff structures that depend on the extraction type and source used for fabrication. The length of cellulose nanocrystals ranges from 10 to 1,000 nm, and the diameter fluctuates from 4 to 25 nm. They are highly crystalline structures with an aspect ratio of 70. Hydrolysis by acids of various forms, like mineral, organic, solid, and ionic liquid acids, develops cellulose nanocrystals of different sizes by breaking bonds in the amorphous regions and functionalizing the crystalline region [53,54]. Other ways to produce cellulose nanocrystals are by mechanical refining, subcritical water hydrolysis, oxidation, and enzymatic action [55,56,57,58]. Parameters that determine the properties and features of nanocellulose crystals are the time, temperature, acid-to-fiber ratio, concentration of the reagent, and source used for synthesis. Shorter rods are produced with blunt ends when mineral acids are used to treat cellulose fibers. With increase in the reaction time and a higher acid to pulp ratio led to a decrease in the size of nanorods generated previously [59]. Nanocrystals of cellulose have been reported to have increased biodegradability, sustainability, renewability, and biocompatibility with decreased thermal expansion, toxicity, and weight.

3.2 Cellulose nanofibrils

Mechanical homogenization of cellulose reported the synthesis of cellulose nanofibrils in the 1980s [60]. The internal structure of cellulose contains fibrils that are bound by hydrogen bonds and several hydroxyl groups. The force with excessive pressure ruptures and disintegrates the cellulose interfibrillar bonds to produce cellulose nanofibrils [61]. Processes like grinding, homogenizing, cryo crushing, milling, microfluidization, and ultrasonication can successfully separate cellulose nanofibres of different dimensions [62,63,64,65,66,67]. Issues pertaining to mechanical methods of synthesis are that they use rigorous levels of energy for extraction. To overcome this drawback, functionalization by pretreatment using specialized reagents for oxidation and cationization has also been attempted in the past few years [68].

3.3 Bacterial nanocellulose

This is also known as microbial nanocellulose, as it is synthesized by strains like Escherichia, Aerobacter, Salmonella, Sarcina, Azotobacter, Rhizobium, Achromobacter, Acetobacter, and Agrobacterium [69]. Glucose chains are synthesized and arranged into microfibrils with the help of the cell wall of the bacterium. Resemblance of the glucose units and aggregation leads to complex structure formation with a diameter ranging from 20 to 100 nm [70]. In vitro synthesis of microbial nanocellulose has also been reported by lysing Gluconacetobacter hansenii PJK as a cell-free system [71]. Certain strains produce highly pure microbial nanocellulose of dimensions less than 50 nm. When media containing required quantities of carbon, nitrogen, mineral content, and pH are provided to cell or cell-free systems, microbial nanocellulose up to a size of 200 nm can be effectively fabricated [72]. Yield and purity of microbial nanocellulose can be increased by manipulating the parameters of fermentation, genetic modification, strain modification, and source versatility [73].

4 Wastewater remediation by nanocellulose

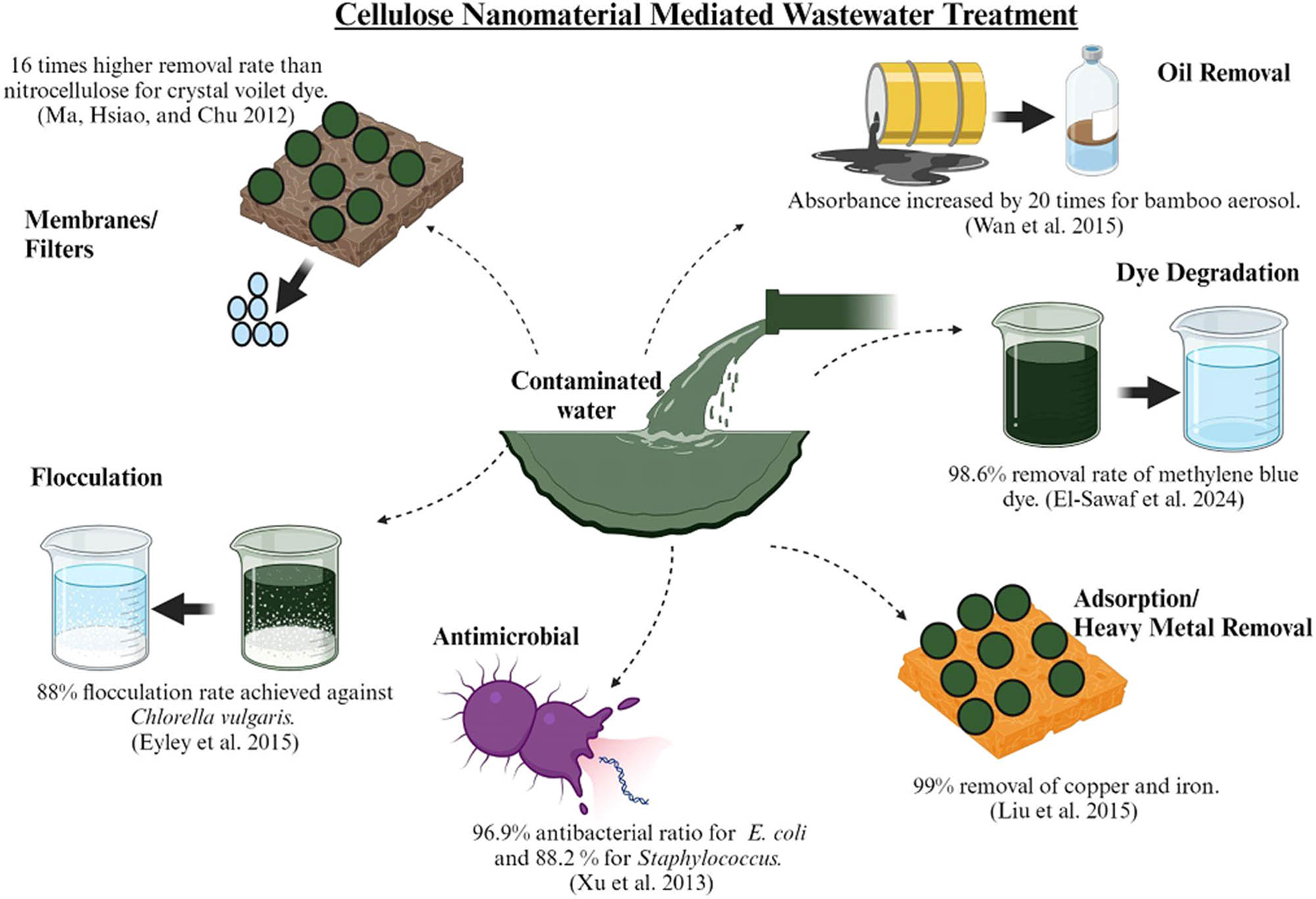

Nanocellulose has gained interest in the field of wastewater remediation due to its high affinity and absorbance of potential contaminants. They have a high surface-to-volume ratio, hydrophilicity, cost-effectiveness, and non-toxicity. Nanocellulose has been fabricated, modified, and structured in the form of membranes, beads, adsorbents, and hydrogels to effectively remove heavy metals, dyes, and pathogens from wastewater sources. Metals that have atomic weights ranging from 63.5 to 200.6 amu or atomic numbers greater than 20 are considered heavy metals. Based on density, they can be defined as metals that have at least 5 g/cm3. They are toxic, non-degradable, found in the crust in low concentrations, and inorganic. They are essential in life systems in small, optimized concentrations. They tend to accumulate in living tissues through the soil and water habitats next to mines, factories, and industries. Essential heavy metals required for the body are zinc, copper, and selenium. Major heavy metal pollutants released in the environment are cadmium, mercury, arsenic, and lead [74]. Figure 2 illustrates the mechanisms used by nanocellulose to treat wastewater in industries. Electrostatic force of attraction is the driving force that enables nanocellulose to remove major contaminants from effluent water [75]. Different forms of nanocellulose are discussed in the following sections and presented in Table 2 with their key absorbance rates. Gelatinized cellulose with graphene oxide yields a highly porous aerogel with an ultralight frame for easy adsorption of pollutants on them. Interwoven structure of graphene oxide with cellulose forms a nanostructure that has hydrogen bonds for the diffusion and transport of contaminants. Active sites of aerogel, along with size, orientation, charge, and structure of the pollutant, determine the adsorption efficiency of the nanostructure [76,77].

Cellulose nanomaterial-based wastewater remediation strategies.

Wastewater remediation by different forms of nanocellulose

| Nanocellulose form | Application | Source | Contaminants | Functionalization agent | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocrystals | Dye removal | Cellulose spray | Methylene blue, basic fusion, crystal violet, and malachite green | Alginate | Maximum adsorption of 255.5 mg/g | [100] |

| Heavy metal removal | Sludge | Silver, copper, and iron | Phosphate functional group | 99% removal of copper and iron | [101] | |

| Dye removal | Cellulose | Methylene blue | Titanium gamma aluminate | 98.6% removal rate | [102] | |

| Dye removal | Acid hydrolysis | Methylene blue | — | Maximum adsorption of 348.9 mg/g | [103] | |

| Flocculation | Cotton | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ultrasonication | Efficient flocculation due to the depth effect | [103] | |

| Membrane | Ultrafine cellulose | Crystal violet | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl and polyacrylonitrile scaffold | 16 times higher removal rate than nitrocellulose | [95] | |

| Membrane | Shrimp shells | Victoria blue, methyl violet, and rhodamine | Glutaraldehyde | 98, 84, and 70% removal of Victoria blue, methyl violet, and rhodamine, respectively | [94] | |

| Membrane | — | E. coli and Staphylococcus | Polyvinyl alcohol and silver nanoparticles | 96.9% antibacterial ratio for E. coli and 88.2% for Staphylococcus | [104] | |

| Flocculation | Cotton wool | Chlorella vulgaris | Imidazolyl | 88% flocculation rate achieved | [105] | |

| Nanofibers | Heavy metal removal | Cotton | Copper and lead | Triethylenetetramine carboxymethyl chitosan | Maximum adsorption of 95.24 mg/g for copper and 144.93 mg/g for lead | [106] |

| Membrane | Wood pulp | Oily wastewater | Polyacrylonitrile and polyethylene terephthalate | Stable permeate flux at 208 L/m2 h; 8 times more than the commercial membrane | [107] | |

| Membrane | Ultrafine cellulose | Chromium and lead | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl and polyacrylonitrile scaffold | Maximum adsorption of 100 mg/g for chromium and 260 mg/g for lead | [93] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Bioethanol byproduct | Silver, copper, and iron | Phosphate functional group | 99% removal of copper and iron | [101] | |

| Membrane | Cellulose | Copper | Phosphate functional group | Removal of 200 mg of copper per square meter of paper | [108] | |

| Oil removal | Canola straw | Oil/water separation | Hexadecyltrimethoxysilane | 162 g/g separated effectively | [109] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Cotton | Cobalt | Poly(itaconic acid)–poly(methacrylic acid)ethylene glycol dimethacrylate | Maximum adsorption of 350.8 mg/g for cobalt | [110] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Wood pulp | Copper and lead | Citric acid | Maximum adsorption of 23.70 mg/g for copper and 82.64 mg/g for lead | [111] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Wood pulp | Uranium dioxide ion | 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl | Maximum adsorption of 167 mg/g | [95] | |

| Flocculation | Raw cellulose | Sludge | periodate oxidation and aminoguanidine | Sludge volume index less than 120 nl/g | [98] | |

| Bacterial nanocellulose | Heavy metal removal | Acetobacter | Copper and lead | Epichlorohydrin, and diethylenetramine | Maximum adsorption of 63.09 mg/g for copper and 87.41 mg/g for lead | [112] |

| Nanocomposite gel/aerogels | Dye removal | Aspen Kraft pulp | Congo red, Acid Red, reactive light yellow | Polyvinylamine sodium periodate | Maximum adsorption of 869.1 mg/g for Congo red, 1469.7 mg/g for active red, and 1250.9 mg/g for yellow dye | [107] |

| Dye removal | Palm leaves | Direct blue 78 | — | Maximum adsorption efficiency of 91.5% | [113] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Cellulose | Cadmium and copper | Magnesium hydroxide | Effective removal by precipitation | [114] | |

| Heavy metal removal | Sludge | Silver, copper, and iron | Phosphate functional group | 99% removal of copper and iron | [101] | |

| Oil removal | Paper waste | Motor oil | Methyltrimethoxysilane | Prominent removal at 0.50 wt% of nanocellulose concentration | [115] | |

| Oil removal | Wheat straw, filter paper, bamboo, and cotton | Oil spills | Polyethylene glycol and methyltrichlorosilane | Absorbance increased by 20 times for bamboo aerosol | [116] | |

| Flocculation | Hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose | Hematite and Kaolinite | Polyacrylamide | Better removal rates than commercial alternatives | [99] | |

| Nanosponge | Oil removal | Hardwood | Oil/water separation | Stearoyl chloride, acetonitrile, and triethylamine | 55 times higher separation | [117] |

| Nanospheres | Dye removal | Tree fern | Red 13 | — | Maximum adsorption of 408 mg/g | [87] |

| Dye removal | Pine sawdust | Metal complex blue and metal complex yellow | — | Maximum adsorption of 280.3 mg/g for metal complex blue and 398.8 mg/g for metal complex yellow | [118] |

4.1 Cellulose nanomaterials as adsorbents

Adsorption is the most sought-after and economical method of removing contaminants from wastewater [78]. Layer-by-layer accumulation of contaminants is enabled on the surface of nanocellulose using bonds and interactions at the molecular level. Ion exchange between the contaminants and nanocellulose with chemical complexation occurs to initiate remediation activity [79]. Previous reports of Saccharum difficinarum L. as a bulk adsorbent have reported an efficient removal of colour and dye particles by up to 98% by artificial neural networks, thus leading to an economical, long-term, and environmentally sustainable alternative of remediation [80]. The process of adsorption is generally spontaneous with liberation of heat due to the change in its ions by counterions that disrupt the preexisting nitro, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups [81].

4.2 Cellulose nanomaterials as a heavy metal remover

Functionalized and activated nanocellulose fibrils have been reported to have a great affinity for heavy metals [82]. Around 1.95 mmol/g of heavy metals were removed with a greater affinity towards toxic heavy metals like cadmium, followed by copper, zinc, cobalt, and nickel in the respective order [83]. Chemical modification of the nanocellulose surface with carboxylic sulphate and amine moieties increases its affinity towards heavy metals [84]. Biosorption of heavy metals by many fungal species follows the Langmuir model [85]. Concentration and the type of biomass play a major role in determining the adsorption rate of heavy metals onto the substrate; for example, Streptomyces sp. have a higher affinity to zinc than to lead at 5–10 mg/L concentrations. The binary system was well supported by this study, which forms a basis for efficient utilization of bulk biomass wastes for wastewater remediation, which in reality contains a mixture of multiple heavy metals [85].

4.3 Cellulose nanomaterials as a dye remover

Organic contaminants can also be effectively removed by nanocellulose adsorbents. Industries that produce or use plastics, papers, or textiles use large quantities of dyes for the coloring process. Dyes are mostly water-soluble and degrade the water quality. Most of the dyes are heat-, light-, and oxidation-resistant, making it quite hard to be removed from wastewater sources [86]. The size of the nanocellulose plays a major role in determining the dye removal capacity of the same. It has been noted that as the size of nanocellulose decreases, the adsorption capacity towards toxic dyes increases [87]. Dye absorption by biomass of the bulk range has been reported previously for Triticum aestivum. Response surface design and artificial neural network techniques have reported that biomass-based degradation of dye uses a general central composite design regime. The Langmuir isotherm model is mostly followed by bulk biomass while removing dye contaminants from wastewaters. The adsorption efficiency is up to 0.36 mg/g. The process of adsorption is generally spontaneous with the liberation of heat due to the change in its ions by counterions that disrupt the preexisting nitro, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups [88]. When the biomass of vegetable wastes was studied at a bulk scale, some substrates had an endothermic adsorption regime following the Freundlich adsorption isotherm [89].

4.4 Cellulose nanomaterials as an oil remover

One of the most hazardous contaminants in the water bodies is oil spills. Conventionally, chemical methods like burning, solidification, and dispersion are performed to remove oil debris from water sources. Physical techniques include skimmers, and biological approaches consist of microbial degradation of hydrocarbons in oil [90]. However, these techniques are time-consuming, less effective, and toxic to the environment [91]. Nanocellulose overcomes these drawbacks by acting as a suitable adsorbent for removing oil debris from water bodies. Aerogels of nanocellulose have been experimented on oil spills, resulting in the efficient removal of the same due to their high hydrophobicity and flexibility.

4.5 Cellulose nanomaterials as membranes

Membranes are used to remove particulate debris from wastewater. It works on the principle of permeability, where some solutes are allowed to pass while others are not, which primarily depends on the pore size of the membrane. Inbuilt issues that affect the efficiency of membranes are fouling caused by chemicals and microbial agents. Nanocellulose, with their hydrophilic nature, when modified aptly, can address this issue and be used as a potential membrane for wastewater remediation [92]. Techniques that could be used to fabricate membranes of nanocellulose are vacuum filtration, followed by coating, electrospinning, and freeze drying. Membranes of multiple layers, like in nanocellulose, possess enhanced mechanical strength, negative surface charge, retention, and flow potentials. Pressure drop is seen to be less when compared to commercial membranes [93]. Reinforcing onto polymers and scaffolds provides the nanocellulose a matrix to form porous structures that range in nanometers [94]. Hydrogen and electrostatic bonds seem to be the predominant mode of interactions between the membrane and the contaminants. Ultrathin nanocellulose fibers have been entangled as mesh-like structures to segregate oil from water and other emulsions. Modification by agents like 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl is done to give targeted and specific functional groups to the ionic mesh structure of nanocellulose [95].

4.6 Cellulose nanomaterials as flocculants

Solid–liquid separation of phases is done in large industries by adding flocculants to avoid colloidal particles, suspended particles, organic components, and dissolved solids [96]. Salts of inorganic nature and multivalent salts are used due to their economical price and easier administration. However, the potential for flocculation is quite low and leads to secondary contamination in the sludge. Organic flocculants have been used to treat a large quantity of sludge in lower dosages, but they are not biodegradable and hence harmful to the environment. Hence, natural polymer-based flocculants like nanocellulose have been used as flocculants as better alternatives [97]. Peroxidase oxidation can transform nanocellulose to remarkable flocculants that have a sludge volume index less than 120 mL/g, which is very satisfactory in industrial parameters [98]. Dosage plays a major role in determining the efficiency of nanocellulose as a flocculant. High doses of nanocellulose are essential to speed up the intensity of flocculation and reduce the turbidity in the effluents [99]. The removal efficiencies were compared for the form of nanocellulose or nanolignin used in studies reported previously in the forthcoming sections. This is to compare and highlight the substrate source for its respective removal efficiency under the experimental conditions. These data are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Surface modifications relevant to nanocellulose for wastewater applications have been reported. The section seems brief, but it is very targeted and specific to the theme of the present article. From Table 3, it can be inferred that nanocellulose has been experimented with for the past two decades in the field of wastewater remediation. Among the different forms of nanocellulose, nanocrystals and nanofibrils are most sought after due to their good absorbency and high surface-to-volume ratio. Dye and heavy metal removal have been extensively studied and reported with an efficiency of up to 99% removal rate for copper and iron metals [101]. Membranes formed by nanocellulose crystals extracted from shrimp shell wastes can eliminate Victoria blue dye by 98% [94]. The most predominantly pathogen E. coli has been treated successfully using nanocellulose composites decorated with silver with a 96.9% efficiency [104]. Recently, combinations of nanocellulose with metal conjugates like titanium gamma illuminate have been used to remove dyes with 98% efficiency [102]. Hence, we can suggest that nanocellulose in the field of wastewater remediation has been explored quite exquisitely. Currently, its combination with nanoconjugates is applied to wastewater to generate satisfactory results that show its potential as a remediating agent.

Wastewater remediation by different forms of nanolignin

| Nanolignin form | Application | Source | Contaminants | Functionalization agent | Remarks | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colloidal spheres | Dye removal | Woody biomass | Methylene blue and methyl orange | Polyethersulfone | More than 95% removal rate | [145] |

| Fibres | Heavy metal removal | Coconut coir | Chromium | Soda and ultrasonication | 92.8% removal efficiency | [25] |

| Particles | Dye removal | Woody biomass | Methylene blue | — | 98% removal rate | [146] |

| Dye removal | — | Methylene blue | Sonication | Maximum adsorption capacity of 109.77 mg/g | [147] | |

| Dye removal | Black liquor | Basic red 2 | Ethylene glycol | Maximum adsorption capacity of 81.9 mg/g | [148] | |

| Gel | Adsorption | Black liquor | Salicylic acid | Chitosan | Regulated and controlled release | [149] |

| Nanocomposite | Dye removal | — | Methylene blue | Palladium nanoparticles and iron oxide | 99% removal efficacy | [150] |

| Powders | Dye removal, heavy metal removal | Black liquor andkraft | Acetaminophen, methylene blue, copper, and chromium | Sepiolite | Superior chromium removal | [151] |

| Heavy metal removal | Shells | Chromium and 4-nitrophenol | Palladium | Good reduction rates | [152] | |

| Dye removal | Alkaline lignin | Methyl orange | Chitosan and iron oxide | More than 95% removal rate | [153] | |

| Spheres | Heavy metal removal | — | Nickel | Iron oxide | Up to 99% removal efficiency | [154] |

| Dye removal | Palm kernels | Methylene blue | Tetrahydrofuran | Maximum adsorption capacity of 74.07 mg/g | [155] | |

| Beads | Adsorbent | Black liquor | — | Chitosan | Sharp peak at 21.8° | [156] |

5 Nanoxylan for wastewater treatment

Xylan is the nanovariant of hemicellulose. It is an environmentally friendly and cost-effective preservative [119]. In monocots, they constitute 50% of the mass, and in dicots, 35% by weight. They possess exceptional antimicrobial and antioxidant features that have paved its use in medical, food, paper, and biomedical research [120]. Their potential for wastewater treatment is still at the laboratory level. The structural effect on remediation traits of nanoxylan is at the experimental level. Investigations and experiments on nanoxylan are very limited, and their influence on wastewater remediation is unclear. Modification of nanoxylan using physical and chemical agents significantly increases the texture of the wood. Prohibition of fungal hyphae inside the biomass leads to preservation of treated samples by 38%. This suggests the potential of nanoxylan as an alternative wastewater remediation material with eco-friendly properties [121].

6 Nanolignin forms and sources

Nanolignin can be synthesized in various shapes like colloidal spheres, fibres, particles, gels, composites, powders, and beads. Lignin nanoparticles enhance the native lignin’s behaviour, which is found to be better than the conventional counterparts [122]. Nanolignin harbours smooth structures and is stable at various experimental as well as physiological conditions. Bulk lignin has a lot of drawbacks, like less water solubility, expensive extraction, heterogeneity, and limited applications, which are addressed with ease by nanolignin [123]. Fabrication of nanolignin is done using chemical treatments like solvent exchange, dialysis, ultrasonication, thermal stabilization, water-in-oil micro-emulsion, acid precipitation, freeze-drying, carbon dioxide saturation, homogenization, sonication, self-assembly, continuous solvent exchange, cross-linking, and enzymatic and microbial approaches [124,125,126,127,128,129,130]. Some common techniques used for the synthesis of nanolignin are discussed in the next section. Acid precipitation is a unique technique, where two types of lignins are synthesized based on pH. At high pH, nanolignin is formed, which is found to be less toxic to yeast and microalgae [131]. Mechanical techniques like sonication have been employed on wheat straw and grass (sarkanda) to produce nanolignin that is independent of the intensity used for breaking down this natural polymer [132]. Depending on the nature of the solvent and other nonspecific interactions, nanolignin can be self-assembled and agglomerated. Bonds like hydrogen, chain entanglement, π–π, and van der Waals play a major role in the self-assembly synthesis of nanolignin [133]. Cyclohexane is reacted with lignin and later with dioxane to precipitate nanolignin. Spray freezing can also be used to create self-assembled nanolignin particles. Solvents like dimethyl sulphoxide that have good solubility of lignin and a high boiling point are used as a main reagent for the spray freezing self-assembly technique [128]. Solvent exchange technique using hardwood and softwood dioxane lignin produces dioxane as well as alkali nanolignin particles ranging from 80 to 104 nm [134].

Biological synthesis of nanolignin generates improved characteristics and physicochemical features in the same when compared to bulk lignin. Indian guard, when degraded using lignin–cellulose complex enzymes, produced nanolignin of size 100 nm [135]. Aspergillus oryzae gives a yield of 45.3% of nanolignin when compared to 62% by ultrasonication and 79% through homogenization. Although the yield seemed to be less, nanolignin obtained from Aspergillus oryzae exhibited antioxidant, antibacterial, and ultraviolet shielding characteristics on fabrics [136]. Similarly, enzymes like laccases from strains like Melanocarpus albomyces and Trametes hirsute use crosslinking techniques to produce nanolignin [127]. Free radicals are generated by breaking glycosidic bonds of non-polyphenolic groups and oxidation of methoxy-substituted phenols and polyphenolic moieties of lignin [137]. Lignin peroxidase releases peroxide radicals and depolymerizes lignin to generate nanolignin [138]. Enzymes used for nanolignin production are nonspecific and randomly oxidize other essential phenolic and aromatic groups in the polymer. Manganese ions react with peroxide in the presence of manganese peroxidase to produce Mn3+ ions that chelate to act as a charge transfer complex in the initial oxidation of lignin polymer. Versatile peroxidase has a combined characteristic of lignin peroxidase and manganese peroxidase [139]. Dye decolourizing peroxide degrades lignin and oxidizes dye at the same time [140].

7 Wastewater remediation by nanolignin

Lignin has complex structures made up of aromatic units. It is considered a valuable precursor for chemicals in biorefinery [141]. It is a highly abundant material with very low cost. The presence of many reactive groups makes its modification easier within the polymer. Nanolignin has exceptional adsorption potential and antimicrobial properties. Recently, this nanomaterial has been finding its way into the remediation sector, like wastewater management and membrane fabrication [21]. Food industry wastes tend to contain more microbes that include pathogens that have harmful effects on the environment and habitat safety. It is quite essential to remove these bacteria from the wastewaters through stable flocculants. The use of antimicrobial agents could further harm the essential microbiomes that aid in remediation. Bacteria, due to their electrostatic repulsion from their negatively charged cell membrane, are quite stable in wastewater. Flocculation aggregates, settles, and removes pathogens conveniently and effectively. However, very limited studies have been reported previously that removed acceptable microorganisms through flocculants. Natural polymers like lignin form a good biodegradable flocculant, but they need to be assembled with other compounds to form complex stable structures with good flocculation capacity. After the flocculation process, the used-up flocculant is benign and does not lead to secondary pollution. Nanolignin is a lyophobic compound that, when loaded onto a polymer matrix, traps bacterial cells easily and removes them posttreatment [142]. Graphene aerogel with lignin has been reported to have superior adsorption of petroleum oils, chloroform, toluene, and carbon tetrachloride. As the temperature is elevated, the adsorption capability is found to increase further [143]. These nanogels of lignin have also been used as catalysts in degrading water pollutants. A high aspect ratio and porous nature increase the surface area of the bionanomaterial, which enables the activation of functional groups like peroxides and persulphates. Thus, oxidation of the contaminants in wastewater is effectively removed by the graphene aerogel [144].

The last 5 years have seen a rise in the utilization of lignin nanoparticles for real-time wastewater treatment, where most of the studies dealt with dye and heavy metal removal. The mechanism of heavy metal poisoning in living tissues follows many routes. Metals like lead, cadmium, and mercury tend to bind to the sulphydryl moieties in proteins. They disrupt the native structure of the protein and its binding sites, which in turn affect enzyme activity and cellular functioning. Superoxide radicals are also generated by many heavy metals alongside hydrogen peroxide, which creates oxidative stress environments in the cell and hampers the functioning of the cellular organelles. A few heavy metals bind to sugar bases of DNA and cause mutations that break and alter the genetic makeup, leading to cancer [25]. Transport channels are also affected by heavy metals that interfere with the transport of cellular nutrients and disrupt homeostasis. Mitochondria are specifically affected by heavy metal poisoning, as it disrupts the ATP reduction and generates reactive oxygen species. The overall electron transport chain is hampered by heavy metals. Lead interacts with the ALA dehydratase enzyme and causes anemia as well as neurological damage. Mercury impacts the functioning of the brain and causes neurotoxicity by interacting with enzymes and denaturing them by joining to sulphhydryl groups [152]. Arsenic metabolizes to form toxic compounds that affect the signalling and genetic repair of the cell. This often leads to the formation of cancers. Cadmium tends to accumulate in the kidneys and cause damage to the renal system.

Toxic dyes, mainly cationic dyes, can damage the cell membrane by their positive charge and disrupt cellular membrane integrity, eventually causing leakage [150]. Protein sites and structures are altered by toxic dyes that change their functioning adversely. Dyes, when exposed to light, produce reactive oxygen species and lead to oxidative damage to the cell [150]. When these components are released in wastewater outlets, they tend to accumulate in higher animals and plants through the food chain, and thus, slowly build up their toxic concentrations in organisms. Methylene blue has been studied the most among all the other commercial dyes found in water bodies. Nanolignin particles have reported 98% removal of methylene blue, while the composite of the same with palladium and iron oxide has exhibited 99% elimination of the toxic dye [146]. The application of nanolignin as a membrane filter and flocculant is still in its infancy. Nanolignin on polyether sulfone base exhibited good pore density with internal macrovoids and high negative charge. This membrane was reported to be stable with a more than 95% removal rate for methylene blue and orange dyes. Electrostatic interactions between the membrane’s charged surface and the dye lie as the major mechanism of action in this removal process [145]. Antimicrobial properties of nanolignin can be exploited in the future. Difficulty in processing lignin is one of the main reasons, as less literature is available on nanolignin when compared to nanocellulose. Adsorption on nanolignin can be influenced by surface parameters, topography, functional groups, and porosity of the adsorbent and the molecular conformation of the adsorbate. Pseudo-second-order kinetics seems to fit better for physisorption of nano-based adsorption. Electrostatic interactions between the oxygen of nanoparticles and the charge of the contaminant form the bond between them. π–π bonds and intramolecular hydrogen bonds are also formed at times between the adsorbent and adsorbate [157].

From Table 4, it can be observed that the contact time and dosage of the adsorbent used are comparatively higher than the metal and carbon-based nanomaterials. However, the efficiency of contaminant removal stands par with previously reported removal percentages by carbon-based nanomaterials [146,160]. Although the reaction duration seems to have increased, utilization of nanocellulose or nanolignin is a much greener alternative than nanocarbons or metal nanoparticles, as they do not produce secondary contaminations and require comparatively less energy to synthesize them.

Comparative data of contaminant removal efficiency between commercial nanomaterials and nanovariants of lignocellulosic biomass

| Nanomaterial | Contaminants | Initial concentration (mg/L) | Contact time (min) | Adsorbent dose (g/L) | Temperature (℃) | pH | Removal efficiency (%) | Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocellulose with clay | Drimarine yellow HF-3GL dye | 10 | 60 | 2 | 30 | 2 | 88 | 48 | [158] |

| Nanoclay hydrogel | Crystal violet | 30 | 720 | — | 25 | 8.9 | — | 12 | [159] |

| Halloysite nanotubes | Safranin O | 100 | 360 | 10,000 | 30 | 4 | 98 | 37 | [160] |

| Cloisite nanocomposite | Methylene blue | 10 | 60 | 1.5 | 25 | 8 | 98 | 32 | [161] |

| Magnesite-halloysite nanocomposite | Methylene blue | 10 | 60 | 40 | 25 | 2 | 99 | 0.7 | [162] |

| Multiwall carbon nanotubes | Methylene blue | 100 | 60 | 3 | 35 | 12 | 80 | 71 | [163] |

| Nano-activated carbon | Sunset yellow | 100 | 240 | 1 | — | 5.8 | — | 22 | [164] |

| Iron– magnesium nanoparticles | Amaranth dye | 24 | 60 | 1 | 35 | 9 | 96 | 37 | [165] |

| Iron nanoparticles | Reactive blue | 200 | 80 | 0.2 | 65 | 3 | 99 | 43 | [166] |

| Nanocellulose (wheat, cotton, paper, and bamboo) | Oil | 50 | 360 | 50 | 35 | 4.5 | — | 20 times more adsorption of oil than their dry weight of nanocellulose | [116] |

| Nanocellulose chitosan | Direct blue 78 | 50 | 120 | 14 | 35 | 3.5 | 92.1 | — | [113] |

| Nanocellulose chitosan | Victoria blue | 1 | 1,440 | 30 × 20 mm membrane | 35 | 5 | 98 | — | [94] |

| Coir nanolignin | Chromium | — | 80 | 0.03 | — | 2 | 92.8 | — | [25] |

| Solvent-treated nanolignin | Methylene blue | 30 | 120 | 1.5 | 35 | — | 98 | 43 | [146] |

| Hydrotropic nanolignin | Methylene blue | 30 | 120 | 1.5 | 35 | — | 56 | 12 | [146] |

8 Techno-environmental impacts

Functionalization and modification techniques used in fabricating nanocellulose, nanoxylan, and nanolignin pose a greater environmental challenge to the environment than the nanomaterial itself. Adapting the best feasible technique available for mass production, like 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl will lead to a lower impact on the environment with good remediation of wastewater. Chemical modifications and carboxymethylation can be avoided to have a lower toxicity load on the environment. Although the fabrication process of nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass leaves an environmental footprint when compared to its bulk extraction counterparts, it still has advantages environmentally, like biodegradability and lesser toxicity over other prominent nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes [167]. For example, the energy input required to produce single-walled carbon nanotubes by laser vaporization in a lab needs 114,000 kW h/kg of power, but the energy required for the production of chemical and mechanical functionalized nanocellulose is around 96 kW h/kg. This is 0.1% of the demand required for the production of carbon nanotubes. Thus, nanolignocellulosic biomass has better environmentally friendly effects than other forms of nanomaterials.

Acid treatment is mainly sought for nanocellulose production, but due to the lesser structural bulkiness of hemicellulose, nanoxylan requires only ultrasonication with mild energy input. Thus, the production process of nanoxylan seems to be much more environment friendly than that of nanocellulose. The emulsifying properties of nanoxylan are at par with commercial synthetic counterparts, making it a greener alternative without chemical functionalization and acid treatment [27]. Similarly, for nanolignin, the extraction and processing of lignin have an environmental impact, but graphene-based lignin has been reported to adsorb by 96%. Further carbonation maximizes the absorption by 522 times more than its weight. Lignin-based nanomaterials are suggested to be reproducible and regenerated by heat and squeeze treatments, thus releasing the entire adsorbed contaminants to free the substrate for subsequent use. This makes nanolignin an efficient, renewal, degradable, and recyclable nanomaterial that has potential wastewater remediation applications.

9 Challenges, limitations, and future scope

Literature backup on lignin degradation is quite limited, less reproducible, and lacks real-time data. This restricts the utilization of various artificial intelligence tools to predict the performance of nanolignocellulosic biomass variants against wastewater components [168]. The process seems to be quite complex and tedious [169]. It is surprising to note that lignin-rich sources have not been exclusively experimented with for lignin nanoparticle production. Microbial-, enzyme-, and fungi-based degeneration of lignin resources has no clarity on the exact mechanisms used by these species to produce nanolignin of special characteristics [170]. The rate of degradation of biodegraders varies from lignin source to source, thus making the overall process very uncertain and unpredictable [171].

Multidimensional and scientific-based investigations should be done to decipher nanolignin formation from lignin wastes. Knowledge of the exact mechanisms and pathways used by enzymes and living species (microbes and fungi) in the formation of nanolignin from sources would help researchers to make more effective hypotheses and generate efficient results faster [12]. The study on the rate of degradation by biodegraders can aid researchers to use agents that work for shorter durations in the field of remediation and pollution control. In-depth investigations are essential on nanolignin and nanoxylan fabrication from wood-rich wastes for application in wastewater management and treatment [169]. The use of artificial intelligence in designing and optimizing nanobiomass substrates can reduce operational costs and reagent utilization. Predictive capabilities of artificial intelligence models can assess the efficiency and efficacy of different nanolignocellulosic adsorbents effective for wastewater remediation [168].

10 Conclusion

Lignocellulosic biomass in its nanoform has gained a special place in the field of wastewater remediation. Nanocellulose, nanoxylan, and nanolignin constitute the overall functional nanoforms of lignocellulosic biomass. In this review, wastewater applications of nanocellulose, nanoxylan, and nanolignin have been highlighted and discussed. The effectiveness of nanocellulose can be enhanced by surface modifications using reagents to add or remove functional groups from the nanoadsorbent. Nanolignin particles have been reported 98% removal of methylene blue, while 70% removal by nanocellulose. The presence of complex phenolic and aromatic groups in lignin makes it a more potent agent for oxidation as well as functionalization. Nanocellulose can easily be fabricated and processed, which makes it an easier candidate for research. However, lignin is the second most available waste byproduct produced by lignocellulosic biomass, and utilization of the same to treat water wastes can conserve and reduce the pollution of the environment in a sustainable way. The application of nanolignin as a membrane filter, flocculant, and phase separator needs to be investigated as its cellulose counterpart. Structural effects on the remediation traits of nanoxylan are at the experimental level. Investigations and experiments on nanoxylan are very limited, and their influence on wastewater remediation is unclear. However, nanoxylan seemingly has exceptional emulsifying properties that can also be explored in the future pertaining to wastewater treatment. It has been reported that the reaction duration seems to be longer for a remediation mediated by nanolignin and nanocellulose when compared to those mediated by metal and carbon nanoparticles. However, utilization of the former is a much greener alternative than the latter counterparts as the former produces negligible secondary contaminations and requires comparatively less energy for fabrication from their respective sources. If scalable synthesis, stability, and reusability of nanovariants of lignocellulosic mass are combined, a new class of nanomaterials can be generated that have circular biobased properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the management of SRMIST, Anna University, and SIMATS Chennai for providing necessary support to carry out the research review work. The authors acknowledge Biorender.com tool for customizing figures.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Nibedita Dey: writing – original draft and supervision. Rajaram Rajamohan: visualization and supervision. Ramesh Malarvizhi Dhaswini and Arpita Roy: formal analysis, investigation, and review and editing. Thanigaivel Sundaram and Maximilian Lackner: writing – review and editing, visualization, supervision, investigation, and conceptualization. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Siddeeg SM, Amari A, Tahoon MA, Alsaiari NS, Rebah FB. Removal of meloxicam, piroxicam and Cd+2 by Fe3O4/SiO2/glycidyl methacrylate-S-SH nanocomposite loaded with laccase. Alex Eng J. 2020;59:905–14.10.1016/j.aej.2020.03.018Search in Google Scholar

[2] WHO/UNICEF Joint Water Supply and Sanitation Monitoring Programme. Progress on drinking water and sanitation: 2014 update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Pooja G, Senthil Kumar P. Various surface-active agents used in flotation technology for the removal of noxious pollutants from wastewater: a critical review. Environ Sci. 2023;9:994–1007.10.1039/D3EW00024ASearch in Google Scholar

[4] Lin L, Yang H, Xu X. Effects of water pollution on human health and disease heterogeneity: A review. Front Environ Sci Eng China. 2022;10:880246. 10.3389/fenvs.2022.880246.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sikiru S, Abiodun OJA, Sanusi YK, Sikiru YA, Soleimani H, Yekeen N, et al. A comprehensive review on nanotechnology application in wastewater treatment a case study of metal-based using green synthesis. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10:108065.10.1016/j.jece.2022.108065Search in Google Scholar

[6] Singh KK, Singh A, Rai S. A study on nanomaterials for water purification. Mater Today. 2022;51:1157–63.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.116Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kumari P, Tripathi KM, Awasthi K, Gupta R. Cost-effective and ecologically sustainable carbon nano-onions for antibiotic removal from wastewater. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2023;62:13837–47.10.1021/acs.iecr.3c01700Search in Google Scholar

[8] Bhaduri B, Dikshit AK, Kim T, Tripathi KM. Research progress and prospects of spinel ferrite nanostructures for the removal of nitroaromatics from wastewater. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2022;5:16000–26.10.1021/acsanm.2c02684Search in Google Scholar

[9] Nath PC, Ojha A, Debnath S, Sharma M, Sridhar K, Nayak PK, et al. Biogeneration of valuable nanomaterials from Agro-wastes: A comprehensive review. Agronomy. 2023;13:561.10.3390/agronomy13020561Search in Google Scholar

[10] Pardo Cuervo OH, Rosas CA, Romanelli GP. Valorization of residual lignocellulosic biomass in South America: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31:44575–607. 10.1007/s11356-024-33968-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Roy S. Pre-treatment methods of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuel production. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2021.10.1201/9781003203414Search in Google Scholar

[12] As V, Kumar G, Dey N, Karunakaran R, K A. Patel AK, et al. Valorization of nano-based lignocellulosic derivatives to procure commercially significant value-added products for biomedical applications. Environ Res. 2023;216:114400.10.1016/j.envres.2022.114400Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Tan YY, Abdul Raman AA, Zainal Abidin MII, Buthiyappan A. A review on sustainable management of biomass: physicochemical modification and its application for the removal of recalcitrant pollutants-challenges, opportunities, and future directions. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31:36492–531.10.1007/s11356-024-33375-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Erfani Jazi M, Narayanan G, Aghabozorgi F, Farajidizaji B, Aghaei A, Kamyabi MA, et al. Structure, chemistry and physicochemistry of lignin for material functionalization. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1:1094. 10.1007/s42452-019-1126-8.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jönsson LJ, Martín C. Pretreatment of lignocellulose: Formation of inhibitory by-products and strategies for minimizing their effects. Bioresour Technol. 2016;199:103–12.10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Amin FR, Khalid H, Zhang H, Rahman SU, Zhang R, Liu G, et al. Pretreatment methods of lignocellulosic biomass for anaerobic digestion. AMB Express. 2017;7:72.10.1186/s13568-017-0375-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Kucharska K, Rybarczyk P, Hołowacz I, Łukajtis R, Glinka M, Kamiński M. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials as substrates for fermentation processes. Molecules. 2018;23:2937. 10.3390/molecules23112937.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Rizwan K, Bilal M. Nanomaterials in biomass conversion: Advances and Applications for bioenergy, biofuels, and bio-based products. Cambridge, UK: Elsevier; 2024.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Jasmani L, Rusli R, Khadiran T, Jalil R, Adnan S. Application of nanotechnology in wood-based products industry: a review. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2020;15:207.10.1186/s11671-020-03438-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Goswami R, Singh S, Narasimhappa P, Ramamurthy PC, Mishra A, Mishra PK, et al. Nanocellulose: A comprehensive review investigating its potential as an innovative material for water remediation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;254:127465.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127465Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Yadav VK, Gupta N, Kumar P, Dashti MG, Tirth V, Khan SH, et al. Recent advances in synthesis and degradation of lignin and lignin nanoparticles and their emerging applications in nanotechnology. Materials. 2022;15:953. 10.3390/ma15030953.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Kumar A, Kumar V. A comprehensive review on application of lignocellulose derived nanomaterial in heavy metals removal from wastewater. Chem Afr. 2022;9:434. 10.1007/s42250-022-00367-8.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Deng J, Sun S-F, Zhu E-Q, Yang J, Yang H-Y, Wang D-W, et al. Sub-micro and nano-lignin materials: Small size and rapid progress. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;164:113412.10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113412Search in Google Scholar

[24] Lee HV, Hamid SBA, Zain SK. Conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to nanocellulose: structure and chemical process. Sci World J. 2014;2014:631013.10.1155/2014/631013Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Kumar A, Kumar V. Coconut coir derived nanolignin for the removal of chromium (VI) from aqueous solution: Adsorption characteristic and mechanism. Chem Afr. 2024;7:953–68.10.1007/s42250-023-00818-wSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Solhi L, Guccini V, Heise K, Solala I, Niinivaara E, Xu W, et al. Understanding nanocellulose-water interactions: turning a detriment into an asset. Chem Rev. 2023;123:1925–2015.10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00611Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Wang S, Xiang Z. Highly stable pickering emulsions with xylan hydrate nanocrystals. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2558. 10.3390/nano11102558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Morsali M, Moreno A, Loukovitou A, Pylypchuk I, Sipponen MH. Stabilized lignin nanoparticles for versatile hybrid and functional nanomaterials. Biomacromolecules. 2022;23:4597–606.10.1021/acs.biomac.2c00840Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Mohanty AK, Misra M, Drzal LT. Natural fibers, biopolymers, and biocomposites. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. 10.1201/9780203508206.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zianor Azrina ZA, Beg MDH, Rosli MY, Ramli R, Junadi N, Alam AKMM. Spherical nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) from oil palm empty fruit bunch pulp via ultrasound assisted hydrolysis. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;162:115–20.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.01.035Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Bian H, Chen L, Dai H, Zhu JY. Integrated production of lignin containing cellulose nanocrystals (LCNC) and nanofibrils (LCNF) using an easily recyclable di-carboxylic acid. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;167:167–76.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.03.050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Sucaldito MR, Camacho DH. Characteristics of unique HBr-hydrolyzed cellulose nanocrystals from freshwater green algae (Cladophora rupestris) and its reinforcement in starch-based film. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;169:315–23.10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Lu Q, Cai Z, Lin F, Tang L, Wang S, Huang B. Extraction of cellulose nanocrystals with a high yield of 88% by simultaneous mechanochemical activation and phosphotungstic acid hydrolysis. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4:2165–72.10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01620Search in Google Scholar

[34] Wågberg L, Decher G, Norgren M, Lindström T, Ankerfors M, Axnäs K. The build-up of polyelectrolyte multilayers of microfibrillated cellulose and cationic polyelectrolytes. Langmuir. 2008;24:784–95.10.1021/la702481vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Fattahi Meyabadi T, Dadashian F, Mir Mohamad Sadeghi G, Ebrahimi Zanjani Asl H. Spherical cellulose nanoparticles preparation from waste cotton using a green method. Powder Technol. 2014;261:232–40.10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.039Search in Google Scholar

[36] Liimatainen H, Visanko M, Sirviö J, Hormi O, Niinimäki J. Sulfonated cellulose nanofibrils obtained from wood pulp through regioselective oxidative bisulfite pre-treatment. Cellulose. 2013;20:741–9.10.1007/s10570-013-9865-ySearch in Google Scholar

[37] Man Z, Muhammad N, Sarwono A, Bustam MA, Vignesh Kumar M, Rafiq S. Preparation of cellulose nanocrystals using an ionic liquid. J Polym Environ. 2011;19:726–31.10.1007/s10924-011-0323-3Search in Google Scholar

[38] Nelson K, Retsina T, Iakovlev M, van Heiningen A, Deng Y, Shatkin JA, et al. American process: Production of low cost nanocellulose for renewable, advanced materials applications. Materials research for manufacturing. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 267–302.10.1007/978-3-319-23419-9_9Search in Google Scholar

[39] Liimatainen H, Visanko M, Sirviöa JA, Hormi OEO, Niinimaki J. Enhancement of the nanofibrillation of wood cellulose through sequential periodate-chlorite oxidation. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:1592–7.10.1021/bm300319mSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Cakar F, Ozer I, Aytekin AÖ, Sahin F. Improvement production of bacterial cellulose by semi-continuous process in molasses medium. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;106:7–13.10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Mautner A, Lee K-Y, Tammelin T, Mathew AP, Nedoma AJ, Li K, et al. Cellulose nanopapers as tight aqueous ultra-filtration membranes. React Funct Polym. 2015;86:209–14.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2014.09.014Search in Google Scholar

[42] Houyong Y, Zongyi Q, Banglei L, Na L, Zhe Z, Long C. Facile extraction of thermally stable cellulose nanocrystals with a high yield of 93% through hydrochloric acidhydrolysis under hydrothermal conditions. J Mater Chem A. 2013;1:3938–44.10.1039/c3ta01150jSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Lu Q, Lin W, Tang L, Wang S, Chen X, Huang B. A mechanochemical approach to manufacturing bamboo cellulose nanocrystals. J Mater Sci. 2015;50:611–9.10.1007/s10853-014-8620-6Search in Google Scholar

[44] Besbes I, Vilar MR, Boufi S. Nanofibrillated cellulose from Alfa, Eucalyptus and Pine fibres: Preparation, characteristics and reinforcing potential. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;86:1198–206.10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.06.015Search in Google Scholar

[45] Gane PAC, Schoelkopf J, Gantenbein D, Schenker M, Pohl M, Kübler B Process for the production of nano-fibrillar cellulose suspensions. World Patent. 2010112519:A1, 2010. Available: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/c9/f9/40/e266b0a1e96f07/WO2010112519A1.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Kekäläinen K, Liimatainen H, Biale F, Niinimäki J. Nanofibrillation of TEMPO-oxidized bleached hardwood kraft cellulose at high solids content. Holzforschung. 2015;69:1077–88.10.1515/hf-2014-0269Search in Google Scholar

[47] Ho TTT, Abe K, Zimmermann T, Yano H. Nanofibrillation of pulp fibers by twin-screw extrusion. Cellulose. 2015;22:421–33.10.1007/s10570-014-0518-6Search in Google Scholar

[48] Panthapulakkal S, Zereshkian A, Sain M. Preparation and characterization of wheat straw fibers for reinforcing application in injection molded thermoplastic composites. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:265–72.10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.043Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Kondo T, Kose R, Naito H, Kasai W. Aqueous counter collision using paired water jets as a novel means of preparing bio-nanofibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;112:284–90.10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.05.064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Doyo AN, Kumar R, Barakat MA. Recent advances in cellulose, chitosan, and alginate based biopolymeric composites for adsorption of heavy metals from wastewater. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2023;151:105095.10.1016/j.jtice.2023.105095Search in Google Scholar

[51] Abitbol T, Rivkin A, Cao Y, Nevo Y, Abraham E, Ben-Shalom T, et al. Nanocellulose, a tiny fiber with huge applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;39:76–88.10.1016/j.copbio.2016.01.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[52] Moon RJ, Martini A, Nairn J, Simonsen J, Youngblood J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:3941–94.10.1039/c0cs00108bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[53] Kontturi E, Meriluoto A, Penttilä PA, Baccile N, Malho J-M, Potthast A, et al. Degradation and crystallization of cellulose in hydrogen chloride vapor for high-yield isolation of cellulose nanocrystals. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:14455–8.10.1002/anie.201606626Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[54] Satyamurthy P, Jain P, Balasubramanya RH, Vigneshwaran N. Preparation and characterization of cellulose nanowhiskers from cotton fibres by controlled microbial hydrolysis. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83:122–9.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.07.029Search in Google Scholar

[55] Mohd Amin KN, Annamalai PK, Morrow IC, Martin D. Production of cellulose nanocrystals via a scalable mechanical method. RSC Adv. 2015;5:57133–40.10.1039/C5RA06862BSearch in Google Scholar

[56] Novo LP, Bras J, García A, Belgacem N, Curvelo AA, da S. A study of the production of cellulose nanocrystals through subcritical water hydrolysis. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;93:88–95.10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.01.012Search in Google Scholar

[57] Sun B, Hou Q, Liu Z, Ni Y. Sodium periodate oxidation of cellulose nanocrystal and its application as a paper wet strength additive. Cellulose. 2015;22:1135–46.10.1007/s10570-015-0575-5Search in Google Scholar

[58] Cao X, Ding B, Yu J, Al-Deyab SS. Cellulose nanowhiskers extracted from TEMPO-oxidized jute fibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;90:1075–80.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.06.046Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Jonoobi M, Oladi R, Davoudpour Y, Oksman K, Dufresne A, Hamzeh Y, et al. Different preparation methods and properties of nanostructured cellulose from various natural resources and residues: a review. Cellulose. 2015;22:935–69.10.1007/s10570-015-0551-0Search in Google Scholar

[60] Noremylia MB, Hassan MZ, Ismail Z. Recent advancement in isolation, processing, characterization and applications of emerging nanocellulose: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;206:954–76.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.064Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Abbasi Moud A. Advanced cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) and cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) aerogels: Bottom-up assembly perspective for production of adsorbents. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;222:1–29.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.148Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[62] Copenhaver K, Li K, Wang L, Lamm M, Zhao X, Korey M, et al. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks for cellulose nanofibril production. Cellulose. 2022;29:4835–76.10.1007/s10570-022-04580-zSearch in Google Scholar

[63] Gond RK, Gupta MK, Singh H, Mavinkere Rangappa S, Siengchin S. Extraction and properties of cellulose for polymer composites. Biodegradable polymers, blends and composites. Cambridge, UK: Elsevier; 2022. p. 59–86.10.1016/B978-0-12-823791-5.00011-9Search in Google Scholar

[64] Bello F, Chimphango A. Optimization of lignin extraction from alkaline treated mango seed husk by high shear homogenization-assisted organosolv process using response surface methodology. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;167:1379–92.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.092Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[65] Vincent S, Kandasubramanian B. Cellulose nanocrystals from agricultural resources: Extraction and functionalisation. Eur Polym J. 2021;160:110789.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2021.110789Search in Google Scholar

[66] Wang X, Peng Z, Liu M, Liu Y, He Y, Liu Y, et al. Extraction of cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) from pomelo peel via a green and simple method. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19:8415–28.10.1080/15440478.2021.1964132Search in Google Scholar

[67] Asem M, Noraini Jimat D, Huda Syazwani Jafri N, Mohd Fazli Wan Nawawi W, Fadhillah Mohamed Azmin N, Firdaus Abd Wahab M. Entangled cellulose nanofibers produced from sugarcane bagasse via alkaline treatment, mild acid hydrolysis assisted with ultrasonication. J King Saud Univ - Eng Sci. 2023;35:24–31.10.1016/j.jksues.2021.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[68] Ceaser R, Chimphango AFA. Comparative analysis of physical and functional properties of cellulose nanofibers isolated from alkaline pre-treated wheat straw in optimized hydrochloric acid and enzymatic processes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;171:331–42.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.01.018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[69] Lin N, Dufresne A. Nanocellulose in biomedicine: Current status and future prospect. Eur Polym J. 2014;59:302–25.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.07.025Search in Google Scholar

[70] Ullah MW, Ul-Islam M, Khan S, Kim Y, Park JK. Innovative production of bio-cellulose using a cell-free system derived from a single cell line. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;132:286–94.10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.037Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[71] Ul-Islam M, Khan T, Park JK. Nanoreinforced bacterial cellulose-montmorillonite composites for biomedical applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;89:1189–97.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.03.093Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[72] Castro C, Zuluaga R, Putaux J-L, Caro G, Mondragon I, Gañán P. Structural characterization of bacterial cellulose produced by Gluconacetobacter swingsii sp. from Colombian agroindustrial wastes. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;84:96–102.10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.10.072Search in Google Scholar

[73] Abraham E, Deepa B, Pothen LA, Cintil J, Thomas S, John MJ, et al. Environmental friendly method for the extraction of coir fibre and isolation of nanofibre. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;92:1477–83.10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.10.056Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[74] Sadak O. Chemical sensing of heavy metals in water. Advanced Sensor Technology. Germany: Elsevier; 2023. p. 565–91.10.1016/B978-0-323-90222-9.00010-8Search in Google Scholar

[75] Rao CNR, Müller A, Cheetham AK. Nanomaterials chemistry: Recent developments and new directions. US: John Wiley & Sons; 2007.10.1002/9783527611362Search in Google Scholar

[76] Joshi P, Sharma OP, Ganguly SK, Srivastava M, Khatri OP. Fruit waste-derived cellulose and graphene-based aerogels: Plausible adsorption pathways for fast and efficient removal of organic dyes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;608:2870–83.10.1016/j.jcis.2021.11.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Tripathi VK, Shrivastava M, Dwivedi J, Gupta RK, Jangir LK, Tripathi KM. Biomass-based graphene aerogel for the removal of emerging pollutants from wastewater. React Chem Eng. 2024;9:753–76. 10.1039/d3re00526g.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Ali I, Gupta VK. Advances in water treatment by adsorption technology. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2661–7.10.1038/nprot.2006.370Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Singh NB, Nagpal G, Agrawal S. Rachna. Water purification by using Adsorbents: A Review. Environ Technol Innov. 2018;11:187–240.10.1016/j.eti.2018.05.006Search in Google Scholar

[80] Kumari S, Chowdhry J, Sharma P, Agarwal S, Chandra Garg M. Integrating artificial neural networks and response surface methodology for predictive modeling and mechanistic insights into the detoxification of hazardous MB and CV dyes using Saccharum officinarum L. biomass. Chemosphere. 2023;344:140262.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140262Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[81] Kumari S, Singh S, Lo S-L, Sharma P, Agarwal S, Garg MC. Machine learning and modelling approach for removing methylene blue from aqueous solutions: Optimization, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2024;166:105361.10.1016/j.jtice.2024.105361Search in Google Scholar

[82] Ajab H, Dennis JO, Abdullah MA. Synthesis and characterization of cellulose and hydroxyapatite-carbon electrode composite for trace plumbum ions detection and its validation in blood serum. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;113:376–85.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.02.133Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[83] Hokkanen S, Repo E, Sillanpää M. Removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions by succinic anhydride modified mercerized nanocellulose. Chem Eng J. 2013;223:40–7.10.1016/j.cej.2013.02.054Search in Google Scholar

[84] Ajab H, Ali Khan AA, Nazir MS, Yaqub A, Abdullah MA. Cellulose-hydroxyapatite carbon electrode composite for trace plumbum ions detection in aqueous and palm oil mill effluent: Interference, optimization and validation studies. Environ Res. 2019;176:108563.10.1016/j.envres.2019.108563Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[85] Kumari S, Agrawal NK, Agarwal A, Kumar A, Malik N, Goyal D, et al. A prominent Streptomyces sp. Biomass-based biosorption of zinc (II) and lead (II) from aqueous solutions: Isotherm and kinetic. Separations. 2023;10:393.10.3390/separations10070393Search in Google Scholar

[86] Crini G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:1061–85.10.1016/j.biortech.2005.05.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[87] Ho Y-S, Chiang T-H, Hsueh Y-M. Removal of basic dye from aqueous solution using tree fern as a biosorbent. Process Biochem. 2005;40:119–24.10.1016/j.procbio.2003.11.035Search in Google Scholar