Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

-

Naheed Ashraf

, Muhammad Abuzar Ghaffari

and Ahmad Irfan

Abstract

Herein, we report a simple and ecofriendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) employing Digera muricata along with bioassay studies of synthesized NPs. The ZnO NPs obtained were indicated by a colour change from yellow to almost faint yellow giving whitish tinge and supported by the appearance of UV-Vis band at 373 nm and were characterized by using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The FT-IR spectrum confirmed the presence of biomolecules fabricated on ZnO NPs as indicated by the absorption bands at 1,378 for C–O cm−1, and ZnO NPs were also evident from the absorption bands at 440 and 670 cm−1, the former being the result of symmetric vibration of hexagonal ZnO and the latter belonged to a very weak vibration of ZnO. Its surface morphology was confirmed by SEM, and the zinc and oxygen bonds were confirmed by EDX analysis giving sharp signals for Zn and oxygen with At% of 17.58 and 30.49, respectively. The antimicrobial activity of ZnO nanoparticles was determined by the agar well diffusion method against pathogenic bacterial and fungal strains using imipenem and miconazole as standards. The results reflected that ZnO NPs enhanced the activity of plant extracts against all employed algal (E. coli, S. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, S. aureus, and B. subtilis) and fungal (T. mentogrophytes, E. floccosum, A. niger, M. canis, and F. culmorum) strains. The antibacterial and antifungal activities of extracts were enhanced by the formation of ZnO NPs. The results indicated that Digera muricata extract contains effective reducing agents for green synthesis of Digera muricata fabricated ZnO NPs, which are more potent antimicrobial than the plant extract and showed almost similar inhibition against lipoxygenase, i.e., the IC50 value of 83.82 ± 1.15, comparable to the standard.

1 Introduction

Nanoparticles have diverse applications in catalysis, purification of water, biological and chemical sensors, wireless electronic equipment, and memory schemes [1,2,3]. Among the metals, zinc is present in all types of enzymes, i.e., transferases, oxidoreductases, ligases, lyases, hydrolases, and isomerases. Moreover, zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) exhibit properties like pyroelectric, semiconducting, and piezoelectric materials [4]. ZnO NPs are employed as preservatives towards the protection of wood and food items from pathogenic agents [5,6]. These act as photocatalysts, which are being used for the removal of organic pollutants [7]. Nanostructured ZnO show extraordinary uses in the area of agriculture, antimicrobial effect, and medicine, and environmental remediation [8]. ZnO NPs also have many uses in gas sensors, cosmetics, optoelectronics, pharmaceuticals, and solar cells [9]. The antimicrobial action of nanoparticles depends on different factors like size, bacterial strain, type of phytochemicals, conditions, shapes, and medium [10]. The enzyme inhibition studies by employing ZnO NPs have been extensively reported in the literature.

Among many other methods available for the synthesis of nanoparticles, plants are employed for the synthesis of nanoparticles, and such a method, called a green approach, is considered more significant than the others [11,12]. The phytochemicals present in plants contain functional groups capable of reducing metal ions and such methods are environmentally friendly and an inexpensive way for the formation of metal nanoparticles. Keeping in view the potential of phytochemicals, plant-based methods of synthesizing nanoparticles has gained momentum at present [13]. The first plant used for the synthesis of nanoparticles was Medicago sativa (alfalfa) [14]. The proposed mechanism for plant-mediated synthesis is the electrostatic interaction between functional groups of phytochemicals and metal salts [15]. In this perspective, Digera muricata (False Amaranth) is an important plant, which is spread worldwide and belongs to the family Amaranthaceae [16,17]. It is a wild herb plant, used as a laxative, edible, and usually known as tandla or tandula. Different primary metabolites (protein, lipids, phenols, and amino acids) and secondary metabolites (flavonoids, saponins, coumarins, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, anthraquinones, and cardiac glycosides) have been isolated from Digera muricata [18]. Its ethanolic extract is a diuretic and is widely used in the herbal treatment for various diseases like constipation, diabetes, and to cure kidney stones in the urinary tract [16,19]. In the present work, Digera muricata has been employed for the synthesis and biofabrication of ZnO NPs. The major benefit of employing Digera muricata for nanoparticles synthesis is the ease of availability of the plant material [20] with its broad range of primary and secondary metabolites along with its medicinal impact. The synthesized metal nanoparticles were characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). In addition to the synthesis of ZnO NPs, the phytochemical analysis of the plant has been accomplished to investigate the type of secondary metabolites associated with this plant. Moreover, the plant extract and the synthesized ZnO NPs were screened against various bacterial and fungal strains to check their antimicrobial potential along with enzymatic inhibition potential. The comparative analysis revealed that ZnO NPs have more antimicrobial and enzyme inhibition potential than the plant extract.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 General

All analytical grade chemicals, reagents, enzymes, and activity standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and were used without any purification. Double-distilled water was used in all experiments. All glassware was washed with deionized water and dried before use.

2.2 Collection of plant material

The plant specimen (2 kg) including flowers, stems, leaves, and roots was collected from rural areas of Dunyapur in October 2017 and identified by Dr. Zafar Ullah Zafar, Associate Professor of Botany, Institute of Pure and Applied Biology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan. A voucher specimen was deposited in the herbarium of Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan (R. R. Stewart F. W. Pak. 232 (1)).

2.3 Preparation of the plant extract

The plant material was washed, crushed dried, and soaked in a conical flask containing methanol for 15 days. After that, the supernatant was concentrated on a rotary evaporator. Moreover, the same process was repeated three times and the extract thus obtained was dried. The dry weight of plant extract was 40 g. This plant extract was used for different chemical tests.

2.4 Phytochemical screening

Phytochemical tests were used for the identification of various classes of naturally occurring compounds by employing standard procedures. The tests for alkaloids, tannins, flavones and flavonols, flavonoids, glycosides, triterpenoids, saponins, and carbohydrates were conducted, and the results indicated the presence of most of the above-mentioned compounds in the extract of Digera muricata. For alkaloids, in a 3 mL sample solution in water, a few drops of Wagner’s reagent were added. and the formation of a brownish precipitate indicated the presence of alkaloids. For tannins, a few drops of 1% lead acetate solution was added and the appearance of a yellow-coloured precipitate indicated its presence. For flavones, to the plant extract was added concentrated H2SO4 dropwise; a deep yellow colour appeared that indicated the presence of flavones and flavonols. The Shinoda test showed the presence of flavonoid, Liebermann’s test showed the presence of glycosides, and the Salkowski test indicated the presence of triterpenoids. The Molisch test indicated the absence of carbohydrates, and the foam test was used to test for saponins, indicating their presence in Digera muricata.

2.5 Synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles

The method reported by Fakhari et al., with slight modifications, was used for the preparation of ZnO NPs [21]. Zinc acetate (0.25 g) was dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water to which was added dropwise to the plant extract solution (5 mL). This mixture was then stirred for 10 min by using a magnetic stirrer and NaOH (0.02 M) was added dropwise into the solution with stirring to adjust the pH to 12. Zinc oxide crystals (off-white) were formed, which were washed with distilled water, filtered, and oven-dried to obtain ZnO nanoparticles.

2.6 UV-Vis and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The formation of zinc oxide nanoparticles was confirmed by obtaining UV-Vis spectra of the solution in quartz cuvettes with an optical path length of 10 mm and a resolution of 1 nm using a UV-Vis. spectrophotometer (1,800) at absorption wavelengths between 200 and 800 nm. The FTIR spectra of ZnO nanoparticles were obtained using an AT-FTIR spectrophotometer. Both samples were placed in the sample compartment of the instrument for analysis, and a spectrum in the range 4,000–500 cm−1 was plotted.

2.7 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The particle shape, morphology, and sizes of nanoparticles at micro and nanoscales are determined by SEM. In this technique, a high-energy electron beam was scanned over the nanoparticles sample, and then this electron beam was scattered back to obtain the characteristic features [22]. The elemental analysis of single particles was carried out using an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscope (EDX) supplemented with a Jeol 5800 LV scanning electron microscope at the instrument conditions: accelerating voltage of 20 keV and counting time of 100 s.

2.8 Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy

When the electron beam is bombarded onto the sample, it ejects electrons and creates vacant space, which is filled by electrons coming from a high energy shell; to balance the energy gap between these two electrons the X-rays are emitted. The EDX counts the number of X-rays (characteristic of element) emitted against their energy. A spectrum having energy on one axis and X-rays emitted on the other axis was obtained. This gives quantitative and qualitative information about the elements found in the sample.

2.9 In vitro antibacterial and antifungal activity

The in vitro antibacterial activities of plant extract and ZnO NPs was determined against bacterial strains E. coli (ATCC 25922), S. faecalis (ATCC 700802), P. aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), K. pneumoniae (ATCC 700721), S. aureus (ATCC 25923), and B. subtilis (ATCC 6051) using the agar well diffusion method [23] and the results are shown in Table 3. For screening, the same concentrations of the standard antibacterial agent (imipenem) and test sample solutions were used. The molten agar was cooed to 45°C, mixed with bacterial inoculum, and poured into the sterile Petri dishes. Using a sterile metallic borer, the wells (6 mm in diameter) were made in the agar media at a distance of almost 22–24 mm away from each other. Different cork borers were used for different bacterial strains. Then, 100 µL of the test sample was introduced on the agar surface with the help of a sterile pipette. After that, the Petri dishes were kept for incubation for 24 h at 37°C. In the end, the antibacterial activity of the reference drug and each sample was determined by measuring the diameter of inhibition zones in mm.

The antifungal activity was determined against the fungal strains; T. mentagrophytes (TIMM 2789), E. floccosum (NBRC 9045), A. niger (ATCC 1015), M. canis (NBRC 9182), and F. culmorum (NRRL 25475) according to the previous procedure [24]. The dextrose agar medium mixed with fungal inoculum was evenly spread by means of a sterile cotton swab on sterilized Petri dishes. Using sterilized metallic borers, the wells (6 mm in diameter) were dug in the agar media spaced at a distance of almost 22–24 mm. The same concentrations (100 µL) of the sample solutions and reference antifungal agent (miconazole) were poured into the Petri dishes. The Petri dishes were incubated at 37°C for 48 h. After incubation, confluent fungal growth was obtained. Inhibition zones of the fungal growth were measured in mm for all the test samples and the antifungal agent.

2.10 Enzymatic (lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase) assay

Inhibitions of the crude extract and ZnO nanoparticles by lipoxygenase were assayed according to the spectrophotometric (absorbance at 234 nm) method established by Tappel [25] by using quercetin (0.5 mM well−1) as a positive control. For the lipoxygenase activity, a final volume of 200 µL of the assay mixture was prepared, which consisted of 20 µL of lipoxygenase enzyme, 160 µL of sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0, 100 mM), and 10 µL of test samples (in 100 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4). The assay mixture was preincubated at 25°C for 10 min. Then, the reaction was initiated by adding 10 µL of linoleic acid solution that acted as substrate. The change in the absorbance reading was recorded at 234 nm after 6 min. The IC50 values were calculated using EZ-Fit Enzyme Kinetics Software [26]. The inhibitory activity of the compounds was determined against α-glucosidase according to the previous method [27]. A 250 µL of acarbose was incubated with α-glucosidase solution (500 µL) in phosphate buffer (pH 6.9, 100 mM) for 20 min at 37°C. Then, p-NPG (p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside solution (1 mM, 250 µL) and 250 µL of starch (1%) were added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After that, the absorbance of the resulting mixture was recorded at 400 nm. A blank solution was used for correcting the absorbance readings. 1-Deoxynojirimycin acted as a positive control. The % enzyme inhibition was calculated as

3 Results and discussion

Digera muricata contains a rich number of secondary metabolites and has attracted great interest due to its extraordinary medicinal value, therapeutic uses, and edible properties. Therefore, phytochemical analysis of Digera muricata along with the synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles was performed from the methanolic extract of Digera muricata.

3.1 Phytochemical screening of the plant extract

For phytochemical analysis, standard tests for various classes of compounds like alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, saponins, glycosides, carbohydrates, flavones and flavonols, and triterpenoids were performed. These tests were positive for alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, flavones and flavonols, triterpenoids, and saponins and negative for carbohydrates as summarized in Table 1. In previous reports, these phytochemicals have been responsible for the reduction and then capping of nanoparticles [28,29]. The presence of these phytochemicals in Digera muricata was therefore responsible for reducing zinc metal to zinc oxide nanoparticles, which were later surrounded by the plant extract, also called capping of nanoparticles.

Phytochemicals investigated in the plant extract

| Phytochemicals | Plant sample | Phytochemicals | Plant sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids | + | Saponins | + |

| Tannins | + | Carbohydrates | − |

| Flavonoids | + | Flavones | + |

| Glycosides | + | Triterpenoids | + |

+: present, −: absent.

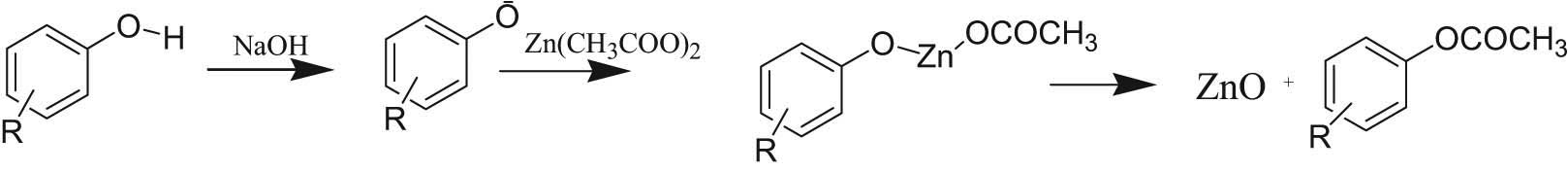

3.2 Biosynthesis of Digera muricate–ZnO nanoparticles

ZnO nanoparticles were obtained as light grey precipitates The precipitates were then thoroughly washed with distilled water to obtain white ZnO nanoparticles. The mechanism reported for the chemical synthesis of ZnO NPs is shown in Eqs. 2 and 3. A similar colour of ZnO nanoparticles was reported by Varghese et al. [28]:

Keeping in view the above mechanisms, an analogous mechanism for green synthesis has been proposed. The proposed mechanism consists of three steps. In the first step, sodium hydroxide abstracts a proton from the phenolic or flavonoid moiety containing OH groups on the benzene ring. Then, this negatively charged phenolate ion replaces one of the acetate ions by a simple replacement reaction. Later, the organometallic zinc compound disintegrates in such a way to give ZnO along with a phenolic or flanoidal compound containing acetate groups.

3.3 Characterization of ZnO NPs: UV-Vis spectroscopy

The green, eco-friendly, low-cost synthesis of ZnO-NPs was performed using Digera muricata extract. The biochemicals like alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, phenols, etc. present in the Digera muricata leaf extract reduced Zn ions to ZnO nanoparticles, which was visible by the colour change, a first indication of the ZnO-NPs synthesis. The change in the colour corresponding to the single peak of absorption in the UV-Vis spectrum was because of characteristic changes in the energy levels of electrons in the nanoparticles. The maximum absorption peaks of ZnO were observed at 373 nm in the 200–800 nm range.

3.4 FTIR analysis

The reducing and stabilizing or capping were predictable by comparing the different functional groups present in FTIR spectra of the extract and ZnO nanoparticles. Metal nanoparticles were frequently centrifuged and redispersed in deionized water in order to eliminate the possibility of unbound residual organic moieties. The FTIR spectra of the plant extract showed a very close resemblance to the FTIR spectra of Digera muricata–ZnO NPs, excluding some differences in a few peaks. This indicated that some metabolites of the Digera muricata extract remained on the surface of ZnONPs. The possible biomolecules responsible for ZnO reduction and then its capping via different bond vibrations were identified in the spectrum. ZnO NPs showed different phytochemicals as shown by the characteristic peaks at 609, 699, and 894 cm−1 (attributed to vibrations of COO– carboxyl group), 1,378 cm−1 (C–O stretching), 1,489 cm−1 (C–H bending), 1,519, 1,557 cm−1 (C═C stretching), and broadband at 3,300–3,400 cm−1 (O–H or N–H stretching) indicated the formation of ZnO nanoparticles. The FTIR results showed that different metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, etc. are attached on the surface of ZnO NPs and remained bound regardless of washing repeatedly, and these metabolites reduced zinc ions to nanoparticles. The peaks at 440–670 cm−1 were attributed to ZnO stretching and deformation, respectively.

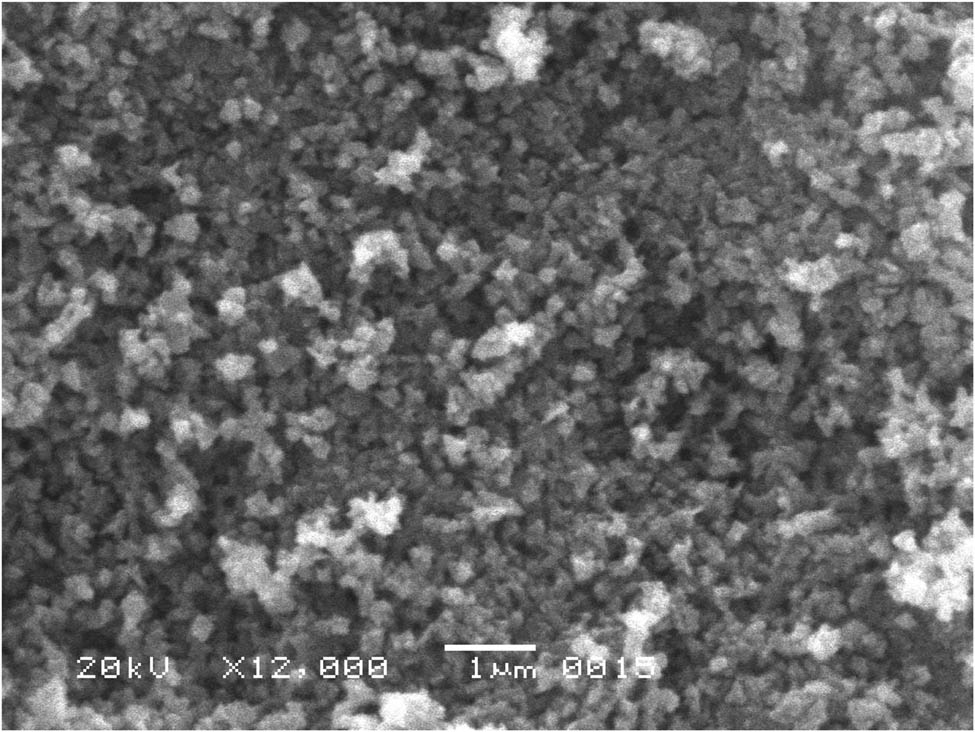

3.5 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

The SEM images of ZnO-NPs are shown in Figure 1, which confirmed the surface morphologies and their shape. The SEM image revealed that zinc oxide nanoparticles are spherical, irregular, and spongy, and their individual particle [28] size ranges from 55 to 80 nm with some deviations. The metal oxides were uniformly distributed in the three-dimensional polymeric network structure; the accumulation could be induced by densification resulting in the narrow space between particles, which may be due to the flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, and glycosides present in the Digera muricata and were responsible for the formation of ZnO NPs.

SEM image of zinc oxide nanoparticles.

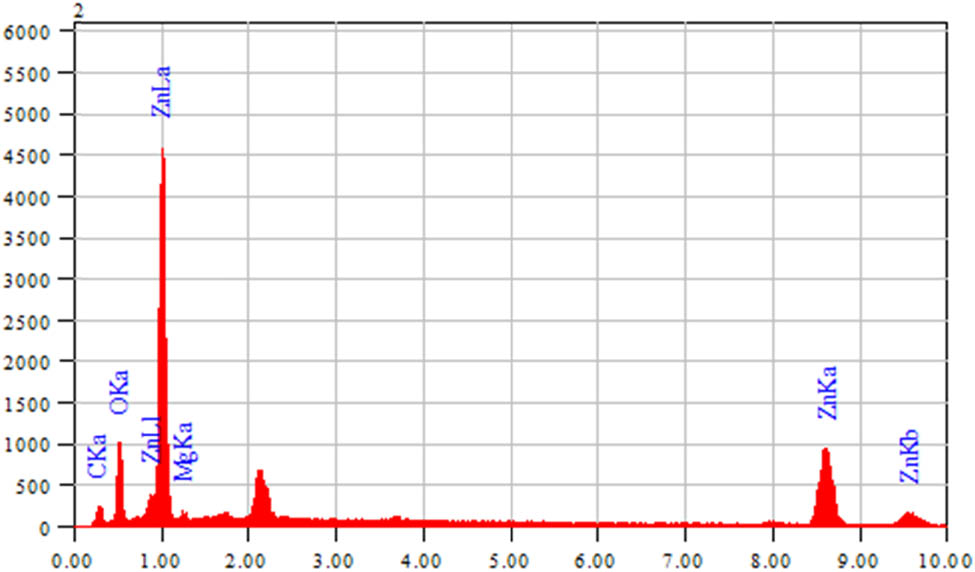

3.6 Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis

The EDX results confirmed the presence of Zn-NPs in the oxide form. It was used to find the elemental composition of nanoparticles and the pattern indicated that the sample contains zinc oxide. The presence of weak signals of carbon and oxygen atoms displayed that biomolecules within the extract are involved in the synthesis of ZnO-NPs. The EDX spectrum for the newly synthesized ZnO-NPs in Figure 2 shows the elemental profile of the Digera muricata–ZnO NPs. The EDX analysis showed sharp signals of Zn and oxygen with At% of 17.58 and 30.49. The atomic and mass % obtained from the EDX spectrum is presented in Table 2.

EDX graph of ZnO nanoparticles.

EDX weight ratio of the synthesized ZnO NPs

| Element | Energy (keV) | Mass% | Error% | At% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C K | 0.277 | 24.15 | 0.22 | 46.63 |

| O K | 0.525 | 21.04 | 0.22 | 30.49 |

| Na K | 1.041 | 5.26 | 0.30 | 5.31 |

| Zn K | 8.630 | 49.55 | 0.89 | 17.58 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

3.7 Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activities of the plant extract and ZnO-NPs were determined against selected bacterial and fungal strains according to the standard method [30]. The bacterial strains (E. coli, S. aureus, S. faecalis, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and B. subtilis) used imipenem as a standard, whereas fungal strains (T. mentagrophytes, E. floccosum, A. niger, M. canis, and F. culmorum) used miconazole as a standard; the results are tabulated in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. The results showed that the microbicidal activity improved during the ZnO-NP synthesis and indicated the dual role of phytochemicals, i.e., metal salt reduction as well as NP stabilization. The zone of inhibition was found to be in the range 7–22 mm against bacterial strains, while that for fungal strains, was recorded in the range of 17–33 mm.

Antibacterial assay of the plant extract and ZnO nanoparticles

| Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | E. coli | S. faecalis | P. aeruginosa | K. pneumoniae | S. aureus | B. subtilis |

| Plant extract | 8 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 8 |

| ZnO NPs | 21 | 19 | 15 | 17 | 22 | 20 |

| Imipenum | 31 | 32 | 29 | 28 | 31 | 30 |

Each value are average of three assays and represented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM).

Antifungal assay of the plant extract and ZnO-nanoparticles

| Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | T. mentogrophytes | E. floccosum | A. niger | M. canis | F. culmorum |

| Plant extract | 22 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 19 |

| ZnO NPs | 28 | 33 | 31 | 27 | 29 |

| Miconazole | 39 | 41 | 40 | 39 | 41 |

Each value are average of three assays and represented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM).

3.8 Lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities

The plant extract and ZnO-NPs were evaluated for their lipoxygenase inhibitory activities; they showed the strongest potential with IC50 values of 61.07 and 57.01 µg/mL, respectively, compared with the positive control quercetin with an IC50 value of 23.82 µg/mL, as shown within Table 4. The plant extract and ZnO-NPs were also evaluated for α-glucosidase enzymatic inhibitory activities and displayed IC50 (μM) values of 106.5 and 98.1, respectively (Table 5). Deoxynojirimycin (IC50 = 301.4 μM) was used as a positive control for the α-glucosidase enzyme inhibitory activity. As these compounds showed moderate to significant enzymatic inhibition, in the future, these nanoparticles and plant extract phytochemicals may be used for the treatment of COVID-19 based main protease (Mpro) protein inhibition [31,32].

Lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase inhibition of samples

| Sample | Lipoxygenase inhibition | α-glucosidase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOX (%) at 0.5 mM | LOX (IC50) µmol | IC50 c with SEM | |

| Plant extract | 80.48 ± 0.94 | 61.07 ± 0.06 | 106.5 ± 1.4 |

| ZnO NPs | 83.82 ± 1.15 | 57.01 ± 0.09 | 98.1 ± 2.2 |

| Quercetina | 94.65 ± 1.06 | 23.82 ± 0.05 | — |

| Deoxynojirimycinb | — | — | 301.4 ± 2.3 |

LOX = lipoxygenase; apositive control for lipoxygenase inhibition; bpositive control for α-glucosidase; cIC50 (μM) values are average of three assays and represented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM).

4 Conclusions

Phytochemical screening of the methanolic extract of Digera muricata showed the presence of alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, flavones and flavonols, triterpenoids, and saponins. A fast, easy, and green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Digera muricata extracts was successfully completed by the reduction of zinc acetate solutions. The synthesized ZnO-NPs were confirmed by characterization using spectroscopic techniques like UV-Vis spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy, and microscopic techniques like SEM and EDX. The EDX analysis showed sharp signals between 0 and 2 and Zn peaks between 8 and 10. In addition, the antimicrobial potential of nanoparticles and their comparison with that of Digera muricata extract indicated that ZnO-NPs were more promising antimicrobial agents than that of plant extract. The extract and ZnO-NPs demonstrated lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities using quercetin and deoxynojirimycin as standards, respectively. It can be assumed that the plant extract and ZnO NPs contain potent enzymes (lipoxygenase and α-glucosidase) inhibiting phytochemicals that may be used for the treatment of inflammation, COVID-19, asthma, and cancer.

Acknowledgements

M. Imran and A. Irfan extend their appreciation to the Deanship of scientific research at King Khalid University (KKU), Saudi Arabia, for funding through research groups program under grant number R.G.P. 1/297/42.

-

Funding information: M. A. A. express appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University Saudi Arabia through research groups program under grant number R.G.P. 1/297/42.

-

Author contributions: Naheed Ashraf: writing – original draft, formal analysis; Sajjad H. Sumrra: writing – review and editing, revision; Mohammed A. Assiri: writing – review and editing, resources; Muhammad Usman: writing – original draft, visualization, project administration; Riaz Hussain: writing – original draft, formal analysis; Farooq Aziz: methodology, formal analysis; Muhammad Abuzar Ghaffari: writing – original draft, formal analysis; Ajaz Hussain: writing – original draft, formal analysis, visualization, project administration; Muhammad Naeem Qaisar: writing – original draft, visualization; Muhammad Imran: writing – review and editing, visualization, project administration; Ahmad Irfan: visualization, project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets are also available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Sun Y, Xia Y. Shape-controlled synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles. Science. 2002;298(5601):2176–9.10.1126/science.1077229Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Vijayan SR, Santhiyagu P, Ramasamy R, Arivalagan P, Kumar G, Ethiraj K, et al. Seaweeds: a resource for marine bionanotechnology. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2016;95:45–57.10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.06.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Pugazhendhi S, Kirubha E, Palanisamy PK, Gopalakrishnan R. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Alpinia calcarata by Green approach and its applications in bactericidal and nonlinear optics. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;357:1801–8.10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.09.237Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wahab R, Kim YS, Lee DS, Seo JM, Shin HS. Controlled synthesis of zinc oxide nanoneedles and their transformation to microflowers. Sci Adv Mater. 2010;2(1):35–42.10.1166/sam.2010.1064Search in Google Scholar

[5] Schilling K, Bradford B, Castelli D, Dufour E, Nash JF, Pape W, et al. Human safety review of “nano” titanium dioxide and zinc oxide. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9(4):495–509.10.1039/b9pp00180hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Gerloff K, Fenoglio I, Carella E, Kolling J, Albrecht C, Boots AW, et al. Distinctive toxicity of TiO2 rutile/anatase mixed phase nanoparticles on Caco-2 cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25(3):646–55.10.1021/tx200334kSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Raja A, Ashokkumar S, Marthandam RP, Jayachandiran J, Khatiwada CP, Kaviyarasu K, et al. Eco-friendly preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Tabernaemontana divaricata and its photocatalytic and antimicrobial activity. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2018;181:53–8.10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.02.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Kumar SS, Venkateswarlu P, Rao VR, Rao GN. Synthesis, characterization and optical properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int Nano Lett. 2013;3(1):30.10.1186/2228-5326-3-30Search in Google Scholar

[9] Divband B, Khatamian M, Eslamian GK, Darbandi M. Synthesis of Ag/ZnO nanostructures by different methods and investigation of their photocatalytic efficiency for 4-nitrophenol degradation. Appl Surf Sci. 2013;284:80–6.10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.07.015Search in Google Scholar

[10] Misra SK, Dybowska A, Berhanu D, Luoma SN, Valsami-Jones E. The complexity of nanoparticle dissolution and its importance in nanotoxicological studies. Sci Total Environ. 2012;438:225–32.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.08.066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Ahmed S, Ahmad M, Swami BL, Ikram S. A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: a green expertise. J Adv Res. 2016;7(1):17–28.10.1016/j.jare.2015.02.007Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kuppusamy P, Yusoff MM, Maniam GP, Govindan N. Biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant derivatives and their new avenues in pharmacological applications – an updated report. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(4):473–84.10.1016/j.jsps.2014.11.013Search in Google Scholar

[13] Varshney R, Bhadauria S, Gaur MS. A review: biological synthesis of silver and copper nanoparticles. Nano Biomed Eng. 2012;4(2.10.5101/nbe.v4i2.p99-106Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gardea-Torresdey JL, Gomez E, Peralta-Videa JR, Parsons JG, Troiani H, Jose-Yacaman M. Alfalfa sprouts: a natural source for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2003;19(4):1357–61.10.1021/la020835iSearch in Google Scholar

[15] Zhou Y, Lin W, Huang J, Wang W, Gao Y, Lin L, et al. Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by foliar broths: roles of biocompounds and other attributes of the extracts. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2010;5(8):1351.10.1007/s11671-010-9652-8Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sharma N, Vijayvergia R. A review on Digera muricata (L.) Mart – a great versatile medicinal plant. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2013;20(1):114–9.Search in Google Scholar

[17] El-Ghamery AA, Sadek AM, Abdelbar OH. Comparative anatomical studies on some species of the genus Amaranthus (Family: Amaranthaceae) for the development of an identification guide. Ann Agric Sci. 2017;62(1):1–9.10.1016/j.aoas.2016.11.001Search in Google Scholar

[18] Kritikar K, Basu B. Indian medicinal plants. M/S Bishen Singh, Mahendra Pal Singh. International book distributors. Dehradune, India. Vol. 1; 1975. p. 672–5.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Aggarwal S, Gupta V, Narayan R. Ecological study of wild medicinal plants in a dry tropical peri-urban region of Uttar Pradesh in India. Int J Med Aromatic Plants. 2012;2:246–53.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Chandirika JU, Annadurai G. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using leaf extract abutilon indicum. Glob J Biotechnol Biochem. 2018;13(1):7–11.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Fakhari S, Jamzad M, Kabiri Fard H. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: a comparison. Green Chem Lett Rev. 2019;12(1):19–24.10.1080/17518253.2018.1547925Search in Google Scholar

[22] Buhr E, Senftleben N, Klein T, Bergmann D, Gnieser D, Frase CG, et al. Characterization of nanoparticles by scanning electron microscopy in transmission mode. Meas Sci Technol. 2009;20(8):084025.10.1088/0957-0233/20/8/084025Search in Google Scholar

[23] Choudhary MI, Thomsen WJ. Bioassay techniques for drug development. Singapore: CRC Press, Harwood Academic Publishers; 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[24] McLaughlin J, Chang C, Smith D. Bench-top” bioassays for the discovery of natural products: an update in studies in natural products chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. p. 383–409.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Tappel A. The mechanism of the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids catalyzed by hematin compounds. Arch Biochem biophysics. 1953;44(2):378–95.10.1016/0003-9861(53)90056-3Search in Google Scholar

[26] Palanisamy U, Manaharan T, Teng LL, Radhakrishnan AK, Subramaniam T, Masilamani T. Rambutan rind in the management of hyperglycemia. Food Res Int. 2011;44(7):2278–82.10.1016/j.foodres.2011.01.048Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zechel DL, Boraston AB, Gloster T, Boraston CM, Macdonald JM, Tilbrook DMG, et al. Iminosugar glycosidase inhibitors: structural and thermodynamic dissection of the binding of isofagomine and 1-deoxynojirimycin to β-glucosidases. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(47):14313–23.10.1021/ja036833hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Varghese E, George M. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int J Adv Res Sci Eng. 2015;4(1):307–14.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Gunaydin K, Topcu G, Ion RM. 1, 5-Dihydroxyanthraquinones and an anthrone from roots of Rumex crispus. Nat Product Lett. 2002;16(1):65–70.10.1080/1057563029001/4872Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Imran M, Irfan A, Assiri MA, Sumrra SH, Saleem M, Hussain R, et al. Coumaronochromone as antibacterial and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors from Aerva persica (Burm. f.) Merr.: experimental and first-principles approaches. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 2021;76(1–2):71–8.10.1515/znc-2020-0138Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Irfan A, Imran M, Khalid M, Ullah MS, Khalid N, Assiri MA, et al. Phenolic and flavonoid contents in Malva sylvestris and exploration of active drugs as antioxidant and anti-COVID19 by quantum chemical and molecular docking studies. J Saudi Chemi Soc. 2021;25(8):101277.10.1016/j.jscs.2021.101277Search in Google Scholar

[32] Khaerunnisa S, Kurniawan H, Awaluddin R, Suhartati S, Soetjipto S. Potential inhibitor of COVID-19 main protease (Mpro) from several medicinal plant compounds by molecular docking study; 2020. p. 2020030226.10.20944/preprints202003.0226.v1Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Naheed Ashraf et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- MW irradiation and ionic liquids as green tools in hydrolyses and alcoholyses

- Effect of CaO on catalytic combustion of semi-coke

- Studies of Penicillium species associated with blue mold disease of grapes and management through plant essential oils as non-hazardous botanical fungicides

- Development of leftover rice/gelatin interpenetrating polymer network films for food packaging

- Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract

- Green synthesized silver and copper nanoparticles induced changes in biomass parameters, secondary metabolites production, and antioxidant activity in callus cultures of Artemisia absinthium L.

- Gold nanoparticles from Celastrus hindsii and HAuCl4: Green synthesis, characteristics, and their cytotoxic effects on HeLa cells

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies

- One-step preparation of metal-free phthalocyanine with controllable crystal form

- In vitro and in vivo applications of Euphorbia wallichii shoot extract-mediated gold nanospheres

- Fabrication of green ZnO nanoparticles using walnut leaf extract to develop an antibacterial film based on polyethylene–starch–ZnO NPs

- Preparation of Zn-MOFs by microwave-assisted ball milling for removal of tetracycline hydrochloride and Congo red from wastewater

- Feasibility of fly ash as fluxing agent in mid- and low-grade phosphate rock carbothermal reduction and its reaction kinetics

- Three combined pretreatments for reactive gasification feedstock from wet coffee grounds waste

- Biosynthesis and antioxidation of nano-selenium using lemon juice as a reducing agent

- Combustion and gasification characteristics of low-temperature pyrolytic semi-coke prepared through atmosphere rich in CH4 and H2

- Microwave-assisted reactions: Efficient and versatile one-step synthesis of 8-substituted xanthines and substituted pyrimidopteridine-2,4,6,8-tetraones under controlled microwave heating

- New approach in process intensification based on subcritical water, as green solvent, in propolis oil in water nanoemulsion preparation

- Continuous sulfonation of hexadecylbenzene in a microreactor

- Synthesis, characterization, biological activities, and catalytic applications of alcoholic extract of saffron (Crocus sativus) flower stigma-based gold nanoparticles

- Foliar applications of plant-based titanium dioxide nanoparticles to improve agronomic and physiological attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants under salinity stress

- Simultaneous leaching of rare earth elements and phosphorus from a Chinese phosphate ore using H3PO4

- Silica extraction from bauxite reaction residue and synthesis water glass

- Metal–organic framework-derived nanoporous titanium dioxide–heteropoly acid composites and its application in esterification

- Highly Cr(vi)-tolerant Staphylococcus simulans assisting chromate evacuation from tannery effluent

- A green method for the preparation of phoxim based on high-boiling nitrite

- Silver nanoparticles elicited physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant modifications in rice plants to control Aspergillus flavus

- Mixed gel electrolytes: Synthesis, characterization, and gas release on PbSb electrode

- Supported on mesoporous silica nanospheres, molecularly imprinted polymer for selective adsorption of dichlorophen

- Synthesis of zeolite from fly ash and its adsorption of phosphorus in wastewater

- Development of a continuous PET depolymerization process as a basis for a back-to-monomer recycling method

- Green synthesis of ZnS nanoparticles and fabrication of ZnS–chitosan nanocomposites for the removal of Cr(vi) ion from wastewater

- Synthesis, surface modification, and characterization of Fe3O4@SiO2 core@shell nanostructure

- Antioxidant potential of bulk and nanoparticles of naringenin against cadmium-induced oxidative stress in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus

- Variability and improvement of optical and antimicrobial performances for CQDs/mesoporous SiO2/Ag NPs composites via in situ synthesis

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Characterization and its potential biomedical applications

- Green synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using Trigonella foenum-graecum L. leaves grown in Saudi Arabia

- Intensification process in thyme essential oil nanoemulsion preparation based on subcritical water as green solvent and six different emulsifiers

- Synthesis and biological activities of alcohol extract of black cumin seeds (Bunium persicum)-based gold nanoparticles and their catalytic applications

- Digera muricata (L.) Mart. mediated synthesis of antimicrobial and enzymatic inhibitory zinc oxide bionanoparticles

- Aqueous synthesis of Nb-modified SnO2 quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene for in situ agricultural waste treatment

- Study on the effect of microwave roasting pretreatment on nickel extraction from nickel-containing residue using sulfuric acid

- Green nanotechnology synthesized silver nanoparticles: Characterization and testing its antibacterial activity

- Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens

- Hydrophilic modification of PVDF membranes by in situ synthesis of nano-Ag with nano-ZrO2

- Paracrine study of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADMSCs) in a self-assembling nano-polypeptide hydrogel environment

- Study of the corrosion-inhibiting activity of the green materials of the Posidonia oceanica leaves’ ethanolic extract based on PVP in corrosive media (1 M of HCl)

- Callus-mediated biosynthesis of Ag and ZnO nanoparticles using aqueous callus extract of Cannabis sativa: Their cytotoxic potential and clinical potential against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi

- Ionic liquids as capping agents of silver nanoparticles. Part II: Antimicrobial and cytotoxic study

- CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over In2O3 catalysts supported on aluminosilicate halloysite nanotubes

- Corylus avellana leaf extract-mediated green synthesis of antifungal silver nanoparticles using microwave irradiation and assessment of their properties

- Novel design and combination strategy of minocycline and OECs-loaded CeO2 nanoparticles with SF for the treatment of spinal cord injury: In vitro and in vivo evaluations

- Fe3+ and Ce3+ modified nano-TiO2 for degradation of exhaust gas in tunnels

- Analysis of enzyme activity and microbial community structure changes in the anaerobic digestion process of cattle manure at sub-mesophilic temperatures

- Synthesis of greener silver nanoparticle-based chitosan nanocomposites and their potential antimicrobial activity against oral pathogens

- Baeyer–Villiger co-oxidation of cyclohexanone with Fe–Sn–O catalysts in an O2/benzaldehyde system

- Increased flexibility to improve the catalytic performance of carbon-based solid acid catalysts

- Study on titanium dioxide nanoparticles as MALDI MS matrix for the determination of lipids in the brain

- Green-synthesized silver nanoparticles with aqueous extract of green algae Chaetomorpha ligustica and its anticancer potential

- Curcumin-removed turmeric oleoresin nano-emulsion as a novel botanical fungicide to control anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) in litchi

- Antibacterial greener silver nanoparticles synthesized using Marsilea quadrifolia extract and their eco-friendly evaluation against Zika virus vector, Aedes aegypti

- Optimization for simultaneous removal of NH3-N and COD from coking wastewater via a three-dimensional electrode system with coal-based electrode materials by RSM method

- Effect of Cu doping on the optical property of green synthesised l-cystein-capped CdSe quantum dots

- Anticandidal potentiality of biosynthesized and decorated nanometals with fucoidan

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Mentha pulegium, their characterization, and antifungal properties

- A study on the coordination of cyclohexanocucurbit[6]uril with copper, zinc, and magnesium ions

- Ultrasound-assisted l-cysteine whole-cell bioconversion by recombinant Escherichia coli with tryptophan synthase

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Citrus sinensis peels and evaluation of their antibacterial efficacy

- Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate/acrylic acid composite hydrogels conjugated to silver nanoparticles as an antibiotic delivery system

- Synthesis of tert-amylbenzene for side-chain alkylation of cumene catalyzed by a solid superbase

- Punica granatum peel extracts mediated the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their detailed in vivo biological activities

- Simulation and improvement of the separation process of synthesizing vinyl acetate by acetylene gas-phase method

- Review Articles

- Carbon dots: Discovery, structure, fluorescent properties, and applications

- Potential applications of biogenic selenium nanoparticles in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: A comprehensive insight on the mechanistic approach and future perspectives

- Review on functionalized magnetic nanoparticles for the pretreatment of organophosphorus pesticides

- Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: A review

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in deep eutectic solvents: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Santiago Aparicio and Mert Atilhan)

- Delignification of unbleached pulp by ternary deep eutectic solvents

- Removal of thiophene from model oil by polyethylene glycol via forming deep eutectic solvents

- Valorization of birch bark using a low transition temperature mixture composed of choline chloride and lactic acid

- Topical Issue: Flow chemistry and microreaction technologies for circular processes (Guest Editor: Gianvito Vilé)

- Stille, Heck, and Sonogashira coupling and hydrogenation catalyzed by porous-silica-gel-supported palladium in batch and flow

- In-flow enantioselective homogeneous organic synthesis