Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

-

Muluneh Bekele Haile

and Dacheng Wu

Abstract

To develop distinctive elastic fabrics, it is essential to produce new elastomeric yarns that differ from conventional elastane filaments. The elastomeric staple yarns examined in this study are composed of poly(ether-ester), or PEE, featuring a chemical structure with an 80/20 weight ratio of a rigid segment of poly (butylene terephthalate) (PBT) and a flexible segment of poly (oxytetramethylene). Initially, staple fibers were created from this elastomeric PEE along with a 25% PBT blend by weight, followed by the production of elastomeric yarns from pure elastomeric staples and blended staple fibers of cotton or poly (ethylene terephthalate) using ring and compact spinning techniques. This study provides a comprehensive overview of the manufacturing process for elastomeric yarns derived from these elastomeric staple fibers. The fundamental mechanical characteristics of the produced elastomeric yarns, such as tenacity, modulus, breaking extension, and elastic recovery, were evaluated and detailed in relation to yarn composition (blending ratio). The most significant feature of high elastic recovery (exceeding 90%) at 10–15% extension is anticipated to facilitate the creation of numerous new types of stretchy materials.

1 Introduction

Elastomeric yarns are typically defined as those that incorporate filaments made from either elastodiene or elastane polymers, noted for their exceptional extensibility and nearly complete recovery. These yarns are crucial for producing stretch fabrics that exhibit greater than average extensibility and recovery. This study created and analyzed a novel type of elastomeric yarn. This yarn consists of staple fibers made from poly(ether-ester) (PEE), which are twisted together using ring or compact spinning techniques to produce a continuous strand. The initial development of this new elastomeric yarn took place in the laboratory of the lead author of this article. A preliminary report [1] exists; however, this article aims to provide a comprehensive and thorough account. To our knowledge, there are no existing reports on similar elastomeric yarns. To substantiate the uniqueness of this yarn type, it is essential to examine the brief historical context surrounding the development of textile materials.

The evolution of textile science indicates that significant advancements and innovations in clothing for the future will primarily stem from the fabrics themselves [2]. Similarly, the progress in fabric technology is largely reliant on the development of fibers and their constituent materials. The remarkable breakthroughs in nylon, Dacron, and Lycra, pioneered by Carothers and realized by DuPont, serve as compelling evidence of this assertion. Synthetic fibers derived from the same polymer through spinning can typically be produced in two forms: filament and staple fiber, each possessing distinct advantages and limitations, and neither can fully substitute the other. They enhance one another and coexist within the marketplace. Staple fibers are usually created by cutting long tow filaments, a relatively straightforward process, while the subsequent yarn production is intricate and predominantly achieved through ring spinning. Elastomeric fibers made from segmented polyurethane, commonly referred to as spandex, Lycra, or elastane, emerged in the latter half of the twentieth century. These fibers can extend beyond 500% and promptly return to their original lengths, a crucial characteristic for the production of elastic fabrics tailored to specific applications. However, the segmented polyurethane elastomeric fiber currently exists solely in filament form. Consequently, this study aims to investigate the production of elastomeric staple fibers, which can subsequently be transformed into elastomeric yarn using a ring spinning machine.

Since its introduction in the United States in 1828, ring spinning has undergone continuous enhancements, establishing itself as the predominant spinning process equipment. Initially utilized for pure cotton, it has since been adapted for wool and linen, and further diversified to accommodate various pure and blended rayon and synthetic staple fibers. Recent data indicate that the global textile industry still operates with 250 million ring spinning spindles, representing approximately 80% of the total spinning market [3]. Despite the significant variability in the mechanical properties of different textile fibers, the fundamental mechanical characteristics of textile materials, whether natural or synthetic, remain crucial [4]. The range of variation includes tenacity from 1 to 6 cN/dtex and breaking elongation from 2 to 50%. These metrics are vital for textile processing and end-use applications. The ring spinning method is generally compatible with the spinning of most textile fibers, requiring only minor adjustments. Conversely, it is recognized that the basic mechanical properties of rubber threads and polyurethane elastomeric fibers differ markedly from those of conventional fibers. Elastomeric fibers typically exhibit low strength (<1 cN/dtex), significant elongation (>500%), high elastic recovery, and a very fine single fiber fineness (>10 dtex). Although they can be processed into staple fibers, spinning them into yarns using traditional ring spinning machines poses considerable challenges. To date, there are only a limited number of reports documenting the successful spinning of elastomeric staple yarns.

PEE is an innovative material ideal for producing elastomeric fibers. Numerous studies, including those by Varma et al. and Gogeva et al. [5,6], have documented the laboratory-scale production of elastomeric filaments. However, at the Research and Development Platform of Chengdu Textile College, we have successfully developed a novel elastomeric staple fiber made from PEE for industrial pilot production, achieving an impressive elastic recovery exceeding 95% at 40% elongation [7]. According to a brief communication [8], this material demonstrates superior characteristics compared to elastane, including high tenacity (∼2 cN/dtex), low elongation (∼50%), and fiber fineness as low as ∼1 dtex, enabling the production of new elastomeric yarns using a ring spinning machine.

This article presents a comprehensive analysis of the production of elastomeric yarns derived from elastomeric staple fibers and their combinations with cotton and PET staple fibers through ring and compact spinning techniques. The fundamental mechanical properties of the resulting elastomeric yarns were evaluated and discussed. It is widely recognized that the blending of various fiber types is a common practice aimed at improving both the performance and aesthetic appeal of fabrics. Blended yarns, which incorporate both natural and synthetic fibers, offer the unique benefit of merging the advantageous characteristics of each fiber type, such as comfort and ease of maintenance. These benefits also facilitate a broader range of product offerings and provide a competitive marketing edge. Consequently, this article primarily examines the impact of the blending ratio on the fundamental properties of elastomeric yarns.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Raw materials

The precise chemical nomenclature of PEE utilized in this investigation is block-copolymer poly (butylene terephthalate) (PBT)-block-(tetramethylene oxide), with the chips sourced from First Fiber Co. Limited. In the chemical structure of this thermoplastic elastomer (PEE1), the hard segment is PBT, while the soft segment is poly (oxytetramethylene), maintaining a weight ratio of 80/20. This material is designated as PEE1 in this analysis. The intrinsic viscosity of PEE1 is 1.3 dL/g at 25 ± 0.01°C in a 1:1 mixture of phenol and tetrachloroethane, with a melting point of 214.7°C and a density of 1.23 g/cm3. The other raw material for the polymer chips is PBT, obtained as an industrial product from Jiangsu Yi Zhen Co., with an intrinsic viscosity of 0.98 dL/g at 25 ± 0.010°C in a 1:1 mixture of phenol and tetrachloroethane. The combination of PEE1 and PBT also demonstrates rubber-like elasticity and is referred to as PEE2 in this research. The staple fibers of cotton and PET were purchased from the commodity market, and all materials are considered as acceptable products.

2.2 Staple fibers: PEE1 and PEE2

The staple fibers PEE1 and PEE2 were produced utilizing the aforementioned chips of PEE1 and PEE2 through the melt spinning process at the Fiber Materials Innovation Center located at Chengdu Textile College. The fabrication conditions and technological parameters were consistent with those outlined in the study by Haile et al. [7].

2.3 Production of elastomeric yarns by ring and compact spinning

The elastomeric yarns are manufactured using staple fibers from PEE1 and PEE2, along with their blends with PET staple fiber and cotton, following the specified technological process and parameters.

2.3.1 Carding

Due to the fiber’s elastic properties, the crimping effect is not permanent. To mitigate damage to the fiber, the process was conducted at a reduced speed and with minimal tension. The sliver was quantified at 23.0 g for every 5 m by setting the distance between the cylinder and the cover to 0.30, 0.28, 0.28, 0.28, and 0.30 mm, thereby improving the smoothness of each clothing.

2.3.2 Draw frame

Due to the shrinkage of the short elastic fibers, the draw frame was operated at a reduced speed, with minimal tension and low draft, necessitating the regulation of air conditions. The roller speed was maintained at 300 rpm, with top roller pressures set at 392, 294, and 392 N, while the draft ratio was modified to 6 to manage the movement of floating fibers during the drawing process. Additionally, to ensure the effective retention of the elastomeric staple fibers, three phases, specifically phases 5, 6, and 7, were utilized.

2.3.3 Roving

To facilitate yarn formation, air conditioning was regulated to minimize electrostatic properties. Low pressure, reduced speed, minimal tension, and small packages were employed. The roving twist factor was determined to be 52.9, with a sliver weight of 5.0 g per 10 m. Excessive twisting may hinder the effective performance of subsequent processes, and the tension on the guide bar should remain moderate.

2.3.4 Ring frame

The comprehensive analysis of the spinning experimental data revealed a total draft multiple of 34.2. The spinning performance improved with a break draft of 1.23, and to achieve yarn with reduced hairiness, the EMI4/0 traveler was employed.

2.3.5 ESPERO-M winder

An electronic yarn clearer was selected to minimize detrimental yarn defects. To decrease the frequency of excessive end breaks, a reduced winding speed was implemented, and the dimensions of the package should remain modest.

2.3.6 Compact spinning machine

The technological procedure of compact spinning was finalized using a custom-built test compact spinning machine. The parameters of the process were modified in accordance with the aforementioned ring spinning.

2.4 Testing equipment and methods

2.4.1 Tension test of elastomeric yarn on the spinning frame

A tension test was performed on a sample spinning machine manufactured by Tianjin Jiacheng Electromechanical Equipment Co., Ltd, utilizing a tension meter model YG302 produced by Changzhou First Textile Equipment Limited. The test range of the tensiometer was from 0 to 100 cN.

2.4.2 Tensile test of elastomeric yarn

The tensile properties were determined utilizing a YG065C electronic fabric strength meter from Shandong Laizhou Electronic Instrument Co., Ltd. The conditions for the stress-strain tests were established as follows: a yarn clamping length of 25 cm and a stretching speed of 100 mm/min. The tests were conducted at a temperature of 20°C and a humidity level of 65%. The samples were held for a duration of 10 s, and the outcomes of 100 trials were averaged. The elastic recovery was measured at fixed elongations of 5, 10, 15, and 20% over six cycles. The parameters included a clamping length of 25 cm, with the rate of elongation varying from 50 to 250 mm/min based on the fixed elongation, and a pretension of 3–5 cN, contingent upon the yarn’s linear density. Throughout the measurement process, the sample was maintained at a temperature of 20°C and a humidity of 65%, with the results of ten experiments averaged.

2.4.3 Observation of elastomeric yarns by electron microscope

Images of elastomeric yarns were captured using the JSM-IT800 scanning electron microscope, manufactured by JEOL (Japan Electron Optics Laboratory Co., Ltd).

2.4.4 Measurement of yarn twist

The measurement of twist was carried out with the YG155A apparatus. According to the ASTM D 1423 standard, the twist in turns was determined using the direct counting method, applying a load of 20cN and a gauge length of 50 cm. The results are presented in turns per meter (TPM), with the average calculated from ten tests.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Basic properties of raw fibers

The fundamental characteristics of raw fibers utilized in the manufacturing of both homogeneous and blended elastomeric yarns are presented in Table 1.

Basic properties of raw fibers used for the production of elastomeric yarns

| Fiber | Fineness (dtex) | Staple length (mm) | Tenacity (cN/dtex) | Elastic modulus (cN/dtex) | Breaking elongation (%) | Elastic recovery at 10% elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEE1 | 1.56 | 39.1 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 104 | >99 |

| PEE2 | 2.03 | 39.1 | 2.20 | 1 | 65 | >99 |

| PET | 1.56 | 38 | 4.94 | 110 | 14 | |

| Cotton | 1.461 | 31 | 2.5 | 71 | 5.5 | |

| Elastane2 | >15 | Continuous | 0.5–1.0 | 0.04 | 500–700 | 100 |

1This value is converted from the micronaire value (3.85) measured experimentally.

2The data of elastane are listed according to Ref. [9]. No elastane fibers were used in this work.

3.2 Basic properties of obtained elastomeric yarns

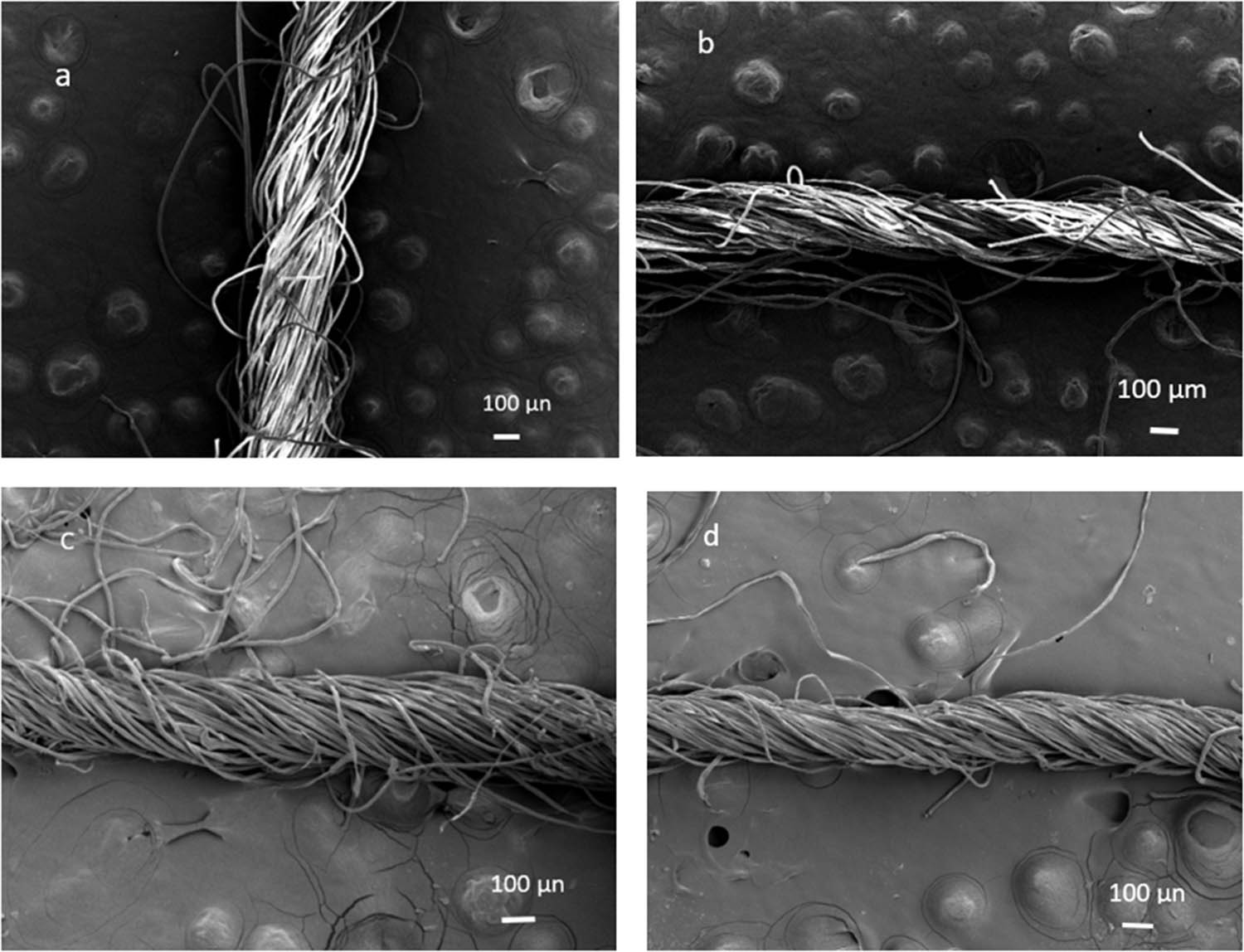

Figure 1 illustrates the electron microscope observations of typical elastomeric yarns, showcasing the true twist helical and parallel arrangement of staple fibers, similar to other staple spun yarns [10]. This arrangement is a natural consequence of the ring and compact spinning processes. Ring spinning, being the predominant technology for producing staple yarns, has been modified in compact spinning. In the ring spinning process, staple fibers are intertwined to create a robust yarn. The operation of ring spinning machines involves three key steps: (1) Attenuation (or drafting) of roving or sliver to achieve the desired linear density; (2) insertion of twist to form a cohesive yarn; (3) winding the yarn onto a suitable package. This study successfully produced elastomeric yarns from elastomeric staple fibers and their blends with cotton and PET staples using ring and compact spinning techniques.

Electron microscope photographs of typical representatives of elastomeric yarns: (a) PEE1 and (b) PEE1/COT (50/50) by ring spinning; (c) PEE2/PET (50/50) and (d) PEE2 compact spinning.

The yarns examined in this study were subjected to a “Z” twist, as indicated in Figure 1 and confirmed through twist testing. Twist is typically quantified as the number of turns per unit length, expressed in terms of turns per meter or turns per inch. Table 2 displays the averaged results pertaining to the twist of elastic yarns.

Average twist of elastic yarns

| Yarns | Twist (turns/m) |

|---|---|

| PEE1 | 664 |

| PEE21 | 729 |

| PEE1/PET 60/40 | 869 |

| PEE1/PET 20/80 | 546 |

| PEE2/PET 50/501 | 452 |

| PEE1/COT 20/80 | 896 |

| PEE1/COT 35/65 | 881 |

| PEE1/COT 50/50 | 859 |

| PEE1/COT 55/45 | 922 |

| PEE1/COT 65/35 | 911 |

| PEE1/COT 80/20 | 905 |

1This elastomeric yarn was made by ring spinning, while all the others were made by compact spinning.

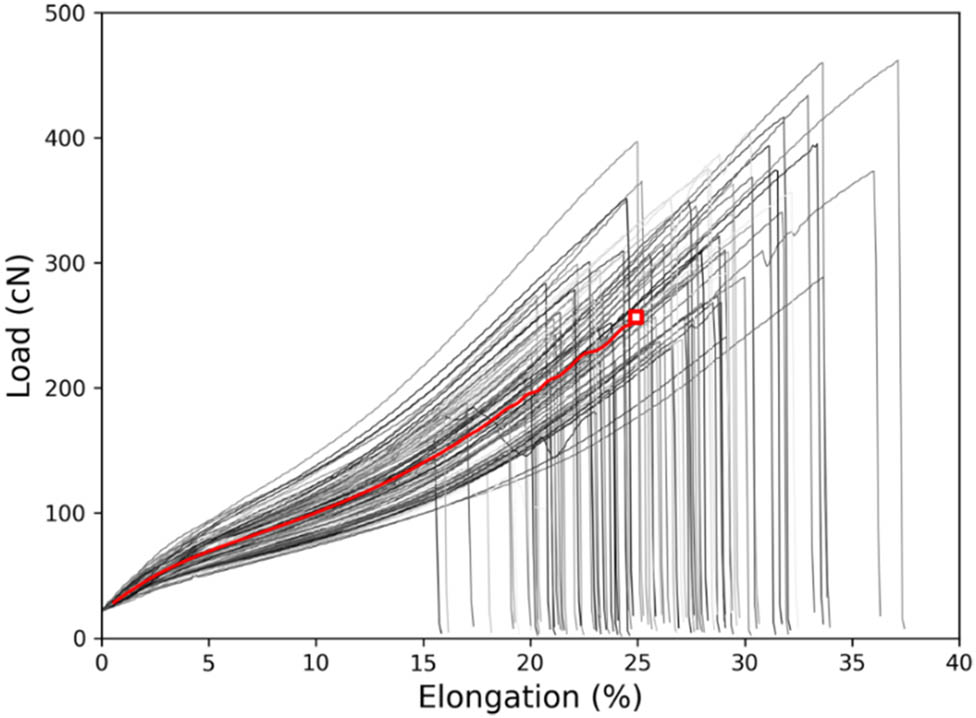

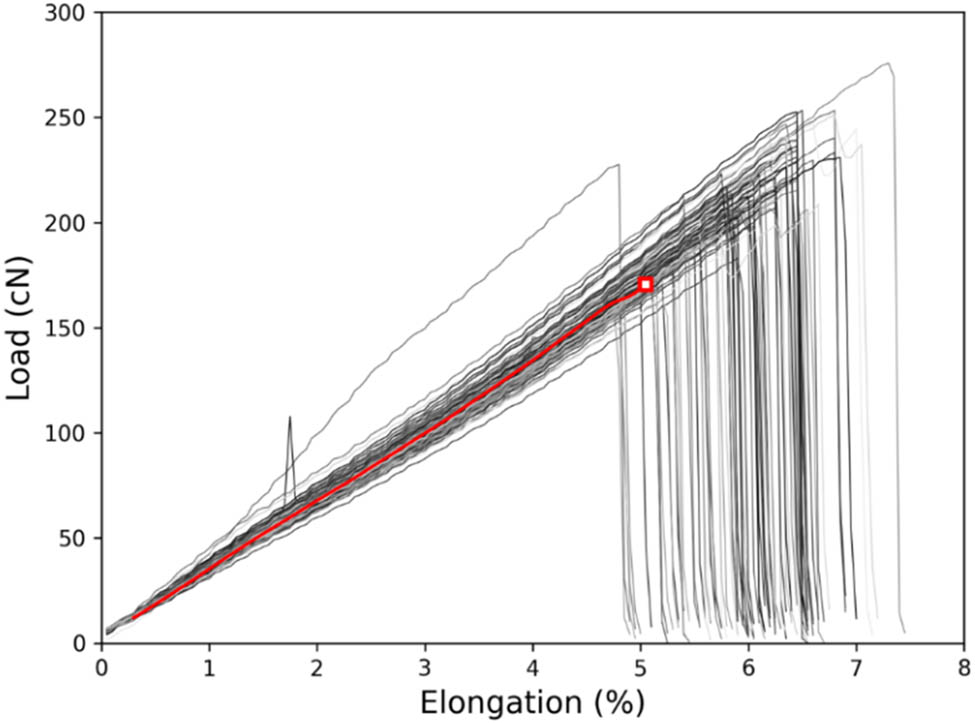

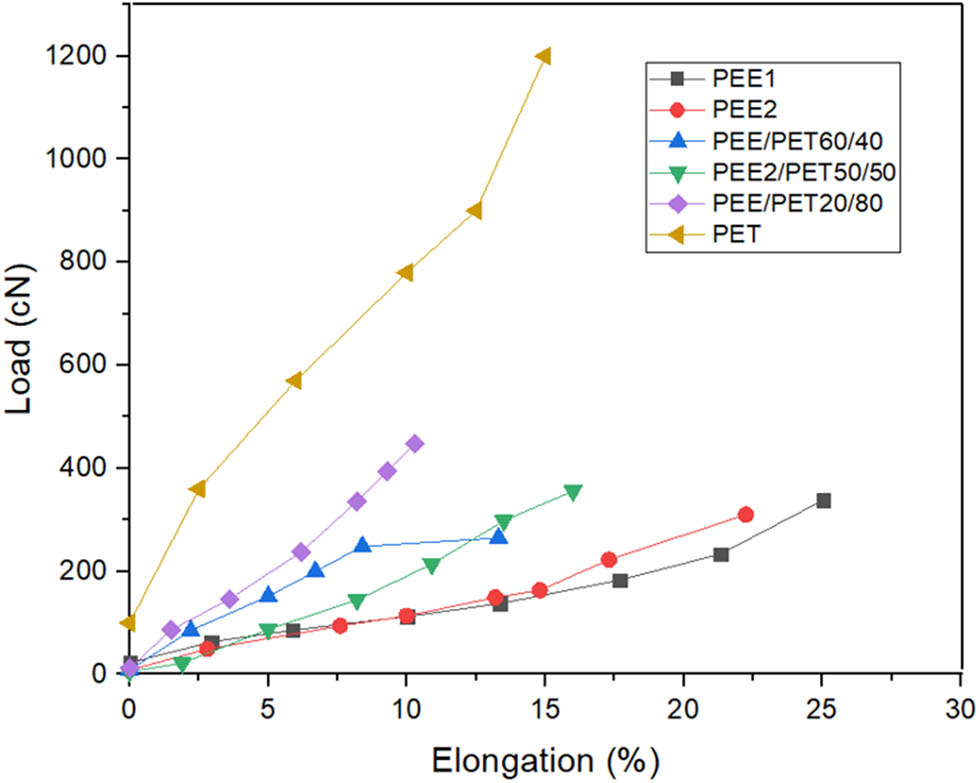

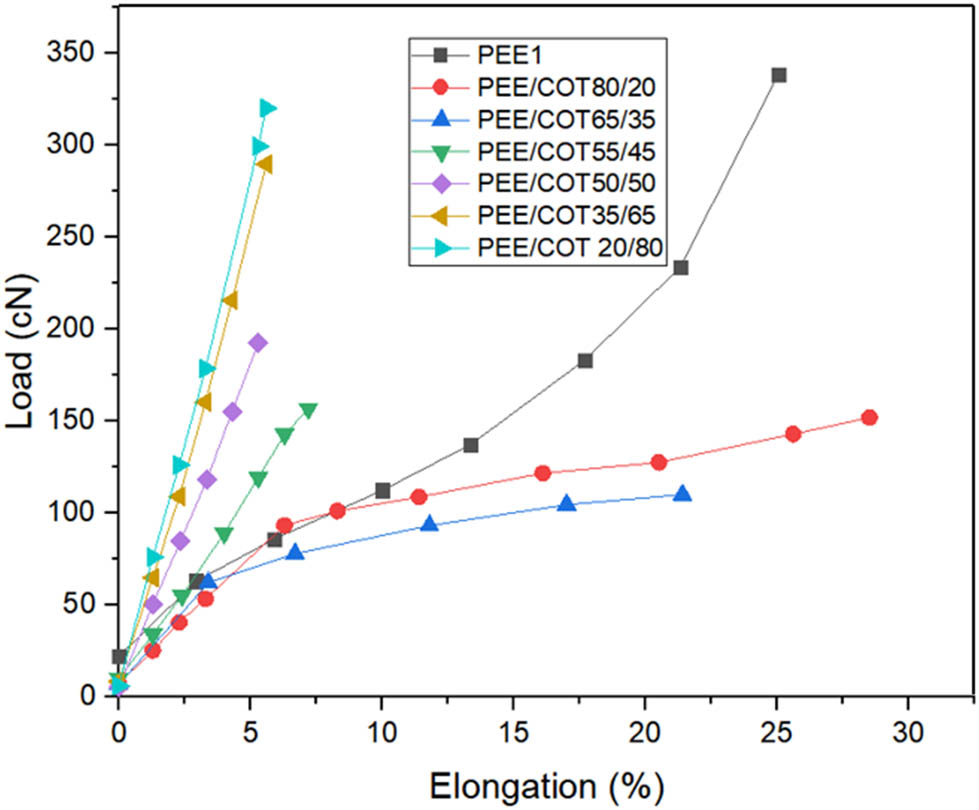

The elastomeric yarns obtained, similar to other types of yarn, exhibited significant irregularities during the experimental tensile testing, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, which demonstrate considerable variation. To derive the “average load-elongation curves” or standard load-elongation curves [8], these data must be averaged through appropriate calculations. The curves generated from this analysis are also indicated in the two figures, confirming their representativeness. All tensile test data are included in this calculation, and the resulting average load-elongation curves are summarized in Figures 4 and 5. As depicted in Figure 4, the stress-strain characteristics of PEE1 yarn are quite similar to those of PEE2 yarn, particularly during the initial and primary stages of the curve, which aligns with the fact that both were made from homogeneous elastomeric staple fibers with fundamental properties.

Experimental load–elongation curves for PEE1 elastomeric yarn and its “average load-elongation curve” (the red curve).

Experimental load–elongation curves for PEE1/COT 50/50 elastomeric yarn and its “average load-elongation curve” (the red curve).

Average load–elongation curves of pure PEE and PEE/PET yarns.

Average load–elongation curves of PEE/COT yarns.

The analysis of the load–elongation curves presented in Figure 4 indicates that the homogeneous elastomeric yarn exhibits the lowest modulus and tenacity, while demonstrating the highest breaking elongation. In contrast, PET yarn displays the highest modulus and tenacity, accompanied by the lowest breaking elongation. As the proportion of PET in the blend increases, the curve progressively shifts from the characteristics of PET to those of the homogeneous elastomeric yarn, reflecting a clear pattern that aligns with the conventional theoretical framework of blend spinning, which will be elaborated upon subsequently. However, this regularity is not observed in the elastomeric staple fiber-cotton system. Figure 5 illustrates that within the load elongation curve group of various elastomeric yarns, the homogeneous elastomeric yarn PEE1 occupies a median position. Upon incorporating cotton into the blend, the curve does not exhibit a straightforward upward or downward trend; it is only when the cotton weight percentage exceeds 50% that a distinct inclination towards the curve of elastomeric yarn characterized by high tenacity, high modulus, and low breaking elongation becomes evident. For the two types of blended elastomeric yarns with lower cotton content, their modulus and tenacity are reduced compared to homogeneous elastomeric yarns, while their breaking elongation is increased. This observation poses a challenge to traditional blended spinning theory and warrants further investigation. We will explore potential explanations for this phenomenon through an analysis of the mechanics involved in yarn formation.

The fundamental mechanical characteristics are detailed in Table 3. Alongside Figures 4 and 5, this table provides a comprehensive overview of the essential mechanical performance of the elastomeric yarns produced in this study.

Basic properties of elastomeric yarns made by ring and compact spinning

| Yarns | Breaking elongation (%) | Tenacity (cN/tex) | Modulus (cN/dtex) | Linear density (tex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEE1 | 25.0 ± 5.4 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 22.5 |

| PEE21 | 22.2 ± 1.5 | 13.1 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.9 | 22.4 |

| PEE1/PET 60/40 | 13.3 ± 4.7 | 6.57 ± 0.5 | 20.4 ± 2.6 | 20.0 |

| PEE1/PET 20/80 | 10.4 ± 0.6 | 16.0 ± 1.7 | 21.6 ± 2.4 | 28.0 |

| PEE2/PET 50/501 | 13.2 ± 1.3 | 19.1 ± 2.0 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 17.0 |

| PEE1/COT 20/80 | 5.58 ± 0.38 | 16.0 ± 1.2 | 28.0 ± 1.1 | 19.0 |

| PEE1/COT 35/65 | 4.42 ± 0.41 | 11.6 ± 1.1 | 23.5 ± 2.7 | 19.0 |

| PEE1/COT 50/50 | 5.23 ± 0.57 | 13.5 ± 1.3 | 23.5 ± 2.9 | 14.0 |

| PEE1/COT 65/35 | 18.8 ± 0.8 | 7.37 ± 0.9 | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 20.1 |

| PEE1/COT 80/20 | 28.6 ± 2.9 | 7.07 ± 0.9 | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 20.0 |

| PET | 14.87 ± 0.74 | 22.0 ± 1.5 | 27.9 ± 1.5 | 55.5 |

| COTTON2 | 7.06 ± 0.69 | 18.4 ± 1.2 | 36.8 ± 0.8 | 29.2 |

1These elastomeric yarns were made by ring spinning, while all others were made by compact spinning.

2The data on cotton yarn were taken from Ref. [11].

3.3 Effect of blending ratio on mechanical properties of blended elastomeric yarns

The blending of various fibers enables us to achieve optimal yarn properties for their intended applications. Additionally, the blending technique can enhance the processability of staple fibers during spinning. Given the significant elasticity of elastomeric staple fibers, they can pose considerable challenges in the spinning process, necessitating greater focus on the blending system. The impact of blending is reflected in the changes in properties of elastomeric yarns corresponding to the blending ratio.

In this study, PET staple fibers or cotton were blended with the elastomeric staple fibers PEE1 or PEE2 to create blended elastomeric yarns. The variation in mechanical properties between the staple fibers PEE1 and PEE2 is significantly less than that observed between the traditional staple fibers (PET or cotton) and the elastomeric staple fibers. Consequently, in the subsequent graphs (Figures 6–11) that illustrate the changes in properties with varying blend compositions, the elastomeric fibers PEE1 and PEE2 are not differentiated, and the term PEE is used collectively for both.

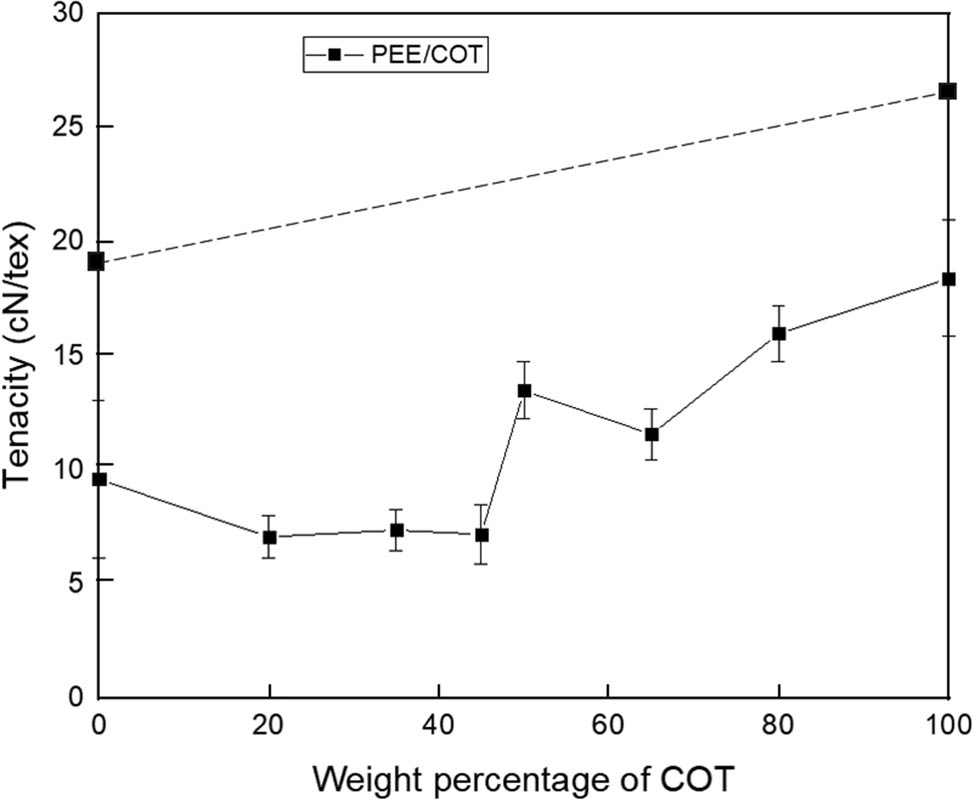

Tenacity vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE/COT.

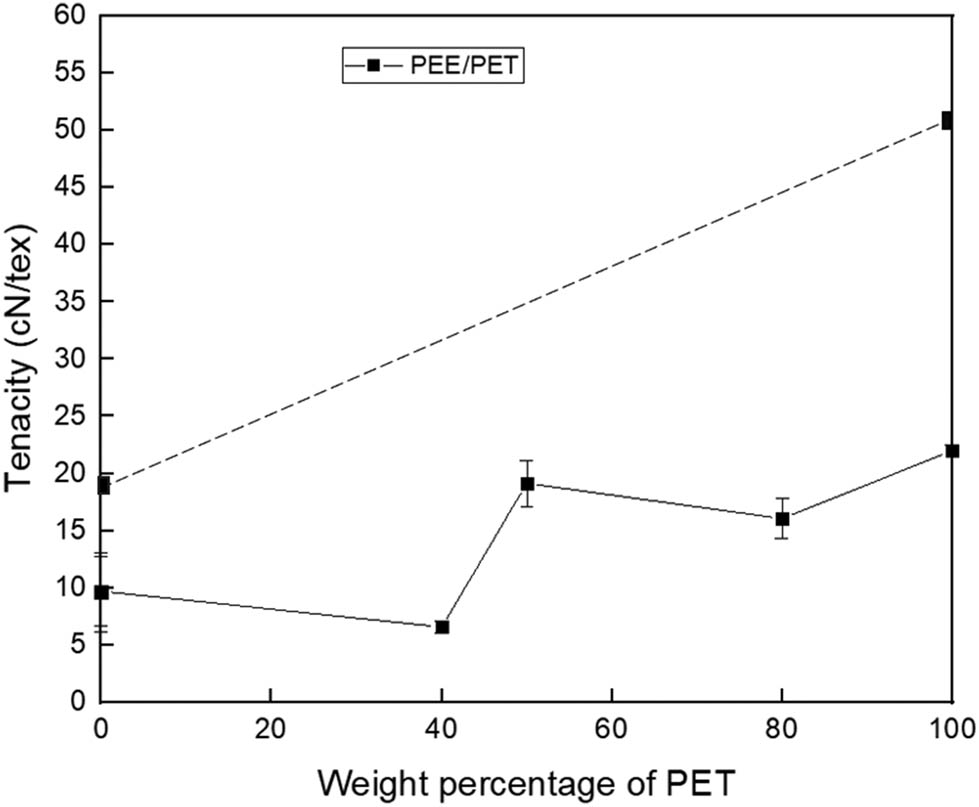

Tenacity vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE-PET.

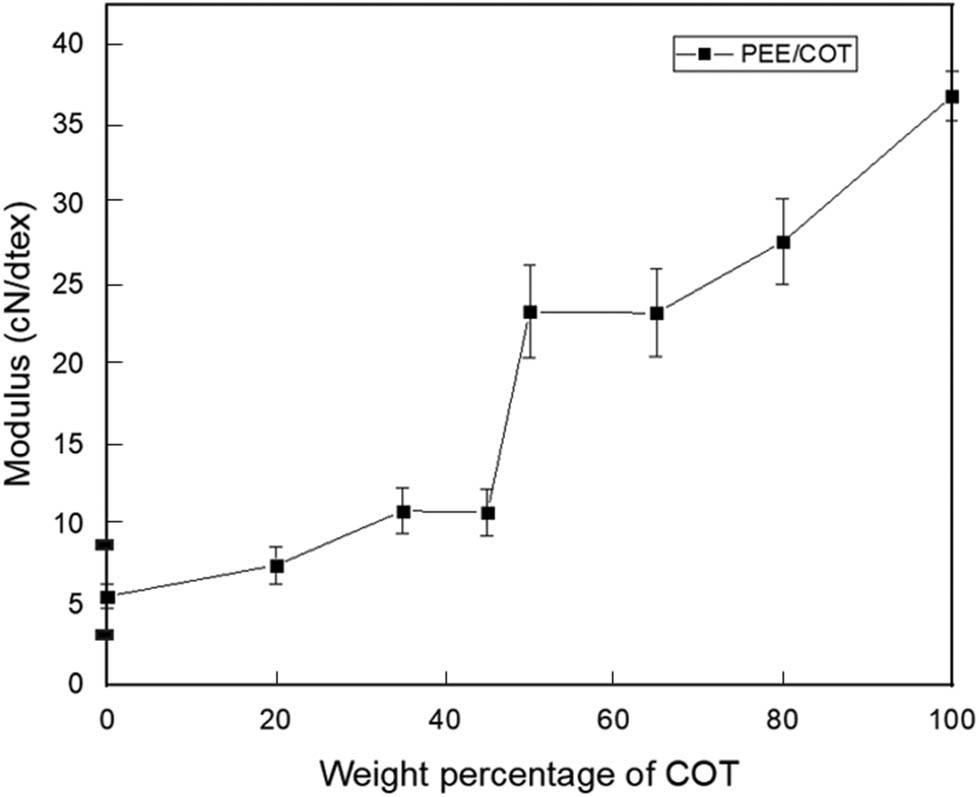

Modulus vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE/COT.

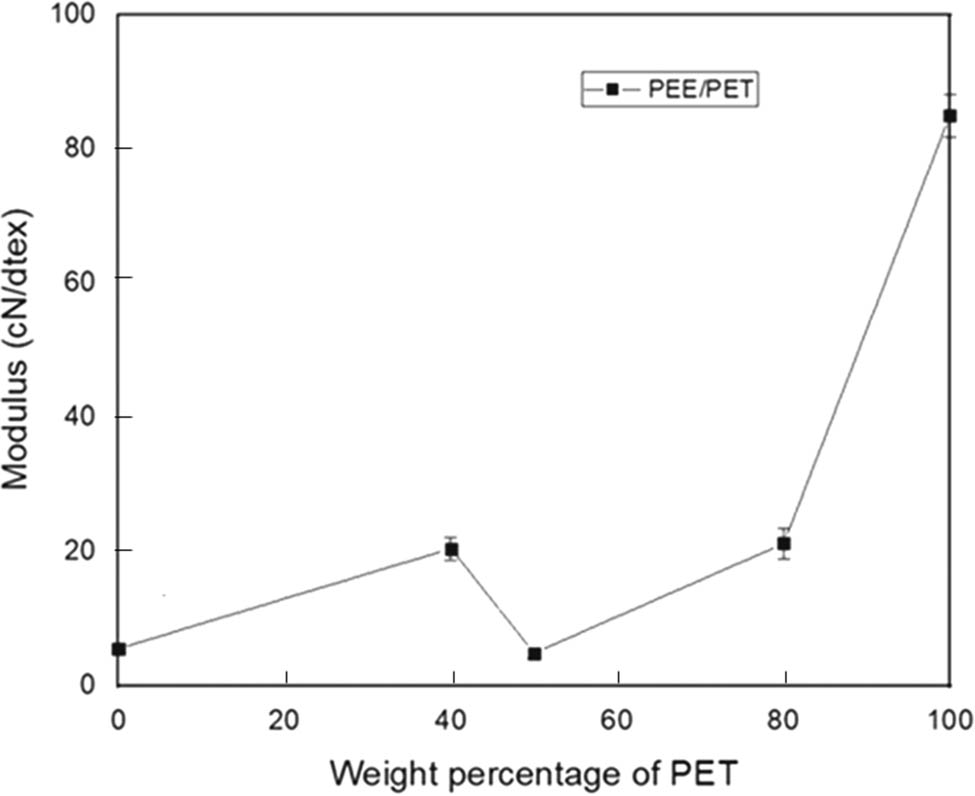

Modulus vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE-PET.

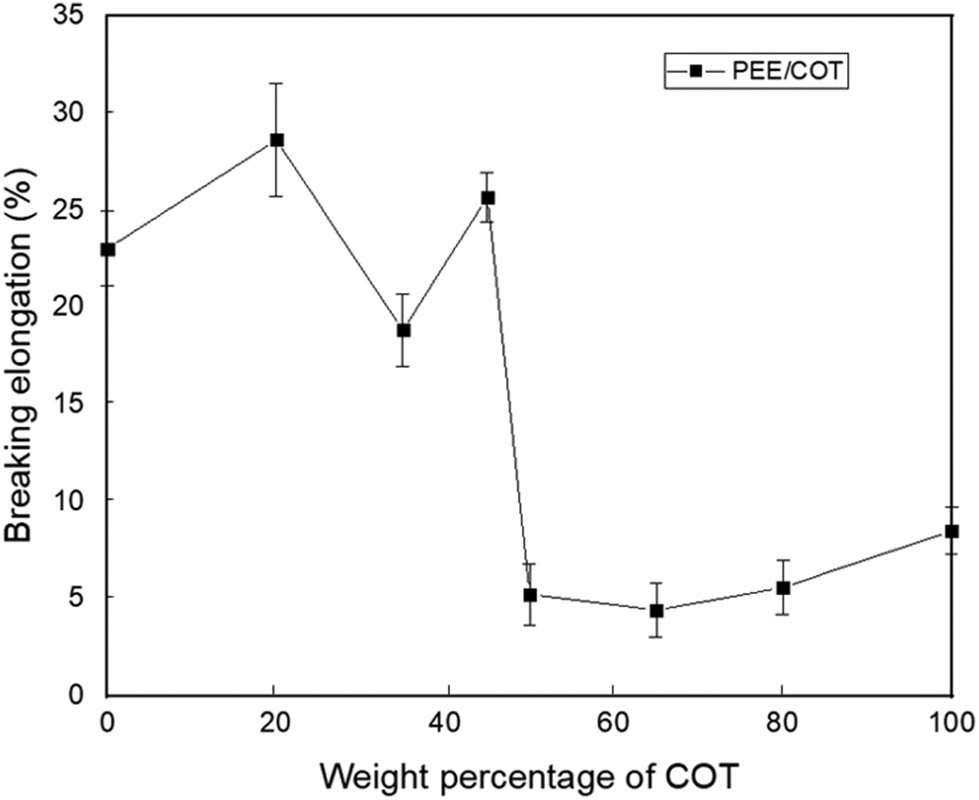

Breaking elongation vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE/COT.

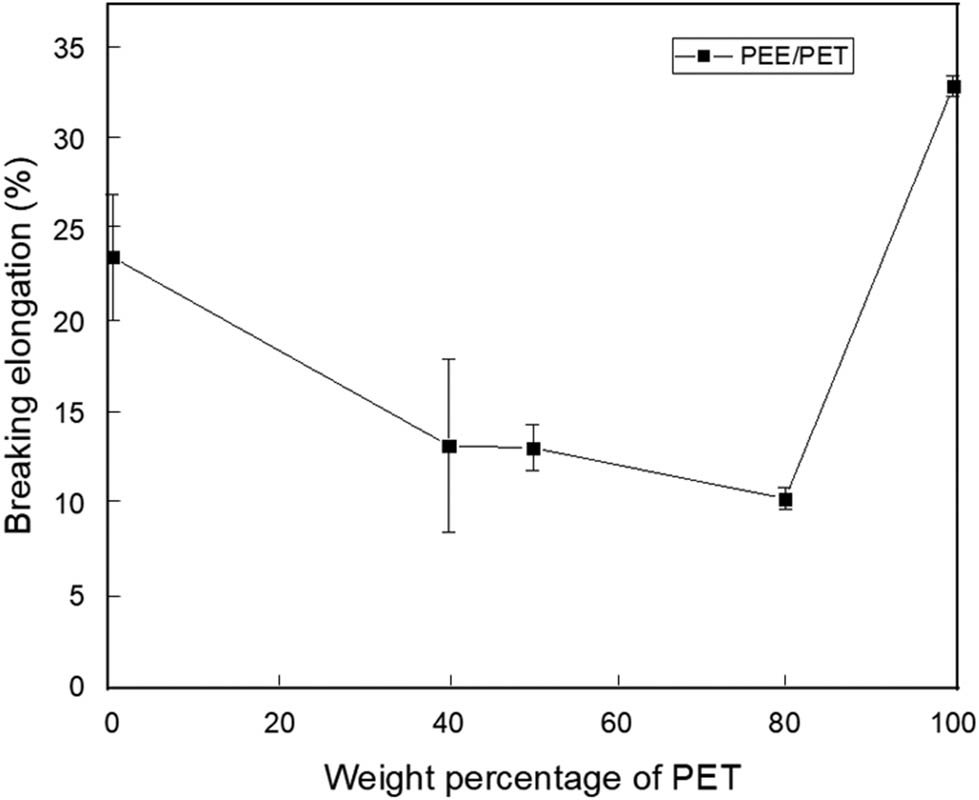

Breaking elongation vs weight percentage for blended yarns PEE-PET.

The mechanical characteristics of yarns present a multifaceted challenge, influenced by the properties of the constituent fibers and the yarn structure itself. The latter is determined by the type of spinning machine and its operational conditions, as the force and thermal histories that the fiber bundle undergoes during yarn formation are critical factors in shaping the yarn structure. The inherent complexity associated with high elastic deformation in elastomeric fibers and yarns complicates the establishment of straightforward and definitive guidelines. Consequently, this study offers only a phenomenological overview of the spinning process for elastomeric staple fibers utilizing ring and compact spinning machines.

The process of spinning multi-component staple fibers is notably more intricate and challenging. One of the earliest instances of semi-quantitative research is the relationship between the tenacity and composition of nylon and cotton staple fibers in bicomponent ring spinning. Coplan [12] demonstrated that the tenacity-composition curve of the blended yarn can be derived from that of the mixed fibers by taking into account three diminishing factors: bundle strength, Peirce’s “Weak Link,” and a twisted angle of 20 degrees. His groundbreaking research significantly enhances our comprehension of the tensile properties of blended yarns (refer also [13]).

An analogous analysis can be performed and comprehended for the two systems examined in this study, namely, PEE-cotton and PEE-PET staple, as illustrated in Figures 6 and 7, where the dashed line at the top signifies the reference standard connecting the tenacity of the two staples in accordance with Coplan’s treatment.

The variations in elastic modulus with respect to composition for these two systems are illustrated in Figures 8 and 9.

As per a simplified theory regarding staple fiber yarn [10], if the stress–strain curve of the fiber adheres to Hooke’s law, the tenacity and modulus of yarn produced through ring spinning are related to the tenacity and modulus of individual fibers in the following manner:

where σ and E are the tenacity and modulus, subscript y and f represent yarn and fiber, respectively, α is the twist angle, and k is expressed by the following equation:

where Lf is the fiber length, a is the fiber radius, Q is the migration period, and μ is the coefficient of friction.

The analysis of equation (1) indicates that the ratio of tenacity or modulus is typically less than 1. However, the friction coefficient within the equation poses measurement challenges and lacks consistency, complicating the calculation of an accurate value. Nevertheless, a comparison of the data presented in Tables 1 and 3 demonstrates that for the yarns composed of homogeneous fibers examined in this study, specifically PEE1, PEE2, PET, and cotton yarns, the tenacity and modulus of the yarns are indeed lower than those of the corresponding fibers. The sole exception to this observation is that the modulus of homogeneous PEE yarns exceeds that of the corresponding PEE fibers. This indicates that the experimentally established modulus relationship between homogeneous elastomeric yarn and its corresponding elastomeric fiber does not align with the prevailing theoretical framework.

The relationship between breaking elongation and composition for the two systems of elastomeric yarns is illustrated in Figures 10 and 11. In comparison to the homogeneous elastomeric yarn of the PEE-cotton system, the introduction of the second component (cotton), which has a lower breaking elongation, did not result in a decrease in the breaking elongation of the blended elastomeric yarns (Figure 10). Conversely, when the cotton content exceeded 50%, the breaking elongation of the blended yarns experienced a significant decline, aligning with the lower values characteristic of cotton yarn. This finding is noteworthy from a practical perspective, as it indicates that a cotton percentage below 50% is necessary to maintain adequate breaking elongation for elastomeric yarns. Additionally, the trend observed in the breaking elongation vs composition for the PEE-PET system markedly differed from that of the PEE-cotton system. These observations present complexities that are not easily explicable and warrant further investigation in future research.

3.4 Mechanical principle of elastomeric yarn formation

The compact spinning machine represents an enhanced version of the traditional ring spinning machine. Its primary innovation lies in the incorporation of a gathering device at the output end of the front roller, which allows for the yarn to be collected and twisted prior to output. This process effectively minimizes or even eliminates the twisting triangle area, resulting in a denser finished yarn. Nevertheless, the underlying principles governing both types of yarn spinning remain consistent and can be examined in conjunction. In the theoretical exploration of the ring spinning machine’s operational principles, the mechanics of the balloon within the spinning line are critically analyzed, focusing on the force and energy balance of a yarn element. A comprehensive mechanical analysis typically considers the centrifugal force acting on the yarn, the air friction affecting its movement, and the equilibrium of yarn tension, while often overlooking potential energy and the energy fluctuations resulting from balloon instability.

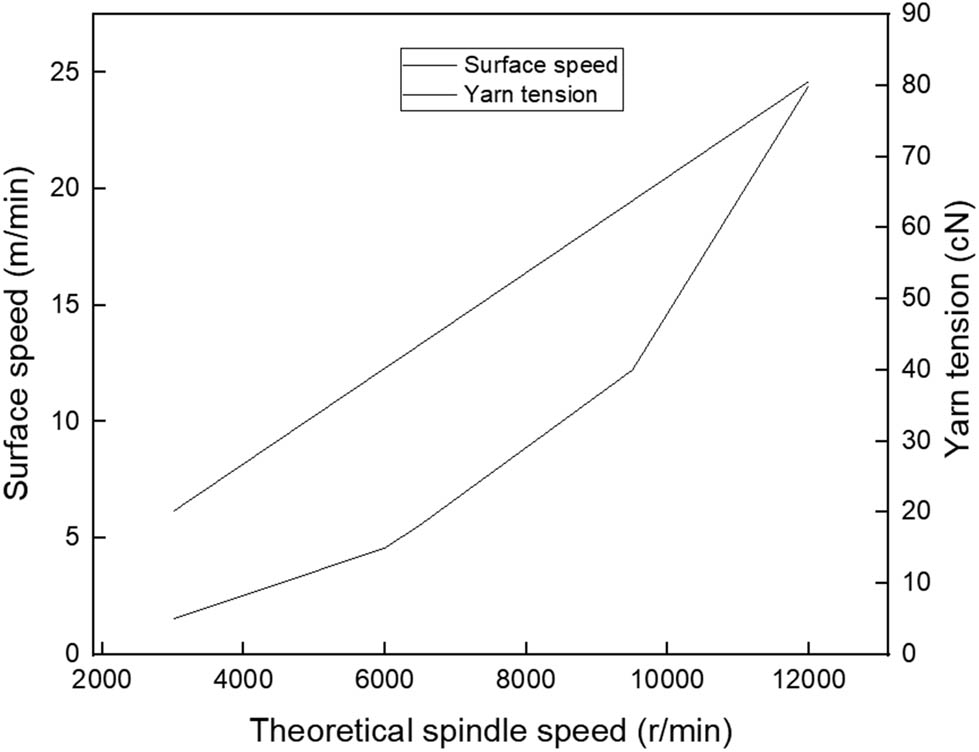

It has been observed that for cotton yarns ranging from 8 to 38 tex, a spindle speed of 12,000 rpm results in a tension range of 20–40 cN [15]. This study examines the variations in tension of elastomeric yarn as the spindle speed of the spinning machine is altered, as illustrated in Figure 12.

Experimental dependence of surface speed (the top curve) and tension (the bottom curve) on theoretical spindle speed for elastomeric yarn.

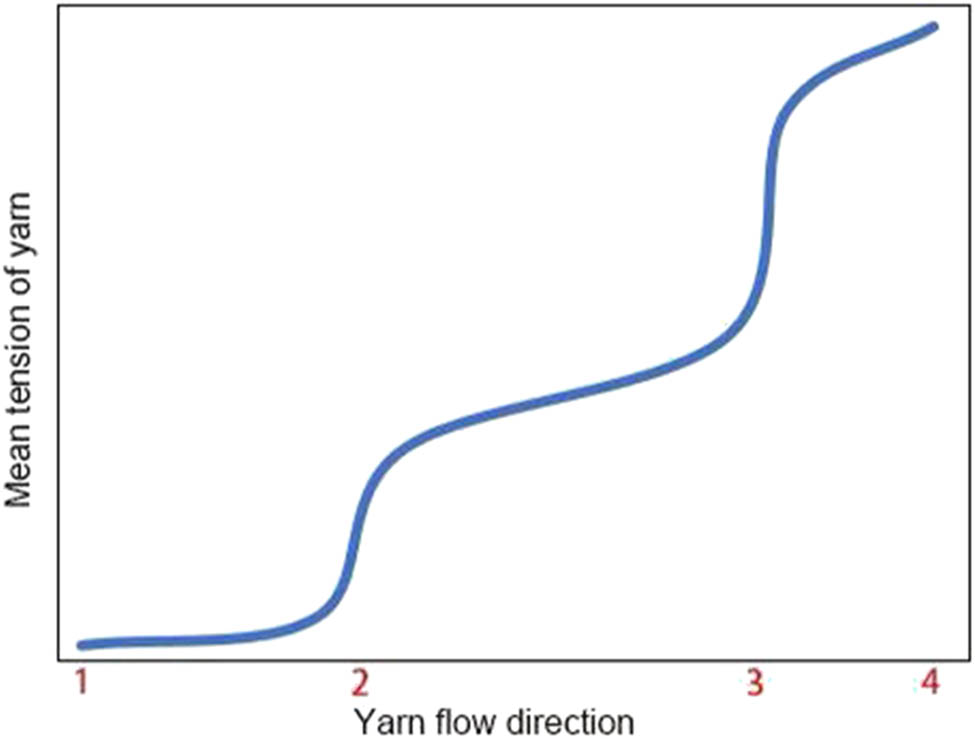

In accordance with Lord’s concepts and the data presented in Figure 12, we can create a schematic representation of the tension variations in the elastomeric yarn during the ring spinning process over the balloon line, which will aid in comprehending the spinning dynamics of elastomeric yarns. Observing from the perspective of yarn flow, beginning at point 1 and progressing through points 2 and 3 to point 4, which corresponds to the upper, middle, and lower sections of the spinning balloon illustrated in Figure 13. Upon reaching point 4, the winding point of the yarn cop, the tension in the yarn attains its peak value.

![Figure 13

Schematic diagram of a typical ring spinning machine (based on Ref. [14]).](/document/doi/10.1515/aut-2025-0061/asset/graphic/j_aut-2025-0061_fig_013.jpg)

Schematic diagram of a typical ring spinning machine (based on Ref. [14]).

In the tension distribution of the spinning balloon [16], there are two leaps at positions 2 (guide) and 3 (traveler) in Figure 14. Both of them are related to the solid friction of the yarn with spinning machine parts, which are expressed mathematically by Amontons’ law [4] as

where F is the frictional force acting parallel to the surface in a direction opposing relative movement, µ is the coefficient of friction, and N is the force normal to the surfaces in contact. When a yarn passes round a guide, as passing positions 2 and 3, its tension must be increased by an amount necessary to overcome the frictional resistance, following an approximate equation derived from (3)

where T 2 is the leaving tension, T 1 is the incoming tension, and θ is the angle of contact. For example, the position of the balloon at Tensions 2 or 3 has very different contact angles around the guide in Figure 13, which leads to a great difference in friction force and can be regarded as a periodic fluctuation.

Schematic distribution of mean tension of yarn in yarn flow direction: 1. drafting roll, 2. guide, 3. traveler, and 4. winding point at the cop.

The mechanical examination of the aforementioned spinning balloon serves merely as a simplified representation, whereas the actual tension is dynamic and subject to fluctuations. The tension experienced by the yarn at various positions is in a constant state of change, characterized by both periodic and random variations [16]. Additionally, the yarn on the spinning machine is influenced by a specific torque due to the rotation of the balloon, leading to genuine twisting. Consequently, the staple fiber bundles within the yarn create a parallel spiral arrangement that is twisted. During the formation of the yarn, the tension is maintained through the friction among the fibers, ensuring that each fiber remains in a state of straight force, secured by the twisting process. It is important to note that in this state of stress, significant differences in modulus result in substantial tensile deformation of the elastomeric staple fibers, while the other components experience only minor tensile deformation. Upon the removal of external tension, the internal dimensions of the yarn also experience stress relaxation, reverting to their original length. As the parallel mixed fiber bundle contracts, the standard staple fibers initially return to their original length, whereas the elastomeric staple fibers retain some elongation and require further relaxation. As the elastomeric staple fibers continue to contract, the other components must bend until the elastomeric fibers return to their original length, thereby preserving the configuration of the yarn.

The tension in blended elastic yarn operates in a manner opposite to the previously described process: initially, ordinary fibers are aligned solely through winding, requiring minimal force. The primary resistance to external forces in fiber bundles is provided by elastomeric fibers. As stretching continues and ordinary fibers become straightened, their high modulus enables them to contribute to the resistance of the fiber bundles against external forces. This approach effectively elucidates why blended elastic yarns retain significant elasticity. In summary, based on the mechanical principles of yarn formation, the structure closely resembles that of elastane-covered yarn when elastomeric fibers are predominant. Conversely, a higher weight percentage of cotton or PET fibers results in a traditional blended yarn’s hybrid structure. Therefore, the structural model’s predictions align with the mechanical behavior observed in elastomeric yarns, although further experimental validation is required.

3.5 Elastic recovery of elastomeric yarns

Table 4 presents the experimental results of elastic recovery for certain samples characterized by relatively high breaking elongation, which serve as typical representatives.

Average elastic recovery (%) at various elongations (%) for several elastomeric yarns

| Elongation (%) | PEE1 | PEE2 | PEE1/COT 80/20 | PEE2/PET 50/50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 99.5 | 99.0 | 98.73 | 98.73 |

| 5 | 98.92 | 98.04 | 97.32 | 98.8 |

| 10 | 99.04 | 96.01 | 96.01 | 97.5 |

| 15 | 98.88 | 94.22 | 95.47 | |

| 20 | 98.88 | 93.13 | 94.38 |

4 Conclusion

The PEE raw material, characterized by a hard segment weight ratio of approximately 80%, is deemed suitable for the production of elastomeric staple fibers when blended with PET in a 50/50 weight ratio. These fibers can subsequently be processed into either homogeneous or blended elastomeric yarns. This study offers an in-depth examination of the ring spinning technique used in the production of elastomeric yarns. The emphasis was placed on the blending method of elastomeric staple fibers with cotton or PET staple fibers to create the elastomeric yarn. The impact of blending on the properties of the elastomeric yarns was analyzed in relation to the blending ratio. Systematic experiments were conducted to present the relationship between yarn properties, such as tenacity, breaking elongation, and modulus, and the yarn composition. Both homogeneous and blended elastomeric yarns exhibit an elastic recovery exceeding 90% when subjected to stretching rates between 10 and 15%. This innovative elastomeric yarn is anticipated to lead to the development of new stretchy fabrics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Liang Geng (Chengdu Textile College) for his help in observations of elastomeric yarns by electron microscope.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. MBH and YC designed the experiments (supporting) and carried them out. XL and MBH fabricated and characterized the elastomeric yarn. RL and HB fabricated and characterized the elastomeric poly(ether-ester) staple fiber. MBH and BKM prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. ZD and DW designed the experiments (lead).

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Chen, Y., Haile, M. B., Liu, X., Li, R., Wu, D. (2023). Fabrication and properties of elastomeric yarn from poly(ether ester) staple fiber by ring spinning. Trends in Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology, 8(1), 911–913.10.31031/TTEFT.2023.08.000676Search in Google Scholar

[2] Postrel, V. (2020). The fabric of civilization: How textiles made the world. (p. 217). Basic Books, New York.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gries, T., Veit, D., Wulfhorst, B. (2015). Textile technology: an introduction. (p. 109). Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH, Munich.10.1007/978-1-56990-566-1Search in Google Scholar

[4] Morton, W., Hearle, W. S. (2008). Physical properties of textile fibers. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge.10.1533/9781845694425Search in Google Scholar

[5] Varma, D. S., Maheswari, A., Gupta N., Varma, I. K. (1980). Poly(ester ether) fibers. Die Angewandte Makromolekulare Chemie, 90(1), 23–36.10.1002/apmc.1980.050900103Search in Google Scholar

[6] Gogeva, T., Fakirov, S., Mishinev, J., Sarkisova, L. (1990). Poly(ether ester) fibres. Acta Polymerica, 41(1), 31–36.10.1002/actp.1990.010410108Search in Google Scholar

[7] Haile, M. B., Liu, X., Li, R., Yang, S., Du, Z., Wu, D. (2021). Fabrication and basic properties of elastomeric staple fiber based on poly(butylene terephthalate)-block-(tetramethylene oxide) by melt spinning. Fibre Chemistry, 52(6), 400–404.10.1007/s10692-021-10220-2Search in Google Scholar

[8] Chen, Y., Du, M., Asmare, F. W., Liu, X., Shi, T., Zhang, K., et al. (2023). The conception and measurements of “average stress-strain curves” for fibrous materials. Trends in Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology, 8(4), 988–993.10.31031/TTEFT.2023.08.000695Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sinclair, R. (2015). Understanding textile fibres and their properties: what is a textile fibre? In Textiles and fashion. (pp. 3–27). Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge.10.1016/B978-1-84569-931-4.00001-5Search in Google Scholar

[10] Schwartz, P. (2019). Structure and mechanics of textile fibre assemblies. Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chu, C., Zhong, Y. (1998). Discussions on visco-elastic mechanical properties of yarns. Shanghai Textile Science and Technology, 26(5), 18–20.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Coplan, M. J. (1960). A possible application of organic fibers in high temperature environment. Wright Air Development Division, Air Research and Development Command.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Hearle, J., Grosberg, P., Backer, S. (1969). Structural mechanics of fibers, yarns, and fabrics. (pp. 16–21). Wiley-Interscience, New York.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Lawrence, C. A. (2003). Fundamentals of spun yarn technology. (p. 552). CRC Press, London, New York.10.1201/9780203009581Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ye, G., Chen, Q. (1987). Calculation and measurement of winding tension for yarn at ring spinning. Journal of China Textile University, 15(4), 59–65.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lord, P. R. (2003). Handbook of yarn production technology. (pp. 427–452). Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge.10.1201/9780203489710Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method