Abstract

Fur is the soft, thick hair that covers the skin of certain animals, and is often used in clothing, while the cut pile loop (faux fur) knitted fabrics are produced to simulate the natural fur. The production process of these fabrics was explained in detail, and the effects of fabric construction parameters (ground loop length (L), ground count (G), and pile yarn count (F)) on the geometrical, thermal, and abrasion resistance properties were investigated. The faux fur knitted fabric samples were produced at three levels of ground loop length (3.3, 3.5, and 3.7 mm), two different ground count (100 and 150 den), and three levels of pile yarn’s count (200, 300, and 400 den). The Tien Yang circular knitting machine settings, feeders, cams and yarns’ arrangements were illustrated. It can be concluded from the evaluated results that the fabric construction parameters had significant effects on the faux fur fabric’s properties. By increasing the pile yarn count from 200 to 400 den; the fabric weight, thickness, thermal resistance, and weight loss due to abrasion were increased approximately 75, 78, 56, and 61%, respectively.

1 Introduction

Faux fur is considered as a friendly alternative to real furs and its price is also much lower than natural furs. Faux fur was introduced in the fashion industry in 1929. It is produced from synthetic fibers like acrylic, polyester, and modacrylic fibers by using weaving or knitting technology [1]. Faux fur offers several advantages, including being animal-friendly, widely adopted in the fashion industry as a stylish and ethical alternative to real fur [2]. Most studies related to fur apparels were about the consumption behavior or growth strategies based on economic reports instead of the apparel design itself [2].

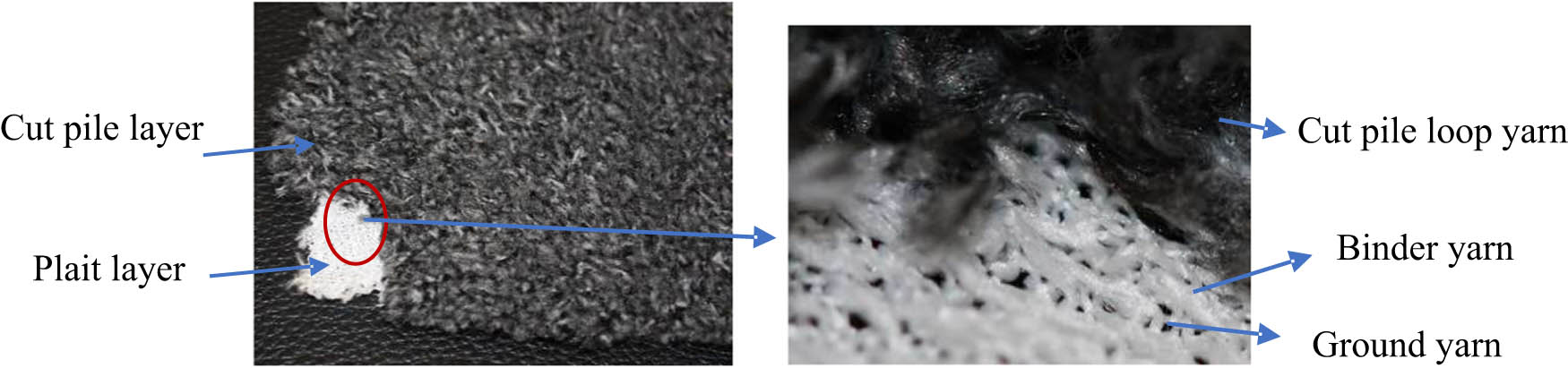

The main aim of the faux fur knitted fabric (FFKF) production is to give them all the properties of natural fur “naturalization of fur knitted fabrics” [3]. Knitted fur fabrics have a composite fibrous structure made of two layers, namely, plait layer and pile layer [4]. During the production process, three sets of yarns are used during its production, namely, the ground yarn, the binder yarn, and the pile yarn. The fur yarn in this process is perpendicular to the fabric’s surface. The ground and binder yarns compose the plait layer, and the pile yarn composes the pile layer, as shown in Figure 1.

3D structure of fur knitted fabric.

Therefore, each set of yarns is characterized by its special properties, which give the fur fabric the advantage in specific end-use, as these fabrics are used in winter clothes, which are characterized by providing warmth to the wearers and permitting the transfer of water vapor to feel comfort. The pile knitting structures have different functional and mechanical properties [5,6].

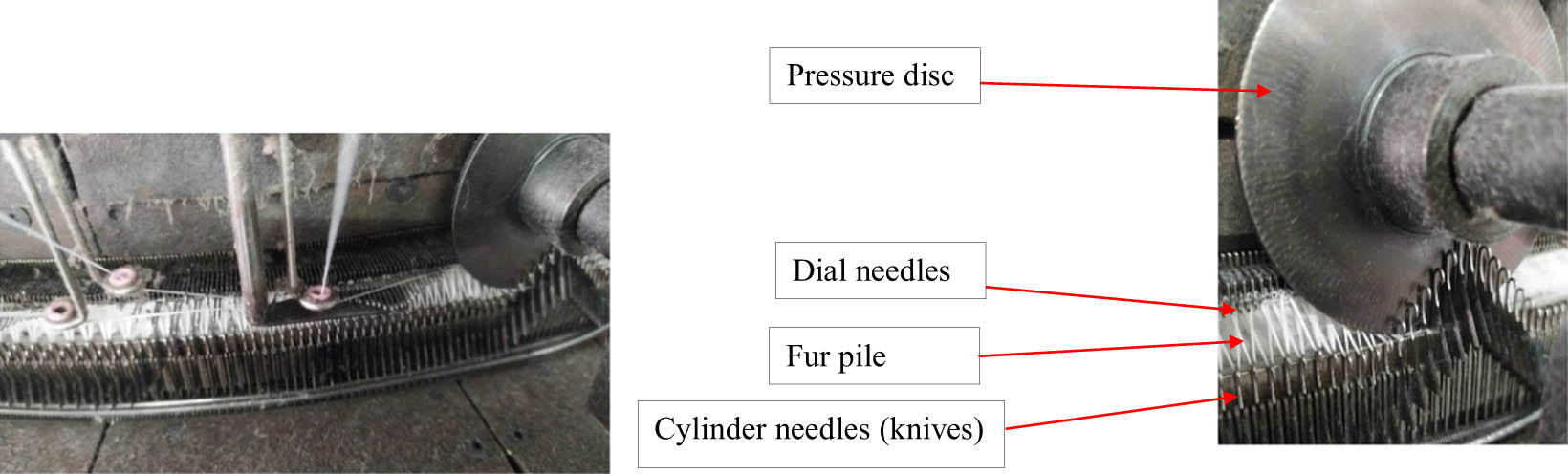

In industry and market, there is the plush fabric produced on a single jersey circular knitting machine with a special sinker, by which loops are made on the vertical surface of the fabric where the sinker height defines the pile height. These fabrics are used with loop pile or cut pile, which are prepared on shearing machine rather than the knitting machine. Meanwhile, the FFKF is produced on a derived double circular knitting machine (cylinder and dial) which has several pressure discs that ensure the pile cutting process during the fabric production, as illustrated in Figure 2. The distance between the cylinder and the dial in this machine is differently opened rather than the regular double machines, in order to enable the production of high pile height, and also allow for greater opportunities for the use of cut pile loop yarns of different count. The FFKF is characterized by high thickness compared to the plush knitted fabrics.

The process of opening (cutting) the fur stitches.

Huong [7] studied the effect of pile loop length on dimensional changes after three washing cycles of the cut pile knitted fabric. Four single pile fabric samples were produced with four different values of pile loop length 7.58, 7.88, 8.03, and 8.37 mm and with the same ground loop length, pile yarn count, and ground yarn count. It was concluded that the fabric thickness decreased with the increase in pile loop length with the first three loop length values, and then it reached the maximum thickness of 2.45 mm with the pile loop length of 8.37 mm. The fabric thickness slightly increased after three washing cycles [7].

Abd El-Hady and Abd El-Baky [5] studied the effect of knit structures (Fleece and plush weft knitted fabric) on bursting strength, air permeability, absorption, and thermal insulation properties. It was concluded that thermal resistance depends on raw material, fiber quality, type of knitting structure, and pile height, and the structural parameters of knitted fabric had a significant effect on the air permeability [5].

Uyanik [8] investigated the effect of structural parameters on loop pile and FFKF properties. It was found that the higher pile height increased the fabric weight and thickness, and improved the abrasion resistance of the fabrics. The thicker pile yarn decreased the air permeability of the fabrics. Pile loop knit fabrics had higher abrasion resistance and lower air permeability compared to FFKF [8].

Uyanik et al. [9] investigated the effect of structural parameters on the dimensional stability and spirality of the FFKF. Results summarized that the higher pile height increased fabric shrinkage, decreased spirality in pile loop fabrics, and increased spirality in FFKF. The FFKF had better dimensional stability and less spirality than pile loop fabrics [9].

Patyk and Korliński [10] investigated the mechanical parameters of fur fabrics such as permanent deformation, squeezing susceptibility, and elasticity of natural fur and man-made fur knitted fabric based on a new layer model for compression of furs. Six outer fur materials (three natural and three knitted) were used. The fabric thickness was around 10 mm and fabric weight ranged between 200 and 1,200 g/m2. The results showed that the minimum apparent densities of fabric samples had the best elasticity and permanent deformation; moreover, the fabric weight of natural furs was 2–3 times higher than the FFKF.

Korycki and Wiezowska [3] investigated the relation between construction parameters of FFKF and the heat transfer, resistance of heat conduction, and heat transmission. Eleven single fur knitted fabric was selected, the fabric thickness ranged between 4.05 and 18.60 mm, and the surface mass ranged between 199.7 and 708.5 g/m2. The results concluded that the heat conduction coefficient decreased with the increase in the fabric thickness and weight, and the heat conduction resistance increased with the fabric thickness and weight increase [3].

El-hady et al. [11] studied the effect of raw materials on the quality and functional performance properties of produced cut terry/velour and fur fabrics, which are used in car seats. They illustrated that the type of materials, stitch length, pile length, and needle arrangement played important roles in the air permeability, abrasion resistance, and bursting strength [11].

The model of heat transfer within the FFKF was presented using a second-order differential equation and a set of boundary and initial conditions of the plaited and pile layers [4]. Artificial neural network, fuzzy logic, and multiple linear regression models were applied to predict the air permeability of pile knitted fabric. So, the pile knitted structure with different weights was produced at four counts of filament fineness. The results showed that the artificial neural network model had superior performance compared to the fuzzy logic and multiple linear regression models [6]. After the survey of previous research, there is limited information regarding the production process and properties of the FFKF. So, the main aims of the proposed work are to:

Explain in detail the production process of the FFKF.

2 Materials and methods

Eighteen FFKF samples were produced from 100% polyester fibers for ground, binder, and pile yarns with same pile loop length, same binder loop length, and three levels of ground loop length. The number of fibers in ground yarn cross-section was 144 for two yarn counts 100 and 150 den. The binder yarn had the same count and number of fibers in cross-section of the ground yarn. The number of fibers in pile yarn were 288 with three counts 200, 300, and 400 den as shown in Table 1, on Tien Yang circular knitting machine with gauge 22, diameter 30 inch, 50 feeders, and 2,064 needles, Model 2004.

Construction parameters of faux fur knitted samples

| Sample No. | Ground Count 144 fibers (den) | Pile yarn Count 288 fibers (den) | Ground loop length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 200 | 3.3 |

| 2 | 100 | 200 | 3.5 |

| 3 | 100 | 200 | 3.7 |

| 4 | 100 | 300 | 3.3 |

| 5 | 100 | 300 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 100 | 300 | 3.7 |

| 7 | 100 | 400 | 3.3 |

| 8 | 100 | 400 | 3.5 |

| 9 | 100 | 400 | 3.7 |

| 10 | 150 | 200 | 3.3 |

| 11 | 150 | 200 | 3.5 |

| 12 | 150 | 200 | 3.7 |

| 13 | 150 | 300 | 3.3 |

| 14 | 150 | 300 | 3.5 |

| 15 | 150 | 300 | 3.7 |

| 16 | 150 | 400 | 3.3 |

| 17 | 150 | 400 | 3.5 |

| 18 | 150 | 400 | 3.7 |

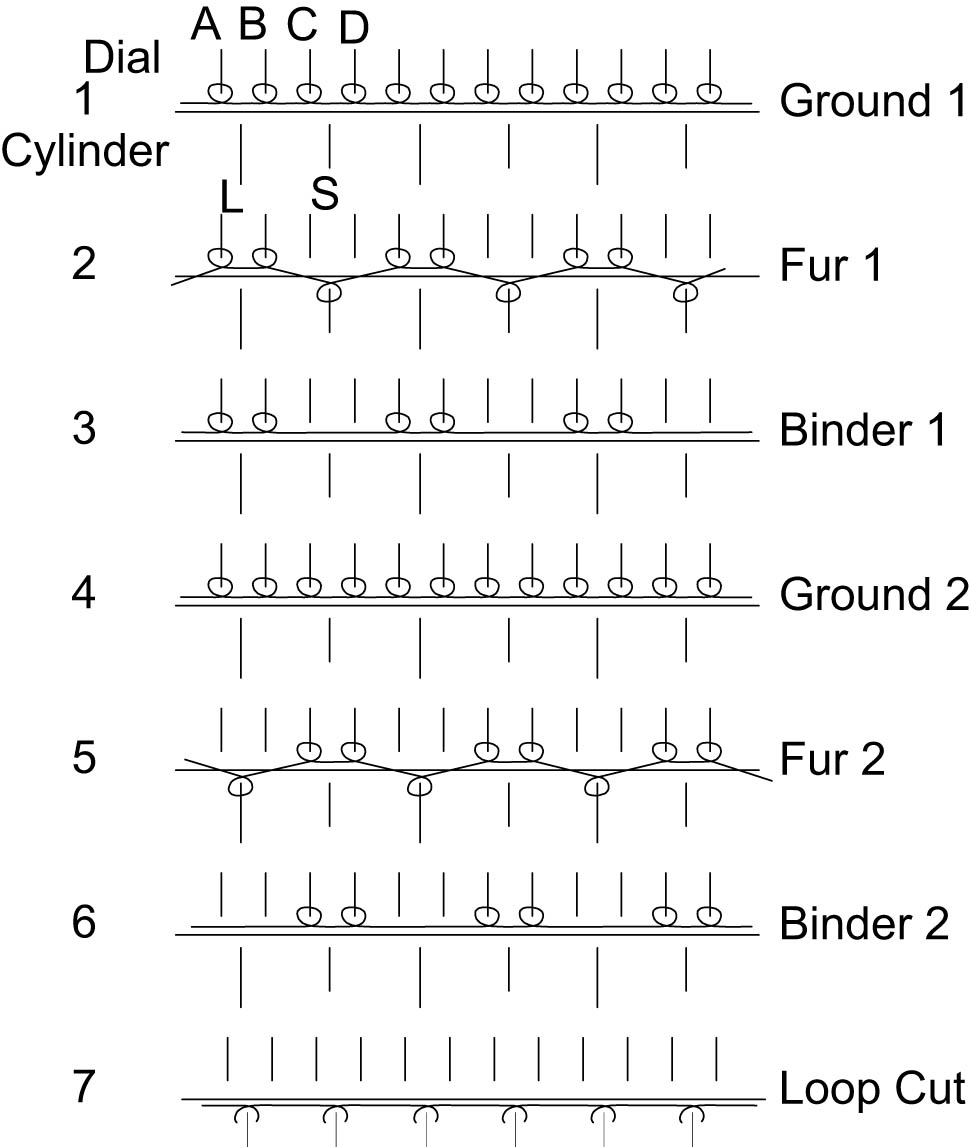

2.1 Production process of FFKF

2.1.1 Arrangement of feeders and yarns

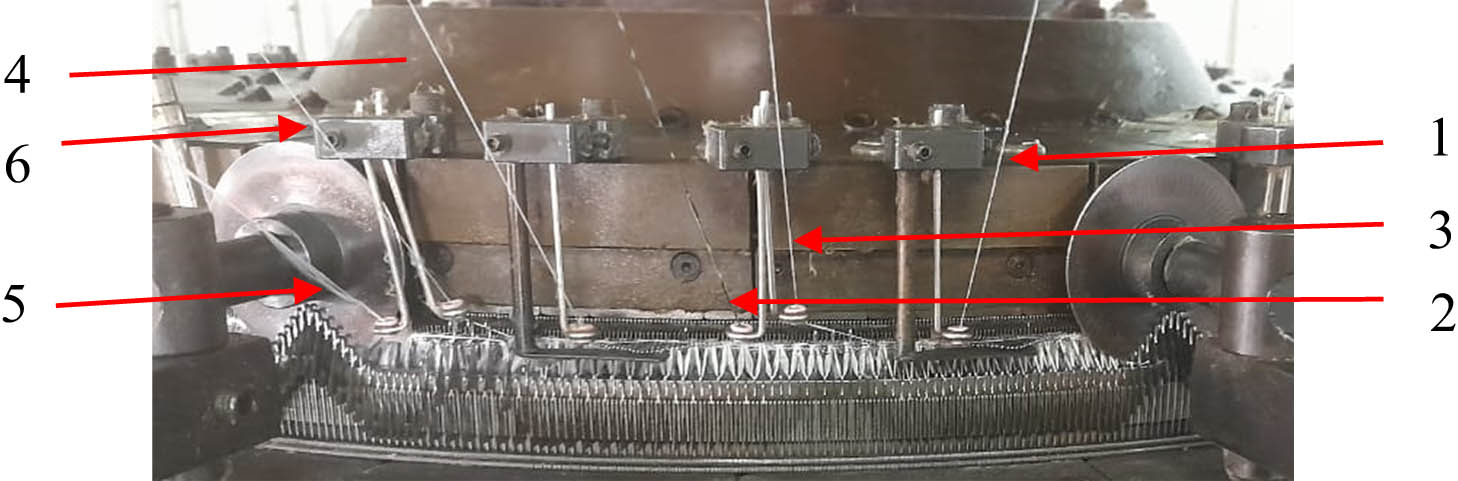

To produce FFKF, the machine is fed with six yarns (two ground, two binder, and two pile yarns) to compose a unit cell of the cut pile loop structure as follows:

The first yarn is the ground yarn 1, which is fed to all the dial needles to make the plain knitting stitch that appears on the back of the fabric (plait layer), as shown in Figure 3.

The second yarn is the pile yarn 1 and it usually has a different count and properties than the ground yarn. It is fed to short needles of the cylinder and dial needles A and B, as shown in Figure 4.

The third yarn is the binder yarn 1. It is fed to the dial needles A and B, and it is behind the short cylinder needles during their lifting.

The fourth yarn is the ground yarn 2, and its feeding is the same as the ground yarn 1.

The fifth yarn is the pile yarn 2. It is fed to long needles of the cylinder and the dial needles C and D, and it is behind the cylinder needles during their lifting, as shown in Figure 3.

The sixth yarn is the binder yarn 2, and it is fed to the dial needles C and D.

Feeders and yarn arrangement, 1 and 4: ground yarn; 2 and 5: cut pile loop yarn; 3 and 6: binder yarn.

Cylinder and dial needles of different butts.

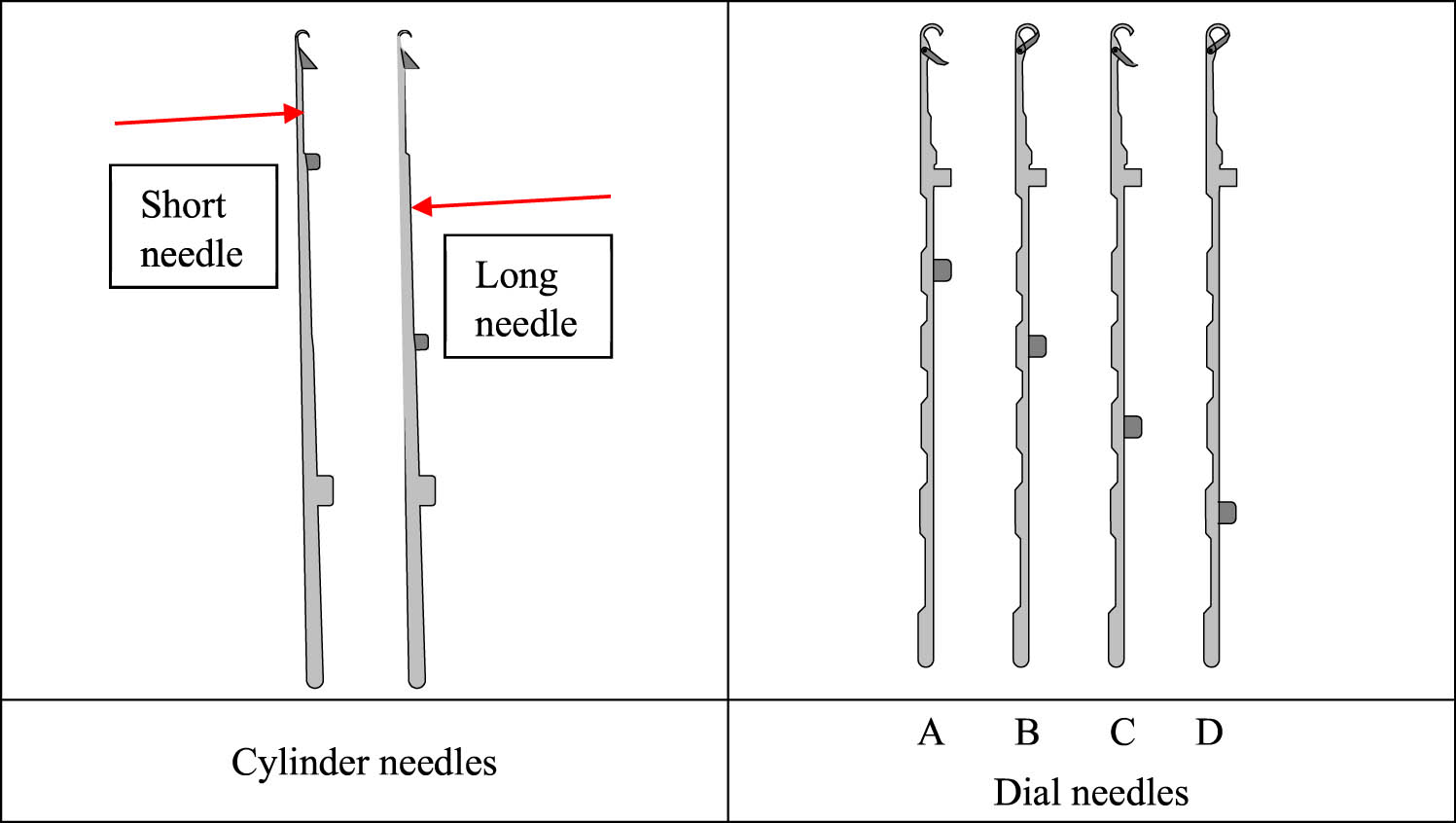

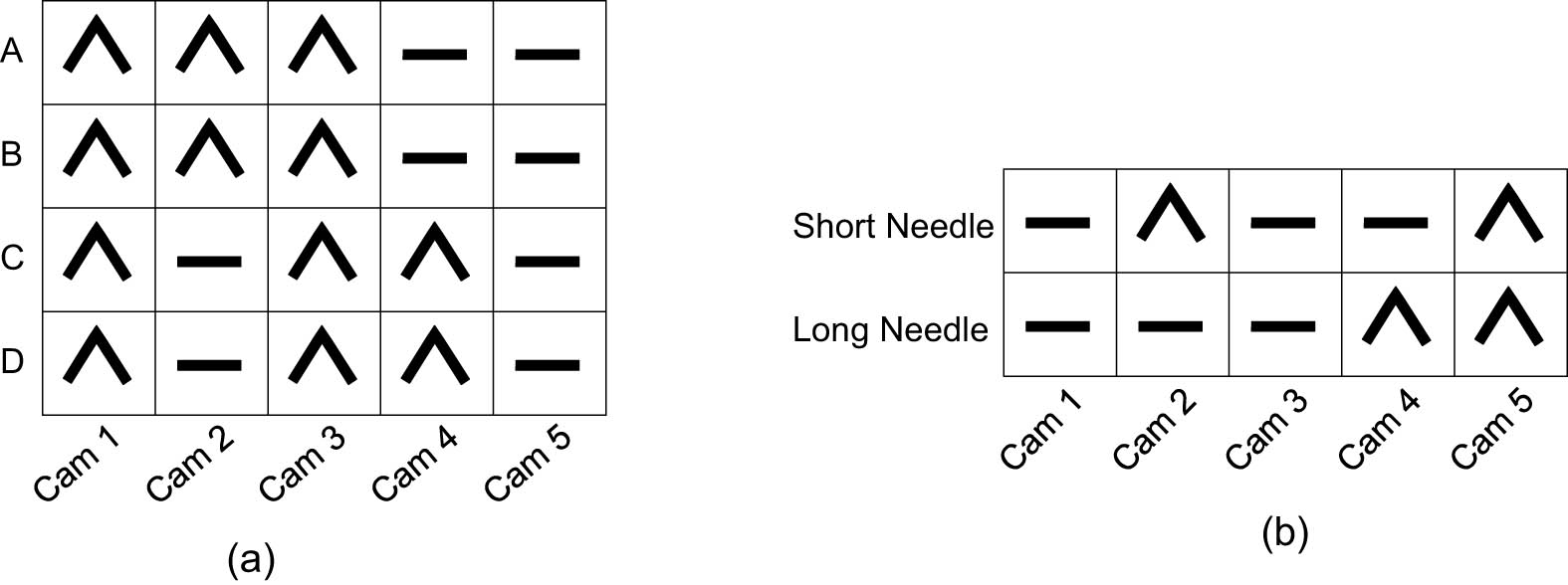

2.1.2 Needles’ arrangement

For the dial, the latch needles are used, whereas for the cylinder, special hook needles without a latch and with an additional part are used to cut the pile and form fur, as demonstrated in Figure 4. These types of needles are commonly known as knives. The dial needles were investigated, and they are arranged according to the butts, respectively, as A, B, C, and D. While the cylinder needles (knives) are short and long needles and are arranged inside the cylinder grooves (one by one) so that one groove contains a needle and the other is empty.

Dial cams (a) and cylinder cams (b) arrangement.

Notation of FFKF.

2.1.3 Cam arrangement

The cam 2 of cylinder’s cams works only with short needles to feed it with the pile yarn. At the same moment the dial’s cam 2 works with A and B needles to feed them with the fur and binder yarns.

The dial’s cam 3 and cylinder’s cam 3 have the same movement of cam 1 for both dial and cylinder, respectively.

As for the cylinder’s cam 5, it is a knit stitch cam that raises all the cylinder needles to perform the clearance process and cut the pile loop. The pressure disc is installed at this cam to press on all the stitches while the cylinder’s needles rise to ensure the process of cutting all stitches correctly.

The dial’s cam 5 is a miss stitch cam, so that the dial needles do not rise and collide with the pressure disc.

The FFKF structure and loop notation diagram is illustrated in Figure 6, to enhance the clarity of fabric structure.

Thermal conductivity, resistance, absorptivity, and fabric thickness were measured by Alambeta instrument [14] according to the standard ISO 8301 [15]. Fabric water vapor resistance was tested by Permetest instrument, the so-called skin model that simulates dry and wet human skin in terms of its thermal feeling [16,17] according to ISO 11092 [18]. Fabric linear density (weight per unit area – gram per square meter [GSM], g/m2) was measured according to the standard ISO 3801 and the weight loss percent due to abrasion was measured on the Martindale abrasion tester, according to AATCC TM 93-2011 [19,20].

All the experimental results were evaluated using the analysis of variance statistical method, at 95% confidence level to optimize the FFKF properties. According to the results of variance analysis given in Table 2, the pile yarn count (F) had a significant effect on all fur fabric properties except for thermal absorptivity, the ground yarn count (G) was a significant factor affecting all fur fabric properties except water vapor resistance, and ground loop length was a significant factor affecting all FFKF properties except thermal resistance.

Statistical significance of processing parameters on fabric properties

| Knitted fabric properties | Fabric weight | Fabric thickness | Thermal conductivity | Thermal absorptivity | Thermal resistance | Relative water vapor permeability | Weight loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground yarn count (G) | 0.0 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.0 | 0.040 | 0.242 | 0.0 |

| Pile yarn count (F) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.408 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ground loop length (L) | 0.0 | 0.028 | 0.004 | 0.0 | 0.151 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| R squared | 0.983 | 0.992 | 0.980 | 0.889 | 0.989 | 0.996 | 0.897 |

3 Results and discussion

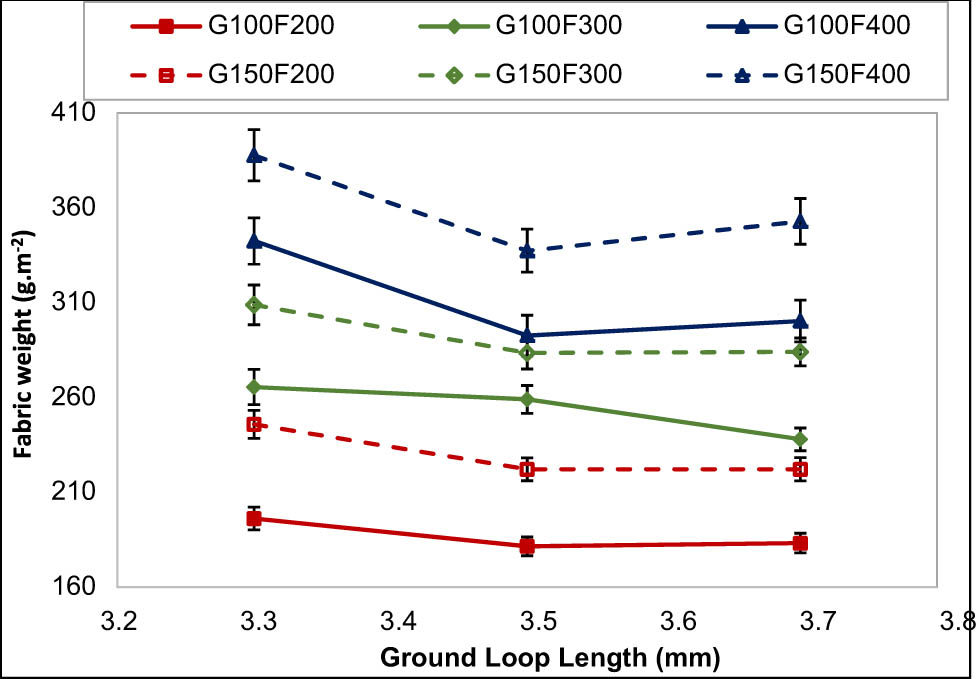

3.1 Effect of fabric construction parameters on fabric weight

Figure 7 demonstrates the effect of ground yarn’s loop length and its linear density on the weight of fur knitted fabrics at three different counts of pile yarns. The figure illustrates that increasing L from 3.3 to 3.7 mm decreased the fabric weight (GSM) of fur fabrics by a maximum of 12.5% for the samples produced with ground and pile yarns 100 and 400 denier, respectively, that may be relay to the fact that with the increase in stitch length, the density of stitches per cm2 decreases, which reduces the GSM. By increasing G from 100 to 150 den, the GSM increased up to 25% at F 200 den and L 3.3 mm. With increasing F from 200 to 300 den, and from 300 to 400 den, the fabric weight increases 35 and 29%, respectively, at G 100 den and L 3.3 mm, because the two pile yarns had the same number of fibers in yarn cross-section (288 fibers), i.e., the diameter of the fibers increases with the increase in yarn den, that increased the GSM. The statistical analysis showed that the pile yarn count, ground yarn count, and ground loop length had a significant effect on the fabric weight, as listed in Table 2.

Effect of ground yarn count (G), loop length (L), and cut pile loop yarn count (F) on the fabric weight.

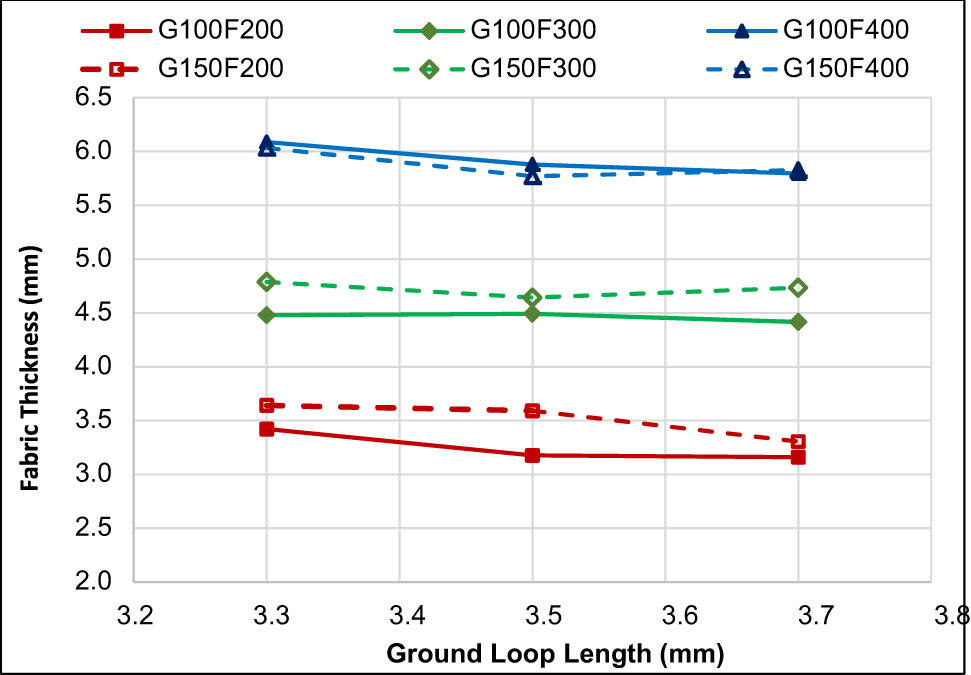

3.2 Fabric thickness

The FFKF thickness decreased with increasing L from 3.3 to 3.7 mm by 7.5% at G 100 den and F 200 den. Also, by increasing G from 100 to 150 den, the knitted fabric thickness increased by approximately 13% at F 200 den and L 3.5 mm. The knitted fabric thickness increased by 78% when F increased from 200 to 400 den at G 100 den and L 3.3 mm, because the yarn diameter increases with the increase in pile yarn count; therefore, the fiber bending rigidity and fabric thickness were increased (Figure 8).

Effect of ground loop length (L), ground yarn count (G), and pile yarn count (F) on the fabric thickness.

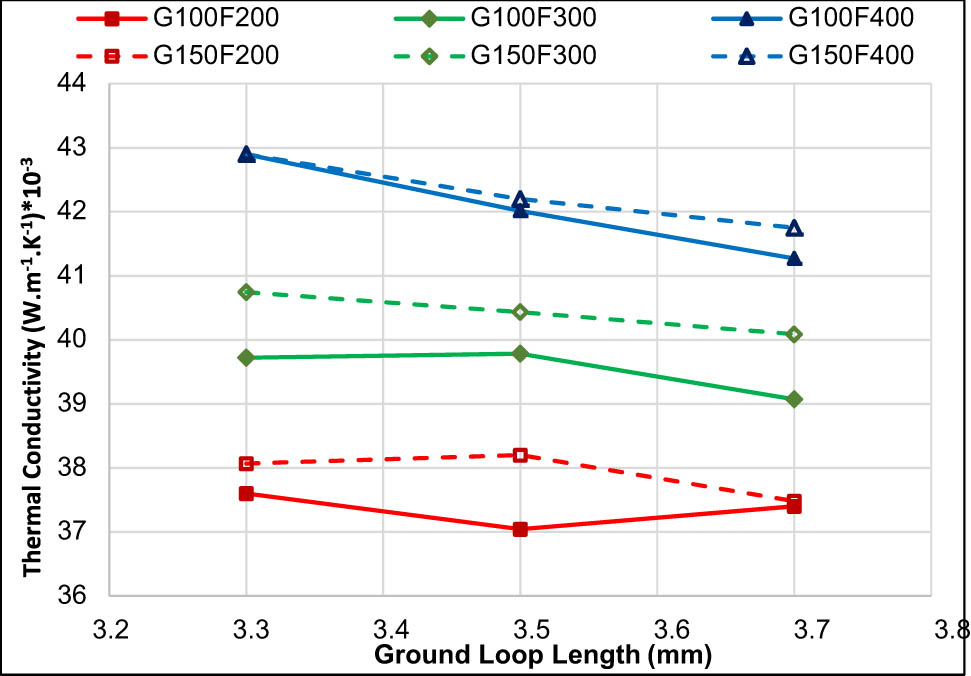

3.3 Effect of fabric construction parameters on thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity coefficient (λ) presents “the amount of heat which passes from 1 m2 area of material through the distance 1 m within 1 s and the temperature difference 1 K” [21], see equation (1) [22]. It is the fabric ability to transfer heat from anybody to environment and vice versa depending on the temperature difference between the body and environment [23].

where

The thermal conductivity slightly increased with increasing G by 3% at F 200 den and L 3.5 mm, as shown in Figure 9. Also, it increased when F increased from 200 to 400 den by up to 14% at G 100 den and L 3.3 mm, which might be due to the increase in fiber diameter with the counts increasing at the same number of fibers in yarn cross-section. While it decreased slightly with L increasing from 3.3 to 3.7 mm by 4% at G 100 den and F 400 den due to the decrease in number of fibers per unit area [24]. These results recommend that adjusting fabric construction parameters can impact thermal conductivity, which could be important for applications where temperature regulation is crucial [21,25].

Effect of ground loop length (L), ground count (G), and pile yarn count (F) on the fabric thermal conductivity.

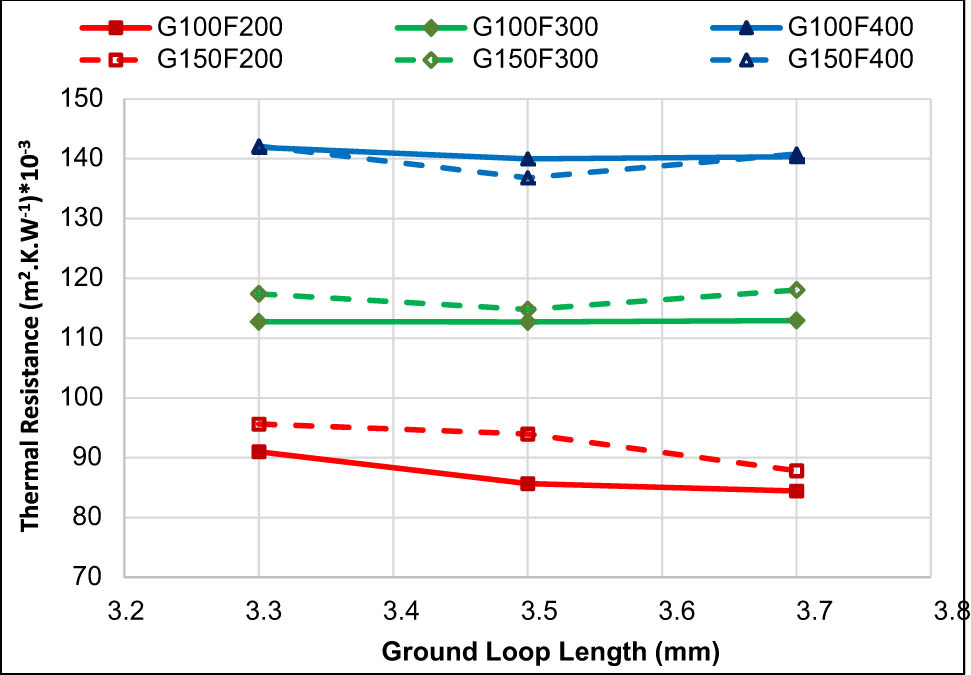

3.4 Thermal resistance

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of ground loop length, count, and pile yarns’ fineness on the thermal resistance, and the results in Figure 10 and Table 2 concluded that the effect of L is not significant, while G has a slightly weak positive correlation, whereas the effect of F on the thermal resistance is significant. By increasing F from 200 to 400 den, the thermal resistance increased 56% at L 3.3 mm, due to the increase in fabric thickness (78%), which matches with the heat transfer through conduction theory [26,27], as in equation (2)

where R is the thermal resistance (K m2 W−1), and h is the fabric thickness (mm).

Effect of ground loop length (L), ground (G), and pile yarn count (F) on the fabric thermal resistance.

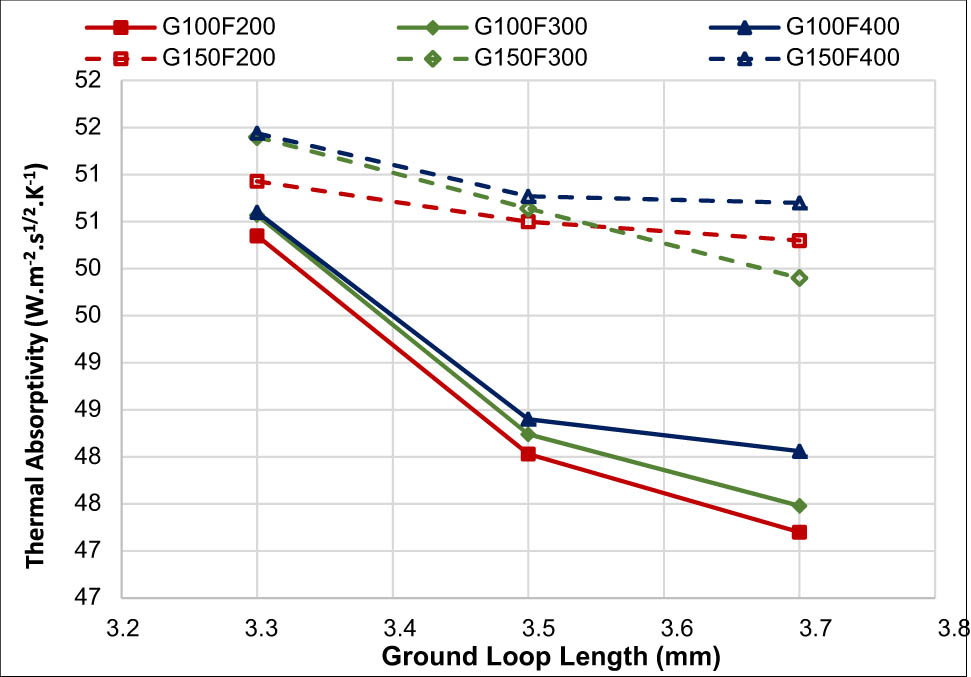

3.5 Thermal absorptivity

Thermal absorptivity is “the objective measurement of the warm cool feeling of a fabric” [25,28], which could be calculated by equation (3)

where b is the thermal absorptivity (W s1/2 m−2 K−1),

The thermal absorptivity decreased with L increasing while thermal absorptivity increased with G increasing, as shown in Figure 11. This may be due to an increase in the fabric density with the increase in G as shown in Table 3. The statistical analysis showed that L and G had significant effects on the thermal absorptivity, and F had a nonsignificant effect [29,30].

Effect of ground loop length (L), ground (G), and pile yarn count (F) on the fabric thermal absorptivity.

Fabric density of fur knitted samples

| Fabric density (kg/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ground yarn count 144 fibers | Pile yarn count 288 fibers | Ground loop length (mm) | ||

| 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.7 | ||

| 100 | 200 | 57.34 | 57.13 | 57.97 |

| 300 | 59.28 | 57.65 | 53.89 | |

| 400 | 56.27 | 49.78 | 51.83 | |

| 150 | 200 | 67.52 | 61.86 | 67.25 |

| 300 | 64.51 | 61.07 | 59.99 | |

| 400 | 64.25 | 58.47 | 60.55 | |

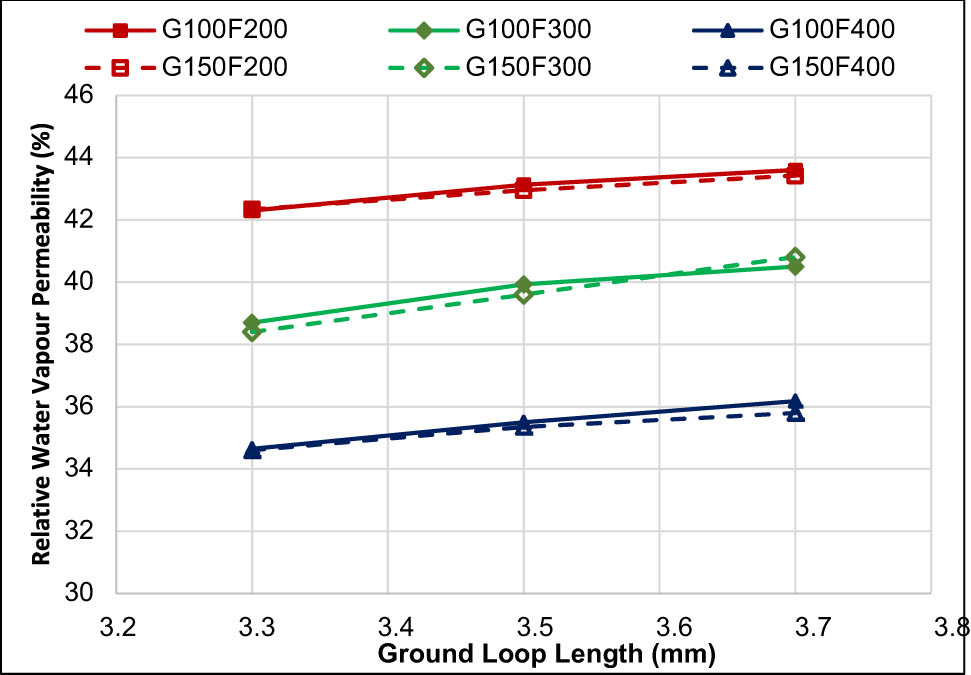

3.6 Relative water vapor permeability (RWVP)

The RWVP is determined according to equation (4):

where

It could be summarized from Figure 12 and Table 2 that the effect of G is nonsignificant and distinguished. While, the effect of F and L is significant on the RWVP of the faux fur fabric, where by increasing F from 200 to 400 den, the fur fabric RWVP decreased by up to 18% at L 3.3 mm and G 100 den, because an increase in F means an increase in the yarn diameter; therefore, the pore size between yarns decreased and RWVP decreased. Generally, the RWVP increased when the L increased due to an increase in the pore size [31].

Effect of ground loop length (L), ground (G), and pile yarn count (F) on the RWVP.

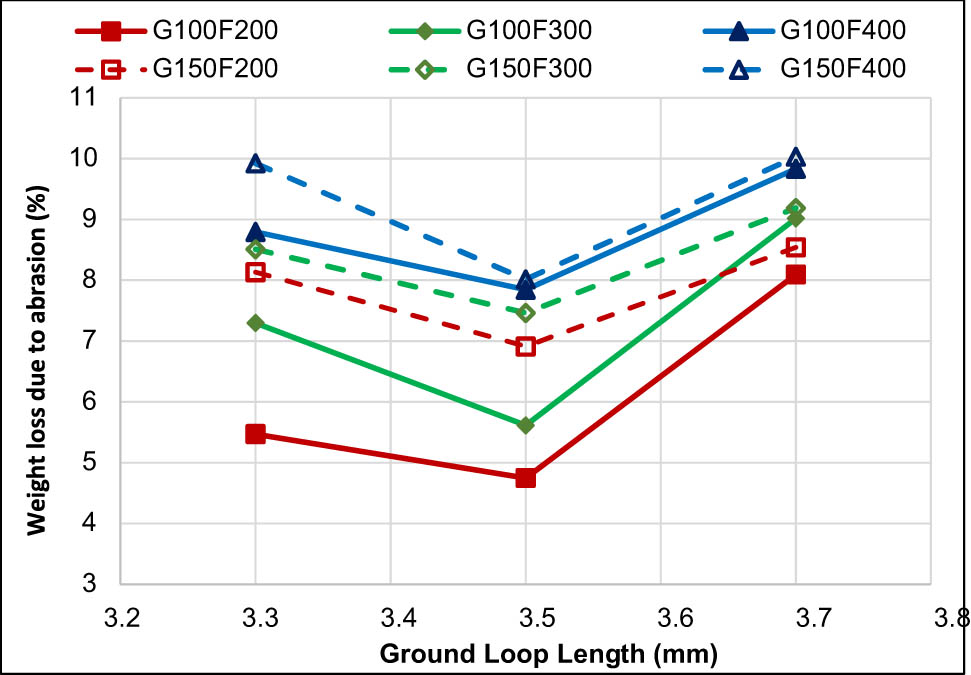

3.7 Weight loss due to abrasion

Generally, the weight loss due to abrasion decreased with increasing L from 3.3 to 3.5 mm, and then it increased with increasing L from 3.5 to 3.7 mm, as shown in Figure 13. The weight loss increased with increasing F from 200 to 400 den by 61% at L 3.3 mm and G 100 den, and with increasing G from 100 to 150 den by 47% at L 3.3 mm and F 200 den. This may be due to an increase in the fabric weight and yarn thickness. G, F, and L had a significant effect on the weight loss due to abrasion [8,32,33], as shown in Table 2.

Effect of ground count (G), loop length (L), and pile yarn count (F) on weight loss due to abrasion.

4 Conclusion

This study highlights the crucial role of fabric construction parameters in determining the properties of FFKFs. By optimizing these parameters, manufacturers can produce high-quality faux fur fabrics that meet specific performance and aesthetic requirements, ultimately enhancing their applications in various industries. The 18 FFKF samples were produced on Tien Yang circular knitting machine, and the effect of fabric construction parameters, namely, ground loop length, ground yarn count, and pile yarn count on the geometrical, thermal, and mechanical properties were investigated. The results concluded that:

The fabric weight and thickness increased with increasing ground and pile yarn counts.

Thermal conductivity and resistance increased with the increase in pile yarn count.

Thermal absorptivity decreased with the increase in ground loop length, and increased with increasing ground yarn count.

RWVP decreased with the increase in pile yarn count, and increased with the increase in ground loop length.

Weight loss due to abrasion increased with the increase in ground and pile yarn count.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and the European Union-European Structural and Investment Funds in the Frames of Operational Program Research, Development and Education-Project Hybrid Materials for Hierarchical Structures (HyHi, Reg. No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000843).

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and the European Union-European Structural and Investment Funds in the Frames of Operational Program Research, Development and Education-Project Hybrid Materials for Hierarchical Structures [HyHi, Reg. No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000843].

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Abdelmonem Fouda and Abdelhamid Aboalasaad designed the experiments and Amany Khalil carried them out. Brigita Kolčavová Sirková revised the final manuscript's draft especially the experimental work. Abdelhamid Aboalasaad and Amany Khalil collected the literature review then prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

-

Data availability statement: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

References

[1] Bijleveld, M. (2013). Natural mink fur and faux fur products, an environmental comparison, Delft, Netherlands.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kim, H. (2014). Development of fashion faux fur using 3-dimensional embroidery technique for Russian, Chinese premium markets. Archives of Design Research, 111(3), 89–111. 10.15187/adr.2014.08.111.3.89.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Korycki, R., Wiezowska, A. (2008). Relation between basic structural parameters of knitted fur fabrics and their heat transmission resistance. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 16(3), 84–89.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Korycki, R., Wiezowska, A. (2011). Modelling of the temperature field within knitted fur fabrics. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 84(1), 55–59.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Abd El-Hady, R. A., Abd El-Baky, R. A. A. (2015). The influence of pile weft knitted structures on the functional properties of winter outerwear fabrics. Journal of American Science, 11(9), 101–108.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Haroglu, D. (2023). Modeling the air permeability of pile loop knit fabrics using fuzzy logic and artificial neural network. Journal of The Textile Institute, 114(2), 265–272. 10.1080/00405000.2022.2028361.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Huong, C. D. (2022). Investigation of the influence of pile looplength on the dimension change of the pile knitted fabric after washing cycles abstract. Journal of Science & Technology, 3, 62–66.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Uyanik, S. (2016). Investigation of the effect of pile height and yarn linear density on the performance properties of pile loop and cut-pile loop knit fabrics. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 24(1), 95–100. 10.5604/12303666.1172092.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Uyanik, S., Zervent Unal, B., Çelik, N. (2015). Examining of the effect of fabric structural parameters on dimensional and aesthetic properties in pile loop and cut-pile loop knit fabrics. International Journal of Science and Research, 4(9), 943–948.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Patyk, B., Korliński, W. (2002). Preliminary analysis of the pile properties of fur knitting’s during the process of compression. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 10(4), 49–51.Search in Google Scholar

[11] El-hady, R. A. M. A., El-baky, R. A. A. A., Ali, S. A. S. (2018). Enhancing the functional performance properties of pile weft knitted fabrics used in car interiors. Journal of Engineering Research and Application, 8(9), 70–81. 10.9790/9622-0809047081.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Jhanji, Y., Gupta, D., Kothari, V. K. (2024). Role of fibre, yarn and fabric variables in engineering clothing with required thermo-physiological properties. Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research, 49(1), 109–128. 10.56042/ijftr.v49i1.9536.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Abdel-Rehim, Z. S., Saad, M. M., El-Shakankery, M., Hanafy, I. (2006). Textile fabrics as thermal insulators. AUTEX Research Journal, 6(3), 148–161. 10.1515/aut-2006-060305.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Hes, L., Dolezal, I. (1989). New method thermal and equipment for measuring properties of textiles. Journal of the Textile Machinery Society of Japan, 42, 71–75.10.4188/transjtmsj.42.8_T124Search in Google Scholar

[15] Insulation, T. (1991). Determination of steady-state thermal resistance and related properties. Heat flow meter apparatus, International Organization for Standardization, Latvian Standard, Riga, Latvia.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Hes, L., Dolezal, I. (2003). A new computer-controlled skin model for fast determination of water vapour and thermal resistance of fabrics. In 7th Asian Textile Conference. New Delhi.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hes, L. (2008). Non-destructive determination of comfort parameters during marketing of functional garments and clothing. Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research, 33(3), 239–245.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Gibson, P., Auerbach, M., Giblo, J., Teal, W., & Endrusick, T. (1994). Interlaboratory evaluation of a new sweating guarded hot plate test method (ISO 11092). Journal of Thermal Insulation and Building Envelopes, 18(2), 182–200.10.1177/109719639401800207Search in Google Scholar

[19] Eryuruk, S. H. (2019). Effect of fabric layers on thermal comfort properties of multilayered thermal protective fabrics. Autex Research Journal, 19(3), 271–278. 10.1515/aut-2018-0051.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Özdil, N., Kayseri, G. Ö., & Mengüç, G. S. (2012). Analysis of abrasion characteristics in textiles. Abrasion resistance of materials, 2, 119–146.10.5772/29784Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chen, Q., Miao, X., Mao, H., Ma, P., Jiang, G. (2016). The comfort properties of two differential-shrinkage polyester warp knitted fabrics. Autex Research Journal, 16(2), 90–99. 10.1515/aut-2015-0034.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Ertekin, G., Oğlakcioğlu, N., Marmarali, A. (2018). Strength and comfort characteristics of cotton/elastane knitted fabrics. Tekstil ve Mühendis, 25(110), 146–153. 10.7216/1300759920182511010.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Pant, S., Jain, R. (2014). Comfort and mechanical properties of cotton and cotton blended knitted Khadi fabrics. Studies on Home and Community Science, 8, 69–74.10.1080/09737189.2014.11885419Search in Google Scholar

[24] Küçük, M., Korkmaz, Y. (2019). Acoustic and thermal properties of polypropylene carpets: Effect of pile length and loop density. Fibers and Polymers, 20(7), 1519–1525. 10.1007/s12221-019-1181-1.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Afzal, A., Ahmad, S., Rasheed, A., Ahmad, F., Iftikhar, F., Nawab, Y. (2017). Influence of fabric parameters on thermal comfort performance of double layer knitted interlock fabrics. Autex Research Journal, 17(1), 20–26. 10.1515/aut-2015-0037.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Alibi, H., Fayala, F., Jemni, A., Zeng, X. (2012). Modeling of thermal conductivity of stretch knitted fabrics using an optimal neural networks system. Journal of Applied Sciences, 12(22), 2283–2294. 10.3923/jas.2012.2283.2294.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zhu, F. L. (2020). Investigating the effective thermal conductivity of moist fibrous fabric based on Parallel-Series model: A consideration of material’s swelling effect. Materials Research Express, 7(4), 045308. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab8541.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Behera, B. K., Hari, P. K. (1994). Fabric quality evaluation by objective measurement. Indian Journal of Fibre and Textile Research, 19, 168–171.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Khalil, A., Fouda, A., Těšinová, P., Eldeeb, A. S. (2021). Comprehensive assessment of the properties of cotton single jersey knitted fabrics produced from different lycra states. AUTEX Research Journal, 21(1), 71–78. 10.2478/aut-2020-0020.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Khalil, A., Těšinová, P., Aboalasaad, A. R. R. (2022). Effect of lycra weight percent and loop length on thermo-physiological properties of elastic single jersey knitted fabric. AUTEX Research Journal, 22(4), 419–426. 10.2478/aut-2021-0030.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Aboalasaad, A. R. R., Skenderi, Z., Brigita, K. S., Khalil, A. A. S. (2019). Analysis of factors affecting thermal comfort properties of woven compression bandages. AUTEX Research Journal, 1, 1–8. 10.2478/aut-2019-0028.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Asanovic, K. A., Ivanovska, A. M., Jankoska, M. Z., Bukhonka, N., Mihailovic, T. V., Kostic, M. M. (2022). Influence of pilling on the quality of flax single jersey knitted fabrics. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 17, 1–13. 10.1177/15589250221091267.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Guo, M., Liu, J., Zhu, B., Gao, W. (2022). Evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of cotton warps under a cyclic load of stretch-abrasion. AUTEX Research Journal, 22(1), 135–141. 10.2478/aut-2020-0051.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method