Abstract

Integrating electronic components into smart textiles revolutionised the field, with snap fasteners often serving as electrical connectors. This study investigated the electrical and mechanical durability of sewn-on snap fasteners under cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of direct current (DC) flowing through them. The available literature indicates that snap fasteners can endure repeated mechanical stresses; however, there is a lack of data regarding their behaviour during the cyclic interruption of DC flow. This research fills this gap by analysing changes in electrical resistance and unfastening forces over 10,000 cycles of current interruption. Results indicate that larger snap fasteners offer greater mechanical resistance, although size does not significantly impact electrical durability. For example, the average force needed to release the snap fasteners after 10,000 cycles is reduced to 5 N for large snap fasteners and 2 N for the small ones. This article also discusses how the substrate fabric and the type of thread used to attach the snap fastener affect the electrical strength of the tested connector. The findings presented offer valuable insights for designing and selecting materials in future smart textile applications, thereby enhancing the robustness and functionality of wearable electronics.

1 Introduction

In the twenty-first century, the field of smart textiles has experienced rapid advancements, merging traditional textile materials with cutting-edge electronic components to create innovative and functional garments. Smart textiles, also known as e-textiles, integrate sensors, actuators, and other electronic devices directly into the textiles, enabling a wide range of applications that extend far beyond conventional clothing. These intelligent textiles are being developed for various purposes, including health monitoring [1,2,3,4,5,6,7], measurements of hazardous factors [8,9,10,11], and even active heating of clothing [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Smart clothing for health monitoring may include systems for measuring the ECG signal [1,2,3,4,6]. It can also measure other parameters such as temperature [2], respiration rate [4,6], or, for example, the movement of the monitored person [6]. Smart clothing that monitors hazardous factors may be useful, for example, for firefighters [8,9,10,11], while clothing with active heating [12,13,14,15,16,17] may be useful for people exposed to low temperatures.

In the rapidly evolving field of smart textiles, integrating electronic components into clothing has opened new avenues for innovation. Electrical wires are very often needed in this type of garment. These wires can be made from electroconductive threads or strips crafted from electroconductive flat textile products, such as fabrics. These strips can be sewn or glued onto clothing. Additionally, an electrical connector is often necessary to allow the disconnection of these wires. One possible solution is to use clothing snap fasteners attached to a textile wire as a connector. These elements must maintain reliable electrical performance despite the mechanical stresses of repeated fastening and unfastening.

There are many types of clothing snap fasteners. They differ, among other factors, in the method of attachment to the substrate: sewing, crimping, or using an attaching machine. The suitability of clothing snap fasteners as electrical connectors in smart garments has been tested previously [18,19]. Ugale et al. [18] tested several clothing snap fasteners attached using a snap fastener attaching machine. This machine clamps both parts of the mounted snap fastener onto the textile material. The clothing snap fasteners tested by Ugale et al. varied in their fastening and unfastening forces. Ugale et al. concluded that the connectors of low (average unfastening force AUF = 9.98 N) and medium unfastening forces (AUF = 17.27 N) could withstand all 5,000 cycles. The connector with a high fastening–unfastening force (AUF = 26.61 N) level failed before 1,000 fastening–unfastening cycles were complete. Ugale et al. also stated that conductors' fastening–unfastening at low force levels gave the highest overall conductance in all tested interconnects. Leśnikowski [19] investigated the usefulness of crimped clothing snap fasteners as electrical connectors in high-speed textile transmission lines. Leśnikowski demonstrated that the two parts of a short coplanar textile transmission line connected with “spring” and “S-spring” snap fasteners, i.e. having wire springs of a different shape, can transmit a digital signal in digital systems where the maximum frequency does not exceed 350 MHz. Fortes Ferreira et al. [20] explored the electrical robustness of conductive textile snap fasteners for wearable devices in different human motion conditions. They demonstrated that the spring snap fasteners (with a spring-based engaging mechanism) mounted in the garment presented a sub-optimal performance under high motion and load conditions (walking and rope jumping).

The tests of the resistance of snap fasteners to repeated fastening and unfastening presented in the literature were conducted in a zero current state. The influence of mechanical factors on the suitability of the snap fasteners as electrical connectors was thus demonstrated. In real use, the resistance of snap fasteners to repeated fastening and unfastening is influenced not only by mechanical wear but also by wear caused by phenomena occurring during the interruption of current flow caused by unfastening the snap fastener. This is particularly important in applications where high-intensity current is interrupted, for example, in smart clothing with active heating [12,13,14]. Moreover, the possibility of using snap fasteners as electrical connectors in smart garments is influenced not only by the snap fastener itself but also by its connection to the textile electroconductive material and the kind of material used. Therefore, this study also presents the influence of the type of textile substrate on which the snap fasteners were attached and the type of thread used to sew them on the electrical and mechanical durability of the textile electrical connector. In the tests presented in this article, current flowed through the tested snap fasteners when fastened and unfastened. This ensures that the wear of the snap fastener is tested not only under the influence of mechanical factors, e.g. friction but also electrical factors that occur when the current flowing through the snap fasteners is interrupted when they are disconnected. The article includes a description of the measuring stand, an overview of the construction of the tested connectors, and the results of the measurements obtained, with their statistical analysis.

The presented study investigates the changes in the electrical resistance of snap fasteners under cyclic fastening–unfastening. By understanding how repeated use affects the electrical properties of these connectors, we aim to enhance the durability and functionality of smart garments. This research provides valuable insights into the design and material selection for future smart textile applications.

2 Materials and methods

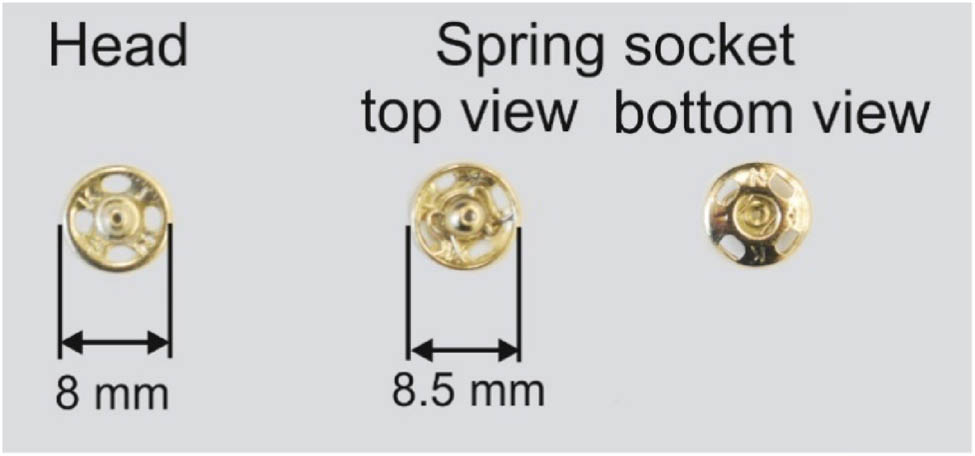

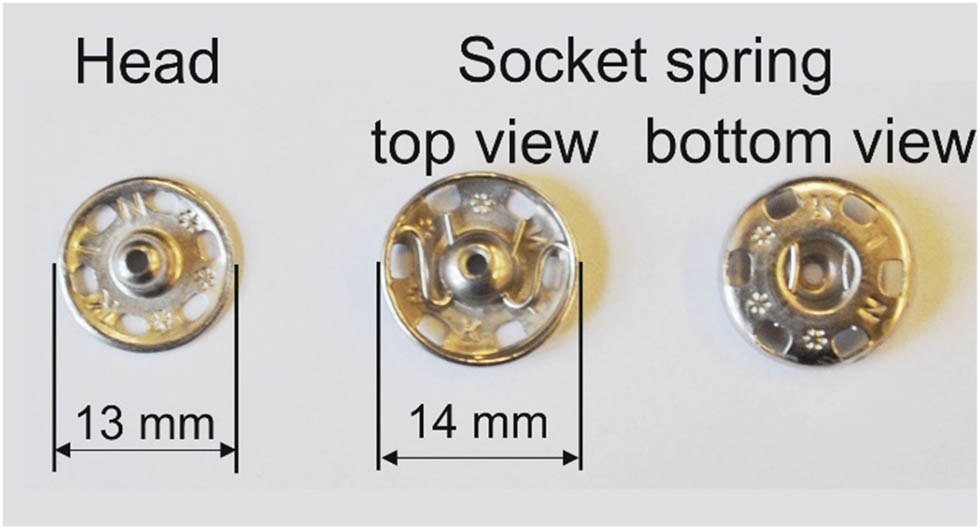

The connectors evaluated in the tests consisted of strips of electroconductive fabric with snap fasteners sewn onto them. Sewn-on snap fasteners from KOH-I-NOOR® were used to create the connectors, characterised by a two-component structure comprising a spring socket and a head. A model made of brass and coated with nickel was chosen, as it is ideal for conducting electricity. Two sizes were used to test whether the conductivity of electricity would depend in any way on the dimensions of the snap fastener. A smaller snap fastener, with a head diameter of 8 mm and a spring socket diameter of 8.5 mm, is illustrated in Figure 1. The larger size, with a head diameter of 13 mm and a spring socket diameter of 14 mm, is shown in Figure 2. In the remainder of the article, the terms small and large snap fasteners are employed to facilitate the identification of the tested samples.

Two parts of a small clothing snap: head and spring socket.

Two parts of a large clothing snap: head and spring socket.

These snap fasteners were hand-sewn onto electrically conductive fabrics, and the parameters are presented in Table 1.

Basic parameters of electroconductive fabrics (manufacturer’s data)

| Trade name/producer | Material | Weave | Thickness, | Surface resistivity, | Surface mass, | Warp density, | Weft density, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | mm | Ω/sq | g/m2 | yarns/cm | yarns/cm | ||

| Berlin RS/Shieldex | 60% polyamide + 14% Ag + 25% conductive polyurethane | Ripstop | 0.100 | 0.300 | 58 | 48–50 | 45–49 |

| Nora Dell CR/Shieldex | Polyamide + 48% Cu + 7% Ag + 4% NI + 9% CR coating | Ripstop | 0.125 | 0.009 | 110 | 48–50 | 45–49 |

The selected fabrics differ significantly in surface resistivity and surface mass. The remaining parameters (shown in Table 1) are identical or similar. This selection of fabrics aimed to examine the impact of both parameters on the durability of the connector.

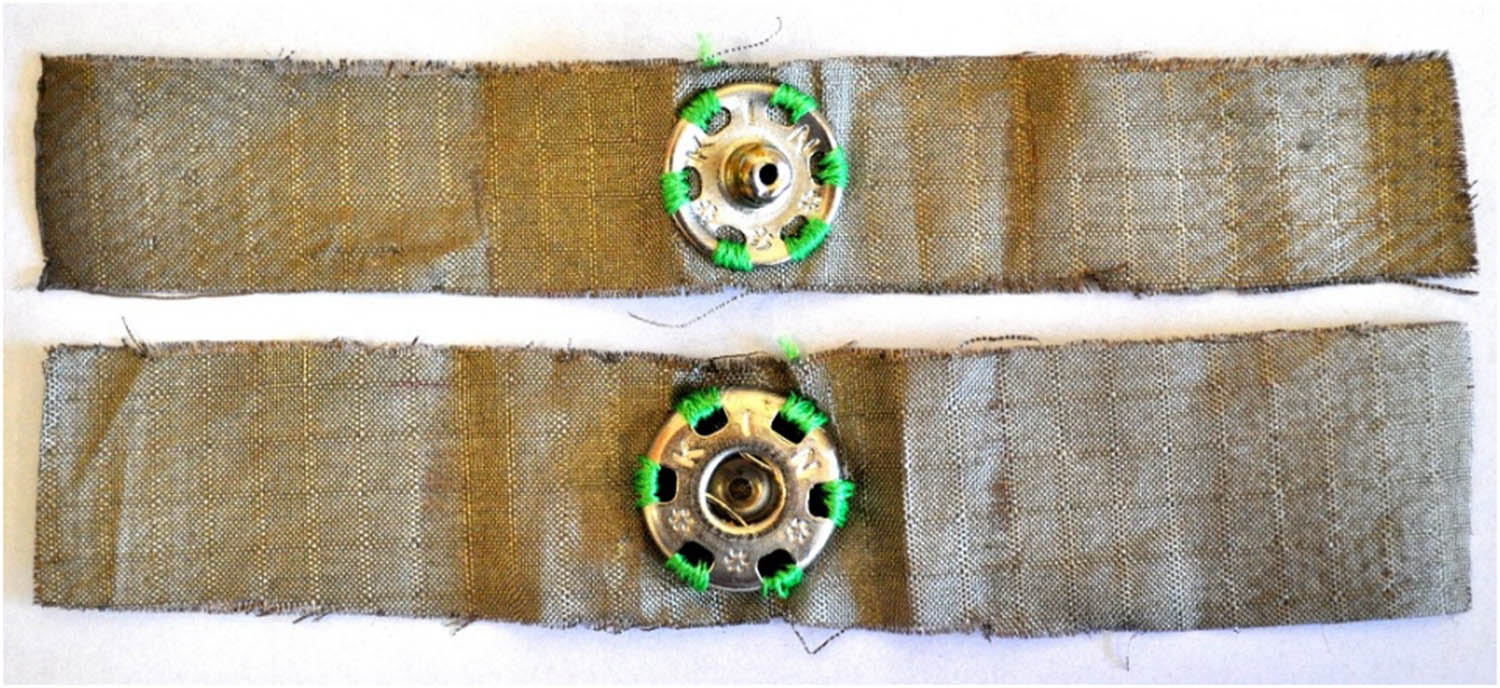

The 15 mm-wide strips were cut from the fabrics, as shown in Table 1. The snap fasteners shown in Figures 1 and 2 were then sewn onto these strips. Two types of samples were prepared. In the first one, the snap fasteners were sewn with a non-conductive thread, and the second one with an electroconductive thread. The basic parameters of the electroconductive thread are presented in Table 2. Figures 3 and 4 show examples of the appearance of the tested Nora Dell and Berlin RS samples, respectively.

Basic parameters of the electroconductive thread used to sew the tested clothing snap fasteners (manufacturer’s data)

| Thread name/producer | Material | Metallisation metal, | Mass of non-metallised fibres, | Mass of fibres after metallisation, | Electrical resistivity, | Tenacity, |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | dtex | dtex | Ω/m | cN/tex | ||

| 235-36 x2 HCB/Shieldex | Nylon 6.6 | 99.9 Ag | 476 ± 6 | 605 ± 10 | 80 ± 30 | 50 ± 10 |

The appearance of the tested Nora Dell fabric sample (with a large snap fastener attached to a non-conductive thread).

The appearance of the tested Berlin RS fabric sample (with a small snap fastener attached to an electroconductive thread).

The non-conductive thread used was the IRIS 40N machine embroidery thread from Ariadna®. With a linear weight of 130 dtex x2, this thread is characterised by high mechanical strength and resistance to high temperature, washing, and chemical factors.

Using the above materials, three samples were made for each combination of materials differing in the snap fastener size, type of fabric, and thread. As a result, 24 samples were made for testing.

2.1 Measured electrical properties

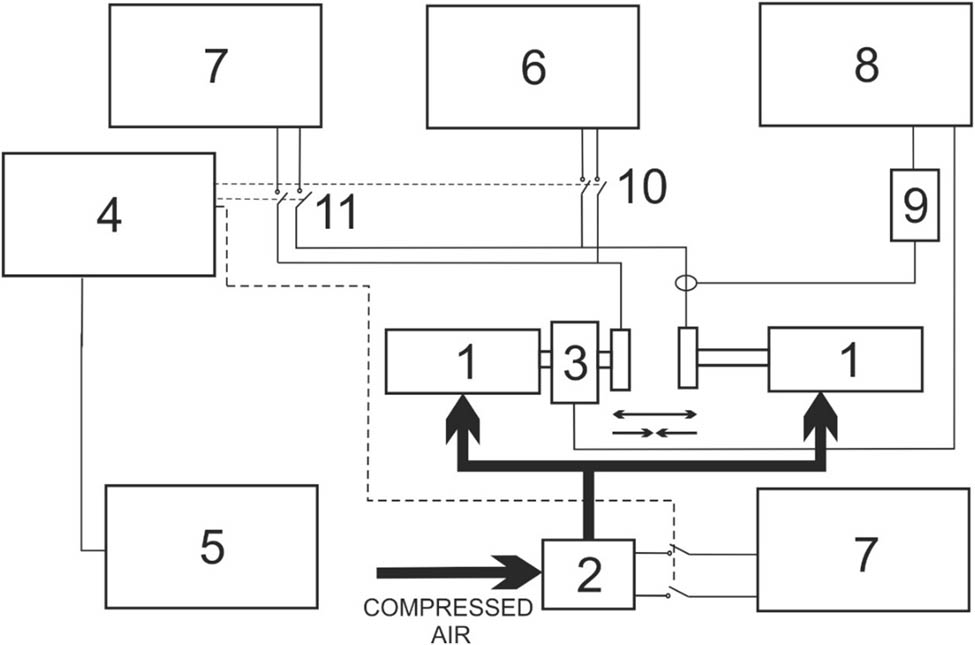

All presented measurements in this study were carried out under a specific standard atmosphere at 23°C and 50% relative humidity according to Standard atmospheres for conditioning and testing of textile materials [21]. In the primary part of the research, measurements of the electrical resistance of the snap fasteners, along with fragments of the connected strips of fabric, were carried out. An Agilent 34410A multimeter operating in 4-wire mode, with an accuracy of ±0.0030% of reading +0.003 Ω, was used. Then, tests were carried out to determine changes in the connector resistance depending on the number of cycles of fastening and unfastening the tested connectors. The measuring equipment is shown in Figure 5.

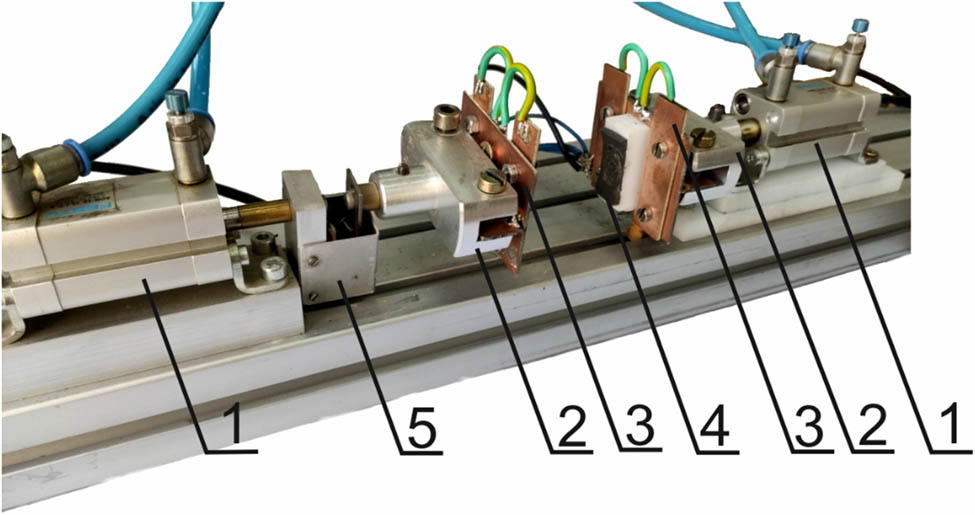

The measuring equipment for determining changes in connector resistance depending on the number of its fastening and unfastening cycles.

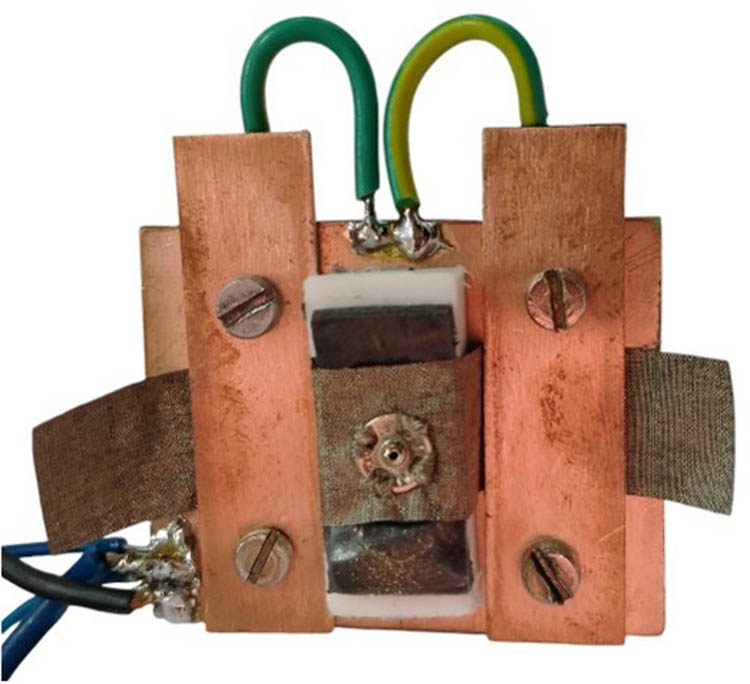

The measuring equipment consists of two pneumatic actuators (1), an electro valve (2), a force sensor (3), a data acquisition board (4), a PC (5), an Agilent 34410A multimeter (6), two direct current (DC) power sources (7), and Tektronix digital oscilloscope (8) equipped with a current probe (9). Pneumatic actuators, controlled by an electro valve (2), connect and disconnect the tested samples. The piston rods of these actuators are equipped with sample mounting holders, shown in Figure 6. These piston rods extend and retract cyclically, causing the clothing snap fasteners in the tested samples to fasten and unfasten. The ends of the tested samples are mounted between two plates (3) (Figure 6) made of copper laminate, which is usually used to produce printed circuit boards (Figure 7). These plates are also connected via relay (10) (Figure 5) to an Agilent 34410A multimeter, assuring the resistance measurement. Additionally, they are connected via another relay (11) (Figure 5) to the DC power supply. Relays (10) and (11) (Figure 5) allow the disconnecting of the Agilent multimeter and power supply from the ends of the tested samples. This is necessary to ensure correct (in a voltage-free state) resistance measurement by an Agilent multimeter.

Sample mounting holders and pneumatic actuators (1 – pneumatic actuators, 2 – clamps, 3 – sample mounting holders, 4 – foam, 5 – force sensor).

Mounting holders with the sample mounted.

One of the pneumatic actuators is equipped with a force sensor (3) (Figure 5), (5) (Figure 6), ensuring compressive force control during the electrical resistance measurement. The signal from the force sensor is acquired by Tektronix’s digital oscilloscope (8) (Figure 5) and displayed on its screen. This oscilloscope, fitted with a current probe (9), also measures the current flowing through the tested samples during its cyclical fastening and unfastening.

The method of mounting the tested samples is shown in Figure 7.

Each cycle of fastening and unfastening clothing snap fasteners consists of the following stages:

Connection of the DC power supply to both parts of the tested connector.

Applying compressed air to the actuators causes their piston rods to extend and the two parts of the snap fasteners to connect. This initiates the flow of a 5-A DC through the strips of electroconductive fabric and their attached snap fasteners.

Disconnecting the voltage from the tested connector using a relay (11) (Figure 5).

Connecting the Agilent multimeter using a relay (10) (Figure 5) and measuring the resistance of the tested connector.

Disconnecting the Agilent multimeter after measurement.

Reconnecting the DC power supply to both parts of the tested connector.

Retraction of the pneumatic actuator piston rods, which causes disconnection of the two parts of the snap fasteners and interruption of the flowing 5 A current.

The PC (5) with the procedure written in LabVIEW software ensures the correct execution of all steps of the measurement cycle presented above. For each of the prepared 24 samples, the described procedure was performed 10,000 times. The adopted value of 10,000 cycles results from the assumption that the fastener will be used in clothing with an assumed durability of approximately 3 years, and the fastener will be unfastened and fastened ten times a day. As a result of the measurements, the dependence of the connector resistance on the number of fastening and unfastening cycles was obtained. Each of the measured resistance values R is influenced by the contact resistance of both parts of the snap fasteners R s, the resistance between the textile substrate and the press stud R st, and the resistance of the substrate strips between the press stud and the measuring terminal R t. The following formula illustrates this:

The obtained electrical resistance results are, therefore, a comprehensive measure of the resistance of an electrical connector in the form of a snap fastener, which is influenced not only by changes in its resistance but also by changes in other resistances mentioned earlier.

2.2 Measured mechanical properties

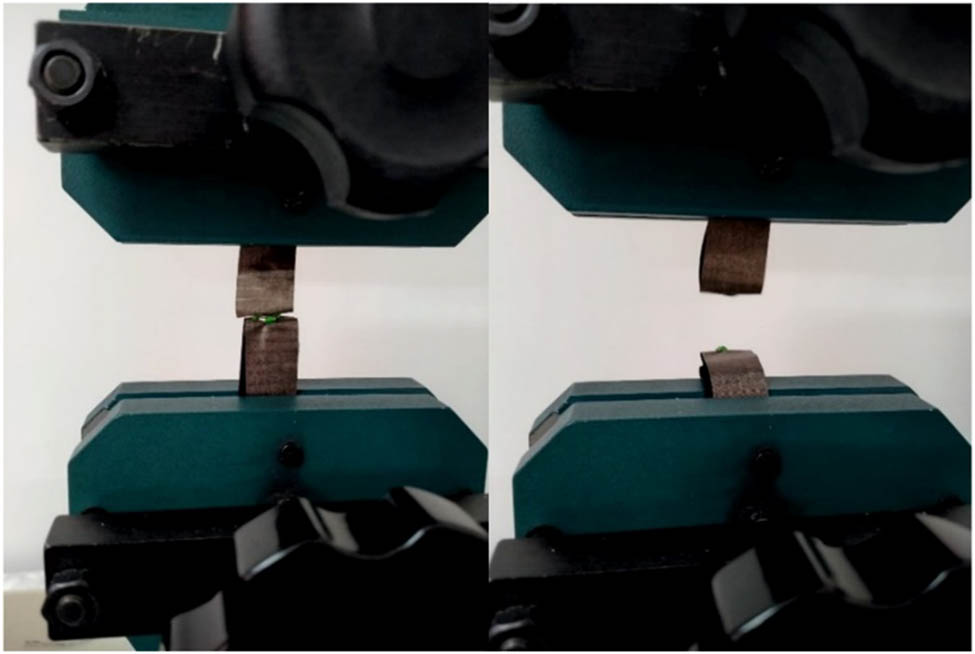

The force required to open the snap fastener is one of the most important parameters determining its suitability as an electrical connector. A small force causes poor adhesion of both snap fastener parts, resulting in increased connector resistance. Therefore, tests were carried out to determine the changes in this force depending on the number of fastening–unfastening cycles. The Hounsfield H10KS strength testing machine was used to do this. Figure 8 shows the method of mounting the sample for this measurement.

Unfastening force tests (before and after unmatted).

For each tested connector, the tensioning force of clothing snap fasteners was measured five times before and after 10,000 unfastening cycles, and the average values were calculated.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Electrical properties

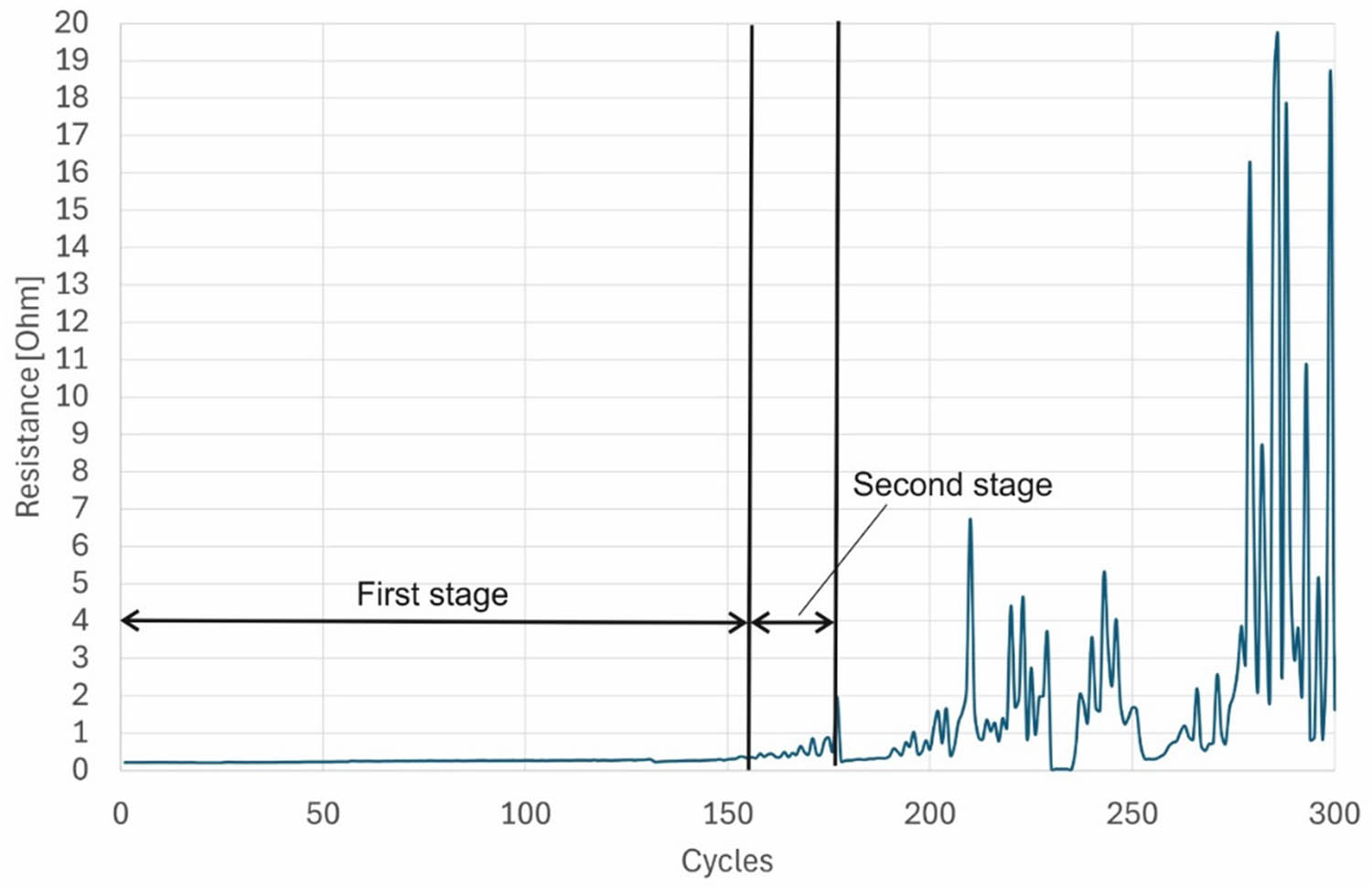

Figure 9 illustrates an example of variations in the sample resistance caused by cyclic fastening and unfastening. The resistance is minimal in the first stage of the test, and its values do not change significantly from one another, as shown in Figure 9. Then, during the second stage, there is an increase in the scatter of the measured resistance. Next, after another cycle, a very high resistance value appears, many times higher than the initial value. The number of cycles corresponding to this resistance indicates the maximum number of cycles up to which the switch connects correctly. This number shows the durability of the connector expressed in connection–disconnection cycles.

The sample resistance changes due to cyclic fastening and unfastening (large snap, sewn with non-conductive thread to Berlin fabric).

For further analysis, the length of the first stage was determined for each of the tested samples. It is assumed that the first stage ends when a resistance is twice as high as the average resistance calculated for the first ten cycles appears for the first time. For simplicity, the length of the first stage expressed in cycles is called the number of cycles used in the rest of the article.

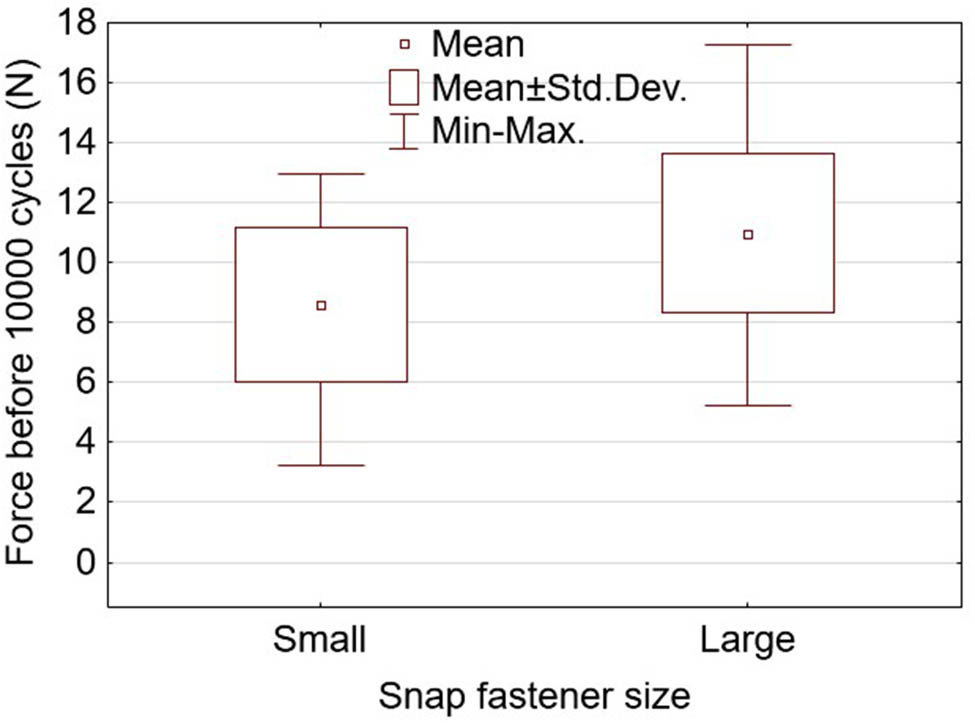

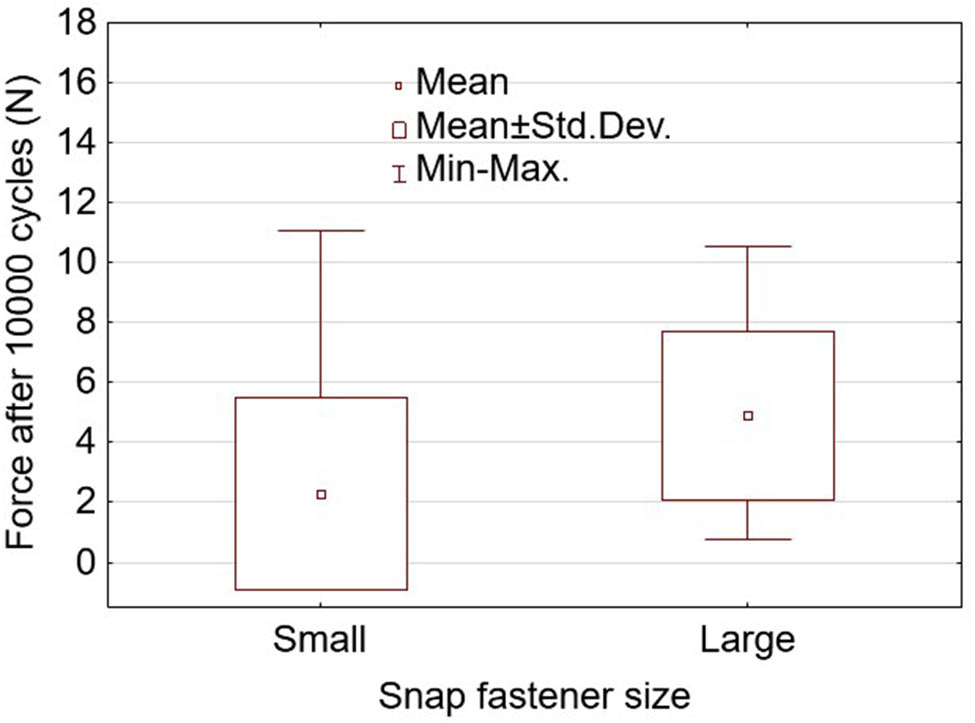

3.2 Mechanical properties

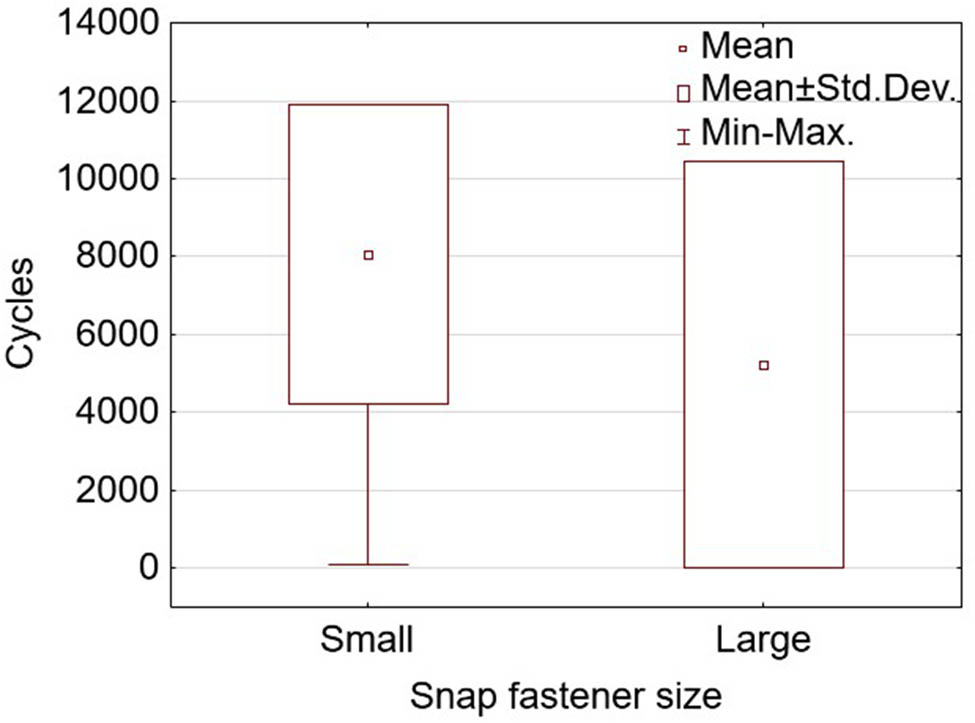

The unfastening force values taken before and after 10,000 unfastening cycles are shown in Figures 10 and 11, respectively.

Unfastening force before performing 10,000 unfastening cycles for small and large snap fasteners (new snap fasteners were not used earlier).

Unfastening force after performing 10,000 unfastening cycles for small and large snap fasteners.

A comparison of Figures 10 and 11 shows that the unfastening force of the tested snap fasteners decreases after 10,000 unfastening cycles. Snap fasteners of larger size provide higher unfastening force, making them more suitable for constructing electrical connectors. In the case of small-sized snaps, it was noted that 4 out of 12 tested snap fasteners did not fasten after 10,000 cycles. This means that these snap fasteners are completely mechanically destroyed. Therefore, from this perspective, larger snaps should be employed where the garment’s user frequently unfastens them.

3.3 Statistical analysis of the obtained results

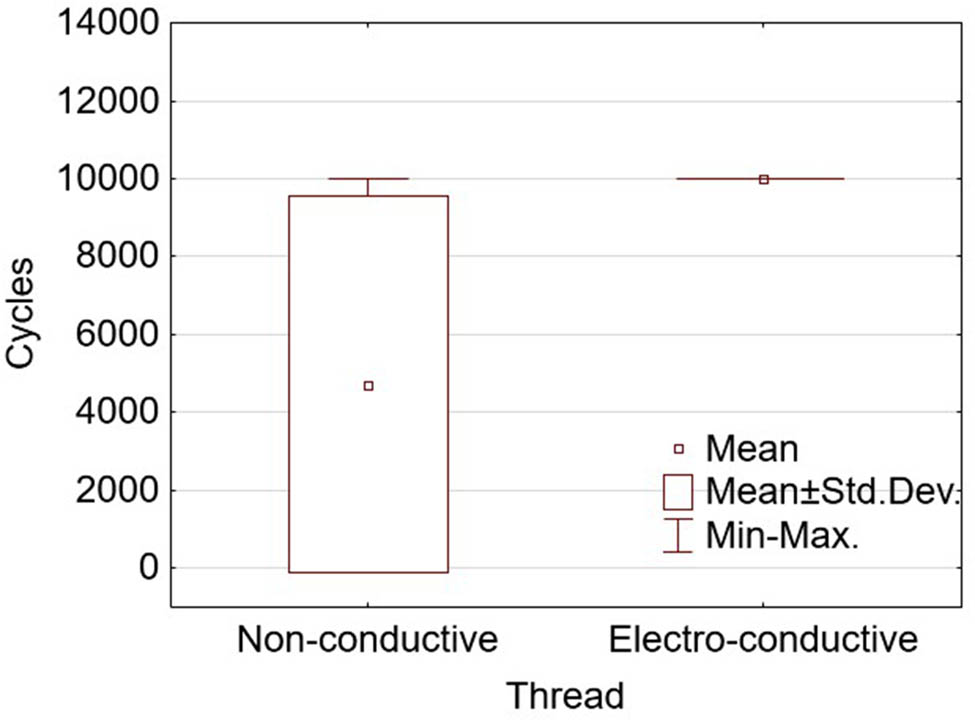

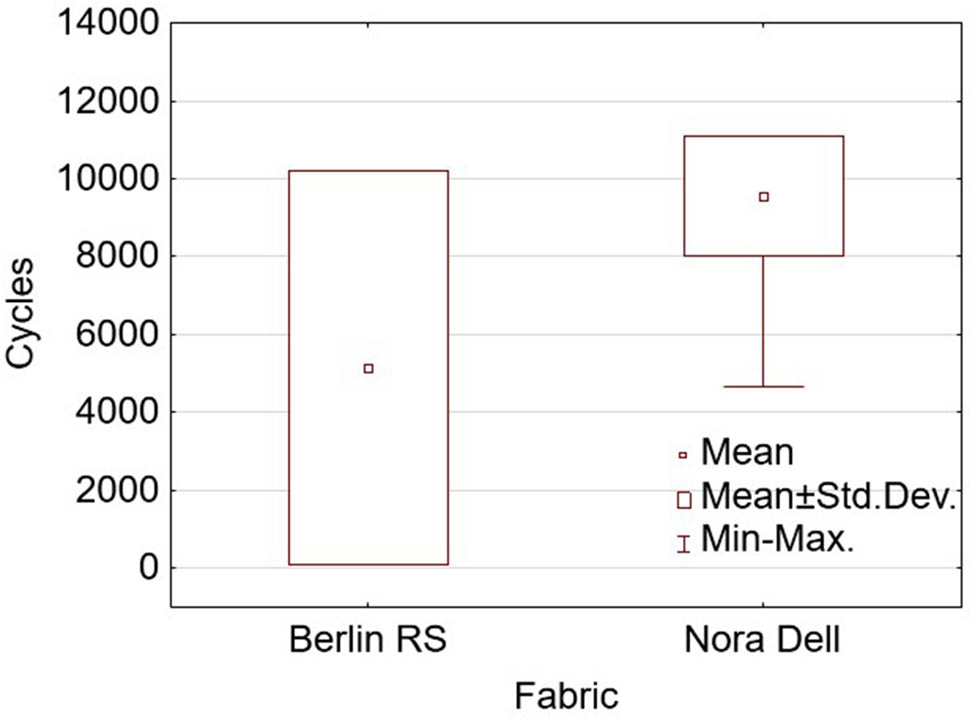

The length of the first stage (Figure 9) in cycles was determined for each tested sample to enable statistical analysis of the obtained results. The study examined the influence of snap fastener size, thread electrical conductivity, and substrate material on the number of cycles reflecting the snap fastener’s electrical durability. Non-parametric tests were used instead of the multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA). This was due to the lack of normality of group distributions determined by variables and the lack of homogeneity of variance, which failed to meet the assumptions of ANOVA. The TIBCO Statistica® software was used to perform all statistical calculations. For analysis, the obtained measurement results were divided three times into two groups differing in the size of the snap fastener, the thread’s electroconductivity, and the substrate material. The Mann–Whitney U test was performed for each division. This test aimed to determine whether the first stage length, measured as the average number of cycles for two groups of samples differing in size, substrate material, and electrical conductivity of the thread, was statistically significantly different. To do this, the null hypothesis H0 was accepted, assuming the equality of the mean value of the number of cycles for each group. The test result was the probability p-value that the assumed null hypothesis is true. Comparing the obtained p-value with the assumed significance level of 0.05, it can be decided if the H0 hypothesis should be rejected. The test results are shown in Table 3. Table 3 indicates that the mean number of cycles across groups differing in snap fastener size does not exhibit statistically significant differences.

U Mann–Whitney test results

| Groups differing in | p-value | H0 hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| Snap fastener size | 0.339856 | Accepted |

| Electroconductivity of threads | 0.002856 | Rejected |

| Material of the substrate | 0.019493 | Rejected |

This means that the size of the tested snap fasteners has no statistically significant effect on the electrical durability of the tested samples. The type of substrate used and the electrical conductivity of the thread used have a statistically significant effect on the length of the first stage (Figure 9), expressed as the number of cycles. The relationship between the average number of cycles causing the first signs of wear for two groups of connectors differing in thread electroconductivity, substrate material, and snap fastener size is shown in Figures 12–14. These figures also display the standard deviation of the results obtained, along with their maximum and minimum values. As shown in Figure 12, the standard deviation value of zero for the snap fasteners sewn with electroconductive thread indicates that all snaps showed no electrical wear after 10,000 cycles.

The dependence of the number of cycles causing signs of first wear on the type of thread.

The dependence of the number of cycles causing signs of first wear on the substrate fabric.

The dependence of the number of cycles causing signs of first wear on the snap fastener size.

Therefore, Figure 12 shows that using an electroconductive thread significantly improves the contact between the snap fastener and the substrate (decreases the resistance value R st (equation (1)). This results in a constant, unchanging electrical resistance of the tested snap fasteners up to 10,000 cycles. The use of a non-conductive thread results in a much lower average number of cycles required for increased resistance dispersion to become apparent during repeated unfastening of the snap fastener compared to the use of an electroconductive thread.

Figure 13 shows that connectors with a substrate made of Nora Dell fabric exhibit greater resistance to repeated unfastening. The statistical analysis also showed that the substrate material to which the snap fastener is sewn has a statistically significant effect on the durability of the electrical connector. This is due to the large difference in surface resistivity and surface mass of the fabrics used. The surface resistivity values shown in Table 1 show that the Nora Dell fabric has significantly better electrical conductivity than the Berlin RS fabric. Additionally, the face and back sides of the Berlin fabric are different. The back side of this fabric is largely covered with conductive polyurethane, which further reduces its electrical conductivity. Therefore, fabrics with such coatings should be avoided to obtain a connector with the greatest possible resistance to repeated unfastening.

Figure 14 shows that connectors with small snap fasteners are slightly more resistant to cyclic fastening and unfastening than those with large ones. The statistical test performed (Table 3) did not confirm this due to the large scatter of the measurement results.

4 Conclusions

The presented study investigated sewn-on snap fasteners’ electrical and mechanical durability under cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of DC flowing through them. The presented research analyses the changes in electrical resistance and unfastening force during 10,000 cycles of fastening and unfastening with simultaneous switching of the current flowing through the tested connector. The conducted tests and statistical analysis of the usability of sewn-on clothing snap fasteners as electrical connectors demonstrated that these fasteners are suitable for use in electrical circuits carrying currents up to 5 A. Larger clothing snap fasteners are characterised by greater mechanical resistance to repeated unfastening. The average force needed to release the snap fasteners after 10,000 cycles is reduced to 5 N for large snap fasteners and 2 N for small snap fasteners. However, this does not affect changes in their electrical resistance.

The usefulness of the tested snap fasteners is determined not only by their construction but also by the textile substrate on which they are placed and the electrical conductivity of the thread with which they are sewn. The use of electroconductive thread to sew the snap fastener significantly improves the durability of the tested electrical connectors. All connectors where the snap fasteners were sewn with electroconductive thread exhibited no significant change in resistance after 10,000 unfastening cycles. The substrate fabric intended for making a connector using sewn-on snap fasteners should have the best possible electrical conductivity (very low surface resistivity). At the same time, fabrics largely coated with polyurethane should be avoided, which reduces the connector’s durability. The obtained results provide valuable guidance for material selection and design optimisation in future smart textile applications, contributing to improved durability and performance of wearable electronics.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Leśnikowski J. developed the research idea, conducted the analysis of the obtained results, and wrote the article. Szewczyk M. performed all the measurements used in the article, analysed the obtained results, and created some of the figures included in the article.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Lin, C. C., Yang, C. Y., Zhou, Z., Wu, S. (2018). Intelligent health monitoring system based on smart clothing. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 14(8), 1–9.10.1177/1550147718794318Search in Google Scholar

[2] Chen, M., Ma, Y., Song, J., Lai, C. F., Hu, B. (2016). Smart clothing: Connecting human with clouds and big data for sustainable health monitoring. Mobile Networks and Applications, 21(5), 825–845.10.1007/s11036-016-0745-1Search in Google Scholar

[3] Majumder, S., Mondal, T., Deen, M. J. (2017). Wearable sensors for remote health monitoring. Sensors, 17(130), 1–45.10.3390/s17010130Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Özyazgan, V., Abdulova, V. (2015). Utilization of smart textiles in healthcare. International Journal of Electronics, Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering, 5, 1025–1033.10.17932/IAU.IJEMME.m.21460604.2015.5/4.1025-1033Search in Google Scholar

[5] Ellouze, B., Damak, M. (2024). The use of smart textiles in the healthcare space: Towards an improvement of the user-patient experience. Journal of Textile Science and Technology, 10(2), 41–50.10.4236/jtst.2024.102003Search in Google Scholar

[6] Coyle, S., Diamond, D. (2016). Medical applications of smart textiles. In: L. Van Langenhove, (Ed.), Advances in smart medical textiles, I ed., Woodhead Publishing (Oxford).10.1016/B978-1-78242-379-9.00010-4Search in Google Scholar

[7] Libanori, A., Chen, G., Zhao, X., Zhou, Y., Chen, J. (2022). Smart textiles for personalized healthcare. Nature Electronics, 5(3), 142–156.10.1038/s41928-022-00723-zSearch in Google Scholar

[8] Caya, M. V. C., Casaje, J. S., Catapang, G. B., Dandan, R. A. V., Linsangan, N. B., (2018). Warning system for firefighters using E-textile. 3rd International Conference on Computer and Communication Systems (ICCCS) (pp. 362–366).10.1109/CCOMS.2018.8463320Search in Google Scholar

[9] Gniotek, K., Gołębiowski, J., Leśnikowski, J. (2009). Temperature measurements in a textronic fireman suit and visualisation of the results. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 17(1 (72)), 97–101.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Soukup, R., Blecha, T., Hamacek, A., Reboun, J. (2014). Smart textile-based protective system for firefighters. 5th Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference, ESTC 2014 (pp. 1–5).10.1109/ESTC.2014.6962821Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang, X., Tian, M., Li, J. (2024). Influence of smart textiles on the thermal protection performance of firefighters’ clothing: a review. The Journal of The Textile Institute, 115(9), 1476–1489.10.1080/00405000.2023.2234237Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wu, Y., Wang, Z., Xiao, P., Zhang, J., He, R., Zhang, G. H., et al. (2022). Development of smart heating clothing for the elderly. The Journal of The Textile Institute, 113(11), 2358–2368.10.1080/00405000.2021.1983964Search in Google Scholar

[13] Krzemińska, S., Greszta, A., Bartkowiak, G., Dąbrowska, A., Kotas, R., Pękosławski, B., et al. (2023). Evaluation of heating inserts in active protective clothing for mountain rescuers – preliminary tests. Applied Sciences, 13(8), 1–19.10.3390/app13084879Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ma, L., Li, J. (2023). A review on active heating for high performance cold-proof clothing. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 35(6), 952–970.10.1108/IJCST-03-2021-0036Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wang, F., Gao, C., Kuklane, K., Holmér, I. (2010). A review of technology of personal heating garments. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics: JOSE, 16, 387–404.10.1080/10803548.2010.11076854Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Sahin, O., Kayacan, O., Bulgun, E. Y. (2005). Smart textiles for soldier of the future. Defence Science Journal, 55(2), 195–205.10.14429/dsj.55.1982Search in Google Scholar

[17] Padleckienė, I., Stygienė, L., Krauledas, S. (2020). Development and investigation of a textile heating element ensuring thermal physiological comfort. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 28(5(143)), 56–62.10.5604/01.3001.0014.2385Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ugale, P., Lingampally, S., Dieffenderfer, J., Suh, M. (2024). Wearable solutions: Design, durability, and electrical performance of snap connectors and integrating them into textiles using interconnects. Textiles, 4(3), 328–343.10.3390/textiles4030019Search in Google Scholar

[19] Leśnikowski, J. (2016). Research on poppers used as electrical connectors in high speed textile transmission lines. Autex Research Journal, 16(4), 228–235.10.1515/aut-2016-0025Search in Google Scholar

[20] Fortes Ferreira, A., Alves, H., da Silva, H. P., Marques, N., Fred, A. (2024). Exploring the electrical robustness of conductive textile fasteners for wearable devices in different human motion conditions. Scientific Reports, 14(7872), 1–10.10.1038/s41598-024-56733-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] ISO 139. (2005). Textiles - Standard atmospheres for conditioning and testing, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method