Abstract

Mechanical textile recycling has great advantages over other types such as chemical or thermomechanical recycling. The main drawback of this textile-to-textile recycling technology is that the length of the fibres is reduced over successive recycling processes. In most cases, due to the length reduction, it is necessary to blend the recovered fibres with virgin fibres to obtain high-quality yarns that can be reincorporated into the textile value chain. Despite the maturity of the technology, this problem has yet to be fully resolved, and it continues to present a major technological challenge. This study aims to determine the optimum shredding conditions to recycle denim-like fabrics with an edge-trim opener machine. It also examines the effect of oiling pre-treatment on the retention of fibre length of the recovered fibres and the performance of yarns produced with the recycled fibres. The best results are achieved by processing the material in three shredding cycles at feeding and opening speeds of 0.3 m/min and 947 rpm, respectively. The addition of lubricant, although not having a significant effect on the efficiency of the defibration process, led to an improvement in the quality of the recycled yarn.

1 Introduction

With the development of global industrialization, the demand for textiles has also increased, resulting in the generation of a large amount of textile waste. Currently, the main methods of dealing with waste fabrics are incineration and landfill. The incineration of fabrics produces many harmful gases, and landfills pollute the soil. Therefore, recycling and reusing fabrics may effectively reduce the impact of fabric waste on the environment. There are three main ways to perform fibre-to-fibre textile recycling: thermomechanical recycling, chemical recycling, and mechanical recycling. Thermomechanical recycling involves melting the waste products of a single material (with or without prior repolymerization) to produce pellets, following a necessary pre-treatment. These pellets are used in melt-spinning processes to produce multifilament fibres and new textile products. Thermomechanical recycling has the advantages of being an environmentally friendly, low-cost, and simple process, but the applicable materials are limited to thermoplastic fibres. Chemical recycling refers mainly to the use of chemical processing technology for depolymerization to form new chemical fibres through a repolymerization and alignment process, ultimately creating new textiles. Another possibility for chemical recycling is the dissolution of waste products to produce new filaments by dry or wet spinning. This process is complex, and the materials used are expensive.

Compared to other methods of recycling, mechanical recycling is a more sustainable process. This form of recycling refers to the shredding of waste fabrics, directly opening them into fibres that can be reused. Mechanical recycling is convenient, simple, and environmentally friendly. It may be performed at small- and large-scale industrial production levels, and it is applicable to a variety of fibre products. The recycled fibres can be spun into yarn or used directly to create nonwoven products for reinforcing, acoustic, or thermal insulation materials, among others. Mechanical recycling may be applied to all types of fibres. The main problem of this mature technology not yet solved is that shredding waste textiles shortens fibre length, reducing fibre quality [1]. Conversely, the industrial process is not optimized for different textile types, as all are recycled together without conditions adapted to each structure and composition.

Mechanical recycling has recently attracted increased attention due to the textile waste accumulation problems. This has led to new publications over recent years. Aronsson and Persson [2] investigated the effect of worn garments on the quality of cotton fibres recovered from post-consumer denim and single-sided knit fabrics. They found that post-consumer waste with higher levels of wear did not experience as much fibre length loss as fabrics with lower wear levels, especially in the case of t-shirts having finer ring spun yarns. Furthermore, in jeans, the fibre length drop was found to be higher for garments with less wear. This suggests that even discarded fibre from heavily worn post-consumer garments may be a valuable raw material for spinning. Ütebay et al. [3] collected pre-consumer knitted cotton wastes and sorted them by fabric tightness and previous finishing (untreated greige cotton and dyed cotton). They examined as well the effect of the size of the pieces fed to the shredding machine on the quality of the recovered fibres. They found that higher quality recycled cotton fibres are achieved by shredding loosely knitted greige cotton fabrics in three passages with large feeding sizes, resulting in a lower short fibre ratio and higher yarn tenacity. In a similar way, Lindström et al. found that large rectangular-shaped samples were positive for retaining fibre length [4].

Conversely, it is well known that during the shredding process, the fabric rubs against the rollers, causing the fibres to break easily, ultimately resulting in a decreased fibre length [5]. The fibre’s frictional properties have a major influence on its behaviour during mechanical processing. Therefore, mitigating the friction between fibres during recycling may be a key factor in increasing the length of recycled fibres. Some studies have shown that oiling or wetting pre-treatment of the textile wastes could have a positive effect on the length of the recovered fibres.

For example, Taohai and Hefang found that a previous humidifying treatment increased the average fibre length of the recovered fibres compared to defibration at lower humidity conditions [6]. Other studies have used lubricants. Lindström et al. pre-treated fabrics with polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a lubricant before shredding and found that PEG treatment reduced the decrease of fibre length. Moreover, they found this lubricant addition allowed 100% recycled fibres to be spun into rotor yarns with greater tenacity [7]. Jingzhao et al. directly immersed cotton and polyester yarns in different reagents and measured their tenacity to determine if the treatment reduced inter-fibre friction and increased fibre slip within the yarn. They found that soybean oil could be a promising treatment to decrease inter-fibre friction cohesion and, as a consequence, facilitate the defibration process [8].

Although previous studies have examined the effects of fabric wear, fabric size, number of feeds, and lubricant addition on the shredding process, further research is necessary due to the numerous variables that influence the quality of the recovered fibres from mechanical recycling. The processing parameters (such as feeding and cylinder speeds, use of lubricant, or others) should be analysed for each machine configuration and fabric to improve the know-how of this mature technology.

In this experimental study, we identified the optimal parameters for recycling denim-like fabrics using an edge-trim opener machine. Initially, we examined how machine settings (feeding and opening speed) and shredding cycles impact the quality of the recovered fibres and the yarns produced from these fibres. Subsequently, we explored the effects of a lubricant pre-treatment on the length of the recovered fibres and the quality of the resulting yarn, using the machine conditions that yielded the best results.

2 Materials and experimental procedures

2.1 Materials

Waste fabric: Pre-consumer waste denim-like fabric having a mass of 388 g/m2, a thickness of 0.8 mm, a warp yarn density of 24 yarns/cm, and a weft yarn density of 17 yarns/cm. Both warp and weft are OE-rotor yarns with a yarn linear density of 90.2 tex for the warp and 80 tex for the weft yarns.

Oil agent: ISOIL 34 provided by COGELSA, Spain.

Surfactant used to prepare the oil dispersion: ADRAMOLL.

2.2 Experimental procedures

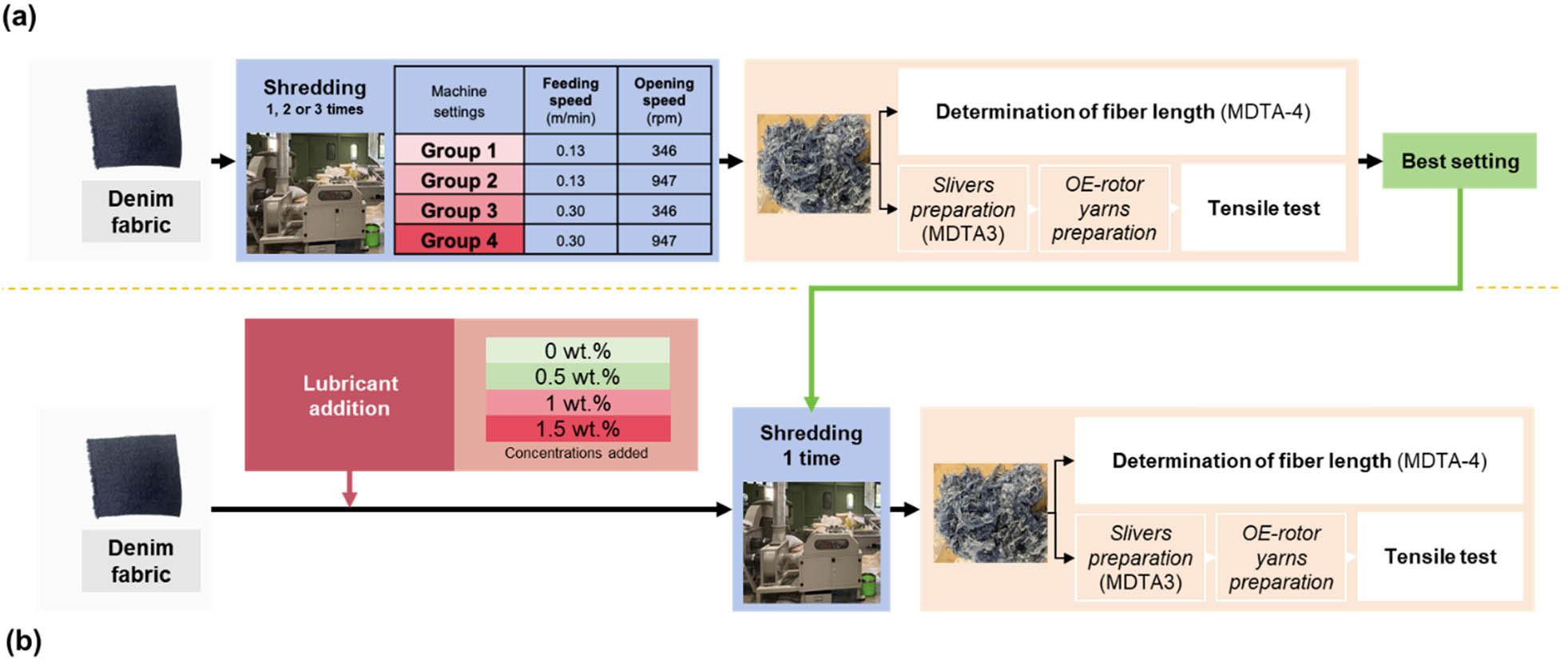

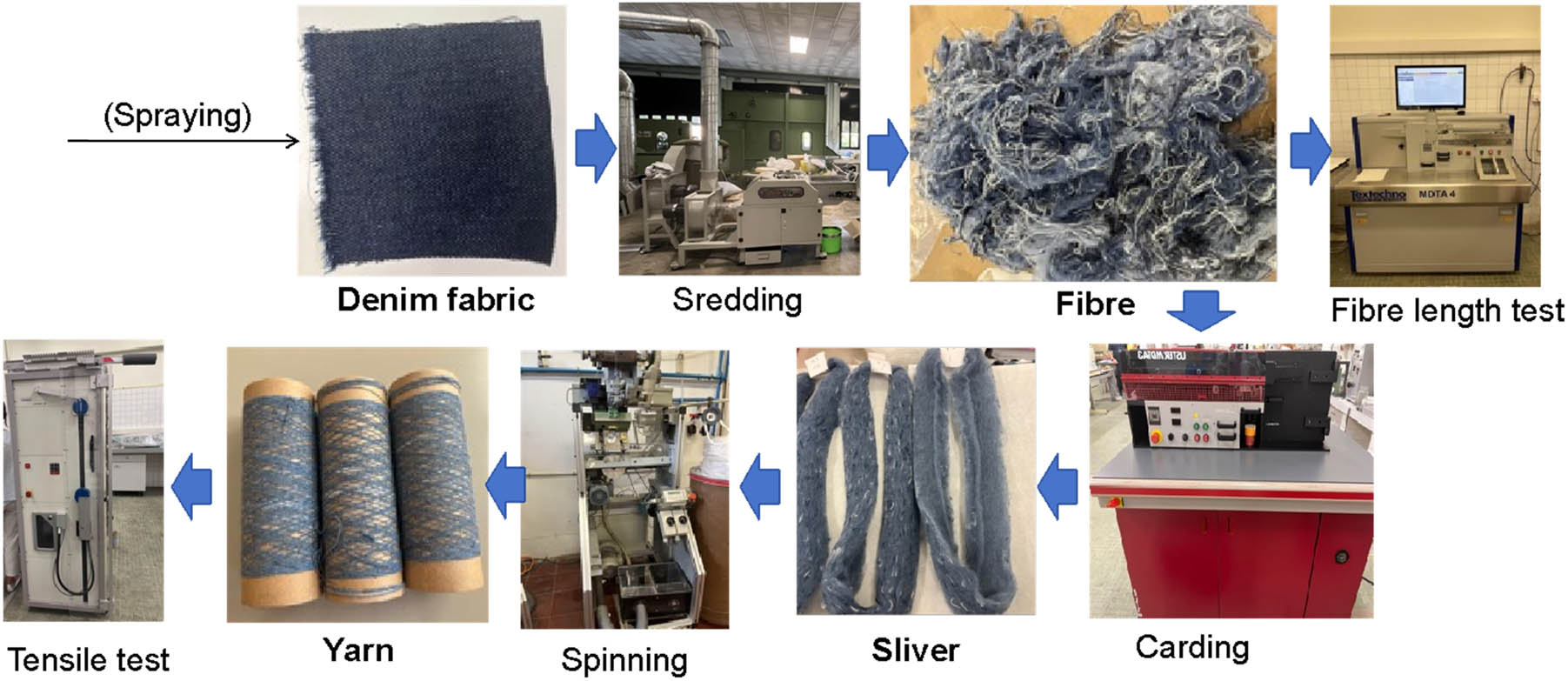

The flowchart for the experimental procedure and images of the materials and equipment used are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Total flow of the experiment to study (a) the effect of the machine shredding parameters and (b) lubricant addition on the quality of the recycled fibres and yarns.

Images of the materials and machinery used for the denim fabric mechanical recycling and testing process.

The specific experimental steps are explained in the following subsections.

2.2.1 Defibration process

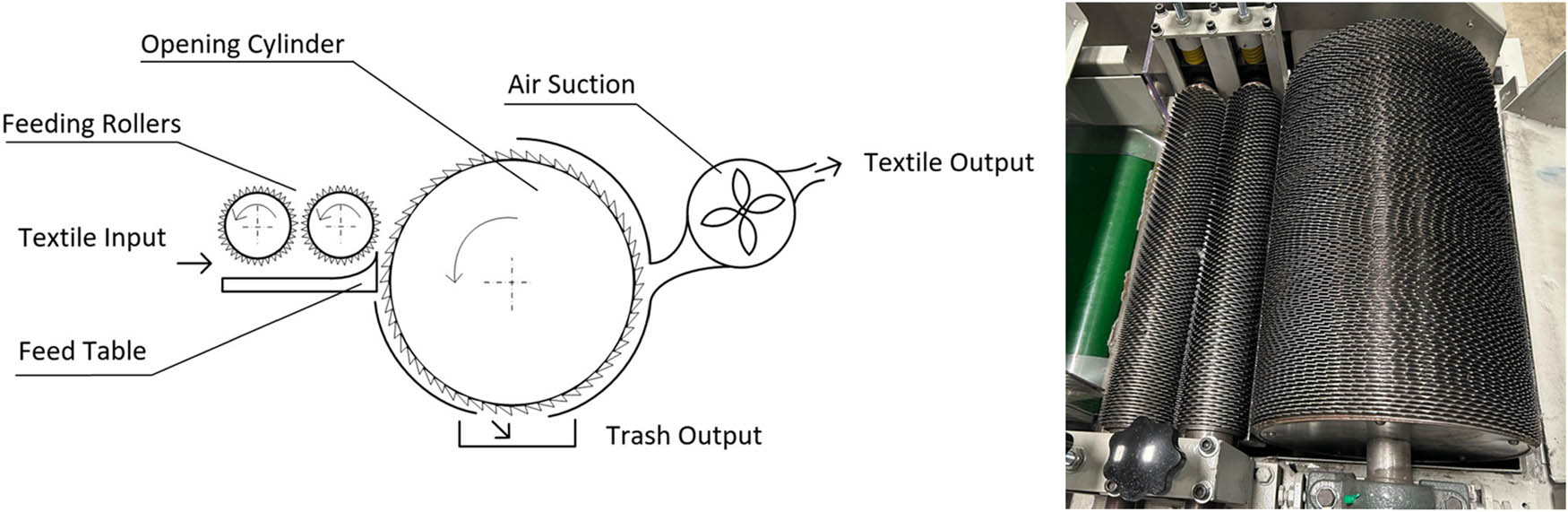

The fabric was cut into 20 × 10 cm2 pieces, divided into four groups, and fed into the defibration machine (Edge-trim opener machine KTRL600 of Qingdao Kingtech Machinery Co., Ltd.; Figure 3) with distinct parameter settings as shown in Table 1.

Scheme of the opener machine used for defibration (left) and photographic image of the feeding rollers and opening cylinder (right).

Shredding machine setting

| Group | Feeding speed Sf (m/min) | Opening speed Sd (rpm//m/min) | Clothing beats density (1/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.13 | 346//342 | 211 |

| 2 | 0.13 | 947//937 | 577 |

| 3 | 0.30 | 346//342 | 91 |

| 4 | 0.30 | 947//937 | 250 |

Two speed levels were chosen for both feeding and opening to study the typical speed range in which the machine used in this study operates. The low opening speed was selected to prevent fibres from attaching to the clothing of the opening cylinder. The high speed was approximately three times the low speed. Feeding speeds were chosen from both the low and high ranges, corresponding to low and high productivity. The combination of these speeds and the clothing’s linear density allows us to calculate the clothing beats density parameter, which represents the number of clothing beats per unit length of the fed material.

The experimental shredding procedure was as follows: For each group, 500 g of cut pieces were fed into the opener machine and shredded under the specific group’s Sf and Sd conditions. After the first shredding cycle, the textile and trash outputs were weighed (Figure 3-left). The textile output was sorted into two fractions: opened fabric (comprising fibres and yarns) and non-opened fabric (comprising pieces of fabric). These fractions were weighed to determine the fabric defibration efficiency. About one-quarter of the opened fabric fraction was retained to evaluate the quality of the shredded material by measuring fibre length and testing the tensile strength of the yarns produced from these fibres. The remaining textile output from the first cycle was fed into the machine for a second shredding cycle, and this process was repeated for a third cycle. In total, 12 samples of shredded material were obtained (three shredding cycles for each group).

2.2.2 Fibre length analysis of the recovered fibres

Approximately 20 g of each of the samples of the fraction of opened fabric (12 samples in total, 4 group conditions with 3 cycles for each condition as mentioned before) were fed into the MDTA testing machine (MDTA 4 Automatic Fibre-Length, Impurity, and Spinnability Tester) to analyse the length distribution of the fibres. A feeder speed of 200 mm/min and an opener speed of 7,000 rpm (OB20 type) were used. The number of fibres analysed was 5,000.

2.2.3 Spinning yarn from the recovered fibres

To test the feasibility of producing new yarns with the recycled fibres and to assess the properties of the yarns produced, approximately 5 g of the fraction of opened fabric were passed through a USTER MDTA 3 machine to form slivers. Then, these slivers were used to produce OE-rotor spun yarns. The OE-rotor spinning machine settings are shown in Table 2.

OE-rotor spinning machine settings

| Yarn linear density (tex) | 80 |

| Yarn twist (1/m) | 601 |

| Metric twist coefficient | 170 |

| Draft | Depending on the silver count |

| Rotor speed (1/min) | 20.000 |

| Rotor type | T256D |

| Opening roller speed (1/min) | 8,000 |

| Opening roller type | OB20 |

| Nozzle | KN4 |

| TorqueStop | White |

2.2.4 Yarn tensile test

The breaking force, tenacity, and elongation of the yarns produced from 100% recycled fibres were measured using a tensile tester (Automatic Tensile Tester for Yarns Textechno STATIMAT ME+) following UNE-EN ISO 2062:2010 (method B) [9]. The tensile tester settings were a load cell of 10 N, a clamp distance of 500 mm, a test speed of 500 mm/min, and a pre-load of 0.5 cN/tex. The yarn count was determined following UNE-EN ISO 2060-1 by weighing 20 m of yarn.

2.2.5 Applying lubricant

To analyse the effect of the application of lubricant, the fabrics were coated with a solution containing 5.8 g/L oil and 2.1 g/L surfactant before shredding. The cut fabric was sprayed with a high-pressure water gun, coating it with 0.5, 1, and 1.5 wt% oil solution over fibre weight. After spraying, the fabrics were introduced into a mixing machine to combine them with the solution for 1 h. They were then dried at room conditions for 24 h. The fabrics were also sprayed with only water for comparative purposes (sample named “water”).

Subsequently, the coated fabric was shredded using the optimized conditions determined with the first study and tested in a similar way as described in Sections 2.2.2., 2.2.3, and 2.2.4.

2.2.6 Statistical analysis

A Tukey test for analysis of variance was performed with SPSS software to statistically examine the results, thereby obtaining the significance groups. A significance level of 0.05 was applied.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Effect of shredding passes on the quality of the recycled fibres and yarns

Table 3 shows the weight distribution of opened fabric, non-opened fabric, and trash obtained after shredding according to the different conditions described in Section 2.2.1.

Weight percentage distribution of opened fabric, non-opened fabric, and trash after shredding

| Type | Group 1 (%) | Group 2 (%) | Group 3 (%) | Group 4 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Opened fabric | 89.8 | 81.2 | 89.0 | 80.0 |

| Non-opened fabric | 5.1 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 0.4 | |

| Trash | 5.1 | 18.4 | 6.1 | 19.6 | |

| Cycle 2 | Opened fabric | 95.1 | 95.9 | 97.1 | 95.4 |

| Non-opened fabric | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | |

| Trash | 2.4 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 4.6 | |

| Cycle 3 | Opened fabric | 99.4 | 99.2 | 99.0 | 98.9 |

| Non-opened fabric | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |

| Trash | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 |

As can be seen in the table, for all the groups, the content of opened fabric increases with opening cycles. Each cycle helps to defibrate the fabrics that remain non-opened. By feeding a mixture with less content of non-opened fabric (as happens in the second and third cycles), the opening cylinder can work, generating less trash.

With a single opening cycle, Groups 1 and 3 (the ones with lower opening cylinder speed) are the most efficient for obtaining higher content of opened fabrics, less non-opened fabrics, and trash content. This result indicates that the intensity of the defibration is a key factor in terms of generated trash and efficiency. It is to say that it is more efficient to work with low opening speeds.

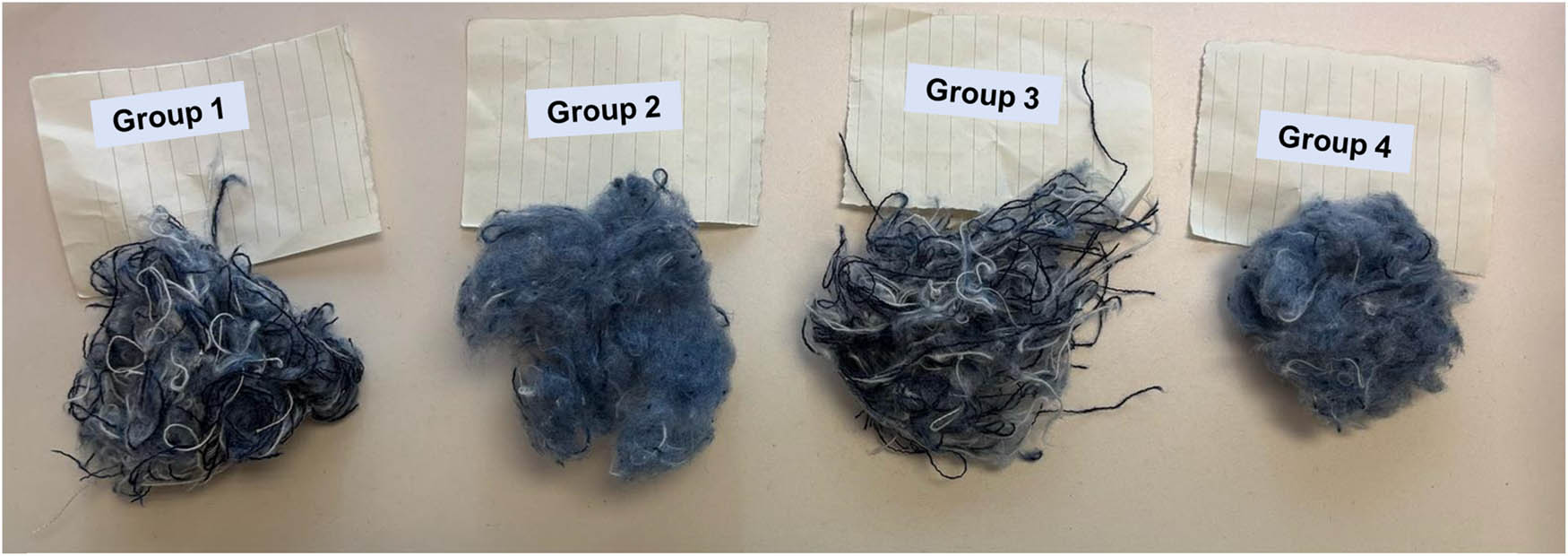

The images of the opened fabric fraction obtained from the first cycle for each of the groups are shown in Figure 4.

Opened fabric fraction obtained in the first cycle of shredding.

As shown in Figure 4, the yarn content in Groups 2 and 4 is significantly lower than in Groups 1 and 3. However, this does not imply that the fibres in these groups are of better quality; rather, the shredded material from Groups 1 and 3 requires further opening actions to individualize the fibres.

With a second opening cycle, the conditions in Group 3 (higher feeding speed and lower opening cylinder speed) result in a higher content of opened fabrics, a very low content of non-opened fabrics, and the lowest content of trash. Therefore, with lower disaggregation intensity, it is possible to achieve higher efficiency.

Finally, for the third opening cycle, the content of opened fabric, non-open fabric, and trash is very similar for all the conditions studied. The efficiency of the process is stabilized at maximum regardless of the conditions used. Therefore, using high speeds leads to an efficiency similar to using three cycles. This suggests that the conditions in Group 4 are more efficient for shredding in terms of both productivity and effectiveness.

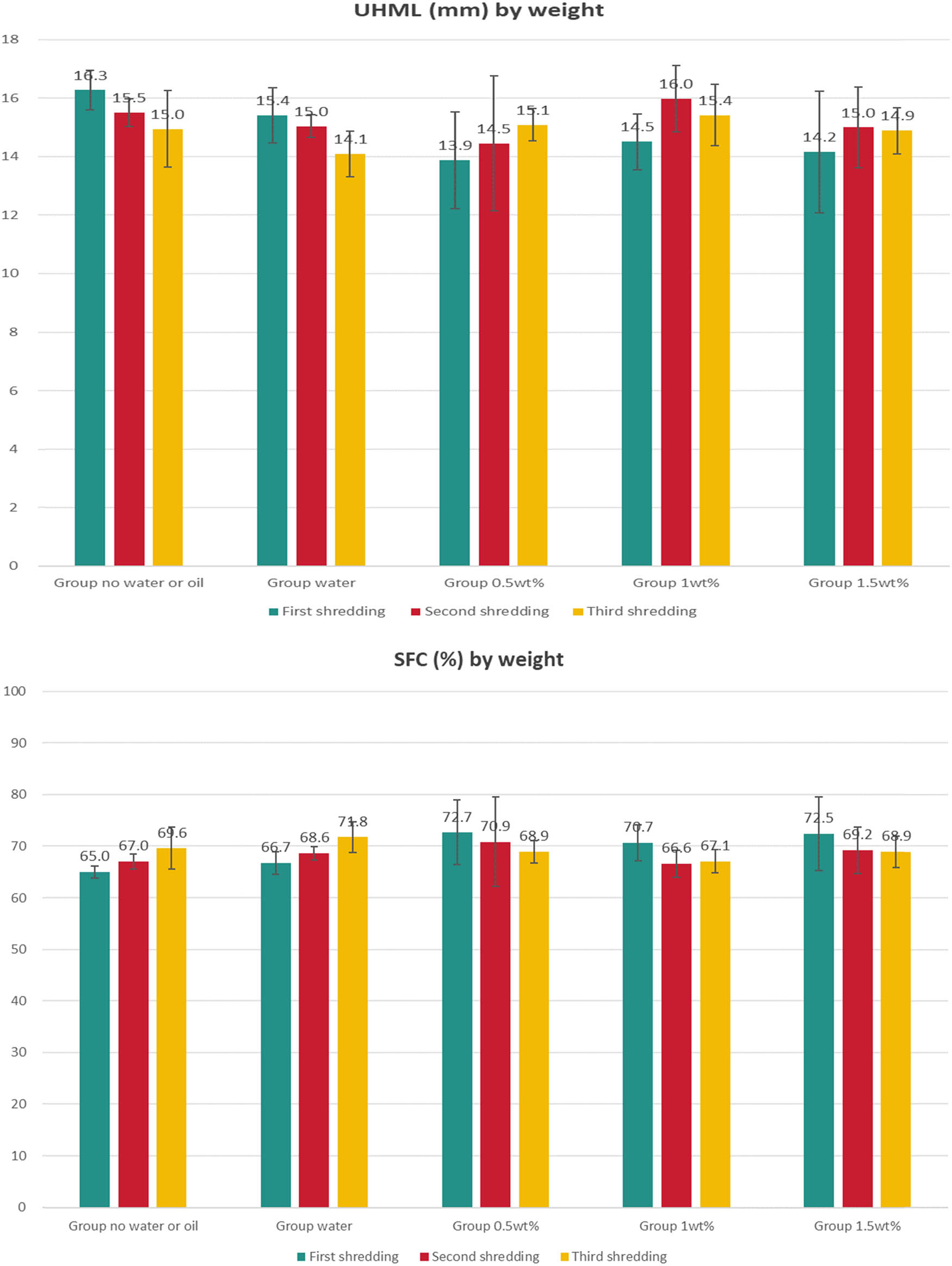

As for the length of the recovered fibres from each shredding cycle, the upper half mean length (UHML) and short fibre content (SFC) by both weight and fibre number are presented in Figures 5 and 6, respectively.

Results of UHML (top) and SFC (bottom) of the recovered fibres by weight.

Results of UHML (top) and SFC (bottom) of the recovered fibres by number.

In Figures 4 and 5, it can be seen that the fibres from Groups 2 and 4 (higher opening speed) are longer than those in Groups 1 and 3. The SFC is also lower both by weight and by number. This effect could be attributable to the effect of the fluid dynamics generated by the geometry of the card clothing as well as its interaction with the material to be defibrated.

As a general trend, it can be observed that the conditions of Groups 2 and 4 led to slightly higher UHML and less SFC, indicating higher shredding efficiency and better quality of recovered fibres in these groups. On the contrary, there is a general tendency for fibre length to be reduced with the number of cycles in agreement with previous works [3]. Similarly, a general tendency of increasing SFC with the number of cycles is observed, being more noticeable in Groups 1, 3, and 4 and when measured by weight. This effect is justified by the aggressiveness of the opening process associated with cycles performed in excess. Nonetheless, despite the observed tendency, it should be noted that the results were not significant based on the Tukey test’s analysis.

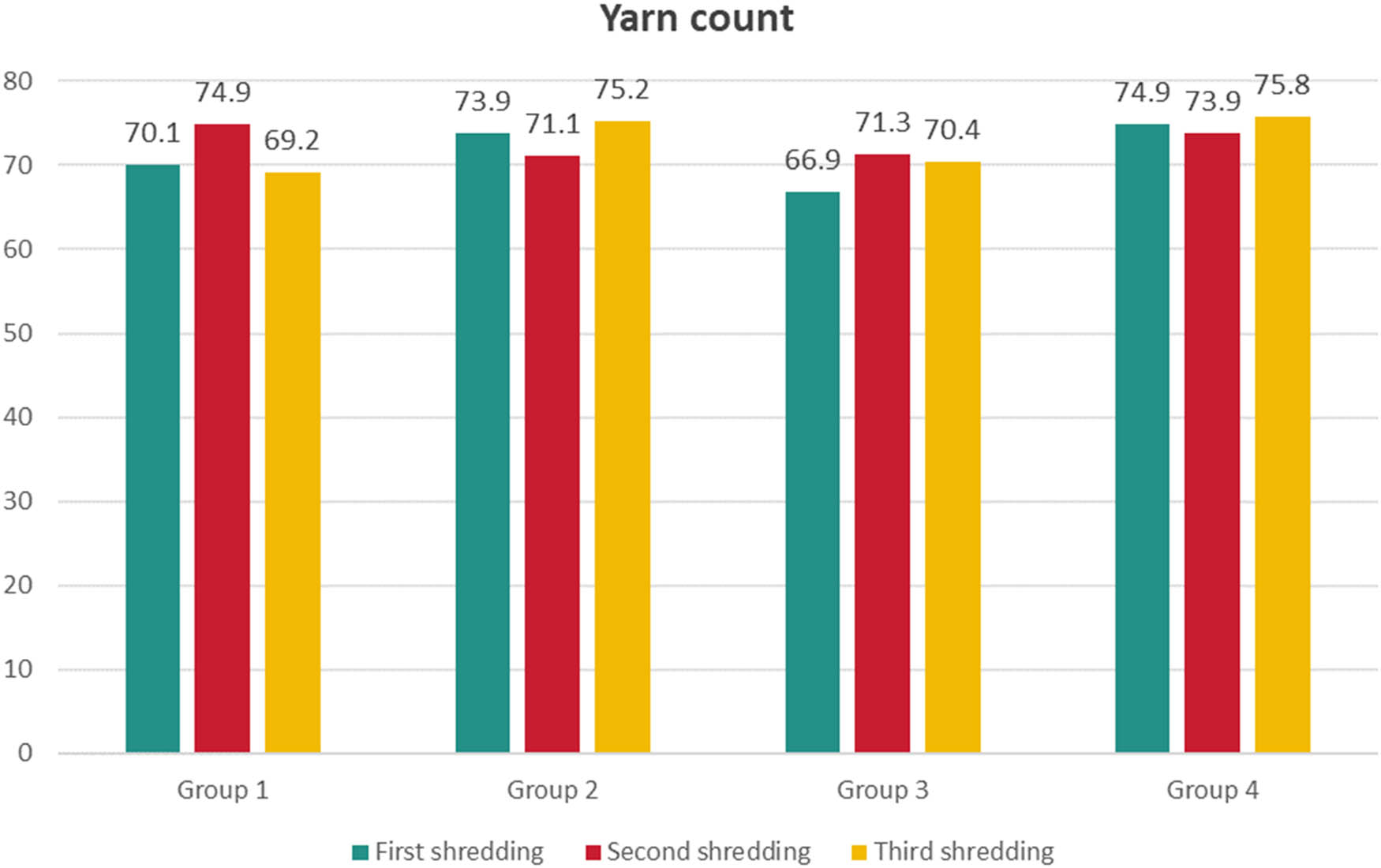

As explained above, with the recovered fibres, open-end rotor spun yarns were produced in the same conditions, adjusting the feeding speed according to the sliver weight to obtain an 80 tex theoretical yarn count. This will allow us to indirectly analyse the quality of the recovered fibres. In all cases, it was possible to prepare 100% recycled yarns from these fibres. The yarn count values of the produced yarns are shown in Figure 7. As can be seen, there is great variability in counts due to material losses in the opener roller of the OE-rotor machine.

Yarn count of the produced yarns with recycled fibres.

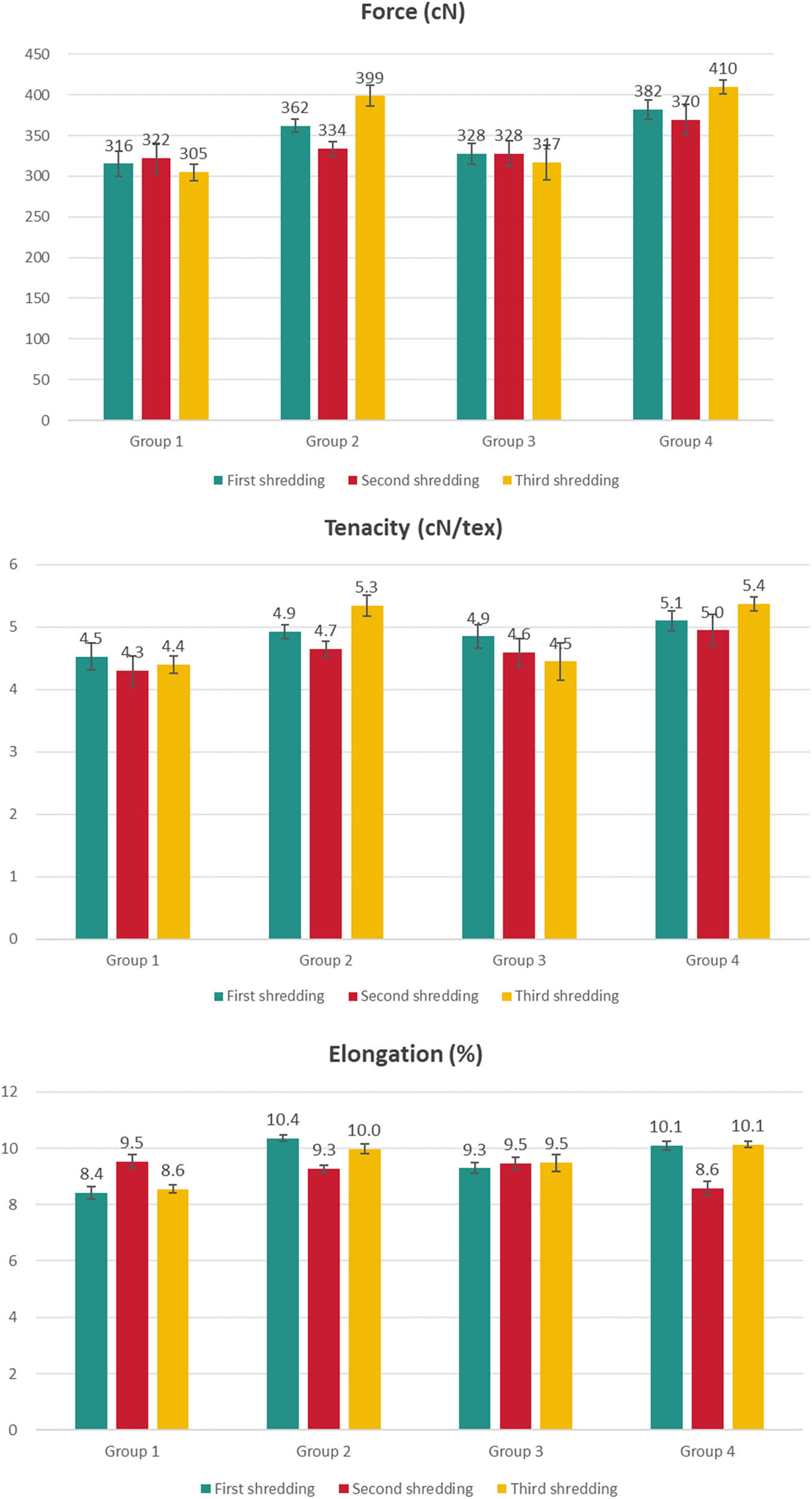

The results of the average maximum force and tenacity obtained from the tensile tests are presented in Figure 8.

Results of breaking force (top), yarn tenacity (middle), and elongation of the yarns (bottom) produced with the recycled fibres.

The maximum force and tenacity of the yarns range from ∼316 to 410 cN and ∼4.3 to 5.4 cN/tex, respectively. In general, the yarn strength of the samples from Groups 2 and 4 was higher than the ones from Groups 1 and 3. The statistical analysis showed that these differences are significant (Table 4). This effect can be justified by the presence of longer fibres produced by a more efficient defibration of the fabrics. Although no significant differences were seen in the length trend, it is confirmed here that Groups 2 and 4 produce higher quality yarns.

Variance analysis results for yarn force and tenacity

| Force | Tenacity | |

|---|---|---|

| Group type | 0.013a | 0.014a |

| Shredding times | 0.452 | 0.252 |

aStatistically significant (<0.05).

On the contrary, concerning the effect of the number of shredding cycles, in Groups 2 and 4, the yarns produced from the samples with three opening cycles led to the highest breaking forces. The opposite effect was observed for the samples prepared with conditions 1 and 3 (the ones with lower opening cylinder speed). This effect, although not statistically significant (Table 4), can be justified by the greater individualization of fibres despite the loss of length due to the action of additional opening cycles.

Taking into account the aforementioned results, we used the parameters of Group 4 to evaluate the effect of the application of lubricant on the quality of the recycled fibres and yarns.

3.2 Effect of the application of lubricant on the quality of the recycled fibres and yarns

To analyse the effect of oiling the fabrics on shredding efficiency, Group 4 conditions were used to defibrate fabrics previously coated with an oil content of 0.5, 1, and 1.5 wt%. As mentioned in the experimental section, a sample spraying only water was as well prepared as a reference.

The weight distribution of opened fabric, non-opened fabric, and trash based on the application of lubricant before shredding is shown in Table 5.

Weight percentage distribution of opened fabric, non-opened fabric, and trash after shredding the samples sprayed with oil wt% 0.5, 1, and 1.5 and only water

| Type | Water | 0.5 wt% | 1 wt% | 1.5 wt% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Opened fabric | 81.6% | 85.4% | 76.6% | 76.5% |

| Non-opened fabric | 2.8% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 3.1% | |

| Trash | 15.6% | 14.1% | 22.3% | 20.4% | |

| Cycle 2 | Opened fabric | 96.4% | 95.3% | 95.6% | 96.4% |

| Non-opened fabric | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Trash | 3.6% | 4.7% | 4.4% | 3.6% | |

| Cycle 3 | Opened fabric | 99.3% | 99.0% | 98.8% | 98.9% |

| Non-opened fabric | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Trash | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 1.1% |

As observed in the previous study on the effect of feeding and opening speed (Table 3), increasing the number of cycles results in a higher fraction of opened fabric and less non-opened fabric and trash content. With a single opening cycle, 0.5 wt% oil lubricant yielded the best results in terms of fabric opening percentage, non-opened fabric, and trash content. This finding supports the optimal lubricant dose. Excess lubricant, as known, increases the coefficient of friction, leading to a loss in performance. However, after three opening cycles, the content of opened fibres, non-opened fabric, and trash is very similar across samples, regardless of whether lubricant is used or its amount. This is because three cycles achieve full opening of the textile, irrespective of the conditions applied.

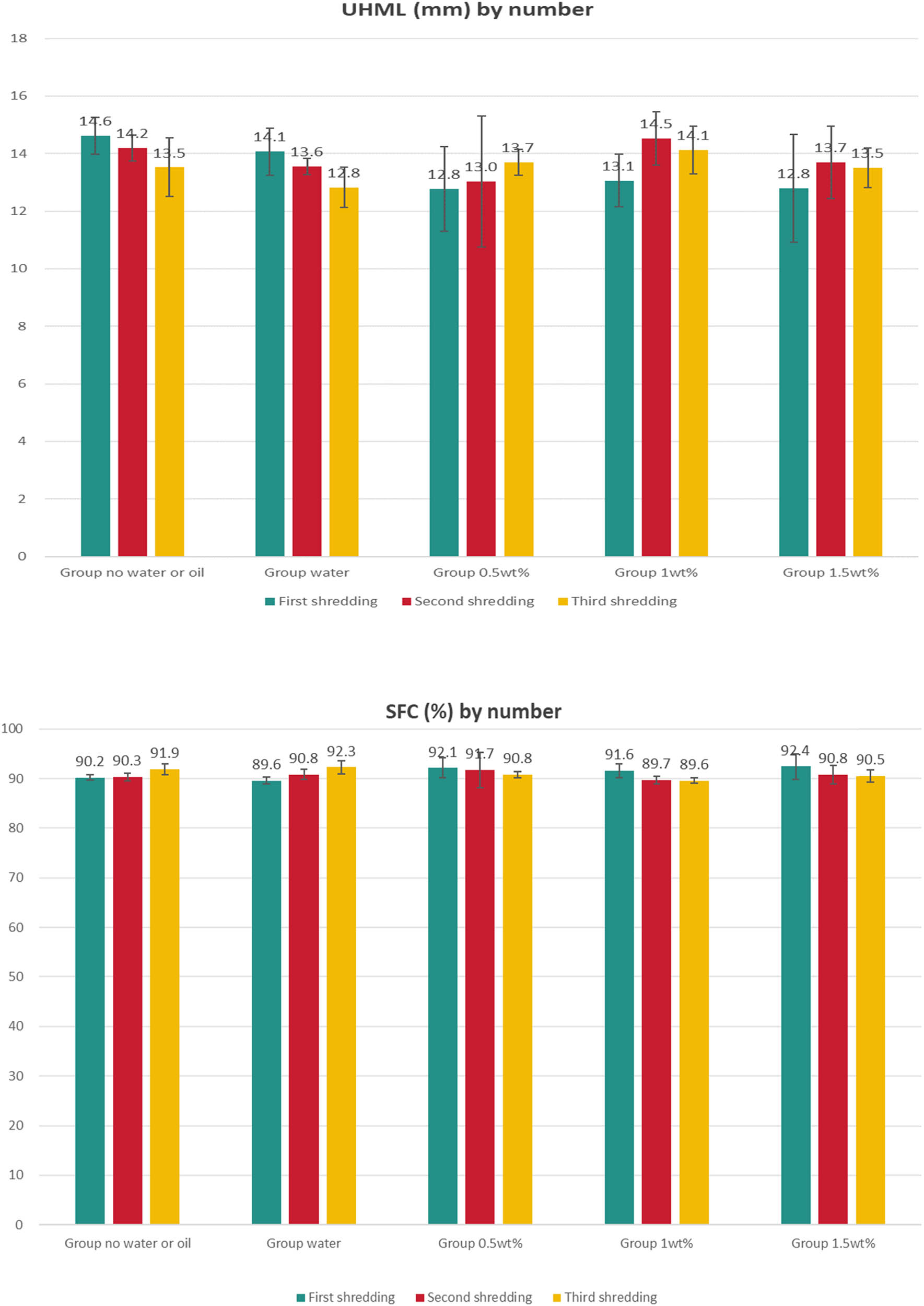

The values of length (UHML) and SFC test results are shown in Figure 9 (results by weight) and Figure 10 (results by number).

Results of UHML (top) and SFC (bottom) for recovered fibres by number.

Results of UHML (top) and SFC (bottom) for recovered fibres by number.

As shown in Figures 9 and 10, without oil addition, the quality of recycled fibres, in terms of length, decreased with each shredding cycle. In contrast, applying lubrication before shredding improved the quality of recycled fibres with each cycle. This improvement could be likely due to the formation of a protective film on and within the fibres, reducing fibre interaction and the likelihood of breaking into short fibres. During subsequent shredding cycles, short fibres produced in previous cycles are lost along with non-shreddable trash. The remaining fibres, protected by the lubricant, are less likely to break into short fibres. Nonetheless, these conclusions are a hypothesis since the Tukey test did not reveal significant differences between the samples analysed.

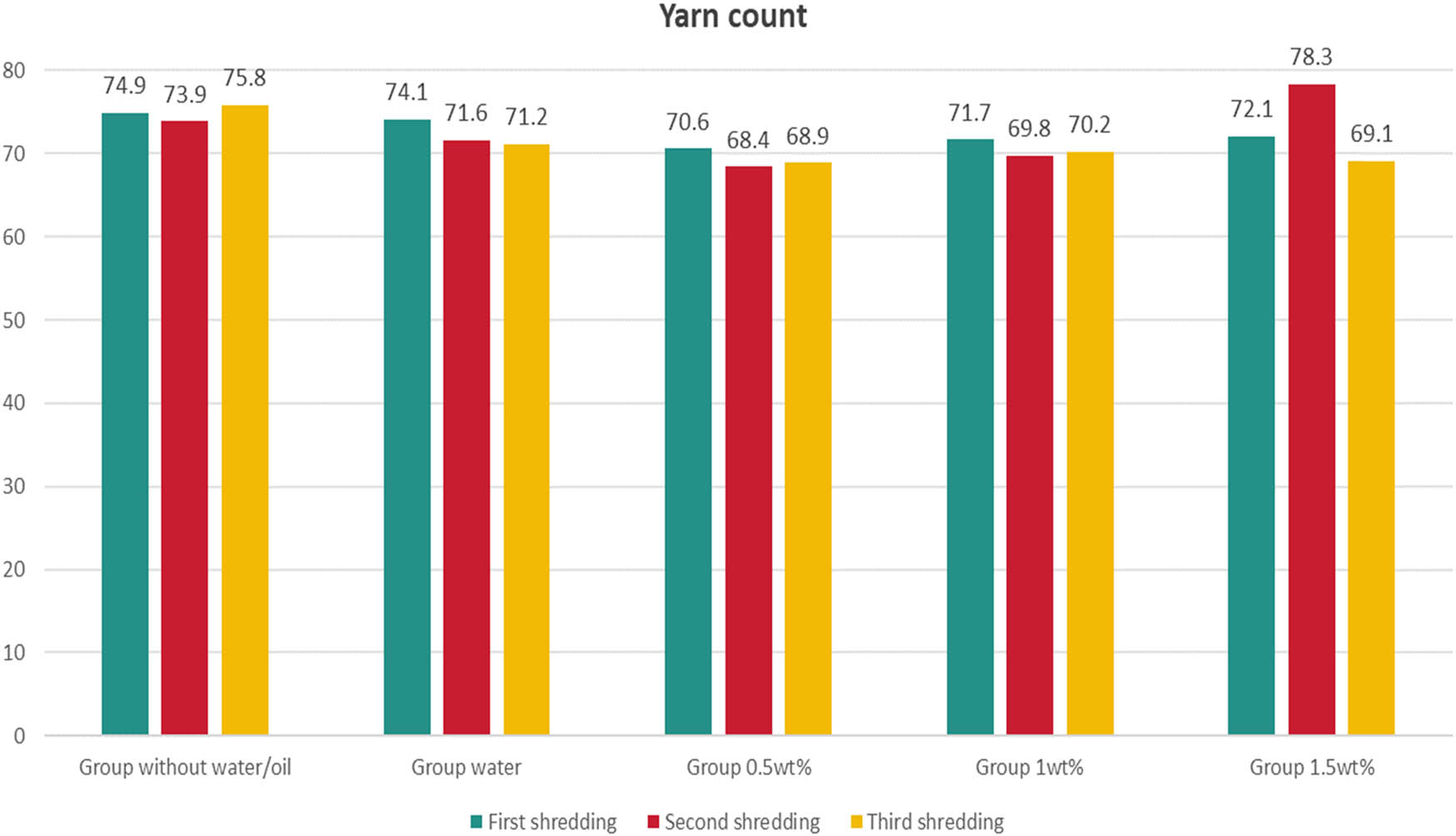

In a similar way to the first study, the recovered fibres were spun into open-end rotor yarns, and tensile tests were performed to determine their mechanical performance. The yarn count of the produced yarns is shown in Figure 11. As can be seen, except for the yarn with a count of 78.3, the rest of the yarns have similar values.

Yarn count of the produced yarns.

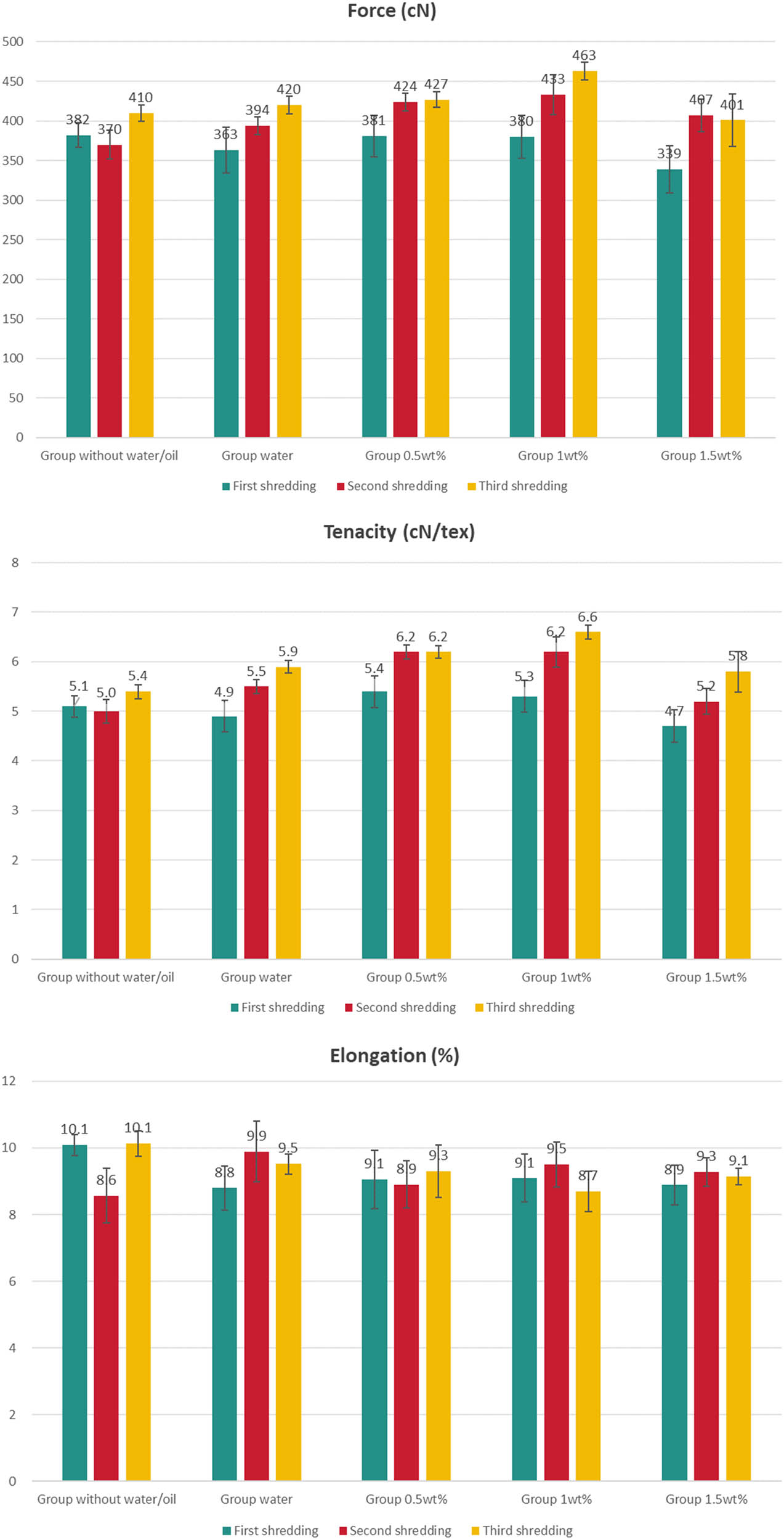

The results of the tensile test are presented in Figure 12.

Results of breaking force (top), yarn tenacity (middle), and elongation of the yarns (bottom) produced with the recycled fibres.

Unlike that observed for the uncoated fabrics, the mechanical performance of the recycled yarns increased with the number of shredding cycles (groups of water or oil 0.5, 1, and 1.5 wt%). The yarn with the best quality in terms of mechanical performance was obtained when shredding three times and applying 1 wt% oil before shredding. According to the Tukey test, these results are statistically significant (Table 6). This means that, although we could not find significant differences in the quality of the fibres by the lubricant addition, it had a positive effect on the quality of the yarns.

Variance analysis results of the yarn force and tenacity

| p | Force | Tenacity |

|---|---|---|

| Group type | 0.015a | 0.002a |

| Shredding times | 0.001a | 0.001a |

aStatistically significant (<0.05).

4 Conclusions

In this experimental work, we examined the effects of shredding machine settings, the number of shredding cycles, and the pre-shredding lubrication effect on the mechanical recycling efficiency of denim fabrics. The main conclusions of the research are detailed as follows:

100% mechanically recycled fibres from denim may be re-spun in lab conditions into rotor yarns without breakage during the spinning process.

A feed speed of 0.3 m/min and an opening speed of 947 rpm is the optimal setting for a three-cycle shredding with the machine used for this experiment. The higher the setting of the feed and opening speed, the more efficient the recycling in the process studied. Under these conditions, a very high efficiency of the opening of the material was produced, which allowed the production of yarns with the best dynamometric properties. It is clear that the fibre length and the SFC were not optimal under these conditions; however, the high individualization of the material seems to be more important in this case.

Although the quality of the fibres was not improved compared to those without oil addition, it had a positive effect on the quality of the recycled yarns.

The yarn with the best quality in terms of mechanical performance was obtained when shredding three cycles and applying 1 wt% oil before shredding.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Spanish government’s Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), and the European Union’s “NextGenerationEU”/PRTR for the financial support received under the scope of the RECYWASTEX (TED2021-130611B-I00) project (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). They also wish to acknowledge the funding provided by the research group TECTEX (2021 SGR 01056) of the Department of Research and Universities of the Generalitat de Catalunya.

-

Funding information: The Article Processing Charges were funded by the research group TECTEX (2021 SGR 01056) of the Department of Research and Universities of the Generalitat de Catalunya. The experimental research was funded by the Spanish government’s MCIN, AEI and the European Union’s “NextGenerationEU”/PRTR for the financial support received under the scope of the RECYWASTEX (TED2021-130611B-I00) project (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

-

Author contributions: Liu Zewen: writing – original draft, methodology, Investigation, formal analysis, data curation. Francesc Cano: writing – review and editing, supervision, methodology, investigation, conceptualization. Monica Ardanuy: writing – review and editing, supervision, resources, project administration, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition, conceptualization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability statement: Data are available from the authors upon request.

References

[1] Sheng, S., Jinming, D., Mei, N., Zhifeng, C., Wensheng, H. (2011). Renewability of waste textiles. Textile Journal, 32(11), 147–152.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Aronsson, J., Persson, A. (2020). Tearing of post-consumer cotton T-shirts and jeans of varying degree of wear. Journal of Engineered Fibres and Fabrics, 15, 1558925020901322.10.1177/1558925020901322Search in Google Scholar

[3] Ütebay, B., Çelik, P., Çay, A. (2019). Effects of cotton textile waste properties on recycled fibre quality. Journal of Cleaner Production, 222, 29–35.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.033Search in Google Scholar

[4] Lindström, K., van der Holst, F., Berglin, L., Persson, A., Kadi, N. (2024). Mechanical textile recycling efficiency: Sample configuration, treatment effects and fibre opening assessment. Results in Engineering, 24, 103252. 10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103252.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Gupta, B. S. (2008). Textile fibre morphology, structure and properties in relation to friction. In Friction in textile materials (pp. 3–36). Woodhead Publishing, United Kingdom.10.1533/9781845694722.1.3Search in Google Scholar

[6] Taohai, Y., Hefang, M. (2013). Review on recycling and reusing of waste textiles. Light Textile Industry and Technology, 6, 73–75. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-0101.2013.06.028.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Lindström, K., Sjöblom, T., Persson, A., Kadi, N. (2020). Improving mechanical textile recycling by lubricant pre-treatment to mitigate length loss of fibres. Sustainability, 12(20), 8706.10.3390/su12208706Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zheng J, Mostofa A, Saha P. (2021). A comparative study of recyclability between cotton and polyester yarn via inter-fibre frictional force and elongation at break investigation. American Journal of Engineering, 12, 1–16.Search in Google Scholar

[9] UNE-EN ISO 2062-2010. (2010). Textiles – Yarns from Packages – Determination of Single-end Breaking Force and Elongation at Break Using Constant Rate of Extension; Method B, UNE-EN ISO, Madrid, Spain.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method