Abstract

To investigate the influence of materials on the surface morphology and compressive performance of honeycomb structural components prepared by stereo lithography apparatus (SLA) technology, three typical materials, namely Dutch State Mines (DSM) 8000, Somos® Taurus, and FS 3400GF (Glass Bead Filled Nylon Powder), were selected as raw materials for printing honeycomb structure via SLA. FS 3400GF can withstand a maximum compression force of 14.1 kN in vertical compression, while it is 10.1 kN for DSM 8000 and 5.8 kN for Somos® Taurus, indicating that FS 3400GF bears significantly higher vertical pressure. The maximum force bore by FS 3400GF under lateral compression is 0.47 kN, DSM 8000 is 0.56 kN, and Somos® Taurus is 0.17 kN, suggesting that the lateral compression failure is highly likely to occur. The mechanical compression failure reveals the physical properties of honeycomb structures and provides an experimental support for expanding the potential functional application of honeycomb structures in additive manufacturing.

1 Introduction

Stereolithography is a technique for layer-by-layer structure fabrication, where a laser beam is focused to a free surface of a photosensitive liquid to induce polymerization in certain region and transform to be a polymerized solid. Stereo lithography apparatus (SLA) technology is one of the advanced processes for additive manufacturing applied in the aerospace industry [1], which explores different types of resin materials as the molding material, and mostly are the liquid photosensitive resin or photoinitiated liquid material via polymerization, cross-linking and curing to form the final solid part [2]. SLA has the advantages of short production cycle, high degree of freedom in shape formation, and high forming accuracy compared to traditional manufacturing technologies [3,4]. Two photo polymerizations can directly print nanoscale structures with much higher accuracy than other types of additive manufacturing processes and meets most of the part forming accuracy requirements as well [5,6].

Liquid photosensitive resins are generally the uniformed liquid mixtures of the repolymerized monomers, crosslinking agents, and photo-initiators in varied proportions [7]. Principally, once the photosensitive resin is upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation with a certain wavelength and intensity, such UV irradiation generates free radicals in the resin via breaking the chemical bonds of photo-initiator and then to form new bonds between material molecules such as prepolymerized monomers and crosslinking agents, thereby achieving the certain degree of crosslinking and solidification of liquid photosensitive resin into solid polymer [8,9]. Quite improvements have been developed from early free radical photosensitive resins to current cationic photosensitive resins, which are characterized by fast polymerization rates [10]. Recently, various hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and fluorescent polymer chains have successfully grafted onto the surface of the object through reversible addition fracture chain transfer polymerization using post coating surface modification of mercaptoacrylate polymers [11], and as such can effectively control the polymerization depth of the cured polymer layer. In addition, some unique photosensitive resins with high temperature resistance, good mechanical properties, and good biocompatibility [12–14] have demonstrated further possible potential structure formation applications via SLA technique.

Honeycomb structure possesses not only a beautiful structure and symmetrical shape, but also exhibits outstanding characteristics of high specific strength and high specific stiffness. It can withstand large forces with less amount of materials like up to about 70–90% lighter [15,16]. Traditional production methods include extrusion and composite methods. The extrusion method is suitable for the manufacturing of small honeycomb structures, while the composite method can achieve optimization of various properties [17]. Currently, further enhancement on the physical properties of honeycomb structural components has been draw much attention in composite materials. It was reported that the high stiffness honeycomb structure with addition of granular particles can effectively suppress more noise and vibration [18], and the implantation of honeycomb structure has a significant influence on the impact damage degree and energy dissipation mechanism of the original foam core sandwich composite [19].

However, due to the inherited complexity and variability of honeycomb structures, which are not easily processed using traditional processes, some researchers have gone over to the three-dimensional (3D) printing technology to prepare honeycomb structures. For instance, Ingrole et al. [20] conducted 3D printing on traditional honeycomb structures and concave honeycomb ones, and emphasized on the in-plane compressive strength, energy absorption capacity, and failure mode of the structures, which turned out that the compressive strength of concave honeycomb structures was 160% higher than that of traditional honeycomb ones, and 20% higher in the energy absorption as well. Meanwhile, different shapes of honeycomb structures, including triangular, quadrilateral, and hexagonal bidirectional hierarchical, have been achieved by using machine learning modeling and selective laser melting technology [21–23], and both of the compression experiments and the establishment of finite element models have verified the effects of several factors on energy absorption ascribed to the structure design, such as bidirectional hierarchical factors, material strength, wall panel thickness, and aspect ratio [24]. From the above examples, we found that using SLA 3D printing technology to design and manufacture honeycomb structure specimens with different Poisson’s ratios, including honeycomb, square honeycomb, quasi square honeycomb, and concave honeycomb structures. However, there is little research on the comparison of the transverse and longitudinal mechanical properties of honeycomb and the mechanical failure mechanism.

In this article, to investigate the influence of materials on the surface morphology and compressive performance of honeycomb structural components prepared by SLA technology, three types of photosensitive resins, namely photosensitive Resin Dutch State Mines (DSM) 8000, photosensitive Resin Somos® Taurus, and Nylon FS 3400GF (Glass Bead Filled Nylon Powder), were selected as experimental materials for preparing honeycomb structures with same dimension and size by using SLA technology. Comparative experiments were conducted on the microstructure, surface roughness, and compressive performance of the three types of honeycomb structure samples. This study can reveal the physical performance laws of honeycomb structures manufactured with additives, providing experimental support for the functional application of honeycomb structures manufactured with additives.

2 Materials and experiments

2.1 Materials

Three raw materials were used in the experiment, with the trade names being photosensitive Resin DSM 8000, photosensitive Resin Somos® Taurus, and Nylon FS 3400GF. Photosensitive Resin DSM 8000 has stable viscosity, efficient molding, excellent detail resolution, and high durability. This material is particularly suitable for functional prototypes, conceptual models, and small batch production components, which have durability and moisture resistance [25]. Photosensitive Resin Somos® Taurus is an extremely tough and high-temperature resistant three-dimensional photocurable printing material, combined with excellent durability and black appearance, making it a versatile prototype and final product application. In Nylon FS 3400GF, glass microspheres account for 40%. Nylon is composed of glass microspheres, which have high stiffness, low relative density, high thermal deformation temperature, and excellent strength and hardness. It is suitable for products with high strength requirements, as well as parts that require their own weight, aerospace parts, and pneumatic components in automotive sports applications. The physical properties of the three raw materials are shown in Table 1.

| Trade name | DSM 8000 | Somos® Taurus | FS 3400GF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product color | White | Black | Gray |

| Product density (g/cm3) | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.26 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 37 | 46.9 | 44 |

| Tensile modulus (MPa) | 2,510 | 2,310 | 3,500–7,800 |

| Bending strength (MPa) | 67.3 | 73.8 | 68 |

| Bending modulus (MPa) | 2,200 | 2,054 | 2,415 |

| Elongation at break (%) | 7.5 | 5.7 | 5 |

| Microhardness | 5.6 | 1.6 | 6.8 |

2.2 Preparation of honeycomb structural components

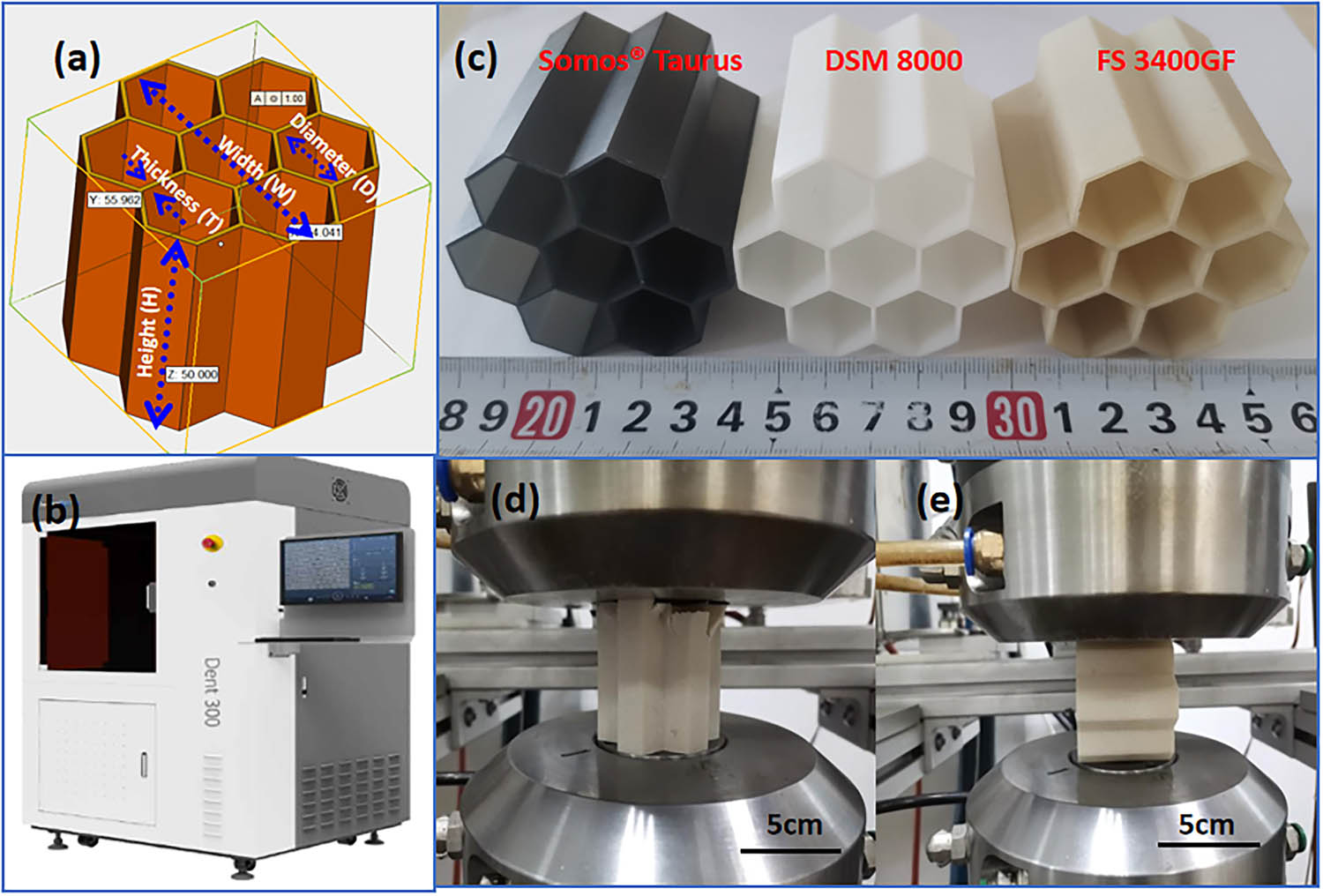

The 3D printing of honeycomb structural components as designed in Figure 1(a) adopts the D300 SLA printing equipment produced by Shanghai UnionTech Technology Co., Ltd, as shown in Figure 1(b), with a molding size of 300 × 300 × 100 mm3 and an accuracy of 50–100 µm. The laser is a solid-state triple frequency Nd:YVO4 running at a typical scanning speed of 6–10 m/s, and UnionTech RSCON operating software, rated power 2.6 kVA. The forming process is mainly divided into three stages: preparation before printing, printing forming stage, and post processing stage. First, prepare the model and design a 3D model of honeycomb structural components by using 3D CAD software as shown in Figure 1(a). Second, during the printing and forming stage, set the printing parameters that meet the requirements of the part forming. The printing size parameters for the three materials are listed in Table 2, and the part prototype is printed. Then, rinse with industrial alcohol at a concentration of over 95% and perform post-curing treatment to obtain a three-dimensional honeycomb structural component, as shown in Figure 1(c). After printing, measure the size of the actual component as shown in Table 2.

Printing honeycomb structural components: (a) 3D data model, (b) D300 SLA printing equipment, (c) as-made honeycomb structural components of three materials, (d) vertical compression, and (e) transverse compression.

Dimensions of honeycomb structural components

| Parameters | DSM 8000 | Somos® Taurus | FS 3400GF | Design dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (mm) | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.18 | 1.00 |

| H (mm) | 50.10 | 50.50 | 49.92 | 50.00 |

| W (mm) | 55.90 | 55.70 | 55.92 | 55.00 |

| D (mm) | 17.16 | 17.28 | 17.04 | 17.00 |

| Weight (g) | 18.37 | 16.79 | 20.36 | — |

Note: The dimensional parameters marked as T, H, W, and R, refer to Figure 1(a).

2.3 Testing and characterization

The Hitachi S3400N scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to observe the micro-surface morphology, and a multifunctional fast rotating confocal microscope Smartproof 5 (ZEISS, Germany) was used for surface analysis to measure the surface roughness values of 3D printed structural parts. The surface analysis was carried out at the following conditions, such as a wavelength of 405 nm, a resolution of 120 nm, 20 nm for Z-axis minimum step accuracy, up to 5 mm for the height scanning range, with the objective lens of 2.5× ∼50×, and the stage dimension of 150 mm × 150 mm super large stroke. The compression experiments were conducted via Material Test System testing machine on the sample in both horizontal and vertical directions with a maximum load of 100 kN and a speed of 1 mm/min. During the mechanical test, Figure 1(d) represents vertical compression and Figure 1(e) represents transverse compression. In addition, a digital microhardness tester was used for surface mechanical performance analysis with a loading force of 10 gf and a holding time of 10 s.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Surface morphology analysis

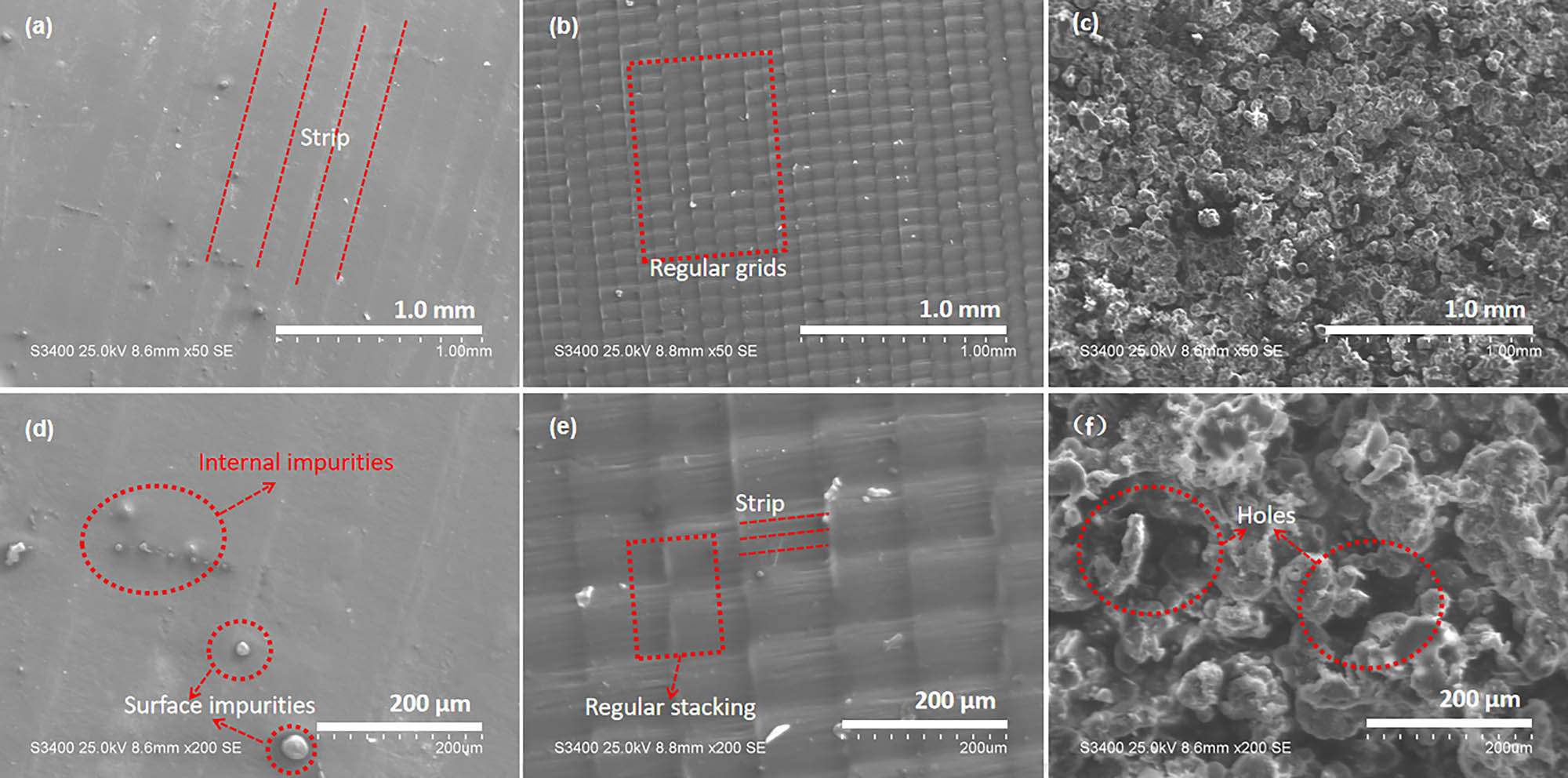

SEM was used to observe the micro-surface morphology of the formed honeycomb structure samples as demonstrated in Figure 2, and it was found that the surface morphology on the honeycomb structures made of the three materials had their own unique characteristics, which is possible due to the nature of each one’s response to the light irradiation. Among them, the white surface of DSM 8000 is smooth, and it also exhibits obvious distribution of oriented bands or ridges at a regular interval as depicted by the red dashed line in Figure 2(a), which is closely related to the color of the material. UV light shining on the surface of the white prepolymerized monomer will generate reflection [29] triggering a chain reaction of similar photo-initiators. And the black surface of Somos® Taurus exhibits a uniform and regular lattice shape as the red box in Figure 2b, where UV light on the surface of the black prepolymerized monomer is fully absorbed with little energy leakage [30]. Therefore, the lattice size on the surface of this material is most likely to be determined by the size of the illuminated spot. Unlike the two as mentioned above, there are irregularly shaped microspheres on the surface of the structural components made of FS 3400GF, and that coarse surface could be ascribed to content of containing 40% glass microspheres in this material, which could be due to gap in the melting points of glass microspheres and nylon causing noticeable cooling shrinkage difference between the two ingredients from liquid mixture to solid status. Such observations remind of paying attention on some critical parameter in possible materials with different formulas using SLA technique, e.g., thermal property differences.

Surface SEM images of three types of honeycomb structural components magnified by 50 times of (a) DSM 8000, (b) Somos® Taurus, and (c) FS 3400GF; magnified by 200 times of (d) DSM 8000, (e) Somos® Taurus, and (f) FS 3400GF.

Furthermore, it can be observed in Figure 2(d) that the surface of material DSM 8000 at a magnification of 200× contains granular impurities with different sizes, which might be because of some impurities in the raw materials. Some solid particles stand out on the surface of the component, while others stay underneath the surface and inside the component. While the detailed surface morphology in microscale as demonstrated in both Figure 2(e) and (f) state otherwise significantly. In Figure 2(e), it can be observed that the grids are stacked together in a regular manner, and bands appear within each grid unit, which is caused by the equidistant grating generated by UV light passing through the laser crystal. In Figure 2(f), it can be observed that holes have appeared inside and on the surface of the structural component, which is due to some of the light being blocked or refracted by glass microspheres during UV irradiation, resulting in uneven energy gain from the initiator.

3.2 Surface roughness analysis

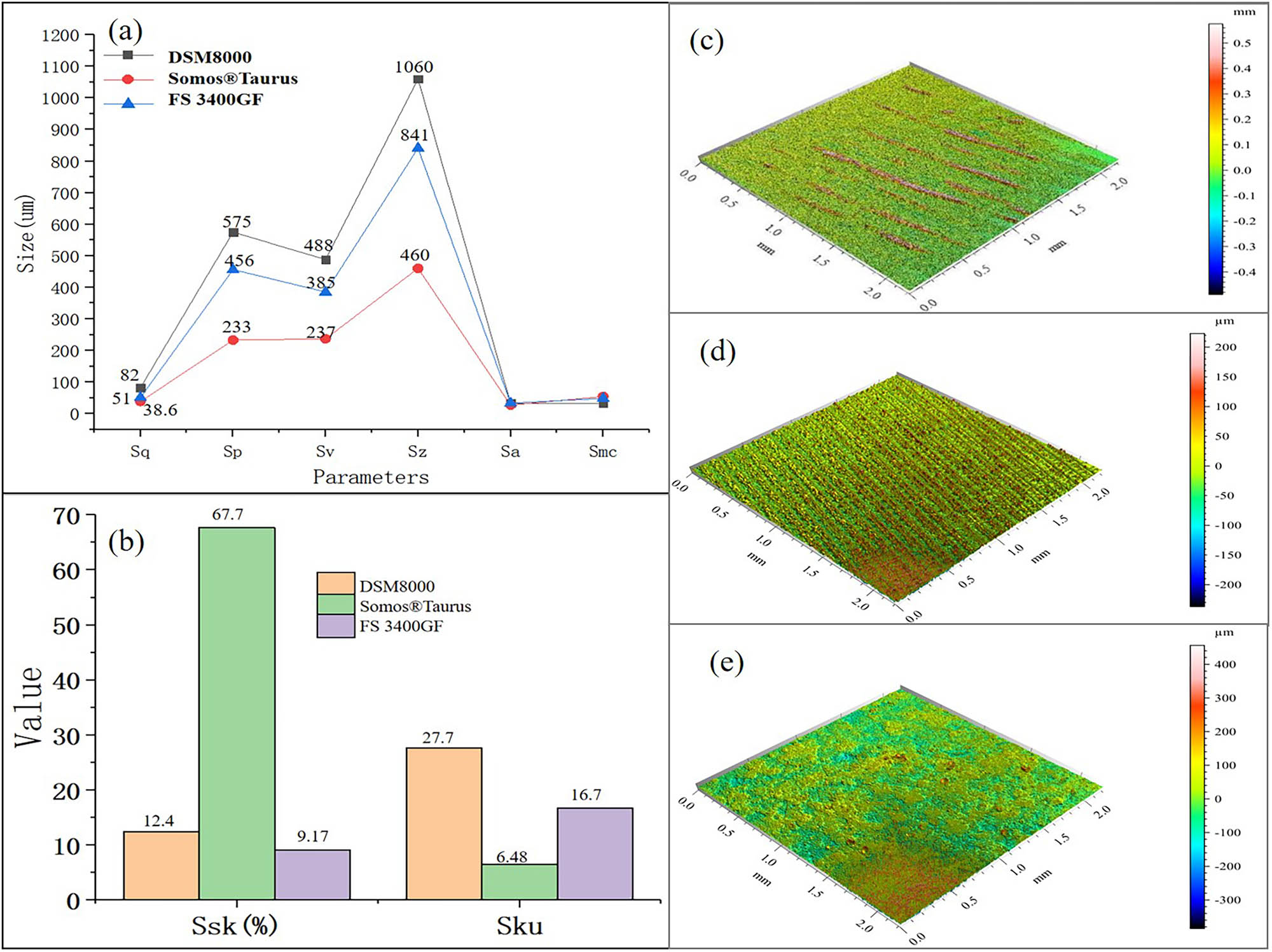

Surface roughness morphology is one of the most important parameters for evaluating machining quality [31]. The surface roughness index parameters of honeycomb structural components made of three materials are shown in Figure 3(a) and (b). Among them, the arithmetic mean height (S a) is the average of the absolute values of the height differences between various points on the surface, which is generally used to evaluate surface roughness [32]. The root mean square height (S q) is the root mean square of the height of each point in the swept area, equivalent to the standard deviation of the height. S p and S v are the maximum peak height and maximum valley depth in the swept area, respectively. The maximum height (S z ) is the sum of the maximum peak height (S p) and the maximum valley depth (S v). In addition, skewness (S sk) is the degree of deviation of surface concavity and convexity, which can be used to determine the parameter of roughness shape (concavity and convexity) tendency through the numerical value of S sk. Kurtosis (S ku), also known as sharpness, can be used to determine the parameters of roughness, shape, and sharpness. The functional parameter (S mc) is the inverse ratio of materials in the same region, indicating the reverse loading area rate, S mc(p) represents the height that meets the loading area rate p%.

Surface roughness evaluation of three types of honeycomb structural components: (a) plot of surface roughness parameters, (b) Skewness (S sk) and kurtosis (S ku), 3D surfaces roughness view of (c) DSM 8000, (d) Somos® Taurus, and (e) FS 3400GF.

As can be seen from Figure 3(a) that using the S a value to evaluate the surface roughness index, the surface roughness of structural components of the three materials is similar, and there is no significant difference. The results of S p and S v indicate that DSM 8000 has the highest value, followed by FS 3400GF and Somos® Taurus. Therefore, the surface roughness indicators of Somos® Taurus honeycomb structural components are lower than the other two.

Second, the results of S sk indicate that the height distribution of the three structural components is relatively lower than the average surface, showing a valley. Among them, the difference in surface roughness wave valleys between DSM 8000 and FS 3400GF structural components is small, while the surface roughness wave valleys of Somos® Taurus honeycomb structural components are the most significant in depth. Relatively speaking, the S ku results indicate the presence of obvious needle like sharp spikes on the surfaces of all three, and that of DSM 8000 is being the most prominent, FS 3400GF material taking the second place, and Somos® Taurus honeycomb structural components being the least significant.

In addition, the roughness morphology image as portrayed in Figure 3(c) further confirms the existence of millimeter-scaled bands and ridges along with obviously same direction distribution on the surface of the DSM 8000 structural plane (S z = 1,060 µm, S p = 575 µm), which are twice that of the Somos® Taurus honeycomb structural component as shown in Figure 3(d), and the latter is mostly uniformly distributed with gradual bands and grooves. The results indicate that the surface morphology of structural components made of DSM 8000 and FS 3400GF materials is irregular and scattered, with the smallest degree of surface roughness deviation (S sk = 9.17%). The surface of Somos® Taurus as shown in Figure 3(d) exhibits a uniform and regular lattice pattern. The surface of the structural components of FS 3400GF material as shown in Figure 3(e) exhibits irregular shape and size distribution of micro-bead particles and their aggregates, so there are no obvious striped ridges or concave convex strips on the surface.

3.3 Compressive mechanical behavior analysis

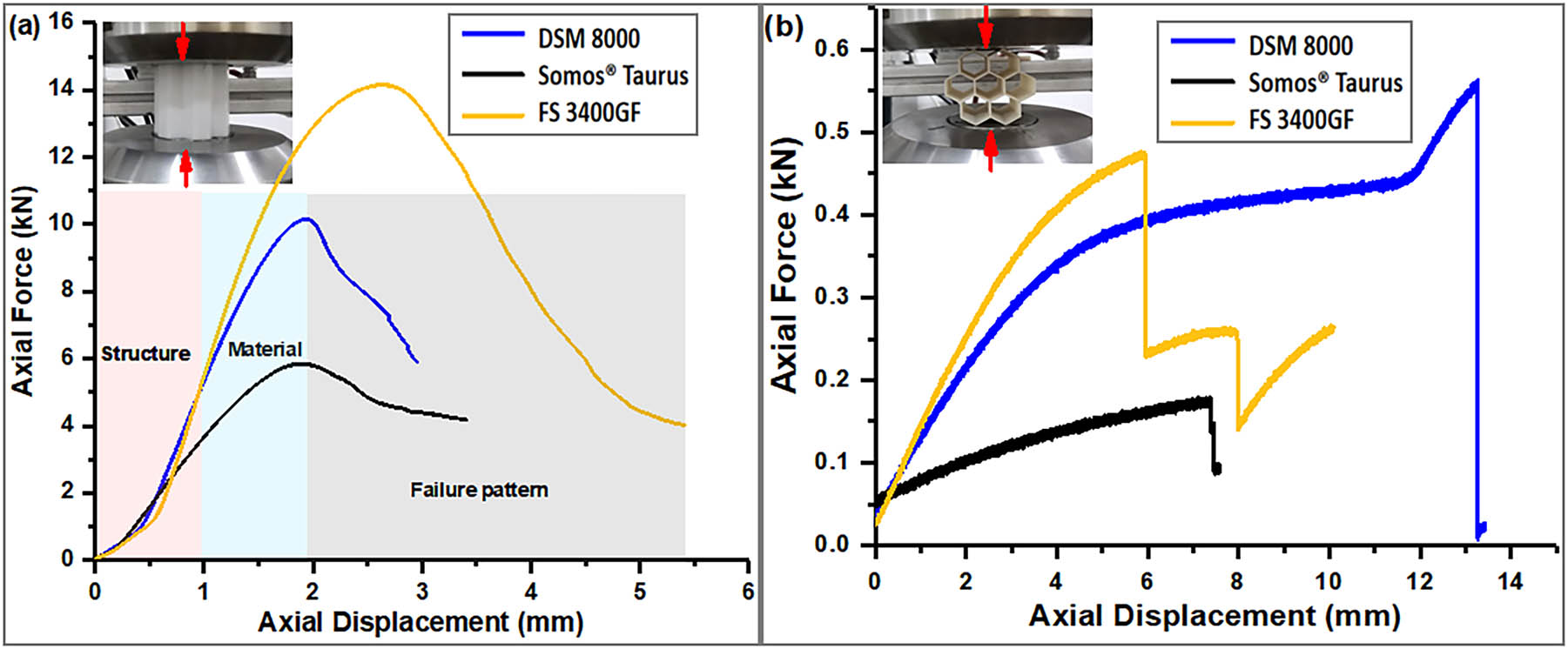

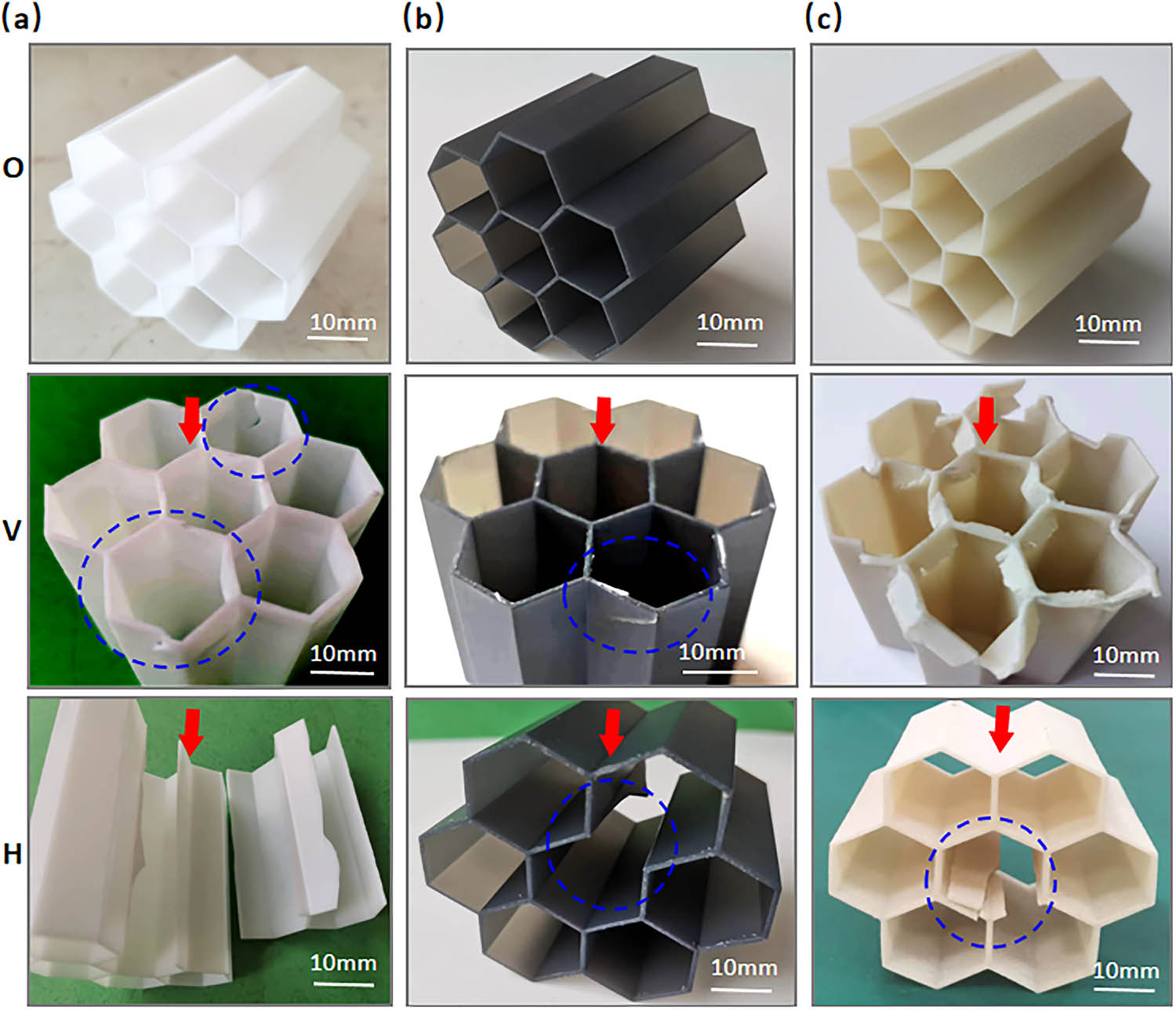

The compressive mechanical behavior analysis of honeycomb structural components made of three materials is trying to figure out how the materials and structure contributed to the overall compression response. And the vertical (V) compression mechanical behavior of honeycomb structural components is plotted in Figure 4(a). It is very noticeable that FS 3400GF can withstand a maximum force of 14.1 kN in vertical compression, while DSM 8000 can hold up to a relative less maximum force of 10.1 kN, and Somos® Taurus is the lowest one of 5.8 kN. The vertical compression response indicated that FS 3400GF with such honeycomb structure bears significantly higher pressure than the other two materials, due to the presence of glass microspheres as reinforcing filler in FS 3400GF [33]. As the vertical pressure gradually increases further, the honeycomb structure plays a primary role, followed by the overall deformation of the structure, which makes the mechanical properties of the material to play a secondary role. Finally, the inconsistent deformation of the stress surface of the honeycomb structure results in different failure modes, indicating that this is closely related to the printed honeycomb structure, but has a secondary correlation with the materials themselves and their composition. This can also be consistent with the macroscopic failure morphology presented in the V direction as depicted by the failure observation shown in Figure 5.

Compression force curves of three types of honeycomb structural components in (a) vertical and (b) transverse directions.

Failure patterns of three types of honeycomb structural components before and after compression test. (a) DSM 8000, (b) Somos® Taurus, and (c) FS 3400GF (O represents uncompressed state, V represents vertical, and H represents transverse, the red arrow represents the direction of force application and the blue circle represents the location of transverse failure).

Compared with the vertical direction, the transverse (H) compression behavior is shown in Figure 4(b). As different to that of vertical one, FS 3400GF could bear a maximum lateral force of 0.47 kN, DSM 8000 is of 0.56 kN, and Somos® Taurus is of 0.17 kN. Such significant differences indicate that lateral compression failure is highly likely to occur, which is more distinct from vertical compression failure. This also implies that the magnitude of compressive force that the structure can withstand in shoulder-to-shoulder combinations similar to that of regular hexagons is correlated with material properties, while the testing condition has little effect on the structure. This conclusion is completely consistent with the macroscopic morphology characteristics of cracks and deformation failure presented in the H-direction compression test in Figure 5. The maximum force and displacement endured are entirely determined by the mechanical properties of the specific material itself.

In Figure 5, the vertical failure is manifested as failure on the contact plane, with the surface depressions on DSM 8000 and FS 3400GF, while Somos® Taurus has cracks near the contact surface. The transverse compression failure mode starts from the inside, such as Somos® Taurus and FS 3400GF structural components lack an internal piece and have no obvious surface damage, while the DSM 8000 is the most severely damaged, directly splitting into two parts.

4 Conclusions

This article presents the preparation of the honeycomb structure samples using SLA technology with an adoption of three different photosensitive resin materials, namely DSM 8000, Somos® Taurus, and FS 3400GF. In order to provide experimental support for their functional applications, surface observation, roughness analysis, and compression experiments were conducted for comparing and analyzing the compression characteristics of honeycomb structure made of three types of materials. It is found out that DSM 8000 has a smooth surface with clearly oriented stripes or ridges, and the surface of Somos® Taurus exhibits uniform and regular lattice like structures, while the surface of FS 3400GF structural components exhibits irregularly shaped micro-bead particles. Additionally, according to the arithmetic mean height S a value used to evaluate the surface roughness index, the surface roughness of structural components from the three materials is close to each other without any significant difference. And both results of the maximum peak height S p and maximum valley depth S v indicate that DSM 8000 has the highest value, followed by FS 3400GF and Somos® Taurus in sequence. Therefore, the surface roughness indicators of Somos® Taurus honeycomb structural components are lower than the other two types.

Furthermore, FS 3400GF can withstand a maximum compression force of 14.1 kN in vertical compression, while it is 10.1 kN for DSM 8000 and 5.8 kN for Somos® Taurus, indicating that FS 3400GF bears significantly higher vertical pressure than the other two materials. The maximum force bore by FS 3400GF under lateral compression is 0.47 kN, DSM 8000 is 0.56 kN, and Somos® Taurus is 0.17 kN, suggesting that the lateral compression failure is highly likely to occur. In a word, three types of honeycomb structural components were found to have vertical failure positions on the contact surface, while transverse compression failure was located inside the structural components.

Certainly, there are also some deficiencies in this study. For example, the research method for the failure modes of structural components is somewhat single. In the follow-up, a more detailed analysis can be conducted on the crack propagation situation and path, which can be used for the structural optimization of such materials to enable them to adapt to more complex and harsh working conditions.

-

Funding information: This research project has been supported by the cooperative research project between Shanghai Dianji University and Zhejiang Lianda Forging Co., Ltd, with a project number of 23B0351.

-

Author contributions: All authors participated in the experimental design. Bomin Liu is responsible for improving the experiment and searching for literature. Shengbin Cao is responsible for writing the article. Jiayi Zheng is mainly responsible for the implementation of experiments and the analysis of data. Fenghua Cao data simulation analysis. Mingliang Yu improved image processing and experimental equipment.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Najmon, J. C., Raeisi, S., Tovar, A. (2019). Review of additive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry. In: F. Froes, R. Boyer, (Eds.), Additive manufacturing for the aerospace industry (pp. 7–31). Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.10.1016/B978-0-12-814062-8.00002-9Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bhanvadia, A. A., Farley, R. T., Noh, Y., Nishida, T. (2021). High-resolution stereolithography using a static liquid constrained interface. Communications Materials, 2, 1–7.10.1038/s43246-021-00145-ySearch in Google Scholar

[3] Zhongliang, L. U., Bo, J. I., Jiangping, Z. H., Kai, M. I., Dichen, L. I. (2014). Defects control of manufacturing ceramic mold of hollow turbine blade based on stereo lithography. Journal of Mechanical Engineering, 50, 111–117.10.3901/JME.2014.21.111Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wang, Y. Q., Wu, H. Y., Jia, Z. Y., Huang, W., Lu, B. H. (2012). Research on the accuracy of mask projection stereo-lithography. Advanced Materials Research, 566, 542–547.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.566.542Search in Google Scholar

[5] Grabulosa, A., Moughames, J., Porte, X., Brunner, D. (2022). Combining one and two photon polymerization for accelerated high performance (3 + 1)D photonic integration. Nanophotonics, 11, 1591–1601.10.1515/nanoph-2021-0733Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Rajamanickam, V. P., Ferrara, L., Toma, A., Proietti Zaccaria, R., Das, G., Di Fabrizio, E., et al. (2014). Suitable photo-resists for two-photon polymerization using femtosecond fiber lasers. Microelectronic Engineering, 121, 135–138.10.1016/j.mee.2014.04.040Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhang, X., Xu, Y., Li, L., Yan, B., Bao, J., Zhang, A. (2019). Acrylate-based photosensitive resin for stereolithographic three-dimensional printing. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 136, 47487.10.1002/app.47487Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kang, X., Li, X., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Duan, Y. (2021). Continuous 3D printing by controlling the curing degree of hybrid UV curing resin polymer. Polymer, 237, 124284.10.1016/j.polymer.2021.124284Search in Google Scholar

[9] Hughes, T., Simon, G. P., Saito, K. (2019). Photocuring of 4-arm coumarin-functionalised monomers to form highly photoreversible crosslinked epoxy coatings. Polymer Chemistry, 1, 2134–2142.10.1039/C8PY01767KSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Abdallah, M., Bui, T., Goubard, F., Theodosopoulou, D., Dumur, F., Hijazi, A., et al. (2019). Phenothiazine derivatives as photoredox catalysts for cationic and radical photosensitive resins for 3D printing technology and photocomposite synthesis. Polymer Chemistry, 1, 6145–6156.10.1039/C9PY01265FSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Shahzadi, L., Maya, F., Breadmore, M. C., Thickett, S. C. (2022). Functional materials for DLP-SLA 3D printing using thiol-acrylate chemistry: resin design and postprint applications. ACS Applied Polymer Materials, 4, 3896–3907.10.1021/acsapm.2c00358Search in Google Scholar

[12] Krishnasamy, B., Shanmugaraj, B. P., Murugavel, S. C., Dai, L., Petri, D. F. S. (2020). Investigation on dual functional epoxy resins containing photosensitive group in the main chain for photoresist applications. International Journal of Polymer Analysis & Characterization, 25, 198–215.10.1080/1023666X.2020.1780849Search in Google Scholar

[13] Tan, S., Wu, Y., Hou, Y., Deng, H., Liu, X., Wang, S., et al. (2022). Waste nitrile rubber powders enabling tougher 3D printing photosensitive resin composite. Polymer, 243, 124609.10.1016/j.polymer.2022.124609Search in Google Scholar

[14] Sugita, H., Matsumura, N., Matsumoto, H., Tanaka, K. (2019). Micro-patterning of functional coatings guided by a photosensitive degradable template. Progress in Organic Coatings, 132, 264–274.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.02.038Search in Google Scholar

[15] Qi, C., Jiang, F., Yang, S. (2021). Advanced honeycomb designs for improving mechanical properties: a review. Composites. Part B, Engineering, 227, 109393.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109393Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mohammadi, H., Ahmad, Z., Petrů, M., Mazlan, S. A., Faizal Johari, M. A., Hatami, H., et al. (2023). An insight from nature: honeycomb pattern in advanced structural design for impact energy absorption. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 22, 2862–2887.10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.12.063Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mondal, S., Katzschmann, R., Clemens, F. (2023). Magnetorheological behavior of thermoplastic elastomeric honeycomb structures fabricated by additive manufacturing. Composites Part B: Engineering, 252, 110498.10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110498Search in Google Scholar

[18] Koch, S., Duvigneau, F., Orszulik, R., Gabbert, U., Woschke, E. (2017). Partial filling of a honeycomb structure by granular materials for vibration and noise reduction. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 393, 30–40.10.1016/j.jsv.2016.11.024Search in Google Scholar

[19] Amith Kumar, S. J., Ajith Kumar, S. J. (2020). Low-velocity impact damage and energy absorption characteristics of stiffened syntactic foam core sandwich composites. Construction & Building Materials, 246, 118412.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118412Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ingrole, A., Hao, A., Liang, R. (2017). Design and modeling of auxetic and hybrid honeycomb structures for in-plane property enhancement. Materials & Design, 117, 72–83.10.1016/j.matdes.2016.12.067Search in Google Scholar

[21] Huang, W., Zhang, Y., Xu, Y., Xu, X., Wang, J. (2021). Out-of-plane mechanical design of bi-directional hierarchical honeycombs. Composites Part B, Engineering, 221, 109012.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109012Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang, Y., Xu, X. (2022). Machine learning surface roughnesses in turning processes of brass metals. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 121, 2437–2444.10.1007/s00170-022-09498-1Search in Google Scholar

[23] Zhang, Y., Xu, X. (2021). Machine learning cutting force, surface roughness, and tool life in high speed turning processes. Manufacturing Letters, 29, 84–89.10.1016/j.mfglet.2021.07.005Search in Google Scholar

[24] Yang, D., Guo, L., Fan, C. (2024). Mechanical behavior of 3D-printed thickness gradient honeycomb structures. Materials, 17, 2928.10.3390/ma17122928Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Kou, J., Li, Y., Yang, P., Zhang, J. (2017). A novel blood coagulation measuring method based on the viscoelasticity of non-Newtonian fluid. World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 5, 134–151.10.4236/wjet.2017.54B015Search in Google Scholar

[26] Huang, B. W., Du, Z., Tao, Y., Han, W. (2017). Preparation of a novel hybrid type photosensitive resin for stereolithography in 3D printing and testing on the accuracy of the fabricated parts. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology (Materials Science), 32, 726–732.10.1007/s11595-017-1659-xSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Huang, B. W., Weng, Z. X., Sun, W. (2011). Study on the properties of DSM SOMOS 11120 type photosensitive resin for stereolithography materials. Advanced Materials Research, 233–235, 194–197.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.233-235.194Search in Google Scholar

[28] Fu, M., Higashihara, T., CA, M. U., Abaimov, S. G. (2017). Recent progress in thermally stable and photosensitive polymers. Polymer Journal, 50, 57–76.10.1038/pj.2017.46Search in Google Scholar

[29] Hong, H., Nasrollahi, A., Park, S. (2021). Transparent UV-blocking photonic film based on reflection of cholesteric liquid crystals. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 344, 117739.10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117739Search in Google Scholar

[30] Vasiliev, E. O., Sethi, S. K., Nath, B. B. (2011). Nonequilibrium carbon ionization states and the extragalactic far-UV background with HeII absorption. Astrophysics and Space Science, 335, 211–215.10.1007/s10509-010-0585-6Search in Google Scholar

[31] Tonietto, L., Gonzaga, L., Veronez, M. R., Kazmierczak, C. D. S., Arnold, D. C. M., Costa, C. A. D. (2019). New method for evaluating surface roughness parameters acquired by laser scanning. Scientific Reports, 9, 15016–15038.10.1038/s41598-019-51545-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Myshkin, N. K., Grigoriev, A. Y., Chizhik, S. A., Choi, K. Y., Petrokovets, M. I. (2003). Surface roughness and texture analysis in microscale. Wear, 254, 1001–1009.10.1016/S0043-1648(03)00306-5Search in Google Scholar

[33] Stagnaro, P., Utzeri, R., Vignali, A., Falcone, G., Iannace, S., Bertini, F. (2021). Lightweight polyethylene-hollow glass microspheres composites for rotational molding technology. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 138, 49766.10.1002/app.49766Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method