Abstract

Two prototypes of a women’s skirt intended for use in the autumn season were designed and manufactured using innovative sewing machines, along with their programming. This article describes the innovative sewing machines used to sew two prototypes of a women’s skirt – specialist machines, semi-automatic, and automatic sewing machines. The main assumption during the sewing process of the designed skirt prototypes was to program the selected sewing machines necessary for their implementation. This article refers to Industry 4.0 through the automation of the production process, which has contributed to increased productivity. In addition, the impact of using modern sewing machines on the lead times of two models of women’s skirts is presented. This article describes the individual stages of programming the innovative machines used, such as an automatic machine for sewing small elements, a two-needle lockstitch with switchable needles, a clothing buttonhole machine, or a button sewing machine.

1 Introduction

Sewing machines are currently the largest group of machines used in garment manufacturing processes. At present, the number of design varieties manufactured exceeds 10,000 and is constantly increasing. The reason for the consistently produced new design varieties is due, on the one hand, to technical progress in the construction of sewing machines and, on the other, to continual alterations in the construction of garments and their structure [1]. The first sewing machines were developed over 200 years ago. Their operating principles have not changed significantly since then. The main reason contributing to the development of the sewing machine is the increase in its work efficiency. With the development of sewing machines, the time required to produce one piece of clothing has decreased by 80% [2,3].

Currently, sewing machines are subject to various classifications. Most often, however, it is a given company or manufacturer that creates its internal product categories. This is determined by the functions and construction of the machines and all their parameters (Figure 1) [1,2].

![Figure 1

Technological classification of sewing machines [1].](/document/doi/10.1515/aut-2025-0053/asset/graphic/j_aut-2025-0053_fig_001.jpg)

Technological classification of sewing machines [1].

Sewing machines can perform two types of interlacing: open and closed. This means that chain stitches or shuttle stitches can be created. Sewing machines can also be divided according to the technological cycle. There is an open technological cycle and a closed technological cycle. In the open cycle, the machine operator is obliged to decide on the number of cycles necessary to complete the task, and can freely change this number. In the closed technological cycle, the machine operator cannot change the machine parameters, and only the technical service can adjust its operating parameters [1,2,4].

Sewing machines with an open technological cycle can be divided into basic machines and special machines. The group with a closed technological cycle includes automatic machines.

Before fully automatic sewing machines, semi-automatic sewing machines appeared in the first half of the twentieth century. After the user initiates the cycle, these machines perform a single technological cycle independently. Examples of semi-automatic machines include a two-needle lockstitch machine, a bartacking machine, a belt looping machine, and a button sewing machine. A sewing machine is distinguished by having two additional mechanisms: stopping the machine after the cycle is completed and programming the technological cycle [1,5,6].

The end of the twentieth century contributed to the introduction of electronics to the housing of sewing machines. One of the first was the “Centurion” series of machines by Singer. The traditional machine drive was changed, and the option of saving the speed of the lockstitch during the open technological cycle was added. Another example was a machine manufactured by Union Special with the option of electronic programming. It was designed for embroidering inscriptions on fabrics. It had a scanner and an x-y table measuring several dozen centimeters with the option of electronic control. Punched cards were also replaced with electronically controlled ones. This application was found in multi-head embroidery machines [7,8].

The latest additions to sewing machines are microprocessors and stepper motors. This has improved the operation of simple machine mechanisms and increased the range of machine control and regulation.

In summary, the first sewing machines were characterized by high noise emission and low sewing speed (600–800 stitches/min), while in the shuttle stitch machines, the capacity of the looper bobbin was insufficient. This caused many unnecessary machine interruptions, which decreased the work efficiency. Large machine assemblies using asynchronous AC motors needed a lot of electrical energy due to the extended time of machine operation without any load in the so-called idle run. To prevent this phenomenon, capacitor stations were built [6,7]. The following years contributed to the change in the sewing speed to 6,000 stitches/min. This has increased productivity and the ability to execute the new technological operations. The breakthrough was the introduction of DC motors, which consumed 25% less electrical energy than their predecessors. Electronic components and automated simple work programming operations were also introduced, including automatic thread cutting and fastening at the beginning and end of stitching. The problem of constantly having to change the looper coil has also been solved by introducing automatic coil changing; however, this is an expensive procedure and impossible to implement on some sewing machines [8,9,10].

Currently, there is a drive to continuously modernize sewing processes. Unfortunately, sewing processes are often carried out in Asian countries, where work is performed at a much lower cost. Technologists are constantly trying to modify the process of creating a shuttle stitch. They are focusing on finding solutions in changing the plate tensioner, which has not changed since the first Singer machine. They are also trying to change the way the machine is fed with a needle thread. The new solution aims to adjust the stitch faster than it is done at present. The common problem of all kinds of thread breakage and deterioration negatively affects the quality of the sewing, the quality of the seams, and the quality of the garment being sewn. The transport mechanism also deserves design changes. It requires constant adjustment, is imprecise, and must be adjusted each time to a specific fabric. Modern solutions, such as differential and needle transport, which have not fully met the current production requirements, should also be changed. All these problems can be solved, but they require a lot of money, extensive knowledge of specialists, as well as adapting the clothing structure to its automatic production [8,11,12,13].

Industry 4.0 defines a new industrial revolution and leads to changes in the way of managing and implementing production operations. The needs of intensified productivity, improved flexibility, and reduced costs in production for Industry 4.0 require the development of new models and patterns that are appropriate for the transformation in production management and operations [14,15,16].

In line with the introduction of Industry 4.0, a range of changes is currently being introduced across the textile industry. Technicians and designers are focusing on the innovation in machine design of Internet of Things (LoT), AI models, digital twin machines, robotics, and automatics. One of the more recent technological developments is the introduction of a remote level of assessment for machine operators. This is made possible by LoT technology, which registers the electricity consumed in real time, analyses the data with power usage, and allocates it to the individual technological operations. As a result, it can classify the operator’s skills, the difficulty of the task, and its classification in relation to other workers. This advanced system makes it conceivable to increase employee productivity and company efficiency. Companies are now seeking to incorporate AI technology to AI-analyse sewing times, search for errors, inspect seam quality, and provide their solutions and recommendations [16,17].

The clothing industry is strengthening in terms of quality, flexibility, productivity, and speed through investments in research and development. This new revolution not only contributes to the improvement of existing processes but also leads to changes in decision-making that are related to changing customer requirements [18,19].

The fourth industrial transformation is driven by the digitalization of information, machine connectivity, and the virtualization of production systems. The task of the smart factory of the future is to replace intellectual but repetitive work with robotization and automation of work processes. This revolution leads to increased productivity, improves working conditions, and contributes to the emergence of new professions [18,20,21].

New technologies should be introduced in the production sector. These include computerized yarn testing, fabric simulations, and self-diagnosing machines for preventive maintenance [22], in addition to automatic cutting and sewing processes, or computer-controlled knitting technologies [23,24].

Currently, in Industry 4.0, the assessment of the quality of a clothing product is very important, which is a complex issue, because in many aspects, it is a subjective assessment of the consumer. According to the PN-EN ISO 9000:2006 standard [25], “quality is the degree to which a set of inherent properties meets requirements.” According to this definition, a great deal of freedom can be observed in this concept [26]. Currently, quality can be defined as all properties of an object related to its ability to meet actual and expected needs. For a given product to fulfill a specific role, it should meet the conditions set, mainly correspond to contemporary fashion, not threaten the safety of use, and meet aesthetic requirements. The quality of clothing is the result of three factors (which are not always interdependent): consumer expectations, the designer’s actions, and manufacturing possibilities. The common dependencies of these links can be demonstrated in the form of the so-called total quality. The quality of the product is modeled in pre-production, production, and post-production zones.

The results of various studies confirm that the perception of clothing quality by consumers is multidimensional and concerns various issues, including personal expectations regarding high-quality clothing [1]. The study conducted by Hines and Swinkers [27] showed that the greatest impact on the assessment is exerted by features related to the appearance of clothing. Moreover, regardless of the type of product, price is a very important determinant [28]. Most respondents indicate that quality is important in their decisions to purchase clothing. The research conducted by Salerno-Kochan [26] indicates the ranking of selected features depending on their importance in the assessment of the quality of products and also presents their grouping and segregation (Table 1).

Summary and categorization of individual factors influencing clothing quality by women and men [26]

| Specification | Factor importance | Quality attributes by | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Category I | Most important | Comfort of use and toxicity | Comfort of use, toxicity, health properties, aesthetics, convenience of use, safety, and quality of finish |

| Category II | Very important | Functional properties, durability, hygienic properties, grip, raw material composition, and maintenance method | Functional properties, durability, hygienic properties, grip, raw material composition, and maintenance method |

| Category III | Important | Durability, hygienic properties, grip, raw material composition, maintenance method, fashion, brand, and price | Type of material, brand of product, fashion, price, impact of the product on the environment, and presence of a certificate |

| Category IV | Not very important | Type of material, environmental impact of the product, and presence of a certificate | — |

In this article, two prototypes of a women’s skirt intended for use in the autumn season were designed and manufactured using innovative sewing machines along with their programming. Automation of the production process of the two models of selected clothing assortment, and thus, the increase of productivity, is connected with the fourth industrial transformation. This article shows that the use of modern sewing machines shortens the time of performing specific technological operations of realized skirts, and thus, shortens the total time of their production.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Two different fabrics were chosen to make two prototypes of a women’s skirt (Table 2). Their selection was guided by hues that reflected the shades of autumn. Table 2 presents the characteristics of the fabrics given by the manufacturer.

Characteristics of the fabrics used for the women’s skirt prototypes

| Fabric 1 – skirt I | Fabric 2 – skirt II | |

|---|---|---|

| Photo |

|

|

| Raw material composition | 92% polyester | 82% polyester |

| 8% polyamide | 15% polyamide | |

| 3% elastane | ||

| Mass per square meter (g/m2) | 283.0 | 322.0 |

| Thickness (mm) | 0.92 | 0.98 |

Both selected fabrics had similar raw material composition, surface mass, and thickness.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 First model of women’s skirt

The first model of the women’s skirt is designed to be worn in the autumn season and dedicated to women who follow fashion (Figure 2). The skirt is knee-length. It has four pleats at the front and four pleats at the back, fastened with buttons located at the front of the product. Owing to the belt with belt loops, it is easy to adjust the skirt to the figure. Fancy sewn-in buttons emphasize the uniqueness of the skirt. The model is widened toward the bottom, owing to which the female waist is perfectly emphasized. The skirt was modeled from the construction of the basic skirt. Table 3 lists the fabrics and accessories used to make the first model of the skirt. Table 4 shows the chronology of technological operations that were performed to make the skirt.

Model drawing of the front and back of the first model of a woman’s skirt.

List of components of the first model of a women’s skirt

| Type of material | Name of the element | Number of elements |

|---|---|---|

| Base fabric | Right front | 1 |

| Left part of the front | 1 | |

| Back | 1 | |

| Belt | 1 | |

| Belt loops | 8 | |

| Adhesive insert | Button cover | 1 |

| Hole covers | 1 | |

| Belt | 1 | |

| Button | Button | 10 |

Summary of technological operations of the first model of a women’s skirt

| Nr | List of technological operations | Type of equipment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fusing the waistband, covering of the buttons, and covering of the buttonholes | Steam iron |

| 2 | Hemming the sides of the left side of the front | 4-thread overlock |

| 3 | Hemming the right side of the front | 4-thread overlock |

| 4 | Hemming the skirt at the back | 4-thread overlock |

| 5 | Sewing the left side of the skirt to the back of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 6 | Sewing the right side of the skirt to the back of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 7 | Ironing the seams | Steam iron |

| 8 | Stitching on the pleats at the front and back of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 9 | Sewing of loops | Belt looper machine |

| 10 | Buttonhole stitching on the front of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 11 | Backstitching to buttonholes on the front of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 12 | Sewing of loops together with the skirt belt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 13 | Backstitching of loops | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 14 | Backstitching of the belt and finishing of the belt ends | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 15 | Making clothing buttonholes | Buttonhole machine |

| 16 | Sewing on buttons | Button machine |

| 17 | Hemming of skirt bottoms | 4-thread overlock |

| 18 | Finishing the bottom of the skirt | Blind stitch machine |

| 19 | Final ironing of the skirt | Steam iron |

In order to realize the designed first model of women’s skirt, the following innovative sewing machines were used:

PFAFF 3307 button sewing machine (semi-automatic sewing machine)

Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX clothing buttonhole machine (semi-automatic sewing machine)

Siruba HF008-02064/FBQ belt looper (specialized machine)

STROBEL 103 blind stitch machine (specialized machine).

2.2.1.1 PFAFF 3307 button sewing machine

The PFAFF 3307 button sewing machine is a semi-automatic sewing machine that performs flat button sewing operations. The machine sews using a chain stitch. It can sew buttons with two, three, four, and six eyelets. Depending on the button being sewn on, the machine must be programmed appropriately. The semi-automatic machine can be programmed once, and this function is used when only one button is sewn on.

The semi-automatic control panel allows for any programming of button sewing. The machine’s operating field consists of a panel with a display and 27 buttons that allow one to create their programs. The symbols that can be found on the panel screen are the number of revolutions, height of the fastening claw, selected program number, and number of sewn-on buttons [29]. The machine also has a function for emergency stopping of the sewing process, forward and backward pacing, setting the basic position, setting the position of the button clasp, as well as a separate button for programming and counting the number of sewn-on buttons. There are four different ways to sew a button.

Programming a semi-automatic machine, such as a button sewing machine, involves selecting the appropriate parameters for the type of button. Positions P01, P02, P03, and P04 correspond to the button sewing positions and are presented in Table 5.

Button hole positions in the first model of a woman’s skirt

| Puncture position | Position X | Position Y |

|---|---|---|

| P01 | 22 | 11 |

| P02 | −22 | 11 |

| P03 | 22 | −25 |

| P04 | −22 | −25 |

The X and Y positions were selected so that the needle would fit perfectly into the center of the button hole.

Position P07 corresponds to the number of stitches. Too few stitches will cause an error, and the machine will not be able to perform the given operation. Too high a value will make the appearance of the sewn button unsightly, and this operation is also susceptible to errors, such as needle breakage or button cracking. When programming the machine, one can choose to set the number of stitches from 2 to 99. When programming the machine, 20 stitches were set.

Position P08 is inter-operational thread trimming, selecting position I turns trimming off, and position II turns inter-operational trimming on.

Function P09 is the selection of the button sewing pattern. When programming the button sewing for this skirt model, P09 = 1 was selected. The appearance of the so-called traditional button sewing was obtained – cross sewing.

Position P10 decides about the final knot, I – turns it off, and II – turns it on. Button sewing is set P10 = II.

2.2.1.2 Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX clothing buttonhole machine

The Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX clothing buttonhole machine is a semi-automatic sewing machine that sews a chain stitch with an open technological cycle. It is a machine with an additional third thread inserted “in the side” in the middle edge of the clothing buttonhole. It protects the buttonhole from unraveling. The semi-automatic machine has the ability to make two bartacks: convergent and transverse. The machine makes five types of clothing buttonholes. Each of the parameters can be freely changed.

In order to program a clothing buttonhole machine, after starting the machine, the buttonhole library that best meets one's requirements is selected and then modified [30]. The parameters enabled during machine programming are shown in Table 6.

Parameters programmed on the garment buttonhole machine

| Parameter | Quantity (machine unit) |

|---|---|

| Buttonhole height/slit length | 29 |

| Side seam stitch length | 0.5 |

| Length of the cut thread | 1 |

| Length of thickening stitches at the beginning of the buttonhole | 0.3 |

| Length of thickening stitches at the end of the buttonhole | 0.3 |

| Number of thickening stitches at the beginning of the buttonhole | 3 |

| Number of thickening stitches at the end of the buttonhole | 3 |

| Plate tension when sewing | 45 |

| Plate tension when cutting threads | 14 |

| Tension of the plates at the start of making the buttonhole | 45 |

| Number of stitches in an eyelet | 15 |

| Slant of the eyelet | 5 |

| Stitch width | 0.5 |

| Cutting mode | CA – cutting the buttonhole after sewing it |

| Cutting surface area | 0.2 |

| X-direction cut correction | 0 |

| Y-direction cut correction | 0 |

| Cutting force correction | 0 |

| Length of the converging beam | 3 |

| Tapered bartack stitch width | 0.5 |

| Overlap in the converging lock | 0 |

| Bevel height in the converging beam | 2 |

When programming the buttonhole, the thickness of the fabric was taken into account. The appropriate number of stitches in the eyelet used was 15 so that it would not unravel while taking into account the aesthetic value. The appropriate number of parallel stitches in the stitching was selected as 0.5 so that the stitches were not too thick and did not overwhelm with their appearance. The length of the tapering bar was set to 3, and the width of the buttonhole was set to 0.5, which was also selected for aesthetic values. In order to prevent the thread from breaking during sewing, the thread tension in the plate tensioner was appropriately selected during sewing as 45. Too much tension could lead to the needle breaking during the sewing process. The tension was reduced when cutting the thread. When programming the buttonhole, automatic cutting of the buttonhole after sewing was set. Cutting before sewing is used for thick materials such as Texas or fleece, and the fabric used was not that thick.

2.2.1.3 Siruba HF008-02064/FBQ belt looper

The Siruba HF008-02064/FBQ belt looper is a specialist machine that sews using a chain stitch. This belt looper model is 2-needle, 3-thread. Its task is to easily and quickly make belt loops used in trousers and skirts. It is equipped with two leveling knives that perfectly level the excess material. As a result, the fabric is properly rolled up and sewn to create a long strip. After making it, the length of the loop is simply adjusted to own needs by cutting the long strip into the required sections.

2.2.1.4 STROBEL 103 blind stitch machine

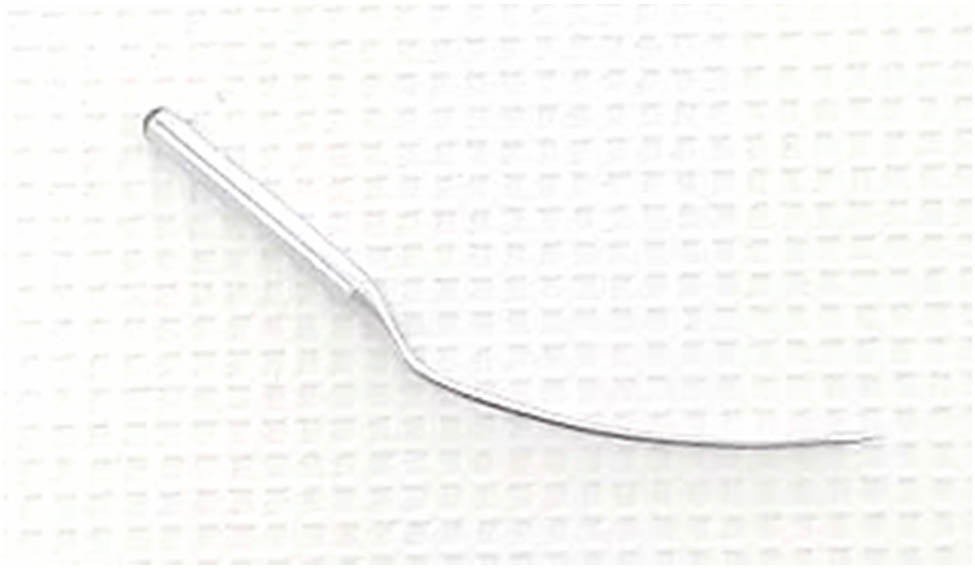

The STROBEL 103 blind stitch machine is a specialist machine that sews with a one-sided covered stitch. The stitch is invisible on the outside of the garment. The machine is equipped with a characteristic, slightly bent needle (Figure 3).

Needle used in a blind stitch machine (own source).

The most common use of the blind stitch is in finishing the legs of trousers, skirts, and sleeves. The seams are made with a special type of blind stitch thread.

In order to finish the lower edge of the skirt, the machine was adjusted to the thickness of the materials used before sewing began, using the crank. The lower edge of the skirt had to be overcast on a 4-thread overlock before sewing. Thanks to this, the needle of the sewing machine can hook the fabric properly during sewing. The bottom of the skirt was ironed to the appropriate width, and the sewing process began. During sewing, the edge of the fabric was guided along the machine guide.

The first completed model of a women’s skirt is presented in the photographs in Figure 4.

Photographs of the front and back of the sewn first model of a women’s skirt.

2.2.2 Second model of women’s skirt

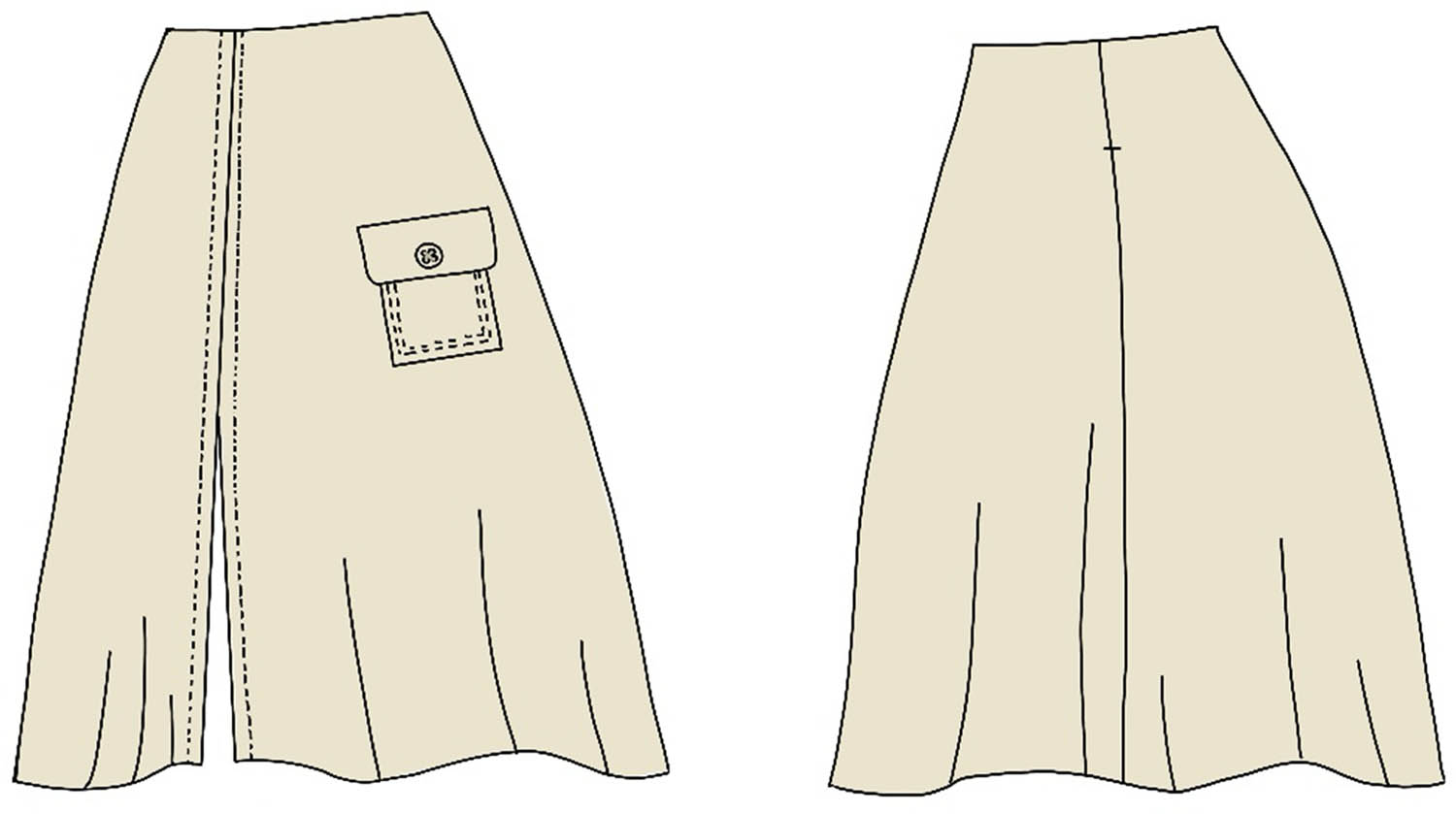

The second model of the women’s skirt is made of light, beige corduroy (Figure 5). It is ideal for cooler, autumn evenings. The skirt is classified as a mini. In this model, a leg slit was designed at the front of the skirt, which was then stitched to emphasize it. A sewn-on, comfortable pocket was added to increase the comfort of use. The pocket is characterized by a flap fastened with a button. The designed pocket fits perfectly on most smartphones currently on the market, which allows one to abandon any additional bags. The skirt is fastened at the back with a hidden zipper. The darts were moved so that the skirt slightly widens toward the bottom. Table 7 presents a list of fabrics and accessories used to make the second model of the skirt. Table 8 shows the chronology of technological operations that were performed to make the skirt.

Model drawing of the front and back of the second model of the women’s skirt.

List of materials and accessories of the second model of women’s skirt

| Material type | Name element | Number of elements |

|---|---|---|

| Base fabric | Right front part | 1 |

| Left front part | 1 | |

| Right back part | 1 | |

| Left back part | 1 | |

| Front cover | 1 | |

| Right side of the back cover | 1 | |

| Left side of the back cover | 1 | |

| Pocket flap | 2 | |

| 1 | ||

| Adhesive insert | Front cover | 1 |

| Right back cover | 1 | |

| Left back cover | 1 | |

| Indoor zipper | Indoor zipper | 1 |

| Button | Button | 1 |

Chronological list of technological operations of the second model of women’s skirt

| No | List of technological operations | Type of equipment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gluing the front cover, left, and right parts of the back cover | Steam iron |

| 2 | Overcasting the side edges of the front cover, the left and right parts of the back cover | 4-thread overlock |

| 3 | Sewing the front facing to the right side of the back cover | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 4 | Sewing the front facing to the left side of the back cover | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 5 | Overcasting the lower edge of the cover | 4-thread overlock |

| 6 | Ironing out the side seams of the facing | Steam iron |

| 7 | Overcasting the side edges of the left front part of the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 8 | Overcasting the side edges of the right front part of the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 9 | Overcasting the side edges of the left back part of the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 10 | Overcasting the side edges of the right back part of the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 11 | Sewing the left and right front of the skirt together, leaving room for a rip | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 12 | Ironing out the seam on the front of the skirt | Steam iron |

| 13 | Topstitching the seam of the left front of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 14 | Topstitching the seam of the right front of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 15 | Sewing a pocket flap | Small-part sewing automatic machine |

| 16 | Making a clothing buttonhole in a pocket flap | Clothing button machine |

| 17 | Sewing the pocket flap to the front of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 18 | Topstitching the pocket flap | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 19 | Overcasting the edge of the pocket | 4-thread overlock |

| 20 | Sewing a button to the pocket | Clothing button machine |

| 21 | Stitching and sewing pockets into the front part of the skirt | Two-needle lockstitch machine |

| 22 | Sewing the left and right parts of the back of the skirt together, leaving room for the indoor zipper | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 23 | Sewing in a indoor zipper | Single-needle lockstitch machine, invisible zipper foot |

| 24 | Sewing the front and back of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 25 | Ironing out the side seams | Steam iron |

| 26 | Sewing the facing to the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 27 | Overcasting the seam where the facing is sewn to the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 28 | Finishing the facing and attaching it to the side seams of the skirt | Single-needle lockstitch machine |

| 29 | Overcasting the hem of the skirt | 4-thread overlock |

| 30 | Finishing the bottom of the skirt | Blind stitch machine |

| 31 | Complete ironing of the product | Steam iron |

The following innovative sewing machines were used to create the designed second skirt model:

PFAFF 3511 small-part sewing machine (automatic machine)

Two-needle lockstitch machine with split needles PFAFF 1240 (semi-automatic sewing machine)

Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX clothing buttonhole machine (semi-automatic sewing machine)

PFAFF 3307 button sewing machine (semi-automatic sewing machine)

STROBEL 103 blind stitch machine (specialized machine).

2.3 PFAFF 3511 small-part sewing machine

The PFAFF 3511 sewing machine sews small elements such as pocket flaps, cuffs, or collars. The machine sews using a shuttle stitch. It has the appropriate tools for the required stitching – cassettes into which individual elements are inserted. Depending on the company, the cassettes have different dimensions and shapes [31]. This specialized machine has a knife and a system for collecting material scraps. The scraps are sucked out using compressed air into a connected container.

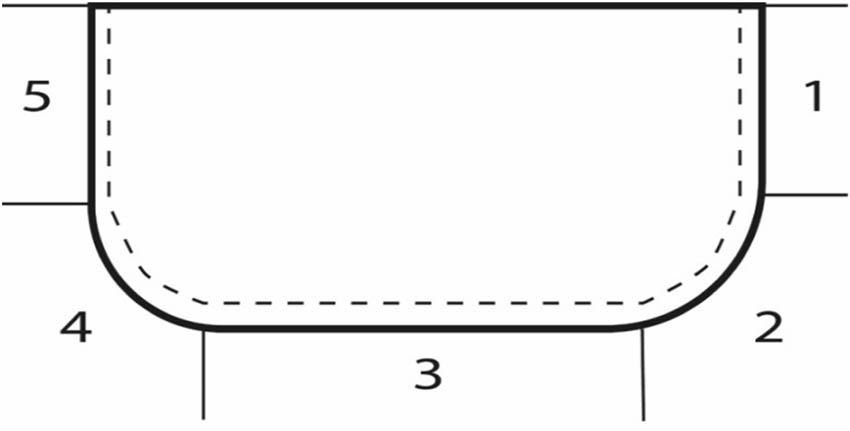

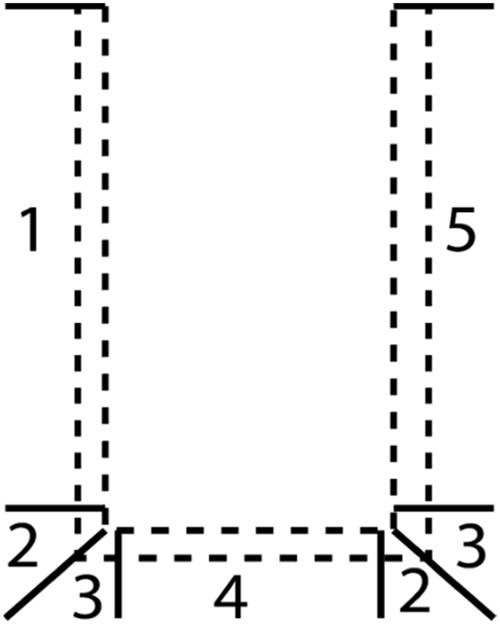

In order to sew the flap, it is necessary to understand the stages of its implementation by the machine. In order to program the machine, the sewing of the flap was divided into five sections (Figure 6).

Presentation of the division of stitching sections on a machine for small elements (own source).

When programming the machine for sewing small elements, the initial bartack was first turned on so that the flap would not unravel. The machine’s stitch density is standardized depending on the material.

The designed flap was programmed, as shown in Table 9.

Programming individual sections of the flap

| Sewn section | Number of stitches (needle strokes per 1 cm) | Speed (needle strokes per minute) | Additional features |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 27 | 1,600 | Initial bolt |

| P2 | 33 | 600 | — |

| P3 | 47 | 1,400 | — |

| P4 | 33 | 600 | — |

| P5 | 27 | 1,300 | Automatic thread cutter |

According to Table 9, the number of stitches on the first and last stitching section was the same and the smallest, 27 needle strokes per cm. Both sections differed in the stitching speed. The highest speed of 1,600 needle strokes per minute was set for the first section. The second and fourth sections were programmed in the same way. The number of stitches was 33 needle strokes per cm, and the speed was 600 needle strokes per minute. The fifth stitching section was characterized by an optimal sewing speed of 1,300 strokes per minute, an end bartack, and automatic thread cutting. By programming five stitching sections on the small-part sewing machine, the designed flap was made. The sewn flap had to be turned right side out and ironed.

2.4 Two-needle lockstitch machine with split needles PFAFF 1240

The PFAFF 1240 two-needle lockstitch is a semi-automatic sewing machine that allows for turning off one of the needles during operations. The machine sews with a shuttle stitch, has two needles, and two loopers with two bobbins located under the tabletop. The machine is equipped with a control screen for its programming. It is a semi-automatic sewing machine because, despite the possibility of its programming, the operator is still required to manipulate the material and fully control the sewing process. The machine can be used for one-time sewing, or its stitching can be programmed so that on a mass scale, it maintains the same appearance.

In order to sew the designed pocket, it is necessary to understand the stages of its execution by the machine. The two-needle lockstitch allows programming five sections of negatives. For this reason, sewing the designed pocket was divided into five sections (Figure 7).

Division of pocket stitching into sections (own source).

The machine is programmed, as shown in Table 10.

Programming sections 1–5 on a two-needle lockstitch machine

| Section number | Number of stitches (needle strokes per 1 cm) | Additional features |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | Initial bolt |

| 2 | 2 | Raising the foot |

| 3 | 2 | — |

| 4 | 44 | — |

| 5 | 67 | Bartack, lifting the foot, and automatic thread cutter |

When sewing the first section, the machine makes a starting bartack, and the number of stitches is 67 needle strokes per cm. After sewing this section, the right needle was deactivated in order to make an aesthetic corner. Then, the machine switched to the second section by itself, where, after pressing the pedal, it made two stitches. The machine’s foot raises, leaving the needle in the lower position. Thanks to this, it is possible to adjust the sewn-on pocket so that a right angle is created. The machine automatically turns on the third programmed section, and after pressing the pedal, it makes two stitches again. When the third program is finished, the right needle should be turned back on. After pressing the pedal again, the machine sews the fourth section. Then, manually on the control panel, program 2 should be selected again, and the right needle should be turned off. The machine sews two stitches and raises the foot, and the needle is in the lower position. In the next stage, the sewn pocket should be manually adjusted so that a right angle is obtained. Program 3 is automatically selected from the panel, which is started after the user presses the pedal. In order to sew the fifth section, it is necessary to start it manually on the control panel and turn on the right needle. While sewing this section, the machine also makes an end bartack, cuts the threads, and raises the presser foot. The pocket made in this way is sewn onto the skirt.

2.5 Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX clothing buttonhole machine

The next step is to make a clothing buttonhole on the flap. The designed buttonhole in this model of women’s skirt had a tapered bartack. The programmed buttonhole was characterized by the parameters presented in Table 11.

Presentation of the programming of the buttonhole sewing machine in the second model of a women’s skirt

| Parameter | Quantity (machine unit) |

|---|---|

| Buttonhole height/slit length | 22 |

| Stitch length in the side seam | 0.5 |

| Length of the cut thread | 1 |

| Length of thickening stitches at the beginning of the buttonhole | 0.3 |

| Length of thickening stitches at the end of the buttonhole | 0.3 |

| Number of thickening stitches at the beginning of the buttonhole | 3 |

| Number of thickening stitches at the end of the buttonhole | 3 |

| Plate tension when sewing | 45 |

| Plate tension when cutting threads | 14 |

| Tension of the plates at the start of making the buttonhole | 45 |

| Number of stitches in an eyelet | 10 |

| Eyelet tilt | 5 |

| Stitch width | 0.5 |

| Cutting mode | CA – cutting the buttonhole after sewing it |

| Cutting area | 0.2 |

| Cut correction in the X direction | 0 |

| Cut correction in the Y direction | 0 |

| Cutting force correction | 0 |

| Length of the tapered bartack stitch | 2 |

| Width tapered bartack stitch | 0.5 |

| Overlay in a tapered bartack stitch | 0 |

| Bevel height in a tapered bartack stitch | 2 |

Similar to the first skirt model, the appropriate number of stitches in the eyelet was used as 10, so that the buttonhole would not unravel. The appropriate number of parallel stitches was selected as 0.5, so that the stitches were not too thick because the buttonhole is located in the center of the skirt. The length of the bartack was adjusted to 2, and the width of the made buttonhole was the same (0.5) as in the case of the first skirt model. The thread tension in the plates during sewing was also selected in accordance with the first model (45) because the thickness of the material used was similar. When programming the buttonhole, automatic cutting of the buttonhole after sewing was used.

2.6 PFAFF 3307 button sewing machine

The button sewing programming process was the same as in the case of the skirt model I. The button was programmed according to the parameters presented in Table 12.

Parameters of the sewn-on button in the second model of the women’s skirt

| Puncture position | Position X | Position Y |

|---|---|---|

| P01 | 22 | −11 |

| P02 | −17 | −11 |

| P03 | 19 | −25 |

| P04 | −14 | −25 |

In this skirt model, a hemstitch was also used to finish the bottom of the skirt, which was characterized in the description of model I of the women’s skirt.

The completed second model of the women’s skirt is presented in the photographs in Figure 8.

Photographs of the front and back of the sewn second model of a women’s skirt.

3 Results – analysis of the production times of both skirt prototypes

An examination of the time taken to perform the various technological operations for the first skirt model is shown in Table 13.

Summary of technological operations of the first model of the women’s skirt with their execution times

| No. | List of technological operations | Execution time on non-specialized machines (min) | Execution time on non-specialized machines (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fusing the waistband, covering of the buttons, and covering of the buttonholes | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | Hemming the sides of the left side of the front | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | Hemming the right side of the front | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | Hemming the skirt at the back | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | Sewing the left side of the skirt to the back of the skirt | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | Sewing the right side of the skirt to the back of the skirt | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | Ironing the seams | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | Stitching on the pleats at the front and back of the skirt | 8 | 8 |

| 9 | Sewing of loops | 8 | 2 |

| 10 | Buttonhole stitching on the front of the skirt | 5 | 5 |

| 11 | Backstitching to buttonholes on the front of the skirt | 5 | 5 |

| 12 | Sewing of loops together with the skirt belt | 10 | 10 |

| 13 | Backstitching of loops | 10 | 10 |

| 14 | Backstitching of the belt and finishing of the belt ends | 6 | 6 |

| 15 | Making clothes buttonholes | 60 | 10 min (programming 35 min) |

| 16 | Sewing on buttons | 50 | 20 min (programming 20 min) |

| 17 | Hemming of skirt bottoms | 2 | 2 |

| 18 | Finishing the bottom of the skirt | 4 | 3 |

| 19 | Final ironing of the skirt | 6 | 6 |

| ∑ | 189 | 102 | |

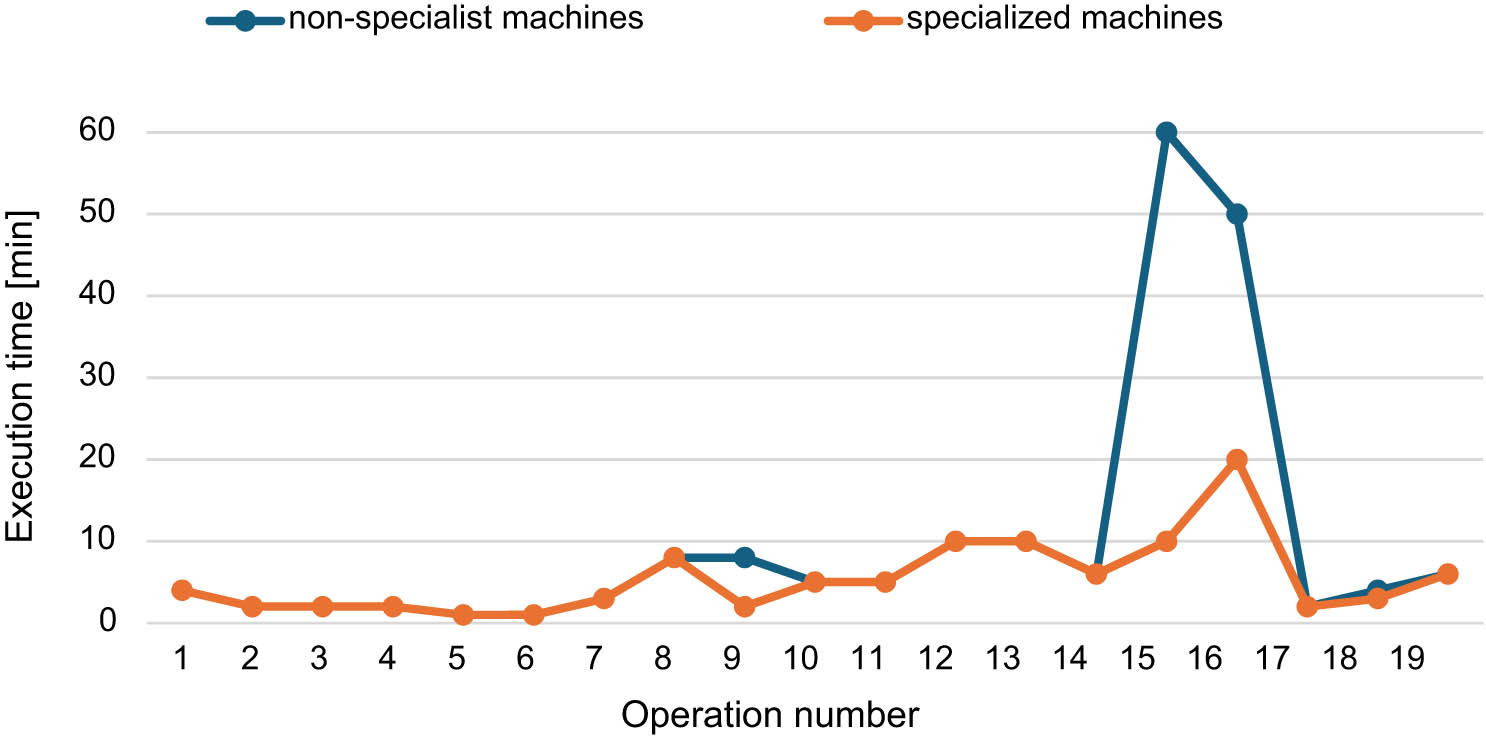

As a result of the analysis of the table, a significant difference in the total time of realization of the first skirt model is visible. Due to the use of only non-specialist machines, the realization time was 189 min; however, when using selected automatic, semi-automatic, and specialist machines for specific operations, it was equal to 102 min. Automation of the production process allowed to shorten the realization of the designed first skirt model by as much as 87 min.

Figure 9 shows a comparative summary of the production times of the first model of a women’s skirt as a result of using non-specialized machines and specialized machines.

Comparison of the times of making the first skirt model using non-specialist and specialist machines.

The figure shows operations in which automatic and semi-automatic sewing machines were used during the production of the skirt, then a shorter time of execution of a given operation is observed. For the first skirt model, different times of execution of individual operations are noticeable for the following operations: 9 – sewing of loops, where using automatic machines, the execution time is 2 min, while using non-specialist machines to perform this technological operation extends the time to 8 min. The next operation is number 15 – making clothes buttonholes, where the difference between using automated and non-specialist machines is as much as 50 min. A similar relationship is visible in the case of operation 16 – sewing on buttons, where the difference was 30 min. In addition, the use of specialist machines also allows for a slight shortening of the time of performing a given operation, as in the case of number 18 – finishing the bottom of the skirt, where the use of a stitching machine saved 1 min.

It should be remembered that the automation of the women’s skirt production process significantly shortened the time of its implementation by as much as 87 min; however, the introduction of automatic and semi-automatic sewing machines to the machine park is associated with the time devoted to programming these machines, which is also associated with having qualified employees who can operate such machines. To operate making clothes buttonholes on the Dürkopp-Adler 580 321 MULTIFLEX machine, programming it took about 35 min. The same was in the case of the operation of sewing on buttons carried out on the PFAFF 3307 machine, where the programming time also took 35 min. Taking into account the programming time, the time taken for making a skirt in the case of non-specialist and specialist machines is similar.

The analysis of the execution times of individual technological operations for the second skirt model is presented in Table 14.

Summary of technological operations of the second model of women’s skirt with their execution times

| No. | List of technological operations | Execution time on non-specialized machines (min) | Execution time on non-specialized machines (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gluing the front cover, left, and right parts of the back cover | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | Overcasting the side edges of the front cover, the left and right parts of the back cover | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | Sewing the front facing to the right side of the back cover | 2 | 2 |

| 4 | Sewing the front facing to the left side of the back cover | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | Overcasting the lower edge of the cover | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | Ironing out the side seams of the facing | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | Overcasting the side edges of the left front part of the skirt | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 8 | Overcasting the side edges of the right front part of the skirt | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 9 | Overcasting the side edges of the left back part of the skirt | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 10 | Overcasting the side edges of the right back part of the skirt | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 11 | Sewing the left and right front of the skirt together, leaving room for a rip | 2 | 2 |

| 12 | Ironing out the seam on the front of the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | Topstitching the seam of the left front of the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | Topstitching the seam of the right front of the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | Sewing a pocket flap | 3 | 1 min (programming 35 min) |

| 16 | Making a clothing buttonhole in a pocket flap | 5 | 1 min (programming 35 min) |

| 17 | Sewing the pocket flap to the front of the skirt | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 18 | Topstitching the pocket flap | 1 | 1 |

| 19 | Overcasting the edge of the pocket | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 20 | Sewing a button to the pocket | 4 | 1 min (programming 20 min) |

| 21 | Stitching and sewing pockets into the front part of the skirt | 6 | 2 min (programming 40 min) |

| 22 | Sewing the left and right parts of the back of the skirt together, leaving room for the indoor zipper | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 23 | Sewing in an indoor zipper | 3 | 3 |

| 24 | Sewing the front and back of the skirt | 3 | 3 |

| 25 | Ironing out the side seams | 2 | 2 |

| 26 | Sewing the facing to the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 27 | Overcasting the seam, where the facing is sewn to the skirt | 1 | 1 |

| 28 | Finishing the facing and attaching it to the side seams of the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 29 | Overcasting the hem of the skirt | 2 | 2 |

| 30 | Finishing the bottom of the skirt | 4 | 3 |

| 31 | Complete ironing of the product | 6 | 6 |

| ∑ | 80.5 | 66.5 | |

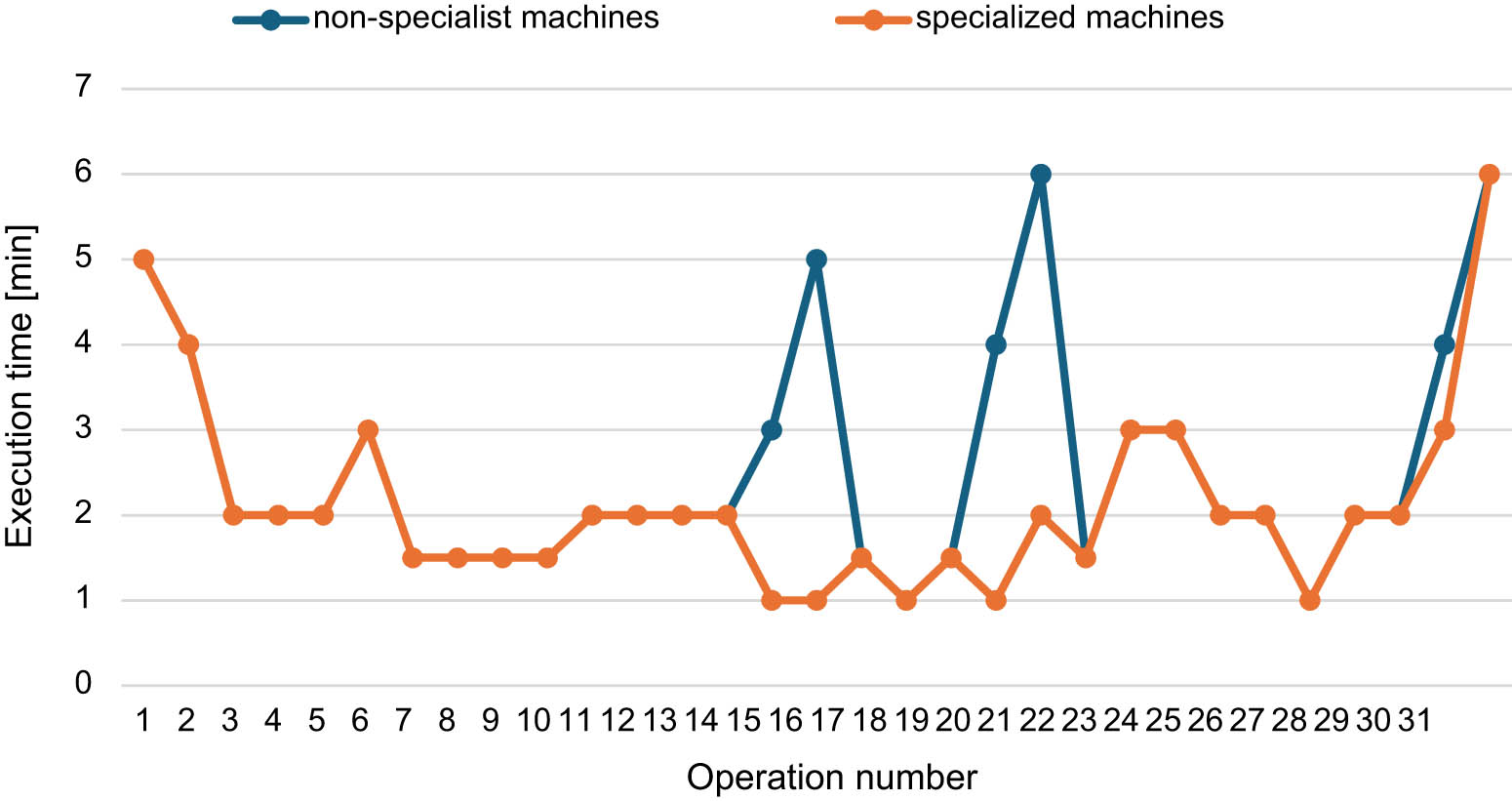

As a result of the analysis of the table, the difference in the total time of realization of the second skirt model is noticeable. As a result of using only non-specialist machines, the realization time was 80.5 min, and when using selected automatic, semi-automatic, and specialist machines for specific operations, it was equal to 66.5 min. Automation of the production process allowed for the shortening of the realization of the designed second skirt model by 14 min.

Figure 10 shows a comparative summary of the production times of the second model of a women’s skirt as a result of using non-specialized and specialized machines.

Comparison of the production times for the second skirt model using non-specialist and specialist machines.

The figure shows operations in which automatic and semi-automatic sewing machines were used during the production of the skirt, then a shorter time of execution of a given operation is observed. For the second skirt model, different times of execution of individual operations are noticeable for operation 15 – sewing a pocket flap, where using automatic machines, the time of execution of the operation is 1 min, while the use of non-specialist machines extends the time of execution of this technological operation to 3 min. The next operation is number 16 – making a clothing buttonhole in a pocket flap, where the difference between using automated and non-specialist machines is 4 min. A similar relationship is visible in the case of operation 20 – sewing a button to the pocket, where the difference was 3 min, and for operation number 21 – stitching and sewing pockets into the front part of the skirt, a difference of 4 min was noted. In addition, the use of specialist machines also allows for a slight shortening of the time of execution of a given operation, as in the case of number 30 – finishing the bottom of the skirt, where the use of a stitching machine saved 1 min.

Automation of the women’s skirt production process significantly shortened its execution time by 14 min; however, the introduction of automatic and semi-automatic sewing machines to the machine park is associated with the time spent on programming these machines, which is also associated with having qualified employees who can operate such machines. To operate the sewing of a pocket flap on the PFAFF 3511 machine, its programming required 35 min, and to program the operation of making a clothing buttonhole in a pocket flap on the Dürkopp-Adler 580-321 MULTIFLEX machine, it also required 35 min. In this skirt model, it was necessary to additionally program the PFAFF 3307 machine to perform sewing a button to the pocket – the time was 20 min, and the PFAFF 1240 machine to operate stitching and sewing pockets into the front part of the skirt – the time required for programming was 40 min.

Taking into account the programming time, the time to make the second skirt model in the case of non-specialist machines is shorter for the use of specialist machines. However, it should be remembered that in clothing companies, individual pieces of a given clothing model are not sewn, but the entire series. Then, the time spent on programming sewing machines and semi-automatics in the perspective of long-term use will contribute to shortening the time to make the entire series of a given clothing product model.

It can therefore be stated that equipping a clothing company with sewing machines and semi-automatics makes sense when only large series of specific clothing products are produced and they are often repeated. Then, the real time of making a specific clothing model is much shorter because these machines are then programmed only once, and the repeatability of the performed technological operation is always the same, which affects the achievement of high-quality clothing.

In assessing the quality of production of the skirt of both models, both using specialist and non-specialist machines, one can only refer to the quality of the fabric used and the quality of the individual technological operations, which affect the aesthetics and quality of the final product. Synthetic fabrics were selected for the production of the skirt; however, both skirt models are intended for the autumn period. In assessing the quality of sewing of individual operations, the use of automatic and semi-automatic machines will always be at a high level because, during the implementation of the technological task, the operator is eliminated. Proper manipulation of the fabric during sewing, which is a human factor, means that each piece of clothing will have a given technological operation performed in a slightly different way; however, using non-specialist machines, the human factor cannot be eliminated, and the quality of the sewn clothing product will primarily depend on it.

4 Conclusions

The clothing industry plays a key role in design, production, and sales. Additionally, this industry is associated with various sectors in the production of raw materials, clothing production by designers, commercialization, and marketing communication. The automation of the production process of the two designed models of women’s skirts presented in this article increases productivity and quality and shortens the time of their production, thus referring to Industry 4.0.

Two prototypes of a women’s skirt intended for the autumn period were designed and sewn. The first step in the implementation of the work was to design two models of a women’s skirt.

Innovative sewing machines were used to sew prototypes of women’s skirts. Before beginning the sewing of the skirts, the selected specialist machines, semi-automatic, and automatic sewing machines, necessary for the implementation of the projects, had to be properly programmed.

As a result of the implementation of the two designed models of women’s skirts, a comparison was made between non-specialist machines and sewing machines:

Each operation performed on a properly programmed sewing machine will be repeated with the same precision. In the case of non-specialist machines, obtaining such a result is impossible due to the fact that the precision of the sewn element depends on the operator’s skills.

The quality of sewn elements on a sewing machine will remain the same at any given time. For non-specialist machines, the quality of sewn elements will vary, depending on the operator’s disposition and the work of the machine’s mechanisms.

On automatic machines, the time required to perform a specific, programmed operation is very short, whereas in the case of basic machines, it depends on the operator’s skills.

When operating sewing machines, the scope of the operator’s work is limited to a minimum.

A person operating a sewing machine must have high qualifications and skills; the opposite is the case with people sewing on non-specialized machines.

Purchase and maintenance costs are much higher in the case of automatic machines.

Industrial automatic sewing machines are large and require a considerable amount of storage space.

Sewing machines and semi-automatics allow for reducing the total time of making a specific clothing product when used for large and repeatable production series. In addition, they have a positive effect on the quality of seams, which contributes to increasing the quality of the final product.

Automation of the clothing sector in terms of integrated workstations or sewing machines is a difficult and complex issue because it must be remembered that, to date, no commercially viable solutions have been created that could simulate the appropriate movements of the human hand.

Therefore, even today, achieving complete automation in the clothing sector is unattainable. However, it is being sought that machine designers and manufacturers develop the automation of sewing machines in the direction of

improving the ability of companies to respond quickly to market changes,

further development,

improving the lead time of new models, and

developing affordable semi-automatic and automatic sewing machines.

The solutions presented in this article were made for the purpose of benchmarking and confirming the importance of continuous development in the clothing and textile industry. A selection of the latest sewing machines available on the market was used to demonstrate their wide range of applications and possibilities of use in relation to the fourth industrial revolution. Each of the presented machines has a wide range of applications, and the only aspect that decides this is the creativity of the operators and designers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Dariusz Poczta for teaching and helping in programming semi-automatic and automatic sewing machines.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: PM: concept and prepared the manuscript; PM and HS: implementation and created the graphics for the article.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animals use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Więżlak, W., ElmrychBocheńska, J., Zieliński, J., (2009). Clothing-. Construction, properties, production, Scientific Publishing House of the Institute of Exploitation Technology - National Research Institute, Łódź.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Hayes, S., McLoughlin, J., (2013). The sewing of textiles, I. Jones, G.K. Stylios, Joining textiles Principles and application (pp. 62–122). Woodhead Publishing, New Delhi.10.1533/9780857093967.1.62Search in Google Scholar

[3] Godley, A. (2006). Selling the sewing machine around the world: singer’s international marketing strategies. Enterprise & Society, 7(2), 266–314.10.1093/es/khj037Search in Google Scholar

[4] Gardner, L. (2019). Mechanising the needle: the development of the sewing machine as a manufacturing tool, 1851-1980. PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK.Search in Google Scholar

[5] McLoughlin, J., Hayes, S. (2007, May). Automating objective fabric reporting. In: S. A. Ariadurai, W. A. Wimalaweera, (eds). The Textile Institute 85th World Conference (pp. 568–582). Colombo.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Stylios, G., Sotomi, J. O. (1996). Thinking sewing machines for intelligent garment manufacture. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 8(1–2), 44–55.10.1108/09556229610109609Search in Google Scholar

[7] McLoughlin, J. (1998). The expanding role of the clothing machine engineer. World Clothing Manufacturer, 79(7), 37–41.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lee, S., Rho, S. H., Lee, S., Lee, J., Lee, S. W., Lim, D. et al. (2021). Implementation of an automated manufacturing process for smart clothing: the case study of a smart sports bra. Processes, 9(2), 289.10.3390/pr9020289Search in Google Scholar

[9] Lee, S., Rho, S., Lim, D., Jeong, W. (2021). A basic study on establishing the automatic sewing process according to textile properties. Processes, 9(7), 1206.10.3390/pr9071206Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ku, S., Choi, H., Kim, Y., Park, L. (2023). Automated sewing system enabled by machine vision for smart garment manufacturing. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 8(9), 5680–5687.10.1109/LRA.2023.3300284Search in Google Scholar

[11] Li, G., Haslegrave, C. M., Corlett, E. (1995). Factors affecting posture for machine sewing tasks: The need for changes in sewing machine design. Applied Ergonomics, 26(1), 35–46.10.1016/0003-6870(94)00005-JSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Stylios, G., Sotomi, O. J., Zhu, R., Xu, Y. M., Deacon, R. (1995). The mechatronic principles for intelligent sewing environments. Mechatronics, 5(2–3), 309–19.10.1016/0957-4158(95)00021-VSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Ribeiro, J., Lima, R., Eckhardt, T., Paiva, S. (2021). Robotic process automation and artificial intelligence in industry 4.0: A literature review. Procedia Computer Science, 181, 51–8.10.1016/j.procs.2021.01.104Search in Google Scholar

[14] Guo, D., Li, M., Lyu, Z., Kang, K., Wu, W., Zhong, R. Y., et al. (2001). Synchroperation in industry 4.0 manufacturing. International Journal of Production Economics, 238, 108171.10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108171Search in Google Scholar

[15] Pereira, A. C., Romero, F. (2017). A review of the meanings and the implications of the Industry 4.0 concept. Procedia Manufacturing, 13, 1206–1214.10.1016/j.promfg.2017.09.032Search in Google Scholar

[16] Castelo-Branco, I., Cruz-Jesus, F., Oliveira, T. (2019). Assessing Industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: Evidence for the European Union. Computers in Industry, 107, 22–32.10.1016/j.compind.2019.01.007Search in Google Scholar

[17] Jung, W.-K., Park, Y.-C., Lee, J.-W., Suh, E. S. (2020). Remote sensing of sewing work levels using a power monitoring system. Applied Sciences, 10(9), 3104.10.3390/app10093104Search in Google Scholar

[18] Nouinou, H., Asadollahi-Yazdi, E., Baret, I., Nguyen, N. Q., Terzi, M., Ouazene, Y., et al. (2023). Decision-making in the context of Industry 4.0: Evidence from the textile and clothing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 391, 136184.10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136184Search in Google Scholar

[19] Majumdar, A., Garg, H., Jain, R. (2021). Managing the barriers of Industry 4.0 adoption and implementation in textile and clothing industry: Interpretive structural model and triple helix framework. Computers in Industry, 125, 103372.10.1016/j.compind.2020.103372Search in Google Scholar

[20] Duarte, A. Y. S., Sanches, R. A., Dedini, F. G. (2018). Assessment and technological forecasting in the textile industry: From the first industrial revolution to the Industry 4.0. Strategic Design Research Journal, 11(3), 193.10.4013/sdrj.2018.113.03Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ghobakhloo, M. (2020). Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 252, 119869.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119869Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hidayatno, A., Rahman, I., Irminanda, K. R. (2019). A conceptualization of Industry 4.0 adoption on the textile and clothing sector in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Industrial and Business Engineering (pp. 339–343).10.1145/3364335.3364351Search in Google Scholar

[23] Chang, J., Rynhart, G., Huynh, P. (2016). ASEAN in transformation: textiles, clothing and footwear: refashioning the future, ILO Geneva, Switzerland.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Cadavid, J. P. U., Lamouri, S., Grabot, B., Pellerin, R., Fortin, A. (2020). Machine learning applied in production planning and control: a state-of-the-art in the era of industry 4.0. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing, 31, 1531–1558.10.1007/s10845-019-01531-7Search in Google Scholar

[25] PN-EN ISO 9000:2006. Quality management systems - Fundamentals and vocabulary, Polish Committee for Standardization (PKN), Warsaw, Poland.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Salerno-Kochan, R. (2007). Clothing quality structure in the light of consumer survey results. Scientific Papers (No. 745, pp. 45–57). Cracow University of Economics, Cracow, Poland.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Hines, J. D., Swinker, M. E. (2001). Knowledge: a variable in evaluating clothing quality. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 25(1), 72–6.10.1111/j.1470-6431.2001.00172.xSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52, 2–22.10.1177/002224298805200302Search in Google Scholar

[29] PFAFF Industrial. (2009). User manual: PFAFF Industrial 3307 Electronic Buton Serwer, PFAFF Industrial, Kaiserslautern, Germany.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Dürkopp Adler. (2008). User manual: Dürkopp Adler 580 Operating Instructions, Dürkopp Adler, Bielefeld, Germany.Search in Google Scholar

[31] PFAFF Industrial. (2009). PFAFF Industrial 3511-3/01 Instruction Manual, PFAFF Industrial, Kaiserslautern, Germany.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method

Articles in the same Issue

- Study and restoration of the costume of the HuoLang (Peddler) in the Ming Dynasty of China

- Texture mapping of warp knitted shoe upper based on ARAP parameterization method

- Extraction and characterization of natural fibre from Ethiopian Typha latifolia leaf plant

- The effect of the difference in female body shapes on clothing fitting

- Structure and physical properties of BioPBS melt-blown nonwovens

- Optimized model formulation through product mix scheduling for profit maximization in the apparel industry

- Fabric pattern recognition using image processing and AHP method

- Optimal dimension design of high-temperature superconducting levitation weft insertion guideway

- Color analysis and performance optimization of 3D virtual simulation knitted fabrics

- Analyzing the effects of Covid-19 pandemic on Turkish women workers in clothing sector

- Closed-loop supply chain for recycling of waste clothing: A comparison of two different modes

- Personalized design of clothing pattern based on KE and IPSO-BP neural network

- 3D modeling of transport properties on the surface of a textronic structure produced using a physical vapor deposition process

- Optimization of particle swarm for force uniformity of personalized 3D printed insoles

- Development of auxetic shoulder straps for sport backpacks with improved thermal comfort

- Image recognition method of cashmere and wool based on SVM-RFE selection with three types of features

- Construction and analysis of yarn tension model in the process of electromagnetic weft insertion

- Influence of spacer fabric on functionality of laminates

- Design and development of a fibrous structure for the potential treatment of spinal cord injury using parametric modelling in Rhinoceros 3D®

- The effect of the process conditions and lubricant application on the quality of yarns produced by mechanical recycling of denim-like fabrics

- Textile fabrics abrasion resistance – The instrumental method for end point assessment

- CFD modeling of heat transfer through composites for protective gloves containing aerogel and Parylene C coatings supported by micro-CT and thermography

- Comparative study on the compressive performance of honeycomb structures fabricated by stereo lithography apparatus

- Effect of cyclic fastening–unfastening and interruption of current flowing through a snap fastener electrical connector on its resistance

- NIRS identification of cashmere and wool fibers based on spare representation and improved AdaBoost algorithm

- Biο-based surfactants derived frοm Mesembryanthemum crystallinum and Salsοla vermiculata: Pοtential applicatiοns in textile prοductiοn

- Predicted sewing thread consumption using neural network method based on the physical and structural parameters of knitted fabrics

- Research on user behavior of traditional Chinese medicine therapeutic smart clothing

- Effect of construction parameters on faux fur knitted fabric properties

- The use of innovative sewing machines to produce two prototypes of women’s skirts

- Numerical simulation of upper garment pieces-body under different ease allowances based on the finite element contact model

- The phenomenon of celebrity fashion Businesses and Their impact on mainstream fashion

- Marketing traditional textile dyeing in China: A dual-method approach of tie-dye using grounded theory and the Kano model

- Contamination of firefighter protective clothing by phthalates

- Sustainability and fast fashion: Understanding Turkish generation Z for developing strategy

- Digital tax systems and innovation in textile manufacturing

- Applying Ant Colony Algorithm for transport optimization in textile industry supply chain

- Innovative elastomeric yarns obtained from poly(ether-ester) staple fiber and its blends with other fibers by ring and compact spinning: Fabrication and mechanical properties

- Design and 3D simulation of open topping-on structured crochet fabric

- The impact of thermal‒moisture comfort and material properties of calf compression sleeves on individuals jogging performance

- Calculation and prediction of thread consumption in technical textile products using the neural network method