Abstract

Multilayer adhesive bonded structures/materials (MABS) are widely used as structural components, especially in the field of aerospace. However, for MABS workpieces, the facts that the weak echo of the deep interfacial debonding defects (DB) caused by the large acoustic attenuation coefficient of each layer and this echo, which generally aliases with the excitation wave and the backwall echo of the surface layer, pose a great challenge for the conventional longitudinal wave ultrasonic nondestructive testing methods. In this work, an ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial DBs of MABS is proposed based on the ultrasonic resonance theory and the aliasing effect of ultrasonic waves in MABS. Theoretical and simulation analysis show that the optimal inspection frequency for II-interfacial DBs is 500 kHz when the shell thickness is 1.5 mm and the ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) thickness is 1.5 mm, and the optimal inspection frequency is 250 kHz when the shell thickness is 1.5 or 2.0 mm and the EPDM thickness is 2.0 mm. Verification experiments show that the presence of a DB in the II-interface causes a resonance effect, and in the same inspection configuration, the larger the defect size, the more pronounced this effect is. This resonance effect manifests itself as an increase in the amplitude and an increase in the vibration time of the A-scan signal as well as a pronounced change in the frequency of the received ultrasonic wave. In addition, the increase in the excitation voltage further highlights the ultrasonic resonance effect. Four imaging methods – the integrations of the signal and the signal envelope curve, the maximum amplitude of the fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the signal, and the signal energy – were used for C-scan imaging of ultrasonic resonance evaluation of MABS’s deep interfacial DBs and all these methods can clearly show the sizes and locations of the artificial defects and internal natural defect. The normalized C-scan imaging method proposed in this study can further highlight the weak changes in the signals in the C-scan image. The research results of this study have laid a solid theoretical and practical foundation for the ultrasonic resonance evaluation of MABS.

1 Introduction

Multilayer adhesive bonded structure (MABS) has many advantages, such as high specific strength, fatigue resistance, corrosion resistance, and good heat insulation, and is widely used in aerospace and nuclear power fields. For example, solid rocket motor is usually a multilayer structure, in order to make sure the combustion of propellant develops in booked way and prevent the rocket motor from being damaged by the high-temperature nozzle jet, the propellant inside the shell is usually covered by one or more layers of coating (generally consist of insulation layer and liner). The adhesive bonding quality of MABS is affected by humidity, temperature, curing time, and other factors in the manufacturing process, as well as vibration, alternating temperature, and alternating load during storage [1,2]. These inevitable factors can easily lead to porosity, cracks, poor adhesion (“kissing” bonds), and even delamination damage on the bonding surface of multilayer adhesively bonded components [3,4]. Therefore, non-destructive testing of MABS has become a necessary process to ensure manufacturing quality [5,6].

Over the years, ultrasonic non-destructive evaluation for the bonded structures has attracted widespread attention from researchers. Time domain ultrasonics, lamb-wave, ultrasonic impedance and spectroscopy, sonic vibration, and also constant-frequency ultrasonic phase method are applicable for the nondestructive detection of voids, delamination, porosity, cracks, or poor adhesion [7,8,9]. Ultrasonic pulsed echo technology is used to detect debonding defects (DBs) in aluminum-carbon fiber reinforced plastic bonded structures [10]. This inspection method is effective for bonded structures with only two layers, but in the case of inspecting parts from the metal side, the inspection of defect will be more complicated if the defect location in the adhesive is deeper. Jinhao made three kinds of bonded states of ultra-thin metal-silica gel bonding structure, the well-bonded, weakly bonded and debonding composite parts, and established the law between the bonding state with the binding coefficient based on the high-frequency ultrasonic resonance method, and found that the bonding coefficient decreases with the weakening of the bonding strength [11]. Xingguo derives the expressions of the transmission coefficient and the reflection coefficient from longitudinal wave and shear wave in the layered medium by the spring model and the boundary conditions at two interfaces based on the transfer matrix method. The oblique incidence transmission ultrasonic detection method was used to carry out confirmatory experiment, and the numerical solution results were basically consistent with the experiment, which provides a theoretical basis for the ultrasonic detection of the interface quality of composite bonded structures [5]. Sahoo evaluates the adhesive bonded interfaces of GFRP-nitrile-based rubber bonded structure by low frequency single sided portable nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technique and compares it with X-ray radiography and ultrasonic (acousto-ultrasonic) methods. NMR can effectively identify the DBs and also enable quantitative measurement of airgap thickness [12]. Elena developed a novel signal post-processing algorithm for reconstruction of the joint area to inspect defect in hybrid metal to composite joints where the metal part has pin arrays [13].

However, for MABS, the large reflectivity and attenuation of ultrasonic energy [14,15] and the presence of aliasing echo waves [16] make the detection of deep interfacial DBs in MABS more difficult. Spytek et al. presented a framework for the evaluation of DBs in adhesively bonded multilayer plates through local wavenumber estimation. And the effectiveness of the method was verified by experiments on a three-layer sample made of different thicknesses of aluminum (bonded by an epoxy adhesive) [4]. Guo proposed a defect identification method based on wavelet packet transform (WPT) and machine learning, which first uses WPT to extract the corresponding energy characteristic signals of different interface DBs, and then uses the obtained energy characteristics as the input vector of the machine learning algorithm (K-nearest neighbor, random forest, and support vector machine) for classification and identification. The accuracy of DBs classification is as high as 95.33% [17]. Loukkal conducted a numerical study on the influence of the properties of different interface layers on guided ultrasonic waves, and deeply analyzed the impact of the adhesive interface layer nature on the reflection coefficient magnitude and the variation law of guided wave dispersion curves, so as to characterize the interface quality in multilayer structures [18]. In order to reduce the impact of high attenuation and aliasing of ultrasonic waves on non-destructive testing of multilayer structures, Baiqiang established a high-power ultrasonic pulse echo detection system, and used the wavelet transform method to extract the characteristic parameters that can represent the sizes and positions of the defect [19].

This study comprehensively analyzes the ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial DBs in MABS based on the ultrasonic resonance theory and the aliasing effect of ultrasonic waves in MABS. The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical basis of ultrasonic resonance evaluation method. Section 3 is a numerical analysis of acoustic properties of MABS. Experimental studies on ultrasonic resonance evaluation of multilayer material structure are presented in Section 4. A Summary is provided in Section 5.

2 Theoretical basis of ultrasonic resonance evaluation method

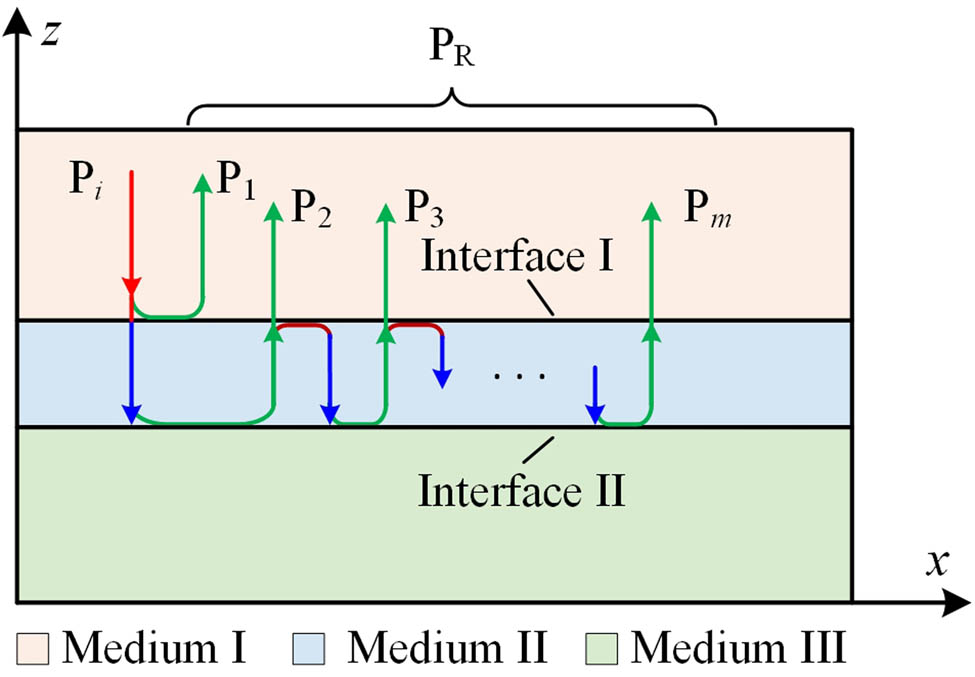

During ultrasonic wave propagation, reflection and transmission occur at the interface between the two materials, accompanied by changes in signal amplitude and phase. When the thicknesses of the mediums on both sides of the interface are much greater than the wavelengths in them, the reflectivity and transmittance are determined by the acoustic impedances of the mediums. In the bonding structure, if there is an adhesive layer between the two media, when the thickness of the adhesive layer is much smaller than the ultrasonic wavelength inside it, the influence of the adhesive layer on the ultrasonic propagation law can be ideally ignored [20]. Therefore, this study will ignore the influence of the adhesive layer and analyze the ultrasonic propagation law in the three-layer medium. As shown in Figure 1, assume that the ultrasonic sound pressure

Schematic diagram of ultrasonic propagation in layered model.

where

The reflection coefficient of the sound pressure of medium 2 can be expressed as

The amplitude and phase of the reflection coefficient of the sound pressure can be expressed as

As can be seen from the above equation, when

3 Numerical analysis of acoustic properties of MABS

In Section 2, the ultrasonic propagation model in MABSs was briefly analyzed, but there are many factors affecting the ultrasonic propagation law in MABSs, and it is very difficult to establish an accurate ultrasonic propagation mathematical model. This section reveals the main propagation laws of ultrasonic waves in an ideal model of MABS by the finite element method.

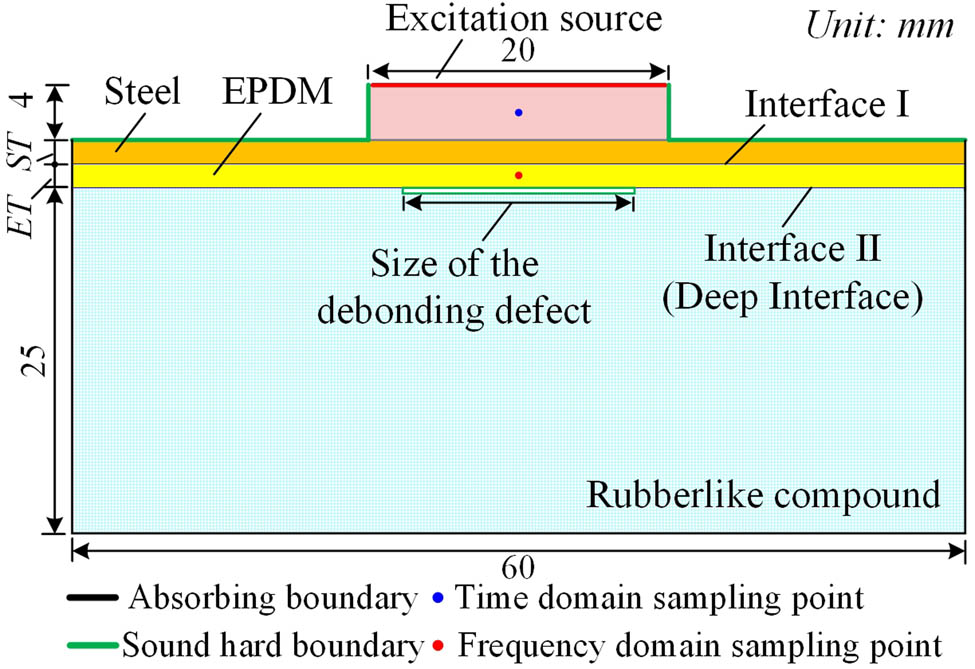

Three finite element models of multilayer bonded structures were established according to the actual situation using COMSOL multiphysics software. All the models consist of three different layers of materials, the first of which is high-strength steel with thickness of 1.5 mm or 2.0 mm (ST: thickness of the steel layer); the second layer is ethylene propylene diene monomer (EPDM) with thickness of 1.5 or 2.0 mm (ET: thickness of the EPDM layer); the third layer is a rubber-like composite material with a thickness of 25 mm (RT: thickness of the rubber-like composite material layer). Considering the symmetry of the model, the three-dimensional problem is simplified to a two-dimensional problem to reduce the amount of computation. The geometry of the multilayer adhesive bonded material and the boundary condition settings are shown in Figure 2. And a 4 mm bulge on the model is used to simulate the ultrasonic wedge of the actual inspection. For different scenarios in the frequency domain and time domain, frequency domain sampling point (FSP) and time domain sampling point (TSP) are set in different areas of the model. Frequency domain analysis is mainly to obtain the frequency response of the second layer, so the FSP is set in the second layer of the structure. The time domain analysis is mainly to obtain the change process of the ultrasonic signal during the whole detection process, so the TSP is set in the wedge region of the structure model.

The geometry of the MABS.

3.1 Analysis of frequency domain characteristics

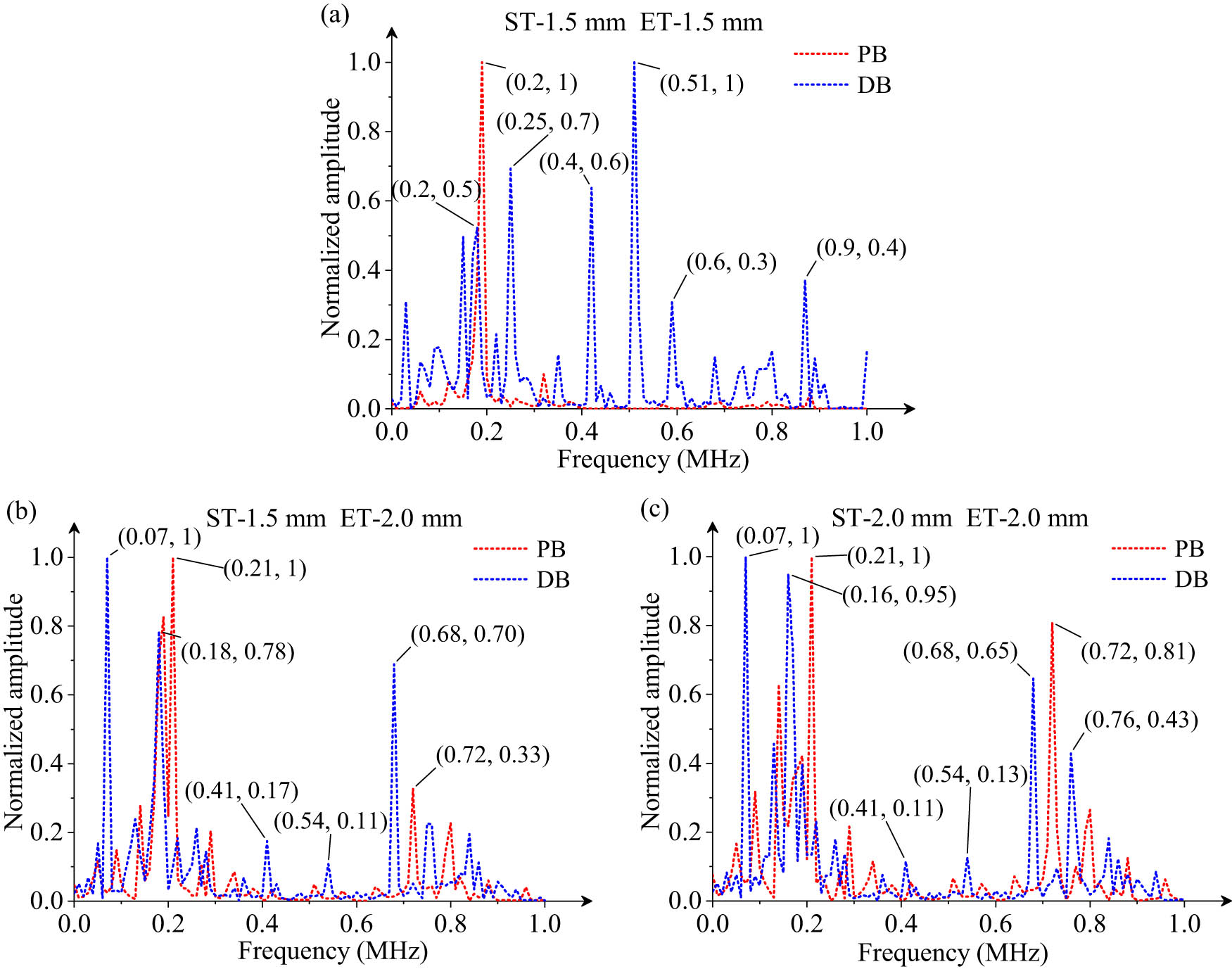

Frequency domain analysis is mainly to obtain modal parameters of a structure, such as vibration frequencies, mode shapes, and damping. Vibration frequencies and mode shapes are the intrinsic properties of a structure, depending on stiffness and mass of the structure and their distributions. DBs changes the original stiffness and mass state of a structure and hence resulting in differences in vibration frequencies and mode shapes between defect-free structure and structures that contain defects or have been damaged [7]. Therefore, three sizes finite element models were established using the Solid Mechanics Module in COMSOL, in which the STs and ETs are 1.5 and 1.5 mm, 1.5 and 2.0 mm, and 2.0 and 2.0 mm, respectively, for frequency domain analysis. And each model includes two cases of debonding defect (DB) and perfect bond (PB).

Given the fact that the frequency of ultrasonic resonance evaluation in actual engineering is usually lower than 1 MHz, the frequency range of the solution is set to 0.01–1 MHz during the finite element simulation, and the step size is set to 0.01 MHz. The maximum grid size is set to 0.3 mm. The frequency response curves at the FSPs for DB and PB cases of the three size models were extracted, as shown in Figure 3. For readability, the amplitudes of these curves are normalized.

Frequency response curves of MABS models. (a) ST-1.5 mm, ET-1.5 mm, (b) ST-1.5 mm, ET-2.0 mm, and (c) ST-2.0 mm, ET-2.0 mm.

As can be seen from Figure 3(a), for a sample with ST and ET of 1.5 and 1.5 mm, respectively, the frequency response at the sampling point is mainly around 200 kHz when PB. However, when there is a defect in the interface II of the model, the frequency response changes significantly, and the response curve appears multiple peaks at frequencies 200, 250, 400, 510 kHz, etc. The maximum peak occurs at 510 kHz, that is, 510 kHz is the optimal frequency for detecting defects in the II-interface for a workpiece with this size. Generally, ultrasonic transducer/probe has a certain bandwidth, so ultrasonic probe with a frequency of 500 kHz is recommended for engineering inspection of MABS of this size. Similarly, for the sample of ST and ET of 1.5 and 2.0 mm, respectively, Figure 3(b), the maximum amplitude is at 70 kHz. And for the sample of ST and ET of 2.0 and 2.0 mm, respectively, Figure 3(c), the maximum amplitude is also at 70 kHz. In addition, both the frequency response curves of the latter two sizes of DB models have sub-peaks around 180 kHz and considering the detection accuracy and the bandwidth of the commercial probe, it is recommended to use a 250 kHz probe for the inspection experiments.

3.2 Analysis of time domain characteristics

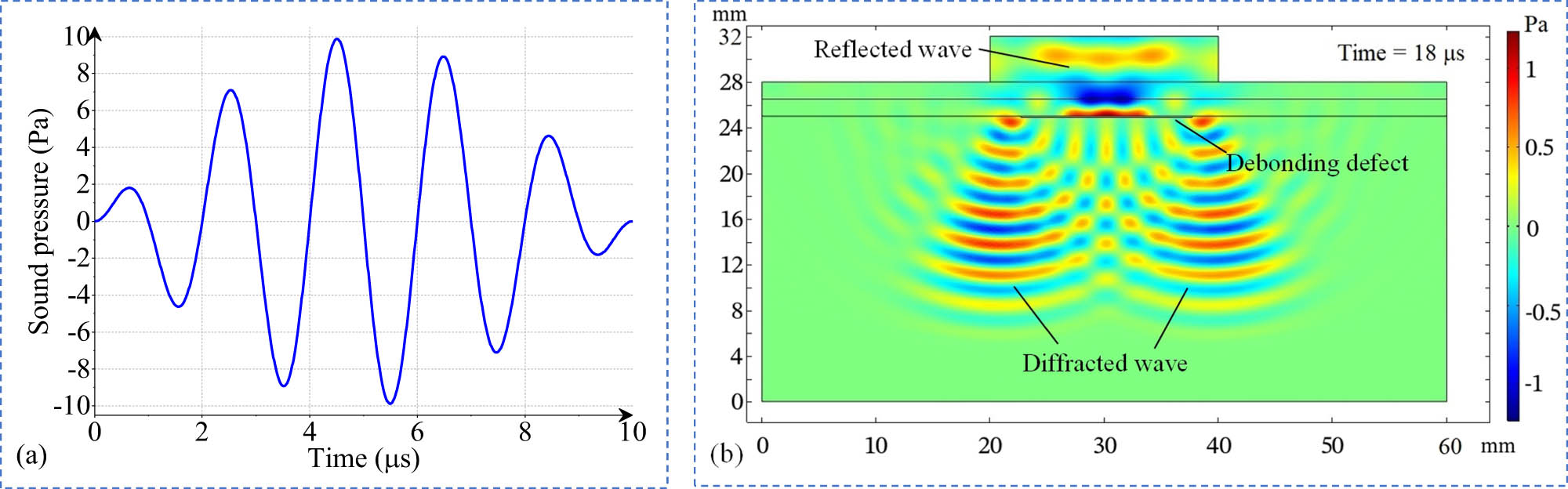

For the analysis of time domain characterization, a multi-physics model with ST and ET of 1.5 and 1.5 mm was established using the “Pressure Acoustics, Transient” interface in COMSOL. The boundary conditions for this model are shown in Figure 2. The ultrasonic excitation signal is a single-frequency sinusoidal signal (500 kHz, 5 cycles) modulated by the Hanning window, as shown in Figure 4(a). Because this signal can effectively suppress the frequency dispersion phenomenon of ultrasonic wave, eliminate high-frequency interference and energy spectrum leakage problems, and the modulation signal has a large bandwidth and high longitudinal resolution compared to the sine wave signal, a better excitation signal is ensured. By solving the transient solution of the established finite element model, the progressive propagation process of ultrasonic waves in the model can be observed. The internal sound pressure distribution of the model at 18 μs is shown in Figure 4(b). The reflected and diffracted waves of the defect are clearly depicted in the image.

Excitation signal (a) and sound pressure distribution inside the MABS model (b).

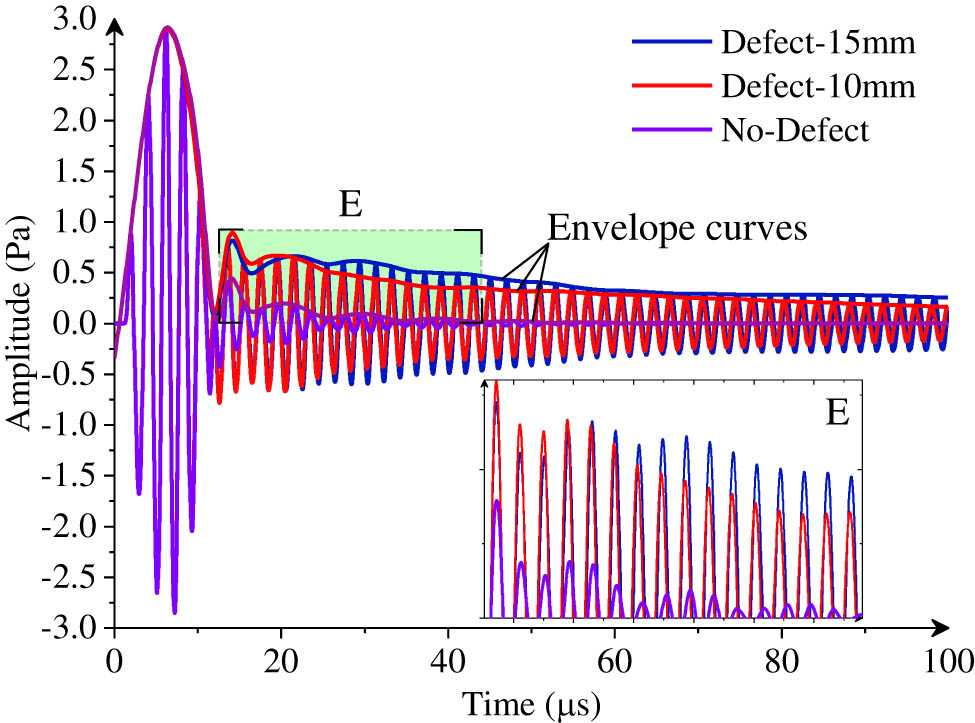

For a more detailed time domain signal, time domain responses at TSP with defect sizes of 15, 10 mm, and defect-free are extracted, as shown in Figure 5. On the time axis, ultrasonic waves within about 12 μs are the initial arrival waves (excitation waves). For this simulation model, ultrasonic waves after 12 μs is the region of interest. The upper envelope curves of the three ultrasonic waves and the local enlarged view clearly show that the signal is attenuated to an indistinguishable level in a short time when there is no defect, and that the amplitude of the ultrasonic signal in the period of interest becomes larger and the oscillation time becomes longer due to resonance and reflection when the model contains a DB.

Ultrasound signals in time domain under different defect sizes.

4 Experimental studies on ultrasonic resonance evaluation of MABS

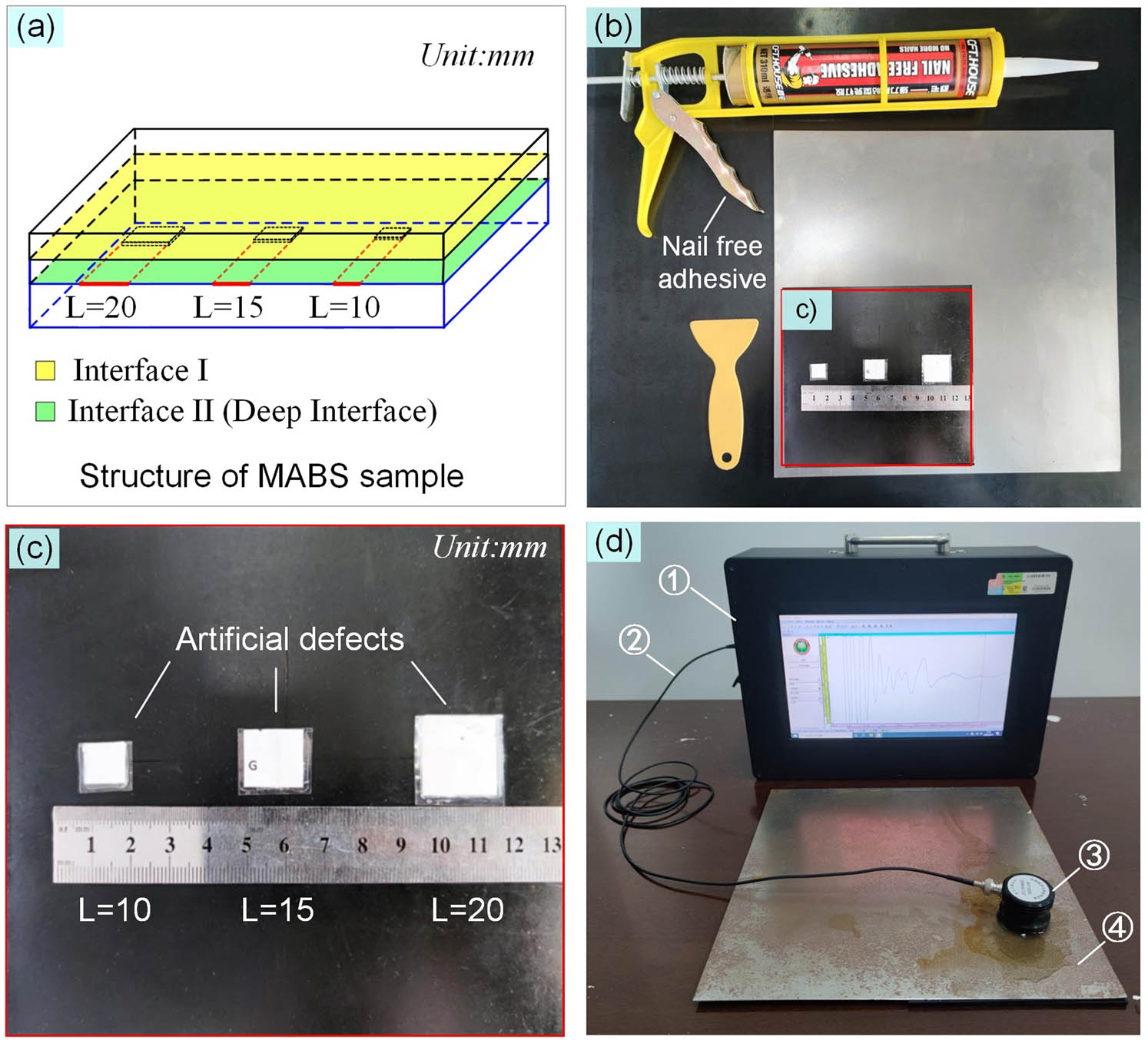

4.1 Production of artificial defect samples and the ultrasonic instrument

The materials and parameters of the artificial defect samples are consistent with the actual products. All the three artificial defect samples are made by bonding three layers of materials, the materials are steel, EPDM, and one type of rubber-like composite material. The STs and ETs of these samples are 1.5 and 1.5 mm (Sample A), 1.5 and 2.0 mm (Sample B), 2.0 and 2.0 mm (Sample C), respectively. The RTs of all the samples are 3 mm. The production of the first size artificial defect sample and the ultrasonic instrument is shown in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6(a), there are two interfaces between the three layers of this structure. The interface between the first layer of material and the second layer of material is called interface I. The interface between the second layer of material and the third layer of material is called interface II. Interface II and the interfaces below it can generally be called the deep interfaces. Three artificial defects (L = 10 mm, L = 15 mm, L = 20 mm in size) are placed between the second and third layers, as shown in Figure 6(a)–(c). Artificial defects are three-layer printer papers bonded by packaging tape. Figure 6(d) is the portable ultrasonic instrument used for these evaluation experiments. The remaining two sizes of artificial defect samples are made using the same process.

Production of artificial defect sample and the ultrasonic instrument. (a) The structure of artificial defect sample, (b) The manufacturing process of artificial defect sample, (c) The sizes of the artificial defects, and (d) Configuration of the test experiment, ① Portable ultrasonic testing instrument, ② coaxial cable, ③ ultrasonic transducer (ultrasonic probe), and ④ artificial defect sample.

4.2 Validation experiments and analysis of A-scan signals

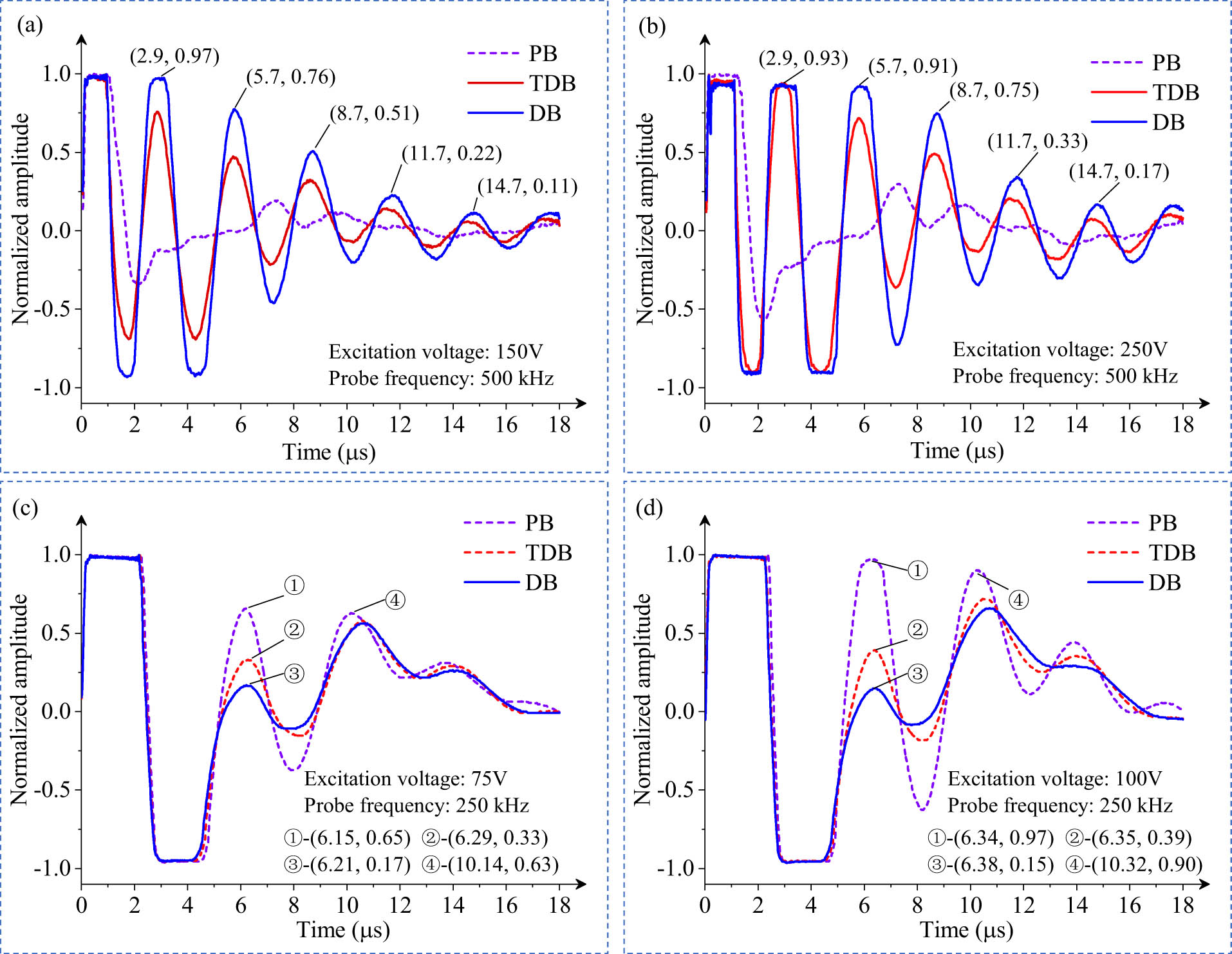

In this section, verification experiments for deep interfacial debonding defects based on ultrasonic resonance effect are carried out first. In these experiments, Sample A was first subjected to ultrasonic nondestructive testing. Section 3.1 shows that the optimal inspection frequency for sample A is 500 kHz and an amplitude value of 0.7 is also present at 250 kHz, so, two ultrasonic transducers of 500 and 250 kHz are used for these experiments. Ultrasonic signals in three conditions and two excitation voltages are acquired by the instrument. The three conditions are: the transducer is located in the area of PB, half of the transducer is in the area of PB and half is in the area of DB (transition area of DB, TDB), and the transducer is completely above the DB. When using the 500 kHz ultrasonic transducer, the excitation voltages are set to 150 and 250 V, respectively. When using the 250 kHz ultrasonic transducer, as the frequency reduction reduces the attenuation coefficient of the ultrasonic wave, the excitation voltage is set to 75 and 100 V, respectively. A-scan signals of Sample A under these different conditions are shown in Figure 7.

Scan signals for sample A under different conditions. PB – perfect bond, TDB – transition area of DB, DB – debonding defect. (a) Excitation voltage 150 V, frequency 500 kHz, (b) Excitation voltage 250 V, frequency 500 kHz, (c) Excitation voltage 75 V, frequency 250 kHz, and (d) Excitation voltage 100 V, frequency 250 kHz.

As can be seen from Figure 7(a) and (b), both sets of curves have the same trend. There is no resonance effect in the PB area, and the A-scan signal has almost no complete vibration cycle. There is a visible resonance effect in both the TDB and DB regions, the A-scan signals have a significant vibration for more than five cycles. And the closer the transducer is to the defect center or the greater the excitation voltage, the greater the resonance amplitude. Specifically, the amplitude of the fourth cycle of the A-scan signal at an excitation voltage of 250 V and the amplitude of the third cycle at an excitation voltage of 150 V are basically equal. That is to say, as the excitation voltage increases, the amplitude of the A-scan signal becomes larger and the vibration time is longer. This feature is very helpful for engineers to determine whether there is a deep interfacial debonding defect. However, when we focus on Figure 7(c) and (d), a completely opposite phenomenon emerges. There is a visible resonance effect in the PB region, and the closer the transducer is to the defect center or the lower the excitation voltage, the lower the resonance amplitude. This is because as the frequency decreases, the ultrasonic wavelength becomes longer, and these waves penetrate directly through the material of the second layer to the backwall of the third layer (thickness 3 mm), causing a resonance effect throughout sample A. This novel phenomenon provides a new perspective for the inspection of ultra-thin MABS parts.

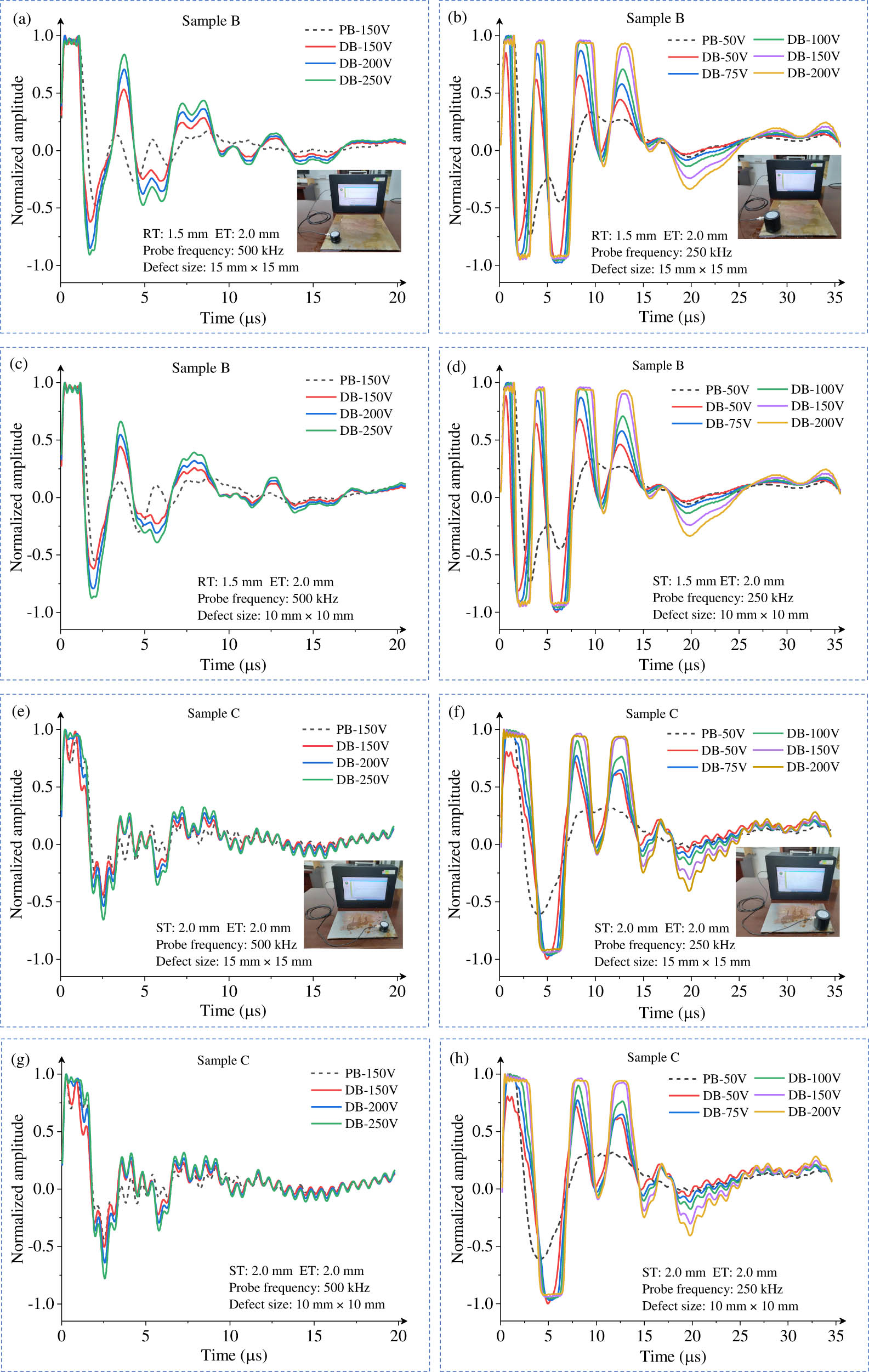

Experiments on the universality of the method were then carried out. Samples B and C were used to perform the experiments. As can be seen from Section 3.1, the recommended detection frequency for samples B and C is 250 kHz. As can be seen in Figure 3(b) and (c), there are two small peaks at 410 and 540 kHz, so the 500 kHz ultrasonic probe was used to perform the corresponding comparison experiments. In these experiments, A-scan signals at different excitation voltages at probe frequencies of 500 and 250 kHz were acquired for the PB and DB regions, respectively. The configurations of the inspection experiments and the A-scan signals under different conditions are shown in Figure 8.

Verification experiments of universality of the method and A-scan signals under different conditions. (a) Sample B: Frequency-500 kHz, Defect size-15 mm × 15 mm, (b) Sample B: Frequency-250 kHz, Defect size-15 mm × 15 mm, (c) Sample B: Frequency-500 kHz, Defect size-10 mm × 10 mm, (d) Sample B: Frequency-250 kHz, Defect size-10 mm × 10 mm, (e) Sample C: Frequency-500 kHz, Defect size-15 mm × 15 mm, (f) Sample C: Frequency-250 kHz, Defect size-15 mm × 15 mm, (g) Sample C: Frequency-500 kHz, Defect size-10 mm × 10 mm, and (h) Sample C: Frequency-250 kHz, Defect size-10 mm × 10 mm.

As can be seen from Figure 8, the trends of the A-scan signals are the same for different excitation voltages in each graph. As the excitation voltage increases, the resonance effect gradually increases (the amplitude of the wave increases). The simulation results of Section 3.1 show that 500 kHz is not in the optimal inspection frequency range compared to 250 kHz for Samples B and C. Several sets of experimental results reinforce this fact once again. For example, by comparing Figure 8(a) and (b) or (e) and (f), it is clear that the resonance effect is more pronounced when performing the inspection experiment with 250 kHz ultrasonic transducer. Comparing Figure 8(a) and (e) or (c) and (g), it can be seen that as the thickness of ST increases, its resonance effect is further suppressed. This result is consistent with the results presented in Figure 3(b) and (c). In addition, each of Figure 8 shows that the frequency of ultrasonic waves changes significantly when resonance occurs. In the configuration of Figure 8(b), the frequency of the resonant wave (compared to the wave of PB) becomes significantly higher and the wave vibration period becomes shorter. However, when the RT is 2 mm and other parameters and configurations are the same as in Figure 8(b), the frequency of the resonant wave decreases as shown in Figure 8(f). These experiments show that non-destructive testing of deep interfacial debonding defects based on resonance effects is indeed feasible. It is only necessary to select the corresponding inspection frequency according to the thickness parameters of each layer of the MABS workpiece.

4.3 Research on C-scan imaging method of ultrasonic resonant evaluation

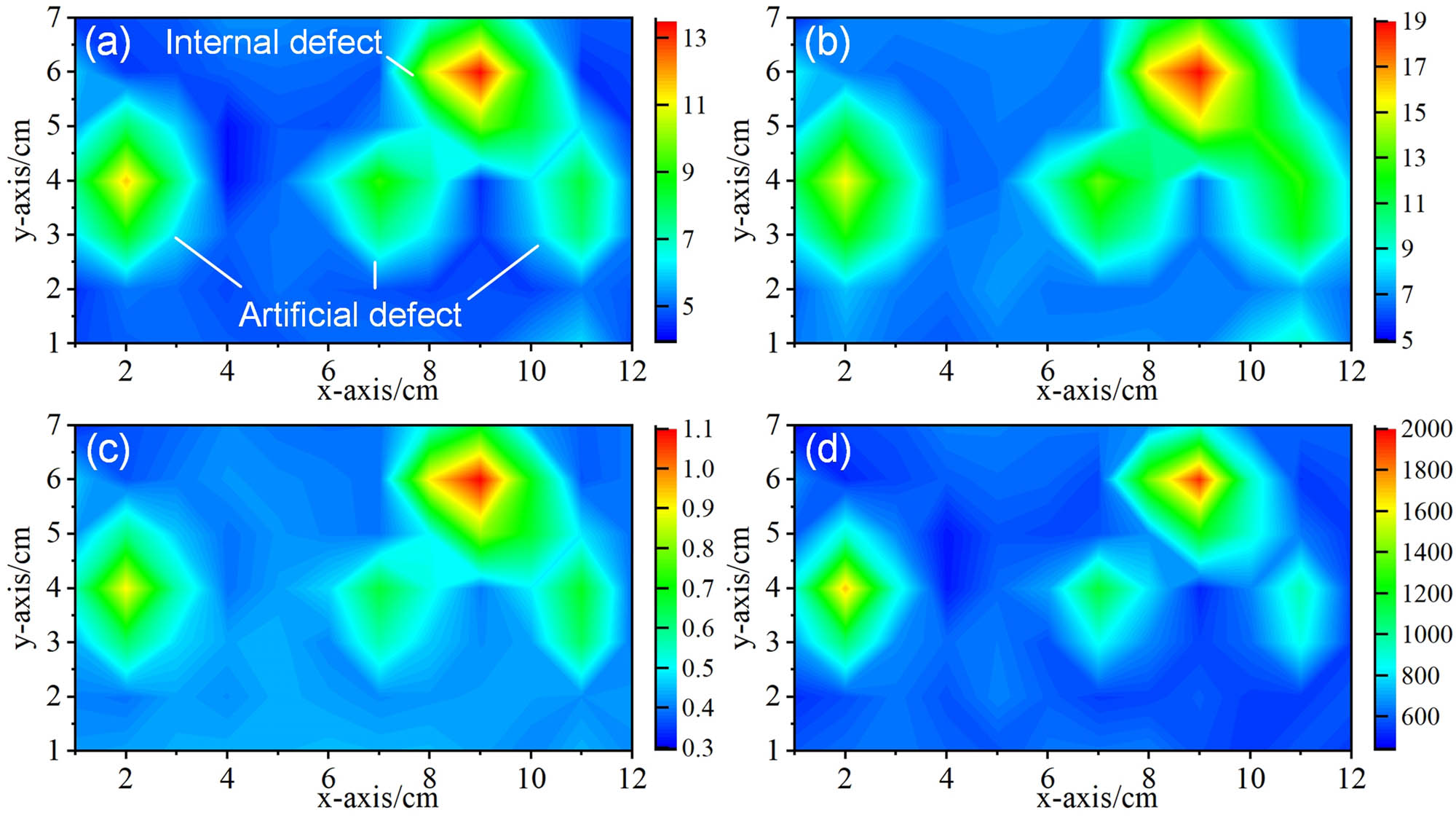

Compared with A-scan signal, the more readable and intuitive C-scan image is more expected by engineers. Therefore, a rectangular area (12 cm × 7 cm) containing the three artificial defects in Sample A was subjected to ultrasonic C-scan inspection with sampling interval and step increment of 1 cm. A total of 84 sets of A-scan data were acquired. Taking into account the characteristics of the A-scan signal, the integrations of the signal and the signal envelope, the maximum amplitude of the FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) of the signal, and the signal energy are used to draw the C-scan images to observe the contrast ratio between the PB area and the DB area. C-scan images for the four imaging modalities are shown in Figure 9.

C-scan images for the four imaging modalities. (a) C-scan image of signal integration, (b) C-scan image of signal envelope integration, (c) C-scan image of the maximum amplitude of the FFT of the signal, and (d) C-scan image of signal energy.

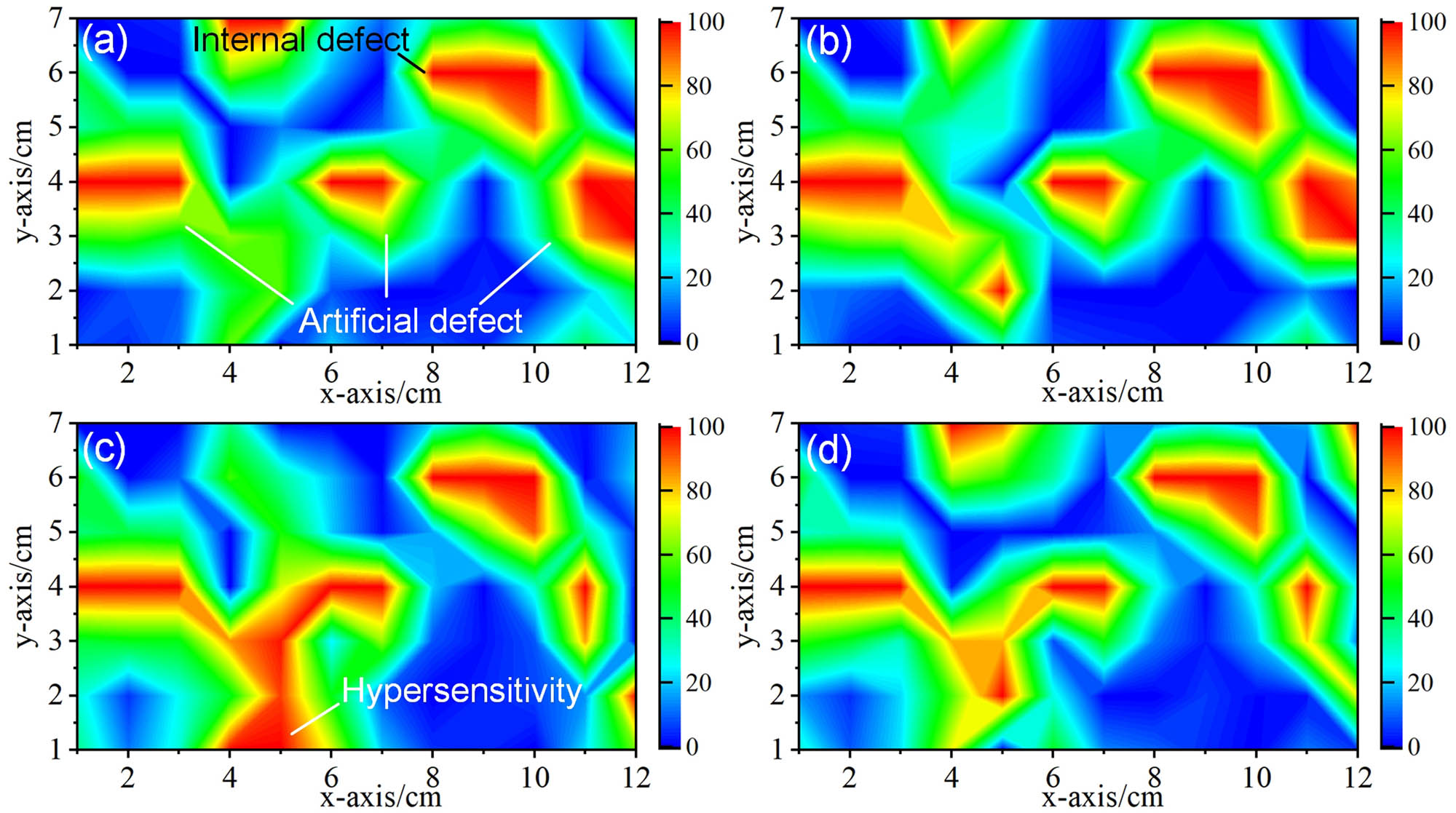

As can be seen from Figure 9, in terms of the legibility of the image alone, the four images are almost identical. All the three artificial defects (20, 15, and 10 mm) can be clearly visualized by the four imaging methods, and one internal natural defect in the sample is also detected. Relatively speaking, Figure 9(d) is more legible, and the outline of each defect can be easily distinguished, while the artificial defects and internal natural defect of the other three images are conjoined. In engineering, the signal energy imaging method can be preferred when using ultrasonic resonance method to inspect the deep interfacial debonding defects of MABS. In addition, in order to present a variety of C-scan images, the four sets of data obtained by the above imaging methods are normalized, and then the four sets of normalized data are used to draw the C-scan images. Taking column data normalization as an example, the C-scan images of the four imaging methods are shown in Figure 10.

Normalized C-scan images for the four imaging modalities. (a) C-scan image of normalized signal integration, (b) C-scan image of normalized signal envelope integration, (c) C-scan image of the normalized maximum amplitude of the FFT of the signal, and (d) C-scan image of normalized signal energy.

The four sets of images in Figures 9 and 10 have a one-to-one correspondence. By comparing the images, it can be found that the normalized C-scan images have higher sensitivity, which not only improves the contrast ratio of the defect area, but also highlights the weak change in signal outside the defect area. However, some areas of the normalized C-scan images are overly sensitive, such as the “Hypersensitive” area in Figure 10(c). In general, the imaging quality of Figure 10(a) is slightly better. Due to the high sensitivity of normalized imaging method, the combined application of normalized imaging method and non-normalized imaging method will greatly improve the accuracy of engineers’ judgment of inspection results.

5 Conclusion

In this study, a nondestructive evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of MABS is proposed based on the ultrasonic resonance theory and the aliasing effect of ultrasonic waves in MABS, which realizes the accurate non-destructive inspection of II-interfacial debonding defects of MABS. First, the relationship between the thickness of a specific layer of MABS and the frequency of ultrasonic wave when the resonance effect generated is determined based on the acoustic wave theory, which lays a theoretical foundation for the subsequent simulation and experimental research. Second, according to the actual condition, three MABS finite element models of different sizes were established by COMSOL, and these three models were used for frequency domain analysis and simulation to obtain the corresponding optimal inspection frequency. Next one of these models is used for the time domain analysis to obtain the time domain responses of the region of PB and the region with different defect sizes. Simulation and verification experiments show that the optimal inspection frequency for II-interfacial debonding defects is 500 kHz when the shell thickness is 1.5 mm and the EPDM thickness is 1.5 mm, and the optimal inspection frequency is 250 kHz when the shell thickness is 1.5 mm or 2.0 mm and the EPDM thickness is 2.0 mm. The presence of defect causes a resonance effect, and in the same inspection configuration, the larger the defect size, the more pronounced this effect is. This resonance effect is manifested in the time domain as an increase in the amplitude of the A-scan signal and an increase in the vibration time. The resonance effect also causes a pronounced change in the frequency of the received ultrasonic wave. The inspection experiments on the artificial defect samples show that it is indeed feasible to realize the non-destructive testing of the deep interface debonding defects of multilayer material bonded structural parts with different parameters based on resonance effect and the increase in the excitation voltage further highlights the ultrasonic resonance effect. The studies of C-scan imaging method of ultrasonic resonance inspection showed that all the four C-scan imaging methods – the integrations of the signal and the signal envelope curve, the maximum amplitude of the FFT of the signal, and the signal energy – can clearly show the sizes and locations of artificial defects and internal natural defect. Normalized C-scan imaging method can further highlight the weak changes in signal (defect areas). In practice, it is recommended to use both C-scan imaging and normalized C-scan imaging to improve the accuracy of the analysis of the results. Furthermore, binarization of the above C-scan images will facilitate the quantitative evaluation of C-scan results.

Finally, the acoustic response of multilayered structures is much more complex than mono-material flat plates and its natural frequencies depend on the material properties (density, elastic properties), the geometry of the specimen, the thickness of the adhesive and adherend layers, and the boundary conditions. In future work, more in-depth research can be carried out on these factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of all the sponsors. The authors also express sincere gratitude to the editor and reviewers for their valuable comments, which have greatly improved this article.

-

Funding information: This work is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (Grant No. 23KJB460007), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52275191 and 51335001), Key R & D plan of Jiangsu Province (Grant No.BE2021071), Independent innovation fund of Jiangsu Agricultural Committee (Grant No. CX(20)2024), QingLan Project and 333 Project of Jiangsu Province (2021), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20200900).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Carlos, F., P. Bizarria, and L. Felipe. Detection of liner surface defects in solid rocket motors using multilayer perceptron neural networks. Polymer Testing, Vol. 88, 2020, id. 106559.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106559Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zhang, M., R. Chen, L. Zheng, J. Yao, F. Liu, and Y. Chen. Electromagnetic ultrasonic signal processing and imaging for debonding detection of bonded structures. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, Vol. 205, No. October, 2022, id. 112106.10.1016/j.measurement.2022.112106Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yilmaz, B., D. Smagulova, and E. Jasiuniene. Model-assisted reliability assessment for adhesive bonding quality evaluation with ultrasonic NDT. NDT & E International, Vol. 126, 2022, id. 102596.10.1016/j.ndteint.2021.102596Search in Google Scholar

[4] Spytek, J., L. Ambrozinski, and L. Pieczonka. Evaluation of disbonds in adhesively bonded multilayer plates through local wavenumber estimation. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 520, 2022, id. 116624.10.1016/j.jsv.2021.116624Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wang, X., J. Wang, G. Shen, X. Li, and Z. Huang. Research on interface bonding characteristics of layered medium using ultrasonic oblique incidence. Composite Structures, Vol. 295, 2022, id. 115733.10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115733Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ponram, R. A., B. H. Prasad, and S. S. Kumar. Thickness mapping of rocket motor casing using ultrasonic thickness gauge. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2018, pp. 11371–11375.10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.104Search in Google Scholar

[7] Yang, S., L. Gu, and R. F. Gibson. Nondestructive detection of weak joints in adhesively bonded composite structures. Composite Structures, Vol. 51, No. 1, 2001, pp. 63–71.10.1016/S0263-8223(00)00125-2Search in Google Scholar

[8] Maeva, E., I. Severina, S. Bondarenko, G. Chapman, B. O’Neill, F. Severin, et al. Acoustical methods for the investigation of adhesively bonded structures: A review. Canadian Journal of Physics, Vol. 82, No. 12, 2004, pp. 981–1025.10.1139/p04-056Search in Google Scholar

[9] Haldren, H., W. T. Yost, D. Perey, K. Elliott Cramer, and M. C. Gupta. A constant-frequency ultrasonic phase method for monitoring imperfect adherent/adhesive interfaces. Ultrasonics, Vol. 120, No. February 2020, 2022, id. 106641.10.1016/j.ultras.2021.106641Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Smagulova, D. and E. Jasiuniene. High quality process of ultrasonic nondestructive testing of adhesively bonded dissimilar materials. In IEEE 7th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace. Pisa, Italy, 2020, pp. 475–479.10.1109/MetroAeroSpace48742.2020.9160095Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hou, H., J. Li, S. Xia, Y. Meng, and J. Shen. Ultrasonic resonance-based inspection of ultra-thin nickel sheets bonded to silicone. Materials Research Express, Vol. 10, 2023, pp. 1–6.10.1088/2053-1591/acc00eSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Sahoo, S. K., R. Narasimha Rao, K. Srinivas, M. K. Buragohain, and C. Sri Chaitanya. A novel NDE approach towards evaluating adhesive bonded interfaces. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 26, 2020, pp. 1191–1197.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.240Search in Google Scholar

[13] Jasiuniene, E., L. Mazeika, V. Samaitis, V. Cicenas, and D. Mattsson. Ultrasonic non-destructive testing of complex titanium/carbon fibre composite joints. Ultrasonics, Vol. 95, 2019, pp. 13–21.10.1016/j.ultras.2019.02.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Mondet, B., J. Brunskog, C. Jeong, and J. Holger. From absorption to impedance: Enhancing boundary conditions in room acoustic simulations. Applied Acoustics, Vol. 157, 2020, id. 106884.10.1016/j.apacoust.2019.04.034Search in Google Scholar

[15] Yang, H., Y. Xiao, H. Zhao, J. Zhong, and J. Wen. On wave propagation and attenuation properties of underwater acoustic screens consisting of periodically perforated rubber layers with metal plates. Journal of Sound and Vibration, Vol. 444, 2019, pp. 21–34.10.1016/j.jsv.2018.12.031Search in Google Scholar

[16] Dai, T., Y. Hu, L. Ning, F. Cheng, and J. Pang. Effects due to aliasing on surface-wave extraction and suppression in frequency-velocity domain. Journal of Applied Geophysics, Vol. 158, 2018, pp. 71–81.10.1016/j.jappgeo.2018.07.011Search in Google Scholar

[17] Xufei, G., Y. Yanwei, and H. Xingcheng. Classification and inspection of debonding defects in solid rocket motor shells using machine learning algorithms. Journal of Nanoelectronics and Optoelectronics, Vol. 16, No. 7, 2021, pp. 1082–1089.10.1166/jno.2021.3055Search in Google Scholar

[18] Loukkal, A., M. Lematre, M. Bavencoffe, and M. Lethiecq. Modeling and numerical study of the influence of imperfect interface properties on the reflection coefficient for isotropic multilayered structures. Ultrasonics, Vol. 103, 2020, id. 106099.10.1016/j.ultras.2020.106099Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Zheng, S., S. Zhang, Y. Luo, B. Xu, and W. Hao. Nondestructive analysis of debonding in composite/rubber/rubber structure using ultrasonic pulse-echo method. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation, Vol. 36, No. 5, 2021, pp. 515–527.10.1080/10589759.2020.1825707Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhenggan, Z., W. Jun, L. Yang, W. Fei, and W. Quan. Ultrasonic array testing and evaluation method of multilayer bonded structures. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Vol. 49, No. 12, 2023, pp. 3207–3214.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Effect of superplasticizer in geopolymer and alkali-activated cement mortar/concrete: A review

- Experimenting the influence of corncob ash on the mechanical strength of slag-based geopolymer concrete

- Powder metallurgy processing of high entropy alloys: Bibliometric analysis and systematic review

- Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review

- A review on partial substitution of nanosilica in concrete

- Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics

- Modification of PEEK for implants: Strategies to improve mechanical, antibacterial, and osteogenic properties

- Interfacing the IoT in composite manufacturing: An overview

- Advances in processing and ablation properties of carbon fiber reinforced ultra-high temperature ceramic composites

- Advancing auxetic materials: Emerging development and innovative applications

- Revolutionizing energy harvesting: A comprehensive review of thermoelectric devices

- Exploring polyetheretherketone in dental implants and abutments: A focus on biomechanics and finite element methods

- Smart technologies and textiles and their potential use and application in the care and support of elderly individuals: A systematic review

- Reinforcement mechanisms and current research status of silicon carbide whisker-reinforced composites: A comprehensive review

- Innovative eco-friendly bio-composites: A comprehensive review of the fabrication, characterization, and applications

- Review on geopolymer concrete incorporating Alccofine-1203

- Advancements in surface treatments for aluminum alloys in sports equipment

- Ionic liquid-modified carbon-based fillers and their polymer composites – A Raman spectroscopy analysis

- Emerging boron nitride nanosheets: A review on synthesis, corrosion resistance coatings, and their impacts on the environment and health

- Mechanism, models, and influence of heterogeneous factors of the microarc oxidation process: A comprehensive review

- Synthesizing sustainable construction paradigms: A comprehensive review and bibliometric analysis of granite waste powder utilization and moisture correction in concrete

- 10.1515/rams-2025-0086

- Research Articles

- Coverage and reliability improvement of copper metallization layer in through hole at BGA area during load board manufacture

- Study on dynamic response of cushion layer-reinforced concrete slab under rockfall impact based on smoothed particle hydrodynamics and finite-element method coupling

- Study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled brick aggregate concrete with waste fiber

- Multiscale characterization of the UV aging resistance and mechanism of light stabilizer-modified asphalt

- Characterization of sandwich materials – Nomex-Aramid carbon fiber performances under mechanical loadings: Nonlinear FE and convergence studies

- Effect of grain boundary segregation and oxygen vacancy annihilation on aging resistance of cobalt oxide-doped 3Y-TZP ceramics for biomedical applications

- Mechanical damage mechanism investigation on CFRP strengthened recycled red brick concrete

- Finite element analysis of deterioration of axial compression behavior of corroded steel-reinforced concrete middle-length columns

- Grinding force model for ultrasonic assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallic compounds and experimental validation

- Enhancement of hardness and wear strength of pure Cu and Cu–TiO2 composites via a friction stir process while maintaining electrical resistivity

- Effect of sand–precursor ratio on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer mortar with manufactured sand

- Research on the strength prediction for pervious concrete based on design porosity and water-to-cement ratio

- Development of a new damping ratio prediction model for recycled aggregate concrete: Incorporating modified admixtures and carbonation effects

- Exploring the viability of AI-aided genetic algorithms in estimating the crack repair rate of self-healing concrete

- Modification of methacrylate bone cement with eugenol – A new material with antibacterial properties

- Numerical investigations on constitutive model parameters of HRB400 and HTRB600 steel bars based on tensile and fatigue tests

- Research progress on Fe3+-activated near-infrared phosphor

- Discrete element simulation study on effects of grain preferred orientation on micro-cracking and macro-mechanical behavior of crystalline rocks

- Ultrasonic resonance evaluation method for deep interfacial debonding defects of multilayer adhesive bonded materials

- Effect of impurity components in titanium gypsum on the setting time and mechanical properties of gypsum-slag cementitious materials

- Bending energy absorption performance of composite fender piles with different winding angles

- Theoretical study of the effect of orientations and fibre volume on the thermal insulation capability of reinforced polymer composites

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel ternary magnetic composite for the enhanced adsorption capacity to remove organic dyes

- Couple effects of multi-impact damage and CAI capability on NCF composites

- Mechanical testing and engineering applicability analysis of SAP concrete used in buffer layer design for tunnels in active fault zones

- Investigating the rheological characteristics of alkali-activated concrete using contemporary artificial intelligence approaches

- Integrating micro- and nanowaste glass with waste foundry sand in ultra-high-performance concrete to enhance material performance and sustainability

- Effect of water immersion on shear strength of epoxy adhesive filled with graphene nanoplatelets

- Impact of carbon content on the phase structure and mechanical properties of TiBCN coatings via direct current magnetron sputtering

- Investigating the anti-aging properties of asphalt modified with polyphosphoric acid and tire pyrolysis oil

- Biomedical and therapeutic potential of marine-derived Pseudomonas sp. strain AHG22 exopolysaccharide: A novel bioactive microbial metabolite

- Effect of basalt fiber length on the behavior of natural hydraulic lime-based mortars

- Optimizing the performance of TPCB/SCA composite-modified asphalt using improved response surface methodology

- Compressive strength of waste-derived cementitious composites using machine learning

- Melting phenomenon of thermally stratified MHD Powell–Eyring nanofluid with variable porosity past a stretching Riga plate

- Development and characterization of a coaxial strain-sensing cable integrated steel strand for wide-range stress monitoring

- Compressive and tensile strength estimation of sustainable geopolymer concrete using contemporary boosting ensemble techniques

- Customized 3D printed porous titanium scaffolds with nanotubes loading antibacterial drugs for bone tissue engineering

- Facile design of PTFE-kaolin-based ternary nanocomposite as a hydrophobic and high corrosion-barrier coating

- Effects of C and heat treatment on microstructure, mechanical, and tribo-corrosion properties of VAlTiMoSi high-entropy alloy coating

- Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology

- Promoting low carbon construction using alkali-activated materials: A modeling study for strength prediction and feature interaction

- Entropy generation analysis of MHD convection flow of hybrid nanofluid in a wavy enclosure with heat generation and thermal radiation

- Friction stir welding of dissimilar Al–Mg alloys for aerospace applications: Prospects and future potential

- Fe nanoparticle-functionalized ordered mesoporous carbon with tailored mesostructures and their applications in magnetic removal of Ag(i)

- Study on physical and mechanical properties of complex-phase conductive fiber cementitious materials

- Evaluating the strength loss and the effectiveness of glass and eggshell powder for cement mortar under acidic conditions

- Effect of fly ash on properties and hydration of calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based materials with high water content

- Analyzing the efficacy of waste marble and glass powder for the compressive strength of self-compacting concrete using machine learning strategies

- Experimental study on municipal solid waste incineration ash micro-powder as concrete admixture

- Parameter optimization for ultrasonic-assisted grinding of γ-TiAl intermetallics: A gray relational analysis approach with surface integrity evaluation

- Producing sustainable binding materials using marble waste blended with fly ash and rice husk ash for building materials

- Effect of steam curing system on compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete

- A sawtooth constitutive model describing strain hardening and multiple cracking of ECC under uniaxial tension

- Predicting mechanical properties of sustainable green concrete using novel machine learning: Stacking and gene expression programming

- Toward sustainability: Integrating experimental study and data-driven modeling for eco-friendly paver blocks containing plastic waste

- A numerical analysis of the rotational flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a unidirectional extending surface with velocity and thermal slip conditions

- A magnetohydrodynamic flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid past a convectively heated rotating disk surface: A passive control of nanoparticles

- Prediction of flexural strength of concrete with eggshell and glass powders: Advanced cutting-edge approach for sustainable materials

- Efficacy of sustainable cementitious materials on concrete porosity for enhancing the durability of building materials

- Phase and microstructural characterization of swat soapstone (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2)

- Effect of waste crab shell powder on matrix asphalt

- Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer

- Influence of pH on the synthesis of carbon spheres and the application of carbon sphere-based solid catalysts in esterification

- Experimenting the compressive performance of low-carbon alkali-activated materials using advanced modeling techniques

- Thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) characterization of cold-pressed oil blends and Saccharomyces cerevisiae-based microcapsules obtained with them

- Investigation of temperature effect on thermo-mechanical property of carbon fiber/PEEK composites

- Computational approaches for structural analysis of wood specimens

- Integrated structure–function design of 3D-printed porous polydimethylsiloxane for superhydrophobic engineering

- Exploring the impact of seashell powder and nano-silica on ultra-high-performance self-curing concrete: Insights into mechanical strength, durability, and high-temperature resilience

- Axial compression damage constitutive model and damage characteristics of fly ash/silica fume modified magnesium phosphate cement after being treated at different temperatures

- Integrating testing and modeling methods to examine the feasibility of blended waste materials for the compressive strength of rubberized mortar

- Special Issue on 3D and 4D Printing of Advanced Functional Materials - Part II

- Energy absorption of gradient triply periodic minimal surface structure manufactured by stereolithography

- Marine polymers in tissue bioprinting: Current achievements and challenges

- Quick insight into the dynamic dimensions of 4D printing in polymeric composite mechanics

- Recent advances in 4D printing of hydrogels

- Mechanically sustainable and primary recycled thermo-responsive ABS–PLA polymer composites for 4D printing applications: Fabrication and studies

- Special Issue on Materials and Technologies for Low-carbon Biomass Processing and Upgrading

- Low-carbon embodied alkali-activated materials for sustainable construction: A comparative study of single and ensemble learners

- Study on bending performance of prefabricated glulam-cross laminated timber composite floor

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part I

- Supplementary cementitious materials-based concrete porosity estimation using modeling approaches: A comparative study of GEP and MEP

- Modeling the strength parameters of agro waste-derived geopolymer concrete using advanced machine intelligence techniques

- Promoting the sustainable construction: A scientometric review on the utilization of waste glass in concrete

- Incorporating geranium plant waste into ultra-high performance concrete prepared with crumb rubber as fine aggregate in the presence of polypropylene fibers

- Investigation of nano-basic oxygen furnace slag and nano-banded iron formation on properties of high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Effect of incorporating ultrafine palm oil fuel ash on the resistance to corrosion of steel bars embedded in high-strength green concrete

- Influence of nanomaterials on properties and durability of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete

- Influence of palm oil ash and palm oil clinker on the properties of lightweight concrete