Abstract

Shape memory polymers (SMPs) can be programmed to a temporary shape, and then recover its original shape by applying environmental stimuli when needed. To expands the application space of SMPs, the shape memory polymer composites (SMPCs) were fabricated either to improve the mechanical properties, or to incorporate more stimulus methods. With the deepening of research, the filler arrangement can also be used to reshape the composites from a two dimensional sheet to a three dimensional structure by a strain mismatch. Recently, SMPCs show more and more interesting behaviors. To gain systematic understanding, we briefly review the recent progress and summarize the challenges in SMPCs. We focus on the reinforcement methods and the composite properties. To look to the future, we review the bonding points with the advanced manufacturing technology and their potential applications.

1 Introduction

Shape change under environment stimuli is an essential survival skill for animals and plants. Recently, people found that many types of artificial materials can achieve shape change under environment stimuli, including alloys [1], amorphous polymers [2], liquid crystal elastomers [3, 4], semi-crystalline polymers [5], and ceramics [6], although each material has its unique mechanisms and properties. These materials were termed shape memory materials. Amorphous shape memory polymers (SMPs), as one of the classic shape memory materials with many favorable properties, such as high programmable strain, light weight, low cost, and biocompatibility, were widely used to fabricate actuators [7], micro-devices [8], biomedical equipment [9], deployable structures [10], and origami structures [11].

The shape memory mechanism of amorphous SMPs can be attributed to the stress relaxation behaviors [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Deformation of polymer relaxes instantaneously when relaxation time is small, but sluggishly when relaxation time is large. The variation of relaxation time plays a key role for amorphous SMPs to store and release the strain. Several exciting methods were developed to achieve shape memory behaviors of amorphous polymers by tunable relaxation times, such as glass transition [12, 18], photodimerization [2], oxidation/redox reaction [19], plasticizing effects [20], and bond exchange reaction [11].

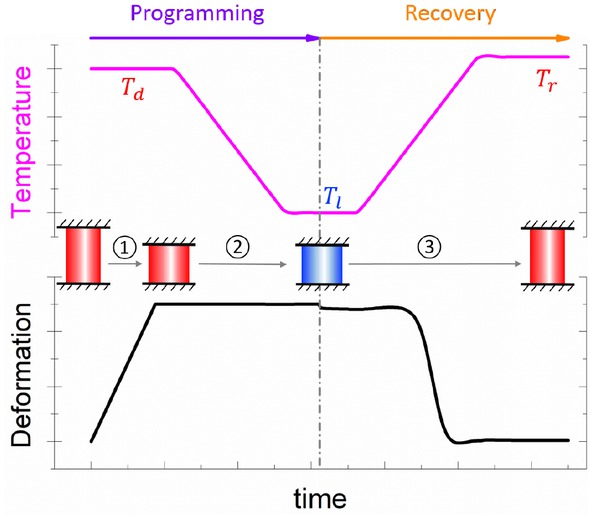

One typical shape memory cycle of thermally responsive amorphous SMPs by glass transition contains two steps, shape programming and recovery, as shown in Figure 1. In the first step, the sample is first heated to the deforming temperature (Td) above the glass transition temperature (Tg) to gradually reduce the relaxation time. At Td the sample was deformed to a desired shape (operation ➀ ), then cooled down to the low temperature (Tl) below Tg to fix the deformation by increasing the relaxation time (operation ② ), and at last mechanically unloaded. The programmed (temporary) shape (after a small spring-back upon unloading), which can be fixed as long as the material is kept to the temperature below Tg. When needed, in the second step the sample can be re-heated to the recovery temperature (Tr) above Tg to reduce the relaxation time, and recover its permanent shape (operation ➂ ). It has been well documented that the programming/recovery temperature [21], aging time [22], diffusion process [23, 24, 25], and temperature changing rate [26], would influence the shape recovering process.

One typical shape memory cycle of thermally actuated amorphous SMPs

However, towards engineering applications, amorphous SMPs suffer from some limitations. The main issue is that SMPs as a kind of polymers, their stiffness, strength, heat conductivity and most importantly, recovery stress are too low. Poor mechanical properties of SMPs prevent being used as structural materials, and low heat conductivity may delay the response of thermally active SMPs. Cause the shape recovery mechanism of amorphous polymers is based on relaxation behaviors, their intrinsic recovery are much slower than shape memory alloys induced by the martensitic transformation [27].

To overcome the shortcomings of pure SMPs and to expand the scope of applications, researchers found that fabricating composite materials is a good method. The composite materials are made up of two or more materials, which keep as individual components. And composites are preferred to have all excellent physical properties of their components. For the traditional shape memory polymer composites (SMPCs), the matrix of SMPs keeps the shape memory effect, and the reinforcement fillers gradually increase the mechanical properties [28]. More interestingly, fillers can also enable SMPCs multi-functionalities in the shape recovery process. The fillers can be designed as an energy converter to trigger thermally responsive SMP matrix, such as Joule heat generators [29], radiofrequency absorbers [30], or infrared radiation absorbers [31]. The self-healing fillers can also be used to heal cracks in SMP matrix [32]. In addition to SMPCs with SMP matrix, the elastomer based composites filled by SMP fibers also show unique properties. For example, SMP fibers in elastomer matrix can be used to induce the strain mismatch, and therefore fold the plate sheet to a 3D structure [33]. Both excellent mechanical properties and multi-functionalities can be achieved in SMPCs.

Many excellent reviews of SMP research have been published, respectively, focusing on materials and mechanism [34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45], composites [46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53], stimulus methods [54, 55, 56, 57], simulations [44, 58], and applications [59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66]. With the development of materials, manufacture technologies, and designed methods, SMPs and SMPCs show more and more interesting properties and behaviors. Here, we review the recent progress in amorphous polymer based SM-PCs, and focus on the methods, mechanical properties and applications. To make our discussion clear, we divide SM-PCs into two classes based on whether the fillers follow the ordered distribution, i.e., hybrid composites and patterned composites. The review is arranged as following: section 2 reviews the progress of hybrid composites. Section 3 discusses the patterned composites. Section 4 summarizes the recently developed applications, and look to the prospects for the future research.

2 The hybrid composites

The hybrid composites, also termed nanocomposites, are reinforced by randomly distributed nano-sized fillers. Two groups of fillers are used as nano-sized fillers in SMPCs. The first group contains silica, carbons, nitrides, metals, and metallic oxides. The modulus of these fillers is much higher than polymer matrix. They would gradually enhance the mechanical properties of SMP matrix, and sometimes can be designed as an energy converter to provide novel stimulus methods. The second group is polymer fillers, such as celluloses, crystalline polymers, and elastomers. The polymer fillers would enable the composites multi-functionalities.

2.1 SiC and SiO2

SiC and SiO2 widely exist in nature, and are the most traditional fillers in composites [67]. SiC and SiO2 show two geometries, respectively, sphere and rod. SiC and SiO2 fillers can gradually increase the mechanical properties of SM-PCs, and reduce the response times.

Gall et al. [68] used SiC clays with a spherical shape (~300 nm) to enhance thermoset epoxy SMPs. They observed that the micro-hardness, elastic modulus and the free recovery speed of the nanocomposites increase with clay contents. Recovery force of 20 wt.% composites under constrained conditions is much higher than pure matrix. However, with the clay content increase, 40 wt.% composites show irrecoverable deformation. Similar results have been observed by Ohki et al. [28] in the glass fiber reinforced polyurethane (PU) based SMPCs, that the shape recovery ratio decreases with fiber content increase. Xu et al. [69] studied the enhancing effect of rod-shaped SiC clays on shape memory polystyrene (PS) matrix. They found 1 wt.% clays would gradually increase the modulus up to 3 times, and attributed the better enhancements of rod-shape fillers with higher aspect ratio to the effective stress transferring. Dong et al. [70] used the silane coupling agent 3-triethoxysilylpropylamine to improve the interfacial strength between the SiO2 particles and epoxy SMPs. The SiO2 particles are uniformly dispersed in the epoxy in Figure 2a, and particles and epoxy form inorganic and organic networks Figure 2c. Due to the excellent interface between fillers and matrix, the composites exhibited high shape recovery ratio and shape fixity ratio approximately 100% even after 10 thermo-mechanical cycles in Figure 2d.

![Figure 2 (a) TEM images of the water-borne epoxy particles. (b) tanδ of the SiO2/epoxy composites from dynamic mechanical analysis. (c) Schematic illustration of silica–epoxy composites synthesis. (d) Stress–strain curves of the 2.5 wt.% SiO2/epoxy composite during 10 thermo-mechanical cycles [70]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_002.jpg)

(a) TEM images of the water-borne epoxy particles. (b) tanδ of the SiO2/epoxy composites from dynamic mechanical analysis. (c) Schematic illustration of silica–epoxy composites synthesis. (d) Stress–strain curves of the 2.5 wt.% SiO2/epoxy composite during 10 thermo-mechanical cycles [70]

2.2 Carbons

Carbon fillers, including carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon nanofibers (CNFs), and recently graphene, were widely used in fabricating composites. In addition to enhance the mechanical properties, carbon fillers can be designed as an energy converter by generating Joule heat or absorbing the electromagnetic radiation. Therefore, shape recovery of SMPCs can be triggered by applying voltage or a remote field.

CB, as one of the most traditional carbon materials, is widely used to reinforce SMPCs. Le et al. [71] fabricated thylene-1-octene based composites filled by 17 wt.% CB to achieve Joule-heating active shape memory behaviors. They found that CB aggregations would reduce the resistance of SMPCs. The reason is that the geometry of CB fillers is sphere, and uniform distribution of CB fillers makes it hard to get in touch with each other, further leading to the increase of resistance. Consequently, the aggregations form bunches of microcircuits, and SMPCs with CB aggregations can get a fast recovery when applying a voltage. However, nonuniform aggregations of fillers in composites reduce the mechanical properties. Yu et al. [72] reported the strain induced softening effect in CB filled composites, which is also termed Mullins effects [73]. The loading history gradually reduced the modulus of composites as shown in Figure 3a, which indicates the softening effect is induced by the micro-damages. They also found that the larger the programmed deformation, the slower the shape recovery as shown in Figure 3b. Thus, the softening effect induced by the damage inside SMPCs increases the shape recovery time.

![Figure 3 (a) Stress-strain curves under cyclic loading on 9 wt.% CB filled SMPCs at 50∘C to different maximum strains, i.e., 10% first, then 15% and finally 20% with a strain rate of 0.15/min. The dash line denotes reference stress-strain curve without previous strain history. (b) Shape recovery ratio plotted as a function of heating time during the free recovery of 9 wt.% CB filled SMPCs [72]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_003.jpg)

(a) Stress-strain curves under cyclic loading on 9 wt.% CB filled SMPCs at 50∘C to different maximum strains, i.e., 10% first, then 15% and finally 20% with a strain rate of 0.15/min. The dash line denotes reference stress-strain curve without previous strain history. (b) Shape recovery ratio plotted as a function of heating time during the free recovery of 9 wt.% CB filled SMPCs [72]

CNTs have tube-like geometries with a large aspect ratio, and are much easier to interact with each other in SMPCs. Therefore, CNTs usually show better enhancement than CB fillers on both electrical and mechanical properties in composites [74, 75]. Liu et al. [76] synthesized diglycidyl ether of bisphenol A, methylhexahydrophthalic anhydride (DGEBA-MHHPA) shape memory epoxy with a wide range of Tg (65∘C ~ 140∘C), and fabricated composites filled by CNTs. They showed that a small amount of CNTs (0.75 wt.%) can significantly increase the mechanical properties (including modulus, strength, and strain at break), recovery rate, and cyclic stability of SMPCs. Cho et al. [77] used CNTs to reinforce PU matrix, and proved that 5 wt.% composites with a conductivity of ~10−3S · cm−1 can achieve electrically driving shape recovery. Also, modulus of SMPCs is gradually increased. To increase the interface strength, Xiao et al. [78] grafted the CNTs with poly ethylene glycol (PEG), and fabricated poly ϵ-caprolactone (PCL)/CNT SMPCs. Due to the strong interface, the break strain is gradually increased. Fei et al. [79] fabricated CNT reinforced PMMA-BA composites. A post thermal treatment was used to eliminate mismatching between fillers and matrix, further to gradually reduce the electrical resistance. By applying electrical voltage and switching the power on/off, the recovery process can be controlled, and multiple shapes between original and programming shape can be obtained [79]. Du et al. [80] fabricated CNT/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) SMPCs. With increase of CNT content, both electrical conductivity and thermal conductivity increase.Good electrical and thermal conductivity would accelerate the shape memory behaviors.

CNFs are very similar with CNTs, but have a solid structure instead of the hollow structure. Luo and Mather [81] incorporated continuous, non-woven CNFs into the epoxy based SMP. The CNFs form a network, which improves the electrical conductivity, heat transfer and recovery stress. Recently, Guo et al. [82] systematically studied the influence of CNF content on the mechanical properties of SMPCs. With CNT content increase, the modulus and break strain first increase, and then decrease. They reported that SMPCs with the moderate content of CNFs (~7 wt.%) shows the best properties.

Recently, graphene as a carbon material with the repeating two-dimensional hexagonal lattice, is very promising in the electronics industry, due to its excellent electrical and optical properties. The graphene can also gradually improve the mechanical properties of SMPCs. Yoonessi et al. [83] fabricated graphene polyimide nanocomposites. They grafted imide moieties to amine-functionalized graphene, which enhanced the interface between graphene and polyimide. Modulus of the imidized graphene nanocomposites is ~25% higher than those of unmodified graphene nanocomposites. The recovery rate and thermal stability of composites are also improved by graphene. Qi et al. [20] fabricated PVA nanocomposites reinforced by graphene oxide (GO), which was obtained by treating graphene with strong oxidizers. The hydrogen bonds between GO and PVA increase the shape memory behaviors and mechanical properties in Figure 4a. Due to the plasticizing effect of water on PVA, the relaxation time of composites can be gradually reduced when immersed in water in Figure 4b, and therefore achieve shape memory effects triggered by water. The break strain increases significantly with GO content to 42% from ~12% by filling 0.5 wt.% GO. Kang et al. [84] also found the GO fillers can increase the impact strength and fracture toughness of hybrid composites.

![Figure 4 (a) Stress–strain curves in uniaxial tensile tests of GO/PVA composites with different GO contents. (b) The shape memory behavior of the 0.5 wt% GO/PVA composites immersed in water [20]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_004.jpg)

(a) Stress–strain curves in uniaxial tensile tests of GO/PVA composites with different GO contents. (b) The shape memory behavior of the 0.5 wt% GO/PVA composites immersed in water [20]

2.3 Metals and metal oxides

Metals and metal oxides usually have good electrical and magnetic properties. Due to the good ductility, metals are chosen to fabricate the flexible electronic devices [85]. Some metals, such as Au and Ag, also have very good biocompatibility, and can get very good biodegradability by forming nanoparticles. Metals and metal oxides provide another choice to fabricate SMPCs with multi-stimulus methods.

Hribar et al. [31] used gold nanorods to fill A6/tBA networks. The nanorod size is less than the wavelength of infrared radiation (IR), thus the composites can absorb IR light to generate heating and consequently trigger the matrix’s shape memory effects. The photothermal conversion rate increases with nanorod contents. Similarly, Zhang and Zhao used the gold nanoparticles to achieve local photonic heating [86]. Yu et al. [87] used silver nanowires (AgNWs) to coat on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate. AgNWs are embedded in photocurable acrylate-based polymer films, and then attached to PET films. Due to the large aspect ratio of AgNWs, AgNWs form a conductive network in Figure 5a and Figure 5b, and can generate Joule heat when applying voltage. After combining light-emitting diodes (LEDs), a shape memory LEDs can be fabricated in Figure 5c and Figure 5d. They showed that the deformable flexible electronics can be achieved by SMPCs.

![Figure 5 (a) SEM image of the original AgNW coating. (b) TEM image of the AgNWs. The photographs of shape memory LEDs emitting, (c) in plat states at 120 ∘C and (d) in bending states [87]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_005.jpg)

(a) SEM image of the original AgNW coating. (b) TEM image of the AgNWs. The photographs of shape memory LEDs emitting, (c) in plat states at 120 ∘C and (d) in bending states [87]

Some metal oxides are sensitive to electromagnetic, and proved a remote stimulus method. Schmidt [88] and Mohr et al. [89], separately, fabricated Fe3O4 filled SMPCs, by which electromagnetic energy can be converted to thermal energy to trigger shape memory effects. Similar magnetic stimulus method was also achieved in the shape memory foam by Vialle et al. [90]. Yakacki et al. [91] studied the influence of filler content on the properties of SMPCs. Higher content of Fe3O4 fillers increase the magneticthermal conversion to produce a higher temperature. However, Fe3O4 reduces the break elongation and increase the irrecoverable strain in free recovery cycles. Zhang et al. [92] fabricated electrospun Nafion/Fe3O4 nanofibers, and achieved fast shape recovery (less than 18 s) by applying a magnetic field.

The metal oxides also can be used to trigger multishape recovery process. The shape memory polymers are capable to memorize more than one temporary shape, termed as multi-shape memory effects, and different shapes can be recovered when the temperature is subsequently increased [93, 94]. This multiple memory effect of amorphous polymers was attributed to the different relaxation modes of polymer chains by Yu et al. [13]. The different relaxation modes are corresponding to different relaxation times. When increasing (or decreasing) temperature, different relaxation modes are active (or inactive) sequentially, leading to the observed multi-shape memory effects. Kumar et al. [95] fabricated Fe3O4 filled composites. By controlling the magnetic strength, different temperature insides the composites can be generated by the magnetic-thermal conversion, and further leading to multiple shapes in Figure 6. It should be pointed out that to precisely control the intermedia recovery shape, the effect of temperature change rate on the recovery process should be considered [26].

![Figure 6 Infrared and optical images during the free recovery process. By controlling the magnetic strengths to achieve different temperature, triple-shape can be obtained [95]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_006.jpg)

Infrared and optical images during the free recovery process. By controlling the magnetic strengths to achieve different temperature, triple-shape can be obtained [95]

2.4 Cellulose

Cellulose is an important polymer, widely exists in the cell wall of green plants, and is used to make paper and composites [96, 97]. Cellulose has good biodegradability. Due to the hydrogen bonds which can be easily generated and erased by the hydroxy group in cellulose, the raw materials of celluloses can be reshaped by immersing in water [98]. Recently, celluloses are chosen to reinforce SMPs, to improve the mechanical properties and the shape response to water.

Auad et al. [99] fabricated nanocellulose/PU SMPCs, which show higher modulus, strength and break elongation compared with unfilled PU matrix. And the SMPCs achieve a high recovery ratio. Auad et al. [100] also found the cellulose addition increases the melting temperature and crystallization temperature of PU soft segments, and also increases the crystallinity. Zhu et al. [101] and Luo et al. [102] found that the storage modulus of cellulose– PU composites shows a reversible variation in the wet-dry cycles. When immersing in water, the storage modulus gradually decreases, and shape recovery is triggered. In the cellulose–PU composites, the dry state of celluloses is used to fix the shape, and the entropy elasticity of the PU matrix is used to enable shape recovery.

2.5 Crystalline polymers

As mentioned, the shape memory mechanism of amorphous SMPs depends on the drastic change of relaxation time around the Tg. In addition to glass transition, the melting transition of materials provide another mechanism to achieve shape memory effects. Therefore, multiple shape memory effects can be achieved.

Luo and Mather [103] introduced the semicrystalline PCL fibers (with a diameter of 700 nm) into epoxy SMPs. The composites show two independent transitions in Figure 7a, respectively, the glass transition of epoxy matrix and the melting transition of PCL fibers. Correspondingly, the storage modulus curves show two drastic drops, respectively, in Tg of epoxy and melting temperature (Tm) of PCL. Correspondingly, three shapes can be programmed and recovered at temperature corresponding to the three plateaus of storage modulus curves. The typical shape programming and recovery process is shown in Figure 7b. The semicrystalline phase can also be used to achieved reversible shape memory effects by melting and re-crystallization [104, 105], but needs to be crosslinked with the molecule network. Therefore, reversible SMPs cannot be classified as composites. Please refer to ref. [44].

![Figure 7 (a) Schematic illustration of the typical temperature-dependent dynamic mechanical behavior of triple-SMPCs. (b) The shape programming and recovery process [103]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_007.jpg)

(a) Schematic illustration of the typical temperature-dependent dynamic mechanical behavior of triple-SMPCs. (b) The shape programming and recovery process [103]

Another application of crystalline polymers is to introduce the self-healing properties into SMPCs. After cracks initiating in the SMPCs, crystalline components can be melted by increasing temperature to heal the crack. Li and Upp [32] first put forward the idea combining SMPs with crystalline fillers. The healing process contains two steps in Figure 8a: the first is self-closing cracks by shape memory effects of matrix, and the second is healing cracks by melting crystalline fillers. For this method, Champagne et al. [106] argued that the lateral confinement levels, axial constraints, and heating times together influence the healing efficiency. Luo and Mather [107] embed thermoplastic PCL into epoxy matrix. After mechanical damage in Figure 8b, heating can simultaneously trigger the shape recovery of epoxy matrix and melt the PCL to re-bond the crack. By the heat treatment, a newly formed smooth surface is shown in Figure 8c.Wei et al. [108] used the same method to achieve self-healing. This concept is promising to design the next-generation self-healing materials.

2.6 Elastomers

Elastomer is an amorphous polymer with Tg far below the room temperature, and at the room temperature shows good ductility with low Young’s modulus and high failure strain. The elastomer can accelerate the shape recovery process, and tune the response temperature. Shirole et al. [109] embedded the electrospun PVA fibers into the polyether block amide elastomer (PEBA). PVA leads to materials displaying shape memory characteristics, and SMPCs with the higher content of PVAshow better shape fixity and recovery ratio. Similar method was used to fabricate degradable SMPCs, which are believed to have extensive applications in biomedical areas. Zhang et al. [110] embedded poly lactic acid (PLA) fibers into poly trimethylene carbonate elastomers, which can achieve degradable shape memory 3D scaffolds.

2.7 Multi-fillers

To improve the electrical and thermal conductivity of SMPCs, fillers with different scales and geometries were put together. Leng et al. [29] first introduced CNTs into CB filled SMPCs. The addition of CNTs acts as a long distance charge transporter by forming more contact points with CB, and the resistance of SMPCs is reduced by one order of magnitude. Lu et al. [111] used Ag nanoparticles, GO and carbon fiber to form a three-scale hybrid system, by which the electrical conductivity is gradually improved. Recently, Zhou et al. [112] fabricated graphite/AgNW/epoxy hybrid foams. The porous polymer foams are generated by the three-dimensional graphite structure, and AgNWs act as the continuous conductive network. Due to the connection between AgNWs and graphite, the resistance is gradually reduced, and the highest conductivity can be achieved by graphite with a 1:1 volume ratio of AgNWs and graphite. Recently, Guo et al. [113] used Al nanoparticles and chopped carbon fibers to reinforce SMPs, and found the SMPCs with 7 wt.% carbon fibers and 1 wt.% Al nanoparticles show the best mechanical and thermal properties.

The thermal conductivity and modulus of polymer matrix are usually far less than those of fillers, such as CNTs, CNFs and CB. Due to the drastic variation of properties, the weak interface between matrix and fillers limits the performance of SMPCs. To improve the interfacial properties, Raja et al. [114] used metal nanoparticles (Ag and Cu) to decorate CNFs, then fabricated CNT/ metal/PU SMPCs. The good dispersion of CNTs in PU is attributed to the enhanced interface between the CNTs and PU. By metal nanoparticles decorating, CNTs significantly improve the thermal and electrical conductivity of SMPCs. Similar methods are achieved by melt oxide, Gong et al. [115] self-assembled Fe3O4 on the cavity of β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) which is grafted on the CNTs to get functionalized CNTs, and then fabricated biodegradable SMPC fibers by electrospinning process. Due to the coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles, the fiber shows magnetism response. To improve the interface, Lu et al. [116] grafted aluminum (Al) nanoparticles onto carbon fibers by sputtering, modified the Al surface by siloxane groups, then imbedded carbon fibers into epoxy SMPs. The siloxane modified Al surfaces could improve the interfacial properties between carbon fibers and epoxy matrix, thus the SMPCs shows fast shape recovery.

In addition to metals, nanofillers with low dimensional structures can also enhance the interface between fillers and matrix. Lu et al. [117] grafted the graphene oxide onto carbon fibers by self-assembling, and the Van der Waals force connected the carbon fiber and graphene oxide in Figure 9a. The graphene grafted carbon fibers shown in Figure 9b, and porous structures can be observed from the surface of grafted graphene oxide in Figure 9c. The graphene oxides improve the conductivity, and the SMPCs achieve a fast shape recovery under a low driving voltage. A similar design was used to reinforce the light induced SMPCs [118]. CNTs and boron nitrides (BNs) were used to fill SMPCs, and high glass transition temperature and modulus can be obtained. In this hybrid system, CNTs are employed to improve the absorption of infrared light, and BNs facilitate the heat transfer from CNTs to the polymer matrix. By interfacial modification, infrared light induced shape recovery behaviors are accelerated.

![Figure 9 (a) Schematic illustration of the influence of GO. The van der Waals bonding connects the CO and carbon fibers. (b) The typical surface profile of the GO grafted onto the carbon fibers. (c) Porous structures of self-assembled GO on the carbon fiber mat. [117]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_009.jpg)

(a) Schematic illustration of the influence of GO. The van der Waals bonding connects the CO and carbon fibers. (b) The typical surface profile of the GO grafted onto the carbon fibers. (c) Porous structures of self-assembled GO on the carbon fiber mat. [117]

By adding multiple fillers, multi-functions can also be introduced into SMPCs, and due to the interaction between different fillers, the mechanical behaviors and shape recovery performance are gradually increased. Liu et. al. [119] developed biocompatible SMPCs by chemically cross-linking cholesteric cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), PCL and PEG. This SMPC network with PCL and PEG as soft segments and CNC nanofillers as cross-linkers, show an excellent thermo-responsive and water-responsive shape-memory effect. Recently, similar works have been reported by Bai and Chen [120]. Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), GO and citric acid (CA) were crosslinked to form a network. Strong hydrogen bonding between HEC and GO increases the mechanical properties of SMPCs. More importantly, the hydrogen bonds enable the SMPCs to achieve fast shape recovery in water (~14 s), and shape recovery even can be triggered in wet air. Similarly, to achieve fast recovery, Li et al. [121] developed elastic graphene aerogels with the aid of PAAm (in situ polymerization) during the gelation of a GO aqueous solution, then fabricated PU/graphene hybrid foams. The elastic graphene aerogels form an internal network inside the SMPCs. Due to its high porosity, good conductivity and flexibility, the SMPCs can achieve very fast shape recovery (~7s)when applying voltage. Qi et al. [122] used CB to reinforce the PLA/ PU blend, and a co-continuous structure was observed to be clear with increasing CB content. By this structure, the SMPCs shows an outstanding shape memory property because the continuous PU phase provided stronger recovery driving force. Recently, a similar continuous structure in PLA/PU/CNT SMPCs are reported by Liu et al. [123].

2.8 Summary: challenges and opportunities

The nanofillers in SMPCs can increase the mechanical properties, enable the SMP matrix activated by various energy inputs, and simultaneously incorporate multiple functions into the hybrid system. However, there are still some challenges to be overcome.

The most challenging problem in nanocomposites is the interface between nanofillers and matrix [124], which is more serious in SMPCs undergoing large or cyclic deformation. The weak interface between fillers and matrix reduces the mechanical properties of SMPCs, and also can lead to the Mullins effect of filled composites [125], which reduces the mechanical properties resulting from the first extension. For SMPCs, the Mullins effect also slows the shape recovery in Figure 3b [72]. The interface between fillers and matrix also changes the glass transition behaviors. The fillers reduce the mobility of the polymer segments, obstruct crystallization and polymerization, and sometimes destroy the shape memory effects [126]. With filler content increase, Tg measured by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) shifts first towards higher and then towards lower temperature as shown in Figure 2b [70].Wood et al. [127] attributed the origin of the shift towards the higher temperature to the weak interface, but attributed the subsequent shift towards the lower temperature to the stiffness increase by adding particles.

For conductive SMPCs, the filler content should be higher than the threshold. Allaoui et al. [128] figured out that the composites are conductive only when the volume fraction of fillers in the composites is higher than the threshold, above which a conductive network can be created insides the composites. Recently, Tarlton et al. [74] modeled the charge transport properties in CNT composites, and figured out that the aspect ratio of CNTs plays an important role. The larger the aspect ratio, the better the conductivity. Also for the electrically driving SMPC structures with complex geometries, due to the random distribution of fillers, it is very difficult to align the conductive fillers to form an electrical wire. Therefore, the testing electricity driven samples usually are designed and fabricated as a long-strip shape or a “U” shape.

In micro-scales, the SMPCs reinforced by nanofillers are discontinuous. This discontinuousness is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can be designed as a functional surface. For example, the nanofillers themselves have the potential applications to be used as micropillars to make a hydrophobic surface [129]. On the other hand, the reinforcement of nanofillers only exists when the measuring scale is large. When the measuring scale is smaller than the hole of networks, nonaffine deformation can be observed in SMPCs. We [130] have showed the obvious pileup effects around the indents left by a Berkovich tip on the composites surface. However, there is no obvious pile-up effect around the indents on the pure polymer surface. The size of the Berkovich tip is close to the hole size of the percolation network formed by tube fillers. Therefore, fillers cannot reinforce composites when the testing scale is close to or less than their length scale.

3 The patterned composites

To introduce more designability into SMPCs, researcher also tried to pattern the fillers. The preliminary attempt is to align fibers under the applied field, and the aligned CNTs can increase the modulus and conductivity, and fracture toughness along the fiber orientation [131]. Meng and Hu [132] used aligned CNT fillers to reinforce SMPCs, and found that the aligned CNTs could help storing and releasing elastic energy, and accelerate shape recovery. Yu et al. [133] aligned the CNTs under an external electrical field, and found that the electrical resistivity in SMPCs with aligned CNTs was reduced for more than 100 times compared with those with randomly distributed CNTs.

3.1 Nanopapers

CNTs/CNFs can be fabricated into thin membranes called as nanopapers (or buckypapers) [134]. CNTs/CNFs insides the nanopaper form a 3D conductive network. Compared with random fillers, nanopapers can be tailored to a specific geometry before using to fabricate composites. Also, the nanopapers can be used to fabricated multiple layer composites.

Lu et al. [135, 136] first fabricated SMPCs reinforced by CNF nanopapers. The nanopaper shows a continuous and compact network in Figure 10a, by which the in-plane conductivity is improved. With the nanopaper thickness increase, the conductivity of SMPCs increases, but the recovery ratio decreases. To improve recovery ratio, Lu et al. [137] blended nickel nanostrands with the CNT nanopaper, and vertically aligned nickel nanostrands in a magnetic field in Figure 10b. The Joule heat is generated insides the nanopaper when applying voltage, and the aligned nickel nanostrands facilitate the heat transfer from the nanopaper to SMP matrix. By this design, the recovery ratio is gradually increased to approximately 100%. The similar method was also used to vertically aligned CNTs in a magnetic field by Lu et al. [138]. Compared with the random hybrid SMPCs, the SMPCs with aligned CNTs shows fast shape recovery in Figure 10c. To enhance the interface strength between CNF nanopapers and polymer matrix, Lu et al. [139] grafted hexagonal BNs onto CNF nanopapers. By hexagonal BN particles, the electrical conductivity of SMPCs and thermal conductivity of matrix-filler interface are improved. Therefore, this approach accelerates the electro-activated shape recovery. Lu et al. [140] also fabricated SMPCs reinforced by multi-layer CNF nanopapers. The CNFs are self-assembled to form multi-layered nanopapers. The nanopapers and polymer matrix form two interpenetrating networks in the interface in Figure 10d. Thus, the bonding strength and thermal conductivity of the interface are gradually increased.

![Figure 10 (a) Morphologies and network structures of the CNF nanopaper [136]. (b) Schematically illustrating fabrication of the SMPCs with magnetically aligned nickel nanostrands [137]. (c) Curves show the recovery profiles of SMP nanocomposites with, respectively, aligned and randomly dispersed 8 wt. % magnetic CNTs under 12 V and 36 V voltage [138]. (d) Structures of multi-layered nanopapers in SMCs, and the good interface between SMPs and nanopapers [140]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_010.jpg)

(a) Morphologies and network structures of the CNF nanopaper [136]. (b) Schematically illustrating fabrication of the SMPCs with magnetically aligned nickel nanostrands [137]. (c) Curves show the recovery profiles of SMP nanocomposites with, respectively, aligned and randomly dispersed 8 wt. % magnetic CNTs under 12 V and 36 V voltage [138]. (d) Structures of multi-layered nanopapers in SMCs, and the good interface between SMPs and nanopapers [140]

In addition to CNTs/CNFs, Wang et al. [141] fabricated the reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanopaper, and used it to reinforce epoxy SMPs. The composites show excellent recoverability (~100%) after the first cycle, and the fast recovery (5 s) can be achieved by applying a low voltage of 6 V. Recently, Espinha et al. [142] fabricated self-assembled CNC nanopapers with photonic properties, and then embedded the CNC nanopaper into poly dodecanediol-cocitrate (PDDC-HD) SMPs. This trilayer composites keep the photonic properties of the CNC film, and the shape memory properties of PDDC-HD.

3.2 Surface patterns

The surface pattern is another choice to play as the energy converter. Compared with hybrid fillers, the surface pattern can be easily designed, fabricated and applied stimuli.

Recently, with the development of 4D printing [143, 144], patterned composites were also employed to switch a 2D sheet to a 3D structure. The SMPCs with surface patterns show excellent designability.

Liu et al. [145] designed a novel and concise approach to achieve self-folding of thin polymer sheets by light. The sheet is made of optically transparent and pre-strained PS, that would shrink in-plane if heated. Black ink patterns are painted on this PS surface, and play as light absorption to generate local heat. When PS is heated above its Tg, the pre-strain would recover, and thereby cause the planar sheet to fold into a 3D structure. The process is schematically illustrated in Figure 11a, and the 3D structures created by self-folding in Figure 11b. Recently, Liu et al. [146] replaced the black ink patterns by color ink patterns, which can be designed to selectively absorb a specific wavelength of light. Different colors can be used to control the sheet folding process to achieve sequential self-folding in Figure 11c. By combing the light absorption, the three-layer lotus starts folding in the internal layer, and then finishes in the outer layer in Figure 11d. In the folding process, temperature gradient was proven to play an important role. Davis et al. [147] figured out that the heat gradually transmits from the ink-pattern side to the other side of the sheet, and the temperature gradient gradually relaxes the strain across the sheet thickness. Therefore, folding is generated. Recently, a similar method is achieved by Yang et al. [148] by using rewritable CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite coating to absorb light. Felton et al. [149] and Cui et al. [150] achieved the folding by Joule heat of the surface coating electrode.

![Figure 11 (a) Schematic illustration of the self-folding approach, and (b) 3D structures created by self-folding of PS patterned by black inks [145]. (c) Schematic illustration of three-layer lotus by a small star (black hinges) placed on the top of a medium-sized star (red hinges) placed on top of the largest star (walnut-colored hinges), and (d) images of a folded structure [146]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_011.jpg)

(a) Schematic illustration of the self-folding approach, and (b) 3D structures created by self-folding of PS patterned by black inks [145]. (c) Schematic illustration of three-layer lotus by a small star (black hinges) placed on the top of a medium-sized star (red hinges) placed on top of the largest star (walnut-colored hinges), and (d) images of a folded structure [146]

Lu et al. [151, 152] patterned Au coating onto epoxy SMPs by magnetron sputtering. The Au electrode can achieve efficient electrical actuation and monitoring of shape recovery process. The thickness ofAu coating is only ~50 nm, and therefore flexibility of the epoxy substrate can be maintained in Figure 12a. When stretching, multiple cracks open on Au coating in Figure 12c. And when releasing, the cracks close. The open and close of cracks induce drastic changes of coating resistance, which can be used to monitor the substrate deformation [153]. Lu et al. [151] argued that there is a competing mechanism of resistance changes during the free recovery process, increasing temperature and closing cracks. For the programming shape memory substrate, the coating is in crack-open state. When applying voltage, Joule heating increases the temperature of Au coating, leading the resistance increase. Simultaneously, with the temperature increase, the prestrain would be gradually released, and crack closing decreases the resistance. Thus, the resistance shows a S-shape in Figure 12d, and the peak indicates the shape recovery starting point, and the valley indicates the finishing point. Recently, Zarek et al. [154] printed Ag electrode on the SMP matrix, and used the Joule heat to drive shape memory effects. Similarly, Wang et al. [155] printed CNT layers on SMPs.

![Figure 12 (a) SMP substrate coated with Au electrodes in a bending state [152]. SEM images of Au coating: (b) without deforming and (c) in bending state. (d) The variation of coating resistance with respect to time during the free recovery process under the driving voltage of 11.5 V, 13.3 V and 14.9 V [151]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_012.jpg)

3.3 Oriented fibers and laminas

The SMPs can be used as long fibers to reinforce elastomers. By the strain mismatch between elastomers and SMP fibers, folding can be designed and achieved.

Ge et al. [33] first put forward the idea of active composites with intelligence via a programmed lamina and a thermomechanical training process. The active composites are fabricated by 3D printing, and consist of glassy SMP fibers and elastomeric matrix. The composites contain two laminas in Figure 13a. One contains SMP fibers, but the other does not. The active composites can fold to a 3D structure, so called as 4D printing. To program the composites, temperature first needs to increase above Tg of glassy fibers, then composites need to be stretched, and finally the stretching in fiber can be fixed by reducing temperature below Tg by keeping loading. After programming, fibers become longer than elastomeric matrix. By removing the load, the composites would bend induced by strain mismatch of the two laminas. This process is schematically shown in Figure 13a. Ge et al. [156, 157] studied the influence factors to the 4D printing, such as hinge length and the angle between fibers and stretching directions. Robertson et al. [158] and Mao et al. [159] used PVA as the fibrous mat for shape fixing and PDMS as the soft matrix to achieve cold-programming anisotropic shape memory effects. The bilayer with different fiber directions would show different curled shapes. By the strain mismatch between elastomers and SMP fibers, complex 3D structures can be created from a composite sheet. Wu et al. [160] and Yuan et al. [161], respectively, designed a flexible hinge in Figure 13b and a folding body of the crane in Figure 13c.

![Figure 13 (a) A two-layer laminate with one layer filled by SMP fibers at a prescribed orientation and one layer of pure matrix material is printed, then heated, stretched, cooled, and released [33]. (b) The deformation behavior of the active “wave” shape [160]. (c) A printed folding body of the crane [161]. (d) Bending configurations of the bilayer laminate at elevated temperatures, without a programming process [162]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_013.jpg)

(a) A two-layer laminate with one layer filled by SMP fibers at a prescribed orientation and one layer of pure matrix material is printed, then heated, stretched, cooled, and released [33]. (b) The deformation behavior of the active “wave” shape [160]. (c) A printed folding body of the crane [161]. (d) Bending configurations of the bilayer laminate at elevated temperatures, without a programming process [162]

However, the aforementioned process needs to exert external force to pre-stretch the composites in the programming process in Figure 13a, which limits their application. Recently, Yuan et al. [162] used built-in mismatch induced by thermal expansion to replace the mismatch induced by external loading. In Figure 13d, the composites consist of two layers, elastomer and SMPs. The elastomer has a higher thermal expansion than SMPs. Upon heating, the composites would bend towards the SMPs by the larger expansion of elastomers, and the bending would be fixed by the SMP layer after cooling. Similarly, Ding et al. [144] used the strain mismatch generated during photopolymerization during 3D printing, and released the strain by heating. During printing, the residual strain in the elastomer is generated by the ink swelling the underlying cured layers in the weak-linked elastomer lamina [163].

3.4 Multi-blocks

The multi-block composites consist of several sections, and each section has the unique property. By appropriately choosing the stimulus, sequentially folding can be achieved.

He et al. [30] first put forward this method. They fabricated tri-block composites, respectively, CNT filled composites, net SMPs, and Fe3O4 filled composites, as shown in Figure 14a. The three sections use identical epoxy SMPs to get strong interfaces. CNT filled composites can absorb the radiofrequency with a frequency of 13.56 MHz, and Fe3O4 filled composites absorb the radiofrequency (RF) with 296 kHz. Thus, by apply RF with different frequency, the SMPCs would be activated sequentially. Similar method has been achieved by Li et al. [164] in Figure 14b. Differently, they used magnetic field of 30 kHz to trigger the section filled by Fe3O4 particles.

![Figure 14 (a) Experimental demonstration of the multi-block composite shape recovery. The sample was subjected to RF fields of 13.56 MHz and 296 kHz sequentially [30]. (b) Experimental demonstration of the selective shape memory recovery. The sample was subjected to magnetic field of 30 kHz and a RF field of 13.56 MHz sequentially [164]. (c) The sequential shape recovered of interlocking structures by different hinges with different relaxation times [165]. (d) 3D folding structures mimicking the USPS mailbox [166]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_014.jpg)

(a) Experimental demonstration of the multi-block composite shape recovery. The sample was subjected to RF fields of 13.56 MHz and 296 kHz sequentially [30]. (b) Experimental demonstration of the selective shape memory recovery. The sample was subjected to magnetic field of 30 kHz and a RF field of 13.56 MHz sequentially [164]. (c) The sequential shape recovered of interlocking structures by different hinges with different relaxation times [165]. (d) 3D folding structures mimicking the USPS mailbox [166]

In addition to selective energy conversions, different sections with different Tg can also be used to achieved sequentially folding. Yu et al. [165] designed the interlocking structure with several hinges. Each hinge with a different Tg. When immersing in hot water, the hinges with a lower Tg would recover faster. Consequently, the shape recoveries along the interlocking structure are successively triggered in Figure 14c. Based on this method, Mao et al. [166] fabricated mail box. By properly selecting the material of each hinge, a 2D sheet can sequentially fold to a mail box in Figure 14d. A similar work of sequentially folding recently has been finished by Li et al. [167].

3.5 Summary: challenges and opportunities

As the advanced manufacture technology developing, more and more composites with complex geometries can be fabricated. That provides an opportunity to develop more interesting shape memory composites, and to achieve more complex shape changes. In addition to the interface problem which also exists in hybrid composites, lack of effective prediction method is a tough challenge to design SMPCs with fine micro-structures.

Until now, most of modeling results are based on the finite element method (FEM). For patterns with complex geometries, it is difficult to get the analytic solutions. Compared with FEM solutions, the analytic solutions provide clearer trends, and have more guiding meanings. One famous example is the Eshelby’s inclusion problems, which give the analytic solutions of ellipsoidal inclusion in an infinite field [168]. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to be extended to the non-ellipsoidal inclusion in a finite field. Therefore, new theory needs to be developed to predict the behaviors of pattern SMPCs. Instead of pursuing general solutions, it is more practical to get the problem-oriented solution. In a specific problem, more assumptions can be introduced to get an approximate theoretical analysis. One famous example is the analytic solution of staggered composites given by Ji and Gao [169]. They simplified the deformation of staggered composites as the tension-shear chain model, based on which they gave an accurate theoretical prediction. Recently, based on this simplification, Zhang et al. [170] theoretically analyzed the complex modulus of staggered composites, which is closely related to the shape memory effects of polymer [13], and inspired us to tune the damping by design of fillers’ arrangements [171]. For the SMPCs with fine micro-structures, a lot of works need to be finished to provide a theoretical support in the field of the design and optimization.

4 Applications and prospects

Over the past few decades, stimulus-responsive SMPCs have been proven to have a lot of applications. In medical area, biocompatible and biodegradable SMPCs can be used as medical devices [9], or can be used to control the drag releasing process [172, 173]. In the aerospace industry, SMPCs can be employed to fabricate deployable structures and morphing structures [10]. In the micro-device filed, SMPCs can be used to tune the surface morphology [8, 129], and this properties can be further used to control the wettability [174], or the optical diffraction [175]. Several excellent reviews have summarized these applications [44, 48, 53, 56, 176, 177, 66], and here we don’t repeat them.

In the past five years, 3D-printing technology [179, 180], flexible electronics [85], bio-inspired composites [181] and metamaterials [182] gain great progress. Due to the deformability of stimulus-responsive SMPs, there are several binding points between these three fields and SMPCs. Here, we summarize the newly appeared applications, and look to the prospects.

4.1 Shape memory structures by the 3D printing technology

3D printing (also termed as additive manufacturing) based on melting or photonic curing materials, can rapidly fabricate 3D structures based on the computer-aided designs. The amazing thing is to use 3D-printing technology to fabricate the structures, which are hard to be fabricated previously. Recently, 3D lattice structures [183], composites with aligned fibers [184, 185], materials with gradient properties [186], and conductive wires [187, 188] can be fabricated by 3D printing technology. By combining the 3D printing technology with SMPCs, very complex shape changes and self-driving process can be achieved.

Zarek et al. [154] used a 3D digital light processing (DLP) printer to generate 3D shape memory structures. After curing, the photocurable resin has a thermally triggered shape memory effect. Ge et al. [189] developed a multi-material 3D printer with tailorable material properties. By choosing different UV curable resins in Figure 15a, Tg can be tailed from −50∘C to 180∘C. Since the multimaterials are all benzyl methacrylate (BMA) based, the interface between multi-materials is very strong. The pre-deformed complex structures can recover their original shape upon heating in Figure 15b. Wei et al. [190] incorporated Fe3O4 particles into the UV curable PCL ink, and fabricated very small shape memory structures, which can be triggered by remote heating in an alternating magnetic field. Figure 15c shows the shape memory cycles by heat stimulus. Yu et al. [191] printed Eiffel tower by SMPCs with epoxy-acrylate hybrid photopolymers, which shows good shape fixity, shape recovery performance, and cyclic stability. Recently, Xiao et al. [192] printed highly stretchable, shape-memory, and self-healing elastomer toward novel morphing structures. The exciting progress shows the importance of advanced manufacture for the development of SMPCs.

4.2 Shape memory structures with built-in electronic devices

With the development of composite manufacture technology and design methods, the bounds between functional materials and structural materials are broken. By compositing, electronic devices can be built in composites. The SMPs andSMPCs can be used to change the deformation of structures, during which the electronic devices keep working. Lee et al. [193] used shape memory PUto extend the lift times of nanogenerators and guarantee their performance. By raising temperature to trigger the healing process, the PU micro-pyramid pattern recovers its initial shape, and correspondingly performances of the device increase back to its original state. Deng et al. [194] fabricated a shape memory supercapacitor by winding aligned carbon nanotube sheets on a shape memory PU substrate. In addition to improving flexibility and stretchability of the supercapacitor, the deformed shape can be frozen as expected and recovered when required. They show that electrochemical performances are well-maintained during deformation, at the deformed state and after the recovery.

Combining shape memory structures and built-in electronics can create infinite possibilities. For example, the supporting techniques related to the self-folding origami energy harvesting system are maturing. The self-folding was thought as one of the most important applications of SMPCs. However, due to the less output force of SMPCs, traditional folding hinges were designed to be too large, and therefore had large deadweight losses, which hinder their commercial applications. Recently, development in shape memory Kirigami/Origami structures solves the problem. Ding et al. [144] used decentralized dual-material composite beams to replace the hinge of traditional deployable hinges, to achieve open lattice structures upon heating in Figure 16a. This design bases on the built-in strain mismatch during photopolymerization, and strain releasing and fixing by shape memory effects. Due to the decentralized beams, the deadweight losses are gradually reduced, and the architecture’s flexibility is also increased. Recently, Kirigami/Origami structures have been successfully used in reflective films controlled by shape memory alloy [195] in Figure 16b, and crystalline GaAs solar cells [196] in Figure 16c. Simultaneously, with the development of polymer based dye sensitized solar cells [197, 198], the flexible solid-state battery [199] and the nanogenerators [200], it is very promising to develop a self-folding origami energy harvesting system based on shape memory composites with built-in polymer based solar cells and batteries, which has huge commercial opportunities.

4.3 Shape memory bio-inspired composites and metamaterials

In the biological materials with excellent mechanical properties, from honeycomb [201] and spider silk [202] to human teeth [203] and bone [204], periodic structures were found to play an important role to enhance the mechanical properties [182, 205]. To mimic this, researchers recently designed a lot of composite materials to achieve different functions, such as tuning the damping [170], increasing the fracture toughness [206], improving impact resistance [207, 208], and tailing buckling behaviors [209, 210]. Like animals and plants, SMPs and SMPCs can response to the environment stimuli.

Restrepo et al. [211, 212] fabricated two kinds of honeycomb structures by using epoxy based SMPs: one is a bending dominated honeycomb with a hexagonal unit cell in Figure 17a, and the other is stretching dominated honeycomb with a kagome unit cell. By this structure, a significant variation in the mechanical properties can be gained by a small programmed strain. They attributed the significant property variation to the morphological imperfection during fabrication in Figure 17a. Figure 17b shows the influence of programmed strain on the effective mechanical properties. By Restrepo’s design, a large change of mechanical properties can be triggered by shape memory effect. By combining SMPs with more bio-inspired composites, more composites with excellent properties can be fabricated.

![Figure 17 (a) Defects of shape memory honeycomb structures from fabrication process: corner fillets, broken walls, joint misalignments and thickness variations. The inset shows one testing sample. (b) In-plane compression stress-strain curves of the bending dominated honeycomb, in which samples programed in the direction X1 and tested in the direction X2. [211] (c) Shape memory cylindrical shells by uniform metamaterials, design, simulation, the experimental result, and the shape switch in the projection plan [221]](/document/doi/10.1515/ntrev-2019-0031/asset/graphic/j_ntrev-2019-0031_fig_017.jpg)

(a) Defects of shape memory honeycomb structures from fabrication process: corner fillets, broken walls, joint misalignments and thickness variations. The inset shows one testing sample. (b) In-plane compression stress-strain curves of the bending dominated honeycomb, in which samples programed in the direction X1 and tested in the direction X2. [211] (c) Shape memory cylindrical shells by uniform metamaterials, design, simulation, the experimental result, and the shape switch in the projection plan [221]

Recently, researchers also designed and fabricated metamaterials, which have a property that has not been found in nature. The metamaterials consist of repeating units, and can be used to achieve auxetics [213, 214], programmable mechanical properties [215], and wave guidance [216]. These tunable properties rely on deformation, geometries and properties of the repeating unit [217, 218, 219]. For examples, Liu and Zhang [220] 3D printed the meshes with auxetics. By different auxetics in different places, the normal cylindrical shells can be programmed to the irregular cylindrical shells in Figure 17c [221]. By combining the structural design with the multimaterial 3D printing technology, Zhao et al. achieved the thermally tunable auxetic behaviors [222, 223]. Therefore, it is very promising to get environment responsive metamaterials by combining with SMPCs.

5 Summary

In this paper, we briefly review the recent progress of SMPCs. To make a clear discussion, we manually divide SMPCs into two classes, hybrid composites and patterned composites. The hybrid SMPCs are reinforced by random distributed nanofillers. By reinforcement, mechanical properties of SMPs can be improved, novel stimulus methods can be incorporated, shape recovery can be accelerated, and multi-functions can be introduced. The filler’s geometries, modulus, volume contents, surface properties, and distributions work together to influence the properties of SMPCs, and can be used as design and optimization parameters. The biggest progress over the past five years has been made in the patterned SMPCs with the development of advanced manufacture technologies. The patterned SM-PCs have better electrical and mechanical properties compared with hybrid SMPCs. More importantly, the patterned fillers provide designability to achieve a specific function. Patterned SMPCs can achieve self-folding from a 2D sheet to a 3D structure. By properly designing triggered positions, sequentially folding can be achieved. Recently, with the development of 3D printing manufacture technology, flexible electronics, and advanced composites, new applications and bonding points of SMPCs appear continuously. Predictably, more excellent SMPCs products will walk into people’s lives.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge the financial supports by the National Key R&D Program of China under grant numbers 2017YFB1201104, and the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11422217 and 11672342).

References

[1] Schetky L.M., Shape-Memory Alloys, 1982, Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Lendlein A., Jiang H., Junger O., Langer R., Light-induced shape-memory polymers, Nature, 2005, 434(7035), 879.10.1038/nature03496Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Rousseau I.A., Mather P.T., Shape memory effect exhibited by smectic-C liquid crystalline elastomers, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2003, 125(50), 15300-1.10.1021/ja039001sSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Yakacki C., Saed M., Nair D., Gong T., Reed S., Bowman C., Tailorable and programmable liquid-crystalline elastomers using a two-stage thiol–acrylate reaction, RSC Adv., 2015, 5(25), 18997-9001.10.1039/C5RA01039JSearch in Google Scholar

[5] Behl M., Kratz K., Zotzmann J., Nöchel U., Lendlein A., Reversible bidirectional shape-memory polymers, Adv. Mater., 2013, 25(32), 4466-9.10.1002/adma.201300880Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Lai A., Du Z., Gan C. L., Schuh C. A., Shape memory and superelastic ceramics at small scales, Science, 2013, 341(6153), 1505-8.10.1126/science.1239745Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] YangW.G., Lu H., HuangW.M., Qi H.J.,Wu X.L., Sun K.Y., Advanced shape memory technology to reshape product design, manufacturing and recycling, Polymers, 2014, 6(8), 2287-308.10.3390/polym6082287Search in Google Scholar

[8] Wang Z., Hansen C., Ge Q., Maruf S.H., Ahn D.U., Qi H.J., et al, Programmable, pattern-memorizing polymer surface, Adv. Mater., 2011, 23(32), 3669-73.10.1002/adma.201101571Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Yakacki C.M., Shandas R., Lanning C., Rech B., Eckstein A., Gall K., Unconstrained recovery characterization of shape-memory polymer networks for cardiovascular applications, Biomaterials, 2007, 28(14), 2255-63.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.030Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Lan X., Liu Y., Lv H.,Wang X., Leng J., Du S., Fiber reinforced shape-memory polymer composite and its application in a deployable hinge, Smart Mater. Struct., 2009, 18(2), 024002.10.1088/0964-1726/18/2/024002Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhao Q., Zou W., Luo Y., Xie T., Shape memory polymer network with thermally distinct elasticity and plasticity, Sci. Adv., 2016, 2(1), e1501297.10.1126/sciadv.1501297Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Nguyen T.D., Qi H.J., Castro F., Long K.N., A thermoviscoelastic model for amorphous shape memory polymers: incorporating structural and stress relaxation, J. Mech. Phys. Solids., 2008, 56(9), 2792-814.10.1016/j.jmps.2008.04.007Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yu K., Xie T., Leng J., Ding Y., Qi H.J., Mechanisms of multi-shape memory effects and associated energy release in shape memory polymers, Soft Matter, 2012, 8(20), 5687-95.10.1039/c2sm25292aSearch in Google Scholar

[14] Lu H., Wang X., Yao Y., Fu Y.Q., A ‘frozen volume’ transition model and working mechanism for the shape memory effect in amorphous polymers, Smart Mater. Struct., 2018, 27(6), 065023.10.1088/1361-665X/aab8afSearch in Google Scholar

[15] Wang X., Lu H., Shi X., Yu K., Fu Y.Q., A thermomechanical model of multi-shape memory effect for amorphous polymer with tunable segment compositions, Compos. Part B- Eng, 2019, 160, 298-305.10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.10.048Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lu H., Wang X., Yu K., Fu Y. Q., Leng J., A thermodynamic model for tunable multi-shape memory effect and cooperative relaxation in amorphous polymers, Smart Mater. Struct., 2019, 28(2), 025031.10.1088/1361-665X/aaf528Search in Google Scholar

[17] Wang X., Jian W., Lu H., Lau D., Fu Y.Q., Modeling Strategy for Enhanced Recovery Strength and a Tailorable Shape Transition Behavior in Shape Memory Copolymers, Macromolecules, 2019, 52(16), 6045-54.10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00992Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang X., Liu Y., Lu H., Wu N., Hui D., Fu Y.Q., A coupling model for cooperative dynamics in shape memory polymer undergoing multiple glass transitions and complex stress relaxations, Polymer, 2019, 181, 121785.10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121785Search in Google Scholar

[19] Aoki D., Teramoto Y., Nishio Y., SH-containing cellulose acetate derivatives: preparation and characterization as a shape memory-recovery material, Biomacromolecules, 2007, 8(12), 3749-57.10.1021/bm7006828Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Qi X., Yao X., Deng S., Zhou T., Fu Q., Water-induced shape memory effect of graphene oxide reinforced polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposites, J. Mater. Chem. A., 2014, 2(7), 2240-9.10.1039/C3TA14340FSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Yu K., Ge Q., Qi H. J., Reduced time as a unified parameter determining fixity and free recovery of shape memory polymers, Nat. Commun., 2014, 5, 3066.10.1038/ncomms4066Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Xiao R., Nguyen T.D., An effective temperature theory for the nonequilibrium behavior of amorphous polymers., J. Mech. Phys. Solids., 2015, 82, 62-81.10.1016/j.jmps.2015.05.021Search in Google Scholar

[23] Liu C., Lu H., Li G., Hui D., Fu Y.Q., A ‘cross-relaxation effects’ model for dynamic exchange of water in amorphous polymer with thermochemical shape memory effect, J. Phys. D Appl. Phys., 2019, 52(34), 345305.10.1088/1361-6463/ab2860Search in Google Scholar

[24] Luo C., Lei Z., Mao Y., Shi X., ZhangW., Yu K., Chemomechanics in the Moisture-Induced Malleability of Polyimine-Based Covalent Adaptable Networks, Macromolecules, 2018, 51(23), 9825-38.10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02046Search in Google Scholar

[25] Mao Y., Chen F., Hou S., Qi H.J., Yu. K., A viscoelastic model for hydrothermally activated malleable covalent network polymer and its application in shape memory analysis, J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 2019, 127, 239-65.10.1016/j.jmps.2019.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[26] Lei M., Yu K., Lu H., Qi H.J., Influence of structural relaxation on thermomechanical and shape memory performances of amorphous polymers, Polymer, 2017, 109, 216-28.10.1016/j.polymer.2016.12.047Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kim B., Lee M. G., Lee Y.P., Kim Y., Lee G., An earthworm-like micro robot using shape memory alloy actuator, Sensor Actuat. A-Phys., 2006, 125(2), 429-37.10.1016/j.sna.2005.05.004Search in Google Scholar

[28] Ohki T., Ni Q.Q., Ohsako N., Iwamoto M., Mechanical and shape memory behavior of composites with shape memory polymer, Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci., 2004, 35(9), 1065-73.10.1016/j.compositesa.2004.03.001Search in Google Scholar

[29] Leng J., Lv H., Liu Y., Du S., Electroactivate shape-memory polymer filled with nanocarbon particles and short carbon fibers, Appl. Phys. Lett., 2007, 91(14), 144105.10.1063/1.2790497Search in Google Scholar

[30] He Z., Satarkar N., Xie T., Cheng Y. T., Hilt J. Z., Remote controlled multishape polymer nanocomposites with selective radiofrequency actuations, Adv. Mater., 2011, 23(28), 3192-6.10.1002/adma.201100646Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Hribar K.C., Metter R.B., Ifkovits J.L., Troxler T., Burdick J.A., Light-Induced Temperature Transitions in Biodegradable Polymer and Nanorod Composites, Small, 2009, 5(16), 1830-4.10.1002/smll.200900395Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Li G., Uppu N., Shape memory polymer based self-healing syntactic foam: 3-D confined thermomechanical characterization, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2010, 70(9), 1419-27.10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.04.026Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ge Q., Qi H.J., Dunn M.L., Active materials by four-dimension printing, Appl. Phys. Lett., 2013, 103(13), 131901.10.1063/1.4819837Search in Google Scholar

[34] Lendlein A., Kelch S., Shape-memory polymers, Angwe. Chem. Int. Edit., 2002, 41(12), 2034-57.10.1002/1521-3773(20020617)41:12<2034::AID-ANIE2034>3.0.CO;2-MSearch in Google Scholar

[35] Liu C., Qin H., Mather P.T., Review of progress in shape-memory polymers, J. Mater. Chem., 2007, 17(16), 1543-58.10.1039/b615954kSearch in Google Scholar

[36] Rousseau I.A., Challenges of shape memory polymers: A review of the progress toward overcoming SMP’s limitations, Polym. Eng. Sci., 2008, 48(11), 2075-89.10.1002/pen.21213Search in Google Scholar

[37] Mather P.T., Luo X., Rousseau I.A., Shape memory polymer research, Ann. Rev. Mater. Res., 2009, 39, 445-71.10.1146/annurev-matsci-082908-145419Search in Google Scholar

[38] Wagermaier W., Kratz K., Heuchel M., Lendlein A., 2009, Shape Memory Polymers: Springer, 97-145.10.1007/12_2009_25Search in Google Scholar

[39] Leng J., Lu H., Liu Y., Huang W.M., Du S., Shape-memory polymers—a class of novel smart materials, MRS Bull., 2009, 34(11), 848-55.10.1557/mrs2009.235Search in Google Scholar

[40] Xie T., Recent advances in polymer shape memory, Polymer, 2011, 52(22), 4985-5000.10.1016/j.polymer.2011.08.003Search in Google Scholar

[41] Hu J., Zhu Y., Huang H., Lu J., Recent advances in shape–memory polymers: Structure, mechanism, functionality, modeling and applications, Prog. Polym. Sci., 2012, 37(12), 1720-63.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.06.001Search in Google Scholar

[42] Kumar K.S., Biju R., Nair C.R., Progress in shape memory epoxy resins, React. Funct. Polym., 2013, 73(2), 421-30.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2012.06.009Search in Google Scholar

[43] Meng H., Mohamadian H., Stubblefield M., Jerro D., Ibekwe S., Pang S. S. et. al., Various shape memory effects of stimuli-responsive shape memory polymers, Smart Mater. Struct., 2013, 22(9), 093001.10.1088/0964-1726/22/9/093001Search in Google Scholar

[44] Zhao Q., Qi H. J., Xie T., Recent progress in shape memory polymer: New behavior, enabling materials, and mechanistic understanding, Prog. Polym. Sci., 2015, 49, 79-120.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.04.001Search in Google Scholar

[45] Hager M.D., Bode S., Weber C., Schubert U.S., Shape memory polymers: past, present and future developments, Prog. Polym. Sci., 2015, 49, 3-33.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.04.002Search in Google Scholar

[46] Ratna D., Karger Kocsis J., Recent advances in shape memory polymers and composites: a review, J. Mater. Sci., 2008, 43(1), 254-69.10.1007/s10853-007-2176-7Search in Google Scholar

[47] Meng Q., Hu J., A review of shape memory polymer composites and blends, Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci., 2009, 40(11), 1661-72.10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.08.011Search in Google Scholar

[48] Meng H., Li G., A review of stimuli-responsive shape memory polymer composites, Polymer, 2013, 54(9), 2199-221.10.1016/j.polymer.2013.02.023Search in Google Scholar

[49] Lu H., Lei M., Yao Y., Yu K., Fu Y.Q., Shape memory polymer nanocomposites: nano-reinforcement and multifunctionalization, Nanosci. Nanotech. Lett., 2014, 6(9), 772-86.10.1166/nnl.2014.1842Search in Google Scholar

[50] Xie F., Huang L., Leng J., Liu Y., Thermoset shape memory polymers and their composites, J. Intel. Mater. Syst. Struct., 2016, 27(18), 2433-55.10.1177/1045389X16634211Search in Google Scholar

[51] Ponnamma D., El-Gawady Y.M.H., Rajan M., Goutham S., Rao K.V., Al-Maadeed M.A.A., 2017, Smart Polymer Nanocomposites: Springer, 321-43.10.1007/978-3-319-50424-7_12Search in Google Scholar

[52] Wang W., Liu Y., Leng J., Recent developments in shape memory polymer nanocomposites: Actuation methods and mechanisms, Coordin. Chem. Rev., 2016, 320, 38-52.10.1016/j.ccr.2016.03.007Search in Google Scholar

[53] Mu T., Liu L., Lan X., Liu Y., Leng J., Shape memory polymers for composites, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2018, 160, 169-98.10.1016/j.compscitech.2018.03.018Search in Google Scholar

[54] Liu Y., Lv H., Lan X., Leng J., Du S., Review of electro-active shape-memory polymer composite, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2009, 69(13), 2064-8.10.1016/j.compscitech.2008.08.016Search in Google Scholar

[55] Huang W., Yang B., Zhao Y., Ding Z., Thermo-moisture responsive polyurethane shape-memory polymer and composites: a review, J. Mater. Chem., 2010, 20(17), 3367-81.10.1039/b922943dSearch in Google Scholar

[56] Leng J., Lan X., Liu Y., Du S., Shape-memory polymers and their composites: stimulus methods and applications, Prog. Mater. Sci., 2011, 56(7), 1077-135.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2011.03.001Search in Google Scholar

[57] Liu T., Zhou T., Yao Y., Zhang F., Liu L., Liu Y., et al, Stimulus methods ofMulti-functional Shape Memory Polymer Nanocomposites: A review, Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci, 2017, 100, 20-30.10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.04.022Search in Google Scholar

[58] Nguyen T.D., Modeling shape-memory behavior of polymers, Polym. Rev., 2013, 53(1), 130-52.10.1080/15583724.2012.751922Search in Google Scholar

[59] El Feninat F., Laroche G., Fiset M., Mantovani D., Shape memory materials for biomedical applications, Adv. Eng. Mater., 2002, 4(3), 91-104.10.1002/1527-2648(200203)4:3<91::AID-ADEM91>3.0.CO;2-BSearch in Google Scholar

[60] Hu J., Chen S., A review of actively moving polymers in textile applications, J. Mater. Chem., 2010, 20(17), 3346-55.10.1039/b922872aSearch in Google Scholar

[61] Lendlein A., Behl M., Hiebl B., Wischke C., Shape-memory polymers as a technology platform for biomedical applications, Exp. Rev. Med. Devi., 2010, 7(3), 357-79.10.1586/erd.10.8Search in Google Scholar

[62] Wischke C., Lendlein A., Shape-memory polymers as drug carriers – A multifunctional system., Pharm. Res., 2010, 27(4), 527-9.10.1007/s11095-010-0062-5Search in Google Scholar

[63] Safranski D.L., Smith K.E., Gall K., Mechanical requirements of shape-memory polymers in biomedical devices, Polym. Rev., 2013, 53(1), 76-91.10.1080/15583724.2012.752385Search in Google Scholar

[64] Huang W.M., Song C., Fu Y.Q., Wang C.C., Zhao Y., Purnawali H. et. al., Shaping tissue with shape memory materials, Adv. Drug Deliver. Rev., 2013, 65(4), 515-35.10.1016/j.addr.2012.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[65] Kuder I.K., Arrieta A.F., RaitherW.E., Ermanni P., Variable stiffness material and structural concepts for morphing applications, Prog. Aerosp. Sci., 2013, 63, 33-55.10.1016/j.paerosci.2013.07.001Search in Google Scholar

[66] Liu Y., Du H., Liu L., Leng J., Shape memory polymers and their composites in aerospace applications: a review, Smart Mater. Struct., 2014, 23(2), 023001.10.1088/0964-1726/23/2/023001Search in Google Scholar

[67] Luo J.J., Daniel I.M., Characterization and modeling of mechanical behavior of polymer/clay nanocomposites, Compos. Sci. Technol., 2003, 63(11), 1607-16.10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00060-5Search in Google Scholar

[68] Gall K., Dunn M. L., Liu Y., Finch D., Lake M., Munshi N.A., Shape memory polymer nanocomposites, Acta Mater., 2002, 50(20), 5115-26.10.1016/S1359-6454(02)00368-3Search in Google Scholar

[69] Xu B., Fu Y.Q., Ahmad M., Luo J., Huang W.M., Kraft A. et. al., Thermo-mechanical properties of polystyrene-based shape memory nanocomposites, J. Mater. Chem., 2010, 20(17), 3442-8.10.1039/b923238aSearch in Google Scholar

[70] Dong Y., Ni Q.Q., Fu Y., Preparation and characterization of waterborne epoxy shape memory composites containing silica, Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci, 2015, 72, 1-10.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.01.018Search in Google Scholar

[71] Le H., Kolesov I., Ali Z., Uthardt M., Osazuwa O., Ilisch S. et. al., Effect of filler dispersion degree on the Joule heating stimulated recovery behaviour of nanocomposites, J. Mater. Sci., 2010, 45(21), 5851-9.10.1007/s10853-010-4661-7Search in Google Scholar

[72] Yu K., Ge Q., Qi H.J., Effects of stretch induced softening to the free recovery behavior of shape memory polymer composites, Polymer, 2014, 55(23), 5938-47.10.1016/j.polymer.2014.06.050Search in Google Scholar

[73] Mullins L., Softening of rubber by deformation, Rubber Chem. Technol., 1969, 42(1), 339-62.10.5254/1.3539210Search in Google Scholar

[74] Tarlton T., Brown J., Beach B., Derosa P.A., A stochastic approach towards a predictive model on charge transport properties in carbon nanotube composites, Compos. Part B- Eng, 2016, 100, 56-67.10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.06.021Search in Google Scholar

[75] Taherzadeh M., Baghani M., Baniassadi M., Abrinia K., Safdari M., Modeling and homogenization of shape memory polymer nanocomposites, Compos. Part B- Eng., 2016, 91, 36-43.10.1016/j.compositesb.2015.12.044Search in Google Scholar

[76] Liu Y., Zhao J., Zhao L., Li W., Zhang H., Yu X. et. al., High performance shape memory epoxy/carbon nanotube nanocomposites, ACS Appl. Mater. Inter., 2015, 8(1), 311-20.10.1021/acsami.5b08766Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[77] Cho J.W., Kim J.W., Jung Y.C., Goo N.S., Electroactive shape-memory polyurethane composites incorporating carbon nanotubes, Macromol. Rapid Comm., 2005, 26(5), 412-6.10.1002/marc.200400492Search in Google Scholar

[78] Xiao Y., Zhou S., Wang L., Gong T., Electro-active shape memory properties of poly ϵ-caprolactone)/functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposite, ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2010, 2(12), 3506-14.10.1021/am100692nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[79] Fei G., Li G., Wu L., Xia H., A spatially and temporally controlled shape memory process for electrically conductive polymer– carbon nanotube composites, Soft Matter, 2012, 8(19), 5123-6.10.1039/c2sm07357aSearch in Google Scholar