Abstract

This work proposes an approach to fabricate flexible transparent ultraviolet (UV)-shielding membrane by casting method, which uniformly disperses pristine zinc oxide nanoparticles (NPs) in low-density polyethylene (LDPE). The critical conditions for film fabrication, such as casting temperature, LDPE concentration in the solution, dissolution time, NP concentration, and post hot press cooling processes, are systematically studied. It is found that the casting temperature needs to be close to the melting temperature of LDPE, namely, 115°C, so that transparent film formation without cracks can be guaranteed. NP agglomerates are suppressed if the polymer concentration is controlled below 6%. For good dispersion of NPs, LDPE has to be swelled or unentangled enough in the solution (close to 200 h dissolution time), and then the NP agglomerates can be diminished due to the diffusion of the NPs into the polymer gel (322 h dissolution time). When the NPs are well-dispersed in the LDPE film, the film can completely shield UV light while allowing high transmissivity for the visible light. As the concentration of NPs in the film increases from 4 to 6%, the transmissivity of the film decreases, the tensile strength increases, and the tensile failure strain decreases.

1 Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) are popularly utilized for the property promotion and functionalization of polymeric materials for advantageous electrical, optical, or mechanical properties [1,2,3] in more than past two decades. Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs have been used in developing functional devices, catalysts, pigments, optical materials, cosmetics, and UV absorbers [4,5,6]. The biggest challenge is how to uniformly disperse NPs in polymers for better functional performances [7]. If there is serious NP agglomeration in composites, the functions of inorganic–organic composites would be hindered as Li and coworkers reported [8]. UV photon is high-energy thermal waves [9], which reach the earth’s surface more than before because of the increased ozone depletion as indicated by Yoo et al. [10] and Xie et al. [11]. The UV photons can not only cause serious injuries to the skin which might eventually result in skin cancer as Hacker et al. reported [12], but also provide radiative heat which may consume much energy to regulate temperature in space [13]. More and more attention has been paid for shielding UV photons in recent years [14]. Feng et al. [15] and Li et al. [16] fabricated transparent UV-shielding composites using cellulose, though the material is hard for large-scale production. Han et al. [17] used 60 nm NPs mixed into a polymer, and finally the NPs were agglomerated into 600 nm clusters. Complete UV-shielding performance would appear when the NP concentration reached above 7%, which would influence the transparency to visible light. Wang et al. [18] fabricated similar functional materials by mixing inorganic NPs with polymers, which also had a high NP concentration about 0.5 mol/mL. UV-shielding materials also can be a good candidate for passive cooling, which have the cooling function without any kinds of energy input. Li et al. fabricated opaque textile for outdoor personal cooling by shielding UV and high-energy visible lights [19]. Gamage et al. have shown that UV-shielding and visible transparent materials are good candidates for passive cooling to save energy consumption [20].

The most common methods reported fabricating UV-shielding materials are combining polymer and inorganic semiconductor NPs. In order to improve the compatibility between NPs and polymers, surface treatments have been applied to modify the surface properties of NPs [21]. However, these treatments have the potential to induce adverse effects on the catalytic, optical, or magnetic properties of the surface-treated NPs. This may greatly influence the intended performance of the composites. Jiang et al. reported that the coating processes of NP may be phased out because of their possible high-cost or harmful effects [22]. El-Naggar et al. employed the core/shell structure to improve the agglomeration of ZnO NPs; however, the characteristic absorption peaks of the NPs were shielded [23]. In addition, Hong et al. reported reduced catalytic activity of coated ZnO NPs [24]. Therefore, direct doping of pristine NPs into the polymer could be preferable if one could achieve uniform dispersion of the NPs in the polymer when optimal mixing strategies could be adopted [25]. Mackay et al. reported that thermodynamically stable dispersion of NPs into a polymeric liquid enhanced the dispersion of NPs by increasing the enthalpy gain of the solution system [26].

Solution methods relatively easily achieve an even dispersion of NPs in polymers, especially those without a melting temperature or with a high molten viscosity as reported by Zarrinkhameh et al. [27]. In recent decades, various approaches have been attempted for the dispersion of NPs in polymers, including solution dispersion, mechanical blending, and in situ polymerization with NPs reported by Guo et al. [28], each method has its own advantages and disadvantages reported by Ray et al. [29]. Polyolefins are synthesized via addition polymerization and thus have a relatively high degree of polymerization, which results in high molten viscosity [30]. Moreover, they are hard to dissolve in a solution without high temperature and long durations due to the saturated chemical structures, thus leading to poor affiliation with most of the organic solvents. Therefore, polyolefin solutions are often highly dilute in the published literatures. Blackadder and Schleinitz dissolved low-density polyethylene (LDPE) in n-dodecane, p-xylene, and decalin solvents at 0.1, 0.375, 0.75, 1.00, and 1.5 wt% to obtain single crystals [31]. Kong et al. reported the use of 0.7 wt% of polyethylene (PE) solution to determine the routes of solution fractionation [32]. Wong and coauthors dissolved LDPE at 1.1–6.5 wt% to convert plastic waste from solid to liquid to transport it via feeding pipelines [33].

However, in the published literature, reports on the range of PE concentrations and experimental conditions in which pristine inorganic NPs can be well-dispersed are scarce. NP diffusion in a polymer solution is largely dependent on the viscosity of the solution which is also dependent on the polymer concentration and temperature, in addition to the dissolution time of the polymer solution. Thus, a systematic study was conducted to determine the optimal casting temperature, LDPE concentration, and dissolution time for uniform dispersion of inorganic NPs in LDPE using the solution-casting method. This ZnO NP/LDPE composite film exhibits spectrum selective properties for shielding UV and diminishing transmittance of visible light and thus could be potentially used as a passive cooling material for the purpose of energy conservation. Therefore, the transmissivities of the films with different NP concentrations were also evaluated.

2 Experimental

2.1 Preparation and characterization of samples

LDPE pellets (AS: 9002-88-4) with a melting index of 25 g/10 min were purchased from Aldrich Chemistry. ZnO NPs with an average diameter of 90 nm were provided by Rhawn Company in Shanghai, China. In the sample preparation, first, the ZnO NPs were dissolved in 12 g of xylene [34] (Achilias et al.) by sonication for 12 min at a frequency of 22 kHz in an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Scientz-IID) with a 6-mm-diameter probe in a glass column at an ambient temperature. Then, the LDPE pellets were added into the solution in the glass column using a magnetic stirrer and heated in oil bath. Once the solution was homogenized after stirring for sufficient time at a high temperature, it was casted to form a primary film. Finally, the thickness of the casted film was adjusted by hot pressing and cooling down. The conditions for film fabrication are presented in Table 1.

Conditions for film formation experiments

| Group | Temperature of casting (°C) | Concentration of LDPE:xylene (%) | Duration of dissolution (h) | Temperature of oil bath (°C) | Concentration of ZnO:LDPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 96 | 105 | 4 |

| 50 | |||||

| 75 | |||||

| 105 | |||||

| 115 | |||||

| 115 (in vacuum) | |||||

| 2 | 115 (in vacuum) | 2.4 | 156 | 105 | 4 |

| 3.8 | |||||

| 6.1 | |||||

| 7.0 | |||||

| 8.1 | |||||

| 9 | |||||

| 3 | 115 (in vacuum) | 3.2 | 90 | 105 | 4 |

| 120 | |||||

| 188 | |||||

| 202 | |||||

| 322 |

From the above experiments, we were able to select a set of optimal conditions, i.e., 3.2% LDPE–xylene solution, 105°C dissolution temperature and 322 h dissolution time, and 115°C in vacuum oven for the formation of casted films with reasonably good particle dispersion. Using these conditions, we selected three NP concentrations, namely, 4, 5, and 6% ZnO NPs considering the flexural strength reported by Wu et al. [35], to optimize the transmissivity of the flexible films with balanced performance of UV-shielding and transparency for visible light.

The surfaces of the films were examined using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM: Zeiss MERLIN, Oberkochen, Germany). The transmittance tests for the cooling films were conducted using an UV-visible-near-infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectrophotometer (Yokogawa Model AQ6375B). Films were tensile-tested at 25°C and 60% relative humidity using a universal testing machine (Model Instron Microtester 5948) at a gage length of 10 mm and specimen width of 2 mm at a strain rate of 0.10/min with a load cell of 100 N capacity. Thermal properties of the films were determined using deferential scanning calorimetry (DSC) in nitrogen on a machine Model CCTA DSC25. The specimens were equilibrated at −80°C for 2 min and then heated at 10°C/min to 300°C at which they were isothermal for 2 min, and then cooled down at 10°C/min to −80.00°C.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Principles for material selection

PE is a semicrystalline polymer with long molecular chains [30]. Selecting the proper solute is critical for the dissolution of PE. According to the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation [36]:

where

For semicrystalline polymers, dissolution is an endothermic process [36]. In addition, the enthalpy of the LDPE solution can be calculated using the Hildebrand solubility principle equation [39]:

where

For the different concentrations of the LDPE solution in 12 g of xylene, the enthalpies are all positive, as presented in Table 2, which were calculated using equation (2). According to the Gibbs–Helmholtz equation, the bigger the enthalpy of the solution, the more difficult the dissolution of the polymer in xylene. That means that a higher temperature or additional entropy should be provided to the solution system, which would make the changes in Gibbs free energy close to zero or a negative value [36]. Therefore, the solution needs to be heated to a temperature close to the melting point of the polymer to dissolve its crystalline region. The boiling point of xylene is 144.3°C [34], and the dissolution was performed in an oil bath at 105°C ± 3°C. Moreover, the solution should be kept at the temperature, namely 105°C, for a long time with a magnetic stirrer at the bottom of the beaker to provide additional entropy to the solution system according to Mackay and coworker’s points [26].

The enthalpy of the different concentrations of the LDPE solvent

| Items | Solution (LDPE in xylene) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE (wt%) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| ΔH m (cal) | 0.78 | 1.47 | 2.27 | 3.01 | 3.75 | 4.50 |

3.2 Effect of casting temperature

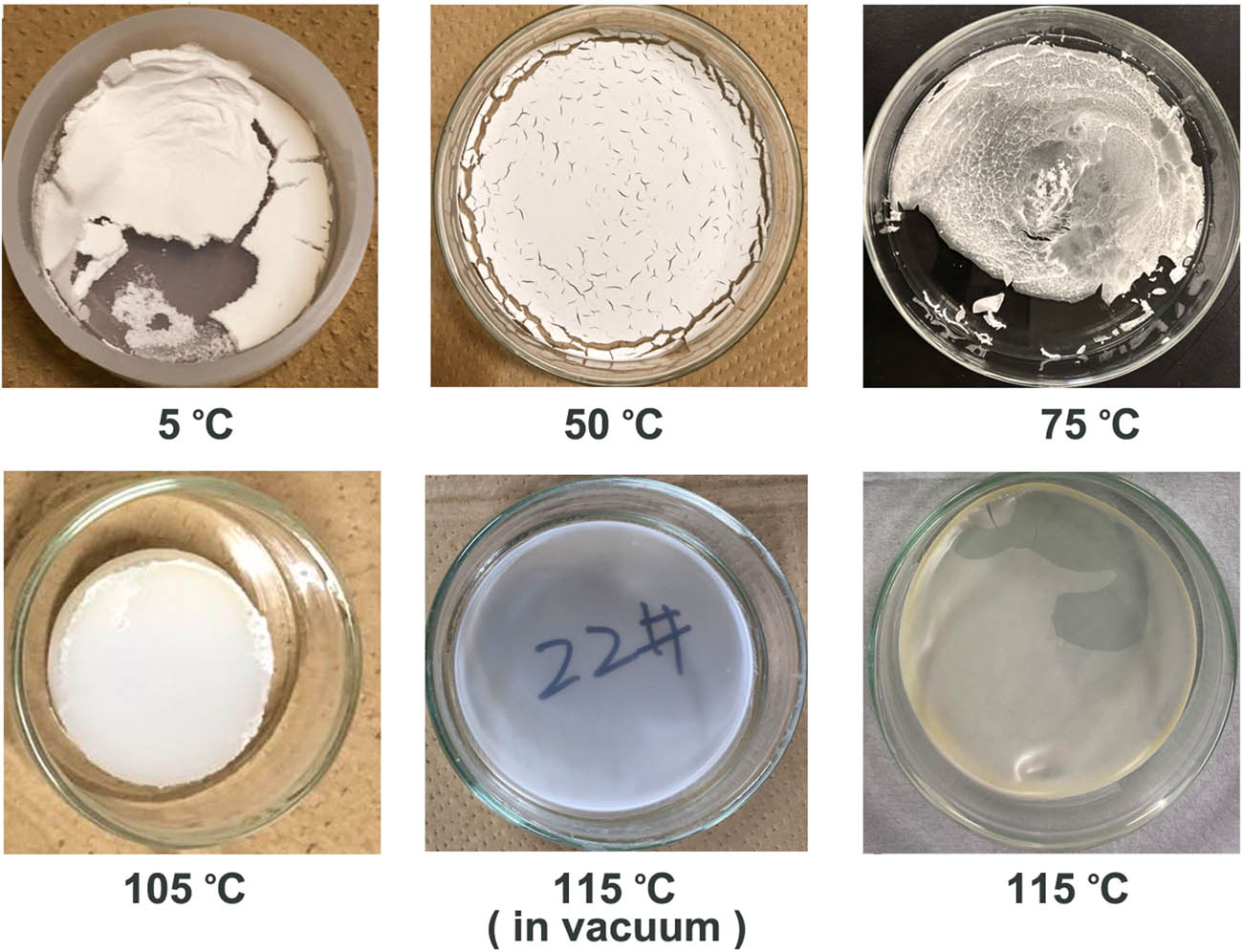

Figure 1 presents the films formed at different casting or volatilization temperatures ranging from 5°C to 115°C. At 5°C, the casted film looked like fine powder (Figure 1), and at 50°C, it appeared as a white opaque pancake-like film with cracks on the surface. At 75°C, the film looked like a combination of white powder, white pancake, and semitransparent film. At 105°C, a white opaque uniform film was formed. The films presented in Figure 1e and f were formed in vacuum oven and ordinary oven, respectively, at 115°C. Both were relatively transparent and uniform, although the film formed in air in a regular oven appeared slightly yellowish possibly due to oxidation.

Casted ZnO NP (4%)/LDPE films formed at different casting temperatures.

The morphologies of the films formed at different temperatures revealed the states of the molecules in the solution during the volatilization of the solvent. As discussed in the previous section, mixing the polymer with the solvent is a spontaneous process when ΔG m < 0. This could only occur when the temperature was sufficiently high, according to equation (1) [36]. When the solution temperature was low, the polymer molecules tended to exhibit phase separation with the solvent and thus formed clusters of polymer molecules in the solution, which then became polymer particles after the evaporation of the solvent. As the temperature increased, the molecules had higher affiliation with the solvent and thus were less and less likely to exhibit phase separation in the solution. Even if some degree of phase separation still existed, the molecules on the boundaries between the neighboring domains of polymers were likely entangled. Thus, the polymer particles formed at higher temperatures, for example, 50–75°C, were stuck together, forming a powdery cake. These films could develop cracks due to the differential shrinkage of the different parts of the film caused by the uneven distribution of the polymer phases. As the casting temperature increased, exceeding the θ temperature, the polymer molecules in the solution exhibited good solubility and thus did not demonstrate phase separation during the evaporation of the solvent [36]. This made the casted film transparent and free of cracks.

3.3 The solubility of LDPE in different concentrations

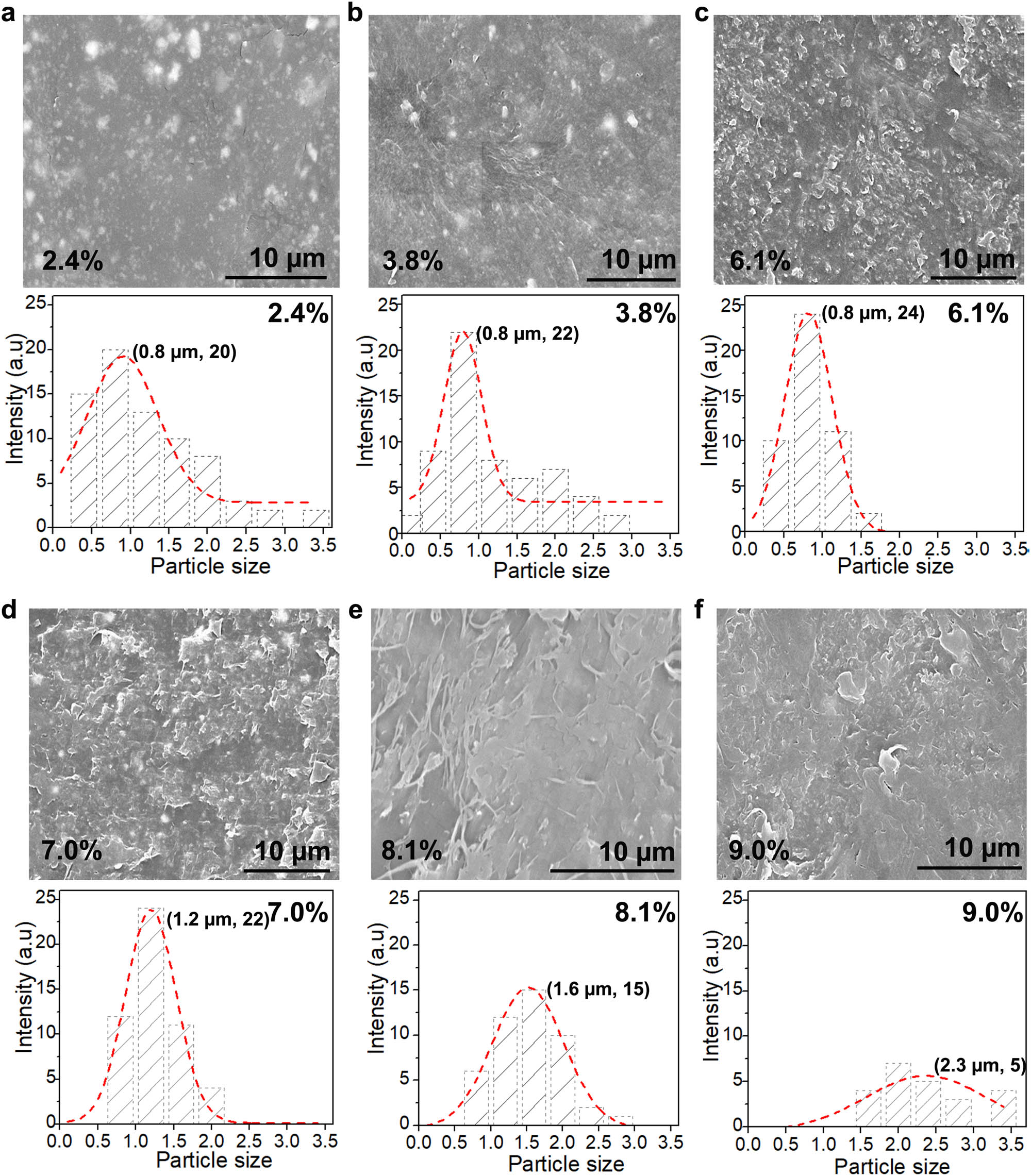

To determine the proper is concentration for the dissolution of LDPE with reasonably good dispersion of the NPs, a systematic experiment was conducted at LDPE concentrations of 2.4, 3.8, 6.1, 7.0, 8.1, and 9.0 wt%. Such concentrations are close to those presented in Table 2. The surface morphology and particle cluster sizes of the films are presented in Figure 2. The film surfaces became rougher as the LDPE concentration increased. More importantly, the peak size of the NP cluster also increased from 0.8 to 2.3 µm as the LDPE concentration increased from 6.1 to 9.0%. Below 6.1%, the peak cluster size of 0.8 µm was maintained, regardless of the concentration reduction, which similar to what is reported by Ali et al. [40]. Obviously, when the LDPE concentration increases, the enthalpy ΔH m of the polymer solution will be increased as shown in Table 2 (ΔH m increases almost five times for polymer concentration increasing from 2 to 10 wt%), which means a higher temperature and longer time will be required for the same degree of solubility of LDPE in the solution according to equation (1). This would hinder the dissolution of the polymer, increase the solution viscosity, and inhibit the dispersion of the NPs [41]. It is noteworthy that the films were prepared with a dissolution time of 156 h at 105°C, which may not be sufficiently long for the complete dispersion of individual NPs, as discussed in the subsequent section. In our later experiments, we greatly prolonged the dissolution time and were able to achieve satisfactory dispersion of NPs with peak diameter similar to that of the individual NPs. Evidently, this result implies that a concentration below 6% is preferred for a good initial dispersion of the NPs. In the following experiment, we selected 3.2% of LDPE and prolonged the dissolution time for further dispersion of the NPs.

The surface morphology and ZnO NP (4%) size distributions of the films dissolved in the different mass fractions of LDPE. (a) 2.4 wt%, (b) 3.8 wt%, (c) 6.10 wt%, (d) 7.0 wt%, (e) 8.1 wt%, and (f) 9.0 wt% of LDPE in xylene.

3.4 Effects of duration on the solubility of LDPE and dispersion of NPs

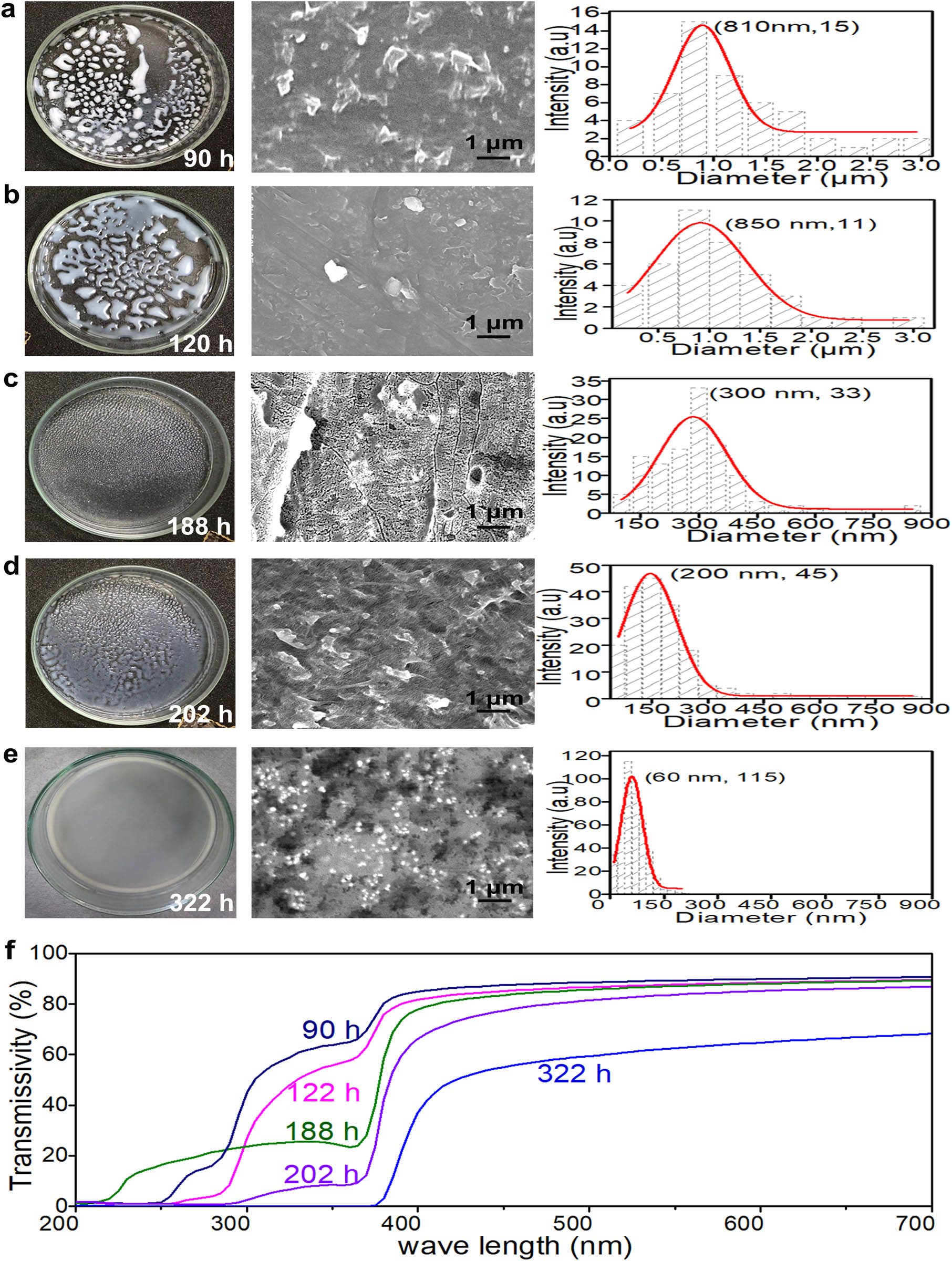

In the process of mixing polymer and NPs, it is necessary to completely dissolve the polymer in the solution. Thus, the polymer solution has to be stirred long enough at a sufficient temperature to increase the entropy, according to equation (1). To determine the proper dissolution time, a solution with 4 wt% of ZnO/LDPE and 3.2% of LDPE/xylene was prepared in 105°C oil bath and stirred for different hours to produce the casted films (see Group 3 in Table 2). The left column of Figures 3a–e presents the states of the casted films after dissolution for 90, 120, 188, 202, and 322 h, respectively. The casted film dissolved for 90 h has large, isolated blocks (Figure 3a). As the duration increased, the areas of the isolated blocks become flatter and larger first (120 h) and then gradually formed larger number of smaller blocks (188 h), which started to merge into larger and more continuous pieces (202 h) until finally forming a whole smooth piece (322 h). The middle and right columns of Figure 3 present the SEM images and size distributions, respectively, of NPs in the hot-pressed films corresponding to the casted films for various dissolution hours. In the SEM images, the NP clusters were identified, and their sizes and numbers were measured. The particle agglomerate sizes became smaller and smaller as the dissolution time was prolonged until the peak particle or cluster sizes (60 nm for the 322 h group) reached that close to the individual particle size (90 nm), as presented in the right column of Figure 3.

Effect of dissolution time on ZnO NP dispersion in LDPE; (a–e) the left column presents the ZnO/LDPE casted films, the middle column presents the SEM images of the hot-pressed ZnO/LDPE films, and the right column presents the corresponding particle size distributions; (f) the transmissivity curves of the ZnO/LDPE films after the different dissolution times.

Another way of determining the degree of NP dispersion in LDPE is the measurement of the transmissivity of the film to thermal radiation. In principle, the transmissivity of incident light can be reduced by either Rayleigh scattering or Mie scattering which is dependent on the particle sizes [42]. Rayleigh scattering occurs due to the existence of particles with a size parameter X < 1, calculated as follows [43]:

where r denotes the spherical particle radius, and λ denotes the wavelength of incident light. According to this principle, particles with diameters of 90–120 nm are suitable for the preparation of a transparent passive cooling film with Rayleigh scattering. In this study, the NPs utilized had an average diameter of 90 nm, which could have strong Rayleigh scattering, thus ensuring good shielding against radiation in the UV region (10–400 nm) if dispersed well. Figure 3f presents the transmissivities of the films. For the films formed with 90 and 122 h dissolution times, the transmissivities for thermal radiation were high in the whole wavelength range. For the films formed with 188 h dissolution time, the transmissivity of radiation below 400 nm wavelength was substantially reduced, whereas that for the films with 202 h dissolution time was further suppressed significantly. For the films with 322 h dissolution time, the thermal radiation in the UV range was almost completely blocked. This result corresponds well to the particle size reduction pattern. In summary, as the dissolution time increased, the bonding force between NPs in an agglomerate could be diminished by continuously increased entropy provided by the solution system, resulting in reduced agglomerate sizes, which is reported in article by Jancar et al. [44]. Consequently, the film became more effective in shielding the light, especially in the UV region. This indicates that the film with good NP dispersion could have good spectrum selective properties and thus promising passive cooling performance as passive cooling materials.

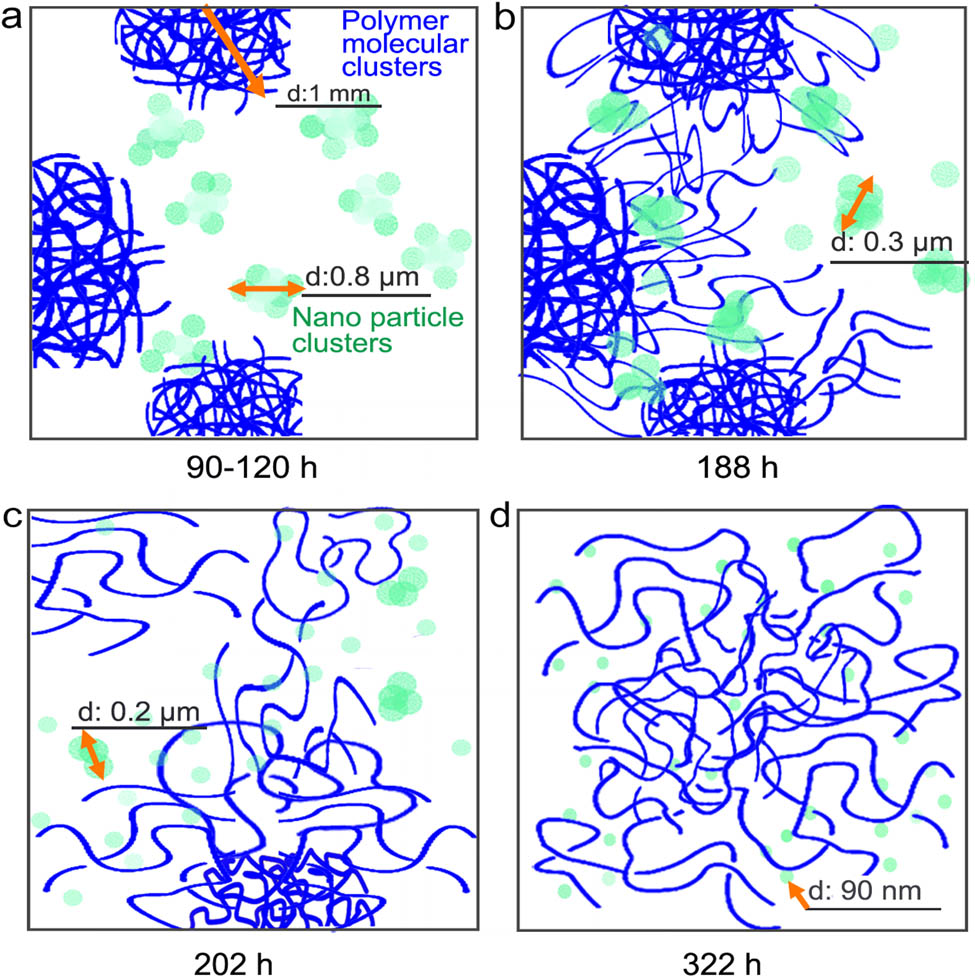

The mechanism for the effect of dissolution time on NP dispersion may be explained using Figure 4. Polymer dissolution and NP dispersion are the two partially overlapping but somewhat consecutive processes in casting a homogeneous ZnO NP-doped LDPE film. The former must occur first for the latter to proceed. In the beginning of the dissolution, the polymer molecules formed clusters of about 1 mm diameter (according to our visual observation), which originated from the pellets of solid polymer before dissolution. And, the NPs agglomerated into clusters of about 0.8 µm diameter, which contain hundreds of NPs (Figure 4a) due to initial mechanical blending and mixing. The polymer clusters were from the melting and dissolution of the semicrystalline polymer pieces. In such a relatively highly concentrated polymer solution, polymeric molecular entanglement is inevitable. These entangled chains can be gradually stretched at a high temperature in a proper solvent. Moreover, polymer molecular chains can diffuse toward low-concentration regions or boundaries between the polymer clusters, although this process could be very slow due to the high viscosity of the solution. In the current study, the films casted after the dissolution time of 202 h or longer could form a relatively complete film. This indicates that LDPE chains in the neighboring clusters reached out or diffused out to bridge or bond the clusters together to form a more homogeneous film. In addition, the diffusion of polymer molecular chains toward the boundaries could effectively create larger intermolecular distance between the polymer molecules near the NP agglomerates and thus accelerate the diffusion of the NPs into the polymeric gel. Only after that could the ideal dispersion of the NPs be fulfilled. In this study, the ideal NP dispersion was achieved in 322 h. Vigneshwaran et al. dispersed surface-treated 40 nm ZnO NPs in HDPE and shielded about 65% of UV because the NPs agglomerated into about 1 µm clusters [45]. Xiong et al. reported that total UV-shielding could be achieved with NP concentration higher than 7 wt% in a ZnO/poly(styrene butylacrylate) latex composite film [46], while 4 wt% was sufficient for complete shielding of UV in the current study. Obviously, the performance of our ZnO/LDPE composite films is better than those reported in literature.

The mechanism of uniformly mixing LDPE and NPs governed by time, temperature, and concentration of LDPE and NPs.

As the polymer cluster started to dissolve at 188 h, the NPs began to diffuse into the polymer, and the agglomerates started to diminish [44]. The dispersion of the agglomerated NPs in the polymer solution is determined by two factors, namely, the van der Waals forces holding the NPs together and the Brownian motion for the diffusion of the NPs to move toward the direction of lower particle concentration [47]. The diffusion coefficient, D, for spherical NPs can be calculated using the Stokes–Einstein equation [48]:

where k denotes the Boltzmann constant; T, the temperature in Kelvin; μ, the viscosity of the polymer solution; and d, the particle diameter. As the NPs in the agglomerated clusters diffuse toward the polymer matrix due to the Brownian motion, the diffusion rate relates positively to the temperature and negatively to the polymer solution viscosity and the particle diameter. Cui et al. also interpreted the dispersion of NPs in the liquid–liquid interface, like a transition from diffusive to confined dynamics was manifested by intermittent dynamics [49]. In the current study, we have quite small NPs (90 nm) and quite high concentration of LDPE (3.2%), which results in slow NP diffusion. Consequently, good dispersion was only achieved after quite a long dissolution time (322 h) at an elevated temperature.

Of course, the dissolution time in the current study is not necessarily optimal because some other factors such as dissolution temperature and LDPE concentration could greatly influence the process. According to equation (1), when temperature increases, ΔG will be decreased and thus stretching out of polymer chains would be more preferable leading to a shorter optimal dissolution time in addition to the increased diffusion coefficient discussed above. Lowering the LDPE concentration could also facilitate diffusion process for both the polymer and the NPs since it could greatly reduce the viscosity of the solution, leading to a reduced dissolution time.

3.5 Optimizing the transmissivity of spectrum selective film

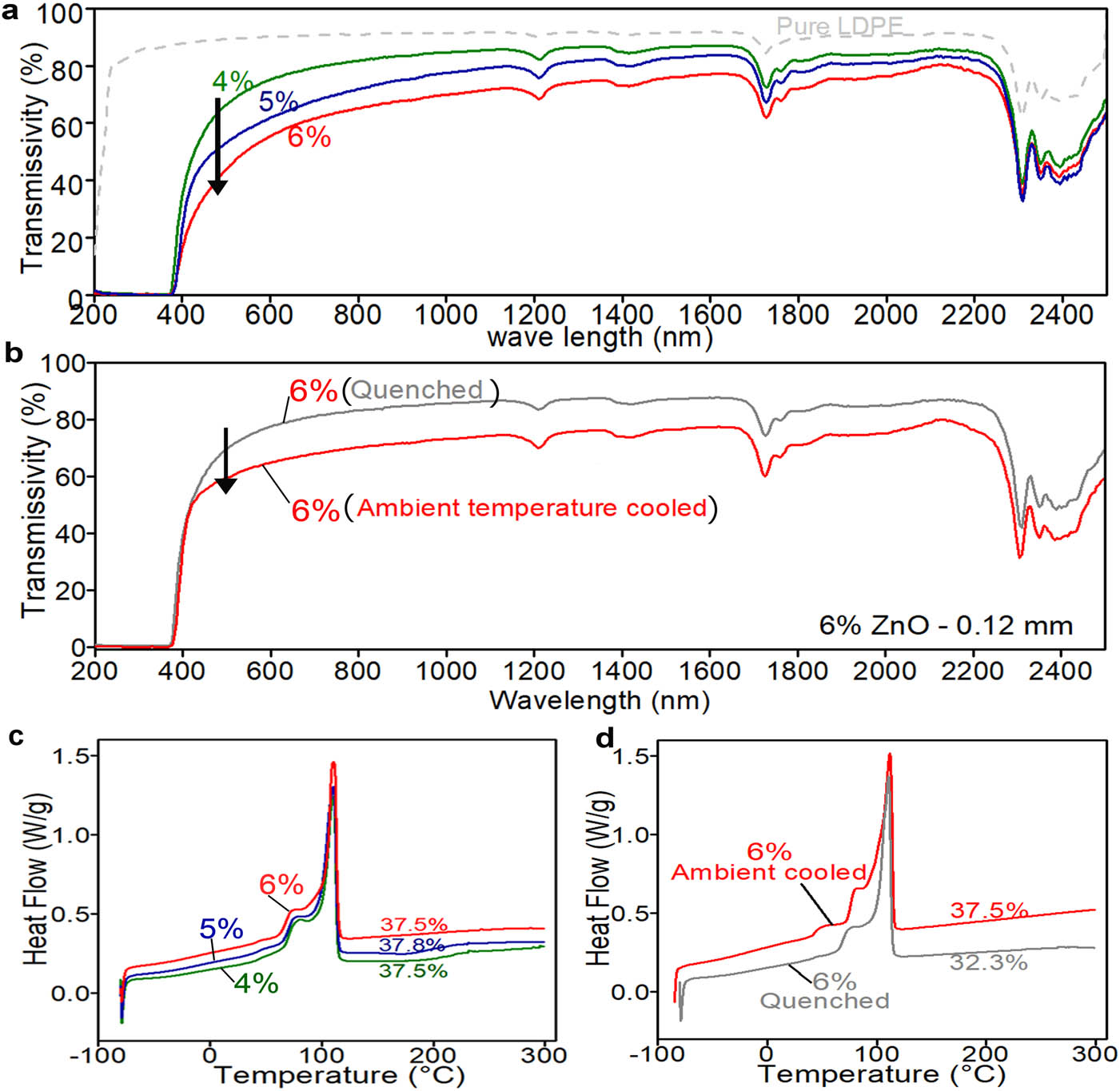

The transmittance of UV photons through an NP-doped membrane is mainly affected by the NP concentration and film crystallinity. Films doped with 4, 5 and 6% ZnO NPs were tested to determine the effect of particle concentration on the transmissivity of the films.

The transmissivity of the UV-shielding films with a thickness of 0.12 ± 0.05 mm could shield total UV lights, which is a better performance at a relative lower NP concentration, and the transmissivity decreased as the NP concentration increased in the visible light region (Figure 5a). However, the difference tended to diminish with the increase in wavelength as the light scattering effect changed with the size parameter X of the NPs, which is inversely proportional to the wavelength according to equation (3).

The factors affecting the transmissivity of passive cooling film. (a) Effect of the nanoparticle concentration, (b) effect of the curing process, (c) the DSC curves of films with different particle concentrations, and (d) the DSC curves of the quenched and ambient temperature-cooled samples.

The transmissivity of the films is also closely related to the crystallinity of the film [50], which is determined by the cooling condition after hot pressing the casted film. A higher NP concentration did not result in a higher crystallinity (37.5, 37.8, 37.5% for 4, 5, 6% NPs shown in Figure 5c). Figure 5b presents the transmissivity of the hot-pressed ZnO nanofilms which were quenched or cooled at an ambient temperature right after hot pressing. The transmissivities of the two films are different in the visible light region and almost the same in the UV region. The DSC curves revealed that the crystallinity of the quenched film (32.3%) was substantially lower than that (37.5%) cooled at an ambient temperature (Figure 5d). Jordan with coworkers described the crystallinity in different processing influenced by temperature [51]. In general, a quenched film is likely to have smaller crystals and lower crystallinity due to a much shorter time for the crystals to grow, thus leading to high transmissivity compared with an ambient temperature-cooled film.

3.6 Mechanical performance of films

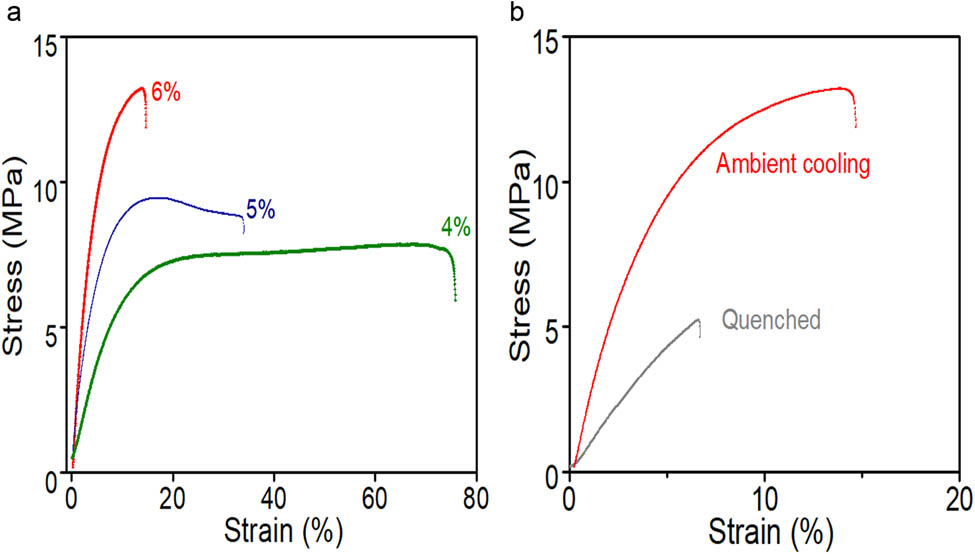

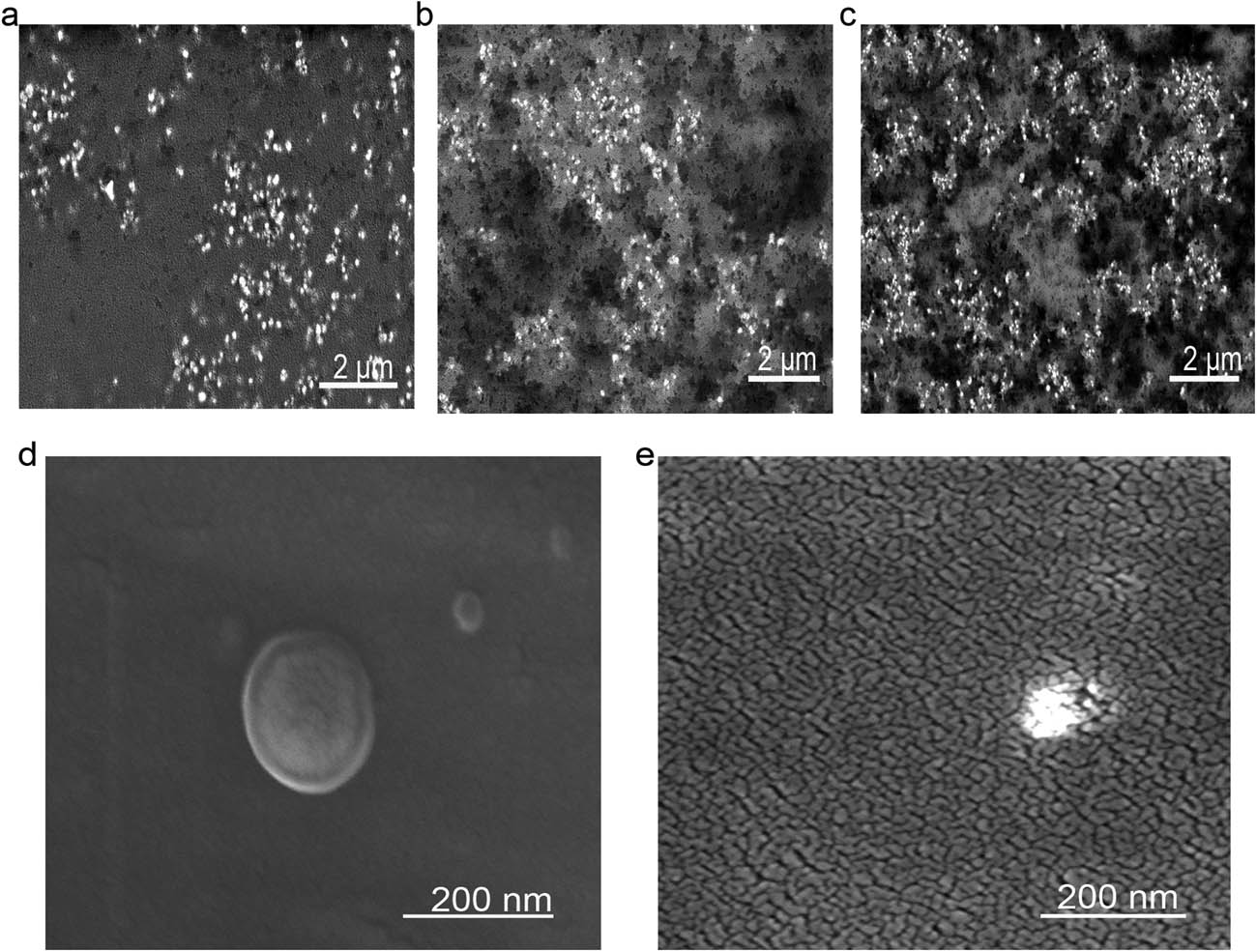

The mechanical property of the films is presented in Figure 6 and Table 3. The failure strains of the NP-doped films decreased from 80 to 15% with an increase in the NP concentration from 4 to 6 wt%, respectively. Conversely, the tensile strength increased with the increase in the NP concentration as reported by Wang et al. [52]. It seems that the mechanical properties of the films changed from being typical ductile materials to relatively brittle materials due to failure mechanism change from localized plastic deformation to more defects-dominant failure. This could be observed in SEM images (see Figure 7) of the films which show as the NP concentration increased, the distance between neighboring NPs decreased drastically and thus could possibly increase probability of containing weak spots in the specimen. On the other hand, the tensile strength and failure strain of the film were much lower for the quenched film compared with the film cooled at an ambient temperature due to creases or nano-cracks generated by quenching on the surface of the quenched film as shown in Figure 7.

The stress–strain curves; (a) films doped with different concentrations of ZnO NPs; (b) films which were post hot-pressed by quenching or ambient temperature cooling.

Mechanical properties of passive cooling films

| Samples | Tensile stress (MP) | Young’s modulus (MP) | Failure strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4% ZnO films | 7.6 | 5.4 | 79.3 |

| 5% ZnO films | 9.7 | 2.3 | 29.6 |

| 6% ZnO films | 10.8 | 3.9 | 7.3 |

| 6% ZnO films (quenched) | 5.1 | 1.5 | 6.9 |

SEM images of the ZnO-LDPE films. (a) 4% ZnO NP; (b) 5% ZnO NP; (c) 6% ZnO NP; (d) the high magnification of 6% ZnO NP film cooled with ambient temperature of post hot press; (e) 6% ZnO NP film quenched of post hot press.

4 Conclusions

To make a spectrum-selective or UV-shielding ZnO NP-doped film with uniform dispersion of the NPs and ideal transmissivity for spectrum tailoring, a systematic study was conducted to determine the critical parameters for film fabrication (e.g., casting temperature, polymer concentration, and dissolution time). It was found that the casting temperature has to be maintained at 115°C or above in vacuum to ensure the formation of a transparent and uniform film without oxidation. For proper initial dispersion of the NPs in the polymer solution, the LDPE concentration should be lower than 6%. For a uniform and complete dispersion of individual NPs, the dissolution time has to be sufficiently long for the polymer molecules to unentangle first, which could allow the diffusion of the NPs into the polymer gel, thus resulting in a homogeneous NP dispersion. Only when the NPs are well-dispersed will the film have ideal shielding against UV light, while allowing a reasonable amount of visible light to be transmitted. The transmissivity of the films can be optimized by changing the concentration of doped NP and the crystallinity of the film through quenching. The mechanical properties of the UV-shielding films were altered from ductile to relatively brittle by varying the NP concentrations.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Education Department Research Program of Fujian Province (CN) [No. JA14265 and JT1808378], Minjiang Chair Professor Program of Fujian Province (CN) [No. 2018(56)], Science & Technology Program of Quanzhou City (CN) [No. 2016Z071 and No. 2017ZT001], and Japan Government Funding [JSPS KAKENHI No. 20H00288 and 26420721]. We would like to thank Profs. Shuiyuan Luo, Xiangyang Liu, and Tingdi Liao, Dr Hairong Chen, Ms Xiaoyu Han, Jia Song, and Jingjing Gao for their help in preparing the material and carrying out the experiment.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

[1] Balazs AC, Emrick T, Russell TP. Nanoparticle polymer composites: where two small worlds meet. Science. 2006;314:1107–10.10.1126/science.1130557Search in Google Scholar

[2] Oksman K, Aitomäki Y, Mathew AP, Siqueira G, Zhou Q, Butylina S, et al. Review of the recent developments in cellulose nanocomposite processing. Composites Part A. 2016;83:2–18.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.10.041Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lau K-T, Hui D. The revolutionary creation of new advanced materials – carbon nanotube composites. Composites Part B. 2002;33:263–77.10.1016/S1359-8368(02)00012-4Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhang D, Yang Z, Wu Z, Dong G. Metal–organic frameworks-derived hollow zinc oxide/cobalt oxide nanoheterostructure for highly sensitive acetone sensing. Sens Actuators B. 2019;283:42–51.10.1016/j.snb.2018.11.133Search in Google Scholar

[5] Zhang D, Sun Y, Jiang C, Yao Y, Wang D, Zhang Y. Room-temperature highly sensitive CO gas sensor based on Ag-loaded zinc oxide/molybdenum disulfide ternary nanocomposite and its sensing properties. Sens Actuators B. 2017;253:1120–8.10.1016/j.snb.2017.07.173Search in Google Scholar

[6] Jiang J, Pi J, Cai J. The advancing of zinc oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2018;2018:1062562.10.1155/2018/1062562Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Li K, Jin S, Li J, Chen H. Improvement in antibacterial and functional properties of mussel-inspired cellulose nanofibrils/gelatin nanocomposites incorporated with graphene oxide for active packaging. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;132:197–212.10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.02.011Search in Google Scholar

[8] Li F, Yu H-Y, Wang Y-Y, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Yao J-M, et al. Natural biodegradable poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) nanocomposites with multifunctional cellulose nanocrystals/graphene oxide hybrids for high-performance food packaging. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67(39):10954–67.10.1021/acs.jafc.9b03110Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Lienhard V JH, Lienhard JH. A heattransfer textbook, 4th edn. Cambridge, MA: Phlogiston Press; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Yoo J, Kim H, Chang H, Park W, Hahn SK, Kwon W. Biocompatible organosilica nanoparticles with self-encapsulated phenyl motifs for effective UV protection. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(8):9062–9.10.1021/acsami.9b21990Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Xie W, Pakdel E, Liu D, Sun L, Wang X. Waste-hair-derived natural melanin/TiO2 hybrids as highly efficient and stable UV-shielding fillers for polyurethane films. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2019;8(3):1343–52.10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b03514Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hacker E, Horsham C, Vagenas D, Jones L, Lowe J, Janda MA. Mobile technology intervention with ultraviolet radiation dosimeters and smartphone apps for skin cancer prevention in young adults: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(11):1–13.10.2196/mhealth.9854Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Li S, Peng J, Tan Y, Ma T, Li X, Hao B. Study of the application potential of photovoltaic direct-driven air conditioners in different climate zones. Energy Build. 2020;226:110387–400.10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110387Search in Google Scholar

[14] Liu Q, Toudert J, Liu F, Mantilla-Perez P, Bajo MM, Russell TP, et al. Circumventing UV light induced nanomorphology disorder to achieve long lifetime PTB7-Th:PCBM based solar cells. Adv Energy Mater. 2017;7(21):1701201–28.10.1002/aenm.201701201Search in Google Scholar

[15] Feng Y, Zhang J, He J, Zhang J. Transparent cellulose/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanocomposites with enhanced UV-shielding properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;147:171–7.10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Li J, Zhang X, Zhang J, Mi Q, Jia F, Wu J, et al. Direct and complete utilization of agricultural straw to fabricate all-biomass films with high-strength, high-haze and UV-shielding properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;223:115057–64.10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Han C, Wang F, Gao C, Liu P, Ding Y, Zhang S, et al. Transparent epoxy-ZnO/CdS nanocomposites with tunable UV and blue light-shielding capabilities. J Mater Chem C. 2015;3(19):5065–72.10.1039/C4TC02880ESearch in Google Scholar

[18] Wang W, Zhang B, Jiang S, Bai H, Zhang S. Use of CeO(2) nanoparticles to enhance UV-shielding of transparent regenerated cellulose films. Polymers. 2019;11(3):458–71.10.3390/polym11030458Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Li T, Zhai Y, He S, Gan W, Wei Z, Heidarinejad M, et al. A radiative cooling structural material. Science. 2019;364(6442):760–3.10.1126/science.aau9101Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Gamage S, Kang ESH, Åkerlind C, Sardar S, Edberg J, Kariis H, et al. Transparent nanocellulose metamaterial enables controlled optical diffusion and radiative cooling. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8(34):11687–94.10.1039/D0TC01226BSearch in Google Scholar

[21] Kango S, Kalia S, Celli A, Njuguna J, Habibi Y, Kumar R. Surface modification of inorganic nanoparticles for development of organic–inorganic nanocomposites – a review. Progr Polym Sci. 2013;38(8):1232–61.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.02.003Search in Google Scholar

[22] Jiang C-C, Cao Y-K, Xiao G-Y, Zhu R-F, Lu Y-P. A review on the application of inorganic nanoparticles in chemical surface coatings on metallic substrates. RSC Adv. 2017;7(13):7531–9.10.1039/C6RA25841GSearch in Google Scholar

[23] El-Naggar ME, Hassabo AG, Mohamed AL, Shaheen TI. Surface modification of SiO2 coated ZnO nanoparticles for multifunctional cotton fabrics. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;498:413–22.10.1016/j.jcis.2017.03.080Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hong R, Pan T, Qian J, Li H. Synthesis and surface modification of ZnO nanoparticles. Chem Eng J. 2006;119(2–3):71–81.10.1016/j.cej.2006.03.003Search in Google Scholar

[25] Moonart U, Utara S. Effect of surface treatments and filler loading on the properties of hemp fiber/natural rubber composites. Cellulose. 2019;26(12):7271–95.10.1007/s10570-019-02611-wSearch in Google Scholar

[26] Mackay ME, Tuteja A, Duxbury PM, Hawker CJ, Van Horn B, Guan Z, et al. General strategies for nanoparticle dispersion. Science. 2006;311(5768):1740–3.10.1126/science.1122225Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zarrinkhameh M, Zendehnam A, Hosseini SM. Fabrication of polyvinylchloride based nanocomposite thin film filled with zinc oxide nanoparticles: morphological, thermal and optical characteristics. J Ind Eng Chem. 2015;30:295–301.10.1016/j.jiec.2015.05.036Search in Google Scholar

[28] Guo S, Fu D, Utupova A, Sun D, Zhou M, Jin Z, et al. Applications of polymer-based nanoparticles in vaccine field. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):143–55.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0014Search in Google Scholar

[29] Ray SS, Okamoto M. Polymer/layered silicate nanocomposites: a review from preparation to processing. Progr Polym Sci. 2003;28(11):1539–641.10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2003.08.002Search in Google Scholar

[30] Hiemenz PC, Lodge TP. Polymer chemistry. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2007.10.1201/9781420018271Search in Google Scholar

[31] Blackadder D, Schleinitz H. The dissolution and recrystallization of polyethylene crystals suspended in various solvents. Polymer. 1966;7(12):603–37.10.1016/0032-3861(66)90017-6Search in Google Scholar

[32] Kong J, Fan X, Jia M. Study of polyethylene solution fractionation and resulting fractional crystallization behavior. J Appl Polym Sci. 2004;93(6):2542–9.10.1002/app.20767Search in Google Scholar

[33] Wong SL, Ngadi N, Abdullah TAT. Study on dissolution of low density polyethylene (LDPE). Appl Mech Mater. 2014;695:170–3.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.695.170Search in Google Scholar

[34] Achilias DS, Roupakias C, Megalokonomos P, Lappas AA, Antonakou EV. Chemical recycling of plastic wastes made from polyethylene (LDPE and HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). J Hazard Mater. 2007;149(3):536–42.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.06.076Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Wu Y, Tang B, Liu K, Zeng X, Lu J, Zhang T, et al. Enhanced flexural properties of aramid fiber/epoxy composites by graphene oxide. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):484–92.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0043Search in Google Scholar

[36] Koltzenburg S, Maskos M, Nuyken O. Polymer chemistry. New York: Springer; 2017.10.1007/978-3-662-49279-6Search in Google Scholar

[37] Shenoy SL, Bates WD, Frisch HL, Wnek GE. Role of chain entanglements on fiber formation during electrospinning of polymer solutions: good solvent, non-specific polymer–polymer interaction limit. Polymer. 2005;46(10):3372–84.10.1016/j.polymer.2005.03.011Search in Google Scholar

[38] Choi J, Hore MJA, Clarke N, Winey KI, Composto RJ. Nanoparticle brush architecture controls polymer diffusion in nanocomposites. Macromolecules. 2014;47(7):2404–10.10.1021/ma500235vSearch in Google Scholar

[39] Belmares M, Blanco M, Goddard 3rd WA, Ross RB, Caldwell G, Chou SH, et al. Hildebrand and Hansen solubility parameters from molecular dynamics with applications to electronic nose polymer sensors. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(15):1814–26.10.1002/jcc.20098Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Ali A, Hwang EY, Choo J, Lim DW. Nanoscale graphene oxide-induced metallic nanoparticle clustering for surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based IgG detection. Sens Actuators B. 2018;255:183–92.10.1016/j.snb.2017.07.140Search in Google Scholar

[41] Mu L, He J, Li Y, Ji T, Mehra N, Shi Y, et al. Molecular origin of efficient phonon transfer in modulated polymer blends: effect of hydrogen bonding on polymer coil size and assembled microstructure. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121(26):14204–12.10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b03726Search in Google Scholar

[42] Choudhury NR, Vilaplana R, Botet R, Sen AK. Comparison of light scattering properties of porous dust particle with connected and unconnected dipoles. Planet and Space Sci. 2020;190:104974.10.1016/j.pss.2020.104974Search in Google Scholar

[43] Hsieh AH, Corti DS, Franses EI. Rayleigh and Rayleigh-Debye-Gans light scattering intensities and spetroturbidimetry of dispersions of unilamellar vesicles and multilamellar liposomes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;578:471–83.10.1016/j.jcis.2020.05.085Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Jancar J, Ondreas F, Lepcio P, Zboncak M, Zarybnicka K. Mechanical properties of glassy polymers with controlled NP spatial organization. Polym Test. 2020;90:106640–9.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106640Search in Google Scholar

[45] Vigneshwaran N, Bharimalla AK, Prasad V, Kathe AA, Balasubramanya RH. Functional behaviour of polyethylene-ZnO nanocomposites. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8(8):4121–6.10.1166/jnn.2008.AN48Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Xiong M, Gu G, You B, Wu L. Preparation and characterization of poly(styrene butylacrylate) latex/nano-ZnO nanocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2003;90:1923–31.10.1002/app.12869Search in Google Scholar

[47] Mansel BW, Chen C-Y, Lin J-M, Huang Y-S, Lin Y-C, Chen H-L. Hierarchical structure and dynamics of a polymer/nanoparticle hybrid displaying attractive polymer–particle interaction. Macromolecules. 2019;52(22):8741–50.10.1021/acs.macromol.9b01141Search in Google Scholar

[48] Shokeen N, Issa C, Mukhopadhyay A. Comparison of nanoparticle diffusion using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and differential dynamic microscopy within concentrated polymer solutions. Appl Phys Lett. 2017;111(26):263703.10.1063/1.5016062Search in Google Scholar

[49] Cui M, Miesch C, Kosif I, Nie H, Kim PY, Kim H, et al. Transition in dynamics as nanoparticles jam at the liquid/liquid interface. Nano Lett. 2017;17(11):6855–62.10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03159Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Lagarón JM, López-Rubio A, José Fabra M. Poly(l-lactide)/ZnO nanocomposites as efficient UV-shielding coatings for packaging applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2016;133(2):42426–33.10.1002/app.42426Search in Google Scholar

[51] Jordan AM, Kim K, Soetrisno D, Hannah J, Bates FS, Jaffer SA, et al. Role of crystallization on polyolefin interfaces: an improved outlook for polyolefin blends. Macromolecules. 2018;51(7):2506–16.10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00206Search in Google Scholar

[52] Wang X, Xu P, Han R, Ren J, Li L, Han N, et al. A review on the mechanical properties for thin film and block structure characterised by using nanoscratch test. Nanotechnol Rev. 2019;8(1):628–44.10.1515/ntrev-2019-0055Search in Google Scholar

© 2020 Lina Cui et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Generalized locally-exact homogenization theory for evaluation of electric conductivity and resistance of multiphase materials

- Enhancing ultra-early strength of sulphoaluminate cement-based materials by incorporating graphene oxide

- Characterization of mechanical properties of epoxy/nanohybrid composites by nanoindentation

- Graphene and CNT impact on heat transfer response of nanocomposite cylinders

- A facile and simple approach to synthesis and characterization of methacrylated graphene oxide nanostructured polyaniline nanocomposites

- Ultrasmall Fe3O4 nanoparticles induce S-phase arrest and inhibit cancer cells proliferation

- Effect of aging on properties and nanoscale precipitates of Cu-Ag-Cr alloy

- Effect of nano-strengthening on the properties and microstructure of recycled concrete

- Stabilizing effect of methylcellulose on the dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Preparation and electromagnetic properties characterization of reduced graphene oxide/strontium hexaferrite nanocomposites

- Interfacial characteristics of a carbon nanotube-polyimide nanocomposite by molecular dynamics simulation

- Preparation and properties of 3D interconnected CNTs/Cu composites

- On factors affecting surface free energy of carbon black for reinforcing rubber

- Nano-silica modified phenolic resin film: manufacturing and properties

- Experimental study on photocatalytic degradation efficiency of mixed crystal nano-TiO2 concrete

- Halloysite nanotubes in polymer science: purification, characterization, modification and applications

- Cellulose hydrogel skeleton by extrusion 3D printing of solution

- Crack closure and flexural tensile capacity with SMA fibers randomly embedded on tensile side of mortar beams

- An experimental study on one-step and two-step foaming of natural rubber/silica nanocomposites

- Utilization of red mud for producing a high strength binder by composition optimization and nano strengthening

- One-pot synthesis of nano titanium dioxide in supercritical water

- Printability of photo-sensitive nanocomposites using two-photon polymerization

- In situ synthesis of expanded graphite embedded with amorphous carbon-coated aluminum particles as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries

- Effect of nano and micro conductive materials on conductive properties of carbon fiber reinforced concrete

- Tribological performance of nano-diamond composites-dispersed lubricants on commercial cylinder liner mating with CrN piston ring

- Supramolecular ionic polymer/carbon nanotube composite hydrogels with enhanced electromechanical performance

- Genetic mechanisms of deep-water massive sandstones in continental lake basins and their significance in micro–nano reservoir storage systems: A case study of the Yanchang formation in the Ordos Basin

- Effects of nanoparticles on engineering performance of cementitious composites reinforced with PVA fibers

- Band gap manipulation of viscoelastic functionally graded phononic crystal

- Pyrolysis kinetics and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/bamboo particle biocomposites: Effect of particle size distribution

- Manipulating conductive network formation via 3D T-ZnO: A facile approach for a CNT-reinforced nanocomposite

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of WC–Ni multiphase ceramic materials with NiCl2·6H2O as a binder

- Effect of ball milling process on the photocatalytic performance of CdS/TiO2 composite

- Berberine/Ag nanoparticle embedded biomimetic calcium phosphate scaffolds for enhancing antibacterial function

- Effect of annealing heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of nonequiatomic CoCrFeNiMo medium-entropy alloys prepared by hot isostatic pressing

- Corrosion behaviour of multilayer CrN coatings deposited by hybrid HIPIMS after oxidation treatment

- Surface hydrophobicity and oleophilicity of hierarchical metal structures fabricated using ink-based selective laser melting of micro/nanoparticles

- Research on bond–slip performance between pultruded glass fiber-reinforced polymer tube and nano-CaCO3 concrete

- Antibacterial polymer nanofiber-coated and high elastin protein-expressing BMSCs incorporated polypropylene mesh for accelerating healing of female pelvic floor dysfunction

- Effects of Ag contents on the microstructure and SERS performance of self-grown Ag nanoparticles/Mo–Ag alloy films

- A highly sensitive biosensor based on methacrylated graphene oxide-grafted polyaniline for ascorbic acid determination

- Arrangement structure of carbon nanofiber with excellent spectral radiation characteristics

- Effect of different particle sizes of nano-SiO2 on the properties and microstructure of cement paste

- Superior Fe x N electrocatalyst derived from 1,1′-diacetylferrocene for oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline and acidic media

- Facile growth of aluminum oxide thin film by chemical liquid deposition and its application in devices

- Liquid crystallinity and thermal properties of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane/side-chain azobenzene hybrid copolymer

- Laboratory experiment on the nano-TiO2 photocatalytic degradation effect of road surface oil pollution

- Binary carbon-based additives in LiFePO4 cathode with favorable lithium storage

- Conversion of sub-µm calcium carbonate (calcite) particles to hollow hydroxyapatite agglomerates in K2HPO4 solutions

- Exact solutions of bending deflection for single-walled BNNTs based on the classical Euler–Bernoulli beam theory

- Effects of substrate properties and sputtering methods on self-formation of Ag particles on the Ag–Mo(Zr) alloy films

- Enhancing carbonation and chloride resistance of autoclaved concrete by incorporating nano-CaCO3

- Effect of SiO2 aerogels loading on photocatalytic degradation of nitrobenzene using composites with tetrapod-like ZnO

- Radiation-modified wool for adsorption of redox metals and potentially for nanoparticles

- Hydration activity, crystal structural, and electronic properties studies of Ba-doped dicalcium silicate

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of brazing joint of silver-based composite filler metal

- Polymer nanocomposite sunlight spectrum down-converters made by open-air PLD

- Cryogenic milling and formation of nanostructured machined surface of AISI 4340

- Braided composite stent for peripheral vascular applications

- Effect of cinnamon essential oil on morphological, flammability and thermal properties of nanocellulose fibre–reinforced starch biopolymer composites

- Study on influencing factors of photocatalytic performance of CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite concrete

- Improving flexural and dielectric properties of carbon fiber epoxy composite laminates reinforced with carbon nanotubes interlayer using electrospray deposition

- Scalable fabrication of carbon materials based silicon rubber for highly stretchable e-textile sensor

- Degradation modeling of poly-l-lactide acid (PLLA) bioresorbable vascular scaffold within a coronary artery

- Combining Zn0.76Co0.24S with S-doped graphene as high-performance anode materials for lithium- and sodium-ion batteries

- Synthesis of functionalized carbon nanotubes for fluorescent biosensors

- Effect of nano-silica slurry on engineering, X-ray, and γ-ray attenuation characteristics of steel slag high-strength heavyweight concrete

- Incorporation of redox-active polyimide binder into LiFePO4 cathode for high-rate electrochemical energy storage

- Microstructural evolution and properties of Cu–20 wt% Ag alloy wire by multi-pass continuous drawing

- Transparent ultraviolet-shielding composite films made from dispersing pristine zinc oxide nanoparticles in low-density polyethylene

- Microfluidic-assisted synthesis and modelling of monodispersed magnetic nanocomposites for biomedical applications

- Preparation and piezoresistivity of carbon nanotube-coated sand reinforced cement mortar

- Vibrational analysis of an irregular single-walled carbon nanotube incorporating initial stress effects

- Study of the material engineering properties of high-density poly(ethylene)/perlite nanocomposite materials

- Single pulse laser removal of indium tin oxide film on glass and polyethylene terephthalate by nanosecond and femtosecond laser

- Mechanical reinforcement with enhanced electrical and heat conduction of epoxy resin by polyaniline and graphene nanoplatelets

- High-efficiency method for recycling lithium from spent LiFePO4 cathode

- Degradable tough chitosan dressing for skin wound recovery

- Static and dynamic analyses of auxetic hybrid FRC/CNTRC laminated plates

- Review articles

- Carbon nanomaterials enhanced cement-based composites: advances and challenges

- Review on the research progress of cement-based and geopolymer materials modified by graphene and graphene oxide

- Review on modeling and application of chemical mechanical polishing

- Research on the interface properties and strengthening–toughening mechanism of nanocarbon-toughened ceramic matrix composites

- Advances in modelling and analysis of nano structures: a review

- Mechanical properties of nanomaterials: A review

- New generation of oxide-based nanoparticles for the applications in early cancer detection and diagnostics

- A review on the properties, reinforcing effects, and commercialization of nanomaterials for cement-based materials

- Recent development and applications of nanomaterials for cancer immunotherapy

- Advances in biomaterials for adipose tissue reconstruction in plastic surgery

- Advances of graphene- and graphene oxide-modified cementitious materials

- Theories for triboelectric nanogenerators: A comprehensive review

- Nanotechnology of diamondoids for the fabrication of nanostructured systems

- Material advancement in technological development for the 5G wireless communications

- Nanoengineering in biomedicine: Current development and future perspectives

- Recent advances in ocean wave energy harvesting by triboelectric nanogenerator: An overview

- Application of nanoscale zero-valent iron in hexavalent chromium-contaminated soil: A review

- Carbon nanotube–reinforced polymer composite for electromagnetic interference application: A review

- Functionalized layered double hydroxide applied to heavy metal ions absorption: A review

- A new classification method of nanotechnology for design integration in biomaterials

- Finite element analysis of natural fibers composites: A review

- Phase change materials for building construction: An overview of nano-/micro-encapsulation

- Recent advance in surface modification for regulating cell adhesion and behaviors

- Hyaluronic acid as a bioactive component for bone tissue regeneration: Fabrication, modification, properties, and biological functions

- Theoretical calculation of a TiO2-based photocatalyst in the field of water splitting: A review

- Two-photon polymerization nanolithography technology for fabrication of stimulus-responsive micro/nano-structures for biomedical applications

- A review of passive methods in microchannel heat sink application through advanced geometric structure and nanofluids: Current advancements and challenges

- Stress effect on 3D culturing of MC3T3-E1 cells on microporous bovine bone slices

- Progress in magnetic Fe3O4 nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging

- Synthesis of graphene: Potential carbon precursors and approaches

- A comprehensive review of the influences of nanoparticles as a fuel additive in an internal combustion engine (ICE)

- Advances in layered double hydroxide-based ternary nanocomposites for photocatalysis of contaminants in water

- Analysis of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite structures: A review

- Application of nanomaterials in ultra-high performance concrete: A review

- Therapeutic strategies and potential implications of silver nanoparticles in the management of skin cancer

- Advanced nickel nanoparticles technology: From synthesis to applications

- Cobalt magnetic nanoparticles as theranostics: Conceivable or forgettable?

- Progress in construction of bio-inspired physico-antimicrobial surfaces

- From materials to devices using fused deposition modeling: A state-of-art review

- A review for modified Li composite anode: Principle, preparation and challenge

- Naturally or artificially constructed nanocellulose architectures for epoxy composites: A review

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Generalized locally-exact homogenization theory for evaluation of electric conductivity and resistance of multiphase materials

- Enhancing ultra-early strength of sulphoaluminate cement-based materials by incorporating graphene oxide

- Characterization of mechanical properties of epoxy/nanohybrid composites by nanoindentation

- Graphene and CNT impact on heat transfer response of nanocomposite cylinders

- A facile and simple approach to synthesis and characterization of methacrylated graphene oxide nanostructured polyaniline nanocomposites

- Ultrasmall Fe3O4 nanoparticles induce S-phase arrest and inhibit cancer cells proliferation

- Effect of aging on properties and nanoscale precipitates of Cu-Ag-Cr alloy

- Effect of nano-strengthening on the properties and microstructure of recycled concrete

- Stabilizing effect of methylcellulose on the dispersion of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in cementitious composites

- Preparation and electromagnetic properties characterization of reduced graphene oxide/strontium hexaferrite nanocomposites

- Interfacial characteristics of a carbon nanotube-polyimide nanocomposite by molecular dynamics simulation

- Preparation and properties of 3D interconnected CNTs/Cu composites

- On factors affecting surface free energy of carbon black for reinforcing rubber

- Nano-silica modified phenolic resin film: manufacturing and properties

- Experimental study on photocatalytic degradation efficiency of mixed crystal nano-TiO2 concrete

- Halloysite nanotubes in polymer science: purification, characterization, modification and applications

- Cellulose hydrogel skeleton by extrusion 3D printing of solution

- Crack closure and flexural tensile capacity with SMA fibers randomly embedded on tensile side of mortar beams

- An experimental study on one-step and two-step foaming of natural rubber/silica nanocomposites

- Utilization of red mud for producing a high strength binder by composition optimization and nano strengthening

- One-pot synthesis of nano titanium dioxide in supercritical water

- Printability of photo-sensitive nanocomposites using two-photon polymerization

- In situ synthesis of expanded graphite embedded with amorphous carbon-coated aluminum particles as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries

- Effect of nano and micro conductive materials on conductive properties of carbon fiber reinforced concrete

- Tribological performance of nano-diamond composites-dispersed lubricants on commercial cylinder liner mating with CrN piston ring

- Supramolecular ionic polymer/carbon nanotube composite hydrogels with enhanced electromechanical performance

- Genetic mechanisms of deep-water massive sandstones in continental lake basins and their significance in micro–nano reservoir storage systems: A case study of the Yanchang formation in the Ordos Basin

- Effects of nanoparticles on engineering performance of cementitious composites reinforced with PVA fibers

- Band gap manipulation of viscoelastic functionally graded phononic crystal

- Pyrolysis kinetics and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/bamboo particle biocomposites: Effect of particle size distribution

- Manipulating conductive network formation via 3D T-ZnO: A facile approach for a CNT-reinforced nanocomposite

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of WC–Ni multiphase ceramic materials with NiCl2·6H2O as a binder

- Effect of ball milling process on the photocatalytic performance of CdS/TiO2 composite

- Berberine/Ag nanoparticle embedded biomimetic calcium phosphate scaffolds for enhancing antibacterial function

- Effect of annealing heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of nonequiatomic CoCrFeNiMo medium-entropy alloys prepared by hot isostatic pressing

- Corrosion behaviour of multilayer CrN coatings deposited by hybrid HIPIMS after oxidation treatment

- Surface hydrophobicity and oleophilicity of hierarchical metal structures fabricated using ink-based selective laser melting of micro/nanoparticles

- Research on bond–slip performance between pultruded glass fiber-reinforced polymer tube and nano-CaCO3 concrete

- Antibacterial polymer nanofiber-coated and high elastin protein-expressing BMSCs incorporated polypropylene mesh for accelerating healing of female pelvic floor dysfunction

- Effects of Ag contents on the microstructure and SERS performance of self-grown Ag nanoparticles/Mo–Ag alloy films

- A highly sensitive biosensor based on methacrylated graphene oxide-grafted polyaniline for ascorbic acid determination

- Arrangement structure of carbon nanofiber with excellent spectral radiation characteristics

- Effect of different particle sizes of nano-SiO2 on the properties and microstructure of cement paste

- Superior Fe x N electrocatalyst derived from 1,1′-diacetylferrocene for oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline and acidic media

- Facile growth of aluminum oxide thin film by chemical liquid deposition and its application in devices

- Liquid crystallinity and thermal properties of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane/side-chain azobenzene hybrid copolymer

- Laboratory experiment on the nano-TiO2 photocatalytic degradation effect of road surface oil pollution

- Binary carbon-based additives in LiFePO4 cathode with favorable lithium storage

- Conversion of sub-µm calcium carbonate (calcite) particles to hollow hydroxyapatite agglomerates in K2HPO4 solutions

- Exact solutions of bending deflection for single-walled BNNTs based on the classical Euler–Bernoulli beam theory

- Effects of substrate properties and sputtering methods on self-formation of Ag particles on the Ag–Mo(Zr) alloy films

- Enhancing carbonation and chloride resistance of autoclaved concrete by incorporating nano-CaCO3

- Effect of SiO2 aerogels loading on photocatalytic degradation of nitrobenzene using composites with tetrapod-like ZnO

- Radiation-modified wool for adsorption of redox metals and potentially for nanoparticles

- Hydration activity, crystal structural, and electronic properties studies of Ba-doped dicalcium silicate

- Microstructure and mechanical properties of brazing joint of silver-based composite filler metal

- Polymer nanocomposite sunlight spectrum down-converters made by open-air PLD

- Cryogenic milling and formation of nanostructured machined surface of AISI 4340

- Braided composite stent for peripheral vascular applications

- Effect of cinnamon essential oil on morphological, flammability and thermal properties of nanocellulose fibre–reinforced starch biopolymer composites

- Study on influencing factors of photocatalytic performance of CdS/TiO2 nanocomposite concrete

- Improving flexural and dielectric properties of carbon fiber epoxy composite laminates reinforced with carbon nanotubes interlayer using electrospray deposition

- Scalable fabrication of carbon materials based silicon rubber for highly stretchable e-textile sensor

- Degradation modeling of poly-l-lactide acid (PLLA) bioresorbable vascular scaffold within a coronary artery

- Combining Zn0.76Co0.24S with S-doped graphene as high-performance anode materials for lithium- and sodium-ion batteries

- Synthesis of functionalized carbon nanotubes for fluorescent biosensors

- Effect of nano-silica slurry on engineering, X-ray, and γ-ray attenuation characteristics of steel slag high-strength heavyweight concrete

- Incorporation of redox-active polyimide binder into LiFePO4 cathode for high-rate electrochemical energy storage

- Microstructural evolution and properties of Cu–20 wt% Ag alloy wire by multi-pass continuous drawing

- Transparent ultraviolet-shielding composite films made from dispersing pristine zinc oxide nanoparticles in low-density polyethylene

- Microfluidic-assisted synthesis and modelling of monodispersed magnetic nanocomposites for biomedical applications

- Preparation and piezoresistivity of carbon nanotube-coated sand reinforced cement mortar

- Vibrational analysis of an irregular single-walled carbon nanotube incorporating initial stress effects

- Study of the material engineering properties of high-density poly(ethylene)/perlite nanocomposite materials

- Single pulse laser removal of indium tin oxide film on glass and polyethylene terephthalate by nanosecond and femtosecond laser

- Mechanical reinforcement with enhanced electrical and heat conduction of epoxy resin by polyaniline and graphene nanoplatelets

- High-efficiency method for recycling lithium from spent LiFePO4 cathode

- Degradable tough chitosan dressing for skin wound recovery

- Static and dynamic analyses of auxetic hybrid FRC/CNTRC laminated plates

- Review articles

- Carbon nanomaterials enhanced cement-based composites: advances and challenges

- Review on the research progress of cement-based and geopolymer materials modified by graphene and graphene oxide

- Review on modeling and application of chemical mechanical polishing

- Research on the interface properties and strengthening–toughening mechanism of nanocarbon-toughened ceramic matrix composites

- Advances in modelling and analysis of nano structures: a review

- Mechanical properties of nanomaterials: A review

- New generation of oxide-based nanoparticles for the applications in early cancer detection and diagnostics

- A review on the properties, reinforcing effects, and commercialization of nanomaterials for cement-based materials

- Recent development and applications of nanomaterials for cancer immunotherapy

- Advances in biomaterials for adipose tissue reconstruction in plastic surgery

- Advances of graphene- and graphene oxide-modified cementitious materials

- Theories for triboelectric nanogenerators: A comprehensive review

- Nanotechnology of diamondoids for the fabrication of nanostructured systems

- Material advancement in technological development for the 5G wireless communications

- Nanoengineering in biomedicine: Current development and future perspectives

- Recent advances in ocean wave energy harvesting by triboelectric nanogenerator: An overview

- Application of nanoscale zero-valent iron in hexavalent chromium-contaminated soil: A review

- Carbon nanotube–reinforced polymer composite for electromagnetic interference application: A review

- Functionalized layered double hydroxide applied to heavy metal ions absorption: A review

- A new classification method of nanotechnology for design integration in biomaterials

- Finite element analysis of natural fibers composites: A review

- Phase change materials for building construction: An overview of nano-/micro-encapsulation

- Recent advance in surface modification for regulating cell adhesion and behaviors

- Hyaluronic acid as a bioactive component for bone tissue regeneration: Fabrication, modification, properties, and biological functions

- Theoretical calculation of a TiO2-based photocatalyst in the field of water splitting: A review

- Two-photon polymerization nanolithography technology for fabrication of stimulus-responsive micro/nano-structures for biomedical applications

- A review of passive methods in microchannel heat sink application through advanced geometric structure and nanofluids: Current advancements and challenges

- Stress effect on 3D culturing of MC3T3-E1 cells on microporous bovine bone slices

- Progress in magnetic Fe3O4 nanomaterials in magnetic resonance imaging

- Synthesis of graphene: Potential carbon precursors and approaches

- A comprehensive review of the influences of nanoparticles as a fuel additive in an internal combustion engine (ICE)

- Advances in layered double hydroxide-based ternary nanocomposites for photocatalysis of contaminants in water

- Analysis of functionally graded carbon nanotube-reinforced composite structures: A review

- Application of nanomaterials in ultra-high performance concrete: A review

- Therapeutic strategies and potential implications of silver nanoparticles in the management of skin cancer

- Advanced nickel nanoparticles technology: From synthesis to applications

- Cobalt magnetic nanoparticles as theranostics: Conceivable or forgettable?

- Progress in construction of bio-inspired physico-antimicrobial surfaces

- From materials to devices using fused deposition modeling: A state-of-art review

- A review for modified Li composite anode: Principle, preparation and challenge

- Naturally or artificially constructed nanocellulose architectures for epoxy composites: A review