Abstract

Background

Many factors contribute to successful nerve reconstruction. The correct technique of anastomosis is one of the key elements that determine the final result of a surgery. The aim of this study is to examine how useful an electromyography (EMG) can be as an objective intraoperative anastomosis assessment method.

Methods

The study material included 12 rats. Before the surgery, the function of the sciatic nerve was tested using hind paw prints. Then, both nerves were cut. The left nerve was sutured side-to-side, and the right nerve was sutured end-to-end. Intraoperative electromyography was performed. After 4 weeks, the rats were reassessed using the hind paw print analysis and electromyography.

Results

An analysis of left and right hind paw prints did not reveal any significant differences between the length of the steps, the spread of the digits in the paws, or the deviation of a paw. The width of the steps also did not change.

Electromyography revealed that immediately after a nerve anastomosis (as well as 4 weeks after the surgery), better nerve conduction was observed through an end-to-end anastomosis. Four weeks after the surgery, better nerve conduction was seen distally to the end-to-end anastomosis.

Conclusions

The results indicate that in acute nerve injuries intraoperative electromyography may be useful to obtain unbiased information on whether the nerve anastomosis has been performed correctly – for example, in limb replantation.

When assessing a nerve during a procedure, EMG should be first performed distally to the anastomosis (the part of the nerve leading to muscle fibers) and then proximally to the anastomosis (the proximal part of the nerve). Similar EMG results can be interpreted as a correct nerve anastomosis.

The function of the distal part of the nerve and the muscle remains intact if the neuromuscular transmission is sustained.

1 Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury with a loss of axonal continuity can be caused by major trauma or oncological resection. In such cases, the primary repair of a nerve gives the highest chance of regaining lost functions. The most common reconstruction method is an end-to-end anastomosis or, if tension-free repair is not possible, nerve grafting (usually with the sural nerve) [1]. Many factors determine the success of such nerve reconstruction. The most important reconstruction method is the correct anastomosis technique.

The decision to finish a nerve reconstruction is made when the anastomosis is accepted as technically correct. If considered faulty, it is repeated. Therefore, the only way to evaluate an anastomosis during an operation is by the surgeon’s judgment. Regardless of the clinical experience or quality of surgical loupes used, such assessment is always subjective. The authors of this article looked for another method to verify the visual intraoperative evaluation of nerve anastomosis.

The goal of this study is to examine how useful is EMG as an objective intraoperative nerve anastomosis assessment tool.

2 Materials and methods

Study material included 12 male Wistar rats weighing 250–300 g. Before surgery, sciatic nerve functions were evaluated by analyzing imprints of the hind paws. The hind paws were covered with ink, and animals were placed in a tunnel lined with paper. After covering a distance of 1 m, the length of steps and the geometry of their footprint were measured (the walking-track analysis) [2,3]. The animals were then anesthetized with a subcutaneous injection of ketamine hydrochloride at a dose of 120 mg/kg. After anesthesia, sciatic nerves were exposed on both limbs, and an EMG was performed. The nerves were cut, and a subsequent EMG was performed to confirm the loss of nerve conduction. The left sciatic nerve was sutured side-to-side, essentially preventing nerve bundles from contacting. This was to simulate a faulty anastomosis. The right sciatic nerve was sutured end-to-end, paying attention to the correct adaptation of the ends, ensuring the proper contact of nerve bundles. The anastomosis was performed by applying four 10/0 stitches with the use of surgical loupes magnifying the field 4.5 times. Afterward, another EMG examination was performed to assess the conduction through the anastomoses. Surgical wounds were closed with 4/0 skin sutures. Following the surgery, animals received standard food and drinking water without restrictions. After 4 weeks, the footprints were again sampled over the distance of 1 m. Then (after anesthesia) sciatic nerves were exposed, revealing the site of anastomosis. A nerve conduction test was performed.

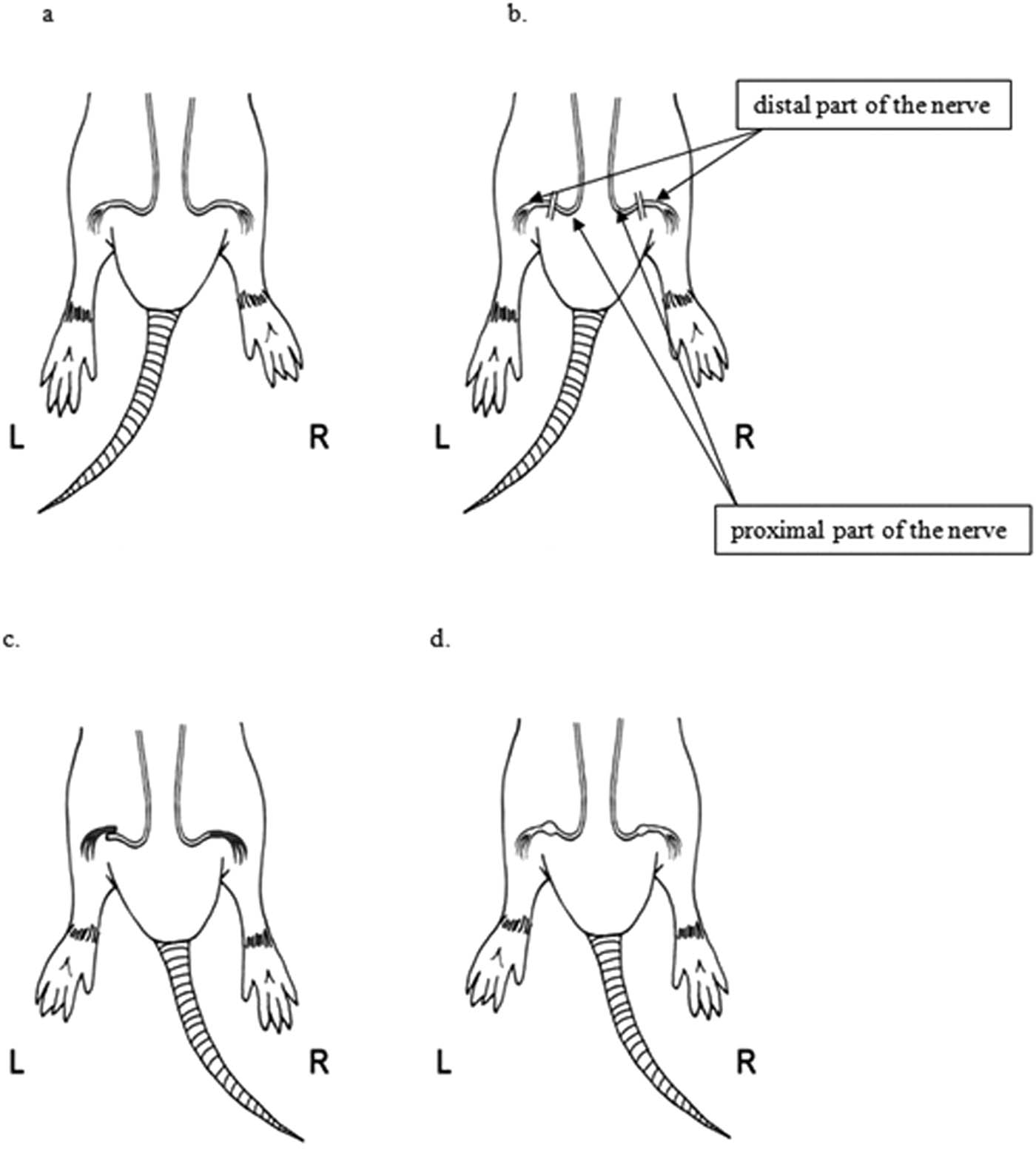

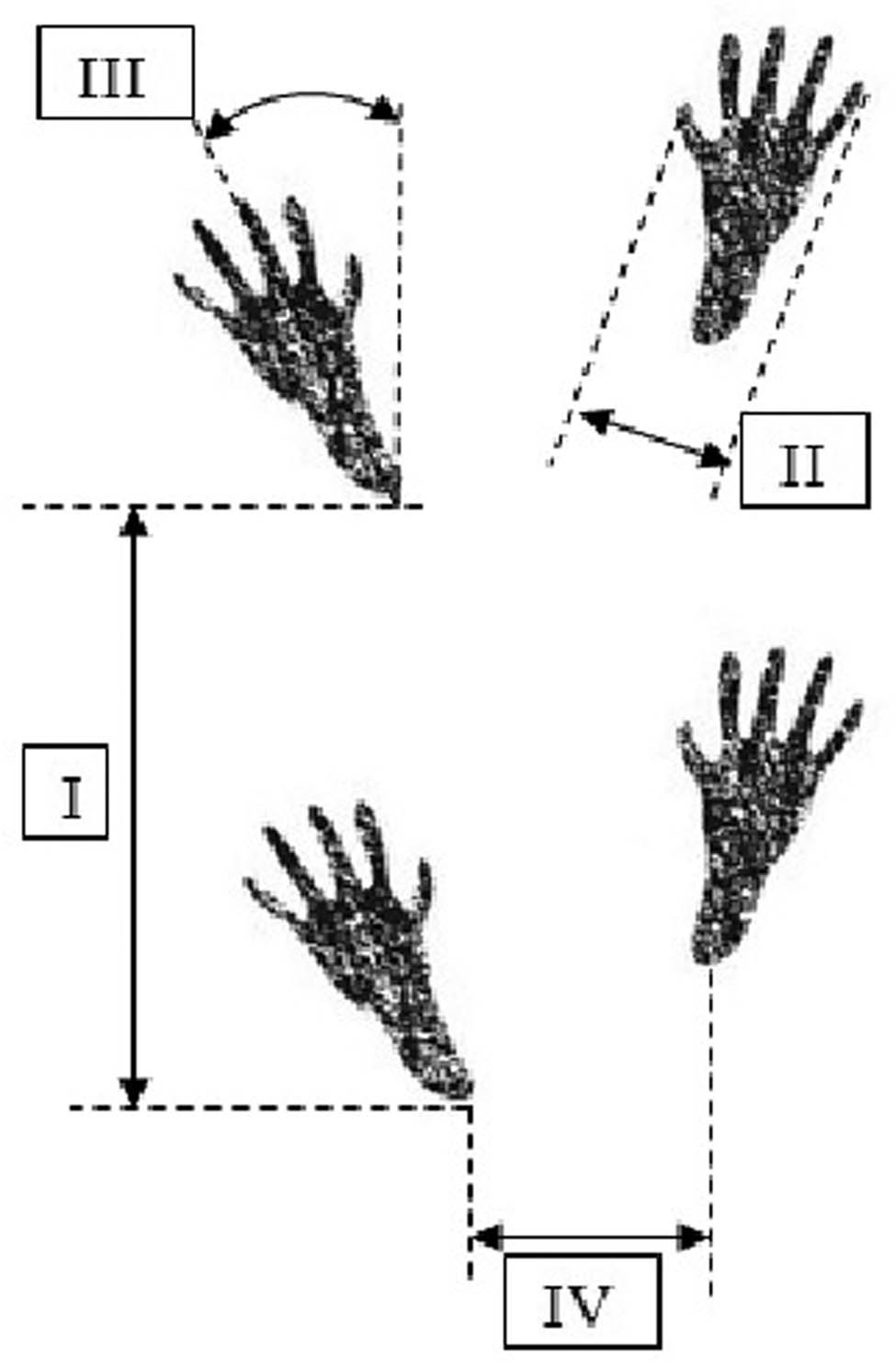

Nerve anastomoses were sampled for microscopic examination. Shortly thereafter, the animals were euthanized with an injection of pentobarbital sodium. EMG was performed using a NerveMonitor C2 (inomed Medizintechnik GmbH, Germany). The nerves were stimulated at 2 mA. Tissues for microscopic examination were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The presence of nerve bundles in the anastomosis was assessed. The T-test for dependent samples was used for statistical calculations. The Local Ethics Committee approval number 7/2015 was obtained for conducting experiments on animals. The animals showed no signs of suffering in the postoperative period; therefore, there was no need for additional pain management. Figures 1 and 2 schematically present surgical technique and the method of measuring gait parameters based on the paw prints, respectively.

The schematic representation of (a) exposure of sciatic nerves, (b) transecting the nerves, (c) anastomosis L (left side) side-to-side, R (right side) end-to-end, and (d) follow-up after 4 weeks.

The a schematic representation of gait assessment based on the measurements of the hind paw prints: (I) step length, (II) digit spread (between digits I–V), (III) foot deviation (angle between the foot axis and the walking axis), and (IV) step width (distance between the left heel and the right heel).

3 Results

Individual gait parameters as an indirect measurement of the sciatic nerve function are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The length of the steps (distance between successive footprints on the right and left side [mm]), the spread of the digits (distance between digits I and V [mm]), and the deviation of the foot (angle between the axis of the foot and the axis of the body [°])

| No. | Step parameters | Left | Right | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before cutting | Follow-up after 4 weeks | Before cutting | Follow-up after 4 weeks | ||

| 1 | Step length [mm] | 68 | 101 | 68 | 117 |

| digit spread [mm] | 23 | 12 | 24 | 11 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 32 | 19 | 27 | 32 | |

| 2 | Step length [mm] | 105 | 85 | 120 | 100 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 23 | 12 | 23 | 11 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 16 | 23 | 15 | 19 | |

| 3 | Step length [mm] | 145 | 112 | 135 | 105 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 24 | 12 | 24 | 13 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| 4 | Step length [mm] | 132 | 120 | 145 | 107 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 20 | 10 | 21 | 14 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 17 | 20 | 29 | 24 | |

| 5 | Step length [mm] | 143 | 145 | 147 | 120 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 21 | 13 | 21 | 11 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 22 | 26 | 27 | 25 | |

| 6 | Step length [mm] | 160 | 120 | 144 | 120 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 24 | 11 | 24 | 16 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 27 | 24 | 26 | 29 | |

| 7 | Step length [mm] | 160 | 93 | 150 | 90 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 23 | 13 | 23 | 15 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 9 | 17 | 9 | 13 | |

| 8 | Step length [mm] | 140 | 123 | 140 | 120 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 21 | 10 | 20 | 10 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 24 | 11 | 19 | 23 | |

| 9 | Step length [mm] | 120 | 115 | 120 | 117 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 20 | 10 | 20 | 10 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 23 | 22 | 23 | 14 | |

| 10 | Step length [mm] | 150 | 113 | 153 | 115 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 23 | 13 | 23 | 11 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 23 | 16 | 24 | 18 | |

| 11 | Step length [mm] | 120 | 110 | 120 | 112 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 22 | 12 | 24 | 12 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 20 | 10 | 22 | 14 | |

| 12 | Step length [mm] | 118 | 109 | 120 | 107 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 24 | 12 | 24 | 12 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | |

| Average | Step length [mm] | 130.08 | 112.16 | 130.16 | 110.83 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 22.33 | 11.66 | 22.58 | 12.16 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 20.00 | 18.33 | 21.16 | 20.33 | |

| Standard deviation | Step length [mm] | 26.13 | 15.29 | 23.36 | 9.35 |

| Digit spread [mm] | 1.49 | 1.15 | 1.62 | 1.94 | |

| Deviation of the foot [°] | 6.50 | 5.24 | 6.20 | 6.38 | |

The width of the steps (the distance between the hind paws) before the transection of the nerves and 4 weeks after reconstruction

| No. | Step width [mm] | |

|---|---|---|

| Before transection | Follow-up after 4 weeks | |

| 1 | 54 | 40 |

| 2 | 55 | 65 |

| 3 | 35 | 36 |

| 4 | 52 | 55 |

| 5 | 35 | 35 |

| 6 | 39 | 25 |

| 7 | 42 | 48 |

| 8 | 36 | 51 |

| 9 | 50 | 34 |

| 10 | 45 | 60 |

| 11 | 47 | 55 |

| 12 | 50 | 60 |

| Average | 45.00 | 47.00 |

| Standard deviation | 7.44 | 12.69 |

The length of the steps was statistically shorter (p = 0.03) 4 weeks after the side-to-side anastomosis was performed, compared to the length before the nerve was cut. Digit spread was statistically smaller (curled-up foot; p < 0.01). However, there were no statistical differences in the deviation of the foot from the walking axis.

The length of steps 4 weeks after the end-to-end anastomosis was statistically shorter (p = 0.03) compared to the length of the step before the nerve was cut. Digit spread was statistically smaller (curled up foot; p = 0.01). There was no difference in the deviation of the foot from the walking axis.

The width of the steps (the distance between the hind paws) did not change 4 weeks after the nerve reconstruction.

Statistical analysis showed that the function of the sciatic nerve, expressed in the ability to walk, was statistically worse, regardless of the manner of the anastomosis. The comparison of walking imbalances 4 weeks after the nerve anastomosis did not reveal any statistically significant differences between side-to-side and end-to-end anastomosis in regards to the length of steps, digit spread, and foot deviation.

The measurements obtained in the electrophysiological examination of sciatic nerves are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Electrophysiological parameters upon stimulating the sciatic nerves shortly after the surgical anastomosis.

| Lp. | Stimulation response | Directly after the nerve anastomosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left sciatic nerve, side-to-side anastomosis | Right sciatic nerve, end-to-end anastomosis | ||||

| The proximal part of the nerve | The distal part of the nerve | The proximal part of the nerve | The distal part of the nerve | ||

| 1 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.39 | 6.51 | 6.5 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.35 | 1.05 | 1.05 | |

| 2 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.48 | 6.57 | 6.58 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.45 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| 3 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.5 | 6.48 | 6.5 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.35 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| 4 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.46 | 0 | 1.63 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.15 | 0 | 1.3 | |

| 5 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 5.91 | 5.83 | 5.81 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1 | |

| 6 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.58 | 6.48 | 6.58 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | |

| 7 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 6.42 | 6.58 | 6.58 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.15 | |

| 8 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0.72 | 5.93 | 5.9 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.4 | 1.05 | 1.1 | |

| 9 | Voltage [mV] | 0.11 | 6.5 | 6.45 | 6.37 |

| Time [ms] | 6.95 | 1.1 | 1.15 | 2.6 | |

| 10 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 3.6 | 6.52 | 6.52 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.95 | 1.15 | 1.2 | |

| 11 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 4.51 | 5.33 | 4.62 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.25 | 1.1 | 1.45 | |

| 12 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 3.52 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 1.35 | 1.05 | 1.05 | |

| Average | Voltage [mV] | 0.0092 | 5.3642 | 5.7483 | 5.5925 |

| Time [ms] | 0.5791 | 1.3625 | 1.1708 | 1.2833 | |

| Standard deviation | Voltage [mV] | 0.0317 | 1.7968 | 1.8505 | 1.5702 |

| Time [ms] | 2.0063 | 0.2506 | 0.4673 | 0.4323 | |

The electrophysiological study parameters conducted after stimulating the sciatic nerves 4 weeks after the nerve anastomosis was performed

| No. | Stimulation response | Follow-up after 4 weeks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left sciatic nerve, side-to-side anastomosis | Right sciatic nerve, end-to-end anastomosis | ||||

| The proximal part of the nerve | The distal part of the nerve | The proximal part of the nerve | The distal part of the nerve | ||

| 1 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.41 | 0.31 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 5.25 | 3.86 | |

| 2 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 5.65 | 4.75 | |

| 3 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 6.2 | 5.7 | |

| 4 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.11 | 0 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 0 | |

| 5 | Voltage [mV] | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 |

| Time [ms] | 9.06 | 8.35 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 1.13 | 1.19 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 5.8 | |

| 7 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 7.6 | 7.75 | |

| 8 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 6.15 | 12.45 | 12.15 | |

| 10 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 9.6 | 12.65 | |

| 11 | Voltage [mV] | 0.2 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.13 |

| Time [ms] | 1.85 | 0 | 1.15 | 2.65 | |

| 12 | Voltage [mV] | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Time [ms] | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | |

| Average | Voltage [mV] | 0.0258 | 0.0075 | 0.9091 | 1.2083 |

| Time [ms] | 0.2658 | 0.2458 | 5.7166 | 4.6414 | |

| Standard deviation | Voltage [mV] | 0.0633 | 0.0186 | 2.6213 | 2.8607 |

| Time [ms] | 0.3185 | 0.3293 | 4.8758 | 4.2988 | |

The values of potentials registered in newly made side-to-side anastomoses were statistically lower (p < 0.001) in comparison to a healthy nerve. Zero conduction time is understood as a complete absence of conduction in a side-to-side anastomosis.

Neither the values of the potentials registered passing through the newly created end-to-end anastomoses nor the conduction time showed differences in comparison to a healthy nerve. The result indicates that a correctly performed anastomosis of a freshly damaged nerve ensures proper conduction of the impulse to the muscle.

The potentials registered passing through newly created anastomoses were higher in the end-to-end anastomoses than that in the side-to-side anastomoses (p < 0.001). However, there were no statistical differences in conduction time. These results indicate that an end-to-end anastomosis (i.e., a technically correct nerve anastomosis) provides better conductivity.

An analysis of potentials registered on stimulating the distal part of the nerve 4 weeks after performing the anastomosis revealed that in end-to-end anastomoses, potentials were higher (p = 0.02). In contrast, the conduction time through end-to-end anastomoses was longer (p = 0.02). This means that the distal part of the nerve and the muscles beyond a side-to-side anastomosis did not regain function.

Moreover, there was a significant difference (p = 0.02) when comparing the potentials registered on stimulating the proximal part of the nerve in side-to-side and end-to-end anastomoses. The potentials registered in side-to-side anastomoses were higher. The conduction time in the end-to-end anastomosis was longer (p = 0.049), which means that side-to-side anastomoses did not conduct any impulses.

An analysis of a correlation between gait parameters and the results of electrophysiological studies did not reveal statistical differences, meaning that the function of both limbs was impaired, regardless of the anastomosis technique used.

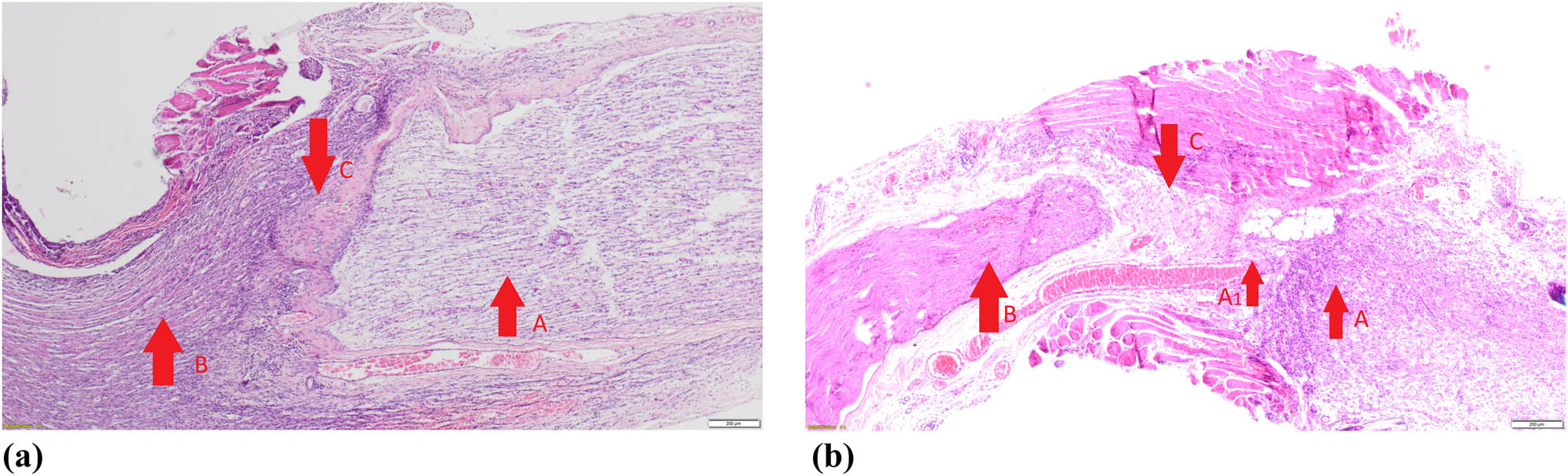

The morphological analysis of nerve anastomoses at 400× magnification showed nerve fibers both of the proximal (arrow B) and distal sciatic nerve stumps (arrow A) with a thick layer of connective scar tissue in the middle (arrow C) in Figure 3a, which was confirmed to be blocking nerve conduction in electrophysiological examinations. Evaluation of an end-to-end anastomosis (Figure 3b) showed loose connective tissue (arrow C) and single nerve endings passing through the scar (arrow A1) between the proximal and distal ends of the sciatic nerve (arrows A and B), which corresponds with a positive response on stimulation in EMG.

Pathomorphological examples of a side-to-side (a) and an end-to-end (b) nerve anastomoses.

4 Discussion

In side-to-side anastomoses, nerve stimulation on the proximal end of the anastomosis after 4 weeks did not show conduction in ten cases. These results seem to confirm that a faulty anastomosis, in which the bundles of the nerve endings are not in contact with each other, dramatically lowers the chance of nerve function return. In two cases, a follow-up EMG after 4 weeks showed nerve conduction. This phenomenon was described previously by other authors who described the ingrowth of nerve fibers in the end-to-side [2,4,5,6,7,8,9] or the side-to-side anastomosis [3,10]. In the aforementioned studies, a nerve sheath was cut at the site before the anastomosis was made to ensure direct contact of nerve fibers between the end and the side of the fused nerves. This maneuver was supposed to increase the likelihood of reinnervation after nerve reconstruction. In our study, the sides of the fused nerves still had their sheath on. It is possible that suturing created micro-openings in the sheath, enabling nerve fibers to grow in and eventually allowing nerve function return.

In nerves stimulated 4 weeks after an end-to-end anastomosis, nerve conduction was achieved in ten cases. Such results are consistent with the literature, confirming that good reinnervation depends on the correct anastomosis technique.

After 4 weeks, stimulation of the proximal and distal end of a side-to-side anastomosis showed muscle response in two cases. Based on this result, one could assume that a lack of muscle response could be either due to the lack of conduction in the anastomosis or degenerative changes in the denervated muscle. However, when analyzing the end-to-end nerve conduction results (in which muscular response was obtained after the proximal end stimulation), it seems that the primary reason for the lack of muscle response after side-to-side anastomoses is the lack of conductivity in these anastomoses. Muscle degeneration is secondary.

Interestingly, performing EMG on freshly anastomosed nerves demonstrated that the nerve sutured end-to-end conducted electric impulses in 12 cases, while the nerve sutured side-to-side only in one case. Conduction of impulses in a reconstructed nerve was ensured by the direct contact of nerve bundles. In end-to-end anastomoses, this result seems obvious. However, in side-to-side anastomoses, nerve bundles were not in contact. One case of conduction can probably be explained by direct contact of nerve fibers resulting from the micro-damage of the sheath caused by the suturing. Conduction through an end-to-end anastomosis also correlated with later nerve function. It seems, therefore, that intraoperative EMG examination can be used to confirm the correct approximation and alignment of nerve bundles in anastomoses. Literature describes the use of EMG for late evaluation of nerve regeneration [4,9,11,12,13,14].

In two subjects with an end-to-end anastomosis, a follow-up EMG proximal to the anastomosis after 4 weeks did not show nerve conduction. In one of these cases, nerve anastomosis separation was observed during the surgical reevaluation of the nerve. It could have been caused by the motor activity of the animal causing repetitive stress on the anastomosis. Similar complications are observed in clinical practice in patients who do not adhere to postoperative guidelines of rest and limb immobilization after surgery.

When interpreting the results of this experiment and similar functional disorders of both limbs regardless of the technique used for nerve anastomosis, it can be assumed that the amount of time required to restore the function of a damaged nerve leads to degenerative changes in muscles it innervates. Thus, regardless of a correctly performed nerve anastomosis, the excessive time needed for nerve regeneration causes changes in the muscles and leads to poor results. Electrophysiological examination showed better nerve function after an end-to-end anastomosis. However, the final functional outcome also depends on another component, that is, degenerative changes in the muscles. This is confirmed by clinical observations with significantly worse results of motor or mixed nerve reconstructions if done more than 1 year after the injury [15,16].

5 Conclusions

The results indicate that in acute nerve injuries intraoperative electromyography may be useful to obtain unbiased information on whether the nerve anastomosis has been performed correctly – for example, in limb replantation.

When assessing a nerve during a procedure, EMG should be first performed distally to the anastomosis (the part of the nerve leading to muscle fibers) and then proximally to the anastomosis (the proximal part of the nerve). Similar EMG results can be interpreted as a correct nerve anastomosis.

The function of the distal part of the nerve and of the muscle remains intact if the neuromuscular transmission is sustained.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin, Poland. Funding source did not play a role in the investigation.

Note: The research was carried out at The Animal House of the Pomeranian Medical University in Szczecin. Al. Powstańców Wielkopolskich 72, 70-111 Szczecin, Poland.

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Aberg M, Ljungberg C, Edin E, Millqvist H, Nordh E, Theorin A, et al. Clinical evaluation of a resorbable wrap-around implant as an alternative to nerve repair: a prospective, assessor-blinded, randomised clinical study of sensory, motor and functional recovery after peripheral nerve repair. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009 Nov;62(11):1503–9.10.1016/j.bjps.2008.06.041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Ulkür E, Yüksel F, Açikel C, Okar I, Celiköz B. Comparison of functional results of nerve graft, vein graft, and vein filled with muscle graft in end-to-side neurorrhaphy. Microsurgery. 2003;23(1):40–8.10.1002/micr.10076Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Yüksel F, Karacaoğlu E, Güler MM. Nerve regeneration through side-to-side neurorrhaphy sites in a rat model: a new concept in peripheral nerve surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999 Dec;104(7):2092–9.10.1097/00006534-199912000-00022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Fujiwara T, Matsuda K, Kubo T, Tomita K, Hattori R, Masuoka T, et al. Axonal supercharging technique using reverse end-to-side neurorrhaphy in peripheral nerve repair: an experimental study in the rat model. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):821–9.10.3171/JNS-07/10/0821Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Li Q, Zhang P, Yin X, Han N, Kou Y, Jiang B. Early sensory protection in reverse end-to-side neurorrhaphy to improve the functional recovery of chronically denervated muscle in rat: a pilot study. J Neurosurg. 2014 Aug;121(2):415–22.10.3171/2014.4.JNS131723Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Maciel FO, Viterbo F, Chinaque L de FC, Souza BM. Effect of electrical stimulation of the cranial tibial muscle after end-to-side neurorrhaphy of the peroneal nerve in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013 Jan;28(1):39–47.10.1590/S0102-86502013000100007Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Liu H-F, Chen Z-G, Shen H-M, Zhang H, Zhang J, Lineaweaver WC, et al. Efficacy of the end-to-side neurorrhaphies with epineural window and partial donor neurectomy in peripheral nerve repair: an experimental study in rats. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015 Jan;31(1):31–8.10.1055/s-0034-1382263Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Gao W, Liu Q, Li S, Zhang J, Li Y. End-to-side neurorrhaphy for nerve repair and function rehabilitation. J Surg Res. 2015 Aug;197(2):427–35.10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.100Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Korus L, Ross DC, Doherty CD, Miller TA. Nerve transfers and neurotization in peripheral nerve injury, from surgery to rehabilitation. J J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;87(2):188–97.10.1136/jnnp-2015-310420Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Wan H, Zhang L, Li D, Hao S, Feng J, Oudinet JP, et al. Hypoglossal-facial nerve ‘side’-to-side neurorrhaphy for persistent incomplete facial palsy. J Neurosurg. 2014 Jan;120(1):263–72.10.3171/2013.9.JNS13664Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Jeans L, Healy D, Gilchrist T. An evaluation using techniques to assess muscle and nerve regeneration of a flexible glass wrap in the repair of peripheral nerves. Vienna: Springer; 2007.10.1007/978-3-211-72958-8_5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Han D, Lu J, Xu L, Xu J. Comparison of two electrophysiological methods for the assessment of progress in a rat model of nerve repair. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(2):2392–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Haastert K, Joswig H, Jäschke K-A, Samii M, Grothe C. Nerve repair by end-to-side nerve coaptation: histologic and morphometric evaluation of axonal origin in a rat sciatic nerve model. Neurosurgery. 2010 Mar;66(3):567–76; discussion 576–7.10.1227/01.NEU.0000365768.78251.8CSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Leclère M, Badur M, Mathys M, Vögelin M. Nerve transfers for persistent traumatic peroneal nerve palsy: the inselspital bern experience. Neurosurgery. 2015;77(4):572–80.10.1227/NEU.0000000000000897Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Kaiser R, Ullas G, Havránek P, Homolková H, Miletín J, Tichá P, et al. Current concepts in peripheral nerve injury repair. Acta Chir Plast. 2017 Fall;59(2):85–91.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bhatia A, Shyam AK, Doshi P, Shah V. Nerve reconstruction: a cohort study of 93 cases of global brachial plexus palsy. Indian J Orthop. 2011 Mar;45(2):153–60.10.4103/0019-5413.77136Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Norbert Czapla et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway