Abstract

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is a type of spontaneous hemorrhagic stroke, which is caused by a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Cerebral vasospasm (CVS) is the most grievous complication of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). The aim of this study was to examine the risk factors that influence the onset of CVS that develops after endovascular coil embolization of a ruptured aneurysm.

Materials and methods

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study. The patients included in the study were 18 or more years of age, admitted within a period of 24 h of symptom onset, diagnosed and treated at a university medical center in Serbia during a 5-year period.

Results

Our study showed that the maximum recorded international normalized ratio (INR) values in patients who were not receiving anticoagulant therapy and the maximum recorded white blood cells (WBCs) were strongly associated with cerebrovascular spasm, increasing its chances 4.4 and 8.4 times with an increase of each integer of the INR value and 1,000 WBCs, respectively.

Conclusions

SAH after the rupture of cerebral aneurysms creates an endocranial inflammatory state whose intensity is probably directly related to the occurrence of vasospasm and its adverse consequences.

1 Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (ASAH) is a type of spontaneous hemorrhagic stroke, which is caused by a ruptured cerebral aneurysm in about 80% of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [1,2]. Nearly one-third of ASAH survivors develop delayed cerebral ischemia, which is caused by the narrowing of cerebral blood vessels and decreased cerebral blood flow [3,4]. Segmental or diffuse narrowing of the lumen of the intracranial arteries is also known as cerebral vasospasm (CVS) [2,5]. CVS is the most grievous complication of SAH and can be described as a deferred and self-limiting condition; furthermore, its severity is associated with the volume, density, extended presence and site of subarachnoid blood [1,3,5]. CVS that is influenced by SAH is a perplexing issue which incorporates hypovolemia, damaged auto-regulatory function and also prolonged and reversible vasculitis [6,7]. The preeminent concept for CVS prevention is maintenance of regular blood volume as well as treatment with nimodipine [8]. Currently, the only confirmed treatment for CVS is euvolemic induced hypertension, due to the fact that endovascular procedures still carry specific risks [9].

To date, various factors have been known to be linked with an increased risk of CVS after SAH. The haptoglobin phenotype is one of these factors, since the affinity of the molecule for hemoglobin depends on the extent to which it will bind free hemoglobin in the subarachnoid space and thus prevent the initiation of a series of reactions that ultimately result in vasospasm formation [10]. Intraventricular hemorrhage within ASAH is also associated with a higher incidence of vasospasm, as well as long-term use of tobacco [11]. Also, left ventricular hypertrophy detected on electrocardiography is described as a risk factor for development of CVS (odds ratio [OR] = 3.48) [12]. The correlation between cerebrospinal fluid and CVS was observed, using volumetric analysis and SAH/CSF ratio (OR = 1.03) [13].

However, the amount of data published in this field to date has been relatively limited. Most of the studies explored CVS only in patients who developed neurological symptoms after the procedure [12,14,15]. Also, in a great number of other studies, the patient population was heterogeneous, including both those treated surgically and those treated by the endovascular approach [16,17].

Considering this, the aim of this study was to examine the risk factors that influence the onset of CVS that develops after endovascular coil embolization (EE) of a ruptured aneurysm which caused SAH.

2 Materials and methods

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Center Kragujevac before any of the study procedures was initiated. The study was conducted according to the principles of Declaration of Helsinki about experimentation on human subjects and in compliance with national regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

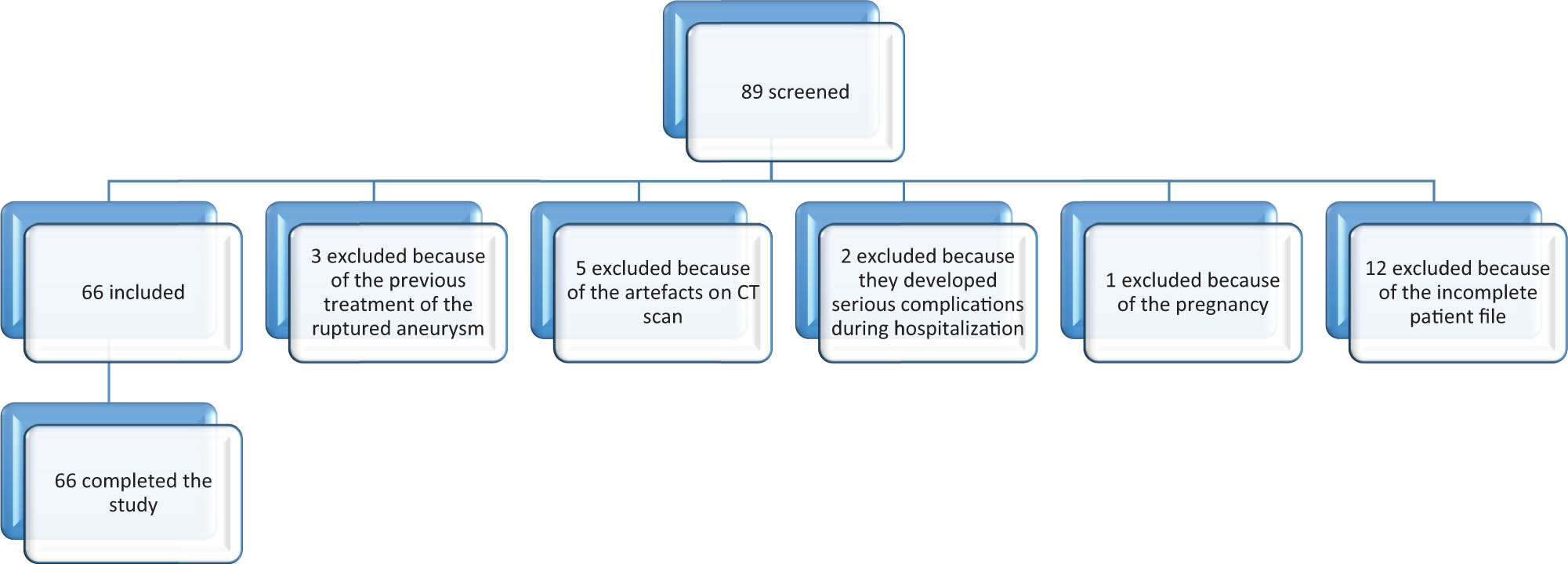

The patients included in the study satisfied the following criteria: 18 or more years of age, admitted within a period of 24 h of symptom onset, diagnosed and treated at Clinical Center Kragujevac, Serbia, during the observation period (from 01-01-2014 to 31-12-2018), and suffering from SAH caused by the rupture of an intracranial aneurysm for the first time; SAH confirmed by the CT scan on admission; rupture of an aneurysm confirmed by digital subtraction angiography (DSA); treatment of the aneurysm by EE; minimum two control CT scans after the coiling (the first CT scan was done 1 day after the endovascular procedure, the last CT was done on discharge and additional CT scans were done on demand from neurologists); and DSA after the embolization, between the 5th and 10th day. Each interventional radiology procedure was performed by the same team of two experienced neuroradiologists, and all the CT scans were evaluated by three neuroradiologists in our department. The exclusion criteria were the following: previous treatment of the ruptured aneurysm; artifacts in CT scans; patients who developed serious complications during hospitalization such as sepsis, hepatorenal dysfunction etc.; pregnant women; and incomplete patient file. Figure 1 presents the flowchart with the number of patients who were initially included and the number of excluded patients based on each of the exclusion criteria.

The study flowchart.

The diagnosis of ASAH was made if CT scan showed the presence of blood in the subarachnoid space, and DSA indicated rupture of an aneurysm. CVS was diagnosed by DSA [1,2] if the column of contrast in large cerebral arteries was decreased by more than 34% in diameter [13].

The following variables were extracted from the patient files: sociodemographic data: age, sex, residence, smoking habit, and caffeine use; symptoms and physical status prior to admission; scales: modified Rankin scale (MRS) on discharge [18], Hunt and Hesse scale (HHS) on admission [19], Fischer scale (FS) using the initial CT scan [20], and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) on admission; CT findings: hydrocephalus, brain edema, intraventricular hemorrhage, and intracerebral hemorrhage; liquid evacuation: lumbar puncture and/or ventriculoperitoneal shunt; mechanical ventilation after the endovascular procedure; aneurysm features: location, size, existence of a second unruptured aneurysm; procedure characteristics: duration of fluoroscopy and heparin dosage; duration of hospitalization, the time from admission to EE; duration of symptoms prior to hospital admission; and laboratory analysis (maximum recorded values and nadir values): blood count, coagulation tests, and biochemistry analysis.

2.1 Statistics

The study data were analyzed using SPSS version 23 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) [21]. Descriptive statistics was used for primary data processing: continuous variables were described by mean and standard deviation (if normally distributed) or by median and interquartile range (if not normally distributed), while categorical variables were presented with rates and percentages. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the data distribution. Significance of differences in the study groups was tested by the Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and by contingency tables for categorical variables. The impact of these variables on the main outcome (appearance of CVS) was investigated by univariate logistic regression at first, after which multivariable logistic regression was performed using the backward method. The model of logistic regression was built after several attempts, using the backward method; each attempt implied different combinations of independent and confounding variables. However, in order to avoid the co-linearity problem, only one value of the variables that were measured repeatedly (e.g. white cell count before, during and after the EE) was entered at a time (i.e. repeating measures of the same variable were never entered in the same model building attempt). Effects of the variables obtained in the final model were adjusted for their simultaneous presence. The quality of the multivariable logistic regression model was tested by Hosmer–Lemeshow, Cox–Snell and Nagelkerke tests.

3 Results

In total 66 patients were enrolled, and all of them completed the study, without drop-outs. The main characteristics of the study group are shown in Table 1, while for the sake of clarity the rest are listed in the supplementary file. The results of univariate logistic regression, for the outcome CVS, are demonstrated in Table 2. The univariate regression revealed that acute hydrocephalus after SAH, maximum recorded international normalized ratio (INR) and maximum recorded white cell count substantially increased the chances of CVS in post-embolization clinical course (ORs 5.000, 4.103 and 6.720, respectively). The influence of platelet count at nadir on CVS was statistically significant, but marginal (ORs between 1 and 1.01) (Table 2). Finally, the maximum recorded level of blood urea nitrogen was also significantly associated with CVS, with moderate influence (OR 1.285).

Characteristics of the study population

| Risk factors | Cerebrovascular spasm (n = 33) | No cerebrovascular spasm (n = 33) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 55.45 ± 12.13, 56 [14] | 52.55 ± 9.55, 54[17] | 0.336 |

| Age category (20–40/40–60/>60 years) | 4/16/13 (12.1%/48.5%/39.4%) | 5/21/7 (15.2%/63.6%/21.2%) | 0.274 |

| Gender (male/female, %/%) | 8/25 (24.2%/75.8%) | 10/23 (30.3%/69.7%) | 0.580 |

| Caffeine usage | 23 (69.7%) | 15 (45.5%) | 0.046* |

| Impaired vision | 1 (3%) | 6 (18.2%) | 0.046* |

| Mechanical ventilation | 17 (51.5%) | 8 (24.2%) | 0.022* |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 23 (69.7%) | 13 (39.4%) | 0.013* |

| Hydrocephalus | 11 (33.3%) | 3 (9.1%) | 0.016* |

| Aneurysm size (<5 mm/5–10 mm/11–25 mm) | 12/16/5 (36.4%/48.5%/15.2%) | 6/20/7 (18.2%/60.6%/21.2%)) | 0.249 |

| Aneurysm location (ACI/ACM/ACA/ACP/AB) | 15/3/10/2/3 (45.5%/9.1%/30.3%/6.1%/9.1%) | 10/7/13/2/1(30.3%/21.2%/39.4%/6.1%/3%) | 0.407 |

| Aneurysm height (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 6.718 ± 3.854, 5.52 [3.84] | 8.099 ± 4.342, 7.08 [4.21] | 0.099 |

| Aneurysm width (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 5.496 ± 3.36, 4.45 [3.26] | 6.63 ± 3.07, 6.29 [4.06] | 0.045* |

| Aneurysm neck (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 3.43 ± 2.705, 2.70 [1.28] | 2.902 ± 0.938, 2.78 [1.31] | 0.812 |

| GCS (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 11.15 ± 3.581, 13 [6] | 11.09 ± 3.146, 12 [5] | 0.640 |

| HHS (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 2.82 ± 1.185, 3 [2] | 3 ± 1.299, 3[2] | 0.605 |

| FS (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 3.45 ± 0.833, 4 [1] | 3.03 ± 0.847, 3 [2] | 0.029* |

| MRS (mean ± SD, median [IQR]) | 3.91 ± 1.569, 4 [4] | 3.03 ± 1.447, 2 [2] | 0.017* |

*Statistically significant.

Abbreviations: ACI – a. carotis interna, ACM – a. cerebri media, ACA – a. cerebri anterior, ACP – a. cerebri posterior, AB – a. basilaris, GCS – Glasgow Coma Scale, HHS – Hunt and Hesse scale, FS – Fisher scale, IQR – interquartile range, MRS – modified Rankin scale.

For the sake of clarity, the Mann–Whitney U test was done for continuous variables and the Chi-squared test for categorical variables.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with CVS (majority of the factors without significant influence were omitted for the sake of clarity)

| Risk factors | P value | Crude odds ratio | Confidence interval (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.280 | 1.025 | 0.980–1.073 |

| Gender | 0.581 | 0.736 | 0.248–2.186 |

| GCS score (≤8/>8) | 0.148 | 0.411 | 0.123–1.373 |

| Hydrocephalus (yes/no) | 0.023 | 5.000* | 1.245–20.076 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage (yes/no) | 0.015 | 3.538* | 1.277–9.805 |

| Mechanical ventilation (yes/no) | 0.025 | 3.320* | 1.163–9.477 |

| Maximum recorded CRP | 0.164 | 0.444 | 0.142–1.394 |

| Maximum recorded WBC | 0.001 | 6.720* | 2.080-21.708 |

| PLT at nadir (×109/L) | 0.029 | 1.007* | 1.001–1.012 |

| Maximum recorded INR | 0.008 | 4.103* | 1.455–11.567 |

| Proteins at nadir | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Maximum recorded urea (mmol/L) | 0.021 | 1.285* | 1.039–1.590 |

* – statistically significant.

CRP – C reactive protein; WBC – white blood cell count; PLT – platelet count; INR – international normalized ratio.

The results of multivariable logistic regression are shown in Table 3. The estimates of the coefficient of determination according to the Cox and Snell and Nagelkerke were 0.398 and 0.531, respectively, while the Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed that the observed rate of CVS matched the expected rate of the same phenomenon (χ2 = 2.503, p = 0.927). After adjustment, the following factors remained significantly associated with CVS: maximum recorded white cell count and INR. The strength of the association remained similar to that after univariate analysis, and the direction of the influence did not change (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with CVS

| Risk factors | P value | Adjusted odds ratio | Confidence interval (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLT at nadir (×109/L) | 0.099 | 1.007 | 0.999–1.014 |

| Maximum recorded urea (mmol/L) | 0.082 | 1.232 | 0.974–1.558 |

| Maximum recorded INR | 0.027 | 4.411* | 1.181–16.478 |

| Maximum recorded WBC | 0.004 | 8.376* | 2.009–34.921 |

* – statistically significant.

PLT – platelet count; INR – international normalized ratio; WBC – white blood cell count.

4 Discussion

Our study showed that the maximum recorded INR values in patients who were not receiving anticoagulant therapy and the maximum recorded WBC were strongly associated with cerebrovascular spasm, increasing its chances 4.4 and 8.4 times with an increase of each integer of the INR value and 1,000 white blood cells (WBCs), respectively.

Elevated INR values in patients not receiving anticoagulant therapy were recently linked to an increased risk of intracerebral aneurysm rupture, although the possible mechanism of action was not proposed [22]. A similar effect was not observed in patients on anticoagulant therapy, suggesting the protective role of oral anticoagulants independent of their main pharmacological effect (vitamin K antagonism) [23]. Although systemic inflammation creates a hypercoagulable state through activation of coagulation, decrease of endogenous anticoagulants in blood, and inhibition of fibrinolysis [24], INR is usually elevated due to the consumption of certain proteins involved in the coagulation cascade [25]. Elevated INR observed in our study may reflect a similar influence of systemic inflammation (C reactive protein was elevated in almost 72% of our patients) on the coagulation cascade. Inflammation was already associated with ASAH (elevated interleukin levels), and it was shown that its highest intensity was localized to the brain tissue, while changes in the blood are not that pronounced [26]. Increased levels of interleukin 6 were also found in patients with ASAH who developed CVS [27]. Therefore, elevated INR values are probably associated with intense inflammation of the brain tissue after the rupture of an aneurysm that will cause the release of a multitude of autacoids. At least some of the released autacoids may activate the receptors on smooth muscle cells and produce intense vasospasm, such as cysteinyl leukotrienes [28].

The elevated WBC count after the percutaneous intervention is also reflection of the inflammatory process in the brain tissue, and its association with CVS after SAH was not surprising. It was recently understood that a lot of vascular and neural changes after SAH were caused by inflammation accompanied by the activation of immune cells in brain parenchyma and blood [29]. There are many autacoids, hormones and neurotransmitters that may cause vasospasm, and some of them are released from platelets, such as serotonin, while the others could originate from other blood cells destroyed after SAH [30,31]; injured neurons also react with increased firing, so local concentrations of vasoactive catecholamines, endothelins or other substances may mount, causing intense and prolonged vasoconstriction.

Although mechanical ventilation, hydrocephalus and intraventricular hemorrhage were more frequent among patients in our study who developed cerebrovascular spasm, after adjustment for confounding factors their influence on spasm did not reach statistical significance. Intraventricular hemorrhage was previously linked with inflammation of the brain tissue in several animal studies, causing an upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, attracting WBCs and activating microglia [32]. On the other hand, hydrocephalus could be a consequence of intraventricular hemorrhage accompanying inflammation and edema. However, intraventricular hemorrhage probably was not the sole cause of neuroinflammation and release of mediators that produced vasoconstriction in our patients, which, together with a relatively small number of patients in the study, could explain why it was not among the significant risk factors after adjustment and multivariate analysis.

Although caffeine usage in our study was not significantly associated with CVS, some authors did find an association between them [33]. A probable explanation for caffeine-induced CVS is a pro-thrombotic state with decreased ability of blood vessels to dilate, since caffeine from caffeine-rich beverages or coffee increases platelet aggregation and alters endothelial function reducing the ability of the endothelium to mediate vascular relaxation. However, further research is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

The size of cerebral artery aneurysms was previously connected with the rate of cerebral artery vasospasm after SAH [14], but this is an indirect effect, since CVS is more frequent when the extent of subarachnoid bleeding is large. However, there are no studies finding an association between the size of aneurysms and rate of CVS after endovascular embolization. Our study also did not find such an association, but this could be a consequence of insufficient statistical power, implying the necessity for continuous research on this issue.

The limitation of our study was a relatively small sample size, which allowed simultaneous testing of only up to ten study variables in multivariate logistic regression, increasing the chances of statistical type 2 error. Our study was unicentric, which is an independent risk factor for introducing local practice bias in the interpretation of the results.

In conclusion, SAH after rupture of cerebral aneurysms creates an endocranial inflammatory state whose intensity is probably directly related to the occurrence of vasospasm and its adverse consequences. Whether pharmacological interference for neuroinflammation could be a useful strategy for the prevention of vasospasm remains to be decided by future studies of sufficient size.

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Muñoz-Guillén NM, León-López R, Túnez-Fiñana I, Cano-Sánchez A. From vasospasm to early brain injury: new frontiers in subarachnoid haemorrhage research. Neurologia. 2013;28(5):309–16. 10.1016/j.nrl.2011.10.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Athar MK, Levine JM. Treatment options for cerebral vasospasm in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(1):37–43. 10.1007/s13311-011-0098-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Dabus G, Nogueira RG. Current options for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm: a comprehensive review of the literature. Interv Neurol. 2013;2(1):30–51. 10.1159/000354755.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Etminan N, Vergouwen MD, Ilodigwe D, Macdonald RL. Effect of pharmaceutical treatment on vasospasm, delayed cerebral ischemia, and clinical outcome in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31(6):1443–51. 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Lin BF, Kuo CY, Wu ZF. Review of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage – focus on treatment, anesthesia, cerebral vasospasm prophylaxis, and therapy. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2014;52(2):77–84. 10.1016/j.aat.2014.04.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Naraoka M, Matsuda N, Shimamura N, Asano K, Ohkuma H. The role of arterioles and the microcirculation in the development of vasospasm after aneurysmal SAH. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:253746. 10.1155/2014/253746.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Miller BA, Turan N, Chau M, Pradilla G. Inflammation, vasospasm, and brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:384342. 10.1155/2014/384342.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Mijailovic M, Lukic S, Laudanovic D, Folic M, Folic N, Jankovic S. Effects of nimodipine on cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage treated by endovascular coiling. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2013;22(1):101–9.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Liu Y, Qiu H, Su J, Jiang W. Drug treatment of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage following aneurysms. Chinese Neurosurg J. 2016;2:4. 10.1186/s41016-016-0023-x.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Leclerc JL, Blackburn S, Neal D, Mendez NV, Wharton JA, Waters MF, et al. Haptoglobin phenotype predicts the development of focal and global cerebral vasospasm and may influence outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(4):1155–60. 10.1073/pnas.1412833112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Wilson TJ, Stetler Jr WR, Davis MC, Giles DA, Khan A, Chaudhary N, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage is associated with early hydrocephalus, symptomatic vasospasm, and poor outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2015;76(2):126–32. 10.1055/s-0034-1394189.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Inagawa T, Yahara K, Ohbayashi N. Risk factors associated with cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Med Chir. 2014;54(6):465–73. 10.2176/nmc.oa.2013-0169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Scherer M, Jung JO, Cordes J, Wessels L, Younsi A, Schönenberger S, et al. Association of cerebrospinal fluid volume with cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a retrospective volumetric analysis. Neurocrit Care. 2019. 10.1007/s12028-019-00878-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Inagawa T. Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2016;85:56–76. 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.08.052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Opancina V. Prevention and treatment of cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ration Ther. 2016;8(2):35–9. 10.5937/racter8-11415.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Juvela S, Siironen J, Kuhmonen J. Hyperglycemia, excess weight, and history of hypertension as risk factors for poor outcome and cerebral infarction after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):998–1003. 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.0998.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Shimoda K, Kamiya K, Kano T, Furuichi M, Yoshino A. Cerebral vasospasm and patient outcome after coiling or clipping for intracranial aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroendovasc Ther. 2019;13:443–8. 10.5797/jnet.oa.2019-0023.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Nunn A, Bath PM, Gray LJ. Analysis of the modified Rankin scale in randomised controlled trials of acute ischaemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke Res Treat. 2016;2016:9482876. 10.1155/2016/9482876.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Ghosh S, Dey S, Maltenfort M, Vibbert M, Urtecho J, Rincon F, et al. Impact of Hunt-Hess grade on the glycemic status of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients. Neurol India. 2012;60(3):283–7. 10.4103/0028-3886.98510.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Oliveira AM, Paiva WS, Figueiredo EG, Oliveira HA, Teixeira MJ. Fisher revised scale for assessment of prognosis in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69(6):910–3. 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000700012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Can A, Castro VM, Dligach D, Finan S, Yu S, Gainer V, et al. Elevated international normalized ratio is associated with ruptured aneurysms. Stroke. 2018;49(9):2046–52. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022412.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Tarlov N, Norbash AM, Nguyen TN. The safety of anticoagulation in patients with intracranial aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013;5(5):405–9. 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010359.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Cheng T, Mathews K, Abrams-Ogg A, Wood D. The link between inflammation and coagulation: influence on the interpretation of diagnostic laboratory tests. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2011;33(2):E4.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Lyons PG, Micek ST, Hampton N, Kollef MH. Sepsis-associated coagulopathy severity predicts hospital mortality. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(5):736–42. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002997.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Al-Tamimi YZ, Bhargava D, Orsi NM, Teraifi A, Cummings M, Ekbote UV, et al. Compartmentalisation of the inflammatory response following aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cytokine. 2019;123:154778. 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154778.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Chaudhry SR, Stoffel-Wagner B, Kinfe TM, Güresir E, Vatter H, Dietrich D, et al. Elevated systemic IL-6 levels in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is an unspecific marker for post-SAH complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2580. 10.3390/ijms18122580.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Haeggström JZ, Wetterholm A. Enzymes and receptors in the leukotriene cascade. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59(5):742–53. 10.1007/s00018-002-8463-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Coulibaly AP, Provencio JJ. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an overview of inflammation-induced cellular changes. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(2):436–45. 10.1007/s13311-019-00829-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] de Oliveira Manoel AL, Macdonald RL. Neuroinflammation as a Target for Intervention in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2018;9:292. 10.3389/fneur.2018.00292.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Lucke-Wold BP, Logsdon AF, Manoranjan B, Turner RC, McConnell E, Vates GE, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and neuroinflammation: a comprehensive review. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(4):497. 10.3390/ijms17040497.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Garton T, Hua Y, Xiang J, Xi G, Keep RF. Challenges for intraventricular hemorrhage research and emerging therapeutic targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21(12):1111–22. 10.1080/14728222.2017.1397628.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Grant RA, Cord BJ, Kuzomunhu L, Sheth K, Gilmore E, Matouk CC. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and severe, catheter-induced vasospasm associated with excessive consumption of a caffeinated energy drink. Interv Neuroradiol. 2016;22(6):674–8. 10.1177/1591019916660868.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Valentina Opancina et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway