Abstract

Melanoma is one of the most highly metastatic, aggressive and fatal malignant tumors in skin cancer. This study employs bioinformatics to identify key microRNAs and target genes (TGs) of plasma extracellular vesicles (pEVs) and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma. The gene expression microarray dataset (GSE100508) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differential analysis of miRNAs in pEVs was performed to compare melanoma samples and healthy samples. Then, TGs of the differential miRNAs (DE-miRNAs) in melanoma were selected, and differential genes were analyzed by bioinformatics (including Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway enrichment, protein–protein interaction network and prognostic analysis). A total of 55 DE-miRNAs were found, and 3,083 and 1,351 candidate TGs were diagnostically correlated with the top ten upregulated DE-miRNAs and all downregulated DE-miRNAs, respectively. Prognostic analysis results showed that high expression levels of hsa-miR-550a-3p, CDK2 and POLR2A and low expression levels of hsa-miR-150-5p in melanoma patients were associated with significantly reduced overall survival. In conclusion, bioinformatics analysis identified key miRNAs and TGs in pEVs of melanoma, which may represent potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis and treatment of this cancer.

1 Introduction

Melanoma is one of the most highly metastatic, aggressive and fatal malignant tumors in skin cancer [1]. Melanoma is often systemic and asymptomatic in patients and has become the tumor with the highest rate of brain metastases in adult solid tumors [2]. Although melanoma is rare, it has been reported that the incidence of skin melanoma is increasing worldwide, which has become a health problem that warrants further study [3,4]. The current treatment of cutaneous melanoma is surgical resection, and other treatments include radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy [3,5]. Unfortunately, the treatment of skin melanoma is not satisfactory at present, and the prognosis of patients after treatment is not good [5]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify more effective molecular markers for the early recognition and treatment of cutaneous melanoma to improve the prognosis of patients.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that are generally 18–25 nt in length and are embedded in independent noncoding RNA or introns that encode proteins. Mature miRNA exerts its biological function by combining with ribosomes, similar to the RNA-induced silencing complex, to form miRNA and recognize target genes (TGs). The target of miRNA is polymorphic; that is, a miRNA can have multiple TGs or multiple miRNAs have the same TG. In addition, the change in expression during the formation of miRNA may have a carcinogenic or antitumor effect on the tumor. Therefore, miRNAs may regulate the occurrence and development of tumors by identifying their specific TGs. In recent years, plasma extracellular vesicles (pEVs) have received extensive attention as a means of communication between cells and organs [6]. A large number of studies have found that pEVs are involved in intercellular communication and various physiological and pathological processes [7,8,9]. Studies have shown that EVs extracted from tumor cells have become one of the key factors in the development of malignant tumors by regulating the involvement of target cells in tumor growth, metastasis and immune response [10,11,12]. In addition, accumulating evidence has indicated that miRNAs, as an important component of EVs, play an important role in the development of human malignancies [12]. Therefore, exploring specific miRNAs in pEVs of melanoma patients may be potential molecular targets for the early diagnosis or treatment of melanoma patients.

To date, few studies have investigated the molecular mechanism of miRNAs in the pEVs of patients with melanoma. Thus, in this study, bioinformatics technology was used to identify differential miRNAs (DE-miRNAs) and TGs related to the diagnosis and prognosis of pEVs in patients with melanoma. Subsequently, Gene Ontology (GO) annotation, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis, protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and survival analysis were used to screen out the DE-miRNAs and target the genes most relevant to the diagnosis and prognosis of malignant melanoma, which may become potential targets for the early diagnosis, treatment and prognosis analysis of malignant melanoma patients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Microarray data of pEVs in cases of melanoma

The gene expression microarray dataset (GSE100508) was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). The dataset was based on the GPL22079 platform (Agilent-031181 Unrestricted Human miRNA V16.0 Microarray), which included samples from 14 healthy controls, 14 patients with melanoma, 15 patients with a high risk of recurrence and 11 with a low risk of recurrence. The miRNA expression data of pEVs in melanoma patients and healthy controls were downloaded and used for this study.

2.2 Differential analysis of miRNA expression in pEVs

The series and platform data were converted and loaded through the R language software and the annotation package. Then, the data were standardized by the limma R package’s array function (http://www.bioconductor.org/) [13]. The differential analysis of miRNAs in pEVs between melanoma samples and healthy samples was performed by using the GEO2R analysis tool. An miRNA with a statistical significance P-value of <0.05 and a base-2 logarithm of fold change (log FC) value of greater than ±1 was defined as DE-miRNA. The dataset was visualized with Morpheus online tools (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus/) and OriginPro (version 2016), and the integrated DE-miRNA lists of upregulated and downregulated were saved for subsequent analysis [14].

2.3 Selection of TGs of DE-miRNAs in melanoma

miRTarBase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/index.php), an experimentally validated miRNA–target interaction database, was used to screen TGs of DE-miRNAs [15]. This study selected the top ten upregulated miRNAs and all downregulated miRNAs. Subsequently, miRTarBase was used to retrieve and screen for TGs associated with DE-miRNAs in melanoma.

2.4 GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of TGs

Protein analysis through evolutionary relationship (PANTHER) systems (http://pantherdb.org/) classifies genes or proteins based on their molecular functions (MFs), biological processes (BPs) and pathways to facilitate high-throughput functional analysis [16]. In this study, the PANTHER classification system was used for GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the integrated TGs. The GO annotation analysis of TGs involved the BP, cell component (CC) and MF of the genes. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

2.5 Integration analysis of the TG interaction network

The predicted TGs of the top five most upregulated and all downregulated DE-miRNAs were selected, and the PPI networks were analyzed with the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) [17]. Then, Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) was used to visualize the PPI networks. Gene networks can be used to study the relationship between genetic factors of disease, in which highly connected nodes are defined as hub genes. The degree analysis method in the CytoHubba plug-in was used to calculate the grade nodes in the PPI network, and the top 25 hub genes were selected and visualized by Cytoscape [18]. The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) was used to identify the genes with the largest mutation and variation in melanoma [19]. Subsequently, the bioinformatics prediction miRNA Data Integration Portal (mirDIP) online database (http://ophid.utoronto.ca/mirDIP/) was used to highlight the relative strength of each COSMIC gene and hub gene with DE-miRNAs. The mirDIP database integrates 30 TG databases and uses algorithms to score miRNA–TG interactions with confidence [20]. The confidence class was divided into four levels: very high, high, medium and low. Based on the level of miRNA–TG interaction, the DE-miRNAs most correlated with melanoma could be screened out.

2.6 Prognostic analysis associated with hub genes for patients with melanoma

UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) and OncoLnc (http://www.oncolnc.org/) are interactive webs that provide in-depth analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) gene expression data [21]. In this study, the top five DE-miRNAs, the COSMIC genes and the top five hub genes most closely related to DE-miRNAs were selected. Then, survival analysis was performed by UALCAN and OncoLnc to screen out the hub genes most relevant to the prognosis of patients with melanoma. A P-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of DE-miRNAs and TGs in pEVs of melanoma

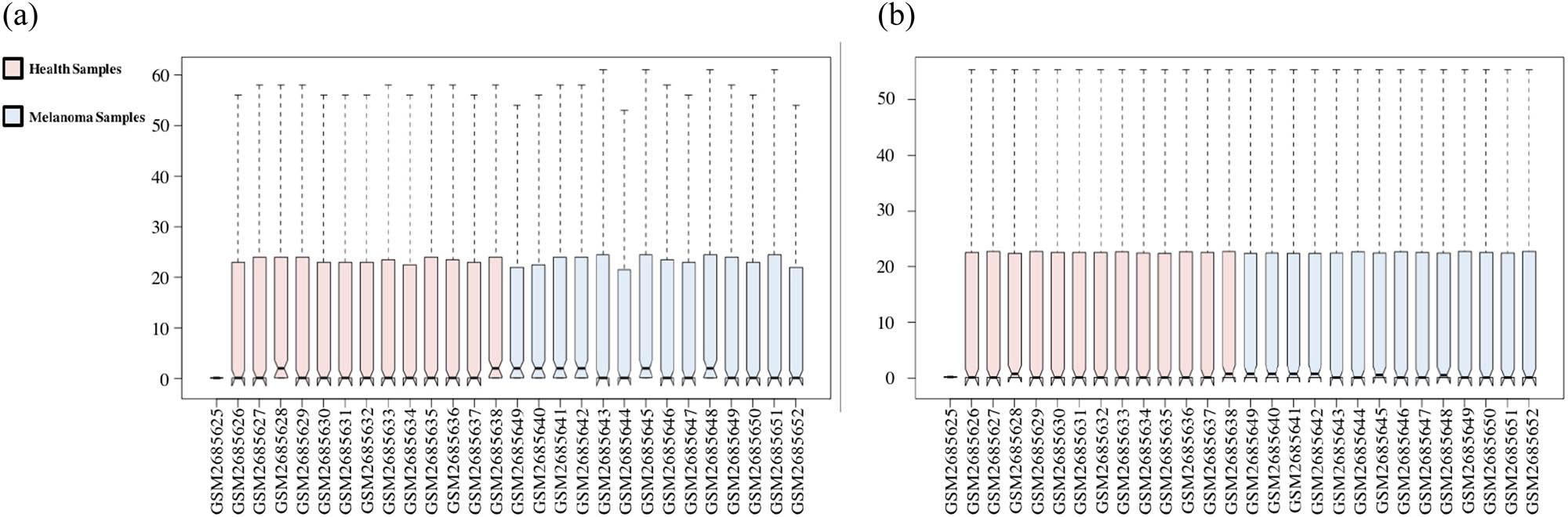

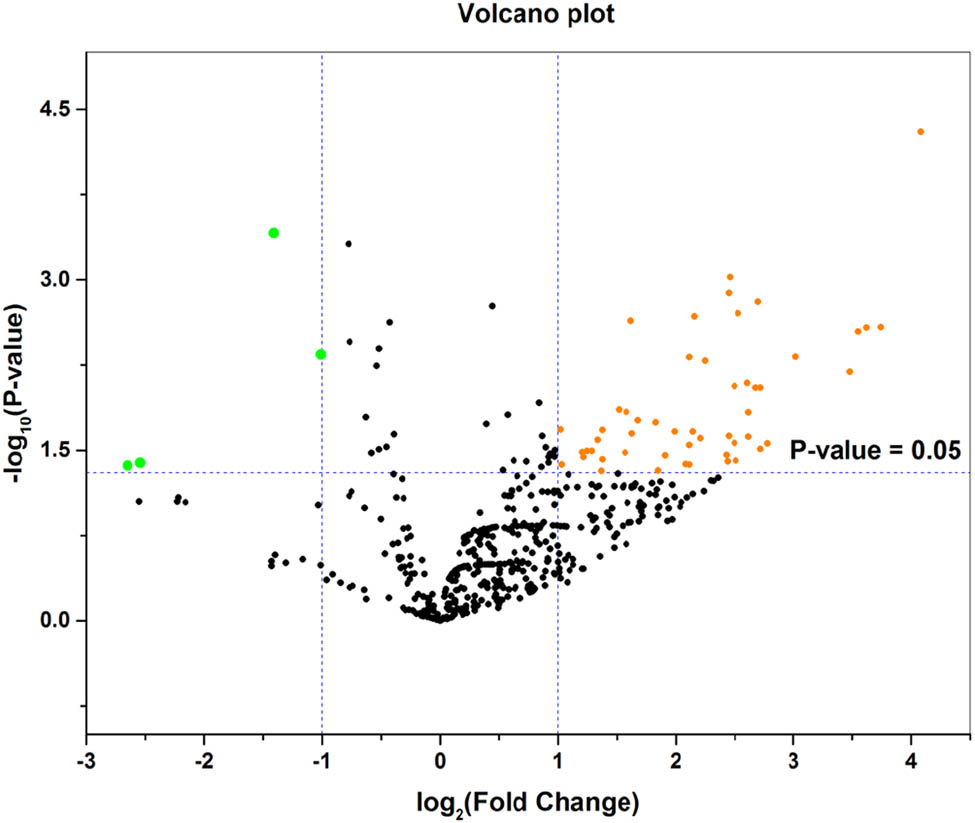

The downloaded gene expression microarray dataset (GSE100508) included 14 healthy controls (GSM2685625–GSM2685638) and 14 melanoma patients (GSM2685639–GSM2685652). The data were normalized using the limma R package, and the miRNA expression in pEVs was compared between the two groups (Figure 1). The screening criteria were set to a P-value of <0.05 and |log FC| > 1, and the results showed a total of 55 DE-miRNAs (51 upregulated miRNAs and 4 downregulated miRNAs) and displayed by a heat map (Figure 2). The top ten upregulated miRNAs and all downregulated miRNAs were selected and are listed in Table 1, and volcano maps were used to show the distribution of all DE-miRNAs (Figure 3). Upregulated miRNAs were sorted according to the P-value, and hsa-miR-765, hsa-miR-362-3p, hsa-miR-550a-3p, hsa-miR-3907 and hsa-miR-500a-3p were the top five upregulated DE-miRNAs. hsa-miR-1238, hsa-miR-1228-3p, hsa-miR-10a-5p and hsa-miR-150-5p were the downregulated DE-miRNAs. Retrieving the miRTarBase database, a total of 3,083 candidate TGs were diagnostically correlated with the top ten upregulated DE-miRNAs, and 1,351 candidate TGs were diagnostically associated with the downregulated DE-miRNAs.

The GSE100508 microarray dataset obtained from the GEO database. (a) The microarray dataset before normalization. (b) The microarray dataset after normalization.

Differential analysis of the miRNA expression in pEVs of melanoma. (a) Heat map of DE-miRNAs in 14 cases of melanoma and 14 health controls. (b) The details of the 28 cases.

Top ten upregulated and all downregulated DE-miRNAs in pEVs between melanoma and health control

| ID | Adj. P-value | P-value | T | B | log FC | Regulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-765 | 0.0272 | 0.0000498 | 4.81 | 1.9252 | 4.08 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-362-3p | 0.1107 | 0.0009439 | 3.71 | −0.6452 | 2.46 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-550a-3p | 0.1107 | 0.00131 | 3.58 | −0.9311 | 2.45 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-3907 | 0.1107 | 0.0015673 | 3.51 | −1.0873 | 2.7 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-500a-3p | 0.1107 | 0.0019777 | 3.42 | −1.2896 | 2.53 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-199b-5p | 0.1107 | 0.0021114 | 3.4 | −1.3465 | 2.16 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-15b-3p | 0.1107 | 0.0022978 | 3.36 | −1.42 | 1.62 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-34a-5p | 0.1107 | 0.0026186 | 3.31 | −1.5335 | 3.74 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-4284 | 0.1107 | 0.0026311 | 3.31 | −1.5376 | 3.62 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-215 | 0.1118 | 0.0028611 | 3.28 | −1.6103 | 3.55 | Upregulated |

| hsa-miR-1238 | 0.3117 | 0.0433103 | −2.12 | −3.9149 | −2.65 | Downregulated |

| hsa-miR-1228-3p | 0.3087 | 0.0408028 | −2.15 | −3.8662 | −2.54 | Downregulated |

| hsa-miR-10a-5p | 0.1384 | 0.0045602 | −3.09 | −2.0136 | −1.01 | Downregulated |

| hsa-miR-150-5p | 0.0881 | 0.0003886 | −4.04 | 0.1301 | −1.41 | Downregulated |

Volcano plot of the DE-miRNAs. The black points represent genes with no significant difference. The orange points represent upregulated genes screened based on the |log FC| > 1.0 and P-value <0.05. The green points represent downregulated genes screened based on the |log FC| > 1.0 and P-value <0.05.

3.2 GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of TGs

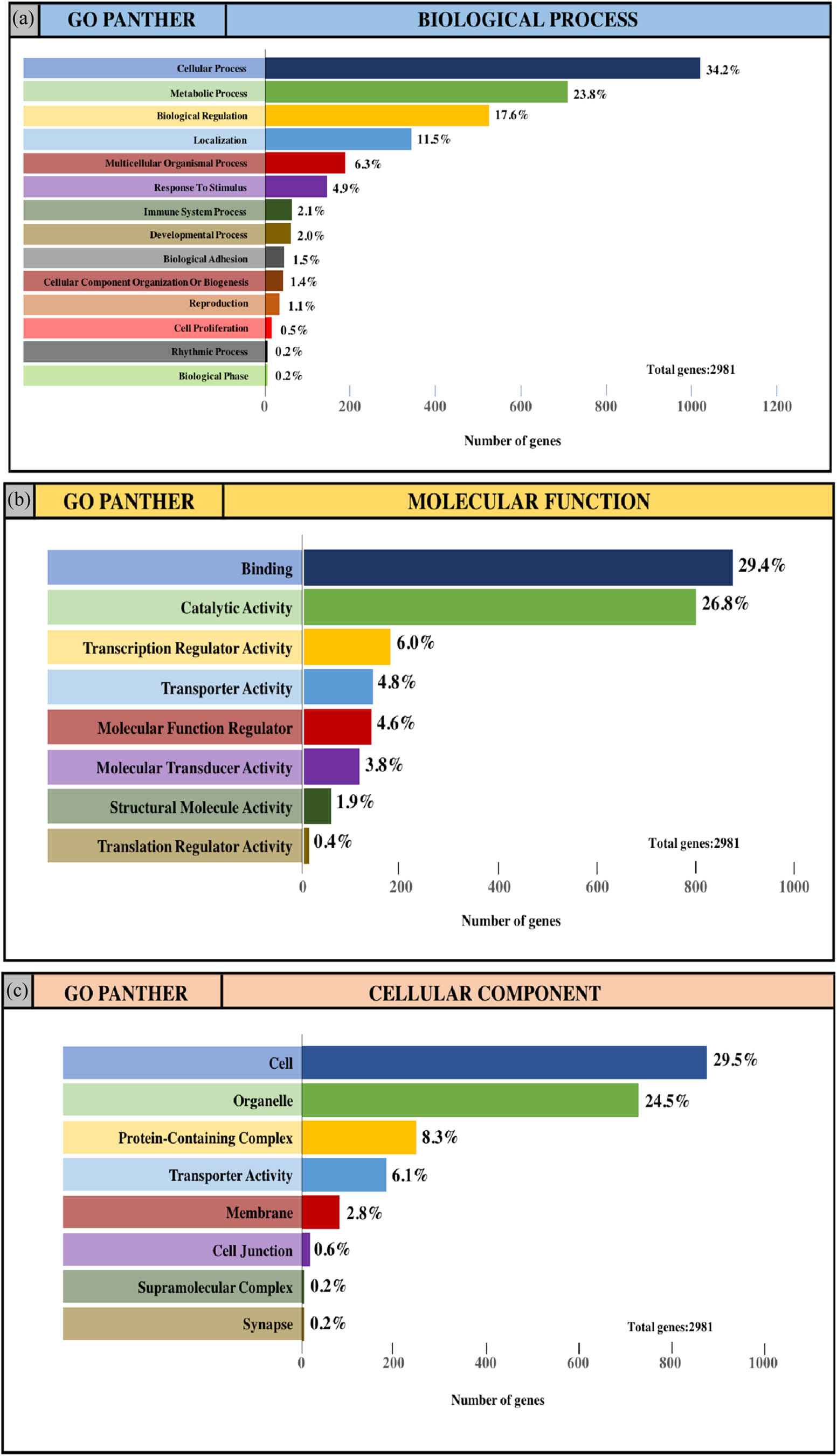

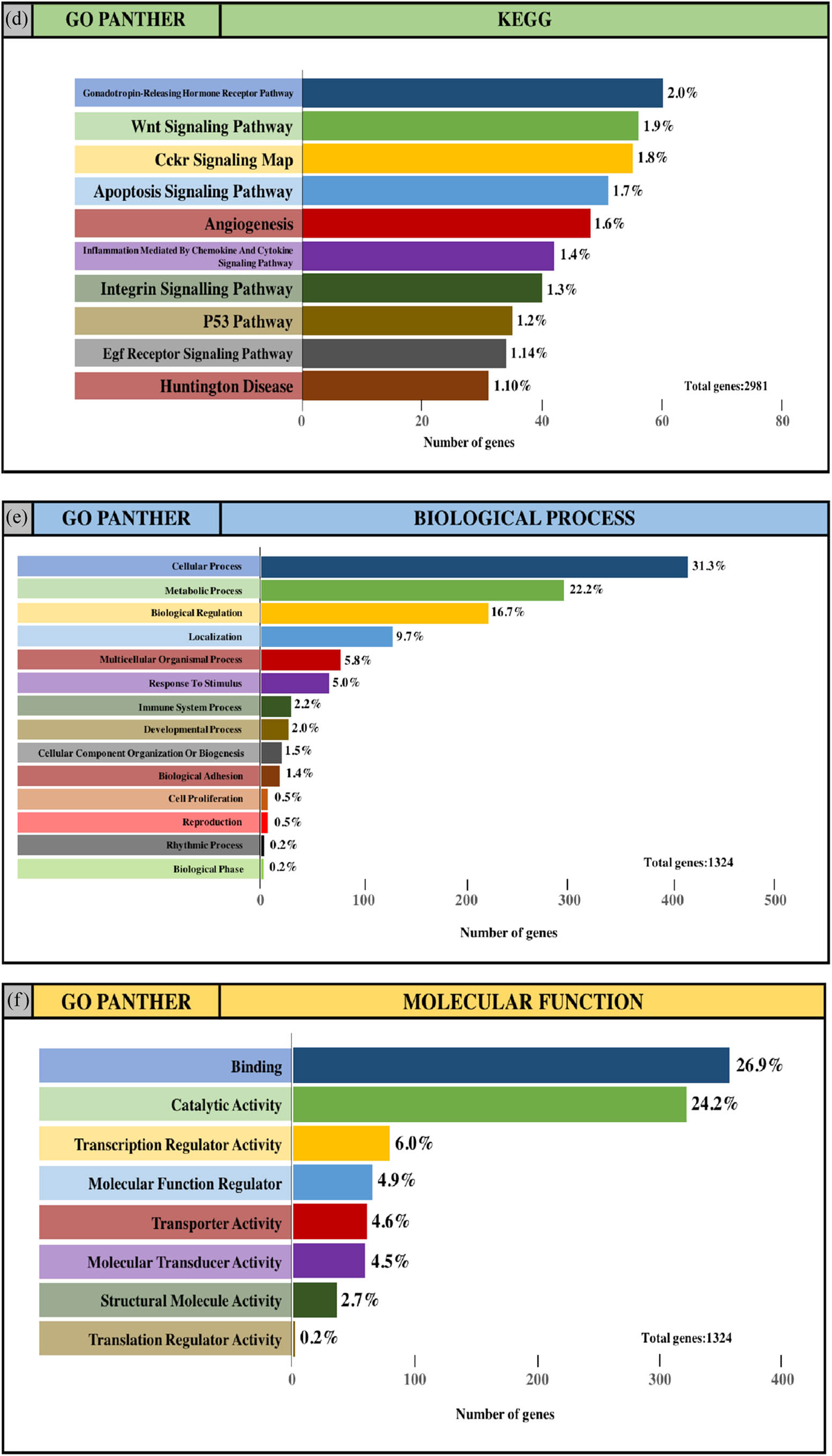

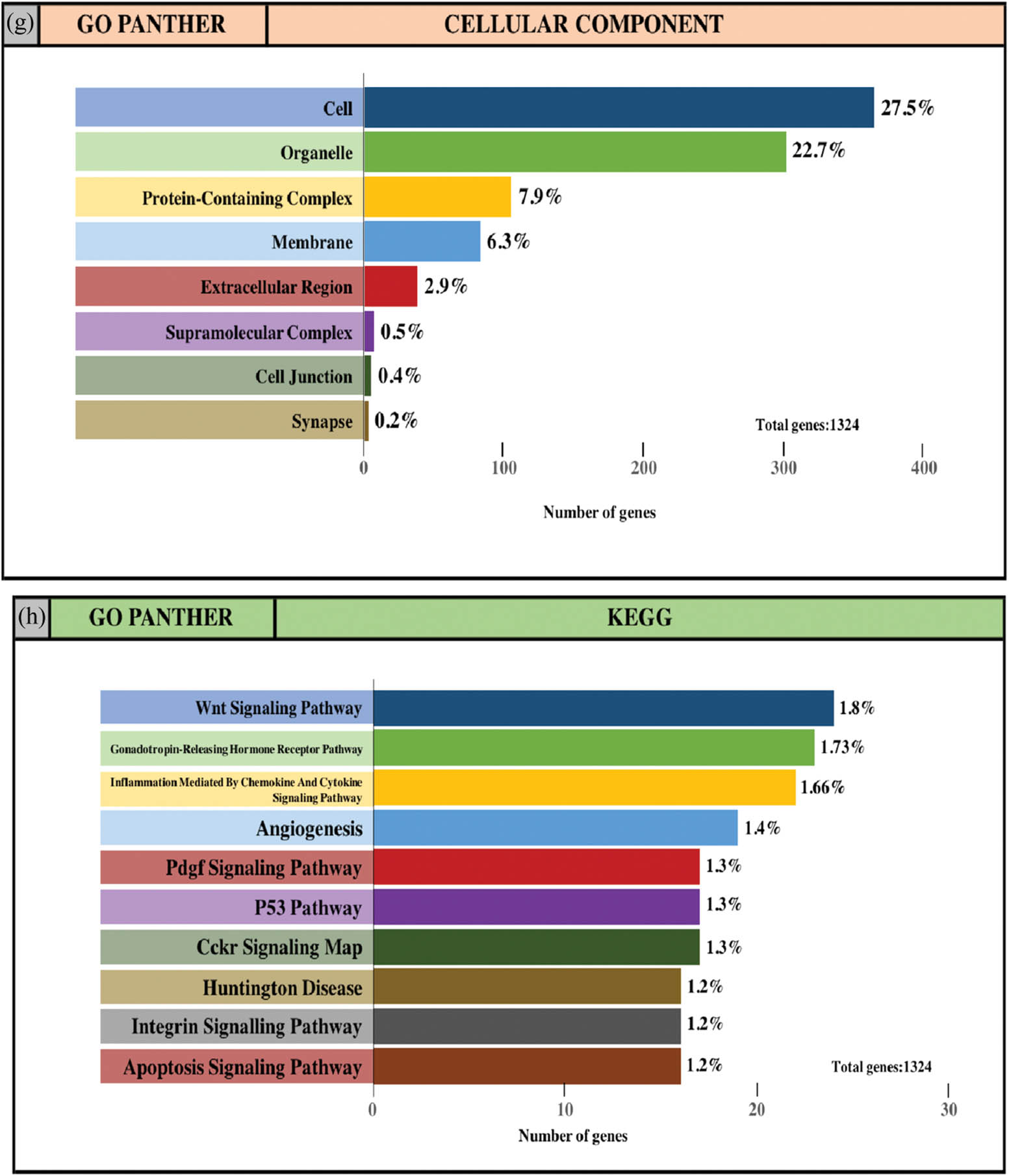

The integrated TGs were analyzed using the PANTHER classification system for GO annotation and KEGG pathway analysis to further reveal the enrichment of TGs in MF, BP, CC and pathways. For the BP (Figure 4a and e), most of the TGs were involved in the regulation of cellular process (34.2% and 31.3%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively), metabolic process (23.8% and 22.2%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively) and biological regulation (17.6% and 16.7%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively). For MF (Figure 4b and f), TGs were mainly involved in binding (29.4% and 26.9%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively) and catalytic activity (26.8% and 24.2%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively). With regard to the cellular component (Figure 4c and g), the majority of the TGs were components of the cell (29.5% and 27.5%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively) and organelles (24.5% and 22.7%, upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively). Subsequently, the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results showed that the TGs were most significantly enriched in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway and the Wnt signaling pathway (Figure 4d and h).

GO and pathway enrichment analysis of the predicted TG of DE-miRNAs through the PANTHER database. (a and e) GO PANTHER’s analysis on the category of “biological process” of the predicted TG of upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively. (b and f) GO PANTHER’s analysis on the category of “molecular function” of the predicted TG of upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively. (c and g) GO PANTHER’s analysis on the category of “cellular component” of the predicted TG of upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively. (d and h) GO PANTHER’s analysis on the category of “KEGG” of the predicted TG of upregulated miRNAs and downregulated miRNAs, respectively.

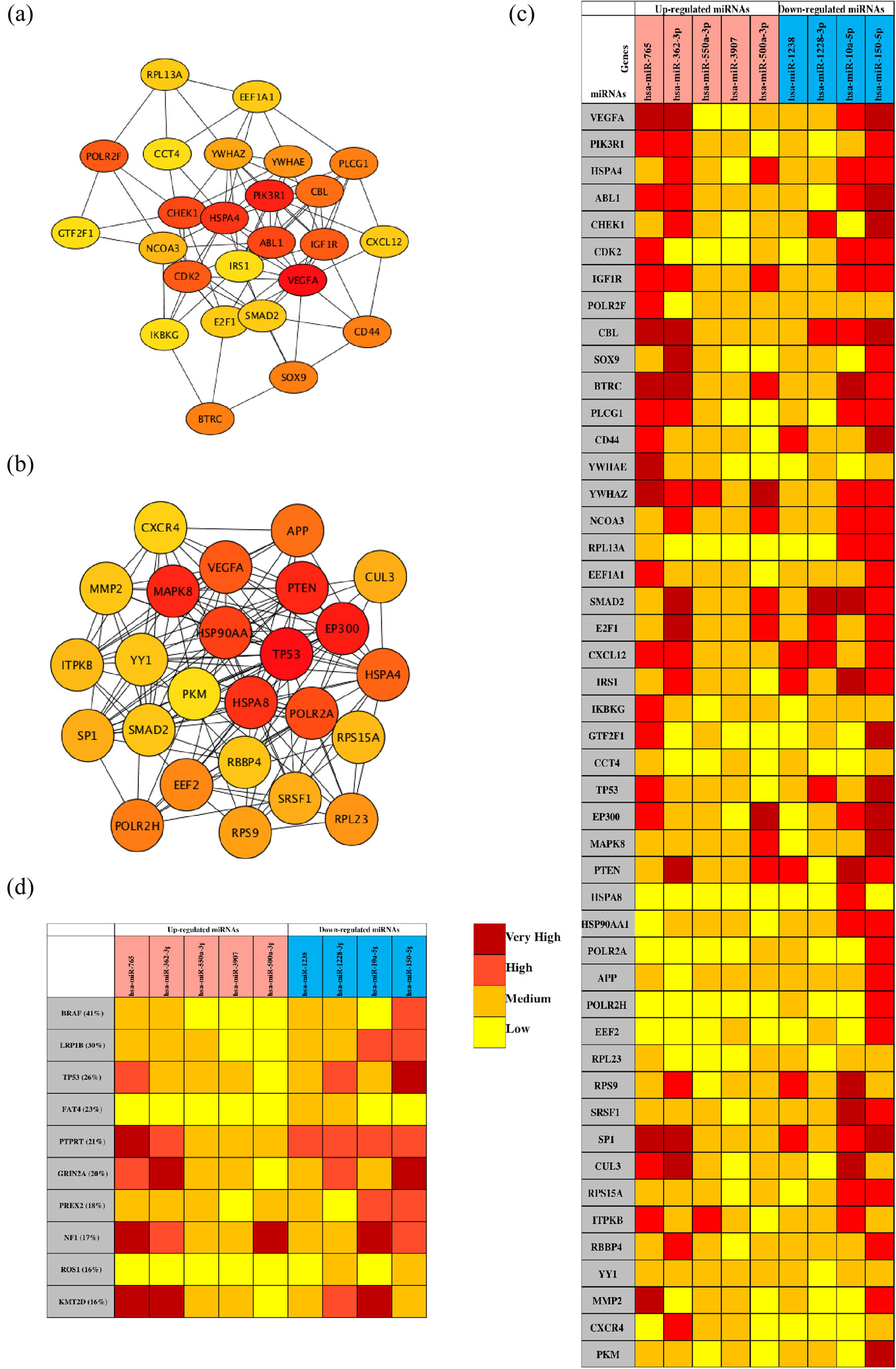

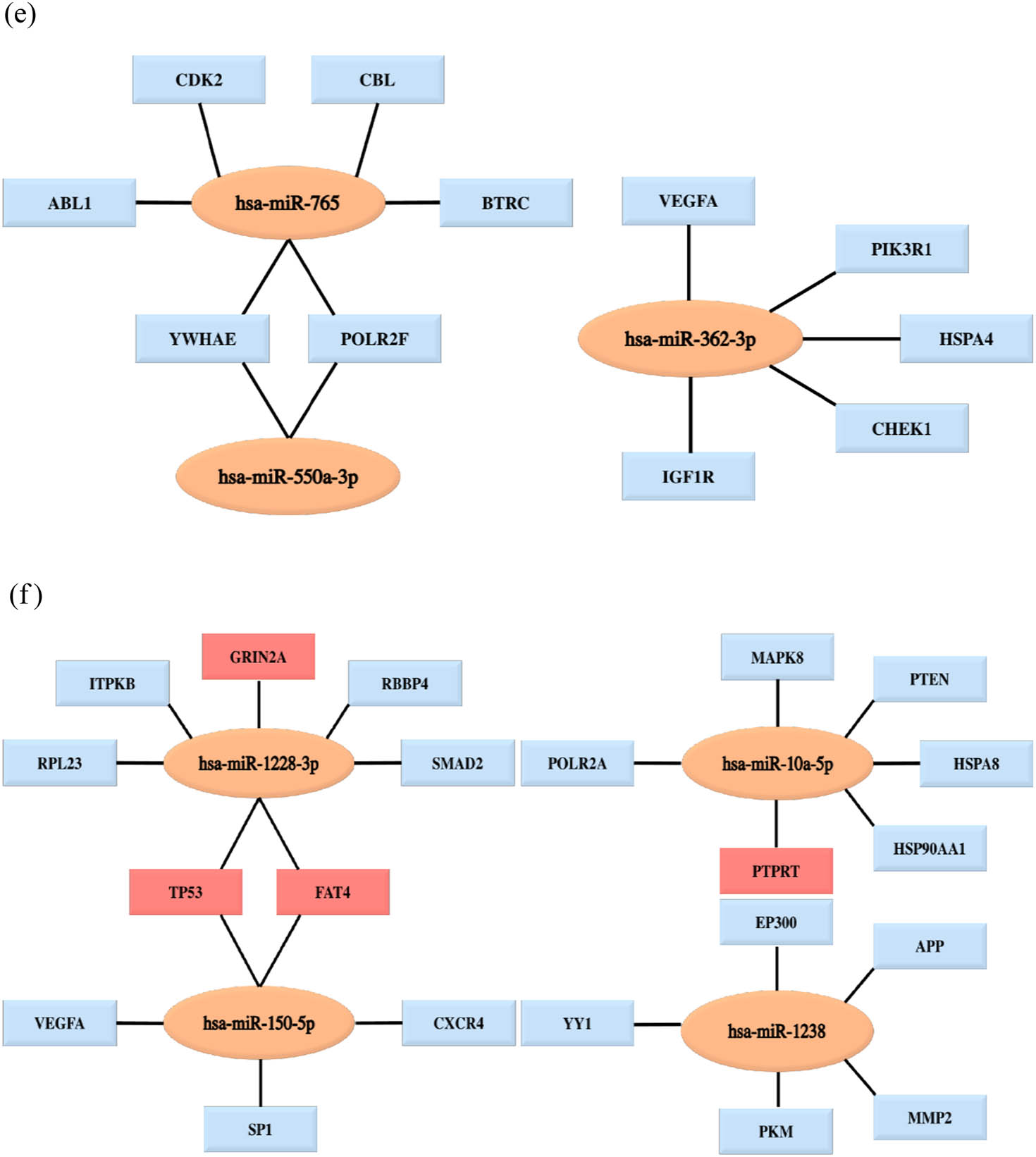

3.3 Analysis of the PPI network and the miRNA target network

The PPI network analysis is important for understanding the mechanisms of biosignal and energy metabolism and the functional linkages between proteins under specific physiological conditions of disease. In this study, we used the STRING database to perform PPI network analysis on the predicted TGs of the top five most upregulated and all downregulated DE-miRNAs. Then, the hub genes with the highest degree of the first 25 nodes were obtained by the Degree algorithm (Table 2) and visualized with Cytoscape software (Figure 5a and b). Regarding the upregulated miRNAs, VEGFA, PIK3R1, HSPA4, ABL1 and CHEK1 were the top five hub genes, while TP53, EP300, MAPK8, PTEN and HSPA8 were the top five hub genes for the downregulated miRNAs.

Hub genes in the PPI networks

| Upregulated miRNAs | Downregulated miRNAs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Degree | Gene | Degree |

| VEGFA | 64 | TP53 | 156 |

| PIK3R1 | 42 | EP300 | 85 |

| HSPA4 | 39 | MAPK8 | 80 |

| ABL1 | 31 | PTEN | 80 |

| CHEK1 | 31 | HSPA8 | 78 |

| CDK2 | 30 | HSP90AA1 | 77 |

| IGF1R | 30 | POLR2A | 70 |

| POLR2F | 30 | VEGFA | 67 |

| CBL | 29 | HSPA4 | 65 |

| SOX9 | 28 | APP | 64 |

| BTRC | 28 | POLR2H | 50 |

| PLCG1 | 28 | EEF2 | 48 |

| CD44 | 28 | RPL23 | 47 |

| YWHAE | 26 | RPS9 | 46 |

| YWHAZ | 25 | SRSF1 | 45 |

| NCOA3 | 24 | SP1 | 45 |

| RPL13A | 22 | CUL3 | 45 |

| EEF1A1 | 22 | RPS15A | 42 |

| SMAD2 | 22 | ITPKB | 42 |

| E2F1 | 22 | RBBP4 | 41 |

| CXCL12 | 22 | YY1 | 41 |

| IRS1 | 21 | SMAD2 | 41 |

| IKBKG | 21 | MMP2 | 41 |

| GTF2F1 | 21 | CXCR4 | 40 |

| CCT4 | 21 | PKM | 39 |

Analysis of the PPI network and the miRNA target network. (a) The mapped networks for the top 25 hub genes for upregulated miRNAs. (b) The mapped networks for the top 25 hub genes for downregulated miRNAs. (c) The mirDIP analysis of interaction levels between hub genes and DE-miRNAs. (d) The mirDIP analysis of interaction levels between the main mutated genes and DE-miRNAs. (e) The mapped networks for upregulated miRNAs and hub genes. (f) The mapped networks for downregulated miRNAs and hub genes. The red gene indicates that it is both a mutant gene and a core gene.

Ten mutated genes most related to melanoma were retrieved from the COSMIC database. The mutated genes were BRAF (41%), LRP1B (30%), TP53 (26%), FAT4 (23%), PTPRT (21%), GRIN2A (20%), PREX2 (18%), NF1 (17%), ROS1 (16%) and KMT2D (16%). Then, the mirDIP online database was used to analyze the interaction levels of DE-miRNA-mutant genes and DE-miRNA-hub genes, and the associated heat maps were used to display the interaction levels (Figure 5c and d). Regarding the interaction levels of DE-miRNAs-hub genes, the upregulated hsa-miR-765, hsa-miR-362-3p and hsa-miR-500a-3p and the downregulated hsa-miR-10a-5p and hsa-miR-150-5p were most relevant to hub genes. Regarding the interaction levels of DE-miRNA-mutant genes, the upregulated hsa-miR-765 and hsa-miR-362-3p and the downregulated hsa-miR-10a-5p, hsa-miR-150-5p and hsa-miR-122-3p were determined to be strongly correlated with mutant genes. Subsequently, we compared the TGs of the aforementioned DE-miRNAs with the hub genes and the mutated genes. The top five genes with the highest degree were selected and plotted on the DE-miRNA-gene association map (Figure 5e and f). The results showed that the upregulated hsa-miR-765 and hsa-miR-500a-3p could jointly regulate the YWHAE and POLAR2F genes, and the downregulated hsa-miR-1228-3p and hsa-miR-150-5p could jointly regulate the TP53 and FAT4 genes. In addition, notably, the mutant genes did not overlap with the hub genes of the upregulated miRNAs, while the TP53 and FAT4 genes were both hub genes and mutant genes for the downregulated hsa-miR-1228-3p and hsa-miR-150-5p.

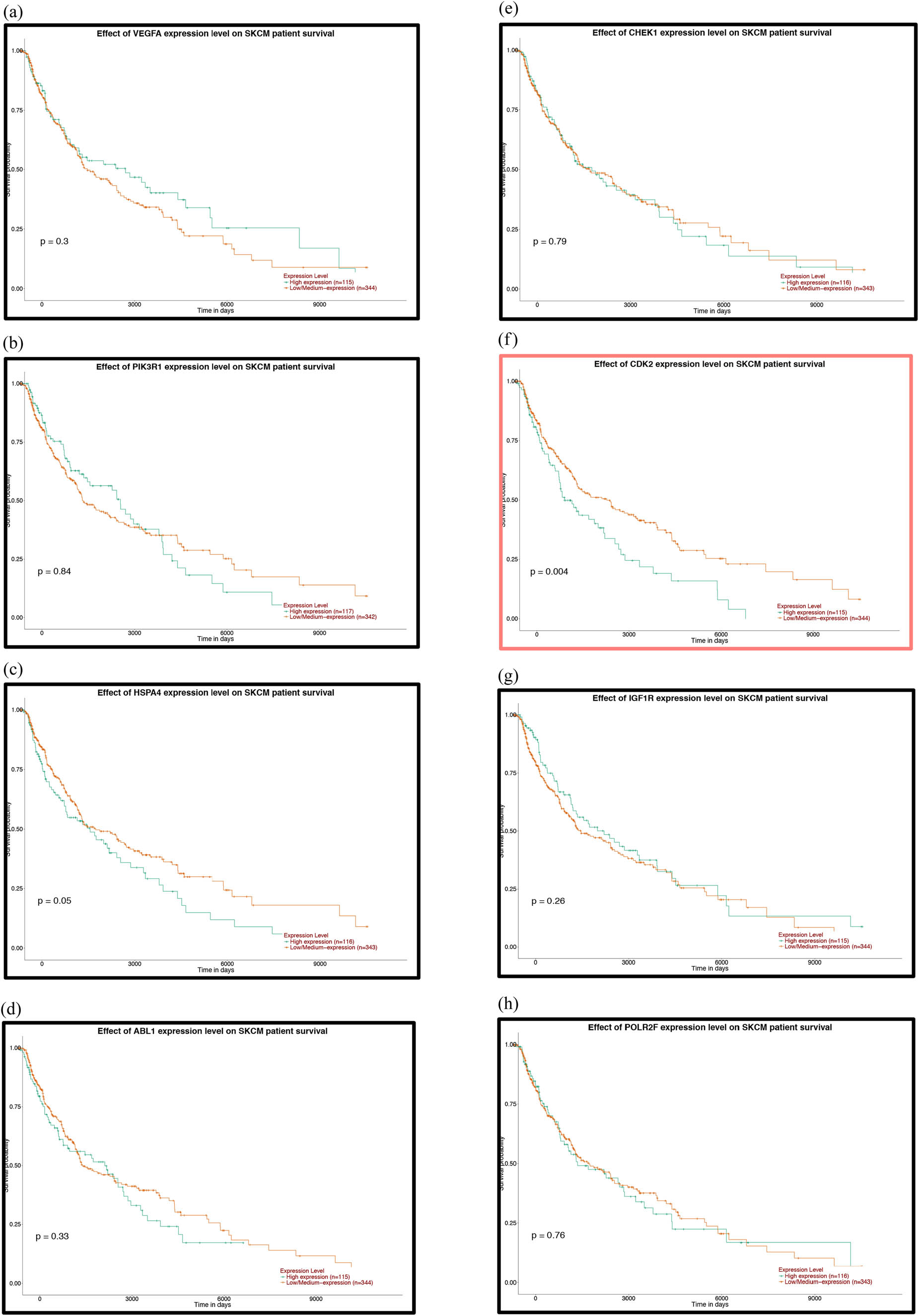

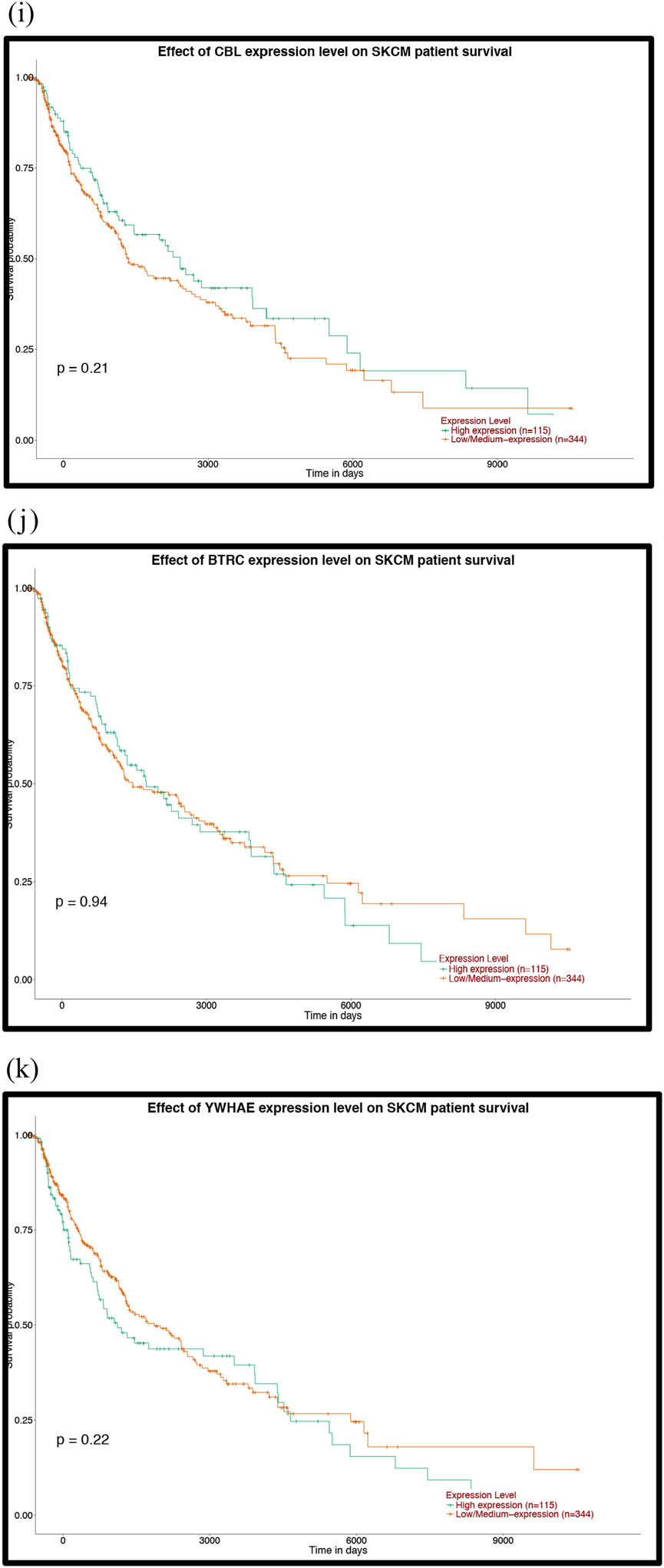

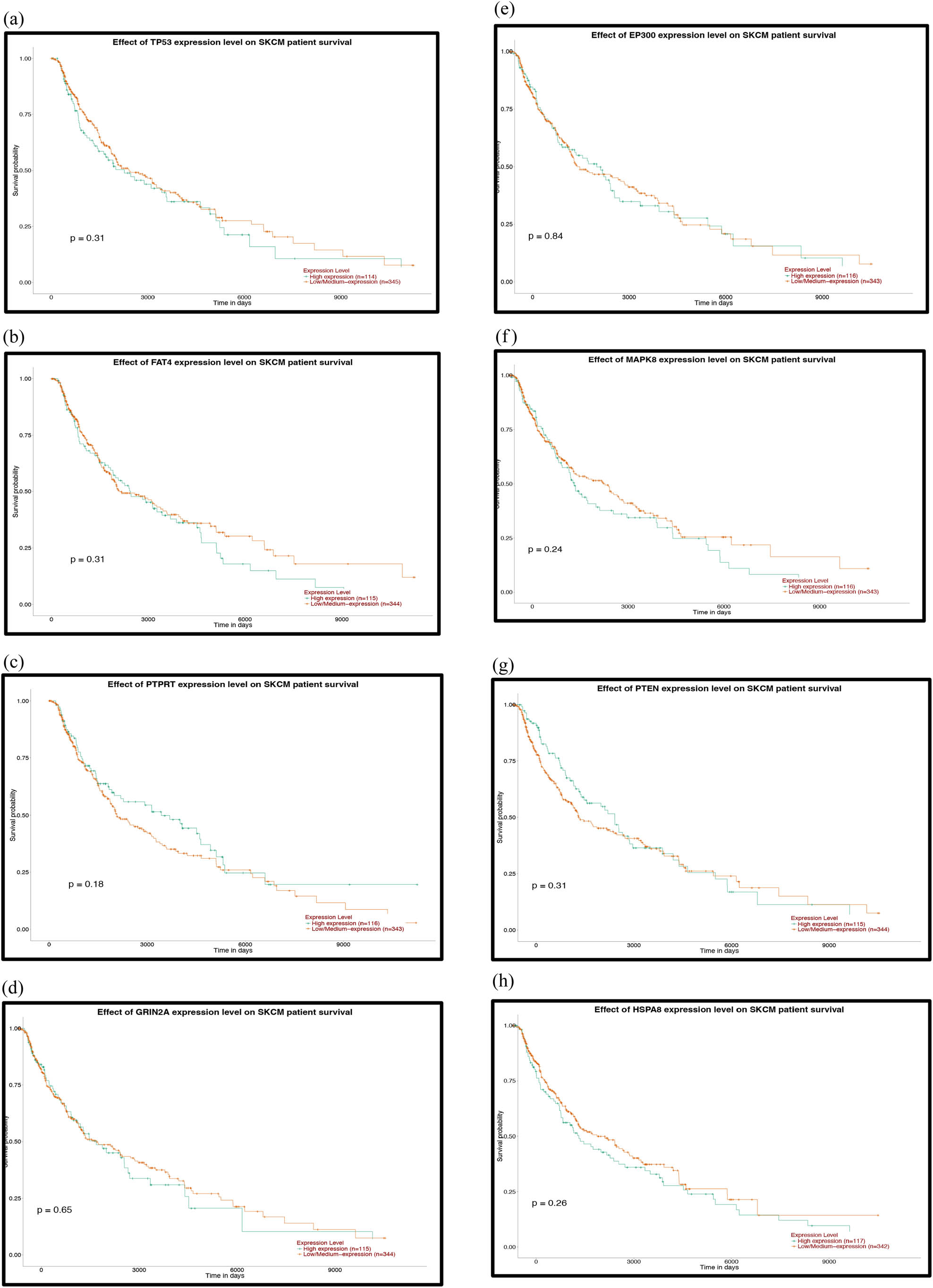

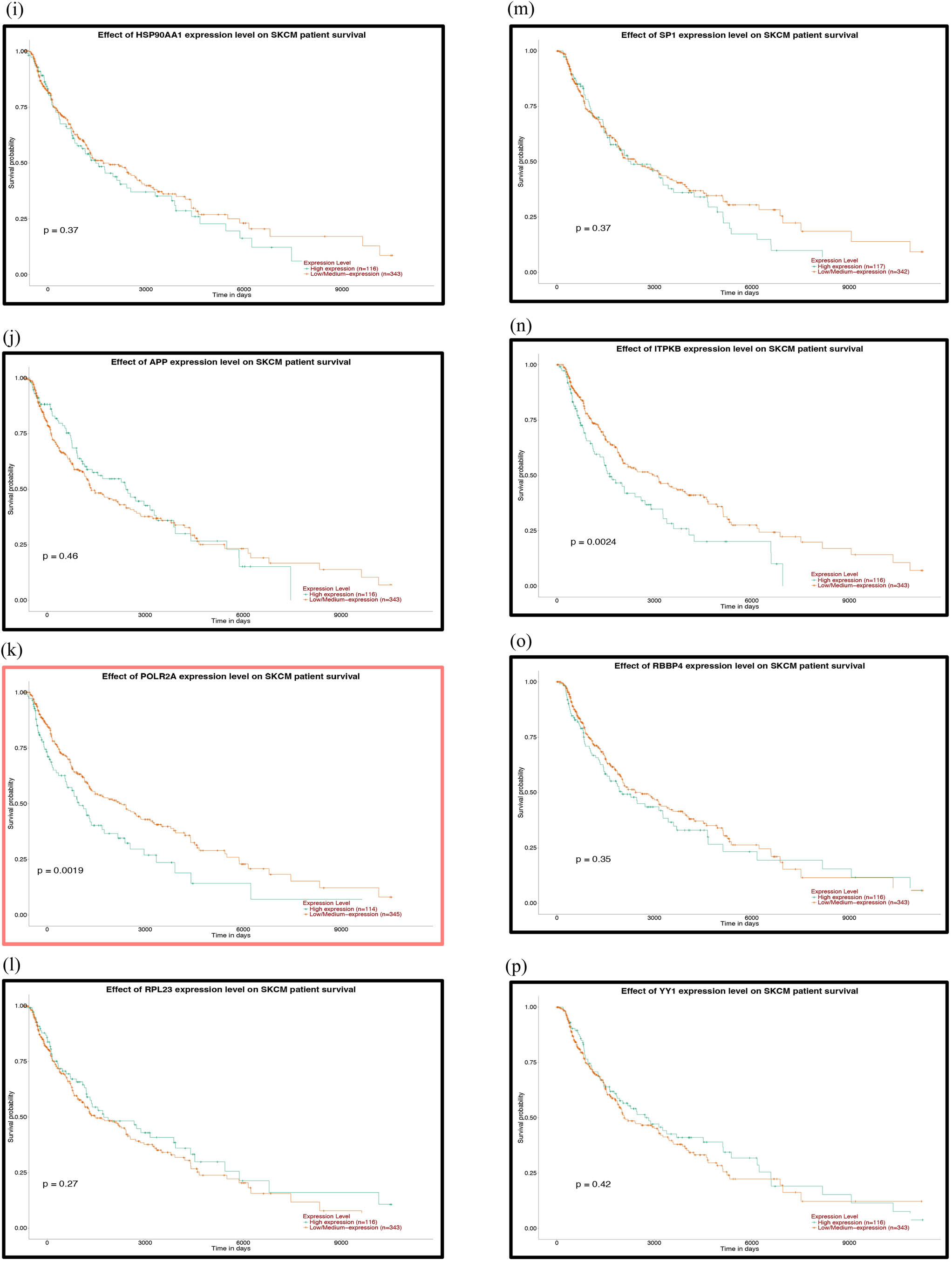

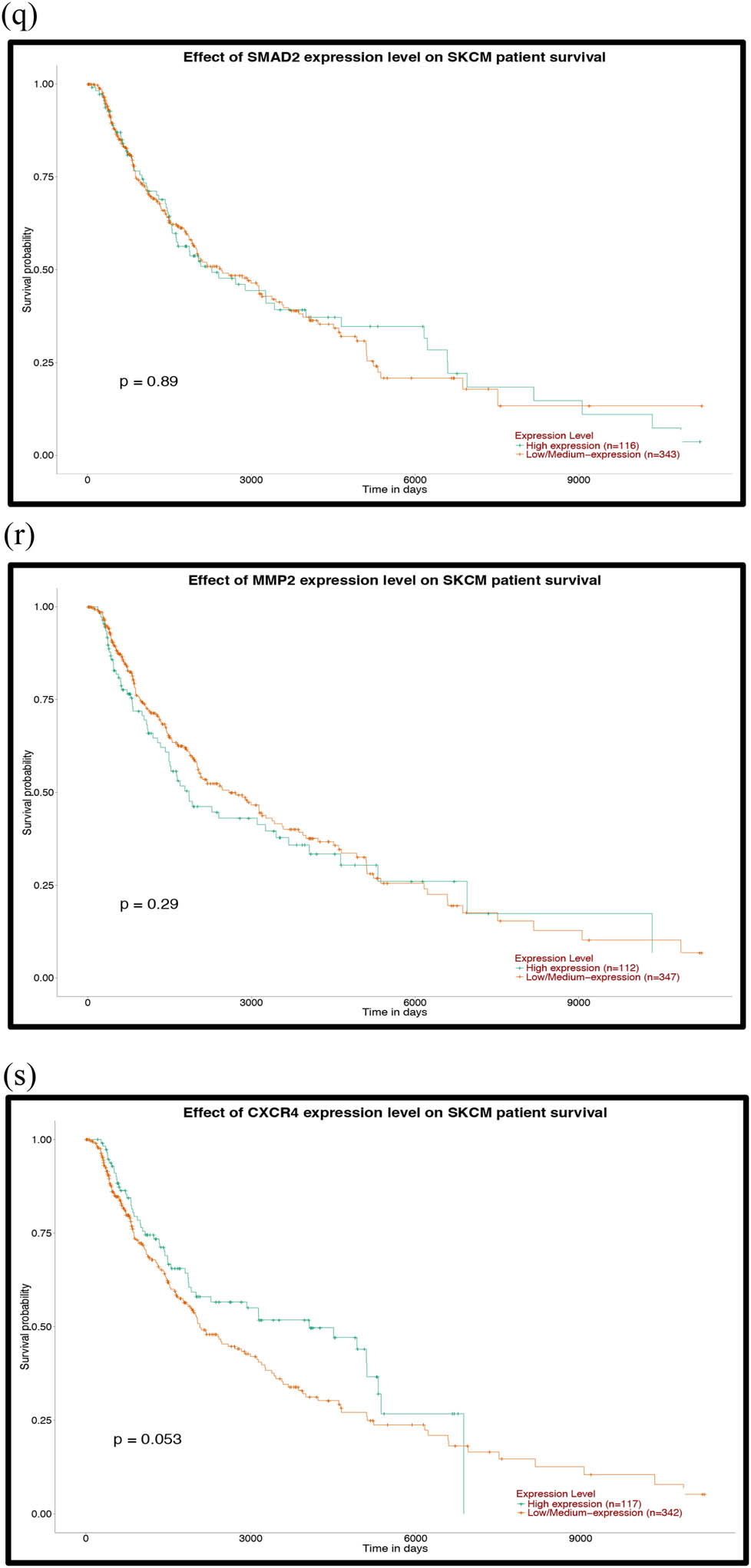

3.4 Prognostic analysis

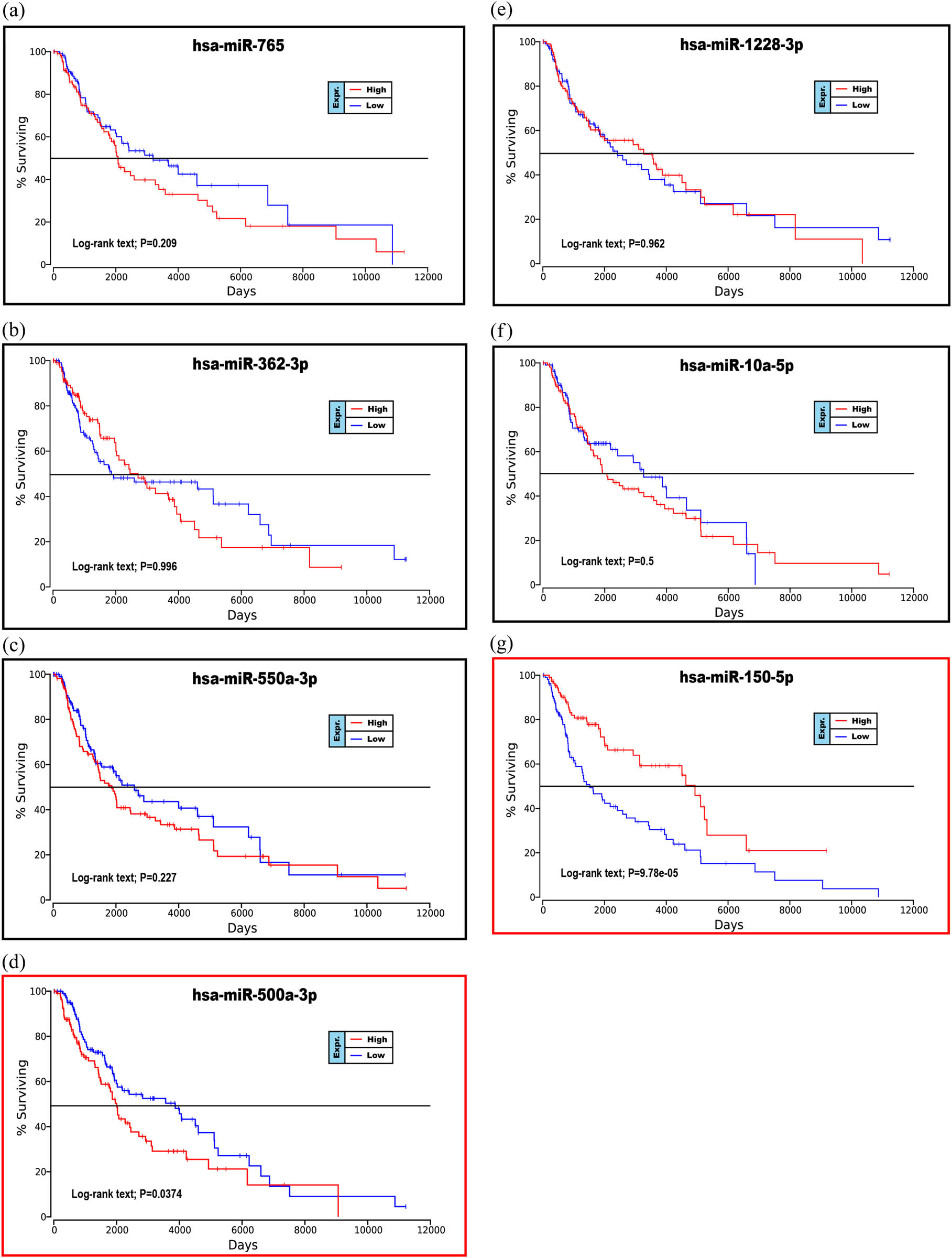

To further explore the relationship between patient prognosis and molecular markers, including the DE-miRNAs, the hub genes and the mutant genes. The UALCAN and OncoLnc online websites were used to analyze the relationship between these genes and the overall survival (OS) rate of patients with melanoma. We selected the top five genes with the highest degree of the above DE-miRNAs (the upregulated hsa-miR-765, hsa-miR-362-3p and hsa-miR-500a-3p and the downregulated hsa-miR-10a-5p and hsa-miR-150-5p) and the mutant genes associated with the downregulated genes for OS analysis. The results showed that there was no correlation between the mutated genes and the OS rate of patients (Figure 6a–d). High expression of CDK2 and POLR2A genes in melanoma patients significantly reduced OS (Figures 7a–k and 7e–s). The results of the correlation between the top five DE-miRNAs and the OS rate showed that there were no data for hsa-mir-3907 and hsa-mir-1238, and the expression of hsa-mir-765, hsa-mir-362-3p and hsa-mir-550a-3p had no correlation with the OS rate (Figure 8a–c, e and f). However, the OS rate of patients with high expression of hsa-mir-500a-3p and low expression of hsa-mir-150-5p was significantly decreased (Figure 8d and g).

Prognostic analysis of the mutant genes and the hub genes of the downregulated miRNAs with the UALCAN database: (a) TP53, (b) FAT4, (c) PTPRT, (d) GRIN2A, (e) EP300, (f) MAPK8, (g) PTEN, (h) HSPA8, (i) HSP90AA1, (j) APP, (k) POLR2A, (l) RPL23, (m) SP1, (n) ITPKB, (o) RBBP4, (p) YY1, (q) SMAD2, (r) MMP2 and (s) CXCR4. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Prognostic analysis of the hub genes of the upregulated miRNAs with the UALCAN database: (a) VEGFA, (b) PIK3R1, (c) HSPA4, (d) ABL1, (e) CHEK1, (f) CDK2, (g) IGF1R, (h) POLR2F, (i) CBL, (j) BTRC and (k) YWHAE. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Prognostic analysis of the upregulated or downregulated DE-miRNAs with the OncoLnc database: (a) hsa-miR-765, (b) hsa-miR-362-3p, (c) hsa-miR-550a-3p, (d) hsa-miR-500a-3p, (e) hsa-miR-1228-3p, (f) hsa-miR-10a-5p and (g) hsa-miR-150-5p. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4 Discussion

Melanoma originates from the neuroectoderm, which is transformed from the malignant transformation of melanocytes and is highly invasive and metastatic. Melanoma has become the most lethal type of skin cancer. Surgical resection is still the first choice for the treatment of early melanoma [3]. Advanced melanoma requires surgery combined with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy, but the prognosis of advanced melanoma remains unsatisfactory. Therefore, it is important to identify biomarkers that can be used for the early diagnosis and prognosis of melanoma. As an important information transfer material in the tumor microenvironment, pEVs have attracted the attention of scientists. A large number of studies have reported that DE-miRNAs in pEVs can be used as potential molecular markers for the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, prostate cancer and colorectal cancer [22,23,24]. Therefore, we hypothesized that DE-miRNAs in pEVs of melanoma patients may also be potential molecular targets for the diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. In this study, the GSE100508 microarray data were downloaded from the GEO database, and 55 DE-miRNAs in pEVs of melanoma patients were identified by differential analysis compared with pEVs in normal controls. In the pEVs of melanoma, hsa-miR-765 was the main upregulated miRNA, and hsa-miR-1238 was the main downregulated miRNA.

It has been shown that hsa-miR-765 and hsa-miR-1238 are associated with hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, glioblastoma and other malignant tumors [25,26,27]. Regarding hepatocellular carcinoma, hsa-miR-765 was significantly overexpressed in hepatoma cell lines and tissues compared with normal hepatocytes and paracancerous tissues. Then, it was verified that overexpression of hsa-miR-765 promotes the proliferation and tumorigenicity of hepatoma cells [25]. Regarding osteosarcoma, miR-300 was also highly enriched in human osteosarcoma cells and plays an important role in the regulation of developmental processes, cell processes and cell signaling pathways (such as Wnt, MAPK and p53 signaling pathway) [28]. Similarly, miR-1238 was significantly enriched in the serum of glioblastoma patients compared to healthy individuals, and loss of miR-238 may lead to the formation of drug-resistant glioblastoma via the CAV1/EGFR pathway [27]. In addition, a recent study reported that miR-765 plays an important role in the development of malignant melanoma [29]. The promoter of miR-765 binds directly to HOXB9, promotes self-transcription and then targets FOXA2 to regulate FOXA2, resulting in a decrease in FOXA2 and an increase in melanoma tumor stem cells. At the same time, the miR-765-mediated FOXA pathway maintains the characteristics of cancer stem cells and contributes to the survival of melanoma.

TGs are involved in the development of melanoma. Therefore, GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were performed on differential genes to explore the expression changes of TGs in the BP of melanoma. All TGs were primarily enriched in the BP category in cellular and metabolic processes. Previous studies have shown that key genes that regulate cellular processes maintain a balance between the proliferation and differentiation of melanocyte stem cells [29,30,31]. The acquisition or loss of key gene functions will disrupt the balance of melanocyte stem cells, leading to the development and progression of melanoma. In addition, recent studies have shown that there is heterogeneity in the metabolism of melanoma, which can utilize various resources to promote tumor development. At the same time, the metabolic process of melanoma has an important impact on the aggressiveness of the tumor [32]. The TGs of upregulated miRNAs were mainly enriched in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway, while the TGs that downregulated miRNAs were primarily enriched in the Wnt signaling pathway. Previous studies have shown that the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor pathway is not only a cancer cell autocrine regulatory factor but is also expressed in hormone-independent melanoma, which can negatively regulate the proliferation and metastasis of melanoma cells [33,34,35]. The Wnt signaling pathway controls key steps in cell polarity, proliferation and migration [36]. Kulikova et al. [37] found that abnormal activation of the Wnt pathway is one of the key signals leading to the development of melanoma. The typical and atypical Wnt pathways are involved in the formation and metastasis of melanoma, respectively.

Hub genes may play an important role in the onset and progression of melanoma. Through analysis of the PPI network of TGs, it was found that VEGFA is the main hub gene for upregulated miRNAs, while TP53 is the main hub gene for downregulated miRNAs. VEGF, a vascular endothelial growth factor, is involved in the formation of blood vessels in the tumor and the expansion of the vascular network. Erhard et al. [38] found that the invasive potential of metastatic melanoma is associated with vascularization. Therefore, VEGF may play an important role in the development of melanoma. A number of studies have shown that VEGF levels in plasma and lymph nodes of melanoma patients are significantly higher than those in the control group, which may contribute to the diagnosis of melanoma micrometastasis [39,40]. TP53 is one of the most common mutations in human cancer and can lead to the rapid deterioration of tumors [41]. We found that TP53 is also one of the common mutations in skin malignant melanoma by searching the COSMIC database. Regad [30] found that the encoded protein ARF is a stabilizer for p53, and patients with melanoma often exhibit p53 mutations due to frequent loss of ARF, which ultimately leads to excessive proliferation of melanoma cells. Interestingly, Kim et al. [42]. found that TP53 gene mutation resulted in high expression of p53 protein, which improved the survival rate of patients with stage III and IV melanoma. The results of this study are in contrast to the poor clinical prognosis of malignant tumors with common TP53 mutations, but the specific mechanisms have not been elucidated to date.

Prognostic correlation analysis of cutaneous melanoma with molecular markers found that high expression of hsa-miR-500a-3p, CDK2 and POLR2A genes or low expression of hsa-miR-150-5p can significantly reduce OS in melanoma patients. Azimi et al. [43] found that CDK2 is a driving factor for BRAF and Hsp90 inhibitor resistance. High expression of CDK2 causes melanoma patients to rapidly develop resistance to drug-targeted therapeutic agents, which leads to a decrease in OS. Frischknecht et al. [44] found that degradation of POLAR2 promotes apoptosis in melanoma cells. Therefore, the proliferation rate of melanoma cells in patients with high POLAR2 expression is significantly higher than that in patients with low expression, resulting in low OS.

However, this study still has many limitations. Tumor EVs are currently receiving increasing attention from researchers, but relevant data sets are still scarce. The sample size of patients with melanoma pEVs needs to be expanded to better support the aforementioned findings. In addition, this study found a large number of melanoma-related DE-miRNAs and TGs that require extensive follow-up research to validate.

5 Conclusions

This study analyzed the DE-miRNA expression in pEVs between melanoma patients and normal controls by bioinformatics. Then, the TGs associated with melanoma diagnosis and prognosis were predicted and analyzed. These DE-miRNAs and TGs may become new molecular targets for the early diagnosis and treatment of malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the teachers who guided this work for their thoughtful care.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

Funding: This work was supported by Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Clinical Research Program (grant number 20184Y0113).

Author contributions: Jiachao Xiong and Yan Xue performed the experiments and contributed equally to this work. Yan Xue and Jiachao Xiong analyzed data, Jiayi Zhao and Yuchong Wang analyzed and wrote the manuscript, and Yu Xia prepared figures and/or tables. Jiayi Zhao and Yuchong Wang are co-correspondents of this work. All the authors approved the final draft.

References

[1] Tsang M, Quesnel K, Vincent K, Hutchenreuther J, Postovit LM, Leask A. Insights into fibroblast plasticity: Cellular communication network 2 is required for activation of cancer-associated fibroblasts in a murine model of melanoma. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(1):206–21.10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.09.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Kaste SC. Imaging of pediatric cutaneous melanoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(11):1476–87.10.1007/s00247-019-04374-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Li J, Shi SZ, Wang JS, Liu Z, Xue JX, Wang JC, et al. Efficacy of melanoma patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors: protocol for an overview, and a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. 2019;98(27):e16342.10.1097/MD.0000000000016342Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Campbell LB, Kreicher KL, Gittleman HR, Strodtbeck K, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Bordeaux JS. Melanoma incidence in children and adolescents: decreasing trends in the United States. J Pediatr. 2015;166(6):1505–13.10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Li Q, Zhang LY, Wu S, Huang C, Liu J, Wang P, et al. Bioinformatics analysis identifies microRNAs and target genes associated with prognosis in patients with melanoma. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7784–94.10.12659/MSM.917082Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Chen S, Datta-Chaudhuri A, Deme P, Dickens A, Dastgheyb R, Bhargava P, et al. Lipidomic characterization of extracellular vesicles in human serum. J Circ Biomark. 2019;8:1849454419879848.10.1177/1849454419879848Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Bang C, Thum T. Exosomes: new players in cell–cell communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(11):2060–4.10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.007Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Chivet M, Hemming F, Pernet-Gallay K, Fraboulet S, Sadoul R. Emerging role of neuronal exosomes in the central nervous system. Front Physiol. 2012;3:145.10.3389/fphys.2012.00145Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Malm T, Loppi S, Kanninen KM. Exosomes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2016;97:193–9.10.1016/j.neuint.2016.04.011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Lau C, Kim Y, Chia D, Spielmann N, Eibl G, Elashoff D, et al. Role of pancreatic cancer-derived exosomes in salivary biomarker development. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(37):26888–97.10.1074/jbc.M113.452458Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Arscott WT, Camphausen KA. EGFR isoforms in exosomes as a novel method for biomarker discovery in pancreatic cancer. Biomark Med. 2011;5(6):821.10.2217/bmm.11.80Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Li Q, Geng S, Yuan H, Li Y, Zhang S, Pu L, et al. Circular RNA expression profiles in extracellular vesicles from the plasma of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. FEBS Open Biol. 2019.10.1002/2211-5463.12741Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Smyth GK, Michaud J, Scott HS. Use of within-array replicate spots for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):2067–75.10.1093/bioinformatics/bti270Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Minguet EG, Segard S, Charavay C, Parcy F. MORPHEUS, a webtool for transcription factor binding analysis using position weight matrices with dependency. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135586.10.1371/journal.pone.0135586Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Chou CH, Shrestha S, Yang CD, Chang NW, Lin YL, Liao KW, et al. miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D296–302.10.1093/nar/gkx1067Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D419–26.10.1093/nar/gky1038Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–13.10.1093/nar/gky1131Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Chin CH, Chen SH, Wu HH, Ho CW, Ko MT, Lin CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8(Suppl 4):S11.10.1186/1752-0509-8-S4-S11Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, Bamford S, Bindal N, Tate J, et al. COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D777–83.10.1093/nar/gkw1121Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Tokar T, Pastrello C, Rossos AEM, Abovsky M, Hauschild AC, Tsay M, et al. mirDIP 4.1-integrative database of human microRNA target predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D360–70.10.1093/nar/gkx1144Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B, et al. UALCAN: a portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649–58.10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Eitan E, Tosti V, Suire CN, Cava E, Berkowitz S, Bertozzi B, et al. In a randomized trial in prostate cancer patients, dietary protein restriction modifies markers of leptin and insulin signaling in plasma extracellular vesicles. Aging Cell. 2017;16(6):1430–3.10.1111/acel.12657Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Chen J, Xu Y, Wang X, Liu D, Yang F, Zhu X, et al. Rapid and efficient isolation and detection of extracellular vesicles from plasma for lung cancer diagnosis. Lab Chip. 2019;19(3):432–43.10.1039/C8LC01193ASuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Hosseini M, Khatamianfar S, Hassanian SM, Nedaeinia R, Shafiee M, Maftouh M, et al. Exosome-encapsulated microRNAs as potential circulating biomarkers in colon cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(11):1705–9.10.2174/1381612822666161201144634Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Xie BH, He X, Hua RX, Zhang B, Tan GS, Xiong SQ, et al. Mir-765 promotes cell proliferation by downregulating INPP4B expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16(3):405–13.10.3233/CBM-160579Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Yan L, Wu X, Liu Y, Xian W. LncRNA Linc00511 promotes osteosarcoma cell proliferation and migration through sponging miR-765. J Cell Biochem. 2018, 10.1002/jcb.27999.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Yin J, Zeng A, Zhang Z, Shi Z, Yan W, You Y. Exosomal transfer of miR-1238 contributes to temozolomide-resistance in glioblastoma. EBioMedicine. 2019;42:238–51.10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.03.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Dai N, Zhong ZY, Cun YP, Qing Y, Chen C, Jiang P, et al. Alteration of the microRNA expression profile in human osteosarcoma cells transfected with APE1 siRNA. Neoplasma. 2013;60(4):384–94.10.4149/neo_2013_050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lin J, Zhang D, Fan Y, Chao Y, Chang J, Li N, et al. Regulation of cancer stem cell self-renewal by HOXB9 antagonizes endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced melanoma cell apoptosis via the miR-765-FOXA2 axis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(7):1609–19.10.1016/j.jid.2018.01.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Regad T. Molecular and cellular pathogenesis of melanoma initiation and progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(21):4055–65.10.1007/s00018-013-1324-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Ross DT, Scherf U, Eisen MB, Perou CM, Rees C, Spellman P, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):227–35.10.1038/73432Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Fischer GM, Vashisht Gopal YN, McQuade JL, Peng W, DeBerardinis RJ, Davies MA. Metabolic strategies of melanoma cells: mechanisms, interactions with the tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic implications. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31(1):11–30.10.1111/pcmr.12661Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Limonta P, Moretti RM, Montagnani Marelli M, Motta M. The biology of gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone: role in the control of tumor growth and progression in humans. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24(4):279–95.10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.10.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Limonta P, Montagnani Marelli M, Mai S, Motta M, Martini L, Moretti RM. GnRH receptors in cancer: from cell biology to novel targeted therapeutic strategies. Endocr Rev. 2012;33(5):784–811.10.1210/er.2012-1014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Moretti RM, Monagnani Marelli M, van Groeninghen JC, Motta M, Limonta P. Inhibitory activity of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone on tumor growth and progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10(2):161–7.10.1677/erc.0.0100161Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Paluncic J, Kovacevic Z, Jansson PJ, Kalinowski D, Merlot AM, Huang ML, et al. Roads to melanoma: key pathways and emerging players in melanoma progression and oncogenic signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(4):770–84.10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.01.025Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Kulikova KV, Kibardin AV, Gnuchev NV, Georgiev GP, Larin SS. Wnt signaling pathway and its significance for melanoma development. Sovremennye Tehnologii. 2012;2012(3):107–11.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Erhard H, Rietveld FJ, van Altena MC, Brocker EB, Ruiter DJ, de Waal RM. Transition of horizontal to vertical growth phase melanoma is accompanied by induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis. Melanoma Res. 1997;7(Suppl 2):S19–26.10.1097/00008390-199708001-00005Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Gacevic M, Jovic M, Zolotarevski L, Stanojevic I, Novakovic M, Miller K, et al. Association of vascular endothelial growth factor expression with patohistological parameters of cutaneous melanoma. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2016;73(5):449–57.10.2298/VSP140804027GSuche in Google Scholar

[40] Martinez-Garcia MA, Riveiro-Falkenbach E, Rodriguez-Peralto JL, Nagore E, Martorell-Calatayud A, Campos-Rodriguez F, et al. A prospective multicenter cohort study of cutaneous melanoma: clinical staging and potential associations with HIF-1alpha and VEGF expressions. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(6):558–64.10.1097/CMR.0000000000000393Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Xiao W, Du N, Huang T, Guo J, Mo X, Yuan T, et al. TP53 mutation as potential negative predictor for response of anti-CTLA-4 therapy in metastatic melanoma. EBioMedicine. 2018;32:119–24.10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.05.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Kim DW, Haydu LE, Joon AY, Bassett Jr RL, Siroy AE, Tetzlaff MT, et al. Clinicopathological features and clinical outcomes associated with TP53 and BRAF(N)(on-)(V)(600) mutations in cutaneous melanoma patients. Cancer. 2017;123(8):1372–81.10.1002/cncr.30463Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Azimi A, Caramuta S, Seashore-Ludlow B, Bostrom J, Robinson JL, Edfors F, et al. Targeting CDK2 overcomes melanoma resistance against BRAF and Hsp90 inhibitors. Mol Syst Biol. 2018;14(3):e7858.10.15252/msb.20177858Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Frischknecht L, Britschgi C, Galliker P, Christinat Y, Vichalkovski A, Gstaiger M, et al. BRAF inhibition sensitizes melanoma cells to alpha-amanitin via decreased RNA polymerase II assembly. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7779.10.1038/s41598-019-44112-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Jiachao Xiong et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway