Abstract

Aim

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the survival of severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, but data with regard to risk factors for disease progression from milder COVID-19 to severe COVID-19 remain scarce.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis on 116 patients.

Results

Three factors were observed to be independently associated with progression to severe COVID-19 during 14 days after admission: (a) age 65 years or older (hazard ratio [HR] = 8.456; 95% CI: 2.706–26.426); (b) creatine kinase (CK) ≥ 180 U/L (HR = 3.667; 95% CI: 1.253–10.733); and (c) CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL (HR = 4.695; 95% CI: 1.483–14.856). The difference in rates of severe COVID-19 development was found to be statistically significant between patients aged 65 years or older (46.2%) and those younger than 65 years (90.2%), between patients with CK ≥ 180 U/L (55.6%) and those with CK < 180 U/L (91.5%), and between patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL (53.8%) and those with CD4+ cell counts ≥300 cells/µL (83.2%).

Conclusions

Age ≥ 65 years, CK ≥ 180 U/L, and CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL at admission were risk factors independently associated with disease progression to severe COVID-19 during 14 days after admission and are therefore potential markers for disease progression in patients with milder COVID-19.

1 Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, the provincial capital of Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 [1]. The virus is known to spread with ease from person to person among close contacts [2] and may cause an acute respiratory illness, which has been named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Most patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection develop mild to moderate upper respiratory tract symptoms, whereas others may develop severe respiratory distress, systemic sepsis, septic shock, and death [3,4,5]. Some patients present with fever and respiratory symptoms such as cough and shortness of breath, and others may present with gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain [6]. In addition, some atypical symptoms such as altered mental status, symptoms of stroke, and olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions have been described [7,8]. Although patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 usually have a good prognosis, severe COVID-19 is associated with high mortality.

Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the survival of severe COVID-19 patients. As most patients who develop severe COVID-19 start with mild symptoms and later progress to severe disease, it is imperative to identify potential risk factors for disease progression in this population. This may help healthcare providers timeously identify patients with disease progression potential, thus facilitating early diagnosis and treatment of severe COVID-19. However, data with regard to potential risk factors for disease progression from mild or moderate COVID-19 to severe COVID-19 outside Wuhan remain scarce in the published literature and therefore warrant further investigation.

Our infectious disease hospital began admitting COVID-19 patients from January 24, 2020, and over 200 COVID-19 patients had been admitted up until February 20, 2020. The majority were diagnosed with mild or moderate COVID-19 at admission. However, a subgroup of these milder COVID-19 patients progressed to severe COVID-19 during their hospital stay, whereas others stabilized and recovered. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients admitted to our hospital with milder COVID-19, including those who progressed to severe disease after admission. Our objective was to investigate the presence of potential risk factors associated with disease severity progression in the natural history of COVID-19.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Ethics, consent, and permissions

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Public Health Medical Center (2020-003-01-KY). Informed consent was waived as all data were retrospective and were collected anonymously.

2.2 Patient enrollment and data collection

We included all patients aged 18 or older who had a confirmed diagnosis of mild or moderate COVID-19, who were admitted to Chongqing Public Health Medical Center, China, from January 24, 2020, to February 7, 2020. We transcribed demographics, epidemiological information, clinical manifestations, and clinical outcomes of eligible patients from the electronic hospital medical record system onto case record forms. Laboratory test results including blood gas analysis, hematological analysis, C-reactive protein, coagulation tests, myocardial enzymes, clinical chemistry, and lymphocyte subsets were also extracted from the records and recorded.

Patients exhibiting one or more of the following conditions were classified as having severe COVID-19: (a) respiratory distress (≥30 breaths/min); (b) oxygen saturation ≤93% at rest; (c) arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspiration O2 (FiO2) ≤300 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa); (d) respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation; (e) development of septic shock; and (f) critical organ failure requiring ICU care. Patients not meeting the aforementioned criteria were classified as mild or moderate COVID-19 cases and referred to as “milder” cases as a stratification category to clearly differentiate between milder and severe cases of COVID-19 in our data analysis.

2.3 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, Version 19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were described as frequency rates and percentages and compared via the Chi-squared test or the Fisher exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were described using mean, median, and interquartile range (IQR) values. Mean values for continuous variables were compared using independent group t-tests when the data were normally distributed; otherwise, the Mann–Whitney test was used. Statistical significance was assumed when p-values less than 0.05 were calculated. Furthermore, time to developing severe COVID-19 was analyzed over the duration of 14 days of hospitalization by the Kaplan–Meier method. The hypothesis test was two tailed, with a p ≤ 0.05 indicative of statistical significance. Cox regression was applied to estimate the unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of risk factors for disease progression during 14 days of hospitalization, and adjusted HRs were identified by using a forward stepwise approach.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

A total of 130 patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 were admitted to our hospital from January 24, 2020, to February 7, 2020. After excluding four patients younger than 18 years and ten patients diagnosed with severe COVID-19 at admission, a total of 116 patients were included for the analysis in this study. Of them, 17 patients (14.7%) eventually developed severe disease, while 99 patients (85.3%) did not meet the criteria for diagnosis of severe COVID-19 during 14 days of hospitalization.

As depicted in Table 1, patients who developed severe COVID-19 were significantly older (59 years [IQR, 50–70] vs 41 years [IQR, 35–54], p < 0.001) compared with those who did not develop severe COVID-19. In the 17 patients who went on to develop severe COVID-19 during 14 days of hospitalization, the median duration from the symptom onset to the diagnosis of severe COVID-19 was 12 days (IQR, 10–15), and the median duration from hospital admission to diagnosis of severe COVID-19 was 6 days (IQR, 4–9).

Patient characteristics at hospital admission

| Characteristics | Total (n = 116) | No progression to severe COVID-19 (n = 99) | Progression to severe COVID-19 (n = 17) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical age, median (IQR), years | 46 (36–56) | 41 (35–54) | 59 (50–70) | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 59 | 51 (51.5) | 8 (47.1) | 0.734 |

| Female | 57 | 48 (48.5) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Married, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 98 | 82 (82.8) | 16 (94.1) | 0.409 |

| No | 18 | 17 (17.2) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 17 (17.2) | 4 (23.5) | 0.773 |

| No | 95 | 82 (82.8) | 13 (76.5) | |

| BMI | 23.69 ± 2.92 | 23.6 ± 2.92 | 24.11 ± 2.94 | 0.527 |

| Symptoms at admission, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 106 | 90 (90.9) | 16 (94.1) | 1.000 |

| No | 10 | 9 (9.1) | 1 (5.9) | |

| History of stay in Wuhan, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 37 | 34 (34.3) | 3 (17.6) | 0.172 |

| No | 79 | 65 (65.7) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 7 (7.1) | 2 (13.3) | 0.859 |

| No | 107 | 92 (92.9) | 15 (86.7) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 11 (11.1) | 3 (17.6) | 0.718 |

| No | 102 | 88 (88.9) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Time from symptom onset to hospital admission, median (IQR), d | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.224 |

| Time from symptom onset to severe COVID-19, median (IQR), d | — | — | 12 (10–15) | — |

| Time from hospital admission to severe COVID-19, median (IQR), d | — | — | 6 (4–9) | — |

BMI: body mass index; IQR: interquartile range.

3.2 Comparison of clinical manifestations between the two groups

In our cohort of 116 patients, fever was the most common symptom at illness onset, occurring in 67.2% of patients in our cohort, followed by cough (59.5%), sputum production (37.9%), fatigue (27.6%), and anorexia (23.3%). In addition, some patients presented with atypical symptoms including heart palpitations (0.9%), xerostomia (0.9%), hemoptysis (0.9%), hyposmia (0.9%), and low back pain (1.7%). There were no significant differences in clinical symptoms between patients who developed severe COVID-19 and those who did not during 14 days of hospitalization after admission in our cohort (Table 2).

Clinical manifestations of patients with COVID-19 at hospital admission

| Signs and symptoms | Total | No progression to severe COVID-19 | Progression to severe COVID-19 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 78 | 67 (67.7) | 11 (64.7) | 0.809 |

| No | 38 | 32 (32.2) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Rigors, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 7 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.562 |

| No | 109 | 92 (92.9) | 17 (100) | |

| Fatigue, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 32 | 28 (28.3) | 4 (23.5) | 0.911 |

| No | 84 | 71 (71.7) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Cough, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 58 (58.6) | 11 (64.7) | 0.635 |

| No | 47 | 41 (41.4) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Dyspnea, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 (11.7) | 0.056 |

| No | 113 | 98 (99.0) | 15 (88.2) | |

| Sputum, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 44 | 36 (36.4) | 8 (47.1) | 0.401 |

| No | 72 | 63 (63.6) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Sore throat, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 17 (17.2) | 3 (17.6) | 1.000 |

| No | 96 | 82 (82.8) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Xerostomia, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| No | 115 | 98 (99.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Hemoptysis, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.147 |

| No | 115 | 99 (100) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Palpitations, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.147 |

| No | 115 | 99 (100.0) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Myalgia, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 9 (9.2) | 1 (6.7) | 1.000 |

| No | 106 | 89 (90.8) | 14 (93.3) | |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 3 (3.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.474 |

| No | 112 | 96 (97.0) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Low back pain, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| No | 114 | 97 (98.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 3 (3.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.474 |

| No | 112 | 96 (97.0) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Nausea and vomiting, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 4 | 3 (3.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0.474 |

| No | 112 | 96 (97.0) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 9 (9.1) | 1 (5.9) | 1.000 |

| No | 106 | 90 (90.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Anorexia, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 22 (22.2) | 5 (29.4) | 0.736 |

| No | 89 | 77 (77.8) | 12 (70.6) | |

| Headache, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 12 (12.1) | 3 (17.6) | 0.813 |

| No | 101 | 87 (87.9) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Dizziness, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 11 (11.1) | 3 (17.6) | 0.718 |

| No | 102 | 88 (88.9) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Hyposmia, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| No | 115 | 98 (99.0) | 17 (100.0) | |

| Asymptomatic, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 9 (9.1) | 1 (5.9) | 1.000 |

| No | 106 | 90 (90.9) | 16 (94.1) | |

| Moist rales, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 6 (6.1) | 3(33.3) | 0.246 |

| No | 107 | 93 (93.9) | 14 (82.4) | |

| Median pulse, mean ± SD, beats/min | 90.06 ± 13.065 | 90.40 ± 13.293 | 88.06 ± 11.808 | 0.465 |

| Median systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 127.25 ± 15.148 | 126.69 ± 15.116 | 130.53 ± 15.371 | 0.336 |

SD: standard deviation.

3.3 Comparison of laboratory test results between the two groups

Compared with patients who had milder COVID-19, those who developed severe COVID-19 after admission had significantly lower lymphocyte counts, platelet counts, estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs), CD4+ T-cell counts, CD8+ T-cell counts, and PaO2/FiO2 ratios, and significantly higher C-reactive protein levels, lactate dehydrogenase levels, aspartate transaminase levels, and beta 2-microglobulin levels (Table 3).

Laboratory findings of patients with COVID-19 at hospital admission

| Laboratory values | Number of patients | Total | No progression to severe COVID-19 | Progression to severe COVID-19 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 115 | 4.84 (3.87–5.84) | 4.81 (3.85–6.05) | 4.96 (3.89–5.54) | 0.741 |

| Neutrophil count (×109/L) | 114 | 2.87 (2.00–3.95) | 2.77 (1.98–3.95) | 3.41 (2.55–4.12) | 0.310 |

| Lymphocyte count (×109/L) | 115 | 1.32 (1.060–1.76) | 1.45 (1.18–1.78) | 1.03 (0.74–1.28) | 0.002 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 115 | 163 (128–212) | 169.5 (132.25–214.00) | 136 (96–174) | 0.029 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 115 | 136 (125–147) | 137.5 (124.75–148) | 128 (122–139) | 0.117 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 112 | 9.36 (2.96–26.26) | 7.99 (2.87–21.57) | 25.55 (10.03–70.17) | 0.002 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 112 | 0.16 (0.10–0.26) | 0.14 (0.09–0.25) | 0.21 (0.12–0.3) | 0.157 |

| CK (U/L) | 112 | 74.5 (49.5–128) | 70.5 (47.5–108.25) | 149 (53.25–299) | 0.088 |

| LDH (U/L) | 116 | 195 (164–251) | 190 (163–237) | 273 (185.5–310.5) | 0.003 |

| ALT (U/L) | 116 | 21 (13.25–31.75) | 21 (13–31) | 21 (15–52) | 0.290 |

| AST (U/L) | 116 | 24 (19–31) | 22 (18–28) | 33 (25–46.5) | 0.002 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 116 | 42.236 ± 3.657 | 42.273 ± 3.544 | 40.613 ± 3.649 | 0.095 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 116 | 13.05 (9.625–19.150) | 12.7 (9.6–17.8) | 17.6 (11.2–22.6) | 0.102 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 115 | 70.1 (59.3–84) | 69.65 (58.08–83.55) | 70.1 (61–89.35) | 0.555 |

| Beta 2-microglobulin (mg/L) | 114 | 2.57 (2.15–3.05) | 2.51 (2.14–2.95) | 3.34 (2.53–3.79) | 0.004 |

| eGFR | 115 | 98.36 ± 18.83 | 100.51 ± 18.177 | 83.94 ± 18.164 | 0.006 |

| CD4+ T-cell counts (cells/µL) | 85 | 424 (264–594) | 478 (322–606) | 243.5 (223–290.75) | <0.001 |

| CD8+ T-cell counts (cells/µL) | 83 | 316 (207–459) | 359 (231–490) | 159.5 (126–313.25) | 0.003 |

| CD4+ T-cell counts/CD8+ cell counts | 83 | 1.31 (0.98–1.75) | 1.36 (1.01–1.73) | 1.13 (0.76–1.97) | 0.403 |

| PaO2/FiO2 (mmHg) | 74 | 414.28 (365.48–455.54) | 419 (376.19–471.42) | 366.67 (321.67–413.14) | 0.005 |

LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen; PaO2/FiO2: partial arterial oxygen concentration/inspired oxygen faction.

3.4 Comparison of therapeutic interventions between the two groups

The proportion of antibiotic use in patients who developed severe COVID-19 was significantly higher than in patients who did not develop severe COVID-19 (35.3% vs 10.1%, p = 0.016) during 14 days of hospitalization. However, we found no statistical correlation in the relative use of lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin, and traditional Chinese medicine between the two groups of patients, as presented in Table 4.

Treatment of COVID-19 patients within 14 days after admission

| Characteristics | Total | No progression to severe COVID-19 | Progression to severe COVID-19 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPV/r, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 88 | 74 (74.7) | 14 (82.4) | 0.711 |

| No | 28 | 25 (25.3) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Ribavirin, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 46 | 42 (42.4) | 4 (23.5) | 0.141 |

| No | 70 | 57 (57.6) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Antibiotics, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 10 (10.1) | 6 (35.3) | 0.016 |

| No | 100 | 89 (89.9) | 11 (64.7) | |

| TCM, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 26 (26.3) | 4 (23.5) | 1.000 |

| No | 86 | 73 (73.7) | 13 (76.5) | |

LPV/r: lopinavir/ritonavir; TCM: traditional Chinese medicine.

3.5 Independent risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19

All variables with a p ≤ 0.1 in the univariate analysis, other than lymphocyte counts, were included in a Cox proportional hazards model and adjusted for symptoms at admission, ribavirin use, lopinavir/ritonavir use, comorbid diabetes, and comorbid hypertension. We did not include lymphocyte counts in this model to avoid the possible multicollinearity effect on CD4+ T-cell counts.

Three factors were found to be independently associated with progression to severe COVID-19 (Table 5) during 14 days of hospitalization after admission, and these factors are as follows: (a) age 65 years or older (HR = 8.456; 95% CI: 2.706–26.426; p < 0.001); (b) creatine kinase (CK) ≥ 180 U/L (HR = 3.667; 95% CI: 1.253–10.733; p = 0.018); and (c) CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL (HR = 4.695; 95% CI: 1.483–14.856; p = 0.009).

Independent risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19

| Total | Progression to severe COVID-19 | p | HR | 95% CI | p | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||

| <65 years | 103 | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥65 years | 13 | 7 | <0.001 | 8.226 | 3.102–21.817 | <0.001 | 8.456 | 2.706–26.426 |

| Symptoms at admission, n | ||||||||

| No | 10 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 106 | 16 | 0.637 | 1.628 | 0.216–12.274 | |||

| BMI | ||||||||

| <24 | 55 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| ≥24 | 42 | 10 | 0.093 | 2.382 | 0.865–6.557 | |||

| Unknown | 19 | 1 | 0.480 | 0.466 | 0.056–3.873 | |||

| Ribavirin, n | ||||||||

| Yes | 46 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| No | 70 | 13 | 0.141 | 2.323 | 0.757–7.125 | |||

| LPV/r, n | ||||||||

| Yes | 88 | 14 | 1 | |||||

| No | 28 | 3 | 0.476 | 1.574 | 0.452–5.477 | |||

| Antibiotics, n | ||||||||

| No | 100 | 11 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 16 | 6 | 0.006 | 3.996 | 1.476–10.821 | |||

| Dyspnea, n | ||||||||

| No | 113 | 15 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 3 | 2 | 0.004 | 9.015 | 2.027–40.092 | |||

| Diabetes, n | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| No | 107 | 15 | 0.477 | 0.585 | 0.134–2.561 | |||

| Hypertension, n | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| No | 102 | 14 | 0.409 | 0.591 | 0.170–2.058 | |||

| Platelet count | ||||||||

| ≥100 × 109/L | 104 | 13 | 1 | |||||

| <100 × 109/L | 11 | 4 | 0.038 | 3.273 | 1.066–10.051 | |||

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0.988 | 0 | 0 | |||

| C-reactive protein | ||||||||

| <20 mg/L | 74 | 6 | 1 | |||||

| ≥20 mg/L | 38 | 11 | 0.005 | 4.166 | 1.540–11.274 | |||

| Unknown | 4 | 0 | 0.985 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CK | ||||||||

| <180 U/L | 94 | 8 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ≥180 U/L | 18 | 8 | <0.001 | 6.575 | 2.458–17.590 | 0.018 | 3.667 | 1.253–10.733 |

| Unknown | 4 | 1 | 0.311 | 2.927 | 0.366–23.409 | 0.666 | 1.693 | 0.156–18.427 |

| LDH | ||||||||

| <250 U/L | 87 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| ≥250 U/L | 29 | 10 | 0.001 | 5.06 | 1.925–13.305 | |||

| AST | ||||||||

| <40 U/L | 100 | 12 | 1 | |||||

| ≥40 U/L | 16 | 5 | 0.052 | 2.810 | 0.989–7.981 | |||

| Albumin | ||||||||

| ≥40 g/L | 87 | 9 | 1 | |||||

| <40 g/L | 29 | 8 | 0.026 | 2.954 | 1.139–7.660 | |||

| Beta-2 microglobulin | ||||||||

| <28 mg/L | 68 | 5 | 1 | |||||

| ≥28 mg/L | 46 | 12 | 0.009 | 3.987 | 1.404–11.326 | |||

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 0.983 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| eGFR | ||||||||

| ≥100 | 59 | 4 | 0.264 | |||||

| <100 | 56 | 13 | 0.020 | 3.793 | 1.236–11.638 | |||

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0.988 | 0 | 0 | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 | ||||||||

| ≥400 mmHg | 41 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| <400 mmHg | 33 | 10 | 0.015 | 4.941 | 1.359–17.968 | |||

| Unknown | 42 | 4 | 0.747 | 1.280 | 0.286–5.719 | |||

| CD4+ T-cell counts | ||||||||

| ≥300/µL | 59 | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| <300/µL | 26 | 12 | <0.001 | 8.778 | 2.825–27.275 | 0.009 | 4.695 | 1.483–14.856 |

| Unknown | 31 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.467 | 0.052–4.177 | 0.461 | 0.397 | 0.034–4.626 |

| CD8+ T-cell counts | ||||||||

| ≥238/µL | 56 | 7 | ||||||

| <238/µL | 27 | 9 | 0.028 | 3.022 | 1.125–8.118 | |||

| Unknown | 33 | 1 | 0.170 | 0.230 | 0.028–1.872 | |||

BMI: body mass index; LPV/r: lopinavir/ritonavir; CK: creatine kinase; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; PaO2/FiO2: partial arterial oxygen concentration/inspired oxygen faction; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

3.6 Relationship between the number of risk factors considered (age > 65, CK ≥ 180, CD4+ T-cell counts <300) and progression to severe COVID-19

The number of risk factors considered (age > 65, CK ≥ 180, and CD4+ cell counts <300) was included in a Cox proportional hazards model and adjusted for symptoms at admission, including body mass index, ribavirin use, lopinavir/ritonavir use, antibiotic use, dyspnea, comorbid diabetes, comorbid hypertension, platelet count, C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, albumin, Beta-2 microglobulin, eGFR, PaO2/FiO2, and CD8+ T-cell counts.

The consideration of one to two of our observed risk factors (HR = 10.644; 95% CI: 2.305–49.159; p = 0.002) and all three risk factors (HR = 252.368; 95% CI: 24.390–2611.295; p < 0.001) were found to be independently associated with progression to severe COVID-19 (Table 6) during 14 days of hospitalization after admission.

Independent risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19

| Total | Progression to severe COVID-19 | p | HR | 95% CI | p | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of factors (age > 65, CK ≥ 180, CD4+ cell counts <300) | ||||||||

| 0 | 50 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1–2 | 31 | 11 | 0.02 | 10.967 | 2.428–49.532 | 0.002 | 10.644 | 2.305–49.159 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | <0.001 | 110.007 | 13.298–910.009 | <0.001 | 252.368 | 24.390–2611.295 |

| Unknown | 33 | 2 | 0.677 | 1.517 | 0.214–10.771 | 0.490 | 2.006 | 0.277–14.497 |

CK: creatine kinase; adjustment variables: symptoms at admission, body mass index, ribavirin use, lopinavir/ritonavir use, antibiotics use, dyspnea, comorbid diabetes, comorbid hypertension, platelet count, C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotransferase, albumin, beta-2 microglobulin, estimated glomerular filtration rate, partial arterial oxygen concentration/inspired oxygen faction, CD8+ cell counts.

3.7 Fourteen-day cumulative survival without developing severe COVID-19

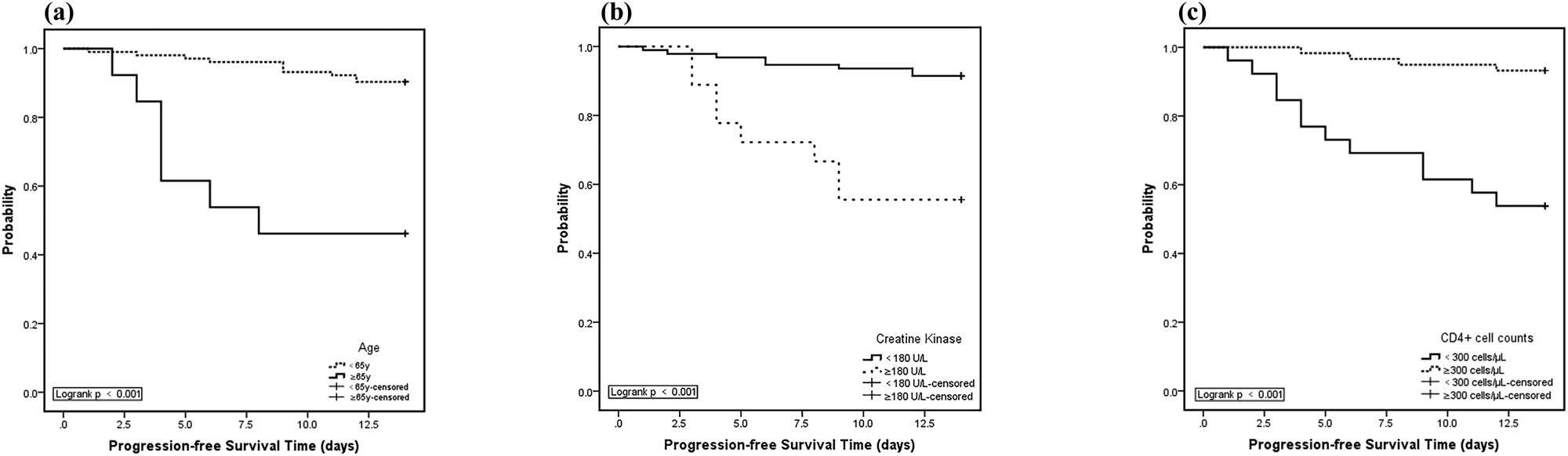

We analyzed the period from admission to developing severe COVID-19 over the duration of 14 days by the Kaplan–Meier method. We found that in patients aged 65 years or older, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 46.2%, whereas in patients younger than 65 years, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 90.2%, and the calculated difference in the rates of severe COVID-19 development between the two groups of patients was found to be significant in the statistical analysis.

The following findings were also observed in our analysis. In patients with a CK ≥ 180 U/L, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 55.6%, whereas in patients with a CK < 180 U/L, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 91.5%, and again, there was a significant statistically calculated difference between these two rates of progression. In patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 53.8%, whereas in patients with CD4+ T-cell counts ≥300 cells/µL, the rate of not progressing to severe COVID-19 at the end of 14 days was 83.2%, and the statistical difference between these two groups of patients was, again, computed to be significant (Figure 1).

Kaplan–Meier curves for rates of not developing severe COVID-19 during 14 days after hospital admission. (a) Kaplan–Meier curves showed worse progression-free survival rates for COVID-19 patients aged 65 years or older compared to patients younger than 65 years (p < 0.001, two sided); (b) Kaplan–Meier curves showed worse progression-free survival rates for COVID-19 patients with CK ≥180 U/L compared to patients with CK <180 U/L (p < 0.001, two sided); (c) Kaplan–Meier curves showed worse progression-free survival rates for COVID-19 patients with CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL compared to patients with CD4+ T-cell counts ≥300 cells/µL (p < 0.001, two sided).

4 Discussion

This study investigated the risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19 in patients diagnosed as mild or moderate COVID-19. The median age of patients developing severe COVID-19 during the hospitalized period of 14 days was significantly higher than that of those not developing severe COVID-19 (59 years [IQR, 50–70] vs 41 years [IQR, 35–54], p < 0 .001), which concurs with the study results published previously [9].

In our study cohort of patients with milder COVID-19, we failed to observe a significant association between the presence of chronic diseases and the risk of disease progression, suggesting that the presence of chronic diseases may not necessarily contribute significantly to disease severity progression in such patients. Previous studies, however, have observed that some underlying chronic diseases, including hypertension and diabetes, may be risk factors for poor prognosis of COVID-19 [10,11,12]. The poor correlation of our results compared to that of other studies may be secondary to dissimilar study populations, differing sample sizes, and results obtained at different stages and locations of the COVID-19 outbreak, and warrants further investigation.

As outlined in Table 2, we did not observe any association between clinical symptoms and risk of disease progression. Frequently reported symptoms in our cohort of patients included fever, cough, sputum production, and fatigue. There were no significant differences in the proportion of patients progressing to severe COVID-19 between patients who exhibited the aforementioned symptoms and those who did not, suggesting that these symptoms were not sensitive indicators for disease progression in milder COVID-19 patients.

Compared with patients not developing severe COVID-19 during the period of 14 days after admission, patients progressing to severe COVID-19 during this period were more likely to have been administered antibiotics (10.1% vs 35.3%, p = 0.016). Antibiotics were used in this subgroup of patients to prevent or treat secondary nosocomial bacterial infections. Our result indicates that antibiotic use may not be useful in arresting disease progression in the natural history of COVID-19.

In the present study, we found that age ≥65 years, CK ≥ 180 U/L, and CD4+ cell counts <300 cells/µL at admission were associated with disease progression during 14 days after hospital admission in patients with milder COVID-19. This result concurs with the previous study results in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and COVID-19, in which older age was also found to be a risk factor for progression to severe disease [13,14,15,16,17]. Similarly, a recent study from Wuhan also found that laboratory cardiac injury diagnostic parameters, including CK, were associated with poor prognosis in COVID-19 patients [18]. This has also been observed in patients developing severe SARS and MERS, who also tended to have significantly higher CK levels (≥180 U/L) [19,20]. Secondary systemic myositis as a direct consequence of coronavirus infection may be a reasonable explanation for this increase in CK levels [21]. In addition, a decline in CK levels has been significantly associated with COVID-19 mRNA clearance ratios, which may indicate that this may be a good indicator for recovery of COVID-19 infection [22]. Wong et al. reported that T-lymphocyte subsets may be depleted early in the course of SARS and that low levels of CD4+ T-cell and CD8+ T-cell counts may be associated with poor clinical outcomes [23]. In the present study, we also observed that a CD4+ T-cell count <300 cells/µL was an independent risk factor for progression to severe COVID-19, suggesting that patients with milder COVID-19 develop CD4+ T-cell count depletion before significant disease progression, which was similar to the study conducted in Shanghai [17].

Our study has limitations. First, as a retrospective, observational study, it is inevitable that some data were incomplete, and this could possibly have led to biased effect estimate results. Second, the study period for data observation was only 14 days, which may not have been a long enough period to reflect actual disease progression during the course of the natural history of COVID-19. Third, the number of different factors included in our study for univariate and multivariate analyses may not have been comprehensive enough, and some potential risk factors may have been missed. Despite these limitations, our results may nevertheless be useful to indicate potential markers for possible disease progression in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19.

We observed that age ≥65 years, CK ≥ 180 U/L, and CD4+ T-cell counts <300 cells/µL at admission were risk factors associated with disease progression to severe COVID-19 during 14 days after admission. These factors may represent potential markers for possible disease progression in patients with milder COVID-19. Affording due attention to these risk factors may facilitate early identification of patients with the potential for progression to severe COVID-19 in the mild and moderate COVID-19 patient population. Patients with these risk factors will require close monitoring for potential COVID-19 disease progression during their hospital admission.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CK

Creatine kinase

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HR

Hazard ratios

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- LPV/r

Lopinavir/Ritonavir

- MERS

Middle east respiratory syndrome

- PaO2

Partial pressure of oxygen

- PaO2/FiO2

Partial arterial oxygen concentration/inspired oxygen faction

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SD

Standard deviation

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chongqing Special Research Project for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention and Control (No. cstc2020jscx-fyzxX0005). The funding body had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, and the decision to submit for publication.

Author contributions: Y-KC, Y-HZ, and Y-YQ designed and executed this analysis. Y-KC and Y-HZ contributed to revising and finalizing the manuscript. HL, X-FY, and VH helped to revise the protocol. Y-QL, H-LL, S-KY, YW, and LZ contributed to data collection and management. All authors contributed to the refinement of the study protocol and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–74.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–207.10.1056/NEJMoa2001316Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):514–23.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–3.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Wong SH, Lui RN, Sung JJ. Covid-19 and the digestive system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(5):744–8.10.1111/jgh.15047Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Singhania N, Bansal S, Singhania G. An atypical presentation of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am J Med. 2020;133(7):e365–6. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.026.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60.10.1056/NEJMc2009787Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Alqahtani FY, Aleanizy FS, Ali El Hadi Mohamed R, Alanazi MS, Mohamed N, Alrasheed MM, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a retrospective study. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e35. 10.1017/S0950268818002923.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Barrak A, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(9):752–61.10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Guo W, Li M, Dong Y, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Tian C, et al. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;e3319. 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [Epub ahead of print].Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Ahmed AE. The predictors of 3- and 30-day mortality in 660 MERS-CoV patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):615.10.1186/s12879-017-2712-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Alfaraj SH, Al-Tawfiq JA, Assiri AY, Alzahrani NA, Alanazi AA, Memish ZA. Clinical predictors of mortality of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: a cohort study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;29:48–50.10.1016/j.tmaid.2019.03.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Chen CY, Lee CH, Liu CY, Wang JH, Wang LM, Perng RP. Clinical features and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome and predictive factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Chin Med Assoc. 2005;68(1):4–10.10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70124-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Gong J, Ou J, Qiu X, Jie Y, Chen Y, Yuan L, et al. A tool to early predict severe corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multicenter study using the risk nomogram in Wuhan and Guangdong, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):833–40. 10.1093/cid/ciaa443.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Chen J, Qi T, Liu L, Ling Y, Qian Z, Li T, et al. Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. J Infect. 2020;80(5):e1–e6.10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Han H, Xie L, Liu R, Yang J, Liu F, Wu K, et al. Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):819–23. 10.1002/jmv.25809.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1986–94.10.1056/NEJMoa030685Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Al-Hameed F, Wahla AS, Siddiqui S, Ghabashi A, Al-Shomrani M, Al-Thaqafi A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus patients admitted to an intensive care unit in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Intensive Care Med. 2016;31(5):344–8.10.1177/0885066615579858Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Leung TW, Wong KS, Hui AC, To KF, Lai ST, Ng WF, et al. Myopathic changes associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome: a postmortem case series. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(7):1113–7.10.1001/archneur.62.7.1113Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Yuan J, Zou R, Zeng L, Kou S, Lan J, Li X, et al. The correlation between viral clearance and biochemical outcomes of 94 COVID-19 infected discharged patients. Inflamm Res. 2020;69(6):599–606.10.1007/s00011-020-01342-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Wong RS, Wu A, To KF, Lee N, Lam CW, Wong CK, et al. Haematological manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2003;326(7403):1358–62.10.1136/bmj.326.7403.1358Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2020 Yi-Hong Zhou et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Article

- MicroRNA-451b participates in coronary heart disease by targeting VEGFA

- Case Report

- A combination therapy for Kawasaki disease with severe complications: a case report

- Vitamin E for prevention of biofilm-caused Healthcare-associated infections

- Research Article

- Differential diagnosis: retroperitoneal fibrosis and oncological diseases

- Optimization of the Convolutional Neural Networks for Automatic Detection of Skin Cancer

- NEAT1 promotes LPS-induced inflammatory injury in macrophages by regulating miR-17-5p/TLR4

- Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 as prognostic biomarkers in critically ill patients

- Effects of extracorporeal magnetic stimulation in fecal incontinence

- Case Report

- Mixed germ cell tumor of the endometrium: a case report and literature review

- Bowel perforation after ventriculoperitoneal-shunt placement: case report and review of the literature

- Research Article

- Prognostic value of lncRNA HOTAIR in colorectal cancer : a meta-analysis

- Case Report

- Treatment of insulinomas by laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation: case reports and literature review

- Research Article

- The characteristics and nomogram for primary lung papillary adenocarcinoma

- Undiagnosed pheochromocytoma presenting as a pancreatic tumor: A case report

- Bioinformatics Analysis of the Expression of ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 3 (ABCC3) in Human Glioma

- Diagnostic value of recombinant heparin-binding hemagglutinin adhesin protein in spinal tuberculosis

- Primary cutaneous DLBCL non-GCB type: challenges of a rare case

- LINC00152 knock-down suppresses esophageal cancer by EGFR signaling pathway

- Case Report

- Life-threatening anaemia in patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome)

- Research Article

- QTc interval predicts disturbed circadian blood pressure variation

- Shoulder ultrasound in the diagnosis of the suprascapular neuropathy in athletes

- The number of negative lymph nodes is positively associated with survival in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients in China

- Differentiation of pontine infarction by size

- RAF1 expression is correlated with HAF, a parameter of liver computed tomographic perfusion, and may predict the early therapeutic response to sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients

- LncRNA ZEB1-AS1 regulates colorectal cancer cells by miR-205/YAP1 axis

- Tissue coagulation in laser hemorrhoidoplasty – an experimental study

- Classification of pathological types of lung cancer from CT images by deep residual neural networks with transfer learning strategy

- Enhanced Recovery after Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

- Case Report

- Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in an immunosuppressed adult

- Research Article

- The characterization of Enterococcus genus: resistance mechanisms and inflammatory bowel disease

- Case Report

- Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an unusual cause of abdominal pain in the upper gastrointestinal tract A case report

- Research Article

- microRNA-204-5p participates in atherosclerosis via targeting MMP-9

- LncRNA LINC00152 promotes laryngeal cancer progression by sponging miR-613

- Can keratin scaffolds be used for creating three-dimensional cell cultures?

- miRNA-186 improves sepsis induced renal injury via PTEN/PI3K/AKT/P53 pathway

- Case Report

- Delayed bowel perforation after routine distal loopogram prior to ileostomy closure

- Research Article

- Diagnostic accuracy of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry for the direct identification of clinical pathogens from urine

- The R219K polymorphism of the ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 1 gene and susceptibility to ischemic stroke in Chinese population

- miR-92 regulates the proliferation, migration, invasion and apoptosis of glioma cells by targeting neogenin

- Clinicopathological features of programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma

- NF2 inhibits proliferation and cancer stemness in breast cancer

- Body composition indices and cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes. CV biomarkers are not related to body composition

- S100A6 promotes proliferation and migration of HepG2 cells via increased ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53

- Review Article

- Focus on localized laryngeal amyloidosis: management of five cases

- Research Article

- NEAT1 aggravates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury by sponging miR-22-3p

- Pericentric inversion in chromosome 1 and male infertility

- Increased atherogenic index in the general hearing loss population

- Prognostic role of SIRT6 in gastrointestinal cancers: a meta-analysis

- The complexity of molecular processes in osteoarthritis of the knee joint

- Interleukin-6 gene −572 G > C polymorphism and myocardial infarction risk

- Case Report

- Severe anaphylactic reaction to cisatracurium during anesthesia with cross-reactivity to atracurium

- Research Article

- Rehabilitation training improves nerve injuries by affecting Notch1 and SYN

- Case Report

- Myocardial amyloidosis following multiple myeloma in a 38-year-old female patient: A case report

- Research Article

- Identification of the hub genes RUNX2 and FN1 in gastric cancer

- miR-101-3p sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer cells to irradiation

- Distinct functions and prognostic values of RORs in gastric cancer

- Clinical impact of post-mortem genetic testing in cardiac death and cardiomyopathy

- Efficacy of pembrolizumab for advanced/metastatic melanoma: a meta-analysis

- Review Article

- The role of osteoprotegerin in the development, progression and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms

- Research Article

- Identification of key microRNAs of plasma extracellular vesicles and their diagnostic and prognostic significance in melanoma

- miR-30a-3p participates in the development of asthma by targeting CCR3

- microRNA-491-5p protects against atherosclerosis by targeting matrix metallopeptidase-9

- Bladder-embedded ectopic intrauterine device with calculus

- Case Report

- Mycobacterial identification on homogenised biopsy facilitates the early diagnosis and treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis

- Research Article

- The will of young minors in the terminal stage of sickness: A case report

- Extended perfusion protocol for MS lesion quantification

- Identification of four genes associated with cutaneous metastatic melanoma

- Case Report

- Thalidomide-induced serious RR interval prolongation (longest interval >5.0 s) in multiple myeloma patient with rectal cancer: A case report

- Research Article

- Voluntary exercise and cardiac remodeling in a myocardial infarction model

- Electromyography as an intraoperative test to assess the quality of nerve anastomosis – experimental study on rats

- Case Report

- CT findings of severe novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A case report of Heilongjiang Province, China

- Commentary

- Directed differentiation into insulin-producing cells using microRNA manipulation

- Research Article

- Culture-negative infective endocarditis (CNIE): impact on postoperative mortality

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain syndrome

- Plasma microRNAs in human left ventricular reverse remodelling

- Bevacizumab for non-small cell lung cancer patients with brain metastasis: A meta-analysis

- Risk factors for cerebral vasospasm in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Problems and solutions of personal protective equipment doffing in COVID-19

- Evaluation of COVID-19 based on ACE2 expression in normal and cancer patients

- Review Article

- Gastroenterological complications in kidney transplant patients

- Research Article

- CXCL13 concentration in latent syphilis patients with treatment failure

- A novel age-biomarker-clinical history prognostic index for heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- Case Report

- Clinicopathological analysis of composite lymphoma: A two-case report and literature review

- Trastuzumab-induced thrombocytopenia after eight cycles of trastuzumab treatment

- Research Article

- Inhibition of vitamin D analog eldecalcitol on hepatoma in vitro and in vivo

- CCTs as new biomarkers for the prognosis of head and neck squamous cancer

- Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adipokine level of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rats fed high-fat diet

- 72 hour Holter monitoring, 7 day Holter monitoring, and 30 day intermittent patient-activated heart rhythm recording in detecting arrhythmias in cryptogenic stroke patients free from arrhythmia in a screening 24 h Holter

- FOXK2 downregulation suppresses EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma

- Case Report

- Total parenteral nutrition-induced Wernicke’s encephalopathy after oncologic gastrointestinal surgery

- Research Article

- Clinical prediction for outcomes of patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure associated with HBV infection: A new model establishment

- Case Report

- Combination of chest CT and clinical features for diagnosis of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia

- Research Article

- Clinical significance and potential mechanisms of miR-223-3p and miR-204-5p in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck: a study based on TCGA and GEO

- Review Article

- Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in noncirrhotic liver. A case report and systematic review

- Research Article

- Voltage-dependent anion channels mediated apoptosis in refractory epilepsy

- Prognostic factors in stage I gastric cancer: A retrospective analysis

- Circulating irisin is linked to bone mineral density in geriatric Chinese men

- Case Report

- A family study of congenital dysfibrinogenemia caused by a novel mutation in the FGA gene: A case report

- Research Article

- CBCT for estimation of the cemento-enamel junction and crestal bone of anterior teeth

- Case Report

- Successful de-escalation antibiotic therapy using cephamycins for sepsis caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia: A sequential 25-case series

- Research Article

- Influence factors of extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis

- Assessment of knowledge of use of electronic cigarette and its harmful effects among young adults

- Predictive factors of progression to severe COVID-19

- Procedural sedation and analgesia for percutaneous trans-hepatic biliary drainage: Randomized clinical trial for comparison of two different concepts

- Acute chemoradiotherapy toxicity in cervical cancer patients

- IGF-1 regulates the growth of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix deposition in pelvic organ prolapse

- NANOG regulates the proliferation of PCSCs via the TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

- An immune-relevant signature of nine genes as a prognostic biomarker in patients with gastric carcinoma

- Computer-aided diagnosis of skin cancer based on soft computing techniques

- MiR-1225-5p acts as tumor suppressor in glioblastoma via targeting FNDC3B

- miR-300/FA2H affects gastric cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis

- Hybrid treatment of fibroadipose vascular anomaly: A case report

- Surgical treatment for common hepatic aneurysm. Original one-step technique

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and caregivers’ burden in dementia

- Predictor of postoperative dyspnea for Pierre Robin Sequence infants

- Long non-coding RNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes cell proliferation, metastasis and EMT in glioma by sponging miR-506-5p

- Analysis of expression and prognosis of KLK7 in ovarian cancer

- Circular RNA circ_SETD2 represses breast cancer progression via modulating the miR-155-5p/SCUBE2 axis

- Glial cell induced neural differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Case Report

- Moraxella lacunata infection accompanied by acute glomerulonephritis

- Research Article

- Diagnosis of complication in lung transplantation by TBLB + ROSE + mNGS

- Case Report

- Endometrial cancer in a renal transplant recipient: A case report

- Research Article

- Downregulation of lncRNA FGF12-AS2 suppresses the tumorigenesis of NSCLC via sponging miR-188-3p

- Case Report

- Splenic abscess caused by Streptococcus anginosus bacteremia secondary to urinary tract infection: a case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Advances in the role of miRNAs in the occurrence and development of osteosarcoma

- Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of pleural empyema

- Effect of miRNA-200b on the proliferation and apoptosis of cervical cancer cells by targeting RhoA

- LncRNA NEAT1 promotes gastric cancer progression via miR-1294/AKT1 axis

- Key pathways in prostate cancer with SPOP mutation identified by bioinformatic analysis

- Comparison of low-molecular-weight heparins in thromboprophylaxis of major orthopaedic surgery – randomized, prospective pilot study

- Case Report

- A case of SLE with COVID-19 and multiple infections

- Research Article

- Circular RNA hsa_circ_0007121 regulates proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of trophoblast cells by miR-182-5p/PGF axis in preeclampsia

- SRPX2 boosts pancreatic cancer chemoresistance by activating PI3K/AKT axis

- Case Report

- A case report of cervical pregnancy after in vitro fertilization complicated by tuberculosis and a literature review

- Review Article

- Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum: Emergent epidemiological data and molecular pathways

- Research Article

- Biological properties and therapeutic effects of plant-derived nanovesicles

- Case Report

- Clinical characterization of chromosome 5q21.1–21.3 microduplication: A case report

- Research Article

- Serum calcium levels correlates with coronary artery disease outcomes

- Rapunzel syndrome with cholangitis and pancreatitis – A rare case report

- Review Article

- A review of current progress in triple-negative breast cancer therapy

- Case Report

- Peritoneal-cutaneous fistula successfully treated at home: A case report and literature review

- Research Article

- Trim24 prompts tumor progression via inducing EMT in renal cell carcinoma

- Degradation of connexin 50 protein causes waterclefts in human lens

- GABRD promotes progression and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer

- The lncRNA UBE2R2-AS1 suppresses cervical cancer cell growth in vitro

- LncRNA FOXD3-AS1/miR-135a-5p function in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells

- MicroRNA-182-5p relieves murine allergic rhinitis via TLR4/NF-κB pathway