Abstract

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic turned into a global crisis. Focusing on the deterioration in people’s mental health, we conducted two experiments, one in Germany and one in the UK, in January and February 2021, when both countries were in lockdown. Using a COVID-19-themed sentence completion task, we tested the direction of counterfactual thoughts in relation to egocentric (self-focused) versus non-egocentric (other-focused) perspective-taking. Results show that in both samples, more upward counterfactuals (mental simulation of better counterfactual worlds, relating to negative emotions) than downward counterfactuals (mental simulation of worse counterfactual worlds, relating to positive emotions) were produced in the egocentric condition. An opposite pattern was found in the non-egocentric condition. We conclude that emotions as expressed in counterfactual language are perspective-dependent.

1 Introduction

The state of global mental health dramatically deteriorated when the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) developed into a worldwide pandemic at the beginning of 2020 (Alzueta et al. 2020; Nikčević et al. 2021). In order to decrease the spread of the virus, governments imposed and reinforced regulations over long time periods. For instance, Germany and the United Kingdom implemented rules of social distancing, mask requirements, and lockdowns on public life from the beginning of 2020 (German Federal Government 2020a, b, 2021; UK Government 2020, 2021). Such drastic changes in social activity, work, and home life paired with the highly unpredictable nature of the virus increased negative emotional states, such as feelings of anxiety and symptoms of depression, in populations worldwide (Alzueta et al. 2020; Pandey et al. 2020; Racine et al. 2021; Schäfer et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2021).

Recent studies have found that changes of emotional well-being related to the pandemic are reflected in the language use of individuals. For instance, academic papers written during the pandemic contained more terms related to affect than those written before the outbreak, which suggests that writers were dealing with a crisis (Markowitz 2022). A longitudinal study described how narrative coherence was an enhancement factor to emotionally cope with stressful circumstances, such as the pandemic (Vanaken et al. 2022). Hence, language can be used to indirectly infer the emotional state and coping strategies of speakers or writers.

This raises the question of how other linguistic devices can be used to index emotional and cognitive processes. One example are the linguistic expressions of counterfactual thinking, which is a form of mental simulation. Counterfactual thoughts as reflected in language typically represent a juxtaposition to reality.

Among other forms, while talking about counterfactual thoughts, one often appeals to conditional sentences of the form If P, then Q, to express one’s belief in the consequent proposition Q supposing the truth of the antecedent proposition P (Liu 2019, 2022). Sentences such as (1) are referred to as indicative conditionals and those in (2) are subjunctive or counterfactual conditionals (von Fintel 2012). Unlike indicative conditionals, which typically consider possible situations, counterfactual conditionals consider alternative situations that are contrary to the facts, as illustrated in (2a) and (2b).

| If the sky is overcast in the morning, there will be rain in the afternoon. |

| If the sky had been overcast in the morning, there would have been rain in the afternoon. |

| Factual situation: The sky was not overcast in the morning; there was no rain in the afternoon. |

| Counterfactual situation: The sky was overcast in the morning; there was rain in the afternoon. |

Counterfactual conditionals such as (2) are used to explore alternative outcomes (Sanna 2000; White and Lehman 2005), and have been an important area of interest for psychology of reasoning. If P, Q are statements which causally link two events or actions with each other (Roese and Epstude 2017). Through the process of mental simulation, an infinite set of such alternative events are possible. Since simulation is storage- and time-costly, certain aspects of reality, such as temporal relation, controllability, and expectability (or, following McCloy and Byrne (2000), exceptionality), restrict the set of events under consideration (Byrne 2015, 2002; McCloy and Byrne 2000; Van Hoeck et al. 2015). As a result, the chosen events or actions P for the form if P, Q reflect the alternative which matches best to these aspects, and thus has the strongest perceived significance leading to the outcome Q in the consequent (McCloy and Byrne 2000; Van Hoeck et al. 2015). In formal linguistics and analytical philosophy, different analyses have been under discussion for the semantics of counterfactuals; for example, on the similarity analysis, a counterfactual sentence if P, Q is true in the world of evaluation (w 0) if all the P-worlds most similar to w 0 are Q-worlds (Lewis 1973; Starr 2022). That is, (2) is true if all the worlds with the sky being overcast in the morning while being most similar to the actual world (where it was not) are worlds with rain in the afternoon.

As a central feature of human cognition, mental simulation, such as counterfactual thinking, associates with individuals’ emotional states and their coping strategies (Epstude and Roese 2008; Sanna 2000). Thus, counterfactuals are not only relevant for the psychology of reasoning, linguistics, and philosophy, but also for the psychology of emotion. The direct comparison between reality and the alternative event stresses the required conditions for improving or worsening the outcome (Broomhall et al. 2017; Epstude and Roese 2008), which is used to differentiate counterfactuals into two types (Markman et al. 1993). Upward counterfactuals involve mental simulation of better counterfactual worlds than reality, as seen in (3); downward counterfactuals involve mental simulation of counterfactual worlds worse than reality, as seen in (4) (Allen et al. 2014; Broomhall and Phillips 2018; Broomhall et al. 2017; Byrne 2002; Epstude and Roese 2008; Sanna 2000; White and Lehman 2005).

| If I had worked harder, I would have gotten my dream job. (upward) |

| If I had worked harder, I would have been too exhausted to spend time with my family. (downward) |

As (3) and (4) show, the same antecedent (P) can result in different directions of the counterfactual sentence. The speaker of (3) indicates that in a world where they had worked harder, they also would have reached their most favorable goal of getting the job (Q). In contrast, the same antecedent would result in a less favorable outcome for the speaker of (4); thus, this alternative world would be worse for the speaker. The directionality of the counterfactual thought depends on the causal relationship between the antecedent and the consequent, reflected in the mental simulation of an agent. This causal relationship can also have an impact on the resulting emotions. Accordingly, comprehenders can rely on the desirability of the consequent (Q) to infer about that of the antecedent (P) and of the simulated world of P and Q; subsequently, they can understand the agent’s emotion. Upward counterfactuals, due to the contrast between the actual world versus a better counterfactual world, evoke negative emotions, such as regret and shame; downward counterfactuals, due to the contrast between the actual world versus a worse counterfactual world, evoke positive emotions, such as relief. That is, the labels of upward and downward counterfactuals are based on the direction of counterfactual reasoning rather than the distinction between positive or negative emotions, which admittedly can be counterintuitive for the reader who encounters this terminology for the first time.

During the COVID-19 pandemic and ever since, newspaper articles frequently have employed counterfactual sentences to explore different outcomes of the pandemic. The quoatation in (5) is an example of an upward counterfactual, relating to a negative affect, while (6) an example of a downward counterfactual, relating to a positive affect.

| The number of coronavirus deaths in the UK could have been halved if the government had introduced the lockdown a week earlier … |

| (Stewart and Sample 2020) |

| If COVID had not happened, we would not have all the infrastructure that we have. |

| (CapRadio 2022) |

Both types of counterfactual thoughts have specific functions related to behavior and affect regulation. Upward counterfactuals focus on the problem at hand that influenced the conceivably unwanted outcome; they can thus have an impact on future behavior in terms of performance improvement (Roese and Epstude 2017; White and Lehman 2005). Moreover, in the case of upward counterfactuals, the perspective can reveal the direction of responsibility (Broomhall et al. 2017); when taking an egocentric (self-focused, according to Epstude and Roese 2008) perspective, the learning effect is additionally enhanced by reflecting on self-improvement in contrast to non-egocentric (other-focused) perspectives (Epstude and Roese 2008; Roese and Epstude 2017).

Experimental evidence has shown that generally more upward counterfactuals are produced than downward counterfactuals, suggesting that the performance-improvement function is more often employed (Summerville and Roese 2008). It has also been shown that the self-improvement function (namely upward counterfactuals with self-referent) predominates over downward counterfactuals (Allen et al. 2014; Epstude and Roese 2008; Summerville and Roese 2008). As for downward counterfactuals, no difference in the use of self- or other-focus has been found, unlike with upward counterfactuals (Epstude and Roese 2008).

Besides behavior improvement, upward counterfactuals also serve a preparatory function (Eisma et al. 2020; Roese and Epstude 2017; White and Lehman 2005). The contrast between a more favorable alternative outcome and reality causes negative affect, which serves as potential motivation for future behavior (Medvec et al. 1995). Thus, upward counterfactuals serve as a problem-focused coping mechanism and enable a learning process from past events to regulate future behavior under the cost of amplifying the current negative affect (Allen et al. 2014; White and Lehman 2005). While upward counterfactuals occur more frequently after situations in which the outcome was changeable, downward counterfactuals appear more frequently when the outcome was inevitable (Epstude and Roese 2008) or caused a high level of stress (White and Lehman 2005). Here, the focus lies on emotion-focused coping: from the experience of an unfavorable outcome, positive emotions, such as relief, arise by imagining a worse alternative (Allen et al. 2014; Broomhall and Phillips 2018; Byrne 2002; Epstude and Roese 2008; Sanna 2000; Van Hoeck et al. 2015; White and Lehman 2005). They thus reduce negative emotions and serve an affective function (Byrne 2002; Eisma et al. 2020; Epstude and Roese 2008; Roese and Epstude 2017; White and Lehman 2005). In terms of behavior regulation, downward counterfactuals imply the preservation of the status quo since the event or one’s own actions were good enough (Epstude and Roese 2008).

Experimental evidence with Olympic athletes confirmed this tendency (Medvec et al. 1995). Participants were shown videotapes of interviews with bronze and silver medalists from the Olympic Games in 1992 and rated how much they are perceived to focus on what could have gone worse (downward) and how much on how they could have done better (upward). Silver medalists were found to focus more on upward thoughts than winners of the bronze medal. In addition, participants judged whether the athletes’ thoughts focused on (i) downward counterfactual scenarios compared to competitors who finished behind them (downward comparison), (ii) upward counterfactuals in comparison to competitors who finished ahead (upward comparison), or (iii) their own accomplishment without engaging in comparison with others (neutral no comparison). Downward counterfactual thoughts were rated as less frequent in both medalists. Here, silver medalists were found to focus more on upward comparisons than bronze medalists. The latter were rated to engage in more self-focused thoughts (neutral no comparison) than silver medalists.

Similar results were found in a study from the Olympic Games in 2016 (Allen et al. 2019). Participants were shown static photos of the athletes, and similarly, they rated silver medalists to express more counterfactuals in general, particularly in the upward direction. The authors concluded that the extent of counterfactual thought correlates with relative height on the podium; silver medalists focus on the failure of not winning a gold medal, which could potentially serve as a motivation to improve their performance.

The coping effect of counterfactual thinking has been experimentally studied in the context of depression and anxiety. A longitudinal study with participants who had experienced the loss of a family member in the past three years showed a correlation between the type of counterfactual used as well as the perspective taken (the egocentric perspective “I” or non-egocentric perspective involving other people) and depression. While downward counterfactual use was not found to associate with depression symptoms, both other and self-referent upward counterfactuals related to depression and longitudinal depression symptoms. Thus, focusing on one’s own actions in the context of loss increases self-blame and guilt (Eisma et al. 2020). Predominant upward counterfactual thinking was also found in individuals with anxiety symptoms, such as women who experienced a miscarriage (Callander et al. 2007). Moreover, meta-analyses suggest there is a reliable relationship between negative affect, such as depression, and the extensive use of upward counterfactuals in general (Allen et al. 2014; Broomhall et al. 2017; Epstude and Roese 2008).

While coping mechanisms, such as counterfactual thinking, appear in everyday life, a global pandemic that has caused the most deaths since the Spanish flu represents an extraordinary situation. Due to the pandemic, negative emotions were reported as being more central to individuals’ emotive states in general (Whiston et al. 2022). Studies from the very start of the pandemic suggested a deterioration in mental health, such as severe distress causing depression and anxiety symptoms as a result of isolation measures imposed by governments (Alzueta et al. 2020). However, some demographic characteristics (e.g., young age, female gender, higher country income classification), and certain personality traits (for example, neuroticism, a disposition to experience negative affects such as anger, anxiety, emotional instability, and depression; Widiger and Oltmanns 2017) proved to be risk factors for a stronger decrease in mental health (Alzueta et al. 2020; Nikčević et al. 2021). In a global survey study with participants from 59 countries worldwide (Alzueta et al. 2020), the authors used, among others, the Epidemic-Pandemic Impact Inventory (EPII; Grasso et al. 2020) and the 21-item subset of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995b). Most participants reported normal anxiety symptoms (80.5 %) and mild depression symptoms (74.6 %). Both symptoms correlated with being female, young, and from a country classified with higher income, among other factors; thus, subjects with these characteristics were more likely to report high depression and anxiety levels. In terms of the effect of age, younger adults could potentially be more exposed to COVID-19-related media, be more affected by financial instability, and might have less efficient coping mechanisms than older adults. Moreover, the authors found evidence that the level of negative affect was robustly predicted by COVID-19-related effects on private life.

In a related way, certain personality traits were shown to affect an individual’s experience of negative affect during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nikčević et al. 2021). High levels of neuroticism were assumed to be a vulnerability factor, increasing the level of experienced negative affect. Extraversion and conscientiousness were assumed as possible protective factors, thus reducing the risk of experiencing negative affect. In a survey study (Nikčević et al. 2021) using among other instruments, the 10-item subset of the Big Five Inventory survey (BFI-10; Rammstedt et al. 2012), the results showed that high generalized anxiety and depression levels are predicted by certain personality traits and age. Personality traits, such as extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, related negatively with generalized anxiety; thus, the higher their scores, the lower the anxiety level. Neuroticism was found to positively relate to general anxiety and is directly connected to COVID-19-related anxiety and high depression levels. Moreover, younger age was found to associate with higher levels of anxiety. Nikčević et al. concluded that neuroticism acts as a vulnerability factor for generalized and COVID-19-related anxiety, while conscientiousness was confirmed as a protective factor. Additionally, agreeableness and extraversion highly predicted low COVID-19-related anxiety symptoms. Nikčević et al. suggested that these traits might favor certain coping mechanisms which alleviate emotional distress.

Outside the context of the pandemic, certain personality traits have also been reported to be associated with a predominant use of a certain counterfactual direction. For instance, neuroticism has been found to positively relate to upward counterfactuals (Allen et al. 2014; Ardakani et al. 2015), while high levels of extraversion and openness lead to less frequent use of upward counterfactuals (Allen et al. 2014).

In the current study, we were originally interested in (i) the relationship between counterfactual thinking and perspective-taking in general, and (ii) how counterfactual thought processes relate to personality traits, emotional states, and the perceived situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a post hoc power analysis we ran shows that the study was underpowered for (ii). Due to the nature of the study, further data collection is not possible; thus, we only provide the descriptive statistics of the data for (ii) in the appendix. In the following, we will report the details of (i).

Based on the literature, then, upward counterfactuals are used more frequently than downward counterfactuals due to their improvement function and use as a problem-focused coping mechanism, while upward counterfactuals appear more frequently with self-reference. Thus, we hypothesized that the direction of counterfactuals relates to the perspective-taking in such sentences. In order to test this, we assessed counterfactual thinking with a COVID-19-themed sentence completion task in Germany and the UK. The pandemic served as a common topic which led to similar influences on people’s lives in both countries due to similar regulations (i.e., lockdown, mask requirements) during the time of data collection. More specifically, we had the following hypotheses:

H1:

In general, more upward counterfactuals will be produced than downward counterfactuals.

H2:

In the egocentric perspective, more upward counterfactuals will be produced than downward counterfactuals.

Furthermore, we investigated for exploratory purposes whether the number of upward and downward counterfactuals differ in the non-egocentric condition.

2 Methods

2.1 Experiment 1: German study

2.1.1 Participants

Data collection took place at the beginning of January 2021. We recruited 101 participants (41 female, 59 male, 1 nonbinary) from across Germany. The data of two participants were excluded (one due to not meeting the requirement of being a native speaker of German and the other due to not reporting their age). We received informed consent from all participants. Participants’ mean age was 30 years (SD = 10.37, range 18–65 years).

2.1.2 Materials

We used the German translation of standard test batteries and a completion task. For the assessment of personality traits, we used the 10-item Big Five Inventory questionnaire (BFI-10; Rammstedt et al. 2012; Rammstedt and John 2007), similar to Nikčević et al.’s (2021) study. The emotional states were assessed with the 21-item subset of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995b). The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the participants’ personal life were measured with the help of a 10-item subset of the Epidemic and Pandemic Impact Inventory (EPII; Grasso et al. 2020), similar to Alzueta et al.’s (2020) study. It included the following sectors: infection history, work and employment, economics, home life, and social activities.

The completion task was based on a one-factorial design, where the factor egocentricity had two levels (egocentric vs. non-egocentric). We generated 12 COVID-19-themed critical items with the following structure: a context sentence (S1) starting with Wegen Corona…‘Because of corona…’, the antecedent of a counterfactual conditional (S2), and the personal pronoun plus an auxiliary verb of the consequent (S3), suggesting the structure of Wenn P, Q ‘If P, Q’. Thereby, the pronouns expressed the two conditions in (S3): in the egocentric condition, ich ‘I’ was used, whereas in the non-egocentric condition, the sentence started with die Leute ‘the people’. See (7) for an example of the stimuli.

| Context |

| Wegen Corona befindet sich Deutschland in einem zweiten Lockdown. |

| because of corona finds itself Germany in a second lockdown |

| ‘Because of the coronavirus, Germany is under a second lockdown.’ |

| Antecedent |

| Wenn die Pandemie nicht gewesen wäre, |

| if the pandemic not have been would subj |

| ‘If the pandemic had not happened,’ .̧ |

| Consequent | ||

| egocentric | hätte | ich … |

| would have I | ||

| ‘I would …’ | ||

| non-egocentric | hätten | die Leute … |

| would have the people | ||

| ‘the people would …’ | ||

All the antecedent clauses used perfect plus subjunctive mood (e.g., Wenn die Restaurants geschlossen worden wären ‘If the restaurants had been closed’), that is, they took the form of past subjunctive to ensure counterfactual meanings – this was a conscious choice to avoid the potential confound that present subjunctive in comparison (e.g., Wenn die Restaurants geschlossen wären ‘if the restaurants were closed’) is not necessarily counterfactual (Iatridou 2000; Ippolito 2003; von Fintel and Iatridou 2023). The counterfactuality of the antecedent proposition for past subjunctive has also been under debate (Anderson 1951; Zakkou 2019). In our paper, we follow Arregui and Biezma (2016: 6) in assuming that counterfactuality in past subjunctive conditionals cannot be canceled “for no reason”.

In the antecedents of the 12 items, half used the auxiliary verb sein ‘be’ and the other half haben ‘have’. In the consequent, the auxiliary verb varied in a balanced way between hätte ‘would have’, könnte ‘could have’, and wäre ‘would have/be’, allowing diverse sentence completions (see the Supplementary materials for a complete list of the experimental materials).

As distractors, we used 24 additional items with a similar structure to the critical items; they revolved around everyday topics, such as work, leisure, and the household.

2.1.3 Procedure and data acquisition

The experiment was implemented online (https://farm.pcibex.net/) with the PennController for Internet Based Experiments (Zehr and Schwarz 2018). Participants were recruited through the online crowdsourcing platform Prolific (https://www.prolific.co/) and they received monetary compensation for their participation. The experiment took roughly 25 min. After providing their informed consent, participants reported demographics, such as their age, their gender, information on their language background (native, second, and dominant languages, and languages their parents speak), the country they grew up in, and the country and region where they currently reside. Short instructions, including example questions with the answer possibilities, were shown before each part of the survey started, in order to familiarize participants with the task at hand. The order of the questions in every section of the survey was randomized. The survey parts came in the order in which we present the following subsections.

2.1.3.1 Personality traits

As suggested by the original survey (BFI-10; Rammstedt and John 2007), participants were asked to judge to what extent each statement (e.g., item 6: Ich gehe aus mir heraus, bin gesellig. ‘I am outgoing, sociable.’) applied to them (“Inwieweit trifft die folgende Aussage auf Sie zu?” [‘To what extent does the following statement apply to you?’]; see Rammstedt et al. 2012: 30). The judgment was given on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1, “trifft ’́uberhaupt nicht zu” [‘does not apply at all’], to 5, “trifft voll und ganz zu” [‘fully applies’]).

2.1.3.2 Completion task

Participants completed two practice sentences. Critical items and fillers were presented in a random order. The context sentences (S1) appeared centrally on the screen. Participants confirmed that they had read the sentence by clicking on the button “weiter” (‘next’); while (S1) remained on the screen, the antecedent (S2) appeared together with the consequent (S3) and an input box. Participants were asked to type the completion of the sentence in the box and to confirm again by clicking on “weiter”. The critical items were distributed into two lists which were implemented in separate studies on the platform to ensure counterbalancing. Participants could only take part in one study.

2.1.3.3 Emotional state

Participants judged to what extent the statements (e.g., item 12: ‘Ich fand es schwierig, mich zu entspannen.’ ‘I found it difficult to relax.’) applied to them in the past week (“Wie sehr trifft die Aussage w’́ahrend der letzten Woche auf Sie zu?”). The original survey consisted of a 4-point scale (see Lovibond and Lovibond 1995a, b; Psychology Foundation of Australia 2021). We used a 5-point scale instead, in order to keep consistency with the judgment scale used for the measure of personality traits.

2.1.3.4 COVID-19 situation

Participants were asked to indicate changes since the coronavirus pandemic started by providing binary answers (“ja” [‘Yes’] or “nein” [‘No’]) to prompts such as ‘laid off from job or had to close own business’ and ‘increase in workload or work responsibilities’ (Grasso et al. 2020).

2.1.4 Data analysis

The conditional consequents that were produced were manually classified into upward, downward, or neutral. To ensure a homogeneous classification in both studies, a general classification schema for each item was developed. Ungrammatical completions and neutral counterfactuals were removed. Examples of sentences and our classifications are given in (8).

| Wenn der Lockdown nicht gewesen wäre, wäre ich in besserer mentaler Verfassung. (upward, egocentric) |

| ‘If the lockdown had not been implemented, I would have been in better mental condition.’ |

| Wenn Homeoffice nicht möglich gewesen wäre, könnten die Leute sich nicht effektiv gegen den Virus schützen. (downward, non-egocentric) |

| ‘If working from home had not been possible, the people would have not been efficiently protected from the virus.’ |

| Wenn die Pandemie nicht gewesen wäre, hätte ich trotzdem geschlafen. (neutral) |

| ‘If the pandemic had not happened, I would have slept nevertheless.’ |

| ∗Wenn die Regierung nicht reagiert hätte, wäre ich Anzahl der Toten höher. (ungrammatical) |

| ∗‘If the government not reacted had, would I number of dead higher.’ |

The entire analysis was done with the software R (R Development Core Team 2020) and, for the analysis with generalized linear and mixed models, the package lme4 (Bates et al. 2020). The statistical analysis comprised two steps. First, we conducted a Poisson regression using generalized linear models.[1] This model (model 1) included the frequency of counterfactual type per participant as dependent and the counterfactual type as independent variable. The factor counterfactual type was sum coded with upward counterfactuals coded positively (0.5) and downward counterfactuals negatively (−0.5). Second, we constructed two binomial generalized linear mixed models with a logit-link function with counterfactual type as the dependent and either egocentric (model 2a) or non-egocentric (model 2b) as the independent variable. We used treatment coding for the counterfactual type (downward: 0, upward: 1) and the perspective condition (model 2a: egocentric = 1, non-egocentric = 0; model 2b: non-egocentric = 1, egocentric = 0). We applied the most parsimonious model approach (Bates et al. 2018) for the random effect structure and compared models with increasing complexity. Singular fitted or non-converging models were not further used for the analysis. The resulting models which fit the data best after testing the possible combinations are indicated in the respective results section. For the interpretation, the intercept and estimator are transformed from the log-odds space into probabilities. For models of both analysis steps, p values were obtained with the help of log-likelihood ratio test comparisons of nested models.

The procedure for calculating the scores and the descriptive statistics for the other measures can be found in the appendix.

2.2 Experiment 2: English study

Experiment 2 was conducted analogously to Experiment 1, with the test materials translated into English. Due to language contrasts, the English materials all used the form of If … had not (past participle), I/we would have… (see the Supplementary materials for a complete list of the experimental materials). Otherwise, the material and procedure remained similar, and the following only focuses on aspects that differ from the study in Section 2.1.

2.2.1 Participants

The data was collected simultaneously to the German experiment, in January to February 2021, on Prolific. In total, 101 participants from across the UK took part in the experiment (77 female, 23 male, 1 nonbinary). The data of three participants was removed, due to not meeting the language requirement. The mean age of the remaining 99 participants was 34 years (SD = 12.35, range 18–65 years).

3 Results

3.1 Experiment 1

In the dataset of the sentence completion task, 10 sentence completions were ungrammatical, and 160 counterfactuals were classified as neutral: 108 were egocentric sentence completions, 52 non-egocentric ones. One can raise the question why there were more egocentric ones who were neutral, which we are unable to answer in the current study. In total, 16 % of the 1212 sentences were removed. Thus a sample of 1018 counterfactual sentences entered further analysis (see Table 1 and Figure 1 for an overview).

Number of counterfactual sentences analyzed in Experiment 1, categorized by type of conditional and perspective. The values in parentheses represent the percentage in comparison to the total dataset.

| Perspective | Type of conditional | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upward | Downward | ||

| Egocentric | 317 (31.1 %) | 162 (15.9 %) | 479 |

| Non-egocentric | 262 (25.7 %) | 277 (27.2 %) | 539 |

| Total | 579 | 439 | 1,018 |

Results of the sentence completion task of Experiment 1 (Germany) and Experiment 2 (UK) in comparison. The x-axis shows the counterfactual types. The y-axis depicts the number of upward and downward counterfactuals produced, and their percentages with respect to the specific dataset provided in the bars.

The results of the models 1, 2a, and 2b are depicted in Table 2. First, the Poisson regression revealed a significant difference between the number of upward and downward counterfactuals, in that there were more upward counterfactuals (model 1:

Output of the analysis for Experiment 1 using generalized linear models for a Poisson regression (model 1), and generalized linear mixed models for a binomial regression with logit-link function (model 2a/b).

| Fixed effects | Model comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate |

|

Std. error | z Value | χ 2(1) | p Value | |

| Model 1 | Intercept | 1.50 | 0.05 | |||

| Type | 0.28 | 0.06 | 4.37 | 19.32 |

|

|

| Model 2a | Intercept | −0.09 | 0.44 | −0.21 | ||

| Egocentric | 1.48 | 0.40 | 3.66 | 9.52 | 0.002 | |

| Model 2b | Intercept | 1.03 | 0.55 | 1.87 | ||

| Non-egocentric | −1.19 | 0.18 | −6.69 | 46.71 |

|

|

Second, for model 2a of the binomial regression, the model with random subject as well as item intercepts with random slopes for the egocentric perspective fit the data best. The result showed that the odds ratio of producing upward counterfactuals was significantly different in the egocentric versus non-egocentric perspective (model 2a:

For model 2b, the model with random subject as well as item intercepts fit the data best. The result showed that the odds ratio of producing upward counterfactuals was significantly different in the non-egocentric versus egocentric perspective (model 2b:

3.2 Experiment 2

In the British dataset, 1200 sentence completions were collected: 11 were ungrammatical and 242 were neutral, making 24.2 % of the sentences; these were removed. Thus a sample of 910 counterfactual sentences entered further analysis (see Table 3 and Figure 1 for an overview).

Number of counterfactual sentences analyzed in Experiment 2, categorized by type of conditional and perspective. The values in parentheses represent the percentage in comparison to the total dataset.

| Perspective | Type of conditional | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upward | Downward | ||

| Egocentric | 272 (29.9 %) | 151 (16.6 %) | 423 |

| Non-egocentric | 212 (23.3 %) | 275 (30.2 %) | 487 |

| Total | 484 | 426 | 910 |

The results of the models 1, 2a, and 2b are depicted in Table 4. First, the Poisson regression revealed no significant difference between the number of upward and downward counterfactuals (model 1:

Output of the analysis for Experiment 2 using generalized linear models for a Poisson regression (model 1), and generalized linear mixed models for a binomial regression with logit-link function (model 2a/b).

| Fixed effects | Model comparison | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate |

|

Std. error | z Value | χ 2(1) | p Value | |

| Model 1 | Intercept | 1.48 | 0.05 | 30.54 | ||

| Type | 0.13 | 0.07 | 1.92 | 3.70 |

|

|

| Model 2a | Intercept | −0.42 | 0.42 | −0.99 | ||

| Egocentric | 1.19 | 0.18 | 6.69 | 46.58 |

|

|

| Model 2b | Intercept | 0.77 | 0.43 | 1.79 | ||

| Non-egocentric | −1.19 | 0.18 | −6.69 | 46.58 |

|

|

Second, for model 2a of the binomial regression, the model with random subject as well as item intercepts fit best the data. The result showed that the odds ratio of producing upward counterfactual was significantly different in the egocentric versus non-egocentric perspective (

For model 2b, the model with random subject as well as item intercepts fit best the data. The result showed that the odds ratio of producing upward counterfactuals was significantly different in the non-egocentric versus egocentric perspective (

4 Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between counterfactual thoughts, emotions, and perspective-taking during a real-life crisis (the COVID-19 pandemic). We ran two experiments, in Germany and in the UK, which had similar restrictions on people’s day-to-day life during the time of data collection. More specifically, experimental participants read COVID-19-themed scenarios containing an incomplete conditional sentence, with the conditional antecedent establishing a counterfactual situation in which the pandemic itself did not happen or certain, pandemic-related regulations were not in place. Using the sentence completions that were produced, we tested whether and how counterfactual direction (i.e., upward or downward) relates to the perspective-taking (i.e., egocentric or non-egocentric) of the statement.

The results showed that a significantly higher number of upward than downward counterfactuals were produced in the German dataset, while there was no such difference in the English dataset. Thus, hypothesis H1 was only partially confirmed. With regard to perspective manipulation, we found converging evidence. In both datasets, we found an effect in that more upward than downward counterfactuals were produced in the egocentric condition. This confirms our hypothesis H2, providing experimental evidence for the related claim in the literature. Furthermore, we found in both datasets that fewer upward counterfactuals were produced than downward counterfactuals in the non-egocentric condition.

Overall, our findings provide an interesting insight into the influence of perspective on counterfactual thoughts and emotions. Even though there was no significant difference between the number of upward and downward counterfactuals in the UK dataset in contrast to the German data, the direction of counterfactual thoughts is similarly perspective-dependent across both datasets, showing a significant upward versus downward difference of opposite distribution in the egocentric versus non-egocentric condition. People produced more upward than downward counterfactuals when they talked about themselves and fewer upward counterfactuals when they talked about others.

The finding that people engaged in more egocentric upward counterfactual thinking reveals that the pandemic caused severe changes in people’s habits and plans. In the datasets, people more often reported on what they missed out on because of regulations than on positive aspects. Example (9) from Experiment 2, the British dataset, shows a contrast between upward and downward counterfactuals. While (9a) focuses on the impression that there was nothing to appreciate, (9b) shows that even in such a crisis, the person found a positive aspect which supposedly would not have happened without a pandemic. Moreover, example (10) shows how emotive words are used in the context of the pandemic. While the upward counterfactual in (10a) shows how the lockdown in Germany had an emotional impact on the participant in a negative way, the downward counterfactual in (10b) shows how the participant would have been negatively effected if measures had not been imposed.

| If the pandemic had not happened, I would have … |

| loved life more. (upward) |

| not taken the time to appreciate the little things that matter in life. (downward) |

| Wenn der Lockdown nicht gewesen wäre, wäre ich … |

| ‘If it hadn’t been for the lockdown, I would’ |

| glücklicher gewesen. (upward) |

| have been happier. |

| gestresster gewesen. (downward) |

| have been more stressed. |

Before we finish the paper, we would like to briefly address the scope and limitations of the current study. Firstly, the classification of the counterfactuals into upward and downward was done manually and is thus at least partially subjective. In future work, asking participants after they complete a sentence whether it represents an improvement of the situation, or, as was done in the study by White and Lehman (2005), for the reasons behind those thoughts, could further improve the results and avoid the removal of numerous neutral sentences. Secondly, our items related to situations which were not in the control of the participants; for example, whether or not the pandemic happened was out of the control of the individual. Given that the comparison between controllable and uncontrollable events did not form part of our experimental design, this requires further research. Thirdly, there might be more constraints on the causal relation between the antecedent and the consequent proposition in the mental simulation. The emotional valence of an antecedent proposition might have an effect on the sentence continuation: for example, Wenn die Pandemie nicht gewesen wäre ‘If the pandemic had not happened’ (item 1) might more strongly prime upward completions (due to the negative nature of the pandemic), relating to negative emotions. In contrast, Wenn Homeoffice nicht möglich gewesen wäre ‘If working from home had not been possible’ (item 2) might more strongly prime downward completions (possibly, due to the positive connotation of the modal verb möglich in a “permission” reading), relating to positive emotions. For exploratory purposes, we looked at the descriptive statistics of the items for both the German and the UK study. They show that for item 1, there were 80 upward and 8 downward counterfactuals in the German study and 74 upward and 12 downward counterfactuals in the UK study. For item 2, there were 15 upward and 70 downward counterfactuals in the German study and 37 upward and 48 downward counterfactuals in the UK study. As the counts are our measure, we are not able to draw conclusions about the nature of the antecedent propositions used in the items. Due to the time-sensitivity of the present study, we will leave this aspect to be considered in future research of similar kinds, which can include, for example, a norming pretest about the emotional valence of the antecedent propositions (positive vs. negative).

With these limitations taken into consideration, our study used a factorial design with strictly controlled contexts, in contrast with previous studies using open production measures such as sentence production in interviews (see Medvec et al. 1995; White and Lehman 2005). The main finding of the study is that more upward counterfactuals indicating negative emotions were produced in egocentric perspective-taking; this provides convergent evidence for previous research in this regard. The opposite pattern in the non-egocentric perspective that the study found has not been reported previously to our knowledge. Last but not least, in the realm of conditionals, researchers have related optatives (e.g., If only I had caught the train!) to expressing speaker emotions such as regret about having not caught the train in this case (Grosz 2012). Our study provides empirical evidence that not only optatives but also regular counterfactual conditionals can signal speaker emotions.

5 Conclusions

To sum up, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected our life drastically since it started in 2020; approaches to deal with it differed, however, from country to country, and from person to person. Focusing on the deteriorating mental health in the population, we conducted a study in the UK and Germany at a critical point in time when both countries were in lockdown. We used a sentence completion task to measure the direction of counterfactual thoughts in egocentric and non-egocentric sentence contexts. Results show that in both samples, the direction of counterfactuals, as the index of direction of emotions, is perspective-dependent, in that more upward counterfactuals (relating to negative emotions) were found in the egocentric condition, with fewer upward than downward counterfactuals in the non-egocentric condition. We conclude that the direction of counterfactual thinking is perspective-dependent. We hope that the method we developed is applicable and extendable to access counterfactual language, thoughts, and emotions in general.

Supplementary Materials (data availability statement)

The datasets and code files generated for this study are available on the OSF repository: https://osf.io/tyh8p/.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: SPP1727/367088975, SFB1412/416591334

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Isabell Wartenburger and Ursula Hess for their very valuable comments, and Juliane Schwab for advice on data analysis.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – SFB 1412, 416591334; SPP 1727, 367088975.

-

Author contributions: M.L. conceived the study. M.L. and S.R. designed the study together and both made substantial contributions to the paper. S.R. conducted the experiments and the data analyses; both authors were responsible for the interpretation of the data. S.R. prepared the first draft of the manuscript, with revisions from M.L. M.L. provided funding, project administration, and resources.

-

Competing interests: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

A Appendix

A.1 On the other measures in the study

In the current study, we were originally also interested in how counterfactual thought processes relate to personality traits, and emotional states, as well as the perceived situation during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a post hoc power analysis we ran showed that the study was underpowered for this. For the interested reader, we provide the descriptive statistics of the data here.

A.1.1 Data analysis

A.1.1.1 Scores

We followed the procedure of the original study for the personality score (Rammstedt and John 2007) and calculated a mean per dimension per participant. Thus, a high score is associated with a higher manifestation of the Big Five dimension. As for the COVID-19 situation score, we summed over the questions answered with yes per participant per domain. For the analysis, we summed over all domains per participant to obtain a total score. Therefore, a high value is associated with a higher degree of life changes due to the pandemic. For the emotional state measurement, we transformed the judgment from a 5-point to a 4-point scale to ensure that the classification into severeness of symptoms applies. The score was obtained as a mean per section for anxiety, depression, and stress per subject. We used the original classification of the mean scores into normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme. As for the completion task, the consequents of the conditional sentences were manually classified (see Section 2.1.4). Per subject, we compiled upward counterfactuals coded positively (+1) and downward counterfactual coded negatively (−1) to obtain a score which indicates the direction of the counterfactual thought (CFT score). Given the 12 items, the score had a possible range between −12 and 12. As neutral and ungrammatical counterfactuals were removed, the individual score was divided by the total number of valid counterfactuals for the particular subject. Hence, the algebraic sign of the score indicates the direction of the counterfactuals: a positive sign is associated with more upward counterfactuals, while a negative sign indicates more frequent use of downward counterfactuals.

A.2 Results

A.2.1 Experiment 1

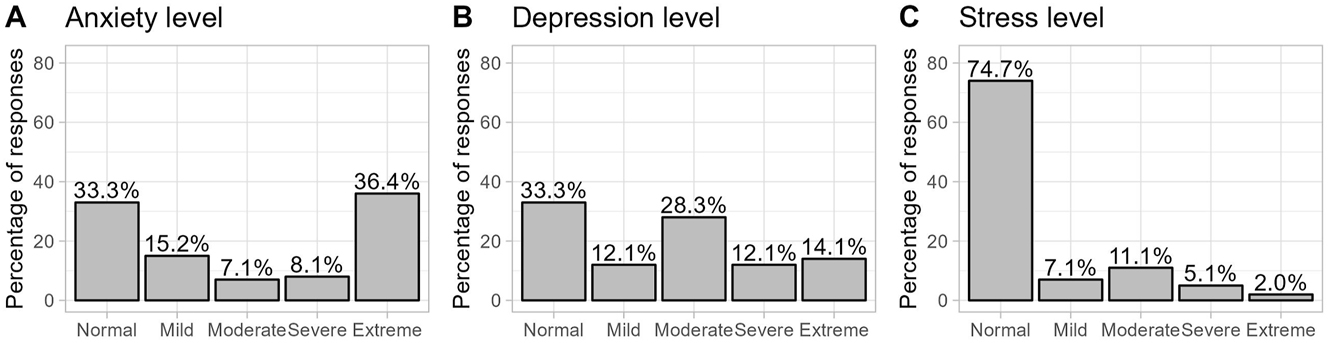

Descriptive statistics of the scores are provided in Table 5. The anxiety subscale showed a mean score of 8.02 (SD = 5.92), half of the participants (51.6 %) experienced moderate to extreme symptoms of anxiety (see Figure 2A). The mean of the depression scale was at 8.01 (SD = 5.20), half of the participants (54.4 %) reported moderate to extreme symptoms of depression (see Figure 2B). The stress subscale had a mean score of 5 (SD = 4.81); more than two-thirds of the participants (81.8 %) reported normal to mild symptoms of stress (see Figure 2C).

Descriptive statistics of all scores from Experiment 1.

| Score | Scales | Sector | N | Mean | SD | SE | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | BFI-10 | Agreeableness | 198 | 3.25 | 1.05 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Conscientiousness | 198 | 3.33 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Extraversion | 198 | 2.67 | 1.16 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Neuroticism | 198 | 3.10 | 1.14 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Openness | 198 | 3.77 | 1.09 | 0.08 | 0.15 | ||

| COVID-19 | EPII | Infection history | 792 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Economic | 198 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.04 | ||

| Work | 693 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||

| Home life | 198 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.05 | ||

| Social activities | 198 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.07 | ||

| Emotional state | DASS21 | Anxiety | 99 | 8.02 | 5.92 | 0.60 | 1.18 |

| Depression | 99 | 8.01 | 5.20 | 0.52 | 1.04 | ||

| Stress | 99 | 4.98 | 4.81 | 0.48 | 0.96 | ||

| CFT score | 99 | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

Levels of the emotional state survey DASS21 per subscale (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress) for Experiment 1.

With regards to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than half of the questions related to social activities were answered with yes (66.2 %; see Figure 3). Roughly 10–12 % of the questions about changes in work, home life, and economics were reported as positive. Only 2.5 % of the questions related to infection history were answered with yes, indicating that most participants were not in direct contact with a COVID-19 infection.

Domains of life influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic for Experiment 1.

A.2.2 Experiment 2

Table 6 provides descriptive data for the measurements of the English study. The anxiety subscale showed a mean score of 9.10 (SD = 6.05); more than two-thirds of the participants (69 %) were classified in the moderate to extreme spectrum of anxiety (see Figure 4A). The mean of the depression scale was at 9.87 (SD = 5.75); more than half of the participants (67 %) reported severe to extreme depression symptoms (see Figure 4B). The stress subscale had a mean score of 6.12 (SD = 4.72); more than two-thirds of the participants (79.4 %) reported normal to mild symptoms of stress (see Figure 4C).

Descriptive statistics of all scores from Experiment 2.

| Score | Scales | Sector | N | Mean | SD | SE | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | BFI-10 | Agreeableness | 194 | 3.25 | 1.15 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Conscientiousness | 194 | 3.49 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Extraversion | 194 | 3.02 | 1.12 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Neuroticism | 194 | 3.25 | 1.11 | 0.08 | 0.16 | ||

| Openness | 194 | 3.57 | 1.24 | 0.09 | 0.18 | ||

| COVID-19 | EPII | Infection history | 776 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Work | 679 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||

| Economic | 194 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||

| Home life | 194 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.07 | ||

| Social activities | 194 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ||

| Emotional state | DASS21 | Anxiety | 97 | 9.10 | 6.05 | 0.61 | 1.22 |

| Depression | 97 | 9.87 | 5.75 | 0.58 | 1.16 | ||

| Stress | 97 | 6.12 | 4.72 | 0.48 | 0.95 | ||

| CFT score | 97 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

Levels of the emotional state survey DASS21 per subscale (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress) for Experiment 2.

With regards to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than three-quarters of the questions related to social activities were answered with yes (80.4 %) (see Figure 5). More than one-third of the questions in relation to changes in home life were answered with yes (34.0 %) while one-quarter of the questions in relation to changes in the work situation were answered positively (25.6 %). Roughly 6 % of the questions related to infection history were answered with yes, indicating that most participants were not in direct contact with a COVID-19 infection.

Domains of life influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic for Experiment 2.

A.3 Summary

The results were manifold. Mild to extreme anxiety levels were experienced by 51.6 % of the participants in the German and 69 % of the participants in the English dataset, mild to extreme depression symptoms by 54.4 % in the German and 67 % in the English dataset. The difference between the German and the English data might be due to the differing severeness of the COVID-19 situation. During the data collection, a new strain of the virus was identified in the UK, and scientists were discussing the possibility of it being more infectious and dangerous than the previous strain (Horby et al. 2021). Hence, the perception of threat could have differed in the two countries during data collection. This aspect is also reflected in the measures of life changes due to the pandemic. The percentage of positively answered questions for all domains was relatively higher in the dataset from the UK than in the German dataset, indicating that the regulations in the UK might have had a larger impact.

References

Allen, Mark S., Iain Greenlees & Marc V. Jones. 2014. Personality, counterfactual thinking, and negative emotional reactivity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15(2). 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.10.011.Search in Google Scholar

Allen, Mark S., Sarah J. Knipler & Amy Y. C. Chan. 2019. Happiness and counterfactual thinking at the 2016 summer Olympic Games. Journal of Sports Sciences 37(15). 1762–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1592803.Search in Google Scholar

Alzueta, Elisabet, Paul Perrin, Fiona C. Baker, Sendy Caffarra, Daniela Ramos-Usuga, Dilara Yuksel & Juan Carlos Arango-Lasprilla. 2020. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. Journal of Clinical Psychology 77(3). 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23082.Search in Google Scholar

Anderson, Alan Ross. 1951. A note on subjunctive and counterfactual conditionals. Analysis 12(2). 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/12.2.35.Search in Google Scholar

Ardakani, Zahra Pooraghaei, Saber Mehri & Mohsen Parvazi Shandi. 2015. Relationship between personality dimensions and counterfactual thinking in runners in Iran’s super league in 2013–2014. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Life Sciences 5(1). 5515–5521.Search in Google Scholar

Arregui, Ana & Maria Biezma. 2016. Discourse rationality and the counterfactuality implicature in backtracking conditionals. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 20. 91–108.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Reinhold Kliegl, Shravan Vasishth & Harald Baayen. 2018. Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1506.04967.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, Rune Haubo Bojesen Christensen, Hendik Singmann, Bin Dai, Fabian Scheipl & Gabor Grothendieck. 2020. Package “lme4”, version 1.1-34 [R package]. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/lme4.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Broomhall, Anne Gene & Wendy J. Phillips. 2018. Collective harmony as a moderator of the association between other-referent upward counterfactual thinking and depression. Cogent Psychology 7(1). 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2017.1416884.Search in Google Scholar

Broomhall, Anne Gene, Wendy J. Phillips, Donald W. Hine & Natasha M. Loi. 2017. Upward counterfactual thinking and depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 55. 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.010.Search in Google Scholar

Byrne, Ruth. 2015. Counterfactual thought. Annual Review of Psychology 67. 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033249.Search in Google Scholar

Byrne, Ruth. 2002. Mental models and counterfactual thoughts about what might have been. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6(10). 426–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01974-5.Search in Google Scholar

Callander, Gemma, Gary Brown, Philip Tata & Lesley Regan. 2007. Counterfactual thinking and psychological distress following recurrent miscarriage. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 25. 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830601117241.Search in Google Scholar

CapRadio. 2022. California coronavirus updates: US life expectancy fell by three years in 2021. Latest News, 31 August. https://www.capradio.org/articles/2022/08/31/california-coronavirus-updates-august-2022/ (accessed 31 August 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Eisma, Maarten C., Kai Epstude, Henk A. W. Schut, Margaret Stroebe, Adriana Simion & Paul A. Boelen. 2020. Upward and downward counterfactual thought after loss: A multiwave controlled longitudinal study. Behavior Therapy 52(3). 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.007.Search in Google Scholar

Epstude, Kai & Neal J. Roese. 2008. The functional theory of counterfactual thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Review 12. 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308316091.Search in Google Scholar

German Federal Government. 2020a. Maskenpflicht in ganz Deutschland. Bundesregierung, Ab dieser Woche. 29 April 2020. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/themen/coronavirus/maskenpflicht-in-deutschland-1747318 (accessed 16 December 2020).Search in Google Scholar

German Federal Government. 2020b. “We need a concerted national effort,” says Chancellor Bundesregierung, Archive. 28 October 2020. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/bund-laender-beschluss-1805366 (accessed 22 November 2020).Search in Google Scholar

German Federal Government. 2021. Pressekonferenz von Bundeskanzlerin Merkel, Bürgermeister Müller und Ministerpräsident Söder nach der Besprechung der Bundeskanzlerin mit den Regierungschefinnen und Regierungschefs der Länder Bundesregierung, Mitschrift Pressekonferenz. 5 January 2021. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/pressekonferenz-von-bundeskanzlerin-merkel-buergermeister-mueller-und-ministerpraesident-soeder-nach-der-besprechung-der-bundeskanzlerin-mit-den-regierungschefinnen-und-regierungschefs-der-laender-1834444 (accessed 23 February 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Grasso, Damion J., Margaret J. Briggs-Gowan, Julian D. Ford & Alice S. Carter. 2020. The epidemic – pandemic impacts inventory (EPII). School of Medicine, University of Connecticut. https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/toolkit_content/PDF/Grasso_EPII.pdf (accessed 23 February 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Grosz, Patrick Georg. 2012. On the grammar of optative constructions (Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamin.10.1075/la.193Search in Google Scholar

Horby, Peter, Catherine Huntley, Nick Davies, John Edmunds, Neil Ferguson, Graham Medley & Calum Semple. 2021. NERVTAG presented to sage on 21/1/21. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/602584cfe90e0705566713d2/NERVTAG_note_on_B.1.1.7_severity_for_SAGE_77__1_.pdf (accessed 6 March 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Iatridou, Sabine. 2000. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31(2). 231–270. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438900554352.Search in Google Scholar

Ippolito, Michela. 2003. Presuppositions and implicatures in counterfactuals. Natural Language Semantics 11. 145–186. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024411924818.10.1023/A:1024411924818Search in Google Scholar

Lewis, David. 1973. Causation. The Journal of Philosophy 70(7). 556–567. https://doi.org/10.2307/2025310.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Mingya (ed.). 2019. Natural language conditionals and conditional reasoning, vol. 5 3. Linguistics Vanguard. [Special issue].10.1515/lingvan-2019-0003Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Mingya (ed.). 2022. Natural language conditionals and conditional reasoning volume 2, vol. 8 4. Linguistics Vanguard. [Special issue].10.1515/lingvan-2021-0036Search in Google Scholar

Lovibond, Peter F. & Sara H. Lovibond. 1995a. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy 33(3). 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u.Search in Google Scholar

Lovibond, Sara H. & Peter F. Lovibond. 1995b. Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales, 2nd edn. Sydney: Psychology Foundation.10.1037/t01004-000Search in Google Scholar

Markman, Keith D., Gavanski Igor, Steven J. Sherman & Matthew N. McMullen. 1993. The mental simulation of better and worse possible worlds. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 29(1). 87–109. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1993.1005.Search in Google Scholar

Markowitz, David M. 2022. Psychological trauma and emotional upheaval as revealed in academic writing: The case of COVID-19. Cognition and Emotion 36(1). 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.2022602.Search in Google Scholar

McCloy, Rachel & Ruth Byrne. 2000. Counterfactual thinking about controllable events. Memory & Cognition 28(6). 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03209355.Search in Google Scholar

Medvec, Victoria Husted, Scott F. Madey & Thomas Gilovich. 1995. When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(4). 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.603.Search in Google Scholar

Nikčević, Ana V., Claudia Marino, Daniel C. Kolubinski, Dawn Leach & Marcantonio M. Spada. 2021. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders 279. 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.053.Search in Google Scholar

Pandey, Deeksha, Suvrati Bansal, Shubham Goyal, Akanksha Garg, Nikita Sethi, Dan Isaac Pothiyill, Edavana Santhosh Sreelakshmi, Mehmood Gulab Sayyad & Rishi Sethi. 2020. Psychological impact of mass quarantine on population during pandemics – the COVID-19 lock-down (COLD) study. PLoS One 15. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240501.s001.Search in Google Scholar

Psychology Foundation of Australia. 2021. Overview of the DASS and its uses. http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/dass/ (accessed 23 February 2021).Search in Google Scholar

R Development Core Team. 2020. R: A language and environment for statistical computing [computer software manual]. Available at: http://www.r-project.org/index.html.Search in Google Scholar

Racine, Nicole, Brae Anne McArthur, Jessica E. Cooke, Rachel Eirich, Jenney Zhu & Sheri Madigan. 2021. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics 175(11). 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482.Search in Google Scholar

Rammstedt, Beatrice & Oliver P. John. 2007. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality 41(1). 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

Rammstedt, Beatrice, Christoph J. Kemper, Mira Céline Klein, Constanze Beierlein & Anastassiya Kovaleva. 2012. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der fünf Dimensionen der Persönlichkeit: Big-Five-Inventory-10 (BFI-10). In GESIS (working papers 2012|23), vol. 23. Leipzig: Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. https://www.gesis.org/fileadmin/kurzskalen/working_papers/BFI10_Workingpaper.pdf (accessed 21 March 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Roese, Neal J. & Kai Epstude. 2017. The functional theory of counterfactual thinking: New evidence, new challenges, new insights. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 56. 1–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.02.001.Search in Google Scholar

Sanna, Lawrence J. 2000. Mental simulation, affect, and personality. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9(5). 168–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00086.Search in Google Scholar

Schäfer, Sarah K., M. Roxanne Sopp, Christian G. Schanz, Marlene Staginnus, Anja S. Göritz & Tanja Michael. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on public mental health and the buffering effect of a sense of coherence. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 89(6). 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510752.Search in Google Scholar

Starr, William B. 2022. Counterfactuals. In Edward, N. & Uri Nodelman (eds.), The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, Winter 2022 edn. Standford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/counterfactuals/ (accessed 5 January 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Stewart, Heather and Ian Sample. 2020. Coronavirus: Enforcing UK lockdown one week earlier “could have saved 20,000 lives”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/10/uk-coronavirus-lockdown-20000-lives-boris-johnson-neil-ferguson, (accessed 2 March 2 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Summerville, Amy & Neal J. Roese. 2008. Dare to compare: Fact-based versus simulation-based comparison in daily life. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44(3). 664–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

UK Government. 2020. New national restrictions from 5 November. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/new-national-restrictions-from-5-november (access date 22 November 2020).Search in Google Scholar

UK Government. 2021. Prime minister’s address to the nation: 4 January 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-ministers-address-to-the-nation-4-january-2021 (access date 23 February 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Van Hoeck, Nicole, Patrick D. Watson & Aron K. Barbey. 2015. Cognitive neuroscience of human counterfactual reasoning. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00420.Search in Google Scholar

Vanaken, Lauranne, Patricia Bijttebier, Robyn Fivush & Dirk Hermans. 2022. Narrative coherence predicts emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A two-year longitudinal study. Cognition and Emotion 36(1). 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1902283.Search in Google Scholar

von Fintel, Kai. 2012. Conditionals. In Klaus von Heusinger, Paul Portner & Claudia Maienborn (eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of meaning, 2nd edn., 1515–1538. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.Search in Google Scholar

von Fintel, Kai & Sabine Iatridou. 2023. Prolegomena to a theory of X-marking. Linguistics and Philosophy 46(6). 1467–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-023-09390-5.Search in Google Scholar

Whiston, Aoife, Eric R. Igou & Dónal G. Fortune. 2022. Emotion networks across self-reported depression levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cognition and Emotion 36(1). 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.1993147.Search in Google Scholar

White, Katherine & Darrin Lehman. 2005. Looking on the bright side: Downward counterfactual thinking in response to negative life events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31. 1413–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205276064.Search in Google Scholar

Widiger, Thomas A. & Joshua R. Oltmanns. 2017. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry 16(2). 144–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20411.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Shizhen, Keshun Zhang, Elizabeth J. Parks-Stamm, Zhonghui Hu, Yaqi Ji & Xinxin Cui. 2021. Increases in anxiety and depression during COVID-19: A large longitudinal study from China. Frontiers in Psychology 12. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.706601.Search in Google Scholar

Zakkou, Julia. 2019. Presupposing counterfactuality. Semantics and Pragmatics 12(21). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.21.Search in Google Scholar

Zehr, Jeremy and Florian Schwarz. 2018. PennController for Internet Based Experiments (IBEX). https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MD832.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings