Abstract

The aim of this study is to examine the effects of translating literary metaphors from Serbian to English on metaphor quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity. The research involved 55 Serbian metaphors translated into English using the A is B form, which were then evaluated by 252 participants in two separate studies. Study 1 served as an extension of a previous norming study. In it, a group of participants assessed 55 translated literary metaphorical expressions, and their evaluations were compared to those of the original Serbian versions. In Study 2, a group of participants, divided into two subgroups, rated a collection of both the original metaphorical expressions and their translated counterparts. The results indicate that the translated metaphors generally scored higher in terms of aptness, familiarity, quality, and partially in metaphoricity. These findings suggest that translating the metaphors into English had a positive impact on their perceived effectiveness and familiarity. Several factors are considered to explain these outcomes, including the nature of the English language itself, the participants’ exposure to English, and the translation process. Overall, this study highlights the influence of translation on the perception of literary metaphors and provides insights into metaphor interpretation.

Abstract in Serbian

Ово истраживање је имало за циљ да испита утицај превођења књижевних метафора са српског на енглески језик на оцењивање квалитета метафоре, способности извора да опише циљ, метафоричности и степена познатости. Истраживање је обухватило 55 метафора у облику А је Б, уз оцене укупно 252 испитаника у два одвојена задатка. Први задатак је представљао продужетак претходног истраживања нормирања. У њему су испитаници оцењивали 55 преведених књижевних метафоричних израза, а њихове оцене упоређене су са оценама оригиналних метафора на српском. У другом задатку су две подгрупе испитаника оцењивале сужени избор оригиналних метафоричних израза и њихових превода. Резултати показују да су преведене метафоре добиле више оцене за прилагодљивост, познатост, квалитет и делимично за метафоричност. Ово указује на то да је превођење метафора на енглески имало позитиван утицај на њихову перципирану ефективност и познатост. Постоји неколико фактора који могу да расветле овакве резултате, попут природе енглеског језика, изложености учесника енглеском и самог процеса превођења.

1 Introductory remarks

The study of metaphor and its comprehension has been ongoing for years, highlighting the importance of continued research in this area. To avoid problems such as limited sources, random pairing of source and target, or inconsistent data, it is important to use a controlled and diverse corpus. When using different sources, selecting the right variables can be challenging, which may affect the resulting theoretical claims. Focusing on literary metaphorical expressions in Serbian (extending Stamenković et al. 2019a) and their translations into English, this study aims to collect metaphor norming data across multiple dimensions and to evaluate the influence of translation on metaphor features. The studies of metaphor translation have rarely involved participants, and this is, to our knowledge, the first study to involve evaluating metaphor features before and after the process of translation.

1.1 Metaphor features

Researchers have identified various features of metaphors, with aptness and conventionality often highlighted as key. Aptness occurs when the source domain uniquely and accurately represents the target domain, attributing the source’s prominent properties to the target’s appropriate properties. This depends largely on how well the statement captures the target’s crucial characteristic, influenced by the interaction between source and target. Conventionality, another significant feature, refers to the frequency of encountering a metaphor. Initially perceived as novel, repeated exposure renders a metaphor familiar, sometimes giving it a new literal interpretation (Kittay 1987; Utsumi 2007). Thibodeau et al. (2017) emphasize metaphor features including surprisingness, comprehensibility, familiarity, metaphoricity, and aptness – each contributing differently to our understanding of metaphors. Other researchers like Chiappe et al. (2003) and Gernsbacher et al. (2001) focus on meaningfulness, truthfulness, and the potential for inverting the source and target domains, or the unidirectionality in most everyday metaphors (Kövecses 2010). Additionally, mental images (Gibbs and O’Brien 1990; Gibbs et al. 2006), conventionality, and asymmetry (Saeed 2009) are also discussed. These features, though sometimes overlapping, are distinctly named across various studies (Holyoak and Stamenković 2018; Roncero and de Almeida 2015; Stamenković et al. 2019a). Gagné (2002) showed that metaphor comprehension is influenced by aptness, expectedness, and prominence.

Aptness is the degree to which the source domain’s figurative meaning expresses the target domain’s crucial feature (Blasko and Connine 1993; Chiappe and Kennedy 1999; Chiappe et al. 2003; Gerrig and Healy 1983; Glucksberg and McGlone 1999). For a metaphor to be highly apt, two conditions must be met: (i) the source domain must have the prominent feature being attributed, and (ii) the prominent feature of the source domain must be relevant to the target domain. Even if there is a weak connection between the concept and its distinctiveness, new source concepts can still create highly apt metaphors (Camac and Glucksberg 1984). Aptness describes the relative position of the source and target within their respective domains (Tourangeau and Sternberg 1981, 1982). This feature represents the strength of the connection between the source domain and its figurative meaning (Bowdle and Gentner 2005; Gentner and Wolff 1997; Wolff and Gentner 2000; see also Giora 1997). Conventionality can describe how often a source domain expresses a specific figurative meaning and how quickly it conveys that meaning (Bowdle and Gentner 2005). Another usage of conventionality relates to the familiarity of the source-target pair (e.g., love is a journey; Gibbs 1992; Lakoff and Johnson 1980). Familiarity is a metaphor dimension mostly describing the frequency of a metaphorical expression in a language. Within the present approach we are going to examine this feature as familiarity (therefore we avoid doubling it, and do not use conventionality).

Subjective ratings are a common method for assessing metaphor features or dimensions (Cardillo et al. 2010; Cardillo et al. 2017; Katz et al. 1988; Roncero and de Almeida 2015; Stamenković et al. 2019a). Although reliable, the validity of these ratings is unclear due to potential confusion between processing fluency and the dimension being rated (Alter and Oppenheimer 2009; Jacoby et al. 1988; Jacoby and Whitehouse 1989; Kahneman 2011; Thibodeau and Durgin 2011). This confusion might result in high correlations between distinct dimensions like aptness and familiarity (Jones and Estes 2006; Thibodeau and Durgin 2011) and question the findings of studies based on subjective ratings (Thibodeau et al. 2017). Although subjective ratings can be useful, they should be treated cautiously. Thibodeau et al. (2017) suggest using corpus analysis and latent semantic analysis (LSA; Landauer and Dumais 1997) for objective measurements of familiarity and aptness. Corpus analysis determines metaphor frequency in public discourse (Steen et al. 2010), while LSA uses multidimensional space to measure metaphor quality based on previous studies on aptness (Kintsch 2000; Kintsch and Bowles 2002; Tourangeau and Sternberg 1981).

1.2 Translating metaphors

Translating metaphors can be a complex task, as they often involve figurative expressions that convey meaning beyond literal words. When working with metaphors in translation, it is crucial to consider the cultural, historical, cognitive, and linguistic context of both the source and target languages to ensure that the translation effectively captures the intended meaning. This may involve substituting the original metaphor with one that is culturally appropriate, employing a simile or other figures of speech in the target language, or providing an annotation or explanation in the target text (van den Broeck 1981).

Several studies have addressed the challenges of metaphor translation, leading to the development of different approaches. Newmark (1980, 1988 viewed metaphors as stylistic devices, and this perspective has been applied to translations between English and Ukrainian (Oliynyk 2014), as well as in studies of translation issues involving metaphors categorized by Newmark (Dickins 2005). The translatability of metaphorical expressions is related to the level of conceptual systems in the source and target cultures (Schäffner 2004). The cognitive approach allows for more interlingual and intercultural variation in metaphorical language translation, as it utilizes concepts from metaphor theory to help reflect on translation procedures (Shuttleworth 2017).

Steen (2014) suggests that the widespread presence of metaphors across languages is due to the universal need for metaphors in thought, resulting in prior parallelism of metaphorical vocabulary between source and target languages. However, Kövecses (2014) argues that, although universal embodiment may produce similar metaphors, they differ across languages and cultures due to the complexity of human cognition. Therefore, translators should consider contextual factors and choose the most adequate translation option, as metaphor translation can be important for understanding cultures and values (see Arduini 2014). Numerous studies have explored culture-specific differences in metaphorical expressions and their translation. Schäffner (2014) examines financial crisis metaphors in English and German, while other research includes metaphor translation in popular science magazines (Manfredi 2014) and cookery books (Lindqvist 2014), as well as the role of metaphors in establishing thematic, interpersonal, and textual links within and across texts (Swain 2014). Studies have also explored the translation of figurative language in poetry (e.g., Béghain 2014; van der Heide 2014). Metaphor translation studies have gradually become more descriptive, focusing on understanding the relationship between source and target items (Samaniego Fernández et al. 2005).

When it comes to metaphors in Serbian (in the focus of our approach), although we find an extended line of metaphor research (e.g., Antović 2009; Đurović and Silaški 2010a; Figar 2014; Klikovac 2004; Petrović 1967; Tasić and Stamenković 2012; Vidanović 1995), as well as studies comparing and contrasting metaphorical expressions in English and Serbian (e.g., Đurović and Silaški 2010b; Rasulić 2004; Vlajković and Stamenković 2013), no studies have evaluated the impact of translation on metaphor understanding.

1.3 Norming studies

Taking everything into account, it can be said that research methods for studying metaphors exhibit some unevenness, as they involve various techniques, tasks, instruments, and stimuli. This creates a need for norming studies that would lead to more consistent and controlled research. One of the largest norming studies was conducted by Katz et al. (1988), and featured both literary and non-literary metaphors. The scales in this study were reliable, and the chosen dimensions included comprehensibility, ease of interpretation, degree of metaphoricity, metaphor goodness, metaphor imagery, subject imagery, predicate imagery, felt familiarity, semantic relatedness, and the number of alternative interpretations. The researchers concluded that individual differences were apparent between participants, and there was a significant correlation among the 10 dimensions. Other large-scale norming studies important to mention here are those conducted by Cardillo et al. (2010, 2017. Their goal was to generate sufficient material for investigating metaphors in neuroscience by norming pairs of metaphorical and literal sentences. The elements scored spanned from word to comprehension levels, and the parameters included familiarity, naturalness, imageability, figurativeness, and comprehensibility. In another metaphor norming study, Roncero and de Almeida (2015) examined frequency, saliency, and connotativeness scores for the properties and whether expression type (metaphor vs. simile) affected interpretations. Their results indicate that metaphors activate more salient properties than similes, but connotativeness levels for metaphors are similar to salient properties for similes. The authors concluded that the two expression types did not differ across measures such as aptness, conventionality, familiarity, and interpretive diversity.

2 Background

Aiming to provide pre-tested materials for future psycholinguistic research, Stamenković et al. (2019a) developed a normed metaphor corpus in the Serbian language, examining various features. The study normed 55 non-literary and 55 literary metaphors from seven questionnaires along seven dimensions: metaphoricity, quality/goodness, aptness, familiarity, comprehensibility, source-target similarity, and number of interpretations. Literary metaphors were sourced from renowned Serbian poets known for their rich metaphorical work, including Branko Radičević, Laza Kostić, Vojislav Ilić, Đura Jakšić, Desanka Maksimović, and Branko Miljković, while non-literary metaphors were drawn from different non-literary sources, including previous studies. When it comes to the literary metaphors, the poems used to select the items for the norming study aimed to represent a wide range of poetic movements and styles. The expert, a literary scholar with a linguistic background who was a native speaker of Serbian, had the task of extracting all metaphorical expressions from these poems. These were then grouped, with all similar/duplicate metaphors counted as one. Subsequently, all metaphors were transformed into the A is B form (with both elements being nominals), resulting in the finalized list of 55 items. Participants rated the metaphors on a seven-point Likert scale for the first six dimensions, while the seventh dimension, the number of interpretations, required listing the interpretations. The analysis involved rating metaphors, comparing literary to non-literary metaphors, and examining the relationships between dimensions. The study produced a normed corpus, reliable scales for each dimension (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.91 and 0.99), and significant correlations among dimensions. Literary metaphors had higher metaphoricity but were rated as less apt, familiar, and comprehensible, and with less apparent source-target similarity. While the results for literary metaphors were unsurprising due to their poetic origins, some participants rated non-literary metaphors as having higher quality, likely influenced by their perception of aptness. As with Katz et al. (1988), the study found reliable ratings for each dimension and significant interrelations among many dimensions. The items from this norming study have been used in several empirical procedures (e.g., Milenković 2021; Stamenković et al. 2023; Ichien et al. 2024a; Ichien et al. 2024b).

3 The present approach and its aims

In this study, our aim was to investigate the potential impact of translating literary metaphors from Stamenković et al. (2019a) on four key aspects: metaphor quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity. These features were chosen based on the metaphor feature list explained in the theoretical part (see Section 1), as well as on assessing the relevance of different features used in previous similar research (Cardillo et al. 2010, 2017; Katz et al. 1988; Roncero and de Almeida 2015). Given the length of the collection procedures, we opted for a smaller number of features as compared to Stamenković et al. (2019a). Although we were aware that isolated nominal metaphors are not as common as one might think (for evidence, see Deignan et al. 2013; Steen 2014), we still followed the pattern to make the study comparable to the previous norming studies. We decided to focus on literary metaphors as they proved to be more needed in the realm of metaphor studies (see Jacobs and Kinder 2018; Stamenković et al. 2019b; Stamenković et al. 2020, 2023) precisely because contemporary studies have predominantly focused on “common”, “everyday” metaphors, very frequently generated by scholars rather than poets. To accomplish this, we conducted two separate empirical procedures, both of which involved participant evaluations using the same rating scale as in Stamenković et al. (2019a). The first study served as a direct extension of the Stamenković et al. (2019a) norming article, where a group of participants assessed 55 translated literary metaphorical expressions, and their evaluations were compared to those of the original Serbian versions. In the second study, two groups of participants rated a collection of both the original metaphorical expressions and their translated counterparts.

3.1 Study 1

3.1.1 Participants

A total of 186 participants took part in this study, which included 139 females, 46 males, and one undeclared. The average age of the participants was 21.7 years. All participants were Serbian English language students at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš, represented various levels of study, and participated for course credit. Therefore, they were selected from a pool similar to the one employed in the previous study, but at a different time (and thus encompassed different students), which makes the two groups comparable. In this study we explicitly controlled for knowledge of English. The study focused on a single department to ensure participants were fluent in English. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš. Their outcomes were compared to those of the participants from Stamenković et al. (2019a), who were involved in rating literary metaphors based on quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity. This comparison group selected from the previous study consisted of 133 participants, with 99 females, 33 males, and one undeclared, and had a mean age of 21.6 years.

3.1.2 Instrument and procedure

The study utilized all 55 literary metaphorical expressions from Stamenković et al. (2019a). These metaphors were translated into English by two translators (KM and DS), with a third translator (MT) verifying the translations. Participants evaluated the metaphors on a seven-point Likert scale for quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity. A comprehensive list of both the original and translated items can be found in the appendix.[1] The study consisted of four questionnaires, each designed to gather data on one of the four dimensions measured for the 55 metaphors. The metaphors were presented in a random order within the questionnaires. Participants first provided basic personal information, and then followed the instructions for completing the tasks. Completing the questionnaires took up to 30 min, depending on the task difficulty, with 42–50 participants per questionnaire. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the questionnaires, which considerably reduced the completion time (55 rather than 220 sentences to assess) and resembled the procedure from the original study. The questionnaires were created using Google Forms and were completed online. The questions within each questionnaire were tailored to address the specific dimension being assessed and to be as friendly as possible to all participants (of course, different participants could still have a slightly different understanding of the dimensions):

Metaphoricity: How metaphorical are the statements in the following list? (For each metaphor, seven possible answers were given ranging from 1 – “not metaphorical” to 7 – “very metaphorical”.)

Quality: How would you rate the quality of the metaphorical expressions in the following list? (For each metaphor, seven possible answers were given ranging from 1 – “of poor quality” to 7 – “of extraordinary quality”.)

Aptness – for each source-target pair there was a question, for example: In the sentence A woman is a flower, how apt is the concept B to describe the concept A? (For each metaphor, seven possible answers were given ranging from 1 – “not apt” to 7 – “very apt”.)

Familiarity: How familiar are the metaphors in the following list? (For each metaphor, seven possible answers were given ranging from 1 – “not familiar” to 7 – “very familiar”.)

3.1.3 Results

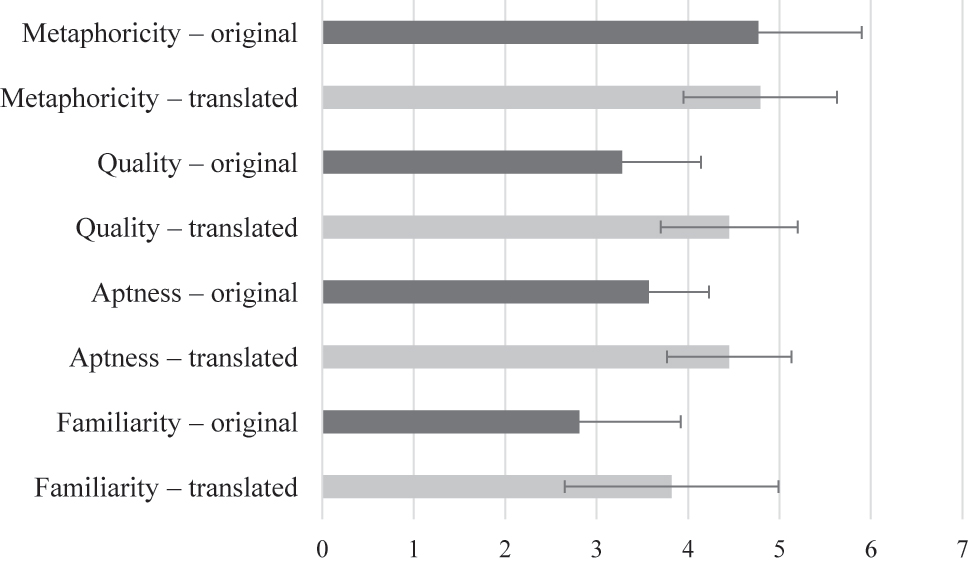

The results of Study 1 are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1 – the original metaphor scores come from Stamenković et al. (2019a), while the translation scores were obtained from the present study.

Mean scores per feature in Study 1.

| Property | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metaphoricity – original | 4.77 | 1.13 | 36 |

| Metaphoricity – translated | 4.79 | 0.84 | 50 |

| Quality – original | 3.28 | 0.86 | 32 |

| Quality – translated | 4.45 | 0.75 | 45 |

| Aptness – original | 3.57 | 0.66 | 31 |

| Aptness – translated | 4.45 | 0.68 | 49 |

| Familiarity – original | 2.81 | 1.11 | 34 |

| Familiarity – translated | 3.82 | 1.17 | 42 |

Mean scores per feature in Study 1.

Table 1 presents a comparison of the original and the translated metaphors across four properties: metaphoricity, quality, aptness, and familiarity. Independent samples t tests confirmed that the differences were significant in three out of four cases, at the level of p < 0.001. Only in the case of metaphoricity was the difference insignificant – the original metaphors (M = 4.77, SD = 1.13) and their translations (M = 4.79, SD = 0.84) did not differ significantly when it came to the perceived metaphoricity, t(84) = 0.75, p = 0.94. Translated metaphors consistently exhibited higher mean scores than their original counterparts in all aspects. Notably, translated metaphors demonstrated a considerable increase quality: the translated metaphors (M = 4.45, SD = 0.75) were judged as having a substantially higher quality than the original ones (M = 3.28, SD = 0.85), t(75) = 6.36, p < 0.001. A similar pattern was found in the judged metaphor aptness – the translated metaphors (M = 4.45, SD = 0.68) were judged as being more apt than the original ones (M = 3.57, SD = 0.66), t(78) = 5.71, p < 0.001. Finally, familiarity also showed a marked improvement in the translated versions (M = 3.82, SD = 1.17) as compared to the original metaphorical expressions (M = 2.81, SD = 1.11), t(74) = 3.81, p < 0.001. The results suggest that translation from Serbian into English may have enhanced certain aspects of metaphors, particularly aptness and quality, while maintaining similar levels of metaphoricity. Furthermore, it is possible that these findings stem from the participants’ preference for reading in English. The results for each item are given in the appendix. It is worth noting that in the original study all four features were positively and significantly correlated with each other, while in the translation-based study, metaphoricity was not correlated with the remaining features.

The results in this section are derived from the responses provided by different groups of students (i.e., Study 1 involved students of English, but the comparison group from the previous study involved psychology students alongside students of English) tested on two separate occasions and containing an unequal number of participants. To determine whether the same pattern would emerge, we conducted a similar procedure involving both the original and translated metaphors with a new, homogenous group of participants tested concurrently and divided into two equal subgroups. We also decided to focus on those expressions which exhibited the biggest discrepancies between originals and translations in Study 1.

3.2 Study 2

3.2.1 Participants

In Study 2, a total of 66 participants were involved, including 43 females and 23 males, with an average age of 22.4 years. These participants were once again English language students from various levels of study at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš. All participants were native speakers of Serbian and fluent in English. They participated for course credit. The participants were divided into two subgroups, and the metaphors were allocated and counterbalanced between the groups in regard to the language and features, as described in the following subsection. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Niš.

3.2.2 Instrument and procedure

To have two groups of students rate metaphorical expressions on two dimensions each, we chose to examine a subset of the metaphors assessed in Study 1. Specifically, we calculated the mean differences between the originals and translations across all four dimensions and selected the 20 of the 55 items where the differences were most significant. Original metaphorical expressions with odd positions in the difference ranking and translations with even positions (a total of 20 items, 10 in each language) were assigned to one group of 33 students, while the remaining 20 items were assigned to the other 33 students. This ensured that no group rated both the original and the translation of the same metaphorical expression (no one could see one metaphor in both languages). Both groups provided ratings for two different metaphor features (each participant encountered the 20 items twice). All other aspects of this study were the same as those in Study 1, so the descriptions will not be repeated here. All items can be found in the appendix.

3.2.3 Results

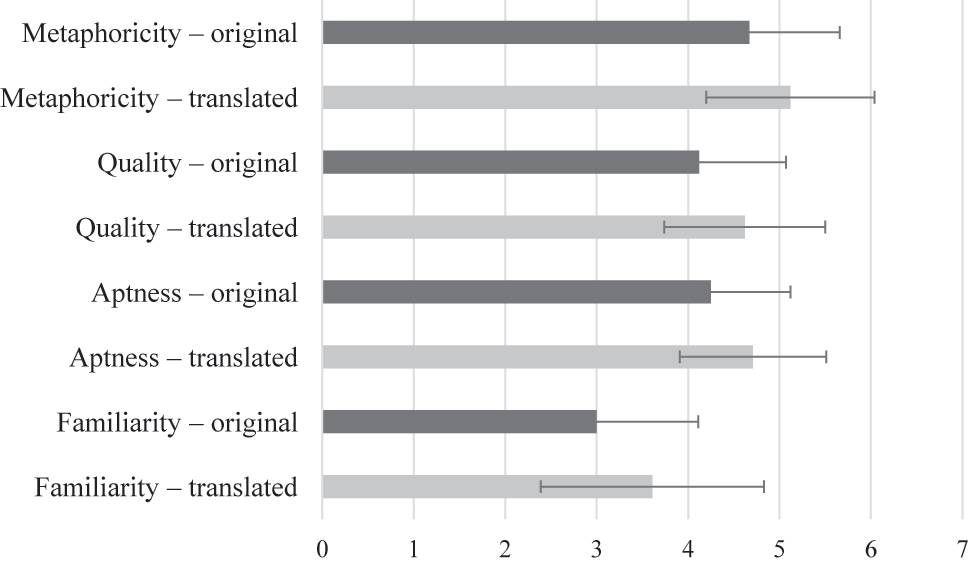

The results of Study 2 are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Mean scores per feature in Study 2.

| Property | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metaphoricity – original | 4.67 | 0.99 | 33 |

| Metaphoricity – translated | 5.12 | 0.92 | 33 |

| Quality – original | 4.12 | 0.95 | 33 |

| Quality – translated | 4.62 | 0.88 | 33 |

| Aptness – original | 4.25 | 0.87 | 33 |

| Aptness – translated | 4.71 | 0.80 | 33 |

| Familiarity – original | 3.00 | 1.11 | 33 |

| Familiarity – translated | 3.61 | 1.22 | 33 |

Mean scores per feature in Study 2.

Paired-sample t tests confirmed that the differences were significant in all four cases, at the level of p < 0.001. Like in Study 1, in Table 2 and Figure 2 we can see a comparative analysis of original and translated metaphors, focusing on four properties: metaphoricity, quality, aptness, and familiarity. Translated metaphors consistently exhibit higher mean scores than the original metaphors across all four categories. The most significant improvement is observed in familiarity, with translated metaphors (M = 3.61, SD = 1.22) rated as more familiar than the original ones (M = 3.00, SD = 1.11), t(65) = 6.11, p < 0.001. Additionally, there was a noticeable increase in aptness, where again the translated metaphors (M = 4.71, SD = 0.80) were seen as more apt than the originals (M = 4.25, SD = 0.87), t(65) = 5.32, p < 0.001. Similarly, the translated versions (M = 4.62, SD = 0.88) were rated as having a higher quality than the original expressions (M = 4.12, SD = 0.95), t(65) = 6.13, p < 0.001. Finally, in the second study we also found a pattern that was missing from the first one – namely, the translated set of metaphors (M = 5.12, SD = 0.92) was also rated as being more metaphorical than the original set (M = 4.67, SD = 0.99), t(65) = 6.65, p < 0.001.

The data once again suggests that when translated into English, Serbian poetic metaphors become rated higher on the tested dimensions. The results for each item are again given in the appendix. When it comes to correlations, in both the Serbian and English versions of metaphors, all four features were positively and significantly correlated with each other. Comparing the results from Study 1 and Study 2, we can observe some notable similarities in the properties of original and translated metaphors. In both studies, translated metaphors exhibit higher mean aptness scores compared to the original versions. A similar trend is seen in the familiarity and quality categories, with translated metaphors consistently outperforming the original metaphors. The most significant change in Study 1 is found in quality, while in Study 2, the greatest change is observed in familiarity. Metaphoricity scores reveal an increase in both studies for translated metaphors. Overall, these findings suggest that, in Serbian students of English, translation from Serbian into English may enhance certain aspects of metaphors, such as aptness, familiarity, and quality, while also leading to a moderate increase in metaphoricity.

4 Discussion

It is evident that translating the metaphors in these studies from Serbian to English plays a significant role in increasing the perceived aptness, familiarity, and quality of metaphors. However, the reasons behind this phenomenon remain unclear. Comparing the results of Serbian and English metaphors in this study to the results of literary and non-literary metaphors in a previous study reveals a similarity. Translating the metaphors into English seems to have led respondents to perceive them as less poetic but more apt and familiar, while maintaining the same level of metaphoricity as in the previous study. This observation suggests that respondents find English metaphors closer to their everyday speech, and feel more comfortable around English in general, as previous research has shown that literary metaphors sound less familiar and comprehensible than non-literary ones. Viewing the findings from this perspective justifies the increase in aptness and familiarity and helps make sense of the higher perceived quality when considered in relation to aptness perception. The persistence in metaphoricity levels in the first study may indicate that the chosen metaphors indeed have a strong rhetorical effect, and therefore, need to be interpreted as truly figurative, regardless of the language in which they appear.

Moreover, the participants in this study were English language students who had extensive exposure to English through their curriculum and direct instruction on various aspects of the English language, literature, and culture. Consequently, it could be expected that they would perceive metaphors translated into English as more apt and familiar. In addition, it is possible that the respondents perceive translated literary metaphors as such because a substantial number of their courses are literary, revolving around analyses of poetry abundant in metaphors, that is, their mind is, in a way, “trained” to recognize metaphors in English with ease and understand them accordingly. Their continuous and effective exposure to English and its linguistic patterns likely influenced their perception of metaphor translations, making them appear more apt and familiar than the original Serbian metaphors. In other words, their higher proficiency in English may have facilitated their evaluation of metaphors translated into English due to their ongoing contact with the language. Since the translation process employed in this study was as literal as possible, it was perhaps the case that the higher level of conventionality and familiarity possessed by the participants when it came to the everyday use of their native Serbian language led to a lower level of familiarity with Serbian metaphors. What this means is that these metaphors might have sounded stranger to the students’ ears compared to their English counterparts, as they did not naturally expect such source-target pairs in everyday speech in Serbian. However, they might have accepted these combinations more easily in English, where the level of expectedness was lower. Consequently, a wider range of such combinations would sound more familiar to them, even if they had not encountered those specific examples before.

Finally, Study 2 revealed a more significant increase in metaphoricity. It is important to note that this increase is approximately at the same level as the increases observed in other categories. However, it should not be equated with metaphoricity in the first study in terms of the extent of the increase. One possible explanation is that metaphoricity rose alongside other categories since students were exposed to both Serbian and English metaphors in this study. When directly comparing the two, the students tended to rate the metaphoricity of English examples higher, as was the case with other examined properties. The results for this property show that the metaphoricity of “Serbian” metaphors is much closer to the value from the 2019 study than the metaphoricity of “English” metaphors is to the value from Study 1. This indicates that students felt the need to differentiate more between the two types of metaphors, with metaphoricity showing the highest increase in score compared to Study 1. The reasons for this differentiation can also be attributed to the factors discussed earlier.

5 Conclusions

In conclusion, this contribution serves two important purposes. First, it provides access to standardized lists of literary metaphors in Serbian along with their translation into English, and so facilitates the initial phase of future research by offering a useful resource. Second, the findings shed light on certain aspects of metaphor access procedures, particularly participants’ understanding of the qualities they assessed. The analyses showed that the scores for each of the dimensions were reliable, as evidenced by the quality of the scales, and the correlation of most of the variables (that is, the dimensions) was significant; indeed, in the original study and Study 2, all four features were positively and significantly correlated with each other, and the only exception was with metaphoricity in one part of Study 1. The correlations of the dimensions, among other things, imply that in the respondents’ answers, the assessment of metaphor quality could be significantly more related to aptness and to the degree of familiarity than to the assessment of metaphoricity. The analyses also revealed that translation from Serbian to English can enhance various aspects of metaphors, including aptness, familiarity, quality, and even metaphoricity to some extent, which is something that could be considered by professional translators and translator trainers dealing with translation from Serbian into English. With these 55 metaphors evaluated across four dimensions and translated into English, we believe they offer sufficient diversity and suitability for further research. Moreover, we anticipate that they will prove useful to future researchers in the expanding field of metaphor studies, as well as in metaphor translation studies. It is important to acknowledge that the participants’ background, specifically when considering non-native English speakers, as well as potentially different understanding of the tested features, may lead to different results (as suggested by Study 1). Nevertheless, we consider the lists that are provided in the appendix to this paper as a significant first step towards establishing the groundwork for broader empirical investigations into metaphor translation research. It is worth noting that including a group of native English speakers as an additional norming group would have been beneficial, and we intend to address this by testing native speakers’ comprehension of these metaphors in future studies. Finally, the standardized lists of Serbian metaphors translated into English offer a valuable resource for future research. We hope that our findings will pave the way for more comprehensive investigations in the field of metaphor research and contribute to the development of metaphor translation studies.

Funding source: Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant No. 7715934, Structuring Concept Generation

Funding source: Ministarstvo Prosvete, Nauke i Tehnološkog Razvoja

Award Identifier / Grant number: 451-03-65/2024-03 (applies to Miloš Tasić)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Keith J. Holyoak and Nicholas Ichien for their comments on the early design of the studies. Open access publication was made possible with support from Södertörn University, Stockholm.

-

Competing interests: The authors confirm that they have no conflict of interests to declare regarding the content presented in this manuscript.

-

Research funding: Miloš Tasić was supported by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, Grant no. 7715934, “Structuring Concept Generation with the Help of Metaphor, Analogy and Schematicity – SCHEMAS”, as well as by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, Contract no. 451-03-65/2024-03.

-

Data availability: The data used in this study are publicly available and can be accessed through Mendeley Data, at https://doi.org/10.17632/rnfk7xpwbg.1.

References

Alter, Adam L. & Daniel M. Oppenheimer. 2009. Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review 13(3). 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309341564.Search in Google Scholar

Antović, Mihailo. 2009. Lingvistika, muzikalnost, kognicija [Linguistics, musicality, cognition]. Niš: Niški kulturni centar.Search in Google Scholar

Arduini, Stefano. 2014. Metaphor, translation, cognition. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 41–53. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Béghain, Véronique. 2014. “Only a finger-thought away”: Translating figurative language in Troupe’s and Daa’ood’s poetry. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 299–313. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Blasko, Dawn G. & Cynthia M. Connine. 1993. Effects of familiarity and aptness on metaphor processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 19(2). 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.2.295.Search in Google Scholar

Bowdle, Brian & Dedre Gentner. 2005. The career of metaphor. Psychological Review 112(1). 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.193.Search in Google Scholar

Broeck, Raymond van den. 1981. The limits of translatability exemplified by metaphor translation. Poetics Today 2(4). 73–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772487.Search in Google Scholar

Camac, Mary K. & Sam Glucksberg. 1984. Metaphors do not use associations between concepts, they are used to create them. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 13(6). 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01068178.Search in Google Scholar

Cardillo, Eileen R., Christine Watson & Anjan Chatterjee. 2017. Stimulus needs are a moving target: 240 additional matched literal and metaphorical sentences for testing neural hypotheses about metaphor. Behavior Research Methods 49. 471–483. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0717-1.Search in Google Scholar

Cardillo, Eileen R., Gwenda L. Schmidt, Alexander Kranjec & Anjan Chatterjee. 2010. Stimulus design is an obstacle course: 560 matched literal and metaphorical sentences for testing neural hypotheses about metaphor. Behavior Research Methods 42. 651–664. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.42.3.651.Search in Google Scholar

Chiappe, Dan L. & John M. Kennedy. 1999. Aptness predicts preference for metaphors or similes, as well as recall bias. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 6. 668–676. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03212977.Search in Google Scholar

Chiappe, Dan L., John. M. Kennedy & Tim Smykowski. 2003. Reversibility, aptness, and the conventionality of metaphors and similes. Metaphor and Symbol 18(2). 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms1802_2.Search in Google Scholar

Deignan, Alice, Jeannette Littlemore & Elena Semino. 2013. Figurative language, genre and register. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dickins, James. 2005. Two models for metaphor translation. Target 17. 227–273. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.17.2.03dic.Search in Google Scholar

Đurović, Tatjana & Nadežda Silaški. 2010a. Metaphors we vote by: The case of “marriage” in contemporary Serbian political discourse. Journal of Language & Politics 9(2). 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.9.2.04dur.Search in Google Scholar

Đurović, Tatjana & Nadežda Silaški. 2010b. The conceptualisation of the global financial crisis via the economy is a person metaphor: A contrastive study of English and Serbian. Facta Universitatis, Series: Linguistics and Literature 8(2). 129–139.Search in Google Scholar

Figar, Vladimir. 2014. Emotional appeal of conceptual metaphors of conflict in the political discourse of daily newspapers. Facta Universitatis, Series: Linguistics and Literature 12(1). 43–61.Search in Google Scholar

Gagné, Christina L. 2002. Metaphoric interpretations of comparison-based combinations. Metaphor and Symbol 17(3). 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327868MS1703_1.Search in Google Scholar

Gentner, Dedre & Phillip Wolff. 1997. Alignment in the processing of metaphor. Journal of Memory and Language 37(3). 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.1997.2527.Search in Google Scholar

Gernsbacher, Morton Ann, Boaz Keysar, Rachel R. W. Robertson & Necia K. Werner. 2001. The role of suppression and enhancement in understanding metaphors. Journal of Memory and Language 45(3). 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmla.2000.2782.Search in Google Scholar

Gerrig, Richard J. & Alice F. Healy. 1983. Dual processes in metaphor understanding: Comprehension and appreciation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 9(4). 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.9.4.667.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W.Jr. 1992. Categorization and metaphor understanding. Psychological Review 99(3). 572–577. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.572.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W.Jr. & Jennifer E. O’Brien. 1990. Idioms and mental imagery: The metaphorical motivation for idiomatic meaning. Cognition 36(1). 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(90)90053-M.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Raymond W.Jr., Jessica J. Gould & Michael Andric. 2006. Imagining metaphorical actions: Embodied simulations make the impossible plausible. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 25(3). 221–238. https://doi.org/10.2190/97MK-44MV-1UUF-T5CR.Search in Google Scholar

Giora, Rachel. 1997. Understanding figurative and literal language: The graded salience hypothesis. Cognitive Linguistics 8(3). 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1997.8.3.183.Search in Google Scholar

Glucksberg, Sam & Matthew S. McGlone. 1999. When love is not a journey: What metaphors mean. Journal of Pragmatics 31(12). 1541–1558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00003-X.Search in Google Scholar

Heide, Herman van der. 2014. “The eye’s kiss”: Contextualising Cees Nooteboom’s Bashō. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 325–335. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Holyoak, Keith J. & Dušan Stamenković. 2018. Metaphor comprehension: A critical review of theories and evidence. Psychological Bulletin 144(6). 641–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000145.Search in Google Scholar

Ichien, Nick, Dušan Stamenković & Keith J. Holyoak. 2024a. Large language model displays emergent ability to interpret novel literary metaphors. arXiv:2308.01497. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2308.01497.Search in Google Scholar

Ichien, Nick, Dušan Stamenković, Mary Whatley, Alan Castel & Keith J. Holyoak. 2024b. Advancing with age: Older adults excel in comprehension of novel metaphors. Psychology and Aging. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000836.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, Arthur M. & Annette Kinder. 2018. What makes a metaphor literary? Answers from two computational studies. Metaphor and Symbol 33(2). 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1434943.Search in Google Scholar

Jacoby, Larry L. & Kevin Whitehouse. 1989. An illusion of memory: False recognition influenced by unconscious perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 118(2). 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.118.2.126.Search in Google Scholar

Jacoby, Larry L., Lorraine G. Allan, Jane C. Collins & Linda K. Larwill. 1988. Memory influences subjective experience: Noise judgments. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 14(2). 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-7393.14.2.240.Search in Google Scholar

Jones, Lara L. & Zachary Estes. 2006. Roosters, robins, and alarm clocks: Aptness and conventionality in metaphor comprehension. Journal of Memory and Language 55(1). 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2006.02.004.Search in Google Scholar

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. London: Macmillan.Search in Google Scholar

Katz, Albert N., Allan Paivio, Marc Marschark & James M. Clark. 1988. Norms for 204 literary and 260 nonliterary metaphors on 10 psychological dimensions. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 3(4). 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms0304_1.Search in Google Scholar

Kintsch, Walter & Anita R. Bowles. 2002. Metaphor comprehension: What makes a metaphor difficult to understand? Metaphor and Symbol 17(4). 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327868MS1704_1.Search in Google Scholar

Kintsch, Walter. 2000. Metaphor comprehension: A computational theory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 7. 257–266. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03212981.Search in Google Scholar

Kittay, Eva Feder. 1987. Metaphor: Its cognitive force and linguistic structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Klikovac, Duška. 2004. Metafore u mišljenju i jeziku [Metaphors in thought and language]. Belgrade: Biblioteka XX vek.Search in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltan. 2010. Metaphor: A practical introduction, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltan. 2014. Conceptual metaphor theory and the nature of difficulties in metaphor translation. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 25–41. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Landauer, Thomas K. & Susan T. Dumais. 1997. A solution to Plato’s problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of the acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychological Review 104(2). 211–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.104.2.211.Search in Google Scholar

Lindqvist, Yvonne. 2014. Grammatical metaphors in translation: Cookery books as a case in point. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 167–180. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Manfredi, Marina. 2014. Translating lexical and grammatical metaphor in popular science magazines: The case of National Geographic (Italia). In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 151–167. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Milenković, Katarina. 2021. Odnos osobina metafore i njihovog razumevanja: Psiholingvistički pristup [The relation between metaphor features and their comprehension: A psycholinguistic approach]. Niš: University of Niš doctoral dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. 1980. The translation of metaphor. Babel 26(2). 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.26.2.05new.Search in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. 1988. A textbook of translation. New York: Prentice Hall International.Search in Google Scholar

Oliynyk, Tetyana. 2014. Metaphor translation methods. International Journal of Applied Science and Technology 4(1). 123–126.Search in Google Scholar

Petrović, Mihailo. 1967 [1933]. Metafore i alegorije [Metaphors and allegories]. Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga.Search in Google Scholar

Rasulić, Katarina. 2004. Jezik i prostorno iskustvo: Konceptualizacija vertikalne dimenzije u engleskom i srpskohrvatskom jeziku [Language and spatial experience: Conceptualization of the vertical dimension in English and Serbo-Croatian]. Belgrade: Filološki fakultet.Search in Google Scholar

Roncero, Carlos & Roberto G. de Almeida. 2015. Semantic properties, aptness, familiarity, conventionality, and interpretive diversity scores for 84 metaphors and similes. Behavior Research Methods 47. 800–812. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0502-y.Search in Google Scholar

Saeed, John I. 2009. Semantics, 3rd edn. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Samaniego Fernández, Eva, Marisol Velasco Sacristán & Pedro A. Fuertes Olivera. 2005. Translations we live by: The impact of metaphor translation on target systems. In Pedro A. Fuertes Olivera (ed.), Lengua y sociedad: Investigaciones recientes en lingüística aplicada, 61–81. Valladolid: University of Valladolid.Search in Google Scholar

Schäffner, Christina. 2004. Metaphor and translation: Some implications of a cognitive approach. Journal of Pragmatics 36(7). 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.012.Search in Google Scholar

Schäffner, Christina. 2014. Umbrellas and firewalls: Metaphors in debating the financial crisis from the perspective of translation studies. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 69–85. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Shuttleworth, Mark. 2017. Studying scientific metaphor in translation: An inquiry into cross-lingual translation practices. Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9781315678085Search in Google Scholar

Stamenković, Dušan, Katarina Milenković & Jovana Dinčić. 2019a. Studija normiranјa knјiževnih i neknјiževnih metafora iz srpskog jezika [A norming study of Serbian literary and non-literary metaphors]. Zbornik Matice srpske za filologiju i lingvistiku 62(2). 89–104.Search in Google Scholar

Stamenković, Dušan, Nicholas Ichien & Keith J. Holyoak. 2019b. Metaphor comprehension: An individual-differences approach. Journal of Memory and Language 105. 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2018.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Stamenković, Dušan, Katarina Milenković, Nicholas Ichien & Keith J. Holyoak. 2023. An individual-differences approach to poetic metaphor: Impact of aptness and familiarity. Metaphor and Symbol 38(2). 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2021.2006046.Search in Google Scholar

Stamenković, Dušan, Nicholas Ichien & Keith J. Holyoak. 2020. Individual differences in comprehension of contextualized metaphors. Metaphor and Symbol 35(4). 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2020.1821203.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard J. 2014. Translating metaphor: What’s the problem? In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 1–11. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard J., Aletta G. Dorst, J. Berenike Herrmann, Anna Kaal, Tina Krennmayr & Trijntje Pasma. 2010. A method for linguistic metaphor identification: From MIP to MIPVU. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/celcr.14Search in Google Scholar

Swain, Elizabeth. 2014. Translating metaphor in literary texts: An intertextual approach. In Donna R. Miller & Enrico Monti (eds.), Tradurre figure/Translating figurative language, 241–255. Bologna: Bononia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Tasić, Miloš & Dušan Stamenković. 2012. Odnos metafore i konteksta u kognitivnoj lingvistici [The relation between metaphor and context in cognitive linguistic literature]. Filolog 5. 234–247. https://doi.org/10.7251/FIL1205234T.Search in Google Scholar

Thibodeau, Paul H. & Frank H. Durgin. 2011. Metaphor aptness and conventionality: A processing fluency account. Metaphor and Symbol 26(3). 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2011.583196.Search in Google Scholar

Thibodeau, Paul H., Les Sikos & Frank H. Durgin. 2017. Are subjective ratings of metaphors a red herring? The big two dimensions of metaphoric sentences. Behavior Research Methods 50. 759–772. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0903-9.Search in Google Scholar

Tourangeau, Roger & Robert J. Sternberg. 1981. Aptness in metaphor. Cognitive Psychology 13(1). 27–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(81)90003-7.Search in Google Scholar

Tourangeau, Roger & Robert J. Sternberg. 1982. Understanding and appreciating metaphors. Cognition 11(3). 203–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(82)90016-6.Search in Google Scholar

Utsumi, Akira. 2007. Interpretive diversity explains metaphor–simile distinction. Metaphor and Symbol 22(4). 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926480701528071.Search in Google Scholar

Vidanović, Ðorđe. 1995. Metaphoring and metaphor: A research proposal. Facta Universitatis, Series: Linguistics and Literature 1(2). 158–162.Search in Google Scholar

Vlajković, Ivana & Dušan Stamenković. 2013. Metaphorical extensions of the colour terms black and white and in English and Serbian. Zbornik radova sa Šestog međunarodnog interdisciplinarnog simpozijuma Susret kultura, 1, 547–558. Novi Sad: Filozofski fakultet.Search in Google Scholar

Wolff, Phillip & Dedre Gentner. 2000. Evidence for role-neutral initial processing of metaphors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 26(2). 529–541. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.26.2.529.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese