Abstract

In this article, we investigate if conversational priming in repetitional responses could be a factor in language change. In this mechanism, an interlocutor responds to an utterance by the other interactant using a repetitional response. Due to comprehension-to-production priming, the interlocutor producing the repetitional response is more likely to employ the same linguistic variant as the interlocutor producing the original utterance, resulting in a double exposure to the variant which, in turn, is assumed to reinforce the original priming effect, making the form more familiar to the repeating interlocutor. An agent-based model, with interactions shaped as conversations, shows that when conversational priming is added as a parameter, interlocutors converge faster on their linguistic choices than without conversational priming. Moreover, we find that when an innovative form is in some way favoured over another form (replicator selection), this convergence also leads to faster spread of innovations across a population. In a second simulation, we find that conversational priming is, under certain assumptions, able to overcome the conserving effect of frequency. Our work highlights the importance of including the conversation level in models of language change that link different timescales.

1 Introduction

As face-to-face conversation is the prime habitat for language (e.g., Dingemanse et al. 2023; Pickering and Garrod 2004; Schegloff 2006) it must provide affordances for linguistic innovations to spread from one person to another (in addition to mechanisms for stabilizing linguistic forms), given that we observe that languages change over time (Pleyer 2023). In this paper, we study the specific mechanism of conversational priming in repetitional responses (based on Gipper 2020), a mechanism in which interlocutors influence each other’s linguistic choices, as a possible factor in language change. Using subject marking as a test case, we evaluate if and under what conditions conversational priming can foster the spread of innovations, in an agent-based model where language users communicate using interactions structured as conversations. We find that conversational priming speeds up the convergence between innovative and conservative interlocutors in a population and can, under the assumption that priming effects are amplified in repetitional responses due to lexical boost effects (Hartsuiker et al. 2008; Mahowald et al. 2016), make an already privileged innovative form take over faster, so this mechanism could plausibly play a role in accelerating the spread of innovations across a community. We also investigate the interaction between conversational priming and frequency of use, finding that conversational priming can under some circumstances counter the conserving effect of frequency.

1.1 Conversational priming in repetitional responses

During conversation, interlocutors may align their behaviours at many levels (Rasenberg et al. 2020).[1] It has been proposed by various authors that convergence of linguistic choices at the level of the conversation may have long-term effects in the form of spread of linguistic innovations (e.g., Auer and Hinskens 2005; Nilsson 2015; Pickering and Garrod 2017; Trudgill 1986). As a specific mechanism, it has been suggested that repetitional responses in conversation may cause interlocutors to become more similar to each other in the course of a conversational exchange (Gipper 2020). Repetitional responses consist of a repetition of (part of) the previous interlocutor’s utterance. They can be used to perform different actions in conversation, one of them being answering polar questions instead of using particles such as yes or no (see, e.g., Holmberg 2016: 62–72).

There is evidence that repetitional responses are employed in all languages, albeit probably to different extents (Enfield et al. 2019) and with different interactional imports (Brown et al. 2021; Dideriksen et al. 2023; Raymond 2003). The following example illustrates the existence of repetitional responses as answers to polar questions in English:

| She: You’re back in town? | |

| He: I’m back in town. | (Schegloff 1996: 184) |

Because exposure to a form facilitates its subsequent use through immediate comprehension-to-production priming effects (Bock 1986; Jacobs et al. 2019; Kaschak et al. 2014; Mahowald et al. 2016), there is an incentive for the responding interlocutor to use the same linguistic material (e.g., the same verb form) that was employed in the question, even if this is a form they would not have used otherwise. Such comprehension-to-production priming has been found to occur in answers to content questions (Chia and Kaschak 2022; Levelt and Kelter 1982), so it is plausible to assume that it occurs in other types of interactional sequences as well. Not using the same form may also be seen as performing undesired additional actions, such as correcting the interlocutor (Gipper 2020). Thus, conversational priming through repetitional responses combines automatic priming effects with social motivations, such as attitude towards the interlocutor (Branigan et al. 2011; Kim and Chamorro 2021).

Now, when the answering interlocutor uses this form after hearing it, the priming effect will be reinforced further, as there are now two occurrences of the form, one in perception, the other in production (Bock et al. 2007).[2] We thus propose to define Conversational priming as the effect of comprehension-to-production priming first facilitating the use of a linguistic form, which then reinforces the priming effect by way of self-priming through production in repetitional responses if the form is repeated rather than deleted or replaced by a different form. At the same time, the other interlocutor, who uttered the form for the first time, is also exposed to the same form for a second time, by which this form is reinforced for them as well. However, for this interlocutor, we expect the mechanism to most likely reinforce an already strong form, as it is the form chosen from that interlocutor’s probability distribution. While we expect the mechanism of conversational priming to be at work in all cases of cross-interlocutor repetition in conversation, repetitional responses constitute a sequentially structured type of repetition. In such a context, the use of a different form may be more salient, which thus may increase the pressure on language users to employ the same form.

Conversational priming depends on the psycholinguistic mechanism of priming, but each takes place in its own causal frame (cf. Enfield 2014: 13–15): comprehension-to-production and self-priming occur at the level of processing (microgenetic), while conversational priming takes place at the level of the conversation (enchronic). Because of this ontological difference, conversational priming has qualitatively different characteristics than priming, even though it depends on it as a mechanism. Whereas the psycholinguistic effect of priming is automatic and thus obligatory, copying a form through conversational priming is not obligatory.

1.2 Conversational priming scaling up to language change

On a longer-term basis, if an interlocutor is repeatedly nudged in this way to use a new form, the form may become familiar to them and they may use it actively in future interactions and pass it on to other individuals. We base this assumption on the available evidence that such cumulative priming can persist for up to a week (at least when the same task is applied), thus influencing an individual’s choices beyond the immediate context of local comprehension-to-production priming (Kaschak et al. 2011, 2014). A role for priming in language change has been proposed by various authors before (Baumann and Sommerer 2018; Jäger and Rosenbach 2008; Kootstra and Şahin 2018; Pickering and Garrod 2017).

Following Gipper (2020), we propose that repetitional responses can give rise to convergence at the enchronic level (level of the conversation; see Enfield 2014), with the potential of this convergence to scale up to the community at the diachronic level, thus connecting causal frames of language at different timescales. The uniformity of mechanisms between short-term language processing and language change on longer timescales has been shown for the semantic domain (Brochhagen et al. 2023) and has been argued to be of key importance to the study of language change in general (Greenhill 2023). Our first computer model will test the influence of conversational priming on convergence across a population, contrasting situations with conversational priming (double exposure to form, in comprehension and production) and without (single exposure to form, in comprehension only).

But faster convergence between interlocutors acts on both conservative and innovative forms. As Blythe and Croft (2012) show, using a formal model in some ways similar to the agent-based model we will present in this paper, only Replicator selection – favouring the innovative linguistic variant over the conservative one – makes the innovative variant take over in the well-known S-curve. The differential treatment of variants can be attributed to different factors, such as social prestige, analogy to other forms, ease of production, and so on (for a summary, see Blythe and Croft 2012: 272–273). In a second model, we test the effect of conversational priming in a situation where the innovative form is privileged over the conservative form in a population.

1.3 Test case: subject marking in repetitional responses

Because priming acts at all levels of linguistic representation (Pickering and Garrod 2004), conversational priming can be assumed to influence language change at all of these levels, including syntax (Kootstra and Şahin 2018), morphosyntax (Adamou et al. 2021), semantics, and phonetics (Jäger and Rosenbach 2008). In this paper, we focus on subject marking in the context of repetitional responses as a test case.

Subject marking of the person of the subject on the finite verb (Siewierska 2013; e.g., walk-s, with -s marking the third person singular) allows the role of conversational priming in language change to be tested, for at least two reasons. First, conversational priming in repetitional responses is expected to work only on the third person (Hill 2022), so in subject marking, outcomes for the third person can clearly be contrasted with other grammatical persons. Second, whereas we expect that conversational priming may under certain circumstances make innovations in the third person spread across a community, frequency would make the opposite prediction, that the third person should be the most conservative because it is most frequent. As discussed, we believe conversational priming can also cause language change in other domains than subject marking. However, even within the context of repetitional responses, other domains (such as tense marking, lexical, or phonetic phenomena) do not exhibit the same asymmetry, allowing mechanisms to be kept apart and contrasted. We will now elaborate further on person asymmetry and frequency.

Person asymmetry In repetitional responses, conversational priming can be expected to impact in an asymmetric fashion on different person-number combinations in subject markers: only the third person, which is the same in question and answer, allows for conversational priming. First and second person forms, in contrast, do not get repeated, as they will usually replace each other from question to answer (Hill 2022). Consider the following two examples from conversations in Yurakaré (isolate, Bolivia; see, e.g., van Gijn 2006):[3]

| adojla | bali- p |

| on_top | go-2pl.sbj |

| ‘Did you (pl.) walk?’ | |

| adojla | bali -tu | |

| on_top | go-1pl.sbj | |

| ‘We walked.’ | (van Gijn et al. 2011 – Conversation-NL) | |

In (2), interlocutor A uses a second person plural form, so interlocutor B has to reply with a first person plural. Due to this deictic shift, there is no reuse of subject marker and no conversational priming is taking place.

| dula -w =la |

| make-3pl.sbj=indeed |

| ‘Did they build it?’ |

| dula -w | |

| make-3pl.sbj | |

| ‘They built it.’ | (van Gijn et al. 2011 – YURGVDP08oct06-01) |

In (3), because A uses the third person plural form, the reply will also contain third person plural. This symmetry in person marking between question and answer allows for conversational priming. If interlocutor A uses an innovative variant, the repeat may nudge interlocutor B to also use this innovative variant. If repetitional responses indeed lead to convergence in conversation and can thus foster the spread of linguistic innovations, we expect that this effect can be observed for the third person, but not for the first and second person, which do not get repeated in a repetitional response.

Frequency Another factor that plays a role in the change of subject markers, and possibly interacts with conversational priming, is frequency of use. High frequency of use has a conservative effect on morphology: by frequent use, the representations of irregular forms are reinforced and thus protected from regularization (Bybee and Thompson 1997; Diessel 2007: 117–123; Hoekstra and Versloot 2019). Moreover, it has been shown for verbal morphology that forms with high token frequency are likely to replace forms with lower frequency, while the process in the other direction is less likely (Sims-Williams 2016, 2022).[4]

There is some evidence from Russian (Seržant and Moroz 2022),[5] American English (Scheibman 2001),[6] and British English (Leech et al. 2001)[7] that the third person singular is the most frequently used subject in spoken language. To add another data point, we conducted an exploratory study of nominal expressions in subject position in the Spoken Dutch Corpus (CGN; Hoekstra et al. 2001; Oostdijk 2000), also suggesting that 3sg is the most frequent subject.[8] Based on the fragmentary evidence available, we may make a conditional statement: if we assume that 3sg is indeed the most frequent form, we would predict that 3sg is the most conservative person because of the conserving effect of frequency. In this way, frequency could act as an antagonistic force to conversational priming. Initial evidence suggests that 3sg may indeed be the most conservative person crosslinguistically (Dekker et al. 2024).

2 Agent-based model of conversational priming

2.1 Motivation

There is some anecdotal evidence of instances of language change where 3sg changes faster than other subject markers and conversational priming could thus be at play. In the Lithuanian dialect of Lazūnai (Vidugiris 2014: 198–200), for the verb eĩti ‘to go’, the 3sg/pl form eĩti has been replaced by an innovative form eĩma, while all other subject markers stayed the same (compared to the conservative dialect of Zietela; Rozwadowski 1995: 136).[9]

Another example of faster change of 3sg, observed at least in Indo-European languages and possibly crosslinguistically, is Watkins’s law (Bickel et al. 2015; Watkins 1962: 90–96), the tendency of the 3sg person marker to be reanalysed as part of the stem. This reanalysis changes the 3sg person marker to zero, while other markers stay the same, making it the most innovative form.

Inspired by these two examples, we would like to explore under which conditions conversational priming is able to foster spread of innovations (predicted to be faster in third person) and thus override the conserving effect of frequency on the third person. Empirically investigating these processes is difficult, because they occur across large time spans and are influenced by many factors. Therefore, we construct an agent-based model (Smith 2014) of communication in a population, with interactions structured as conversations. We study how mechanisms in conversations between agents can lead to the spread of an innovation, once that innovation has already been introduced (cf. Harrington and Schiel 2017).

2.2 Basic model

In the agent-based model, we consider a simplified situation: a population of agents (default: 100) communicate in question-answer pairs about three concepts, 1sg, 2sg, and 3sg, where each concept is represented by a distinct form (no syncretism) and thus only 3sg allows for conversational priming. These three grammatical persons are an abstraction of all possible grammatical persons (including plural, dual, and inclusive/exclusive). Each concept can be expressed by two forms: a conservative and an innovative form. We evaluate how the use of the innovative form, initially employed only by some individuals in the population, changes over the course of interactions in the simulation.

Each agent is fully characterized by one value: its probability of using the innovative form (the probability of using the conservative form is the complement of this probability; that is, they sum to 1). A minority of the agents (20 %) are innovators,[10] initialized with a probability of using innovative forms of 90 %. A majority of the agents (80 %) use only the conservative form (probability of innovative form: 0 %), which we call, with a slight deviation from the original meaning, conservators. Innovators and conservators only differ from each other in their initialization; their probability distribution can change later in the simulation.

A simulation consists of 1,000 timesteps. In every timestep, every agent consecutively engages in conversation with a randomly chosen other agent in the population.[11] Interactions are structured as conversations, where the agent who initiates the conversation poses a question and the agent who is addressed answers using a repetitional response (see Table 1).[12] For 1sg and 2sg, no conversational priming takes place: agent B uses a form from its own probability distribution. For 3sg, conversational priming does take place: B uses the same form as A. As an abstraction in our model, we evaluate the most extreme case where conversational priming is performed categorically: an agent responding to 3sg always copies the form it heard. As we assume copying through conversational priming is in principle not obligatory, we also tested the situation where comprehension-to-production priming only increases the probability of responding with the same form (see Section 2.6 in the supplementary material) and found results which were not qualitatively different.

Structure of one interaction between agent A (initiator) and agent B (addressee) in the agent-based model.

| Agent A | Agent B |

|---|---|

| A1. Randomly sample person (1/2/3sg) A2. Sample form from probability distribution for this person A3. Send form to agent B A4. Increase probability of sent form |

|

|

|

| B1. Increase probability of received form B2. Determine person to answer (1→2, 2→1, 3→3) B3. If person different (=1/2sg): No conversational priming: Sample form from probability distribution Else: (=3sg) Conversational priming: Use form from question B4. Send form to agent A B5. Increase probability of sent form |

|

|

|

| A5. Increase probability of received form |

Priming effects in syntactic priming have been shown for perception (comprehension-to-production priming) as well as for production (self-priming; Bock et al. 2007; Jacobs et al. 2019; see also footnote 2 above), so we assume a two-way priming effect for conversational priming as well: both when perceiving and producing a form, the probability of that form is increased (by default by 0.01) and the probability of the other form is thus decreased (the formula is available in Section 2.3 of the supplementary material). The insight that competition between linguistic items within individuals can lead to language change has a long tradition in the computational modelling of language evolution (Batali 2002; De Vylder and Tuyls 2006; Steels 1998). An example of such a model, which also studies the domain of morphology, although not specifically priming, is van Trijp (2016). In van Trijp’s model, on establishing a successful interaction, agents update the probability of a construction while lowering the probabilities of all competing constructions (lateral inhibition; van Trijp 2016: 78–79), whereas in our model it is performed for both agents and in every interaction.

Assuming that the forms perceived and produced in an interaction lead to immediate changes in the internal model of the agents is furthermore in line with theories proposing an implicit-learning account of priming, where each exposure to a form leads to a change in weights of the language production model, which influences their language use in future interactions (Chang 2008; Chang et al. 2000, 2006; Jaeger and Snider 2013). Therefore, in our model, we assume that the higher-level phenomenon of conversational priming bundles a range of low-level priming events on the processing level (comprehension-to-production as well as self-priming) and will have an immediate long-lasting effect.

2.3 Replicator selection model

As discussed in Section 1.2, replicator selection, where one of the forms is favoured over the other, is needed for a form to take over in a population (Blythe and Croft 2012). We extend the basic model by adding replicator selection, being agnostic as to which of the factors is responsible for the privilege in the innovative form. We assume that a favoured form is characterized by a higher level of activation, both in production and comprehension. In this model with replicator selection, we favour the innovative form by performing a larger probability increase (2 × , totalling 0.02) for the innovative than for the conservative form, in both comprehension and production for both agents.

Additionally, we experiment with a variation of the replicator selection model where an amplified probability increase is performed during production for conversational priming, that is, for the production of the repetitional response. This finds support in studies that show stronger priming effects for semantically closer concepts (in this case twice the same concept; Cleland and Pickering 2003) and for reused lexical items (lexical boost; Hartsuiker et al. 2008; Mahowald et al. 2016). The interlocutor performing conversational priming in production performs 2 × the probability increase that would otherwise be performed, which is already 0.02 for the innovative form in the replicator selection model, totalling a 0.02 increase for the conservative and a 0.04 increase for the innovative form.

Table 2 shows the parameter settings used in the basic model, the replicator selection model, and the replicator selection model with amplified production increase. Additionally, we report the parameter settings for the frequency model we will introduce in Section 3, which builds further on the replicator selection model with amplified production increase.

Parameters used in variants of the model: basic model, replicator selection model (RS), replicator selection model with amplified production increase (RS + API), and frequency model (based on RS + API). Boldface values indicate that they are different from the default value.

| Parameter | Basic | RS | Model RS + API |

Frequency (+RS + API) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability increase (conversational priming production) | ||||

| Conservative form | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Innovative form | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Probability increase (other) | ||||

| Conservative form | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Innovative form | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Decay 1/2sg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.01 |

| Decay 3sg | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.015 |

2.4 Results

The results for the basic model are shown in Figure 1a, where 1sg and 3sg are plotted, because the behaviour of 2sg is the same as 1sg. The results show that the languages of the innovators and conservators converge to the population mean with the probabilities of the agents evening out, an effect that can also be substantiated with mathematical analysis (see Section 2.4 in the supplementary material). Convergence is faster, in two ways, for the person for which conversational priming takes place (3sg) than for other persons (1sg, 2sg). First, the languages of innovators and conservators, as measured by their communicated utterances, move towards each other faster. Second, all agents converge faster to the convergence point of the simulation: the population mean. Mathematical analysis (Section 2.4 in the supplementary material) confirms that 3sg moves faster towards the population mean than 1/2sg. These two types of faster convergence can serve as evidence for convergence on linguistic conventions through conversational priming. However, the innovative form does not become the dominant form in the population: the S-shaped curve typical of language change (Aitchison 2001: 91–97, 107–110) is not observed in the basic model. Note that, for 3sg, the proportions of communicated innovative forms for the innovators and conservators make a large jump towards each other already in the very first timestep. This is caused by copying through conversational priming, notably the minority (20 %) of innovators copying the conservative forms of the majority (80 %) of conservators. The jump is so sudden because the innovators and conservators have fundamentally different languages. This is a situation that only happens in the real world when two groups using different but mutually intelligible languages are separated and then suddenly come into contact. An example of this is dialect contact, such as the contact between qualitatively different British English dialects leading to the emergence of New Zealand English (Trudgill 2004).

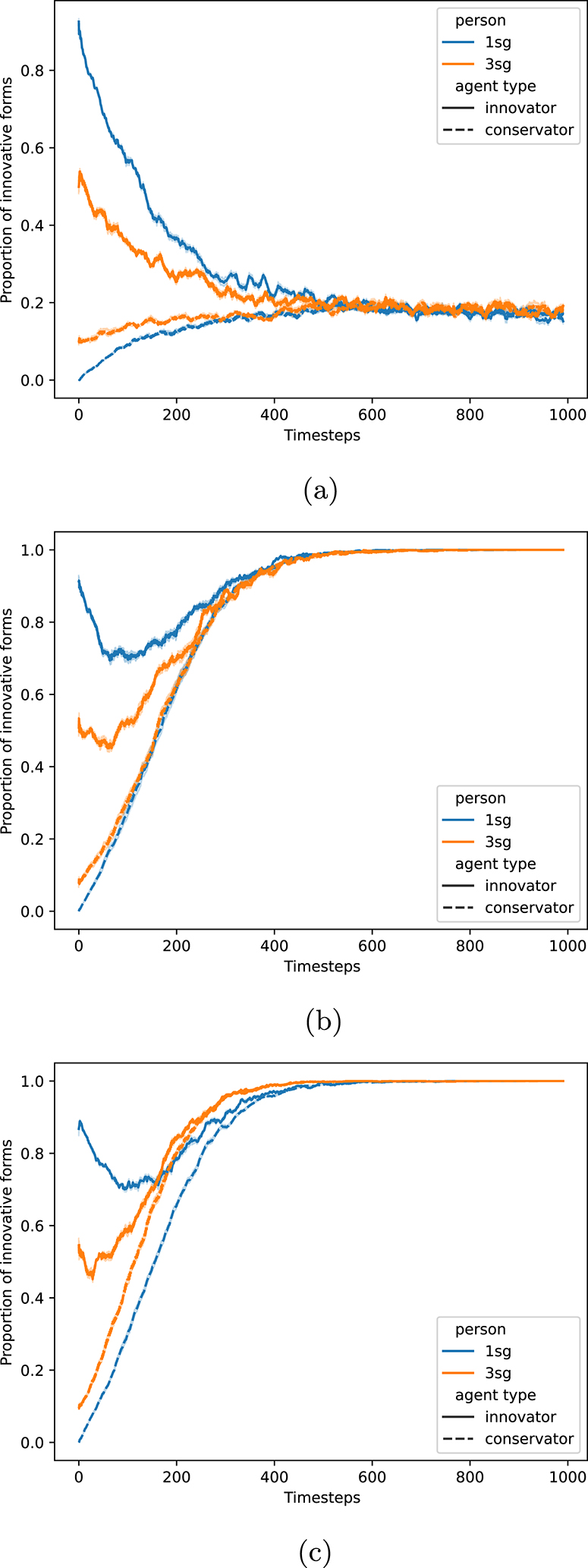

Proportion of innovative forms communicated for agents initialized as innovators and conservators over timesteps, for different model variations. Only in 3SG does conversational priming take place. Note that for all three models, 3SG (orange) makes a jump in the first timestep due to conversational priming (see main text). 95 % confidence interval over 100 runs, running average over 20 timesteps. (a) Basic model. (b) Replicator selection model. (c) Replicator selection model plus amplified production increase.

The results for the replicator selection model are shown in Figure 1b. Conversational priming makes the language of the innovators and conservators converge considerably faster towards each other, like in the basic model. Now, with replicator selection, the innovative form is also able to take over, after an initial dip in the proportion of innovative forms when the influence of (initially very conservative) conservators is stronger than the effect of favouring the innovative form. Note that in this model, conversational priming is not yet able to converge faster to the point where the innovative form has fully taken over.

Figure 1c shows the replicator selection model with the amplified production increase for conversational priming: in this model, in addition to the innovators and conservators moving towards each other faster, the conversational priming model (3sg) also converges faster to a proportion of innovative forms of 1.0. This means that the replicator selection with the added assumption of a larger probability increase in conversational priming production leads to a dynamic where the innovative form becomes dominant and where conversational priming makes the innovative form take over faster for 3sg than for 1sg.

3 Agent-based model of conversational priming versus frequency

3.1 Model

Now we have seen that conversational priming speeds up convergence between innovators and conservators and can lead to a faster takeover of the innovative form, we would like to contrast conversational priming with frequency of use as a force protecting frequent conservative forms from being replaced by innovations. We will study the impact of the concept frequency of the subject markers (1sg, 2sg, 3sg), not the frequency (implemented as a probability in the model) of the two morphological variants (conservative, innovative). As discussed in Section 1.3, assuming that 3sg is most frequent, this would be the most conservative grammatical person, while conversational priming would predict 3sg to be the most innovative person (given an existing preference for the innovative form). We would like to explore under which circumstances conversational priming is a factor that can compensate for the conserving effect of frequency of use.

We implement the conserving effect of frequency of use by a decay mechanism. Decay has been suggested as an important mechanism in language processing, which has been instantiated in different ways for different research questions, for example for learning form-meaning mappings (Rasilo and Räsänen 2015) and in the relationship between language change and community size (Reali et al. 2018). In our model, we defined our own implementation of decay: every timestep, for every grammatical person (1/2/3sg) the probability of the form (innovative or conservative) with the lowest probability in the distribution is somewhat decreased. Decay acts on all grammatical persons, but the probability decrease is stronger for high-frequency 3sg (0.015) than for lower-frequency 1/2sg (0.01). The rationale behind modelling the conserving effect of concept frequency by decay, with a higher decay for higher frequency concepts, is as follows. The frequent use of the more frequent concept, 3sg, protects its more probable variant (which differs for innovators and conservators) by penalizing the less probable competing variant with a higher decay. For an innovator, with a high probability for the innovative form, the probability of the conservative form is strongly pushed down, protecting the already strong innovative form. For a conservator, the probability of the innovative form is strongly pushed down, protecting the conservative form. For the less frequent concepts (1/2sg), decay also applies to the less probable variant, so the same effects apply, but the probability is pushed down less: less protection of the most probable form takes place in the less frequent concepts. As discussed, the decay mechanism has an opposite effect on the languages of innovators and conservators. As the population initially has a majority of conservators, the effect of the higher decay for high-frequency concepts is expected to be a more conservative language in the whole population and slower convergence.

The agent-based model presented by van Trijp (2016: 94) also uses decay, but implemented in a somewhat different way. In van Trijp’s model, a token frequency count is increased after successful interactions; this frequency count determines the constructions that are most likely to be produced. Every 50 interactions, the decay starts to act by decreasing all frequency scores. In our model, decay is modelled by only decreasing the count for the least probable variant for a concept (rather than all variants) and immediately works from the first interaction. Decay in our model is also a way of modelling the conserving effect of frequency, while van Trijp models decay and frequency as two separate factors.

3.2 Results

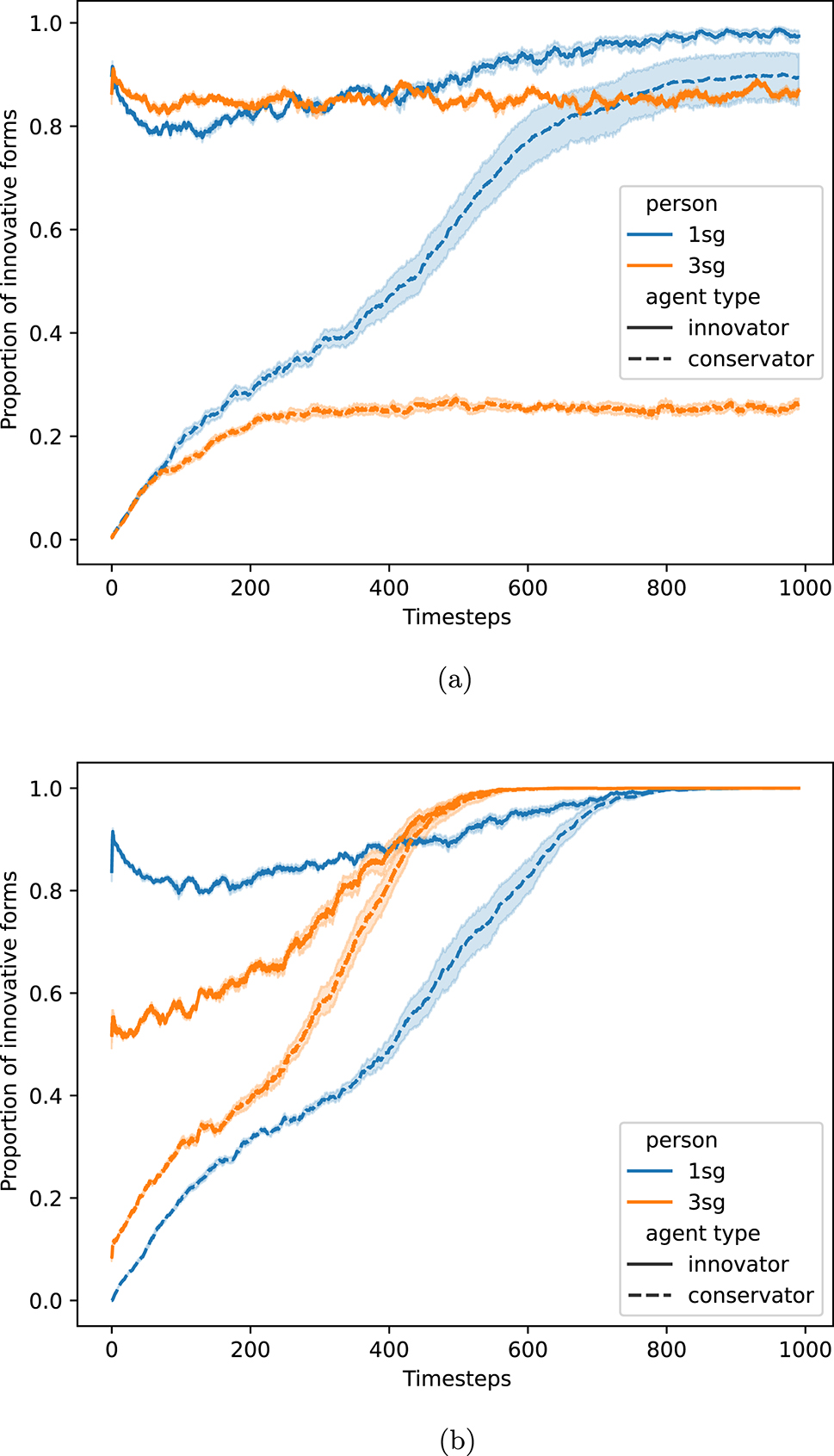

We use the replicator selection model with amplified production increase during conversational priming (see Figure 1c) and add the decay mechanism to this model. First, we evaluate the effect of the decay mechanism when conversational priming is fully disabled, both for 1sg and 3sg (Figure 2a). Concept frequency, modelled by the stronger decay for frequent 3sg, is able to fully neutralize the S-curve for 3sg, showing a dynamic which is conservative and less converging (towards each other and towards the innovative form). 1sg, with lower concept frequency (modelled by lower decay), is able to converge to a proportion of innovative forms of 1.0, following a slowed-down trajectory of the usual S-curve. Figure 2b, the same model, but with conversational priming enabled for 3sg, shows that conversational priming is able to overcome the conserving effect of frequency and the dynamic for 3sg turns into an S-curve again, even faster than 1sg. This model provides evidence that conversational priming could under some circumstances counter the conserving effect of frequency and foster the spread of innovative forms, once an innovation has taken place.

Decay model: replicator selection model with amplified production increase for a decay of 0.015 for 3SG and 0.01 for other persons. Conversational priming, if turned on, only works on 3SG. Y-axis: proportion of innovative forms communicated by agents initialized as innovators and conservators over timesteps. (a) No conversational priming (for any of the persons). (b) Conversational priming (only for 3SG, as in other experiments).

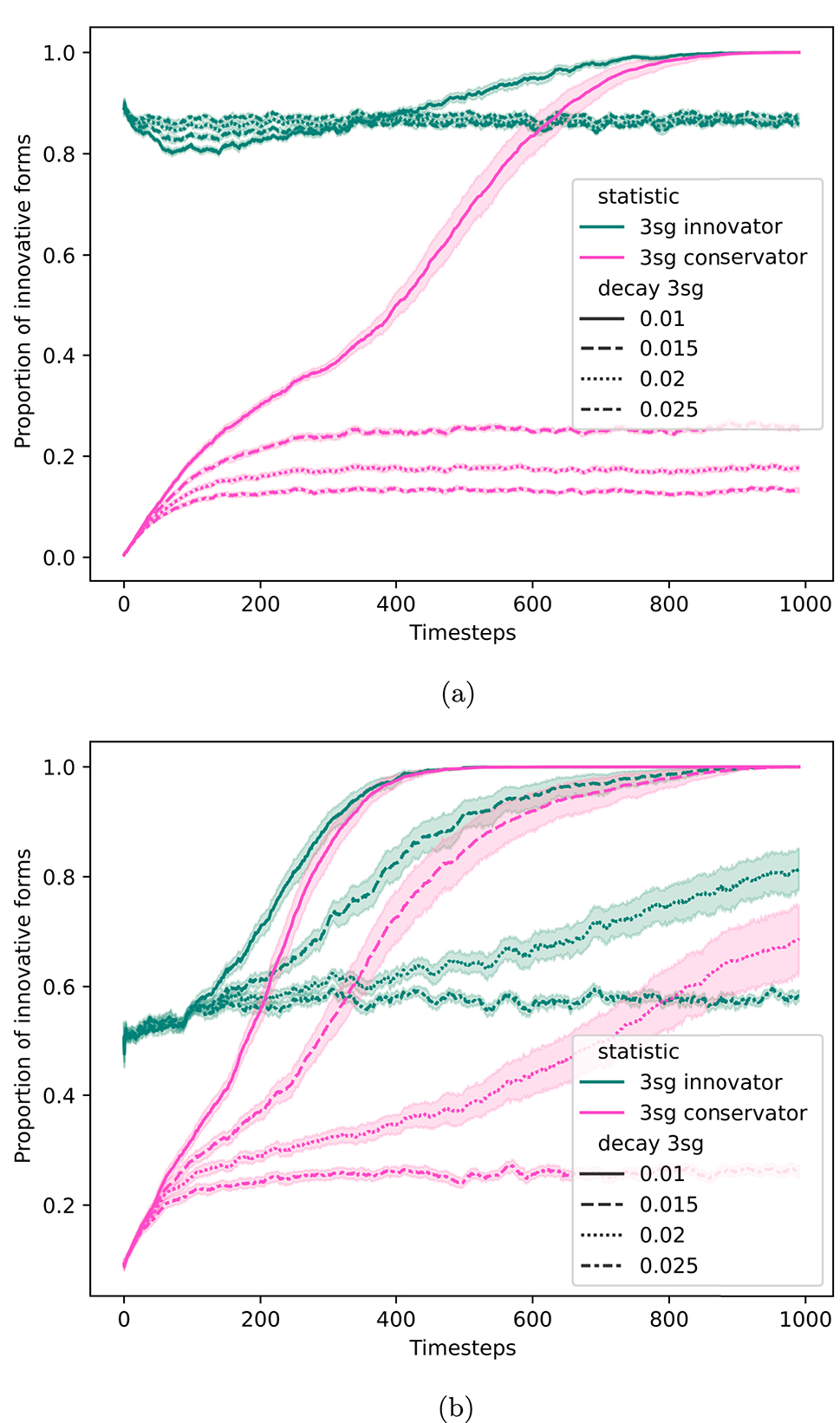

However, the model is sensitive to the magnitude of the decay for the different persons: only for certain values is the effect of frequency strong enough to slow down convergence, while it can still be countered by conversational priming. When varying the decay for 3sg, it becomes clear that for decay values lower than 0.015, the conservative dynamic does not emerge in the model without conversational priming (Figure 3a), while for values higher than 0.02, the innovative form does not take over in the model with conversational priming (Figure 3b). The sensitivity of the model behaviour to the decay value, which represents frequency, corresponds with real-world evidence that the relationship between frequency and conservation of archaic forms is not always linear. For the English plural, Versloot and Adamczyk (2018: 41–42) find a steeply sloped S-curve for the relationship between frequency and likelihood to use an archaic form: this indicates that in certain areas of the parameter space, a small difference in frequency can have a large effect on the likelihood of using an archaic form.

Evaluation of decay values for 3SG. Showing only language of 3SG. Replicator selection model with amplified production increase. Y-axis: proportion of innovative forms communicated by agents initialized as innovators and conservators over timesteps. (a) No conversational priming. (b) Conversational priming.

4 Discussion and conclusion

To explore under which conditions conversational priming could lead to faster convergence and spread of innovations in a population, we constructed an agent-based model which simulates question-answer interactions between interlocutors.

Under the assumptions of the model, conversational priming leads to faster convergence in the language of innovators and conservators. Conversational priming on its own, however, does not lead to a faster spread of innovations, as it applies equally to conservative and innovative forms. In contrast, our results show that if the innovative form already has an inherent benefit (either of social or language-internal nature) and the priming effects are strong enough, including an amplified production increase for the repeated form, conversational priming can lead to a faster spread of an innovative form. The amplified production increase, in which the repeating interlocutor gets a stronger probability increase in production during conversational priming, is supported by the priming literature (Cleland and Pickering 2003; Hartsuiker et al. 2008; Mahowald et al. 2016) and, according to our results, must form part of conversational priming if indeed it results in a faster spread of innovations across a population. The model seems relatively stable across parameters that were explored and the influence of some parameters can be formally analysed using mathematical analysis (see Sections 2.4–2.7 in the supplementary material).

Moreover, by adding frequency effects to the model, modelled by stronger protection of the most probable (morphological) variant in more frequent grammatical persons, we showed that conversational priming could under some circumstances counter the conserving effect of frequency and let an innovative form take over in a population. The relatively limited range of parameter settings for which this is possible shows that the balance between frequency and conversational priming is delicate. This could explain why, assuming conversational priming plays a role in language change, the effect of frequency (i.e., a stable 3sg person marker) seems to be observed more commonly across languages (Baerman 2005; Dekker et al. 2024; Sims-Williams 2022).

An important contribution of our work is that we have modelled in a simulation how conversational mechanisms, at the enchronic level (Enfield 2014), could eventually lead to language change at the diachronic level. Others have modelled how individual cognitive mechanisms can lead to language change (e.g., Baxter et al. 2009; Hruschka et al. 2009), but the novel contribution of our approach is the focus on the conversational structure of the interaction.

As we abstracted away many factors in creating a model with this broad scope across timescales, it could be worthwhile to develop models of specific steps in this chain of events. For example: how exactly is an innovation in a conversation internalized within an individual and how likely is an individual to use that innovation again with other interlocutors, from different social groups? Moreover, surprisal could be explored as a cognitively plausible update mechanism during priming, as this has been shown to play a critical role in language processing and priming (Bernolet and Hartsuiker 2010; Jacobs et al. 2019; Jaeger and Snider 2013; Wilcox et al. 2023). Iterated learning computer models and laboratory experiments of transmission of linguistic items over generations (e.g., Motamedi et al. 2019; Reali and Griffiths 2009) may be promising methods to study the precise propagation through a population.

In addition to narrowing down to the specific steps in the process of conversational priming, it could also be interesting to extend the model from a single language to language contact settings and study the role of cross-language priming in contact-induced change (Adamou et al. 2021; Kootstra and Şahin 2018; Loebell and Bock 2003; Travis et al. 2017). Finally, to include the second, phonetic reduction effect of frequency, a model with a sequential, phonology-like, representation of subject markers could be explored. Our model is a first attempt to study computationally how conversational mechanisms lead to language change in the longer term. We hope this question will be further investigated using new approaches, such as the ones we sketched above.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article is hosted by the journal. It contains technical details of the model, a mathematical analysis of the model behaviour and an evaluation of parameters. Additionally, it provides details on a corpus analysis of person frequency, which is used as supporting evidence in Section 1.3.

All code can be found in Zenodo repository https://zenodo.org/records/13284173 and GitHub repository https://github.com/peterdekker/conversationalpriming.

Funding source: University of Cologne, Excellent Research Support Program

Award Identifier / Grant number: Cluster Development Program: Language Challenges

Award Identifier / Grant number: FORUM: Conversational priming in language change

Funding source: Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek

Award Identifier / Grant number: PhD Fellowship fundamental research (11A2821N)

Funding source: Volkswagen Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: 81821

Award Identifier / Grant number: 83448

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their inspiring comments. We would also like to thank the audiences of our presentations at the Meertens Institute and the University of Cologne for their useful feedback. We are furthermore grateful to Eugen Hill and Pascal Coenen for many interesting discussions on the topic. Thanks to Frans Hinskens, Marieke Woensdregt, Marlou Rasenberg, Sho Akamine, and Aslı Özyürek for feedback on this work and to Jesse de Does and Bob Boelhouwer for advice on the CGN corpus analysis. All remaining errors are ours.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: PD performed: conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, investigation, writing (draft), visualisation. SG performed: conceptualisation, methodology, validation, writing (review & editing). BdB performed: supervision, formal analysis, writing (review & editing). All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The Yurakaré data reported in examples (2) and (3) were collected with funding from the Volkswagen Foundation (grant numbers 81821 and 83448). PD was supported by a PhD Fellowship fundamental research (11A2821N) of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). SG’s work was funded by the University of Cologne Excellent Research Support Program, funding line FORUM, project “Conversational priming in language change”, as well as funding line Cluster Development Program, project “Language challenges”.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Adamou, Evangelia, Quentin Feltgen & Cristian Padure. 2021. A unified approach to the study of language contact: Cross-language priming and change in adjective/noun order. International Journal of Bilingualism 25(6). 1635–1654. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069211033909.Search in Google Scholar

Aitchison, Jean. 2001. Language change: Progress or decay? 3rd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511809866Search in Google Scholar

Ambrazas, Saulius, Gražina Belickienė, Elena Grinaveckienė, Aldona Jonaitytė, Jonina Lipskienė, Kazys Morkūnas, Birutė Vanagienė & Aloyzas Vidugiris. 1991. Lietuvių kalbos atlasas. iii. morfologija [Lithuanian language atlas. III. Morphology]. Vilnius: Mokslas.Search in Google Scholar

Auer, Peter & Frans Hinskens. 2005. The role of interpersonal accommodation in a theory of language change. In Peter Auer, Frans Hinskens & Paul Kerswill (eds.), Dialect change: Convergence and divergence in European languages, 335–357. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486623.015Search in Google Scholar

Baerman, Matthew. 2005. Typology and the formal modelling of syncretism. In Geert Booij & Jaap van Marle (eds.), Yearbook of morphology 2004, 41–72. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/1-4020-2900-4_3Search in Google Scholar

Batali, John. 2002. The negotiation and acquisition of recursive grammars as a result of competition among exemplars. In Ted Briscoe (ed.). Linguistic evolution through language acquisition, 111–172. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511486524.005Search in Google Scholar

Baumann, Andreas & Lotte Sommerer. 2018. Linguistic diversification as a long-term effect of asymmetric priming: An adaptive-dynamics approach. Language Dynamics and Change 8(2). 253–296. https://doi.org/10.1163/22105832-00802002.Search in Google Scholar

Baxter, Gareth J., Richard A. Blythe, William Croft & Alan J. McKane. 2009. Modeling language change: An evaluation of Trudgill’s theory of the emergence of New Zealand English. Language Variation and Change 21(2). 257–296. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095439450999010X.Search in Google Scholar

Bernolet, Sarah & Robert J. Hartsuiker. 2010. Does verb bias modulate syntactic priming? Cognition 114(3). 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.11.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bickel, Balthasar, Alena Witzlack-Makarevich, Taras Zakharko & Giorgio Iemmolo. 2015. Exploring diachronic universals of agreement: Alignment patterns and zero marking across person categories. In Jürg Fleischer, Elisabeth Rieken & Paul Widmer (eds.). Agreement from a diachronic perspective, 29–51. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110399967-003Search in Google Scholar

Blythe, Richard A. & William Croft. 2012. S-curves and the mechanisms of propagation in language change. Language 88(2). 269–304. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2012.0027.Search in Google Scholar

Bock, Kathryn. 1986. Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology 18(3). 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(86)90004-6.Search in Google Scholar

Bock, K., G. Dell, F. Chang & K. Onishi. 2007. Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition 104(3). 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

Branigan, Holly P., Martin J. Pickering, Jamie Pearson, Janet F. McLean & Ash Brown. 2011. The role of beliefs in lexical alignment: Evidence from dialogs with humans and computers. Cognition 121(1). 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

Brochhagen, Thomas, Gemma Boleda, Eleonora Gualdoni & Yang Xu. 2023. From language development to language evolution: A unified view of human lexical creativity. Science 381(6656). 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ade7981.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Penelope, Mark A. Sicoli & Olivier Le Guen. 2021. Cross-speaker repetition and epistemic stance in Tzeltal, Yucatec, and Zapotec conversations. Journal of Pragmatics 183. 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.07.005.Search in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan & Sandra Thompson. 1997. Three frequency effects in syntax. In L. MatthewJuge & Jeri L. Moxley (eds.), Proceedings of the twenty-third annual Meeting of the berkeley linguistics society: General Session and Parasession on Pragmatics and grammatical structure, 378–388. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.10.3765/bls.v23i1.1293Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Franklin. 2008. Implicit learning as a mechanism of language change. Theoretical Linguistics 34(2). 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1515/THLI.2008.009.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Franklin, Gary S. Dell, Kathryn Bock & Zenzi M. Griffin. 2000. Structural priming as implicit learning: A comparison of models of sentence production. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 29(2). 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005101313330.10.1023/A:1005101313330Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Franklin, Gary S. Dell & Kathryn Bock. 2006. Becoming syntactic. Psychological Review 113(2). 234–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.2.234.Search in Google Scholar

Chia, Katherine & Michael P. Kaschak. 2022. Structural priming in question-answer dialogues. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 29(1). 262–267. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01976-z.Search in Google Scholar

Cleland, Alexandra A. & Martin J. Pickering. 2003. The use of lexical and syntactic information in language production: Evidence from the priming of noun-phrase structure. Journal of Memory and Language 49(2). 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-596x(03)00060-3.Search in Google Scholar

De Vylder, Bart & Karl Tuyls. 2006. How to reach linguistic consensus: A proof of convergence for the naming game. Journal of Theoretical Biology 242(4). 818–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.05.024.Search in Google Scholar

Dekker, Peter, Sonja Gipper & Bart de Boer. 2024. 3SG is the most conservative subject marker across languages: An exploratory study of rate of change. In J. Nölle, L. Raviv, K. E. Graham, S. Hartmann, Y. Jadoul, M. Josserand, T. Matzinger, K. Mudd, M. Pleyer, A. Slonimska, S. Wacewicz & S. Watson (eds.), The Evolution of language: Proceedings of the 15th international conference (Evolang XV). Nijmegen: Evolution of Language Conferences.Search in Google Scholar

Dideriksen, Christina, Morten H. Christiansen, Mark Dingemanse, Malte Højmark-Bertelsen, Christer Johansson, Kristian Tylén & Riccardo Fusaroli. 2023. Language-specific constraints on conversation: Evidence from Danish and Norwegian. Cognitive Science 47(11). e13387. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13387.Search in Google Scholar

Diessel, Holger. 2007. Frequency effects in language acquisition, language use, and diachronic change. New Ideas in Psychology 25(2). 108–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2007.02.002.Search in Google Scholar

Dingemanse, Mark, Andreas Liesenfeld, Marlou Rasenberg, Saul Albert, Felix K. Ameka, Abeba Birhane, Dimitris Bolis, Justine Cassell, Rebecca Clift, Elena Cuffari, Hanne De Jaegher, Catarina Dutilh Novaes, N. J. Enfield, Riccardo Fusaroli, Eleni Gregoromichelaki, Edwin Hutchins, Ivana Konvalinka, Damian Milton, Joanna Rączaszek-Leonardi, Vasudevi Reddy, Federico Rossano, David Schlangen, Johanna Seibt, Elizabeth Stokoe, Lucy Suchman, Cordula Vesper, Thalia Wheatley & Martina Wiltschko. 2023. Beyond single-mindedness: A figure-ground reversal for the cognitive sciences. Cognitive Science 47(1). e13230. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.13230.Search in Google Scholar

Enfield, N. J. 2014. Natural causes of language: Frames, biases, and cultural transmission. Berlin: Language Science Press.10.26530/OAPEN_533873Search in Google Scholar

Enfield, N. J., Tanya Stivers, Penelope Brown, Christina Englert, Katariina Harjunpää, Makoto Hayashi, Trine Heinemann, Gertie Hoymann, Tiina Keisanen, Mirka Rauniomaa, Chase Wesley Raymond, Federico Rossano, Kyung-Eun Yoon, Inge Zwitserlood & Stephen C. Levinson. 2019. Polar answers. Journal of Linguistics 55(2). 277–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226718000336.Search in Google Scholar

Gipper, Sonja. 2020. Repeating responses as a conversational affordance for linguistic transmission: Evidence from Yurakaré conversations. Studies in Language 44(2). 281–326. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.19041.gip.Search in Google Scholar

Greenhill, Simon J. 2023. A shared foundation of language change. Science 381(6656). 374–375. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adj2154.Search in Google Scholar

Gries, Stefan Th. 2005. Syntactic priming: A corpus-based approach. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 34(4). 365–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-005-6139-3.Search in Google Scholar

Harrington, Jonathan & Florian Schiel. 2017./u/-fronting and agent-based modeling: The relationship between the origin and spread of sound change. Language 93(2). 414–445. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2017.0019.Search in Google Scholar

Hartsuiker, Robert J., Sarah Bernolet, Sofie Schoonbaert, Sara Speybroeck & Dieter Vanderelst. 2008. Syntactic priming persists while the lexical boost decays: Evidence from written and spoken dialogue. Journal of Memory and Language 58(2). 214–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

Hill, Eugen. 2022. Conversational priming through repeating responses as a factor in inflectional change. In Chiara Gianollo, Łukasz Jędrzejowski & Sofiana I. Lindemann (eds.), Paths through meaning and form: Festschrift offered to Klaus von Heusinger on the occasion of his 60th birthday, 101–105. Cologne: University of Cologne USB Monographs.Search in Google Scholar

Hinskens, Frans. 2011. Lexicon, phonology and phonetics. Or: Rule-based and usage-based approaches to phonological variation. In Peter Siemund (ed.), Linguistic universals and language variation, 425–466. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110238068.425Search in Google Scholar

Hoekstra, Eric & Arjen P. Versloot. 2019. Factors promoting the retention of irregularity: On the interplay of salience, absolute frequency and proportional frequency in West Frisian plural morphology. Morphology 29(1). 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-018-9334-2.Search in Google Scholar

Hoekstra, Heleen, Michael Moortgat, Ineke Schuurman & Ton Van Der Wouden. 2001. Syntactic annotation for the spoken Dutch corpus project (CGN). In Walter Daelemans, Khalil Sima’an, Jorn Veenstra & Jakub Zavrel (eds.), Computational linguistics in The Netherlands 2000, 73–87. Amsterdam: Brill Rodopi.10.1163/9789004333901_006Search in Google Scholar

Holmberg, Anders. 2016. The syntax of yes and no. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198701859.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Hruschka, Daniel J., Morten H. Christiansen, Richard A. Blythe, William Croft, Paul Heggarty, Salikoko S. Mufwene, Janet B. Pierrehumbert & Shana Poplack. 2009. Building social cognitive models of language change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13(11). 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.08.008.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, Cassandra L., Sun-Joo Cho & Duane G. Watson. 2019. Self-priming in production: Evidence for a hybrid model of syntactic priming. Cognitive Science 43(7). e12749. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12749.Search in Google Scholar

Jaeger, T. Florian & Neal E. Snider. 2013. Alignment as a consequence of expectation adaptation: Syntactic priming is affected by the prime’s prediction error given both prior and recent experience. Cognition 127(1). 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.10.013.Search in Google Scholar

Jäger, Gerhard & Anette Rosenbach. 2008. Priming and unidirectional language change. Theoretical Linguistics 34(2). 85–113. https://doi.org/10.1515/THLI.2008.008.Search in Google Scholar

Kaschak, Michael P., Timothy J. Kutta & Christopher Schatschneider. 2011. Long-term cumulative structural priming persists for (at least) one week. Memory & Cognition 39(3). 381–388. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-010-0042-3.Search in Google Scholar

Kaschak, Michael P., Timothy J. Kutta & Jacqueline M. Coyle. 2014. Long and short term cumulative structural priming effects. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 29(6). 728–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/01690965.2011.641387.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Christina S. & Gloria Chamorro. 2021. Nativeness, social distance and structural convergence in dialogue. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 36(8). 984–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2021.1916544.Search in Google Scholar

Kootstra, Gerrit Jan & Hülya Şahin. 2018. Crosslinguistic structural priming as a mechanism of contact-induced language change: Evidence from Papiamento-Dutch bilinguals in Aruba and The Netherlands. Language 94(4). 902–930. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2018.0050. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/24/article/711823.Search in Google Scholar

Leech, Geoffrey, Paul Rayson & Andrew Wilson. 2001. Word frequencies in written and spoken English: Based on the British National corpus. Harlow: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Levelt, Willem J. M. & Stephanie Kelter. 1982. Surface form and memory in question answering. Cognitive Psychology 14(1). 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(82)90005-6.Search in Google Scholar

Loebell, Helga & Kathryn Bock. 2003. Structural priming across languages. Linguistics 41(5). 791–824. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.2003.026.Search in Google Scholar

Mahowald, Kyle, Ariel James, Richard Futrell & Edward Gibson. 2016. A meta-analysis of syntactic priming in language production. Journal of Memory and Language 91. 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2016.03.009.Search in Google Scholar

Motamedi, Yasamin, Marieke Schouwstra, Kenny Smith, Jennifer Culbertson & Simon Kirby. 2019. Evolving artificial sign languages in the lab: From improvised gesture to systematic sign. Cognition 192(103964). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2019.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Nilsson, Jenny. 2015. Dialect accommodation in interaction: Explaining dialect change and stability. Language & Communication 41. 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2014.10.008.Search in Google Scholar

Oostdijk, Nelleke. 2000. The spoken Dutch corpus: Overview and first evaluation. In Maria Gavrilidou, George Carayannis, Stella Markantonatou, Stelios Piperidis & Gregory Stainhauer (eds.), Proceedings of the second international Conference on language Resources and evaluation (LREC’00). Athens: European Language Resources Association. https://aclanthology.org/L00-1083/.Search in Google Scholar

Pickering, Martin J. & Simon Garrod. 2004. Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27(2). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X04000056.Search in Google Scholar

Pickering, Martin J. & Simon Garrod. 2017. Priming and language change. In Marianne Hundt, Sandra Mollin & Simone E. Pfenninger (eds.), The changing English language, 173–190. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316091746.008Search in Google Scholar

Pleyer, Michael. 2023. The role of interactional and cognitive mechanisms in the evolution of (proto)language(s). Lingua 282. 103458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2022.103458.Search in Google Scholar

Rasenberg, Marlou, Asli Özyürek & Mark Dingemanse. 2020. Alignment in multimodal interaction: An integrative framework. Cognitive Science 44(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12911.Search in Google Scholar

Rasilo, Heikki & Okko Johannes Räsänen. 2015. Computational evidence for effects of memory decay, familiarity preference and mutual exclusivity in cross-situational learning. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 37. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9pv6j7t5 (accessed 3 October 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Raymond, Geoffrey. 2003. Grammar and social organization: Yes/no interrogatives and the structure of responding. American Sociological Review 68(6). 939. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519752.Search in Google Scholar

Reali, Florencia & Thomas L. Griffiths. 2009. The evolution of frequency distributions: Relating regularization to inductive biases through iterated learning. Cognition 111(3). 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2009.02.012.Search in Google Scholar

Reali, Florencia, Nick Chater & Morten H. Christiansen. 2018. Simpler grammar, larger vocabulary: How population size affects language. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285(1871). 20172586. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2586.Search in Google Scholar

Rogers, Everett. 1995. Diffusion of innovations, 4th edn. New York: The Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rozwadowski, Jan. 1995. Litewska gwara okolic Zdzięcioła na Nowogródczyźnie, Dzieło pośmiertne, opracowanie Adam Gregorski [Lithuanian dialect from the area around Dziatło in Nowogródek region; posthumous work, edited by Adam Gregorski]. Kraków: Polska Akademia Nauk.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996. Confirming allusions: Toward an empirical account of action. American Journal of Sociology 102(1). 161–216. https://doi.org/10.1086/230911. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2782190.Search in Google Scholar

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2006. Interaction: The infrastructure for social institutions, the natural ecological niche for language, and the arena in which culture is enacted. In N. J. Enfield & Stephen C. Levinson (eds.), Roots of human sociality: Culture, cognition, and human interaction, 70–96. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003135517-4Search in Google Scholar

Scheibman, Joanne. 2001. Local patterns of subjectivity in person and verb type in American English conversation. In Joan L. Bybee & Paul J. Hopper (eds.), Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure (Typological Studies in Language 45), 61–89. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.45.04schSearch in Google Scholar

Seržant, Ilja A. & George Moroz. 2022. Universal attractors in language evolution provide evidence for the kinds of efficiency pressures involved. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9(1). 58. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01072-0.Search in Google Scholar

Siewierska, Anna. 2013. Verbal person marking. In S. MatthewDryer & Martin Haspelmath (eds.), The world atlas of language structures online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info/chapter/102.Search in Google Scholar

Sims-Williams, Helen. 2016. Analogy in morphological change. Oxford: University of Oxford PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Sims-Williams, Helen. 2022. Token frequency as a determinant of morphological change. Journal of Linguistics 58(3). 571–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226721000438.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, Andrew D. M. 2014. Models of language evolution and change. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 5(3). 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1285.Search in Google Scholar

Steels, Luc. 1998. Synthesising the origins of language and meaning using co-evolution, self-organisation and level formation. In James R. Hurford, Michael Studdert-Kennedy & Chris Knight (eds.), Approaches to the evolution of language, 384–404. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Travis, Catherine E., Rena Torres Cacoullos & Evan Kidd. 2017. Cross-language priming: A view from bilingual speech. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20(2). 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728915000127.Search in Google Scholar

Trudgill, Peter. 1986. Dialects in contact. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Trudgill, Peter. 2004. New-dialect formation: The inevitability of colonial Englishes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

van Gijn, Rik. 2006. A grammar of Yurakaré. Nijmegen: Radboud Universiteit PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

van Gijn, Rik, Vincent Hirtzel, Sonja Gipper & Jeremías Ballivián Torrico. 2011. The Yurakaré archive. Online language documentation, DoBeS archive, the language archive, MPI for psycholinguistics, Nijmegen. https://hdl.handle.net/1839/8df587ed-3d6e-4db8-bfe5-4ecad5cef3a2.Search in Google Scholar

van Trijp, Remi. 2016. The evolution of case grammar. Berlin: Language Science Press.10.26530/OAPEN_611694Search in Google Scholar

Versloot, Arjen P. & Elżbieta Adamczyk. 2018. Plural inflection in North Sea Germanic languages: A multivariate analysis of morphological variation. In Antje Dammel, Matthias Eitelmann & Mirjam Schmuck (eds.) Studies in language companion series, Vol. 203, 17–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.203.02ver.Search in Google Scholar

Vidugiris, Aloyzas. 2014. Lazūny šnekta [Lazūnai subdialect]. Vilnius: Lietuvių Kalbos Institutas.Search in Google Scholar

Watkins, Calvert. 1962. Indo-European origins of the Celtic verb, vol. 1, The sigmatic aorist. Dublin: Institute for Advanced Studies.Search in Google Scholar

Wilcox, Ethan Gotlieb, Tiago Pimentel, Clara Meister, Ryan Cotterell & Roger P. Levy. 2023. Testing the predictions of surprisal theory in 11 languages. ArXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.03667.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2023-0187).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese