Abstract

This paper explores how linguistic data annotation can be made (semi-)automatic by means of machine learning. More specifically, we focus on the use of “contextualized word embeddings” (i.e. vectorized representations of the meaning of word tokens based on the sentential context in which they appear) extracted by large language models (LLMs). In three example case studies, we assess how the contextualized embeddings generated by LLMs can be combined with different machine learning approaches to serve as a flexible, adaptable semi-automated data annotation tool for corpus linguists. Subsequently, to evaluate which approach is most reliable across the different case studies, we use a Bayesian framework for model comparison, which estimates the probability that the performance of a given classification approach is stronger than that of an alternative approach. Our results indicate that combining contextualized word embeddings with metric fine-tuning yield highly accurate automatic annotations.

1 Introduction

In corpus linguistics, the collection and annotation of data commonly involves a relatively balanced combination of computer-aided and manual labour. It is still common practice, for instance, to first retrieve data representing a particular linguistic phenomenon from an electronic corpus (e.g. by means of a concordancer tool or query script) and subsequently manually categorize the collected examples into different functional-semantic groups (e.g. animate/inanimate; literal/figurative; agent/patient/instrument/ …). However, as the range of research questions that linguists aim to address by means of corpus data has expanded both in diversity and complexity, and as researchers have started to resort to more complex (often multivariate) statistical analysis to address these questions, it may no longer be practically feasible to continue working this way. Given how labour-intensive manual data annotation is, it is difficult to meet the growing need to annotate larger samples for robust statistical research. As such, it has become an important practical challenge in corpus linguistics to determine how data annotation practices can evolve along with the needs of researchers (e.g. Hundt et al. 2019).

This paper contributes to tackling this challenge by exploring how corpus data annotation can be made (semi-)automatic by means of machine learning. More specifically, we home in on the use of “contextualized word embeddings” (i.e. vectorized representations of the meaning of word tokens based on the sentential context in which they appear) extracted by large language models (LLMs; i.e. machine learning architectures with a large number of adjustable parameters, which are designed to exploit large amounts of pre-training text data). In natural language processing (NLP), contextualized word embeddings generated with LLMs are often shown to perform impressively at “downstream tasks”, like part-of-speech tagging, dependency parsing, or named-entity recognition (e.g. Brandsen et al. 2022; Dozat and Manning 2017; Kulick and Ryant 2020; Wang et al. 2021).[1] Yet, in (corpus) linguistics, contextualized word embeddings have so far remained largely unused,[2] despite the fact that the contextualized embeddings resulting from them display high information content and produce strong predictive models.[3]

We will present three example case studies (representing data annotation scenarios in corpus linguistics) to highlight how LLMs can be employed to annotate corpus data. Focusing on historical corpus data, we will use two LLMs: MacBERTh (pre-trained on historical English; 1500–1950), and GysBERT (pre-trained on historical Dutch; 1500–1950). Subsequently, we assess how the contextualized embeddings generated by these models can be combined with different machine learning approaches to data classification, and evaluate how these approaches compare across the different case studies. To this end, we use a Bayesian framework for model comparison, which estimates the probability that the performance of a given classification approach is stronger than that of an alternative approach. In the conclusion, we discuss the merits and downsides of the different approaches to (semi-)automatic data annotation, and briefly reflect on whether these approaches could be “what’s next” for corpus linguistics.

2 Methods

The method we assess in this paper takes as its starting position that researchers already have access to pre-annotated (e.g. part-of-speech tagged, and to a lesser extent semantically annotated) corpora and a range of (semi-)automatic annotation tools (e.g. Archer et al. 2004, 2003; Koller et al. 2008; Marcus et al. 1993; Piao et al. 2005; Rayson and Garside 1998). Yet, we may still find ourselves in situations where the available resources do not suffice. For certain languages and language varieties (particularly historical ones), for instance, high-quality tagged corpora are quite rare and limited in size, and the corpora and general tools that have been developed for semantic annotation so far often apply a pre-defined, non-adjustable tag set. It is possible, then, that the pre-defined tag set does not make the semantic distinctions needed to address certain research question(s), or that the tag set cannot be applied to the particular dataset the researcher wishes to study (e.g. because the data involves specialized vocabulary; see the issues addressed in Archer et al. 2004; Prentice 2010). With end-to-end machine learning approaches, however, it is possible to develop a semi-automatic data annotation procedure where researchers provide their own custom data annotation or categorization scheme.

This customizable procedure will be demonstrated in three case studies.[4] The first two are cases where the data annotation involves word sense disambiguation (WSD), with one constituting a more general, coarse-grained classification system into literal and figurative senses (of several lexemes relating to the semantic domain of fire) and the other constituting a more fine-grained classification system (of the scientific terms mass and weight). The third case study involves semantic role labelling (of scent-related terms). For each case study, a manually annotated dataset of historical corpus data is provided that will serve as input or “training” data. Subsequently, we used either MacBERTh (Manjavacas and Fonteyn 2021, 2022a) or GysBERT (Manjavacas and Fonteyn 2022b) to extract contextualized embeddings for the targeted part of the training data.[5]

Both models were created to facilitate the use of state-of-the-art NLP methods in humanities research, where researchers often work with historical corpora. When it comes to historical text, the use of language models that have been set-up to process only present-day language varieties may be less than ideal: not only may the models fail to reach optimal performance due to the lexical and orthographic differences between language varieties from different time stages, they may also impose an “anachronistic”, present-day bias onto the textual material (see, e.g., the discussions in Fonteyn 2020b; Hengchen et al. 2021). As such, it has been argued that, before processing historical text, LLMs should ideally at least be adapted to or even fully pre-trained on historical text.[6] MacBERTh and GysBERT have been pre-trained on historical text spanning from approximately 1500–1950. At least for a number of downstream tasks, including part-of-speech tagging in historical text, these models have been shown to outperform present-day language models, as well as present-day models adapted to historical text (Manjavacas and Fonteyn 2022a, 2022b).[7] In the case studies presented in this paper, the “targeted part” of the training data constitutes individual words, but it is in principle also possible to extract embeddings for word groups and phrases (e.g. S. Wang et al. 2021). Subsequently, the extracted embeddings are used as input for an automated classification algorithm that could be applied to annotate “unseen” (i.e. unannotated) data. For each case study, we examine different types of classification algorithms, which are subsequently systematically compared and evaluated through statistical model comparison.

2.1 Classification

We implemented four different classification approaches belonging to two broad types. In the first type, we solely extracted the contextualized embeddings of the target words, and used them as the only features for training traditional off-the-shelf classification algorithms. In particular, we resorted to the k-nearest neighbour (KNN) and the support vector machine (SVM) algorithms, as implemented by the scikit-learn software package. With KNN, the model’s prediction of which category an unseen test item belongs to is decided based on its k nearest neighbours in the training set. Here, neighbourhoods are determined by the distance between the embeddings of unseen test items and training test items. The SVM algorithm, by contrast, uses the training data to infer a plane in the space spanned by the input features (i.e. the input word embeddings) that maximally separates the instances according to their class. In the case of a binary classification problem, the fitted plane divides the space in two regions such that a test item is assigned a label considering on which side of the plane its feature representation lays.

In the second type of approach, we use the original pre-trained LLM (i.e. MacBERTh or GysBERT), and fine-tune its parameters in order to perform the classification task at hand. We apply two kinds of fine-tuning. The first one is a common parametric fine-tuning procedure that incorporates additional parameters which are tuned in order to produce a probability distribution over the categories to which an example should be assigned. We will refer to this method simply as “fine-tuning” and rely on the implementation of the transformers software package (Wolf et al. 2020). The second fine-tuning approach is a “non-parametric” or “metric” one, which has the goal of shifting the embeddings of words in the same class closer to each other and further away from the words in different classes. This final approach will be referred to as “metric fine-tuning”.[8]

2.2 Evaluation

We evaluate all four approaches using a ten-fold cross validation (CV) procedure. We divide the available data into ten non-overlapping sections or “splits”, and test the performance of each classification approach on each of these splits. As training material for the classification algorithms, we rely on the splits that are not used for testing at each iteration. Because CV is an iterative evaluation procedure, it not only yields a more statistically solid comparison between the different classification approaches, but also enables us to assess the variance in the performance of each model (i.e. fluctuations in performance due to differences in the training and test data). Finally, we show that cross-validated results also allow us to employ a powerful model comparison method that helps us determine which methods are worth deploying in future automatic annotation settings.

3 Word sense disambiguation

While LLMs that generate contextualized embeddings, such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers; Devlin et al. (2019)) can be used for a range of different tasks, they have proven particularly useful for word sense disambiguation (WSD) (Hadiwinoto et al. 2019; Reif et al. 2019; Wiedemann et al. 2019).[9] In corpus linguistics, there are numerous examples of studies where addressing a specific research question involves some form of WSD. Corpus-based grammaticalization and constructionalization studies, for instance, often (manually) categorize queried examples into various usage types (e.g. source meaning, bridging contexts, etc.; see, among many others, Brinton 2017; Mukherjee and Huber 2012; Rissanen 2004). Furthermore, studies like, for instance, De Smet’s (2016) on the relation between word frequency, entrenchment, and word polysemy involve searching a corpus for a particular linguistic item and subsequently distinguishing particular senses (e.g. “literal” uses of the word tsunami, as in The coastal town was destroyed by the Indian Ocean Tsunami, vs. figurative uses, as in We were overwhelmed by the tsunami of replies). In recent years, the question whether distributional semantic models that generate contextualized word vectors can be used to automate this part of the annotation procedure has become a point of interest for corpus linguists (e.g. De Pascale 2019; Fonteyn 2020a; Heylen et al. 2015; Hilpert and Flach 2020; Hilpert and Saavedra 2020).

3.1 Fire metaphors

To demonstrate how LLMs may be employed to at least partially automate the annotation of data in terms of word sense categories, we first focus on the use of a set of lemmata related to the conceptual domain of fire: fire, flame, ardent, blaze, and burn. A popular lexical domain for metaphorical extension (Charteris-Black 2016), words related to fire will not only frequently occur in their literal sense, but also in figurative uses (e.g. to describe positive as well as negative emotions). In line with the tsunami case study in De Smet (2016), then, a possible research question could be whether particular events that cause an increase in the usage frequency of fire words in their literal sense also trigger a change in the frequency (and perhaps also the nature) of figurative uses.

As a toy example, one could test the hypothesis that the Great Fire of London (1666) triggered a frequency-driven change in the semantic structure of fire words. For our purposes, we will test whether the data annotation for such a study could be done semi-automatically. To this end, a random sample of 300 instances per lemma was extracted from the EMMA corpus, which contains texts written by 50 prominent authors born in the seventeenth century who mostly belonged to the London-based elite (Petré et al. 2019). All examples were then manually annotated following the annotation scheme outlined in examples (1) and (2):[10] for all instances in the dataset, word embeddings were extracted by means of the historical English model MacBERTh.

| LIT: The target word has a literal, fire-related meaning. | |

| a. | Hereticks had fet the Church on fire (1683, EMMA) |

| b. | it usually utters smoak by day, but by night, Flames ; (1683, EMMA) |

| c. | the Garrison Apprehending a Siege, burnt their Suburbs (1693, EMMA) |

| d. | it surprizes the Spectators, to see Jugglers, put ardent Coals into their Mouths (1702, EMMA) |

| e. | Burn all my Books, and let my Study Blaze , Burn all to Ashes (1687, EMMA) |

| MET: The target word has a figurative meaning. The semantic domain of fire is metaphorically extended to other domains, including emotion, sensation, desire, and information. | |

| a. | Thou hast no Rage, no Fire , no Spirit or Power (1688, EMMA) |

| b. | Waters can’t quench Love’s flames nor Floods The same can ever drown (1692, EMMA) |

| c. | There are those whose ears wou’d burn at such reports (1700, EMMA) |

| d. | … make mention of you in our prayers, and our ardent and constant cries to the God of all Grace (1698, EMMA) |

| e. | … the lofty Praise Of Martial Verse and Deeds that Hero’s blaze (1687, EMMA) |

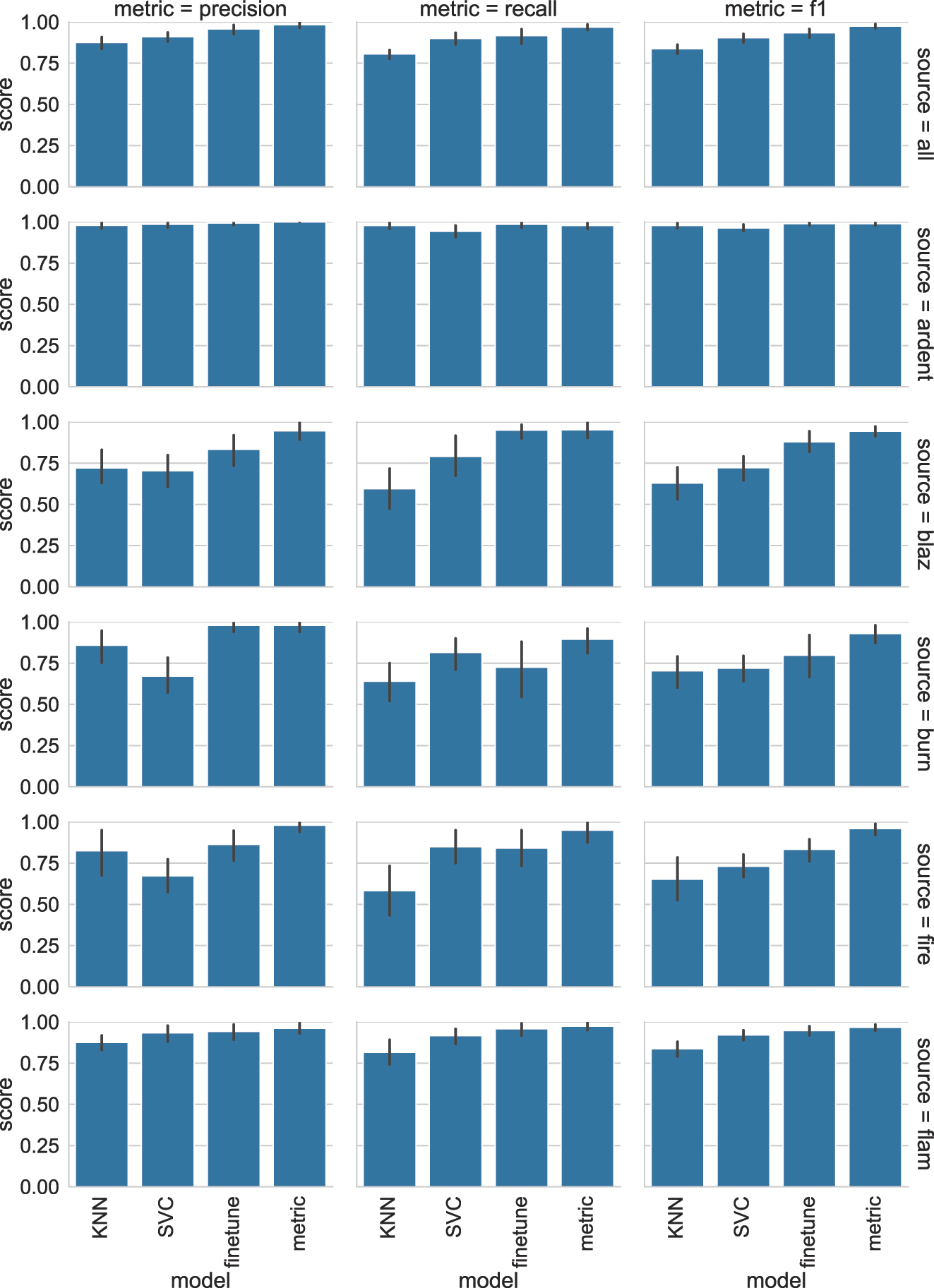

Table 1 lists the mean and standard deviation for the precision, recall, and f1 scores resulting from the ten-fold CV for each classification approach.[11] The precision score gives a ratio of how many items that were assigned to a particular category were indeed correctly assigned to it, whereas the recall score can be read as a measure of how many items that should have been given a certain label were indeed given that label. The f1 score is a measure of classification accuracy retrieved by calculating the harmonic mean of the precision and recall, with higher scores indicating a better classification accuracy. Additionally, the robustness of each approach can be assessed by examining the standard deviation reported in Table 1. A smaller value indicates that a model is less affected by subtle variations across the different training sets used in each of the 10 trials. Results are reported for each individual lemma, as well as for a test round in which all lemmas were grouped into one dataset (labelled “all” in Table 1).

Results for the individual fire metaphors classification tasks.

| Source | Model | Precision | Recall | F1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| All | KNN | 87.6 | 6.2 | 80.5 | 4.6 | 83.8 | 4.6 |

| SVM | 91.1 | 4.7 | 90.0 | 6.0 | 90.4 | 4.3 | |

| Finetune | 95.8 | 4.7 | 91.7 | 8.2 | 93.4 | 4.5 | |

| Metric | 98.3 | 3.0 | 96.8 | 2.8 | 97.5 | 2.2 | |

| Ardent | KNN | 98.0 | 3.2 | 97.9 | 3.4 | 97.9 | 2.5 |

| SVM | 98.7 | 2.8 | 94.4 | 6.4 | 96.3 | 3.5 | |

| Finetune | 99.4 | 2.0 | 98.6 | 2.9 | 99.0 | 1.7 | |

| Metric | 100.0 | 0.0 | 97.9 | 3.4 | 98.9 | 1.7 | |

| Blaze | KNN | 72.1 | 18.3 | 59.5 | 20.3 | 62.9 | 16.2 |

| SVM | 70.4 | 16.8 | 79.0 | 19.9 | 72.3 | 12.8 | |

| Finetune | 83.4 | 16.8 | 95.0 | 8.1 | 88.0 | 11.1 | |

| Metric | 94.6 | 9.1 | 95.2 | 7.7 | 94.4 | 5.1 | |

| Burn | KNN | 85.9 | 16.3 | 64.0 | 20.1 | 70.3 | 16.6 |

| SVM | 67.2 | 16.8 | 81.5 | 17.6 | 71.9 | 13.9 | |

| Finetune | 98.0 | 6.3 | 72.5 | 29.2 | 79.8 | 22.0 | |

| Metric | 98.0 | 6.3 | 89.5 | 14.6 | 93.0 | 9.8 | |

| Fire | KNN | 82.5 | 23.7 | 58.3 | 25.5 | 65.3 | 22.3 |

| SVM | 67.3 | 16.6 | 85.0 | 17.5 | 73.2 | 11.9 | |

| Finetune | 86.4 | 16.0 | 84.2 | 18.2 | 83.4 | 11.5 | |

| Metric | 98.0 | 6.3 | 95.0 | 10.5 | 96.0 | 6.4 | |

| Flame | KNN | 87.6 | 7.8 | 81.7 | 12.9 | 83.8 | 7.5 |

| SVM | 93.4 | 8.4 | 91.7 | 7.9 | 92.1 | 5.3 | |

| Finetune | 94.3 | 8.0 | 95.8 | 5.9 | 94.7 | 4.6 | |

| Metric | 96.2 | 5.2 | 97.5 | 4.0 | 96.7 | 3.2 | |

Comparing the f1 scores of each approach, we find that, while there is some variation between individual lemmas, a few generalizations can be made. The f1 scores are the lowest when the KNN algorithm is used to classify examples. One exception is the lemma ardent, where KNN performs slightly better than SVM. The worst performance of KNN is found with burn and fire, where poor recall results in f1 scores of 70.3 and 65.3 respectively. By contrast, the best results are achieved by metric fine-tuning, which is only equalled once by fine-tuning for ardent. Notably, the f1 scores for metric fine-tuning never drop below 93.0, and the standard deviations reveal that it also has the most stable performance across all trials.

3.2 Mass and weight

So far, then, it appears that using (MacBERTh) embeddings after fine-tuning with an end-to-end metric learning approach could serve as a highly reliable and robust tool for automated word sense classification. We will now show that this approach continues to perform strongly when the data is taken from a corpus of specialized language and is annotated at finer levels of granularity (i.e. with more and subtler sense distinctions). We consider a case study of terminological overlap in scientific language.

In 1687, Isaac Newton first differentiated between the concepts of weight and mass, which were both referred to by means of the word weight before then. To investigate, for instance, how long it took for the scientific community to adjust their usage of the word weight to Newton’s proposal, how Newton’s terminological renewal diffused among the scientific community (e.g. through author networks, through disciplines, etc.), or whether other uses of the words mass and weight were affected by this “conscious effort” to improve scientific terminology, a large-scale specialized corpus of scientific writing such as the Royal Society Corpus (Fischer et al. 2020) can be queried for all instances of mass, masses, weight, and weights. Here, we focus on a randomized sample of 1,500 (out of 56,813) examples, from which 621 were tokens of mass(es) and 879 of weight(s). Subsequently, the data were manually annotated following the detailed six-way classification scheme outlined in examples (3)–(8), which is based on the senses listed for mass and weight in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED Online 2022a, 2022b).[12]

| N: Mass or weight refers to a thing or object. | |

| a. | The mass on the filter was treated with boiling alcohol (Schunck 1853) |

| b. | a flat circular weight nicely turned, and pierced in the direction of its diameter to receive the bar, was slid upon it (Kater 1819) |

| M: Mass or weight refers to mass (i.e. how much matter is within an object). | |

| a. | We are thus led to inquire how the stresses are distributed in the earth’s mass and what are their magnitudes (Darwin 1882) |

| b. | In the third, the weight of the principle bones of a selected number of species (27) is stated (Davy 1865) |

| W: Weight refers to weight (i.e. referring to force, balancing, counterpoises, or the amount of effort required to lift something). | |

| a. | fig. 3 is only 40 feet from the bow, and that the excess of weight over buoyancy on this length is only 45 tons (Reed and Stokes 1871) |

| W/M: Unclear whether the example refers to mass or weight. | |

| a. | The Commissioners for the Restoration of the Standards of weight and measure, in their Report dated December 21, 1841, recommended that … (Miller 1857) |

| COL: Mass or weight refers to a collection of objects. | |

| a. | A glacier is not a mass of fragments (Forbes 1846) |

| MET: Mass or weight is used to indicate the importance of a thing. | |

| a. | The next thought is that I may have assigned too great a mass to the doubt (Pratt 1854) |

| b. | The contact theory has long had possession of men’s minds, is sustained by a great weight of authority (Faraday 1840) |

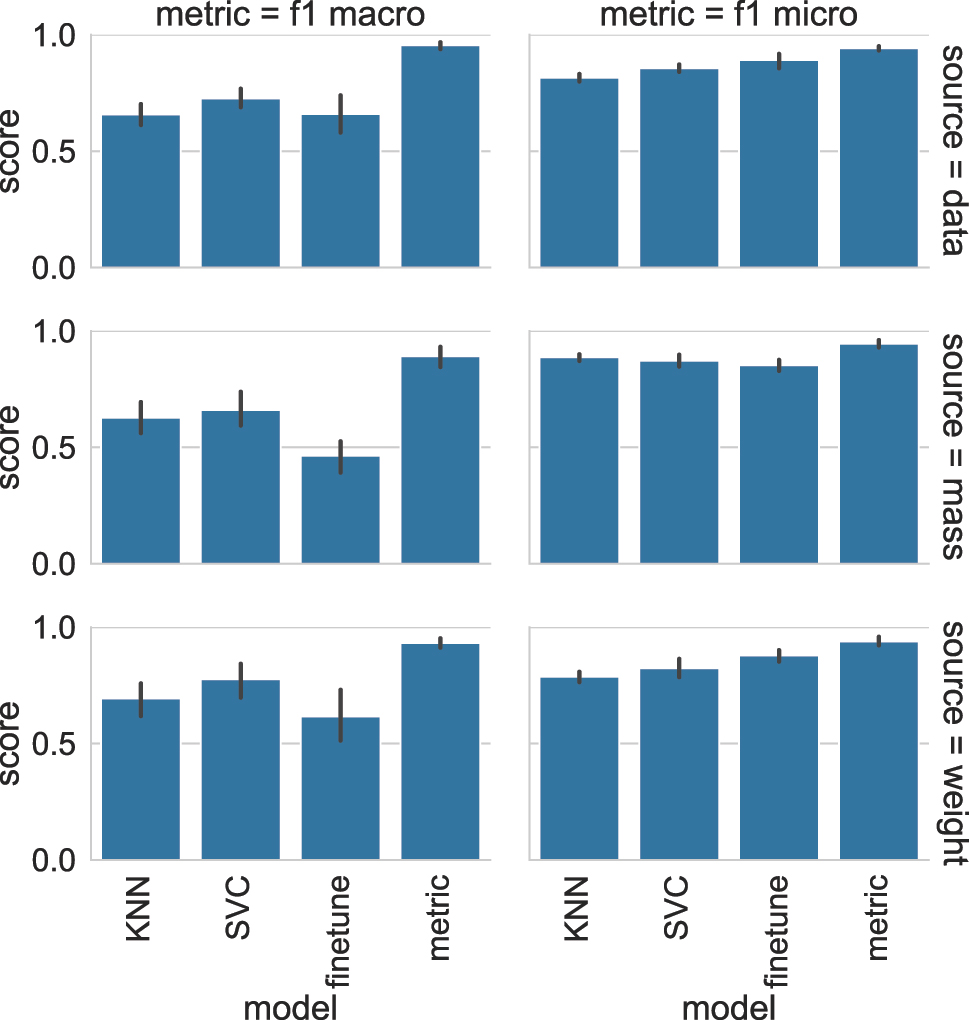

As with the previous case study, we approach the sense disambiguation task per individual lemma, as well as by training and testing with a dataset in which both lemmas are grouped. The results of each classifier approach for the more fine-grained sense disambiguation of mass and weight are presented as f1 scores in Table 2. The classification task at hand involves multiple sense categories with a skewed frequency distribution (e.g. particular categories such as MET, where the terms are metaphorically extended to indicate “importance”, are very infrequent, particularly for mass). As such, the results in Table 2 report both the micro and the macro f1 scores obtained by each approach. The difference between these scores is that in the case of macro f1, each sense category has equal weight: when the macro average of f1 is computed, this is done for each sense class individually after which the average is taken over all classes. With micro f1, by contrast, sense classes are not treated separately, which means that small sense categories, which may be more challenging to label correctly because there are fewer examples of them in the training data, are less important in the calculation of the f1 score.

Results for the mass and weight classification task.

| Source | Model | F1 micro | F1 macro | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| All | KNN | 81.6 | 2.7 | 65.8 | 7.6 |

| SVM | 85.6 | 2.8 | 72.6 | 7.3 | |

| Finetune | 89.2 | 5.3 | 66.0 | 13.9 | |

| Metric | 94.2 | 1.5 | 95.5 | 2.6 | |

| Mass | KNN | 88.7 | 2.4 | 62.7 | 11.5 |

| SVM | 87.2 | 4.6 | 66.0 | 11.6 | |

| Finetune | 85.3 | 4.0 | 46.4 | 10.9 | |

| Metric | 94.5 | 2.8 | 89.2 | 7.7 | |

| Weight | KNN | 78.6 | 3.9 | 69.4 | 12.5 |

| SVM | 82.4 | 6.9 | 77.6 | 12.7 | |

| Finetune | 87.8 | 4.2 | 61.6 | 19.0 | |

| Metric | 93.8 | 3.0 | 93.2 | 3.5 | |

Starting with micro f1 and its accompanying standard deviation, we find relatively high scores for all of the classification tasks for each lemma individually as well as for the grouped set. Yet, as with the previous case study, the most accurate (and most stable) classification approach is metric fine-tuning. This is also evident from the macro f1 scores, where the difference between metric fine-tuning and the second-best approach, which in this case is SVM, is very large. In fact, while macro f1 ranges from 89.2 to 95.5 for metric fine-tuning, none of the other approaches score higher than 77.6. These results indicate that in more fine-grained WSD tasks, where there may be imbalance and a low number of training examples for certain categories, classification algorithms such as KNN, SVM, and “regular” fine-tuning could perform poorly for those categories. This appears to be particularly true for fine-tuning, which noticeably struggles with low-frequency categories (e.g. MET for the lemma mass; f1 = 46.4).

4 Semantic role labelling: SCENT terms as agents, objects, or patients

Beyond WSD, computational studies have also explored the performance of LLMs in semantic role labelling (Klafka and Ettinger 2020; Proietti et al. 2022). This too is relevant for (corpus) linguistic analyses, which can also involve annotating linguistic items according to their semantic role. Research projects in critical discourse analysis and cognitive linguistics, for instance, are often interested in revealing particular patterns of force-dynamic construals within texts to lay bare particular cultural or even ideological dimensions to the semantic roles that have been assigned to the participants described in them (e.g. Hart 2015, 2011; van Leeuwen 1996). Hart (2013), for instance, investigated online press reports of the UK student fees protests in 2010, revealing that (student) protesters were more often presented as agents of an action (e.g. protesters burst through police lines to storm the Conservative party headquarters [The Guardian, 24 November]), whereas the police were more often construed as patients or undergoers of such actions (e.g. A number of police officers were injured after they came under attack from youths [The Telegraph, 10 November]). Besides human participants, the portrayal of concepts or objects in different text types and/or cultures (or within a culture across time) is also considered frequently, and a number of recent projects have started to pursue how computational analyses may help reveal, for instance, how machines (Coll Ardanuy et al. 2020) or olfactory concepts (Massri et al. 2022) were portrayed in historical texts.

Our case study, which continues in the theme of olfaction – that is, “the sense through which smells (or odors) are processed and experienced” (Massri et al. 2022) – considers the semantic roles assigned to scent-related terms in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch texts. More specifically, we collected 1,000 examples of two terms, 500 of geur (‘scent’) and 500 of reuk (‘smell’), from the Early Dutch Books Online (1781–1800; EDBO) from the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century section of the Digital Library for Dutch Literature (DBNL). To each example, a semantic role label was manually assigned specifying whether the term geur or reuk functioned as an agent, object, or patient. Each semantic role label is described and exemplified in (9)–(11).[13] As the dataset involves Dutch examples, embeddings were extracted by means of the Dutch historical model GysBERT.

| A: The scent term reuk or geur is presented as the agent of an action. This action is done to or experienced by a person. | |

| a. | Den geur van u schepsel heeft oock bedroghen mijnen reuck (1629, DBNL) |

| ‘The scent of your creature has also misled my sense of smell’ | |

| b. | Want gelijck een lieflicke reuk den mensche seer vermaeckt, … (1637, DBNL) |

| ‘Because like a gentle smell pleases the people, …’ | |

| c. | en hoe lieflijk wierd ik door haaren reuk verkwikt! (1794, EDBO) |

| ‘and how gently was I by her smell invigorated!’ |

| O: The scent term reuk or geur is presented as an object given by a thing (to a person). | |

| a. | het geeft Een lieffelyke reuk die iets verkwiklyke heeft (1790, EDBO) |

| ‘it gives a lovely smell that has something invigorating’ | |

| b. | Blaas, lentewind blaas uw geur Door bosschen beemden, hoven (1790, EDBO) |

| ‘Blow, spring wind blow your scent through forests, fields, yards’ | |

| c. | Die ’t oog met kleur vermaakt, en ’t hert met geur bewaassemt (1673, DBNL) |

| ‘That pleases the eye with colour, and fogs the heart with scent’ |

| P: The scent term reuk or geur is presented as the patient or undergoer of an action (done by a person). | |

| a. | de Heere rook dien lieffelyke reuk (1782, EDBO) |

| ‘the lord smelled that lovely smell’ | |

| b. | De wandelaar juicht haar toe, daar hy haar geur geniet (1785, EDBO) |

| ‘The hiker cheers her on, as he enjoys her smell’ | |

| c. | Nochtans verneem ik geenen viesen reuk (1691, DBNL) |

| ‘Although I perceive no foul smell’ |

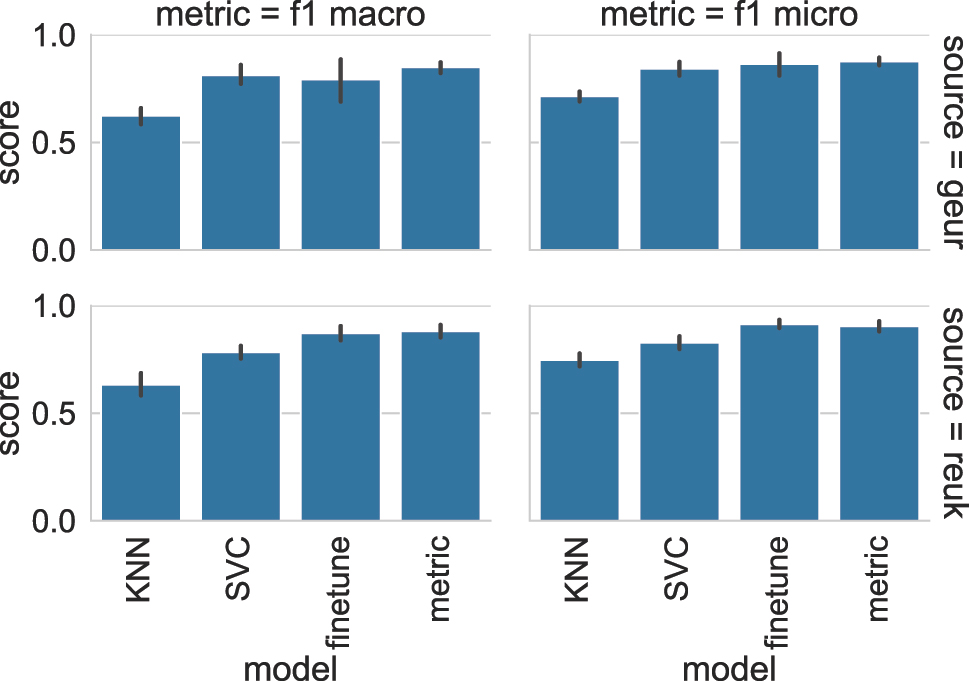

Table 3 again shows the f1 score (macro and micro) achieved by each classification approach for each lemma. As with both WSD case studies described in Section 3, it is the KNN classification algorithm that yields the poorest results across the board. The other approaches are more comparable in terms of both macro and micro f1, with metric fine-tuning achieving the highest scores and lowest standard deviation in the ten-fold CV procedure.

Results for the scent classification task.

| Source | Model | F1 micro | F1 macro | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Geur | KNN | 71.4 | 4.0 | 62.3 | 6.6 |

| SVM | 84.2 | 5.8 | 81.2 | 7.6 | |

| Finetune | 86.4 | 8.7 | 79.3 | 17.0 | |

| Metric | 87.6 | 3.1 | 84.9 | 4.3 | |

| Reuk | KNN | 74.8 | 5.2 | 63.2 | 8.7 |

| SVM | 82.8 | 5.2 | 78.4 | 5.2 | |

| Finetune | 91.4 | 3.3 | 87.2 | 5.8 | |

| Metric | 90.4 | 4.3 | 88.1 | 5.2 | |

5 Model comparison

In this section, we summarize the evidence gathered across the case studies, and show which classification method is expected to give strongest results in similar semi-automatic annotation setups. To this end, we use a Bayesian model comparison method as presented in Kruschke (2013).[14] As discussed in Benavoli et al. (2017), there are several advantages to Bayesian model comparison over the more commonly used frequentist alternatives, which use null-hypothesis testing. These include that Bayesian model comparison helps overcome a problem that occurs with frequentist methods, where the estimated effect size of the observed differences between models is entangled with the underlying sample size.

The chosen Bayesian comparison method jointly analyses the cross-validated results obtained by different classification approaches across multiple datasets. That is, as input we use the classification accuracy – that is, the proportion of correctly annotated items – of each classification approach (i.e. KNN, SVM, fine-tuning, and metric fine-tuning) obtained in each of the folds for each of the three outlined case studies. The output of the comparison method consists of the estimated probability that a particular classification approach performs differently from or similarly to one of the others.

The results of the comparison are presented in Table 4. For each pair of compared classification approaches (e.g. KNN vs. Finetune; KNN vs. VSM; etc.), the following information is provided. First, we show the so-called region of practical equivalence (ROPE) to interpret the results (Kruschke 2013). The idea behind the ROPE is to define a “performance difference margin” within which two models can be considered to offer similar performance. In line with szymanskibestbetterbayesian2020, we compare the classification methods across three different ROPE margins (0.01, 0.025, and 0.05). Then, we list the results of the Bayesian comparison method, which should be read as a probability of the following events: (i) the model listed on the left has better performance (“Left”), (ii) the two models fall within the considered ROPE (“Equal”), and (iii) the model listed on the right has stronger performance (“Right”).

Bayesian model comparison over cross-validated results for the different tasks.

| ROPE | Left | Equal | Right | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | Finetune | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.99 |

| 0.025 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.99 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.11 | 0.89 | ||

| SVM | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.0 | 0.97 | |

| 0.025 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.79 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.86 | 0.14 | ||

| Metric | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.99 | |

| 0.025 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.99 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.99 | ||

| Finetune | SVM | 0.01 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 0.025 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.01 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.0 | ||

| Metric | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | |

| 0.025 | 0.0 | 0.19 | 0.81 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.91 | 0.09 | ||

| SVM | Metric | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.025 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

Several conclusions can be drawn from Table 4. First, KNN is highlighted as the least competitive approach, being inferior to the other approaches with very high probability across the different ROPEs. Only when considering a ROPE of 0.05 can KNN be considered to perform equally with SVM. Second, SVM’s performance is likely to stay below that of the standard fine-tuning approach (or, at most, its performance is estimated to stay within a 0.05 margin of fine-tuning), and is very likely to stay below that of the metric fine-tuning approach. In sum, then, both standard and metric fine-tuning appear to exhibit a stronger performance than the more traditional classification approaches. Finally, when we compare the two fine-tuning approaches, metric fine-tuning performs better than standard fine-tuning, although the difference is very likely to lie within the 0.05 ROPE margin. Still, it can be concluded that metric fine-tuning will yield better results.

6 Conclusion

As the amount of data to be processed in corpus linguistic analyses continues to grow, it has become a fair question whether LLMs can be manipulated to automate at least part of the annotation process. It is, however, not always clear how this can be achieved (e.g. which machine learning algorithms should be used), and to what extent the available options differ in their reliability. In this paper, we explored one way of using contextualized word embeddings, generated by means of MacBERTh and GysBERT, as the basis for a customizable semi-automated data annotation procedure. Additionally, to show how the reliability of the procedure may vary depending on how the procedure is implemented, we compared how four different classification algorithms performed on the task of automatically categorizing manually annotated input data by means of word embeddings. Our results indicate that the reliability of commonly used classification algorithms such as KNN and to some extent SVM can vary substantially between different case studies. In some cases, these algorithms will achieve classification accuracy and f1 scores exceeding 80 points (which means the error rate is below 20 %), whereas in other case studies their performance is more underwhelming. However, one option that stands out as consistently strong (i.e. never reaching an error rate higher than 15 %) is metric fine-tuning – a result that we were able to statistically confirm using a Bayesian model comparison.

Besides the fact that combining contextualized word embeddings from LLMs with metric fine-tuning appears to be a reliable approach to automatically annotating linguistic data, the procedure is also adaptable to the corpus linguist’s annotation needs. Furthermore, the procedure we presented has the added benefit that models used to annotated the data can be shared, and used to replicate the data annotation scheme in corroboration and follow-up studies. Thus, given its robustness, high reliability, flexibility, and potential for reusability and replicability, it is at least worth considering whether this (semi-)automated data annotation procedure could be what is next for corpus linguistic methodology.

There is, however, more to explore before LLMs can be fully integrated into corpus linguistic research. We wish to note, for instance, that the fact that LLMs such as the BERT-based MacBERTh and GysBERT can be manipulated to distinguish literal from figurative uses of a word or correctly label the semantic role of a target word in a way that is comparable to human annotators does not necessarily mean that such LLMs can be said to “understand” the concept of metaphor or agency. We can only state that the information needed to successfully make the distinctions outlined by the human annotator is encoded in the embeddings generated by the LLM (for other work pursuing similar questions on what sort of information is encoded in contextualized embeddings from LLMs, see e.g. Pedinotti et al. (2021) and Fonteyn (2021) for metaphor; Klafka and Ettinger (2020) and Proietti et al. (2022) for semantic role labelling). Additionally, an issue we have not explored is whether the information the models embed and rely upon to correctly annotate examples is the same as (or at least comparable to) the linguistic cues that corpus linguists draw upon to categorize data. And indeed, it is likely that their current lack of transparency has made (corpus) linguists more reluctant to use LLMs for linguistic data annotation. Still, we hope to have at least demonstrated that LLMs, such as the ones examined in this paper, are reliable tools to (partially) automate data annotation, and believe that a growing engagement of (corpus) linguists with LLMs may ultimately also further our understanding of why LLMs are so successful at the linguistic tasks that are assigned to them.

Funding source: Platform Digital Infrastructure Social Sciences and Humanities (PDI-SSH)

Acknowledgments

The release of the LLMs used in this study (MacBERTh and GysBERT) has been made possible by the Platform Digital Infrastructure – Social Sciences and Humanities fund (PDI-SSH). For more information, see https://macberth.netlify.app/. The case study in Section 4 was used as a pilot for the NWO Open Competition – M grant “The poetics of olfaction in early modernity (POEM)”.

Results for the individual fire metaphors classification tasks.

Results for the mass and weight classification task.

Results for the scent classification task.

References

Alsentzer, Emily, John Murphy, William Boag, Wei-Hung Weng, Di Jindi, Tristan Naumann & Matthew McDermott. 2019. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop, 72–78. MN, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/W19-1909Search in Google Scholar

Archer, Dawn, Tony McEnery, Paul Rayson & Andrew Hardie. 2003. Developing an automated semantic analysis system for Early Modern English. In Proceedings of the corpus linguistics 2003 conference (Centre for Computer Corpus Research on Language Technical Papers), 22–31. Lancaster: University of Lancaster.Search in Google Scholar

Archer, Dawn, Paul Rayson, Scott Songlin Piao & Anthony Mark McEnery. 2004. Comparing the UCREL semantic annotation scheme with lexicographical taxonomies. Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:16716198.Search in Google Scholar

Beltagy, Iz, Kyle Lo & Arman Cohan. 2019. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 3615–3620. Hong Kong: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/D19-1371Search in Google Scholar

Benavoli, Alessio, Giorgio Corani, Janez Demšar & Marco Zaffalon. 2017. Time for a change: A tutorial for comparing multiple classifiers through Bayesian analysis. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 36. 1–36.Search in Google Scholar

Brandsen, Alex, Suzan Verberne, Karsten Lambers & Milco Wansleeben. 2022. Can BERT dig it? Named entity recognition for information retrieval in the archaeology domain. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1145/3497842.Search in Google Scholar

Brinton, Laurel. 2017. The evolution of pragmatic markers in English: Pathways of change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316416013Search in Google Scholar

Budts, Sara. 2020. On periphrastic do and the modal auxiliaries: A connectionist approach to language change. Antwerp: Universiteit Antwerpen PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Camacho-Collados, Jose & Mohammad Taher Pilehvar. 2018. From word to sense embeddings: A survey on vector representations of meaning. arXiv:1805.04032 [cs]. arXiv: 1805.04032. http://arxiv.org/abs/1805.04032 (accessed 10 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Charteris-Black, Jonathan. 2016. Fire metaphors: Discourses of awe and authority. London: Bloomsbury.Search in Google Scholar

Coll Ardanuy, Mariona, Federico Nanni, Kaspar Beelen, Kasra Hosseini, Ruth Ahnert, Jon Lawrence, Katherine McDonough, Giorgia Tolfo, Daniel C. S. Wilson & Barbara McGillivray. 2020. Living machines: A study of atypical animacy. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 4534–4545. Barcelona: International Committee on Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.400Search in Google Scholar

Delobelle, Pieter, Thomas Winters & Bettina Berendt. 2020. RobBERT: A Dutch RoBERTa-based language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.06286. Available at: https://doi.org/https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.06286.10.18653/v1/2020.findings-emnlp.292Search in Google Scholar

Darwin, George Howard. 1882. IV. On the stresses caused in the interior of the earth by the weight of continents and mountains. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 173. 187–230. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1882.0005.Search in Google Scholar

Davy, John. 1865. Some observations on birds, chiefly relating to their temperature, with supplementary additions on their bones. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 14. 440–457. http://www.jstor.org/stable/112167.10.1098/rspl.1865.0077Search in Google Scholar

De Pascale, Stefano. 2019. Token-based vector space models as semantic control in lexical sociolectometry. Leuven: KU Leuven PhD dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Desagulier, Guillaume. 2019. Can word vectors help corpus linguists? Studia Neophilologica 91(2). 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393274.2019.1616220.Search in Google Scholar

De Smet, Hendrik. 2016. Entrenchment effects in language change. In Hans-Jörg Schmid (ed.), Entrenchment and the psychology of language learning: How we reorganize and adapt linguistic knowledge (Language and the Human Lifespan (LHLS)), 75–100. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1037/15969-005Search in Google Scholar

Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee & Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 4171–4186. Minneapolis, MN: Association for Computational Linguistics.Search in Google Scholar

Dozat, Timothy & Christopher, D. Manning. 2017. Deep biaffine attention for neural dependency parsing. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2017. Toulon, France: OpenReview.net. Available at: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=Hk95PK9le.Search in Google Scholar

Faraday, Michael. 1840. III. Experimental researches in electricity—seventeenth series. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 130. 93–127. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1840.0004.Search in Google Scholar

Fischer, Stefan, Jörg Knappen, Katrin Menzel & Elke Teich. 2020. The Royal Society Corpus 6.0: Providing 300+ years of scientific writing for humanistic study. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, 794–802. Marseille: European Language Resources Association. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/2020.lrec-1.99.Search in Google Scholar

Fonteyn, Lauren. 2020a. Let’s get into it: Using contextualized embeddings as retrieval tools. In Timothy Colleman, Frank Brisard, Astrid De Wit, Renata Enghels, Nikos Koutsoukos, Mortelmans Tanja & María Sol Sansiñena (eds.), The wealth and breadth of construction-based research [Belgian Journal of Linguistics 34], 66–78. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Fonteyn, Lauren. 2020b. What about grammar? Using BERT embeddings to explore functional-semantic shifts of semi-lexical and grammatical constructions. In Proceedings of the Computational Humanities Research Conference 2020, 257–268. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Workshop on Computational Humanities Research. Available at: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2723/short15.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Fonteyn, Lauren. 2021. Varying abstractions: A conceptual versus distributional view on prepositional polysemy. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 6(1). 90. https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.1323.Search in Google Scholar

Forbes, James D. 1846. Illustrations of the viscous theory of glacier motion. Part II. An attempt to establish by observation the plasticity of glacier ice. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 136(1846). 157–75.10.1098/rstl.1846.0014Search in Google Scholar

Hadiwinoto, Christian, Hwee Tou Ng & Wee Chung Gan. 2019. Improved word sense disambiguation using pre-trained contextualized word representations. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 5297–5306. Hong Kong: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/D19-1533Search in Google Scholar

Hart, Christopher. 2011. Moving beyond metaphor in the cognitive linguistic approach to CDA. In Christopher Hart (ed.), Critical discourse studies in context and cognition (Discourse Approaches to Politics, Society and Culture). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/dapsac.43.09harSearch in Google Scholar

Hart, Christopher. 2013. Constructing contexts through grammar: Cognitive models and conceptualisation in British newspaper reports of political protests. In John Flowerdew (ed.), Discourse and contexts, 159–184. London: Continuum.Search in Google Scholar

Hart, Christopher. 2015. Cognitive linguistics and critical discourse analysis. In Ewa Dabrowska & Dagmar Divjak (eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics, 322–345. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter.Search in Google Scholar

Hengchen, Simon, Ruben Ros, Jani Marjanen & Mikko Tolonen. 2021. A data-driven approach to studying changing vocabularies in historical newspaper collections. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36(1 Suppl). ii109–ii126. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqab032.Search in Google Scholar

Heylen, K., T. Wielfaert, D. Speelman & D. Geeraerts. 2015. Monitoring polysemy: Word space models as a tool for large-scale lexical semantic analysis. Lingua 157. 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2014.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Hilpert, Martin & Susanne Flach. 2020. Disentangling modal meanings with distributional semantics. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 36(2). 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqaa014.Search in Google Scholar

Hilpert, Martin & David Correia Saavedra. 2020. Using token-based semantic vector spaces for corpus-linguistic analyses: From practical applications to tests of theoretical claims. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 16(2). 393–424. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2017-0009.Search in Google Scholar

Hundt, Marianne, Melanie Röthlisberger, Gerold Schneider & Eva Zehentner. 2019. (Semi-)automatic retrieval of data from historical corpora: Chances and challenges. Talk presented at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Societas Linguistica Europaea (SLE), 23 August, 2019. Leipzig.Search in Google Scholar

Kater, Henry. 1819. An account of experiments for determining the variation in the length of the pendulum vibrating seconds, at the principal stations of the trigonometrical survey of Great Britain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 109. 337–508.10.1098/rstl.1819.0024Search in Google Scholar

Klafka, Josef & Allyson Ettinger. 2020. Spying on your neighbors: Fine-grained probing of contextual embeddings for information about surrounding words. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 4801–4811. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.434Search in Google Scholar

Koller, Veronika, Andrew Hardie, Paul Rayson & Elena Semino. 2008. Using a semantic annotation tool for the analysis of metaphor in discourse. metaphorik.de 15. Available at: https://www.metaphorik.de/sites/www.metaphorik.de/files/journal-pdf/15\text{\_}2008\text{\_}koller.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Kruschke, John K. 2013. Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 142(2). 573. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029146.Search in Google Scholar

Kulick, Seth & Neville Ryant. 2020. Parsing Early Modern English for linguistic search. arXiv:2002.10546 [cs]. arXiv: 2002.10546. http://arxiv.org/abs/2002.10546 (accessed 14 May 2021).Search in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 1996. The representation of social actors. In Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard & Malcolm Coulthard (eds.), Texts and practices: Readings in critical discourse analysis, 32–70. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Lenci, Alessandro, Magnus Sahlgren, Patrick Jeuniaux, Amaru Cuba Gyllensten & Martina Miliani. 2022. A comparative evaluation and analysis of three generations of distributional semantic models. Language Resources & Evaluation 56. 1269–1313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-021-09575-z.Search in Google Scholar

Linzen, Tal, Grzegorz Chrupała, Yonatan Belinkov & Dieuwke Hupkes (eds.). 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 ACL Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and interpreting neural networks for nlp. Florence: Association for Computational Linguistics. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/W19-4800.Search in Google Scholar

Manjavacas, Enrique & Lauren, Fonteyn. 2021. MacBERTh: Development and evaluation of a historically pre-trained language model for English (1450–1950). In Proceedings of the Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities, 23–36, India: NIT Silchar, NLP Association of India (NLPAI).Search in Google Scholar

Manjavacas, Enrique & Lauren Fonteyn. 2022a. Adapting versus pre-training language models for historical languages. Journal of Data Mining & Digital Humanities NLP4DH. https://doi.org/10.46298/jdmdh.9152.Search in Google Scholar

Manjavacas, Enrique & Lauren Fonteyn. 2022b. Non-parametric word sense disambiguation for historical languages. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities, 123–134. Taipei: Association for Computational Linguistics. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/2022.nlp4dh-1.16.10.46298/jdmdh.9152Search in Google Scholar

Marcus, Mitchell P., Beatrice Santorini & Mary Ann Marcinkiewicz. 1993. Building a large annotated corpus of English: The Penn Treebank. Computational Linguistics 19(2). 313–330.10.21236/ADA273556Search in Google Scholar

Massri, M. Besher, Inna Novalija, Dunja Mladenić, Janez Brank, Sara Graça da Silva, Natasza Marrouch, Carla Murteira, Ali Hürriyetoğlu & Beno Šircelj. 2022. Harvesting context and mining emotions related to olfactory cultural heritage. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 6(7). 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti6070057.Search in Google Scholar

Menini, Stefano, Teresa Paccosi, Sara Tonelli, Marieke Van Erp, Inger Leemans, Pasquale Lisena, Raphael Troncy, William Tullett, Ali Hürriyetoğlu, Ger Dijkstra, Femke Gordijn, Elias Jürgens, Josephine Koopman, Aron Ouwerkerk, Sanne Steen, Inna Novalija, Janez Brank, Dunja Mladenić & Anja Zidar. 2022. A multilingual benchmark to capture olfactory situations over time. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Computational Approaches to Historical Language Change, 1–10. Dublin: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2022.lchange-1.1Search in Google Scholar

Mikolov, Tomás, Kai Chen, Greg Corrado & Jeffrey Dean. 2013. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. In Yoshua Bengio & Yann LeCun (eds.), 1st international conference on learning representations, ICLR 2013, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA, May 2–4, 2013, workshop track proceedings. Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1301.3781.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, William Hallowes. 1857. II. On the construction of the imperial standard pound, and its copies of platinum and on the comparison of the imperial standard pound with the kilogramme des archives. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 8. 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspl.1856.0031.Search in Google Scholar

Mukherjee, Joybrato & Magnus Huber. 2012. Corpus linguistics and variation in English: Theory and description. Leiden: Brill.10.1163/9789401207713Search in Google Scholar

OED Online. 2022a. Weight, n.1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/226891 (accessed 17 November 2022).Search in Google Scholar

OED Online. 2022b. Mass, n.2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/114666 (accessed 17 November 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Pedinotti, Paolo, Eliana Di Palma, Ludovica Cerini & Alessandro Lenci. 2021. A howling success or a working sea? Testing what BERT knows about metaphors. In Proceedings of the Fourth BlackboxNLP Workshop on Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP, 192–204. Punta Cana: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2021.blackboxnlp-1.13Search in Google Scholar

Pennington, Jeffrey, Richard Socher & Christopher Manning. 2014. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 1532–1543. Doha: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.3115/v1/D14-1162Search in Google Scholar

Perek, Florent. 2016. Using distributional semantics to study syntactic productivity in diachrony: A case study. Linguistics 54(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/ling-2015-0043.Search in Google Scholar

Perek, Florent. 2018. Recent change in the productivity and schematicity of the way-construction: A distributional semantic analysis. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 14(1). 65–97. https://doi.org/10.1515/cllt-2016-0014.Search in Google Scholar

Petré, Peter, Lynn Anthonissen, Sara Budts, Enrique Manjavacas, Emma-Louise Silva, William Standing & Odile A. O. Strik. 2019. Early Modern Multiloquent Authors (EMMA): Designing a large-scale corpus of individuals’ languages. ICAME Journal 43(1). 83–122. https://doi.org/10.2478/icame-2019-0004.Search in Google Scholar

Piao, Scott Songlin, Paul Rayson, Dawn Archer & Tony McEnery. 2005. Comparing and combining a semantic tagger and a statistical tool for MWE extraction. Computer Speech & Language 19(4). 378–397. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.csl.2004.11.002.10.1016/j.csl.2004.11.002Search in Google Scholar

Pratt, John Henry. 1854. On the attraction of the himalaya mountains, and of the elevated region beyond them, upon the plumb-line in India. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 7. 175–182.10.1098/rspl.1854.0046Search in Google Scholar

Prentice, Sheryl. 2010. Using automated semantic tagging in Critical Discourse Analysis: A case study on Scottish independence from a Scottish nationalist perspective. Discourse & Society 21(4). 405–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926510366198.Search in Google Scholar

Proietti, Mattia, Gianluca Lebani & Alessandro Lenci. 2022. Does BERT recognize an agent? Modeling Dowty’s proto-roles with contextual embeddings. In Nicoletta Calzolari, Chu-Ren Huang, Hansaem Kim, James Pustejovsky, Leo Wanner, Key-Sun Choi, Pum-Mo Ryu, Hsin-Hsi Chen, Lucia Donatelli, Heng Ji, Sadao Kurohashi, Patrizia Paggio, Nianwen Xue, Seokhwan Kim, Younggyun Hahm, Zhong He, Tony Kyungil Lee, Enrico Santus, Francis Bond & Seung-Hoon Na (eds.), Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 4101–4112. Gyeongju, Republic of Korea: International Committee on Computational Linguistics. Available at: https://aclanthology.org/2022.coling-1.360.Search in Google Scholar

Rastas, Iiro, Yann Ciarán Ryan, Iiro Tiihonen, Mohammadreza Qaraei, Liina Repo, Rohit Babbar, Eetu Mäkelä, Mikko Tolonen & Filip Ginter. 2022. Explainable publication year prediction of eighteenth century texts with the BERT model. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Computational Approaches to Historical Language Change, 68–77. Dublin, Ireland: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2022.lchange-1.7Search in Google Scholar

Rayson, Paul & R. Garside. 1998. The claws web tagger. ICAME Journal 22. 121–123.Search in Google Scholar

Reed, Edward James & George Stokes. 1871. XVI. On the unequal distribution of weight and support in ships, and its effects in still water, in waves, and in exceptional positions onshore. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 161. 413–465. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1871.0017.Search in Google Scholar

Reif, Emily, Ann Yuan, Martin Wattenberg, Fernanda B. Viegas, Andy Coenen, Adam Pearce & Been Kim. 2019. Visualizing and measuring the geometry of BERT. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.02715.Search in Google Scholar

Rissanen, Matti. 2004. Grammaticalisation from side to side: On the development of beside(s). In Hans Lindquist & Christian Mair (eds.), Studies in corpus linguistics, vol. 13, 151–170. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/scl.13.08risSearch in Google Scholar

Schunck, Edward. 1853. III. On rubian and its products of decomposition. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 143. 67–107. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1853.0003.Search in Google Scholar

Tayyar Madabushi, Harish, Laurence Romain, Dagmar Divjak & Petar Milin. 2020. Cxgbert: BERT meets construction grammar. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 4020–4032. Barcelona: International Committee on Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.355Search in Google Scholar

de Vries, Wietse, Andreas van Cranenburgh, Arianna Bisazza, Tommaso Caselli, Gertjan van Noord & Malvina Nissim. 2019. BERTje: A Dutch BERT model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.09582. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1912.09582.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Xinyu, Yong Jiang, Nguyen Bach, Tao Wang, Zhongqiang Huang, Fei Huang & Kewei Tu. 2021. Automated concatenation of embeddings for structured prediction. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long papers), 2643–2660. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.206Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Shufan, Laure Thompson & Mohit Iyyer. 2021. Phrase-BERT: Improved phrase embeddings from BERT with an application to corpus exploration. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 10837–10851. Punta Cana: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.846Search in Google Scholar

Wiedemann, Gregor, Steffen Remus, Avi Chawla & Chris Biemann. 2019. Does BERT make any sense? Interpretable word sense disambiguation with contextualized embeddings. Proceedings of the Conference on Natural Language Processing (KONVENS). Erlangen, Germany: Association for Computational Lingustics.Search in Google Scholar

Wolf, Thomas, Lysandre Debut, Victor Sanh, Julien Chaumond, Clement Delangue, Anthony Moi, Pierric Cistac, Tim Rault, Remi Louf, Morgan Funtowicz, Joe Davison, Sam Shleifer, Patrick von Platen, Clara Ma, Yacine Jernite, Julien Plu, Canwen Xu, Teven Le Scao, Sylvain Gugger, Mariama Drame, Quentin Lhoest & Alexander Rush. 2020. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, 38–45. Online: Association for Computational Linguistics.10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-demos.6Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese