Abstract

Landslides are one of the natural hazards, which have significant negative effects on both humans and the environment. Thus, slope stability analyses and stabilization processes are necessary to obviate or mitigate landslides. In this study, the effect of groundwater level fluctuations and the construction of a building (i.e., a recently built church) on slope stability was investigated on the eastern slope of the Avas Hill, at Miskolc, in Northeast Hungary. Soil movements and groundwater levels were monitored and geological and slope stability models were constructed. Furthermore, the possibility of constructing a retaining system was evaluated to minimize the detrimental effects of both groundwater level fluctuations and the construction of the church. The findings showed that the fluctuation in groundwater levels had a destructive effect on slope stability due to pore-water pressure, which decreased the soil strength of the slope and slope stability. On the other hand, the church added an external load onto the underlying soil leading to an increase in slope instability. Hence, we suggested constructing retaining structures such as gravity retaining walls to increase the soil shear strength and enhance slope stability in the long term.

1 Introduction

Natural hazards, such as landslides, volcanic eruptions, floods, and earthquakes, are natural phenomena that occur without any human interference. They have significant negative effects on both humans and the environment as well. Landslides, which are defined as mass rock, debris, and slope processes are the most common natural hazard in mountainous regions [1]. In the last few years, many disasters resulting in thousands of deaths, injuries, and economic losses were caused by landslides [2]. They occur when a part of the natural slope becomes unstable, and moves when it fails to carry its weight. Therefore, it is imperative to investigate slope stability for interpreting the landslide mechanism, and to avoid its occurrence. Many factors govern the stability of a slope. They can be categorized into two main groups: natural and artificial factors [3,4]. One of the natural triggering factors is water, which is represented by variations in groundwater levels [5], snowmelt [6], or heavy rainfall [7]. The groundwater level plays a significant role in the evaluation and interpretation of landslide stability. Numerous landslide studies have revealed that water affects slope stability [8,9,10,11]: increasing groundwater levels and consequently increasing pore water pressure, groundwater exfiltration, uplifting due to hydraulic pressure, and the effect of water on landslide plasticity are ways in which water affects slope stability. The artificial factor is extensively represented by anthropogenic interactions, which are related to increased population, plantation, deforestation, quarrying, mining, and construction activities as a result of growing urbanization [12,13]. Then, the removal of deep-rooted vegetation binding colluviums to the bedrock followed by construction processes on the slopes are the principal manmade factors threatening landslide stability. Root fibers increase the shear strength of the soil reducing slope deformation [14,15]. Additionally, these roots also reduce rainwater infiltration and delay the rising of the groundwater table [18].

Hence, many soil improvement and stabilization processes were suggested to avert or mitigate this hazardous phenomenon by increasing the strength of the soil. These stabilizing techniques can be mechanical [19,20], chemical [21,22,23,24], or biological [17,25,26,27]. Additionally, structural techniques such as retaining systems [28,29], stabilizing piles [30], and drainage tunnels [31] are used to mitigate soil instability.

Retaining systems are one of the common structural techniques to enhance soil stability [32,33]; they can hold back and strengthen the soil that has a problem in consolidation. These systems consist of a retaining wall constructed to retain the vertical or slightly vertical banks of earth materials or any other material. There are many types of retaining walls such as gravity walls, cantilever walls, fort-counter walls, anchors walls, and piled walls.

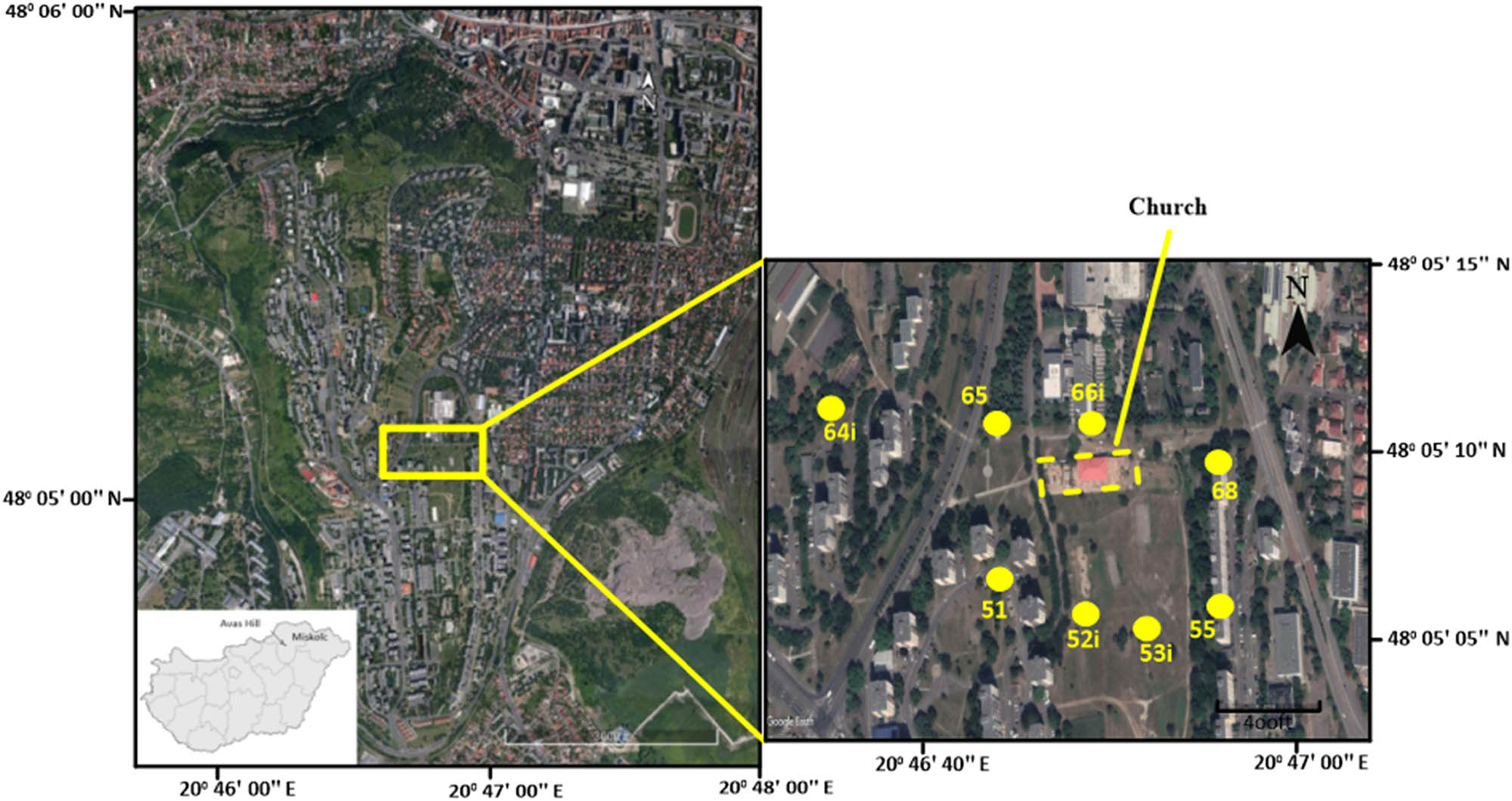

Hungary is a country that faces the threat of landslides [34]. The Avas Hill in the Northeast of Hungary is an area where plenty of landslides occur. Several landslides have occurred here earlier. Soil movements continue now too in this area [35], particularly, in the Northeast of the Bükk Mountains, at Miskolc, which also is the case study area of this project (Figure 1). In the last decades, as a result of landslides, soil movements were detected in Avas Hill with less than 2.5 mm/year displacement negatively affecting the upper part of the soil [36,37]. Although this displacement rate may not be enough to constitute a danger, any higher levels of surface movement could trigger landslides and endanger surrounding buildings. Recently, the landslides in Avas Hill have caused large fractures and joints in some buildings. They have also tilted trees and fences. However, the effects of groundwater, construction, and retaining systems on slope stability in this area have not been discussed earlier in any study. Hence, this study aims to comprehensively investigate the effects of groundwater fluctuations (natural factor) and constructing processes (artificial factor) on the slope stability of Avas Hill, at Miskolc, in the Northeast of Hungary. Moreover, we seek to reduce the soil movement effect and thereby increase slope stability by constructing gravity-retaining walls. For this purpose, the following approaches were taken: (1) monitoring the levels of groundwater in wells and the rate of soil displacement; (2) evaluation of slope stability on a finite slope using GEO5 software; and (3) evaluation of groundwater fluctuations, constructions, and the effect of retaining systems on slope stability using GEO5 software.

The map view of Avas Hill. The yellow circles represent the observation wells of the fifth and sixth lines.

1.1 Location and climate

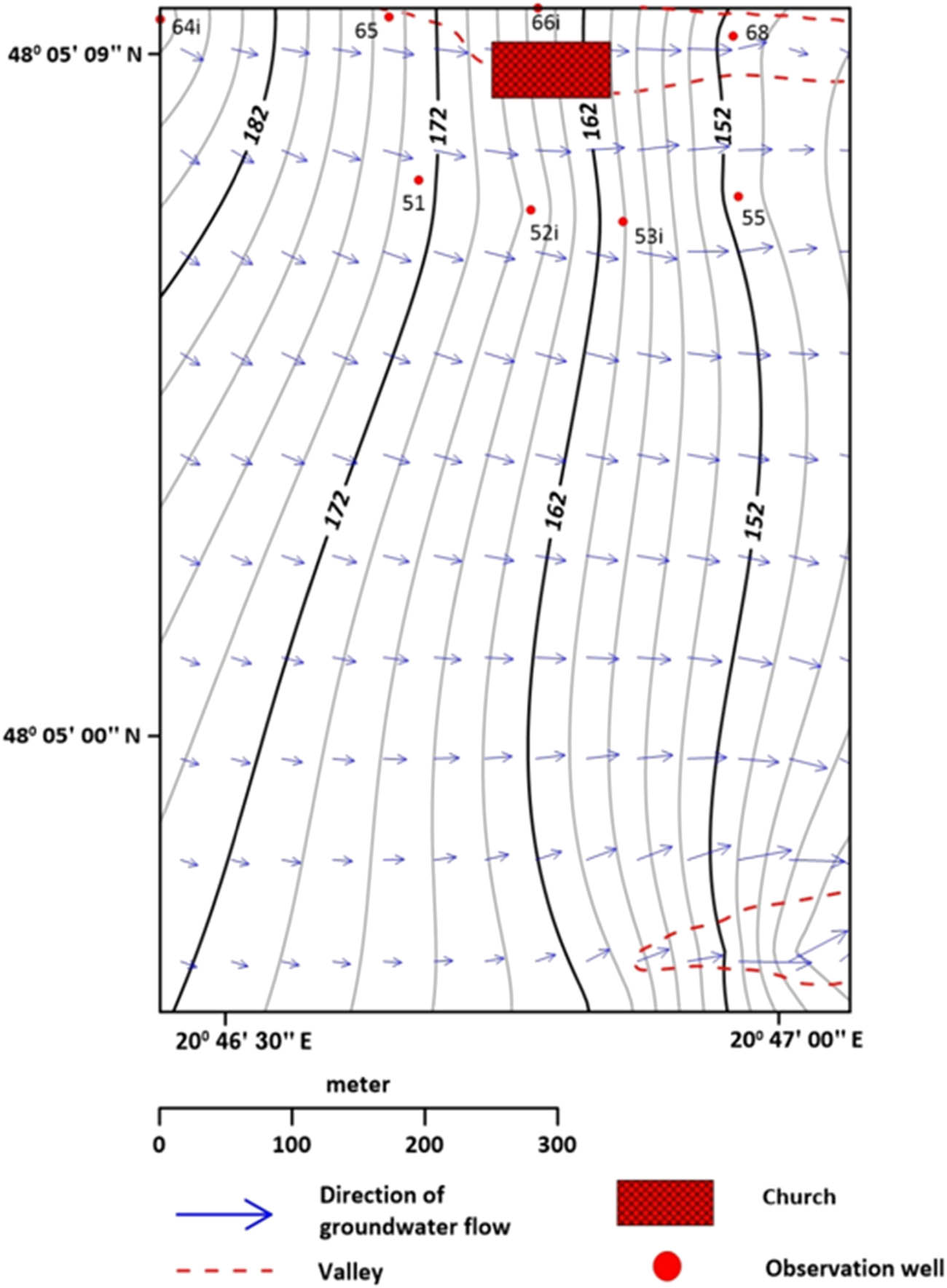

The study area is located between latitudes 48° 05′ 03″ N and 48° 5', 15″ N and longitudes 20° 46′ 31″ E and 20° 47′ 05″ E (Figure 1). It is part of the Avas Hill, at Miskolc city, in Northeast Hungary, which was studied geologically, hydrogeologically, and geotechnically earlier [35]. It lies 124 m above sea level. The climate of Miskolc is classified as temperate and warm. The rate of rainfall in Miskolc is remarkable, as precipitation has occurred during the driest month as well. The average annual precipitation is about 551 mm/year. The maximum amount of rainfall occurs in July with an average of 83 mm; otherwise, the minimum amount of rainfall occurs in January with an average of 26 mm. Figure 1 shows eight observation wells (51, 52i, 53i, 55, 64i, 65, 66i, 68), which were used to measure the changes in soil displacements and groundwater fluctuation. Wells of 51, 52i, 53i, and 55 belong to the fifth line, while 64i, 65, 66i, and 68 wells are related to the sixth line.

1.2 Geological setting

Generally, Avas Hill’s basement consists of Mesozoic rocks (Middle–Upper Triassic Bükkfennsík limestone), which are known here only from boreholes with a depth of about −100 to −200 m (Figure 2). This limestone is subjected to strong faulting and folding tectonics, which appears most prominently in the central part of the Bükk Mountains [38,39].

The Triassic limestone is covered with angular unconformity by Karpatian (upper part of the Lower Miocene) brackish and shallow marine deposits after a long weathering and erosion period. These deposits are clayey, silty, and sandy beds intercalated by thin layers of rhyolitic tuff, tuffite, and brown coal (Salgótarján Formation). The thickness of the Carpathian deposits ranges between 50 and 100 m. These deposits outcrop only on the western side of the Avas Hill. The Avas main mass, which overlain the Karpatian deposits, is built up of Middle Miocene (Badenian–Sarmatian) rhyolitic pyroclasts mixed with clastic sediments or pure volcanic material (Sajóvölgy Formation). This formation has a thickness between 55 and 100 m. The dip angle of layers is between 5 and 12 degrees toward S and SE. Sajóvölgy Formation’s lower part consists of rhyolitic tuffs, while the upper part consists of highly variable beds of mostly andesitic tuff. The depositional and structural character of the andesitic sequence indicates that it was formed mainly in the continental (terrestrial, lacustrine, and fluvial) environment based on the presence of flora (Acer trilobatum [Brongt.], Carpinus grandis [Ung.], Phragmites oeningensis [Brongt.], and Salix varians [Göpp.]) in the andesitic tuffs [40].

The Sajóvölgy Formation is overlaid by Pannonian deposits (Edelény Formation), which were only found in artificial exposures and drill holes. The thickness of the Pannonian deposits ranges between 2 and 30 m. The paleoenvironment of the Pannonian sequence was lacustrine, and fluvial, as indicated by the clayey–silty lithofacies and cross-bedded lenses in the sand, respectively [40]. Quaternary rocks cover the Pannonian sequence with 1–25 m in thickness. They are composed of aeolian and fluvial deposits, which originated from the weathering process of the andesitic tuffs (the upper part of Sajóvölgy Formation). Moreover, clastic sediments such as gravel and silty sand beds can also be found. These clastic sediments mainly originated from the metamorphic rocks, with a lesser amount of fragments from the limestones or the local volcanics of Bükk Mountains.

2 Methodology

2.1 Monitoring of soil movement and groundwater fluctuation

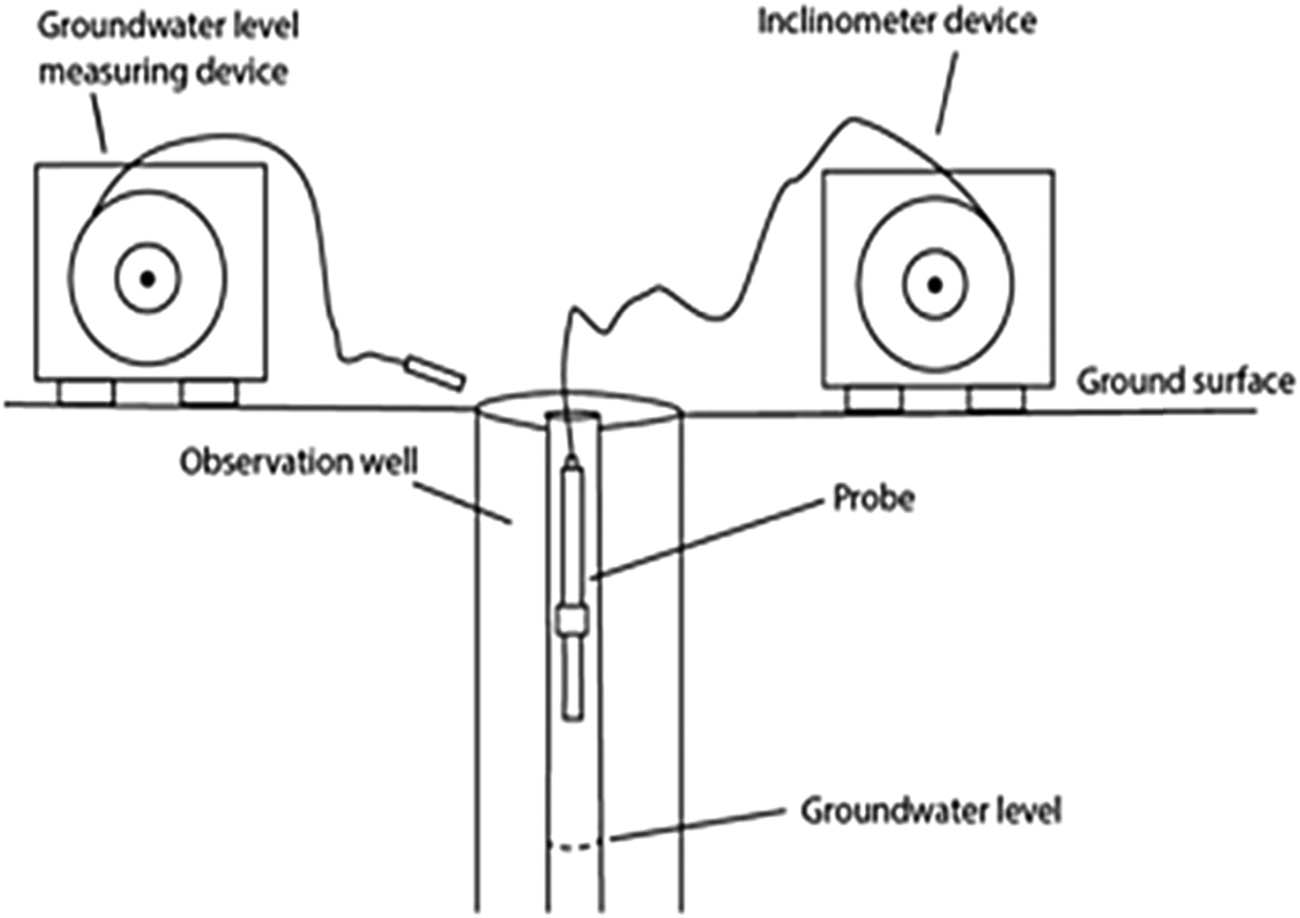

The field investigations were carried out in Avas Hill, at Miskolc city, to obtain the data required to analyze slope stability. The slope monitoring system installed on Avas Hill consists of eight small, shallow diameter observation wells to measure the changes in soil displacements (52i, 53i, 64i, and 66i) and groundwater fluctuation (51, 52i, 53i, 55, 64i, 65, 66i, 68) using inclinometer and groundwater devices, respectively (Figure 3). The groundwater level measurements were carried out weekly correlating with rainfall, and inclination measurements per month. Rainfall is one of the most common factors controlling these groundwater variations. Therefore, it was investigated for the short (per hour) and long period (per month) [43]. Based on these data and other previous data [36,37,40,44,45] that identified the lithology and general mechanical soil properties of the observation wells in the study area, we can analyze the slope stability under these conditions with other simulated parameters, for instance, the changing of the groundwater levels, construction effect (church), and soil properties.

Schematic of the monitoring system.

2.2 Geological modeling

Based on the core drilling results, the geological model was constructed with two cross-sections of the fifth and sixth lines of observation wells. Golden Software Surfer 2020 was applied to illustrate the engineering geological model of the research area. Before using the program, the Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of the studied wells were converted from the World Geodetic System (WGS 84) to Unified National Projection (EOV), based on the Baltic Sea as a standard sea level for Hungary. The input data included the elevations of the ground surface, Quaternary clay, and Pannonian clay based on data obtained from the observation wells. Furthermore, the groundwater level was measured and linked with the previous elevation data (Table 1).

Simulated parameters input in the Surfer program for engineering geological modeling

| Well no. | GPS coordinates | Groundwater level (m) (Oct., 2020) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGS 84 | EOV | Elevation (m) | ||||||

| Latitude | Longitude | (Y, m) | (X, m) | Ground-surface | Quaternary clay | Pannonian clay | ||

| 51 | 48° 05′ 06.65″ N | 20° 46′ 44.11″ E | 778998.32 | 306054.61 | 172.822 | 167.489 | 163.389 | 168.392 |

| 52i | 48° 05′ 05.86″ N | 20° 46′ 48.18″ E | 779082.82 | 306032.01 | 167.64 | 166.640 | 158.14 | 166.050 |

| 53i | 48° 05′ 05.53″ N | 20° 46′ 51.53″ E | 779152.25 | 306023.2 | 160.200 | 159.200 | 150.100 | 155.900 |

| 55 | 48° 05′ 06.07″ N | 20° 46′ 55.74″ E | 779239.54 | 306042.16 | 150.876 | 149.276 | 140.176 | 145.656 |

| 64i | 48° 05′ 10.72″ N | 20° 46′ 34.82″ E | 778803.28 | 306176.31 | 188.976 | 187.476 | 184.176 | 182.626 |

| 65 | 48° 05′ 10.68″ N | 20° 46′ 43.18″ E | 778975.91 | 306178.13 | 174.995 | 173.395 | 170.855 | 171.525 |

| 66i | 48° 05′ 10.79″ N | 20° 46′ 48.58″ E | 779088.15 | 306184.84 | 165.202 | 162.602 | 155.702 | 161.942 |

| 68 | 48° 05′ 10.00″ N | 20° 46′ 55.70″ E | 779235.58 | 306163.64 | 150.876 | 149.276 | 140.176 | 144.996 |

2.3 Evaluation of slope stability on a finite slope

The factor of safety (FS) is generally an essential parameter to evaluate slope stability. Table 2 shows the ranges of custom minimum total safety factors (F) as reported by Terzaghi and Peck [46] and recommended in the Canadian Foundation Engineering Manual (1992) [47]. The upper values of these total safety factors relate to normal loads and service conditions, while the lower values can be applied for maximum loads and worst geologic conditions.

| Failure type | Category | Safety factor range |

|---|---|---|

| Shearing | Earthworks | 1.3-1.5 |

| Earth retaining structures, excavations | 1.5–2 | |

| Foundations | 2–3 | |

| Seepage | Uplift, heave | 1.5–2 |

| Exit gradient, piping | 2–3 |

Principally, the FS of the slope is the ratio between the resisting force and the driving force, and can be obtained from the following equation (1):

The shear strength of soil (τ f) is composed of two components: cohesion and friction. It can be defined by the failure criterion of the Mohr–Coulomb [48] as illustrated in equation (2):

where c, σ, and ϕ denote cohesion, normal stress at rupture surface, and angle of internal friction, respectively.

Table 3 shows the limited equilibrium methods of slope stability utilized in the GEO5 program, which was applied to calculate the values of FS based on different analytical methods such as Fellenius/Petterson [49], Bishop [50], Spencer [51], Janbu [52], and Moregenstern-price [53]. These methods were classified based on the shape of the slip surface, which is known as a failure surface or surface of sliding where the soils or rocks slip. The slip surface has four types: circular, non-circular, transitional, and compound [54,55]. FS calculations were conducted based on the Bishop Optimization method under the following conditions: before and after the construction of the church and retaining system, as well as groundwater dropping.

Limited equilibrium methods of slope stability applied in the GEO5 program

| Method type | Assumption | Slip surface | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fellenius/Petterson | Acting forces on the sides of slices are neglected | Circular | [49] |

| Bishop | Acting forces on the sides of slices are horizontal without acting shear force between slices | [50] | |

| Spencer | The inter-slice forces are parallel with the same inclination. Normal forces are active on the base of the slice | Non‐circular | [51] |

| Janbu | The inter-slice normal force location is defined by the thrust line | [52] | |

| Morgenstern-price | The inter-slice shear and inter-slice normal forces are related to each other. Normal forces act on the base of the slice | [53] |

This program is a finite element program that was designed to find solutions to geotechnical problems. The main advantages of the GEO5 program are analysis of the slope situation, finding the problems, accuracy improving, and saving time. Besides, it can be used after a long time of work break to modify the structure design. GEO5 program has used standard information and knowledge in many countries based on common and well-known theories. The program has complaints with Eurocode 7 (EN 1997-1) [56] and LRFD (AASHTO standards) [57].

Generally, the Bishop method is the most widely used technique nowadays [58]. It is used to identify the highest optimum critical slip surface of the slope. When it is used in the GEO5 program, accurate and satisfactory results can be obtained. Here, the settings of the program were adjusted based on the cross-sections of the fifth and sixth line observation wells. These cross-sections were obtained from the Golden Software Surfer 2020. Also, the standard of FS was set at about 1.5 in this study.

2.3.1 Evaluation of groundwater fluctuation and construction influences

The simulated parameters of layers (Table 4) associated with those of the groundwater levels and dimensions of the church (Tables 5 and 6) were used as input data in the GEO5 program to calculate the FS before and after the groundwater level fluctuations and construction effects of the church on the finite slopes, respectively. These parameters were obtained based on the standard values of soil types involved in the GEO5 program. These parameters, such as unit weight (γ), internal friction angle (ϕ ef), soil cohesion (c ef), and saturated unit weight (γ sat), are listed in Table 2. The church built on the eastern slope of the Avas Hill between the lines of the fifth and sixth observation wells affected slope stability (Figure 1). The groundwater levels and construction effect data were obtained based on the cross-sections of the fifth and sixth line observation wells. These cross-sections were obtained from the Surfer program.

Simulated strength parameters of the layers input in the GEO5 program to calculate the FS before and after the groundwater fluctuations and construction

| Parameters | Landfill | Quaternary clay | Pannonian clay |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ (kN/m3) | 20.00 | 20.50 | 18.50 |

| ϕ ef (°) | 36.50 | 15.00 | 24.50 |

| c ef (kPa) | 0.00 | 5.00 | 14.00 |

| γ sat (kN/m3) | 20.00 | 20.50 | 18.50 |

Groundwater level coordinate data input in the GEO5 program

| Well no. | Line No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fifth | Sixth | |||

| (X*, m) | (Z**, m) | (X*, m) | (Z**, m) | |

| 51 | 0.00 | 1.48 | — | — |

| 52iu | 2.87 | 1.01 | — | — |

| 53iu | 4.66 | 0.64 | — | — |

| 55 | 6.10 | 0.25 | — | — |

| 64i | — | — | 0.00 | 1.30 |

| 65 | — | — | 2.43 | 0.92 |

| 66i | — | — | 3.93 | 0.65 |

| 68i | — | — | 6.10 | 0.29 |

*Represents the horizontal coordinate (distance) of a finite slope in the GEO5 program.

**Represents the vertical coordinate (elevation) of a finite slope in the GEO5 program.

Simulated parameters of surcharge (church) input in the GEO5 program

| Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Magnitude (kN/m2) | Slope (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 78.37 | 34.84 | 13–16 | 500 | 8 |

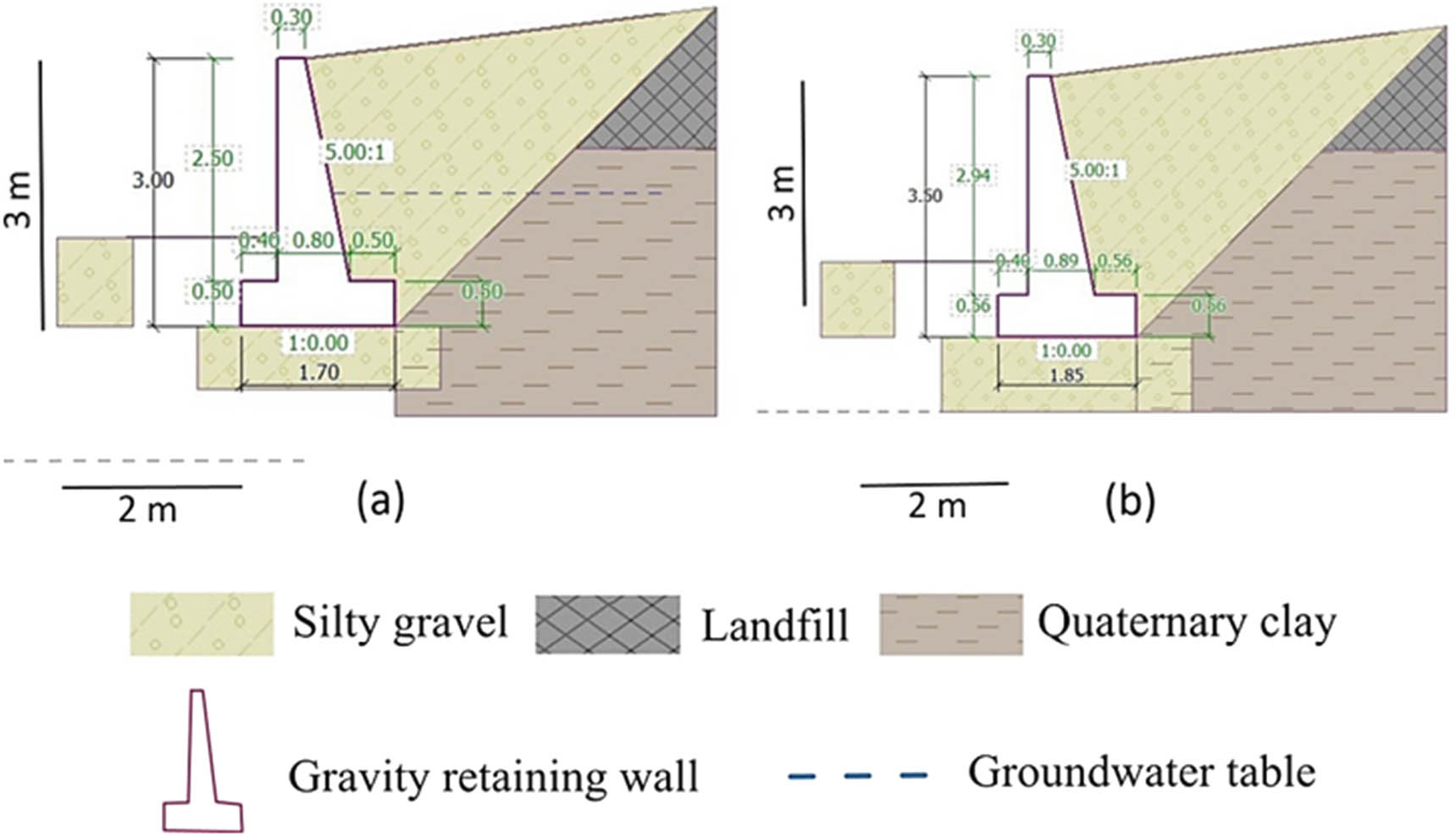

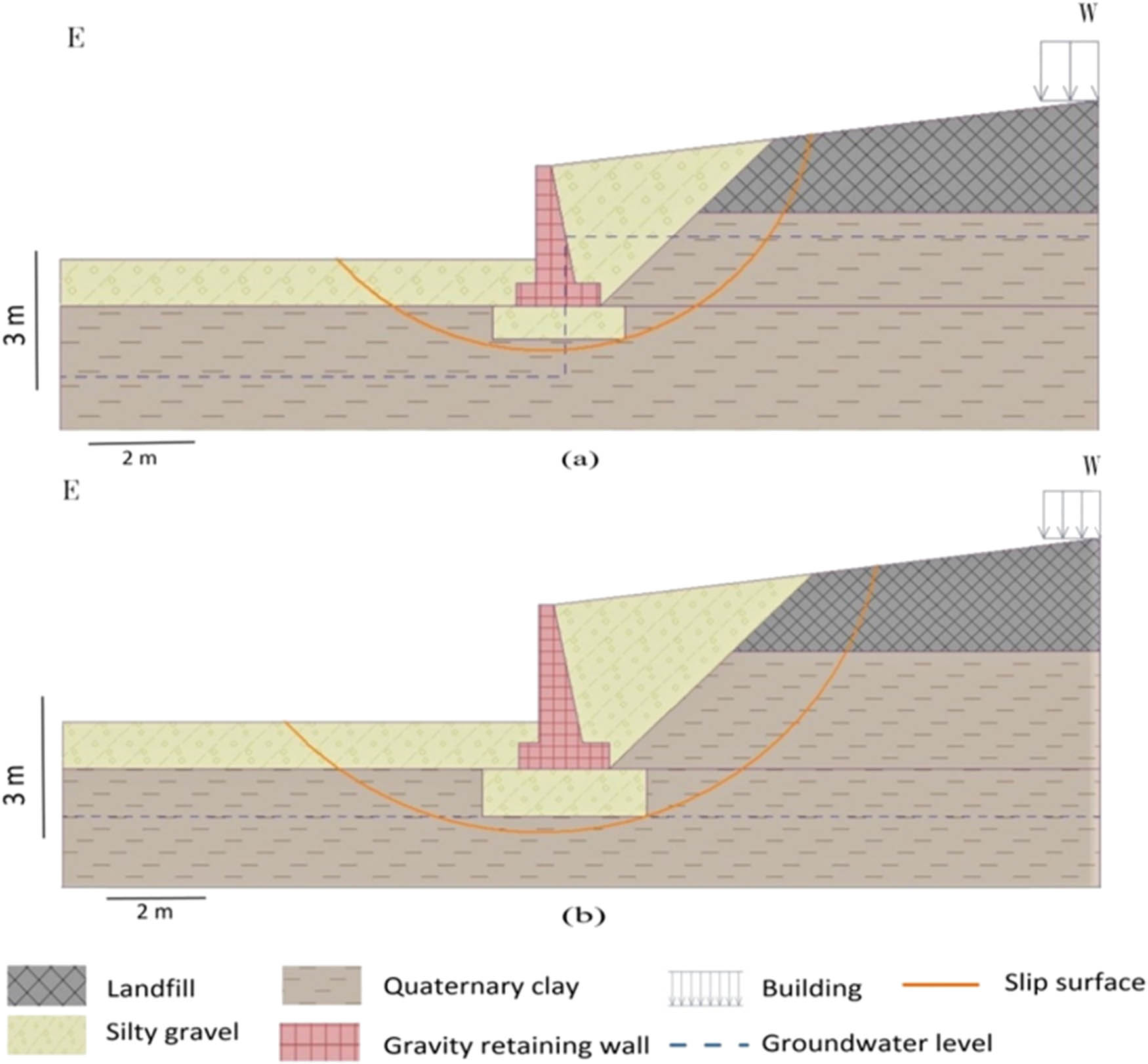

2.3.2 Influence of the retaining system

Retaining systems include many types of retaining structures such as gravity walls, cantilever retaining walls, fort-counter retaining walls, anchors retaining walls, or piled retaining walls [58,59,60]. In this study, the gravity retaining wall was constructed to increase the shear strength of soil in the fifth and sixth lines of observation wells. This type is the most commonly applied due to its economical features, so it was selectively nominated. Concrete and gravel are the two components of this gravity retaining wall. Concrete is one of the most common and effective materials used to construct a shield against artificial or natural hazards [61,62,63,64,65].

The simulated parameters of the gravity retaining system input in the GEO5 program are related to the fifth and sixth line observation wells. The used parameters are listed in Tables 7 and 8. These parameters include foundation soil, frontfill, and backfill, which are composed of silty gravel (Table 7). Table 8 shows the groundwater level and parameters of the material used in the wall structure such as compressive strength (f ck ) and tensile strength (f ctm ) of concrete, yield strength (f yk ) of the reinforcing steel bars, and unit weight of the wall (γ). Figure 4 illustrates the simulated dimensions of the gravity retaining system based on the fifth and sixth lines.

Simulated strength parameters of frontfill, backfill, and soil foundation input in the GEO5 program for setting up the retaining system

| γ (kN/m3) | ϕ ef (°) | c ef (kPa) | γ sat (kN/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 32.5 | 4 | 19 |

Simulated parameters of the gravity retaining wall system input in the GEO5 program

| Parameters | Line fifth | Line sixth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material of wall structure | Concrete | f ck (MPa) | 80 | 80 | |

| f ctm (MPa) | 4.8 | 4.8 | |||

| Reinforcing steel bars | f yk (MPa) | 500 | 500 | ||

| γ (kN/m3) | 23 | 23 | |||

| Foundation soil | Geometry | Thickness (m) | 0.7 | 1 | |

| Offset left (m) | 0.5 | 0.7 | |||

| Offset right (m) | 0.5 | 0.7 | |||

| Soil type | Silty gravel | Silty gravel | |||

| Frontfill | Thickness (m) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Soil type | Silty gravel | Silty gravel | |||

| Backfill | Slope (°) | 45 | 45 | ||

| Soil type | Silty gravel | Silty gravel | |||

| Groundwater level | In front of construction (m) | 4.5 | 4.5 | ||

| Behind construction (m) | 1.5 | 4.5 | |||

Simulated dimensions of gravity retaining walls in the slope of: (a) fifth observation wells and (b) sixth observation wells.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Monitoring

3.1.1 Soil movement

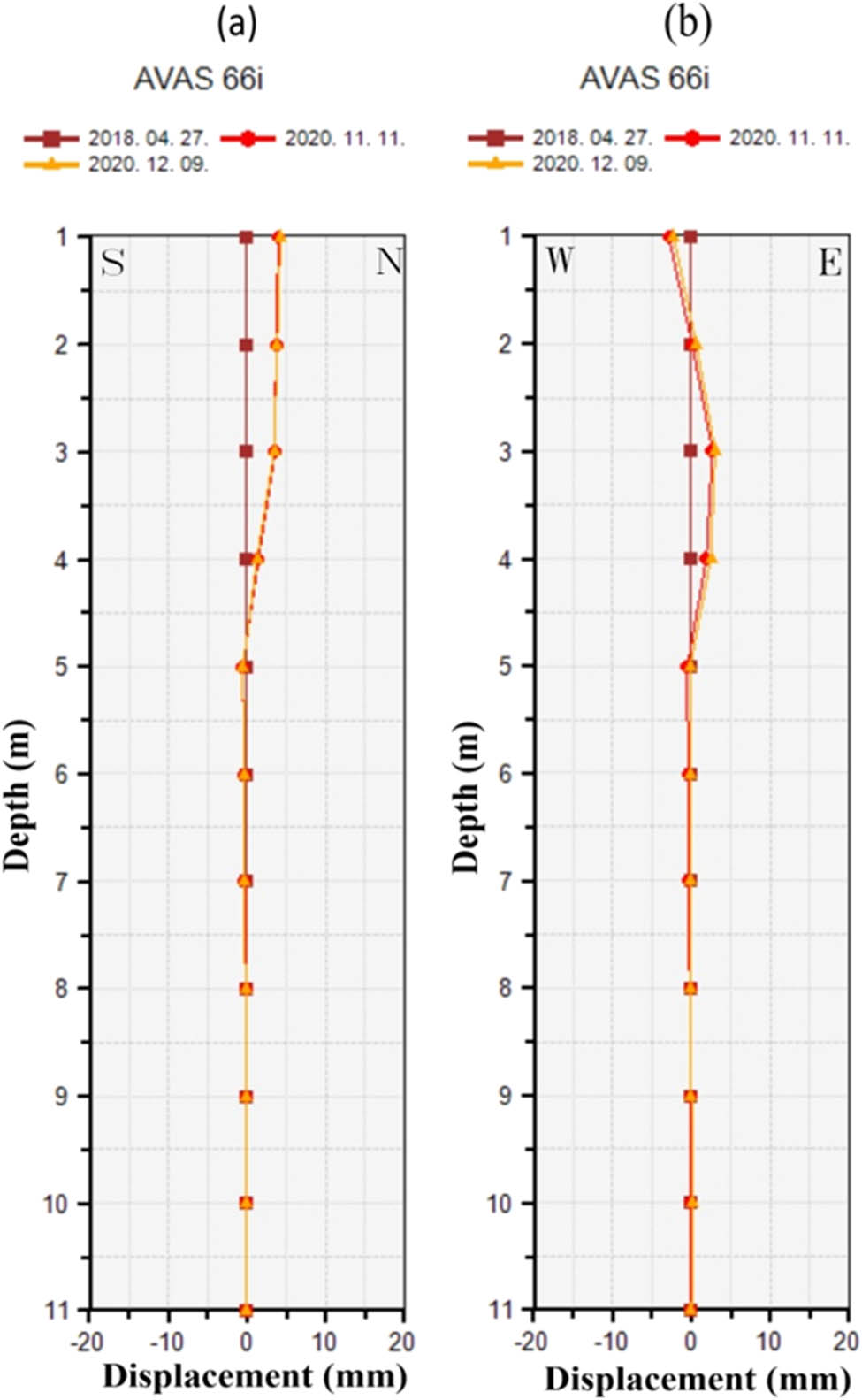

As shown in Figure 5, the results of the inclinometer measurements show that there is a type of soil movement with a displacement of nearly 2 mm/year in an oblique direction toward the NW–NE from April 2018 to November 2020. Compared to the measurements conducted in April 2018, the recent measurements (Figure 5) show that the soil movement was more effective on the uppermost first 5 m of the soil. In the first 3 m of the uppermost soil, the displacement rate is about 2 mm/year toward the NW direction of the two first meters and NE direction to the rest. After that, this rate decreases to zero value at about 5 m. After 5 m, the displacement becomes not active.

Cross-section views show the relationship between the rates of soil displacements and depth at the observation wells of 66i from: (a) N–S direction and (b) E–W direction.

3.1.2 Groundwater fluctuation

Groundwater fluctuation is one of the main reasons for slope instability [66,67]. The hydrogeological map of the study area illustrates that groundwater is accumulated in the east–southeast of Avas based on data collected from the observation wells (Figures 6 and 7). The pore pressure of water reduces the soil effective stresses and consequently the soil shear strength [68]. Subsequently, a severe hazard leads to the collapse of the ground surface and the construction.

Groundwater flows from the West part of the study area into the East–Southeast.

Relationship between Groundwater and rainfall levels for about 2.5 months.

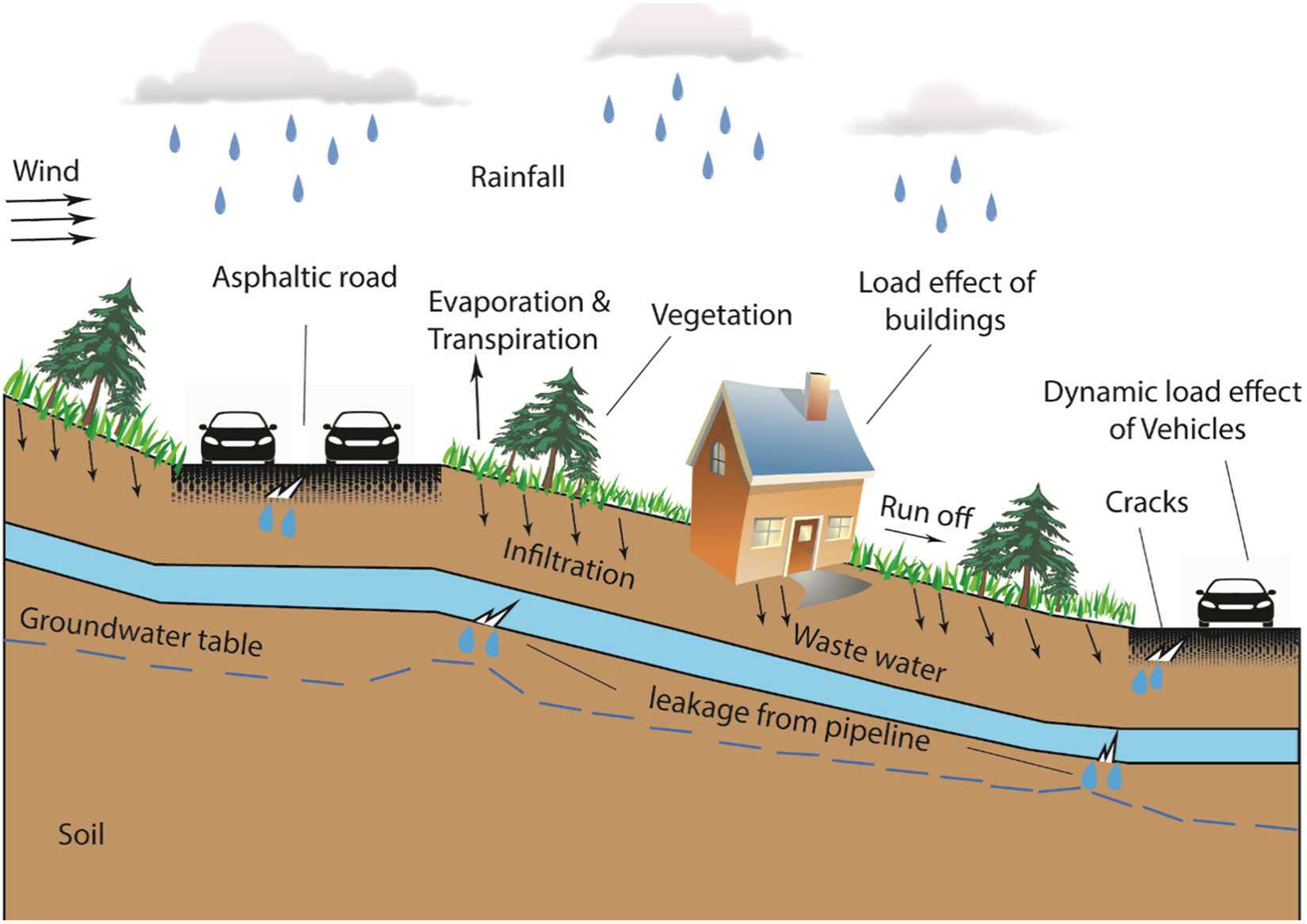

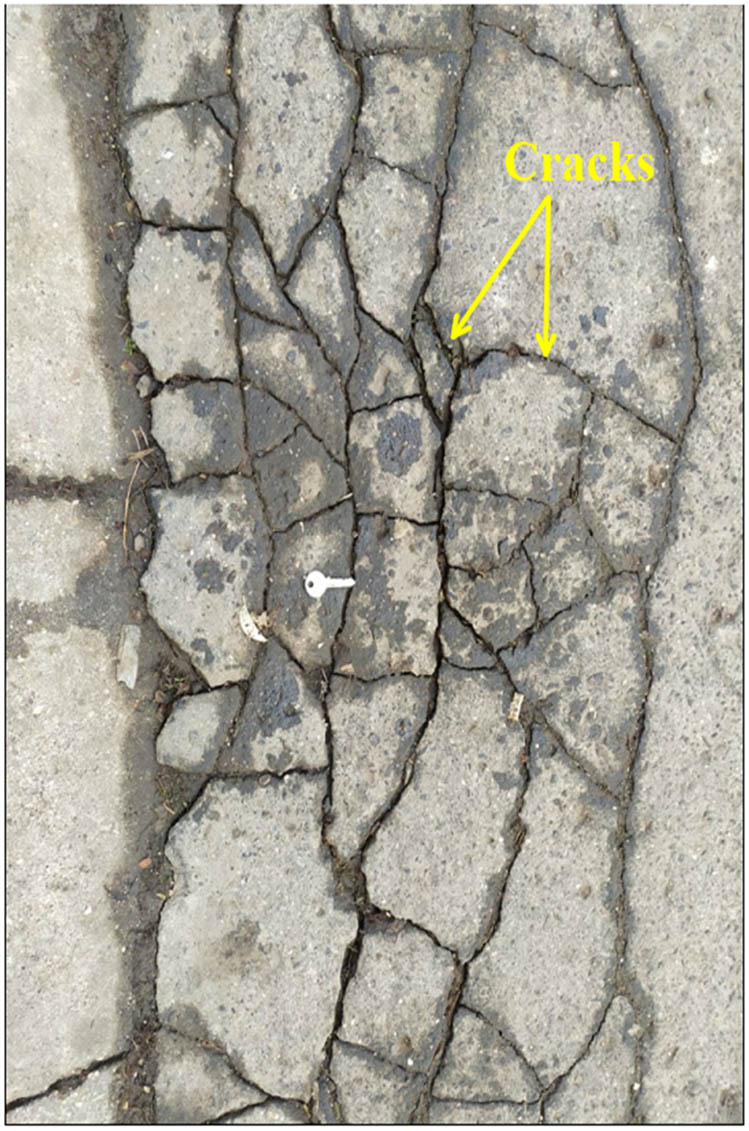

Compared to the rainfall level, the monitoring data of underground water level does not indicate a connected aquifer. This is illustrated in Figure 7, where the levels of rainfall and underground water are not consonant. This can be attributed to both natural and artificial factors. The natural one is related to the lithological composition of the underlying impermeable soil, which is composed of clay and sandy clay (Figure 8), while the artificial ones (Figure 8) include leakage from the network pipeline, construction pits, or construction of the deep foundation [35]. Additionally, the impermeable coverage of the asphaltic layer capping the road of the area plays an influential role in the changes in underground water levels. This can be assigned to its predominance of joints and tensional cracks (Figure 9), which contribute to the infiltration of surface water (i.e., rainfall, runoff, the water of freeze-thaw, etc.) into the ground [33]. These cracks can be attributed to the weak strength of the upper landfill layer [38].

Detailed schematic illustrates several factors affecting groundwater levels.

Tensional cracks in the asphalt coverage of the study area.

Although the infiltration is responsible for slope failure [16,69], this is not achieved in this study. This can be attributed to the artificial drainage systems (e.g., drainage ditches), which were constructed to reduce the infiltration of slope water into the ground (Figure 10).

Drainage ditch (artificial systems) to diminish slope water infiltration.

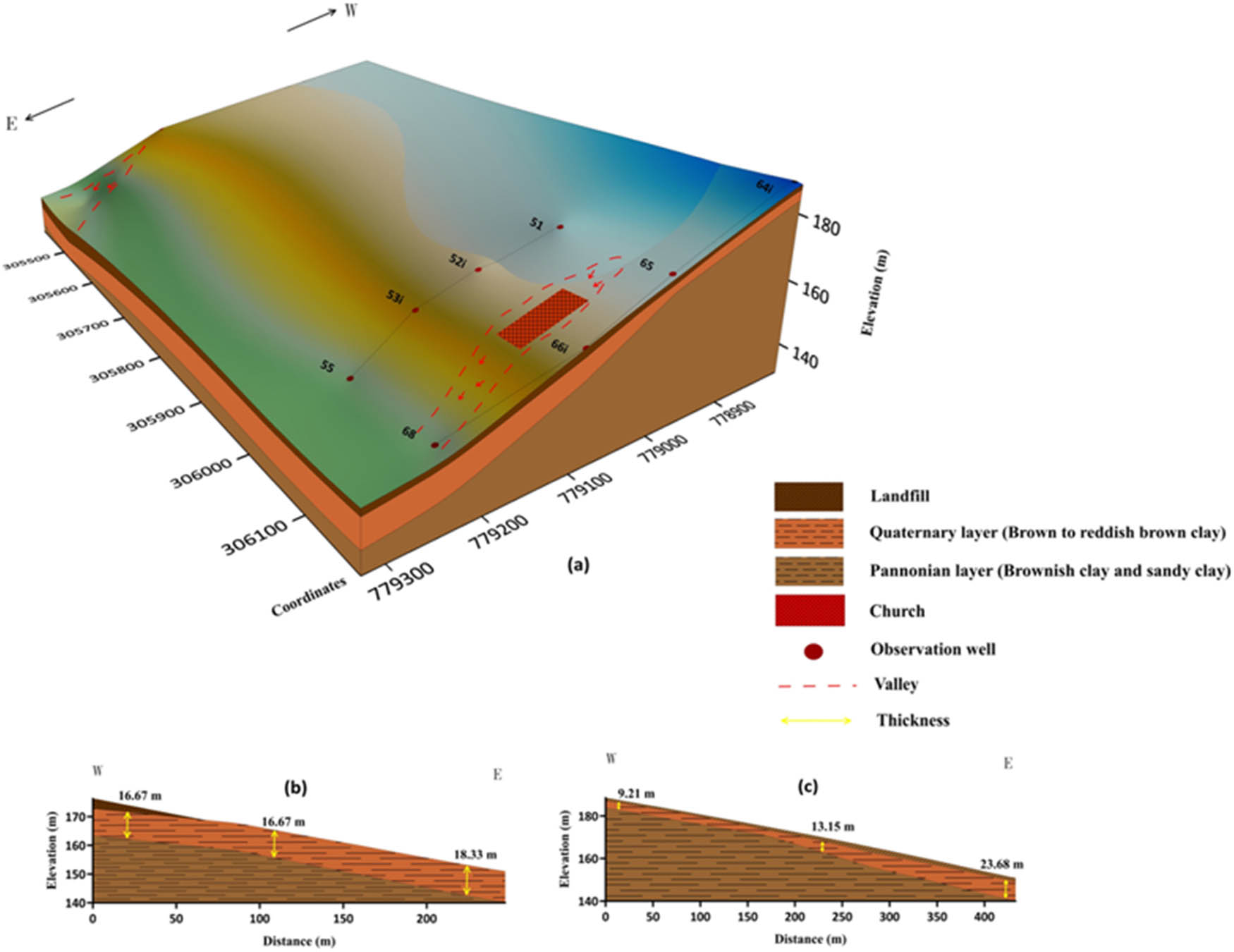

3.2 Engineering geological modeling

Figure 11 illustrates the engineering geological modeling of the eastern side of Avas Hill, which was drawn with the knowledge of the two lines of observation wells (fifth and sixth) having 4.5–10 m depth. This modeling shows that the Avas Hill consists of two layers, Quaternary (mainly reddish-brown to brown clay) and Pannonia (dominantly brownish clay and sandy clay), according to GeoExpert Geotechnikai tervező és szakértő Kft, 2013. Also, it is deduced that the slope dips to the east, and the two geological profiles of the two lines of observation wells (fifth and sixth).

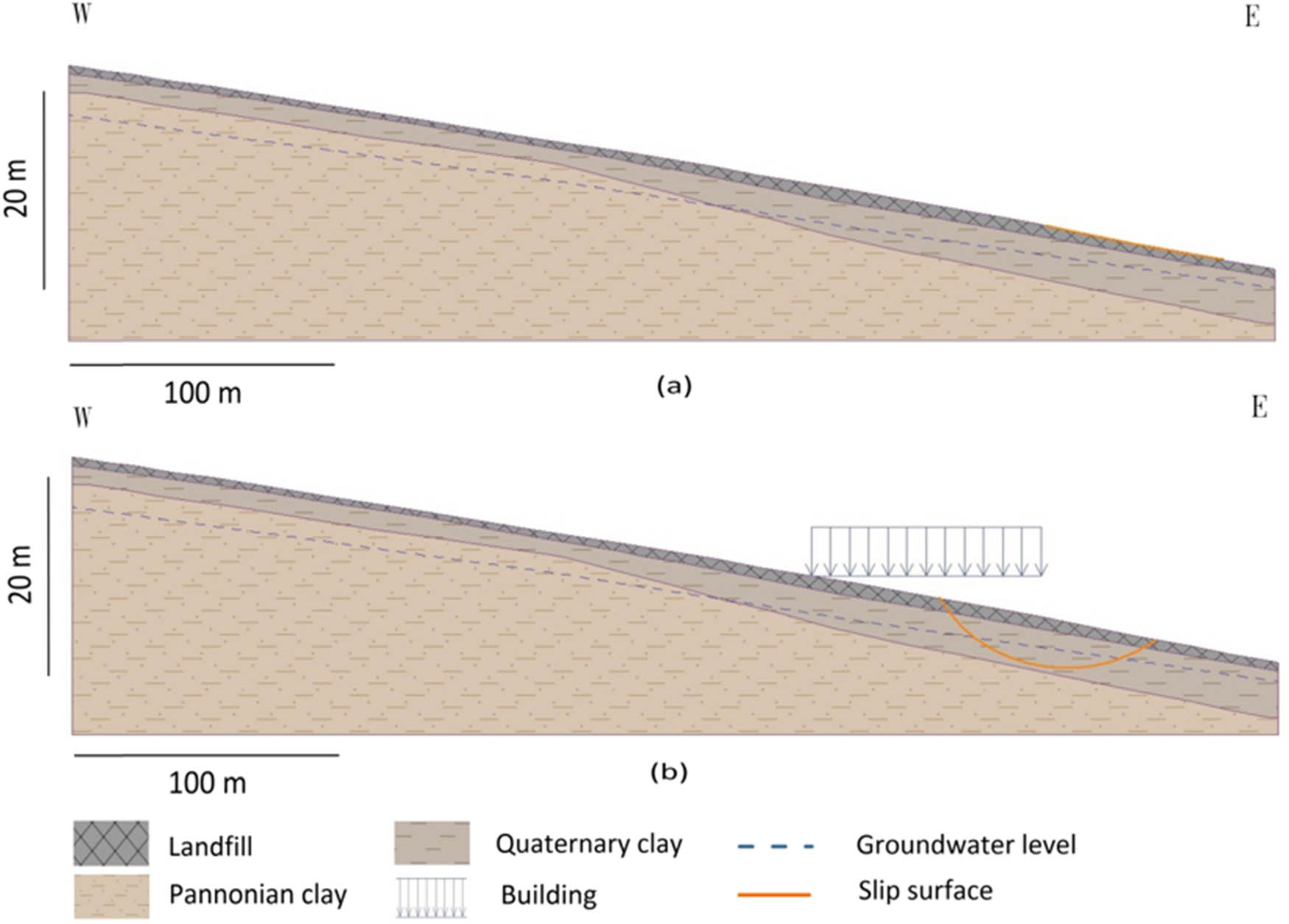

(a) Engineering geological modeling of the eastern side of Avas Hill. The red dashed lines indicate the erosive valleys, (b) a profile illustrates the cross-section of fifth line observation wells, and (c) a profile illustrates the cross-section of sixth line observation wells.

The modeling shows (Figure 11a) that the church is constructed in an erosive valley where erosion and weathering of soil take place. Subsequently, it is a disadvantage of engineering geology when the constructed buildings were established on the valley floor instead of the flat area. The thickness of the Quaternary clay layer varies in the two geological cross-sections ranging from 16.67–18.33 to 9.21–23.68 m toward the eastern direction of the fifth and sixth slopes, respectively (Figure 11b and c). The difference in the thickening of this layer between the two slopes (fifth and sixth) could reflect the variation in the topographic surface. The accumulated soil deposits on the downslope occurring as a result of soil movements can lead to the thickening of the Quaternary clay layer. In contrast, the erosion and weathering processes can lead to the thinning of this layer.

3.3 Evaluation of slope stability on a finite slope

3.3.1 Slope stability modeling

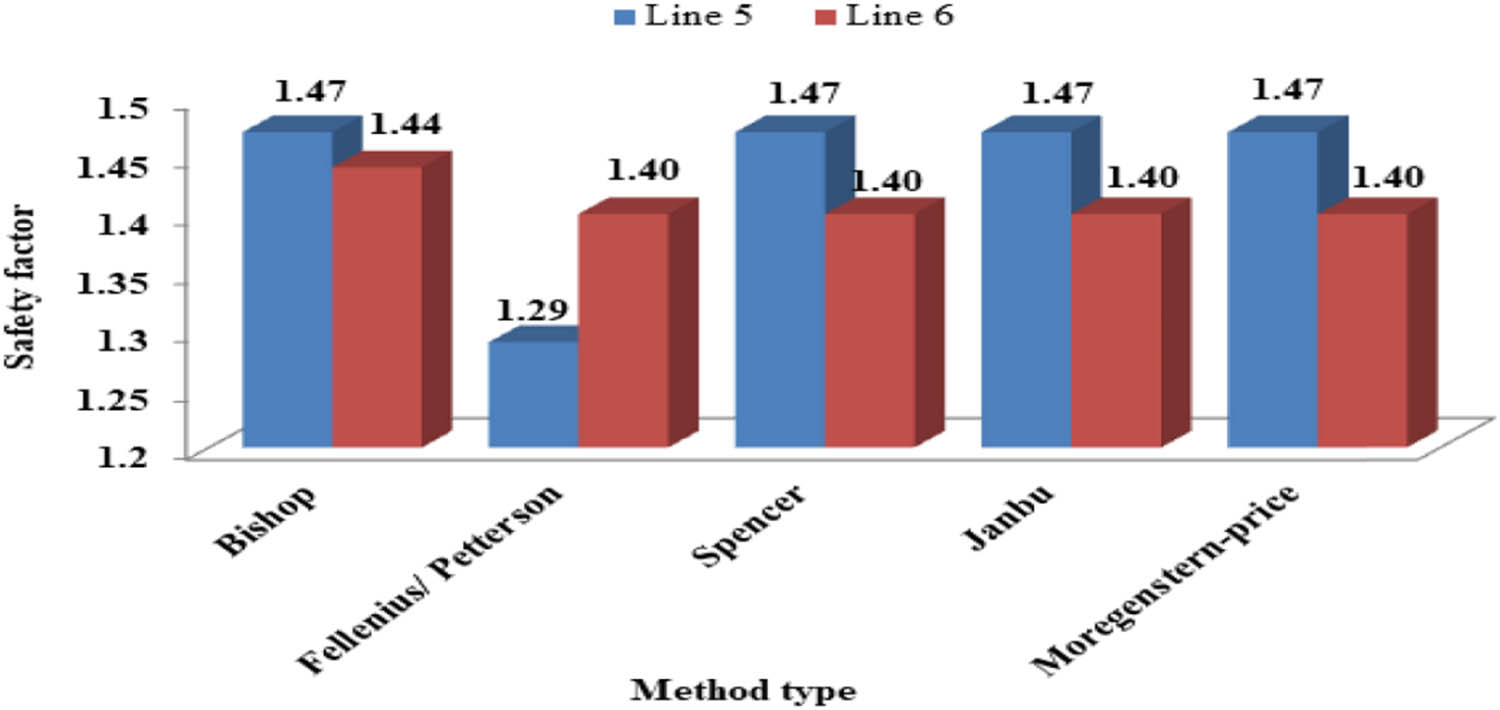

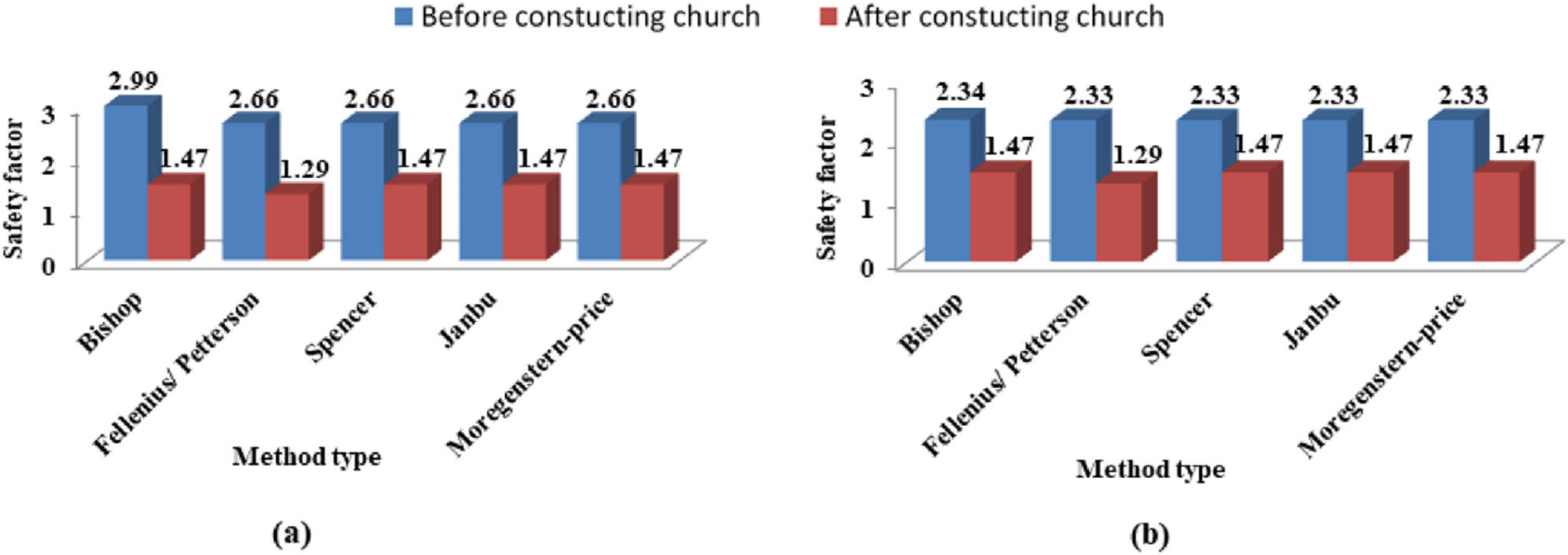

Based on the simulated results observed in Figure 12, the FS of the two slopes ranges between 1.29 and 1.47, and this range is less than 1.5 (the critical value of stable slope). So, these values indicate that the current states of the two slopes are unstable [70]. Moreover, the critical slip surface is observed within a shallow depth below the Quaternary clay deposits in the fifth and sixth lines of observation wells based on the Bishop Optimization method using the GEO5 program (Figure 13). It indicates that the layers of Quaternary clay and landfill and their overlaying building (church) are threatened by the sliding on the Pannonian surface.

FS of the observation wells on the fifth and sixth lines based on the limited equilibrium methods of slope stability.

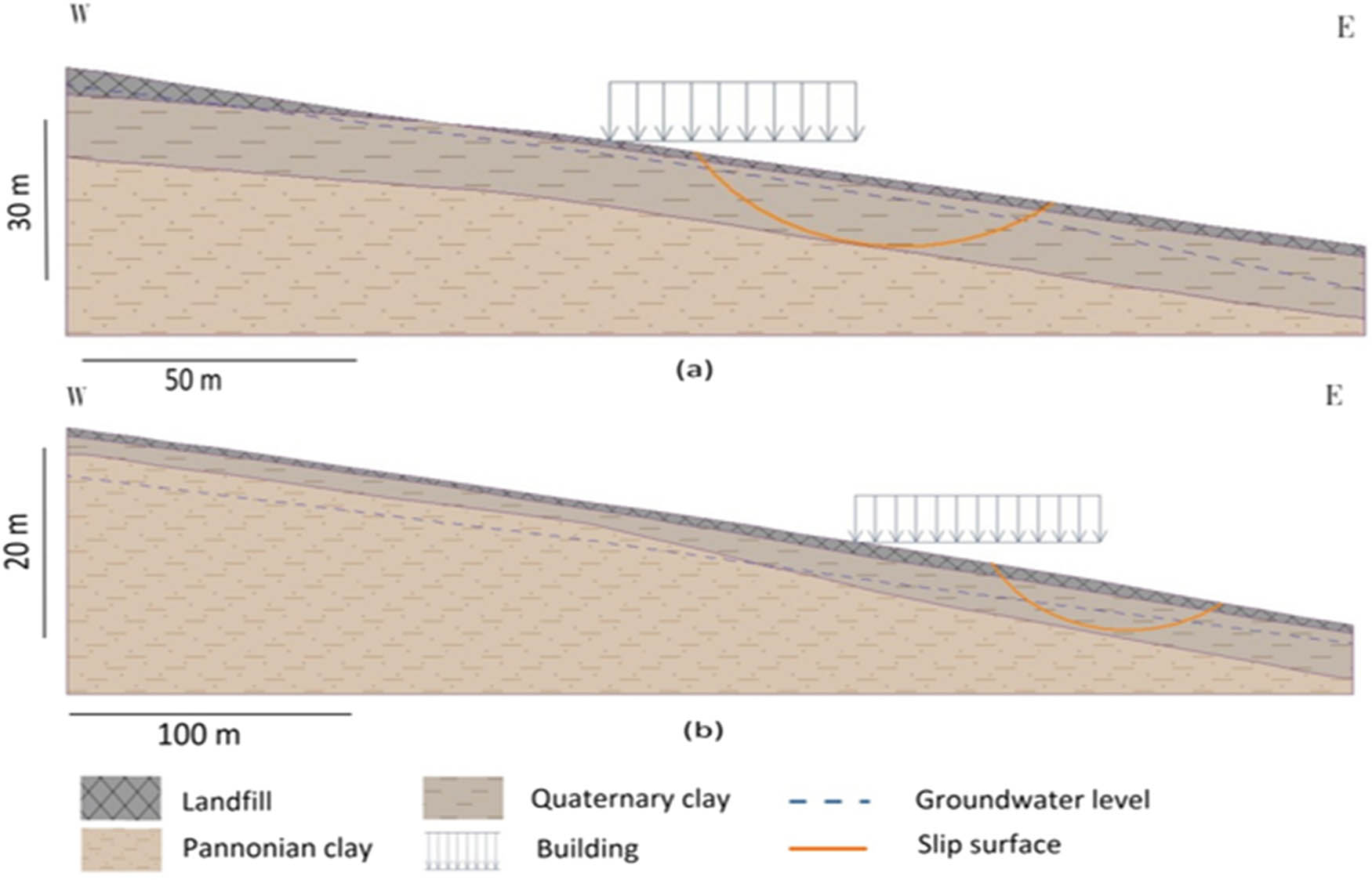

Analysis models illustrate the slope stability of (a) fifth observation wells and (b) sixth observation wells.

3.4 Influence of groundwater fluctuation on slope stability

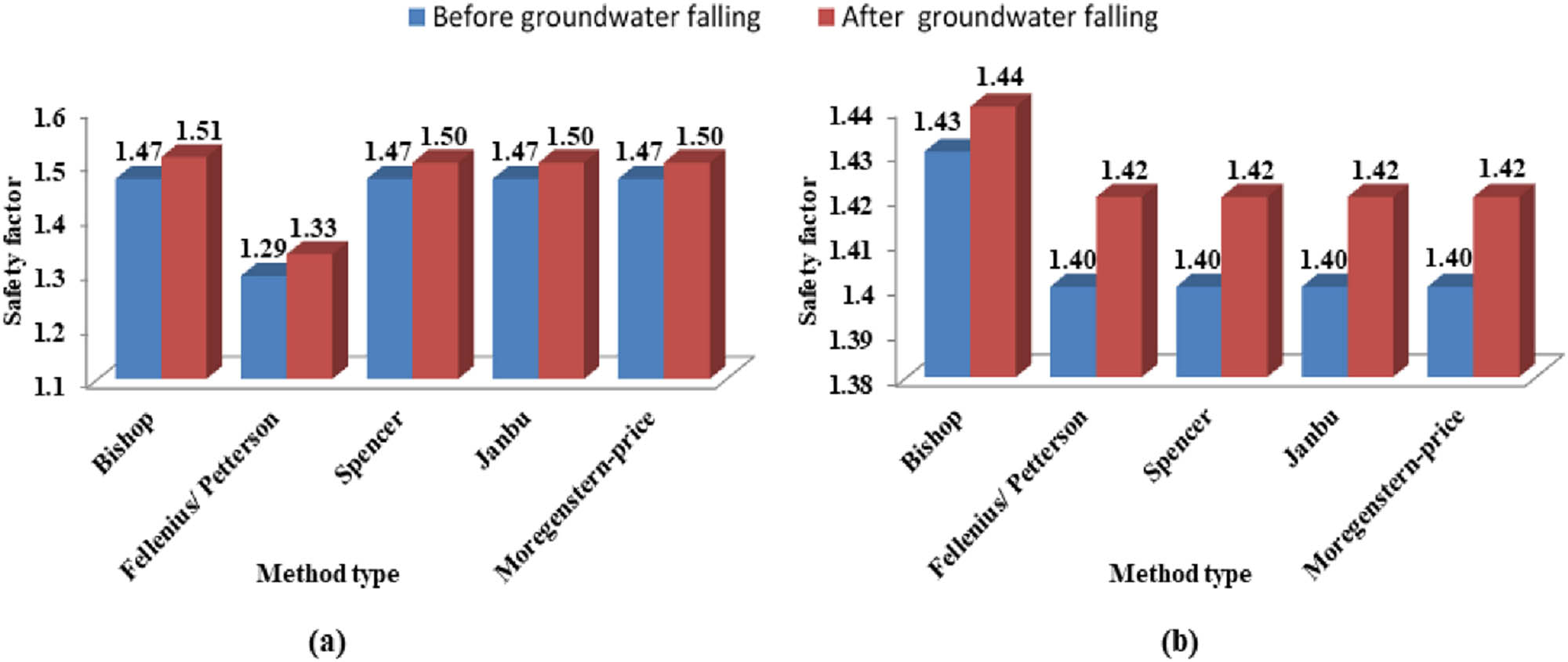

Based on the simulated results obtained from the GEO5 program (Figure 14), the groundwater level falls 40 cm in depth as shown in Figure 15. After that, the ranges of FS at the two lines of fifth and sixth observation wells increase from 1.29–1.47 to 1.33–1.51 (Figure 14). Consequently, the slope stability increases due to the reduction in the pore-water pressure and the rise in soil friction. Additionally, the uplift pressure induced by the confined water decreases under the sliding surface. Moreover, the lithology of the soil (Quaternary–Pannonian sequence) is composed of highly plastic clay minerals (i.e., montmorillonite). As commonly known, montmorillonite has a destructive drawback on slope stability due to its low shearing strength and high swelling ability [71,72]. Furthermore, groundwater fluctuation has a significant effect on the radius of the critical slip surfaces [73]. This can be observed from the radius critical slip surface at the fifth line observation wells when it decreases and moves from being tangential to the Quaternary–Pannonian interface to be within the Quaternary clay layer (Figure 15). This occurs when the groundwater level drops. Therefore, the volume of soil movements decreases on the slope (Figure 15).

The influence of groundwater fluctuation on slope stability based on limited equilibrium methods at (a) the fifth line observation wells and (b) the sixth line observation wells.

Analysis models illustrate the slope stability of the fifth line observation wells after the fall in the groundwater level from (a) to (b) by about 40 cm.

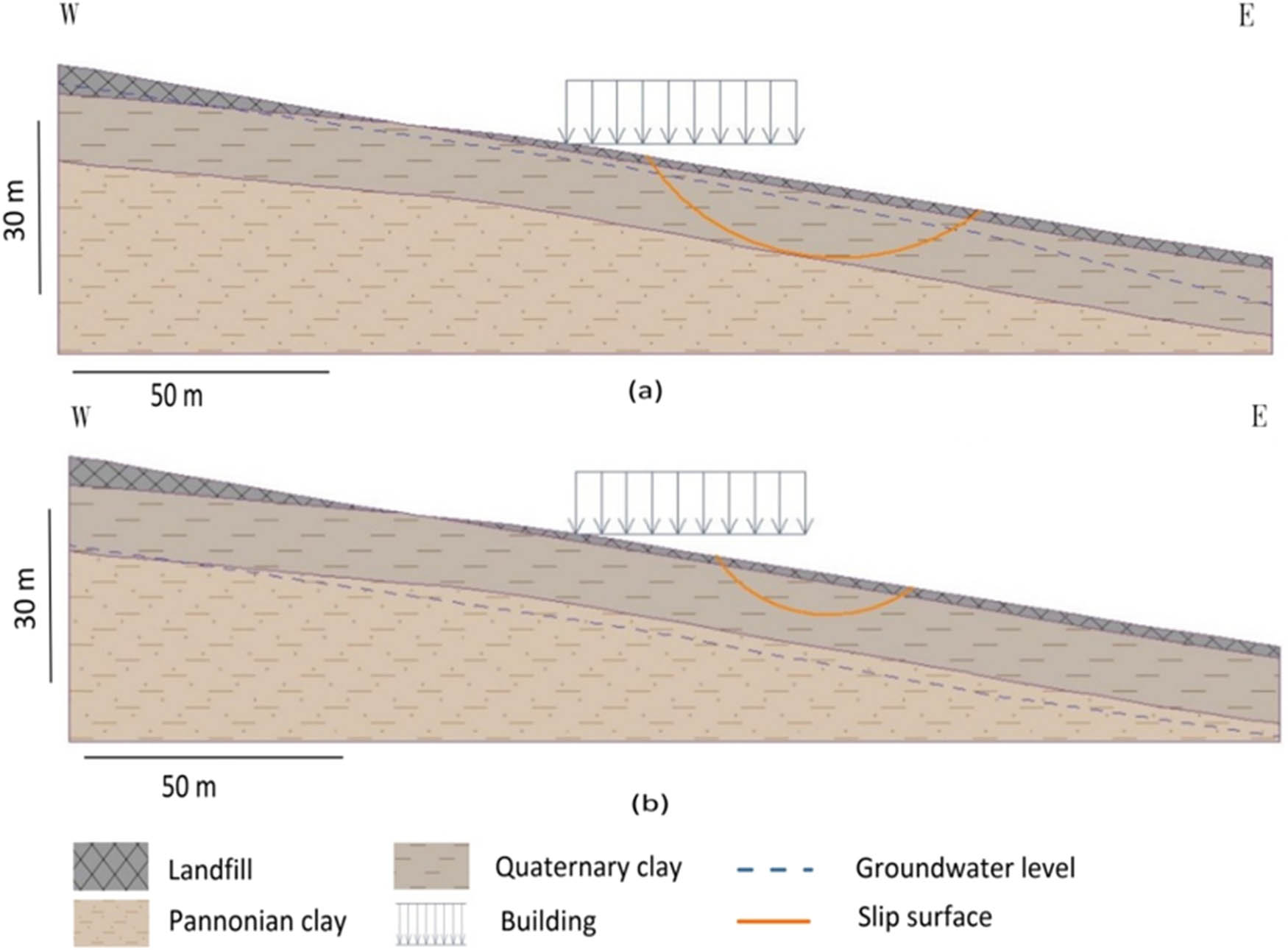

3.4.1 Influence of construction on slope

After applying different analytical methods (Figure 16), the results obtained from the fifth and sixth lines show that the slope became unstable after constructing the church, and that the the FS of the slope is less than 1.5. However, before constructing the church, the FS was higher than the value of the critical standard. Therefore, the church decreased the shear strength of the soil resulting in a negative impact on slope stability. Figure 17 illustrates that the critical slip surface was located near the ground surface at the landfill layer before constructing the church. However, it shifted deeper into the underground reaching the Quaternary–Pannonian boundary of the sixth line observation wells after construction of the church. As a result, the volume of soil movements increased after construction of the church compared to what it was before.

The influence of the construction on slope stability based on the limited equilibrium method at (a) the fifth line observation wells and (b) the sixth line observation wells.

Analysis models illustrate the slope stability of the sixth line observation wells: (a) before constructing the church and (b) after constructing the church.

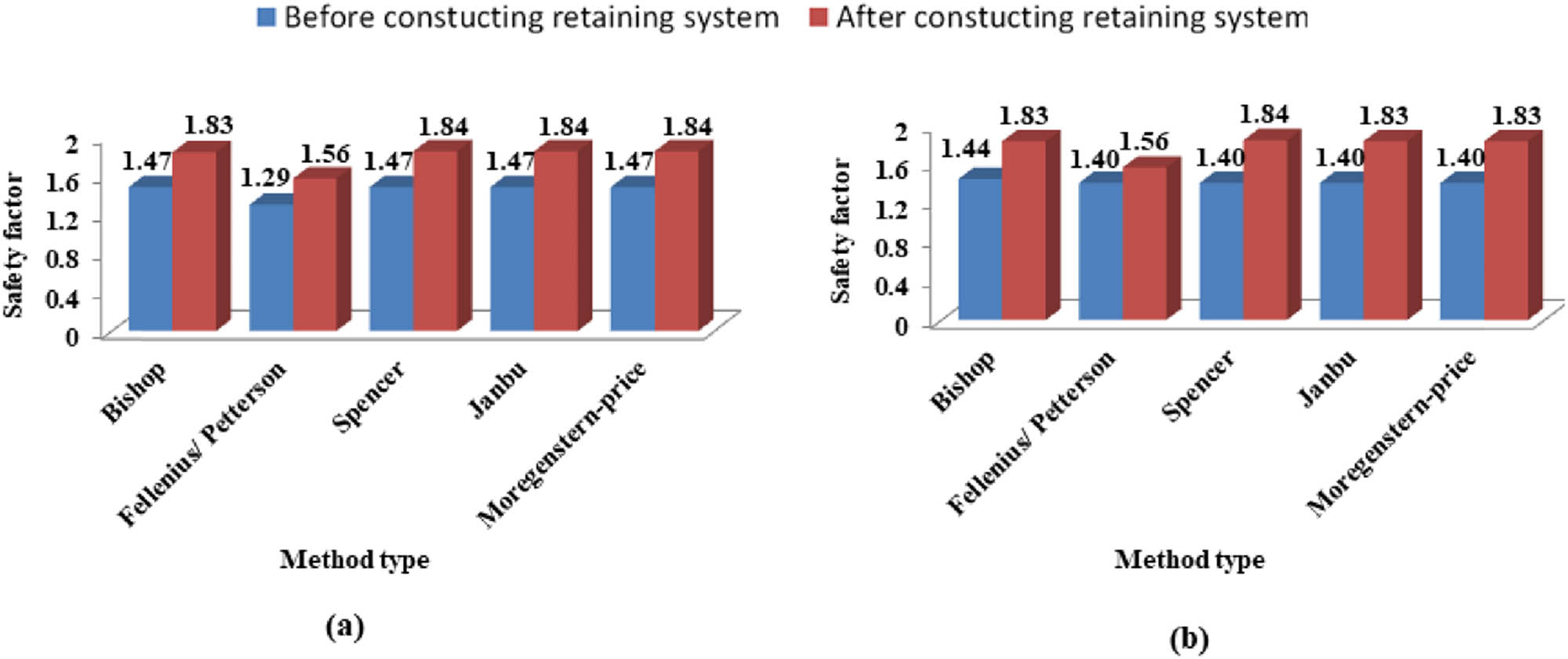

3.4.2 Influence of different retaining structures

The simulated results (Figure 18) show that the construction of a gravity retaining wall system has enhanced slope stability. This can be observed by the increasing FS at the fifth and sixth lines of observation wells from 1.29–1.47 to 1.56–1.84 after the construction of the retaining systems (Figure 18). Figure 19 illustrates that the analysis models of the fifth and sixth lines of observation wells have the same FS value, which is equal to 1.83 based on the Bishop Optimization method [50]. Moreover, the position of the critical slip surface has shifted from the lower to the upper part of the Quaternary clay layer reflecting the reduction in the volume of soil movements.

The influence of the gravity retaining wall system based on the limited equilibrium methods of slope stability on (a) the fifth line observation wells and (b) the sixth line observation wells.

Analysis models illustrate the slope stability after constructing the gravity retaining system of (a) the fifth line observation wells and (b) the sixth line observation wells.

4 Conclusion

Based on the experimental and simulated results, the following deductions can be drawn:

The soil movement is more influential on the first 5 m of the soil: the displacement rate is equal to 2 mm/year toward the NW–NE direction. After 5 m, the soil movements are inactive.

There is no relationship between rainfall and underground water level fluctuation due to the following reasons:

Natural aspects related to the underlying soil composed of impermeable clay and sandy clay.

Artificial aspects included leakage from the network pipeline, drainage network, construction pits, or construction of the deep foundation. Otherwise, the cracked asphaltic layer covering the roads contributes to surface water percolation (i.e., runoff, rainfall, the water of freeze-thaw, etc.) into the ground.

The safety factor of the study area is less than 1.5 indicating that the slope is rather unstable. Besides, the critical slip surfaces are optimized below the Quaternary clay layer. This will create a hazard for the church built above these deposits.

The fluctuations in groundwater levels have both deleterious and beneficial impacts on slope stability in the study area. The deleterious one is due to groundwater levels rising owing to the pore-water pressure released in the soil and the swelling property of the montmorillonite composing the soil. The beneficial one is the decrease in soil movements due to falling groundwater levels.

The recently built structures have a pernicious effect on slope stability when it is constructed on the middle slope. These structures are susceptible to soil movements at any time. So, it is not recommended to build any structures on the slope except at the summit of the slope (i.e., the plateau area).

Based on the simulated results of slope models, the recently built structures can be supported against the soil movements on the slope by constructing retaining wall systems such as gravity retaining walls.

Acknowledgment

The authors are very grateful to Prof. György Less, Institute of Mineralogy and Geology, University of Miskolc, Hungary, for help in the field as well as Miss Udomp P. Udomp, Mr Arbi Ben Aoun and Mr Alaa E. Abbadi, Institute of Environmental Management, University of Miskolc, Hungary, for help in the software analysis. The authors are also grateful to the Embassy of the Arab Republic of Egypt and Egypt’s Office for Cultural and Educational Relations, Vienna.

-

Author contributions: E.H. and T.K. designed and led the study. E.H. and M.A.M. wrote the manuscript of this work. T.K., E.H., A.T., and M.A.M. analyzed the data of the article. A.T. helped and contributed to the fieldwork. All authors contributed to the writing and gave final approval of this paper

-

Conflict of interest: The author has not declared any conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Kjekstad O, Highland L. Economic and social impacts of landslides. Landslides–disaster risk reduction. Berlin: Springer; 2009. p. 573–87.10.1007/978-3-540-69970-5_30Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Chae B-G, Park H-J, Catani F, Simoni A, Berti M. Landslide prediction, monitoring and early warning: a concise review of state-of-the-art. Geosci J. 2017;21:1033–70.10.1007/s12303-017-0034-4Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Hansen M. Strategies for classification of landslides. Slope instability. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1984. p. 1–25.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Yin K, Chen L, Zhang G. Regional landslide hazard warning and risk assessment. Earth Sci Front. 2007;14:85–93.10.1016/S1872-5791(08)60005-6Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Brönnimann CS. Effect of groundwater on landslide triggering: école polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. Switzerland: EPFL; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Mori A, Subramanian SS, Ishikawa T, Komatsu M. A case study of a cut slope failure influenced by snowmelt and rainfall. Proc Eng. 2017;189:533–8.10.1016/j.proeng.2017.05.085Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Hong Y, Hiura H, Shino K, Sassa K, Suemine A, Fukuoka H, et al. The influence of intense rainfall on the activity of large-scale crystalline schist landslides in Shikoku Island, Japan. Landslides. 2005;2:97–105.10.1007/s10346-004-0043-zSuche in Google Scholar

[8] Zhao Y, Li Y, Zhang L, Wang Q. Groundwater level prediction of landslide based on classification and regression tree. Geod Geodyn. 2016;7:348–55.10.1016/j.geog.2016.07.005Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Xiong X, Shi Z, Xiong Y, Peng M, Ma X, Zhang F. Unsaturated slope stability around the Three Gorges Reservoir under various combinations of rainfall and water level fluctuation. Eng Geol. 2019;261:105231.10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105231Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Wei Z-l, Lü Q, Sun H-Y, Shang Y-Q. Estimating the rainfall threshold of a deep-seated landslide by integrating models for predicting the groundwater level and stability analysis of the slope. Eng Geol. 2019;253:14–26.10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.02.026Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Troncone A, Pugliese L, Conte E. Run-out simulation of a landslide triggered by an increase in the groundwater level using the material point method. Water. 2020;12:2817.10.3390/w12102817Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Jones S, Kasthurba AK, Bhagyanathan A, Binoy BV. Impact of anthropogenic activities on landslide occurrences in southwest India: an investigation using spatial models. J Earth Syst Sci. 2021;130:70.10.1007/s12040-021-01566-6Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Pande A, Joshi RC, Jalal DS. Selected landslide types in the Central Himalaya: their relation to geological structure and anthropogenic activities. Environmentalist. 2002;22:269–87.10.1023/A:1016536013793Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Kokutse NK, Temgoua AGT, Kavazović Z. Slope stability and vegetation: Conceptual and numerical investigation of mechanical effects. Ecol Eng. 2016;86:146–53.10.1016/j.ecoleng.2015.11.005Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Emadi-Tafti M, Ataie-Ashtiani B, Hosseini SM. Integrated impacts of vegetation and soil type on slope stability: A case study of Kheyrud Forest, Iran. Ecol Model. 2021;446:109498.10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2021.109498Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Eab KH, Likitlersuang S, Takahashi A. Laboratory and modeling investigation of root-reinforced system for slope stabilisation. Soils Found. 2015;55:1270–81.10.1016/j.sandf.2015.09.025Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Nguyen TS, Likitlersuang S, Jotisankasa A. Stability analysis of vegetated residual soil slope in Thailand under rainfall conditions. Env Geotech. 2020;7:338–49.10.1680/jenge.17.00025Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Likitlersuang S, Takahashi A, Eab KH. Modeling of root-reinforced soil slope under rainfall condition. Eng J. 2017;21:123–32.10.4186/ej.2017.21.3.123Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Fondjo AA, Theron E, Ray RP. Stabilization of expansive soils using mechanical and chemical methods: a comprehensive review. Civ Eng Archit. 2021;9:1295–308.10.13189/cea.2021.090503Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Zu R, Khalid U, Farooq K, Mujtaba H. On yield stress of compacted clays. Int J Geotech Eng. 2018;9:21.10.1186/s40703-018-0090-2Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Bakhshi Ardakani S, Rajabi AM. Laboratory investigation of clayey soils improvement using sepiolite as an additive; engineering performances and micro-scale analysis. Eng Geol. 2021;293:106328.10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106328Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Rajabi AM, Ardakani SB. Effects of natural-zeolite additive on mechanical and physicochemical properties of clayey soils. J Mater Civ Eng. 2020;32:04020306.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003336Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Khodaparast M, Rajabi AM, Mohammadi M. Mechanical properties of silty clay soil treated with a mixture of lime and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Constr Build Mater. 2021;281:122548.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122548Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Ngo TP, Likitlersuang S, Takahashi A. Performance of a geosynthetic cementitious composite mat for stabilising sandy slopes. Geosynth Int. 2019;26:309–19.10.1680/jgein.19.00020Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Nguyen TS, Likitlersuang S, Jotisankasa A. Influence of the spatial variability of the root cohesion on a slope-scale stability model: a case study of residual soil slope in Thailand. Bull Eng Geol Env. 2019;78:3337–51.10.1007/s10064-018-1380-9Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Leknoi U, Likitlersuang S. Good practice and lesson learned in promoting vetiver as solution for slope stabilisation and erosion control in Thailand. Land Use Policy. 2020;99:105008.10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105008Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Likitlersuang S, Kounyou K, Prasetyaningtiyas GA. Performance of geosynthetic cementitious composite mat and vetiver on soil erosion control. J Mt Sci. 2020;17:1410–22.10.1007/s11629-019-5926-5Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Chen G, Jia J. Case study of slope stabilization using compression anchor and reinforced concrete beam. Boundaries of Rock Mechanics. London: CRC Press; 2008. p. 475–8.10.1201/9780203883204-93Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Jamsawang P, Voottipruex P, Jongpradist P, Likitlersuang S. Field and three-dimensional finite element investigations of the failure cause and rehabilitation of a composite soil-cement retaining wall. Eng Fail Anal. 2021;127:105532.10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105532Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Troncone A, Pugliese L, Lamanna G, Conte E. Prediction of rainfall-induced landslide movements in the presence of stabilizing piles. Eng Geol. 2021;288:106143.10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106143Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Wei Z-L, Wang D-F, Xu H-D, Sun H-Y. Clarifying the effectiveness of drainage tunnels in landslide controls based on high-frequency in-site monitoring. Bull Eng Geol Env. 2020;79:3289–305.10.1007/s10064-020-01769-zSuche in Google Scholar

[32] Ukritchon B, Chea S, Keawsawasvong S. Optimal design of Reinforced Concrete Cantilever Retaining Walls considering the requirement of slope stability. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2017;21:2673–82.10.1007/s12205-017-1627-1Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Kotiukov P, Lange IY. Engineering Geological Analysis of the Landslide Causes During the Construction of Industrial Building. Int J Civ Eng Technol. 2019;10:1471–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Szabó J. The relationship between landslide activity and weather: examples from Hungary. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci. 2003;3:43–52.10.5194/nhess-3-43-2003Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Mocsár-Vámos M, Görög P, Török Á. Engineering geological characterization of the host rocks of underground cellars in Avas hill, Northern Hungary. Geotech Eng Infrastruct Dev. 2015;2287–92.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Ringer Á, Miskolci Avas A. A felszínfejlődés fő kérdései (The Avas Hill in Mis-kolc. Basic Questions of the landscape evolution). In Miskolci Avas A, editor. A Miskolci Her-man Ottó Múzeum és a Borsodi Ny közös kiadványa Miskolc. 1933;49–53.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Schréter Z. A miskolci Avas pincebeomlásai (Collapses of vine cellars on the Avas Hill, Miskolc). MÁFI Évi Jel. 1940;35:1741–54.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Mocsár-Vámos M, Görög P, Borostyáni M, Vásárhelyi B, Török Á. Stability analysis of wine cellars cut into volcanic tuffs in Northern Hungary. In: Lollino G, Giordan D, Marunteanu C, Christaras B, Yoshinori I, Margottini C, editors. Engineering geology for society and territory. Vol. 8. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 153–7.10.1007/978-3-319-09408-3_24Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Vámos M, Görög P, Vásárhelyi B. Landside problem and its investigations in Miskolc (Hungary). In: Lollino G, Manconi A, Guzzetti F, Culshaw M, Bobrowsky P, Luino F, editors. Engineering geology for society and territory. Vol. 5, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 873–7.10.1007/978-3-319-09048-1_170Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Papp K. Miskolcz környékének geológiai viszonyai (Geology of Miskolc). A Magy Királyi Földtani Intézet Évkönyve. 1907;16:91–132.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Hajdúné K. Az Avas geológiai felépítése (Geology of the Avas). In: Miskolci Avas A, Herman A, editors. Ottó Múzeum és a Borsodi Nyomda közös kiadványaOttó Múzeum és a Borsodi Nyomda közös kiadványa. Miskolc; 1993. p. 49–53.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Hartai E, Szakáll S. Geological and mineralogical background of the Palaeolithic chert mining on the Avas Hill, Miskolc, Hungary. Praehistoria. 2005;6:15–21.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Nguyen TS, Likitlersuang S, Ohtsu H, Kitaoka T. Influence of the spatial variability of shear strength parameters on rainfall induced landslides: a case study of sandstone slope in Japan. Arab J Geosci. 2017;10:369.10.1007/s12517-017-3158-ySuche in Google Scholar

[44] Fekete Z, Kántor T, Tóth M. Slope observation network of eastern Avas in Mis-kolc. XV-KMKTK-Poszter: Institute of Environmental Management, University of Miskolc, Hungary IH-3515 Miskolc-Egyetemváros; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Mohamed E, Tamas K. Geotechnical investigations: a case study of Avas hill, Miskolc, Northeast of Hungary. A Miskolci Egyetem, Műszaki Földtudományi Közlemények. 2020;2020(89):336–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Terzaghi K, Peck RB. Soil mechanics in engineering practice. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1967.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Canadian Geotechnical Society. Foundation engineering manual. Vancouver, Canada: BiTech Publishers Ltd; 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Labuz JF, Zang A. Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. In: Ulusay R, editor. The ISRM suggested methods for rock characterization, testing and monitoring: 2007–2014. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. p. 227–31.10.1007/978-3-319-07713-0_19Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Fellenius W. Erdstatische Berechnungen mit Reibung und Kohäsion (Adhäsion) und unter Annahme kreiszylindrischer Gleitflächen. Berlin, Germany: W. Ernst & Sohn; 1927.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Bishop AW. The use of the slip circle in the stability analysis of slopes. Geotechnique. 1955;5:7–17.10.1680/geot.1955.5.1.7Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Spencer E. A method of analysis of the stability of embankments assuming parallel inter-slice forces. Geotechnique. 1967;17:11–26.10.1680/geot.1967.17.1.11Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Janbu N. Slope stability computations. The embankment dam engineering. Casagrande volume, Editors Hirschfeld and Poulos. New York: John Wiley & Sons inc.; 1973. p. 47–86Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Morgenstern N, Price V. A numerical method for solving the equations of stability of general slip surfaces. Comput J. 1967;9:388–93.10.1093/comjnl/9.4.388Suche in Google Scholar

[54] Crozier M. Field assessment of slope instability. In: Brunsden D, Prior D, editors. Slope instability. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 1984. p. 103–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[55] Zakaria Z, Sophian I, Sabila Z, Jihadi L. Slope safety factor and its relationship with angle of slope gradient to support landslide mitigation at jatinangor education area, Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth Environ Sci. Indonesia: IOP Publishing; 2018. p. 012052.10.1088/1755-1315/145/1/012052Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Frank R. Designers’ guide to EN 1997-1 Eurocode 7: Geotechnical design-General rules. London: Thomas Telford; 2004.10.1680/dgte7.31548Suche in Google Scholar

[57] AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications. Washington, D.C., USA: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Das BM. Principles of geotechnical engineering. India: Thomson Learning; 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Hadzinakos I, Yannacopoulos D, Faltsetas C, Ziourkas K. Application of the Minora decision support system to the evaluation of landslide favourability in Greece. Eur J Oper Res. 1991;50:61–75.10.1016/0377-2217(91)90039-XSuche in Google Scholar

[60] Lollino G, Arattano M, Cuccureddu M. The use of the automatic inclinometric system for landslide early warning: the case of Cabella Ligure (North-Western Italy). Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C. 2002;27:1545–50.10.1016/S1474-7065(02)00175-4Suche in Google Scholar

[61] Zayed AM, Masoud MA, Shahien MG, et al. Physical, mechanical, and radiation attenuation properties of serpentine concrete containing boric acid. Constr Build Mater. 2021;272:121641.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121641Suche in Google Scholar

[62] Masoud MA, El-Khayatt AM, Kansouh WA, Sakr K, Shahien MG, Zayed AM. Insights into the effect of the mineralogical composition of serpentine aggregates on the radiation attenuation properties of their concretes. Constr Build Mater. 2020;263:120141.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120141Suche in Google Scholar

[63] Zayed AM, Masoud MA, Rashad AM, et al. Influence of heavyweight aggregates on the physico-mechanical and radiation attenuation properties of serpentine-based concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2020;260:120473.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120473Suche in Google Scholar

[64] Masoud MA, Kansouh WA, Shahien MG, Sakr K, Rashad AM, Zayed AM. An experimental investigation on the effects of barite/hematite on the radiation shielding properties of serpentine concretes. Prog Nucl Energy. 2020;120:103220.10.1016/j.pnucene.2019.103220Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Hossain KA, Gencturk B. Life-cycle environmental impact assessment of reinforced concrete buildings subjected to natural hazards. J Archit Eng. 2016;22:A4014001.10.1061/(ASCE)AE.1943-5568.0000153Suche in Google Scholar

[66] Hodge RA, Freeze RA. Groundwater flow systems and slope stability. Can Geotech J. 1977;14:466–76.10.1139/t77-049Suche in Google Scholar

[67] Keqiang H, Zhiliang W, Xiaoyun M, Zengtao L. Research on the displacement response ratio of groundwater dynamic augment and its application in evaluation of the slope stability. Env Earth Sci. 2015;74:5773–91.10.1007/s12665-015-4595-0Suche in Google Scholar

[68] Nguyen TS, Likitlersuang S. Reliability analysis of unsaturated soil slope stability under infiltration considering hydraulic and shear strength parameters. Bull Eng Geol Env. 2019;78:5727–43.10.1007/s10064-019-01513-2Suche in Google Scholar

[69] Eab KH, Takahashi A, Likitlersuang S. Centrifuge modeling of root-reinforced soil slope subjected to rainfall infiltration. Geotech Lett. 2014;4:211–6.10.1680/geolett.14.00029Suche in Google Scholar

[70] Bowles JE. Physical and geotechnical properties of soils. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1979.Suche in Google Scholar

[71] Yalcin A. The effects of clay on landslides: a case study. Appl Clay Sci. 2007;38:77–85.10.1016/j.clay.2007.01.007Suche in Google Scholar

[72] Iqbal J, Dai F, Hong M, Tu X, Xie Q. Failure mechanism and stability analysis of an active landslide in the Xiangjiaba Reservoir Area, Southwest China. J Earth Sci. 2018;29:646–61.10.1007/s12583-017-0753-5Suche in Google Scholar

[73] Binet S, Jomard H, Lebourg T, Guglielmi Y, Tric E, Bertrand C, et al. Experimental analysis of groundwater flow through a landslide slip surface using natural and artificial water chemical tracers. Hydrol Process. 2007;21:3463–72.10.1002/hyp.6579Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Eslam M. Hemid et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Lithopetrographic and geochemical features of the Saalian tills in the Szczerców outcrop (Poland) in various deformation settings

- Spatiotemporal change of land use for deceased in Beijing since the mid-twentieth century

- Geomorphological immaturity as a factor conditioning the dynamics of channel processes in Rządza River

- Modeling of dense well block point bar architecture based on geological vector information: A case study of the third member of Quantou Formation in Songliao Basin

- Predicting the gas resource potential in reservoir C-sand interval of Lower Goru Formation, Middle Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Study on the viscoelastic–viscoplastic model of layered siltstone using creep test and RBF neural network

- Assessment of Chlorophyll-a concentration from Sentinel-3 satellite images at the Mediterranean Sea using CMEMS open source in situ data

- Spatiotemporal evolution of single sandbodies controlled by allocyclicity and autocyclicity in the shallow-water braided river delta front of an open lacustrine basin

- Research and application of seismic porosity inversion method for carbonate reservoir based on Gassmann’s equation

- Impulse noise treatment in magnetotelluric inversion

- Application of multivariate regression on magnetic data to determine further drilling site for iron exploration

- Comparative application of photogrammetry, handmapping and android smartphone for geotechnical mapping and slope stability analysis

- Geochemistry of the black rock series of lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, SW Yangtze Block, China: Reconstruction of sedimentary and tectonic environments

- The timing of Barleik Formation and its implication for the Devonian tectonic evolution of Western Junggar, NW China

- Risk assessment of geological disasters in Nyingchi, Tibet

- Effect of microbial combination with organic fertilizer on Elymus dahuricus

- An OGC web service geospatial data semantic similarity model for improving geospatial service discovery

- Subsurface structure investigation of the United Arab Emirates using gravity data

- Shallow geophysical and hydrological investigations to identify groundwater contamination in Wadi Bani Malik dam area Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- Consideration of hyperspectral data in intraspecific variation (spectrotaxonomy) in Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC, Saudi Arabia

- Characteristics and evaluation of the Upper Paleozoic source rocks in the Southern North China Basin

- Geospatial assessment of wetland soils for rice production in Ajibode using geospatial techniques

- Input/output inconsistencies of daily evapotranspiration conducted empirically using remote sensing data in arid environments

- Geotechnical profiling of a surface mine waste dump using 2D Wenner–Schlumberger configuration

- Forest cover assessment using remote-sensing techniques in Crete Island, Greece

- Stability of an abandoned siderite mine: A case study in northern Spain

- Assessment of the SWAT model in simulating watersheds in arid regions: Case study of the Yarmouk River Basin (Jordan)

- The spatial distribution characteristics of Nb–Ta of mafic rocks in subduction zones

- Comparison of hydrological model ensemble forecasting based on multiple members and ensemble methods

- Extraction of fractional vegetation cover in arid desert area based on Chinese GF-6 satellite

- Detection and modeling of soil salinity variations in arid lands using remote sensing data

- Monitoring and simulating the distribution of phytoplankton in constructed wetlands based on SPOT 6 images

- Is there an equality in the spatial distribution of urban vitality: A case study of Wuhan in China

- Considering the geological significance in data preprocessing and improving the prediction accuracy of hot springs by deep learning

- Comparing LiDAR and SfM digital surface models for three land cover types

- East Asian monsoon during the past 10,000 years recorded by grain size of Yangtze River delta

- Influence of diagenetic features on petrophysical properties of fine-grained rocks of Oligocene strata in the Lower Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Impact of wall movements on the location of passive Earth thrust

- Ecological risk assessment of toxic metal pollution in the industrial zone on the northern slope of the East Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, NW China

- Seasonal color matching method of ornamental plants in urban landscape construction

- Influence of interbedded rock association and fracture characteristics on gas accumulation in the lower Silurian Shiniulan formation, Northern Guizhou Province

- Spatiotemporal variation in groundwater level within the Manas River Basin, Northwest China: Relative impacts of natural and human factors

- GIS and geographical analysis of the main harbors in the world

- Laboratory test and numerical simulation of composite geomembrane leakage in plain reservoir

- Structural deformation characteristics of the Lower Yangtze area in South China and its structural physical simulation experiments

- Analysis on vegetation cover changes and the driving factors in the mid-lower reaches of Hanjiang River Basin between 2001 and 2015

- Extraction of road boundary from MLS data using laser scanner ground trajectory

- Research on the improvement of single tree segmentation algorithm based on airborne LiDAR point cloud

- Research on the conservation and sustainable development strategies of modern historical heritage in the Dabie Mountains based on GIS

- Cenozoic paleostress field of tectonic evolution in Qaidam Basin, northern Tibet

- Sedimentary facies, stratigraphy, and depositional environments of the Ecca Group, Karoo Supergroup in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa

- Water deep mapping from HJ-1B satellite data by a deep network model in the sea area of Pearl River Estuary, China

- Identifying the density of grassland fire points with kernel density estimation based on spatial distribution characteristics

- A machine learning-driven stochastic simulation of underground sulfide distribution with multiple constraints

- Origin of the low-medium temperature hot springs around Nanjing, China

- LCBRG: A lane-level road cluster mining algorithm with bidirectional region growing

- Constructing 3D geological models based on large-scale geological maps

- Crops planting structure and karst rocky desertification analysis by Sentinel-1 data

- Physical, geochemical, and clay mineralogical properties of unstable soil slopes in the Cameron Highlands

- Estimation of total groundwater reserves and delineation of weathered/fault zones for aquifer potential: A case study from the Federal District of Brazil

- Characteristic and paleoenvironment significance of microbially induced sedimentary structures (MISS) in terrestrial facies across P-T boundary in Western Henan Province, North China

- Experimental study on the behavior of MSE wall having full-height rigid facing and segmental panel-type wall facing

- Prediction of total landslide volume in watershed scale under rainfall events using a probability model

- Toward rainfall prediction by machine learning in Perfume River Basin, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- A PLSR model to predict soil salinity using Sentinel-2 MSI data

- Compressive strength and thermal properties of sand–bentonite mixture

- Age of the lower Cambrian Vanadium deposit, East Guizhou, South China: Evidences from age of tuff and carbon isotope analysis along the Bagong section

- Identification and logging evaluation of poor reservoirs in X Oilfield

- Geothermal resource potential assessment of Erdaobaihe, Changbaishan volcanic field: Constraints from geophysics

- Geochemical and petrographic characteristics of sediments along the transboundary (Kenya–Tanzania) Umba River as indicators of provenance and weathering

- Production of a homogeneous seismic catalog based on machine learning for northeast Egypt

- Analysis of transport path and source distribution of winter air pollution in Shenyang

- Triaxial creep tests of glacitectonically disturbed stiff clay – structural, strength, and slope stability aspects

- Effect of groundwater fluctuation, construction, and retaining system on slope stability of Avas Hill in Hungary

- Spatial modeling of ground subsidence susceptibility along Al-Shamal train pathway in Saudi Arabia

- Pore throat characteristics of tight reservoirs by a combined mercury method: A case study of the member 2 of Xujiahe Formation in Yingshan gasfield, North Sichuan Basin

- Geochemistry of the mudrocks and sandstones from the Bredasdorp Basin, offshore South Africa: Implications for tectonic provenance and paleoweathering

- Apriori association rule and K-means clustering algorithms for interpretation of pre-event landslide areas and landslide inventory mapping

- Lithology classification of volcanic rocks based on conventional logging data of machine learning: A case study of the eastern depression of Liaohe oil field

- Sequence stratigraphy and coal accumulation model of the Taiyuan Formation in the Tashan Mine, Datong Basin, China

- Influence of thick soft superficial layers of seabed on ground motion and its treatment suggestions for site response analysis

- Monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of surface water body of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir using Landsat-5/7/8 imagery and Google Earth Engine

- Research on the traditional zoning, evolution, and integrated conservation of village cultural landscapes based on “production-living-ecology spaces” – A case study of villages in Meicheng, Guangdong, China

- A prediction method for water enrichment in aquifer based on GIS and coupled AHP–entropy model

- Earthflow reactivation assessment by multichannel analysis of surface waves and electrical resistivity tomography: A case study

- Geologic structures associated with gold mineralization in the Kirk Range area in Southern Malawi

- Research on the impact of expressway on its peripheral land use in Hunan Province, China

- Concentrations of heavy metals in PM2.5 and health risk assessment around Chinese New Year in Dalian, China

- Origin of carbonate cements in deep sandstone reservoirs and its significance for hydrocarbon indication: A case of Shahejie Formation in Dongying Sag

- Coupling the K-nearest neighbors and locally weighted linear regression with ensemble Kalman filter for data-driven data assimilation

- Multihazard susceptibility assessment: A case study – Municipality of Štrpce (Southern Serbia)

- A full-view scenario model for urban waterlogging response in a big data environment

- Elemental geochemistry of the Middle Jurassic shales in the northern Qaidam Basin, northwestern China: Constraints for tectonics and paleoclimate

- Geometric similarity of the twin collapsed glaciers in the west Tibet

- Improved gas sand facies classification and enhanced reservoir description based on calibrated rock physics modelling: A case study

- Utilization of dolerite waste powder for improving geotechnical parameters of compacted clay soil

- Geochemical characterization of the source rock intervals, Beni-Suef Basin, West Nile Valley, Egypt

- Satellite-based evaluation of temporal change in cultivated land in Southern Punjab (Multan region) through dynamics of vegetation and land surface temperature

- Ground motion of the Ms7.0 Jiuzhaigou earthquake

- Shale types and sedimentary environments of the Upper Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Member 1 of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in western Hubei Province, China

- An era of Sentinels in flood management: Potential of Sentinel-1, -2, and -3 satellites for effective flood management

- Water quality assessment and spatial–temporal variation analysis in Erhai lake, southwest China

- Dynamic analysis of particulate pollution in haze in Harbin city, Northeast China

- Comparison of statistical and analytical hierarchy process methods on flood susceptibility mapping: In a case study of the Lake Tana sub-basin in northwestern Ethiopia

- Performance comparison of the wavenumber and spatial domain techniques for mapping basement reliefs from gravity data

- Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological environment quality in arid areas based on the remote sensing ecological distance index: A case study of Yuyang district in Yulin city, China

- Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of the Mengjiaping beschtauite in the southern Taihang mountains

- Review Articles

- The significance of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis on the microstructure of improved clay: An overview

- A review of some nonexplosive alternative methods to conventional rock blasting

- Retrieval of digital elevation models from Sentinel-1 radar data – open applications, techniques, and limitations

- A review of genetic classification and characteristics of soil cracks

- Potential CO2 forcing and Asian summer monsoon precipitation trends during the last 2,000 years

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Calibration of the depth invariant algorithm to monitor the tidal action of Rabigh City at the Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia”

- Rapid Communication

- Individual tree detection using UAV-lidar and UAV-SfM data: A tutorial for beginners

- Technical Note

- Construction and application of the 3D geo-hazard monitoring and early warning platform

- Enhancing the success of new dams implantation under semi-arid climate, based on a multicriteria analysis approach: Case of Marrakech region (Central Morocco)

- TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CULTURAL LANDSCAPES - Koper 2019

- The “changing actor” and the transformation of landscapes

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Lithopetrographic and geochemical features of the Saalian tills in the Szczerców outcrop (Poland) in various deformation settings

- Spatiotemporal change of land use for deceased in Beijing since the mid-twentieth century

- Geomorphological immaturity as a factor conditioning the dynamics of channel processes in Rządza River

- Modeling of dense well block point bar architecture based on geological vector information: A case study of the third member of Quantou Formation in Songliao Basin

- Predicting the gas resource potential in reservoir C-sand interval of Lower Goru Formation, Middle Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Study on the viscoelastic–viscoplastic model of layered siltstone using creep test and RBF neural network

- Assessment of Chlorophyll-a concentration from Sentinel-3 satellite images at the Mediterranean Sea using CMEMS open source in situ data

- Spatiotemporal evolution of single sandbodies controlled by allocyclicity and autocyclicity in the shallow-water braided river delta front of an open lacustrine basin

- Research and application of seismic porosity inversion method for carbonate reservoir based on Gassmann’s equation

- Impulse noise treatment in magnetotelluric inversion

- Application of multivariate regression on magnetic data to determine further drilling site for iron exploration

- Comparative application of photogrammetry, handmapping and android smartphone for geotechnical mapping and slope stability analysis

- Geochemistry of the black rock series of lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, SW Yangtze Block, China: Reconstruction of sedimentary and tectonic environments

- The timing of Barleik Formation and its implication for the Devonian tectonic evolution of Western Junggar, NW China

- Risk assessment of geological disasters in Nyingchi, Tibet

- Effect of microbial combination with organic fertilizer on Elymus dahuricus

- An OGC web service geospatial data semantic similarity model for improving geospatial service discovery

- Subsurface structure investigation of the United Arab Emirates using gravity data

- Shallow geophysical and hydrological investigations to identify groundwater contamination in Wadi Bani Malik dam area Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- Consideration of hyperspectral data in intraspecific variation (spectrotaxonomy) in Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC, Saudi Arabia

- Characteristics and evaluation of the Upper Paleozoic source rocks in the Southern North China Basin

- Geospatial assessment of wetland soils for rice production in Ajibode using geospatial techniques

- Input/output inconsistencies of daily evapotranspiration conducted empirically using remote sensing data in arid environments

- Geotechnical profiling of a surface mine waste dump using 2D Wenner–Schlumberger configuration

- Forest cover assessment using remote-sensing techniques in Crete Island, Greece

- Stability of an abandoned siderite mine: A case study in northern Spain

- Assessment of the SWAT model in simulating watersheds in arid regions: Case study of the Yarmouk River Basin (Jordan)

- The spatial distribution characteristics of Nb–Ta of mafic rocks in subduction zones

- Comparison of hydrological model ensemble forecasting based on multiple members and ensemble methods

- Extraction of fractional vegetation cover in arid desert area based on Chinese GF-6 satellite

- Detection and modeling of soil salinity variations in arid lands using remote sensing data

- Monitoring and simulating the distribution of phytoplankton in constructed wetlands based on SPOT 6 images

- Is there an equality in the spatial distribution of urban vitality: A case study of Wuhan in China

- Considering the geological significance in data preprocessing and improving the prediction accuracy of hot springs by deep learning

- Comparing LiDAR and SfM digital surface models for three land cover types

- East Asian monsoon during the past 10,000 years recorded by grain size of Yangtze River delta

- Influence of diagenetic features on petrophysical properties of fine-grained rocks of Oligocene strata in the Lower Indus Basin, Pakistan

- Impact of wall movements on the location of passive Earth thrust

- Ecological risk assessment of toxic metal pollution in the industrial zone on the northern slope of the East Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang, NW China

- Seasonal color matching method of ornamental plants in urban landscape construction

- Influence of interbedded rock association and fracture characteristics on gas accumulation in the lower Silurian Shiniulan formation, Northern Guizhou Province

- Spatiotemporal variation in groundwater level within the Manas River Basin, Northwest China: Relative impacts of natural and human factors

- GIS and geographical analysis of the main harbors in the world

- Laboratory test and numerical simulation of composite geomembrane leakage in plain reservoir

- Structural deformation characteristics of the Lower Yangtze area in South China and its structural physical simulation experiments

- Analysis on vegetation cover changes and the driving factors in the mid-lower reaches of Hanjiang River Basin between 2001 and 2015

- Extraction of road boundary from MLS data using laser scanner ground trajectory

- Research on the improvement of single tree segmentation algorithm based on airborne LiDAR point cloud

- Research on the conservation and sustainable development strategies of modern historical heritage in the Dabie Mountains based on GIS

- Cenozoic paleostress field of tectonic evolution in Qaidam Basin, northern Tibet

- Sedimentary facies, stratigraphy, and depositional environments of the Ecca Group, Karoo Supergroup in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa

- Water deep mapping from HJ-1B satellite data by a deep network model in the sea area of Pearl River Estuary, China

- Identifying the density of grassland fire points with kernel density estimation based on spatial distribution characteristics

- A machine learning-driven stochastic simulation of underground sulfide distribution with multiple constraints

- Origin of the low-medium temperature hot springs around Nanjing, China

- LCBRG: A lane-level road cluster mining algorithm with bidirectional region growing

- Constructing 3D geological models based on large-scale geological maps

- Crops planting structure and karst rocky desertification analysis by Sentinel-1 data

- Physical, geochemical, and clay mineralogical properties of unstable soil slopes in the Cameron Highlands

- Estimation of total groundwater reserves and delineation of weathered/fault zones for aquifer potential: A case study from the Federal District of Brazil

- Characteristic and paleoenvironment significance of microbially induced sedimentary structures (MISS) in terrestrial facies across P-T boundary in Western Henan Province, North China

- Experimental study on the behavior of MSE wall having full-height rigid facing and segmental panel-type wall facing

- Prediction of total landslide volume in watershed scale under rainfall events using a probability model

- Toward rainfall prediction by machine learning in Perfume River Basin, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam

- A PLSR model to predict soil salinity using Sentinel-2 MSI data

- Compressive strength and thermal properties of sand–bentonite mixture

- Age of the lower Cambrian Vanadium deposit, East Guizhou, South China: Evidences from age of tuff and carbon isotope analysis along the Bagong section

- Identification and logging evaluation of poor reservoirs in X Oilfield

- Geothermal resource potential assessment of Erdaobaihe, Changbaishan volcanic field: Constraints from geophysics

- Geochemical and petrographic characteristics of sediments along the transboundary (Kenya–Tanzania) Umba River as indicators of provenance and weathering

- Production of a homogeneous seismic catalog based on machine learning for northeast Egypt

- Analysis of transport path and source distribution of winter air pollution in Shenyang

- Triaxial creep tests of glacitectonically disturbed stiff clay – structural, strength, and slope stability aspects

- Effect of groundwater fluctuation, construction, and retaining system on slope stability of Avas Hill in Hungary

- Spatial modeling of ground subsidence susceptibility along Al-Shamal train pathway in Saudi Arabia

- Pore throat characteristics of tight reservoirs by a combined mercury method: A case study of the member 2 of Xujiahe Formation in Yingshan gasfield, North Sichuan Basin

- Geochemistry of the mudrocks and sandstones from the Bredasdorp Basin, offshore South Africa: Implications for tectonic provenance and paleoweathering

- Apriori association rule and K-means clustering algorithms for interpretation of pre-event landslide areas and landslide inventory mapping

- Lithology classification of volcanic rocks based on conventional logging data of machine learning: A case study of the eastern depression of Liaohe oil field

- Sequence stratigraphy and coal accumulation model of the Taiyuan Formation in the Tashan Mine, Datong Basin, China

- Influence of thick soft superficial layers of seabed on ground motion and its treatment suggestions for site response analysis

- Monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of surface water body of the Xiaolangdi Reservoir using Landsat-5/7/8 imagery and Google Earth Engine

- Research on the traditional zoning, evolution, and integrated conservation of village cultural landscapes based on “production-living-ecology spaces” – A case study of villages in Meicheng, Guangdong, China

- A prediction method for water enrichment in aquifer based on GIS and coupled AHP–entropy model

- Earthflow reactivation assessment by multichannel analysis of surface waves and electrical resistivity tomography: A case study

- Geologic structures associated with gold mineralization in the Kirk Range area in Southern Malawi

- Research on the impact of expressway on its peripheral land use in Hunan Province, China

- Concentrations of heavy metals in PM2.5 and health risk assessment around Chinese New Year in Dalian, China

- Origin of carbonate cements in deep sandstone reservoirs and its significance for hydrocarbon indication: A case of Shahejie Formation in Dongying Sag

- Coupling the K-nearest neighbors and locally weighted linear regression with ensemble Kalman filter for data-driven data assimilation

- Multihazard susceptibility assessment: A case study – Municipality of Štrpce (Southern Serbia)

- A full-view scenario model for urban waterlogging response in a big data environment

- Elemental geochemistry of the Middle Jurassic shales in the northern Qaidam Basin, northwestern China: Constraints for tectonics and paleoclimate

- Geometric similarity of the twin collapsed glaciers in the west Tibet

- Improved gas sand facies classification and enhanced reservoir description based on calibrated rock physics modelling: A case study

- Utilization of dolerite waste powder for improving geotechnical parameters of compacted clay soil

- Geochemical characterization of the source rock intervals, Beni-Suef Basin, West Nile Valley, Egypt

- Satellite-based evaluation of temporal change in cultivated land in Southern Punjab (Multan region) through dynamics of vegetation and land surface temperature

- Ground motion of the Ms7.0 Jiuzhaigou earthquake

- Shale types and sedimentary environments of the Upper Ordovician Wufeng Formation-Member 1 of the Lower Silurian Longmaxi Formation in western Hubei Province, China

- An era of Sentinels in flood management: Potential of Sentinel-1, -2, and -3 satellites for effective flood management

- Water quality assessment and spatial–temporal variation analysis in Erhai lake, southwest China

- Dynamic analysis of particulate pollution in haze in Harbin city, Northeast China

- Comparison of statistical and analytical hierarchy process methods on flood susceptibility mapping: In a case study of the Lake Tana sub-basin in northwestern Ethiopia

- Performance comparison of the wavenumber and spatial domain techniques for mapping basement reliefs from gravity data

- Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological environment quality in arid areas based on the remote sensing ecological distance index: A case study of Yuyang district in Yulin city, China

- Petrogenesis and tectonic significance of the Mengjiaping beschtauite in the southern Taihang mountains

- Review Articles

- The significance of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis on the microstructure of improved clay: An overview

- A review of some nonexplosive alternative methods to conventional rock blasting

- Retrieval of digital elevation models from Sentinel-1 radar data – open applications, techniques, and limitations

- A review of genetic classification and characteristics of soil cracks

- Potential CO2 forcing and Asian summer monsoon precipitation trends during the last 2,000 years

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Calibration of the depth invariant algorithm to monitor the tidal action of Rabigh City at the Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia”

- Rapid Communication

- Individual tree detection using UAV-lidar and UAV-SfM data: A tutorial for beginners

- Technical Note

- Construction and application of the 3D geo-hazard monitoring and early warning platform

- Enhancing the success of new dams implantation under semi-arid climate, based on a multicriteria analysis approach: Case of Marrakech region (Central Morocco)

- TRANSFORMATION OF TRADITIONAL CULTURAL LANDSCAPES - Koper 2019

- The “changing actor” and the transformation of landscapes

![Figure 2