Abstract

Demand-side management (DSM) with Internet of Things (IoT) integration has become a vital path for optimizing photovoltaic (PV) power generating systems. This systematic review synthesizes and evaluates the latest advancements in IoT-based DSM strategies applied to PV power generation. The review encompasses a comprehensive analysis of recent literature, focusing on the key elements of IoT implementation, data analytics, communication protocols, and control strategies in relation to solar energy DSM. The combined results show how IoT-driven solutions are changing and how they might improve PV power systems’ sustainability, dependability, and efficiency. The review also identifies gaps in current research and proposes potential avenues for future investigations, thereby contributing to the ongoing discourse on leveraging smart DSM in the solar energy domain using IoT technology.

1 Introduction

As global energy demand continues to rise, effective energy utilization has become paramount. Demand-side management (DSM) is a key component of the smart grid, offering methods to modify long-term power consumption patterns (Ahmad et al. 2022). DSM strategies focus on enhancing energy efficiency, reducing costs, and minimizing waste by redistributing energy consumption from peak to off-peak hours. Smart grids employ DSM operations to manage end-user load profiles for efficient power utilization (Ahmadi et al. 2020). Traditional grids face challenges integrating DSM, renewable energy sources (RERs), and emerging technologies. Smart grids address these issues by incorporating energy storage technologies, smart meters, and distributed generation to meet future power requirements (Alkhatib et al. 2021). Smart grid technology facilitates interaction among utilities, consumers, and control centers, allowing electricity providers to optimize energy use patterns through proper DSM implementation (Aguilar et al. 2020). The coordination between utilities, demand response aggregators, and customers is structured in a three-layer model for day-ahead DSM, aiming to maximize providers’ profit, minimize operating costs, and maximize net benefits (Agyemang et al. 2021).

To optimize energy consumption, a multi-objective problem is formulated and solved using an artificial immune algorithm, ensuring that the objectives of utilities, consumers, and demand response aggregators are met (Aliero et al. 2022). Additionally, a clustering study and particle swarm optimization K-means approach are employed to identify energy use trends and propose a suitable model for DSM. In a liberalized energy market, inter-supplier cooperation mechanisms among DSM users within low voltage (LV) networks are proposed (Baidya et al. 2021). A decentralized optimization algorithm defines energy consumption schedules for flexible appliances, ensuring fair cost distribution after establishing Nash equilibrium (Baneshi et al. 2020). For the purpose of monitoring shifts in consumer preferences and energy costs, a completely distributed and independent DSM architecture is used, resulting in a more dependable and effective system (Bashir et al. 2021).

For industrial loads, DSM programming demonstrates improvements in load factor, peak demand reduction, and end-user savings (Benavente-Peces 2019). The study suggests the use of dynamic thermal rating (DTR) systems and DSM methodologies to overcome challenges posed by rising energy demand (Bhat et al. 2020). Reliability of the transmission network is the primary focus in examining various DSM approaches and their interaction with the DTR system (Chen et al. 2020). The efficacy of DSM is contingent on comprehensive data on consumer consumption. Utilities can gather consumption data to create customized DSM programs with the use of advanced metering infrastructure (Daissaoui et al. 2020). However, challenges related to smart meter data quantity in DSM and load forecasting systems are addressed to deliver more accurate and straightforward load profiles (Dave et al. 2020).

Earlier DSM systems overlooked the statuses of other distribution network components by treating each element as a hierarchical actor (Dharmadhikari et al. 2021). A combined intention protocol is proposed to facilitate information exchange among hierarchical levels, emphasizing the development of effective communication protocols for energy control (Divina et al. 2019). A multi-time scale DSM scheduling system is presented, considering week-ahead and day-ahead scheduling, incorporating dynamic scenario-building strategies to address load unpredictability (Dong et al. 2019). In autonomous DSM, customer participation is crucial for convergence, with a gradual convergence rate aiming to lower system costs for a significant number of users (Dos Santos et al. 2021) (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of current and existing research

| Sl. No. | Author | Scope of the article | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Khedkar et al. (2021) | Applications for Internet of Things (IoT) and associated issues that need to be resolved. The issues displayed in the lesson are not in the domain | IoT applications have discussed their reliance on the year’s largest number of citations. Other important references relating to all IoT applications have been included because of their excellent contributions to the field of research |

| 2 | Karim et al. (2020) | IoT technology applications include issues with communication networks and privacy | Communication technology, comparative research detection of communication data technology utilized in an assortment of IoT applications, as well as future techniques and areas for improvement |

| 3 | Jiang et al. (2019) | Different factors necessary to make IoT communication possible. IoT applications’ Cloud server synchronization with IoT problem | IoT is made possible by communication devices and their appraisal based on a variety of factors. On the other hand, the Researcher who saw on the start of the simulation or a synchronized, specific location of trial and error |

| 4 | Divina et al. (2019) | Various IoT applications have been available throughout history. Challenges faced during the implementation of multiple IoT projects | Advanced technology was employed to overcome the difficulty and possibility of modernization and enhancement in the future idea and opportunity of the day |

| 5 | Jakkala et al. (2020) | Predicted application domains for IoT components include the utilization of sensors and actuators. | Highlights of the proposed research include: IoT applications and components |

| 6 | Hassan et al. (2021) | IoT-supporting architectures, IoT communication technologies | Depending on how they are used in the IoT, sensors and actuators are categorized. Time series aided in the development of newer and newer values for the IoT technology for communication |

| 7 | Haider et al. (2021) | Architecture, protocols and elements used, communication standards and challenge in IoT | Specific IoT objectives are classified based on an architecture that can be generated or industrial recognition and custom of IoT elements. The issue’s IoT challenge and the technique utilized to resolve it |

| 8 | Gomez-Quiles and Valdivieso-Sarabia (2019) | IoT challenges | Various IoT applications at the core of a variety of parameters challenge in IoT |

| 9 | Ghorbanian et al. (2021) | IoT advancement for waste management is an issue in IoT | Every possible application in the smart city area is covered by IoT methods and implementations. IoT Challenges |

| 10 | Farzaneh et al. (2021) | IoT middleware problems and issues encountered while using middleware | An in-depth look at the IoT in the present day |

| 11 | Eisen and Ribeiro (2020) | For secure communication, different symmetric and asymmetric cyphers are used | Distinct aspects and challenges encountered when using technology for communication |

| 12 | Eini et al. (2021) | Real-time IoT analytics methodologies need handling challenges with real-time analytics during real-time data collecting | Problems encountered during the performance data in real time. The article discusses how to discover advanced RT/SB approaches to use in various applications. The challenges have been highlighted, and the research is not simply limited to IoT real-time analytics |

| 13 | Dong et al. (2019) | Smart switches that actively monitor each load’s energy use, available power, and other criteria in order to transition connecting RERs | Grid-based DRM systems and solar power are synchronized |

| 14 | Dave et al. (2020) | With the use of several settings, including those involving the customer console and precedence factors, the data are gathered; IoT integration is also being developed for user tracking | In the energy sector, the digital world through IoT surroundings has thus achieved many advances in terms of dependable data collecting, remote monitoring, and control |

| 15 | Chen et al. (2020) | The IoT is gaining traction thanks to internet-connected items (IoT). It was a decentralized network made up of scalable, lightweight, low-power nodes | Energy harvesting and subsystems for IoT networks have been developed to address the challenge of delivering energy consistently and reliably. To achieve this, issues related to IoT energy harvesters must be addressed. Evaluation of various harvesting systems and distribution methodologies has been conducted to identify potential solutions |

| 16 | Rao et al. (2022) | An electronic module known as a sensor detects the system’s characteristics and transmits the information to the control station | In addition to implementing voltage and current sensors in real-time, this article discusses the properties of sensors and how they are used at different phases of the solar energy generating system |

| 17 | Bashir et al. (2021) | Smart socket for collecting and transferring data from nodes in the field to nodes in another field | The data are analyzed by the system, which then generates control commands to switch on or off the devices connected with the smart plug |

The research content for DSM optimization solutions is presented in this article. Figure 1 is an illustration of the article’s organizational structure. Section 3 offers a succinct summary of DSM application in microgrids, whereas Section 2 explores the categorization of DSM techniques. Sections 4 and 5 examine how distributed energy resources (DERs), battery storage, RERs, and electric vehicles (EVs) are affected by DSM. An extensive summary of several optimization techniques for DSM implementation is provided in Section 6. Section 7 discusses research challenges and possible directions for further inquiry, while Section 8 concludes the survey (Figure 2).

The structure of the article (Ghorbanian et al. 2021).

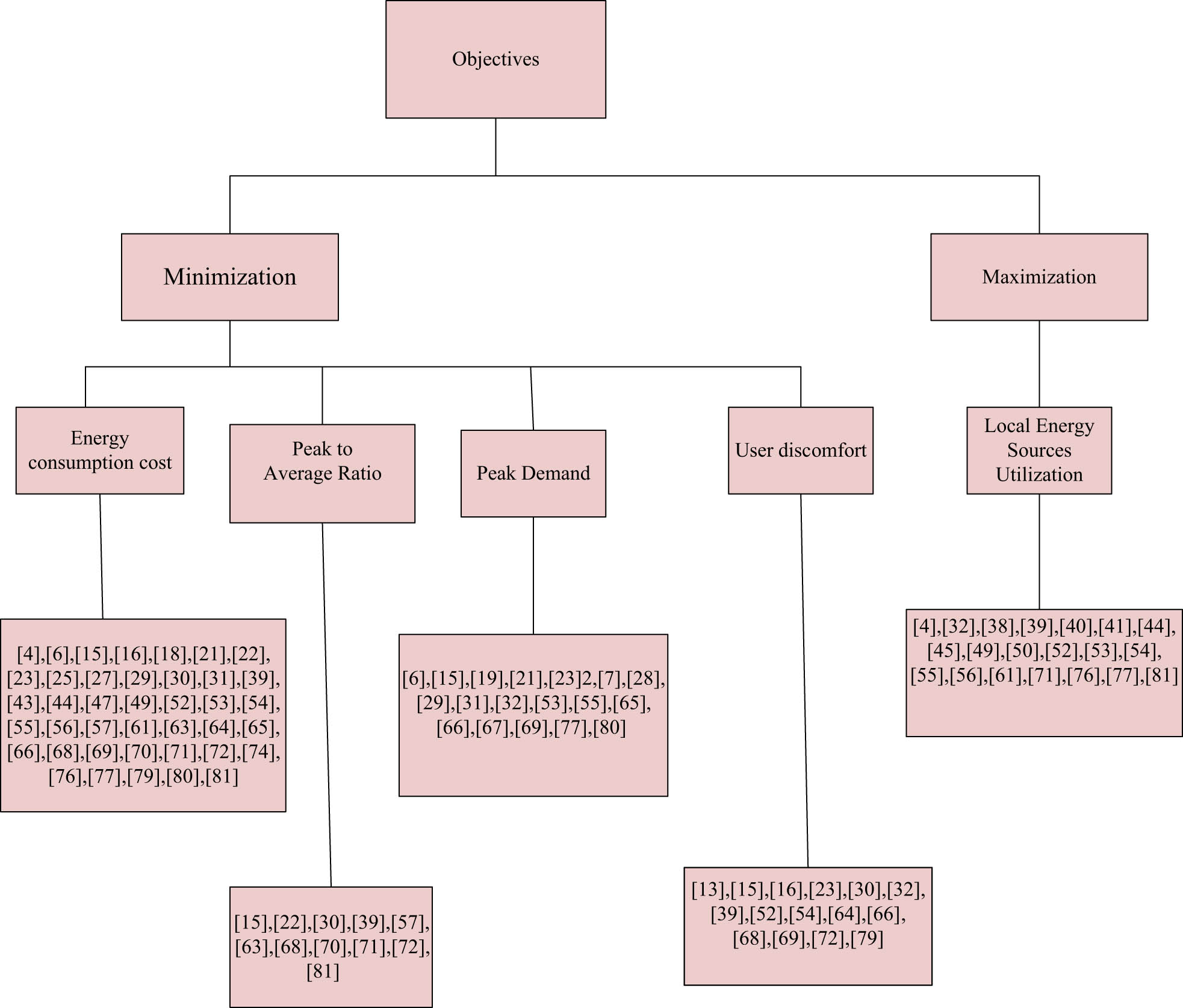

The optimization objectives in DSM (Khademi et al. 2021).

2 Classification of DSM methods

End users or utilities may implement DSM measures with utilities often utilizing favorable tariff incentives to encourage customers to alter their consumption patterns. By aligning demand activities with periods of lower power costs, users can reduce their energy expenses, and utilities benefit from reduced demand during peak times (Eisen and Ribeiro 2020). The categorization of DSM technique types includes Energy conservation techniques and strategies for load management (Eini et al. 2021). DSM techniques prioritize reducing energy costs, reducing peak demand, raising the peak-to-average ratio, and reducing user discomfort by encouraging local energy use and modifying user behavior (Farao et al. 2021). Primary goals of DSM encompass minimizing client discomfort, maximizing local energy production, lowering peak demand, maximizing the ratio of peak to average demand, and cutting down on power expenses (Farzaneh et al. 2021).

2.1 Energy conservation techniques

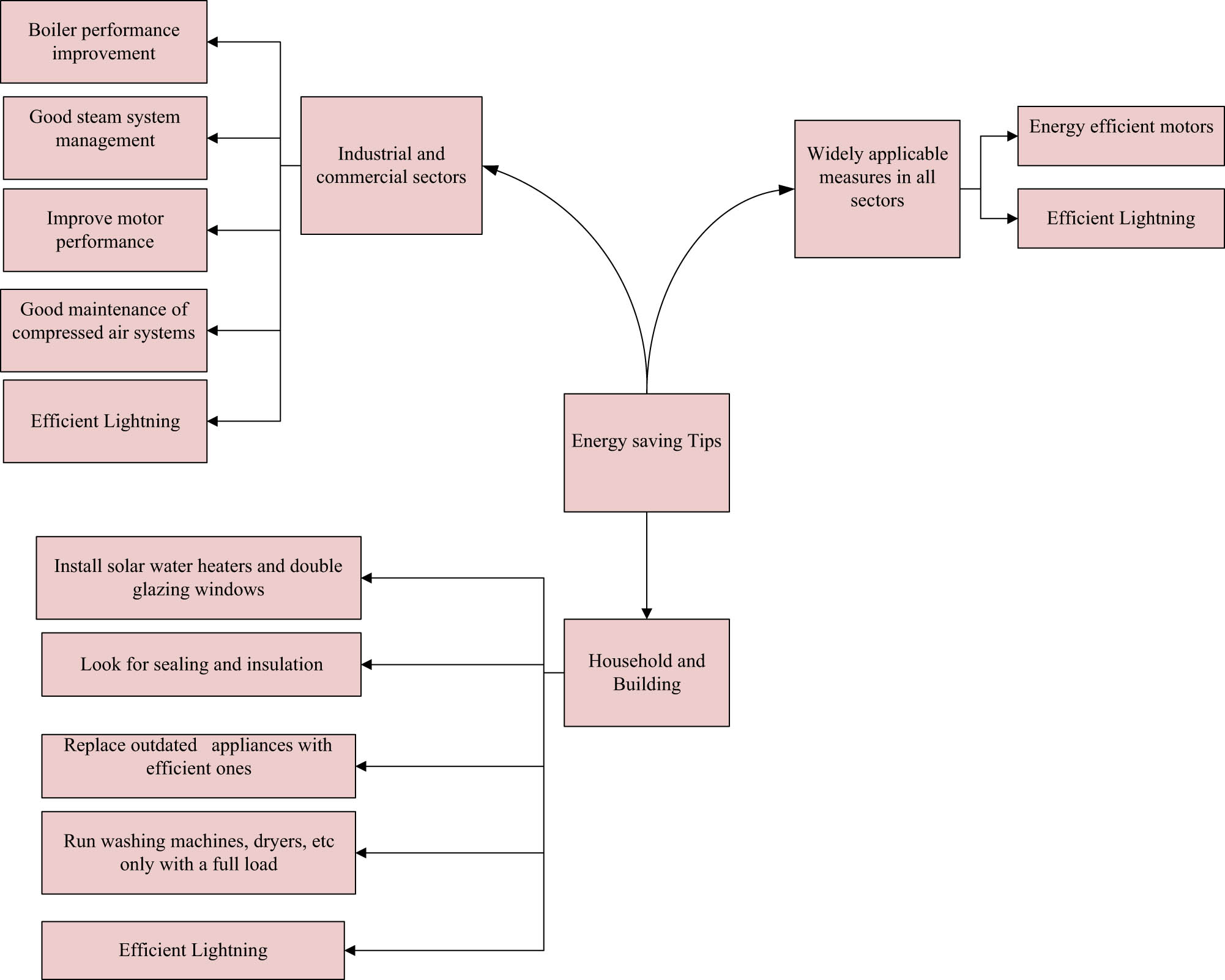

Figure 3 provides insights into energy conservation techniques. In a study focused on controlling non-flexible power demand in smart grids for academic buildings (Ghorbanian et al. 2021), an optimization technique employing Integer linear programming and a fuzzy controller was proposed. This method utilizes human-like reasoning to regulate non-flexible loads based on the convenience level of one appliance affecting others (Ghosh and Saha 2021). Maximizing non-flexible loads reduces overall power usage while maintaining user comfort. The intention is to reduce the equation for energy consumption in academic buildings.

where p i and c i stand for an appliance’s power consumption at any given moment and its level of convenience, respectively, in a set of appliances, i denotes a specific appliance, and s i denotes the switch control for that appliance (Gomez-Quiles and Valdivieso-Sarabia 2019).

The tips for conserving energy (Li et al. 2020).

The potential for energy-saving techniques as a DSM approach in economically disadvantaged nations is explored as a financially viable and successful option (Guo et al. 2020). The research indicates a substantial 50.7% reduction in energy demand when consumer behavior, contributing to decreased energy consumption, is integrated as a demand response strategy. The challenge of demand-side management (DSM) in home area networks (HANs) is addressed, offering a solution based on "multi-agent deep reinforcement learning in real-time." This technique is designed to effectively navigate the complexities of DSM in HANs (Hammad et al. 2021).

The optimal regulation of temperature, energy supply, and price is the aim of the suggested energy management (EM) system. A thorough analysis is carried out to investigate the possible effects of price adjustments on the proposed algorithm. The DSM approach used in this study encourages a decrease in home energy use over a predetermined time frame. We use deep reinforcement learning to tackle this problem. The user’s decision-making dilemma is modeled by means of a “Markov decision process (MDP).” The goal is to choose the MDP’s best course of action, as shown by the following equation, in order to maximize the expected total reward, or E (Table 2).

Strategies for demand-side EM and their significance

| DSM strategies | Features | Merits | Demerits | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak shaving | Cutting back on energy use during high demand to prevent supply overstretch | Lower cost per kWh of electricity | Financial difficulties for customers, violation of consumer conveniences | Traditional grids that are vertically oriented are often suited to highly predictable systems |

| Valley filling | Increasing demand during high electricity generation | Abolishes energy restrictions, reduces dump energies, customers benefit from cheap energy | Energy losses prevented through valley filling, but customer satisfaction at risk | Soon-to-be used storage facilities |

| Load shifting | Lessening disparity between profiles with high and low demand | Lessens the need for system expansions or upgrades | Mostly advantageous for utilities | Blend of valley filling and peak shaving |

| Load leveling | Shifting demands based on criticality factor | High level of system autonomy attained | Only possible with flexible and important load classifications | Displays traits found in other DSM techniques |

| Energy arbitrage | Storing cheaper energy to use or sell when costs are greater. | Boosts dependability of the supply system | Essential for managing energy storage successfully | Suited for intermittent RE systems |

| Strategic conservation | Utility-based DR initiative to encourage users to alter consumption patterns | Efficient use of energy | Demand predictions impacted by consumer preferences | Typically focusing on less energy use |

| Strategic load growth | Adoption of smart energy appliances for anticipated energy needs | Reduce waste energy, save money on energy | Only possible with dump loading systems | Must be combined with other tactics, not effective on its own. Raises utility revenues while enhancing consumer productivity |

| Flexible load scheduling | Plan with incentives for system dependability degradation | Enhances autonomy of the distributed generator (DG) system | May not be possible in systems with uniform tariffs | Most effective in multi-tariff integrated systems |

To mitigate peak load demand and overall electricity costs across three primary client categories residential, commercial, and industrial, an available solution is the Back Tracking Search Algorithm (Hossain and Fotouhi 2020). The proposed method represents an enhancement over the differential evolution (DE) process, specifically addressing the day-ahead scheduling of load DSM problems. The authors introduce a technique for multi-objective optimization (MOO) in DSM problems (Huang and Liu 2019). The cost of energy for a single day is computed through a discrete time-changing model. Schedules with manageable loads are generated using a greedy search approach, considering loads with varying average power density and limited on-time windows (Hussain et al. 2021). When the proposed approach is implemented successfully, all loads are scheduled, which lowers the cost and peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR). The following equation may be used to formulate the MOO for DSM problem:

where (u) can be seen as a matrix reflecting a home EM system-controlled equipment schedule, and the goal functions. The term “f(u) minimization” denotes the simultaneous minimization of each vector element while using the metrics “f1” for the energy cost and “f2” for the PAPR (Jakkala et al. 2020).

A unique home DSM system is shown in Figure 4. It is based on a clever load control technique that is applied on a half-hourly basis and has access to a variety of power consumption limits (PCLs) (Jayaraman et al. 2021). Real-time loads, user preferences, and comfort are all taken into account in the design. Time-of-use (ToU) pricing is used to evaluate how user choices affect demand response. The results of a traditional load management strategy that depends on predetermined PCLs are contrasted with those of the proposed control technique. The following equation serves as a mathematical representation of the optimization problem:

The concept of load shaping (Li et al. 2021): (a) Peak clipping, (b) Valley filling, (c) load shifting, (d) flexible load shaping, (e) strategic growth, and (f) conservation.

For scheduling loads throughout the day, a DSM strategy based on the latent Dirichlet allocation method is provided. Using a cost function and the probability density function of consumer appliance usage patterns, this method shifts loads. The primary objective of demand-side management (DSM) is achieved through the implementation of load-shifting strategies aimed at reducing costs (Kaddoum et al. 2021). Test findings indicate that employing the load-shifting approach effectively reduces the cost of power consumption, and utilizing a MATLAB-created neural network further diminishes the mean square error. Another application of the DSM approach focuses on a distribution network in three phases for flexible load scheduling. Beyond other DSM objectives, the primary aim is to efficiently address operational limit breaches (Karim et al. 2020). The effectiveness of the recommended strategy is evaluated through a case study on market scheduling, illustrating the concept’s application to mitigate high and over voltages. Market planning for minimizing both low and high voltages is exemplified through a case study aimed at reducing costs and peak load demand (Khademi et al. 2021).

The following is the formulation of the optimization problem: when the appliance is in the on state,

The objective curves value at time t is known as T of t.

District heating systems undergo DSM through substation regulatory plan control or load shifting. A substation controlling technique called “Differential of Return Temperatures (DRT)” is used to reduce thermal peaks without sacrificing interior comfort levels. Peak load reduction, entails load transfer to decrease peak times, flatten the load curve, and minimize the requirement for peak load. Research on the impacts of the Integrated Electricity and Gas System (IEGS), employing DSM measurements was conducted by Kwon and Kim (2020). The optimal scheduling of IEGS leads to an overall cost reduction, accounting for DSM compensation, operational costs, carbon emission costs, and investment costs. The study also provides typical operating constraints for the safe operation of gas and electrical networks. The specific problem is outlined in

As proposed by Lee et al. (2020), DSM is used to regulate power electronic loads (PELs) in order to lower the system’s running expenses. The bus voltage is determined by modeling the PELs as variable resistors in this study. The best voltage solution for managing the PELs and reducing system expenses is then determined using a DSM procedure. The goal of the objective issue, which is to determine the optimal bus voltage V that lowers overall system costs is characterized as a minimization problem (Lee et al. 2020).

3 DSM techniques in microgrid

For the operation of a microgrid, a smart electrical network or large generators may not be necessary. A microgrid operates in two modes: synchronized with the electrical grid when connected, and autonomous (Lee and Kim 2021). Serving neighboring consumers, a microgrid supplies electricity from integrated DERs and serves as a local energy source. Future electrical systems are expected to incorporate microgrids, with ongoing efforts to enhance their operation (Li et al. 2019). For the purpose of microgrid EM, many DSM programs are in place. A previous study investigated how DSM procedures impact Evs distributed at customers’ sides in a single LV microgrid. The objective is to assess how user-side control activities influence the isolated microgrid’s functionality. It also examines how non-coordinated DSM operations affect the microgrid’s peak power, voltage dips, and energy losses. Using the Neplan environment to build a suitable microgrid model and a MATLAB-developed Monte Carlo approach, the study evaluates end users’ daily regulated load profiles, considering seven different options. The analysis reveals a reduction in energy loss, with voltage drop and peak power consistently within authorized levels. The presence of photovoltaic (PV) plants is identified as a factor contributing to energy loss (Li et al. 2021). The study’s findings provide valuable insights for operators of distributed systems operating in fully automated settings.

Li et al. (2021) proposed a real-time DSM system with two stages for microgrids, considering uncertainty and schedulable ability (SA). The system introduces an internal pricing approach to reduce operational expenses and maintain power balance.

In the second stage, Response Executors (Res) are equipped with a model for schedulable abilities (SA) and a technique for measuring SA to better accommodate uncertainties (Zhao et al. 2021). The SA assessment system utilizes historical information and real-time data from Res, facilitating a more agile allocation of authority among response executors online. A previous study introduced a DSM strategy to ensure that the microgrid’s predicted day-ahead energy supply can meet the current demand, taking into account customers’ anticipated aggregate load requirements. Users employ various methods, such as stored energy and renewable power, to charge or discharge their EVs. Customers face penalties if their actual load demand deviates from the projected demand (Lin et al. 2021). Lin et al. (2021) proposed a real-time DSM approach for a microgrid connected to RERs. The algorithm aims to maximize customer satisfaction while minimizing costs. Equation (10), which expresses the utility maximization technique, is offered as a way to minimize the overall cost of energy while increasing supplier and user satisfaction. This methodology is implemented on a per-user basis.

Power scheduling, considering variable loads, is employed to minimize power consumption fluctuations. The proposed DSM approach prioritizes simplicity over complex algorithms. Wu and Zhang (2021) introduced an electric spring to control demand and eliminate voltage swings in microgrids due to RERs, maintaining constant voltage for critical loads. Three control scenarios demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. A previous study utilized direct load control and automated generation control for microgrid frequency changes.

A microgrid EM system (G) (Ma et al. 2019) suggests optimized storage management in the presence of DGs, reducing grid load and consumption prices. A demand response management (DRM) system involves service providers at various energy grid levels for mutual benefit. In the integration of RER on consumer properties, Ma et al. (2020) proposed a resource scheduling system, optimizing energy usage cost-effectively and suggesting a battery scheduling technique. The impacts of solar and wind energy on distribution system operators (DSOs) and DSM are examined by Ma et al. (2020) with a focus on lower DSO costs and higher DSM value and a stochastic multi-objective linear programming model for DERs scheduling that is ideal is presented.

Energy hubs aim to interconnect energy carriers, using renewable sources like solar PV and windmills, reducing greenhouse gas output. Mahmud et al. (2020) suggested strategies for residential applications with integrated renewable energy, considering loads, costs, and flexible generation. The incorporation of renewable energy in electricity grids increases operating costs prompting a technique using demand response for electricity changes. Meng et al. (2020) emphasizes production planning and reserve market participation for economic potential. Miao et al. (2019) provides architecture for EM, employing ToU pricing and DSM to cap energy use. The focus is on maximizing customer satisfaction and minimizing energy costs through effective scheduling. This involves proposing real-time electricity scheduling (RTES) in smart homes using evolutionary algorithms. A DSM methodology for smart grid-connected homes with distributed generation, utilizing AI for battery management to lower customer power costs is introduced by Mohammadi and Sadeghi (2019). In smart energy management (SEM) systems for PV generation, renewable sources gain significance due to reduced fossil fuel usage. An intelligent system for daily planning and precise energy forecasting is developed. The intelligent smart energy management system (ISEMS) employs forecast-based DSM, IoT for data collection, and solar energy generation in a smart grid environment (Nair and Devassy 2021).

3.1 SEM systems used for PV generation

With the decrease in the usage of fossil fuels diminishing the world's energy production capabilities, renewable sources have gained more significance in the power sector. They are increasingly vital to meet the escalating demands of customers and the necessity for dependable, economically feasible energy supply (Nardelli et al. 2020). A new grid-connected system needs a small amount of PV storage capacity. Due to their discontinuous and extremely impulsive nature, RERs are frequently difficult to understand in terms of their potential advantages. To address this issue, an intelligent system of daily planning and precise energy accessibility forecasting is being planned and developed (Nguyen et al. 2020). An ISEMS was developed as part of this endeavor with a focus on renewable energy to control energy demand in a smart grid environment (Niu et al. 2020). The ISEMS’’ demand-side EM architecture makes it possible to employ RERs (Niknam et al. 2021). ISEMS is made up of a forecast-based ISEMS, an IoT environment for customer data collection on energy usage and consumption, and solar energy generation and data collection. Power scheduling, considering variable loads, is employed to minimize power consumption fluctuations. The proposed DSM approach prioritizes simplicity over complex algorithms. Pal et al. (2021) introduced an electric spring to control demand and eliminate voltage swings in microgrids due to RERs, maintaining constant voltage for critical loads. Three control scenarios demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. A previous study utilized direct load control and automated generation control for microgrid frequency changes.

A microgrid EM system (G) suggests optimized storage management in the presence of DGs, reducing grid load and consumption prices (Pan et al. 2020). A DRM system involves service providers at various energy grid levels for mutual benefit (Perumal et al. 2021). In the integration of RERs on consumer properties, proposed a resource scheduling system, optimizing energy usage cost-effectively and suggesting a battery scheduling technique. The effects of wind and solar energy on DSM and DSO were explored, emphasizing increased DSM value and reduced DSO cost. In the literature, introduced a stochastic multi-objective linear programming model for optimal scheduling of DERs was introduced. Energy hubs aim to interconnect energy carriers, using renewable sources like solar PV and windmills, reducing greenhouse gas output. Priyakumari and Mishra (2021) suggest strategies for residential applications with integrated renewable energy, considering loads, costs, and flexible generation. The incorporation of renewable energy in electricity grids increases operating costs prompting a technique using demand response for electricity changes. Rajasekaran et al. (2019) emphasized production planning and reserve market participation for economic potential. Ramachandran et al. (2021) provided architecture for EM, employing ToU pricing and DSM to cap energy use. The focus is on maximizing customer satisfaction and minimizing energy costs through efficient scheduling strategies. Rao et al. (2020) proposed RTES in smart homes using evolutionary algorithms. A DSM methodology for smart grid-connected homes with distributed generation was introduced, utilizing AI for battery management to lower customer power costs.

In SEM systems for PV generation, renewable sources gain significance due to reduced fossil fuel usage. An intelligent system for daily planning and precise energy forecasting was developed by Rao et al. (2021a,b). The ISEMS employs forecast-based DSM, IoT for data collection, and solar energy generation in a smart grid environment (Rao et al. 2021a,b). IoT was created to use devices in microchips, controls, transceivers, data, and communication protocols to enable rapid and easy interaction among commonplace parts like computers, smartphones, sensors, and actuators over the internet. Therefore, compared to human inspection, the system interacting with the IoT can monitor and regulate the solar system in a vast and isolated area more efficiently (Rao et al. 2021a,b). The system outlined in the article was designed to track the values of PV cells for each of these parameters as well as the voltage, current, temperature, and amount of sunshine received by solar cells (Rao et al. 2021a,b). Data collected by Arduino was uploaded to the internet using the NodeMCU wireless transmitter (Salehahmadi et al. 2021). In the presence of an internet connection, all sensor data are compiled and presented to the user as an analyzable image using ThingSpeak, an open-source IoT cloud platform (Sardari and Sardari 2020). A schematic of the system block is shown in Figure 5. The open-source IoT cloud network application ThinkSpeak is used in theory. Data from the sensor were uploaded to the cloud by the Arduino kit that was connected to the Wi-Fi device. The user receives a status app, and all information records created by the sensors are refreshed. To utilize this service, the user first needs to register an account or IP address that includes several channels for measuring different network parameters. Users can access information, including photos, through this platform. The data is readily available via an online interface, and monitoring is conducted over the internet (Rao et al. 2022). The benefit of the system is that it can be used to conveniently monitor solar cell production data from any location with an internet connection. The gateway information system diagram is illustrated in Figure 6 (SeyedShenava and Niazi 2020).

The EVs power flow diagram (Sardari and Sardari 2020).

The drive train-specific long-term passenger vehicle scales globally (Jayaraman et al. 2021).

3.1.1 Forecasting

The production of renewable solar PV electricity is a plentiful and promising source of energy worldwide. The tropical climate, surrounding circumstances, meteorological elements (such as temperature, humidity, wind direction, and speed), and most importantly, the time of day when the sun rises and sets, all have an impact. Therefore, its main drawback persists in being highly erratic and intermittent (Rao et al. 2022). The efficient use and management of these resources is essential for meeting the consumer’s rising energy demand. The energy sector has made significant strides in the digital world with an IoT ecosystem for trustworthy data collecting, remote monitoring, and controlling (Shahsavari and Soroudi 2020).

3.1.2 PV generation

The electricity sector will increasingly rely on standalone solar PV generation as people’s concerns about the usage of fossil fuels grow. Therefore, in order to ensure optimal utilization, it is crucial to accurately estimate PV production data and arrange the load/appliance operation at the consumer end (Shanmugam et al. 2020). Depending on the size of the given information, many strategies can be taken into consideration for replicating the sun irradiation, the parameters being used, and the details of utilization. For utilities and energy consumers, accurate forecasting of renewable energy offers numerous benefits, such as affordability, dispatchability, and effectiveness (Rao et al. 2023).

3.1.3 SEM unit

In the SEM system, a smart socket module and an SEM unit are located at opposing ends as seen in the whole SEM system in the photograph. The SEM Gateway serves as the system’s brain, while the smart socket regulates the appliances. Thanks to Xbee modules, the SEM Gateway and smart socket module may interact with one another in both ways (Shi et al. 2021). At the gateway end and the other end, the Xbee modules are set up as a coordinator and a router, respectively. Any external signals are received by the main SEM unit, which then employs them to execute a power negotiation process and provide control signals to the smart socket module (Singh and Tripathi 2021).

3.1.4 Smart socket

A smart socket module is used by a load controller to serve as an interface between the selected appliance and the SEM unit. It offers fundamental power management capabilities, such as control and communication. Depending on its function, each architecture module has a particular role (Sun et al. 2021).

3.1.5 Data collection and processing module

Real-time electrical data collection is the main goal in order to determine the perceived power, true power, energy consumption, power factor, and other electrical metrics like RMS voltage and current measurements of an appliance. In this context, LEM sensors, based on the Hall effect, are employed to monitor voltage and current (Sundararajan et al. 2021).

3.1.6 Control module

Specific appliances are controlled, being turned ON or OFF through an electrical relay circuit with guidance from the SEM Gateway (Talavera and Wilches-Bernal 2021).

3.1.7 Communication module

It establishes a two-way channel of communication between a smart socket module and the SEM Gateway.

3.1.8 IOT environment with energy monitoring system

To access power parameters through the Internet, local host can be replaced with a specific domain name as the hostname. The server builds numerous databases to hold different power attributes. The power data are uploaded to the server every 5 min. Only authorized users with proper login credentials are able to access the web portal’s webpage (Tariq et al. 2020).

The IoT was created to simplify internet-based communication between commonplace objects like computers, smartphones, sensors, and actuators. By making use of transceivers, microchips, controllers, data, and communication protocols, IoT facilitates quick and simple interactions. This communication system proves more effective in monitoring and controlling large, isolated PV systems in comparison to human inspection.

The system outlined in the article is designed to monitor the PV values for each parameter as well as the voltage, current, temperature, and amount of sunshine received by solar cells (Tsegay et al. 2021). The NodeMCU wireless communication transceiver uploads data captured by Arduino to the internet. ThinkSpeak, an open-source IoT cloud platform, compiles and presents all sensor data as an analyzable image when an internet connection is available (Verma and Sharma 2021). Figure 5 illustrates the system block diagram, utilizing ThinkSpeak for internet-based monitoring. The user receives a status app, and all sensor data are refreshed (Vilathgamuwa et al. 2021). The system’s advantage lies in the ability to easily monitor solar cell output data from anywhere with an internet connection, as shown in Figure 6. Forecasting is crucial for efficient utilization of solar PV electricity, influenced by environmental factors and meteorological characteristics. Accurate forecasting is essential for meeting rising energy demand. The IoT ecosystem plays a significant role in data collection, remote monitoring, controlling, and contributing to the efficient use of renewable resources.

As the electricity sector increasingly relies on standalone solar PV generation, accurate estimation of PV production data becomes crucial for optimal utilization and load/appliance operation. Accurate forecasting of renewable energy benefits affordability, dispatchability, and effectiveness for utilities and energy consumers (Wang et al. 2021).

A smart socket module and an SEM unit make up the SEM system. The smart socket controls appliances, while the SEM Gateway functions as the system’s brain. The SEM Gateway and smart socket module may communicate with each other in both directions, thanks to Xbee modules. The smart socket module gets control signals from the SEM unit, which also handles power negotiation procedures and receives signals from outside sources (Wang et al. 2020). The smart socket module acts as an interface, offering power management capabilities and facilitating control and communication with specific appliances. Different modules within the SEM system have specific roles, including data collection and processing, control, and communication modules (Wang et al. 2020).

In the IoT environment with an energy monitoring system, power parameters can be accessed through the internet. The server builds databases to hold different power attributes, and data are uploaded every 5 min. Only authorized users with proper login credentials can access the web portal’s webpage (Wang et al. 2021) (Table 3).

Goals and options for demand response

| Author | Interconnected system | DSM techniques | Performance state | Supervisory control | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priyakumari and Mishra (2021) | Hybrid system using solar power and batteries | Model predictive control program for DR | Grid-connected | Centralized | Reduced the customer’s portion of the power bill. Maximized the usage of battery storage and solar energy |

| Previous study | Wind-powered industrial microgrid with energy storage system | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Wind turbines cut carbon emissions by 88%, DSM resulted in an additional 30% cut. Reduced overall power costs by 73% |

| Perumal et al. (2021) | PV panel, wind turbine, and energy storage system in a residential microgrid | DR scheme utilizing the linear programming approach | Grid-connected | Decentralized | The need for energy was decreased by 16%. Reduction in energy consumption and CO2 emissions throughout all operating hours was 10%. The amount of renewable supply was decreased by 74% while it was in use |

| Niu et al. (2020) | PV panels, a wind turbine, a diesel engine, a battery bank, and a water delivery system | Combined with an artificial neural network and DSM mechanism | Grid-connected | Decentralized | Reduced the operation’s cost by 3.06% |

| Niknam et al. (2021) | PV installations throughout homes | EM algorithm based on online events for load scheduling | Grid-connected | Centralized | Assured consumer comfort while also lowering electricity cost |

| Nardelli et al. (2020) | SG network using dispersed, green power sources | Parallel autonomous optimization for the DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Decreased power bill and electricity producing cost |

| Previous study | Microgrid system includes radial load feeders, wind turbine, fuel cells, solar panels, and micro turbines | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Peak load on the grid tie line was reduced. Achieved ideal battery and diesel generator scheduling |

| Meng et al. (2020) | Renewable generators and energy storage in a microgrid | DR scheme | Isolated | Centralized | Achieved optimum peak load dispatch and electricity generation. |

| Ma et al. (2020) | Network SG with significant wind penetration | DR scheme | Isolated | Centralized | 30% cost reductions were attained. Over 56% of demand was altered |

| Previous study | SG network and energy storage system | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Reduced peak demand as well as lowered customer’s energy costs |

| Lee et al. (2020) | Microgrid system combining solar and wind power | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Decentralized | Decreased operating expenses and carbon emissions |

| Previous study | Wind farm and the SG network | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Achieved 24-h energy production and consumption timing that was ideal. |

| Krishna Rao et al. (2023) | PV system, wind turbine, and batteries in a microgrid | Mixed-integer linear programming and the DR technique | Isolated | Decentralized | Peak load and operational costs were both decreased by 17.2 and 36.8%, respectively |

| Koh et al. (2020) | PV panels, wind turbines, diesel engines, and batteries | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Centralized | Operating and environmental costs are decreased |

| Kim et al. (2021) | SG network including a PV system | DR scheme | Grid-connected | Decentralized | Over the course of a year, the load factor is examined and raised |

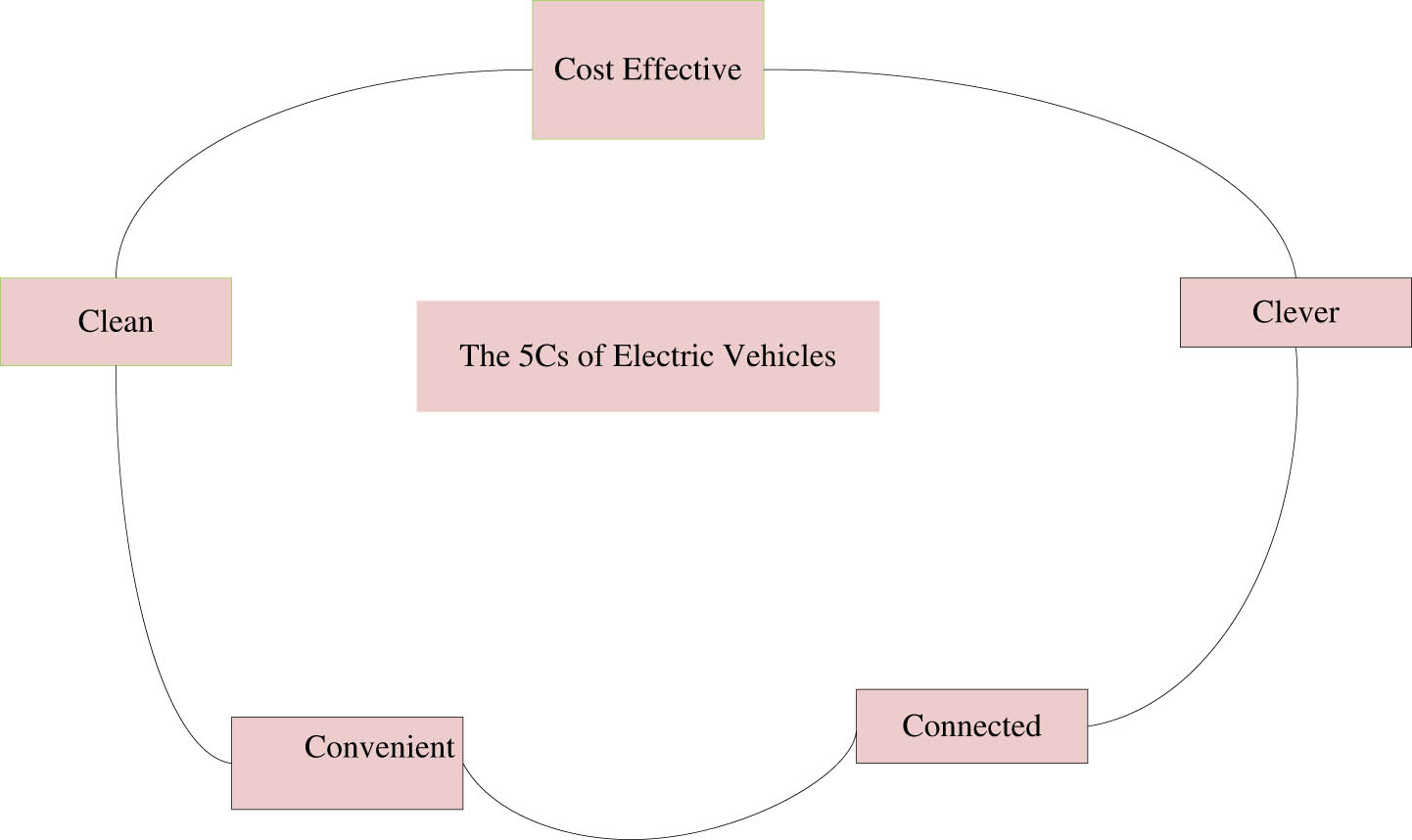

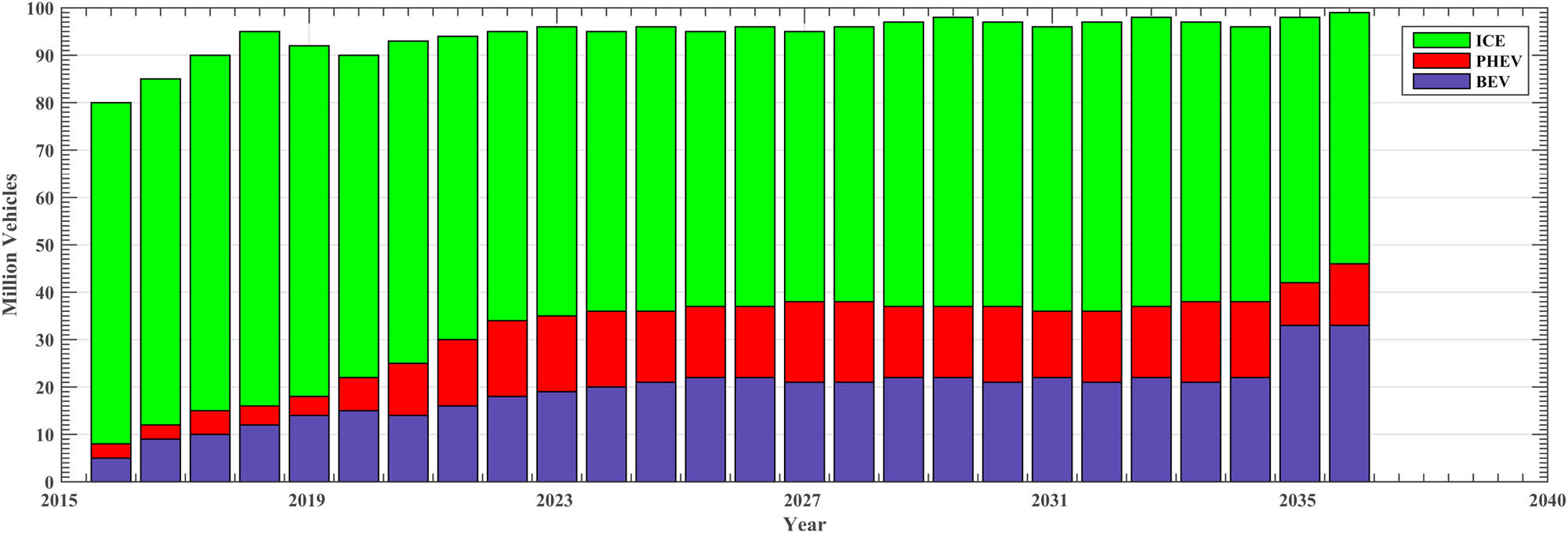

4 DSM techniques for systems using EVs

The increasing popularity of EVs is driven by growing concerns about severe environmental pollution and energy shortages. Recent research, as illustrated in Figure 5 vividly showcases the accelerated global development of hybrid and electric cars. This surge in adoption reflects a collective effort to address environmental challenges and transition toward more sustainable and energy-efficient transportation solutions (Wijaya et al. 2020).

The Power scheduling that takes changeable loads into account has been used to minimize variations in power consumption. The proposed approach for DSM does not include the computing time needed by complicated algorithms. Wu et al. (2020) suggested installing an electric spring to control demand and eliminate voltage swings brought on by the inclusion of RERs in a microgrid. In addition to automatically scheduling the noncritical loads, this will instantaneously maintain constant voltage for the critical loads. It can control voltage in both residential and commercial constructions when employed. Three different control scenarios are used to illustrate the usefulness of the suggested controller. Direct load control and automated generation control are used by the authors to address changes in microgrid frequency and maintain the microgrids’ secure operation (Wu and Zhang 2021). The authors provide a campus microgrid EM system method (G), in which they suggest storage that is managed and scheduled in the best possible way when DGs are present, assisting in lowering grid load as well as consumption prices (Wu and Zhang 2021). Additionally, a DRM system was created in which service providers are used to choose solutions that are advantageous to both consumers and utilities. The service provider is situated on several levels of the energy grid, with the neighborhood being at the lowest level and other service providers being at the greatest level (Xiang et al. 2019).

4.1 RER, DER, and storage device integration in systems using DSM techniques

Integration of RER on consumer properties is quickly gaining acceptance. Xu et al. (2019) proposed a resource scheduling system to lower the cost of each user’s energy usage through effective utilization of the energy generated. To choose the right size of battery to maximize savings, a battery scheduling technique is suggested. The study demonstrates the effects of installing wind and solar energy on DSM and DSO. The benefits include a higher DSM value and lower DSO costs. The limitations associated with loads and storage systems that are thermostatically regulated are taken into account by the authors (Xu et al. 2021). The DER system’s ideal operating schedule was utilized by Yang et al. (2019) to lessen the negative economic and environmental effects of DER systems with diverse energy sources. The suggested stochastic multi-objective linear programming model handles the best operation scheduling for DER (Yao et al. 2019).

The interplay of many energy carriers through the grid is the goal of these energy hubs. Additionally, employing electricity from renewable sources like throughout the process, energy hubs use solar PV and windmills rather than gas-fired systems of scheduling horizon has reduced greenhouse gas output (Yasin et al. 2021). For stochastic producers, to lessen load shedding, as a fallback, combined cooling, heating, and power systems are utilized. Surplus energy is also kept in energy-storage devices. Ye et al. (2021) depicted the idea for the hub of renewable energy. Integrated with distributed energy systems, a demand response programmer, the rapid forward selection method, and Monte Carlo simulation are utilized. Simulation results demonstrate the effectiveness of the recommended technique in managing energy within energy hubs (You et al. 2019). For residential applications with integrated renewable energy resources (RERs), temporary reductions in system costs can be achieved (Yuan et al. 2021). They consider loads, energy costs, and flexible renewable generation. They have taken into account the battery’s cost and operating limitations, the power needs and life expectancy of each load, as well as the minimum and average delay standards (Zhang et al. 2021).

Increased power system operating costs are a result of the enormous magnitude of swings and uncertainties brought on by the wide-scale incorporation of RERs into electricity grids. Zhang et al. (2019) introduced a method utilizing demand response from multiple domestic appliances to mitigate fluctuations in electricity consumption. Increased activation of flexible loads is required due to higher energy price variations brought on by the inclusion of RERs. According to Zhang et al. (2019), harnessing the economic potential of emerging energy markets requires attention to patterns, production planning, and active participation in reserve markets.

For optimal outcomes, Zhang et al. (2019) provided architecture for EM for controlling the PV power outputs that consist of systems for managing supply and demand that use ToU pricing. To individually cap energy use, the DSM system employs PV power outputs in the distribution network hence lowering residential prices and any resulting discomfort to homeowners. The supply-side management system strives to preserve the quality of the electricity by utilizing the PV power outputs as fully as is practical (Zhang et al. 2019). To maximize customer pleasure while minimizing user energy costs through the most effective scheduling of household appliances, the EM by using energy storage technologies and RER in modern dwellings was examined by Zhang et al. (2019). In RTES, a DSM program is suggested for managing energy in smart homes. The evolutionary algorithm is used to solve the optimization issue at predetermined intervals, and the scheduling system inputs are changed before each optimization computation (Zhang et al. 2021).

Zhao et al. (2021) developed a methodology to conduct DSM for homes connected to a smart grid and equipped with distributed generation and energy storage devices. The battery management and optimization strategies used in this method are managed by artificial intelligence. The goal of the research is to lower customer power costs (Zhao et al. 2020).

5 DSM techniques for systems using EVs

Due to severe environmental pollution and energy shortages, EVs are becoming increasingly popular. Figure 5 from recent research depicts the accelerated global development of hybrid and electric cars. The rising concerns over severe environmental pollution and energy shortages have propelled the increasing popularity of EVs. Recent research, as illustrated in Figure 5 (Zhou et al. 2021) highlights the accelerated global development of hybrid and electric cars. The integration of EVs in energy systems has significant implications for DSM, presenting opportunities for more sustainable and efficient energy consumption.

The surge in EV popularity is driven by mounting concerns about severe environmental pollution and energy shortages. Recent research, exemplified in Figure 5, vividly portrays the rapid global development of hybrid and electric cars. This trend underscores the urgent need for innovative approaches to DSM tailored to systems incorporating EVs. As these vehicles gain traction, DSM strategies can play a pivotal role in addressing environmental challenges and optimizing energy usage in the evolving automotive landscape. Due to severe environmental pollution and energy shortages, EVs are becoming increasingly popular. Figure 5 from recent research (Zhou et al. 2019) depicts the accelerated global development of hybrid and electric cars.

The increasing popularity of EVs is driven by growing concerns about severe environmental pollution and energy shortages. Recent research, as illustrated in Figure 5, vividly showcases the accelerated global development of hybrid and electric cars. This surge in adoption reflects a collective effort to address environmental challenges and transition toward more sustainable and energy-efficient transportation solutions (Zhu et al. 2021).

Distributed solar PV production may be used to address the network’s energy shortfall. Storage is important in this scenario. As a DSM approach, EV is utilized to lessen the volatility of solar PV (Zhu et al. 2020). When acting as a source or load, an EV’s behavior depends on three factors. These three variables are state of charge (SOC), system voltage, and PV output. The use of EVs as a load to fill in energy-deficient valleys and as a source to reduce peak loads this article talks about how to deal with solar PV’s unpredictable and intermittent characteristics (Zubi et al. 2019). The probability of the four outcomes of each scenario was high and low PV generation with EVs, as well as high and low PV generation without them. The IEEE 33-bus radial network is connected to the 2 MW distributed solar PV generation. Using data on day-ahead prices and solar PV electricity generation, the best solar PV panel size is chosen, which also optimizes consumer electricity expenses (Rao et al. 2022). The teacher-learner-based optimization (TLBO) method is used in the formulation and resolution of the ideal issue. Three case studies are taken into account for the analysis: normal load, a load optimization DSM program, and a load and PV generation optimization DSM program. The price per unit for these three case studies is then contrasted. It showed how much more economical the system is when the DSM software and nearby PV producing are used (Rao et al. 2021a,b, Khedkar et al. 2021). When households that own plug-in electrical vehicles (PEVs) plan their daily energy consumption and the cost of charging, they utilize the residential neighborhood as an agent of the local users and make money from PEV discharge in various communities. Ribeiro et al. (2020) proposed a machine learning (ML)-based intelligent charging technique that would allow EVs to be charged in real-time based on factors such as the environment, cost, driving patterns, and demand periods. The entire cost of EV energy is what this study aims to reduce (Rao et al. 2024).

Voltage fluctuations and a rise in deployment costs for charging infrastructure are caused by integrating EVs into the grid to fulfill the highest charging demand. Utilizing a demand response strategy can cut expenses and eliminate the need for peak billing. In the literature, a control approach and a DSM program to include and govern the distributed charging of EVs were presented. For this reason, an automatic fuzzy-based controller that takes into account the connection point voltage, utility signal, and owner needs is presented. It is advised to use the multi-group to prevent system peaks and the rebound effect; one might use the multi-group ToU with critical peaking (MTOUCP) technique. A new DSM program was used to test the proposed controller. According to the study, it can efficiently control EV charging, avoid LVs, and reduce system peaks.

EVs that are connected to household distribution networks are presenting load to those systems. The distribution system must deal with additional load needs as a result of EVs often charged in residential settings. A DSM plan has been released to lessen the burden that EVs place on the distribution network (Pan et al. 2020). The worst power peaks are avoided using the DSM approach. There have been two DSM algorithms suggested. Two states have been established for the proposed DSM algorithms. In the first state, loads from homes and EVs are transferred. Just EV loads are transferred in the second state. Even while they cannot fully charge every car in the network in a day, the DSM techniques do succeed in lowering the total load on the transformer and the heat pressures placed on the conductor (Nguyen et al. 2020).

The most often utilized restrictions from the research study on DSM taking EVs are as follows:

The EV’s charge level

Constraints on PEV charging and discharging

Constraints on the power system

Battery power limitations.

The car cannot be charged and discharged simultaneously during plug-in electric vehicle charging and discharging operations. Distributed solar PV production emerges as a solution to address energy shortfalls in the network, with storage playing a crucial role. In a DSM approach, EVs are utilized to mitigate the volatility of solar PV (Nardelli et al. 2020). The behavior of an EV, acting as a source or load, is influenced by three variables: SOC, system voltage, and PV output. The article explores leveraging EVs as a load to fill energy-deficient valleys and as a source to reduce peak loads, addressing the unpredictable nature of solar PV.

Four possible scenarios are taken into account in the study: high and low PV generation in the presence of electric cars and high and low PV generation in the absence of them. Day-ahead pricing and solar PV energy generation data are used to establish the ideal solar PV panel size using the IEEE 33-bus radial network linked to 2 MW distributed solar PV power. The formulation and solution of problems are done using the TLBO technique. Three case studies, the DSM program for load optimization, the usual load, and load and PV generation optimization DSM program, are analyzed, comparing the unit price for each scenario. The results demonstrate the economic benefits of incorporating DSM software and nearby PV generation (Mahmud et al. 2020). In another study households owning PEVs strategically plan their daily energy consumption and charging costs. They utilize the residential neighborhood as a collective agent for local users, earning revenue from PEV discharge in different communities. A ML-based intelligent charging technique enables real-time charging decisions for EVs based on environmental factors, cost, driving patterns, and demand periods, aiming to reduce the overall cost of EV energy (Lee and Kim 2021). The integration of EVs into the grid for charging purposes leads to voltage fluctuations and increased deployment costs. A control approach and DSM program for governing distributed EV charging is introduced, employing an automatic fuzzy-based controller considering connection point voltage, utility signal, and owner needs. The study recommends the use of the MTOUCP technique to prevent system peaks and the rebound effect. Testing the proposed controller with the new DSM program demonstrates its efficiency in controlling EV charging, avoiding LVs, and reducing system peaks.

As EVs connected to household distribution networks present additional load demands, a DSM plan is proposed to alleviate the burden on the distribution network. The DSM approach avoids the worst power peaks, with two suggested algorithms operating in two states to transfer loads from homes and EVs. These techniques effectively reduce the total load on transformers and alleviate heat pressures on conductors (Koh et al. 2020). EV charge level limits, PEV charging and discharging limitations, power system limitations, and battery power limitations are common restraints seen in DSM research utilizing EVs. It should be noted that operating PEVs while charging and discharging at the same time is prohibited.

6 DSM methods implementation strategies

6.1 Optimization algorithms

Electricity consumption varies across locations, making it essential to strike a balance between user comfort and power utilization. In a bid to minimize residential demand, a combination of GAs and Pigeon-inspired optimization (PIO) is proposed (Kim et al. 2021). The study evaluates GA, PIO, and HGP under a real-time pricing system, demonstrating their potential to reduce power expenses and consumption while enhancing customer satisfaction. Hybrid bio-inspired optimization techniques, specifically Bacterial foraging optimization, are employed in a residential EM method to reduce peak loads and power costs. This approach considers real-world equipment limits and user perspectives. Additionally, an optimized control strategy is proposed, combining dynamic pricing, user response, and equipment operating capabilities to lower power costs. To enhance energy use and DSM, an EM controller is introduced, utilizing heuristic optimization approaches such as "BAT inspired and flower pollination" for shiftable appliances and "hybrid BAT pollination optimization algorithm (HFBA)" for residential appliances (Khedkar et al. 2021). Fuzzy logic is incorporated to regulate interruptible appliances, addressing the unpredictability associated with manually operated appliances.

6.2 Pricing based on ToU

ToU pricing structures, where rates vary across predetermined periods, prove effective in lowering costs for both utilities and consumers. Studies in emerging nations like China explore the impact of ToU pricing at the residential level (Hossain and Fotouhi 2020). ToU pricing is incorporated in a decentralized DSM framework, optimizing residential and commercial loads with RER (Haider et al. 2021). The implementation of a household energy management system is recommended to schedule the use of RERs based on ToU pricing (Ghosh and Saha 2021). Multi-objective residential DSM with batteries is proposed to reduce power expenses and peak loads for residential consumers using ToU pricing. A mechanism for managing supply and demand sides based on ToU pricing is suggested for effective use of residential PV production (Gomez-Quiles and Valdivieso-Sarabia 2019).

6.3 Game approaches

Game approaches are employed to model interactions in the electricity market, considering electricity providers, local agents, end-users, and aggregators (Perumal et al. 2021). Different game strategies, including Bayesian games and cooperative games, are utilized to optimize day-ahead energy usage, especially in scenarios involving EVs (Ma et al. 2019). Non-cooperative game approaches characterize challenges in a smart grid with multiple energy suppliers, addressing peak demand scenarios (Eisen and Ribeiro 2020). A cooperative game technique is used to formulate a multi-objective residential side demand management issue, finding a compromise between reducing customer power costs and peak load demand (Dong et al. 2019). Cooperative games, based on super-criterion and Pareto-minimum solution, provide a balanced approach for various scenarios involving different numbers of home clients.

6.4 Research perspectives in IoT EM

EM is essential in microgrids for the effective and seamless transfer of energy among the numerous energy sources and storage innovations for a reliable, cost-effective, durable, and efficient operation. Because RERs are intermittent, a lot of expensive energy storage and a variety of energy sources are needed to ensure a safe and dependable power supply. EM is crucial in microgrids with RERs, dispatchable energy sources, storage systems, and loads to ensure the greatest possible power flow between the various components and preserve the system's optimal stability and cost-effectiveness. In EM studies, which are primarily simulation-based, there is a large category of publications using a range of algorithms and methodologies. However, further research is necessary to confirm the viability of applying the suggested methods in actual microgrids (Chen et al. 2020). The authors believe that simulation based on real-time systems can produce more credible results for practical application even when many methodologies are used in EM research since the results accurately mirror the behavior of the real system. More investigations using hardware in loop to assess the viability of practical implementation are essential for validating the results (Baneshi et al. 2020).

6.5 Future directions of demand side SEM system

There are several interesting possibilities in the fast-developing field of grid energy storage, including the research directions described here.

Advanced control and optimization strategies: Modern control and optimization techniques are being developed by researchers to boost the effectiveness and performance of energy storage systems in microgrids (MGs). Innovative methods like artificial intelligence or machine learning could be used in these tactics (Ma et al. 2019).

Hybrid energy storage systems: To address the issues with individual storage technologies and offer better overall performance, hybrid energy storage systems which integrate numerous storage technologies like batteries, capacitors, and super capacitors are being researched (Miao et al. 2019).

Grid integration and management: In order to ensure the MG's dependable and successful functioning and interactions with the main grid, appropriate grid integration and management strategies are becoming increasingly important.

New storage technologies: The effectiveness and efficacy of cutting-edge energy storage technologies are being investigated in contrast to those of the present, including flow batteries, thermal storage, and hydrogen storage.

Smart grid integration: With the widespread adoption of smart grid technologies, researchers are focusing on enhancing the effectiveness and reliability of power transmission. Innovative methods for integrating energy storage devices into smart grids are being explored to address these needs.

Life cycle analysis: In order to comprehend how MG energy storage systems affect the environment, and to pinpoint areas for improvement, researchers are performing life cycle assessments.

Standardization: Standardization is required because of the proliferation of various MG configurations and energy storage technologies in order to guarantee system interoperability and compatibility.

Energy trading: To maximize energy utilization and cut costs, researchers are looking into the potential for energy trade across other MGs and between microgrids and the main grid.

Reliability and resiliency: Researchers are looking into redundant storage systems and cutting-edge control algorithms as potential improvements for the dependability and resilience of energy storage systems in MGs (Nardelli et al. 2020).

Optimal sizing and placement: Effective techniques for designing and positioning these systems are required in order to maximize their performance and financial feasibility in light of the growing demand for MG energy storage systems.

Aging and degradation: The capacity and performance of energy storage devices may decline with time, which might reduce their reliability and efficiency. Researchers can enhance the replacement and maintenance of MG energy storage devices by investigating modeling and predicting the aging and degradation of these systems.

Environmental and social impact: In order to reduce adverse effects and advance sustainability, Energy storage systems in MGs are being studied for their environmental and social consequences, including how they affect social justice, resource consumption, and land use.

Electromagnetic compatibility: Energy storage systems must be electromagnetically compatible in order to avoid interference and guarantee reliable operation in microgrids, where electronic gadgets and wireless communications are proliferating. Last but not least, as the sector develops, energy storage technologies and the uses for them in MG systems are expected to develop and innovate further (Niu et al. 2020).

7 Conclusion

This comprehensive analysis' conclusion highlights the importance of the quickly developing field of DSM based on the IoT in relation to the production of PV power. The main conclusions highlight how crucial it is to use IoT technology to improve the integration of PV systems into contemporary energy networks and optimize patterns of energy use. The study reveals a diverse array of approaches and technologies employed in IoT-based DSM, showcasing a nuanced understanding of the intricate interactions between PV power generation and IoT applications. The literature review not only examines the state of the art at the moment, but it also highlights how IoT-driven solutions may be used to solve important problems with energy efficiency, grid resilience, and solar energy resource efficiency.

This systematic examination provides valuable insights for scholars, industry practitioners, and policymakers, particularly as the renewable energy sector continues to expand. By offering a thorough overview of the most recent developments and creating the framework for potential future study avenues and practical applications, the study contributes to the collective knowledge base. The integration of IoT-based DSM emerges as a pivotal strategy for managing PV power generation in a sustainable and intelligent manner. The identified trends and innovations hold the promise of not only enhancing efficiency but also aligning with the overarching objective of establishing a more robust and environmentally friendly energy supply in the future. In essence, the study highlights the transformative potential of IoT technologies in reshaping how we approach EM, with a specific focus on harnessing the capabilities of PV systems. As these technologies continue to evolve, the implications for the renewable energy landscape are profound, clearing the path for a future in energy that is more robust and green.

-

Author contributions: Challa Krishna Rao: data curation, writing-original draft preparation, software, validation, and writing. Sarat Kumar Sahoo: conceptualization, methodology, software, supervision. Franco Fernando Yanine: visualization, investigation, reviewing and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: No Conflict for publication.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

Aguilar J., Ardila D., Avendaño A., Macias F., White C., Gomez-Pulido J., et al. (2020). “An autonomic cycle of data analysis tasks for the supervision of HVAC systems of smart buildings,” Energies, vol. 13, p. 3103.10.3390/en13123103Suche in Google Scholar

Agyemang J. O., Yu D., and Kponyo J. (2021). “Autonomic IoT: Towards smart system components with cognitive IoT,” in Proceedings of the Pan-African Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems Conference, Windhoek, Namibia, 6–8 September 2021, Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-93314-2_16Suche in Google Scholar

Ahmad T., Madonski R., Zhang D., Huang C., and Mujeeb A. (2022). “Data-driven probabilistic machine learning in sustainable smart energy/smart energy systems: Key developments, challenges, and future research opportunities in the context of smart grid paradigm,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 160, p. 112128.10.1016/j.rser.2022.112128Suche in Google Scholar

Ahmadi S. E., Rezaei N., and Khayyam H. (2020). “Energy management system of networked microgrids through optimal reliability-oriented day-ahead self-healing scheduling,” Sustain. Energy, Grids Netw., vol. 23, p. 100387.10.1016/j.segan.2020.100387Suche in Google Scholar

Aliero M. S., Asif M., Ghani I., Pasha M. F., and Jeong S. R. (2022). “Systematic review analysis on smart building: Challenges and opportunities,” Sustainability, vol. 14, p. 3009.10.3390/su14053009Suche in Google Scholar

Alkhatib H., Lemarchand P., Norton B., and O’Sullivan D. T. (2021). “Deployment and control of adaptive building facades for energy generation, thermal insulation, ventilation, and daylighting: A review,” Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 185, p. 116331.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.116331Suche in Google Scholar

Baidya S., Potdar V., Ray P. P., and Nandi C. (2021). “Reviewing the opportunities, challenges, and future directions for the digitalization of energy,” Energy Res. Soc. Sci., vol. 81, p. 102243.10.1016/j.erss.2021.102243Suche in Google Scholar

Baneshi E., Kolahduzloo H., Ebrahimi J., Mahmoudian M., Pouresmaeil E., and Rodrigues E. M. G. (2020). “Coordinated power sharing in islanding microgrids for parallel distributed generations,” Electronics, vol. 9, no. 11, pp. 1–16.10.3390/electronics9111927Suche in Google Scholar

Bashir A. K., Khan S., Prabadevi B., Deepa N., Alnumay W. S., Gadekallu T. R., and Maddikunta P. K. (2021). “Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for predicting smart grid stability,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 31, p. e12706.10.1002/2050-7038.12706Suche in Google Scholar

Benavente-Peces C. (2019). “On the energy efficiency in the next generation of smart buildings – Supporting technologies and techniques,” Energies, vol. 12, p. 4399.10.3390/en12224399Suche in Google Scholar

Bhat J. A., Jan B., and Rather Z. A. (2020). “Swarm intelligence based autonomous energy-efficient routing protocol for underwater wireless sensor networks,” J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput., vol. 11, pp. 6507–6524.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen J., Zhou Z., Karunakaran V., and Zhao S. (2020). “An efficient technique‐based distributed energy management for hybrid MG system: A hybrid QOCSOS‐RF technique,” Wind. Energy, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 575–592.10.1002/we.2443Suche in Google Scholar

Daissaoui A., Boulmakoul A., Karim L., and Lbath A. (2020). “IoT and big data analytics for smart buildings: A survey,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 170, pp. 161–168.10.1016/j.procs.2020.03.021Suche in Google Scholar

Dave B., Kubler S., Främling K., and Koskela L. (2020). “Opportunities for enhanced lean construction management using Internet of Things standards,” Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun., vol. 61, pp. 86–97.10.1016/j.autcon.2015.10.009Suche in Google Scholar

Dharmadhikari S. C., Gampala V., Rao C. M., Khasim S., Jain S., and Bhaskaran R. (2021). “A smart grid incorporated with ML and IoT for a security management system,” Microprocess. Microsyst., vol. 83, p. 103954.10.1016/j.micpro.2021.103954Suche in Google Scholar

Divina F., Garcia Torres M., Goméz Vela F. A., and Vazquez Noguera J. L. (2019). “A comparative study of time series forecasting methods for short-term electric energy consumption prediction in smart buildings,” Energies, vol. 12, p. 1934.10.3390/en12101934Suche in Google Scholar

Dong B., Prakash V., Feng F., and O’Neill Z. (2019). “A review of a smart building sensing system for better indoor environment control,” Energy Build, vol. 199, pp. 29–46.10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.06.025Suche in Google Scholar

Dos Santos D. R., Dagrada M., and Costante E. (2021). “Leveraging operational technology and the Internet of things to attack smart buildings,” J. Computer Virology Hacking Tech., vol. 17, pp. 1–20.10.1007/s11416-020-00358-8Suche in Google Scholar

Eini R., Linkous L., Zohrabi N., and Abdelwahed S. (2021). “Smart building management system: Performance specifications and design requirements,” J. Build. Eng., vol. 39, p. 102222.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102222Suche in Google Scholar

Eisen M. and Ribeiro A. (2020). “Optimal wireless resource allocation with random edge graph neural networks,” IEEE Trans. Signal. Process., vol. 68, pp. 2977–2991.10.1109/TSP.2020.2988255Suche in Google Scholar

Farao A., Veroni E., Ntantogian C., and Xenakis C. (2021). “P4G2Go: A Privacy-Preserving Scheme for Roaming Energy Consumers of the Smart Grid-to-Go,” Sensors, vol. 21, p. 2686.10.3390/s21082686Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Farzaneh H., Malehmirchegini L., Bejan A., Afolabi T., Mulumba A., and Daka P. P. (2021). “Artificial intelligence evolution in smart buildings for energy efficiency,” Appl. Sci., vol. 11, p. 763.10.3390/app11020763Suche in Google Scholar

Ghorbanian M., Dolatabadi S. H., Siano P., Kouveliotis-Lysikatos A., Akhavan P., and Niknam T. (2021). “Design and operation of a sustainable energy hub in smart cities considering demand response programs and interconnection of different energy carriers,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 278, p. 123854.Suche in Google Scholar

Ghosh T. and Saha S. (2021). “Real-time dynamic price prediction and optimal energy management for microgrid operation with renewable energy integration,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform., vol. 17, pp. 525–535.Suche in Google Scholar

Gomez-Quiles C. and Valdivieso-Sarabia R. (2019). “A time-based scheduling model for energy consumption optimization in residential buildings,” Energies, vol. 12, p. 1495.Suche in Google Scholar

Guo B., Wu D., Ma M., Zhou X., and Yu N. (2020). “A comprehensive review on demand response in smart grids: Opportunities and challenges,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 252, p. 119848.Suche in Google Scholar

Haider M. A., Banej M. R., Alahakoon D., Padmal M., and Dassanayake P. R. (2021). “A novel approach to prediction and classification in smart building: Case study on IOT-based sensor data,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 18654–18667.Suche in Google Scholar

Hammad M., Kamel N., Ghany A., El-Derini M., and Amer A. (2021). “A decentralized and privacy-preserving energy management system for demand-side flexibility in smart homes,” Sensors, vol. 21, p. 1301.Suche in Google Scholar

Hassan M. F., Rostamzadeh M., Moradi P., Soni R., Kalash M., and Shukla S. (2021). “Fog computing in smart buildings: Architectures, applications, and research directions,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform., vol. 17, pp. 4003–4011.Suche in Google Scholar

Hossain M. and Fotouhi H. (2020). “A comprehensive review of cybersecurity in smart grid technology,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 34917–34939.Suche in Google Scholar

Huang Z. and Liu X. (2019). “A distributed hierarchical control strategy for large-scale islanded microgrids based on a dual-layer architecture,” Energies, vol. 12, p. 212.Suche in Google Scholar

Hussain I., Hussain S., and Bilal S. M. (2021). “A novel deep learning algorithm for efficient energy management in a smart building,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 32793–32803.Suche in Google Scholar

Jakkala K., Tripathi N., and Gupta D. (2020). “Integrated demand response and dynamic pricing in the smart grid: A survey,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 52, p. 101873.Suche in Google Scholar

Jayaraman P. P., Sivanandam S. N., and Senthil S. (2021). “IoT-based smart home automation for real-time energy consumption monitoring and optimization,” Procedia Comput. Sci., vol. 183, pp. 420–427.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang L., Zhang H., Yu H., Ma D., and Sun J. (2019). “Multi-Objective energy management for grid-connected microgrid based on improved moth-flame optimization,” Sustainability, vol. 11, p. 189.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaddoum G., Nasir Q., Yuan S., Iqbal N., and Jee S. (2021). “Blockchain-based energy sharing in a smart community: A reinforcement learning approach,” Sustainability, vol. 13, p. 1771.Suche in Google Scholar

Karim M. A., Lee H. J., and Yoo S. H. (2020). “A survey of energy-efficient communication protocols in smart homes for smart grid applications,” Energies, vol. 13, p. 2138.Suche in Google Scholar

Khademi S., Siano P., Tahersima F., Akhavan P., and Niknam T. (2021). “A novel hybrid approach based on meta-heuristic and deep learning for smart grid economic dispatch problem,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 278, p. 123726.Suche in Google Scholar

Khedkar P., Daware S., and Malvi S. (2021). “An improved LCA framework for sustainability assessment of smart grid implementation,” Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess., vol. 43, p. 101188.Suche in Google Scholar

Kim M. J., An K. J., and Ahn H. S. (2021). “Optimal scheduling of smart home appliances with a probability of system uncertainty in real-time,” Energies, vol. 14, p. 672.Suche in Google Scholar

Koh S. S., Kim D. W., and Ryu K. R. (2020). “A secure and energy-efficient data aggregation scheme for industrial wireless sensor networks,” Energies, vol. 13, p. 5922.Suche in Google Scholar

Kong Y., Han Z., Miao Y., and Wang X. (2019). “A reliable microgrid energy management system based on model predictive control and convex optimization,” Energies, vol. 12, p. 4162.Suche in Google Scholar

Krishna Rao C., Sahoo S. K., and Yanine F. F. (2023). “An IoT-based intelligent smart energy monitoring system for solar PV power generation,” in Energy Harvest Syst, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 2733.10.1515/ehs-2023-0015Suche in Google Scholar