Abstract

In this article, the inverse time problem is investigated. Regarding the ill-posed linear problem, utilize the quasi-reversibility method first. This problem has been regularized and after that provides an iterative regularizing strategy for noisy input data that are based on homotopy. For the regularizing solution, the error analysis is proved when we employ noisy measurement data as our initial guess. Finally, numerical implementations are presented.

1 Introduction

Take into consideration the issue of determining the temperature for a positive real number

where

However, across several engineering disciplines like archeology and environmental science, we must take into consideration the “backward problem.” Instead of giving the initial state

However, the homotopy analysis method (HAM) has recently been offered as a way to iteratively address various PDE problems, as evidenced in few studies [14–17]. Demonstrating strong results in resolving numerous engineering issues, both the functional characterizing the problem and the artificially induced homotopy transform have a significant impact on the convergence at

In this article, we proposed a scheme based on the homotopy iteration to specify

Due to the ill-posedness and for overcoming this difficulty, we regularize to approximate problem (1.3) with the quasi-reversibility method, then we reconstruct HAM for the new regularizing problem. Finally, we obtain error estimates on the approximate solution.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: in Section 2, we reconstruct HAM after the quasi-reversibility of problem (1.3). In Section 3, we utilize this iteration approach with noisy data

2 Homotopy scheme and iteration process for quasi-reversibility problem

Quasi-reversibility method is a regularization idea for analysing the stability of different ill-posed problems (see [4] and the references cited therein). In this section, we approximate the issue using quasi-reversibility method to approximate Eq. (1.3) as follows [4]:

where

and

As a power series, we explicitly extend the function

We specify the linear homogeneous operator in terms of

Utilizing

where

i.e.

It is important to note that the auxiliary linear operator

We take

Subsequently, an iteration strategy for obtaining the exact solution

From Eq. (2.8), we obtain

For

where

where

and

We remark that for more information, see [22].

Denote by

We can obtain all eigenvalues

We make the assumption that

Hence, we define

where the functions

Therefore, we have

Eqs. (2.17) and (2.14) imply that

It can now be verified directly that Eqs. (2.16) and (2.18) provide the solution of Eq. (2.15) as follows:

We consider the following problem:

and the following definitions

and

and by combining Eqs. (2.12) and (2.20), we obtain

Finally,

where

On the other hand, we obtain

Therefore, we write

because obviously

In the following, we investigate the convergence and error bound for this scheme.

Theorem 2.1

Assume that

where

Proof

Assume that

where

where

Hence, the proof is completed.□

3 Quasi-reversibility method and discrete mollification using Bernstein basis for noisy input data with convergence analysis

In this section, we use the result of discretization of mollification technique [1,23,24] based on polynomials with Bernstein basis [25]. The discrete mollification method’s fundamental concepts are presented in the studies by Coles and Murio [26] and Bodaghi et al. [25].

We first truncate and define Mth-order approximation of

Then, we use

The MNth-order approximate sequence

where

We derive the error analysis based on this estimate for Eq. (2.1).

Theorem 3.1

Suppose that

Proof

Suppose

In the above inequality, we use the result obtained by Bodaghi et al. [25] about discrete mollification using Bernstein basis polynomial. If we use Parseval equality, then we have

If

where

Hence, we write

with substituting

In view of

Now for the hard part: using Theorems 3.3 and 3.4 of [4] and Theorem 2.1, with some tedious manipulation, yields

The error of

4 Algorithm of BPHAM

First, as proposed by Rahimi and Rostamy [21], we divide the interval into equal sub-intervals. So, for each sub-interval, we regularize the data using the mollification method with the Bernstein basis. Then, we use the homotopy method for the inverse problem. In this article, the idea of this scheme is a successive substitution method. We continue this iteration until we reach the approximate value of the solution at the zero point. Furthermore, in this article, we first regularize the heat problem using the quasi-reversibility method, then we regularize the noisy discrete data with the discrete mollification technique based on polynomials in the Bernstein basis, and finally, we use HAM to solve the new issue.

BPHAM is a novel of hybrid regularization on backward piecewise HAM for ill-posed problems [21]. The algorithm of BPHAM is as follows:

Step 1. Let the spatial and time discretization parameters be

Step 2. Using discrete mollification by Bernstein basis to filter the noisy data for

Step 3. Using the MNth-order of the HAM and its iteration process with

Step 4. Set

In next section, we compare the results of our scheme in this article with the results of the BPHAM method [21].

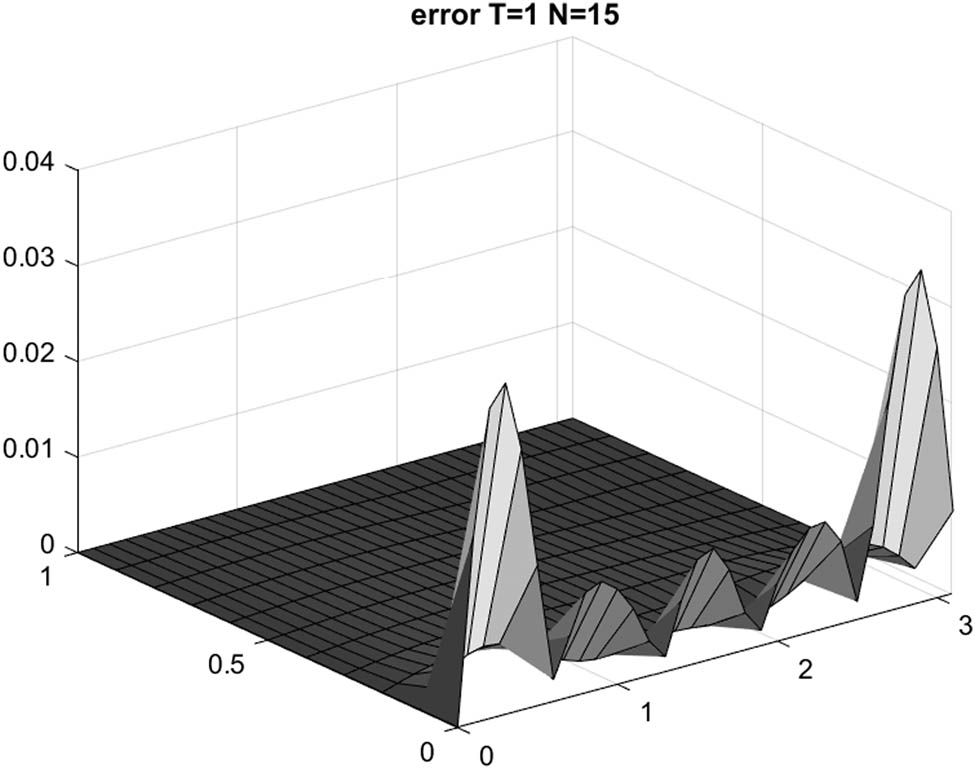

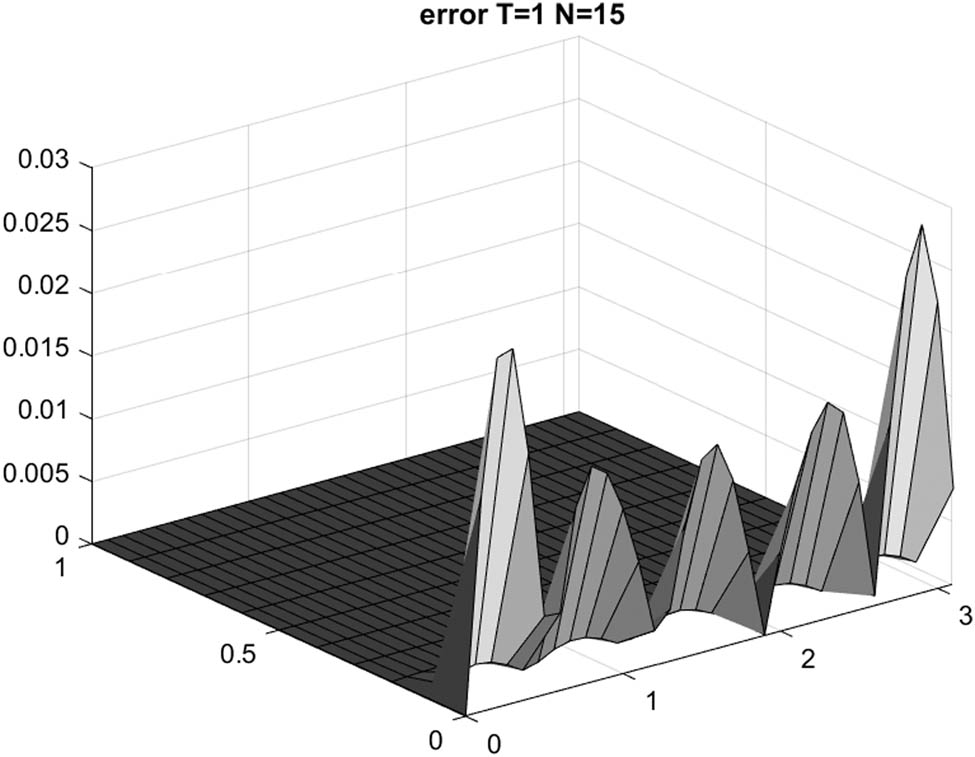

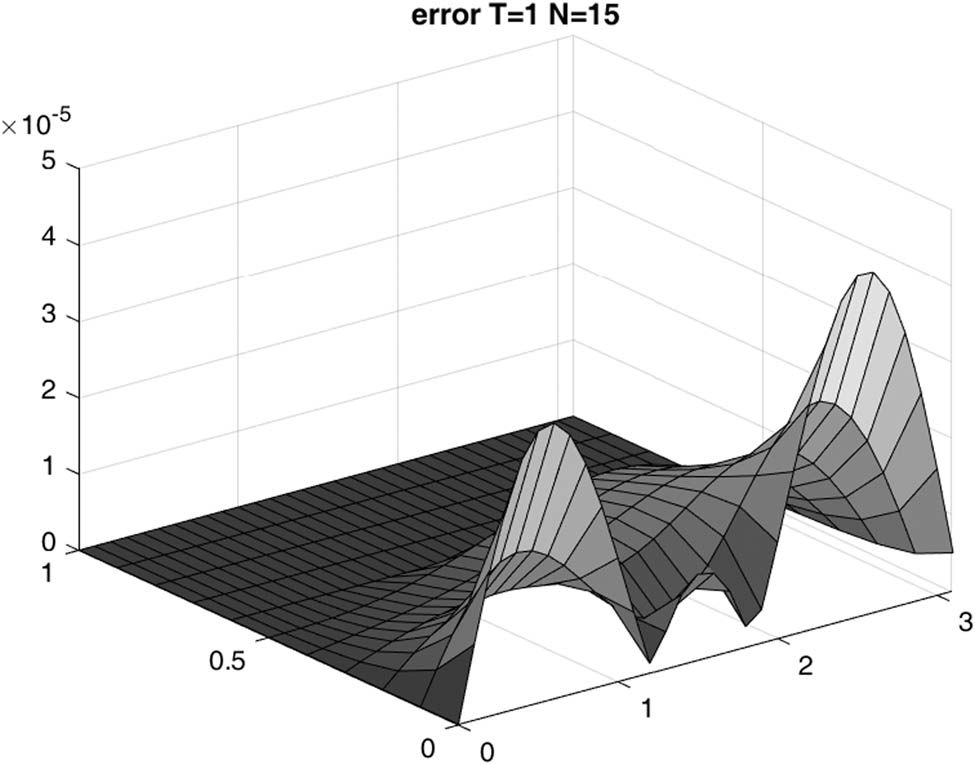

5 Numerical examples

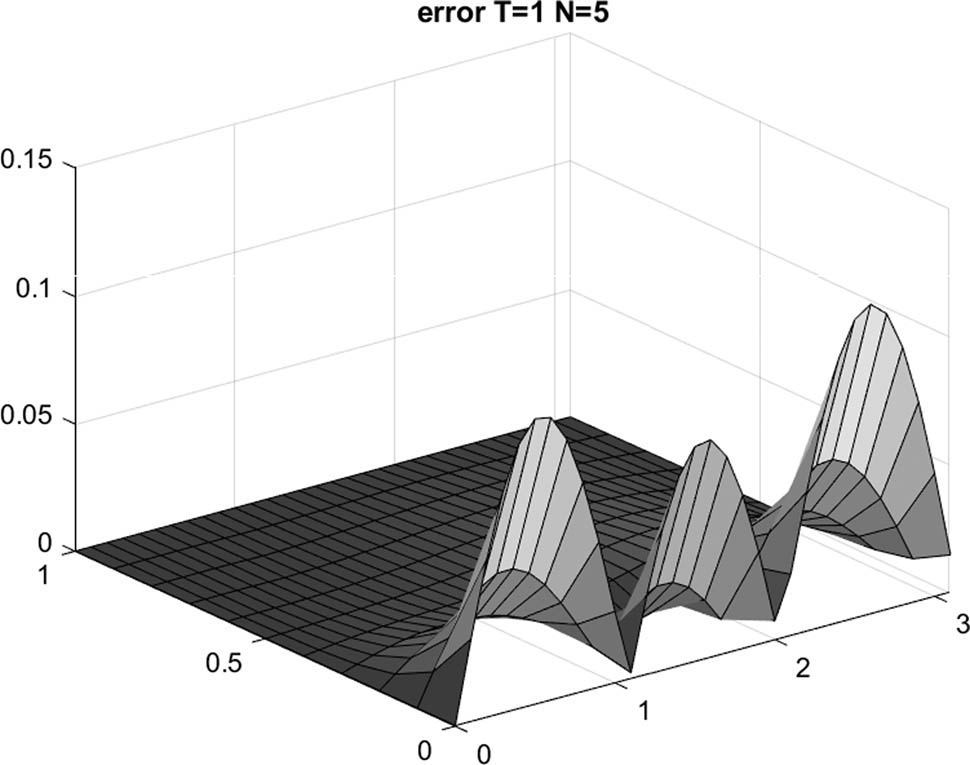

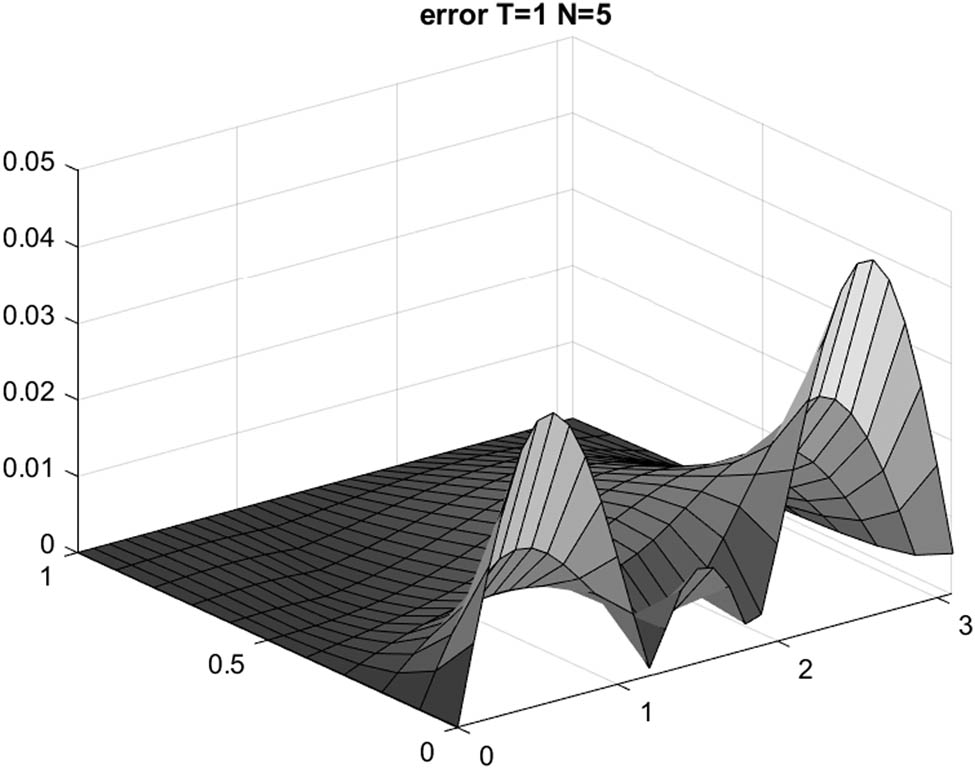

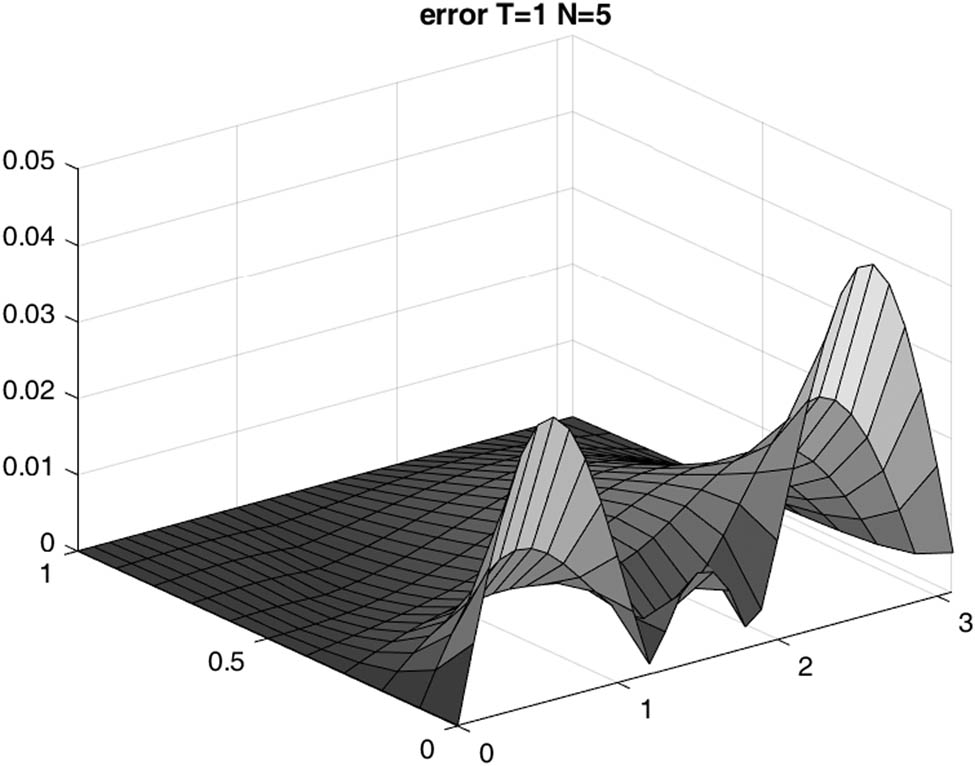

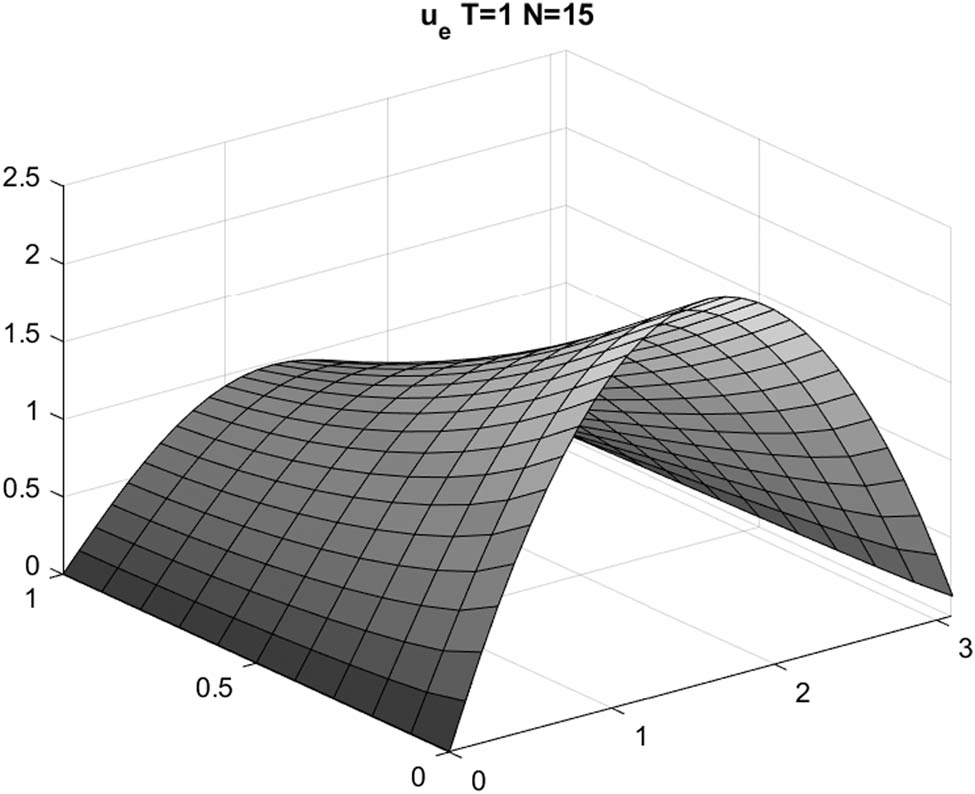

We provide two numerical examples in this part to demonstrate the difference between our suggested approach and BPHAM [21]. The required CPU times to run the program will be presented. We perform our computations using Matlab 2017 software on a Core i5, 2:67 GHz CPU machine with 8 GB of memory. As an illustration, the simulation of noisy discrete data function for the boundary function is described subsequently.

The normal distribution

The discretization parameters are always as follows.

If we consider that

Example 1. We consider an example with

where

Our reconstruction of

Example 1:

Example 1:

Example 1:

Example 1 :

|

|

|

|

BPHAM method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 0.0008493 | 0.00089405 | 0.0008945 |

| 0.8 | 0.0035283 | 0.0036101 | 0.003616 |

| 0.55 | 0.0082616 | 0.0083079 | 0.0083084 |

| 0.30 | 0.016906 | 0.013106 | 0.013268 |

| 0.05 | 0.078309 | 0.032745 | 0.034288 |

|

|

|

|

BPHAM method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 0.00011643 |

|

|

| 0.8 | 0.00033718 |

|

|

| 0.55 | 0.00063062 |

|

|

| 0.30 | 0.0039046 |

|

|

| 0.05 | 0.045473 | 0.0005052 |

|

Example 2. Suppose

Then, the forward problem (1.3) together with Theorem 2.1 yields the noisy inversion input data as follows:

We suppose the input data with

Example 2:

Example 2:

Example 2:

Example 2:

|

|

|

|

BPHAM method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 0.0017454 | 0.0017624 | 0.0017626 |

| 0.8 | 0.0074165 | 0.0073405 | 0.00737 |

| 0.55 | 0.18488 | 0.018038 | 0.018034 |

| 0.30 | 0.031817 | 0.030852 | 0.30843 |

| 0.05 | 0.045806 | 0.036219 | 0.046224 |

|

|

|

|

BPHAM method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.95 | 0.00013386 |

|

|

| 0.8 | 0.00041076 |

|

|

| 0.55 | 0.000774 |

|

|

| 0.30 | 0.0011935 |

|

|

| 0.05 | 0.0049727 | 0.000056312 | 0.00062064 |

6 Conclusion and remarks

In this article, we proposed a hybrid of numerical schemes for the inverse time problem. This advanced method is equipped with the quasi-reversibility method and after that provides an iterative regularizing strategy for noisy input data that is based on homotopy. This combined method of progress along with mathematical analysis presents important and new theorems regarding error analysis in this field, which achieves very good results compared to other research. Numerical results are also available from this issue. The numerical examples illustrate that using regularization methods can improve the quality of the computed approximate solution. It is also possible to solve the nonlinear inverse equation using the proposed method, but due to the scope and complexity of this research, we will discuss this issue in future works. This article will be a new beginning in the change and evolution of homotopy analysis in inverse problems. Regarding the nonlinearity of the problem, we note that a linearization technique is needed. Because of the long discussion, this issue is being investigated, and the results will be presented in the future. On the other hand, our emphasis is on the one-dimensional problem, and all the analysis of the explained method can be implemented in the two-dimensional mode as well. The convergence of the method is shown pointwise according to the numerical results and Theorem 3.1. But the theory of the optimal error analysis must be improved for this method.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments, which helped to improve the article.

-

Funding information: We have no financial resources.

-

Author contributions: The authors contributed to the design and implementation of the research, analysis of the results, and writing of the manuscript and also they discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no competing interests in this article. This research work is not affiliated with any private or military institution, and no material benefits have been received in this study.

-

Data availability statement: Data are available on request from the authors.

References

[1] Denche M, Bessila K. A modified quasi-boundary value for ill-posed problems. J Math Anal Appl. 2005;301:419–26. 10.1016/j.jmaa.2004.08.001Search in Google Scholar

[2] Huang Y, Zheng Q. Regularization for a class of ill-posed Cauchy problems. Proc Am Math Soc. 2005;133(10):3005–12. 10.1090/S0002-9939-05-07822-6Search in Google Scholar

[3] Huang Y, Quan Z. Regularization for ill-posed Cauchy problems associated with generators of analytic semigroups. J Differ Equ. 2004;203(1):38–54. 10.1016/j.jde.2004.03.035Search in Google Scholar

[4] Dang D, Nguyen HT. Regularization and error estimates for nonhomogeneous backward heat problem. Electr J Differ Equ. 20062006;4:1–10. Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chen Q, Liu JJ. Solving the backward heat conduction problem by data fitting with multiple regularizing parameters. J Comput Math. 2012;30(4):418–32. 10.4208/jcm.1111-m3457Search in Google Scholar

[6] Asl NA, Rostamy D. Identifying an unknown time-dependent boundary source in time-fractional diffusion equation with a non-local boundary condition. J Comput Appl Math. 2019;355:36–50. 10.1016/j.cam.2019.01.018Search in Google Scholar

[7] Mel’nikova IV. Regularization of ill-posed differential problems. Sib Math J. 1992;33:289–98. 10.1007/BF00971100Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lattes R, Lions JL. Method de quasi-reversibility et applications. Paris, France: Dunod; 1967 (English translation Bellman R. New York (NY), USA: Elsevier; 1969). Search in Google Scholar

[9] Miller K. Stabilished quasi-reversibility and other near possible methods for non-well-posed problems. In: Knops RJ, editor. Symposium on Non Well-posed Problems and Logarithmic Convexity, Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Vol. 3. Berlin Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1973. p. 161–76. 10.1007/BFb0069627Search in Google Scholar

[10] Qian Z, Fu CL, Shi R. A modified method for a backward heat conduction problem. Appl Math Comput. 2007;185:564–73. 10.1016/j.amc.2006.07.055Search in Google Scholar

[11] Qian Z, Fu CL, Feng XL. A modified method for high order numerical derivatives. Appl Math Comput. 2006;182:1191–200. 10.1016/j.amc.2006.04.059Search in Google Scholar

[12] Qian Z, Fu CL, Xiong XT. A modified for determining the surface heat flux of IHCP. Inverse Prob Sci Eng. 2007;15:249–65. 10.1080/17415970600725128Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yang F, Fu CL. Two regularization methods for identification of the heat source depending only on spatial variable for the heat equation. J Inv Ill-posed Prob. 2009;17:1–16. 10.1515/JIIP.2009.048Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rostamy D, Karimi K. Hypercomplex mathematics and HPM for the time-delayed Burgers equation with convergence analysis. Numer Algorithms. 2011;58:85–101. 10.1007/s11075-011-9448-7Search in Google Scholar

[15] Abbasbandy S. The application of homotopy analysis method to nonlinear equations arising in heat transfer. Phys Lett A. 2006;36:109–13. 10.1016/j.physleta.2006.07.065Search in Google Scholar

[16] Liao SJ. On the homotopy analysis method for nonlinear problems. Appl Math Comput. 2004;147:499–513. 10.1016/S0096-3003(02)00790-7Search in Google Scholar

[17] Park SH, Kim JH. Homotopy analysis method for option pricing under stochastic volatility. Appl Math Lett. 2011;24:1740–4. 10.1016/j.aml.2011.04.034Search in Google Scholar

[18] Liao SJ. Notes on the homotopy analysis method: some definitions and theorems. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2009;14:983–97. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2008.04.013Search in Google Scholar

[19] Shidfar A, Molabahrami A. A weighted algorithm based on the homotopy analysis method; application to inverse heat conduction problem. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Siml. 2010;15:2908–15. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2009.11.011Search in Google Scholar

[20] Watson LT, Haftka RT. Modern homotopy methods in optimization. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 1989;74:289–305. 10.1016/0045-7825(89)90053-4Search in Google Scholar

[21] Rahimi M, Rostamy D. A novel of hybrid regularization on backward piecewise homotopy analysis method for ill-posed problems. J Math. 2023. (in press)Search in Google Scholar

[22] Liu J, Wang B. Solving the backward heat conduction problem by homotopy analysis method. Appl Numer Math. 2018;128:84–97. 10.1016/j.apnum.2018.02.002Search in Google Scholar

[23] Liao SJ. Beyond perturbation. Introduction to the homotopy analysis method. Boca Raton (FL), USA: Chapman Hall/CRC Press; 2003. Search in Google Scholar

[24] Murio DA. Mollification and space marching. In: Woodburg K, editor. Inverse engineering handbook. Boca Raton (FL), USA: CRC Press, 2002. 10.1201/9781420041613.ch4Search in Google Scholar

[25] Bodaghi S, Zakeri A, Amiraslani A. A numerical scheme based on discrete mollification method using Bernstein basis polynomials for solving the inverse one-dimensional Stefan problem. Inverse Problems Sci Eng. 2020;28(11):1528–50. 10.1080/17415977.2020.1733996Search in Google Scholar

[26] Coles C, Murio DA. Identification of parameters in the 2-D IHCP. Comput Math Appl. 2000;40:939–56. 10.1016/S0898-1221(00)85005-1Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The regularization of spectral methods for hyperbolic Volterra integrodifferential equations with fractional power elliptic operator

- Analytical and numerical study for the generalized q-deformed sinh-Gordon equation

- Dynamics and attitude control of space-based synthetic aperture radar

- A new optimal multistep optimal homotopy asymptotic method to solve nonlinear system of two biological species

- Dynamical aspects of transient electro-osmotic flow of Burgers' fluid with zeta potential in cylindrical tube

- Self-optimization examination system based on improved particle swarm optimization

- Overlapping grid SQLM for third-grade modified nanofluid flow deformed by porous stretchable/shrinkable Riga plate

- Research on indoor localization algorithm based on time unsynchronization

- Performance evaluation and optimization of fixture adapter for oil drilling top drives

- Nonlinear adaptive sliding mode control with application to quadcopters

- Numerical simulation of Burgers’ equations via quartic HB-spline DQM

- Bond performance between recycled concrete and steel bar after high temperature

- Deformable Laplace transform and its applications

- A comparative study for the numerical approximation of 1D and 2D hyperbolic telegraph equations with UAT and UAH tension B-spline DQM

- Numerical approximations of CNLS equations via UAH tension B-spline DQM

- Nonlinear numerical simulation of bond performance between recycled concrete and corroded steel bars

- An iterative approach using Sawi transform for fractional telegraph equation in diversified dimensions

- Investigation of magnetized convection for second-grade nanofluids via Prabhakar differentiation

- Influence of the blade size on the dynamic characteristic damage identification of wind turbine blades

- Cilia and electroosmosis induced double diffusive transport of hybrid nanofluids through microchannel and entropy analysis

- Semi-analytical approximation of time-fractional telegraph equation via natural transform in Caputo derivative

- Analytical solutions of fractional couple stress fluid flow for an engineering problem

- Simulations of fractional time-derivative against proportional time-delay for solving and investigating the generalized perturbed-KdV equation

- Pricing weather derivatives in an uncertain environment

- Variational principles for a double Rayleigh beam system undergoing vibrations and connected by a nonlinear Winkler–Pasternak elastic layer

- Novel soliton structures of truncated M-fractional (4+1)-dim Fokas wave model

- Safety decision analysis of collapse accident based on “accident tree–analytic hierarchy process”

- Derivation of septic B-spline function in n-dimensional to solve n-dimensional partial differential equations

- Development of a gray box system identification model to estimate the parameters affecting traffic accidents

- Homotopy analysis method for discrete quasi-reversibility mollification method of nonhomogeneous backward heat conduction problem

- New kink-periodic and convex–concave-periodic solutions to the modified regularized long wave equation by means of modified rational trigonometric–hyperbolic functions

- Explicit Chebyshev Petrov–Galerkin scheme for time-fractional fourth-order uniform Euler–Bernoulli pinned–pinned beam equation

- NASA DART mission: A preliminary mathematical dynamical model and its nonlinear circuit emulation

- Nonlinear dynamic responses of ballasted railway tracks using concrete sleepers incorporated with reinforced fibres and pre-treated crumb rubber

- Two-component excitation governance of giant wave clusters with the partially nonlocal nonlinearity

- Bifurcation analysis and control of the valve-controlled hydraulic cylinder system

- Engineering fault intelligent monitoring system based on Internet of Things and GIS

- Traveling wave solutions of the generalized scale-invariant analog of the KdV equation by tanh–coth method

- Electric vehicle wireless charging system for the foreign object detection with the inducted coil with magnetic field variation

- Dynamical structures of wave front to the fractional generalized equal width-Burgers model via two analytic schemes: Effects of parameters and fractionality

- Theoretical and numerical analysis of nonlinear Boussinesq equation under fractal fractional derivative

- Research on the artificial control method of the gas nuclei spectrum in the small-scale experimental pool under atmospheric pressure

- Mathematical analysis of the transmission dynamics of viral infection with effective control policies via fractional derivative

- On duality principles and related convex dual formulations suitable for local and global non-convex variational optimization

- Study on the breaking characteristics of glass-like brittle materials

- The construction and development of economic education model in universities based on the spatial Durbin model

- Homoclinic breather, periodic wave, lump solution, and M-shaped rational solutions for cold bosonic atoms in a zig-zag optical lattice

- Fractional insights into Zika virus transmission: Exploring preventive measures from a dynamical perspective

- Rapid Communication

- Influence of joint flexibility on buckling analysis of free–free beams

- Special Issue: Recent trends and emergence of technology in nonlinear engineering and its applications - Part II

- Research on optimization of crane fault predictive control system based on data mining

- Nonlinear computer image scene and target information extraction based on big data technology

- Nonlinear analysis and processing of software development data under Internet of things monitoring system

- Nonlinear remote monitoring system of manipulator based on network communication technology

- Nonlinear bridge deflection monitoring and prediction system based on network communication

- Cross-modal multi-label image classification modeling and recognition based on nonlinear

- Application of nonlinear clustering optimization algorithm in web data mining of cloud computing

- Optimization of information acquisition security of broadband carrier communication based on linear equation

- A review of tiger conservation studies using nonlinear trajectory: A telemetry data approach

- Multiwireless sensors for electrical measurement based on nonlinear improved data fusion algorithm

- Realization of optimization design of electromechanical integration PLC program system based on 3D model

- Research on nonlinear tracking and evaluation of sports 3D vision action

- Analysis of bridge vibration response for identification of bridge damage using BP neural network

- Numerical analysis of vibration response of elastic tube bundle of heat exchanger based on fluid structure coupling analysis

- Establishment of nonlinear network security situational awareness model based on random forest under the background of big data

- Research and implementation of non-linear management and monitoring system for classified information network

- Study of time-fractional delayed differential equations via new integral transform-based variation iteration technique

- Exhaustive study on post effect processing of 3D image based on nonlinear digital watermarking algorithm

- A versatile dynamic noise control framework based on computer simulation and modeling

- A novel hybrid ensemble convolutional neural network for face recognition by optimizing hyperparameters

- Numerical analysis of uneven settlement of highway subgrade based on nonlinear algorithm

- Experimental design and data analysis and optimization of mechanical condition diagnosis for transformer sets

- Special Issue: Reliable and Robust Fuzzy Logic Control System for Industry 4.0

- Framework for identifying network attacks through packet inspection using machine learning

- Convolutional neural network for UAV image processing and navigation in tree plantations based on deep learning

- Analysis of multimedia technology and mobile learning in English teaching in colleges and universities

- A deep learning-based mathematical modeling strategy for classifying musical genres in musical industry

- An effective framework to improve the managerial activities in global software development

- Simulation of three-dimensional temperature field in high-frequency welding based on nonlinear finite element method

- Multi-objective optimization model of transmission error of nonlinear dynamic load of double helical gears

- Fault diagnosis of electrical equipment based on virtual simulation technology

- Application of fractional-order nonlinear equations in coordinated control of multi-agent systems

- Research on railroad locomotive driving safety assistance technology based on electromechanical coupling analysis

- Risk assessment of computer network information using a proposed approach: Fuzzy hierarchical reasoning model based on scientific inversion parallel programming

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part I

- The application of iterative hard threshold algorithm based on nonlinear optimal compression sensing and electronic information technology in the field of automatic control

- Equilibrium stability of dynamic duopoly Cournot game under heterogeneous strategies, asymmetric information, and one-way R&D spillovers

- Mathematical prediction model construction of network packet loss rate and nonlinear mapping user experience under the Internet of Things

- Target recognition and detection system based on sensor and nonlinear machine vision fusion

- Risk analysis of bridge ship collision based on AIS data model and nonlinear finite element

- Video face target detection and tracking algorithm based on nonlinear sequence Monte Carlo filtering technique

- Adaptive fuzzy extended state observer for a class of nonlinear systems with output constraint

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The regularization of spectral methods for hyperbolic Volterra integrodifferential equations with fractional power elliptic operator

- Analytical and numerical study for the generalized q-deformed sinh-Gordon equation

- Dynamics and attitude control of space-based synthetic aperture radar

- A new optimal multistep optimal homotopy asymptotic method to solve nonlinear system of two biological species

- Dynamical aspects of transient electro-osmotic flow of Burgers' fluid with zeta potential in cylindrical tube

- Self-optimization examination system based on improved particle swarm optimization

- Overlapping grid SQLM for third-grade modified nanofluid flow deformed by porous stretchable/shrinkable Riga plate

- Research on indoor localization algorithm based on time unsynchronization

- Performance evaluation and optimization of fixture adapter for oil drilling top drives

- Nonlinear adaptive sliding mode control with application to quadcopters

- Numerical simulation of Burgers’ equations via quartic HB-spline DQM

- Bond performance between recycled concrete and steel bar after high temperature

- Deformable Laplace transform and its applications

- A comparative study for the numerical approximation of 1D and 2D hyperbolic telegraph equations with UAT and UAH tension B-spline DQM

- Numerical approximations of CNLS equations via UAH tension B-spline DQM

- Nonlinear numerical simulation of bond performance between recycled concrete and corroded steel bars

- An iterative approach using Sawi transform for fractional telegraph equation in diversified dimensions

- Investigation of magnetized convection for second-grade nanofluids via Prabhakar differentiation

- Influence of the blade size on the dynamic characteristic damage identification of wind turbine blades

- Cilia and electroosmosis induced double diffusive transport of hybrid nanofluids through microchannel and entropy analysis

- Semi-analytical approximation of time-fractional telegraph equation via natural transform in Caputo derivative

- Analytical solutions of fractional couple stress fluid flow for an engineering problem

- Simulations of fractional time-derivative against proportional time-delay for solving and investigating the generalized perturbed-KdV equation

- Pricing weather derivatives in an uncertain environment

- Variational principles for a double Rayleigh beam system undergoing vibrations and connected by a nonlinear Winkler–Pasternak elastic layer

- Novel soliton structures of truncated M-fractional (4+1)-dim Fokas wave model

- Safety decision analysis of collapse accident based on “accident tree–analytic hierarchy process”

- Derivation of septic B-spline function in n-dimensional to solve n-dimensional partial differential equations

- Development of a gray box system identification model to estimate the parameters affecting traffic accidents

- Homotopy analysis method for discrete quasi-reversibility mollification method of nonhomogeneous backward heat conduction problem

- New kink-periodic and convex–concave-periodic solutions to the modified regularized long wave equation by means of modified rational trigonometric–hyperbolic functions

- Explicit Chebyshev Petrov–Galerkin scheme for time-fractional fourth-order uniform Euler–Bernoulli pinned–pinned beam equation

- NASA DART mission: A preliminary mathematical dynamical model and its nonlinear circuit emulation

- Nonlinear dynamic responses of ballasted railway tracks using concrete sleepers incorporated with reinforced fibres and pre-treated crumb rubber

- Two-component excitation governance of giant wave clusters with the partially nonlocal nonlinearity

- Bifurcation analysis and control of the valve-controlled hydraulic cylinder system

- Engineering fault intelligent monitoring system based on Internet of Things and GIS

- Traveling wave solutions of the generalized scale-invariant analog of the KdV equation by tanh–coth method

- Electric vehicle wireless charging system for the foreign object detection with the inducted coil with magnetic field variation

- Dynamical structures of wave front to the fractional generalized equal width-Burgers model via two analytic schemes: Effects of parameters and fractionality

- Theoretical and numerical analysis of nonlinear Boussinesq equation under fractal fractional derivative

- Research on the artificial control method of the gas nuclei spectrum in the small-scale experimental pool under atmospheric pressure

- Mathematical analysis of the transmission dynamics of viral infection with effective control policies via fractional derivative

- On duality principles and related convex dual formulations suitable for local and global non-convex variational optimization

- Study on the breaking characteristics of glass-like brittle materials

- The construction and development of economic education model in universities based on the spatial Durbin model

- Homoclinic breather, periodic wave, lump solution, and M-shaped rational solutions for cold bosonic atoms in a zig-zag optical lattice

- Fractional insights into Zika virus transmission: Exploring preventive measures from a dynamical perspective

- Rapid Communication

- Influence of joint flexibility on buckling analysis of free–free beams

- Special Issue: Recent trends and emergence of technology in nonlinear engineering and its applications - Part II

- Research on optimization of crane fault predictive control system based on data mining

- Nonlinear computer image scene and target information extraction based on big data technology

- Nonlinear analysis and processing of software development data under Internet of things monitoring system

- Nonlinear remote monitoring system of manipulator based on network communication technology

- Nonlinear bridge deflection monitoring and prediction system based on network communication

- Cross-modal multi-label image classification modeling and recognition based on nonlinear

- Application of nonlinear clustering optimization algorithm in web data mining of cloud computing

- Optimization of information acquisition security of broadband carrier communication based on linear equation

- A review of tiger conservation studies using nonlinear trajectory: A telemetry data approach

- Multiwireless sensors for electrical measurement based on nonlinear improved data fusion algorithm

- Realization of optimization design of electromechanical integration PLC program system based on 3D model

- Research on nonlinear tracking and evaluation of sports 3D vision action

- Analysis of bridge vibration response for identification of bridge damage using BP neural network

- Numerical analysis of vibration response of elastic tube bundle of heat exchanger based on fluid structure coupling analysis

- Establishment of nonlinear network security situational awareness model based on random forest under the background of big data

- Research and implementation of non-linear management and monitoring system for classified information network

- Study of time-fractional delayed differential equations via new integral transform-based variation iteration technique

- Exhaustive study on post effect processing of 3D image based on nonlinear digital watermarking algorithm

- A versatile dynamic noise control framework based on computer simulation and modeling

- A novel hybrid ensemble convolutional neural network for face recognition by optimizing hyperparameters

- Numerical analysis of uneven settlement of highway subgrade based on nonlinear algorithm

- Experimental design and data analysis and optimization of mechanical condition diagnosis for transformer sets

- Special Issue: Reliable and Robust Fuzzy Logic Control System for Industry 4.0

- Framework for identifying network attacks through packet inspection using machine learning

- Convolutional neural network for UAV image processing and navigation in tree plantations based on deep learning

- Analysis of multimedia technology and mobile learning in English teaching in colleges and universities

- A deep learning-based mathematical modeling strategy for classifying musical genres in musical industry

- An effective framework to improve the managerial activities in global software development

- Simulation of three-dimensional temperature field in high-frequency welding based on nonlinear finite element method

- Multi-objective optimization model of transmission error of nonlinear dynamic load of double helical gears

- Fault diagnosis of electrical equipment based on virtual simulation technology

- Application of fractional-order nonlinear equations in coordinated control of multi-agent systems

- Research on railroad locomotive driving safety assistance technology based on electromechanical coupling analysis

- Risk assessment of computer network information using a proposed approach: Fuzzy hierarchical reasoning model based on scientific inversion parallel programming

- Special Issue: Dynamic Engineering and Control Methods for the Nonlinear Systems - Part I

- The application of iterative hard threshold algorithm based on nonlinear optimal compression sensing and electronic information technology in the field of automatic control

- Equilibrium stability of dynamic duopoly Cournot game under heterogeneous strategies, asymmetric information, and one-way R&D spillovers

- Mathematical prediction model construction of network packet loss rate and nonlinear mapping user experience under the Internet of Things

- Target recognition and detection system based on sensor and nonlinear machine vision fusion

- Risk analysis of bridge ship collision based on AIS data model and nonlinear finite element

- Video face target detection and tracking algorithm based on nonlinear sequence Monte Carlo filtering technique

- Adaptive fuzzy extended state observer for a class of nonlinear systems with output constraint