Abstract

This study, as one of the first in its kind, focuses on code-switching in computer-mediated communication (CMC) among Gen Z Japanese Americans who have been simultaneous bilinguals since childhood. We collected a dataset of 1,561 online text messages that were exchanged between these bilinguals and found intriguing code-switching patterns not typically observed in spontaneous speech nor reported in the literature. First, we find a surprisingly high portion of Japanese usage in the dataset and noticed high occurrences of Japanese auxiliary verbs and low occurrences of Japanese pronouns compared to the English counterparts. The data suggests these bilinguals have a strong grasp of both languages and are actively code-switching to construct their bilingual and bicultural identity over text. Second, our data shows that preferences for a type of code-switching (intra-sentential or inter-sentential) when texting friends are not a reflection of language proficiency or constraints of the CMC medium, but rather reflect the frequency with which the speakers orally code-switch and speak the embedded language at home. Moreover, we observe the speakers’ development of a CMC style of Japanese-English code-switching through using romanized Japanese words, elongating Japanese words using romanization, mixing writing scripts, and writing English words in Japanese characters.

1 Introduction

Code-switching refers to the phenomenon of switching between two or more languages when communicating, and it is argued that bilingual speakers code-switch to express themselves to the fullest (Appel and Muysken 2005). As bilingual speakers increase globally, code-switching has become a more common language phenomenon. In the United States, the percentage of people speaking a language other than English increased from 18 % in 2003 to 21.6 % in 2021 (US Census Bureau 2021). The rise in code-switching has sparked growing research interest, including consideration of the motivations for code-switching and the grammatical patterns of code-switching utterances. Code-switching between languages is not to be confused with temporary lexical borrowing from another language. As clarified by Myers-Scotton (2017), a monolingual person can borrow lexemes from another language, while only bilingual people engage in code-switching. Researchers have observed two main types of code-switching in terms of when the switch occurs: “intra-sentential” code-switching, where language switching happens within a sentence; and “inter-sentential” code-switching, where switching happens between sentences (Milroy and Muysken 1995). Studies have also categorized code-switching by the ratio of the two languages involved: either a host language with occasional embedded language or an even combination of both languages (Nishimura 1995).

With the popularization of social media and online communication tools (such as email and message apps), code-switching in computer-mediated communication (CMC) has become an emerging branch of research. Researchers have reported that code-switching in CMC presents some new linguistic, sociopragmatic, and communicative patterns that have not been previously observed and have argued that code-switching in CMC serves specific new sociolinguistic functions (Androutsopoulos 2007; Lin 2005; Montes-Alcalá 2024; Ting and Yeo 2019; among others).

However, little attention has been given to Japanese-English CMC code-switching, especially in bilingual texting, with most research focusing on oral code-switching data. Nishimura (1995) examined oral code-switching among second-generation Japanese Canadians (known as “Niseis”) from prewar Japanese neighborhoods and found that Niseis spoke primarily in English to fellow Niseis but switched between English and Japanese evenly when speaking to a group of native Japanese speakers and fellow Japanese Canadians. Shepherd (2021) confirmed that Nishimura’s patterns of bilingual speech (the “basically Japanese” pattern, the “basically English” pattern, and the “mixed” pattern) are still being used among contemporary Japanese Americans’ oral communications; however, the postwar second-generation Japanese Americans use primarily English when speaking to a group of native speakers and fellow Japanese Americans. While Nishimura’s and Shepherd’s studies focused on Japanese-English code-switching in English-speaking countries, Azuma (1997) obtained datasets from native Japanese speakers in Japan, including natural conversations among female college students returning from a year abroad at a US university and disk jockeys’ speech on FM radio stations playing American pop music. Azuma argued that significantly more code-switching in disk jockeys’ speech is likely attributable to the prevalence of English songs, but both datasets revealed that nouns, verbal nouns, and adjectivals (referred to as keiyoo-dooshi in Japanese) were the most frequently switched parts of speech. These parts of speech all possess the feature [+N] in Japanese, so they can meaningfully stand alone. In contrast to studies focusing on analyzing specific datasets, Nakayama et al. (2018) described the process of constructing a large-scale Japanese-English oral code-switching corpus. The corpus showed up to 59 code-switching instances within a 30-min audio recording, emphasizing the necessity for speech recognition models to handle both monolingual speech and code-switched speech.

The present study aims to contribute to the emerging study of code-switching in CMC by examining code-switching among Japanese Americans who code-switch between Japanese and English when sending text messages to each other. This study allows us to analyze when bilingual speakers choose to use one language over the other and notice patterns that might not be so obvious in spontaneous oral speech. Code-switching in CMC has been argued to be an identity marker among young persons (Gonzales and Tsang 2023; Lienard and Penloup 2011; Montes-Alcalá 2007). With a focus on CMC code-switching among Gen Z Japanese Americans, the present study can also contribute to the understanding of young persons’ CMC code-switching patterns and reveal insights into language dynamics and cultural identity among young bilingual speakers.

Moreover, the present study enables us to explore CMC code-switching patterns that may not be as apparent in code-switching scenarios within a single language family, where the languages have similar grammatical structure and writing systems (Barasa 2016; Callahan 2004; Estigarribia and Wilkins 2018; Halim and Maros 2014; Leppänen’s 2012; Montes-Alcalá 2005, 2024; Tsiplakou 2009; among others). Japanese, as a non-Indo-European language, has very different grammar from English. For example, Japanese follows a basic word order of subject-object-verb and has an extensive grammatical system for politeness, unlike English. Additionally, also unlike English which only has an alphabetic writing system, Japanese employs a mix of different writing systems: a logographic writing system (kanji), two syllabaries (hiragana and katakana), and a romanized alphabetic writing system (romaji) that has recently developed and is not widely used nor official (Matsuda 2017). Due to the distinct features of writing systems in English and Japanese, the present study can help us investigate the interactions between writing systems and language code-switching, which have barely been reported in the literature.

Before presenting the dataset and analysis, we would like to clarify some terminology-related points. First, we chose “code-switching” over “translanguaging” or “code-mixing” in this paper, although all three terms apply to multilingual data. The speakers in our dataset are aware of the two distinct languages as they message, and they have naturally switched between the languages since childhood. However, translanguaging views languages as integrated into one grammar with a unified set of linguistic features – a unitary grammar (Otheguy et al. 2019). Additionally, translanguaging tends to be widely used in relation to bilingual education contexts (Liu 2023). Thus, we adopted a code-switching framework for this paper. Code-mixing often refers to alternating between languages within a sentence, but code-switching is a broader term covering language switches within and between sentences (Mabule 2015). The second terminology-related point to note is that texting can be a semi-synchronous form of CMC, differing from blogs, emails, and online forums (Androutsopoulos 2013). Although texting is an informal CMC with conversational content like oral communication, it remains in written form. Typing and sending messages requires more deliberation and steps than simply verbalizing thoughts, making it valuable for studying code-switching patterns that may not be apparent in spontaneous speech.

2 Methodology and dataset

The dataset consists of text messages among three young adult female Japanese-English bilinguals (ages 21–22 at the time of data collection). One of the authors is one of the participants, but this author did not have the idea of a study such as this in mind when these messages were exchanged. The three speakers, referred to as speakers A, B, and C, are simultaneous bilinguals fluent in both Japanese and English who have frequently spoken both languages and have resided in the US since childhood (see Table 1). They are friends with overlapping social networks as they are all part of the local Japanese community. They have had regular exposure to both English and Japanese through their community and online media.

Language background of the participants.

| Participant | Language background |

|---|---|

| Speaker A | Speaks primarily Japanese with one parent and English with the other; speaks primarily English with an older sibling; uses mostly English in daily life |

| Speaker B | Speaks primarily Japanese with one parent and English with the other; frequent code-switching with an older sibling; uses both English and Japanese in daily life |

| Speaker C | Speaks primarily Japanese with both parents; speaks primarily Japanese with siblings, only occasionally code-switching with siblings; uses both English and Japanese in daily life |

The 1,561 text messages were extracted from two chat groups. One set consists of direct messages (DMs) exchanged between speaker A and C between 21 August 2022 and 22 February 2023. The other set is from a group chat (GC) among speakers A, B, and C between 9 September 2022 and 20 February 2023. All three speakers gave their informed consent through online communication to allow the text messages to be exported from iMessages on a Mac using the terminal and SQLite commands. After exporting the text messages, the chat data was formatted into a CSV file.

The dataset cleaning involved three steps. First, blank messages, including those resulting from images or pictures, were removed, as visual messages are not directly related to the focus of Japanese-English code-switching. Subsequently, reaction messages such as “liked a message”, “loved a message”, and “emphasized a message” as well as emojis were removed. Lastly, we anonymized identifiable information by deleting social media links and birthdays and anonymizing names and addresses. Table 2 outlines the number of messages removed at each step. After cleaning up the data, there were 1,198 messages across the DMs and the GC. Each text bubble is considered a single message, so each message ranges from a single word to multiple sentences.

Number of messages after each step of the clean-up process.

| Group chat count | Number removed | Direct message count | Number removed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original total | 949 | 612 | ||

| After removing blanks | 928 | 21 | 600 | 12 |

| After removing reactions | 739 | 189 | 520 | 80 |

| After removing links | 710 | 29 | 515 | 5 |

| After manual cleaning | 706 | 4 | 507 | 8 |

| After removing emoji | 695 | 11 | 503 | 4 |

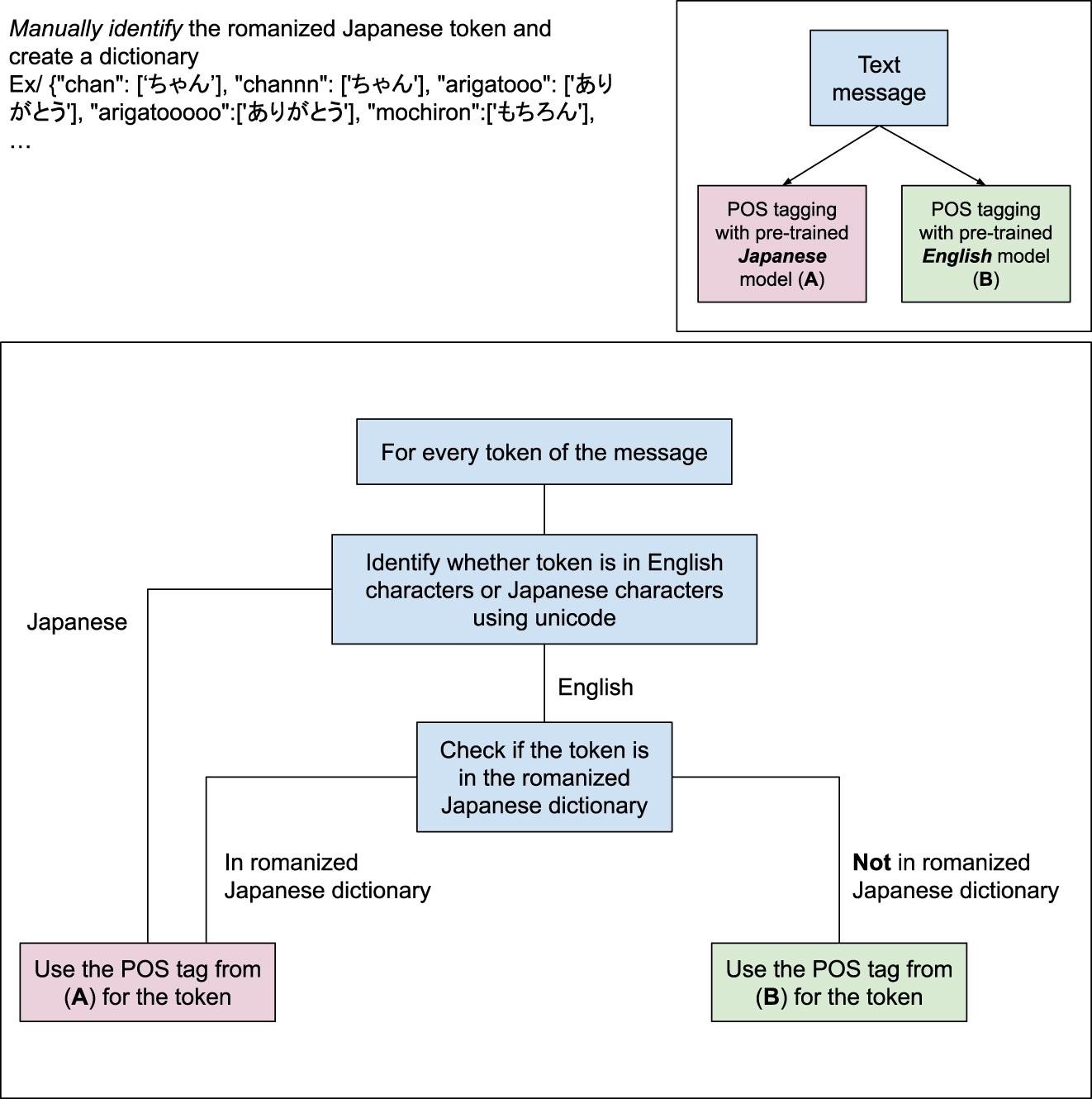

To observe the code-switching patterns in the data, we first analyzed the part of speech (POS) of each token using spaCy (Honnibal et al. 2020), a Python natural language processing library that performs tokenization and POS tagging. SpaCy has support for multiple languages and is an open-source tool, making it suitable for our Japanese-English bilingual data. We initially tried spaCy’s pre-trained pipelines for multilingual data but found the POS tagging accuracy lacking upon manual inspection. Instead, we conducted POS tagging on each message using both the English and the Japanese pre-trained models. Each token was identified as either English or Japanese first, and then the POS tag from the appropriate language was used as the POS tag for that token. The romanized Japanese tokens were manually identified from the data and were mapped to their equivalent in Japanese characters with a dictionary we created, then subsequently passed through the Japanese POS tagger. An overview of this process, including an example of the dictionary to map romanized Japanese words to Japanese characters, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Part of speech tagging process of the Japanese-English code-switching dataset.

Tokenization was performed by spaCy to segment the sentence into words. An example of the result returned by spaCy’s token segmentation and POS tagging for one of the messages in our data is: [[‘最近’, ‘ADV’], [‘好き’, ‘ADJ’], [‘な’, ‘AUX’], [‘動画’, ‘NOUN’]]. Therefore, through the process outlined in Figure 1, we can count the number of English, Japanese, and romanized Japanese words and identify the POS of each word. The number of words of each language in the data can be seen in Table 3.

Number of words of each language.

| Chat type | English | Japanese | Romanized Japanese | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct messages (speakers A, C) | 2,213 | 1,887 | 25 | 4,125 |

| Group chat (speakers A, B, C) | 4,741 | 2,045 | 42 | 6,828 |

| Total | 6,954 | 3,932 | 67 | 10,953 |

We further annotated the data by identifying whether the code-switched messages were intra-sentential or inter-sentential. This was done by manually going through the messages. Messages were marked as intra-sentential if two or more languages were used within the same sentence, as in (1a). Messages were marked as inter-sentential if two or more languages were used between sentences either in the same message, as in (1b), or in consecutive messages, as in (1c), where the symbol “//” indicates two separate messages. In the examples provided throughout this article, English translations of Japanese words, phrases, or sentences are included in parentheses.

| めっちゃ (‘big’) fan なんだね (‘seems like’) |

| No rush! ゆっくり来てねー (‘Take your time’) |

| no worries!! // プレゼンがんばれっ‼ (‘Good luck on your presentation!!’) |

For messages that were marked as inter-sentential code-switching, we further annotated the data by identifying the flow of languages used. For instance, example (1c) was labeled as “Eng to Jpn”, signifying that the speaker switched from using English to Japanese.

3 Descriptive results

In the dataset, including the direct message (DM) and group chat (GC) data, about 63.5 % of the data was in English, 35.9 % was in Japanese, and 0.612 % was in romanized Japanese, suggesting that the host language is English while the embedded language is Japanese. Since all three of these Gen Z bilinguals were born and raised in the US, it is expected that the primary language used would be English, but it is noticeable that there is a surprisingly high proportion of Japanese. Comparing the DM data and the GC data, the ratio of Japanese used in DMs (45.7 %) was much higher than the ratio of Japanese used in the GC (30 %). The difference in the ratio of Japanese messages across the DMs and GC could reflect the language backgrounds of the speakers and their language preferences at home in the respective chats: the messages in the DMs exchanged between speakers A and C have a much higher ratio of Japanese, which may come from speaker C primarily speaking Japanese at home and preferring to use Japanese when texting with friends from the same Japanese American community.

We also looked at the distribution of the parts of speech used within each language. Here, we looked at Japanese (written in the traditional Japanese writing systems) and romanized Japanese as two different categories. Table 4 presents the top 10 parts of speech for each language within each chat type, DMs and GC.

Distribution of parts of speech (POSs) in direct messages (DMs) and group chat (GC). The codes for the parts of speech are: ADJ adjective; ADP adposition; ADV adverb; AUX auxiliary; CCONJ coordinating conjunction; DET determiner; INTJ interjection; NOUN noun; NUM numeral; PART particle; PRON pronoun; PROPN proper noun; PUNCT punctuation; SCONJ subordinating conjunction; VERB verb.

| DM English | DM Japanese | DM Romanized | GC English | GC Japanese | GC Romanized | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POS | % | POS | % | POS | % | POS | % | POS | % | POS | % |

| PRON | 14.69 % | NOUN | 17.54 % | ADJ | 40.0 % | VERB | 14.36 % | NOUN | 20.88 % | AUX | 23.81 % |

| PUNCT | 14.46 % | AUX | 14.26 % | NOUN | 24.0 % | PRON | 13.65 % | ADP | 14.08 % | NOUN | 19.05 % |

| VERB | 13.65 % | VERB | 14.10 % | ADV | 12.0 % | NOUN | 13.18 % | AUX | 13.74 % | ADJ | 19.05 % |

| NOUN | 10.94 % | ADP | 13.88 % | ADP | 12.0 % | PUNCT | 9.70 % | VERB | 12.62 % | VERB | 11.90 % |

| AUX | 7.18 % | PUNCT | 12.35 % | PART | 8.0 % | ADV | 7.78 % | PUNCT | 10.02 % | ADV | 9.52 % |

| ADP | 6.51 % | ADV | 6.47 % | PRON | 4.0 % | PROPN | 6.96 % | ADV | 5.92 % | PRON | 4.76 % |

| ADV | 5.56 % | SCONJ | 5.56 % | PROPN | 0.0 % | AUX | 6.52 % | SCONJ | 5.67 % | ADP | 4.76 % |

| PROPN | 5.51 % | ADJ | 4.88 % | PUNCT | 0.0 % | ADP | 5.70 % | ADJ | 5.43 % | PROPN | 4.76 % |

| NUM | 5.29 % | PART | 4.45 % | INTJ | 0.0 % | ADJ | 5.34 % | PART | 4.06 % | CCONJ | 2.38 % |

| ADJ | 4.20 % | PROPN | 2.60 % | AUX | 0.0 % | DET | 3.84 % | PROPN | 3.72 % | NUM | 0.00 % |

Table 4 indicates that nouns are consistently in the top five parts of speech, regardless of the language or chat type, echoing previous studies on Japanese-English code-switching (Azuma 1997). Verbs also tend to be in the top five parts of speech except in the romanized DM data. A notable difference between English and Japanese is that in both the DMs and the GC, the percentage of auxiliary verbs in Japanese (14.26 % in DMs and 13.74 % in GC) is about twice that of auxiliary verbs in English (7.18 % in DMs and 6.52 % in GC). Furthermore, pronoun is a commonly seen part of speech in English for both the DM and GC data; however, it does not appear in the top 10 parts of speech for Japanese, which may result from the fact that pronouns, in general, are much rarer in Japanese than in English.

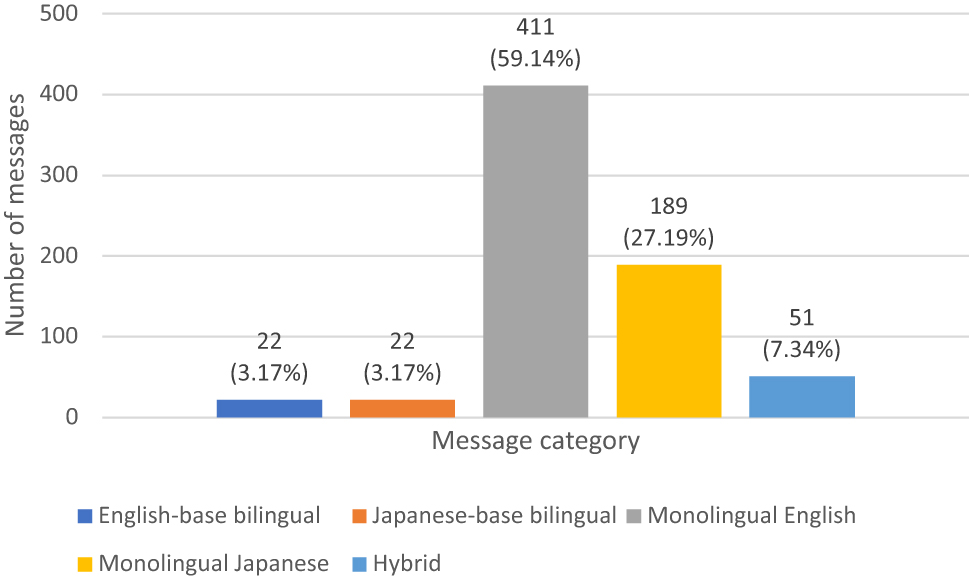

We also conducted an analysis following Derrick’s (2015) sentence-by-sentence analysis to study the linguistic nature of the messages. We manually categorized the 1,198 messages into five categories: monolingual English messages, English-base bilingual messages, monolingual Japanese sentences, Japanese-base bilingual messages, and hybrid messages. Examples of each type of message are presented in (2). The frequency of each type of message in both the DM and the GC data is shown in Figures 2 and 3, with approximately 13 % of the messages being bilingual or hybrid messages. This result suggests a very common use of code-switching in CMC texting among these Gen Z Japanese Americans, since the percentage of bilingual or hybrid messages is much higher than reported in literature (Derrick 2015; Montes-Alcalá 2024; Shepherd 2021).

Analysis of the linguistic nature of the direct messages.

Analysis of the linguistic nature of the group chat.

| Monolingual English messages: | i wish they would put lyrics on the big screen |

| English-base bilingual messages: | Guyssss I just saw 工藤くん (‘Kudo kun’) |

| Monolingual Japanese sentences: | でも全然覚えられてない (‘But I can’t remember it at all’) |

| Japanese-base bilingual messages: | Soo 渋滞によって 6:30 とか? (‘Depending on traffic around 6:30?’) |

| Hybrid message: | 今日はちょっと忙しいけど (‘(I) am a bit busy today, but’) any other day this week should work for me! |

Interestingly, the hybrid sentences have a much higher distribution in the GC than in the DMs. In contrast, the DMs have a much higher proportion of monolingual Japanese sentences and Japanese-base bilingual sentences. We conjecture that the more frequently a speaker orally code-switches at home, the more they will code-switch over text messaging with friends. Likewise, the more frequently a speaker uses an embedded language at home, the more likely they will use that embedded language over text messaging with friends who are in the same bilingual community. To further testify to these hypotheses, we further analyzed the linguistic nature of the messages by speaker.

Figures 4 and 5 show how many messages of each category (Monolingual English messages, English-base bilingual messages, Monolingual Japanese sentences, Japanese-base bilingual messages, and hybrid messages) each of the speakers sent.[1] Figure 4 shows that speaker B (who frequently code-switches with a sibling at home) has more bilingual and hybrid messages, and speaker C (whose whole family speaks Japanese at home) sends the most monolingual Japanese messages to friends. In Figure 5, we observe a similar pattern: speaker C sends more monolingual Japanese sentences and tends to code-switch less than speaker A (who speaks both English and Japanese at home). Both Figures 4 and 5 confirm the conjectures: a high frequency of oral code-switching at home or a high frequency of using both languages at home is reflected in a high frequency of code-switching in text messages with friends, while a high frequency of speaking the embedded language (i.e., Japanese in this case) at home is reflected in a high frequency of texting in that embedded language with bilingual friends.

Analysis of the linguistic nature of the group chat by speaker.

Analysis of the linguistic nature of the direct messages by speaker.

4 Discussion

Our dataset shows that Japanese usage accounts for as much as 45.7 % of the messages in one of the text chats and 35.9 % of the overall dataset. The high proportion of Japanese usage in our bilingual text dataset is contrary to Shepherd’s (2021) observation that postwar second-generation Japanese Americans primarily use English with occasional Japanese. Our dataset thus suggests that Japanese-English bilinguals (in particular, those in Generation Z) switch between Japanese and English frequently in their text messages with their fellow Japanese-English bilinguals, despite English being the dominant language in their daily life.

4.1 “We know these two languages so well that we easily and comfortably switch between them”

The motivations or reasons for code-switching have been often argued to include low language proficiency or lack of proficiency in one of the languages, lack of linguistic knowledge about specific vocabulary, addressing a specific audience, and ease of communicating information in the same language it was learned in (Zhang 2019; among others). The speakers represented in our dataset are Japanese-English simultaneous bilinguals who have maintained native-level proficiency in both languages as they grew up. Therefore, their even code-switching between two languages when texting each other is not explained by a lack of proficiency or linguistic knowledge of one language nor by the ease of communicating or addressing a specific audience. Instead, the frequent code-switching observed in the Japanese-English simultaneous bilinguals is more likely attributable to their comprehensive mastery of both languages, including reading and writing, and their familiarity with navigating environments where both languages are used. Their active code-switching between both languages showcases their strong confidence in their linguistic proficiency. More importantly, such high engagement in switching between Japanese and English suggests that these Gen Z Japanese Americans actively use both languages to construct their bilingual and bicultural identity, echoing the argument that code-switching in CMC is an identity marker among young bilinguals (Gonzales and Tsang 2023; Lienard and Penloup 2011; Magaña 2013; Montes-Alcalá 2007, 2024).

Regarding the distribution of parts of speech in the dataset, we confirmed some findings in Japanese-English code-switching literature that nouns, verbal nouns, and adjectivals (words with the [+N] feature) are the most frequently code-switched parts because they can meaningfully stand alone. Moreover, we found a new pattern that was not reported in the literature: auxiliary verbs are high on the list of most frequently code-switched parts. We also observed a much higher percentage of auxiliary verbs in the Japanese data than in the English data – see (3) for examples[2] – and in most instances that we observed, auxiliary verbs in Japanese are used to signify politeness and respect.

| ごめん | 今 | 向かい | ます |

| Sorry | now | heading | polite.auxiliary.marker |

| ‘Sorry, I’m on my way now’ | |||

| 123 | address | st | でーす |

| 123 | Address | St | polite.auxiliary.marker |

| ‘It’s 123 Address St’ | |||

These auxiliary verbs in Japanese are often associated with certain cultural and pragmatic meanings that are missing in English. The equivalent English phrase would lose the nuance that differentiates phrases with and without politeness markers in Japanese. However, this observed pattern of frequent use of Japanese auxiliary verbs for politeness is surprising since Japanese speakers typically switch to a much more casual form of speech when speaking with friends who are similar aged in a casual online texting setting. We argue that this pattern comes from two sources: one is that Gen Z bilinguals are closely attuned to the cultural and pragmatic nuance differences between Japanese and English, and another is that CMC texting messages, though a casual type of computer-mediated communication, are still in written format, which may prompt higher politeness in speech.

These bilinguals’ full mastery of these two languages is also apparent in the pronoun pattern observed in the data: pronouns were used regularly in the English data but were observed much less frequently in the Japanese data (Table 4). This pattern is expected for fluent bilinguals as it shows that they have the knowledge that Japanese allows pronoun drop – that is, that subjects and objects are often omitted and implicitly understood through context – while English does not. Research has shown that English speakers, when learning Japanese as a second language, interpret pronouns and the pronoun drop linguistic feature in Japanese differently from Japanese native speakers, and Japanese speakers, when learning English as a second language, use English pronouns differently from English native speakers (Hirakawa 1990; Nagano and Martohardjono 2023). If the participants did not have full mastery of Japanese, we would expect a different pronoun pattern in the dataset. Examples (4a) and (4b) exemplify how bilingual speakers are fully aware of the grammatical differences between English and Japanese and omit pronouns when messaging in Japanese but include pronouns when messaging in English. Example (4a) is an exchange between speakers A and C in Japanese and all of the pronouns that would typically be included when speaking in English were dropped. Example (4b) consists of consecutive messages sent by speaker A where they used the pronouns we and you to explicitly state the subject and direct object of the English message, but the ‘we’ is implied when they switched to Japanese. Therefore, the observed pronoun pattern in the data also suggests that these Gen Z bilinguals are closely attuned to the linguistic and pragmatic nuance differences between Japanese and English, which argues against an “incompetence” account for code-switching.

| Speaker C: | ごめん今向かいます!!! (‘Sorry (I) am headed over (there) now!!!’) |

| Speaker A: | もう昼食べた? (‘Have (you) eaten already?’) |

| Speaker C: | うん軽く食べてる! (‘Yup (I) am eating lightly’) |

| Speaker A: | we can go get you when you get here! |

| Speaker A: | 入り口のとこで待ってるよー (‘(We) are waiting at the entrance’) |

4.2 “Texting with bilingual friends reflects our uses of two languages at home”

A closer look into the speakers’ language background and their code-switching frequency (Figures 2–5) reveals an interesting but barely reported code-switching pattern in the literature: a higher frequency of oral code-switching or using both languages at home is reflected in a higher frequency of code-switching in text messages with friends, while a higher frequency of speaking the embedded language at home is reflected in a higher frequency of texting in that embedded language with bilingual friends. Example (5) presents a message bubble among the three speakers and shows their preferences for bilingual messages or monolingual text.

| Speaker A: | i think im going home tuesday and 火曜日までプロジェクトで忙しいかも (‘I’m busy with a project until Tuesday’) |

| Speaker B: | Sad. perhaps do something more up north towards end of the week? Only if you can tho!! 無理なしに (‘No pressure’) |

| Speaker A: | im not sure i’ll be able to gomennn (‘sorryyy’) |

| Speaker C: | 日本帰ってきたら学校始まる前に会おうよ!はるかちゃんも一緒に! (‘Let’s hang out when we’re back from Japan before school starts! With Haruka too!’) |

When zooming in on the non-monolingual messages, like that in (5), we observed slightly higher but very similar occurrences of inter-sentential code-switching (120 messages) than intra-sentential code-switching (103 messages). This is different from the pattern reported in Poplack (1980) and Koban (2013), which were based on oral speech data: there, intra-sentential code-switching was more common than inter-sentential code-switching among proficient Spanish-English bilingual speakers and among proficient Turkish-English bilingual speakers in New York. However, we do not have enough evidence to attribute the differences in inter-sentential and intra-sentential code-switching patterns to our dataset being CMC texting data and the data of Poplack (1980) and Koban (2013) being oral. A recent study by Gonzales and Tsang (2023), based on CMC text data, also found that the vast majority of code-switched utterances (99.5 %) in their Cantonese-English WhatsApp dataset were intra-sentential, similar to Poplack’s and Koban’s observations. Previous studies proposed that the distribution of different types of code-switching is related to language fluency or the medium of communication. Poplack (1980) and Lipski (1985) argue that more fluent bilinguals do more intra-sentential code-switching while less fluent bilinguals do more inter-sentential code-switching. Gonzales and Tsang (2023) argue that CMC texting makes bilinguals tend to text short messages or one-word messages, which consequently makes it very difficult to find inter-sentential code-switching, that is, two distinct sentences of different languages in one speech bubble. However, our data does not support either an “incompetence” account nor a “CMC constraint” account.

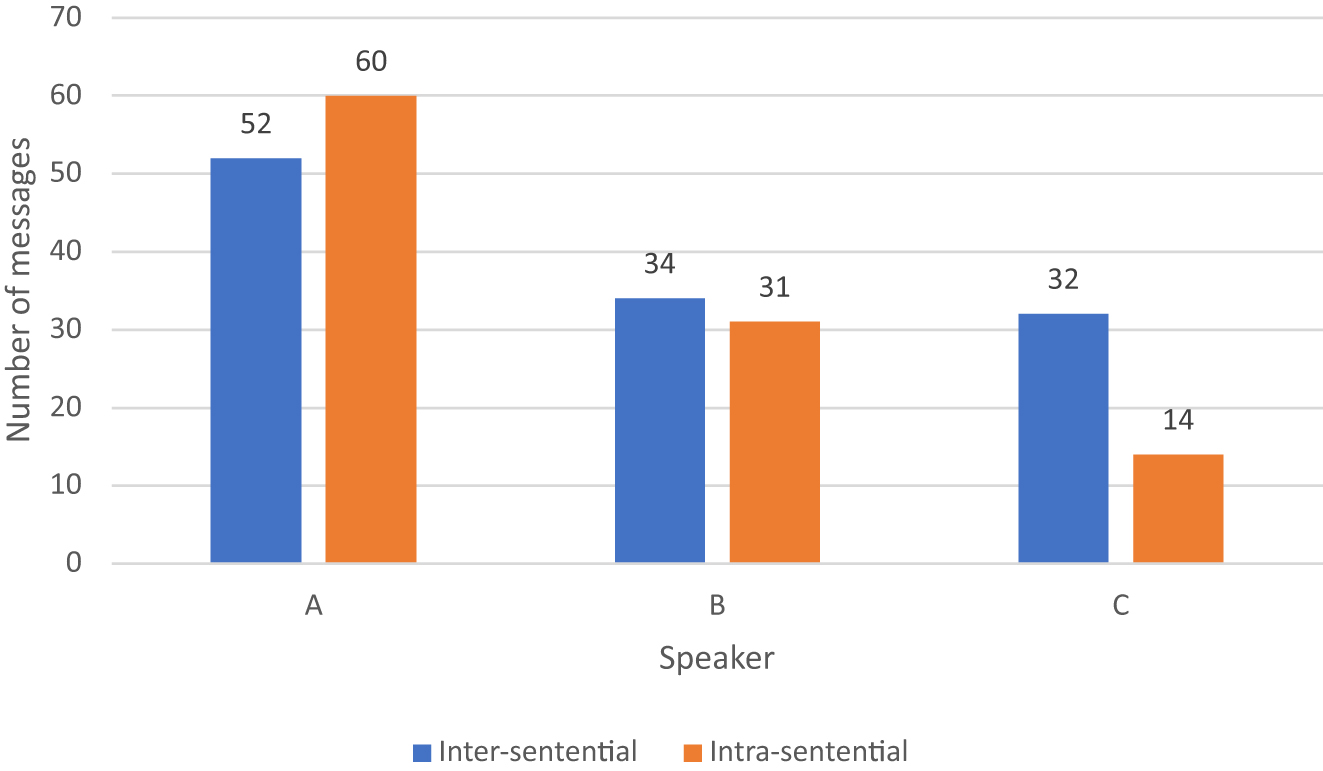

Our data suggests a slightly higher occurrence of inter-sentential code-switching in a CMC dataset for proficient bilinguals, and moreover, considering the data by speaker, speakers A and B have no strong preference between inter-sentential code-switching and intra-sentential code-switching, while speaker C strongly prefers inter-sentential code-switching (Figure 6). Speaker C’s proficiency in either language is no lower than that of the other two speakers, as all three speakers are simultaneous bilinguals and have all reported full command of both languages. The only difference among speakers is that speaker C is the only one who primarily uses Japanese at home with both parents and siblings. Therefore, higher occurrences of a certain type of code-switching may not come from language competency or the constraints of CMC as a medium, but rather the language preference among family members extends to CMC texting among bilingual friends.

Type of code-switching by speaker.

The proposed explanation is also supported by the analysis of language flow. For messages that were marked as inter-sentential code-switching, we further annotated the data by identifying the flow of languages used (Tables 5 and 6). Speaker C, who primarily uses Japanese at home, uses both Japanese and English in daily life, and produces the most monolingual Japanese messages, no doubt has full command of Japanese. If speaker C preferred inter-sentential code-switching because of a lack of proficiency in English, then we would expect a much higher English-to-Japanese-switch in speaker C’s data. If speaker C was influenced by the CMC medium constraint, we would expect speaker C to have very few English to Japanese and Japanese to English inter-sentential code-switched sentences, since switching keyboards to type two sentences of different languages in one speech bubble is not very convenient when texting. However, neither the “incompetence” account nor the “CMC constraint” can explain the higher occurrence of inter-sentential code-switching for speaker C.

Inter-sentential language switch frequency in direct messages.

| Direct messages | Speaker A | Speaker C | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eng to Jpn | 14 | 10 | 24 |

| Jpn to Eng | 15 | 13 | 28 |

| Eng to Rom | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Jpn to Eng to Jpn | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Rom to Eng | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Eng to Jpn to Eng | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Rom to Jpn | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Jpn to Eng to Jpn to Eng | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 36 | 26 | 62 |

Inter-sentential language switch frequency in group chat.

| Group chat | Speaker A | Speaker B | Speaker C | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eng to Jpn | 6 | 18 | 3 | 27 |

| Eng to Jpn to Eng | 2 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Eng to Rom | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Eng to Rom to Eng | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Jpn to Eng | 3 | 11 | 2 | 16 |

| Jpn to Eng to Jpn | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Rom to Eng | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 16 | 32 | 8 | 56 |

4.3 “We code-switch with our innovative style when texting friends”

Our dataset reveals unique code-switching patterns related to the switches between writing systems, including the presence of romanized Japanese words, as in (6); the elongation of a syllable-final segment, as in (7); mixing of writing scripts, as in (8); and English words written in traditional Japanese writing systems, as in (9); all are rarely reported in the literature on code-switching.

| EEEEEEE. | IMA | SUGOKU. | NOMITAI |

| Wow | right.now | very | want.to.drink |

| ‘Wow, I really want to try that now’ | |||

| arigatooo |

| thanks |

| ‘Thank youuu’ |

| そういえば (‘By the way’) if youre taking your clothes to kendeda chotto mendokusai kamo (‘it might be a little bothersome’) i think you might have to hang them up on the racks by yourself..? |

| みなさんファイナル頑張ってね (‘Good luck on your finals everyone’) |

| 私: 30ごろに一誠ピックしに行かなきゃいけないみたいで (‘(It) seems like I have to go pick up Issei around 1:30’) |

Mixing different scripts in a way that makes sense to a particular community but not the general population is not a recent development. In the 1990s and into the 2000s, young Japanese girls developed a writing practice called gyaru-moji (literally ‘girl-graph’), where Japanese characters, math symbols, and non-Japanese characters were combined and read as Japanese syllables. According to Miller (2011), the main motivations behind the development of gyaru-moji were to resist the conformity and conventions of male-dominated print media, for privacy, and as a “form of group identity marking”. However, there is no notion of resistance or making a statement through script-mixing observed in our dataset. Instead, the bilinguals surveyed in this study mix scripts naturally and comfortably when sending text messages to other Japanese-English bilingual speakers.

We argue that the innovative script-mixing observed in this CMC code-switching dataset is a linguistic stylistic practice developed by these Gen Z bilinguals. Eckert (2003) defines linguistic stylistic practice as “adapting linguistic variables available out in the larger world to the construction of social meaning on a local level”. This is exactly what the bilinguals in our study have done, as they not only code-switch core language components but switch writing scripts as well. The way they code-switch in the CMC medium may not be intuitive to everyone, including monolingual speakers of these languages, but the style of their messages comes naturally to them and others in their local Japanese American community. To a certain extent, their linguistic style is forming a CMC style of Japanese-English code-switching.

There are a couple of reasons why the speakers may have chosen to write out Japanese words in romanized alphabet instead of Japanese characters. First is a pragmatic reason. Romanized Japanese can be used to duplicate the syllable-final segment or write the words in all capital letters for emphasis, as in (6) and (7). Another reason could be for convenience when using CMC to send messages. When typing using the QWERTY keyboard (English), it is more convenient to type out a Japanese word using the same keyboard instead of switching to the Japanese keyboard, and this would produce examples such as (8). In example (9), the fact that Japanese katakana ファイナル and ピック were used to refer to the pronunciation of the English words final and pick, respectively, could also be for convenience. When typing using a Japanese keyboard, it is more convenient to type out English words using the same Japanese keyboard. But, compared to the popularity of romanized Japanese writing systems among Japanese monolingual speakers, using traditional Japanese writing systems to write English words is more of an innovation by the Japanese-English bilingual speakers.

These code-switching patterns associated with writing systems offer a fresh angle for examining code-switching in CMC. Additionally, our thoroughly annotated dataset serves as an excellent resource for training and testing language technologies tailored to Japanese-English code-switching in CMC.

5 Summary and future work

The dataset created and analyzed in this study is one of the first of its kind on Japanese-English code-switching in CMC, to the best of our knowledge. The findings from this dataset challenge commonly cited motivations and reasons for code-switching. We found that code-switching among the Japanese-English bilinguals is a result of their full mastery of both Japanese and English, not due to a lack of language proficiency. This study also highlighted rarely discussed patterns and features of written code-switching: the frequency at which the speakers orally code-switch and speak the embedded language (Japanese) at home is reflected in their code-switching patterns over text messages. Additionally, this study highlighted the development of an unique CMC style of Japanese-English code-switching, characterized by the use of romanized Japanese words, elongation of Japanese words using romanization, mixing writing scripts, and English words written in Japanese characters.

The present study has certain limitations that we aim to address in future research. In the present study, we removed emojis from the data analysis, as the processing tool we used could not handle emojis properly. However, emojis are widespread in CMC and have been argued to represent the morphosyntax of a lexically typed stem and to undergo linguistic changes (Storment 2024). In a future study, we would like to incorporate recent work on annotating emojis (Shoeb and de Melo 2021) to broaden our investigations into understanding the role of emojis in code-switching in CMC texting and the factors influencing speakers’ choice between English, Japanese, romanized Japanese, or English words in Japanese script, along with emojis. Another limitation of the present study is that the dataset is unbalanced. In the present study, the dataset was collected from female Gen Z bilinguals only and there is no data from male bilinguals nor from older bilinguals. However, studies have shown that female bilinguals have different code-switching patterns from male bilinguals (Gonzales and Tsang 2023). In future studies, we hope to expand the dataset to create a balanced and large-scale corpus of bilingual code-switching texting data so that we can analyze the sociopragmatic and communicative patterns of these data, and thoroughly investigate the potential factors that could influence the code-switching patterns in CMC texting. We also hope to expand the corpus by including both oral and text bilingual data from the same speakers, allowing us to observe differences in code-switching patterns in writing versus oral production.

Funding source: Georgia Institute of Technology

Acknowledgments

Many thanks go to the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback. We are grateful to the speakers who participated in this study and to Priya Rajeev for the helpful discussions on the implementation of spaCy in data annotation. An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the 2024 Annual Meeting of the Linguistics Society of America, and we also want to thank the audience at that conference for their feedback. For academic purposes, the authors’ contributions are as follows: Ema Goh: data collection, processing, annotation and analysis, drafting and revising the manuscript. Hongchen Wu: conception and design of the study, project administration, data analysis, and interpretation, checking and revising the manuscript.

-

Research funding: This work is supported by the Professional Development Fund from the School of Modern Languages, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts, awarded to Hongchen Wu at Georgia Institute of Technology.

References

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2007. Language choice and code switching in German-based diasporic web forums. In Brenda Danet & Susan C. Herring (eds.), The multilingual internet: Language, culture, and communication online, 340–361. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195304794.003.0015Search in Google Scholar

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. 2013. Code-switching in computer-mediated communication. In Susan C. Herring, Dieter Stein & Tuija Virtanen (eds.), Pragmatics of computer-mediated communication, 659–686. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110214468.667Search in Google Scholar

Appel, René & Pieter Muysken. 2005. Language contact and bilingualism. Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press.10.5117/9789053568576Search in Google Scholar

Azuma, Shoji. 1997. Lexical categories and code-switching: A study of Japanese/English code-switching in Japan. Journal of the Association of Teachers of Japanese 31(2). 1–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/489656.Search in Google Scholar

Barasa, Sandra Nekesa. 2016. Spoken code-switching in written form? Manifestation of code-switching in computer mediated communication. Journal of Language Contact 9. 49–70. https://doi.org/10.1163/19552629-00901003.Search in Google Scholar

Callahan, Laura. 2004. Spanish/English codeswitching in a written corpus (Studies in Bilingualism 27). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/sibil.27Search in Google Scholar

Derrick, Roshawnda A. 2015. Code-switching, code-mixing and radical bilingualism in US Latino texts. Detroit: Wayne State University PhD dissertation. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations/1309 (accessed 21 November 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Eckert, Penelope. 2003. The meaning of style. Texas Linguistic Forum 47. 41–53.Search in Google Scholar

Estigarribia, Bruno & Zachary Wilkins. 2018. Analyzing the structure of code-switched written texts: The case of Guarani-Spanish Jopara in the novel Ramona Quebranto. Linguistic Variation 18. 120–143. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.00007.est.Search in Google Scholar

Gonzales, Wilkinson Daniel Wong & Yuen Man Tsang. 2023. The sociolinguistics of code-switching in Hong Kong’s digital landscape: A mixed-methods exploration of Cantonese-English alternation patterns on WhatsApp. Journal of English and Applied Linguistics 2(1). 1–21. https://doi.org/10.59588/2961-3094.1041.Search in Google Scholar

Halim, Nur Syazwani & Marlyna Maros. 2014. The functions of code-switching in Facebook interactions. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 118. 126–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.02.017.Search in Google Scholar

Hirakawa, Makiko. 1990. A study of the L2 acquisition of English reflexives. Interlanguage Studies Bulletin (Utrecht) 6(1). 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/026765839000600103.Search in Google Scholar

Honnibal, Matthew, Ines Montani, Sofie Van Landeghem & Adriane Boyd. 2020. spaCy: Industrial-strength natural language processing in Python. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1212303.Search in Google Scholar

Koban Koç, Didem. 2013. Intra-sentential and inter-sentential code-switching in Turkish-English bilinguals in New York City. U. S. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 70. 1174–1179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.173.Search in Google Scholar

Leppänen, Sirpa. 2012. Linguistic and generic hybridity in web writing: The case of fan fiction. In Mark Sebba, Shahrzad Mahootian & Carla Jonsson (eds.), Language mixing and code-switching in writing: Approaches to mixed-language written discourse, 233–254. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Lienard, Fabian & Marie-Claude Penloup. 2011. Language contacts and code-switching in electronic writing: The case of the blog. In Foued Laroussi (ed.), Code-switching, languages in contact and electronic writing, 73–86. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Lin, Angel. 2005. Gendered, bilingual communication practices: Mobile text messaging among Hong Kong college students. Fibreculture Journal 6. http://six.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-031-genderedbilingual-communication-practices-mobile-text-messaging-among-hong-kong-college-students/ (Accessed 19 December 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Lipski, John M. 1985. Linguistic aspects of Spanish-English language switching. Tempe: Center for Latin American Studies, Arizona State University.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, Huayu. 2023. Translanguaging or code-switching? A case study of multilingual activities in college-level Mandarin and Japanese classrooms. Swarthmore, PA: Swarthmore College BA thesis. https://works.swarthmore.edu/theses/312 (accessed 21 November 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Mabule, Dorah Riah. 2015. What is this? Is it code switching, code mixing or language alternating? Journal of Educational and Social Research 5. 339–350. https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2015.v5n1p339.Search in Google Scholar

Magaña, Dalia. 2013. Code-switching in social-network messages: A case-study of a bilingual Chicana. International Journal of the Linguistic Association of the Southwest 32. 43–65.Search in Google Scholar

Matsuda, Yuki. 2017. Expressing ambivalent identities through popular music: Socio-cultural analysis of Japanese writing systems. Southeast Review of Asian Studies 39. 133–142.Search in Google Scholar

Miller, Laura. 2011. Subversive script and novel graphs in Japanese girls’ culture. Language & Communication 31. 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2010.11.003.Search in Google Scholar

Milroy, Lesley & Pieter Muysken (eds.). 1995. One speaker, two languages: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on code-switching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511620867Search in Google Scholar

Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. 2005. Mándame un e-mail: Cambio de códigos español-inglés online. In Luis Ortiz López & Manel Lacorte (eds.), Contactos y contextos lingüísticos: El español en los Estados Unidos y en contacto con otras lenguas, 173–185. Madrid: Iberoamericana.10.31819/9783865278586-011Search in Google Scholar

Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. 2007. Blogging in two languages: Code-switching in bilingual blogs. In Jonathan Holmquist, Augusto Lorenzino & Lotfi Sayahi (eds.), Selected proceedings of the Third Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics, 162–170. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.Search in Google Scholar

Montes-Alcalá, Cecilia. 2024. Bilingual texting in the age of emoji: Spanish–English code-switching in SMS. Languages 9(4). Article no. 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9040144.Search in Google Scholar

Myers-Scotton, Carol. 2017. Code-switching. In Florian Coulmas (ed.), The handbook of sociolinguistics, 217–237. Oxford: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405166256.ch13.Search in Google Scholar

Nagano, Marisa & Gita Martohardjono. 2023. Language-specific properties and overt pronoun interpretation: The case of L2 Japanese. Second Language Research 40. 959–987. https://doi.org/10.1177/02676583231195306.Search in Google Scholar

Nakayama, Sahoko, Takatomo Kano, Quoc Truong Do, Satoshi Sakti & Satosh Nakamura. 2018. Japanese-English code-switching speech data construction. 2018 Oriental COCOSDA – International Conference on Speech Database and Assessments, Miyazaki, Japan, May 7–8, 2018, 67–71. Miyazaki: IEEE.10.1109/ICSDA.2018.8693044Search in Google Scholar

Nishimura, Miwa. 1995. A functional analysis of Japanese/English code-switching. Journal of Pragmatics 23(2). 157–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(93)E0103-7.Search in Google Scholar

Otheguy, Ricardo, Ofelia García & Wallis Reid. 2019. A translanguaging view of the linguistic system of bilinguals. Applied Linguistics Review 10(4). 625–651. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2018-0020.Search in Google Scholar

Poplack, Shana. 1980. Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish Y TERMINO EN ESPAÑOL: Toward a typology of code-switching. Linguistics 18(7–8). 581–618. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1980.18.7–8.581.10.1515/ling.1980.18.7-8.581Search in Google Scholar

Shepherd, Andre John. 2021. Japanese-English code-switching by postwar speakers in contemporary America. Portland: Portland State University master’s thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Shoeb, Abu Awal Md & Gerard de Melo. 2021. Assessing emoji use in modern text processing tools. In Chengqing Zong, Fei Xia, Wenjie Li & Roberto Navigli (eds.), Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 1379–1388. Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/2021.acl-long (accessed 21 November 2024).10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.110Search in Google Scholar

Storment, John David. 2024. Going ✈ lexicon? The linguistic status of pro-text emojis. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 9(1). 1–43. https://doi.org/10.16995/glossa.10449.Search in Google Scholar

Ting, Su-Hie & Kai-Liang Yeo. 2019. Code-switching functions in Facebook wallposts. Human Behavior, Development and Society 20. 7–18.Search in Google Scholar

Tsiplakou, Stavroula. 2009. Doing (bi)lingualism: Language alternation as performative construction of online identities. Pragmatics 19. 361–391. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.19.3.04tsi.Search in Google Scholar

US Census Bureau. 2021. Language spoken at home. American Community Survey, ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables, Table S1601. https://data.census.gov/table?q=Language%20Spoken%20at%20Home&y=2021 (accessed 21 November 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Xitong. 2019. Code-switching in English-Chinese ordinary conversations. TESOL Working Paper Series 17. 38–45.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Editorial 2024

- Phonetics & Phonology

- The role of recoverability in the implementation of non-phonemic glottalization in Hawaiian

- Epenthetic vowel quality crosslinguistically, with focus on Modern Hebrew

- Japanese speakers can infer specific sub-lexicons using phonotactic cues

- Articulatory phonetics in the market: combining public engagement with ultrasound data collection

- Investigating the acoustic fidelity of vowels across remote recording methods

- The role of coarticulatory tonal information in Cantonese spoken word recognition: an eye-tracking study

- Tracking phonological regularities: exploring the influence of learning mode and regularity locus in adult phonological learning

- Morphology & Syntax

- #AreHashtagsWords? Structure, position, and syntactic integration of hashtags in (English) tweets

- The meaning of morphomes: distributional semantics of Spanish stem alternations

- A refinement of the analysis of the resultative V-de construction in Mandarin Chinese

- L2 cognitive construal and morphosyntactic acquisition of pseudo-passive constructions

- Semantics & Pragmatics

- “All women are like that”: an overview of linguistic deindividualization and dehumanization of women in the incelosphere

- Counterfactual language, emotion, and perspective: a sentence completion study during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Constructing elderly patients’ agency through conversational storytelling

- Language Documentation & Typology

- Conative animal calls in Macha Oromo: function and form

- The syntax of African American English borrowings in the Louisiana Creole tense-mood-aspect system

- Syntactic pausing? Re-examining the associations

- Bibliographic bias and information-density sampling

- Historical & Comparative Linguistics

- Revisiting the hypothesis of ideophones as windows to language evolution

- Verifying the morpho-semantics of aspect via typological homogeneity

- Psycholinguistics & Neurolinguistics

- Sign recognition: the effect of parameters and features in sign mispronunciations

- Influence of translation on perceived metaphor features: quality, aptness, metaphoricity, and familiarity

- Effects of grammatical gender on gender inferences: Evidence from French hybrid nouns

- Processing reflexives in adjunct control: an exploration of attraction effects

- Language Acquisition & Language Learning

- How do L1 glosses affect EFL learners’ reading comprehension performance? An eye-tracking study

- Modeling L2 motivation change and its predictive effects on learning behaviors in the extramural digital context: a quantitative investigation in China

- Ongoing exposure to an ambient language continues to build implicit knowledge across the lifespan

- On the relationship between complexity of primary occupation and L2 varietal behavior in adult migrants in Austria

- The acquisition of speaking fundamental frequency (F0) features in Cantonese and English by simultaneous bilingual children

- Sociolinguistics & Anthropological Linguistics

- A computational approach to detecting the envelope of variation

- Attitudes toward code-switching among bilingual Jordanians: a comparative study

- “Let’s ride this out together”: unpacking multilingual top-down and bottom-up pandemic communication evidenced in Singapore’s coronavirus-related linguistic and semiotic landscape

- Across time, space, and genres: measuring probabilistic grammar distances between varieties of Mandarin

- Navigating linguistic ideologies and market dynamics within China’s English language teaching landscape

- Streetscapes and memories of real socialist anti-fascism in south-eastern Europe: between dystopianism and utopianism

- What can NLP do for linguistics? Towards using grammatical error analysis to document non-standard English features

- From sociolinguistic perception to strategic action in the study of social meaning

- Minority genders in quantitative survey research: a data-driven approach to clear, inclusive, and accurate gender questions

- Variation is the way to perfection: imperfect rhyming in Chinese hip hop

- Shifts in digital media usage before and after the pandemic by Rusyns in Ukraine

- Computational & Corpus Linguistics

- Revisiting the automatic prediction of lexical errors in Mandarin

- Finding continuers in Swedish Sign Language

- Conversational priming in repetitional responses as a mechanism in language change: evidence from agent-based modelling

- Construction grammar and procedural semantics for human-interpretable grounded language processing

- Through the compression glass: language complexity and the linguistic structure of compressed strings

- Could this be next for corpus linguistics? Methods of semi-automatic data annotation with contextualized word embeddings

- The Red Hen Audio Tagger

- Code-switching in computer-mediated communication by Gen Z Japanese Americans

- Supervised prediction of production patterns using machine learning algorithms

- Introducing Bed Word: a new automated speech recognition tool for sociolinguistic interview transcription

- Decoding French equivalents of the English present perfect: evidence from parallel corpora of parliamentary documents

- Enhancing automated essay scoring with GCNs and multi-level features for robust multidimensional assessments

- Sociolinguistic auto-coding has fairness problems too: measuring and mitigating bias

- The role of syntax in hashtag popularity

- Language practices of Chinese doctoral students studying abroad on social media: a translanguaging perspective

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Metaphor and gender: are words associated with source domains perceived in a gendered way?

- Crossmodal correspondence between lexical tones and visual motions: a forced-choice mapping task on Mandarin Chinese