Abstract

Background

Limited research is available concerning the relationship between oxidative stress and inflammation parameters, and simultaneously the effects of rosuvastatin on these markers in patients with hypercholesterolemia. We aimed to investigate the connection between cytokines and oxidative stress markers in patients with hypercholesterolemia before and after rosuvastatin treatment.

Methods

The study consisted of 30 hypercholesterolemic patients diagnosed with routine laboratory tests and 30 healthy participants. The lipid parameters, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), paraoxonase-1 (PON1) and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in controls and patients with hypercholesterolemia before and after 12-week treatment with rosuvastatin (10 mg/kg/day), were analyzed by means of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

It was found that a 12-week cure with rosuvastatin resulted in substantial reductions in IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α and MDA levels as in rising activities of PON1 in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Before treatment, the PON1 levels were significantly negatively correlated with TNF-α and IL-6 in control group, while it was positively correlated with TNF-α in patients.

Conclusion

Our outcomes provide evidence of protected effect of rosuvastatin for inflammation and oxidative damage. It will be of great interest to determine whether the correlation between PON1 and cytokines has any phenotypic effect on PON1.

Öz

Amaç

Hiperkolesterolemili hastalarda oksidatif stres ile inflamasyon parametreleri arasındaki ilişkiye ve rosuvastatinin bu belirteçler üzerindeki eş zamanlı etkilerine ilişkin sınırlı sayıda araştırma mevcuttur. Rosuvastatin tedavisi öncesi ve sonrasında hiperkolesterolemili hastalarda sitokin ve oksidatif stres belirteçleri arasındaki ilişkiyi araştırmayı amaçladık.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Çalışma, rutin laboratuvar testleri ile tanı konulan otuz hiperkolesterolemik hastayı ve 30 sağlıklı katılımcıyı kapsamaktadır. Kontroller ve 12 haftalık rosuvastatin (10 mg/kg/gün) tedavisi öncesi ve sonrası hiperkolesterolemi hastalarda lipid parametreleri, interlökin-1 beta (IL-1β), interlökin-6 (IL-6), tümör nekrozis faktör-alfa (TNF-α), paraoksonaz-1 (PON1) ve malondialdehid (MDA) seviyeleri enzim bağlı immünosorbent ile analiz edildi.

Bulgular

Rosuvastatin ile yapılan 12 haftalık tedavinin, hiperkolesterolemisi olan hastalarda PON1 aktivitesini yükseltirken; IL-1β, IL-6 ve TNF-α ve MDA düzeylerinde önemli azalmalar sağladığı bulunmuştur. Tedavi öncesi hastalarda PON1 düzeyleri TNF-α ile pozitif ilişkiliyken kontrol grubunda PON1 düzeyleri TNF-α ve IL-6 ile anlamlı derecede negatif ilişkiliydi.

Sonuç

Sonuçlarımız rosuvastatinin inflamasyon ve oksidatif hasar için koruyucu etkisinin kanıtını sunmaktadır. PON1 ve sitokinler arasındaki korelasyonun PON1 üzerinde herhangi bir fenotipik etkiye sahip olup olmadığını belirlemek büyük ilgi çekecektir.

Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia, which means elevation in plasma cholesterol levels, increases the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [1]. Peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease and stroke associated with hypercholesterolemia take the first place among the causes of morbidity and mortality. Previous studies found that decreased hypercholesterolemia severely reduces the number of foam cells [2]. Imaging techniques approved that reduction in cholesterol levels might upgrade regression of atherosclerosis in humans [3].

Clinical studies have shown a correlation between lipid metabolism and inflammation. The patients with hypercholesterolemia have been reported to experience significant changes in serum cytokine levels. Moreover, it has been displayed that atherosclerosis can be considered as ongoing immune reaction and inflammatory response of increased inflammatory disease [4]. This inflammation is associated with interleukin-6 (IL-6), the main stimulator of the formation of acute phase proteins. On the other hand, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) have profound effects on formation and development of atherosclerosis and impact subgroups of acute phase proteins [5].

Inflammation may start due to increased oxidative damage to macromolecules. Previous studies found that oxidative stress is an underlying pathomechanism of atherosclerosis [6]. Recently, new evidences have established that oxidative stress has significant impact on starting and progression of atherosclerosis [7], [8]. Also, the decreased antioxidant capacity and increased oxidative stress are likely to promote the elevated risk of a cardiovascular disease [9]. Lipid peroxidation is well established as oxidative stress index in tissues and cells. Elevated lipid peroxidation levels have been connected with many diseases [10]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is extensively used as an index of lipid peroxidation [11]. Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) is an element of this oxidative mechanism, and has drawn attention as a protein responsible for one of the components of antioxidant features of High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) [12]. It is proposed that oxidative stress related with decreased activities of PON1 has been found in patients with hypercholesterolemia [13].

Previous studies showed that statins have been favorite therapy means as lipid lowering drugs and are extensively used for the medication of hypercholesterolemia [14]. Statins are implemented in wide range of immuno-modulating and anti-inflammatory activities [15]. One of the members of statin family is rosuvastatin. Compared to other statins, chemical and pharmacokinetic properties of rosuvastatin submit a very restricted penetration to extra hepatic tissues with a lower risk of toxicity [16]. Rosuvastatin might at the same time apply an inhibiting impact on inflammation parameters [17].

As mentioned above, inflammation may start due to increased oxidative damage [6] and incessant persistent inflammation could culminate in the inception and progression of atherosclerosis. The patients with hypercholesterolemia have been reported to experience significant changes in serum cytokines levels [2], [3], [4]. Moreover, clinical experiments propose that statins possess direct anti-inflammatory effects and antioxidative stress independent of their influences on plasma cholesterol levels [7], [14], [18], [19]. Rosuvastatin is a novel statin with a long half-life, more potency in lipid lowering and humble liver metabolism than other statins [20]. We know little about the mechanism(s) underlying the antiinflammatory and antioxidative impacts of rosuvastatin. Considering these aspects, we hypothesized that the inflammatory and oxidative stress markers may be altered by hypercholesterolemia; and hypercholesterolemia treatment with rosuvastatin may restore this condition. On the other hand, the relationship between inflammatory and oxidative stress markers may be differentiated by treatment in patients with hypercholesterolemia. However, there is restricted number of studies related to the influences of rosuvastatin simultaneously on inflammation and oxidative stress markers in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to measure IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MDA, PON1 levels in patients with hypercholesterolemia before and after treatment with rosuvastatin.

Methods

Study population and design

The study group included 30 patients aged 18–65 diagnosed with hypercholesterolemia and 30 healthy subjects who were examined and treated at the clinic of Medicine Faculty of Erciyes University in Kayseri, Turkey. Erciyes University Ethics Committee affirmed the study protocol by (15-03-2013/96681246-103). Low density lipoprotein (LDL) limit was determined in compliance with the European Society of Cardiology [21].

Patients, who applied to the cardiology outpatient clinic and received an indication for statin therapy by cardiologists according to current guidelines, were included in study. According to current guidelines, it is recommended that calculation of the patient’s 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASHV) and life-long risk of ASHV be carried out by using a special scoring method. For patients with age≥21 and LDL≥190 (without ASKV risk estimation), high-intensity statin therapy is recommended for primary prevention [22]. Patients were given information about the research and they, by signing, certified the informed consent form according to Helsinki Declaration. The subjects with renal failures, coronary artery diseases, liver diseases, immune system diseases, diabetes, systemic diseases hypertension; and for any reason, the ones receiving treatment with medications such as lipid-lowering drugs, using alcohol and cigarettes were excluded from the study. Patients with similar age and gender distribution and 30 healthy volunteers, who had no systemic diseases and were nonsmokers and did not use any drugs and whose body mass index was in the range 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, were included in study.

Rosuvastatin (10 mg/kg/day) was applied to all ill participants for 12-weeks. Before and after treatment with rosuvastatin, concentrations of serum lipids, serum IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MDA and PON1 levels were quantified. Dietary and exercise treatments were carried out; in addition, the patients were suggested not to change their lifestyle.

Determination of lipid profiles

After being fast for an overnight (≥12 h), control and patient groups were asked to give blood samples which were collected in vacutainer BD serum separation tubes comprise a thrombin-based clot activator and polymer gel for serum separation (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Being let to clot for 30 min., samples were centrifuged at 2000 ×g for 10 min as always. Not only lipemic but hemolyzed samples as well were taken out. The aliquots of samples were stored at −70°C until measurements.

Serum total cholesterol (TC), trigliserid (TG), LDL (using direct LDL kit) and HDL were analyzed by means of Advia 1800 chemistry system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

Determination of cytokines and oxidative stress markers

The serum IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and PON1 levels were detected by making use of a commercial enzyme-linked immunoassay kit: For IL-1β (KHC0011, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), for IL-6 (KHC0061, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), for TNF-α (EK0525, Boster, Valley Ave Pleasanton, CA, USA) and for PON1 (SK00141-01, AVISCERA BIOSCIENCE, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Micro-plates were washed with micro ELISA washer (BioTek ELx800, Highland Park, Vermont, USA) and optical density was determined with ELISA reader (BioTek ELx800).

Antibodies specific to IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and PON1 were pre-coated on the microplates. Briefly, we pipetted standards and samples into the wells; and added biotin-conjugated specific antibodies over them. Then, we added avidin conjugated horseradish peroxidase to the wells after removing any unbound substances. Chromogen reagent was added to the wells and later the plate was let to be incubated. The color development was stopped by using stop solution and the optical density of wells was measured under 450 nm. Coefficient of variation (CV) of intra-assay for IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and PON1 were found to be <3%, <3%, <3% and <6%, respectively. Inter-Assay CV for IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α and PON1 were found to be <9.3%, <7.3%, <7.5% and <12%, respectively.

Determination of malondialdehyde

The serum MDA levels were detected with a mercantile Assay Kit, [Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances] (10009055, Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The TBARS Assay was carried out in line with the manufacture’s instruction, and, concisely, the MDA-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) adduct formed by the reaction of TBA and MDA under acidic conditions and 90–100°C was gauged colorimetrically at 532 nm. Intra-Assay CV for MDA was established to be <7.6%, while inter-Assay CV for MDA was found to be <5.9%.

Statistic analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing statistics programs with IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The usual distribution of the data was determined by the Shapiro-Wilktest. The statistics of the variables with normal distribution were given as the mean±standard deviation (SD) and variables with no normal distribution were verbalized as median (25th–75th percentile) categorical variables were given in numbers. Independent samples of t-test were utilized for normal distributions in the intergroup comparisons. Before treatment-After treatment differences were compared with paired samples t. Variables with no normal distribution were evaluated by using Wilcoxon test and Mann-Whitney U-test. Pearson and Spearman analysis was benefited to examine the relationship between variables. When the p-value was less than 5%, it was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Anthropometric parameters of the patients and control group are presented in Table 1. No significant differences were noticed between patients and control group in terms of age, gender, weight, height and BMI values (Table 1). In this table, the mean ages of patients were 46.94±9.11 and the controls were 46.26±8.11. Nineteen patients and controls were women and 11 patients and controls were men (Table 1).

Basic characteristics of the patients and controls.

| Patient (n=30) | Controls (n=30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.9±9.2 | 46.2±8.11 | 0.469 |

| Gender (F/M) | 19/11 | 19/11 | 0.999 |

| Height (m) | 1.62±0.1 | 1.64±0.1 | 0.497 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.2±9.9 | 63.9±8.8 | 0.785 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7±0.95 | 23.4±1.1 | 0.406 |

Data are expressed as numbers for categorical variables and mean±SD for continuous variables. F, Female; M, male.

It is available to see the study populations clinical and laboratory parameters in Table 2. Before treatment, the mean values of TC, TG and directly measured LDL (D-LDL) levels were significantly lower in control group than in patients (p<0.001). There were no significant differences between control and patients before treatment in terms of serum HDL (p=0.058). The mean values of TC, TG and D-LDL levels were lower (p<0.001) while mean values of HDL were significantly lower in patients before treatment than patients after treatment (p=0.002). The mean values of D-LDL, TC and TG were higher in patients after treatment than control group (p=0.007, p<0.001 and p<0.001; respectively). There were no significant differences between patients and control after treatment in terms of serum HDL (p=0.560; Table 2).

Biochemical measurement results of the patients and the controls.

| Parameters | Patients | Controls (n=30) | Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment (n=30) | After treatment (n=30) | Before treatment-control | After treatment-control | Before treatment-After treatment | ||

| TC (mg/dL) | 269.4±22.1 | 182.0±25.1 | 158.9±16.0 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 43.4±7.21 | 46.1±7.1 | 47.3±8.24 | p=0.058 | p=0.560 | p=0.002 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 164.2±45.0 | 140.0±35.4 | 103.8±40.7 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| D-LDL (mg/dL) | 188.9±23.5 | 104.3±26.1 | 87.7±12.7 | p<0.001 | p=0.007 | p<0.001 |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 40.2 (37.9–44.3) | 38.5 (34.6–42.5) | 30.7 (27.6–35.1) | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 47.2±11.6 | 37.2±9.10 | 37.1±6.71 | p<0.001 | p=0.848 | p<0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 29 (24.9–32.6) | 21.7 (19.3–23.4) | 18.8 (15.4–23.1) | p<0.001 | p=0.114 | p<0.001 |

| MDA (μM) | 6.4±1.57 | 4.32±1.12 | 2.11±0.96 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| PON-1 (ng/mL) | 9.87±2.88 | 17.5±4.67 | 17.8±6.0 | p<0.001 | p=0.815 | p<0.001 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD or median (25th–75th percentile) for continuous variables. The significance of differences in variables between before-treatment and control or after-treatment and control was tested using independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test. The significance of differences of variables between before treatment and after treatment were tested using paired samples t-test or Wilcoxon test.

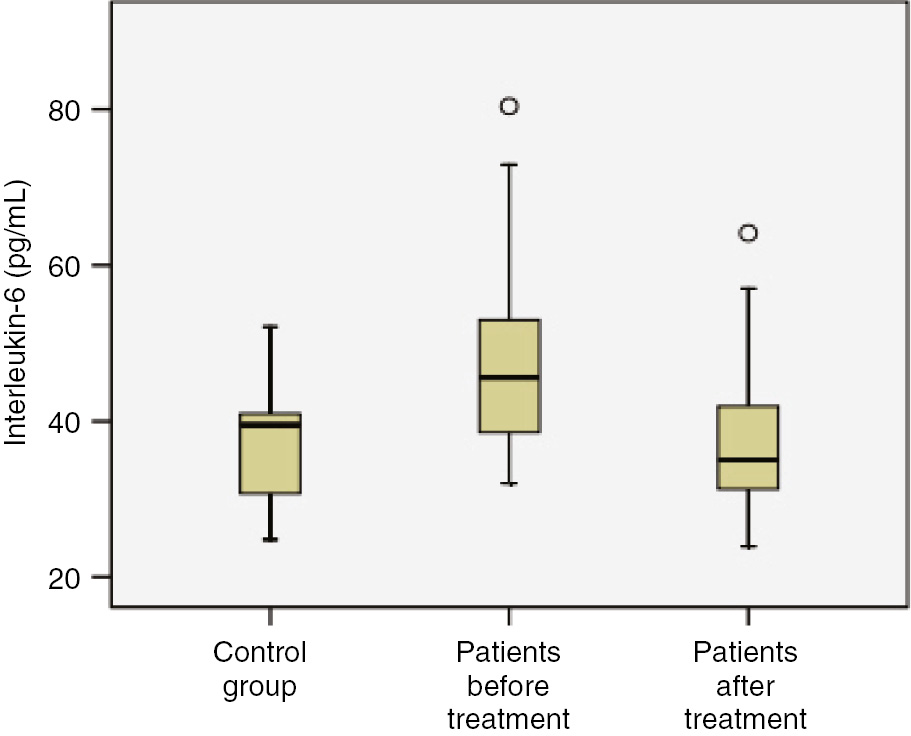

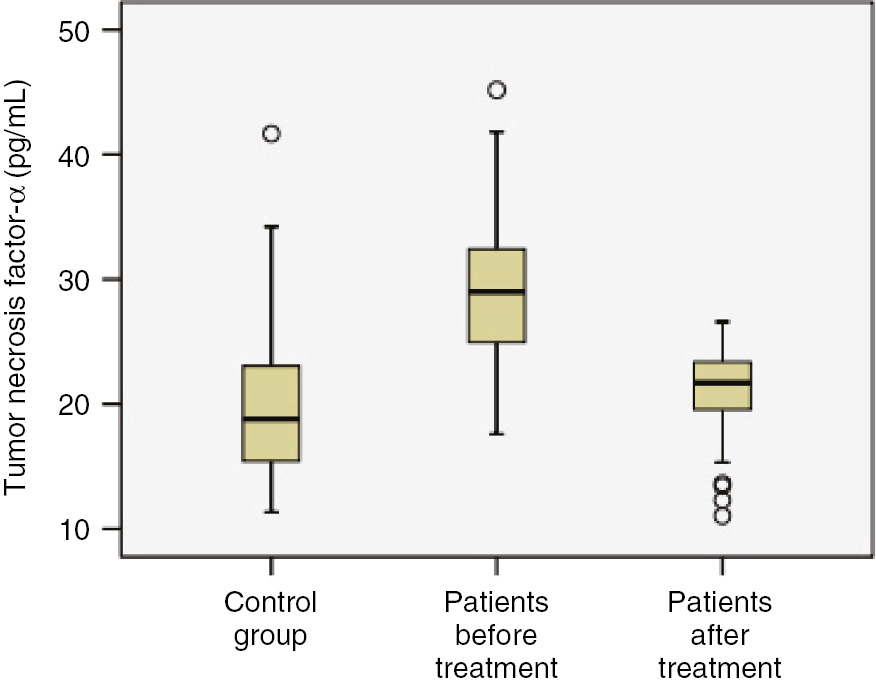

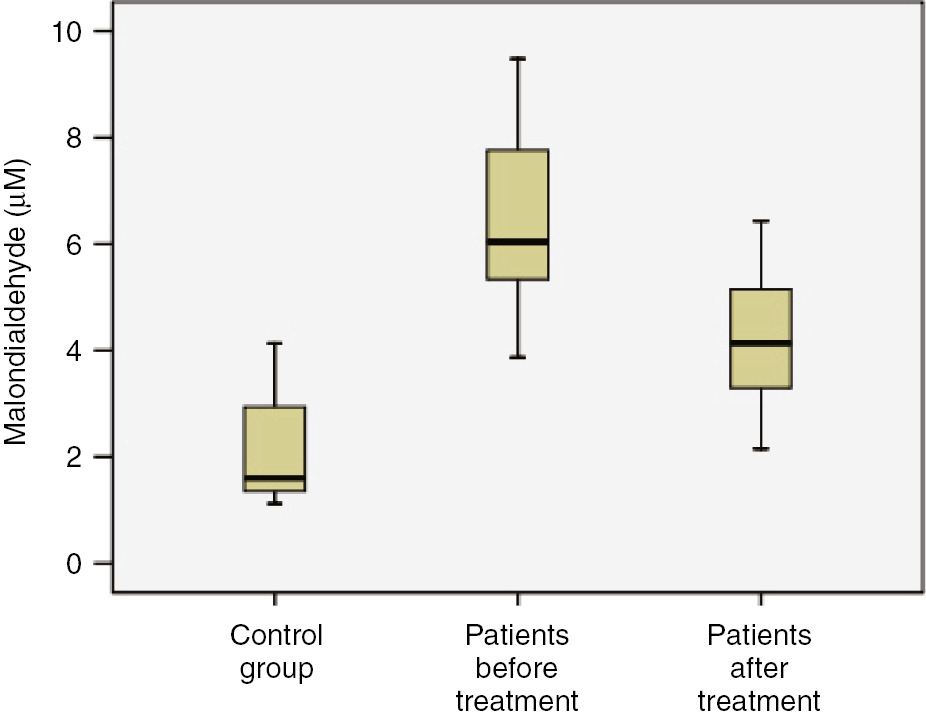

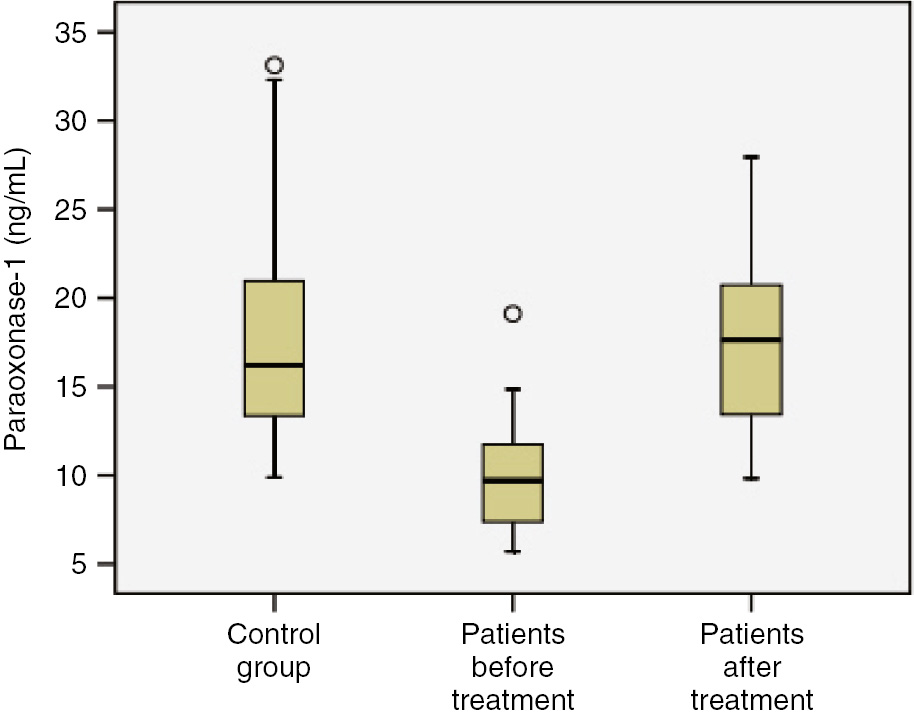

Before treatment, the mean levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in patients were found to be higher than those of control group (Figures 1 and 2, p<0.001). The mean levels of MDA were higher, while the mean values of PON1 were lower in patients before treatment than control group (Table 2, Figure 3; p<0.001). The mean levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were lower in patients after treatment than patients before treatment (p<0.001). The mean levels of MDA were lower, while the mean values of PON1 were higher in patients after treatment than patients before treatment (Table 2; Figure 4, p<0.001). The mean values of IL-1β were significantly higher in patients after treatment than control group (p<0.001). No significant differences were established between control group and patients after treatment with regard to serum IL-6 and TNF-α. The mean values of MDA were considerably higher in patients after treatment than control group (p<0.001). The mean values of PON1 were significantly lower in patients after treatment than control group (p<0.001).

Comparison of study groups in terms of Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) concentration.

Comparison of study groups in terms of tumor necrosis factor-α (pg/mL) concentration.

Comparison of study groups in terms of malondialdehyde (μM) concentration.

Comparison of study groups in terms of paraoxonase-1 (ng/mL) concentration.

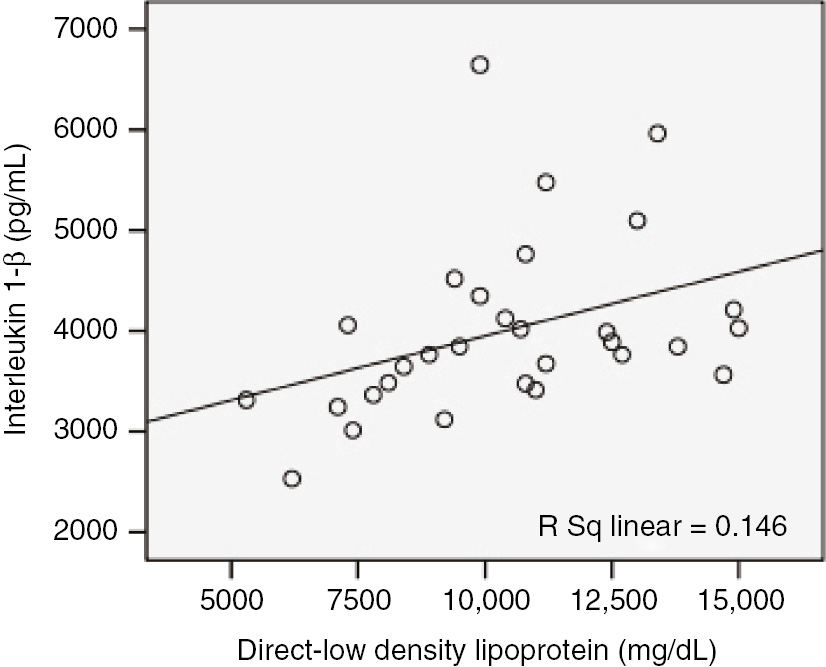

The correlation analyses revealed that HDL levels had significantly negative medium level correlation with TNF-α in control group (r=−0.518; p<0.003). The PON1 levels had significantly negative medium level correlation with IL-6 and TNF-α in control group (r=−0.432, p=0.032; r=−0.472, p=0.008, respectively). The PON1 levels had significantly positive medium level correlation with TNF-α in patients before treatment (r=0.532, p=0.002). The D-LDL levels had significantly positive weak level correlation with IL-1β in patients after treatment (r=0.383, p=0.037; Figure 5). Other values of correlation coefficient between inflammatory and oxidative markers are shown in Table 3.

Correlation of direct low density lipoprotein (mg/dL) with interleukin 1-β (pg/mL) in patients after treatment (r=0.383, p=0.037).

The correlation values between oxidative stress and inflammation parameters in study groups.

| TC | HDL | LDL | IL-6 | TNF-α | PON | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | ||||||

| HDL | 0.542b | 1 | 0.186 | 0.138 | −0.518b | |

| LDL | 0.757b | 0.186 | 1 | −0.058 | 0.060 | −0.124 |

| PON | 0.040 | 0.183 | −0.124 | −0.432a | −0.472b | 1 |

| Patients before treatment | ||||||

| TC | 1 | 0.389a | 0.895b | −0.170 | −0.004 | −0.180 |

| LDL | 0.895b | 0.174 | 1 | −0.137 | −0.006 | −0.205 |

| PON | −0.180 | 0.244 | −0.205 | 0.097 | 0.532b | 1 |

| Patients after treatment | ||||||

| TC | 1 | −0.255 | 0.918b | 0.305 | 0.123 | −0.072 |

| LDL | 0.918b | −0.340 | 1 | 0.383a | 0.059 | −0.182 |

| IL-1β | 0.305 | −0.308 | 0.383a | 1 | −0.301 | 0.103 |

Pearson and Spearman analyses were used to examine the relationship between parameters ap<0.05, bp<0.01. Significant values are given in bold.

Discussion

In the present study, we tried to display that a 12-week treatment with rosuvastatin 10 mg daily improved lipid profile levels and was associated with significant reductions in IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and MDA levels, yet significant increase in serum levels of PON1.

Rupture of coronary plaques and formation of thrombus, the basic mechanism causing acute coronary syndromes, are described in detail by a great lipid core, elevated number of macrophages and T lymphocytes, reduced number of smooth muscle cells [23]. Statins could function through multiple receptors and pathways in their target cells. Besides its consequent suppression of cholesterol biosynthesis, several studies have proved that rosuvastatin may exert more protective influences, requiring the enhancement of endothelial function and stabilization of atherosclerotic plaque [20].

In our study, although we found that there were no significant differences between controls and patients after treatment in respect to D-LDL and HDL levels, it was shown that D-LDL levels decreased by 40–60%, while HDL levels increased by 6.3% in patients with hypercholesterolemia after treatment. The reduction in D-LDL levels is also consistent with European Society of Cardiology 2016 hyperlipidemia guide and previously conducted clinical trials; and there is also a quite great deal of interindividual variation in LDL decrease with the same dose of drug [24]. Poor reaction to statin treatment in clinical studies is, to a certain extent, led by poor concordance, yet it could as well be described by a genetic background necessitating variations in genes because of both statin uptake and cholesterol metabolism in the liver [25], [26]. Moreover, status leading to high cholesterol (e.g. hypothyroidism) ought to be contemplated. To tell the truth, interindividual diversities in statin response permit observing the individual response at the start of therapy.

In this study, we tried to exhibit that a 12-week treatment with rosuvastatin had a close connection with significant decrease in IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α levels.

Studies, conducted before, displayed that rosuvastatin exert multiple purpose variations in inflammatory cells; for instance decrease in cytokines on isolated cells, animal models, and patients [18]. TNF-α and IL-6 can initiate a number of intracellular signaling events, and have an important role in the inflammatory cascade and promote vascular inflammation [27]. McGuire et al. suggested that decreases in TNF-α level might be a potential mechanism for anti-inflammatory activity of rosuvastatin [28]. However, how rosuvastatin regulates cytokines expression in patients with hypercholesterolemia is not clear enough. Nevertheless, some scholars proposed that statins could change expression of cellular inflammatory factors via mediating calcium modulating proteins [29]. It was also demonstrated that miR-155 is upregulated in activated immune cells and it attenuates immune responses by regulating cell differentiation (as in Th1 and Tregs) and cytokine secretion (as in TNF-a and IL-6) [18]. On the other hand, some proofs point to the reduced production of mevalonate and isoprenoids, the first yield produced by HMG-CoA reductase [30]. It was also found that the statin-induced downregulation of cytokine production in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are regressed by coincubation with mevalonate. This monitoring shows a specific statin influence and a role of the mevalonate-isoprenoid pathway in cytokine production [31]. Experimental studies also suggest that pretreatment with statin significantly reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines by inhibiting NF-03CFB expression in myocardial tissue [32]. Therefore, it may be suggested that rosuvastatin reduces the IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α levels by using above-mentioned pathways. However, the molecular mechanism is not sufficiently clear; and further cellular, experimental and controlled clinical studies on the role of rosuvastatin in prevention of the formation of inflammation in terms of cytokine are required.

The present research demonstrated the correlation between inflammation and oxidative stress parameters in study groups. It was determined that 12-week treatment with rosuvastatin significantly lowered the MDA levels, while it significantly increased levels of PON1 after treatment. We also established that PON1 levels were significantly negatively correlated with IL-6 and TNF-α in control group, while PON1 levels were significantly positively correlated with TNF-α in the patients before treatment.

People with obvious rise in MDA-modified LDL were demonstrated to be more predisposed to advanced arterosclerosis statin medication having a positive effect on reducing serum MDA levels in human. It was found that rosuvastatin inhibited the elevations of MDA in rats and humans [33]. Bergheanu et al. showed that during 18 weeks of treatment, only PON-1 activity was rose substantially from baseline in the rosuvastatin group. Nevertheless, the difference could not reach to be even significance compared directly with atorvastatin [19]. Oxidative stress plays a fundamental role in atherosclerosis basically by inciting endothelial dysfunction and improving proinflammatory processes causing formation of atherosclerotic plaque [34]. Kumon et al. stated that IL-1 and TNF-α downregulated serum PON1 activity [35]. It was also observed that increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α caused reduction in serum PON1 activity [36]. In addition, hepatic PON1 mRNA synthesis was downregulated by treatment of IL-1, IL-1β and TNF-α [35], [36].

Consistent with the previous studies, we determined that PON1 levels were significantly positively correlated with TNF-α in the patients before treatment, while PON1 levels were significantly negatively correlated with IL-6 and TNF-α in the control group. Although PON1 is a HDL related with enzyme taking part in the protective mechanisms of HDL [19], it was found that HDL levels increased by 6.3%, while PON1 levels increased by 77.3% in patients with hypercholesterolemia after treatment. Moreover, we did not establish any significant relationships between HDL and PON1 levels after treatment.

In individuals, serum PON-1 activity rather than genetic variation in the PON-1 gene foresees vascular disease and a study carried out lately exhibits a sound relation of coronary artery disease and angiographic severity with PON-1 activity, regardless of age, abnormal glucose regulation, hypertension, HDL-cholesterol and smoking [19]. As a result, reduction in PON1 in serum of patients with hypercholesterolemia could be associated with the rise of these cytokines [19], [34], [35], [36]. We suggest that PON1 levels might be changed as part of the inflammatory response as well, and thus seems that this balance is disrupted in patients with hypercholesterolemia. It may be also suggested that serum levels of PON1 is directly capable of suppressing serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β. It may also be said that PON1 levels, which vary with treatment, are associated with cytokines instead of HDL levels in patients. Therefore, we propose that this condition may be an important mechanism for the action of rosuvastatin.

Nevertheless, the present research has some restrictions such as the insufficient number of participants and our inability to detect the circadian variation of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. Another limitation is the lack of the patients with hypercholesterolemia who are not separated by phenotypes according to PON1 and arylesterase activity since PON1 activity includes arylesterase activity. Therefore, further research is required to certify and enhance these studies since it is not absolutely clear how treatment with rosuvastatin affects the correlations between PON1 and cytokines in patients with hypercholesterolemia.

Conclusions

Our results provide evidence for the protective effect of rosuvastatin against inflammation and oxidative damage by lowered serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and MDA, and ascending activities of PON1 in patients with hypercholesterolemia after treatment. On the other hand, correlation between PON1 levels and cytokines may be suggested that lowered serum PON1 levels may be one of the mechanisms underlying the augmented threat of not only oxidative stress but also inflammation process. It will be of great interest to determine other potential causes of correlation between PON1 and cytokines, and to learn whether this has any phenotypic effect on PON1.

Acknowledgement

The expenditure of above study was met by Erciyes University Scientific Research Project Coordination Center (TSA-2013-4542).

Conflict of interest statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

1. Viola J, Soehnlein O. Atherosclerosis – a matter of unresolved inflammation. Semin Immunol 2015;27:184–93.10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.013Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Kapourchali FR, Surendiran G, Chen L, Uitz E, Bahadori B, Moghadasian MH. Animal models of atherosclerosis. World J Clin Cases 2014;2:126–32.10.12998/wjcc.v2.i5.126Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Bruckert E. Recommendations for the management of patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: overview of a new European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Atheroscler Suppl 2014;15:26–32.10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2014.07.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002;420: 868–74.10.1038/nature01323Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Kushner I. Regulation of the acute phase response by cytokines. Perspect Biol Med 1993;36:611–22.10.1353/pbm.1993.0004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Stadtman ER, Berlett BS. Reactive oxygen-mediated protein-oxidation in ageing and disease. Drug Metab Rev 1998;30:225–43.10.3109/03602539808996310Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Förstermann U. Oxidative stress in vascular disease: causes, defense mechanisms and potential therapies. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:338–49.10.1038/ncpcardio1211Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Wang Y, Wang GZ, Rabinovitch PS, Tabas I. Macrophage mitochondrial oxidative stress promotes atherosclerosis and nuclear factor-Bmediated inflammation in macrophages. Circ Res 2014;114:421–33.10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302153Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Herbet M, Gawrońska-Grzywacz M, Jagiełło-Wójtowicz E. Evaluation of selected biochemical parameters of oxidative stress in rats pretreated with rosuvastatin and fluoxetine. Acta Pol Pharm 2015;72:261–5.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Nayak DU, Karmen C, Frishman WH, Vakili BA. Antioxidant vitamins and enzymatic and synthetic oxygen-derived free radical scavengers in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Heart Dis 2001;3:28–45.10.1097/00132580-200101000-00006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Ayala A, Muñoz MF, Argüelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014;2014:360438.10.1155/2014/360438Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Mackness MI, Arrol S, Durrington PN. Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein. FEBS Lett 1991;286:152–4.10.1016/0014-5793(91)80962-3Suche in Google Scholar

13. Rozenberg O, Shih DM, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) attenuates macrophage oxidative status: studies in PON1 transfected cells and in PON1 transgenic mice. Atherosclerosis 2005;181 9–18.10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.030Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Heeba GH, Hamza AA. Rosuvastatin ameliorates diabetes-induced reproductive damage via suppression of oxidative stress, inflammatory and apoptotic pathways in male rats. Life Sci 2015;141:13–9.10.1016/j.lfs.2015.09.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Quist-Paulsen P. Statins and inflammation: an update. Curr Opin Cardiol 2010;25:399–405.10.1097/HCO.0b013e3283398e53Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Toth PP, Dayspring TD. Drug safety evaluation of rosuvastatin. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2011;10:969–86.10.1517/14740338.2012.626764Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Awad AS, El Sharif A. Immunomodulatory effects of rosuvastatin on hepatic ischemia/reperfusion induced injury. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2010;32:555–61.10.3109/08923970903575716Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Xie W, Li P, Wang Z, Chen J, Lin Z, Liang X, et al. Rosuvastatin may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes receiving percutaneous coronary intervention by suppressing miR-155/SHIP-1 signaling pathway. Cardiovasc Ther 2014;32:276–82.10.1111/1755-5922.12098Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Bergheanu SC, Van Tol A, Dallinga-Thie GM, Liem A, Dunselman PH, Van der Bom JG, et al. Effect of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin treatment on paraoxonase-1 activity in men with established cardiovascular disease and a low HDL-cholesterol. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:2235–40.10.1185/030079907X226104Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Liang D, Zhang Q, Yang H, Zhang R, Yan W, Gao H, et al. Anti-oxidative stress effect of loading-dose rosuvastatin prior to percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin Drug Investig 2014;34:773–81.10.1007/s40261-014-0231-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Papadakis MA, McPhee SJ, Rabow MW. Current medical diagnosis & treatment, 50rd ed. New York, USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies Lange, 2013:1246–55.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129 (25 Suppl 2):1–45.10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7aSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Nilsson L, Eriksson P, Cherfan P, Jonasson L. Effects of simvastatin on proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in hypercholesterolemic individuals. Inflammation 2011;34:225–30.10.1007/s10753-010-9227-ySuche in Google Scholar

24. Boekholdt SM, Hovingh GK, Mora S, Arsenault BJ, Amarenco P, Pedersen TR, et al. Very low levels of atherogenic lipoproteins and the risk for cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of statin trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:485–94.10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.615Suche in Google Scholar

25. Chasman DI, Giulianini F, MacFadyen J, Barratt BJ, Nyberg F, Ridker PM. Genetic determinants of statin-induced low-density lipoprotein cholesterol reduction: the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012;5:257–64.10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961144Suche in Google Scholar

26. Reiner Z. Resistance and intolerance to statins. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014;24:1057–66.10.1016/j.numecd.2014.05.009Suche in Google Scholar

27. Deng J, Wu G, Yang C, Li Y, Jing Q, Han Y. Rosuvastatin attenuates contrast-induced nephropathy through modulation of nitric oxide, inflammatory responses, oxidative stress and apoptosis in diabetic male rats. J Transl Med 2015;13:53.10.1186/s12967-015-0416-1Suche in Google Scholar

28. McGuire TR, Kalil AC, Dobesh PP, Klepser DG, Olsen KM. Anti-inflammatory effects of rosuvastatin in healthy subjects: a prospective longitudinal study. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:1156–60.10.2174/1381612820666140127163313Suche in Google Scholar

29. Sun X, Xu D, Li L, Shan B. Effects of rosuvastatin on post-infarction cardiac function and its correlation with serum cytokine level. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;10:10690–6.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Musial J, Undas A, Gajewski P, Jankowski M, Sydor W, Szczeklik A. Anti-inflammatory effects of simvastatin in subjects with hypercholesterolemia. Int J Cardiol 2001;77:247–53.10.1016/S0167-5273(00)00439-3Suche in Google Scholar

31. Rezaie-Majd A, Maca T, Bucek RA, Valent P, Müller MR, Husslein P, et al. Simvastatin reduces expression of cytokines interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 incirculating monocytes from hypercholesterolemic patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:1194–9.10.1161/01.ATV.0000022694.16328.CCSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Antonopoulos AS, Margaritis M, Lee R, Channon K, Antoniades C. Statins as anti-inflammatory agents in atherogenesis: molecular mechanisms and lessons from the recent clinical trials. Curr Pharm Des 2012;18:1519–30.10.2174/138161212799504803Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Tanaga K, Bujo H, Inoue M, Mikami K, Kotani K, Saito Y. Increased circulating malondialdehyde-modified LDL levels in patients withcoronary artery diseases and their association with peak sizes of LDL particles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:662–6.10.1161/01.ATV.0000012351.63938.84Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Hagita S, Osaka M, Shimokado K, Yoshida M. Oxidative stress in mononuclear cells plays a dominant role in their adhesion to mouse femoral artery after injury. Hypertension 2008;51: 797–802.10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098855Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Kumon Y, Nakauchi Y, Suehiro T, Shiinoki T, Tanimoto N, Inoue M, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines but not acute phase serum amyloid A or C-reactive protein, downregulate paraoxonase 1 (PON1) expression by HepG2 cells. Amyloid 2002;9:160–4.10.3109/13506120209114817Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Stadnyk AW, Baumann H, Gauldie J. The acute-phase protein response in parasite infection. Nippostrongylus brasiliensis and Trichinella spiralis in the rat. Immunology 1990;69:588–95.Suche in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery