Abstract

Objective

The effects of urapidil in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (IR) model were investigated using histopathological and biochemical methods.

Materials and methods

Forty Wistar albino rats were subjected to sham operation (Group 1), IR (Group 2), IR+dimethyl sulfoxide (Group 3), IR+urapidil 0.5 mg/kg (Group 4), and IR+urapidil 5 mg/kg (Group 5). Levels of MDA, TAS, TOS, SOD, MPO, NF-κB, caspase-3, and LC3B were measured.

Results and discussion

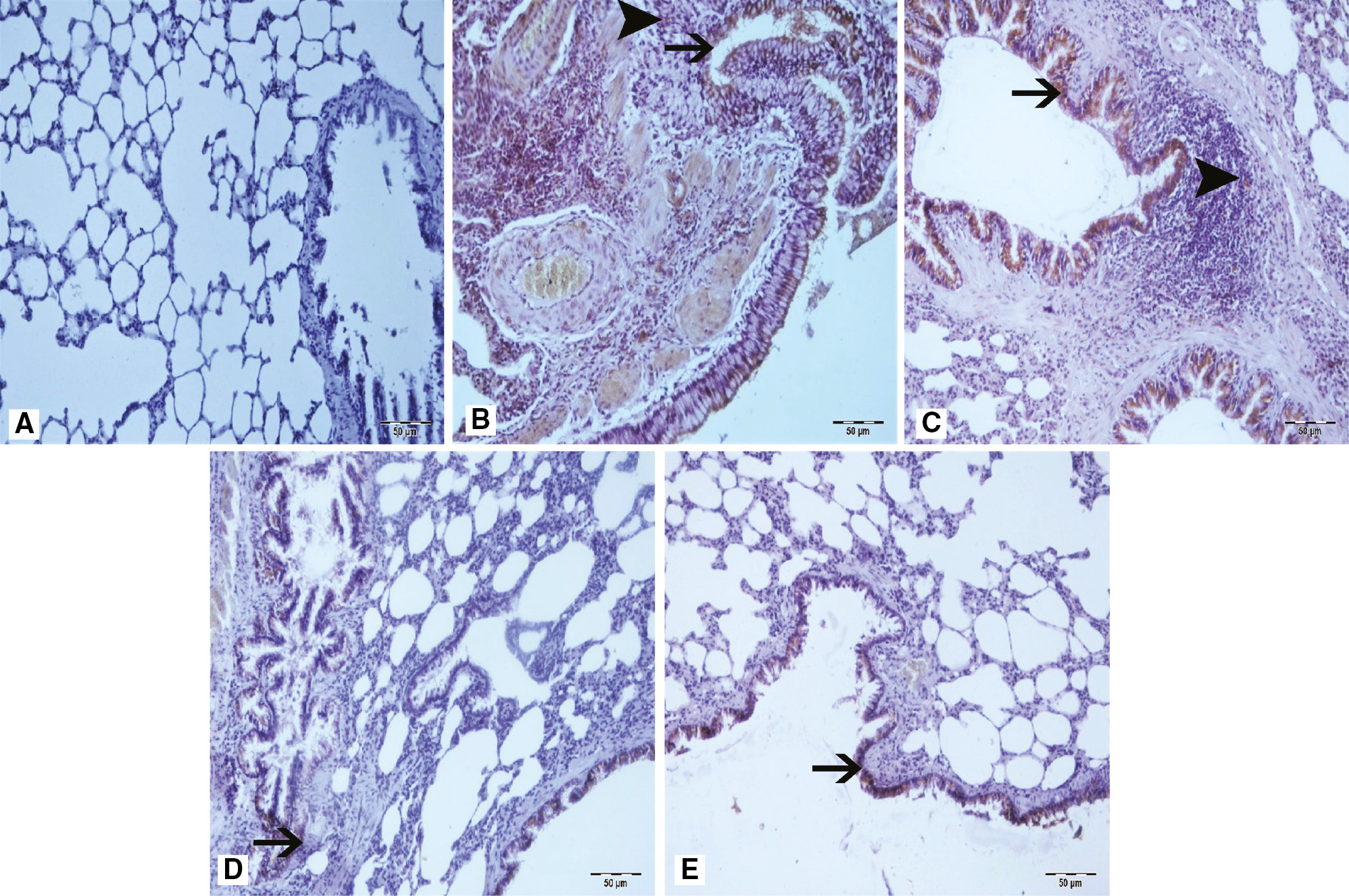

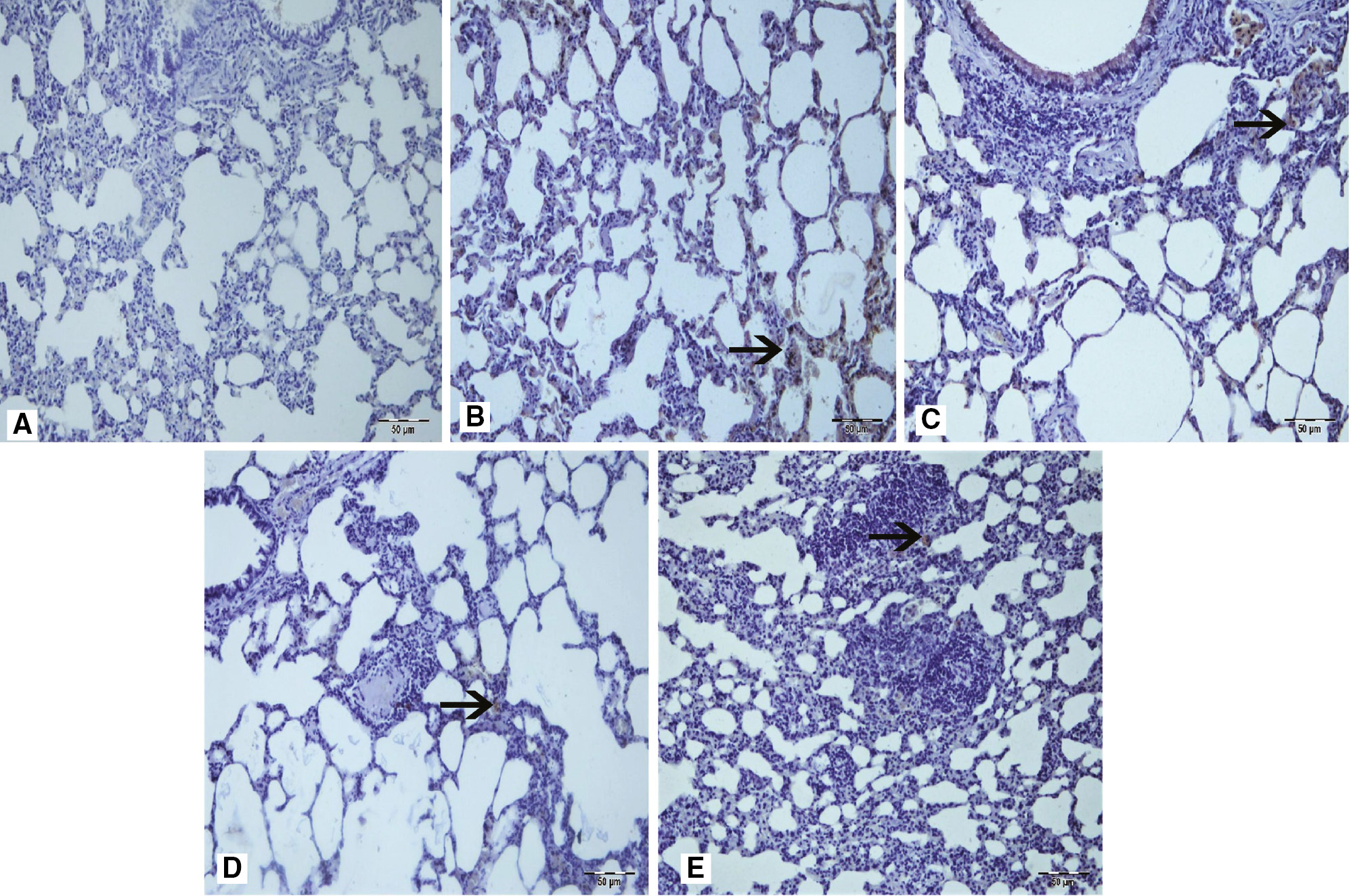

The groups 2 and 3 had significantly higher TOS and MPO levels than the sham group had (p < 0.001), whereas the TAS and SOD levels were significantly lower in Group 2 than in the sham group. In treatment groups, TAS and SOD levels increased, whereas TOS, MPO, and MDA levels decreased compared to Group 2. Caspase-3 and LC3B immunopositivities were seen at severe levels in Group 2 and 3. However, Group 4 and 5 were found to have lower levels of immunopositivity. Immunopositivity was observed in interstitial areas, peribronchial region, and bronchial epithelial cells. A moderate level of NF-κB immunopositivity was seen in Group 2 and 3.

Conclusion

Our results show that urapidil is one of the antioxidant agents and protects lung tissue from oxidant effects of intestinal IR injury.

Öz

Amaç

İntestinal iskemi-reperfüzyon (IR) modelinde urapidil’in etkileri histopatolojik ve biyokimyasal yöntemler kullanılarak araştırıldı.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Kırk adet Wistar albino sıçan sham operasyon (Grup 1), IR (Grup 2), IR+dimetil sülfoksit (Grup 3), IR+urapidil 0.5 mg/kg (Grup 4) ve IR+urapidil 5 mg/kg (Grup 5) olarak gruplandı. MDA, TAS, TOS, SOD, MPO, NF-κB, kaspaz-3 ve LC3B seviyeleri ölçüldü.

Bulgular ve tartışma

Grup 2 ve 3’te sham grubuna göre TOS ve MPO düzeylerinin anlamlı derecede yüksek, (p < 0.001), TAS ve SOD düzeyleri grup 2’de sham grubundan anlamlı derecede düşüktü. Tedavi gruplarında TAS ve SOD seviyeleri yükselirken, TOS, MPO ve MDA düzeyleri Grup 2’ye göre arttı. Kaspaz-3 ve LC3B immünopozitivitesi Grup 2 ve 3’te yoğun seviyelerde görüldü İnterstisyel bölgelerde, peribronşiyal bölgede ve bronşiyal epitel hücrelerinde immünopozitivite gözlendi. Grup 2 ve 3’te orta düzeyde bir NF-kappa B immünopozitivitesi görüldü.

Sonuç

Sonuçlarımız urapidil’in, antioksidan ajanlardan biri olduğu ve akciğer dokusunu bağırsak IR hasarının oksidan etkilerinden koruduğunu göstermiştir.

Introduction

Ischemia that causes cell injury results from the interruption of blood supply that is leading to lack of oxygen. Either arterial or venous occlusion or both may be the causes of the ischemia. Reperfusion following ischemia maintains the harmful effects of ischemia. This condition, known as ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury, is associated with the return of oxygen and metabolites, reactive oxygen species (ROS), cellular Ca2+ overload, activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), mitochondrial injury, and proinflammatory cytokines. Superoxide and hydroxyl radicals are released during the reperfusion contributing to the reperfusion injury [1]. Reperfusion makes additional paradoxical injury after the restoration of blood supply. Only ischemia and reperfusion following ischemia make IR injury, which may trigger an intense inflammatory response.

Generation of ROS leads to oxidative stress, apoptosis, cell damage, and inflammatory processes because ROS and their products harm DNA and mitochondrial membrane as well as make lipid peroxidation. The sources of ROS are not only the mitochondria but also the activated neutrophils and microglial cells [2], [3]. ROS induce inflammation through some cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [1]. Systemic ROS activates more leukocytes, increases the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, and result in vascular endothelial damage. The concentration of those free radicals that oxidize substances in vivo may be increased by many factors including environmental toxins, ionizing radiation, infections, smoking, alcohol consumption, aging, and emotional or psychological stress. Local IR injury may result in failures of remote organs such as lung by means of PMNs [4]. The common reason of the gastrointestinal ischemia is the interruption of blood supply of superior mesenteric artery or vein. While the mortality rate of this condition is too high (70%) the incidence of intestinal IR injury is relatively low (30,000 cases reported per annum in the USA) [5].

As inflammation does, ROS also induce apoptosis, which is one of the ways of elimination of the damaged, oncogenic, and genetically unstable cells in order to maintain the homeostasis [6]. Among caspases, caspase-3 is known as the most important effector of apoptosis, which has clues for its existence in histopathological specimens including DNA fragmentation, apoptotic chromatin condensation, apoptotic bodies, and dismantling of the cell [7], [8].

Fortunately, the harmful effects of free radicals are prevented by antioxidant mechanisms in the cell endogenously with scavenging free radicals. The main antioxidant enzymes are superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione (GSH) related enzymes (glutathione peroxidase [GPx], glutathione reductase [GR], and thioredoxin reductase). In order to maintain the antioxidant activity, the enzyme called SOD converts superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide [9]. Then, CAT and GPx convert hydrogen peroxide into water [9]. Some of the antioxidant substances like SOD, CAT, GSH-Px, malondialdehyde (MDA), copper, zinc, and iron are evaluated to make estimations indirectly about the activity of free radicals due to the short half-lives of free radicals [10].

The oxidative stress is an impairment of antioxidant systems buffering toxic oxidants. The oxidative stress is estimated by TOS (total oxidant status) and TAS (total antioxidant status). TAS demonstrates the ability of serum to quench free radicals [11]. Protein degradation is another necessary process for the life of the cell. Autophagy, which is one of the protein degradation mechanisms of all eukaryotic organisms, is required during starvation, differentiation, and normal growth control [12]. LC3B performs its useful work through the turnover of cellular macromolecules and organelles. LC3B, a lipidated form of microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), has been shown to participate in autophagosome formation in conditions such as neurodegenerative and neuromuscular diseases, tumorigenesis, and bacterial and viral infections in which autophagy occurs [13]. Thus LC3B, which is localized in pre-autophagosomes and autophagosomes, is a marker of autophagy [12].

The agent used in the current study, urapidil, is known as a sympatholytic, antihypertensive, alpha-adrenergic antagonist, and 5-HT receptor agonist [14], [15], [16]. Therefore, urapidil decreases the peripheral vascular resistance. Consequently, in the present study, it is aimed to investigate the effects of urapidil in intestinal IR-induced lung injury.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental protocols

According to the 3R principle, the power analysis test was performed on a 95% confidence interval in determining the number of subjects. A total of 40 subjects are needed to reject the null hypothesis when the probability (power) of the experimental and control survival curves of the power analysis is equal to 0.85. The probability of Type I error of the null hypothesis in this test is 0.05. Hence, it was calculated that eight rats would be sufficient for each group.

Forty female Wistar albino rats, each are 12–16 weeks old and weighing 200–250 g, were obtained from Atatürk University Animal Laboratory (Erzurum, Turkey) for the use of this study. After approval was granted by the Animal Care and Use Ethical Committee of the Atatürk University (No: E.1800040262/22, Date: 25.01.2018), the study was carried out at the Animal Laboratory of the Atatürk University in accordance with international guidelines.

The intestinal IR model was applied to the rats. The rats were fasted overnight but allowed to drink water ad libitum. Before the surgery, rats were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. The abdomens were shaved and washed with 10% povidone-iodine, and a 2-cm midline abdominal incision was performed using sterile techniques. After a median laparotomy, the animals were laid on the right side so that the mesentery of intestines removed from the abdomen was on the level of the aorta. The small bowel was exteriorized gently to the left onto a moist gauze, then the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was carefully isolated and ligated with an atraumatic microvascular clip. Then, the intestines were returned to the abdomen, which was closed with two small clamps afterward, and the animal was kept under anesthesia for a total of 2 h. The rats were placed on heating pads at 37°C throughout the experiment. For resuscitation, all animals received 25 mL/kg of 0.9% saline subcutaneously after the SMA occlusion. To allow restoration of blood flow to the intestine and reperfusion was started for 2 h. Between surgical interventions, the midline incision was with 3.0 silk suture. The rats were sacrificed at the end of reperfusion. The sham-operated group received laparotomy, and the group’s intestines were manipulated [17], [18].

Urapidil was commercially obtained and prepared in a 15% DMSO solution according to the kit protocol (Cat No: ab142959, Abcam). According to literature, 0.5, 6, and 10 mg/kg doses were used and positive results were observed [16], [19], [20], [21]. For this reason, different doses were evaluated in the pre-studies and 0.5 and 5 mg/kg resulted in the most favorable results and the study was planned at these doses.

Surgical procedures and treatment group

Group 1 (sham control, n=8): The animals were subjected to 1–2 cm incision from their abdominal regions. After reaching their peritoneum, they were closed. Three hours (1-h ischemia/2 h’ reperfusion) later, they were sacrificed.

Group 2 (IR, n=8): The peritoneum of the animals was reached through 1–2 cm incision from their abdominal regions. They were subjected to 1-h ischemia to superior mesenteric artery followed by 2 h reperfusion. Then, they were sacrificed after IR.

Group 3 (IR+15% DMSO, n=8): In addition to the surgical processes that were performed on the animals in Group 2, 15% DMSO was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the reperfusion.

Group 4 (IR+0.5 mg/kg urapidil, n=8): In addition to the surgical processes that were performed to the animals in Group 2, 0.5 mg/kg urapidil was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the reperfusion.

Group 5 (IR+5 mg/kg urapidil, n=8): In addition to the surgical processes that were performed to the animals in Group 2, 5 mg/kg urapidil was administered intraperitoneally 30 min before the reperfusion Table 1.

Abbreviations of the groups.

| Group 1 (n=8) | Group 2 (n=8) | Group 3 (n=8) | Group 4 (n=8) | Group 5 (n=8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham control | IR | IR+DMSO | IR+0.5 URA | IR+5 URA |

Biochemical assay

Lung tissues were taken out of the deep freeze and weighed on the day of the analysis. A 10% homogenate was created by adding phosphate buffer on the tissues and they were homogenized (IKA, Germany) at 12,000 rpm for 1–2min on ice. Homogenate tissue samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm at +4°C for 30 min to obtain the supernatant. Obtained supernatants were tested for TAS, TOS, SOD, MPO, and MDA levels.

The malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in the homogenate were measured using the method described by Ohkawa et al. [22]. The method entails the measurement of the supernatant obtained from the n-butanol phase of the pink colored product of the reaction between the thiobarbituric acid and the MDA in the homogenate sample at 95°C at 535 nm with a spectrophotometer (PowerWave™ XS, US). Homogenate tissue samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm at +4°C for 30 min to obtain the supernatant. Obtained supernatants were tested for TAS, TOS, SOD, and MPO levels.

The determination of TAS was carried out with the kit supplied by commercial means (Rel Assay Diagnostics, Ref. No. RL0024). The measurement was based on the reduction of the dark blue-green colored 2,2′-azino bis (3-ethyl benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical of the antioxidants in the sample to the colorless reduced ABTS form. The change in absorbance at 660 nm is correlated with the total antioxidant level. The kit contains a solution which is an E vitamin analog and classically referred to as “Trolox equivalent” as a stable antioxidant standard. The measurement of TOS was carried out using a commercially supplied kit (Rel Assay Diagnostics, Ref.No.: RL0005). The oxidants present in the sample promote the ferrous ion-chelator complex to the ferric ion. The resulting ferric ion in the acidic medium produces a complex colored by chromogen. The spectrophotometrically determined color intensity is related to the total amount of oxidant molecules present in the sample. The OSI was calculated as follows: OSI=([TOS, mmol H2O2 equivalent/L]/[TAS, mmol Trolox equivalent/L]×10) [23]. MPO determination is based on the kinetic measurement of the absorbance at a wavelength of 460 nm of the yellowish-orange colored complex form shaped as the result of the oxidation of MPO and the o-dianisidine, in the presence of H2O2. SOD was calculated after reacting with tetrazolium salt to form formazan dye by measuring the inhibition degree of this reaction at the wavelength of 560 nm in the spectrophotometer in cases where the effect of SOD enzyme was inadequate in the superoxide formed as the result of enzymatic reactions [24].

Histopathological and immunohistochemical examination

The lung was removed immediately, fixed in 10% neutral formalin for 24–48 h, and then processed to obtain paraffin blocks. Paraffin-embedded blocks were routinely processed; 5-μm thick sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and examined under a microscope (Olympus BX51, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Sections of each animal were also examined for the intensity of the immunopositivity by another veterinary pathologist for blind scoring.

Paraffin-embedded blocks were routinely processed; 5-μm thick sections were stained with immunohistochemistry. After deparaffinization, the slides were immersed in antigen retrieval solution (pH 6.0) and heated in the microwave for 15 min to unmasked antigens. The sections were then dipped in 3% H2O2 for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase. Sections were incubated at room temperature with the cleaved caspase-3 antibody (cat no. NB600-1235, dilution 1/200; Novus Biological, USA), NF-κB (Cat. no: ab7971, dilution 1/200; Abcam), and LC3B (Cat. No: sc-376404, dilution 1/200; Santa Cruz). The EXPOSE mouse and rabbit specific HRP/DAB detection IHC kit was used as follows: sections were incubated with goat anti-mouse antibody, then with streptavidin-peroxidase, and finally with 3,3′ diaminobenzidine+chromogen. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Immunoreactivity in the sections were graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe) [25], [26].

Quantification and statistical analysis

Comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test was applied where appropriate. For nonparametric values, whether there were differences between the groups or not was determined by means of Kruskal–Wallis test. Pairwise comparisons were made using Mann–Whitney U-test and Bonferroni correction was used as a post hoc test. Data are shown as means±SEM unless otherwise noted. Significance was set at α=0.05. SPSS software (ver. 18.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform statistical analyses.

Results

Biochemical results

Table 2 demonstrates the biochemical parameters of antioxidant (TAS and SOD) and oxidant (TOS, MPO, and MDA) parameters in the lung tissue among different treatment groups. Group 2 and 3 had significantly higher TOS and MPO levels than the control group had (p<0.001), whereas the TAS and SOD levels were significantly lower in the ischemia-reperfusion groups (Group 2 and 3) than in the control group. Additionally, MDA levels were higher in Group 3 when compared with the sham group. In treatment groups, TAS and SOD levels were found to be increased, while TOS, MPO, and MDA levels were decreased compared to Group 2. The treatment groups (Group 4 and 5) when compared with Group 3, in addition to the same changes in IR group levels, the MDA levels decreased directly as well correlated with the treatment dose.

The results of the biochemical parameters of all groups.

| Experimental groups n=8 | TAS (mmol/L) | TOS (μmol/L) | OSI (arbitrary unit) | SOD (U/mg protein) | MPO (U/g protein) | MDA (μmol/g protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham operation (1) | 1.170±0.193 | 8.185±0.777 | 0.720±0.158 | 149.013±18.386 | 259243.699±40912.486 | 73.373±7.726 |

| Ischemia/reperfusion (2) | 0.799±0.077 | 10.815±1.220 | 1.366±0.223 | 106.675±15.732 | 414546.909±53539.565 | 100.763±42.745 |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+dimethyl sulfoxide (3) | 0.769±0.161 | 10.551±1.023 | 1.418±0.296 | 110.808±11.615 | 409538.568±58899.513 | 100.314±15.162 |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+urapidil 0.5 mg/kg (4) | 1.133±0.282 | 8.601±0.930 | 0.784±0.138 | 146.344±25.488 | 298721.625±52009.801 | 76.783±18.361 |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+urapidil 5 mg/kg (5) | 1.184±0.220 | 8.199±0.832 | 0.710±0.128 | 149.757±48.216 | 262571.265±56715.628 | 72.533±10.989 |

| p Value (Meaningful intergroup comparisons) | 0.000 (1–2) | 0.000 (1–2) | 0.000 (1–2) | 0.000 (1–2) | 0.000 (1–2) | |

| 0.001 (1–3) | 0.000 (1–3) | 0.046 (1–3) | 0.000 (1–3) | 0.000 (1–3) | 0.001 (1–3) | |

| 0.006 (2–4) | 0.001 (2–4) | 0.000 (2–4) | 0.002 (2–4) | 0.001 (2–4) | ||

| 0.000 (2–5) | 0.000 (2–5) | 0.000 (2–5) | 0.031 (2–5) | 0.000 (2–5) | ||

| 0.007 (3–4) | 0.001 (3–4) | 0.000 (3–4) | 0.003 (3–4) | 0.001 (3–4) | 0.014 (3–4) | |

| 0.001 (3–5) | 0.000 (3–5) | 0.000 (3–5) | 0.043 (3–5) | 0.000 (3–5) | 0.001 (3–5) |

TAS, Total antioxidant status; TOS, total oxidant status; OSI, oxidative stress index; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MPO, myeloperoxidase; MDA, malondialdehyde. Data are presented as mean±SD.

In the comparison of the TAS and TOS levels between the ischemia-reperfusion groups (Group 2 and 3) and the treatment groups (Group 4 and 5), the higher dose of urapidil made better results than the lower dose of urapidil according to the p-values. Knowing the fact that the p-value of the SOD levels between Group 2 and 5 (p=0.031) is bigger than Group 2 and 4 (p=0.002). The results of OSI showed that there is no difference between the two doses of urapidil according to the p-values measured. Lastly, the MDA level is found to be significantly decreased in treatment groups (Group 4 and 5), compared to Group 3.

Immunohistochemical examination

According to the results of immunohistochemical staining with caspase-3, LC3B, and NF-κB antibodies, a statistically significant difference between sham group (Group 1) and the treatment groups (Group 4 and 5) occurred (p<0.05, Table 3). Severe levels of caspase-3 and LC3B immunopositivity was seen in ischemic groups (Group 2 and 3). However lower levels of immunopositivity were found on the treatment groups (Group 4 and 5). Immunopositivity was observed in interstitial areas, peribronchial region, and bronchial epithelial cells (Figures 1 and 2). NF-κB immunopositivity was seen in the ischemic groups (Group 2 and 3) at moderate levels, but at mild levels in the treatment groups (Group 4 and 5). Immunopositivity was predominantly seen in interstitial areas (Figure 3). According to these histopathological examinations, we suggest that urapidil is among the antioxidant drugs because it protected the lung tissue from oxidant effects after an intestinal IR injury.

Evaluation of immunopositivity in the lung tissue samples of the groups: 0 (none), 1 (light), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe).

| Experimental groups | Caspase 3 | LC3B | NF-κB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham operation (1) | 0.37±0.18a | 0.50±0.18a | 0.12±0.12a |

| Ischemia/reperfusion (2) | 2.75±0.16b | 2.87±0.12b | 2.37±0.18b |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+dimethyl sulfoxide (3) | 2.62±0.18b | 2.62±0.18b | 2.37±0.18b |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+urapidil 0.5 mg/kg (4) | 1.87±0.12c | 1.87±0.12c | 1.37±0.18c |

| Ischemia/reperfusion+urapidil 5 mg/kg(5) | 1.71±0.18c | 1.57±0.20c | 1.28±0.18c |

All data were presented in mean (±) standard error of means (SEM). a,b,cp<0.05 vs. other group.

Staining of samples with Caspase-3.

(A) Sham group, (B) arrow at interstitial areas of Group 3, (C) arrow at interstitial areas and arrowhead at peribronchial areas with severe caspase-3 immunopositivity of IR groups (Group 2 and 3), (D) arrow at interstitial areas of Group 4, (E) arrow at interstitial areas with mild caspase-3 immunopositivity of Group 5. IHC.

Staining of samples with LC3B.

(A) Sham group, (B) arrow at bronchial epithelium and arrowhead at peribronchial areas of Group 3, (C) arrow at bronchial epithelium and arrowhead at peribronchial areas with severe LC3B immunopositivity of IR groups (Group 2 and 3), (D) arrow at bronchial epithelium of Group 4, (E) arrow at bronchial epithelium with mild LC3B immunopositivity of Group 5. IHC.

Staining of samples with NF-κB.

(A) Sham group, (B) arrow at interstitial areas of Group 3, (C) arrow at interstitial areas with moderate NF-κB immunopositivity of IR groups (Group 2 and 3), (D) arrow at interstitial areas of Group 4, (E) arrow at interstitial areas with mild NF-κB immunopositivity (arrowhead) of Group 5. IHC.

Discussion

In the present study, intestinal IR model on rats was used to investigate the oxidant effects of intestinal IR on lungs as a remote organ and the effects of urapidil as a drug to detect whether it has an antioxidant effect or not by using biochemical and immunohistochemical methods. There are lots of conditions associated with intestinal IR like abdominal injuries, surgery, bowel infection, sepsis, small bowel transplantation, and multiple organ failure [27]. PMNs are told as key players with their complex effects on intestinal IR injury [28]. A study suggested that the resident PMNs are effective at altering mucosal function during reperfusion [29]. MPO is told to be contributing to PMNs at tissue damage of IR as well. There are cytokines associated with intestinal IR such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α [30].

Among visceral organs, lungs can be suggested as more resistant to ischemia because the arterial supply coming from pulmonary and bronchial arteries is not the only oxygen source of supply for lungs. Apart from those, alveoli of the lungs contain oxygen as well [31]. Formation of acute lung injury is associated with some factors including excessive ROS, activated PMNs, and some inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10) [32]. Those activated PMNs affect the epithelial cells of the lungs, leading to acute lung injury by apoptotic mechanisms [33]. TNF-α and IL-6 enroll neutrophils into the lungs, then induce the production of IL-1β which accumulates neutrophils [34].

Literature tells that acute lung injury following intestinal ischemia is related to pulmonary neutrophil sequestration, depletion of lung tissue ATP, alveolar endothelial cell disruption, and increased microvascular permeability and the reduction of the effect of intestinal ischemia-reperfusion on the lung by means of anti-TNF antibodies indicates that lung injury after intestinal ischemia is related to elevated TNF [35]. In the literature, it is emphasized that ATP depletion in lung tissue occurs after reperfusion even within 15 min [36]. A study found that microvascular permeability increased in lung tissue after intestinal IR and MPO level, which indicates that neutrophil accumulation in the lungs increased seven-fold after 120 min of ischemia and 15 min of reperfusion [37].

MPO (myeloperoxidase), Nuclear Factor Kappa-B (NF-κB), and MDA (malondialdehyde) help us predict inflammatory status. MPO is excreted by activated neutrophils and it reflects the number and infiltration amount of them [38]. MPO converts hydrogen peroxide into hypochlorite (OCl−) and radicalized oxygen species (O2˙−, ONOO˙−). Those activated PMNs exaggerate the amount of ROS like superoxide and H2O2 in the lung tissue [39], [40]. NF-κB is a pro-inflammatory transcription factor that regulates the expression of the proinflammatory molecules [41]. After the reperfusion, alveolar macrophages and endothelial cells increase ROS generation that leads to activation of NF-κB and some proinflammatory cytokines like IL-8, TNF-α [31].

As mentioned before TAS and TOS estimate the status of the oxidative stress. While TAS is negatively correlated with the number of free radicals of serum, but TOS and OSI have a positive correlation in that regard. There are many factors affecting TAS and TOS levels like ischemia including stress, sun ray, smoking, drugs, aging, radioactivity, infections, hemorrhage, traumas, and long-term metabolic diseases [42].

In this study, there was no significant difference between treatment groups and sham group. TAS levels are found as increased significantly in Group 4 and 5 compared to those of Group 2, but TOS levels are found as decreased significantly in Group 4 and 5 compared to those of Group 2 (Table 2). Those results show that urapidil, in fact, had antioxidant effects on lung tissue. Therefore, this study showed that urapidil has a protective effect on lung tissue after IR injury in rats.

The drug used in this study, i.e. urapidil, is known as a sympatholytic, antihypertensive, alpha-adrenergic antagonist, and 5-HT receptor agonist. Hence, urapidil decreases the peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure as well as increases the cardiac output [14], [15], [16]. Table 2 shows that in one ischemia-reperfusion group (Group 2) of our study the levels of TAS and SOD reduced compared to those of the sham group. IR seems to decrease TAS and SOD from the physiological level it should be. However, the levels of TOS, OSI, MPO, and MDA are found as increased according to the sham group. Those alternations are correlated with the literature [43], [44]. On the other hand, the groups treated with urapidil (Group 4 and 5) showed similar levels with the sham group, which suggests that urapidil prevented those levels from alternating to pathological levels. Although there is a limited number of studies on the preventive effects of urapidil, this result may be due to the inhibitory effect of urapidil against activated neutrophils [30], [45]. Besides, there is a study showing that urapidil treatment decreased MDA and apoptosis levels and increased SOD levels [16]. Some studies drew attention on dilating pulmonary vascular bed feature of urapidil on patients with pulmonary hypertension [46]. So, urapidil may have antioxidant effects on IR injury because of its vasodilator effect.

The levels of TOS, OSI, MPO, and MDA are similar between the sham operation group and the groups treated with urapidil, but lower than IR groups (2 and 3). Moreover, because the levels of TAS and SOD are resulted similar between the sham group and the groups treated with urapidil (4 and 5), but higher than IR groups (2 and 3), hence, it can be suggested that urapidil acted as an antioxidant drug in trials. Some recent studies had similar results that suggest urapidil decreases MDA and apoptosis but increases SOD and GPx [16]. In another study of testicular torsion which makes IR, urapidil prevented cellular damage in testicular tissue when it is treated before detorsion [16]. According to the results of the current study, as seen in Table 2, two doses of urapidil made no difference on animals because there was no statistical difference between Group 4 and 5 in any parameter. The levels of SOD alternate similarly between ischemia and sepsis. A study showed that sepsis SOD activity in the lung tissue is significantly lowered, but MPO activity and MDA level increased [43]. Similarly, the present study showed a decrease in SOD level and an increment in MPO and MDA levels in IR. Another study also reported that SOD levels in the lung tissue decreased in sepsis [44].

IR may also lead to pathological apoptosis in order to maintain the homeostasis because the damaged cells need to be eliminated. Among the effectors of apoptosis, the caspase-3 is known as the most important one and is used as a marker on pathological specimens to detect apoptotic clues including DNA fragmentation, apoptotic chromatin condensation, the formation of apoptotic bodies, and dismantling of the cell [7], [8], [16]. There were many apoptotic cells in the specimens of pathological samples of this study that show intestinal IR caused lung injury with apoptosis. Nevertheless, in the urapidil treated groups (4 and 5), apoptotic cell patterns were similar to the sham group. Damaged organelles, pathogens, and protein aggregates inside cells may also be eliminated by the autophagy process that uses double-membrane vesicles called autophagosome for degradation [47]. While apoptosis is detected on histopathological specimens especially by means of caspase-3 activity, autophagy is monitored by LC3B activity [47].

Conclusions

Mesenteric intestinal IR injury should be one of the research areas in medicine to eliminate mortal outcomes of patients. In parallel with the literature, it was shown that while the oxidant parameters increased in mesenteric intestinal IR injury, the antioxidants such as SOD and TAS decreased. The immunopositivity of NF-κB, LC3B, and caspase-3 molecules were shown to increase with IR injury. In the present investigation, it was first presented from the literature that urapidil reduced the oxidative damage caused by ischemia-reperfusion injury and the level of molecules that are evidence of cell lysis. As a drug, urapidil showed promising beneficial effects on the lung tissue in this study. As a conclusion, it can be said that according to the results, urapidil prevented the harmful effects of IR on the lungs.

Acknowledgements

There was no financial support organization in the implementation of the study. We would like to thank all participants for contributing in the present survey. Our study was presented as an oral presentation in ERPA International Congresses on Education, 2018.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Tao T, Chen F, Bo L, Xie Q, Yi W, Zou Y, et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects mouse liver against ischemia–reperfusion injury through anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptosis properties. J Surg Res 2014;191:231–8.10.1016/j.jss.2014.03.067Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Piantadosi CA, Zhang J. Mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species after brain ischemia in the rat. Stroke 1996;27:327–32.10.1161/01.STR.27.2.327Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Matsuo Y, Kihara T, Ikeda M, Ninomiya M, Onodera H, Kogure K. Role of neutrophils in radical production during ischemia and reperfusion of the rat brain: effect of neutrophil depletion on extracellular ascorbyl radical formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1995;15:941–7.10.1038/jcbfm.1995.119Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Klausner JM, Anner H, Paterson IS, Kobzik L, Valeri CR, Shepro D, et al. Lower torso ischemia-induced lung injury is leukocyte dependent. Ann Surg 1988;208:761.10.1097/00000658-198812000-00015Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Tendler DA. Acute intestinal ischemia and infarction. Seminars in gastrointestinal disease. 2003;14:66–76.Search in Google Scholar

6. Simon H-U, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000;5:415–8.10.1023/A:1009616228304Search in Google Scholar

7. Liu X, He Y, Li F, Huang Q, Kato TA, Hall RP, et al. Caspase-3 promotes genetic instability and carcinogenesis. Mol Cell 2015;58:284–96.10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Porter AG, Jänicke RU. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ 1999;6:99.10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Wang B, Peng L, Zhu L, Ren P. Protective effect of total flavonoids from Spirodela polyrrhiza (L.) Schleid on human umbilical vein endothelial cell damage induced by hydrogen peroxide. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2007;60:36–40.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.05.020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Leff JA. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, in Free radicals in diagnostic medicine. Springer, 1994:199–213.10.1007/978-1-4615-1833-4_15Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Baysal Z, Cengiz M, Ozgonul A, Cakir M, Celik H, Kocyigit A. Oxidative status and DNA damage in operating room personnel. Clin Biochem 2009;42:189–93.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.09.103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 2000;19:5720–8.10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720Search in Google Scholar

13. Martinet W, Knaapen MW, Kockx MM, De Meyer GR. Autophagy in cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med 2007;13:482–91.10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.004Search in Google Scholar

14. Eeckhout E, Kern M. The coronary no-reflow phenomenon: a review of mechanisms and therapies. Eur Heart J 2001;22:729–39.10.1053/euhj.2000.2172Search in Google Scholar

15. Schwietert H, Wilhelm D, Wilffert B, van Zwieten PA. Differences between full and partial α-adrenoceptor agonists in eliciting phasic and tonic types of responses in the longitudinal smooth muscle of the rat portal vein. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1991;344:206–12.10.1007/BF00167220Search in Google Scholar

16. Meštrović J, Pogorelić Z, Drmić-Hofman I, Vilović K, Todorić D, Popović M. Protective effect of urapidil on testicular torsion–detorsion injury in rats. Surg Today 2017;47:393–8.10.1007/s00595-016-1388-3Search in Google Scholar

17. Polat B, Albayrak A, Halici Z, Karakus E, Bayir Y, Demirci E, et al. The effect of levosimendan in rat mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Invest Surg 2013;26:325–33.10.3109/08941939.2013.806615Search in Google Scholar

18. Albayrak Y, Halici Z, Odabasoglu F, Unal D, Keles ON, Malkoc I. The effects of testosterone on intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in rats. J Invest Surg 2011;24:283–91.10.3109/08941939.2011.591894Search in Google Scholar

19. Weismann D, Kleinbrahm K, Hu K, Fassnacht M, Frantz S, Ertl G, et al. Prevention of hypertensive crises in rats induced by acute and chronic norepinephrine excess. Horm Metab Res 2010;42:803–8.10.1055/s-0030-1262782Search in Google Scholar

20. Ittner K, Bucher M, Zimmermann M, Grobecker HE, Krämer BK, Taeger K, et al. Effect of three different doses of urapidil on blood glucose concentrations in the streptozotocin diabetic rat. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2002;19:504–9.10.1017/S0265021502000820Search in Google Scholar

21. Buñag RD, Thomas CV, Mellick JR. Ketanserin versus urapidil: age-related cardiovascular effects in conscious rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2002;435:85–92.10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01557-6Search in Google Scholar

22. Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem 1979;95:351–8.10.1016/0003-2697(79)90738-3Search in Google Scholar

23. Erel O. A new automated colorimetric method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin Biochem 2005;38:1103–11.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.08.008Search in Google Scholar

24. Sun Y, Oberley LW, Li Y. A simple method for clinical assay of superoxide dismutase. Clin Chem 1988;34:497–500.10.1093/clinchem/34.3.497Search in Google Scholar

25. Aktaş MS, Kandemir FM, Ozkaraca M, Hanedan B, Kirbas A. Protective effects of rutin on acute lung injury induced by oleic acid in rats. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg 2017;23:445–51.Search in Google Scholar

26. Onk D, Onk OA, Erol HS, Özkaraca M, Çomaklı S, Ayazoğlu TA, et al. Effect of melatonin on antioxidant capacity, ınflammation and apoptotic cell death in lung tissue of diabetic rats. Acta Cir Bras 2018;33:375–85.10.1590/s0102-865020180040000009Search in Google Scholar

27. Carden DL, Granger DN. Pathophysiology of ischaemia–reperfusion injury. J Pathol 2000;190:255–66.10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<255::AID-PATH526>3.0.CO;2-6Search in Google Scholar

28. Wu MC, Brennan FH, Lynch JP, Mantovani S, Phipps S, Wetsel RA, et al. The receptor for complement component C3a mediates protection from intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injuries by inhibiting neutrophil mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:9439–44.10.1073/pnas.1218815110Search in Google Scholar

29. Kubes P, Hunter J, Granger DN. Ischemia/reperfusion-induced feline intestinal dysfunction: importance of granulocyte recruitment. Gastroenterology 1992;103:807–12.10.1016/0016-5085(92)90010-VSearch in Google Scholar

30. Grootjans J, Lenaerts K, Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruïne AP, van Bijnen AA, et al. Human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion–induced inflammation characterized: experiences from a new translational model. Am J Pathol 2010;176:2283–91.10.2353/ajpath.2010.091069Search in Google Scholar

31. Den Hengst WA, Gielis JF, Lin JY, Van Schil PE, De Windt LJ, Moens AL. Lung ischemia-reperfusion injury: a molecular and clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010;299:H1283–99.10.1152/ajpheart.00251.2010Search in Google Scholar

32. Chen X, Yang X, Liu T, Guan M, Feng X, Dong W, et al. Kaempferol regulates MAPKs and NF-κB signaling pathways to attenuate LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2012;14:209–16.10.1016/j.intimp.2012.07.007Search in Google Scholar

33. Martin TR, Nakamura M, Matute-Bello G. The role of apoptosis in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S184–8.10.1097/01.CCM.0000057841.33876.B1Search in Google Scholar

34. Goodman RB, Pugin J, Lee JS, Matthay MA. Cytokine-mediated inflammation in acute lung injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2003;14:523–35.10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00059-5Search in Google Scholar

35. Caty MG, Guice KS, Oldham KT, Remick DG, Kunkel SI. Evidence for tumor necrosis factor-induced pulmonary microvascular injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Surg 1990;212:694.10.1097/00000658-199012000-00007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Schmeling DJ, Caty MG, Oldham KT, Guice KS, Hinshaw DB. Evidence for neutrophil-related acute lung injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Surgery 1989;106:195–202.Search in Google Scholar

37. Cavriani G, Domingos HV, Soares AL, Trezena AG, Ligeiro-Oliveira AP, Oliveira-Filho RM, et al. Lymphatic system as a path underlying the spread of lung and gut injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in rats. Shock 2005;23:330–6.10.1097/01.shk.0000157303.76749.9bSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Guo R-F, Ward PA. Role of oxidants in lung injury during sepsis. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007;9:1991–2002.10.1089/ars.2007.1785Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Victor VM, Rocha M, Esplugues JV. Role of free radicals in sepsis: antioxidant therapy. Curr Pharm Des 2005;11:3141–58.10.2174/1381612054864894Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Lang JD, McArdle PJ, O’Reilly PJ, Matalon S. Oxidant- antioxidant balance in acute lung injury. Chest 2002;122: 314S–20S.10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.314SSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Chang X, Luo F, Jiang W, Zhu L, Gao J, He H, et al. Protective activity of salidroside against ethanol-induced gastric ulcer via the MAPK/NF-κB pathway in vivo and in vitro. Int Immunopharmacol 2015;28:604–15.10.1016/j.intimp.2015.07.031Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Çavdar C, Sifil A, Çamsarı T. Reactive oxygen particles and antioxidant defence. Office J Turk Nephrol Assoc 1997;3–4:92–95.Search in Google Scholar

43. Ozturk E, Demirbilek S, Begec Z, Surucu M, Fadillioglu E, Kirimlioglu H, et al. Does leflunomide attenuate the sepsis-induced acute lung injury? Pediatr Surg Int 2008;24:899.10.1007/s00383-008-2184-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Demirbilek S, Ersoy MO, Demirbilek S, Karaman A, Akin M, Bayraktar M, et al. Effects of polyenylphosphatidylcholine on cytokines, nitrite/nitrate levels, antioxidant activity and lipid peroxidation in rats with sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:1974–8.10.1007/s00134-004-2234-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Matthijsen RA, Huugen D, Hoebers NT, de Vries B, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Aratani Y, et al. Myeloperoxidase is critically involved in the induction of organ damage after renal ischemia reperfusion. Am J Pathol 2007;171:1743–52.10.2353/ajpath.2007.070184Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Langtry HD, Mammen GJ, Sorkin EM. Urapidil. Drugs 1989;38:900–40.10.2165/00003495-198938060-00005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Cemma M, Brumell JH. Interactions of pathogenic bacteria with autophagy systems. Curr Biol 2012;22:R540–5.10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery