Abstract

Background

To be able to prevent morbid obesity in the long-term, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is one of the most effective surgical interventions. However, leakage and bleeding from the stapler line are significant complications. The aim of this study was to determine the role of the levels of plasma presepsin in the detection of stapler leakage.

Materials and methods

The study included 300 patients with LSG due to morbid obesity and 40 control subjects. Before any medical treatment was applied, blood samples were taken from patients at 12 h preoperatively and on days 1, 3, and 5 postoperatively. Evaluation was made of plasma presepsin levels, white blood count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP) and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), in all patients with sleeve gastrectomy line leakage.

Results

The WBC, CRP, NLR and presepsin values measured on days 1, 3 and 5 postoperatively were determined to be higher in patients with leakage compared to those without. The predictive value of presepsin (p = 0.001), CRP (p = 0.001) and NLR (p = 0.001) was determined to be statistically significantly higher than that of WBC (p = 0.01).

Conclusion

The results of the study suggest that presepsin levels could have a role in the detection and follow-up of stapler line leaks after LSG. Elevated presepsin levels, on postoperative day 1 in particular, could have a key role in the early detection of possible complications which are not seen clinically.

Öz

Amaç

Laparoskopik sleeve gastrektomi (LSG), uzun vadede morbid obeziteyi önlemek için en etkili cerrahi girişimlerden biridir. Bununla birlikte, zımba hattından sızıntı ve kanama önemli komplikasyonlardır. Bu çalışmanın amacı, stapler hattı sızıntısının tespitinde plazma presepsin düzeylerinin rolünü belirlemektir.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Çalışmaya morbid obezite nedeniyle LSG’li 300 hasta ve 40 kontrol olgusu dahil edildi. Herhangi bir medikal tedavi uygulanmadan, preoperatif 12 saat önce ve postoperatif 1., 3. ve 5. günlerde kan örnekleri alındı. Sleeve gastrektomi hattı sızıntısı olanlarla beraber tüm hastalarda plazma presepsin düzeyleri, beyaz kan sayımı (WBC), C-reaktif protein (CRP) ve Nötrofil-Lenfosit oranı (NLR) değerlendirildi.

Bulgular

Postoperatif 1., 3. ve 5. günlerde ölçülen WBC, CRP, NLR ve Presepsin değerlerinin sızıntı olan hastalarda, olmayanlara göre daha yüksek olduğu belirlendi. Presepsinin prediktif değeri (p = 0.001), CRP (p = 0.001) ve NLR (p = 0.001), WBC’den istatistiksel olarak anlamlı derecede yüksek bulundu (p = 0.01).

Sonuç

Çalışmanın sonuçları presepsin düzeylerinin, LSG sonrası oluşan zımba hattı kaçaklarının saptanmasında ve izlenmesinde rol oynayabileceğini düşündürmektedir. Yükselen presepsin düzeylerinin, özellikle postoperatif 1. günde, klinik olarak görülmeyen olası komplikasyonların erken tespitinde anahtar rol oynayabilir.

Introduction

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) was first described by Gagner in 2003 and has become one of the most effective surgical interventions for the prevention of morbid obesity in the long term [1]. Leakage and bleeding from the staple line are the complications with the greatest effect on morbidity and mortality following LSG surgery [2], [3]. Staple line leaks after LSG have been reported as 0.5%–20% in several studies [4], [5], [6]. Despite advances in stapler technology, anastomotic leaks remain a serious problem for surgeons [7], [8]. The gastroesophageal junction and proximal gastric region, known as the His angle, is the most common area of leakage [9], [10]. Technical insufficiencies, insufficient blood circulation, sepsis, and local ischemia resulting from inadequate oxygenation are common causes of stapler leaks [11], [12]. Early leaks manifest with sudden onset of abdominal pain, tachycardia and fever. Early detection of leakage is an important problem, especially in patients with late-onset leaks or inpatients who cannot be diagnosed after the abdominal examinations [13]. The most commonly used laboratory parameters for detecting leaks are white blood count (WBC) (leukocyte) and C-reactive protein (CRP) values [14]. The soluble CD14 subtype (sCD14-ST) presepsin was identified by Yaegashi et al. [15]. Cluster of differentiation 14 (CD14) is a multifunctional glycoprotein mostly expressed on monocyte/macrophage membrane surfaces. There is also minimal distribution of CD14 on the cell surface of neutrophils (mCD14), which functions as a specific receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) and LPS-binding proteins (LPBs). When CD14 is released from the cell membrane, the LPS-LBP-CD14 complex is released into the circulation providing soluble CD14 (sCD14), which is also directly secreted by hepatocytes [16], [17]. In conditions of inflammation, plasma protease activity produces sCD14 fragments. The 64-amino acid N-terminal fragments form the sCD14 subtype (sCD14-ST), which has recently been renamed presepsin [18]. In several recent studies, the role of presepsin has been evaluated as a biomarker in adults. According to the results of those studies, presepsin seems to provide advantages of an earlier increase in blood levels, higher sensitivity and specificity, and prognostic value during inflammatory stress compared to the most well-known and widely-used markers of CRP and procalcitonin (PCT) [19], [20], [21].

The most important factor in reducing morbidity and mortality caused by stapler line leaks is early diagnosis [22], [23]. The aim of this study was to determine the utility of plasma presepsin levels in the detection of stapler leaks and in monitoring leakage together with WBC, CRP and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR).

Materials and methods

Patients

This prospective study, conducted between April 2016 and July 2016, included 300 patients with LSG due to morbid obesity and 40 control subjects. Approval for the study was granted by the Local Ethics Committee (no: 2016/96).

The LSG group comprised 255 females and 45 males with a median age of 41 years (range: 19–60 years) and mean body mass index (BMI) of 42.7. Staple line leakage developed in 9 patients (3%) (6 females, 3 males; median age: 40 years (range: 19–56 years); mean BMI: 43.2). According to the Clavien-Dindo Classification after interventional procedures or surgical interventions for stapler line leakage, four cases were grade IIIa (44.5%), 2 (22.2%) grade IIIb, 1 (11.1%) grade IVa, 1 (11.1%) grade IVb, and 1 (11.1%) grade V.

Control group

The control group was formed of a total of 40 obese patients (21 females, 19 males) with a median age of 47 years (range: 19–76 years) and mean BMI of 42.7, classified as ASA class I and II who were not accepted for obesity surgery. Although the reference values of presepsin in healthy individuals have been reported as 60.1–365 pg/mL [24], there are no determined reference values at an international level. The presepsin levels of the control group were used to evaluate the reliability of presepsin as an indicator of the integrity of the staple line. The control group received no medications and there was no evidence of local or systemic infection, such as abscess or inflammation in this group.

Method

Blood samples were taken from the patients at 12 h preoperatively and then on days 1, 3 and 5 postoperatively. The patients had not received any medical treatment, had no local or systemic infection findings in the preoperative examinations and tests, and had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of I–III. Of the patients with LSG line leakage, evaluation was only made of those who underwent percutaneous drainage on the 5th day or later. Preoperatively, enoxaparin (0.4 mL, subcutaneous 1×1) was administered. Postoperatively, i.v. hydration, ranitidine hydrochloride (1×1, i.v.), tenoxicam (3×1, i.v.), and enoxaparin (0.4 mL, subcutaneous, 1×1) were administered to the patients. Anastomotic leaks were determined based on physical examination, laboratory tests, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and oral/i.v. contrast-enhanced CT. 4.5 g 3×1 i.v. Piperacillin sodium was administered to the patients with leakage.

Blood samples were taken 12 h preoperatively and before any medical treatment. The normal CRP (0.01–0.5 mg/dL), WBC (4–11×103/μL) and NLR values were defined according to the reference values used in our hospital laboratories. Blood samples were obtained by venipuncture into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) blood collection tubes and immediately centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min. After centrifugation, plasma samples were stored at −80°C until analysis (maximum, 3 months). The samples were thawed only once. Plasma presepsin (item number: 1110-4000-Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Japan) levels were determined using the chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay method according to the manufacturer’s recommendations with the PATHFAST® immunoassay analytical system (PROGEN Biotechnik GmbH, Germany; Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Japan). Presepsin levels were reported as pg/mL.

Pre-operational evaluation

Prior to the LSG, all patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team in accordance with the hospital protocol. Routine evaluations were also made with gastroscopy, ultrasonography, ECG, ECO and pulmonary function test. Patients with an eating disorder, adrenal pathology or Barrett esophagus were excluded from the study.

Anesthesia protocol

Patients who were admitted to the hospital 1 day before the operation were brought to the operating room dressed with antiembolic stockings. According to the ideal weight, between 2 and 5 mg propofol and according to the actual weight, 0.5 mg rocuronium were administered. After intubation, 150 μg of fentanyl, 100 mg of tramadol, 50 mg of ranitidine and 8 mg of andesone were routinely administered. Starting from 0.05 μg/kg/min dose of remifentanil and Sevofluran MAC 0.9 was titrated in respect of blood pressure and heart rate to provide anesthesia maintenance.

Postoperatively, patients were transferred to the Postoperative Anaesthesia Care Unit (PACU) or to the relevant ward according to comorbidities and intraoperative problems. Mobility and respiratory physiotherapy were initiated from the 2nd postoperative hour.

Surgical technique

All surgical procedures were performed using the laparoscopic technique. Pneumoperitoneum was formed by entering the abdomen with a 10 mm trocar, which was entered from the left hypochondrium. A total of five trocars were placed in the form of an upward facing curve extending from the right flank area to the right hypochondrium and left flank area. The gastrocolic ligament was opened using the ultrasonic energy devices (Harmonic, Ligasure) in the vicinity of the large curvature of the stomach. The gastrocolic ligament was dissected from the His angle proximal to the pylorus distal and the stomach was released. Left crural dissection was routinely performed to evaluate the presence of a hiatal hernia and to fully mobilize the fundus. In the 36F bougie guided by the anesthesia team, the stomach resection was performed with an endoscopic stapler (Echelon, Endo GIA) starting at 3–4 cm proximal to the pylorus. After checking for leakage with methylene blue, tissue adhesive (Fibrin glue tissel, Ifabond glue) was applied to the stapler line. Following removal of the gastrectomy specimen from the abdomen, a Jackson-Pratt drain was placed along the sleeve stapler line.

A postoperative diet protocol was applied. If no leakage was detected, an oral fluid diet was started. Patients were discharged on the postoperative 5th day after eating pureed food.

Statistical analysis

The NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 (Kaysville, UT, USA) program was used for statistical analysis. Two groups of descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency, percent, minimum, maximum) were used. Mann-Whitney U-test was performed for comparison of two groups without normal distribution. The Friedman test was performed to compare followups of non-normal distribution parameters. Diagnostic screening tests (sensitivity, specificity, PKD, NKD) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis were used to determine the cutoff for the parameters. Values of p<0.001 and p<0.05 levels were considered significant.

Results

In the comparison of preoperative WBC, CRP, NLR and presepsin values, no statistically significant differences were found between the patient and control groups. The mean plasma presepsin value of the control group was determined to be 273 pg/mL (Table 1).

P LEUC, P CRP, P PRE and P NLR values in groups.

| Preop | Total (n=340) | Patient group (n=300) | Control group (n=40) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P LEUC (×103/μL) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 8.89±1.9 | 8.97±1.8 | 8.36±2.3 | 0.286c |

| Min–max (median) | 3.3–12.7 (8.9) | 5.86–12.7 (9.06) | 3.2–12.7 (8.2) | |

| P CRP (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 0.96±0.7 | 0.98±0.7 | 0.83±0.56 | 0.100c |

| Min–max (median) | 0.09–9.6 (0.84) | 0.11–9.6 (0.85) | 0.09–2.29 (0.68) | |

| P PRE (pg/mL) | ||||

| Mean±SD | 280.9±68.5 | 282.9±66.9 | 265.3±78.8 | 0.131c |

| Min–max (median) | 96–402 (271) | 118–402 (268) | 96–385 (273) | |

| P NLR | ||||

| Mean±SD | 1.76±0.6 | 1.67±0.52 | 1.96±1.27 | 0.945c |

| Min–max (median) | 0.06–8.7 (1.72) | 0.06–3.15 (1.72) | 0.57–8.7 (1.7) | |

c, Mann-Whitney U-test; Preop, preoperative; P LEUC, preoperative leukocyte; P CRP, preoperative C-reactive protein; P PRE, preoperative presepsin; P NLR, preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

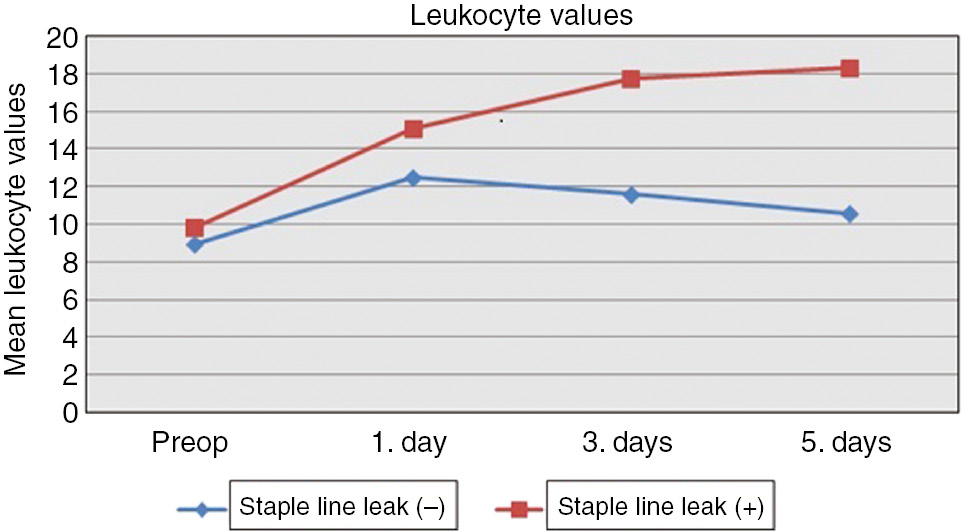

No statistically significant difference was determined between the patients with and without leakage in respect of preoperative leukocyte counts (p>0.05). WBC values on postoperative days 1, 3 and 5 were higher in cases with leakage (p=0.035, p=0.001, p=0.001) respectively. There is significant difference between leukocyte preop, day 1, day 3, day 5 (p1<0.001). The mean of day 1 is higher in staple line leak (−). The mean of day 5 is higher in staple line leak (+) (Table 2, Figure 1).

Evaluation of leukocyte values according to the staple line leak.

| Leukocyte (×103/μL) (n=300) | Staple line leak (−) (n=291) | Staple line leak (+) (n=9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | |||

| Mean±SD | 8.94±1.85 | 9.81±1.35 | 0.158 |

| Min–max (median) | 5.86–12.7 (8.9) | 7.18–11.9 (9.8) | |

| Day 1 | |||

| Mean±SD | 12.5±3.3 | 15.07±4.62 | 0.035a |

| Min–max (median) | 1.3–22.8 (12.5) | 8.7–25.6 (14.4) | |

| Day 3 | |||

| Mean±SD | 11.59±2.04 | 17.70±6.80 | 0.001b |

| Min–max (median) | 6.2–14.7 (11.6) | 9.3–33.47 (17.8) | |

| Day 5 | |||

| Mean±SD | 10.59±2.11 | 18.29±4.79 | 0.001b |

| Min–max (median) | 6.67–14.5 (10.1) | 13.1–25.7 (18.4) | |

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Bold italic ap<0.05 and bp<0.01 values were considered significant. The levels were shown as respectively ‘a’ and ‘b’.

Preop, Preoperative.

Mean leukocyte values of patient groups.

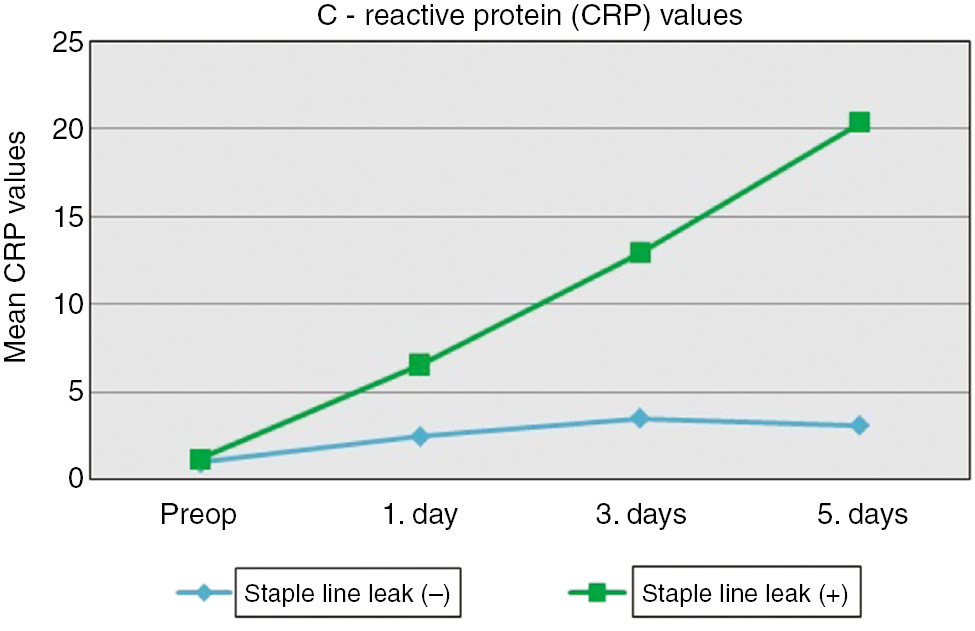

No statistically significant difference was determined in respect of preoperative CRP values (p>0.05). CRP values on postoperative days 1, 3 and 5 were higher in cases with leakage (p=0.001, p=0.001, p=0.001, respectively). There is significant difference between CRP preop, day 1, day 3, day 5 (p1<0.001). The mean of day 3 is higher in staple line leak (−). The mean of day 5 is higher in staple line leak (+) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Evaluation of C-reactive protein values according to the staple line leak.

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) (n=300) | Staple line leak (−) (n=291) | Staple line leak (+) (n=9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.94±0.57 | 1.14±0.73 | 0.207 |

| Min–max (median) | 0.11–2.84 (0.84) | 0.33–2.62 (0.96) | |

| Day 1 | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.44±1.03 | 6.51±3.11 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 0.46–5 (2.4) | 2.7–12.27 (6.54) | |

| Day 3 | |||

| Mean±SD | 3.49±1.76 | 12.87±8.6 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 1.02–13.2 (3.3) | 6.2–31.1 (9.6) | |

| Day 5 | |||

| Mean±SD | 3.06±0.96 | 20.3±13.57 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 1.1–5.67 (2.89) | 7.63–41.3 (11.32) | |

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Bold italic ap<0.01 value was considered significant. The level was shown as ‘a’.

Preop, Preoperative.

Mean C-reactive protein values of patient groups.

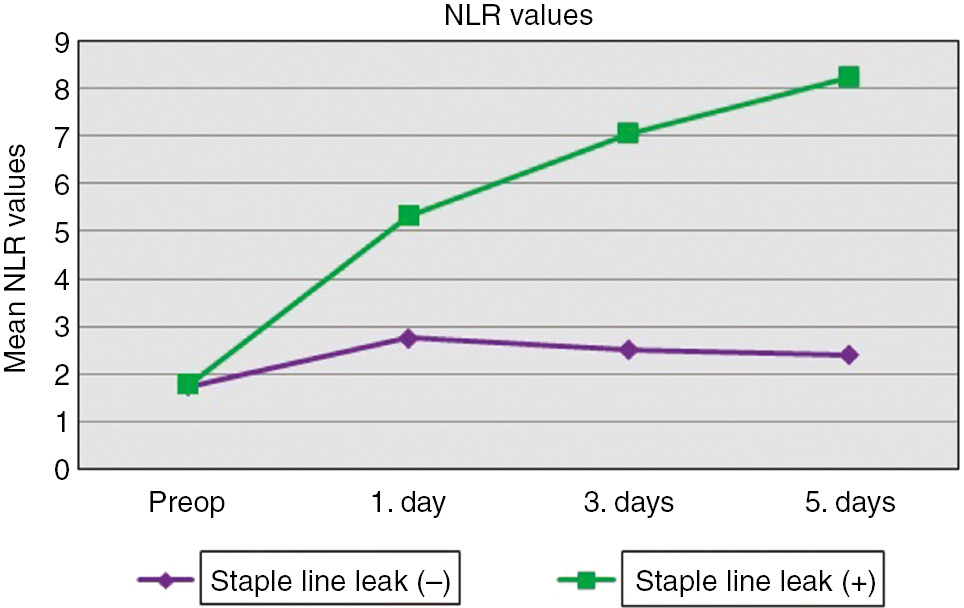

No statistically significant difference was determined in respect of preoperative NLR values (p>0.05). NLR values on postoperative days 1, 3 and 5 were higher in cases with leakage (p=0.001, p=0.001, p=0.001), respectively. There is significant difference between NLR preop, day 1, day 3, day 5 (p1<0.001). The mean of day 3 is higher in staple line leak (−). The mean of day 5 is higher in staple line leak (+) (Table 4, Figure 3).

Evaluation of reactive NLR values according to the staple line leak.

| NLR (n=300) | Staple line leak (−) (n=291) | Staple line leak (+) (n=9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.74±0.51 | 1.78±0.62 | 0.761 |

| Min–max (median) | 0.06–2.92 (1.7) | 1.14–3.15 (1.5) | |

| Day 1 | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.78±0.62 | 5.30±2.56 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 1.14–3.15 (1.56) | 2.3–11.3 (5.2) | |

| Day 3 | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.77±0.78 | 7.05±1.97 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 1.23–4.9 (2.7) | 3.3–9.6 (7.2) | |

| Day 5 | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.49±0.83 | 8.22±5.13 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 0.9–4.3 (2.4) | 5.16–20.8 (6.1) | |

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Bold italic ap<0.01 value was considered significant. The level was shown as ‘a’.

Preop, Preoperative; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio.

Mean neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio of patient groups.

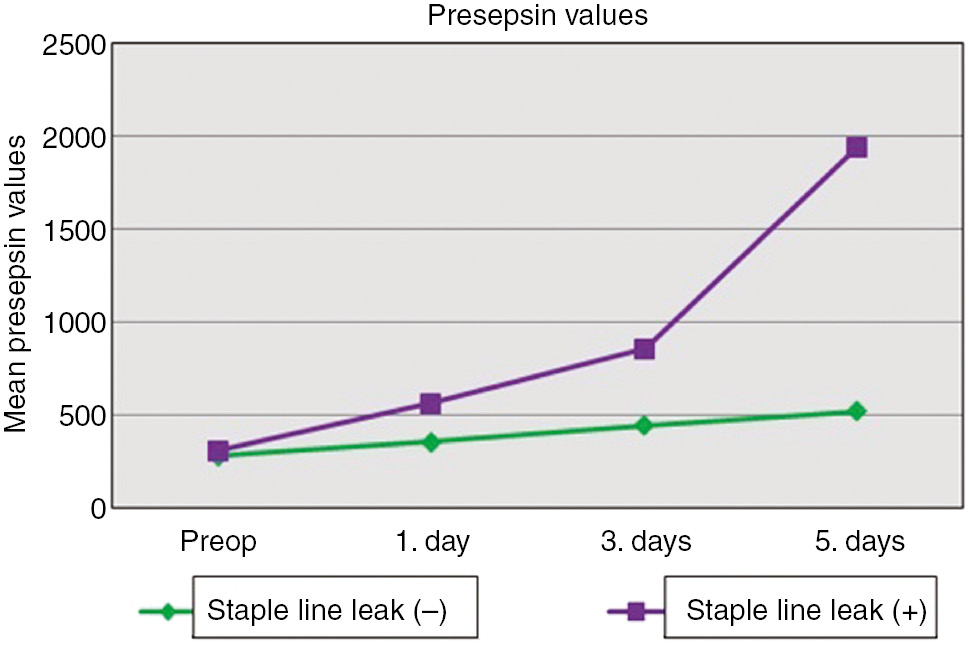

No statistically significant difference was determined in respect of preoperative presepsin values (p>0.05). Presepsin values on postoperative days 1, 3 and 5 were higher in cases with leakage (p=0.001, p=0.001, p=0.001, respectively). There is significant difference between preop, day 1, day 3, day 5 (p1<0.001). The mean of day 5 is higher in staple line leak (−) and staple line leak (+) (Table 5, Figure 4).

Evaluation of presepsin values according to the staple line leak.

| Presepsin (pg/mL) (n=300) | Staple line leak (−) (n=291) | Staple line leak (+) (n=9) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | |||

| Mean±SD | 282.1±67.4 | 310.22±38.97 | 0.174 |

| Min–max (median) | 118–402 (267) | 263–382 (311) | |

| Day 1 | |||

| Mean±SD | 356.1±57 | 563.11±86.13 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 246–471 (360) | 461–716 (563) | |

| Day 3 | |||

| Mean±SD | 448.1±54.5 | 857.67±122.2 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 336–563 (450) | 645–1063 (854) | |

| Day 5 | |||

| Mean±SD | 524.1±64.4 | 1938.67±904.82 | 0.001a |

| Min–max (median) | 369–649 (530) | 856–3478 (1728) | |

Mann-Whitney U-test.

Bold italic ap<0.01 value was considered significant. The level was shown as ‘a’.

Preop, Preoperative.

Mean presepsin values of patient groups.

Cut-off values of WBC, CRP, NLR and presepsin were determined as 13.2×103/μL, 3.4 mg/dL, 4.3 and 461 pg/mL, respectively.

Sensitivity and specificity values were determined as 77.78% and 63.57%, respectively for WBC, 88.89% and 87.97% for CRP, 77.78% and 97.94% for NLR, and 100% and 96.91% for presepsin. PPV, NPV and the area below the ROC curve of WBC were calculated as 6.2, 98.9 and 71%, respectively, of CRP at 18.6, 99.6 and 94%, of NLR at 53.8, 99.3 and 88%, and of presepsin at 50, 100 and 99% (Table 6).

Screening test and ROC Curve results in detecting staple line leak.

| Day 1 values | Diagnostic scan | ROC curve | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Area | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| LEUC | ≥13.17 (×103/μL) | 77.78 | 63.57 | 6.2 | 98.9 | 0.715 | 0.576–0.818 | 0.010a |

| CRP | ≥3.39 (mg/dL) | 88.89 | 87.97 | 18.6 | 99.6 | 0.944 | 0.912–0.968 | 0.001b |

| PRE | ≥460.69 (pg/mL) | 100 | 96.91 | 50.0 | 100 | 0.994 | 0.978–1.000 | 0.001b |

| NLR | ≥4.29 | 77.78 | 97.94 | 53.8 | 99.3 | 0.883 | 0.841–0.917 | 0.001b |

ap<0.05, bp<0.01.

Bold text indicates significant values, LEUC, Leukocyte; CRP, C-reactive protein; PRE, presepsin; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The comparisons of postoperative day 1 values of the patients with staple line leakage are summarized in Table 7. The presepsin value was more significant than the other laboratory parameters (Leuc, p<0.05; CRP, NLR). The areas under the ROC curve were PRE>CRP>NLR>LEUC. There was also only significant difference between the LEU and PRE according to AUC data (p<0.008 Bonferroni correction).

Comparison of ROC curves.

| CRP vs. NLR | CRP vs. LEU | CRP vs. PRE | NLR vs. LEU | NLR vs. PRE | LEU vs. PRE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference between areas | 0.052 | 0.224 | 0.064 | 0.171 | 0.117 | 0.289 |

| p-Value | 0.537 | 0.016 | 0.119 | 0.135 | 0.149 | 0.002a |

ap<0.008 (Bonferroni correction).

Bold text indicates signifcant value, LEU, Leukocyte; CRP, C-reactive protein; PRE, presepsin; NLR, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Stapler line leakage developed in a total of 9 (3%) patients (6 females, 3 males; median age: 40 years (range: 19–56 years); mean BMI: 43.2). These patients were treated with endoscopic stenting and percutaneous drainage. The intra-abdominal drainage status was seropurulent in 5 of 9 patients and the others were serous. Other than intra-abdominal abscess, no major complications developed in any patients.

Discussion

Early detection of leakage is the most important criterion for decreasing the mortality rate (1–10%), which may occur as a result of abscess, peritonitis, sepsis, or multi organ failure after stapler line leakage [25], [26]. A delayed diagnosis may result in prolonged hospital stay, re-hospitalization and increased treatment costs [27]. In all cases, the early detection of postoperative leaks is of critical importance [28]. Tachycardia is the most important early clinical sign of leakage. It was observed that tachycardia and presepsin levels were correlated (data not shown). Physical examination (tachycardia etc.), inflammatory parameters and computed tomography are used to detect anastomotic leaks [26], [28], [29]. CRP, which is synthesized from the liver and has a half-life of 19 h, is an inflammatory marker commonly used in the diagnosis of intra-abdominal infections. In the postoperative period, CRP has 74% sensitivity and 75% specificity in the detection of anastomotic leakage [30]. In the current study, a CRP value >3.4 mg/dL on the first day was found to be significant.

The neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a parameter that is easily calculated by the ratio of neutrophil and lymphocyte numbers determined in the whole blood count. This is accepted as an inflammation marker, and the efficacy has been evaluated in various diseases in recent studies [31], [32]. There are studies advocating that NLR is a useful marker for determining the degree of inflammation (non-complicated/complicated appendicitis) in acute appendicitis, which is the most common cause of emergency surgical pathology [33]. These results support the hypothesis of the utility of the NLR in the identification and follow-up of an acutely deteriorating table. In the current study, NLR≥4.3 on postoperative day 1 was found to be significant.

Sargentini et al. showed that in the diagnosis of sepsis, presepsin, which has moderate diagnostic value alone, has increased diagnostic value and may be used as a sepsis biomarker when used as an acute phase reactant with other inflammatory parameters [34]. In a meta-analysis, presepsin, as an effective biomarker in the diagnosis of sepsis, was reported to have 83% specificity and 78% sensitivity [35]. In the current prospective study of presepsin in acute inflammatory pathologies, the median plasma level of presepsin in the control group was found to be 273 pg/mL, which was similar to the normal value of presepsin as described previously.

Patients with stapler fistula had similar statistically significantly elevated levels of presepsin, CRP and NLR due to intra-abdominal infection on the first day postoperatively, which predicted complications and these values were in accordance with the levels on the postoperative 3rd and 5th days.

According to comparisons of the days by each group in stapler line leak (−) group, mean LEU levels were reached its maximum level at day 1 and then it was shown tendency to decreasing. Also maximum mean CRP and NLR levels were found at 3rd day. This findings may be misleading to determining the leaks, furthermore ROC analysis have shown that the presepsin is more sensitive and effective marker.

As morbidly obese patients are difficult to examine, these parameters play an even more important role in the detection of intra-abdominal infections.

The postoperative day 1 presepsin value was determined to be more significant than the other laboratory parameters (Leu, CRP, NLR), according to the ROC analysis of the patients with staple line leak, indicating that presepsin may be more effective in early-term clinical practice.

Due to the diversity of intra-abdominal flora, early intervention on day 1 for leakage after obesity surgery has been shown to reduce the risk of mortality [36], whereas an average of 2.5 days delay in intervention increases mortality by 24–39% [37].

One of the negative aspects of the study is the high rate of leakage. This is because some of the operations were performed during the training of the assistants under the supervision of experienced bariatric surgeons [38], [39].

The results of this study indicated that elevated levels of presepsin can be more useful in the detection and follow-up of leaks following LSG compared to other inflammatory parameters such as CRP and NLR especially on postoperative days 1 and 3. The increase in presepsin level, especially on the first postoperative day, is important in the detection of possible postoperative complications which are not seen clinically. Further research will provide a better understanding of the relationship between presepsin and complications in morbid obesity surgery.

Conflict of interest statement: All authors declared that there are no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

1. Gagner M, Rogula T. Laparoscopic reoperative sleeve gastrectomy for poor weight loss after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2003;13:649–54.10.1381/096089203322190907Suche in Google Scholar

2. Jurowich C, Thalheimer A, Seyfried F, Fein M, Bender G, Germer CT, et al. Gastric leakage after sleeve gastrectomyclinical presentation and therapeutic options. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011;396:981–7.10.1007/s00423-011-0800-0Suche in Google Scholar

3. Burgos AM, Braghetto I, Csendes A, Maluenda F, Korn O, Yarmuch J, et al. Gastric leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Obes Surg 2009;19:1672–7.10.1007/s11695-009-9884-9Suche in Google Scholar

4. Csendes A, Braghetto I, León P, Burgos AM. Management of leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in patients with obesity. J Gastrointest Surg 2010;14:1343–8.10.1007/s11605-010-1249-0Suche in Google Scholar

5. Tan JT, Kariyawasam S, Wijeratne T, Chandraratna HS. Diagnosis and management of gastric leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2010;20:403–9.10.1007/s11695-009-0020-7Suche in Google Scholar

6. Clinical Issues Committee of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated position statement on sleeve gastrectomy as a bariatric procedure. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:1–5.10.1016/j.soard.2009.11.004Suche in Google Scholar

7. Alves A, Panis Y, Pocard M, Regimbeau JM, Valleur P. Management of anastomotic leakage after nondiverte large bowel resection. J Am Coll Surg 1999;189:554–9.10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00207-0Suche in Google Scholar

8. Platell C, Barwood N, Dorfmann G, Makin G. The incidence of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:71–9.10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01002.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. de Aretxabala X, Leon J, Wiedmaier G, Turu I, Ovalle C, Maluenda F, et al. Gastric leak after sleeve gastrectomy: analysis of its management. Obes Surg 2011;21:1232–7.10.1007/s11695-011-0382-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Casella G, Soricelli E, Rizzello M, Trentino P, Fiocca F, Fantini A, et al. Nonsurgical treatment of staple line leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 2009;19:821–6.10.1007/s11695-009-9840-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Boccola MA, Buettner PG, Rozen WM, Siu SK, Stevenson AR, Stitz R, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a single institution analysis of 1576 patients. World J Surg 2011;35:186–95.10.1007/s00268-010-0831-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Lipska MA, Bissett IP, Parry BR, Merrie AE. Anastomotic leakage after lower gastrointestinal anastomosis: men are at a higher risk. ANZ J Surg 2006;76:579–85.10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03780.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Stamou KM, Menenakos E, Dardamanis D, Arabatzi C, Alevizos L, Albanopoulos K, et al. Prospective comparative study of the efficacy of staple-line reinforcement in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 2011;25:3526–30.10.1007/s00464-011-1752-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Sakran N, Goitein D, Raziel A, Keidar A, Beglaibter N, Grinbaum R, et al. Gastric leaks after sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter experience with 2,834 patients. Surg Endosc 2013;27:240–5.10.1007/s00464-012-2426-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Yaegashi Y, Shirakawa K, Sato N, Suzuki Y, Kojika M, Imai S, et al. Evaluation of a newly identified soluble CD14 subtype as a marker for sepsis. J Infect Chemother 2005;11:234–8.10.1007/s10156-005-0400-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Chiesa C, Natale F, Pascone R, Osborn JF, Pacifico L, Bonci E, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin: reference intervals for preterm and term newborns during the early neonatal period. Clin Chim Acta 2011;412:1053–9.10.1016/j.cca.2011.02.020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Mussap M, Noto A, Cibecchini F, Fanos V. The importance of biomarkers in neonatology. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;18:56–64.10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Meem M, Modak JK, Mortuza R, Morshed M, Islam MS, Saha SK. Biomarkers for diagnosis of neonatal infections: a systematic analysis of their potential as a point-of-care diagnostics. J Glob Health 2011;1:201–9.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Palmiere C, Mussap M, Bardy D, Cibecchini F, Mangin P. Diagnostic value of soluble CD14 subtype (sCD14-ST) presepsin for the postmortem diagnosis of sepsis-related fatalities. Int J Legal Med 2013;127:799–808.10.1007/s00414-012-0804-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Liu B, Chen YX, Yin Q, Zhao YZ, Li CS. Diagnostic value and prognostic evaluation of presepsin for sepsis in an emergency department. Crit Care 2013;17:R244.10.1186/cc13070Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Ulla M, Pizzolato E, Lucchiari M, Loiacono M, Soardo F, Forno D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of presepsin in the management of sepsis in the emergency department: a multicenter prospective study. Crit Care 2013;17:R168.10.1186/cc12847Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Hyman NH. Managing anastomotic leaks from intestinal anastomoses. Surgeon 2009;7:31–5.10.1016/S1479-666X(09)80064-4Suche in Google Scholar

23. Murrell ZA, Stamos MJ. Reoperation for anastomotic failure. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2006;19:213–6.10.1055/s-2006-956442Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Spanuth E, Carpio R, Thomae R. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of PATHFAST presepsin in patients with SIRS and early sepsis. Crit Care 2015;19:63.10.1186/cc14143Suche in Google Scholar

25. Lalor PF, Olga Tucker N, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:33–8.10.1016/j.soard.2007.08.015Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Gonzalez R, Sarr GM, Smith CD, Baghai M, Kendrick M, Szomstein S, et al. Diagnosis and contemporary management of anastomotic leaks after gastric bypass for obesity. J Am Coll Surg 2007;204:47–55.10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.09.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Vix M, Diana M, Marx L, Callari C, Wu HS, Perretta S, et al. Management of staple line leaks after sleeve gastrectomy in a consecutive series of 378 patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2015;25:89–93.10.1097/SLE.0000000000000026Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Carucci LR, Turner MA, Conklin RC, DeMaria EJ, Kellum JM, Sugerman HJ. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: evaluation of postoperative extraluminal leaks with upper gastrointestinal series. Radiology 2006;238:1.10.1148/radiol.2381041557Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Walsh C, Karmali S. Endoscopic management of bariatric complications: a review and update. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015;7:518–23.10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.518Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Platt JJ, Ramanathan ML, Crosbie RA, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Horgan PG, et al. C-reactive protein as a predictor of postoperative infective complications after curative resection in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:4168–77.10.1245/s10434-012-2498-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Prajapati PJ, Sahoo S, Nikam T, Shah KH, Maheriya B, Parmar M. Association of high density lipoprotein with platelet to lymphocyte and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios in coronary artery disease patients. J Lipids 2014;2014:686791.10.1155/2014/686791Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Chen ZY, Raghav K, Lieu CH, Jiang ZQ, Eng C, Vauthey JN, et al. Cytokine profile and prognostic significance of high neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2015;112:1088–97.10.1038/bjc.2015.61Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Shimizu T, Ishizuka M, Kubota K. A lower neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is closely associated with catarrhal appendicitis versus severe appendicitis. Surg Today 2016;46:84–9.10.1007/s00595-015-1125-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Sargentini V, Ceccarelli G, D’Alessandro M, Collepardo D, Morelli A, D’Egidio A, et al. Presepsin as a potential marker for bacterial infection relapse in critical care patients, A preliminary study. Clin Chem Lab Med CCLM/FESCC 2015;53:567–73.10.1515/cclm-2014-0119Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Zhang J, Hu ZD, Song J, Shao J. Diagnostic value of presepsin for sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e2158.10.1097/MD.0000000000002158Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Alves A, Panis Y, Trancart D, Regimbeau JM, Pocard M, Valleur P. Factors associated with clinically significant anastomotic leakage after large bowel resection: multivariate analysis of 707 patients. World J Surg 2002;26:499–502.10.1007/s00268-001-0256-4Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. den Dulk M, Noter SL, Hendriks ER, Brouwers MA, van der Vlies CH, Oostenbroek RJ, et al. Improved diagnosis and treatment of anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009;35:420–6.10.1016/j.ejso.2008.04.009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, Brandy R, Vroegop T, Serveld M. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg 2004;14:1290–8.10.1381/0960892042583888Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Corona M, Zini C, Allegritti M, Boatta E, Lucatelli P, Cannavale A, et al. Minimally invasive treatment of gastric leak after sleeve gastrectomy Trattamento minimamente invasivo delle fistole gastriche dopo sleeve gastrectomy. Radiol Med 2013;118:962–70.10.1007/s11547-013-0938-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery