Abstract

Background

Cytoplasmic sialidase (NEU2) plays an active role in removing sialic acids from oligosaccharides, glycopeptides, and gangliosides in mammalian cells. NEU2 is involved in various cellular events, including cancer metabolism, neuronal and myoblast differentiation, proliferation, and hypertrophy. However, NEU2-interacting protein(s) within the cell have not been identified yet.

Objective

The aim of this study is to investigate NEU2 interacting proteins using two-step affinity purification (TAP) strategy combined with mass spectrometry analysis.

Methods

In this study, NEU2 gene was cloned into the pCTAP expression vector and transiently transfected to COS-7 cells by using PEI. The most efficient expression time of NEU2- tag protein was determined by real-time PCR and Western blot analysis. NEU2-interacting protein(s) were investigated by using TAP strategy combined with two different mass spectrometry experiment; LC-MS/MS and MALDI TOF/TOF.

Results

Here, mass spectrometry analysis showed four proteins; α-actin, β-actin, calmodulin and histone H1.2 proteins are associated with NEU2. The interactions between NEU2 and actin filaments were verified by Western blot analysis and immunofluorescence analysis.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that association of NEU2 with actin filaments and other protein(s) could be important for understanding the biological role of NEU2 in mammalian cells.

Öz

Geçmiş

Sitoplasmik sialidaz (NEU2) memeli hücrelerinde oligosakkaritler, glikopeptidler ve gangliosidlerden sialik asitin uzaklaştırılmasında aktif bir rol oynamaktadır. NEU2, kanser metabolizması, nöron farklılaşması ve miyoblast çoğalması, farklılaşması ve hipertrofisini içeren farklı hücresel olaylarda görev yapmaktadır. Bununla birlikte, hücre içerisinde NEU2 ile ilişkili protein(ler) henüz tanımlanmamıştır.

Amaç

Bu çalışmanın amacı iki-basamak afinite saflaştırma (TAP) stratejisi ile birlikte kütle spektrometri analizini kullanarak NEU2 ile etkileşen proteinleri araştırmaktır.

Malzemeler ve Metodlar

Bu çalışmada, NEU2 geni pCTAP ekspresyon vektörüne klonlandı ve PEI kullanılarak geçici olarak COS-7 hücrelerine transfekte edildi. Rekombinant NEU2 –tag proteininin en etkili ifade süresi, gerçek zamanlı PCR ve Western blot analizi ile belirlendi. NEU2 ile etkileşen protein(ler), TAP stratejisi ve iki farklı kütle spektrometresi deneyi kombine ederek araştırıldı; LC-MS/MS ve MALDI TOF/TOF.

Bulgular

Burada, kütle spektrometresi analizine göre NEU2, α-aktin, β-aktin, kalmodulin ve histon H1.2’yi etkileşime girebilmektedir. NEU2 ve aktin filamentleri arasındaki etkileşim, Western blot ve immünofloresan analizi ile doğrulanmıştır.

Sonuç

Çalışmamız, NEU2’nin aktin filamentleri ve diğer protein (ler) ile etkileşmesinin, memeli hücrelerinde NEU2’ nin biyolojik rolünü anlamak için önemli olabileceğini düşündürmektedir.

Introduction

Sialidases (EC 3.2.1.18, also called neuraminidases) belong to the family of exoglycosidases and are responsible for the hydrolytic cleavage of sialic acid residues from glycoconjugates such as glycoproteins and glycolipids [1], [[2]. They are widely distributed in nature, from viruses and microorganisms to avian and mammalian species 2]. In mammals, four different sialidases have been purified, cloned, and characterized. These are classified based on their subcellular localization and enzymatic properties. NEU1, NEU2, and NEU3 are predominantly localized in the lysosomes, cytosol, and plasma membranes, respectively, whereas NEU4 is found in the lysosomes, mitochondria, and intracellular membranes [[3], [4], [5]. The expression levels of sialidases in cells and tissues, as well as their substrate specificities and optimum pH values, are variable. NEU2 is detected in various human tissues, being relatively high in skin (https://www.proteinatlas.org/search/NEU2) and at low levels in placenta, testis, lung, pancreas and ovary 6]. Furthermore, NEU2 transcript was also detected at very low levels in NT2D1 embryonic carcinoma cell line and human fetal liver [7]. The absence of ESTs in dbEST also confirms the level of human NEU2 is the least transcript among the different members of gene family. Sialidases are involved in various cellular events, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, glycolipid and glycoproteins metabolism, clearance of plasma proteins, cell adhesion control, receptor modification, immunocyte function, and modeling of myelin [1], [2].

The cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2 plays an important role in cancer progression. The overexpression of NEU2 in leukemic K562 cells, in which endogenous NEU2 was not detectable, resulted in the suppression of cell proliferation and acceleration of apoptosis by lowering the expression levels of the anti-apoptotic factors Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 (30% and 80%, respectively) [8].

Under normal conditions, cytoplasmic sialidase expression is very low in PC12 cells, which are a favored model for studying neuronal differentiation. However, the NEU2 expression is significantly elevated under differentiating and proliferating conditions, which indicates a potential role of NEU2 in neuronal differentiation [9].

NEU2 also plays an important role in myoblast differentiation by desialylation of glycoconjugates. The function of NEU2 in myoblast differentiation has been demonstrated in rat L6 myogenic cells and mouse C2C12 myoblast cells [10], [[11]. A gradually increasing level of NEU2 expression and enzymatic activity was reported for in post-mitotic myoblasts, with the highest level observed for fully matured hypertrophic myotubes 12].

Tandem affinity purification (TAP) allows the determination of the proteins involved in protein complexes and was originally developed by Rigaut et al. for use in yeast cells [13]. Several dual-affinity tags have been developed to identify associated proteins in mammalian cells [14]. The identification of partners that interact with a particular target protein can be used to define protein-protein interactions and proteins with unknown functions. For example, various protein complexes have been successfully identified in mammalian cell lines using the InterPlay TAP system [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. As the possible substrate(s) and product(s) of NEU2 in myofibers, cancer metabolism, and neural differentiation remain uncertain 1]. In this study, we focused on the identification of proteins that might interact with NEU2. In this study, NEU2-interacting proteins in COS-7 cells were identified using the InterPlay TAP system followed by mass spectrometric analysis to shed light on the possible biological function of NEU2 in cellular metabolism [8], neuronal [9] and myoblast differentiation [11], proliferation and hypertrophy [20]. We identified α-actin, β-actin, histone H1.2 and calmodulin as potential NEU2-associated proteins.

Methods

DNA expression constructs

Human cytosolic sialidase NEU2 was obtained from peripheral blood cell donated by Dr. Volkan Seyrantepe. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from white blood cells using TRIzol reagent (Geneaid). cDNA (50 ng/μL) was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit according to manufacturer’s recommendations (Applied Biosystems), NEU2 cDNA was amplified with a primer pair of 5′-AAAGGATCCATGGCGTCCCTTCCTGTCCTG-3′ and 5′-AAATTCGAACTGAGGCA GGTACTCAGCTGGG-3′. The resulting PCR product was digested with HindIII and BamHI and cloned into the pCTAP vector (Stratagene) to generate the pCTAP-NEU2 vector. Construction of the expression vector was confirmed by restriction pattern analysis and sequencing (data not shown).

Cell lines and transfection

COS-7 cells were maintained at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with L-glutamine (Lonza), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL Streptomycin (Gibco), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. COS-7 cells were transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI; Sigma) at a 3:1 transfection reagent to DNA ratio of 3:1 (3 μL 1 μg/mL PEI:3 μg DNA). COS-7 cells were transfected with either an empty expression plasmid (mock) and pCTAP-NEU2 plasmid for 24, 36, 48 and 72 h.

Real-time PCR

The relative expression of NEU2-tag mRNA was determined using LightCycler-480-SYBR-Green-I-Master Mix (Roche) with the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene as an internal control. Total RNA was extracted from mock, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h pCTAP-NEU2 post-transfection COS-7 cells (n=3) using TRIzol reagent (Geneaid). cDNA (50 ng/μL) was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), and 75 ng of the cDNA was used in the 20 μL reaction mixture, which included 40 pmol of each primer and 1× Roche LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix. The PCR conditions were as follows: one cycle of 10 min at 95°C; followed by 45 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 15 s at 61°C, and 22 s at 72°C, and reading was performed after each cycle. At the end, one cycle of 30 s at 95°C, and 10 s at 60°C was performed. The following primer pairs were used for genes of interest: NEU2; NEU2F (5′-CAAGCAAGAAGGATGAGCACG-3′), NEU2R (5′-TGCAAAGGTGGACCACTCC-3′), GAPDH; GAPDHF (5′-CCCCTTCATTGACCTCAACTAC-3′), and GAPDHR (5′-ATGCATTGC TGACAATCTTGAG-3′).

Cell lysis and Western blot analysis

Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were rinsed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed using 0.5 mL of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) per 2×107 cells. Prior to use, 0.1% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma) and 100 mM of phenylmethlysulfonyl (PMSF) (Sigma) were added to the required volume of lysis buffer.

The protein concentrations were estimated using the Bradford colorimetric method with bovine serum albumin as standard. Twenty microgram protein samples were run on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were then blocked in 1×PBST (1×PBS, 0.05% Tween-20) containing 5% non-fat milk for 1 h. The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-NEU2 (1:2000, Novus Biologicals, NBP2-00783), anti-β-actin (1:5000, Santa Cruz), anti-calmodulin binding protein epitope tag primary antibody (1:5000, Merck Millipore), and γ-tubulin primary antibody (1:1000, Santa Cruz). The incubation was performed for 1 h at room temperature in 1×PBST containing 0.5% non-fat milk. The blots were then washed five times in 1×PBST for 10 min. The secondary antibody used was: rabbit polyclonal to mouse IgG H and L (1:5000, Santa Cruz). The incubation was performed for 1 h at room temperature in 1×PBST containing 0.05% non-fat milk and was followed by washing five times with 1×PBST for 10 min. SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific) was used to visualize the blots.

Enzyme activity assay

Sialidase activity in the 48-h post-transfected COS-7 cells was assayed using 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt hydrate (4-MU-NeuAc) (Sigma 69587). Mock and pCTAP-NEU2 transfected COS-7 cells were homogenized in 0.4 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.3) by sonication at 60 V for 10 s. The homogenate, including 80 μg protein, was then incubated in sodium acetate buffer containing 0.5 mM substrate for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2 M glycine buffer (pH 10.8). Measurements were performed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) at an excitation wavelength of 365 nm and an emission wavelength of 445 nm. The protein concentrations in the samples were determined with the Bradford reagent (Sigma) and used to calculate specific enzyme activities.

Tandem affinity purification

Ten 150-mm plates of pCTAP-NEU2 transfected COS-7 cells were obtained 48-h post-transfection. The cells were then washed twice with cold PBS and purified using the InterPlay Mammalian TAP system (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The whole cell lysate was first bound to streptavidin beads and then washed twice with the streptavidin binding buffer to remove unbound proteins, and bound proteins were subsequently eluted with the streptavidin elution buffer which contains 2 mM biotin. The eluate was subsequently bound to Ca2+ activated calmodulin beads and calmodulin binding buffer was used to remove unbound proteins. The bound proteins were eluted with the calmodulin elution buffer, which contains the chelating agent ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) at 5 mM concentration. The final eluate containing the protein of interest (NEU2) and the proteins that associate with it, was analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

LC-MS/MS analysis

The proteins purified by the two-step affinity purification strategy were concentrated by dialysis (3–7 kDa cutoff). Proteolytical digestion of proteins was carried out by the filter-aided sample preparation protocol (FASP) [21]. In this protocol, 50 μg of protein was washed with 6 M urea (Sigma-Aldrich) and free thiols were then alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) (Sigma-Aldrich) in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, the samples were washed with 6 M urea and 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) (Fluka) and then trypsinized at 37°C overnight (1:100 trypsin to protein ratio). The samples were prepared at a peptide concentration of 100 ng/mL.

The LC-MS/MS analysis was performed following a previously published protocol [22]. A sample volume of 2 μL (containing 500 ng of the tryptic peptide mixture) was loaded onto the LC-ESI-qTOF system (nanoACQUITY ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) and SYNAPT high-definition mass spectrometer with NanoLockSpray ion source, Waters). The MS instrument was used in the positive ion and data-independent acquisition mode (MSE). MS and MS/MS spectra were acquired at 1.5 s intervals with 6 V low-energy and 15–40 V high-energy collisions over a scan range of m/z 50–1600. The m/z data and product ion formation were used to determine the amino acid sequences. The acquired MS/MS spectra were transformed in the Micromass (pkl) file format and used for peptides identification with the online version of Mascot.

Spectral data were obtained in the pkl file format. The MS/MS spectra were analyzed against the SwissProt database using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science Ltd., London, UK) (http://www.matrixscience.com/). The Mascot search parameters were set as follows: taxonomy human; “trypsin” as enzyme allowing up to one missed cleavages; cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification; N-terminal acetylation, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, and oxidation of methionine as variable modifications; 0.6 Da fragment mass tolerance; and 0.6 Da peptide mass tolerance. Prior to protein identification, sequences corresponding to tryptic contaminants or keratin contaminants were filtered.

MALDI-TOF-TOF analysis

The proteins purified by the two-step affinity purification strategy (72 μg) were diluted in rehydration buffer (8 M urea, 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate hydrate (CHAPS), 4 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)) applied onto immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (pH 3–10). Protein transfer into the strips was performed actively at 50 V for 15 h using an isoelectric focusing system (Bio-Rad Protean IEF Cell) with subsequent isoelectric focusing at 20°C. The strips were incubated in equilibration buffer (6 M urea, 0.375 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 2% DTT) for 15 min and then applied to SDS polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis was carried out at 220 V for 6 h (Bio-Rad Protean II xi cell). After staining the gels with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, two detected spots were subjected to MALDI TOF/TOF analysis (Bruker Autoflex III Smartbeam, Bremen, Germany).

For in-gel tryptic digestion, the spots were washed in 50% (v/v) methanol and 5% (v/v) acetic acid overnight at room temperature. After dehydration using acetonitrile, the spots were digested overnight with 20 ng/μL modified trypsin in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer at 37°C. The supernatant of the tryptic digest and the peptides remaining in the gel were subjected to two rounds of extraction in 50% (v/v) acetonitrile and 5% (v/v) formic acid. The volume of the extract was reduced in a vacuum centrifuge and 1% acetic acid was added. Samples were desalted using C18 ZipTips (Millipore) and eluted with 50% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA, 5 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 20% methanol in acetone and of 2.5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB, 20 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 20% acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA. The protein samples (1 μL) were mixed with a CHCA/DHB (1:2, v/v) matrix mixture (5 μL) by vortexing and then deposited onto the target. The spectra were processed and analyzed using Autoflex III Smartbeam (Bruker) which uses internal Mascot software (Matrix Science, London, UK) for searching the MS/MS data.

The MS/MS ions were analyzed against the SwissProt database using the Mascot search engine. The Mascot search parameters were set as follows: taxonomy all entries; “trypsin” as enzyme allowing up to one missed cleavage, cysteine carbamidomethylation as a variable modification, ±0.6 Da fragment mass tolerance and ±100 ppm peptide mass tolerance.

Immunofluorescence

COS-7 cells grown on microscope slides were transfected with the pCTAP-NEU2 plasmid and 48 h after transfection fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. They were then washed three times with PBS for 5 min each time and permeabilized using PBS containing 0.3% TritonX100, followed by blocking with PBS containing 10% goat serum and 0.3% TritonX100). Primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-NEU2 (1:200, Novus Biologicals – NBP2-00783), and anti-β-actin (1:200, Sigma, A2066) and incubation was performed overnight at 4°C. The cells were extensively washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. The secondary antibodies used were as follows: Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:500, Cell Signaling, 4408) and Alexa Fluor 568 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:500, Abcam-ab175471) and incubation were performed for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were mounted with Fluoroshield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Abcam, ab104139). The images were acquired by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. GraphPad statistical software was used for the statistical analysis. All values are expressed as the mean±SEM. The differences were tested using one-way-ANOVA and t-tests. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of NEU2-tag in COS-7 cells

The human NEU2 gene was cloned into the pCTAP expression vector (Stratagene) to produce a NEU2-tag protein fused with streptavidin- and calmodulin-binding peptides at the C-terminus. A transient transfection procedure using PEI was used for COS-7 cells. For each transfection of the NEU2-tag, control transfections were carried out using pEGFP-N2 in parallel with a fraction of the same cell population. GFP gene was the reporter gene to monitor transfection efficiency and productivity.

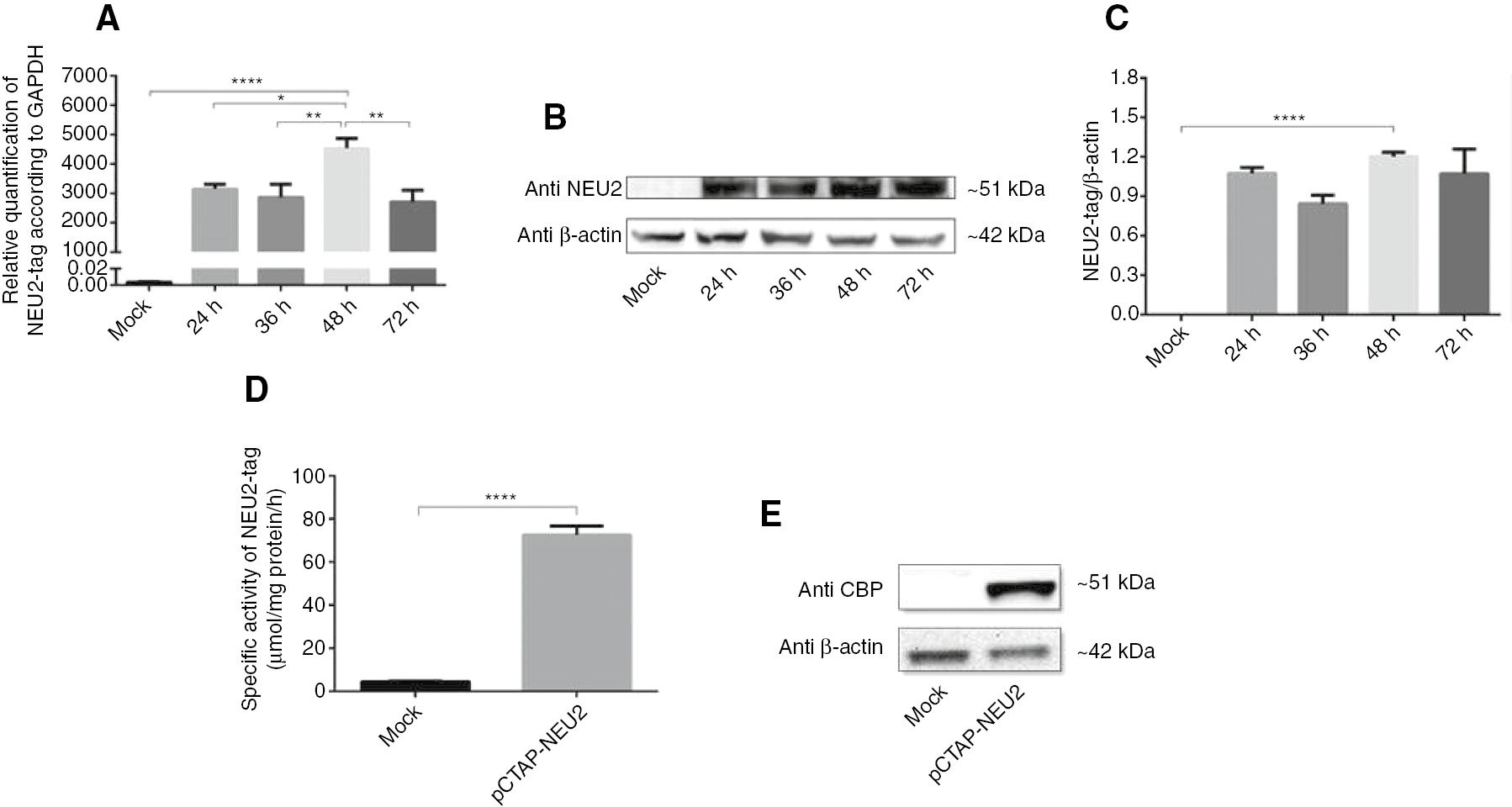

COS-7 cells were transfected with the pCTAP-NEU2 expression vector. The total RNA and proteins were isolated at 24, 36, 48, and 72 h after transfection. The real-time PCR (Figure 1A) and Western blot analysis (Figure 1B, C) revealed that the expression of NEU2-tag protein significantly increased in the 48-h post-transfection COS-7 cells. The band at 51 kDa indicates that the NEU2-tag protein was expressed only in the pCTAP-NEU2 transfected cells but not in the mock cells.

Transient expression of sialidase Neu2 in COS-7 cells.

NEU2-tag expression in COS-7 cells which were transiently transfected with the pCTAP-NEU2 plasmid (A) Real-time PCR analysis of NEU2-tag mRNA at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h after transfection. The relative levels of NEU2-tag mRNA were normalized using GAPDH as an internal control. (B) Western blot analysis of NEU2-tag protein using Anti-NEU2 primary antibody at 24, 36, 48 and 72 h after transfection. (C) The relative levels of NEU2-tag protein were normalized using β-actin as an internal control based on Image J. At 48 h after transfection (D) a significantly increase in sialidase activity against 4-MU-NeuAc was detected by enzyme activity assay and (E) NEU2-tag protein was determined using Anti-Calmodulin Binding Protein Epitope Tag (anti-CBP) primary antibody by Western blot analysis. Molecular weights of NEU2-tag and β-actin were 51 kDa and 42 kDa, respectively. The data are represented as the mean±SEM (n=3). One way and unpaired t-test were used for statistical analysis (*p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ****p<0.0001).

The sialidase enzyme activity of the NEU2-tag was determined using 4-MU-NeuAc following to the 48-h pCTAP-NEU2 transfection in COS-7 cell (Figure 1D). There was a significant (16-fold) increase in the activity of sialidase in the pCTAP-NEU2 transfected cells compared to the mock transfection. The presence of endogenously expressed NEU2 in the COS-7 cells leads to low sialidase activity in the mock transfection. The presence of the fused protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis with the anti-calmodulin binding protein epitope tag primary antibody (Figure 2D).

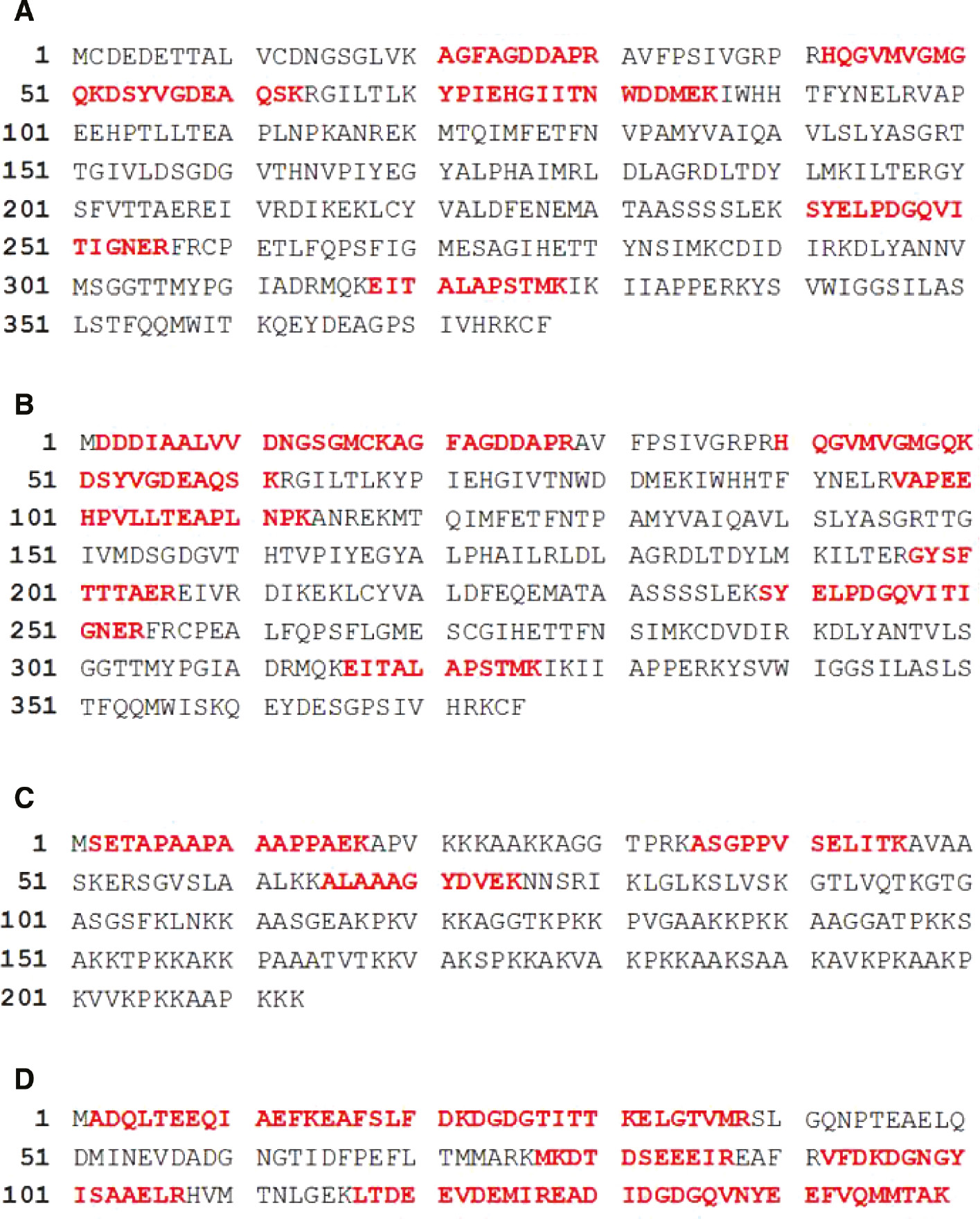

The amino acid sequences of identified proteins by LC-MS/MS analysis.

The sequence of coverage of (A) α-actin, (B) β-actin, (C) histone 1.2 and (D) calmodulin protein was shown. 19% of α-actin, 27% of β-actin, 18% of histone 1.2 and 65% of calmodulin amino acid sequence was matched with identified peptides. Matched peptides were shown as the bold red character.

Identification of NEU2 interacting proteins by mass spectrometry

The cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2 interacting proteins were obtained by a two-steps purification method according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Agilent Technologies). The tight binding of the streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) to streptavidin beads allowed the capture of NEU2 and its associated proteins which could subsequently be eluted in the presence of an excess amount of biotin. The calmodulin-binding peptide (CBP) tag, which binds to calmodulin beads in the presence of calcium was then used in a second purification step, after which the CBP-containing proteins could be eluted in the presence of EGTA to chelate the Ca2+. The final eluate contained all of the proteins that form complexes with NEU2-tag.

Five proteins; namely calmodulin, sialidase-2 (NEU2), α-actin, β-actin, and histone H1.2 were identified using InterPlay Mammalian TAP System followed by LC-MS/MS analysis as shown in Table 1. The MS/MS spectra were analyzed against the SwissProt database using the Mascot search engine. Ten different amino acid sequences belonging to α-actin and β-actin were identified by the LC-MS/MS analysis. Some of these are related to either α-actin or β-actin but some are found in both proteins (Figure 2A, B). α-Actin and β-actin consist of 377 and 375 amino acid, respectively. The sequences that were identified by LC-MS/MS analysis were matched to the amino acid sequences of α-actin and β-actin (19% and 27%, respectively) (Figure 2A, B). Furthermore, among three different sets of amino acid sequence data, one matched (18%) to the sequence of the 213 amino acid protein histone H-1.2 (Figure 2C).

Proteins detected in TAP following the 48 h post transfection with pCTAP-NEU2 in cos7 cells by LC-MS/MS analysis.

| Identified proteinsa | Accession numberb | Mascot scorec | Matches/significant matchesd | Sequences/significant sequencese | Massf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calmodulin | P62158 | 258 | 14/10 | 9/7 | 16,827 |

| Sialidase-2 | Q9Y3R4 | 205 | 11/9 | 9/7 | 42,683 |

| α-Actin | P62736 | 79 | 6/3 | 6/3 | 42,381 |

| β-Actin | P60709 | 73 | 9/5 | 8/4 | 42,052 |

| Histone H1.2 | P16403 | 44 | 3/2 | 3/2 | 21,352 |

aSignificant protein hits (p<0.05) are shown; p-value for extensive homology was calculated by Mascot database search.

bThe Uniprot accession number was shown here.

cMascot score >34 indicates identity for the matched peptides.

dNumber of peptide matches to the protein/peptide matches with p<0.05.

eNumber of distinct sequences matched to the protein/distinct peptide sequences with p<0.05.

fMolecular mass of identified protein in Dalton.

Ten different amino acid sequences (Table 1) with 65% sequence coverage (Figure 2D) to the calmodulin amino acid sequence were identified by the LC-MS/MS analysis. The CBP tag has a high affinity for the calmodulin resin in the presence of calcium. In our study, we found that the CBP tag is bound to both calmodulin and calmodulin resin during the second step of the purification, leading to false positive results. Nevertheless, calmodulin is a calcium-binding protein that regulates a multitude of different protein targets and, thereby affects many different cellular functions. In response to the calcium level, calmodulin might have different subcellular locations [23]. Therefore, we do not exclude the possibility that calmodulin interacts with NEU2.

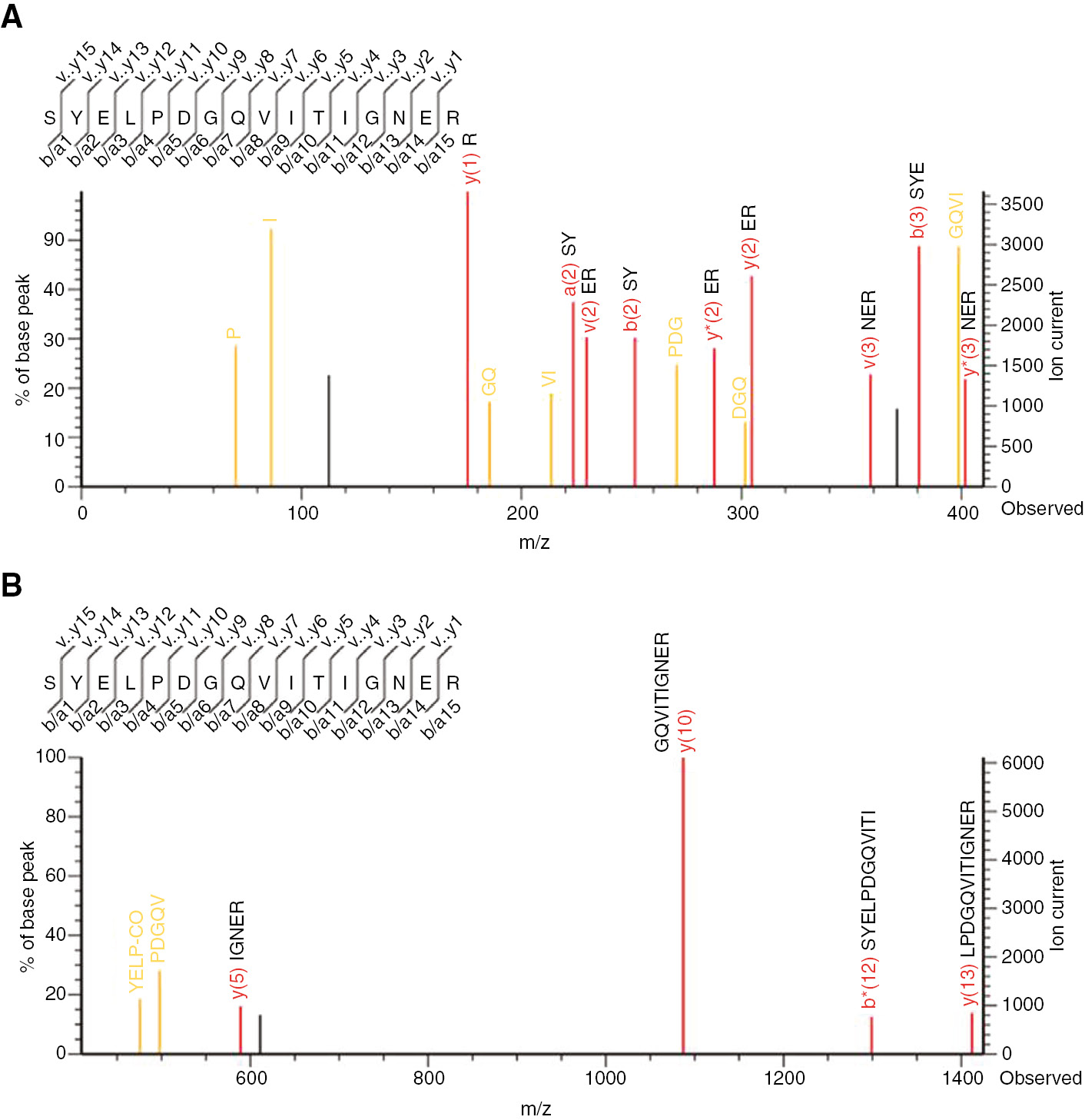

MALDI TOF//TOF analysis was also performed on the proteins obtained using the InterPlay Mammalian TAP System. The MS/MS ions were analyzed against the SwissProt database using the Mascot search engine, and MS/MS spectra corresponding to sialidase-2 (NEU2) and conserved peptides of α-actin and β-actin (Figure 3A, B) were detected.

MS/MS spectra of peptides obtained from the Mascot search engine by MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis.

Mass ranges (m/z) are (A) 0–410 and (B) 410–1420 for trypsin digested SYELPDGQVITIGNER peptide of α-actin and β-actin. Identified amino acids were shown in each spectrum.

The presence of actin filaments in two independent experiments, MALDI TOF//TOF and LC-MS/MS, supported the association of NEU2 with actin filaments. Actin filaments (both α-actin and β-actin) are an important part of the cytoskeleton. The polymerization and depolymerization of actin filaments are dynamic processes within the cells and they occur continuously to control cell shape, adhesion, division, and migration [24]. However, there may be other NEU2-associated protein(s) expressed at low level(s) in the mammalian cells. Their binding to NEU2 and mass spectrometric identification could be challenging as a result of the high concentration of actin filaments.

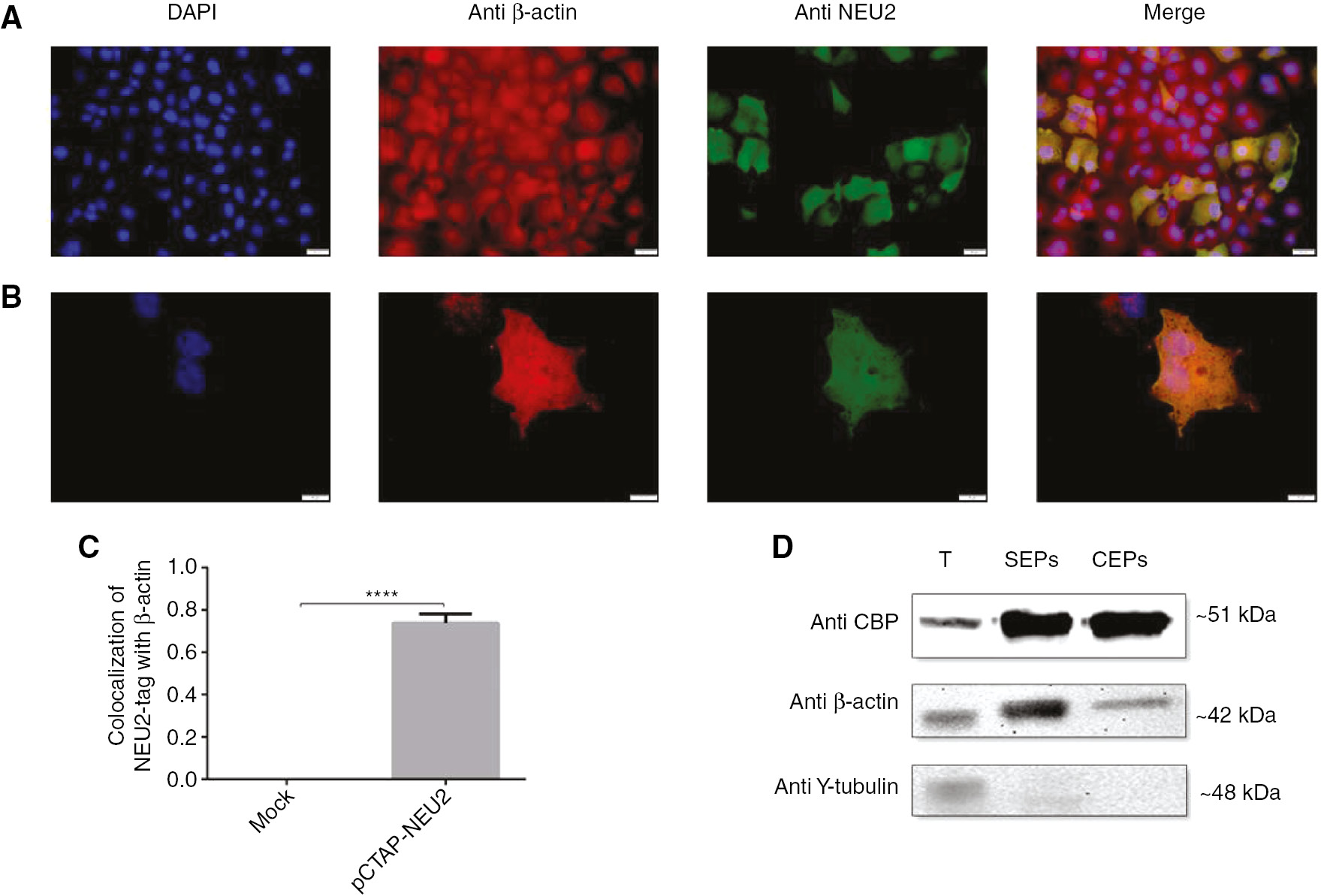

Confirmation of NEU2-tag association with β-actin protein

The localization of the NEU2-tag protein in the cell was determined by immunofluorescence analysis at 48 h after transfection with pCTAP-NEU2. It was found that the NEU2-tag protein was localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of the cell (Figure 4A, B). Immunofluorescence analysis was used to further elucidate the NEU2-tag and β-actin association in in vivo conditions. Double-immunocytochemical staining of cells showed colocalization of NEU2-tag with β-actin by fluorescence microscopy. The cells were stained with anti-NEU2 and anti-β-actin to localize NEU2-tag and actin filaments, respectively. The colocalization of NEU2-tag and β-actin was observed as yellow color (Figure 4A, B). Statistic for quantifying colocalization of pCTAP-NEU2 and β-actin was determined based on the Pearson correlation coefficient as 0.8 (Figure 4C). There was no colocalization between NEU2-tag and β-actin in mock transfected cell.

NEU2-tag protein was associated with β-actin in 48-h post transfected COS-7 cells.

Double-immunocytochemical staining of cells showed colocalization of NEU2-tag with β-actin. Scale bar, (A) 10 μm and (B) 20 μm. β-Actin protein was visualized in red, NEU2-tag in green, nuclei in blue. A yellow signal signified colocalization of NEU2-tag and β-actin. (C) Colocalization analysis of NEU2-tag with β-actin was determined by using Coloc 2 based on Pearson’s coefficients on Image J (n=10). (D) Western blot analysis of TAP-purified proteins showed that the interaction between NEU2-tag and β-actin was conserved during the step by purification. γ-Tubulin expression served as a negative control. Molecular weights of NEU2-tag, β-actin, and γ-tubulin were 51 kDa, 42 kDa, and 48 kDa, respectively. T, Total proteins isolated from the COS-7 cell at 48 h after transfection with pCTAP-NEU2; SEP(s), proteins obtained at the streptavidin elution step; CEP(s), proteins obtained at the calmodulin elution step. The data are represented as the mean±SEM. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis (****p<0.0001).

To validate the interaction of NEU2-tag with β-actin protein, the Western blot analysis was performed using anti-CBP, anti-β-actin and γ-tubulin antibodies (Figure 4D). We found that the housekeeping protein β-actin interacts with NEU2. This interaction was conserved through the two-step purification involving elution from streptavidin and calmodulin beads with biotin and EGTA, respectively. However, we found no association with the other housekeeping protein such as γ-tubulin, as it was not detected in the proteins eluted from the streptavidin or calmodulin beads. This demonstrated that β-actin clearly interacts with NEU2-tag under in vitro conditions.

Discussion

Cytosolic sialidase (NEU2) plays an important role in cancer metabolism [8], neuronal [9] and myoblast differentiation, proliferation, and hypertrophy [[10], [11], [12] by removing sialic acids from oligosaccharides, glycoproteins, and gangliosides 2]. However, one important and unresolved question has been the identification of the possible protein(s) within the cell that interact(s) with NEU2 as it carries out its function [1], [2]. To identify the protein(s) that specifically interact with NEU2, we performed tandem affinity purification and mass spectrometry analysis. α-Actin, β-actin, histone H1.2 and calmodulin were identified as potential proteins that associate NEU2. Further investigations are required to show the association of NEU2 with histone H1.2 and calmodulin.

Previously, it was reported that NEU2 is preferentially localized in the nucleoplasm of rat skeletal muscle fibers, as determined using immunogold particles [25]. Here, we have shown that the NEU2-tag protein was localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of the COS-7 cells (Figure 4A, B). We speculate that the localization of the cytosolic sialidase to the chromatin might be mediated by histone H1.2 which is the histone linker protein involved in nucleosome spacing and gene regulation [26].

The role of NEU2 in cancer metabolism was shown in K562 cells which normally lack NEU2. However, the study showed that after transfection with a plasmid carrying NEU2, these cells quickly underwent apoptosis [6]. It was also known that Bcr/Abl binds to monomeric and filamentous actin via an actin-binding domain at the C terminus of the protein [27]. This interaction is necessary for Bcr/Abl localization to the plasma membrane, induction of cytoskeletal changes, alterations of cell adhesion, and transformation of cells [28]. Deletion of the actin-binding domain of Bcr/Abl decreased its transformation ability. At least 70% of the Bcr/Abl protein is localized to the cytoskeleton [29]. Based on our study, we speculate that the reason for apoptosis in the NEU2-transfected cells might be the high amount of NEU2, which interacts with the actin filaments and then leads to decrease in the interaction between the Bcr/Abl protein and the cytoskeleton.

In another study, it has been shown that the overexpression of NEU2 in myoblast cells induces myoblast differentiation [11]. The regulation of myoblast fusion into multinucleated myofibers involves an orderly sequence of events, from initial recognition and adhesion to alignment, and finally plasma membrane fusion. These processes depend upon coordinated remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton [30]. The pharmacological inhibition of actin polymerization leads to decreased myoblast fusion by actin cytoskeleton remodeling [31]. The role of NEU2 in myoblast differentiation might be related to the effects of actin cytoskeleton remodeling on myoblast fusion. We suggest that NEU2 might play a role in the activation of the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton.

The influence of NEU2 on neuronal differentiation was also studied in PC12 cells [9]. It has been shown that the maturation of dendritic spines in developing neurons during synaptogenesis is facilitated by actin remodeling [32]. Therefore, we speculate that NEU2 might be also involved in neuronal differentiation by the remodeling of actin through desialylation.

In this study, NEU2 associated protein(s) in mammalian cells was identified first time by using a two-step tandem affinity purification technique followed by mass spectrometry analysis. α-Actin, β-actin, histone H1.2 and calmodulin were identified as proteins that associating with NEU2 and contribute to its biological role in various cellular events.

Acknowledgements

Dr. V. Seyrantepe is thankful for the 2010 EMBO Installation Grant 2011-3. We thank Dr. T. Baysal and the Marmara Research Center (Kocaeli, Turkey) for assistance with the LC-MS/MS analysis. We also thank Dr. T. Yalçın and the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Laboratory at the (Izmir Institute of Technology, Izmir, Turkey) for help with the MALDI TOF/TOF analysis. We are grateful to Biotechnology and Bioengineering Research and Application Center at the Izmir Institute of Technology for their help with the imaging of the Western blot results. Part of this work presented in Secil Akyildiz Demir’s Master thesis [33].

Competing interests statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Monti E, Bonten E, D’Azzo A, Bresciani R, Venerando B, Borsani G, et al. Sialidases in vertebrates: a family of enzymes tailored for several cell functions. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem 2010;64:403–79.10.1016/S0065-2318(10)64007-3Search in Google Scholar

2. Miyagi T, Yamaguchi K. Mammalian sialidases: physiological and pathological roles in cellular functions. Glycobiology 2012; 22:880–96.10.1093/glycob/cws057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Seyrantepe V, Landry K, Trudel S, Hassan JA, Morales CR, Pshezhetsky AV. Neu4, a novel human lysosomal lumen sialidase, confers normal phenotype to sialidosis and galactosialidosis cells. J Biol Chem 2004;279:37021–9.10.1074/jbc.M404531200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Yamaguchi K, Hata K, Koseki K, Shiozaki K, Akita H, Wada T, et al. Evidence for mitochondrial localization of a novel human sialidase (NEU4). Biochem J 2005;390:85–93.10.1042/BJ20050017Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Bigi A, Morosi L, Pozzi C, Forcella M, Tettamanti G, Venerando B, et al. Human sialidase NEU4 long and short are extrinsic proteins bound to outer mitochondrial membrane and the endoplasmic reticulum, respectively. Glycobiology 2009;20:148–57.10.1093/glycob/cwp156Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Koseki K, Wada T, Hosono M, Hata K, Yamaguchi K, Nitta K, et al. Human cytosolic sialidase NEU2-low general tissue expression but involvement in PC-3 prostate cancer cell survival. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012;428:142–9.10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Monti E, Preti A, Rossi E, Ballabio A, Borsani G. Cloning and characterization of NEU2, a human gene homologous to rodent soluble sialidases. Genomics 1999;57:137–43.10.1006/geno.1999.5749Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Tringali C, Lupo B, Anastasia L, Papini N, Monti E, Bresciani R, et al. Expression of sialidase Neu2 in leukemic K562 cells induces apoptosis by impairing Bcr-Abl/Src kinases signaling. J Biol Chem 2007;282:14364–72.10.1074/jbc.M700406200Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Fanzani A, Colombo F, Giuliani R, Preti A, Marchesini S. Cytosolic sialidase Neu2 upregulation during PC12 cells differentiation. FEBS Lett 2004;566:178–82.10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Sato K, Miyagi T. Involvement of an endogenous sialidase in skeletal muscle cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;221:826–30.10.1006/bbrc.1996.0681Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Fanzani A, Giuliani R, Colombo F, Zizioli D, Presta M, Preti A, et al. Overexpression of cytosolic sialidase Neu2 induces myoblast differentiation in C2C12 cells. FEBS Lett 2003;547:183–8.10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00709-9Search in Google Scholar

12. Rossi S, Stoppani E, Martinet W, Bonetto A, Costelli P, Giuliani R, et al. The cytosolic sialidase Neu2 is degraded by autophagy during myoblast atrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009;1790: 817–28.10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Séraphin B. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol 1999;17:1030–2.10.1038/13732Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Burckstummer T, Bennett KL, Preradovic A, Schu G, Hantschel O, Superti-furga G, et al. An efficient tandem affinity purification procedure for interaction proteomics in mammalian cells. Nat Methods 2006;3:1013–9.10.1038/nmeth968Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Van Impe K, Hubert T, De Corte V, Vanloo B, Boucherie C, Vandekerckhove J, et al. A new role for nuclear transport factor 2 and Ran: nuclear import of CapG. Traffic 2008;9:695–707.10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00720.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Ahlstrom R, Yu AS. Characterization of the kinase activity of a WNK4 protein complex. Am Physiol Soc 2009;297:685–92.10.1152/ajprenal.00358.2009Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Hentschke M, Berneking L, Belmar Campos C, Buck F, Ruckdeschel K, Aepfelbacher M. Yersinia virulence factor YopM induces sustained RSK activation by interfering with dephosphorylation. PLoS One 2010;5:e13165.10.1371/journal.pone.0013165Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Sharma P, Ignatchenko V, Grace K, Ursprung C, Kislinger T, Gramolini AO. Endoplasmic reticulum protein targeting of phospholamban: a common role for an N-terminal di-arginine motif in ER retention? PLoS One 2010;5:e11496.10.1371/journal.pone.0011496Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Park MS, Chu F, Xie J, Wang Y, Bhattacharya P, Chan WK. Identification of cyclophilin-40-interacting proteins reveals potential cellular function of cyclophilin-40. Anal Biochem 2012;410: 257–65.10.1016/j.ab.2010.12.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Fanzani A, Colombo F, Giuliani R, Preti A, Marchesini S. Insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling regulates cytosolic sialidase Neu2 expression during myoblast differentiation and hypertrophy. FEBS J 2006;273:3709–21.10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05380.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Wisniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat Methods 2009;6:3–8.10.1038/nmeth.1322Search in Google Scholar

22. Haçarız O, Sayers G, Baykal AT. A proteomic approach to investigate the distribution and abundance of surface and internal Fasciola hepatica proteins during the chronic stage of natural liver fluke infection in cattle. J Proteome Res 2012;11:3592–604.10.1021/pr300015pSearch in Google Scholar

23. Chin D, Means AR. Calmodulin: a prototypical calcium sensor. Trends Cell Biol 2000;10:322–8.10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01800-6Search in Google Scholar

24. Bunnell TM, Burbach BJ, Shimizu Y, Ervasti JM. β-Actin specifically controls cell growth, migration, and the G-actin pool. Mol Biol Cell 2011;22:4047–58.10.1091/mbc.e11-06-0582Search in Google Scholar

25. Akita H, Miyagi T, Hata K, Kagayama M. Immunohistochemical evidence for the existence of rat cytosolic sialidase in rat skeletal muscles. Histochem Cell Biol 1997;107:495–503.10.1007/s004180050137Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Fan Y, Nikitina T, Zhao J, Fleury TJ, Bhattacharyya R, Bouhassira EE, et al. Histone H1 depletion in mammals alters global chromatin structure but causes specific changes in gene regulation. Cell 2005;123:1199–212.10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.028Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. McWhirter JR, Wang JY. An actin-binding function contributes to transformation by the Bcr-Abl oncoprotein of Philadelphia chromosome-positive human leukemias. EMBO J 1993;12: 1533–46.10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05797.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Wertheim JA, Perera SA, Hammer DA, Ren R, Boettiger D, Pear WS. Localization of BCR-ABL to F-actin regulates cell adhesion but does not attenuate CML development. Blood 2003;102:2220–8.10.1182/blood-2003-01-0062Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Salgia R, Li JL, Ewaniuk DS, Pear W, Pisick E, Burky SA, et al. BCR/ABL induces multiple abnormalities of cytoskeletal function. J Clin Invest 1997;100:46–57.10.1172/JCI119520Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Abramovici H, Gee SH. Morphological changes and spatial regulation of diacylglycerol kinase-zeta, syntrophins, and Rac1 during myoblast fusion. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2007;64:549–67.10.1002/cm.20204Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Nowak SJ, Nahirney PC, Hadjantonakis AK, Baylies MK. Nap1-mediated actin remodeling is essential for mammalian myoblast fusion. J Cell Sci 2009;122:3282–93.10.1242/jcs.047597Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Sekino Y, Kojima N, Shirao T. Role of actin cytoskeleton in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Neurochem Int 2007;51:92–104.10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Akyildiz Demir S. Identification of Cytosolic Sialidase Neu2 Associated Proteins by Mass Spectrometric Analysis, (Master in Science) [M.S. Thesis] Izmir Institute of Technology, Faculty of Science, Molecular Biology and Genetics Department, Izmir, Turkey, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery