Abstract

Background

Marine-derived fungi are appraised as a favorable source for discovering new bioactive secondary metabolites. In the last few decades researchers have concentrated on marine-derived fungi to obtain new and pharmaceutically active bioactive secondary metabolites with therapeutic potential.

Objective

In this study three marine-derived fungi were isolated and identified from marine invertebrates and investigated with regard to their antioxidant and cytotoxic activities.

Materials and methods

DPPH, SO, NO, and ABTS assays were used for monitoring free radical scavenging activity, and the MTT assay was used for testing cytotoxic activity against HCT-116 colon cancer cells.

Results

According to the obtained results Malassezia restricta extract was shown to have the highest antioxidant and cytotoxic activities compared to the other tested fungi strains.

Conclusion

This study is the first report about the antioxidant and cytotoxicity activity of Acremonium sclerotigenum, Aspergillus flavus, and M. restricta. This serves as a valuable preliminary study for activity-guided isolation of secondary metabolites.

Öz

Önbilgi

Deniz kaynaklı mantarlar, yeni biyoaktif sekonder metabolitlerin keşfedilmesi için uygun bir kaynak olarak değerlendirilmektedir. Son yıllarda, deniz kaynaklı mantarlar terapötik potansiyeli olan yeni biyoaktif sekonder metabolitlerin keşfi için araştırmacılar tarafından odak noktası haline gelmiştir.

Amaç

Bu çalışmada 3 deniz kaynaklı mantar, Türkiye denizlerinde yaşayan omurgasızlarından izole edilmiş, türleri teşhis edildikten sonra antioksidan ve sitotoksik aktiviteleri açısından araştırılmıştır.

Gereç ve Yöntemler

Deniz kaynaklı mantarların ekstrelerinin serbest radikal süpürücü aktivitelerini ölçmek için DPPH, SO, NO ve ABTS yöntemler ile ölçülmüştür, ve MTT yöntemi ile sitotoksik aktiviteleri, HCT 116 kolon kanseri hücrelerine karşı kullanılmıştır.

Bulgular

Elde edilen sonuçlara göre, Malassezia restricta ekstresi test edilen diğer mantar suşları göre en yüksek antioksidan ve sitotoksik aktiviteler gösterdiği görülmüştür.

Sonuç

Bu çalışma Acremonium sclerotigenum, Aspergillus flavus, Malassezia restricta’nın antioksidan ve sitotoksisite aktivitesi ile ilgili ilk rapordur. Bu çalışmanın önemli bir avantajı, sekonder metabolitlerin aktivite kılavuzlu izolasyonu için bir ön çalışmadır.

Introduction

In recent years, research on metabolites from marine sources such as macroalgae and sponges has increased. Research on the secondary metabolites of marine microorganisms is also a rapidly growing field. There is a theory that a number of metabolites obtained from marine algae and invertebrates may be produced by associated microorganisms [1]. The marine environment is a unique source of structurally diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites. Some marine-derived secondary metabolites have shown great ability to be used as therapeutic agents. Such metabolites, including bryostatin, plinabulin, phenylahistin, halimide, trabectedin, and cyanosafracin, are being used in clinical or preclinical evaluation [2], [3]. Cytarabine, vidarabine, and ziconotide exist in the marine pharmaceutical pipeline, approved by the FDA. There are also 13 marine-derived compounds that are being applied in Phase I, Phase II, or Phase III clinical trials [4]. Over 22,000 secondary metabolites have been isolated from marine organisms over the last 50 years. The marine environment, with unique conditions of pressure, temperature, salt, and light, leads microorganisms to produce structurally different secondary metabolites [5]. Marine-derived microbial communities, due to their extensive genetic and biochemical diversity, have a wide range of bioactivities including antibacterial, antifungal [6], antidiabetic [7], antiinflammatory [8], antiprotozoal [9], antituberculosis [10], antiviral [11], antitumor, and cytotoxic activities [12] and they have become a leading hotspot for the discovery of new pharmaceutically active compounds. In this study the antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of three marine-derived fungi are investigated. This is the first study about the bioactivity of Acremonium sclerotigenum, Aspergillus flavus, and Malassezia restricta.

Materials and methods

General

1,1-Diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium (ABTS), (±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), ascorbic acid, quercetin, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-terazoliumbromide (MTT), sulfanilamide, naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, and sea salts, RPMI, medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin, and glutamine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Sabouraud 4% dextrose agar, Mueller Hinton broth, Sabouraud dextrose broth, and ethyl acetate were purchased from Merck were from PAA. Nutrient agar was from Oxoid. The Biospeedy® Fungal Diversity Kit was obtained from Bioeksen (Turkey) and the Bio-Rad CFX Connect detection system was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (USA). The ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems) and Spectra MAX 190 Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) were also used.

Marine sample collection and fungi isolation

Marine samples were collected from the Turkish Marmara and Seferihisar coasts by scuba diving and were transferred in sea water. The isolation process was carried out within the few hours. The samples were cut to approximately 1×1 cm and rinsed three times with sterile water to eliminate adherent surface debris; for surface sterilization, they were immersed in 70% EtOH (vol/vol) for 60–120 s. Samples were transferred to Sabouraud 4% dextrose agar and artificial sea salt petri dishes. The fungi species were kept for 5–7 days in natural light at 25°C [13]. Sample information is provided in Table 1.

Obtained fungal strains from marine species.

| Fungus strains | Species | Origin | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acremonium sclerotigenum | Haliclona sarai | Sponge | Marmara |

| Aspergillus flavus | Axinella polypoides | Sponge | Seferihisar |

| Malassezia restricta | Pachycerianthus multiplicatus | Sea anemone | Marmara |

Fungi identification

Fungi strains were identified by DNA isolation using a fungal DNA isolation kit. The PCR-based Biospeedy® Fungal Diversity Kit was used to determine fungal diversity after spectrophotometric quality checks of the obtained DNA. The kit contains the forward primer (TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC) and reverse primer (GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG) pair and optimized qPCR (real-time PCR) chemistry specific to the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region in the fungal genomic DNA. All reactions were performed using Bio-Rad CFX Connect qPCR. The device was subjected to an optimized thermocycler program specific to the primer pair and melting curve analysis between 65°C and 95°C to determine that only the desired product was amplified during qPCR. The qPCR results were analyzed with Bio-Rad CFX Connect Software 3.0.

Sequences of the fungi amplicons were identified by the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit using ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer. The sequence obtained for each fungal sample was analyzed with the Chromas software package, version 1.45 (http://www.technelysium.com/au/chromas.html).

The sequences were compared with NCBI DNA database ITS regions identified from known fungal species and paired with the most similar species (BLAST: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). In this step, sequences with similarity of ≥98% were considered to belong to the same species [14].

Fungi extraction

Identified fungi were cultured on rice and artificial sea salt medium in Erlenmeyer flasks and were kept for 30 days in natural light at 25°C. After 30 days the grown fungi were subjected to extraction by ethyl acetate. The extracts were evaporated under vacuum and kept at 4°C until used [13].

Cell culture

HCT-116 colon cancer cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium added with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin and were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. When cells were 80% confluent, they were passaged by trypsinization.

Cell viability assay

To test the cytotoxic activities of fungi extracts against HCT-116 colon cancer cells, the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) test was performed [15]. HCT-116 cells (2×104) were seeded in 96-well plates. After overnight incubation, cells were incubated with different concentrations of fungal extracts (1–60 μg/mL) for 72 h. Stock solutions of fungi extracts were prepared in DMSO. Final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.5%. Equal amounts of DMSO were added to the control group. Camptothecin was used as a positive control. MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was prepared in PBS and cells were incubated with MTT solution for 4 h. Insoluble formazan crystals were dissolved by adding acidified SDS solution. Absorbance measurement at 550 nm was performed with a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific). IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA).

DPPH antioxidant activity determination

Different concentrations of EtOAc extracts were added in an equal volume to methanolic DPPH solution (0.1 mM). The mixture was remained at room temperature. The absorbance of the mixture was recorded at 517 nm after 30 min. Ascorbic acid and quercetin were used as standards [16].

ABTS antioxidant activity determination

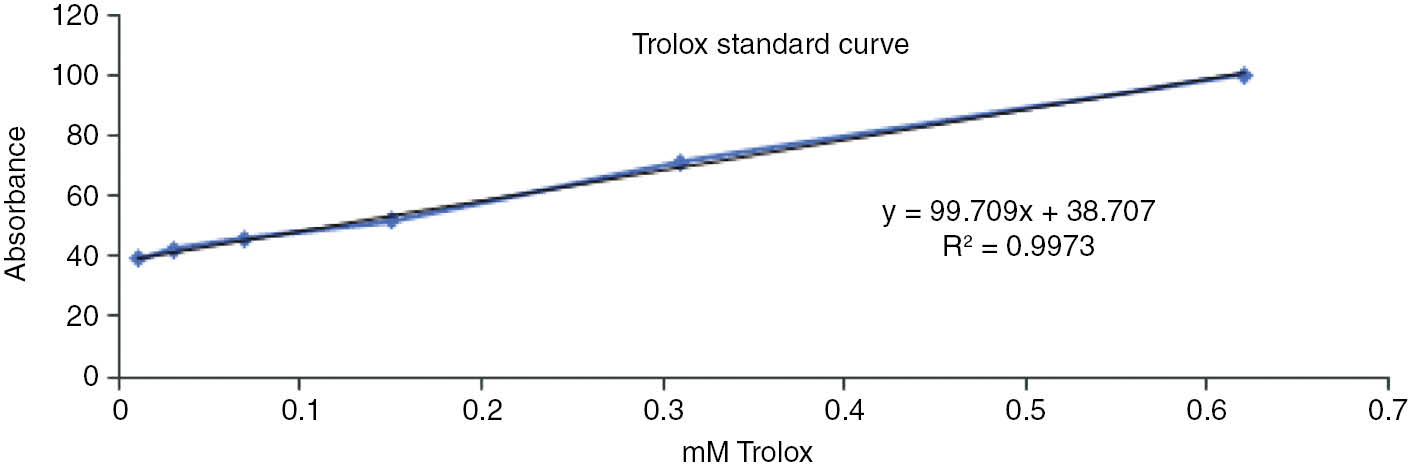

According to Huang et al. (2010), ABTS+ stock solution (7.4 mM ABTS in 2.6 mM potassium persulfate solution) was prepared and was allowed to react for 12–16 h at room temperature in the dark. ABTS+ solution absorbance must be around 0.7±0.02 units at 734 nm. In a final volume of 300 μL, the reaction mixture comprising 275 μL of ABTS+ solution was added to 25 μL of the crude extract at various concentrations. Absorbances of mixtures were measured at 734 nm in microplate reader. The calibration curve was calculated by the same methods to Trolox as standard antioxidant compound [17].

Superoxide radical scavenging activity by alkaline DMSO method (SO)

Superoxide radical scavenging activities of the extracts were determined by alkaline DMSO method. Briefly, nonenzymatic system was used for obtain the superoxide radical. To 1 mL of alkaline DMSO (5 mM NaOH in 0.1 mL of water) were added 10 μL of NBT (1 mg/mL) and 30 μL of different concentrations of extracts or standard compounds. To get final volume 140 μL DMSO added to mixture. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a microplate reader [18].

Nitric oxide radical scavenging activity (NO)

Briefly, 60 μL of serial diluted extract was added to 60 μL of sodium nitroprusside (10 mM phosphate buffered saline) and incubated 150 min under at 25°C. Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) was added to each test tube an equal volume. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 10 min and absorbance at 577 nm was measured using a microplate reader [19].

Radical scavenging activity was calculated by the following formula for all antioxidant assay:

For IC50 values, GraphPad Prism software were used. All tests were performed in triplicate and standard deviation of all values were calculated.

Results

Collected samples, collection locations, and isolated fungal strains are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

The collected marine samples; (A) Haliclona sarai, (B) Axinella polypoides, (C) Pachycerianthus multiplicatus.

The antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of the isolated fungal species were evaluated. The antioxidant activity of the marine-derived fungal extracts was determined by DPPH, ABTS, SO, and NO radical scavenging activity.

The antioxidant potentials of the EtOAc extracts were also quantified by reference to a Trolox standard calibration curve. The calibration curve is linear in the range of 0.01–0.125 mM for Trolox, with an equation of y=99.709x+38.707 and a correlation coefficient of r2=0.9973. The Trolox standard curve is shown in Figure 2.

Trolox calibration curve for the TEAC assay.

According to the results, M. restricta showed higher antioxidant activity than the other tested fungi species. All extracts were shown moderate and dose dependent activity. Furthermore, the Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) of M. restricta was greater than that of the other tested fungi species. This means that M. restricta, possessing more antioxidant compounds or secondary metabolites, has greater synergy than the other tested species. The results are shown in Table 2.

Antioxidant activity of marine derived fungi extracts.

| Ethyl acetate extract | IC50 (mg/mL) | TEAC (mmTrolox/mgExtract) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | SO | NO | ABTS | ||

| Acremonium sclerotigenum | 2.28±1.25 | 2.16±0.25 | 2.41±1.89 | 1.42±1.9 | 0.023±1.9 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 3.15±0.94 | 3.25±0.66 | 3.23±1.08 | 2.43±1.68 | 0.017±1.68 |

| Malassezia restricta | 1.22±1.21 | 1.07±0.97 | 1.2±1.07 | 0.67±0.91 | 0.031±0.91 |

| Ascorbic acid | 0.005±0.89 | 0.008±0.78 | 0.01±0.19 | 0.008±0.91 | – |

| Quercetin | 0.007±0.94 | 0.01±0.28 | 0.013±0.15 | 0.011±0.23 | – |

All extracts were tested for their cytotoxic activity against the HCT-116 (human colon cancer) cell line, as shown in Table 3. All extracts were shown dose dependent activity. The A. sclerotigenum ethyl acetate extract was inactive against the HCT 116 cell line in the tested range. However, the M. restricta ethyl acetate extract exhibited higher cytotoxic activity than the other tested fungi species. Camptothecin was used as a standard in this study.

Cytotoxic activity of marine-derived fungal extracts against the HCT-116 cell line.

| Ethyl acetate extract | IC50 μg/mL±SD |

|---|---|

| Acremonium sclerotigenum | >40 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 25.91±0.86 |

| Malassezia restricta | 10.24±1.77 |

| Camptothecin | 0.137±0.03 |

Discussion

From penicillin to phenylahistin, microorganisms produce vital pharmaceuticals for humans to use in the treatment of bacterial or fungal infections, viral infections, cancers, and so on. In this study, three marine-derived fungi, A. sclerotigenum, A. flavus, and M. restricta, were screened for their bioactivity. According to the literature survey, there are extremely limited studies on the bioactivity screening of A. sclerotigenum, A. flavus, and M. restricta.

Acremonium sclerotigenum was isolated from the leaves of Terminalia bellerica. The crude ethyl acetate extract of this fungus was screened for siderophore production and antibacterial activity against Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) bacteria. The antimicrobial activity (zone of inhibition) of the A. sclerotigenum crude extract was between 3.0 and 12 mm in diameter. This extract also showed positive siderophore activity (iron chelation) [20].

Aflatoxin, aflatrem, cyclopiazonic acid, kojic acid, aflavarin, leporin, piperazine, ditryptophenaline, and asparasone A are the most abundant secondary metabolites produced by A. flavus [21], [22]. 5-Chloro-2-methoxy-N-phenylbenzamide and 5-acetoxy-3-hydroxy-3-methylpentanoic acid were isolated from terrestrial A. flavus and the in vitro cytotoxicity of these compounds was evaluated against a human cervix carcinoma cell line (KB-3-1), but no noticeable activity was shown [23]. Thirty-one secondary metabolites were identified by GC-mass spectroscopic method in the methanolic extract of A. flavus [24]. Aspergillus flavus was isolated from soil in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, and the crude extract of the fungus was shown to have moderate effect against Candida albicans, Penicillium notatum, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Acremonium alternatum (80%, 44%, 66%, and 53% inhibition, respectively) [25]. Crude extract of A. flavus was shown to have higher antifungal activity than ketoconazole (MIC: 0.3 mg/mL) [26].

The present study aimed to evaluate the antioxidant and cytotoxicity activity of A. sclerotigenum, A. flavus, and M. restricta. The results showed that M. restricta ethyl acetate extract was more active than extracts of the other tested marine-derived fungi.

In conclusion, the oceans constitute over 90% of the habitable space on the planet, and the significance of the biological and chemical diversity of marine environments is known. Turkey has long coastlines with considerable marine biodiversity. This study has demonstrated the bioactivities of three Turkish marine-derived fungi, which were not studied before.

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Kelecom A. Secondary metabolites from marine microorganisms. An Acad Bras Cienc 2002;74:151–70.10.1590/S0001-37652002000100012Search in Google Scholar

2. Shukala S. Secondary metabolites from marine microorganism and therapeutic agency. Indian J Geomarine Sci 2016;45:1245–54.Search in Google Scholar

3. Zhao C, Liu H, Zhu W. New natural products from the marine-derived Aspergillus fungi – a review. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2016;56:331–62.Search in Google Scholar

4. Saleem M, Nazir M. Bioactive natural products from marine-derived fungi: an update. Stud Nat Prod Chem 2015;45:297–361.10.1016/B978-0-444-63473-3.00009-5Search in Google Scholar

5. Zin WW, Buttachon S, Dethoup T, Pereira JA, Gales L, Inácio Â, et al. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of the metabolites isolated from the culture of the mangrove-derived endophytic fungus Eurotium chevalieri KUFA 0006. Phytochemistry 2017;141:86–97.10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.05.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Xu L, Meng W, Cao C, Wang J, Shan W, Wang Q. Antibacterial and antifungal compounds from marine fungi. Mar Drugs 2015;13:3479–513.10.3390/md13063479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. El-Hady FK, Abdel-Aziz MS, Abdou AM, Shaker KH, Ibrahim LS, El-Shahid ZA. In vitro anti-diabetic and cytotoxic effect of the coral derived fungus (Emericella unguis 8429) on human colon, liver, breast and cervical carcinoma cell lines. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2014;27:296–301.Search in Google Scholar

8. Shin HJ, Pil GP, Heo SJ, Lee HS, Lee JS, Lee YJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of tanzawaic acid derivatives from a marine-derived fungus Penicillium steckii 108YD142. Mar Drugs 2016;14:14–9.10.3390/md14010014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Pontius A, Krick A, Kehraus S, Brun R, König GM. Antiprotozoal activities of heterocyclic-substituted xanthones from the marine-derived fungus Chaetomium sp. J Nat Prod 2008;71: 1579–84.10.1021/np800294qSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Luo X, Zhou X, Lin X, Qin X, Zhang T, Wang J, et al. Antituberculosis compounds from a deep-sea-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. Nat Prod Res 2017;31:1958–62.10.1080/14786419.2016.1266353Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Moghadamtousi SZ, Nikzad S, Kadir HA, Abubakar S, Zandi K. Potential antiviral agents from marine fungi: an overview. Mar Drugs 2015;13:4520–38.10.3390/md13074520Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Ramos AA, Preta-Sena M, Castro-Carvalho B, Dethoup T, Buttachon S, Kijjoa A, et al. Potential of four marine-derived fungi extracts as anti-proliferative and cell death-inducing agents in seven human cancer cell lines. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2015;8:798–806.10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.09.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Kjer J, Debbab A, Aly AH, Proksch P. Methods for isolation of marine-derived endophytic fungi and their bioactive secondary products. Nat Protoc 2010;5:479–90.10.1038/nprot.2009.233Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Sun Y, Cai Y, Huse SM, Knight R, Farmerie WG, Mai V. A large-scale benchmark study of existing algorithms for taxonomy- independent microbial community analysis. Brief Bioinform 2011;13:107–21.10.1093/bib/bbr009Search in Google Scholar

15. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 1983;65:55–63.10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Search in Google Scholar

16. Shirwaikar A, Shirwaikar A, Rajendran K, Punitha IS. In vitro antioxidant studies on the benzyl tetra isoquinoline alkaloid berberin. Biol Pharm Bull 2006;29:1906–10.10.1248/bpb.29.1906Search in Google Scholar

17. Huang MH, Huang SS, Wang BS, Wu CH, Sheu MJ, Hou WC, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of Cardiospermum halicacabum and its reference compounds ex vivo and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol 2010;133:743–50.10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.005Search in Google Scholar

18. Harput US, Genç Y, Khan N, Saracoglu I. Radical scavenging effects of different Veronica species. Rec Nat Prod 2011;5:100–7.Search in Google Scholar

19. Senthil Kumar R, Rajkapoor B, Perumal P. Antioxidant activities of Indigofera cassioides Rottl. Ex. DC. using various in vitro assay models. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012;2:256–61.10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60019-7Search in Google Scholar

20. Prathyusha P, Rajitha Sri AB, Ashokvardhan T, Satya Prasad K. Antimicrobial and siderophore activity of the endophytic fungus Acremonium sclerotigenum inhabiting Terminalia bellerica Roxb. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res 2015;30:84–7.Search in Google Scholar

21. Amare MG, Keller MP. Molecular mechanisms of Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolism and development. Fungal Genet Biol 2014;66:11–8.10.1016/j.fgb.2014.02.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Cary JW, Gilbert MK, Lebar MD, Majumdar R, Calvo AM. Aspergillus flavus secondary metabolites: more than just aflatoxins. J Food Safety 2018;6:7–32.10.14252/foodsafetyfscj.2017024Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Eliwa EM, El-Metwally MM, Halawa AH, El-Agrody AM, Bedair AH, Shaaban M. New bioactive metabolites from Aspergillus flavus 9AFL. J Atoms Mol 2017;7:1045–55.Search in Google Scholar

24. Mohammed GJ, Hameed IH, Kama SA. Study of secondary metabolites produced by Aspergillus flavus and evaluation of the antibacterial and antifungal activity. Afr J Biotechnol 2016;7:107–25.Search in Google Scholar

25. Ahmad B, Rizwan M, Azam S, Rauf A, Bashir S, Ahmad J. In vitro antifungal and phytotoxic study of metabolites extracted from Aspergillus flavus. Am-Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci 2016;16:1196–99.Search in Google Scholar

26. Wierzbinska A. Evaluation of bioactive potential of a secondary metabolite produced by Penicillium nordicum. MSc, Polytechnic Institute of Bragança – Agricultural School: Bragança, Portugal, 2017. Available online athttps://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/bitstream/10198/14396/1/Agata%20Final%20thesis.pdf (last accessed: January 2019).Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery