Abstract

Objectives

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the B-lymphocyte surface antigen CD20. It is used in the treatment of some diseases including B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL). There are a lot of data regarding effect of Rituximab on lymphoma cells. But, there is no satisfactory information about the effect of Rituximab on the signaling pathways in leukemia cells. In this study, it was aimed to understand the effect of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) and B-CLL.

Material and methods

Apoptotic effect of Rituximab in the TANOUE (B-ALL) and EHEB (B-CLL) cell lines were evaluated by using the Annexin V method. mRNA expression levels of STAT3 and RelA were analysed by quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR). Alterations in STAT3 and RelA protein expressions were detected by using a chromogenic alkaline phosphatase assay after Western Blotting.

Results

Rituximab had no apoptotic effect on both cell lines. Complement-mediated cytotoxicity was only detected in EHEB cells. mRNA and protein expressions of STAT3 and RelA genes were decreased following Rituximab treatment.

Conclusion

Our preliminary results suggest that the use of Rituximab might be effective in B-ALL though both signaling pathways.

Öz

Amaç

Rituximab, B-lenfosit yüzey antijeni CD20’yi hedefleyen bir monoklonal antikordur. B-hücre kronik lenfositik lösemi (B-KLL) gibi bazı hastalıkların tedavisinde kullanılmaktadır. Rituximab’ın lenfoma hücrelerindeki etkisi ile ilgili birçok veri vardır. Ancak, lösemi hücrelerindeki sinyal yolaklarına etkisi ile ilgili yeterli bilgi bulunmamaktadır. Bu çalışmada, Rituximab’ ın, B-hücre akut lenfoblastik lösemi (B-ALL) ve B-KLL’deki JAK-STAT ve NF-κB sinyal yolakları üzerindeki etkisinin anlaşılması hedeflenmiştir.

Gereç ve Yöntem

Rituximab’ ın TANOUE (B-ALL) ve EHEB (B-KLL) hücre hatlarındaki apoptotik etkisi Annexin V yöntemi ile belirlendi. STAT3 ve RelA’nın mRNA ekspresyon seviyeleri kantitatif RT-PCR (Q-PCR) ile analiz edildi. STAT3 ve RelA protein ekspresyonlarındaki değişimler Western Blot sonrası kromojenik alkalen fosfataz analizi ile tespit edildi.

Bulgular

Rituximab’ın her iki hücre hattında apoptotik etkisi bulunmamaktadır. Kompleman-aracılı sitotoksisite sadece EHEB hücre hattında saptanmıştır. Rituximab uygulaması sonrası STAT3 ve RelA’nın mRNA ve protein ekspresyonları azalmıştır.

Sonuç

İlk sonuçlarımız, Rituximab kullanımının B-ALL’ de her iki sinyal yolağı aracılığıyla etkili olabileceğini düşündürmektedir.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common malignancy in children under the age of 15 and occurs as a result of various genetic mutations in differentiating progenitor blood cells in the T- and B-lymphocyte pathways. These gained mutations usually cause cells to multiply unrestrictedly and block stage-based cell development [1], [2], [3]. Ultimately, immature B- or T-lymphocyte clones accumulate in the bone marrow and normal hematopoietic processes get suppressed [2]. Meanwhile, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common type of leukemia observed in adults with the average age of 65–68 [4], [5], [6]. CLL is mainly characterized by constant accumulation of CD5+ B-lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs like spleen; as well as in peripheral blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes. Therefore, its most common clinical feature is increased lymphocyte count in circulating blood [4], [6].

Signaling pathways are responsible for the communication and interaction between cells for maintaining their normal cell function; e.g. hematopoiesis normally takes place under circumstances of serial strictly controlled signaling pathways where cytokines and receptors play important roles. Irregularities in those signaling pathways usually result in malignant transformations, reduced apoptosis and continuous cell proliferation [7]. In hematologic malignancies often components of the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways are overexpressed, which can be suppressed with specific inhibitors [7], [8]. Because of this, those pathways constitute preferable drug targets in the treatment of leukemia.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins (STATs), consisting of seven family members (STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b and STAT6), are transcription factors that upon activation via phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues play important roles in various biological processes like cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, fetal development, transformation, inflammation and immune response [7], [9]. Some studies have shown that unphosphorylated STAT1 and STAT3 can also stimulate gene expression. Ligand-dependent amplification of unphosphorylated-STAT (U-STAT) leads to activation of genes other than those that are activated by phosphorylated-STAT (P-STAT); for instance, while U-STAT1 causes constant expression of LMP2 with IRF1; U-STAT3 interacts with NF-κB [10], [11].

Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) is present in all cell types and responsible for the regulation of various genes taking part in different cellular processes. NF-κB is not a single protein, but instead constitutes a small family of inducible transcription factors functioning in almost all cells [12]. The family consists of five members; namely, NF-κB1 (p50/p105), NF-κB2 (p52/p100), RelA, RelB and c-Rel; and become active by forming various heterodimers [12], [13].

The STAT3 protein and NF-κB signaling pathway are crucial players in human diseases due to their central role in inflammation and cancer. During carcinogenesis they maintain control over the expression of numerous genes alone or in concert. This depends on the STAT3 and NF-κB binding sites on gene regulatory regions. Whereas certain genes only bear NF-κB binding sites and thus are controlled by this pathway; others have both, STAT3 and NF-κB binding sites and therefore function under the control of both pathways [14]. Especially, the NF-κB family member RelA was found to interact with STAT3. This interaction might cause a specific transcriptional synergy, or may result in suppression of genes regulated by STAT3/NF-κB [14], [15].

The preferred option for treating leukemia is chemotherapy; alongside, immunotherapy, blood and bone marrow transplantations. Recently, the treatment of leukemia with monoclonal antibodies has also come into the spotlight. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets the B-lymphocyte surface antigen CD20, was approved by the FDA in 1997. Rituximab exhibits its anti-cancer effect via complement-dependent cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, and induction of apoptosis. Rituximab is currently used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and rheumatoid arthritis with FDA approval. It is also used; off-label in treatments of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease, graft-versus host disease, pemphigus vulgaris, chronic immune mediated thrombocytopenia and Evans syndrome [16]. Since sole use of Rituximab entails only limited clinical activity, medication is usually applied in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents; where Rituximab sustains sensitivity towards these chemotherapeutic agents and increases total apoptotic levels [17], [18]. Contemporarily, Rituximab is used together with Fludarabine and Cyclophosphamide in the treatment of B-CLL [19]. Up to this point favorable effect of Rituximab has been achieved in mature B-ALL cases, young patients with CD20+ B-precursor ALL and adults with CD20+ B-precursor ALL [20], [21]. It is known that CD20 is expressed in precursor B-cell (pre-B) ALL and almost all cases of mature or Burkitt-type ALL (B-ALL) [20], [22]. However prognostic significance of CD20 expression is still a subject of debate. While a high CD20 expression level has been correlated with poor therapeutic outcome in some studies, it could not been identified as a prognostic marker in other studies. Interestingly, upregulation of CD20 expression with corticosteroids before delivering Rituximab was effective in the treatment of children with B-cell precursor ALL with low CD20 expression [20], [22], [23], [24].

In light of these facts, the objective of our study was to evaluate the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of Rituximab on B-ALL and B-CLL cells via the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways. At the end, our goal was to examine whether Rituximab can function as a potential adjuvant therapeutic agent in the treatment of childhood B-ALL via the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human B-ALL (TANOUE) and B-CLL (EHEB) cell lines, which are known to express CD20, were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganism and Cell Cultures (DSMZ GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Biological Industries, Israel) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2.

Reagents

Rituximab (10 mg/mL) was provided kindly by Dr. Güray Saydam (Izmir, Turkey). β-Actin (13E5) and NF-κB p65 (C22B4) rabbit monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Denver, MA, USA). STAT3 (Ab-727) and STAT3 (Phospho-Ser727) rabbit polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Signalway Antibody (Baltimore, MD, USA). Stock solution of human complement proteins were prepared by adding 4 mL of 5% trisodium citrate solution and 120 μL of heparin (5000 unit/mL) onto 20 mL of human serum and stored at −20°C.

Cytotoxicity and complement-mediated cytotoxicity (CDC) assays

Cytotoxic effects of Rituximab and Rituximab+human complement proteins on cells were determined by using the MTT assay (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). TANOUE (3×104 cells/well) and EHEB (5×104 cells/well) cells were plated in 96-well plates in the absence or presence of different Rituximab concentrations (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 μg/mL) and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. In order to measure the living cells percentage 20 μL of MTT labeling reagent was added and incubated for 4 h. After incubation, 100 μL of solubilization solution was added and incubated overnight. The plates were measured by using a fluorimeter (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) with excitation and emission wavelength at 550 nm and at 690 nm, respectively. For the CDC assay all steps were repeated; but, additionally human complement proteins were added at a final concentration of 25% again in the absence or presence of different Rituximab concentrations (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 μg/mL). Following 24 h of incubation the percentage of living cells was assessed according to the MTT kit procedure.

Evaluation of apoptosis triggered by Rituximab

TANOUE and EHEB cells (5×105 cells/well) were treated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Apoptosis was evaluated by using the Annexin V-EGFP Apoptosis Detection kit (Biovision Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA). This method is based on the recognition of phosphatidylserine on the plasma membrane via Annexin V-EGFP and identification of living, necrotic and early stage apoptotic cells upon plasma membrane changes. TANOUE and EHEB cells were stained with Annexin V-EGFP and PI solution and apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometric analysis (BD Accuri C6 Flow Cytometry, Becton–Dickinson, Brea, CA, USA) according to the kit procedure.

Assessment of STAT3 and RelA mRNA expression levels by Q-PCR

For the evaluation of STAT3 (NM_003150) and RelA (NM_021975) mRNA expression levels by Q-PCR the TANOUE and EHEB cells (1×106 cells/well) were treated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. First, total RNA was isolated by using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated RNAs were reverse transcribed into cDNAs by using the Transcriptor High Fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Q-PCR was performed with gene specific primers and probes (TIB MOLBIOL GmbH, Berlin, Germany) using the LightCycler Fast Start DNA Master HybProbes Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and the LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) was used as a housekeeping gene in all PCR reactions. Fold-changes of expression levels were calculated by the formula 2−(ΔCt test-ΔCt control).

Gene expression array

For the analysis of mRNA expression of genes that are controlled by the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways, 17 genes were selected according to the recent literature and were evaluated with the LightCycler 480 Instrument after Rituximab (20 μg/mL) treatment for 3, 6 and 12 h (Table 1) [15]. For this assay the Real-Time Ready Custom Panel 96 kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was preferred.

Genes studied in expression array.

| Function | Genes |

|---|---|

| Proliferation – survival | BCL-XL, IL1B, Cyclin D1, Survivin, MYC, Hsp90, Hsp70, HIF1α |

| Angiogenesis | HIF1α, VEGF, bFGF, CXCL10, IL8, ICAM1, COX-2 |

| Immunosuppression | CD86, CD80, IL6, VEGF, CXCL10 |

| Inflammation | IL1B, IL8, COX-2, ICAM1 |

BCL-XL, B-cell lymphoma-2-like 1; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; COX-2, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2; CXCL10, CXC-chemokine ligand 10; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; ICAM1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IL1B, interleukin 1 beta; MYC, v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Determination of STAT3 and RelA protein expression levels by Western Blot

TANOUE and EHEB cells (3×106 cells) were treated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) and incubated at 37°C for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Protein extraction from cells was performed according to the Proteojet Mammalian Cell Lysis Reagent (Fermentas) instructions. Protein concentrations were quantified by the Bradford method (Coomassie (Bradford) Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) by using bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards ranging between 125 μg/mL and 2000 μg/mL concentrations. Equal amounts of protein (25–30 μg) were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes by using a wet transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). STAT3, p-STAT3, RelA and β-Actin primary antibodies were 1:1000 diluted. Protein levels of target genes were detected by using the WesternBreeze® Chromogenic Western Blot Immunodetection Kit (Invitrogen, Carlbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and results were evaluated with a gel imaging system (Vilber Lourmat GmbH, Eberhardzell, Germany).

Statistical analysis

All assays were set up in triplicates. Gene expression analyses were performed with the ΔΔCT method. Fold changes were analyzed according to the differences between the control and study groups for each time point. One way ANOVA and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test were used to test the significance among these groups. SPSS for Windows, Version 15.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and Image J were used for analysis. If the p-value was p<0.05, then the results were considered statistically significant.

Results

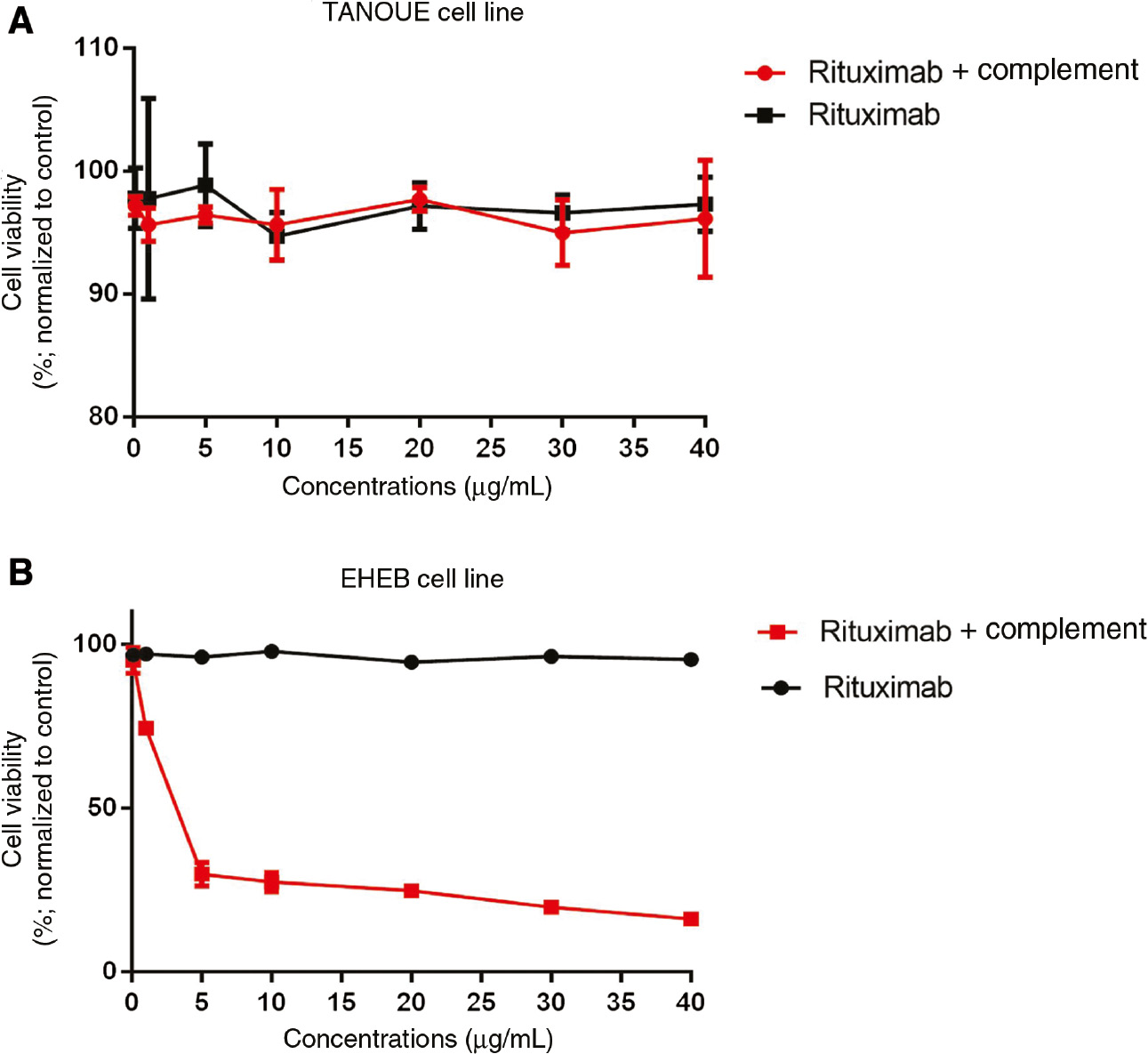

Cytotoxic effect

Previous findings have shown that the application of Rituximab alone has no cytotoxic effects on most cells analyzed so far. In order to confirm this finding, TANOUE and EHEB cell lines were treated with different concentrations of Rituximab for 24 h. MTT assay results revealed that Rituximab had no cytotoxic effects on both cell lines (p=0.760 for TANOUE cell line, p=0.154 for EHEB cell line). To test if it will have cytotoxic effect in the presence of complement proteins, TANOUE and EHEB cell lines were again treated with different concentrations of Rituximab, but this time, they were used in the CDC assays together with 25% human serum for 24 h. This treatment only had a cytotoxic effect on EHEB cells with an IC50 value of 1.32 μg/mL (p<0.001) (p=0.984 for TANOUE cell line) (Figure 1A and B).

Cytotoxic activity of Rituximab in (A) TANOUE and (B) EHEB cell lines.

The indicated cell lines were incubated for 24 h in the presence of different Rituximab concentrations (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 μg/mL) (black line) or Rituximab+complement proteins (25%) (red line). Cytotoxicity was assessed by the MTT assay. Assays were set up in triplicates. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 15.0 software was used for analysis. One way ANOVA was used to test the significance among these groups. Error bars indicate standart deviations of measurements. p<0.05 was considered as significant.

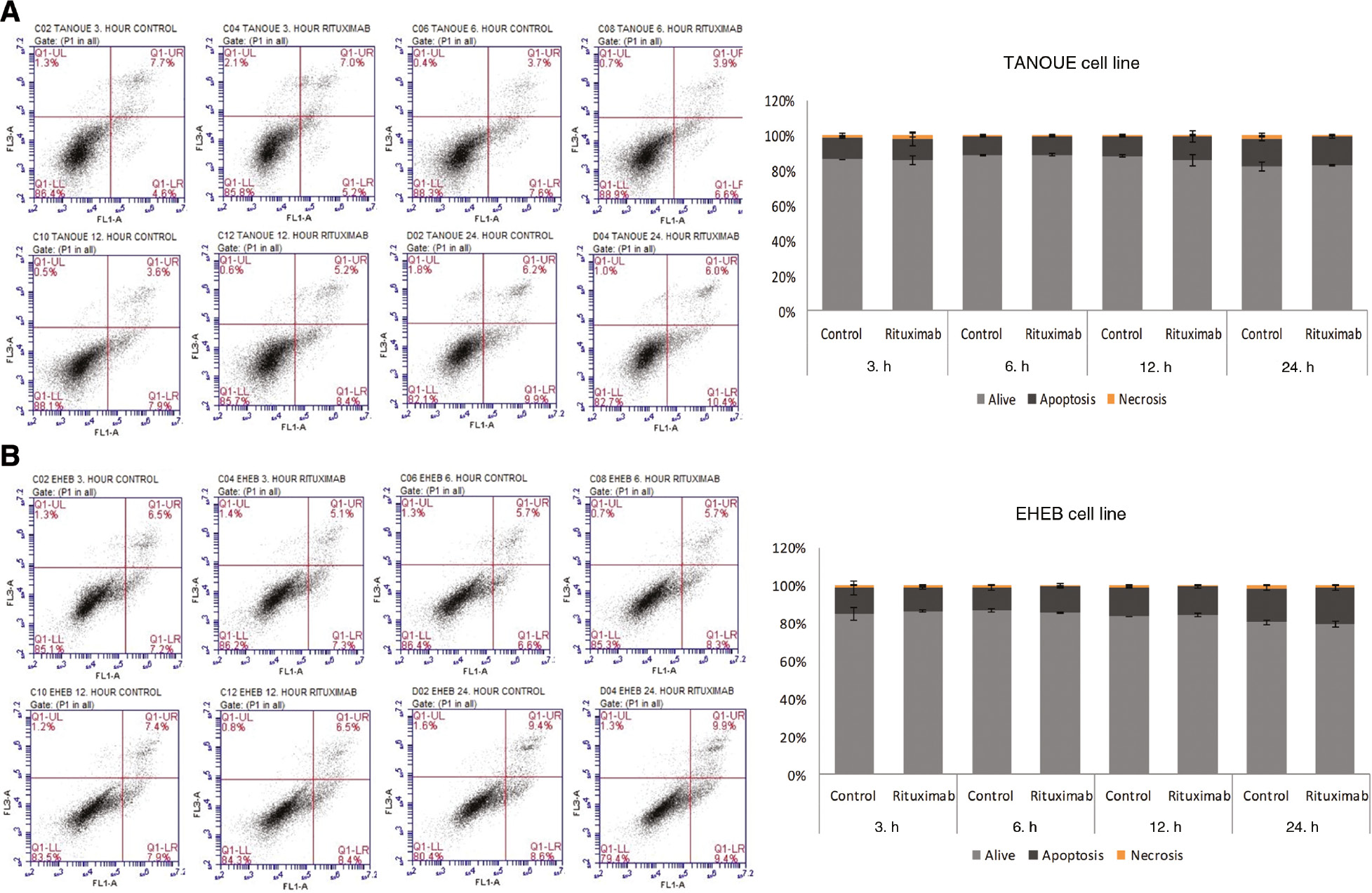

Apoptotic effect

Since Rituximab had no cytotoxic effect on both cell lines IC50 values could not be determined. Therefore, a treatment dose of 20 μg/mL was chosen for all the following assays according to similar studies performed by different investigators [25], [26]. For the evaluation of the apoptotic cell rate, TANOUE and EHEB cell lines were treated with 20 μg/mL of Rituximab for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Compared to the untreated control group, in the study group no apoptotic effects could be detected in both cell lines at each time point (p=0.677 for TANOUE cell line, p=0.061 for EHEB cell line) (Figure 2A and B).

Apoptotic effects of Rituximab in (A) TANOUE and (B) EHEB cell lines.

The indicated cell lines were incubated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h and assessed by flow cytometric analysis (flow cytometry images). Assays were set up in triplicates. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 15.0 software was used for analysis. One way ANOVA was used to test the significance among these groups. Error bars indicate standart deviations of measurements. p<0.05 was considered as significant.

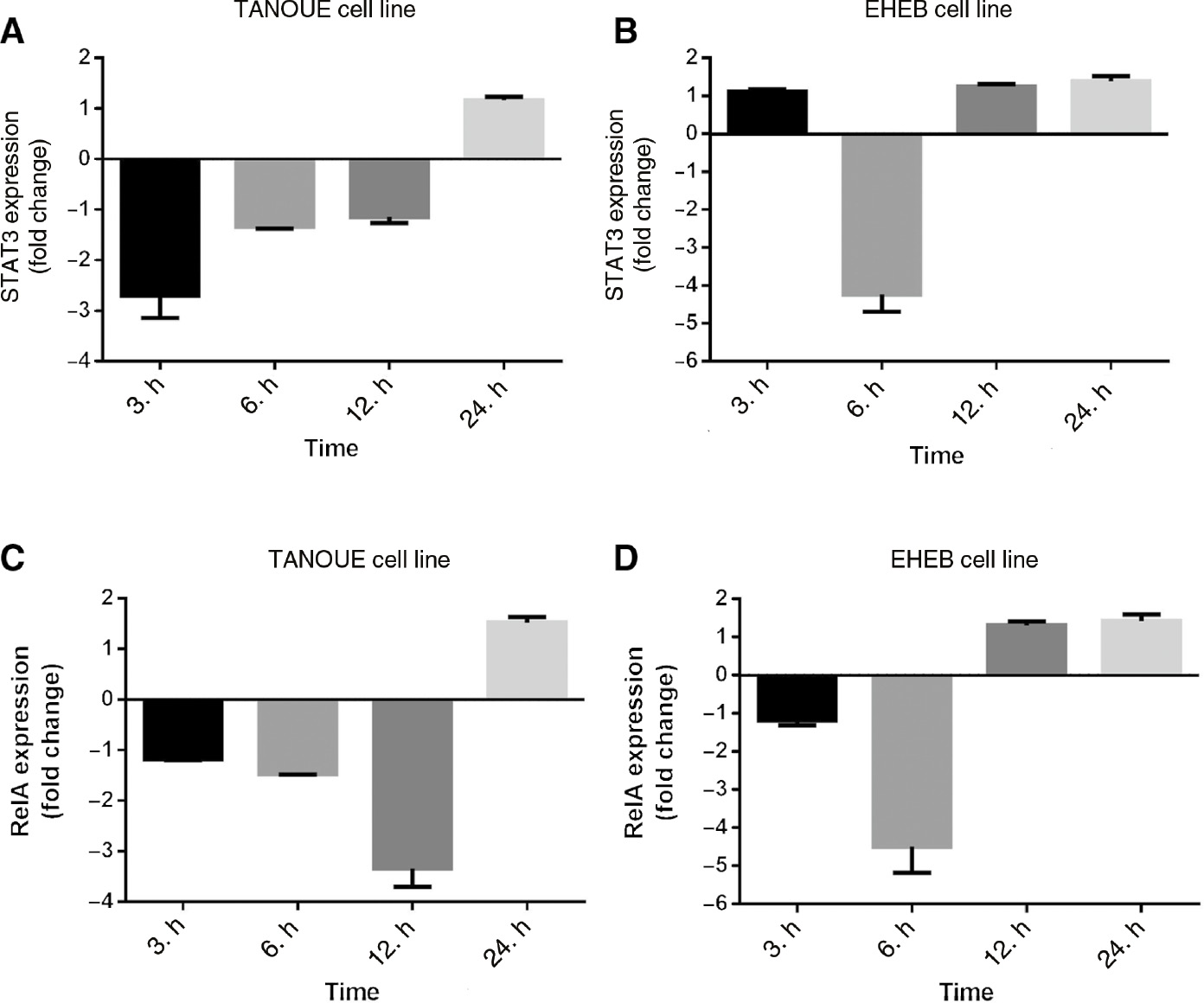

Reduced STAT3 and RelA gene expressions

Fold changes of STAT3 and RelA gene expressions were analyzed by comparing Rituximab treated study and untreated control group cells at each time point. The analysis showed that STAT3 and RelA mRNA expressions decreased in Rituximab treated study group cells at different time points. For STAT3 expression this was mainly by 2.7-fold (p<0.001) after 3 h and 4.2-fold (p<0.001) after 6 h in TANOUE and EHEB cells, respectively (Figure 3A and B). And for RelA expression this was mainly by 3.34-fold (p<0.001) after 12 h and 4.5-fold (p<0.001) after 6 h in TANOUE and EHEB cells, respectively (Figure 3C and D).

Gene expression analysis of STAT3 and RelA.

STAT3 expression in (A) TANOUE and (B) EHEB cell lines. RelA expression in (C) TANOUE and (D) EHEB cell lines. The indicated cell lines were incubated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Q-PCR results were quantified by the 2ΔΔCT method using GAPDH as reference gene. Fold changes were analyzed according to the differences between the control and study groups for each time point. Assays were set up in triplicates. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 15.0 software was used for analysis. One way ANOVA was used to test the significance among these groups. Error bars indicate standart deviations of measurements. p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Expressional changes of genes controlled by JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways

Expressional changes of genes controlled by JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways were analyzed after 3, 6 and 12 h by comparing Rituximab treated study and untreated control group cells. In Rituximab treated TANOUE cells, Survivin gene expression decreased by 1.76-fold (p=0.017) after 6 h and ICAM1 gene expression by 2.29-fold (p=0.000012) after 12 h (Table 2). Besides, expressional changes of 6 genes (IL1B, COX-2, bFGF, CyclinD1, IL6, IL8) could not be detected. Whereas, in Rituximab treated EHEB cells COX-2 and MYC gene expressions decreased by 1.5-fold (p=0.0076) and 1.61-fold (p=0.00022) after 3 h, respectively; and, ICAM1, Cyclin D1 and Survivin gene expressions by 9.3-fold (p=0.028), 1.67-fold (p=0.046) and 1.54-fold (p=0.028) after 6 h, respectively (Table 3).

Expressional changes of genes controlled by the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in TANOUE cell line.

| 3 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | p-Value | Fold change | p-Value | Fold change | p-Value | |

| BCL-XL | −1.3899 | 0.17521 | 1.1647 | 0.319554 | −1.6606 | 0.098751 |

| ICAM1 | −1.0413 | 0.918776 | −1.0693 | 0.662694 | −2.2947 | 0.000012 |

| CD86 | −1.1134 | 0.512588 | 1.1121 | 0.515294 | −1.8856 | 0.084855 |

| HIF1α | 1.1394 | 0.545411 | −1.3597 | 0.101159 | −1.2016 | 0.297589 |

| CD80 | 1.0461 | 0.753878 | −1.2834 | 0.133308 | 1.2879 | 0.11804 |

| VEGF | −1.0012 | 0.990438 | −1.0668 | 0.221411 | −1.5351 | 0.076653 |

| Survivin | 1.244 | 0.145514 | −1.7613 | 0.017952 | −1.1715 | 0.464083 |

| HSP90 | −1.0012 | 0.984725 | −1 | 0.95854 | −1.3899 | 0.116369 |

| MYC | −1.1715 | 0.293767 | −1.0792 | 0.163052 | −1.6189 | 0.113554 |

| Hsp70 | 1.2498 | 0.303805 | 1.014 | 0.797922 | −1.129 | 0.241629 |

| CXCL10 | 1.0461 | 0.753878 | −1.2834 | 0.133308 | 1.2879 | 0.09804 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant data.

Expressional changes of genes controlled by the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in EHEB cell line.

| 3 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | p-Value | Fold change | p-Value | Fold change | p-Value | |

| BCL-XL | −1.1715 | 0.134175 | −1.7552 | 0.077796 | 1.1329 | 0.209191 |

| IL1B | 1.0128 | 0.813781 | −1.244 | 0.130065 | 1 | 0.988527 |

| ICAM1 | 1.1264 | 0.130617 | −9.3071 | 0.028758 | −1.1096 | 0.263622 |

| CD86 | 1.1134 | 0.22077 | 1.129 | 0.414154 | 1.1434 | 0.16653 |

| COX-2 | −1.5245 | 0.007634 | −1.2212 | 0.497506 | −1.1045 | 0.451303 |

| HIF1α | −1.1006 | 0.495415 | −1.2527 | 0.086771 | 1.1755 | 0.107889 |

| CD80 | 1.093 | 0.542975 | −1.0175 | 0.796479 | 1.154 | 0.069533 |

| VEGF | 1.2672 | 0.106468 | −1.3119 | 0.304777 | 1.0968 | 0.25308 |

| bFGF | 1.1006 | 0.572221 | 1.2383 | 0.277447 | 1.1096 | 0.077226 |

| Cyclin D1 | 1.078 | 0.644123 | −1.676 | 0.046048 | −1.0449 | 0.655816 |

| IL6 | 1.3645 | 0.145574 | −1.0151 | 0.977065 | −1.2426 | 0.17719 |

| Survivin | 1.9119 | 0.120374 | −1.5494 | 0.028266 | 1.1355 | 0.056553 |

| HSP90 | −1.3272 | 0.243154 | 1.0558 | 0.611601 | 1.0842 | 0.389714 |

| MYC | −1.6189 | 0.000229 | 1.1634 | 0.135853 | −1.2599 | 0.231583 |

| Hsp70 | 1.078 | 0.475208 | 1.1906 | 0.107688 | 1.0693 | 0.121439 |

| CXCL10 | 1.0151 | 0.751064 | 1.2184 | 0.181247 | 1.2198 | 0.249845 |

| IL8 | −1.1006 | 0.896119 | 1.073 | 0.506359 | 1.1865 | 0.380069 |

Bold values indicate statistically significant data.

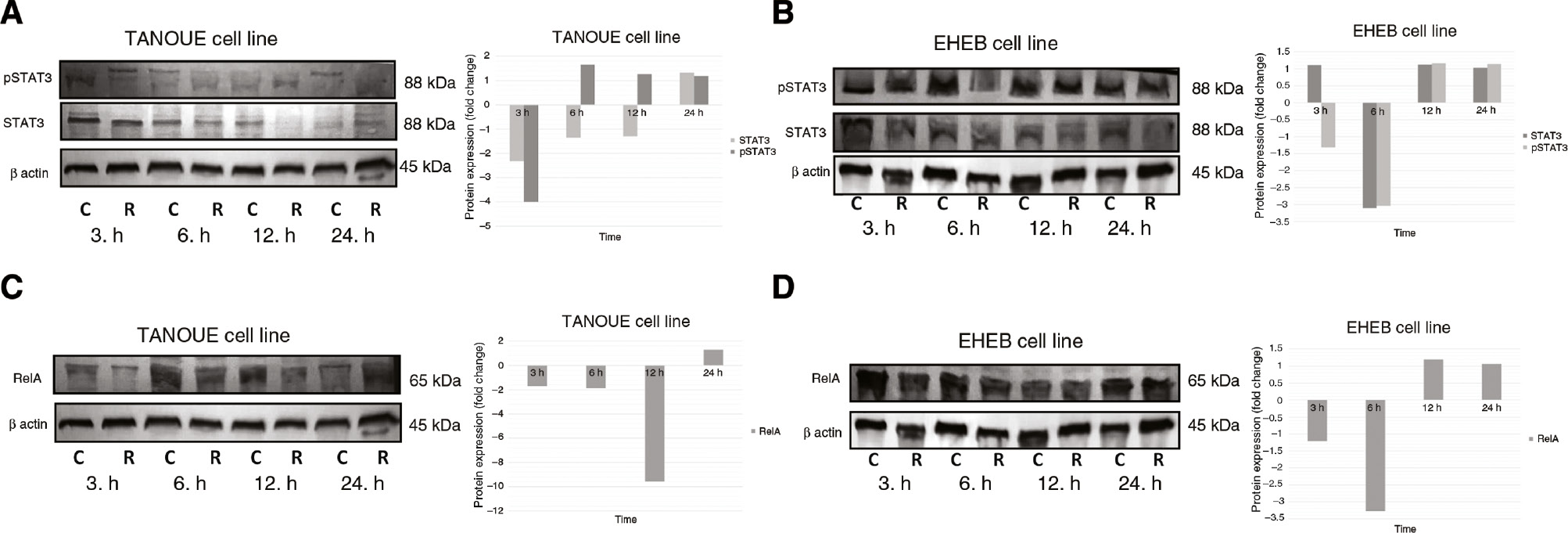

Reduced STAT3 and RelA protein expressions

For revealing changes in STAT3 and RelA protein expressions, Rituximab treated study and untreated control group cells were analyzed at each time point. The analysis showed that total STAT3 protein expression decreased after 3 (2.32-fold), 6 (1.36-fold) and 12 (1.30-fold) h in Rituximab treated TANOUE cells; and, p-STAT3 protein expression decreased only after 3 h (4.01-fold, p=0.027). Fold changes of STAT3 protein expression in TANOUE cells between 3rd and 6th h were found statistically significant (p=0.028) (p=0.462 between 6th and 12th h) (Figure 4A). At the same time, total STAT3 protein expression decreased in Rituximab treated EHEB cells only after 6 h (3.10-fold, p=0.028); but, p-STAT3 protein expression especially decreased after 3 (1.32-fold) and 6 (3.04-fold) h (p=0.026) (Figure 4B). It also showed that RelA protein expression decreased after 3 (1.7-fold), 6 (1.88-fold) and 12 (9.57-fold) h in Rituximab treated TANOUE cells (Figure 4C); and, after 3 (1.21-fold) and 6 (3.27-fold) h in Rituximab treated EHEB cells (p=0.028) (Figure 4D). Fold changes of RelA protein expression in TANOUE cells between 6th and 12th h were found statistically significant (p=0.027) (p=0.116 between 3rd and 6th h).

Protein expression analysis of STAT3 and RelA.

STAT3 protein expression in (A) TANOUE and (B) EHEB cell lines. RelA protein expression in (C) TANOUE cell line and (D) EHEB cell lines. The indicated cell lines were incubated with Rituximab (20 μg/mL) for 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. Proteins (25–30 μg) were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Protein levels were detected by using the chromogenic alkaline phosphatase assay. Fold changes were analyzed according to the differences between the control and study groups for each time point. Assays were set up in triplicates. Image J and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 15.0 software were used for analysis. Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was used to test the significance among these groups. p<0.05 was considered as significant. C: control group; R: Rituximab treated study group.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether Rituximab might be function as an adjuvant chemotherapeutic agent according its effects on STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Briefly, we did not detect any cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of Rituximab on both cell lines. Besides that, we determined decreasing gene expression and protein levels of STAT3 and RelA at different time points after treatment with Rituximab.

In the first phase of this study, cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of Rituximab on TANOUE and EHEB cells were excluded by testing it in different concentrations. The obtained results of the present study are in accordance with the results of other studies, since Rituximab should not have any cytotoxic effects due to its antibody structure. Thus, we have validated other studies. Furthermore, we determined that low Rituximab concentrations together with complement proteins of the immune system were cytotoxic to EHEB cells; but not to TANOUE cells. The later finding in CD20+ TANOUE cells therefore requires further attention in future studies. Because, in studies that were carried out with different cell lines the general impression was that although Rituximab has no cytotoxic effect in its own, cytotoxicity can be induced when using it together with complement proteins or other agents. For instance, in studies carried out with lymphoma cell lines, Rituximab only revealed cytotoxicity when combined with different agents like Artesunat, Fludarabine, Vincristine, Doxorubisine, Idarubisine, Cisplatine, and Taxol [26], [27], [28], [29]. Besides, Rituximab is known to induce apoptosis at a low rate. Eventually, no increase in apoptotic cell level could be detected after Rituximab treatment in TANOUE and EHEB cells. But, on the other hand, this result is in concordance with the lack cytotoxicity in this cell lines. In the case where complement proteins were added to Rituximab treated EHEB cells, cell death occured due to necrosis rather than by apoptosis (preliminary data). It has been shown by various in vitro and in vivo studies that Rituximab actually sensitizes malignant cells towards the cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of agents like Doxorubicine, Cisplatine, Dexamethasone and Fludarabine; hence forming a synergy with the agent used [30]. Rituximab alone does not induce apoptosis to a significant degree; but, when used in combination with Artesunat, Paclitaxel, Cisplatine, or suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) it significantly increases apoptotic levels in dose-dependent manner [28], [31], [32], [33], [34].

In the second phase of our study, alterations in the expressions of STAT3 and RelA, which are crucial players of the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways, respectively, were investigated upon Rituximab treatment. It is well known that both of these genes are often overexpressed in malignant cells. Therefore, a decrease in their expression levels would be significant in respect to the agent used for the treatment of these malignant cells, as it also was the case in this study. STAT3 gene expression decreased by 2.7-fold in TANOUE cells after 3 h and by 4.2-fold in EHEB cells after 6 h of treatment with Rituximab. Although, a decrease of STAT3 gene expression could be detected at the other times points, it was not found statistically significant. Total STAT protein levels also decreased in TANOUE cells after 3, 6 and 12 h and in EHEB cells after 6 h. On the other hand, in accordance with the gene expression results, p-STAT3 protein levels decreased in TANOUE cells after 3 h and in EHEB cells after 3 and 6 h. It is known that the p-STAT3 level is an indicator of JAK-STAT signaling pathway activation. Therefore, decrease of the p-STAT3 levels can be interpreted as suppression of this signaling pathway. Other studies have shown that upon treatment with Rituximab STAT3 expression gets suppressed and also its ability to bind to DNA is inhibited in lymphoma cell lines [26], [35]. Another studies also showed that Rituximab only decreases pSTAT3 levels, which gets even more effective when used in combination with SAHA and Quercetin [34], [36].

In the present study, we demonstrated that RelA gene expression decreased in TANOUE cells by 3.34-fold after 12 h and in EHEB cells by 4.5-fold after 6 h of treatment with Rituximab. Similarly, RelA protein levels decreased after 3, 6, and 12 h in TANOUE cells and after 3 and 6 h in EHEB cells. Studies with lymphoma cell lines have shown that DNA binding activity and phosphorylation of the NF-κB family members RelA, IκB and IKK decrease following Rituximab treatment [33], [34], [35], [37].

The cease in decrease of STAT3 and RelA expressions after 24 h can be explained by the fact that the duration of maximum Rituximab activity is 24 h. There are some studies related with the half-life of Rituximab. Studies performed mostly with samples from B-cell lymphoma patients have shown that the half-life of Rituximab varies across patients, gender and body weight. In addition, it was also determined that the half-life of Rituximab prolongs due to the increased number of infusions [38], [39], [40], [41]. Although there are different time points for half-life of Rituximab in recent literature, when differences between in vivo/in vitro conditions and leukemia/lymphoma cells characteristics are considered, it could be supposed that Rituximab has short half-life. On the other hand, taken altogether, a decrease in STAT3 and RelA overexpressions in cases with leukemia would also mean a decrease in expressions of genes that are associated with leukemogenesis and are controlled by the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Since this is the case like in this study, it can be argued that Rituximab is effectively performing in B-ALL and B-CLL treatment.

Finally, alterations in the expressions of genes that are controlled by the JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways and which are implicated in cell proliferation, angiogenesis and inflammation were examined after Rituximab treatment. A decrease in Survivin and ICAM-1 expressions was detected in both cell lines; whereas, a decrease of COX-2, MYC and Cyclin D1 expressions was only detected in EHEB cells. Among these results the most striking decrease in expression was that of ICAM-1 by 2.29-fold in TANOUE cells after 12 h and by 9.3-fold in EHEB cells after 6 h of treatment with Rituximab. ICAM-1 is an adhesion molecule that is expressed in lymphocytes and endothelial cells when stimulated by cytokines. Leukocyte adhesion and migration, inflammatory processes, tumor cell invasion and metastasis are possible outcomes when leukocyte adhesion molecules bind to CD18 family members, lymphocyte function associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) and macrophage-1 antigen (MAC-1) [42]. High levels of ICAM-1 expression in cases with CLL and Hodgkin lymphoma are known to be related to poor disease prognosis [43], [44]. Consequently, a decrease in ICAM-1 overexpression in a variety of cancer diseases has been regarded as an important factor in the prevention of metastasis. There is not much known about the effects of Rituximab on ICAM1 expression for different cell lines. In one of these rare studies, it has been shown that Rituximab stimulates the polarization of CD20, ICAM-1, myosin and the microtubule organization center (MTOC) in B-cells; and, that the polarized cells concomitantly are sorted out and killed by effector natural killer (NK) and NK cells which recognize these B-cells through their CD20 antigen covered regions [45]. Although, the present study also refers to the expressional decrease of the anti-apoptotic MYC, Survivin, Cyclin D1 and COX-2 genes; actually, no increase of the apoptotic level could be detected after Rituximab treatment and therefore was interpreted as not sufficient enough to induce apoptosis. However, we claimed that Rituximab sensitize cells for apoptosis which had to be induced by different mechanisms. Nevertheless, the decrease in Cyclin D1 expression by Rituximab proves its efficiency in reducing cell proliferation.

In conclusion, although any significant apoptosis rate could not be detected, a decrease in STAT3 and RelA gene and protein expressions may indicate that Rituximab is effective in B-ALL and B-CLL treatment via JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Because of the importance of JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in leukemogenesis, obtained preliminary results might be useful for further researches.

Acknowledgement

We would like thank to Prof. Cumhur Gündüz, Prof. Mehmet Korkmaz, Assoc. Prof. Özlem Dalmızrak and Dr. Çağdaş Aktan for technical support; and, to Dr. Hasan Onur Çağlar for the great help in creating the figures of this manuscript. This work originated from a thesis of Ayşegül Dalmızrak and was supported by the Ege University Medical School Scientific Research Project (APAK 2011-TIP-027). This study has been presented in Ege Hematoloji Onkoloji Kongresi as poster.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Lancet 2008;371:1030–43.10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2Search in Google Scholar

2. Graux C. Biology of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): clinical and therapeutic relevance. Transfus Apher Sci 2011;44:183–9.10.1016/j.transci.2011.01.009Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Zuckerman T, Rowe JM. Pathogenesis and prognostication in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. F1000Prime Rep 2014;6:59.10.12703/P6-59Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Ghia P, Ferreri AM, Caligaris-Cappio F. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;64:234–46.10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.04.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Tausch E, Mertens D, Stilgenbauer S. Advances in treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia. F1000Prime Rep 2014;6:65.10.12703/P6-65Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2015 Update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol 2015;90:446–60.10.1002/ajh.23979Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Benekli M, Baumann H, Wetzler M. Targeting signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway in leukemias. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4422–32.10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3264Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Packham G. The role of NF-kappaB in lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol 2008;143:3–15.10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07284.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Benekli M, Baer MR, Baumann H, Wetzler M. Signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins in leukemias. Blood 2003;101:2940–54.10.1182/blood-2002-04-1204Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev 2007;21:1396–408.10.1101/gad.1553707Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Yang J, Stark GR. Roles of unphosphorylated STATs in signaling. Cell Res 2008;18:443–51.10.1038/cr.2008.41Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Jost PJ, Ruland J. Aberrant NF-kappaB signaling in lymphoma: mechanisms, consequences, and therapeutic implications. Blood 2007;109:2700–7.10.1182/blood-2006-07-025809Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Lindström TM, Bennett PR. The role of nuclear factor kappa B in human labour. Reproduction 2005;130:569–81.10.1530/rep.1.00197Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2010;21:11–9.10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9:798–809.10.1038/nrc2734Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Selewski DT, Shah GV, Mody RJ, Rajdev PA, Mukherji SK. Rituximab (Rituxan). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:1178–80.10.3174/ajnr.A2142Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. James DF, Kipps TJ. Rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Adv Ther 2011;28:534–54.10.1007/s12325-011-0032-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Bezombes C, Fournie JJ, Laurent G. Direct effect of rituximab in B-cell-derived lymphoid neoplasias: mechanism, regulation, and perspectives. Mol Cancer Res 2011;9:1435–42.10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0154Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Tedeschi A, Vismara E, Ricci F, Morra E, Montillo M. The spectrum of use of rituximab in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Onco Targets Ther 2010;3:227–46.10.2147/OTT.S8151Search in Google Scholar

20. Hoelzer D, Gökbuget N. Chemoimmunotherapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Rev 2012;26:25–32.10.1016/j.blre.2011.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Maury S, Chevret S, Thomas X, Heim D, Leguay T, Huguet F, et al. Rituximab in B-lineage adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1044–53.10.1056/NEJMoa1605085Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Kantarjian H, Thomas D, Wayne AS, O’Brien S. Monoclonal antibody-based therapies: a new dawn in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3876–83.10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6768Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Borowitz MJ, Shuster J, Carroll AJ, Nash M, Look AT, Camitta B, et al. Prognostic significance of fluorescence intensity of surface marker expression in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Blood 1997;89:3960–6.10.1182/blood.V89.11.3960Search in Google Scholar

24. Kamazani FM, Bahoush-Mehdiabadi G, Aghaeipour M, Vaeli S, Amirghofran Z. The expression and prognostic impact of CD95 death receptor and CD20, CD34 and CD44 differentiation markers in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Iran J Pediatr 2014;24:371–80.Search in Google Scholar

25. Berinstein NL, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, Bence-Bruckler I, Maloney D, Czuczman M, et al. Association of serum Rituximab (IDEC-C2B8) concentration and anti-tumor response in the treatment of recurrent low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 1998;9:995–1001.10.1023/A:1008416911099Search in Google Scholar

26. Alas S, Bonavida B. Rituximab inactivates signal transducer and activation of transcription 3 (STAT3) activity in B-non-hodgkin’s lymphoma through inhibition of the interleukin 10 autocrine/paracrine loop and results in down-regulation of Bcl-2 and sensitization to cytotoxic drugs. Cancer Res 2001;61:5137–44.Search in Google Scholar

27. Dı Gaetano N, Xıao Y, Erba E, Bassan R, Rambaldi A, Golay J, et al. Synergism between fludarabine and rituximab revealed in a follicular lymphoma cell line resistant to the cytotoxic activity of either drug alone. Br J Haematol 2001;114:800–9.10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03014.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Sieber S, Gdynia G, Roth W, Bonavida B, Efferth T. Combination treatment of malignant B cells using the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab and the anti-malarial artesunate. Int J Oncol 2009;35:149–58.10.3892/ijo_00000323Search in Google Scholar

29. Koivula S, Valo E, Raunio A, Hautaniemi S, Leppa S. Rituximab regulates signaling pathways and alters gene expression associated with cell death and survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncol Rep 2011;25:1183–90.10.3892/or.2011.1179Search in Google Scholar

30. Cartron G, Watier H, Golay J, Solal-Celigny P. From the bench to the bedside: ways to improve rituximab efficacy. Blood 2004;104:2635–42.10.1182/blood-2004-03-1110Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Alas S, Ng CP, Bonavida B. Rituximab modifies the cisplatin-mitochondrial signaling pathway, resulting in apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:836–45.Search in Google Scholar

32. Jazirehi AR, Vega MI, Chatterjee D, Goodglick L, Bonavida B. Inhibition of the Raf–MEK1/2–ERK1/2 signaling pathway, Bcl-xL down-regulation, and chemosensitization of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma B cells by Rituximab. Cancer Res 2004;64:7117–26.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3500Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Jazirehi AR, Huerta-Yepez S, Cheng G, Bonavida B. Rituximab (chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) inhibits the constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma B-cell lines: role in sensitization to chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res 2005;65:264–76.10.1158/0008-5472.264.65.1Search in Google Scholar

34. Shi W, Han X, Yao J, Yang J, Shi Y. Combined effect of histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab on mantle cell lymphoma cells apoptosis. Leuk Res 2012;36:749–55.10.1016/j.leukres.2012.01.027Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Vega MI, Huerta-Yepaz S, Garban H, Jazirehi A, Emmanouilides C, Bonavida B. Rituximab inhibits p38 MAPK activity in 2F7 B NHL and decreases IL-10 transcription: pivotal role of p38 MAPK in drug resistance. Oncogene 2004;23:3530–40.10.1038/sj.onc.1207336Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Li X, Wang X, Zhang M, Li A, Sun Z, Yu Q. Quercetin potentiates the antitumor activity of rituximab in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by inhibiting STAT3 pathway. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014;70:1357–62.10.1007/s12013-014-0064-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Vega MI, Huerta-Yepaz S, Jazirehi AR, Garban H, Bonavida B. Rituximab (chimeric anti-CD20) sensitizes B-NHL cell lines to Fas-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 2005;24:8114–27.10.1038/sj.onc.1208954Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Keating MJ, O’Brien S, Albitar M, Lerner S, Plunkett W, Giles F, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4079–88.10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Pescovitz MD. Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody: history and mechanism of action. Am J Transplant 2006;6(5 Pt 1):859–66.10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01288.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Müller C, Murawski N, Wiesen MH, Held G, Poeschel V, Zeynalova S, et al. The role of sex and weight on rituximab clearance and serum elimination half-life in elderly patients with DLBCL. Blood 2012;119:3276–84.10.1182/blood-2011-09-380949Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Counsilman CE, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Stevens J, Cransberg K, Bredius RG, Sukhai RN. Pharmacokinetics of rituximab in a pediatric patient with therapy-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2015;30:1367–70.10.1007/s00467-015-3120-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Boyd AW, Wawryk SO, Burns GF, Fecondo JV. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) has a central role in cell-cell contact-mediated immune mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:3095–9.10.1073/pnas.85.9.3095Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Christiansen I, Gidlöf C, Wallgren AC, Simonsson B, Tötterman TH. Serum levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are increased in chronic B-lymphocyte leukemia and correlate with clinical stage and prognostic markers. Blood 1994;84:3010–6.10.1182/blood.V84.9.3010.3010Search in Google Scholar

44. Terol MJ, Tormo M, Martinez-Climent JA, Marugan I, Benet I, Ferrandez A, et al. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (s-ICAM-1/s-CD54) in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: association with clinical characteristics and outcome. Ann Oncol 2003;14:467–74.10.1093/annonc/mdg057Search in Google Scholar PubMed

45. Rudnicka D, Oszmiana A, Finch DK, Strickland I, Schofield DJ, Lowe DC, et al. Rituximab causes a polarization of B cells that augments its therapeutic function in NK-cell–mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Blood 2013;121:4694–702.10.1182/blood-2013-02-482570Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Investigating the impact of polysomy 17 in breast cancer patients with HER2 amplification through meta-analysis

- Diagnostic performance of microRNAs in the circulation in differential diagnosis of BPH, chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer

- Enhanced anticancer effect of cetuximab combined with stabilized silver ion solution in EGFR-positive lung cancer cells

- CA125, YKL-40, HE-4 and Mesothelin: a new serum biomarker combination in discrimination of benign and malign epithelial ovarian tumor

- Paricalcitol pretreatment attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting p38 MAPK and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathways

- Identification of cytoplasmic sialidase NEU2-associated proteins by LC-MS/MS

- Investigation of tyrosinase inhibition by some 1,2,4 triazole derivative compounds: in vitro and in silico mechanisms

- Investigation of alanine, propionylcarnitine (C3) and 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels in patients with partial biotinidase deficiency

- The expression levels of miR-655-3p, miR127-5p, miR-369-3p, miR-544a in gastric cancer

- Evaluation of the JAK2 V617F gene mutation in myeloproliferative neoplasms cases: a one-center study from Eastern Anatolia

- Effects of Rituximab on JAK-STAT and NF-κB signaling pathways in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Analysis of the effect of DEK overexpression on the survival and proliferation of bone marrow stromal cells

- Serum fetuin-A levels and association with hematological parameters in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis patients

- Investigation of relaxation times in 5-fluorouracil and human serum albumin mixtures

- Oxydative stress markers and cytokine levels in rosuvastatin-medicated hypercholesterolemia patients

- The protective effects of urapidil on lung tissue after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury

- Effects of SR-BI rs5888 and rs4238001 variations on hypertension

- Antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of three Turkish marine-derived fungi

- Is spectrophotometric enzymatic method a cost-effective alternative to indirect Ion Selective Electrode based method to measure electrolytes in small clinical laboratories?

- Plasma presepsin in determining gastric leaks following bariatric surgery