Abstract

The increasing need for agricultural commodities poses a serious threat to the cultivating ability of agricultural supplies. The use of autonomous farming drones to support the cultivation process is a rapidly growing trend. In an effort to improve efficiency and accuracy in watering using drones, this research strived to propose a control design for the drones using the multiclass support vector machine (MSVM) method. The proposed system was an improvement compared to the common approach of using constant watering strength in all drone conditions. By obtaining suitable watering strength based on the drone’s altitude, wind speed, and speed sensor data as the input, the optimal solution between water usage and water efficiency was expected to be achieved. An experimental trial that consisted of 12 flights was conducted to acquire a data set with 3,750 data. The results of classification with MSVM obtained an accuracy of 90.82%. The efficiency of using the water resource and the accuracy of delivering the correct amount of water based on the drone condition were achieved. These results show that the proposed technology has great potential for using drones as an automatic watering system in agriculture.

1 Introduction

Agriculture is an important sector in the Indonesian economy, where most of the population depends on agricultural products for their livelihood [1]. Population growth in Indonesia has now reached 278.69 million people by mid-2023; this figure is up 1.05% from the previous year [2]. Thus, there will be an increase in the need for food supply and land to cultivate agricultural products. The prevalence of insufficiency in Indonesia’s food consumption in 2022 has a value of 10.21% or an increase of 1.72% from the previous year [3]. Moreover, the rate of conversion of agricultural land to other uses continues to increase, and opportunities to expand the area on conventional agricultural land are considered very limited [4]. Increased consumption of fertilizers and pesticides accompanied by intensification of agricultural activities may lead to future environmental challenges [5,6].

In recent years, the agricultural industry has seen a significant shift toward autonomous farming practices, driven by advancements in technology such as drones and artificial intelligence (AI). One critical aspect of autonomous farming is efficient and precise pesticide application to optimize crop yield while minimizing environmental impact. Traditional spraying methods often lack precision and can lead to the overuse of chemicals, resulting in increased costs and potential harm to the environment. To address these challenges, researchers are increasingly turning to intelligent sprayer control systems that utilize machine learning algorithms to accurately target areas in need of treatment. So an innovative approach based on modern technology is needed, which can increase production efficiency and affordable food quality, improve environmental sustainability, and improve the welfare of farmers and the sectors that support it [7,8]. Drones, also referred to as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), are devices that can fly with a predetermined path on autopilot and GPS coordinates [9]. UAVs have undergone great development in recent decades. In the agricultural sector, drones have changed agricultural practices by providing significant cost savings, increased operational efficiency, and better profits for farmers. Over the past few decades, the topic of agricultural drones has attracted significant academic attention [5].

Traditional methods used for spraying pesticides and fertilizers take longer and are less effective [10]. So spraying using drones is applied in the field which increases coverage capabilities, increases the effectiveness of chemicals, and makes spraying work easier and faster [11,12]. However, in the application of the sprayer system on drones, determining the intensity of spraying becomes an important variable in providing efficient spraying results. A commonly used method is to classify drone altitude, wind speed, and speed data to determine watering strength [13]. The accuracy of the classification varies for each method used, so it is necessary to choose the right method for the nature of the dataset to be used.

Research on UAVs in agricultural contexts has been done before. One of them, UAVs are used to map land suitable for agriculture [14]. Where this mapping is done using image recognition which is then processed using machine learning random forest (RF) and deep learning convolutional neural network (CNN). As a result, the RF method provides accuracy (≈85%) and CNN (≈90%) [15]. The use of drones allows for more efficient and flexible mapping compared to traditional methods. Then, another study also implemented a UAV with an AI-based sprayer system to measure liquid droplet deposition to eradicate pests on plants. The results showed that the artificial neural networks training variation was 0.003, so the model was stable and reliable. Field tests show that the error between predicted droplet deposition and actual droplet deposition is less than 20% [16]. These studies indicate the potential of AI to improve accuracy [17,18,19,20]. However, it should be noted that the use of AI in the study above requires complex sensors to obtain and process data. So a method is needed that can use common devices but with different processing.

Research using a drone sprayer that controls the water pump through the use of Arduino UNO and is connected directly to the pump motor is commonly carried out. The PIXHAWK flight controller provides data in the form of coordinates obtained from sensing in the field, and the Arduino UNO processes the data to determine the right time to activate the pump motor. However, by using only Arduino UNO, it is not possible to regulate the intensity of the flow of sprayed water [21]. Results from previous studies have shown that the use of drones in the agricultural sector can improve the efficiency and accuracy of watering crops. However, currently controlling the intensity of watering still cannot be done dynamically, resulting in a waste of resources. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a watering control system that is able to adapt dynamically. Machine learning methods are often used in data processing as feedback for watering systems [22,23]. However, the use of machine learning today still relies heavily on complex sensors such as cameras, so there are limitations between hardware and software.

As the global population continues to grow, there is an urgent need to enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability. Autonomous farming technologies, such as drones equipped with intelligent sprayer control systems, hold great promise in meeting this demand. However, to realize their full potential, these systems must be optimized for accuracy, efficiency, and adaptability. To overcome the bottleneck, a more efficient and practical watering control method is proposed by using only existing sensors in the form of altitude, wind speed, and drone speed sensors to determine the strength of watering. By utilizing data from these sensors, the watering control system can be set adaptively and dynamically, without relying on the limitations of complex sensors. The proposed method for processing such data is multiclass support vector machine (MSVM). By using MSVM, watering control can be done dynamically and adaptively based on data generated by existing sensors. MSVM can learn patterns and relationships from collected data to predict optimal watering needs. This enables saving water resources, reducing wastage, and increasing efficiency in the agricultural sector. The development of a reliable MSVM-based intelligent sprayer control for autonomous farming drones represents a critical step toward achieving these goals. Urgent research in this area is essential to accelerate the deployment of advanced agricultural technologies, mitigate environmental risks, and ensure food security for future generations.

This manuscript is organized as follows. First, the hardware used in constructing the smart sprayer system is presented. Then, the method to find the optimal solution of sprayer strength, MSVM, is elaborated. Furthermore, the implementation results are presented, emphasizing the obtained accuracy of the proposed method in determining the actuator setting for the sprayer system. The correlation among the inputs is first presented, followed by the final classification of the actuator setting by using MSVM. The manuscript is finalized with a conclusion.

2 Methods

This study was conducted at the Field of Basic Science Service Center, Padjadjaran University. Field trials involved creating an illustration resembling agricultural land. Data were collected from 12 drone flight tests, encompassing 4 distinct trajectory types and 3 altitudes. Throughout the test flights, five variables were gathered: altitude, wind speed, drone velocity, latitude, and longitude.

2.1 Smart sprayer system hardware

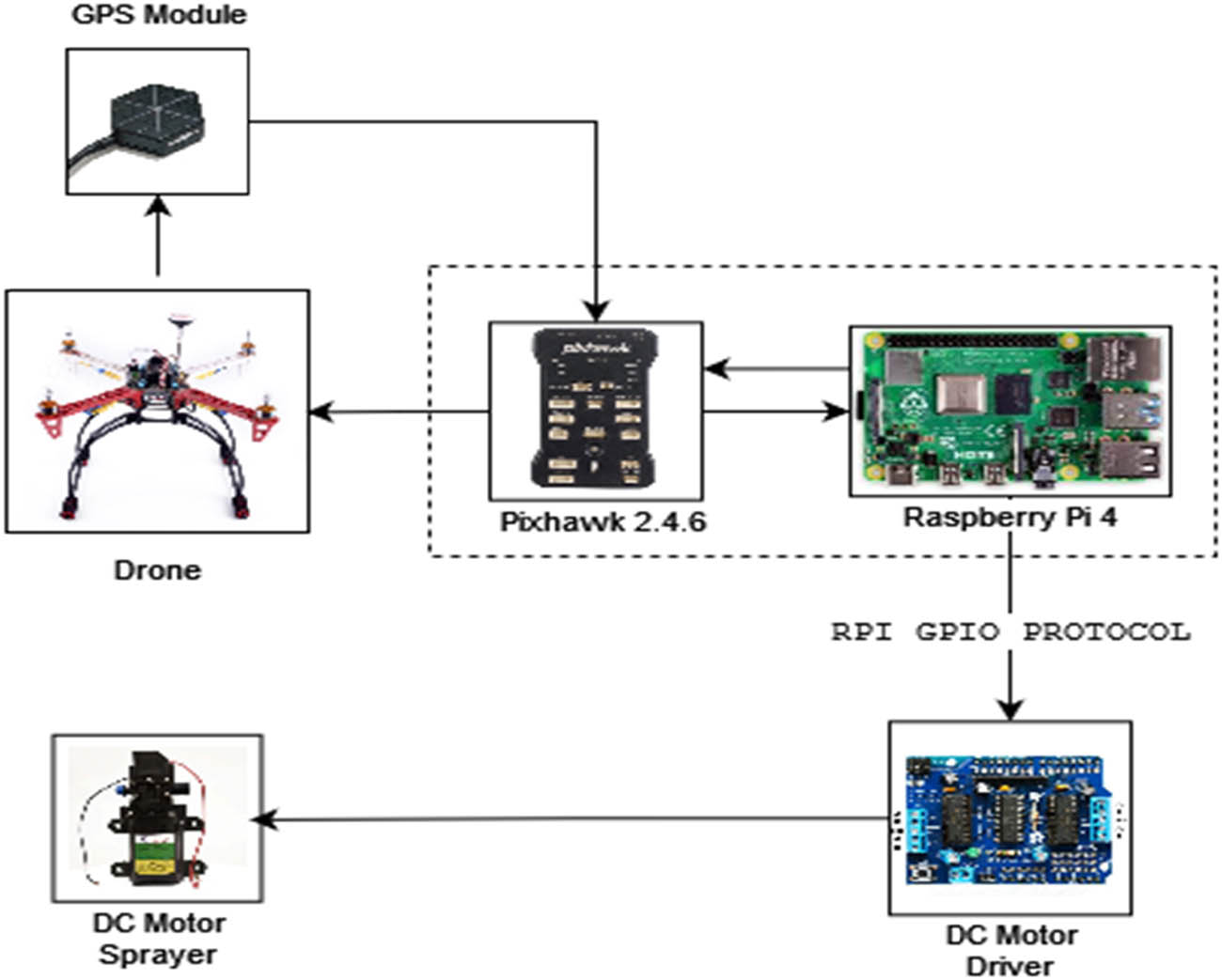

In this study, drones were equipped with an F450 frame and operated using the Pixhawk 2.4.6 Flight Controller, responsible for managing flight and landing operations. To track the drone’s location during flight, a GPS Module Radiolink M8N SE100 was installed onboard. The Raspberry Pi 4 served as the microcontroller, executing Python applications remotely. Additionally, DC motors were utilized for the watering system. The Pixhawk stored crucial flight data such as altitude, drone position, and waypoints. Calibration and configuration of the drones were facilitated through the Mission Planner application, which enabled users to define flight paths and waypoints. Figure 1 illustrates the hardware block diagram.

Intelligent sprayer system on autonomous drone hardware block diagram. Source: Own creation.

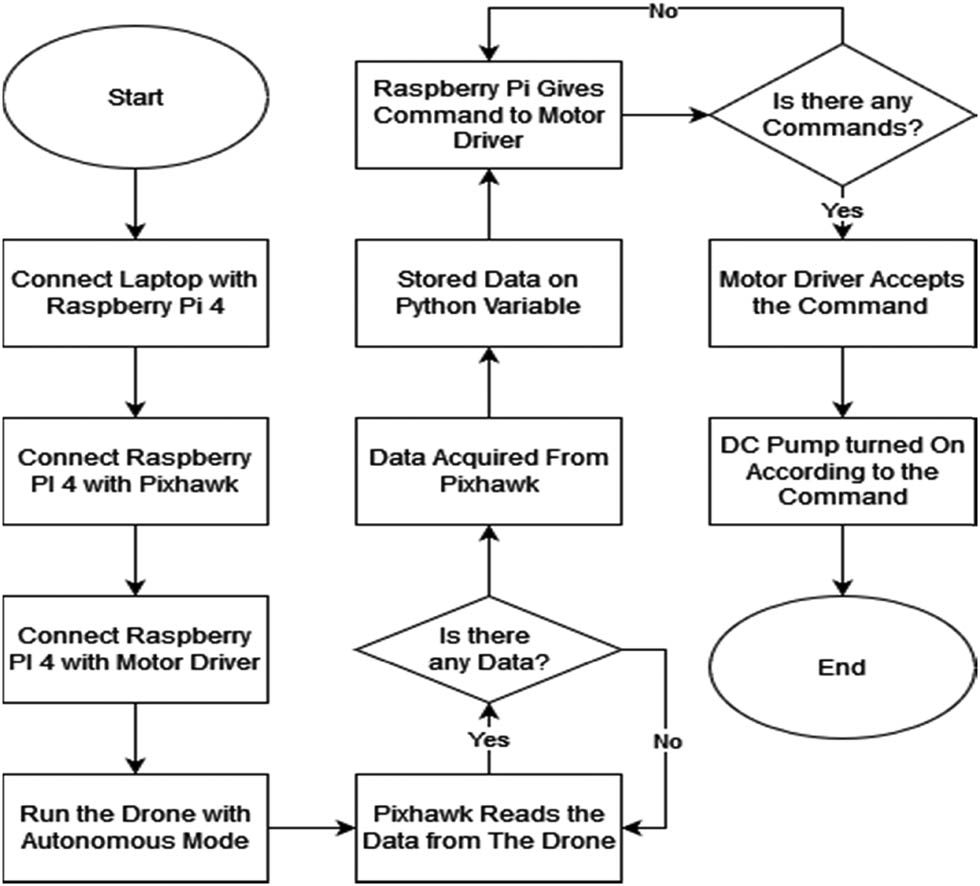

Communication between the flight controller and microcontroller occurred via telemetry and the Micro Air Vehicle Link (Mavlink) protocol, allowing the Raspberry Pi to receive diverse drone data from the Pixhawk. Furthermore, the Raspberry Pi controlled the watering system’s power through the DC motor driver. Communication between the Raspberry Pi and the motor leveraged the RPI GPIO communication protocol, integrating the GPIO port within the Python program. Water distribution was achieved through hoses and nozzles connected to the water storage. Upon activation, water flowed through the nozzles for watering purposes. The Raspberry Pi regulated watering intensity by adjusting the voltage on the motor driver, utilizing altitude, wind speed, and drone speed measurements to control watering strength. Additionally, data regarding the drone’s waypoints influenced watering duration. Figure 2 provides an overview of the operational mechanism of the intelligent drone sprayer.

Intelligent sprayer system on autonomous drone flowchart.

2.2 MSVM: One-vs-all

The multiclass fine Gaussian support vector machine (SVM) method is a sophisticated approach employed for data classification in multiclass scenarios. This method combines SVM principles with the Gaussian kernel to generate precise classification models. Its efficacy has been demonstrated across diverse domains including pattern recognition, image processing, and bioinformatics. Essentially, SVM is a machine learning technique rooted in the concept of linear separation to categorize data. It identifies hyperplanes that optimize the separation between distinct classes within the feature space.

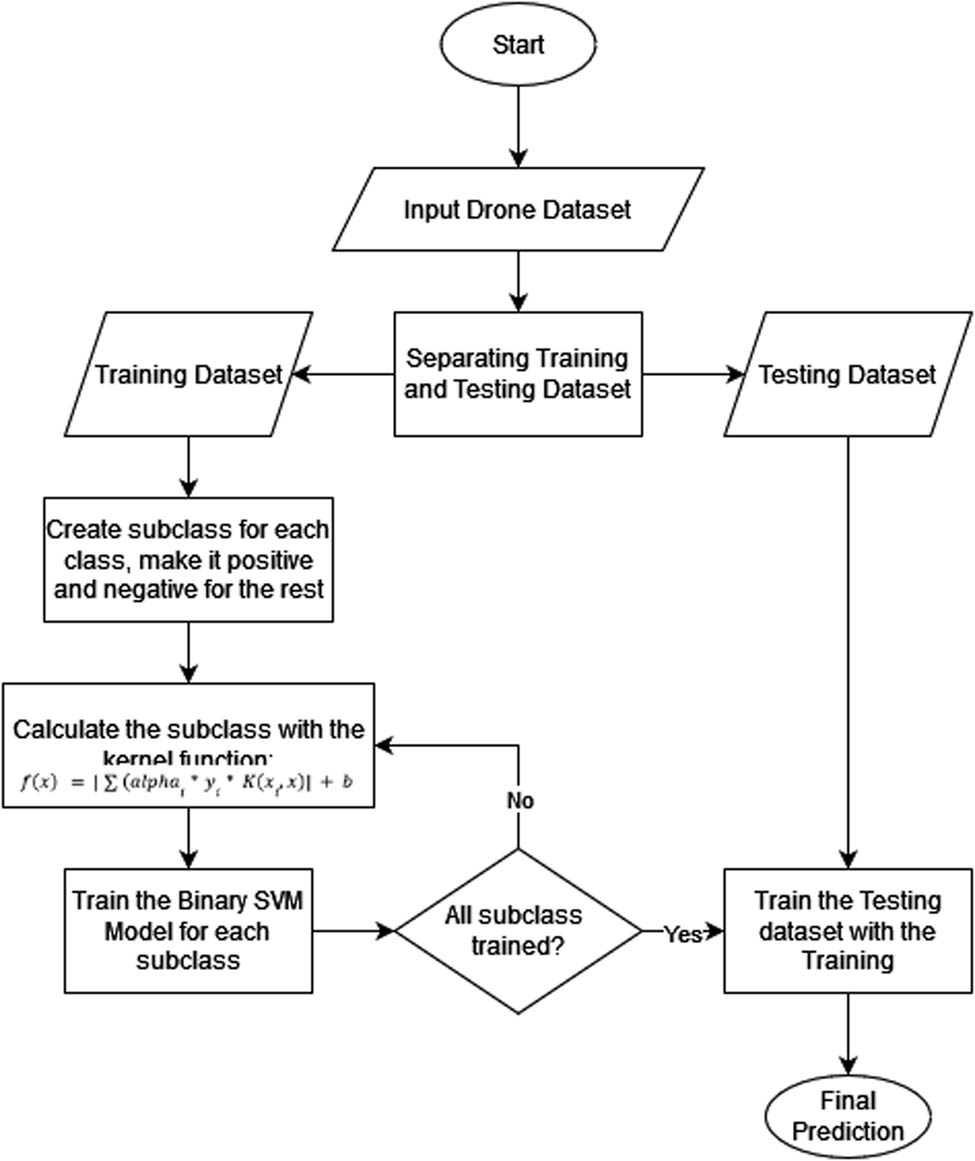

where f(x) is a decision function that classifies data x into either class (+1 or −1), x is the vector of the data feature you want to classify, w is the weight vector that is the normal vector of the hyperplane, and b is a hyperplane bias or shift. In binary SVM, we have two classes that we want to separate. However, in a multiclass problem, we have more than two classes. To solve the multiclass problem, the multiclass fine Gaussian SVM method adopts a one-vs-one or one-vs-all approach. The one-vs-one approach involves creating an SVM model for every possible pair of classes, while the one-vs-all approach involves creating an SVM model for each class against all other classes. In both approaches, each SVM model produces a decision function that classifies data into specific classes. In the one-vs-all method, multiple binary SVM models are trained by comparing each class to another. For example, if there are three classes, there will be three binary SVM models trained to classify each class against the other classes. The fine Gaussian kernel function is used to map data into higher dimensions of feature space, so SVM can better classify nonlinear data as in Figure 3.

Visualization of one-vs-all classification method (red square is class 1, blue triangle is class 2, and green circle is class 3).

Furthermore, the multiclass fine Gaussian SVM method uses the Gaussian kernel to transform data into a higher feature space. Gaussian kernels, also known as radial basis function kernels, map data into infinite-dimensional space using radial base functions. The Gaussian kernel describes the relationship between each data pair in a new feature space by using Gaussian functions. This allows SVM to handle non-linear data effectively. The function can be expressed by the following formula:

where

Mathematically, the binary SVM model in the one-vs-all approach can be defined whereby any ith class, the problem is divided into two classes: the ith class is considered a positive class (+1) and all other classes are considered a negative class (−1). Then, the binary SVM model is trained to classify the data into an ith class based on those settings (Figure 4). In SVM, the decision function for a binary SVM model can be expressed as follows:

where

MSVM algorithm.

3 Results

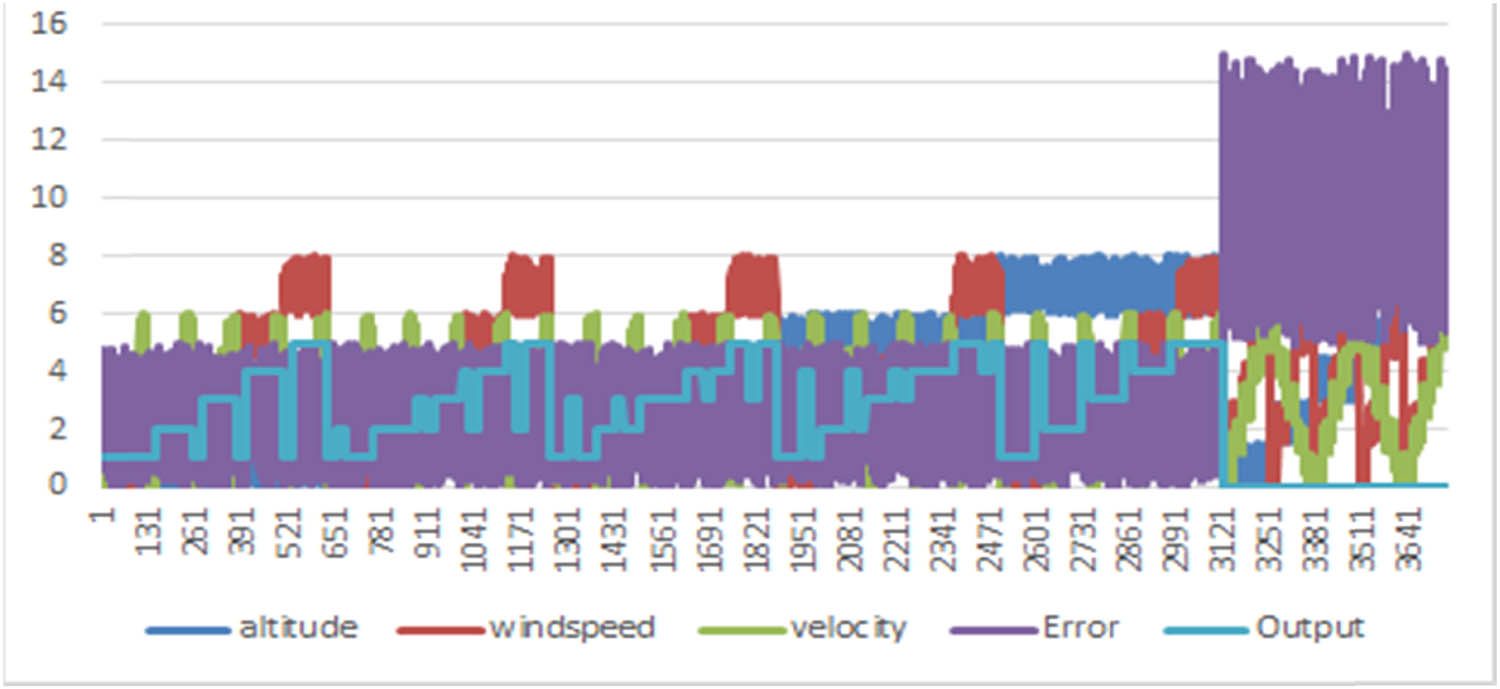

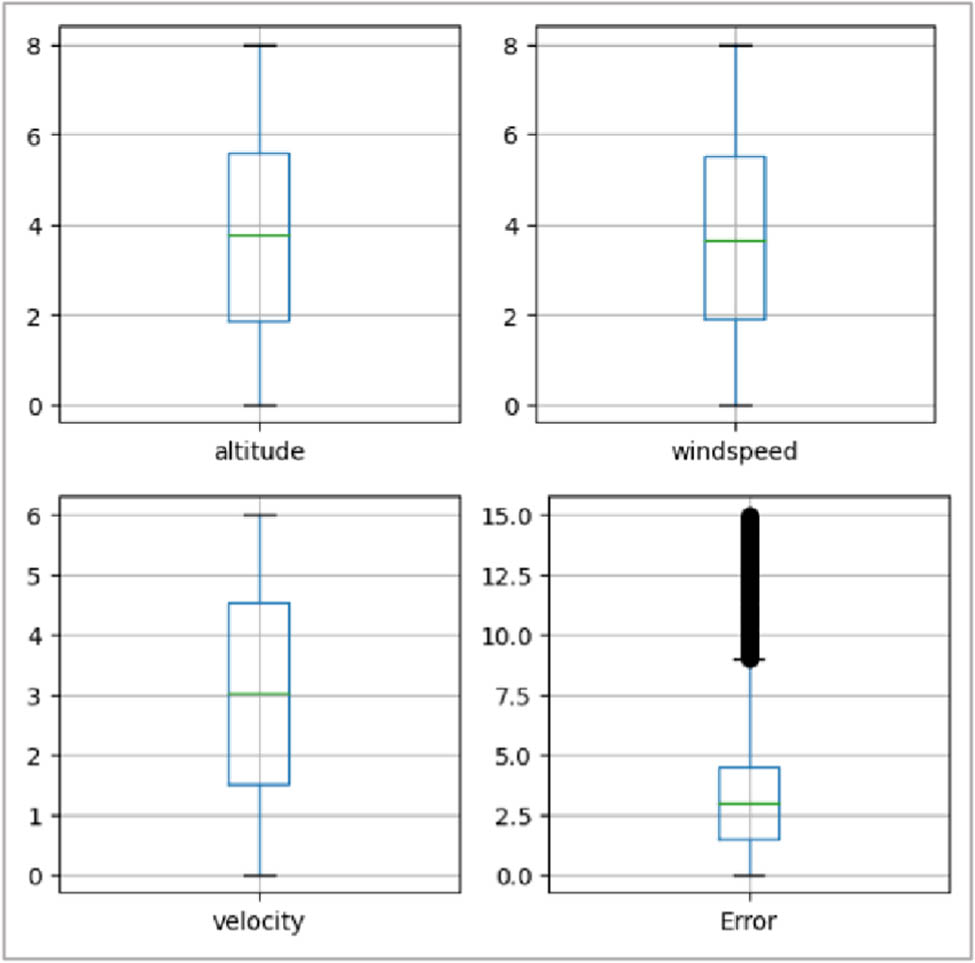

The dataset, comprising sensor measurements including altitude, wind speed, drone speed, and GPS error, consists of 3,750 entries. It is divided into 6 classes, each denoted by values 0 through 5, representing conditions ranging from “off” to “very high.” Each class contains an equal number of entries (625), ensuring data balance to prevent bias during model training. Imbalanced training data can skew the model toward classes with greater representation, leading to inaccurate predictions and reduced performance. Figure 5 illustrates the sensor measurements captured by the drone’s smart sprayer, while a detailed description of the dataset is provided in Table 1. Various methods exist for determining the classification range within a dataset. However, in this experiment, the box plot method was employed. Utilizing box plot enables visualization and adjustment of data ranges based on five statistical summaries: minimum value, first quartile, median, third quartile, and maximum value, ensuring greater accuracy in classification. The conversion of data into a box chart is presented in Figure 6, offering insight into the dataset’s distribution.

Data from sensor measurements on autonomous drones.

Description of smart spraying drone dataset

| Altitude (m) | Wind speed (m/s) | Velocity (m/s) | GPS error (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 3,750 | 3,750 | 3,750 | 3,750 |

| Mean | 3.8 | 3.73 | 3.01 | 3.74 |

| Std | 2.24 | 2.21 | 1.74 | 3.3 |

| min | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| 25% | 1.87 | 1.88 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 50% | 3.75 | 3.64 | 3.02 | 2.97 |

| 75% | 5.6 | 5.5 | 4.54 | 4.45 |

| Max | 8 | 8 | 6 | 15 |

Transforming data plot into a box chart.

Each variable in the dataset correlates with other variables. Correlations between variables can be classified into two types, namely negative correlation when the value is less than 0, and positive correlation when the value is more than 0. If the correlation value between two variables is 0, then the variables are not correlated. The level of correlation can be seen through the level of darkness or brightness on the heatmap. The correlation between these variables is shown in the heatmap in Figure 7. In the smart sprayer algorithm that will be used in this system, rules have been compiled based on a dataset that has been prepared beforehand. This dataset includes 250 different conditions that will produce an output of when the watering force will be in a predefined category, i.e., “off,” “very low,” “low,” “medium,” “high,” or “very high.” This rule aims to correlate the variables in the dataset with the appropriate watering strength category. Rules are created based on parameters such as altitude, wind speed, velocity, and GPS error. The rules are created based on the exact linguistic values or categories for each parameter. Table 2 lists the rules that relate the combination of parameter values with the desired watering strength category. These rules provide clear guidance for the smart sprayer system to determine the optimal watering strength based on the variables measured.

Correlation between variables using heatmap.

Rules for every parameter

| No | If | Altitude | And | Windspeed | And | Velocity | And | Error | Then | Watering power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Low | = | out1mf1 | |

| 2 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | High | = | out1mf2 | |

| 3 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Low | & | Low | = | out1mf3 | |

| 4 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Low | & | High | = | out1mf4 | |

| 5 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Medium | & | Low | = | out1mf5 | |

| 6 | Very_low | & | Very_low | & | Medium | & | High | = | out1mf6 | |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | |||||

| 245 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | Medium | & | Low | = | out1mf245 | |

| 246 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | Medium | & | High | = | out1mf246 | |

| 247 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | High | & | Low | = | out1mf247 | |

| 248 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | High | & | High | = | out1mf248 | |

| 249 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | Low | = | out1mf249 | |

| 250 | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | Very_high | & | High | = | out1mf250 |

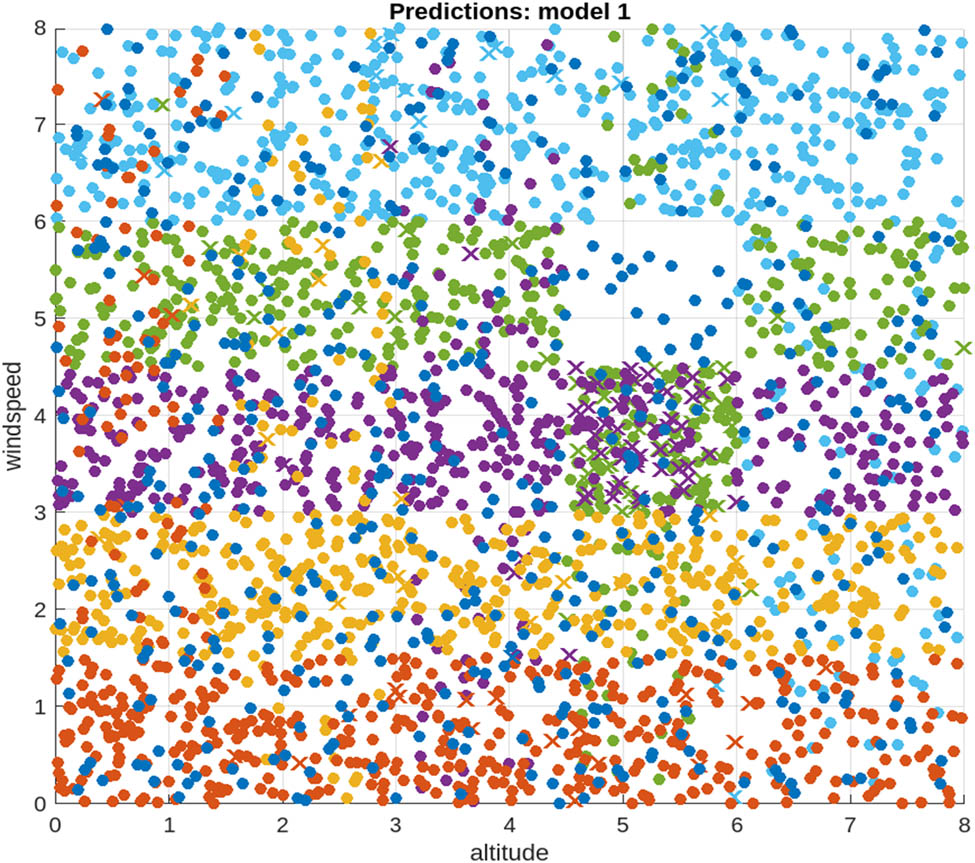

In this study, an MSVM algorithm was created to process the dataset that had been prepared. The features of the dataset as well as the prediction targets are extracted and stored in different variables. Furthermore, the data are divided into training and testing sets in an 80:20 ratio, where 80% of the data is used to train the model and 20% of the data is used to test the performance of the model. In the SVM algorithm, adjusted hyperparameters are used to achieve optimal results. One important hyperparameter is the selection of kernel functions. In this case, a fine Gaussian kernel function is used to generate an SVM model. Fine Gaussian kernel functions can help map data into higher feature spaces, allowing for better separation between existing classes. In addition, in this SVM model, a multiclass one-vs-all mode is also used which allows classifying each subset of data against other subsets. Next is a scatter plot which is a type of data visualization used to show the relationship between two numerical variables. In a scatter plot, each point is plotted on a graph that represents the value of both variables. The scatter plot in Figure 8 depicts the data before it is classified where each dot of a different color describes the six classes.

Scatter plot data after pre-processing.

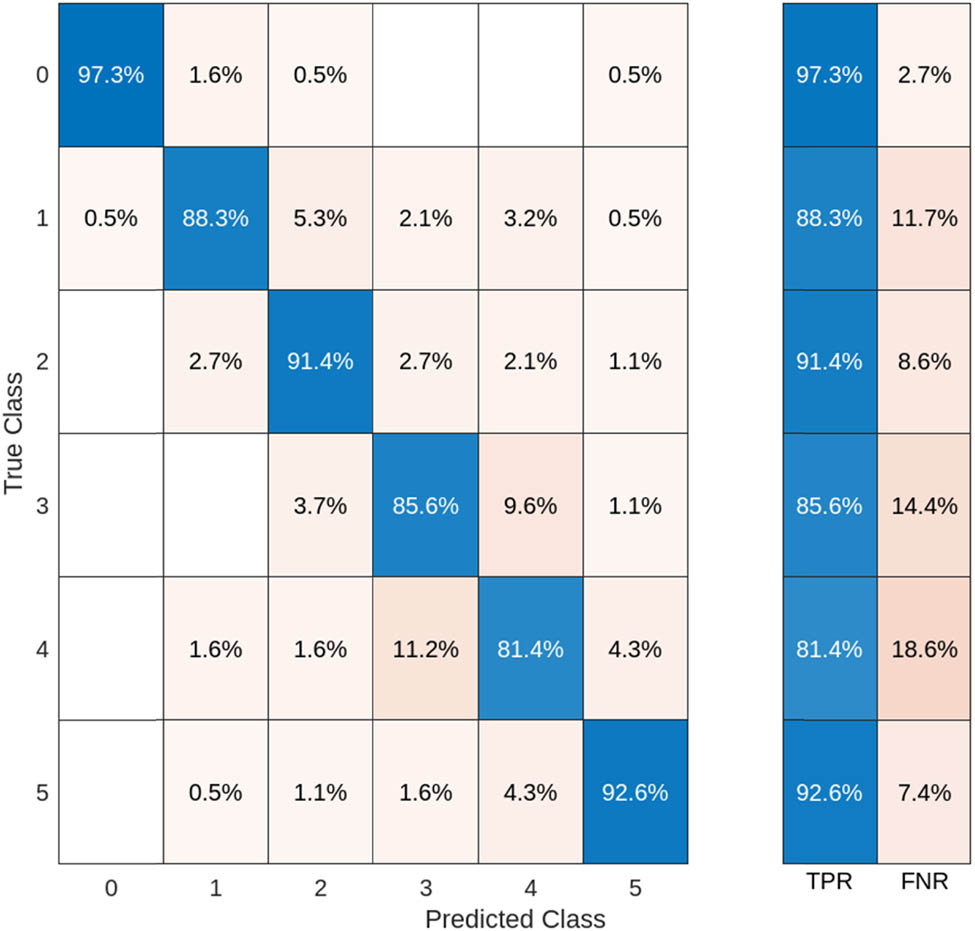

In the performance evaluation of the model, the Confusion matrix is used. This confusion matrix measures model performance using several metrics, including precision or positive predictive value, recall or true positive rate (TPR), F1 score or harmonic mean of precision and recall, support, false positive rate (FPR), and false discovery rate (FDR). Precision describes the extent to which the model can correctly predict a positive class. Recall measures the model’s ability to identify all positive samples. F1 score is a metric that combines precision (precision) and recall. Precision measures the accuracy of a model’s predictions on a positive class, while recall measures the model’s ability to identify all positive samples. F1 score provides an overall measurement of model accuracy that balances precision and recall.

Support refers to the volume of data tested within a specific class. FPR denotes the ratio of negative actual cases incorrectly identified as positive by the model. Meanwhile, FDR represents the proportion of false positive predictions to the total positive predictions made by the model. In our model, multiclass SVM exhibits an impressive accuracy of 90.82%. The comprehensive breakdown of results, including the confusion matrix (Figure 9) and other metric measurements (Table 2), offers insights into the model’s performance across various criteria. Table 2 presents a range of metrics associated with the classification model’s performance across multiple classes. Notably, overall accuracy is notably high, ranging between 95.05 and 99.83%. This suggests the model effectively categorizes instances across all classes. However, relying solely on accuracy may not provide a complete understanding, particularly with imbalanced datasets. Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions made by the model, calculated as the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false positives. Precision values range from 0.83 to 0.99, indicating generally accurate positive predictions by the model (Table 3).

The confusion matrix output of multiclass SVM.

Evaluation matrix calculation results based on confusion matrix

| Class | n (truth) | n (classified) | Accuracy (%) | Precision | Recall | F1 score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97 | 98 | 99.83 | 0.99 | 1.0 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 92 | 98 | 97.62 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| 3 | 101 | 98 | 97.11 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.91 |

| 4 | 101 | 98 | 97.11 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| 5 | 99 | 98 | 95.05 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| 6 | 98 | 98 | 97.96 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

Recall, also known as sensitivity or TPR, assesses the model’s ability to capture all relevant instances of a class. It is the ratio of true positives to the sum of true positives and false negatives. Recall values range from 0.82 to 1.0, with some classes achieving perfect recall (1.0), indicating the model’s effectiveness in identifying instances. The F1 score, a harmonic mean of precision and recall, offers a balanced measure considering both false positives and false negatives. With F1 score values ranging from 0.82 to 0.99, the model demonstrates a good balance between precision and recall across most classes. Overall, the model exhibits strong performance, characterized by high accuracy and balanced precision and recall. Notably, class 1 stands out with exceptionally high precision, recall, and F1 score, indicative of very accurate and comprehensive predictions. Although class 5 shows slightly lower precision and recall, it remains within an acceptable range. Classes 2–4 demonstrate solid overall performance with high accuracy and balanced precision and recall. Further evaluation of the model should consider the specific context of the classification problem and any unique requirements or constraints. Additionally, analyzing the confusion matrix and evaluating the potential impact of false positives and false negatives on the application can offer valuable insights for refinement and optimization.

4 Conclusion

The development of an intelligent sprayer on autonomous farming drones utilizing MSVM: one-vs-all for predicting watering forces has been successfully achieved. Through experimentation with a dataset comprising 3,750 entries divided into 6 classes of 625 entries each, a comprehensive analysis of metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score has been conducted. The findings indicate that the multiclass SVM model exhibits strong performance in classifying instances across diverse classes, with overall accuracy ranging impressively from 95.05 to 99.83%. However, acknowledging the limitations of accuracy, particularly in imbalanced datasets, the examination of precision, recall, and F1 score provides a nuanced evaluation of the model’s efficacy. Precision values ranging from 0.83 to 0.99 underscore the model’s accuracy in predicting positive classes, while recall values spanning from 0.82 to 1.0 highlight its effectiveness in capturing relevant instances across all classes. Furthermore, the F1 score, representing a harmonized measure of precision and recall, reinforces the model’s commendable performance, with values ranging between 0.82 and 0.99. A class-specific analysis reveals notable strengths, notably the exceptional precision, recall, and F1 score of class 1, indicative of accurate and comprehensive predictions. Although class 5 exhibits slightly lower precision and recall, its performance remains within an acceptable range. Moreover, classes 2–4 demonstrate robust overall performance, characterized by high accuracy and balanced precision and recall. To gain deeper insights into the model’s practical applicability, it is essential to consider the specific context of the classification problem and the potential implications of false positives and false negatives. By doing so, further optimization and refinement of the model can be pursued, ensuring its efficacy and reliability in real-world autonomous farming scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Riset Percepatan Lektor Kepala (RPLK) No.: 1549/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2023 and supported by the Department of Electrical Engineering, Universitas Padjajaran, Indonesia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. AT: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing with the contribution of all co-authors. MT: data curation and methodology, resources, and project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data will be made available on request.

References

[1] Noor FA, Nasution DD. BPS: Agricultural sector growth still below pre-pandemic levels. 7 February 2023. https://ekonomi.republika.co.id.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Central Bureau of Statistics. Mid-year population (Thousand People), 2021–2023. Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023. https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/12/1975/1/jumlah-penduduk-pertengahan-tahun.html [Accessed 23 October 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Central Bureau of Statistics. Prevalence of food consumption insufficiency (Percent), 2020–2022. 2022. https://www.bps.go.id/indicator/23/1473/1/prevalensi-ketidakcukupan-konsumsi-pangan.html [Accessed 23 October 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Purnomo D. Food needs, agricultural land availability, and plant potential. Semarang, Indonesia: Sebelas Maret University Library; April 6, 2016. https://library.uns.ac.id/kebutuhan-panganketersediaan-lahan-pertanian-dan-potensi-tanaman/ [Accessed 23 10 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Rejeb A, Abdollahi A, Rejeb K, Treiblmaier H. Drones in agriculture: A review and bibliometric analysis. Computers Electron Agric. 2022;198(107017):1–19.10.1016/j.compag.2022.107017Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Apushev AK, Yussupov B, Salybekova NN, Mamadaliev A. Biomorphological analysis of tulip varieties on substrates in covered ground in Turkestan. J Human Earth Future. 2023;4(2):207–20.10.28991/HEF-2023-04-02-06Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Coordinating Ministry of Economic Midwives of the Republic of Indonesia. The government encourages the improvement of the food and agriculture sector for the welfare of the Indonesian people. Coordinating Ministry of Economic Midwives of the Republic of Indonesia, November 16, 2020. https://www.ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/647/pemerintah-dorong-peningkatan-sektor-pangan-dan-pertanian-untuk-kesejahteraan-masyarakat-indonesia. [Accessed 23 October 2023].Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Cornejo J, Barrera S, Ruiz CH, Gutiérrez F, Casasnovas MO, Kot L, et al. Industrial, collaborative and mobile robotics in Latin America: Review of mechatronic technologies for advanced automation. Emerg Sci J. 2023;7(4):1430–58.10.28991/ESJ-2023-07-04-025Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Ahirwar S, Swarnkar R, Bhukya S, Namwade G. Application of drone in agriculture. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2019;8(1):2500–5.10.20546/ijcmas.2019.801.264Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Mrema G, Soni P, Rolle RS. A regional strategy for. Bangkok: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Hafeez A, Husain MA, Singh S, Chauhan A, Khan MT, Kumar N, et al. Implementation of drone technology for farm. Inf Process Agric. 2023;10:192–203.10.1016/j.inpa.2022.02.002Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Umeda S, Yoshikawa N, Seo Y. Cost and workload assessment of agricultural drone sprayer. Sustainability. 2022;14(10850):2–11.10.3390/su141710850Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Shaikh TA, Rasool T, Lone FR. Towards leveraging the role of machine learning and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture and smart farming. Computers Electron Agric. 2022;198(107119):2–29.10.1016/j.compag.2022.107119Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Jia X, Cao Y, Zhu J, Tsang DC, Zou B, Hou D. Mapping soil pollution by using drone image recognition and machine. Environ Pollut. 2021;270(116281):2–10.10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116281Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Bhatnagar S, Gill L, Ghosh B. Drone image segmentation using machine and deep. Remote Sens. 2020;12(2602):2–26.10.3390/rs12162602Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Wen S, Zhang Q, Yin X, Lan Y, Zhang J, Ge Y. Design of plant protection UAV variable spray. Sensors. 2019;19(1112):2–23.10.3390/s19051112Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Ponnusamy V, Natarajan S. Precision agriculture using advanced technology of IoT, Unmanned aerial vehicle, augmented reality, and machine learning. Dalam smart sensors for industrial Internet of Things. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 207–29.10.1007/978-3-030-52624-5_14Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Suhaeni S, Wulandari E, Turnip A, Deliana Y. Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour. Open Agric. 2024;9(1):20220269.10.1515/opag-2022-0269Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Turnip A, Pebriansyah FR, Simarmata T, Sihombing P, Joelianto E. Design of smart farming communication and web interface using MQTT and Node.js. Open Agric. 2022;8(1):1–12. 10.1515/opag-2022-0159.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Andayani SA, Umyati S, Dinar, Tampubolon GM, Ismail AY, Dani U, et al. Prediction model for agro-tourism development using adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system method. Open Agric. 2022;7:644–55.10.1515/opag-2022-0086Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Duttaroy S, Nemade MU, Devgonde S, Parmar V, Gounder D. Efficient Field Monitoring Autonomous Drone (FMAD) with pesticide. Int Res J Eng Technol. 2021;8(4):2741–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Benos L, Tagarakis AC, Dolias G, Berruto R, Kateris D, Bochtis D. Machine learning in agriculture: A comprehensive updated review. Sensors. 2021;21(11):3758.10.3390/s21113758Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Khan S, Tufail M, Khan MT, Khan ZA, Iqbal J, Wasim A. Real-time recognition of spraying area for UAV sprayers using a deep learning approach. PLOS One. 2021;16(4):1–17.10.1371/journal.pone.0249436Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal