Abstract

A bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines (Xag) is one of the main diseases of soybeans in Thailand. Beneficial microbes crucial to sustainable plant production were examined in this study. Soybean plants were sprayed with Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s strain three times before Xag infection. The results showed a significant reduction in bacterial pustule disease severity by up to 85%, increased leaf accumulation of salicylic acid with 134% during the infection process of Xag. Furthermore, the Xag population size in soybean leaves was reduced by priming with SP007s. The mechanism of SP007s in the chemical structure of mesophyll was characterized by using the synchrotron radiation-based Fourier transform infrared (SR-FTIR) analysis. The SR-FTIR spectral changes from the mesophyll showed higher integral area groups of polysaccharides (peak of 900–1,200 cm−1). These biochemical changes were involved with the primed resistance of the soybean plants against the bacterial pustule disease as well as the polysaccharide signals that were linked to hypersensitive responses leading to a rapid death of plant cells to effectively restrict the growth of pathogens at the infected site. Therefore, we consider that SP007s can be a promising biocontrol agent by activating immunity of soybean plants.

1 Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max) is one of the most important economic crops that supply large sources of fatty acids, proteins, vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients [1] for humans and animals. Soybean is also used in the manufacturing of industrial feedstocks and combustible fuels, among other non-food applications [2]. However, insect pests and pathogens cause important diseases globally, especially the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines (Xag), which can significantly reduce the production of soybeans by causing symptoms such as leaf spots, pustules, and defoliation. Therefore, the development and improvement of bioagents inducing resistance against bacterial pustules is one of the main objectives for soybean production. In biocontrol agents, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) provide an environmentally friendly way to control plant diseases in agriculture [3]. The PGPR penetrates and produces biofilms on the outer surface of plant roots, which produce antimicrobial substances, such as antibiotic metabolites and bacteriocins. The inhibitory effects of such chemicals on pathogens help to reduce plant diseases by directly inhibiting pathogens or making the plant resistant to them. Pseudomonas species have been extensively studied for their beneficial effects on plants. The key findings are condensed in a number of thorough studies showing that increasing the availability and absorption of mineral nutrients via mineral solubilization results in plant development and yield increase. Many Pseudomonas strains can effectively inhibit pathogen attacks through direct and indirect mechanisms. In addition, Pseudomonas species can activate the salicylic acid (SA)-dependent signaling system that provides disease resistance to multiple plant species such as rice, vegetables, tomato, and grape [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. P. fluorescens SP007s is a bacterium with significant advantages in biocontrol, particularly in managing plant diseases and promoting sustainable agriculture. One of the primary benefits of using SP007 is its strong antifungal and antibacterial properties. The bacterium produces various secondary metabolites, including antibiotics such as pyoluteorin, 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG), and phenazine, which are effective against a broad spectrum of plant pathogens [8]. Research has shown that specific formulations of SP007 are highly effective in controlling soft rot disease cause by Pectobacterium carotovorum and promoting growth in kale [9]. This highlights its potential to enhance crop yield and quality in vegetable production. Additionally, bioformulations of SP007s have proven effective against dirty panicle disease of rice cause by Trichoconis padwickii Ganguly, Cercospora oryzae, Curvularia lunata, Fusarium semitectum, Bipolaris oryzae, and Sarocladium oryzae and also increased gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in treated seeds, suggesting that this microorganism may enhance the plant’s defense against stress conditions [10].

The SA-dependent mechanism involves the production of SA, which is linked to various physiological processes in plants, including defense responses that are induced by plant pathogen infections [11]. Priming is a crucial process in induced resistance, in which plants demonstrate a more rapid and robust production of defense mechanisms in response to bacterial pathogen infection [12]. The main regulators of signaling networks that are involved in induced plant defense include the following plant hormones: SA, jasmonic acid, and ethylene [13]. P. fluorescens produces a range of secondary metabolites, enzymes, and volatile organic compounds that help in inhibiting the growth and colonization of harmful pathogens. These mechanisms can induce host-defense responses and enhance the resistance of the host organism against infections [14]. Upon pathogen recognition, plants can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) through an oxidative burst. ROS, such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals, act as signaling molecules and contribute to the activation of defense responses. They can also induce programmed cell death (PCD) in the infected area, limiting the pathogen spread. PCD in the infected area is a fundamental component of the hypersensitive response (HR) in plant defense. HR initiates SAR extending the localized defense systemically throughout the plant, providing long-term protection, and enhancing plant resistance to pathogens [15]. P. fluorescens is known for its ability to trigger HR in plants, which restricts the spread of pathogens. P. fluorescens isolates use their type III injector systems to deliver effector proteins to the host plant cells, triggering the HR and thereby contributing to the plant defense against pathogens [16]. This type of injector system is commonly denominated as type III secretion system (T3SS) referencing complex molecular mechanisms. The T3SS enables the bacteria to inject effector proteins directly into the cytoplasm of host cells [17]. The effector proteins are usually enzymes or signaling molecules that can modulate multiple cellular processes, including membrane trafficking, cell signaling, and immune response [18]. Thus, the initial contact with P. fluorescens initiates an HR response, which triggers systemic resistance involving SA as the signal. One of the responses is the formation of callose, which can be detected by Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) microspectroscopy. FTIR microspectroscopy may also detect other metabolites involved in defense by identifying characteristic absorption bands related to functional groups such as proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates [19]. Monitoring changes in these absorption bands can provide insights about the production and accumulation of defense-related metabolites.

The main objective of the present study was to explore the potential of P. fluorescens SP007s for controlling the bacterial pustule caused by Xag through stimulation of the plant defense intermedia, including endogenous SA. Moreover, the biochemical changes were analyzed, having a special focus on phospholipids, pectins, amides, lignins, and polysaccharides, which are associated with defense mechanisms in soybean plants during Xag infection.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material, bacterial strains, and inoculum preparation

The soybean seeds of the susceptible cultivar (CV.SJ.4) were used in this study. The seeds were sterilized with 10% Clorox for 1 min, rinsed with sterile water three times [20], and sown in 10-in diameter pots containing natural sterile soil and fertilizer.

P. fluorescens SP007s strain and Xag were provided by the Plant Pathology Section of Thammasat University, Thailand. Cultures were revived by streaking the stock culture (−20°C). Then, it was re-cultured on nutrient agar (NA) medium and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 48 h. P. fluorescens SP007s was prepared in 500 mL of Luria–Bertani (LB) broth, and Xag was prepared in 500 mL of nutrient broth for 48 h at 180 rpm, 28 ± 2°C. Afterward, the cultures were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min to remove the broth compounds. The cell biomass was preserved at 4°C and adjusted to 1 × 108 cfu mL−1 with sterile distilled water before being used for further experimentation.

2.2 Priming of plant and Xag inoculation

The experiment with four treatments, including SP007s, SA, copper hydroxide, and sterile distilled water, was conducted in a completely randomized design (CRD) with four replications, three plant per replication. The plants were sprayed with 30 mL of SP007s (1 × 108 cfu mL−1) at 7, 14, and 21 days post-sowing (dps) as a priming stage. The procedure was carried out in the same manner, with 1 mM SA and copper hydroxide 77% WP in separate as a positive control and sterile distilled water as a negative control. At 45 dps, the soybean plants in all treatments were inoculated with a density of Xag suspension at 1 × 108 cfu mL−1 by foliar spraying, covered with plastic bags, and incubated for 24 h. Next, the plants were moved from the plastic bags to the greenhouse. The pots were kept under greenhouse conditions under 12 h of photoperiod, 28 ± 4°C, and 60–75% humidity for further experimentation.

2.3 Detection of endogenous SA

Soybean leaf samples from each treatment (0.5 g) were homogenized in liquid nitrogen mixed with 1 mL of extraction buffer, 90% methanol, 9% glacial acetic acid, and 1% water. Next, they were centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. About 0.5 mL of the sample was mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.02 M ferric ammonium sulfate solution and incubated at 30°C for 5 min. Two hundred microliters of each sample were transferred to a 96-well plate. The absorbance was read at 530 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA) and compared with the SA (Sigma, USA) standard curve in order to determine the amount of endogenous SA in the sample.

2.4 PCD of SP007

The leaf samples were collected at 24 h post-inoculation to detect PCD, HR associated cell death in response to Xag infection. The leaf samples were decolorized by boiling them in trypan blue–lactophenol (2 mg trypan blue, 25% lactic, 23% phenol, 25% glycerol) at 95°C for 5 min and soaked in 25% chloral hydrate overnight. Subsequently, the leaf samples were washed with water, soaked in 0.1% aniline blue for 1 min, washed with water again, and mounted on a Petri dish with 30% glycerol in water. The stained cells on the epidermis were counted as a cell death event.

2.5 Rapid detection of biochemical changes using synchrotron radiation-based Fourier-transform infrared (SR-FTIR) microspectroscopy

The leaf samples were collected and fixed in the optimal cutting temperature compound (Scigen Tissue-Plus™, England) with liquid nitrogen to embed tissue samples prior to frozen sectioning on a microtome-cryostat. The samples were sliced at 7 μm by using a Wetzlar cryostat microtome (Germany) and then laid on a 13 mm × 2 mm window. The spectral data were collected at the beamline 4.1 Synchrotron Light-IR Spectroscopy station. The measurement was identified by mapping an aperture size of 10 μm × 10 μm and a spectral resolution mode of 4 cm−1 with 64 scans. The spectral derivative was generated with OPUS 7.2 software (Hanau, Germany), and the data were analyzed with the CytospecTM software and the unscramblerX 10.0 software (NJ, USA) [19]. The average spectra of each sample were explained by references of band assignments and the functional groups of FTIR spectra (Table S1).

2.6 Disease rating

The bacterial pustule disease symptoms that appeared on the studied soybean leaves after 14 days post-inoculation (dpi) were analyzed based on the scale developed by Zhao et al. [21] (Table 1, Figure S1)

Bacterial pustule disease symptoms scaled by the disease spot numbers at five levels

| Disease scale | Infection of plant |

|---|---|

| 1 | Symptoms are found on less than 20 disease spots in the leaf area |

| 3 | 21–50 irregular disease spots |

| 5 | >50 small lesion, deformed disease spots covering 10–25% of the leaf area |

| 7 | A large lesion covering the surface of 25–50% of the soybean leaf |

| 9 | A large lesion covering the surface of more than 50% of the soybean leaf |

The disease severity index and the control efficacy were calculated as follows (formulas (1) and (2)) [22]:

2.7 Evaluation of Xag growth in the soybean plants

The experiments, including SP007s-treated and SP007s-untreated, were conducted in CRD with four replications. The SP007s-treated and SP007s-untreated soybean leaves were observed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, and 14 dpi with Xag. Leaves were cut into 8 mm diameter leaf disks by using a cork borer, and they were homogenized in 1 mL of sterile 10 mM MgCl2. The leaf homogenate was diluted in a serial dilution and spread on NA plates. Next, the samples were incubated in the growth chamber for 24 h. The colonies that appeared on NA plates were counted as the metric for each sample.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The obtained experimental data were analyzed using the one-way ANOVA software version 20 by SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The mean difference values among groups were divided according to Duncan’s multiple range test with a significant test result (p ≤ 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Detection of endogenous SA

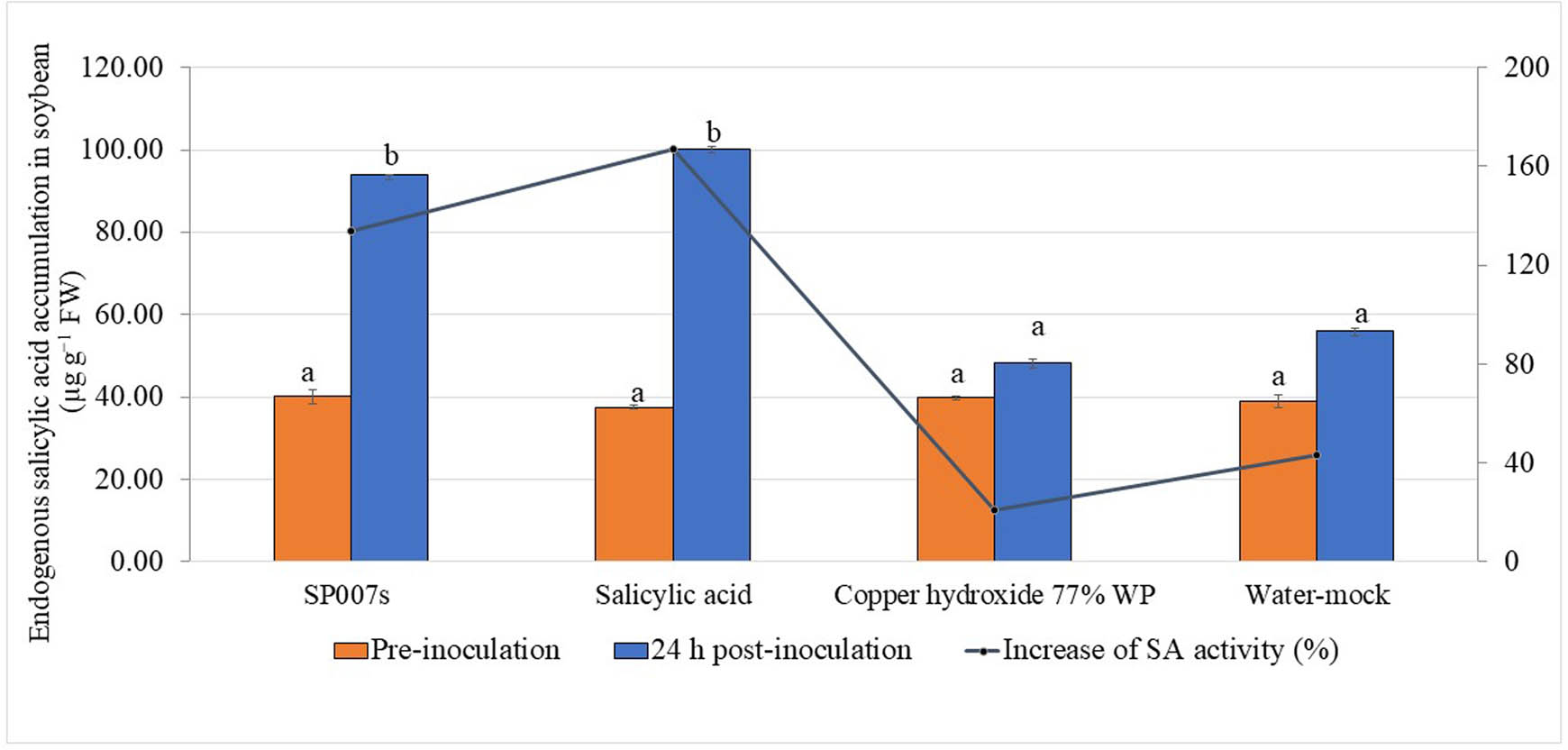

An increase in endogenous SA content was observed in soybean leaves at the pre-inoculation stage and 24 h post-inoculation (hpi) with Xag. The results revealed that soybean plants treated with SP007s three times before inoculation increased the content of endogenous SA from 40.13 to 93.86 µg g−1 FW and in the SA-treated samples (100.30 µg g−1 FW), followed by the water-mock and the copper hydroxide-treated plants, which increased to 55.90 and 48.15 µg g−1 FW, respectively (Figure 1).

Effects of pre-foliar spraying of soybean plant with Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s, SA, copper hydroxide 77% WP (20 g L−1) (commercial pesticide), and water-mock treatment (negative control) three times before Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines inoculation on the concentration of endogenous SA. Values are presented as the mean of four replicates, three plants per replication. Mean values in the graph followed by different letters are significantly different according to DMRT at p ≤ 0.05.

3.2 Biochemical change analysis in soybean mesophyll

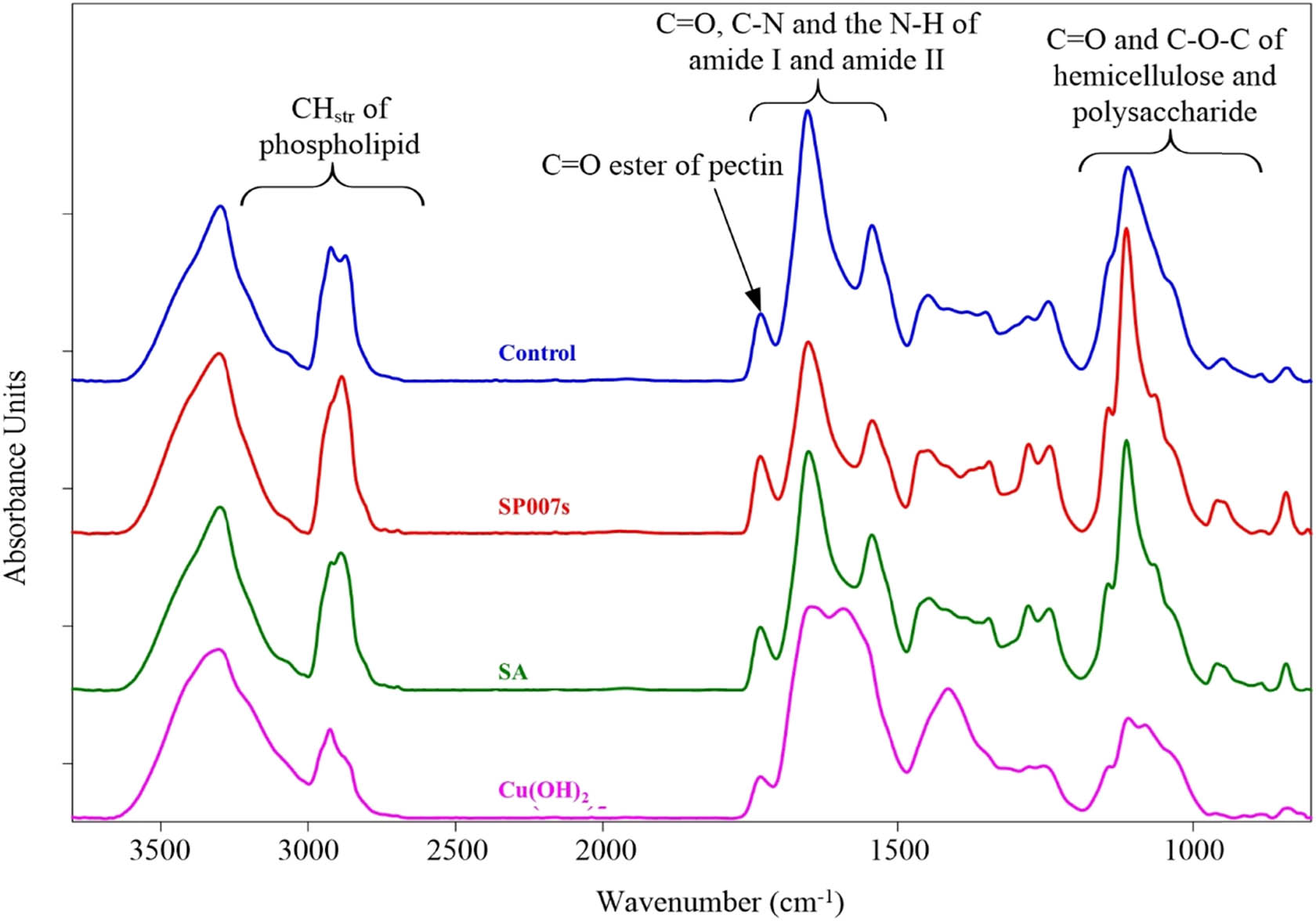

The average spectra of the chemical compounds and the structure of the plant cells in the soybean tissue at the mesophyll level were observed in the range of 3,000–900 cm−1. The averaged spectra from SR-FTIR microspectroscopy showed the characteristic features of C═O stretching from lipids and pectins exhibited peak at 1,730 cm−1, C–N and N–H stretching of protein amide I at 1,650 cm−1 and amide II at 1,530 cm−1, C–C ring from cellulose at 1,150 cm−1, C–C and C–O–H consisting of polysaccharides and polycarbohydrates at 1,100–1,000 cm−1 as shown in Figure 2. Such spectral peaks can be used to characterize the biochemical components of the samples in each treatment.

The average original spectra of soybean tissue (mesophyll) from the water-mock treated samples (control), Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s-treated (SP007s), SA treated, and copper hydroxide (Cu(OH)2) treated were measured by SR-FTIR microspectroscopy.

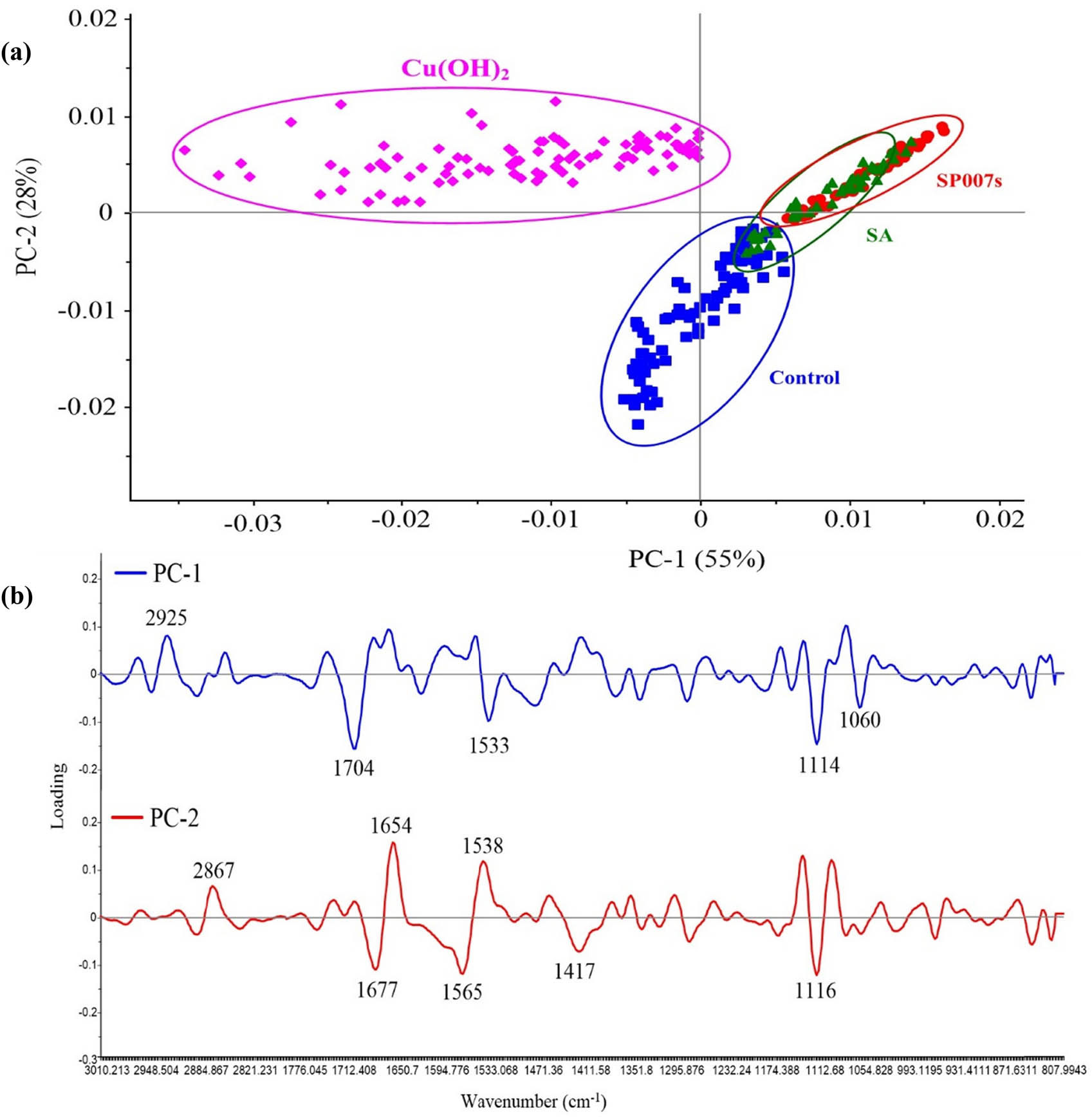

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to classify the groups of the treatment distributions, as shown in Figure 3a. The results showed three clearly distinguishable groups: the SP007s- and SA-treated groups, the copper hydroxide-treated group, and the water-mock group. Such groups were separated by PC1 and PC2, represented by 55 and 28% of the variance, respectively. The PC1 loading plot showed the disparate variables between the SP007s- and SA-treated samples from the copper hydroxide-treated samples and the water-mock treated samples.

(a) The categorization of soybean tissue on each treatment using PCA score plots. (b) Loading factors of PC1 and PC2 correspond to the PCA score plots of SR-FTIR microspectroscopy.

The PC1 loading plot indicated that the phospholipids peaked at 2,925 cm−1, C═O, C–N, and N–H of amide I and amide II exhibited peaks at 1,704 and 1,533 cm−1, and the C–O–C stretching of hemicellulose and polysaccharides peaked at 1,114 and 1,060 cm−1, which corresponds to the copper hydroxide-treated samples and the water-mock treated samples. The divergence of the water-mock treated samples (control) from the copper hydroxide-treated samples, the SP007s-treated samples, and the SA-treated samples was identified by the PC2 loading plot. The PC2 loading plot showed peaks at the phospholipid section at 2,867 cm−1, and at the proteins amide I and II sections at 1,654 and 1,538 cm−1, respectively (Figure 3b).

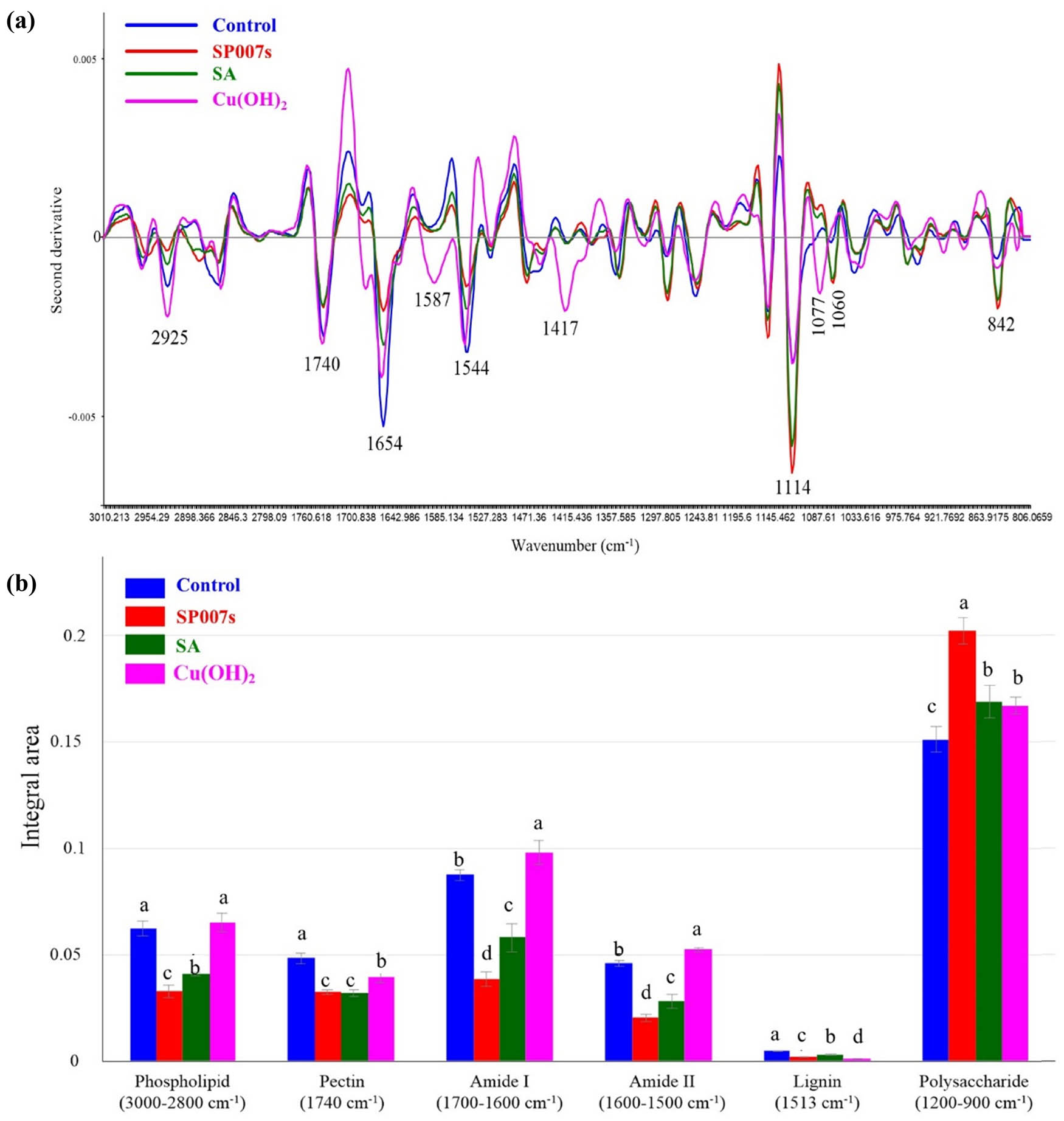

The comparison among the spectra of the soybean leaf tissues in the range of 3,000–900 cm−1 is shown in Figure 4a. Biochemical composites in the SP007s treatment spectrum of the CO–CC polysaccharide section showed higher values than those from the other treatments at the vibrational peak at 1,114 cm−1. The alpha helix structure of the amide I protein exhibited peak at 1,654 cm−1 in the water-mock treated samples spectrum, which was the highest. However, the stacking of the second derivative of the average spectra was not clear for each range of biochemical composition. Thus, we integrated the area under the IR peak based on the separation into six groups of the chemical components, including phospholipid (3,000–2,800 cm−1), pectin (1,740 cm−1), amide I (1,700–1,600 cm−1), amide II (1,600–1,500 cm−1), lignin (1,513 cm−1), and polysaccharide (1,200–900 cm−1), as shown in Figure 4b. The results revealed that the integral areas of phospholipid, amide I, amide II, and lignin from the mesophyll soybean leaf tissue in the SP007s-treated samples were significantly lower compared to the other treatments. Polysaccharides from the SP007s-treated samples were observed to be significantly higher than those from the other treatments.

(a) Overlay of the second derivative of the average spectra from the soybean mesophyll-treated sample, including Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s-treated (SP007s), SA-treated, and copper hydroxide-treated (Cu(OH)2) compared with water-mock treated (control). (b) Integral areas of absorbance between 3,000 and 900 cm−1. Mean values in the graph followed by different letters are significantly different according to DMRT at p ≤ 0.05.

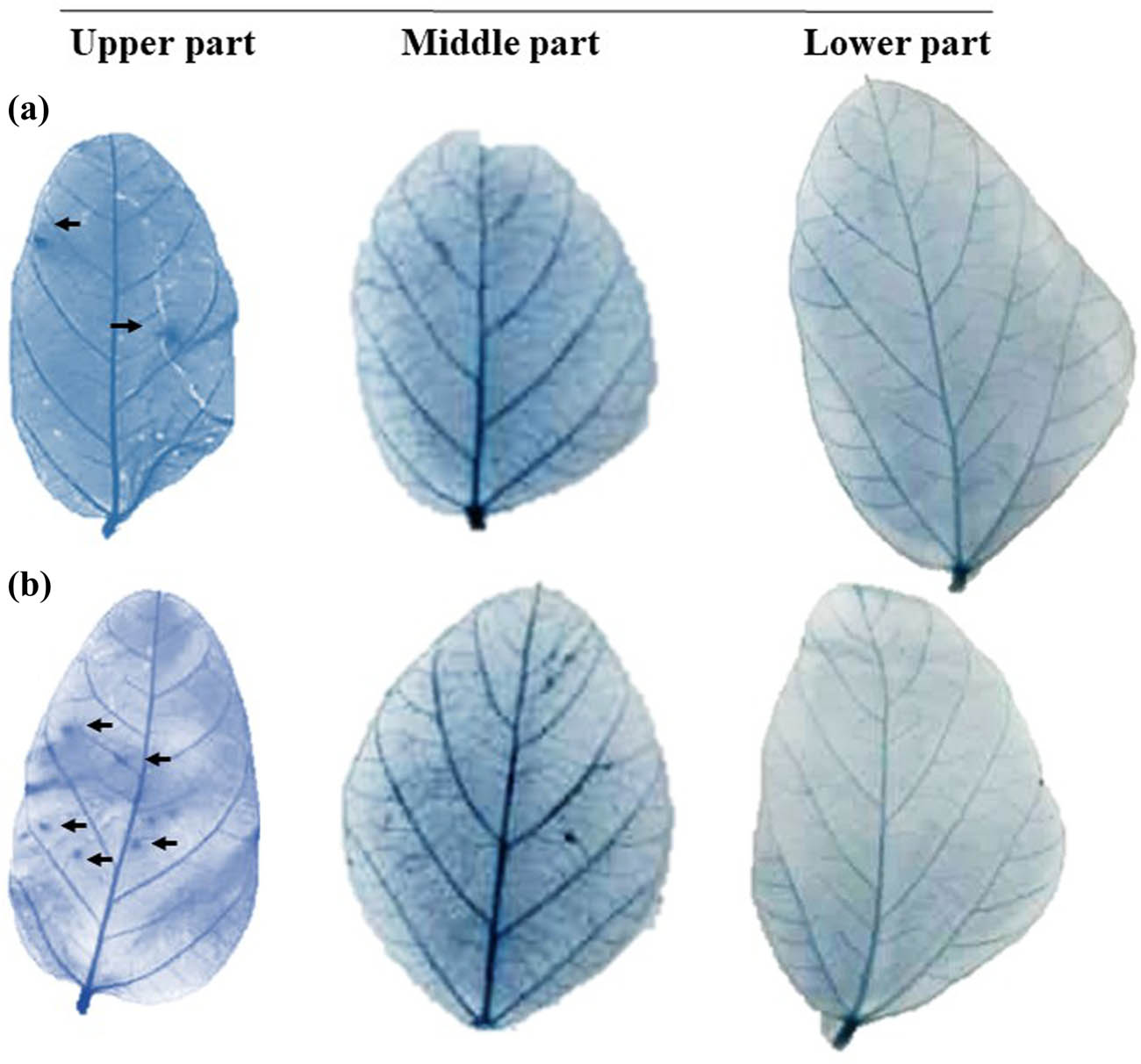

3.3 Detection of PCD of SP007s

Trypan blue staining of the leaf tissues at 24 hpi was used to observe rapid PCD in water-mock treated and SP007s-treated leaf samples, as shown in Figure 5. Water-mock treated leaves showed lower cell death spots (black arrows) compared to the SP007s-treated samples.

Observed program cell death events in treated leaves at 16 h post-inoculation on the upper, middle, and lower parts of the soybean plant (left to right): (a) water-mock treated and (b) Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s-treated.

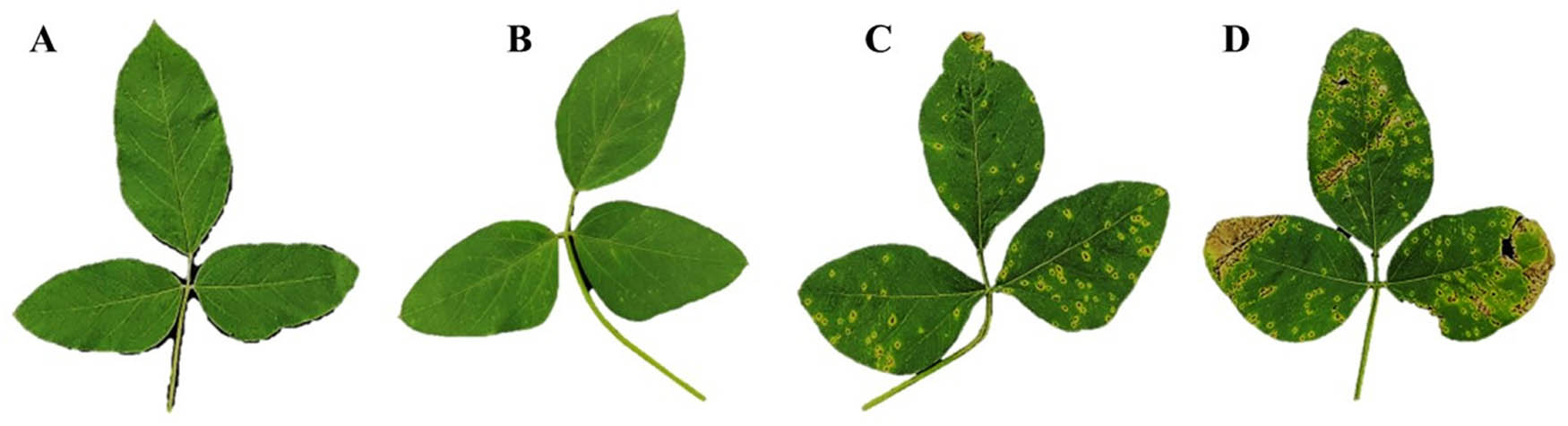

3.4 Disease rating

The SP007s was assessed for its ability to induce plant resistance by foliar spraying at 7, 14, and 21 dps. The results showed that the plants treated with SP007s significantly reduced the disease severity of bacterial pustule at 14 dpi compared to the samples treated with water-mock. The disease severities of the soybean plants treated with SP007s had an average ratio of 11%, followed by the samples treated with SA (17%) and the copper hydroxide-treated samples (44%). These measured disease severities were significantly lower than the ones obtained from the water-mock-treated samples, which was 72% (Table 2 and Figure 6).

Efficacy of Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s on the severity and reduction of the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines under greenhouse conditions

| Treatment1 | Disease severity (%) | Reduction of disease severity compared with control (%) |

|---|---|---|

| SP007s | 11c | 85 |

| SA | 17c | 77 |

| Copper hydroxide | 44b | 38 |

| Water-mock | 72a |

1The plants were induced by the foliar spraying technique for each treatment at 7, 14, and 21 dps before Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines inoculation. The mean in the column followed by the same letter (a, b, c) is a non-significance difference according to Duncan’s multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05.

Disease symptoms in infected and treated leaves at 14 dpi: (a) Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s-treated, (b) SA-treated, (c) copper hydroxide-treated, and (d) water-mock treated samples.

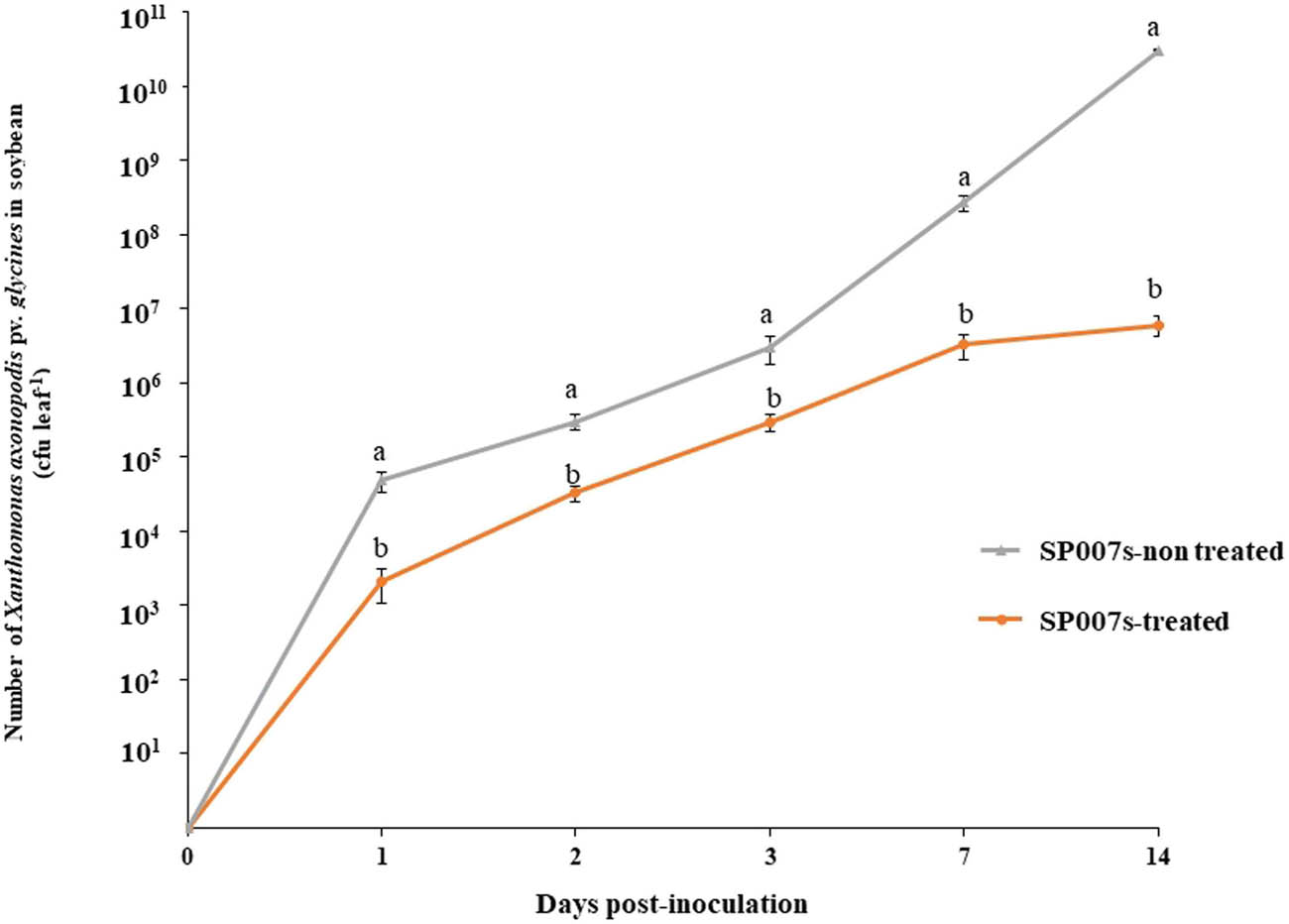

3.5 Assessment of Xag growth in the soybean plants

The population sizes of Xag between SP007s-treated leaves and the control leaves were compared. At 7 dpi, the population of Xag in soybean leaves treated with SP007s had grown to 3.3 × 106 cfu leaf−1 and reached a maximum of 6.1 × 106 cfu leaf−1 at 14 dpi. However, the Xag population in the leaves treated with distilled water multiplied to 3.1 × 1010 cfu leaf−1 at 14 dpi. The Xag population size on the leaves treated with SP007s samples was half of the leaves treated with distilled water, indicating that the application of SP007s in foliar spray reduced the growth of Xag (Figure 7).

Growth curves of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines in the soybean plant samples treated and non-treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s, which were inoculated with Xag under greenhouse conditions. 0 days is before inoculation. The mean in the column followed by the same letter (a, b) is a non-significance difference according to DMRT at p ≤ 0.05.

4 Discussion

Pseudomonas strains have been extensively utilized due to their growth promotion and biological control activities. Several reports have highlighted the capacity of Pseudomonas spp. to suppress the proliferation of plant pathogens through various mechanisms, such as direct interaction and induced resistance. In this study, the PGRP activity of SP007s was confirmed, and its biological control potential was demonstrated. SP007s significantly decreased bacterial pustule on soybeans caused by Xag with detected changes in the biochemical components. The crucial roles of SP007s in plant immunological interactions were explored by examining the alterations in the intermediate biochemical composition of the host defense system. This included investigating the changes in SA, which is associated with enhanced resistance against soybean bacterial pustules. Spraying the SP007s three times before pathogen inoculation resulted in a significant increase in endogenous SA contents of a 134%. During pathogen invasion and infection, the contents of endogenous SA are always increasing in order to prevent further infection. However, resistant plants often exhibit a more rapid and higher increase in endogenous SA levels [11]. This heightened response is due to the presence of specific resistance genes that facilitate a robust defense signaling cascade, which can modulate the activity of plant defense mechanisms, leading to changes in the physiological, biochemical, and molecular states of the plant [23,24,25]. The SA pathway stimulates the production of antimicrobial proteins, phytoalexins, and other defense compounds [26]. SA acts as a signaling molecule to activate SAR, which increases the plant resistance to subsequent pathogen attacks [27,28]. The priming effect induced by microbial bioagents as elicitors results in enhanced readiness and responsiveness of plant defense mechanisms, allowing plants to respond more rapidly and effectively when they encounter pathogen attacks [29]. Plants detect and activate defense signals early during the pathogen infection process. Plants produce damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as extracellular protein fragments, peptides, nucleotides, and amino acids. Lakkis et al. reported that P. fluorescens is an inducer of ISR in grapevine, which increased endogenous SA and 1-aminocyclopropane carboxylic acid contents after a Botrytis cinerea infection [6]. Similarly, Suresh et al. [5] demonstrated that the P. fluorescens VSMKU3054 can induce systemic resistance in tomatoes against Ralstonia solanacearum by increasing the amount of defense-related enzymes, including peroxidase, polyphenol oxidase, lipoxygenase, phenylalanine ammonia lyase, and the total phenol content that involves SA-dependent signaling and SA pathway.

The resistance activity of these intermedia enzymes can contribute to changes in their biochemical components. In this research, the biochemical changes in soybean mesophyll tissue were investigated by using the SR-FTIR technique to describe the defense mechanism of the SP007s-treated samples. The results showed that the spectral range of 1,200–900 cm−1, which corresponded to the C–O stretching, C–H bonds, and C–O ring vibrations from the SP007s-treated samples revealed a significantly higher agglomeration of polysaccharides in comparison to the water-mock treated samples. Degradation often involves chemical reactions that modify the structure of the polysaccharide formed as degradation products, leading to additional absorption bands in the FTIR spectrum. Polysaccharides are complex carbohydrates that occur naturally and consist of chains of sugar residues linked by glycosidic bonds. They play regulatory roles in various biological processes. It is an important component of a plant defense strategy against biotic stress, as well as for protecting the plant from attacks by pathogens [30]. Plant cell walls are composed of various polysaccharides, which serve as informational components that initiate the production of different defense compounds. These include phytohormones, pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, and secondary metabolites [31,32]. Multiple reviews have indicated that the polysaccharides found in the plant cell wall mainly contribute to growth, and disease resistance, and are engaged in different biotransformation processes [33]. In response to pathogen attacks, plants can produce enzymes that facilitate the addition or removal of specific sugars from the polysaccharides. This enzymatic activity can modify the properties of the cell wall, making it more resistant to pathogen attacks. At the same time, Kozieł et al. [33] demonstrated that the constituent plant cell wall metabolism can alter the transmission of viruses and trigger apoplast and symplast resistance mechanisms, thereby contributing to the complex network of the plant defense system. In addition, polysaccharides are involved in plant PCD. PCD is a natural and tightly regulated process that occurs in plants as well as in other multicellular organisms that are involved in various developmental processes, responses to environmental cues, and defense mechanisms. However, not all tissues can respond to the same extent with increased PCD. PCD is more prevalent in specific parts of the plant and younger leaves (Figure 5). PCD is an essential process in plant development, defense, and response to various stresses. It involves a coordinated series of biochemical and morphological events that lead to the selective elimination of cells. One form of PCD in plants is HR, which occurs during defense responses against pathogens. To facilitate host colonization, phytopathogenic bacteria secrete immune-suppressive effectors into host cells via the T3SS [34]. Biocontrol agent, P. fluorescens, secretes a variety of effector proteins into the host plant cells. These effectors can manipulate host cell processes to promote bacterial colonization [35]. However, some of these effectors can also be recognized by plant immune receptors, leading to the activation of defense responses, where their recognition triggers the HR [36,37,38].

De Vleesschauwer et al. [4] demonstrated that the application of P. fluorescens WCS374r as an inducer enhanced basal defense against the leaf blast pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae by an SA-independent mechanism, suggesting alternative pathways might be involved in the plant’s immune response. The rapid recruitment of phenolic compounds, triggering reiterative hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) microbursts, and causing rapid HR-associated cell death in response to fungal infection consisting of rapid recruitment of phenolic compounds at sites of pathogen entry, concerted expression of a diverse set of structural defenses, and a timely hyperinduction of hydrogen peroxide formation putatively driving cell wall fortification. HR often can induce SAR-enhanced resistance to pathogenic infection through the SA pathway in which the entire plant becomes more resistant to subsequent infections [39,40]. Similarly, Gruau et al. demonstrated that P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 triggers local HR and systemic immunity, which integrates SA signaling in grapevine [41]. During root colonization by PTA-CT2, the grapevine roots trigger some induction of localized HR-like cell death in roots after pathogen infection as rapid induction of the hypersensitive related gene, a known marker for HR, at 24 hpi. Subsequently, the expression patterns of the SA pathway. Callose is a specific type of polysaccharide that is a β-1,3-glucan polysaccharide. It is a major component of the plant cell wall and is involved in various physiological processes, including defense responses [42]. Callose deposition often occurs in response to pathogen infection or other environmental stresses, and it is an SA-pathway marker in reinforcing cell walls [43,44]. During PCD, plants increase callose deposition. It is a common phenomenon initiated at early, intermediate, and late defense responses within the host cell.

The cell wall serves as the initial defense mechanism in plants, contributing to the specificity of disease resistance and to the overall fitness [45]. Biochemical profiling using synchrotron-based spectroscopy visualizes the changes in the biochemical spectrum of cell wall components in relation to host defense responses [46,47]. Our results showed an increased peak intensity in polysaccharides, suggesting that these structural components have a role in the response to pathogen infection. Increasing the levels of polysaccharides in plants is one of the strategies employed by the plant to enhance its defense against pathogens [48]. DAMPs, microbe-associated molecular patterns, and lipopolysaccharides are involved in plant defense mechanisms, particularly in the context of the polysaccharides present in the plant cell wall [49]. These molecular patterns serve as signals that the plant uses to detect and respond to cellular damage or the presence of potential pathogens, activating immune mechanisms to protect the plant [50]. P. fluorescens can produce pectinolytic enzymes, including pectinases such as polygalacturonases and pectate lyases [49]. These enzymes can degrade pectin, a major component of the plant cell wall, by breaking down its various constituents, including homogalacturonan (HG) [51]. The release of pectin fragments, such as DAMPs and oligogalacturonides (OGs), can trigger defense responses in plants, and the modification of HG can contribute to the reinforcement of the cell wall [52]. In accordance with the investigations of Benedetti et al., and Gramegna et al. [53,54] reported that the breakdown products of HG, which include OGs, are considered DAMPs that are produced in response to plant pathogen attacks and physical damage. OGs, derived from the degradation of HG, are considered DAMPs that serve as both a defense response against pathogen attacks and a local signal to alert the plant about physical damage. Davidsson et al. [55] reported that OGs can enhance the resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana, which induces pathogen resistance-associated gene expressions. Similarly, Gravino et al. [31] stated that OGs can activate a complicated signaling route that leads to the creation of numerous defenses, including phytohormones, secondary metabolites, and PR proteins. Similarly, Yu et al. [56] stated that the beneficial microbes can increase the levels of SA, leading to the transcriptional activation of genes encoding PR proteins. Moreover, P. fluorescens also has a direct mode of action. This direct action includes the secretion of antimicrobial compounds, siderophores, and enzymes that degrade pathogenic cell walls and can inhibit competing microorganisms as well as plant pathogens [57,58]. Additionally, the bacterium’s ability to colonize plant roots effectively ensures that it can exert these biocontrol activities precisely where they are needed most [59]. The combination of direct antimicrobial action and the induction of plant defenses underscores the multifaceted approach of P. fluorescens to promoting plant health and protecting crops from a variety of pathogens. Through its diverse modes of action, P. fluorescens not only protects plants from pathogens but also promotes healthier plant growth, contributing to increased agricultural productivity [60] as shown in Figure S2 and Table S2. Therefore, SP007s can be used as a biocontrol agent against this specific pathogen for a sustainable crop protection strategy in agriculture.

5 Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of a spray-induced treatment with SP007s as an environmentally sustainable solution for controlling the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xag. The findings indicate that SP007s effectively stimulate plant defense responses, resulting in significant changes in the biochemical components within the mesophyll, including an increased accumulation of SA and polysaccharides. These metabolites play a crucial role in inhibiting the growth of Xag, leading to an important reduction in disease severity. In order to fully explore the practical application of SP007s as a priming agent for soybeans, additional research is required, particularly through field-scale experiments.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Synchrotron Light Research Institute (SLRI) in Thailand, which provided the FTIR instruments and the beamline 4.1 Infrared Spectroscopy and Imaging systems.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by Center for Advanced Studies for Tropical Natural Resources (CASTNaR), Kasetsart University, that has been granted by the Office of the Higher Education Commission.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. DA and SP: conceptualization, DA, WT, SS experiment investigation, DA and WT arranging the results, discussion, and writing the original draft. DA, WT, and SP: revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Supplementary materials: Figure S1, Figure S2, Table S1 and Table S2.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Fehily AM. SOY (SOYA) BEANS | Dietary Importance. In: Caballero B, editor. Encyclopedia of food sciences and nutrition. 2nd edn Oxford: Academic Press; 2003. p. 5392–8.10.1016/B0-12-227055-X/01112-3Search in Google Scholar

[2] Güzeler N, Yıldırım Özbek Ç. The utilization and processing of soybean and soybean products. J Agric Faculty Uludağ Univ. 2016;30:546–53.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Aqeel M, Ran J, Hu W, Irshad HMK, Dong L, Akram M, et al. Plant-soil-microbe interactions in maintaining ecosystem stability and coordinated turnover under changing environmental conditions. Chemosphere. 2023;318:137924. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.137924.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] De Vleesschauwer D, Djavaheri M, Bakker PA, Höfte M. Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374r-induced systemic resistance in rice against Magnaporthe oryzae is based on pseudobactin-mediated priming for a salicylic acid-repressible multifaceted defense response. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1996–2012. 10.1104/pp.108.127878.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Suresh P, Shanmugaiah V, Rajagopal R, Muthusamy K, Ramamoorthy V. Pseudomonas fluorescens VSMKU3054 mediated induced systemic resistance in tomato against Ralstonia solanacearum. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2022;119:101836. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2022.101836.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Lakkis S, Trotel-Aziz P, Rabenoelina F, Schwarzenberg A, Nguema-Ona E, Clément C, et al. Strengthening grapevine resistance by Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 relies on distinct defense pathways in susceptible and partially resistant genotypes to downy mildew and gray mold diseases. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1112. 10.3389/fpls.2019.01112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Takishita Y, Charron JB, Smith DL. Biocontrol rhizobacterium Pseudomonas sp. 23S induces systemic resistance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) against bacterial canker Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2119. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Kladsuwan L, Chuaboon L, Prathuangwong S. Identification of Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s genes involved in antibiotic synthesis against Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines. Proceedings of 51st Kasetsart University Annual Conference: Plants; 2013. p. 2–12.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Nilmat A, Thepbandit W, Chuaboon W, Athinuwat D. Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007S formulations in controlling soft rot disease and promoting growth in kale. Agronomy. 2023;13:1856. 10.3390/agronomy13071856.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Prathuangwong S, Athinuwat D, Chuaboon W, Chatnaparat T, Buensanteai N. Bioformulation Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s against dirty panicle disease of rice. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:5274–83. 10.5897/AJMR2013.2503.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Conrath U. Systemic acquired resistance. Plant Signal Behav. 2006;1:179–84. 10.4161/psb.1.4.3221.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Tiwari M, Pati D, Mohapatra R, Sahu BB, Singh P. The impact of microbes in plant immunity and priming induced inheritance: A sustainable approach for crop protection. Plant Stress. 2022;4:100072. 10.1016/j.stress.2022.100072.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Pieterse CMJ, Van Loon LC. NPR1: The spider in the web of induced resistance signaling pathways. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:456–64. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.05.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Rani A, Rana A, Dhaka RK, Singh AP, Chahar M, Singh S, et al. Bacterial volatile organic compounds as biopesticides, growth promoters and plant-defense elicitors: Current understanding and future scope. Biotechnol Adv. 2023;63:108078. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108078.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Liu PP, Bhattacharjee S, Klessig DF, Moffett P. Systemic acquired resistance is induced by R gene-mediated responses independent of cell death. Mol Plant Pathol. 2010;11:155–60. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00564.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Mazurier S, Merieau A, Bergeau D, Decoin V, Sperandio D, Crépin A, et al. Type III secretion system and virulence markers highlight similarities and differences between human- and plant-associated pseudomonads related to Pseudomonas fluorescens and P. putida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:2579–90. 10.1128/aem.04160-14.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Liu P, Zhang W, Zhang L-Q, Liu X, Wei H-L. Supramolecular structure and functional analysis of the type III secretion system in Pseudomonas fluorescens 2P24. Front Plant Sci. 2016;6:1190. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01190.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Rajamuthiah R, Mylonakis E. Effector triggered immunity. Virulence. 2014;5:697–702. 10.4161/viru.29091.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Thepbandit W, Srisuwan A, Siriwong S, Nawong S, Athinuwat D. Bacillus vallismortis TU-Orga21 blocks rice blast through both direct effect and stimulation of plant defense. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1103487. 10.3389/fpls.2023.1103487.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Liu Y, Li X, Li X, Liu K, Rao G, Xue Y. Optimization of aseptic germination system of seeds in soybean (Glycine max L.). J Phys: Conf Ser. 2020;1637:012077. 10.1088/1742-6596/1637/1/012077.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Zhao F, Cheng W, Wang Y, Gao X, Huang D, Kong J, et al. Identification of novel genomic regions for Bacterial Leaf Pustule (BLP) resistance in soybean (Glycine max L.) via integrating linkage mapping and association analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2113.10.3390/ijms23042113Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Chiang KS, Liu HI, Bock CH. A discussion on disease severity index values. Part I: warning on inherent errors and suggestions to maximise accuracy. Ann Appl Biol. 2017;171:139–54. 10.1111/aab.12362.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Thepbandit W, Buensanteai N, Thumanu K, Siriwong S, Le Thanh T, Athinuwat D. Salicylic acid elicitor inhibiting Xanthomonas oryzae growth, motility, biofilm, polysaccharides production, and biochemical components during pathogenesis on rice. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2021;48:341–53.Search in Google Scholar

[24] He Z, Liu Y, Kim HJ, Tewolde H, Zhang H. Fourier transform infrared spectral features of plant biomass components during cotton organ development and their biological implications. J Cotton Res. 2022;5:11. 10.1186/s42397-022-00117-8.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Wang Y, Mostafa S, Zeng W, Jin B. Function and mechanism of jasmonic acid in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8568. 10.3390/ijms22168568.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Li N, Han X, Feng D, Yuan D, Huang L-J. Signaling crosstalk between salicylic acid and ethylene/jasmonate in plant defense: Do we understand what they are whispering? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:671.10.3390/ijms20030671Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Ruan J, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Yan J, Khurshid M, Weng W, et al. Jasmonic acid signaling pathway in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2479. 10.3390/ijms20102479.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Klessig DF, Choi HW, Dempsey DMA. Systemic acquired resistance and salicylic acid: Past, present, and future. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact®. 2018;31:871–88. 10.1094/mpmi-03-18-0067-cr.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Mehmood N, Saeed M, Zafarullah S, Hyder S, Rizvi ZF, Gondal AS, et al. Multifaceted impacts of plant-beneficial Pseudomonas spp. in managing various plant diseases and crop yield improvement. ACS Omega. 2023;8:22296–315. 10.1021/acsomega.3c00870.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Trouvelot S, Héloir MC, Poinssot B, Gauthier A, Paris F, Guillier C, et al. Carbohydrates in plant immunity and plant protection: Roles and potential application as foliar sprays. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:592. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00592.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Gravino M, Locci F, Tundo S, Cervone F, Savatin DV, De Lorenzo G. Immune responses induced by oligogalacturonides are differentially affected by AvrPto and loss of BAK1/BKK1 and PEPR1/PEPR2. Mol Plant Pathol. 2017;18:582–95. 10.1111/mpp.12419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Bishop PD, Ryan CA. [60] Plant cell wall polysaccharides that activate natural plant defenses. In Methods in enzymology. Vol. 138. London: Academic Press; 1987. p. 715–24.10.1016/0076-6879(87)38062-0Search in Google Scholar

[33] Kozieł E, Otulak-Kozieł K, Bujarski JJ. Plant cell wall as a key player during resistant and susceptible plant-virus interactions. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:656809. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.656809.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] McCann HC, Guttman DS. Evolution of the type III secretion system and its effectors in plant–microbe interactions. New Phytol. 2008;177:33–47. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02293.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Rezzonico F, Binder C, Défago G, Moënne-Loccoz Y. The type III secretion system of biocontrol Pseudomonas fluorescens KD targets the phytopathogenic Chromista Pythium ultimum and promotes cucumber protection. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact: MPMI. 2005;18:991–1001. 10.1094/mpmi-18-0991.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: Shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–14.10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Stringlis IA, Zamioudis C, Berendsen RL, Bakker PAHM, Pieterse CMJ. Type III secretion system of beneficial rhizobacteria Pseudomonas simiae WCS417 and Pseudomonas defensor WCS374. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1631. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01631.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Kvitko BH, Collmer A. Discovery of the Hrp type III secretion system in phytopathogenic bacteria: How investigation of hypersensitive cell death in plants led to a novel protein injector system and a world of inter-organismal molecular interactions within plant cells. Phytopathology®. 2023;113:626–36. 10.1094/phyto-08-22-0292-kd.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Grant M, Lamb C. Systemic immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:414–20.10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Fu ZQ, Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance: Turning local infection into global defense. Annu Rev plant Biol. 2013;64:839–63.10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105606Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Gruau C, Trotel-Aziz P, Villaume S, Rabenoelina F, Clément C, Baillieul F, et al. Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 triggers local and systemic immune response against Botrytis cinerea in grapevine. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact®. 2015;28:1117–29. 10.1094/mpmi-04-15-0092-r.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] German L, Yeshvekar R, Benitez-Alfonso Y. Callose metabolism and the regulation of cell walls and plasmodesmata during plant mutualistic and pathogenic interactions. Plant Cell Env. 2023;46:391–404. 10.1111/pce.14510.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Mason KN, Ekanayake G, Heese A. Staining and automated image quantification of callose in Arabidopsis cotyledons and leaves. Methods Cell Biol. 2020;160:181–99. 10.1016/bs.mcb.2020.05.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Pontiggia D, Benedetti M, Costantini S, De Lorenzo G, Cervone F. Dampening the DAMPs: How plants maintain the homeostasis of cell wall molecular patterns and avoid hyper-immunity. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:613259. 10.3389/fpls.2020.613259.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Malinovsky FG, Fangel JU, Willats WG. The role of the cell wall in plant immunity. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:178. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00178.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Lahlali R, Kumar S, Wang L, Forseille L, Sylvain N, Korbas M, et al. Cell wall biomolecular composition plays a potential role in the host type II resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:910. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00910.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Siriwong S, Thepbandit W, Hoang NH, Papathoti NK, Teeranitayatarn K, Saardngen T, et al. Identification of a chitooligosaccharide mechanism against bacterial leaf blight on rice by in vitro and in silico studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7990.10.3390/ijms22157990Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Bacete L, Mélida H, Miedes E, Molina A. Plant cell wall-mediated immunity: cell wall changes trigger disease resistance responses. Plant J. 2018;93:614–36. 10.1111/tpj.13807.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Marisol O-V, Emmanuel A-H, Irasema V-A, Miguel Ángel M-T. Plant cell wall polymers: Function, structure and biological activity of their derivatives. In: Ailton De Souza G, editor. Polymerization. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2012. p. Ch. 4.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Abdul Malik NA, Kumar IS, Nadarajah K. Elicitor and receptor molecules: Orchestrators of plant defense and immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:963. 10.3390/ijms21030963.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[51] Sénéchal F, Wattier C, Rustérucci C, Pelloux J. Homogalacturonan-modifying enzymes: Structure, expression, and roles in plants. J Exp Botany. 2014;65:5125–60. 10.1093/jxb/eru272.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Wan J, He M, Hou Q, Zou L, Yang Y, Wei Y, et al. Cell wall associated immunity in plants. Stress Biol. 2021;1:3. 10.1007/s44154-021-00003-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Benedetti M, Pontiggia D, Raggi S, Cheng Z, Scaloni F, Ferrari S, et al. Plant immunity triggered by engineered in vivo release of oligogalacturonides, damage-associated molecular patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:5533–8. 10.1073/pnas.1504154112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Gramegna G, Modesti V, Savatin DV, Sicilia F, Cervone F, De Lorenzo G. GRP-3 and KAPP, encoding interactors of WAK1, negatively affect defense responses induced by oligogalacturonides and local response to wounding. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:1715–29. 10.1093/jxb/erv563.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Davidsson P, Broberg M, Kariola T, Sipari N, Pirhonen M, Palva ET. Short oligogalacturonides induce pathogen resistance-associated gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:19. 10.1186/s12870-016-0959-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] Yu Y, Gui Y, Li Z, Jiang C, Guo J, Niu D. Induced systemic resistance for improving plant immunity by beneficial microbes. Plants (Basel, Switz). 2022;11:386. 10.3390/plants11030386.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Suresh P, Vellasamy S, Almaary KS, Dawoud TM, Elbadawi YB. Fluorescent pseudomonads (FPs) as a potential biocontrol and plant growth promoting agent associated with tomato rhizosphere. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2021;33:101423. 10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101423.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Wang Z, Mei X, Du M, Chen K, Jiang M, Wang K, et al. Potential modes of action of Pseudomonas fluorescens ZX during biocontrol of blue mold decay on postharvest citrus. J Sci Food Agric. 2020;100:744–54. 10.1002/jsfa.10079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Barahona E, Navazo A, Yousef-Coronado F, Aguirre de Cárcer D, Martínez-Granero F, et al. Efficient rhizosphere colonization by Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 mutants unable to form biofilms on abiotic surfaces. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:3185–95. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02291.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Park YS, Dutta S, Ann M, Raaijmakers J, Park K. Promotion of plant growth by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain SS101 via novel volatile organic compounds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;461. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions