Abstract

Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) – also called sorrel, Bissap or Karkadeh – is believed to be native to Africa. Research is needed to set a solid foundation for the development of roselle in the continent. Therefore, this article presents an analysis of the research landscape on roselle in Africa; it covers bibliographical metrics, the geography of the research, and the topics addressed in the scholarly literature about roselle. The systematic review drew upon 119 eligible articles identified through a search carried out on the Web of Science in March 2024. The research field is not well-established; the number of publications on roselle in Africa is limited, indicating an unstable and inconsistent interest. The research field is multidisciplinary but appears to focus more on biological sciences than social sciences and economics. The research geography is not balanced, with more than half of all studies on roselle in Africa conducted in just five countries, viz. Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Ghana, and Senegal. The content analysis suggests that roselle holds the potential to contribute to food and nutrition security and the well-being of the populations. It can not only contribute to agricultural development but also to addressing many challenges the continent faces. Research is needed to unlock its potential. Future research should pay more attention, inter alia, to the relationships between roselle and environmental issues (e.g. climate change), social and economic aspects (e.g. livelihoods), and agronomy (cf. fertilization, pest management, irrigation). Given that roselle is grown across Africa, collaboration among African countries should also be encouraged.

1 Introduction

Neglected and underutilized species (NUS) are widely acknowledged as valuable resources for promoting sustainable development and transitioning to sustainable and resilient agri-food systems [1]. Reports indicate that the promotion of NUS significantly contributes to the conservation of agro-biodiversity [2,3] as well as food and nutrition security [3,4,5,6,7]. Additionally, NUS are recognized for their role in climate change adaptation and mitigation [4,6], environmental integrity and ecosystem health [4,8], and human health [4,8]. Furthermore, the promotion of NUS is seen as beneficial in sustaining and enhancing rural livelihoods [3,9–11]. Mabhaudhi et al. [4] argued that given reports of their potential, there is a case for promoting NUS to address challenges such as increasing drought and water scarcity, food and nutrition insecurity, environmental degradation, and unemployment under climate change. Meanwhile, Mabhaudhi et al. [12] suggested that the promotion of NUS could contribute to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically SDGs 1 (No poverty), 2 (Zero hunger), 3 (Good health and wellbeing), and 15 (Life on land).

One such NUS is roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). It is a flowering herb or subshrub that can be either annual or perennial. Roselle is believed to be native to Africa, particularly West Africa; during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, it was introduced to Asia and the West Indies, where it has since become naturalized in many places [13,14]. It is known as Karkadeh in Arabic [15], rosella in Australia [16], Yakuwa by the Hausa people of northern Nigeria [17], Bissap in Wolof in Senegal [18], Wegda in the Mossi area in Burkina Faso [19], Florida Cranberry or Jamaica sorrel in the United States [20], Saril or Flor de Jamaica in Central America [21], and sorrel in many parts of the English-speaking Caribbean [14,22]. China and Thailand are the world’s leading roselle producers, with Sudan, Nigeria, Mexico, Egypt, Senegal, Tanzania, Mali, and Jamaica also being significant suppliers [23]. In 2020, the global roselle market was valued at $122.8 million, and it is expected to reach $252.6 million by 2030 [24].

All parts of the roselle (leaves, calyxes, and seeds) are used in human nutrition [25]. The calyces of roselle are used in a variety of beverages and drinks, whereas the leaves are consumed as a vegetable [26]. The leaves of roselle are rich in polyphenolic compounds [27–31], such as chlorogenic acid and flavonoids [32]. The flowers contain high amounts of anthocyanins [26–28,33–36], while the dried calyces contain various flavonoids [27,37,38] such as gossypetin, hibiscetine, and sabdaretine. Roselle seeds are a significant source of lipid-soluble antioxidants [39]. Therefore, roselle-sourced compounds have been used to produce different functional foods [40].

Different parts of the plant, such as the leaves and flowers/calyces, have been utilized in a variety of ways worldwide. Indeed, roselle has been used in food, animal feed, nutraceuticals, cosmeceuticals, and pharmaceuticals. It is utilized, inter alia, in the production of several food items, including jellies, jams, juices, wine, syrups, gelatine, cakes, ice creams, and so on [24]. The plant is also an important ingredient in the cuisine of various countries, such as the Philippines [41] and Vietnam [42]. In Africa, particularly the Sahel region, roselle is commonly used to prepare a sugary herbal tea that is sold on the streets and popular in social gatherings. The renowned Sudanese Karkade is a cold drink made by soaking dried roselle calyces [43,44]. In Nigeria, roselle is used to make a refreshing drink called Zobo [45] and to produce jam [46]. In India, the plant is primarily grown to produce bast fibre from its stems, which is used in cordage and as a substitute for jute in making burlap [47–49]. The red calyces of the plant are increasingly being used to produce colourings for food [50,51] and dye for textiles [33].

Roselle is commonly used in traditional medicine [27,52]. The plant is claimed to have analgesic, anti-cancer, antihypertensive, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antitussive, choleretic, diuretic, hepatoprotective, and immunomodulatory therapeutic properties [27,32,48]. In Indian folk medicine, it has been used as a mild laxative and diuretic [53]. Brazilians believe that the roots of roselle have stomachic, emollient, and resolutive properties [54]. Roselle has been used to manage different diseases such as hypertension [55–59], hyperglycaemia/diabetes [38,55,56,60–62], cardiovascular diseases [55,59], cancer [55,63], atherosclerosis [64,65], chronic kidney disease [66], and gastric ulcers [67]. McCalla and Smith [56] argued that “Sorrel positively treated diabetes, hypertension, and a multitude of other illnesses due to its antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory potential, chiefly via its anthocyanins.” According to a meta-analysis conducted in 2015 [68], sour tea made from roselle has been found to reduce blood pressure. However, a more recent meta-analysis concluded that there is currently insufficient evidence to prove that roselle is effective in lowering blood pressure in people with hypertension when compared to placebo [69]. Interestingly, roselle products have even been used against various influenza viruses, including COVID-19 [70].

Roselle (H. sabdariffa L.) is a crop species that has been neglected and underutilized. There is a need for research to be conducted on roselle, but it is unclear what the current state of research on the crop in Africa is. Earlier reviews on roselle have been either outdated or only partially covered the topic from geographical and thematic perspectives (Table 1). In addition, no one has conducted a combined bibliometric and content/topical analysis for the entire African continent. This indicates a clear research gap, as there has been no recent systematic review of roselle. Therefore, this systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of research on roselle in Africa. The article covers bibliographical metrics, the geography of the research strand, and the topics addressed in the scholarly literature about roselle.

Earlier reviews dealing partially with roselle in Africa

| Thematic focus | Publication date | Review type | Geographical coverage | Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologic effects of sorrel on biological systems (gastrointestinal, hematopoietic, integumentary, nervous, reproductive, skeletal, urinary) | January 2024 | Systematic review | Global | McCalla and Smith [56] |

| Contaminations of green leafy vegetables | April 2023 | Narrative review | Ghana | Atitsogbey et al. [71] |

| Extraction of red pigments | February 2023 | Narrative review | Global | Rizkiyah et al. [35] |

| Medicinal plants used to treat viral infections | 2023 | Systematic review | Sudan | Yagi and Yagi [70] |

| Bioactive compounds and immunomodulating potential of West African health-promoting foods | November 2022 | Narrative review | West Africa | Elegbeleye et al. [72] |

| African natural products used against gastric ulcers | October 2022 | Scoping/systematic review | Africa | Dinat et al. [67] |

| Effects of natural products on lung disorders | May 2022 | Narrative review | Global | Saadat et al. [73] |

| Medicinal plants against hypertension | June 2021 | Systematic review | Nigeria | Abdulazeez et al. [57] |

| Use in soft drink production | October 2020 | Narrative review | Global | Salami and Afolayan [74] |

| Application in Pito with functional properties | June 2020 | Narrative review | Ghana | Adadi and Kanwugu [40] |

| Pharmacological effects of organic acids from roselle | May 2020 | Narrative review | Global | Izquierdo-Vega et al. [27] |

| Pharmacology and toxicology of anti-diabetic plants | April 2018 | Narrative review | Gabon | Taika et al. [60] |

| Interactions between herbal remedies and drugs | 2017 | Narrative review | Africa | Ondieki et al. [75] |

| Commercial medicinal plants | December 2015 | Narrative review | Africa | Van Wyk [76] |

| Microbiology of fermented indigenous seeds used as condiments | May 2009 | Narrative review | Global | Parkouda et al. [77] |

| Composition and main uses | May 2009 | Narrative review | Global | Cisse et al. [26] |

2 Methods

This systematic review [78,79] draws upon a search performed on the Web of Science Core Collection on 20 March 2024. The search was performed using the following string: (“Hibiscus sabdariffa” OR “H. sabdariffa” OR roselle OR rosella OR sorrel OR bissap) AND (Africa OR Algeria OR Angola OR Benin OR Botswana OR “Burkina Faso” OR Burundi OR “Cabo Verde” OR “Cape Verde” OR Cameroon OR “Central African Republic” OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR “Côte d’Ivoire” OR “Ivory Coast” OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR “Equatorial Guinea” OR Eritrea OR Ethiopia OR Eswatini OR Gabon OR Gambia OR Ghana OR “Guinea-Bissau” OR Guinea OR Kenya OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Libya OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Mauritius OR Morocco OR Mozambique OR Namibia OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Rwanda OR “São Tomé and Príncipe” OR Senegal OR Seychelles OR “Sierra Leone” OR Somalia OR “South Africa” OR “South Sudan” OR Sudan OR Swaziland OR Tanzania OR Togo OR Tunisia OR Uganda OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe). The search returned 196 potentially eligible documents. The selection of the eligible documents was guided by the approach employed by El Bilali [80] and El Bilali et al. [81,82].

Table 2 describes the different stages of the selection process. In particular, the process considered three specific criteria for inclusion and eligibility: geographical scope (i.e. the document deals with Africa/an African country), thematic focus (i.e. the document addresses roselle), and document type (i.e. only original research articles, chapters, or conference papers were considered, while editorial materials as well as reviews were excluded). After reviewing the titles, three documents were excluded as they do not address African countries. Additionally, 39 documents were discarded after analysing the abstracts, not meeting at least one of the eligibility/inclusion criteria: 11 documents not addressing roselle, 25 not dealing with Africa/African countries, and 3 without abstracts. As for the geographical coverage, some articles refer to Papua New Guinea (not Guinea or Guinea-Bissau in Africa), Aspergillus niger – a fungus (not Niger country), Congo red dye (not Congo country), and Guinea pig (not Guinea country). Furthermore, “Sudan” is the name of a roselle cultivar that has been used in experiments in various countries (e.g. Mexico), while “Rosella” is also the name of a wheat cultivar. Concerning the thematic focus, some articles refer to the sheep sorrel weed (Rumex acetosella), Bacidia rosella – a lichen species, or Lippia rosella (Verbenaceae), not roselle. Finally, 35 documents were excluded after reviewing their full papers, including 16 reviews.

Process of the selection of the eligible documents on roselle to be included in the systematic review

| Selection stage | Number of potentially eligible articles | Selection stage description |

|---|---|---|

| Identification of articles on the Web of Science (WoS) | 196 | No duplicates |

| Screening of articles based on titles | 196 | Three documents were excluded because they deal with countries outside Africa, viz. Jamaica, Mexico, and the USA |

| Screening of articles based on abstracts | 193 | Thirty-nine documents were excluded:

|

| Scrutiny of full-texts | 154 | Thirty-five documents excluded:

|

| Inclusion in the systematic review | 119 | — |

The systematic review included a total of 119 documents (Table 3). These documents consisted of 113 journal articles and 6 proceeding papers. The detailed list of the selected articles along with their titles is reported in Table A1.

Selected documents dealing with research on roselle in Africa

| Year | Number of documents | References |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 3 | Almisbah et al. [83], Kobta et al. [84], Yagi et al. [34] |

| 2022 | 9 | Abou-Sreea et al. [85], Atwaa et al. [86], Banwo et al. [61], Benkhnigue et al. [87], Hafez et al. [88], Hanafy et al. [89], Maffo Tazoho et al. [90], Mohammed et al. [91], Saha et al. [92] |

| 2021 | 6 | Bayoï et al. [93], Bourqui et al. [94], Chukwu et al. [95], Idowu-Adebayo et al. [96], Keyata et al. [97], Naangmenyele et al. [98] |

| 2020 | 11 | Aboagye et al. [99], Ali et al. [100], Ayanda et al. [101], Azeez et al. [102], Bekoe et al. [103], Bothon et al. [104], Budiman et al. [105], Elkafrawy et al. [106], Ighodaro et al. [107], Olika Keyata et al. [108], Marcel et al. [109] |

| 2019 | 12 | Abdallah Mohammed Ahmed et al. [110], Alegbe et al. [62], Bakary et al. [111], Catarino et al. [112], Diallo et al. [113], Kane et al. [114], Kubuga et al. [115,116], Misihairabgwi et al. [117], Naeem et al. [118], Raghu et al. [119], Sunmonu and Bayo Lewu [120] |

| 2018 | 4 | Ifie et al. [121], Quansah et al. [122], Rasheed et al. [38], Seck et al. [123] |

| 2017 | 4 | Bayendi Loudit et al. [124], Nwachukwu et al. [125], Peter et al. [126], Sanon et al. [127] |

| 2016 | 3 | Amadou et al. [128], Ndiaye et al. [129], Suliman et al. [130] |

| 2015 | 10 | Aworh [131], Baoua et al. [132], Dawoud and Sauerborn [133], Eghosa et al. [134], Farag et al. [135], Icard-Vernière et al. [136], Nwachukwu et al. [137], Osman et al. [138], Oulai et al. [139], Salem et al. [140] |

| 2014 | 6 | Bakasso et al. [141], Hassan et al. [142], Mugisha et al. [143], Mwasiagi et al. [144], Ogunkunle et al. [145], Peter et al. [146] |

| 2013 | 7 | Agbobatinkpo et al. [147], Aletor et al. [148], Al-Shafei and El-Gendy [149], Asiimwe et al. [150], Fadl [151], Ondo et al. [152,153] |

| 2011 | 6 | AbouZid and Mohamed [154], Atta et al. [155], Azokpota et al. [156], Brévault et al. [157], Savadogo et al. [158], Yongabi et al. [159] |

| 2010 | 6 | Abdelghany et al. [160], Fadl [161], Fadl and El Sheikh [162], Morrison and Twumasi [163], Oyewole and Mera [164], Uvere et al. [165] |

| 2009 | 6 | Agbo et al. [166], Cisse et al. [167], El Tahir et al. [168], Juliani et al. [169], Nwafor and Ikenebomeh [170], Sarr et al. [58] |

| 2008 | 4 | Brévault et al. [171], Mohamadou et al. [172], Ojokoh et al. [173], Parkouda et al. [174] |

| 2007 | 9 | Abasse et al. [175], Avallone et al. [176], Chadha et al. [177], Diouf et al. [178], Mathieu and Meissa [52], Obadina and Oyewole [179], Olaleye [180], Ouoba et al. [181], Sowemimo et al. [182] |

| 2006 | 3 | Azokpota et al. [183], Gaafar et al. [184], Omemu et al. [185] |

| 2005 | 1 | Maiga et al. [186] |

| 2004 | 3 | Amusa [187], Fadl and Gebauer [188], Palé et al. [189] |

| 2003 | 1 | Alegbejo et al. [190] |

| 2002 | 1 | Wezel and Haigis [191] |

| 2001 | 1 | Amusa et al. [192] |

| 1995 | 1 | Khristova and Tissot [193] |

| 1993 | 1 | Khristova and Vergnet [194] |

| 1991 | 1 | Elfaki et al. [195] |

The examination of the selected documents was initiated by analysing the bibliographical metrics [80,81,196] and the geographical distribution of the research field in Africa [80,81]. After that, the selected records were scrutinized for a range of topics, which included agriculture subsectors [80,81], food chain stages [80,81,196], food security and nutrition [80,196,197], climate and ecosystem resilience [196], and livelihoods and socio-economic impacts [196].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Bibliometrics of research on roselle in Africa

Although it is widely admitted that roselle has its origin in Africa, particularly West Africa, the preliminary results suggest that Africa is marginal in the research field. Indeed, a search carried out on the same date (20 March 2024) on the WoS without specifying any geographical limitation (viz. [“Hibiscus sabdariffa” OR “H. sabdariffa” OR roselle OR rosella OR sorrel OR bissap]) returned 2,581 records. Considering that the search on roselle in Africa yielded 196 records, this implies that Africa represents only 7.59% of the global output of the research field.

Research on roselle is rather recent in Africa and the first WoS-indexed publication dates back to 1991 [195]. It started in Sudan [195] and continued to be so during the whole 90s of the last century [193,194]; the first publication focusing on another African country, namely Nigeria, dates back to 2001 [192].

The annual output of publications on roselle in Africa suggests that interest is unstable and inconsistent. Indeed, considering the period 1991–2023, the number of papers published annually ranged from nil in many years (viz. 2012, 2000, 1999, 1998, 1997, 1996, 1994, 1992) and just one in others (viz. 2005, 2003, 2002, 2001, 1995, 1993, 1991) to a peak of 12 articles in 2019. Only three articles dealing with research on roselle in Africa were published in 2023, which is quite alarming and might denote a decrease of interest in this research field. However, such a downward trend and low output in 2023 might also be due to difficult situations in some countries that have been leading research on roselle in Africa such as Sudan.

The top sources and journals (Figure 1) are the Journal of Ethnopharmacology (6 articles, 5.04%), the African Journal of Biotechnology and the Journal of Stored Products Research (4 articles, 3.36%, each), Acta Horticulturae, Food Research International, the International Journal of Food Microbiology, and the Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture (3 articles, 2.52%, each). Nevertheless, the 119 selected publications were published in 94 sources and journals, which suggests that there is no specific publication outlet for research on roselle in Africa.

Main journals and sources. Different colours indicate different journals, with numbers above journals indicating the number of articles for each. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

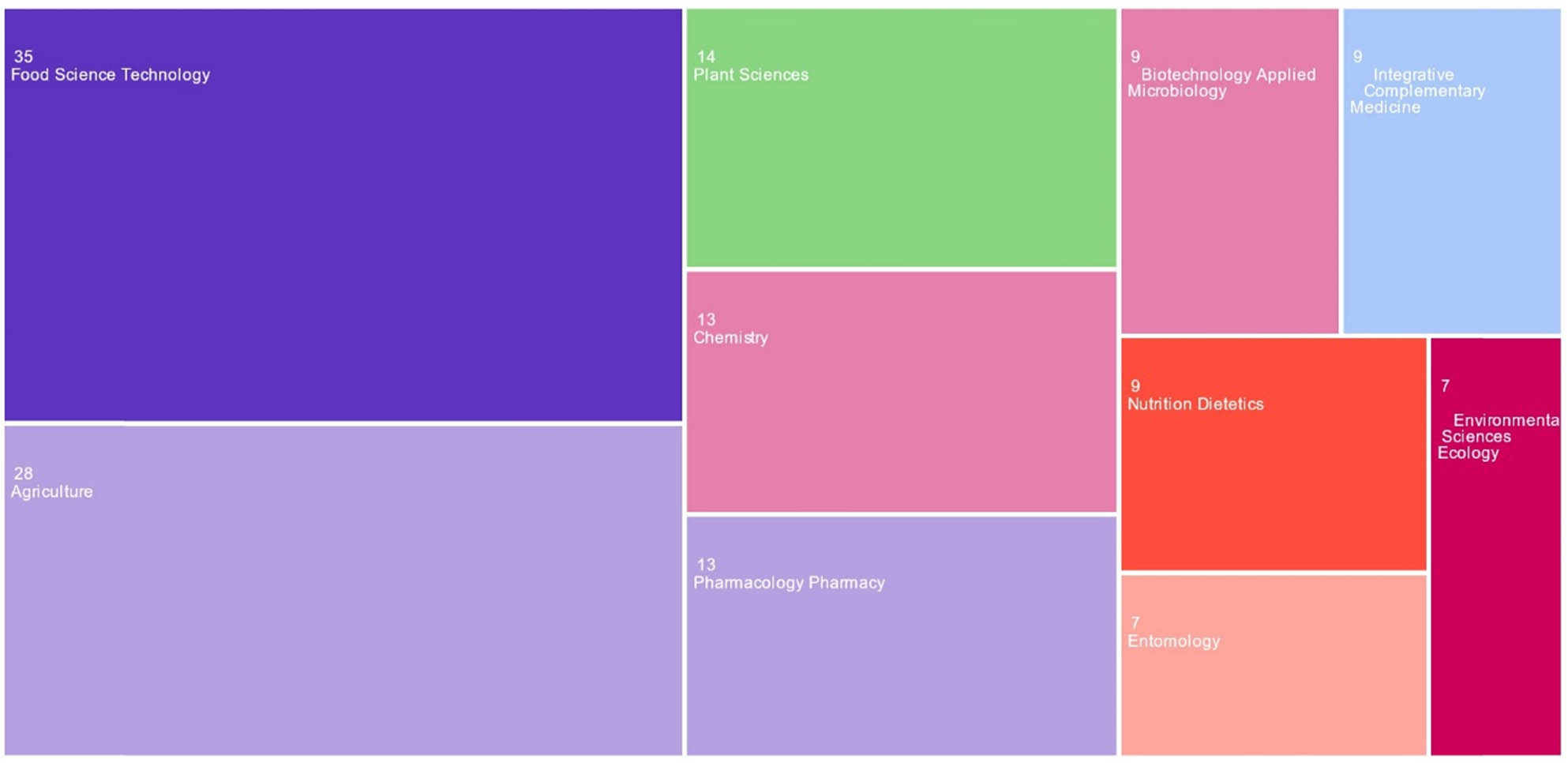

Most of the articles that are eligible are related to the research areas of Food science – Technology (35 articles, 29.41%), Agriculture (28 articles, 23.53%), Plant sciences (14 articles, 11.76%), Chemistry and Pharmacology – Pharmacy (13 articles, 10.92%, each), Biotechnology – Applied microbiology, Integrative complementary medicine, and Nutrition – Dietetics (9 articles, 7.56%, each) (Figure 2). However, it is interesting to note that the selected articles fall into 32 research areas (including Biochemistry – Molecular biology, Education – Educational research, Engineering, Entomology, Environmental sciences – Ecology, Forestry, Microbiology, Mycology, Public environmental occupational health, and Toxicology), which suggests that the research field is quite multidisciplinary. Notwithstanding, it can be postulated that the research field focuses on biological sciences (cf. agriculture, plant sciences, food science) while social sciences and economics are not adequately represented.

Main research areas. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

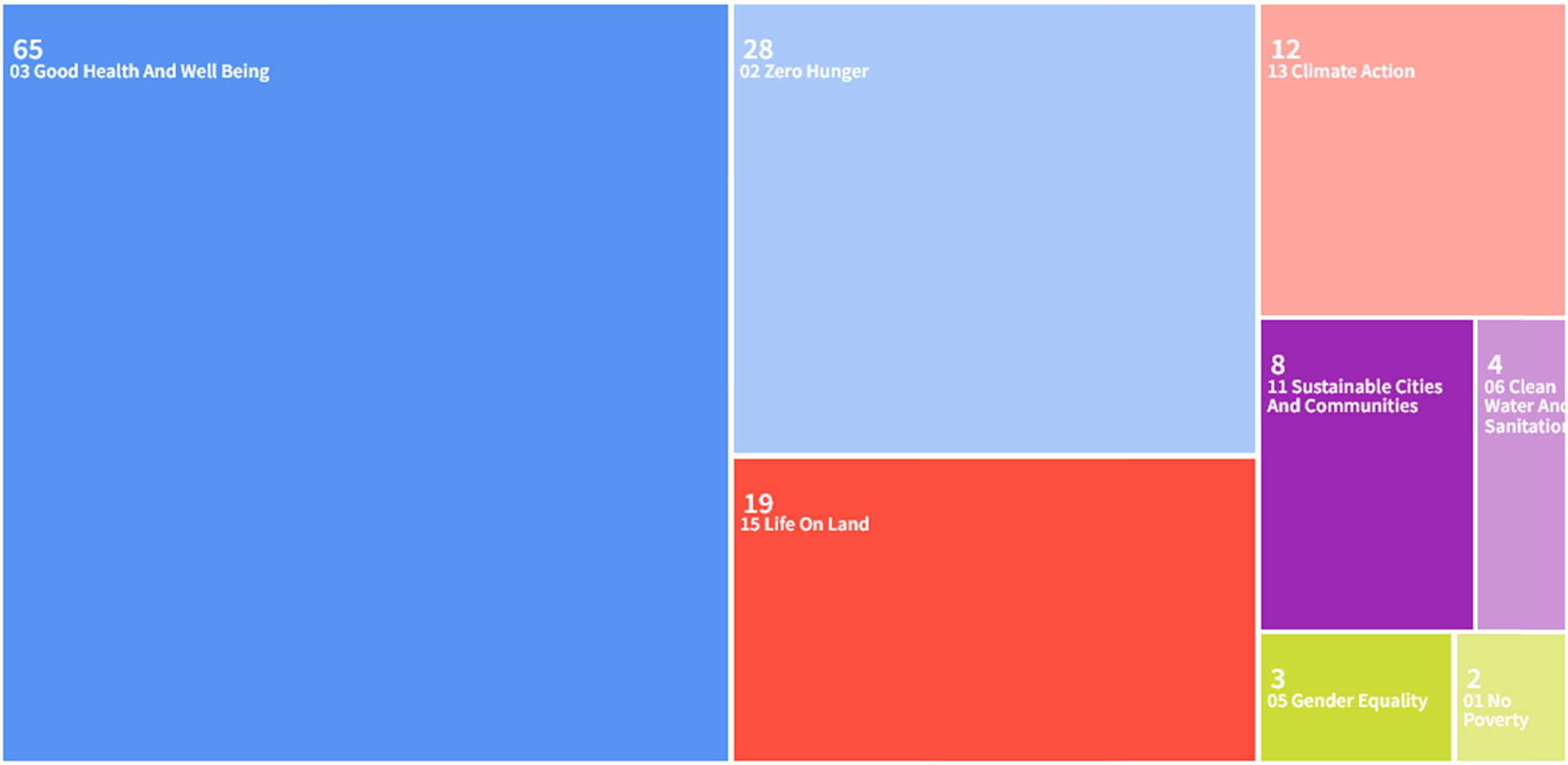

The fact that the field of research related to roselle encompasses various sectors and disciplines is reflected in the SDGs it addresses (Figure 3). The articles selected for this study on roselle focus on 8 SDGs, with the most prominent being SDG 03 – good health and wellbeing (65 documents, 54.62%), SDG 02 – zero hunger (28 documents, 23.53%), SDG 15 – life on land (19 documents, 15.97%), SDG 13 – climate action (12 documents, 10.08%), and SDG 11 – sustainable cities and communities (8 documents, 6.72%). Further marginal SDGs include SDG 06 – clean water and sanitation (4 documents, 3.36%), SDG 05 – gender equality (3 documents, 2.521%), and SDG 01 – no poverty (2 documents, 1.681%).

Main SDGs associated with the analysed literature. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

The analysis of bibliometrics reveals that Kamal Eldin Mohammed Fadl (Agricultural Research Corporation, Sudan), with four articles, and Paulin Azokpota (University Abomey-Calavi, Benin), with three articles, are the most prominent and productive authors in the research field (Figure 4). However, the research field lacks consistency since many authors have only one or two articles. Indeed, 483 scholars authored the 119 selected articles, but 481 scholars (so 99.48%) have only 1 or 2 articles on roselle. This indicates that even authors who work on roselle do so sporadically rather than systematically, which may be due to the absence of structured and long-term national or regional research programs/projects on roselle.

Prominent authors and scholars. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

The examination of affiliation institutions indicates that the most active research centre in this field is the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (16 documents, 13.45%). Further prominent African institutions are located in Benin (e.g. University of Abomey Calavi), Egypt (e.g. Cairo University, Zagazig University), Ghana (e.g. University for Development Studies, University of Ghana), Niger (e.g. National Institute of Agronomic Research in Niger – INRAN, University of Maradi), Nigeria (e.g. University of Nigeria, Federal University of Technology Akure, Obafemi Awolowo University, University of Benin, University of Agriculture Abeokuta, University of Ibadan), Senegal (e.g. University Gaston Berger, University Cheikh Anta Diop Dakar), and Sudan (e.g. University of Khartoum, Agricultural Research Corporation). However, some prominent research centres are located outside Africa, especially in France (e.g. Aix Marseille Université, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Agricultural Research Centre for International Development [CIRAD], Institut de Recherche pour le Développement [IRD], Université de Montpellier) and, to a lesser extent, Saudi Arabia (e.g. King Saud University). The 119 selected articles on roselle have been written by scholars who are affiliated with 202 research centres and universities (Figure 5).

Main affiliation institutions. CIRAD: Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (France), AGR RES CORP: Agricultural Research Corporation (Sudan). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

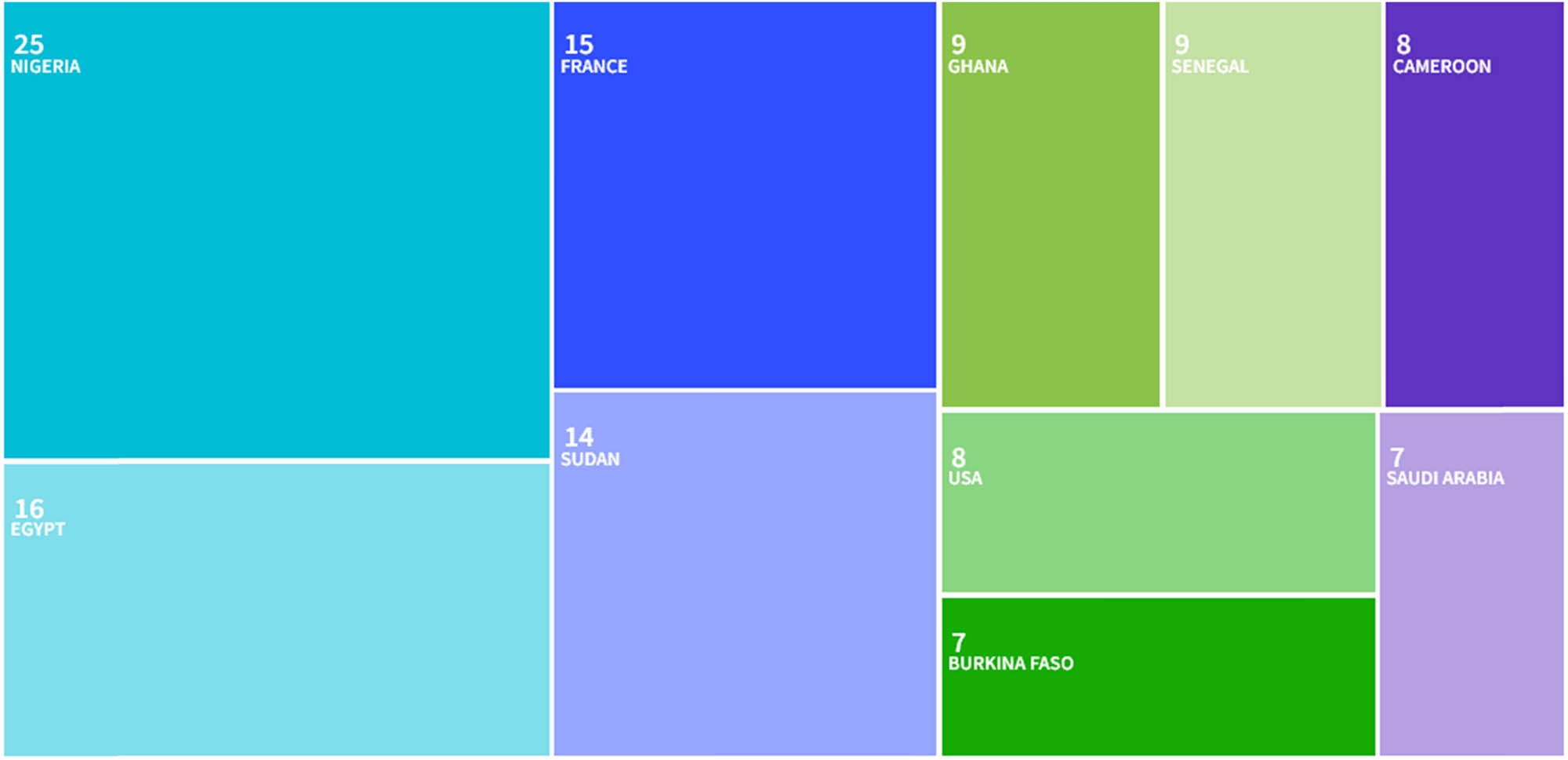

The findings regarding the affiliation institutions support those concerning the affiliation countries (Figure 6). The affiliation countries list is dominated by Nigeria (25 documents, 21.01%), Egypt (16 documents, 13.44%), France (15 documents, 12.60%), and Sudan (14 documents, 11.76%). Prominent African countries include also Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Niger, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda. However, many authors are affiliated with institutions located outside Africa in Europe (viz. Belgium, Denmark, England, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland), Asia (viz. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates), and Northern America (viz. USA).

Main affiliation countries. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from the WoS database.

The analysis suggests that the most important funding agencies are the European Union, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Grand Challenges Canada Stars in Global Health Round, the International Foundation for Science, and the Swedish Research Council. This implies that a large share of funding for research on roselle in Africa comes from abroad, especially from Europe and Northern America. This, in turn, denotes the weakness of domestic, African funding, which represents a risk and might hinder the development of long-term domestic research programs.

3.2 Geography of the research on roselle in Africa

There are significant variations among African countries in terms of research on roselle (Table 4). The majority of studies have been conducted in a few countries that dominate the list of affiliation countries, such as Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Ghana, and Senegal. In fact, more than half of all studies on roselle in Africa have been conducted in these five countries alone. More specifically, Nigeria has the highest number of studies on roselle (26 articles, accounting for 21.85% of the selected ones), followed by Egypt (15 articles, 12.60%), Sudan (14 articles, 11.76%), and Ghana and Senegal (9 articles, 7.56%, each). While the results for Nigeria and Egypt, which are large and populous countries, are somewhat expected, the performance of Ghana and Senegal may indicate a certain dynamism of their research systems. Meanwhile, the findings regarding Sudan might be explained by the fact that the country is a big producer of roselle (cf. Karkadeh) and the crop has a high socio-economic importance. Further prominent African countries include Burkina Faso and Cameroon (eight articles, each), Niger (six articles), and Benin (five articles). Conversely, many African countries have only been marginally or not at all covered in the research field. For instance, in several countries (viz. Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Mali, Morocco, Namibia, and South Africa), only one study on roselle was performed. Moreover, about two-thirds of African countries (33 out of 54 countries) – viz. Algeria, Angola, Botswana, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini/Swaziland, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, the Gambia, Togo, Tunisia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – have not been the subject of any research related to roselle, indicating a significant lack of research in this field.

Geography of research on roselle in Africa

| Country or region (articles number) | Documents |

|---|---|

| Benin (5) | Agbobatinkpo et al. [147], Azokpota et al. [183], Azokpota et al. [156], Bothon et al. [104], Kobta et al. [84] |

| Burkina Faso (8) | Avallone et al. [176], Bakary et al. [111], Icard-Vernière et al. [136], Ouoba et al. [181], Palé et al. [189], Parkouda et al. [174], Sanon et al. [127], Savadogo et al. [158] |

| Cameroon (8) | Bayoï et al. [93], Brévault et al. [171], Brévault et al. [157], Maffo Tazoho et al. [90], Marcel et al. [109], Mohamadou et al. [172], Saha et al. [92], Yongabi et al. [159] |

| Côte d’Ivoire/Ivory Coast (2) | Agbo et al. [166], Oulai et al. [139] |

| Egypt (15) | Abou-Sreea et al. [85], Al-Shafei and El-Gendy [149], AbouZid and Mohamed [154], Abdelghany et al. [160], Atwaa et al. [86], Elkafrawy et al. [106], Farag et al. [135], Hafez et al. [88], Hanafy et al. [89], Hassan et al. [142], Mohammed et al. [91], Naeem et al. [118], Osman et al. [138], Rasheed et al. [38], Salem et al. [140] |

| Ethiopia (2) | Olika Keyata et al. [108], Keyata et al. [97] |

| Gabon (3) | Bayendi Loudit et al. [124], Ondo et al. [152,153] |

| Ghana (9) | Aboagye et al. [99], Ali et al. [100], Bekoe et al. [103], Budiman et al. [105], Kubuga et al. [115], Kubuga et al. [116], Morrison and Twumasi [163], Naangmenyele et al. [98], Quansah et al. [122] |

| Guinea (1) | Diallo et al. [113] |

| Guinea-Bissau (1) | Catarino et al. [112] |

| Kenya (1) | Mwasiagi et al. [144] |

| Mali (1) | Maiga et al. [186] |

| Morocco (1) | Benkhnigue et al. [87] |

| Namibia (1) | Misihairabgwi et al. [117] |

| Niger (6) | Abasse et al. [175], Amadou et al. [128], Atta et al. [155], Bakasso et al. [141], Baoua et al. [132], Wezel and Haigis [191] |

| Nigeria (26) | Alegbe et al. [62], Alegbejo et al. [190], Aletor et al. [148], Amusa [187], Amusa et al. [192], Aworh [131], Ayanda et al. [101], Azeez et al. [102], Banwo et al. [61], Chukwu et al. [95], Eghosa et al. [134], Idowu-Adebayo et al. [96], Ifie et al. [121], Ighodaro et al. [107], Nwachukwu et al. [125], Nwachukwu et al. [137], Nwafor and Ikenebomeh [170], Obadina and Oyewole [179], Sowemimo et al. [182], Ogunkunle et al. [145], Ojokoh et al. [173], Olaleye [180], Omemu et al. [185], Oyewole and Mera [164], Uvere et al. [165], Sunmonu and Bayo Lewu [120] |

| Senegal (9) | Bourqui et al. [94], Cisse et al. [167], Diouf et al. [178], Juliani et al. [169], Kane et al. [114], Mathieu and Meissa [52], Ndiaye et al. [129], Sarr et al. [58], Seck et al. [123] |

| South Africa (1) | Raghu et al. [119] |

| Sudan (14) | Abdallah Mohammed Ahmed et al. [110], Almisbah et al. [83], Dawoud and Sauerborn [133], El Tahir et al. [168], Elfaki et al. [195], Fadl [161], Fadl [151], Fadl and El Sheikh [162], Fadl and Gebauer [188], Khristova and Tissot [193], Gaafar et al. [184], Khristova and Vergnet [194], Suliman et al. [130], Yagi et al. [34] |

| Tanzania (2) | Peter et al. [146], Peter et al. [126] |

| Uganda (2) | Mugisha et al. [143], Asiimwe et al. [150] |

| Africa (1) | Chadha et al. [177] |

In general, there is a lack of studies on roselle that cover the whole African continent or different African countries, with a few exceptions. For instance, Chadha et al. [177] analysed the impacts of the promotion of various indigenous vegetables (IVs) (including roselle but also amaranth, African eggplant, okra, Bambara groundnut, moringa, and cowpea) on food and nutrition security, health and income generation in Africa. Notwithstanding, this suggests a lack of collaboration among African countries on roselle.

3.3 Agriculture subsectors and food chain stages

Concerning agriculture subsectors, as anticipated, since H. sabdariffa is a crop/plant, almost all the selected articles deal with crop production. Indeed, there is only one exception; Suliman et al. [130] analysed the effect of a roselle seed-based diet on carcass characteristics and the chemical composition and quality of the meat of Baggara bulls in Sudan. This finding might suggest that roselle is not widely used in animal feeding or simply and merely that there is a gap in research on this topic.

Consumption is by far the most addressed stage of the food chain followed by processing and then production while the intermediate stages, such as marketing and distribution, are often neglected in the scholarly literature (Table 5). Interestingly, there are several studies on the processing of roselle. For instance, Parkouda et al. [174] described the production process Bikalga (based on alkaline fermented seeds of roselle) in Burkina Faso. Furthermore, many studies refer to different processed products of H. sabdariffa, including juices in Nigeria – Zobo [95,96,170,179,185], Senegal – Bissap [129], and Ghana – Sobolo [99]. Additionally, there are studies that investigate the use of roselle as an ingredient in various processed foods such as tomato paste [86], plantain powder [109], Babenda – Burkina Faso [111], Yanyanku – Benin [156], Bikalga – Burkina Faso [174,181], Mbuja – Cameroon [172], and Furundu – Sudan [195]. Keyata et al. [97] suggested that “calyces of Karkade can be used as a candidate to substitute synthetic antioxidants and food colorant in food, beverage and pharmaceutical industries because of their high antioxidant capacity, desired color and as a good source of phytochemicals.” Roselle has some antimicrobial characteristics that make it a potential food preservative [86]. Products from roselle go beyond food and include some industrial ones such as the production of bast fibre [144] and papermaking pulp [193]. Meanwhile, there are only a few papers that focus on the marketing of roselle and its products. In terms of consumption, roselle is used both as a food and a medicine/drug. The majority of articles in this category discuss the use of roselle in traditional, folk medicine to treat a variety of diseases and ailments. Some authors take a more holistic approach and examine different stages of the food chain. For instance, Catarino et al. [112] analysed the marketing and consumption of various leafy vegetables (viz. baobab, Bombax costatum, black sesame/vegetable sesame, amaranth, and roselle) in Guinea-Bissau. Cisse et al. [167] cast light on the production, processing/transformation, and consumption of Bissap/roselle in Senegal. Diouf et al. [178] map the commodity systems (cf. food chains) of four indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) (viz. roselle, cowpea, amaranth, and moringa) in Senegal, thus covering production, marketing, and consumption. Alegbejo et al. [190] explore the current status and future potential of the production and utilization/consumption of roselle in Nigeria.

Food chain stages

| Food chain stage* | Documents |

|---|---|

| Production | Abou-Sreea et al. [85], Amusa [187], Amusa et al. [192], Atta et al. [155], Aworh [131], Azeez et al. [102], Bayendi Loudit et al. [124], Budiman et al. [105], Chadha et al. [177], Cisse et al. [167], Dawoud and Sauerborn [133], Diouf et al. [178], El Tahir et al. [168], Fadl [151,161], Fadl and El Sheikh [162], Fadl and Gebauer [188], Alegbejo et al. [190], Gaafar et al. [184], Hanafy et al. [89], Hassan et al. [142], Ifie et al. [121], Juliani et al. [169], Kubuga et al. [115], Mohammed et al. [91], Ondo et al. [152,153], Wezel and Haigis [191] |

| Processing (including post-harvest storage) | Abdelghany et al. [160], Aboagye et al. [99], Agbobatinkpo et al. [147], Aletor et al. [148], Amadou et al. [128], Atwaa et al. [86], Aworh [131], Azokpota et al. [183], Azokpota et al. [156], Banwo et al. [61], Baoua et al. [132], Bayoï et al. [93], Bothon et al. [104], Cisse et al. [167], Idowu-Adebayo et al. [96], Juliani et al. [169], Khristova and Vergnet [194], Elfaki et al. [195], Khristova and Tissot [193], Maffo Tazoho et al. [90], Marcel et al. [109], Mohamadou et al. [172], Mwasiagi et al. [144], Naeem et al. [118], Ndiaye et al. [129], Nwafor and Ikenebomeh [170], Obadina and Oyewole [179], Avallone et al. [176], Ojokoh et al. [173], Omemu et al. [185], Oulai et al. [139], Ouoba et al. [181], Parkouda et al. [174], Sanon et al. [127], Savadogo et al. [158], Uvere et al. [165] |

| Marketing and distribution | Abasse et al. [175], Catarino et al. [112], Diouf et al. [178] |

| Consumption | Abasse et al. [175], Abdallah Mohammed Ahmed et al. [110], Aboagye et al. [99], AbouZid and Mohamed [154], Morrison and Twumasi [163], Agbo et al. [166], Agbobatinkpo et al. [147], Alegbe et al. [62], Alegbejo et al. [190], Aletor et al. [148], Ali et al. [100], Al-Shafei and El-Gendy [149], Asiimwe et al. [150], Avallone et al. [176], Ayanda et al. [101], Bakary et al. [111], Banwo et al. [61], Bayoï et al. [93], Bekoe et al. [103], Benkhnigue et al. [87], Bourqui et al. [94], Catarino et al. [112], Chadha et al. [177], Chukwu et al. [95], Cisse et al. [167], Diallo et al. [113], Diouf et al. [178], Eghosa et al. [134], Elkafrawy et al. [106], Icard-Vernière et al. [136], Idowu-Adebayo et al. [96], Ighodaro et al. [107], Kobta et al. [84], Kubuga et al. [115], Kubuga et al. [116], Maiga et al. [186], Mathieu and Meissa [52], Misihairabgwi et al. [117], Mugisha et al. [143], Naangmenyele et al. [98], Nwachukwu et al. [125,137], Ogunkunle et al. [145], Olaleye [180], Ondo et al. [153], Osman et al. [138], Oulai et al. [139], Peter et al. [126,146], Quansah et al. [122], Raghu et al. [119], Rasheed et al. [38], Saha et al. [92], Sarr et al. [58], Seck et al. [123], Sowemimo et al. [182], Yagi et al. [34] |

*Several documents address various stages of the food chain.

Roselle has been cultivated in different agricultural systems, which include horticulture [124], such as monocropping or intercropping, and agroforestry. Roselle has been used in intercropping with Acacia senegal in Sudan [151,161,168,184,188], cluster bean in Egypt [91], and millet in Niger [191]. Meanwhile, roselle has been the subject of research in agroforestry, especially in Sudan [151,161,162,168,184,188]. It has even been successfully used in container gardening in northern Ghana to combat micronutrient deficiencies in young children and mothers during the lean season [115]. This suggests that the crop is versatile and can easily adapt to various environments and agricultural systems.

In terms of production, only a few studies deal with fertilization and pest management, while irrigation seems completely overlooked. The studies analysing pest management deal with various issues such as bruchids on roselle seeds in Burkina Faso [127] and Niger [128,132], root rot and vascular wilt diseases in Egypt [142], and foliar blight in Nigeria [187,192]. Bayendi Loudit et al. [124] shed light on the practices of farmers in peri-urban gardening in Gabon (Libreville and Owendo); they found that the most important pests are aphids and beetles. While some studies focus on managing roselle pests and diseases, others explore the use of roselle-based products to control various plant pests. In Africa, extracts from different parts of the roselle plant have been utilized to manage diverse pests and diseases. Notable pests and diseases studied include sugar beet crown gall (caused by Agrobacterium tumefaciens bacterium) in Egypt [88]. Dawoud and Sauerborn [133] used roselle to induce the suicidal germination of the parasitic Striga weed. Only a few articles deal with the fertilization of roselle and soil fertility management in relation to the crop. For instance, Oyewole and Mera [164] analysed the response of roselle to different rates of inorganic and farmyard fertilizers in Nigeria. Wezel and Haigis [191] analysed fallow cultivation systems and their impacts on soil fertility in Niger; they refer to intercropping where roselle is used by some farmers. Foliar applications can be used for fertilization but also to mitigate some abiotic stresses such as salinity [85] and heat [89]. For instance, Abou-Sreea et al. [85] found that the foliar application of potassium silicate (KSi) and the extract of Aloe saponaria (Ae) reduces the stressful salinity impacts on the development, yield, and biochemical features of roselle plants in Egypt. Hanafy et al. [89] found that the treatment with salicylic acid and blue-green algae extract mitigates heat stress and decreases the negative effects of high temperatures on the growth of roselle in Siwa Oasis (Egypt).

The selected studies address different parts of roselle including flowers/calyces, leaves, and seeds (Table A2). The focus of the studies determines which part is studied. Leaves are mainly considered in studies dealing with roselle as a leafy vegetable. Meanwhile, studies dealing with the production of juices and the analyses of their features and characteristics focus on flowers and calyces. Seeds are mainly used in condiments. Meanwhile, both leaves and calyces are used in traditional medicine. However, some articles consider the whole roselle plant without distinguishing between its different parts when dealing with agronomic aspects. A few studies simultaneously examine different parts of roselle. For instance, Benkhnigue et al. [87] argued that both leafy stems and seeds of roselle are used against anaemia in Morocco. Keyata et al. [97] investigated the phytochemical contents, functional properties, and antioxidant activity of calyces and seeds of Karkade/roselle in Ethiopia.

3.4 Climate and ecosystem resilience

Only a very few articles deal with the potential that roselle has to contribute towards resolving numerous environmental issues and challenges that Africa faces, including climate change, land degradation, desertification, and water and soil pollution.

Climate change and variability are marginal topics in the scholarly literature on roselle in Africa. The production of biofuel/biodiesel from roselle demonstrates that the plant can contribute to the efforts to mitigate climate change. Bothon et al. [104] analysed the biodiesel potential of oils from the seeds of red and green phenotypes of roselle in Benin and concluded that both oils, which are in line with the US and European Union’s standards, could be used as fuel oil after their transesterification. Meanwhile, the use of usher wood and stems of roselle for the production of charcoal in Sudan [194] might represent a way to valorize the crop and its by-products, and promote recycling, but it does not help in mitigating the greenhouse gas emissions, so climate change.

Also, the role of roselle in addressing land degradation and desertification is a marginal topic in the existing literature. However, its use in agroforestry systems [151,161,162,168,184,188] might be useful in many African countries. Roselle has the potential to be a valuable asset in marginal agroecosystems. Treatments tested on roselle to mitigate the effects of salinity [85] and heat [89] raise hope about the possibility of cultivating roselle in marginal, harsh environments such as saline soils and hot arid areas.

A dearth of studies deals with the effectiveness of roselle in addressing water and soil pollution. Almisbah et al. [83] suggested that phytochemicals contained in the extract of roselle have the potential of reducing and capping copper (Cu), thus being useful in a procedure for the treatment of wastewater that was tested in the Soba sewage treatment plant (Sudan). Moreover, the fact that roselle can absorb/adsorb high concentrations of heavy metals [98,102] calls for caution regarding food safety but might make it a good candidate plant for the remediation of polluted soils (cf. phytoremediation) [102]. However, it is important to pay attention to the toxicity of heavy metals to plants such as roselle that seem not to tolerate high concentrations of heavy metals [102]. As for water treatment, Yongabi et al. [159] found that methanol extracts from seeds of moringa (Moringa oleifera), Jatropha curcas, and the calyces of roselle drastically reduced water turbidity in Cameroon and concluded that “Plant materials can be used as phytocoagulants and phytodisinfectants in treating turbid water and can be applied in wastewater treatment” (p. 628).

3.5 Food and nutrition security

The scholarly literature suggests that roselle has the potential to play an important role in ensuring food and nutrition security in Africa by increasing food availability, improving food access, enhancing food utilization, and ensuring stability.

Concerning food availability, the topic is marginal in the literature on roselle in Africa. However, the few available studies suggest that roselle is becoming an increasingly crucial source of food for households in Africa. Indeed, some studies show that the cultivation and use of roselle are increasing across Africa such as in Nigeria [190], Senegal [167,178], and Guinea-Bissau [112]. Referring to different leafy vegetables (including roselle), Catarino et al. [112] argued that “Although price and availability vary among the leafy vegetables analysed, these traditional foods appear to be a good dietary component that can contribute to food security in Guinea-Bissau and in other West African countries, as these species are widely distributed in this region.” The availability of roselle and its products depends on yield. In this respect, following their study of the variability of roselle yield in Niamey (Niger), Atta et al. [155] concluded that “Ecotypes with higher calyx yield had lower hundred seed weight and shorter plants” (p. 1371) while highlighting the potential to increase calyx yield through selection and breeding programs.

Research on roselle in Africa has paid little attention to food access, but studies indicate that households that have access to roselle have improved food and nutrition security. This is particularly true for the poor; indeed, referring to IVs, Chadha et al. [177] point out that “poor and rural households rely on IVs as a source of micronutrients” (p. 253). The easiness of cultivating roselle, even in containers [115], makes it a valuable asset in improving access of the poor to healthy and nutritious foods. This is confirmed by the fact that roselle has been produced in urban and peri-urban areas of some countries such as Gabon [124,152], Niger [175], and Ghana [122], thus allowing urban populations to have easy physical access to fresh (leafy) vegetables.

Most of the articles selected to discuss food security in relation to roselle deal with its role in nutrition, thus focusing on food utilization. Roselle is a leafy vegetable that plays an important role in the diet of numerous households in different African countries such as Niger [175], Guinea-Bissau [112], Burkina Faso [136], Ghana [122], and Ivory Coast [166]. Roselle is a valuable source of minerals, vitamins, and bioactive compounds, which makes it very nutritious. It represents a valuable source of micronutrients such as iron [92,110,115,116,126,136,153,165], zinc [136,153,165], vitamin A [136], and iodine [115], making it a valuable alley to combat micronutrient deficiencies [115,116,136,165,176]. Referring to the use of Folere (H. sabdariffa), M. oleifera, Solanum aethiopicum (eggplant) to enrich porridges based on local foods (e.g. maize) in Cameroun, Saha et al. [92] concluded that “moringa, folere, and eggplant leaves can be used in functional foods to alleviate iron deficiency among children aged 6–23 months.” However, the nutritional value of roselle leaves and calyces can be affected by various factors such as varieties/cultivars [34,135], genotypes [110], environmental conditions [110], season [121,169], and processing and preparation method [38,173].

The use of roselle in fortification and supplementation programs in many African countries is due to its interesting nutritional profile [34,97,108,110,121,169]. Across Africa, roselle-based products have been tested and/or used for the enrichment of nutrients in various products. It has also been used as a food supplement in different food products, including porridges made from various cereals such as maize [92], snacks based on maize (Kokoro) or groundnut (Kulikuli) [148], maize-Bambara groundnut foods [165], and condiments (Afitin, Iru, and Sonru, based on African locust bean, Parkia biglobosa) [183]. Meanwhile, further studies also show the opportunity of enriching roselle-based products to improve their nutritional value and health-supportive features, e.g. Zobo drink with turmeric (Curcuma longa) in Nigeria [96].

Ensuring food safety is crucial for making optimal use of food. Some scholars have highlighted that the leaves and calyces of roselle, as well as its products (e.g. juices), may contain heavy metals [84,98,101–103,111,152,153,186], microbial contaminants [99,103,117,122,129], including mycotoxins [117], and pesticides [84,111], such as pyrethroids and glyphosate, which could pose a potential threat to human health and well-being. Studies highlighting such health risks have been carried out in Benin [84], Ghana [98,99,122], Nigeria [101], Burkina Faso [111], Namibia [117], Senegal [129], and Gabon [153]. However, after investigating a polyherbal formulation (mainly composed of roselle and Aloe barbadensis) commonly used in Ibadan (Nigeria), Ighodaro et al. [107] underline the “high safety for the investigated polyherbal mixture and thus supports its usage in folklore medicine” (p. 1393). Peter et al. [126], while confirming the safety of the aqueous extract of roselle for human consumption, found that the extract did not significantly improve the iron status in anaemic adults in Mkuranga district, a malaria endemic region in Tanzania. Anyway, the accumulation of some elements in plants might not always be negative and can even result beneficial; in this respect, following their analysis of the accumulation of soil-borne trace metals (viz. aluminium – Al, iron, manganese – Mn, and zinc – Zn) in plants cultivated in Moanda region (Gabon), Ondo et al. [153] concluded that “Al and Mn accumulation in food crops cultivated in the Moanda area of Gabon may represent a health hazard. However, the high levels of Zn in vegetables could be a pathway for Zn supplementation in human nutrition to reduce Zn deficiency in developing countries” (p. 2549). Similarly, in their investigation of the impact of urban gardening on metal transfer to vegetables (including roselle) in Libreville (Gabon), Ondo et al. [152] argued that “Amaranth and Roselle were vegetables that preferentially concentrated metals in their leaves and could, therefore, be used for metal supplementation in the food chain” (p. 1045). Access to clean water is crucial for food safety, since water is used in food preparation and cooking. Roselle has shown potential in water purification in countries such as Cameroon [159].

The articles selected discuss various claims of health benefits of roselle. These benefits are related to numerous diseases such as anaemia, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and kidney disease (Table 6). However, most studies focus on hypertension, anaemia, and diabetes. Alegbe et al. [62] argued that the consumption of roselle-based Zobo drink “could improve diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, metabolic syndrome, and liver disease.” The results of the study of Olaleye [180] support the use of roselle “in the treatment of diseases like abscesses, bilious conditions, cancer and coughs in traditional medicine and also … the possibility of isolating antibacterial and anticancer agents from Hibiscus sabdariffa” (p. 9). Some studies suggest that roselle has been used to manage opportunistic infections and diseases connected to HIV/AIDS in western Uganda [143,150]. Roselle is also included as an ingredient in many herbal formulations, e.g. antimalarial and haematinic ones in Ogbomoso (Nigeria) [145]. The health benefits of roselle are due, among others, to its antioxidant activity [34,61,97,120,121,163,189]. The health-protective properties of roselle (cf. phenolic compounds with high antioxidant functions) can be exploited in the design of functional foods and nutraceuticals [61]. Interestingly, some studies suggest that roselle products can also affect reproductive development [95] and seem to have beneficial effects during pregnancy [134] and breastfeeding [100]. However, caution is advised because the pharmacological applications of various bioactive phytochemicals from roselle have largely been based on anecdotes (cf. ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological surveys), and the mechanistic details governing their activities have been rather elusive. Therefore, further studies (especially randomized clinical trials) are necessary to provide the necessary strong and robust evidence supporting the use of roselle and its products in medicine.

Claims of health benefits related to roselle

| Document | Country | Concerned disease(s) | Source of data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benkhnigue et al. [87] | Morocco | Anaemia | Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological survey |

| Banwo et al. [61] | Nigeria | Diabetes | In vitro assays |

| Bourqui et al. [94] | Senegal | Hypertension | Clinical trial |

| Elkafrawy et al. [106] | Egypt | Hypertension | Clinical trial |

| Alegbe et al. [62] | Nigeria | Diabetes | Laboratory test |

| Sunmonu and Bayo Lewu [120] | Nigeria | Diabetes | Laboratory test |

| Diallo et al. [113] | Guinea | Hypertension | Ethnobotanical survey |

| Seck et al. [123] | Senegal | Hypertension | Clinical trial |

| Peter et al. [126] | Tanzania | Anaemia | Clinical trial |

| Nwachukwu et al. [125] | Nigeria | Renal function (in subjects with hypertension) | Clinical trial |

| Osman et al. [138] | Egypt | Kidney disease | Cross-sectional survey |

| Nwachukwu et al. [137] | Nigeria | Hypertension | Clinical trial |

| Peter et al. [146] | Tanzania | Anaemia | Ethno-medicinal survey |

| Al-Shafei and El-Gendy [149] | Egypt | Hypertension | Clinical trial |

| AbouZid and Mohamed [154] | Egypt | Hypertension | Ethnobotanical survey |

| Cardiovascular diseases | |||

| Sarr et al. [58] | Senegal | Hypertension | Laboratory test |

| Cardiovascular diseases | |||

| Sowemimo et al. [182] | Nigeria | Cancer | Laboratory test |

| Olaleye [180] | Nigeria | Various diseases (e.g. cancer) | Laboratory test |

No article specifically addresses the stability dimension of food security. However, it is worth mentioning the important role that roselle plays in feeding the population during the lean season [115]. In addition to this, the use of roselle in agroforestry systems [151,161,162,168,184,188] can help maintain food production stability in the face of climate change.

3.6 Socio-economic impacts and livelihoods

The analysis suggests that social and economic aspects are marginal in the literature on roselle in Africa. Considering the results of the bibliometric analysis, this was somehow expected. Indeed, the analysis of the research areas showed that the research field focuses on biological and environmental sciences while social sciences and economics are not adequately covered. Similarly, the scrutiny of the SDGs related to the scholarly literature on roselle in Africa has shown that SDGs dealing with socio-economic aspects (e.g. SDG 01 – No poverty and SDG 05 – Gender equality) are marginal. Some studies indicate that roselle can be beneficial for small-scale farmers in terms of income generation and rural livelihoods. However, these studies are only a few and are limited in scope.

Roselle is considered an essential source of income and livelihood strategy in several African countries. Indeed, some scholars refer to roselle as an economically important crop in different African countries such as Niger [141,155,175] and Senegal [178]. Chadha et al. [177] suggested that promoting IVs, including roselle, is beneficial not only for food security and health but also for generating income in Africa. Abasse et al. [175] point out that ILVs, including roselle, play an important role in the daily diets of populations and the economies of rural and urban areas in Niger in general and Maradi, Dosso, and Tillabery regions in particular. ILVs also represent an important source of income for farmers in Niger; the authors argued that “In Maradi and Dosso farmers involved in ILVs production obtain 20–30% of their annual income from the sales of ILVs. In Tillabery this value is higher than 50%” (p. 35). Furthermore, roselle might offer some opportunities for the diversification of income-generating activities through processing such as the production of charcoal [194].

The usefulness of roselle for low-income, poor individuals is notable. It provides a source of income [177,178] and can help compensate for the inadequate level of services, such as healthcare [150]. IVs, such as roselle, are a good source of income for African small-scale farmers [177]. The crop is widely grown by smallholders and resource-poor farmers in Nigeria [190]. The plant’s significance and versatility make it a fitting component of developmental programs promoting gardening [115].

According to certain research, roselle may have a role in promoting gender empowerment. Cisse et al. [167] reported that the production of roselle, as well as its transformation (cf. production of Bissap drink) in Senegal, is mainly managed by women and their groups and associations. Roselle has particular importance for women. It is among the herbs utilized to improve breastmilk production [100] and also improves iron status among women in childbearing age and prevents stunting in their toddlers [116].

The creation of roselle value chains can be a valuable tool to tackle various challenges and promote sustainable rural development in Africa. Aworh [131] argued that the value-added processing of underutilized IVs (such as roselle) can enhance small-scale farmers’ income, promote food security, and contribute to sustainable rural development in Nigeria.

4 Conclusions

This seems the first all-encompassing and methodical review of research on roselle in Africa. It presents a summary of both the bibliometric indicators and the subjects explored in the academic literature.

The research field on roselle is not well-established in Africa. There is limited interest, and the research field lacks consistency. Authors mostly come from institutions outside Africa, with funding mainly from Europe and North America. Most studies are concentrated in a few countries, while 33 out of 54 African countries have not been studied, indicating a significant research gap and lack of collaboration among African countries. The selected articles mainly focus on crop production, and consumption and processing stages. Roselle is used for both food and medicinal purposes. It is adapted to different agricultural systems and environments, but there’s limited agronomic research on fertilization, pest management, and irrigation. Some articles discuss how roselle could help with environmental issues in Africa, including climate change, land degradation, and water and soil pollution. It could also contribute to food and nutrition security. However, most articles only focus on its nutritional benefits and overlook its role in food availability, access, and stability. Roselle is a popular leafy vegetable in African households and is a good source of micronutrients. It is used in fortification and supplementation programs but may contain contaminants. Health claims about roselle include benefits for diseases like anaemia, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and hypertension. The literature on roselle in Africa tends to overlook social and economic aspects, but some studies suggest it could benefit small-scale farmers in terms of income generation, rural livelihoods, and gender empowerment.

The article shows the potential of roselle but also suggests that the current state of research on the crop is unsatisfactory, and there are several research gaps. Therefore, future research should pay more attention to the relationships between roselle and environmental issues such as climate change, land degradation, desertification, and water and soil pollution. Furthermore, there is a need to further elucidate the contribution of roselle to food and nutrition security with particular attention to availability, access and stability dimensions. Another domain that deserves more attention is that related to social and economic aspects and a deeper and more articulated investigation on the contribution of roselle to livelihoods and poverty reduction is needed. The latter can also provide strong evidence to invest in cooperation and development projects and programs aiming at the development of roselle and its value chain. Moreover, further studies (especially randomized clinical trials) are necessary to provide the necessary strong and robust evidence supporting the use of roselle and its products in medicine. This can open up new opportunities for the valorization of roselle and its products in functional foods, nutraceuticals, food supplements, and drugs. However, one of the most important priorities in the research field remains agronomy, as the review suggests a gap in research in agronomic practices (cf. fertilization, pest management, irrigation) regarding roselle. Given that roselle is grown across Africa, also collaboration and exchange of knowledge and expertise between African countries, south-south cooperation with Asia, and south-north research projects should be encouraged to strengthen the agricultural knowledge and innovation system (AKIS) in Africa, especially Western Africa.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the project SUSTLIVES (SUSTaining and improving local crop patrimony in Burkina Faso and Niger for better LIVes and EcoSystems – https://www.sustlives.eu).

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the DeSIRA initiative (Development Smart Innovation through Research in Agriculture) of the European Union (contribution agreement FOOD/2021/422-681).

-

Author contributions: The author confirms the sole responsibility for the conception of the study, presented results and manuscript preparation. Conceptualization, HEB; methodology, HEB; software, HEB; validation, HEB; formal analysis, HEB; investigation, HEB; resources, HEB; data curation, HEB; writing – original draft preparation, HEB; writing – review and editing, HEB; visualization, HEB; project administration, HEB; funding acquisition, HEB.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Appendix

List of selected articles with their titles

| Article | Title |

|---|---|

| Yagi et al. [34] | Comparative study on the chemical profile, antioxidant activity, and enzyme inhibition capacity of red and white Hibiscus sabdariffa variety calyces |

| Almisbah et al. [83] | Green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles using Hibiscus sabdariffa L. extract to treat wastewater in Soba Sewage Treatment Plant, Sudan |

| Kobta et al. [84] | Evaluation of the contamination of edible leaves in the cotton-growing zone of Kerou and Pehunco (Benin) by metallic trace elements, pyrethroids and glyphosate |

| Saha et al. [92] | Nutritional quality of three iron-rich porridges blended with Moringa oleifera, Hibiscus sabdariffa, and Solanum aethiopicum to combat iron deficiency anemia among children |

| Atwaa et al. [86] | Antimicrobial activity of some plant extracts and their applications in homemade tomato paste and pasteurized cow milk as natural preservatives |

| Mohammed et al. [91] | Maximizing land utilization efficiency and competitive indices of roselle and cluster bean plants by intercropping pattern and foliar spray with lithovit |

| Maffo Tazoho et al. [90] | Survey on roselle juice (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) preparation in the West Region of Cameroon: An evaluation of the effect of different formulations of this juice on some biological properties in rats |

| Benkhnigue et al. [87] | Ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological study of medicinal plants used in the treatment of anemia in the region of Haouz-Rehamna (Morocco) |

| Abou-Sreea et al. [85] | Improvement of selected morphological, physiological, and biochemical parameters of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) grown under different salinity levels using potassium silicate and Aloe saponaria extract |

| Banwo et al. [61] | Phenolics-linked antioxidant and anti-hyperglycemic properties of edible roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn.) calyces targeting type 2 diabetes nutraceutical benefits in vitro |

| Hafez et al. [88] | Molecular identification of new races of Agrobacterium spp using genomic sequencing-based on 16S Primers: Screening of biological agents and nano-silver which mitigated the microbe in vitro |

| Hanafy et al. [89] | Using of blue green algae extract and salicylic acid to mitigate heat stress on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) plant under Siwa Oasis conditions |

| Bayoï et al. [93] | In vitro bioactive properties of the tamarind (Tamarindus indica) leaf extracts and its application for preservation at room temperature of an indigenous roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa)-based drink |

| Chukwu et al. [95] | Effect of perinatal administration of flavonoid-rich extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa to feed-restricted rats, on offspring postnatal growth and reproductive development |

| Naangmenyele et al. [98] | Levels and potential health risk of elements in two IVs from Golinga irrigation farms in the Northern Region of Ghana |

| Idowu-Adebayo et al. [96] | Enriching street-vended zobo (Hibiscus sabdariffa) drink with turmeric (C. longa) to increase its health-supporting properties |

| Keyata et al. [97] | Phytochemical contents, antioxidant activity and functional properties of Raphanus sativus L., Eruca sativa L. and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. growing in Ethiopia |

| Ayanda et al. [101] | Trace metal toxicity in some food items in three major markets in Ado-Odo/Ota LGA, Ogun State, Nigeria and associated health implications |

| Ali et al. [100] | Special foods and local herbs used to enhance breastmilk production in Ghana: rate of use and beliefs of efficacy |

| Olika Keyata et al. [108] | Proximate, mineral, and anti-nutrient compositions of underutilized plants of Ethiopia: Figl (Raphanus sativus L.), Girgir (Eruca sativa L.) and Karkade (Hibiscus sabdariffa): Implications for in-vitro mineral bioavailability |

| Marcel et al. [109] | Enhancing the quality of overripe plantain powder by adding superfine fractions of Adansonia digitata L. pulp and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. calyces: characterization and antioxidant activity assessment |

| Bothon et al. [104] | Physicochemical variability and biodiesel potential of seed oils of two Hibiscus sabdariffa L. phenotypes |

| Bourqui et al. [94] | Hypertension treatment with Combretum micranthum or Hibiscus sabdariffa, as decoction or tablet: A randomized clinical trial |

| Elkafrawy et al. [106] | Antihypertensive efficacy and safety of a standardized herbal medicinal product of Hibiscus sabdariffa and Olea europaea extracts (NWRoselle): Aphase-II, randomized, double-blind, captopril-controlled clinical trial |

| Aboagye et al. [99] | Microbial evaluation and some proposed good manufacturing practices of locally prepared malted corn drink (“asana”) and Hibiscus sabdarifa calyxes extract (“sobolo”) beverages sold at a university cafeteria in Ghana |

| Bekoe et al. [103] | Pharmacognostic characteristics of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. as a means of monitoring quality |

| Budiman et al. [105] | Soil-climate contribution to DNDC model uncertainty in simulating biomass accumulation under urban vegetable production on a Petroplinthic Cambisol in Tamale, Ghana |

| Azeez et al. [102] | Evaluation of soil metal sorption characteristics and heavy metal extractive ability of indigenous plant species in Abeokuta, Nigeria |

| Ighodaro et al. [107] | Toxicity and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses of a polyherbal formulation commonly used in Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria |

| Kubuga et al. [115] | Container gardening to combat micronutrients deficiencies in mothers and young children during dry/lean season in northern Ghana |

| Catarino et al. [112] | Edible leafy vegetables from West Africa (Guinea-Bissau): Consumption, trade and food potential |

| Naeem et al. [118] | Evaluation of green extraction methods on the chemical and nutritional aspects of roselle seed (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) oil |

| Alegbe et al. [62] | Antidiabetic activity-guided isolation of gallic and protocatechuic acids from Hibiscus sabdariffa calyxes |

| Kane et al. [114] | Identification of roselle varieties through simple discriminating physicochemical characteristics using multivariate analysis |

| Sunmonu and Bayo Lewu [120] | Phytochemical analysis, in vitro antioxidant activity and inhibition of key diabetic enzymes by selected Nigerian medicinal plants with antidiabetic potential |

| Raghu et al. [119] | Secretory structures in the leaves of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. |

| Diallo et al. [113] | Prevalence, management and ethnobotanical investigation of hypertension in two Guinean urban districts |

| Bakary et al. [111] | Evaluation of heavy metals and pesticides contents in market-gardening products sold in some principal markets of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) |

| Misihairabgwi et al. [117] | Mycotoxin and cyanogenic glycoside assessment of the traditional leafy vegetables mutete and omboga from Namibia |

| Abdallah Mohammed Ahmed et al. [110] | A comparative study on some major constituents of Karkade (Hibiscus sabdariffa L. – Roselle Plant) |

| Kubuga et al. [116] | Hibiscus sabdariffa meal improves iron status of childbearing age women and prevents stunting in their toddlers in Northern Ghana |

| Ifie et al. [121] | Seasonal variation in Hibiscus sabdariffa (Roselle) calyx phytochemical profile, soluble solids and α-glucosidase inhibition |

| Rasheed et al. [38] | Comparative analysis of Hibiscus sabdariffa (roselle) hot and cold extracts in respect to their potential for α-glucosidase inhibition |

| Quansah et al. [122] | Microbial quality of leafy green vegetables grown or sold in Accra metropolis, Ghana |

| Seck et al. [123] | Clinical efficacy of African traditional medicines in hypertension: A randomized controlled trial with Combretum micranthum and Hibiscus sabdariffa |

| Peter et al. [126] | Efficacy of standardized extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) in improving iron status of adults in malaria endemic area: A randomized controlled trial |

| Suliman et al. [130] | Effect of Hibiscus seed-based diet on chemical composition, carcass characteristics and meat quality traits of cattle |

| Bayendi Loudit et al. [124] | Peri-urban market gardening in Libreville and Owendo (Gabon): Farmers’ practices and sustainability |

| Sanon et al. [127] | Report on Spermophagus Niger Motschulsky, 1866 (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae: Amblycerini) infesting the seeds of roselle, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae) during post-harvest storage in Burkina Faso |

| Nwachukwu et al. [125] | Does consumption of an aqueous extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa affect renal function in subjects with mild to moderate hypertension? |

| Amadou et al. [128] | Triple bag hermetic technology for controlling a bruchid (Spermophagus sp.) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) in stored Hibiscus sabdariffa grain |

| Ndiaye et al. [129] | Application of PCR-DGGE to the study of dynamics and biodiversity of microbial contaminants during the processing of Hibiscus sabdariffa drinks and concentrates |

| Farag et al. [135] | Volatiles and primary metabolites profiling in two Hibiscus sabdariffa (roselle) cultivars via headspace SPME-GC-MS and chemometrics |

| Osman et al. [138] | Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with chronic kidney disease and kidney transplant recipients |

| Nwachukwu et al. [137] | Effect of Hibiscus sabdariffa on blood pressure and electrolyte profile of mild to moderate hypertensive Nigerians: A comparative study with hydrochlorothiazide |

| Aworh [131] | Promoting food security and enhancing Nigeria’s small farmers’ income through value-added processing of lesser-known and under-utilized indigenous fruits and vegetables |

| Baoua et al. [132] | Grain storage and insect pests of stored grain in rural Niger |

| Salem et al. [140] | Physicochemical and microbiological characterization of cement kiln dust for potential reuse in wastewater treatment |

| Icard-Vernière et al. [136] | Contribution of leafy vegetable sauces to dietary iron, zinc, vitamin a and energy requirements in children and their mothers in Burkina Faso |

| Oulai et al. [139] | Evaluation of nutritive and antioxidant properties of blanched leafy vegetables consumed in Northern Cote d’Ivoire |

| Eghosa et al. [134] | Effects of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. consumption during pregnancy on biochemical parameters and litter birth weight in rats |

| Dawoud and Sauerborn [133] | Efficiency of some crops in inducing suicidal germination of the parasitic weed, Striga hernonthica Del Benth |

| Mugisha et al. [143] | Ethnobotanical study of indigenous knowledge on medicinal and nutritious plants used to manage opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS in western Uganda |

| Bakasso et al. [141] | Genetic diversity and population structure in a collection of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) from Niger |

| Peter et al. [146] | Ethno-medicinal knowledge and plants traditionally used to treat anemia in Tanzania: A cross sectional survey |

| Mwasiagi et al. [144] | Characterization of the Kenyan Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Roselle) Bast Fibre |

| Hassan et al. [142] | Occurrence of root rot and vascular wilt diseases in roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Upper Egypt |

| Ogunkunle et al. [145] | A quantitative documentation of the composition of two powdered herbal formulations (antimalarial and haematinic) using ethnomedicinal information from Ogbomoso, Nigeria |

| Al-Shafei and El-Gendy [149] | Effects of roselle on arterial pulse pressure and left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients |

| Asiimwe et al. [150] | Ethnobotanical study of nutri-medicinal plants used for the management of HIV/AIDS opportunistic ailments among the local communities of western Uganda |

| Ondo et al. [153] | Accumulation of soil-borne aluminium, iron, manganese and zinc in plants cultivated in the region of Moanda (Gabon) and nutritional characteristics of the edible parts harvested |

| Agbobatinkpo et al. [147] | Biodiversity of aerobic endospore-forming bacterial species occurring in Yanyanku and Ikpiru, fermented seeds of Hibiscus sabdariffa used to produce food condiments in Benin |

| Fadl [151] | Influence of Acacia senegal agroforestry system on growth and yield of sorghum, sesame, roselle and gum in north Kordofan State, Sudan |

| Ondo et al. [152] | Impact of urban gardening in an equatorial zone on the soil and metal transfer to vegetables |

| Aletor et al. [148] | Antinutrient content, vitamin constituents and antioxidant properties in some value-added Nigerian traditional snacks |

| Savadogo et al. [158] | Identification of surfactin producing strains in Soumbala and Bikalga fermented condiments using polymerase chain reaction and matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry methods |

| Azokpota et al. [156] | Evaluation of Yanyanku processing, an additive used as starter culture to produce fermented food condiments in Benin |

| Brévault et al. [157] | Insecticide use and competition shape the genetic diversity of the aphid Aphis gossypii in a cotton-growing landscape |

| AbouZid and Mohamed [154] | Survey on medicinal plants and spices used in Beni-Sueif, Upper Egypt |

| Yongabi et al. [159] | Application of phytodisinfectants in water purification in rural Cameroon |

| Atta et al. [155] | Yield character variability in Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) |

| Oyewole and Mera [164] | Response of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) to rates of inorganic and farmyard fertilizers in the Sudan savanna ecological zone of Nigeria |

| Morrison and Twumasi [163] | Comparative studies on the in vitro antioxidant properties of methanolic and hydro-ethanolic leafy extracts from eight edible leafy vegetables of Ghana |

| Abdelghany et al. [160] | Stored-product insects in botanical warehouses |

| Uvere et al. [165] | Production of maize-bambara groundnut complementary foods fortified pre-fermentation with processed foods rich in calcium, iron, zinc and provitamin A |

| Fadl and El Sheikh [162] | Effect of Acacia senegal on growth and yield of groundnut, sesame and roselle in an agroforestry system in North Kordofan state, Sudan |

| Fadl [161] | Growth and yield of groundnut, sesame and roselle in an Acacia senegal agroforestry system in North Kordofan, Sudan |

| Sarr et al. [58] | In vitro vasorelaxation mechanisms of bioactive compounds extracted from Hibiscus sabdariffa on rat thoracic aorta |

| Nwafor and Ikenebomeh [170] | Effects of different packaging materials on microbiological, physio-chemical and organoleptic quality of zobo drink storage at room temperature |

| El Tahir et al. [168] | Changes in soil properties following conversion of Acacia senegal plantation to other land management systems in North Kordofan State, Sudan |

| Cisse et al. [167] | Bissap (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) production in Senegal |

| Juliani et al. [169] | Chemistry and quality of hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa) for developing the natural-product industry in Senegal |

| Agbo et al. [166] | Nutritional importance of indigenous leafy vegetables in Cote d'Ivoire |

| Brévault et al. [171] | Genetic diversity of the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii in the unstable environment of a cotton growing area |

| Parkouda et al. [174] | Technology and physico-chemical characteristics of Bikalga, alkaline fermented seeds of Hibiscus sabdariffa |

| Ojokoh et al. [173] | Chemical composition of fermented roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) calyx as affected by microbial isolates from different sources |

| Mohamadou et al. [172] | Bacterial fermentation induced mineral dynamics during the production of Mbuja from Hibiscus sabdariffa seeds in earthen-ware pots |

| Ouoba et al. [181] | Identification of Bacillus spp. from Bikalga, fermented seeds of Hibiscus sabdariffa: phenotypic and genotypic characterization |

| Obadina and Oyewole [179] | Assessment of the antimicrobial potential of roselle juice (zobo) from different varieties of roselle calyx |

| Sowemimo et al. [182] | Toxicity and mutagenic activity of some selected Nigerian plants |

| Olaleye [180] | Cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa |

| Diouf et al. [178] | The commodity systems of four indigenous leafy vegetables in Senegal |

| Avallone et al. [176] | Home-processing of the dishes constituting the main sources of micronutrients in the diet of preschool children in rural Burkina Faso |