Abstract

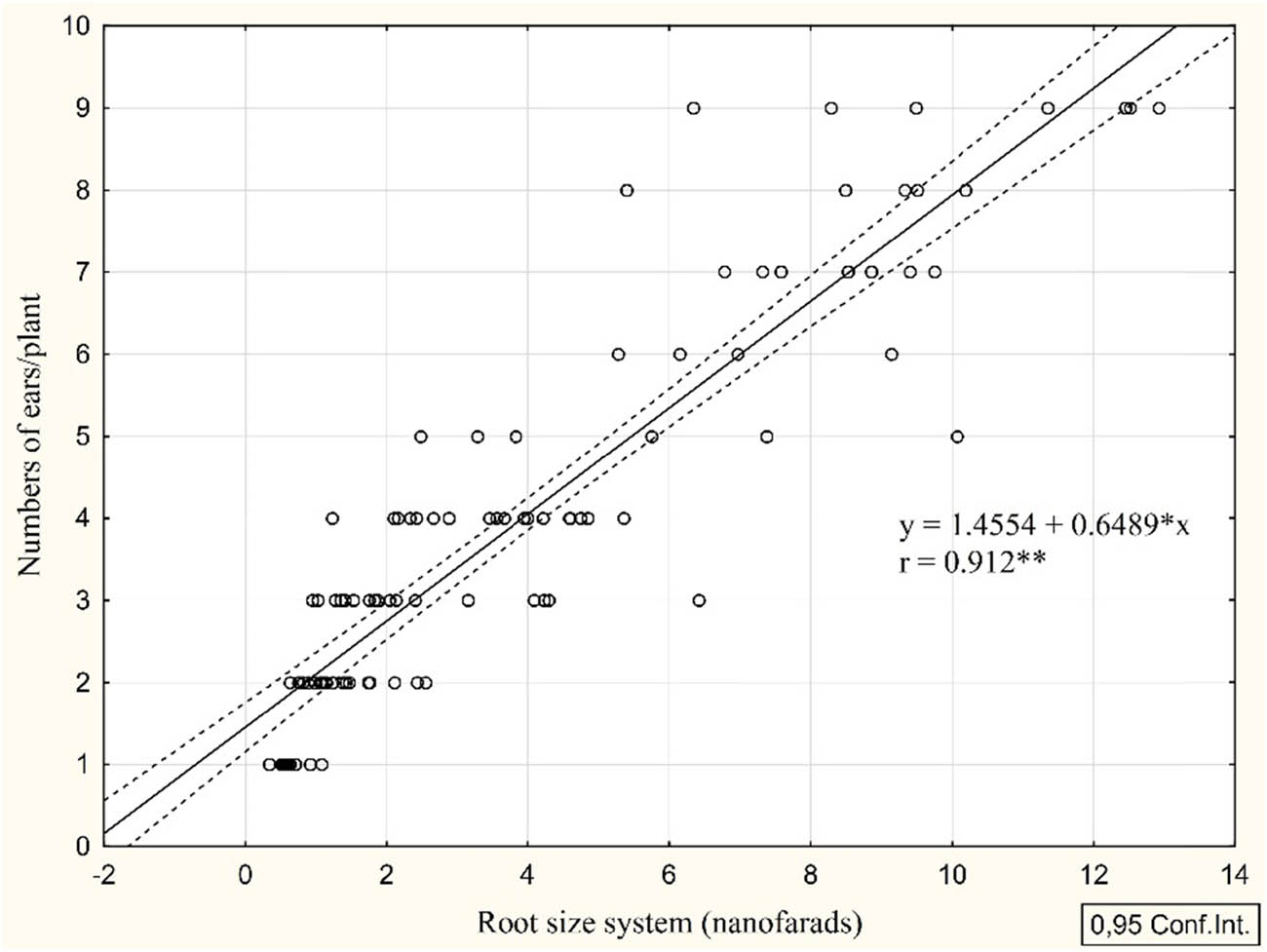

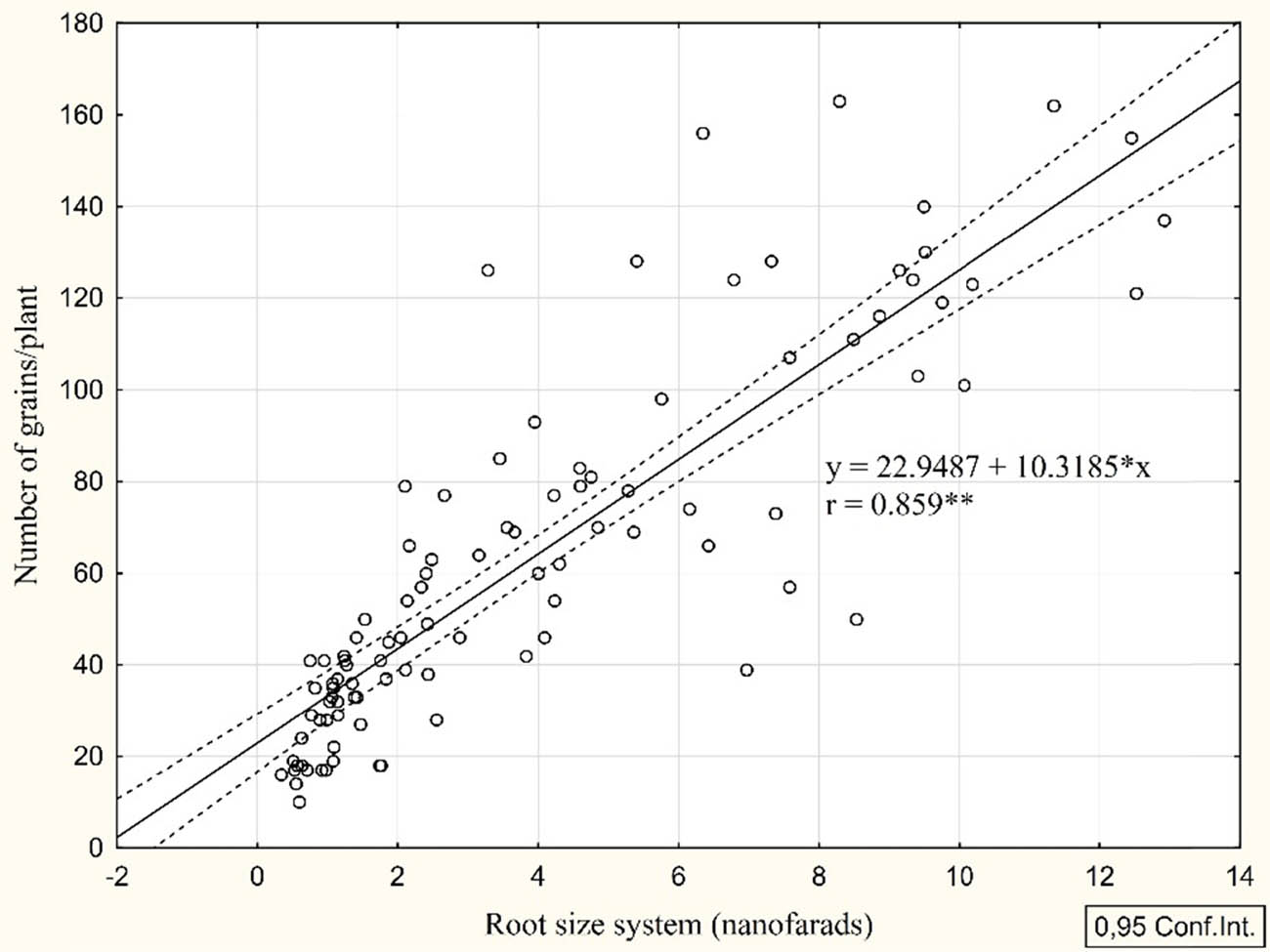

In this study, the effect of nitrogen doses (52, 80, 110, 140 kg/ha N) and the application of biostimulant preparations containing Ascophyllum nodosum L. algae extract were assessed. During the years 2018–2019, the influence of the preparations on the electrical capacity of the roots (C R) and yield components of spring barley was determined. Root electrical capacitance was determined in growth stages 45–50, 55–65, and 70–75 according to the BBCH-scale. The best phases of vegetation growth for the application of biostimulators with Ascophyllum nodosum extract were the barley tillering and elongation phases. This application increased C R while reducing the amount of N required to achieve similar or higher production of barley yield components compared to high N treatments. The root electrical capacitance, the number of productive tillers, and the number of grains per plant were significantly influenced (p > 0.05) by the weather of the year. The number of productive tillers was closely correlated with C R (r = 0.912**) as well as the number of grains per plant (r = 0.859**) and their weight (r = 0.850**). These relationships were the highest at the beginning of the grain formation (BBCH 70–75). Foliar biostimulation was not very effective in the dry year of 2018. The problem may be the foliar application itself. The effect of foliar application is strongly dependent on weather conditions and may be ineffective in many cases. We recommend the foliar application of effective biostimulants in tillering and elongation phases. They can reduce production costs and environmental pollution by reducing the amount of fertilizer needed while maintaining yields.

1 Introduction

Ascophyllum nodosum is one of the most researched and used algae in agricultural production [1]. Much of the research on the effects of A. nodosum extracts on various plant species has been reviewed [1]. The positive effects of A. nodosum on plants include better absorption of macro and micronutrients, improved root and above-ground growth, stimulation of gene expressions involved in plant growth and development, and increased tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses [1,2,3,4,5]. The positive effects are related to phytohormones such as auxins, cytokinins, abscisic acid, and substances with similar effects [1,2,3,4,5]. The content of the individual components is highly variable and differs depending on the extraction methods (acid or basic hydrolysis and others), pH, temperature, and time of the algae harvest [4].

Malting barley (Hordeum vulgare) is the primary raw material for beer production and has to achieve high yields with optimal grain quality. The shape, size, weight, test weight, germination of the grain, and the content of nitrogenous substances in the grain are very important [6,7]. The malting industry demands a high quality of malting barley, which also determines its purchase price and use [6,7]. Quality standards are often not met, and malting barley is bought at a low price or used for animals [6,7]. Drought and high temperatures most often cause reduced yield and grain quality [8]. A number of agronomists then use fertilizers with a high nitrogen content to correct quality or yields. It is a negative side of agronomy which has a negative impact on ecology. In addition, a large amount of used fertilizers is not used by plants. Depending on the weather, 65% of the applied nitrogen fertilizer may not be absorbed by crops and end up in the environment [9,10,11]. A. nodosum can generally stimulate root growth or increase the efficiency of soil nutrient absorption and utilization [1]. An increase in the efficiency of nutrient uptake was also observed in cereals (H. vulgare, Triticum aestivum/durum, Zea mays). It was related to a higher yield of plants and a reduction in the required amount of fertilizers [1,2,3,4,5]. Drought and increased temperature have a negative effect on the root system size (RSS), and they change its architecture [10,11]. Elevated temperature increases the negative impact of drought but can also act on its own. Therefore, even with sufficient precipitation, there may be a decrease in the yield or quality of cereals [10–15]. RSS and architecture play a key role in the absorption of water and nutrients from the soil [12–14]. The growth of primary or lateral roots and the formation of root hairs are related to the availability of water and nutrients [12,13,14]. A quick response to a negative condition through root growth gives plants an advantage. With this strategy, the plants can find faster groundwater or missing nutrients. Such cereals are more resistant to drought [15,16]. Stimulation or inhibition of root growth, as well as growth direction, is also influenced by the interactions of phytohormones, weather, and variety [13,14,17,18]. The higher the plasticity of the plant root system, the higher the tolerance level against drought stress [12–14]. The root architecture of barley root, its volume or size, and growth direction affect the yield and barley grain quality and can affect the response of plants in various stressful situations. This impact is strongly dependent on the weather, especially on the temperature and the amount of precipitation [12]. In malting barley, a bigger root system increases starch content, malt extract, and proteins during the dry season [11]. On the contrary, in dry conditions a weak root system corresponds to a low grain yield and a significant deterioration in quality [11]. A positive correlation was found between the grain yield of barley and the amount of root hairs in dry conditions [19]. However, a large root system can also be a disadvantage and can reduce grain quality in conditions of excessive precipitation. In these conditions, a shallow but wide root system is more suitable [17]. A narrow and deep root system may be more advantageous in dry conditions as it provides access to water from the deeper soil layers during the grain-filling phase [18]. If there are drought conditions from the beginning of the vegetative stage with the following period of sufficient moisture, the cereals are able to compensate for these negative effects on grain quality and yield [15]. However, in the state of water shortage during flowering and grain filling, the grain yield and its quality are compromised because the plants are no longer capable of any compensation in this phase [20].

A non-destructive method based on measuring C R is being used to determine the size of the root system [21]. The electrical capacitance has been used as a non-destructive measure of RSS for 30 years [22]. This measurement does not destroy the roots ,especially, the root hairs. Root hairs less than 0.25 mm in size can represent 95% of the root length [23]. Determination of the RSS takes place indirectly by measuring its C R, which is closely correlated with the length and surface of the roots [21,22,24]. This method makes it possible to measure many plants per day and to repeat the measurements on the same plants in different phenological phases [21]. The advantage is practicality and easy application in field conditions. Under standardized soil conditions and with the constant location of the electrode on the plant above the substrate surface, the method adequately estimates the RSS [23–26]. This method has been used in the breeding of plants against drought, especially cereals [11,21]. Correlations were also found between C R and the content of starch, protein, malt extract or barley grain yield, overall malt quality, or prediction of grain yield depending on the air conditions [11,21,26]. A disadvantage of this method is that it cannot display root morphology such as branching, distribution pattern, or penetration depth [27].

This research was focused on the evaluation of the combination effect of biostimulators derived from A. nodosum and the required amount of nitrogen nutrition to achieve a favorable effect on C R and the formation of yield components such as the number of ears, tillers, or grains of malting barley.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental fields

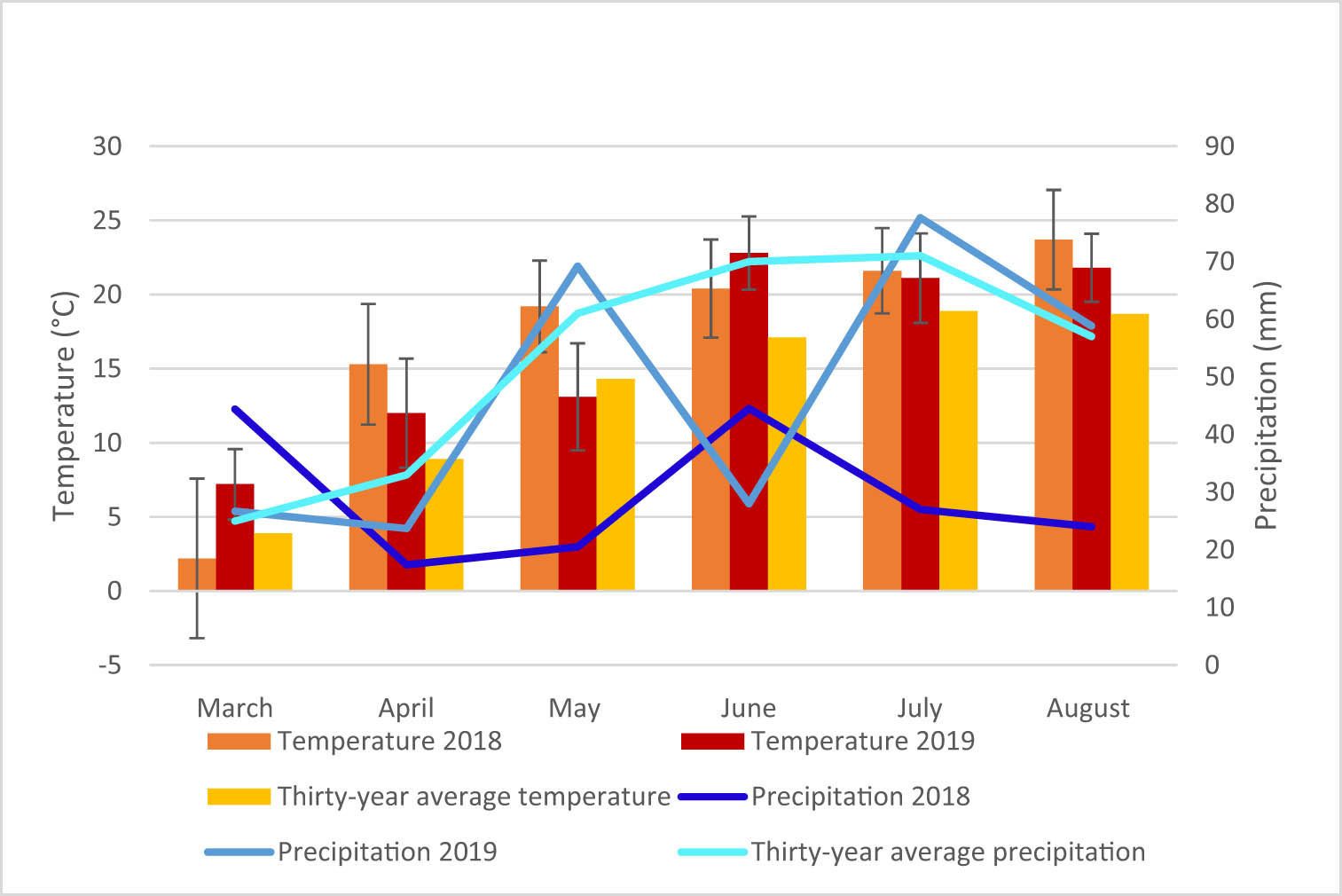

A small-plot field experiment was performed on fields belonging to the agricultural company Agrospol Velká Bystřice near Olomouc, Czech Republic, from March to August 2018 and 2019. Each treatment was grown on three small plots, which means three repetitions, each 13 m2. The experimental plots are located at the coordinates of 49°61′ north latitude and 17°35′ east longitude. The average altitude is 240 m. The land is located in a slightly warm and humid climate. The soil is a cambisol type. Weather conditions during the growing periods are given in Figure 1. The previous crop was sugar beet. The incorporation of post-harvest residues (beet tops) was carried out by medium ploughing. The experimental fields were in the same region, in the same soil and coordinates, and in the same pre-crop each year. Fields were facing each other across a field road.

Weather conditions during the 2018–2019 growing season.

2.2 Experimental treatments, sowing, and mineral content in the soil

At the end of February, prior to planting, the amount of basic minerals in the soil was determined. Subsequently, P, K, and N fertilizers were applied in solid granular form. Amophos containing 52% P2O5 and 12% NH4 and potassium salt containing 60% K2O were used for fertilization. The applied dose of P and K was 22.7 kg/ha P and 40 kg/ha. Ammonium nitrate with calcium carbonate (27% N, 20% CaCO3) was applied at a rate of 52 kg/ha N. The final agrochemical characteristics of soil after 4 weeks from application are presented in Table 1. The Francin barley variety was sown. The sowing rate was 3.7 million germinating seeds per hectare. The sowing was carried out on 4 April 2018 and on 26 March 2019. Further fertilization to the selected level of N-nutrition was applied after the emergence of the plants, and ammonium nitrate with calcium carbonate was applied again. The experiments were harvested on 30 July 2018 and on 6 August 2019.

Agrochemical properties of the plot during sowing (units mg/kg of soil)

| Year | pH | K | P | Mg | S | Ca | N (Nan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 5.72 | 212 | 58.1 | 150 | 10.7 | 2,280 | 178 |

| 2019 | 5.88 | 187 | 72.3 | 114 | 12.6 | 1,470 | 212 |

The nutrient content is determined according to Mehlich III, Experimental treatments.

The ten experimental treatments are summarized in Table 2. The doses of nitrogen were 52, 80, 110, and 140 kg/ha N, and it was applied in BBCH 15 (leaf development). The biostimulant preparations called Rooter and Forthial containing the extract of the algae A. nodosum L. were applied with and without nitrogen in BBCH 27 (end of tillering) and BBCH 31–34 (stem elongation). The first four treatments are with the lowest nitrogen dose and one or the other biostimulator or both. The next three are just with increasing N dose, and the last three are with increasing N and both biostimulants. The application concentration of the biostimulants was 1% A. nodosum extract, and the rate was 1 l/ha (Table 2). The foliar application was applied in the morning. The composition of herbal preparations is listed in Table 3.

Experiment scheme

| Treatment | Dose of N (kg/ha) | Rooter | Forthial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before sowing | BBCH 15 | BBCH 27 | BBCH 31–34 | |

| 1 | 52 | |||

| 2 | 52 | 1 l/ha | ||

| 3 | 52 | 1 l/ha | ||

| 4 | 52 | 1 l/ha | 1 l/ha | |

| 5 | 52 | 28 | ||

| 6 | 52 | 58 | ||

| 7 | 52 | 88 | ||

| 8 | 52 | 28 | 1 l/ha | 1 l/ha |

| 9 | 52 | 58 | 1 l/ha | 1 l/ha |

| 10 | 52 | 88 | 1 l/ha | 1 l/ha |

Note: each treatment was repeated three times.

Composition of biostimulators

| Rooter | Forthial | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total phosphorus (P2O5) | 13.0% | Total nitrogen (N) | 6.02% |

| Total potassium (K2O) | 5.0% | Water-soluble Mg (MgO) | 9.0% |

| Extract of A. nodosum | 25% | Extract of A. nodosum | 30.5% |

| pH | 1.60–2.6 | pH | 6.7–7.7 |

2.3 RSS

The measurements were performed according to the methodology of Středa et al. [21]. The root electrical capacitance was measured using an LCR 4080 digital multimeter (Voltcraft, Germany) commonly used to measure the condenser electrical capacitance (parallel mode, 1 kHz, 1 V AC). A sharp stainless-steel rod (5 mm diameter, 20 cm long) was inserted 100 mm into the field soil and 100 mm from the base of the stem. The plant stainless-steel clamp (14 cm long) was clamped to all the basal parts (all tillers of one plant) of the plant 15 mm above ground level. The clamps are more practicable and less destructive than needles through the stem [24]. Each reading was taken after allowing the meter to stabilize for 6 s to obtain a case. The electrical capacitance of the roots is given in nanofarad units. The measurement took place in a standard established stand with an inter-row distance of 12.5 cm. The measured plants were always unified (plucking) in the second row of the experimental plot for each repetition so that the plants did not touch each other, and the results were not affected. There were three repetitions of each treatment with five plants. The measurements were performed at the end of shooting (BBCH 45–50), during the stages from heading to flowering (BBCH 55–65) and at the beginning of grain formation (BBCH 70–75). The number of productive tillers was determined for each plant at the full maturity. The measured plants were harvested, and the number of grains per plant and their weight were evaluated.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The results were evaluated using Microsoft Excel and Statistica 12 using multifactor analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of 95% (p > 0.05). The relationships between the selected parameters were evaluated by the correlation analysis using Pearson correlation coefficients at the 95% significance level (p > 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Weather conditions

Both years were warmer than the 30-year-old (Figure 1). In 2018, there was a lack of precipitation throughout the growing season, and it was extremely dry. At first, 2019 was a little dry, but then the rainfall increased to be above the 30-year average. This caused a long dry and warm period followed by high rainfall.

The strongly negative weather conditions were significantly reflected in the growth and development of the malting barley during the vegetative stage in 2018. The sowing date was delayed due to the relatively high precipitation level in March. Subsequent severe drought negatively affected the growth and development of barley. This was also reflected in the average values of C R.

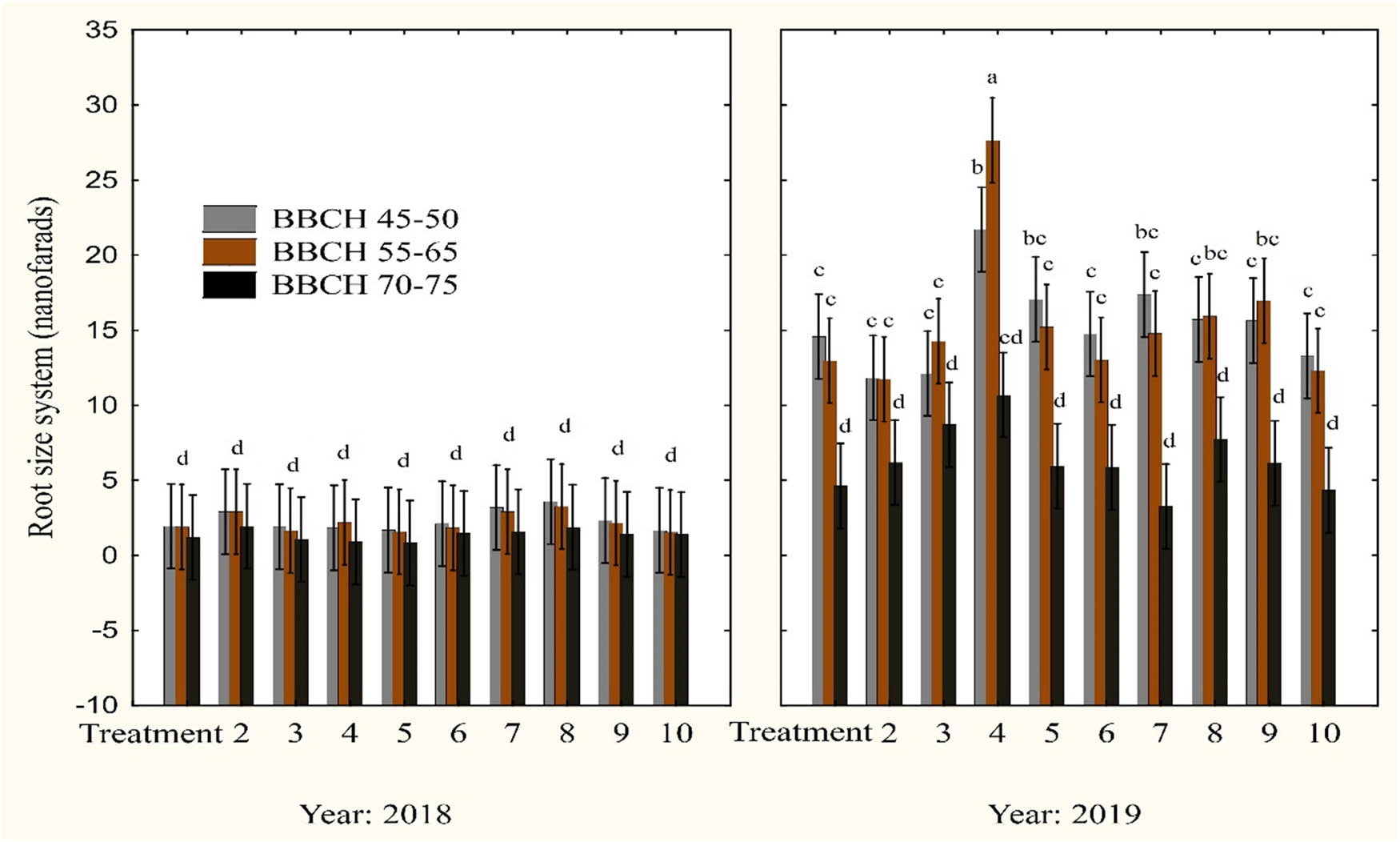

The extreme drought in 2018 had a significant effect on the RSS. The unfavorable precipitation conditions and drought from the beginning of the vegetative stage eliminated the effect of nitrogen fertilization and biostimulators in 2018. The vegetative stage was also shortened (late sowing, early harvest), indicating the long-term stress to which the plants were exposed. Thus, the extent of the negative effect was directly dependent on the duration of the stress. By comparison, in 2019, there was a significant (p > 0.05) reduction in C R with minimal changing dynamics during the vegetative stage (Figure 2). The precipitation level was lower at the beginning of the vegetative stage in 2019. Colder May than the 30-year-old and excess precipitation in June and July had a positive effect on plant growth and development. In 2019, more favorable weather conditions corresponded to better dynamics of the RSS. Every aspect of the weather influenced the application of fertilizers or biostimulants and their effects.

Effect of the year and the date of the measurement on the RSS. Vertical error bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals with least squares.

3.2 Effect of biostimulators, amount of nitrogen on RSS

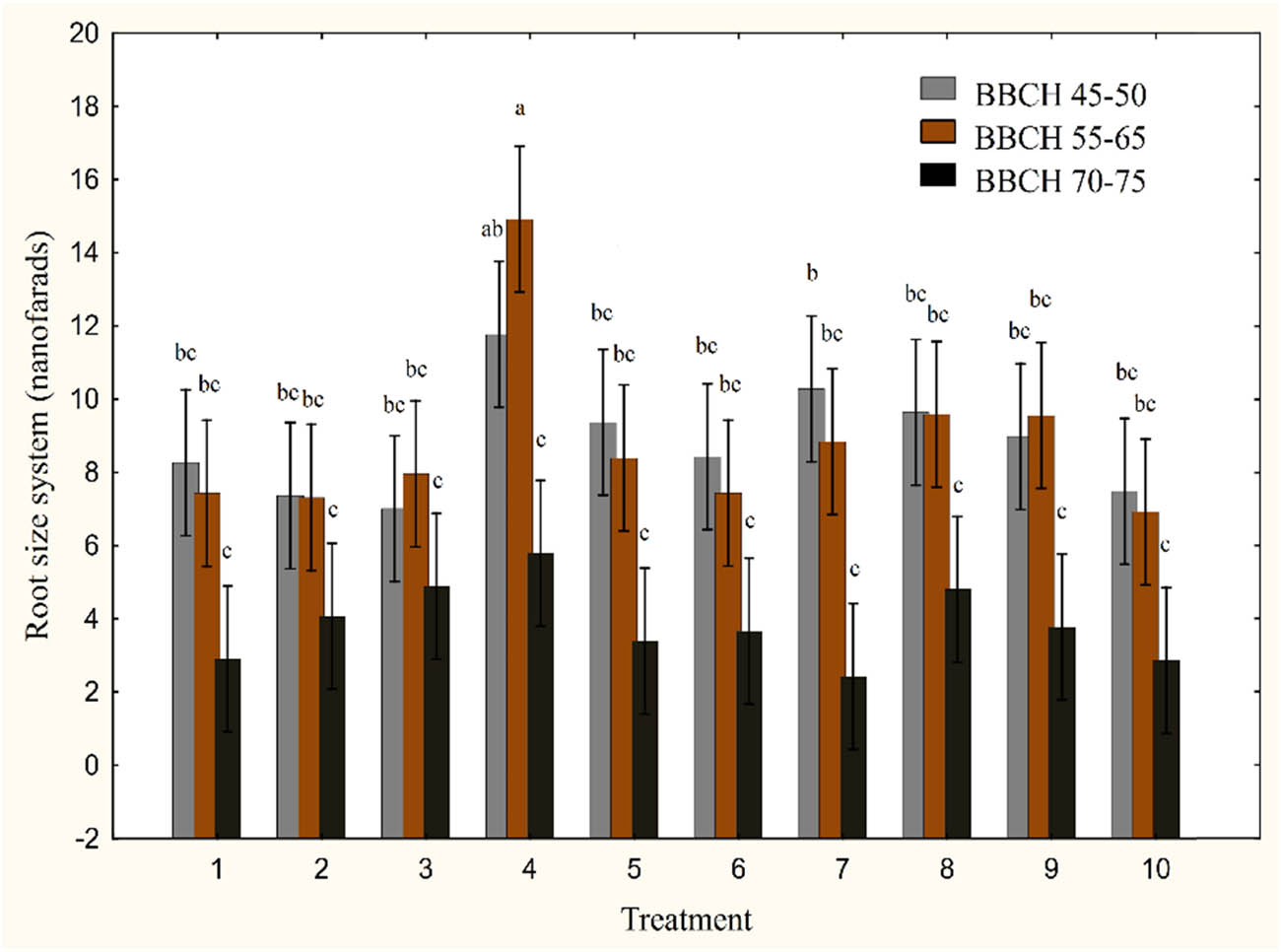

The highest C R was recorded at the BBCH 45–50 in most treatments (Figure 2). At the BBCH 55–65, the highest value of C R was recorded in treatment with the lowest N and combination of biostimulants (treatment 4). A higher intensity of nitrogen fertilization did not significantly lead to an increase in C R (Figure 3).

Effect of the treatment and the measurement date on the RSS. Averages of 2 years of data, vertical error bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals with least squares.

The combination of the highest N dose and biostimulants (treatment 10) caused the smallest RSS and was similar to the control (treatment 1). The BBCH 55–65 showed the highest RSS (p > 0.05) in treatment with the lowest N dose and combination of biostimulants, which represents the lowest dose of nitrogen when applying both biostimulators with A. nodosum extract. This treatment at BBCH 65–70 (end of flowering) still showed higher root activity. The root activity was gradually decreased at the beginning or during ripening.

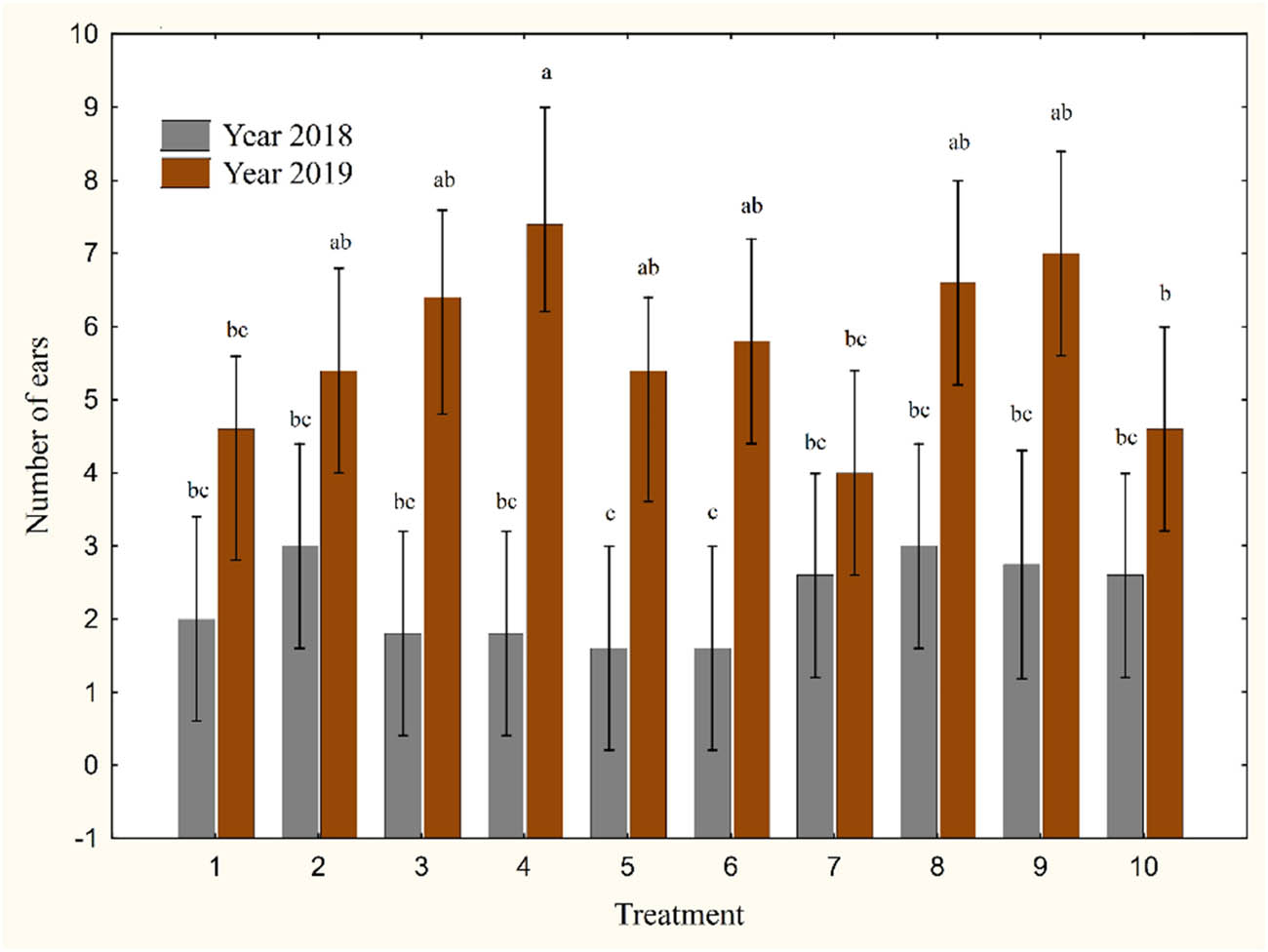

3.3 Effect of biostimulators, amount of nitrogen on yield components

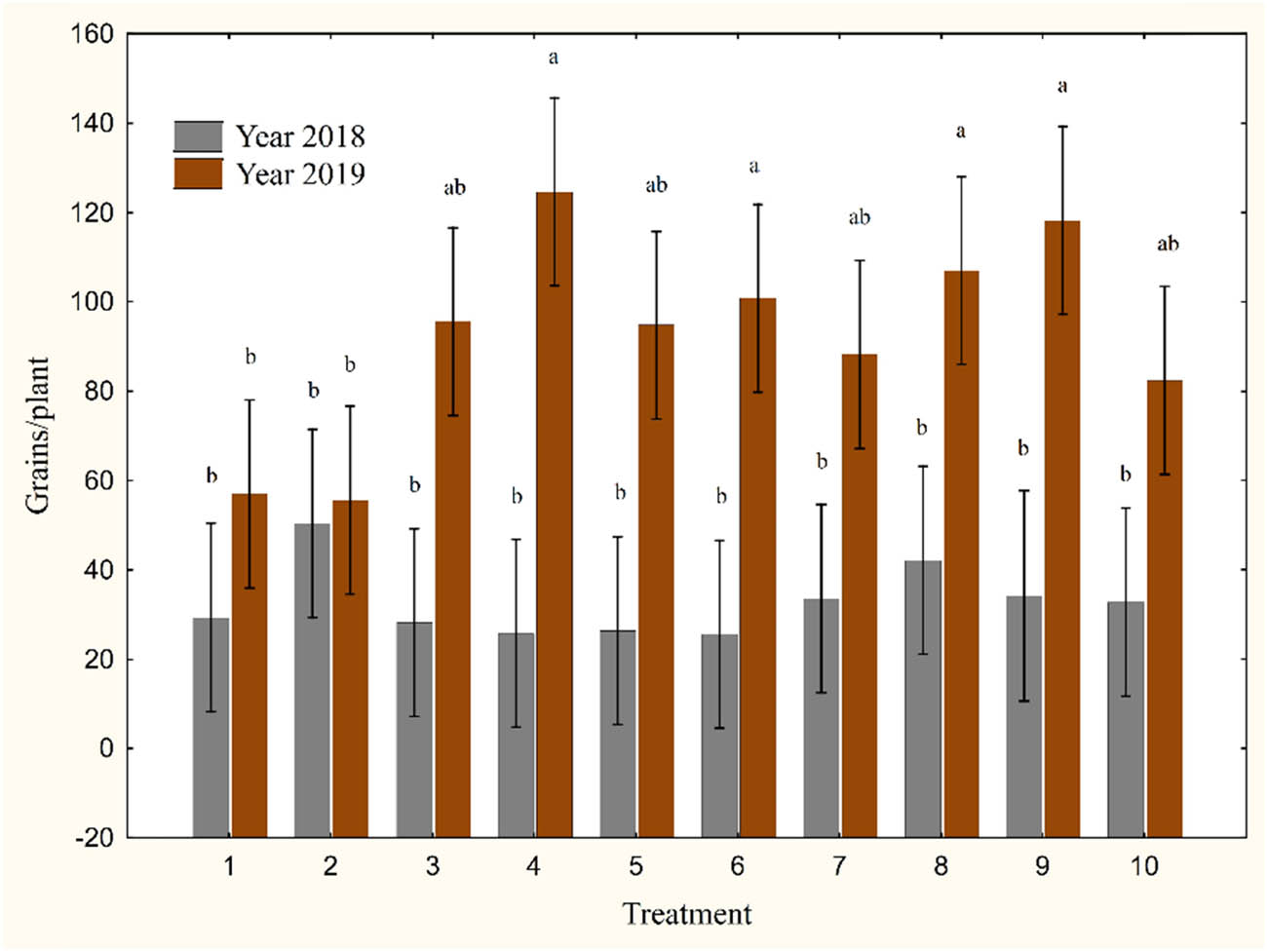

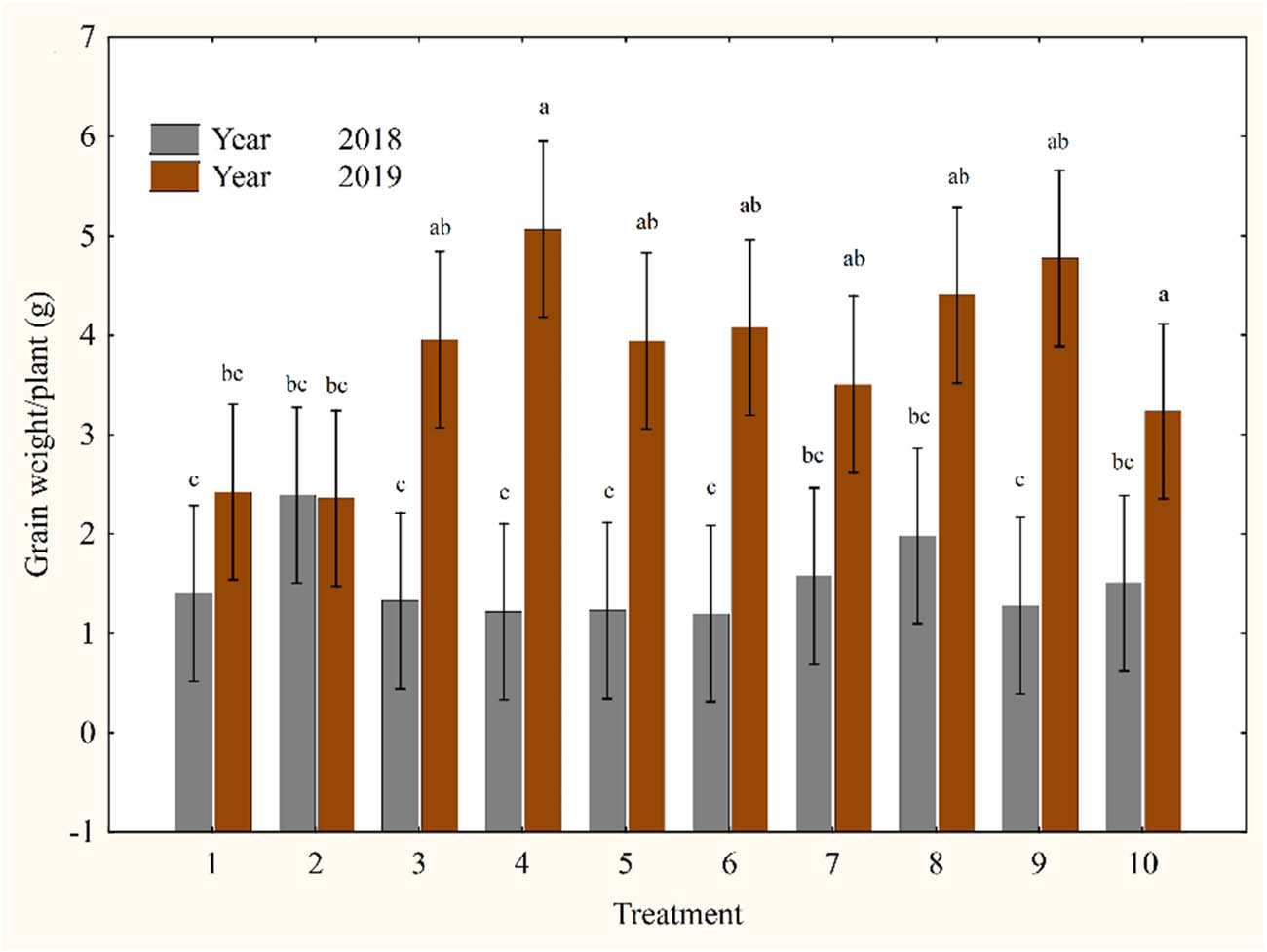

Drought and higher temperatures in 2018 reduced the formation of productive tillers, the number of grains per plant, and the weight of grains (Figures 4–6). This effect was significant in most treatments (p > 0.05). An increase in the number of productive tillers, grains per plant, and grain weight was detected in 2019, especially for treatments with a low N dose and a combination of biostimulants and two higher N doses with both biostimulants. Significantly, the highest effect (p > 0.05) was recorded at the lowest nitrogen dose with the application of both biostimulators (treatment 4). A higher intensity of the nitrogen fertilization and application of both biostimulators no longer led to a significant increase in the number of productive tillers, grains per plant, or grain weight.

Effect of the year and the treatment on the number of ears per plant. Vertical error bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals with least squares.

Effect of the year and the treatment on the number of grains per one plant. Vertical error bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals with least squares.

Effect of the year and the treatment on grain weight per one plant. Vertical error bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals with least squares.

3.4 Correlations of yield components and RSS

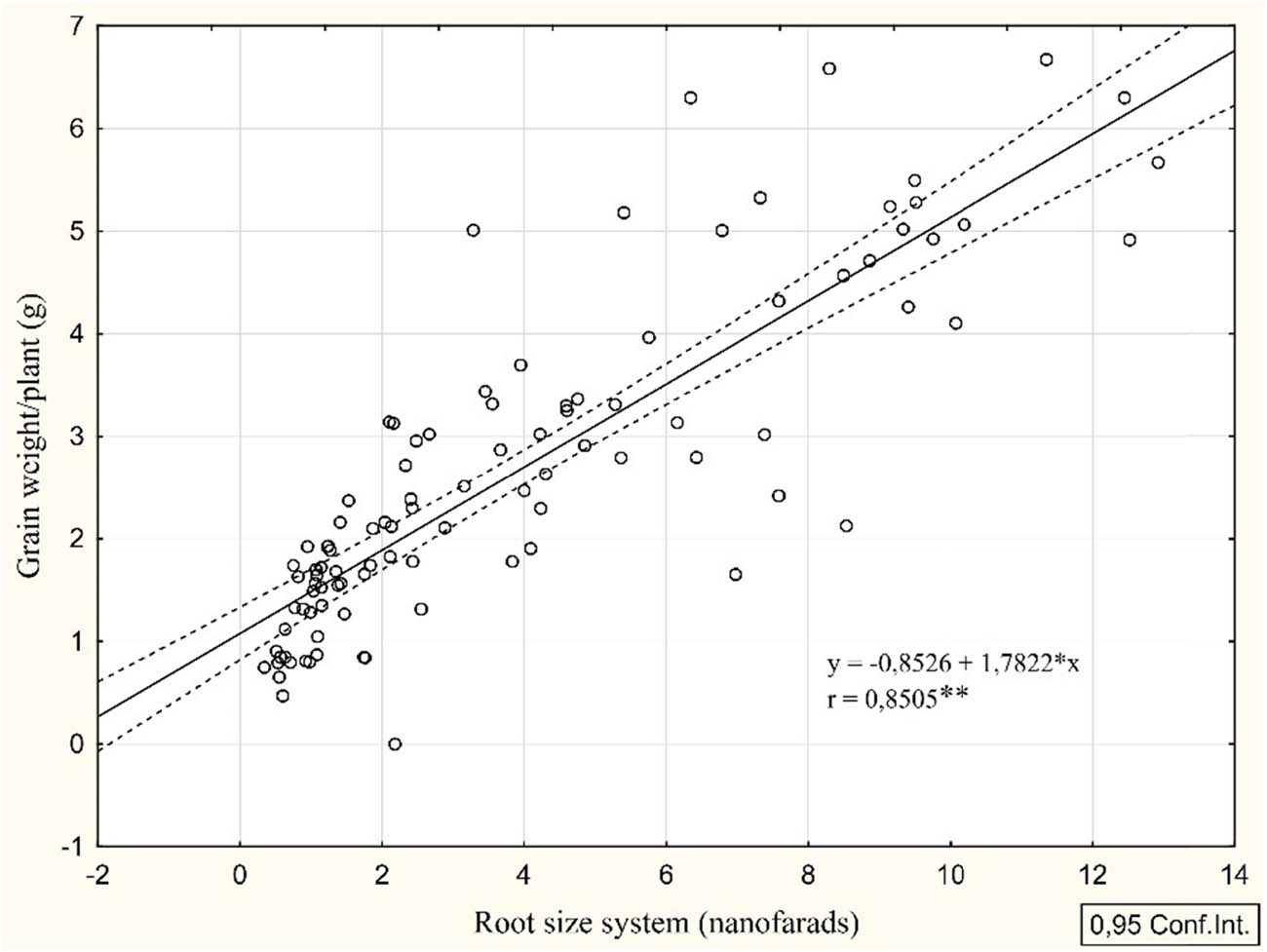

The C R correlated very closely with the number of productive tillers as well as the number of grains and the grain weight per plant (Figures 7–9). The correlations were very strong from the first measurement at BBCH 45–50 and slowly increased. At BBCH 45–50 and BBCH 55–65 (graphs not presented) correlation of productive tillers with C R was 0.777 and 0.818. The correlation of grain number with C R was 0.828 and 0.8614 at BBCH 45–50 and BBCH 55–65. The correlation of grain weight with C R was 0.808 and 0.844 at BBCH 45–50 and BBCH 55–65. The strongest correlations were at BBCH 70–75 (r = 0.912**), (r = 0.859**) for tillers and grain number. The correlation of grain weight was (r = 0.850**).

Relationship between RSS and number of ears. BBCH 70–75, averages of 2 years of data.

Relationship between RSS and several grains on a plant. BBCH 70–75, averages of 2 years of data.

Relationship between RSS and grain weight of 1 plant. BBCH 70–75, averages of 2 years of data.

4 Discussion

Drought is one of the most serious negative factors, which affects root growth and RSS. In the short term, plants stimulate root growth to depth, a strategy to find groundwater [12–14]. On the other side, the long-term drought has an extremely negative effect on the growth, structure, and development of roots and whole plants [8,10]. The extent of the negative effect on barley growth was directly dependent on the duration of the stress. This fact has been confirmed by many other authors [15]. Low root growth could also be attributed to high temperatures, which can affect root activity and morphology even with sufficient soil moisture [10]. High temperatures and heat thus fundamentally increase the negative effect of drought [9–12]. In 2018, both factors occurred, so the system of root size reached low values. Impacts of biostimulants and nitrogen were also on low values. In general, biostimulants should help plants with abiotic stress [28,29]. In these extreme conditions, a problem could be in time of application. Many studies indicate that humidity is important for the good absorption of various substances by leaves [30,31]. In some cases, foliar nutrition is applied in the morning and other times in the evening, but there is often no record of the time of application or weather conditions [30,31]. Low humidity, drought, light, and heat can affect foliar intake [30]. In case of a long period of drought and heat, the morning humidity rapidly decreases, and the evaporation of drops from leaves accelerates. The condition of the plants is also important. Crops under heat or water stress show less response to foliar applications. Those are the conditions of 2018. It follows that in extremely unfavorable conditions, it will be necessary to change the application time. At least 70% moisture, ideal 21°C and no wind is recommended [31]. Those conditions favor tissue permeability. Therefore, the very early morning or even late evening application may be better for the plants depending on the conditions [30,31]. Solid nitrogen fertilizer is not a suitable form for fertilizing in the dry season. Its solubility is at a low level and cannot be absorbed by the roots without water. These are important findings for agronomy.

The presence or absence of nitrogen in the soil also affects the architecture and direction of plant root growth [32]. Initially, the root of some treatments showed a higher C R but later significantly reduced. The reason could be that the plants rather established lateral roots located shallowly below the surface with regard to the application of N-fertilizers in the surface area [33,34]. These roots can be more sensitive to drought or heat and die faster. The combination of the highest N dose and biostimulators caused the smallest RSS. Improving nutrient absorption with A. nodosum can also have a negative effect at high doses of nitrogen [3]. Separate increasing N-nutrition did not have a visible negative effect in this experiment. Drought in 2018 also showed a significant impact on the reduced formation of productive tillers, the number of grains per plant, and the weight of grains. Similar conclusions were reached by Ihsan et al. [35].

The RSS was larger in the favorable or optimal conditions of 2019. The application of both biostimulants at BBCH 27 and BBCH 30–34 and the lowest dose of N caused a larger root system, and we obtained a better result of the yield components than with a higher dose of N. A reduced amount of N to achieve better yield results was confirmed by studies aimed at increasing the efficiency of nitrogen utilization and absorption by means of A. nodosum [1,2,5,9]. The use of A. nodosum extracts can reduce cultivation costs and environmental pollution while maintaining favorable yields [5,9]. Measuring the size of the root system showed the demonstrable dependence between the RSS and the number of tillers, grains per plant, and grain weight. The results show the best time for foliar biostimulation is BBCH 27 and BBCH 30–34 (end of tillering-stem elongation). A similar result was reached by another study [28]. In 2019, the root activity decreased at the beginning of ripening. This is a normal state; cereals begin to form grain, and root activity ceases. The application of both biostimulators caused an increase in the RSS even during BBCH 65–70, thus still retaining the potential activity of the root. Cseresnyés et al. [36], showing that saturation of C R at anthesis can be used to adequately predict grain yield (R2: 0.585–0.686). In another study [26], they showed strong correlations between C R during flowering and grain mass, grain number, leaf area index, and total chlorophyll in the flag. The C R correlation is also related to starch content, protein, malt extract, or its quality [11,21]. In our experiment, correlations of yield components with C R were also very strong. At BBCH 70–75, the correlations were r = 0.912 for the number of productive tillers, r = 0.859 for the number of grains per plant, and their weight r = 0.850. Prolongation of root activity during grain maturation can improve grain quality and yield under optimal conditions. If the conditions are favorable in the grain formation and the root is still active, the grain filling time can be extended and subsequently reflected in grain yield and quality. Otherwise, a negative effect on grain yield can be observed [15,16].

5 Conclusion and future perspectives

The architecture of the root in relation to the yield and quality of plants is often overlooked precisely because it is obscured in the soil. Determining the size of the root system by measuring C R appears to be a practical method for monitoring the active part of the root, which also indirectly reflects its size, activity, or volume. The size of the root influences the formation of yield-producing elements of barley and affects the quality of the grain. The application of biostimulators with A. nodosum extract during tillering and elongation can help to increase C R, prolong the root activity, and, at the same time, influence the yield components of barley. Productive tillers were closely correlated with C R (r = 0.912**), the number of grains per plant (r = 0.859**), and their weight (r = 0.850**) at BBCH 70–75. The application of biostimulators with the alga A. nodosum L. and with the lowest dose of N (52 kg/ha) produced similar or higher amounts of yield components compared to high doses of N (80, 110, 140 kg/ha). This reduces the application dose of N. That can positively influence the ecology and economy of growing cereal. The plan of foliar application or biostimulation is also important. It can be ineffective in some cases. In the dry season, we recommend applying the foliar fertilizer in the evening hours to prolong the absorption time and reduce the risk of evaporation of the drops. The measuring of C R can be used for the prediction of some quality parameters of plants or in monitoring the effect of different preparations on the root. Subsequently, it would be appropriate to determine the architecture of the root. Determining the optimal architecture and RSS will be important in breeding future varieties or in better understanding the impact of different stimulants and fertilizers. In case of unfavorable conditions and predictions, it will be possible to intervene in time and influence the plasticity of the root and its growth, as well as the final quality and yield of grain using these preparations.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Internal Grant Agency AF-IGA2019-IP053 of Mendel University in Brno.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Data availability statement: The data generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Shukla PS, Mantin EG, Adil M, Bajpai S, Critchley AT, Prithiviraj B. Ascophyllum nodosum-based biostimulants: Sustainable applications in agriculture for the stimulation of plant growth, stress tolerance, and disease management. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:655. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00655.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Khan W, Rayirath UP, Subramanian S, Jithesh MN, Rayorath P, Hodges DM, et al. Seaweed extracts as biostimulants of plant growth and development. J Plant Growth Regul. 2009;28(4):386–99. 10.1007/s00344-009-9103-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Stamatiadis S, Evangelou L, Yvin J-C, Tsadilas C, Mina JMG, Cruz F. Responses of winter wheat to Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. extract application under the effect of N fertilization and water supply. J Appl Phycol. 2015;27(1):589–600. 10.1007/s10811-014-0344-0.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Craigie JS. Seaweed extract stimuli in plant science and agriculture. J Appl Phycol. 2011;23(3):371–93. 10.1007/s10811-010-9560-4.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Stamatiadis S, Evangelou E, Jamois F, Yvin J-C. Targeting Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. extract application at five growth stages of winter wheat. J Appl Phycol. 2021;33(3):1873–82. 10.1007/s10811-021-02417-z.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Siller A, Hashemi M, Wise C, Smychkovich A, Darby H. Date of planting and nitrogen management for winter malt barley production in the Northeast, USA. Agronomy (Basel). 2021;11(4):797. 10.3390/agronomy11040797.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Shrestha RK, Lindsey LE. Agronomic management of malting barley and research needs to meet demand by the craft brew industry. Agron J. 2019;111(4):1570–80. 10.2134/agronj2018.12.0787.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Jacott CN, Boden SA. Feeling the heat: Developmental and molecular responses of wheat and barley to high ambient temperatures. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(19):5740–51. 10.1093/jxb/eraa326.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Goñi O, Łangowski Ł, Feeney E, Quille P, O’Connell S. Reducing nitrogen input in barley crops while maintaining yields using an engineered biostimulant derived from Ascophyllum nodosum to enhance nitrogen use efficiency. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:664682. 10.3389/fpls.2021.664682.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Calleja-Cabrera J, Boter M, Oñate-Sánchez L, Pernas M. Root growth adaptation to climate change in crops. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:544. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00544.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Chloupek O, Dostál V, Středa T, Psota V, Dvořáčková O. Drought tolerance of barley varieties in relation to their root system size: Drought tolerance and roots size of barley. Plant Breed. 2010;129(6):630–6. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2010.01801.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Kim Y, Chung YS, Lee E, Tripathi P, Heo S, Kim K-H. Root response to drought stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1513. 10.3390/ijms21041513.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Rubio V, Bustos R, Irigoyen ML, Cardona-López X, Rojas-Triana M, Paz-Ares J. Plant hormones and nutrient signaling. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69(4):361–73. 10.1007/s11103-008-9380-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Xiong L, Wang R-G, Mao G, Koczan JM. Identification of drought tolerance determinants by genetic analysis of root response to drought stress and abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):1065–74. 10.1104/pp.106.084632.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Figueroa-Bustos V, Palta JA, Chen Y, Siddique KHM. Early season drought largely reduces grain yield in wheat cultivars with smaller root systems. Plants. 2019;8(9):305. 10.3390/plants8090305.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Figueroa-Bustos V, Palta JA, Chen Y, Stefanova K, Siddique KHM. Wheat cultivars with contrasting root system size responded differently to terminal drought. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1285. 10.3389/fpls.2020.01285.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] El Hassouni K, Alahmad S, Belkadi B, Filali-Maltouf A, Hickey LT, Bassi FM. Root system architecture and its association with yield under different water regimes in durum wheat. Crop Sci. 2018;58(6):2331–46. 10.2135/cropsci2018.01.0076.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Manschadi AM, Christopher J, deVoil P, Hammer GL. The role of root architectural traits in adaptation of wheat to water-limited environments. Funct Plant Biol. 2006;33(9):823–37. 10.1071/fp06055.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Carter AY, Hawes MC, Ottman MJ. Drought-tolerant barley: I. field observations of growth and development. Agronomy (Basel). 2019;9(5):221. 10.3390/agronomy9050221.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Fábián A, Jäger K, Rakszegi M, Barnabás B. Embryo and endosperm development in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) kernels subjected to drought stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(4):551–63. 10.1007/s00299-010-0966-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Středa T, Haberle J, Klimešová J, Klimek-Kopyra A, Středová H, Bodner G, et al. Field phenotyping of plant roots by electrical capacitance – a standardized methodological protocol for application in plant breeding: a Review. Int Agrophys. 2020;34(2):173–84. 10.31545/intagr/117622.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Dietrich RC, Bengough AG, Jones HG, White PJ. A new physical interpretation of plant root capacitance. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(17):6149–59. 10.1093/jxb/ers264.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Brown ALP, Day FP, Stover DB. Fine root biomass estimates from minirhizotron imagery in a shrub ecosystem exposed to elevated CO2. Plant Soil. 2009;317(1–2):145–53. 10.1007/s11104-008-9795-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Postic F, Doussan C. Benchmarking electrical methods for rapid estimation of root biomass. Plant Methods. 2016;12:33. 10.1186/s13007-016-0133-7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Cseresnyés I, Szitár K, Rajkai K, Füzy A, Mikó P, Kovács R, et al. Application of electrical capacitance method for prediction of plant root mass and activity in field-grown crops. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:93. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00093.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Cseresnyés I, Pokovai K, Bányai J, Mikó P. Root electrical capacitance can be a promising plant phenotyping parameter in wheat. Plants. 2022;11(21):2975. 10.3390/plants11212975.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Cseresnyés I, Rajkai K, Takács T. Indirect monitoring of root activity in soybean cultivars under contrasting moisture regimes by measuring electrical capacitance. Acta Physiol Plant. 2016;38(5):122. 10.1007/s11738-016-2149-z.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Mahmoodi B, Moballeghi M, Eftekhari A, Neshaie-Mogadam M. Effects of foliar application of liquid fertilizer on agronomical and physiological traits of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Agrobot. 2020;73(3):7332. 10.5586/aa.7332.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Quintero-Calderón EH, Sánchez-Reinoso AD, Chávez-Arias CC, Garces-Varon G, Restrepo-Díaz H. Rice seedlings showed a higher heat tolerance through the foliar application of biostimulants. Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj Napoca. 2021;49(1):12120. 10.15835/nbha49112120.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Fernández V, Sotiropoulos T, Brown PH, Asociación Internacional de la Industria de los Fertilizantes. Foliar fertilization: Scientific principles and field practices. Paris, France: International Fertilizer Industry Association; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Kumar SV, Baskar K, Solaimalai A, Manoharan S, Manikandan M, Chary GR. Foliar plant nutrition: A drought mitigation management practices under rainfed agriculture. In: Kumar N, editor. Current Research in Soil Science. New Delhi: AkiNik publications; 2022. p. 46–60.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Krouk G. Hormones and nitrate: A two-way connection. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;91(6):599–606. 10.1007/s11103-016-0463-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Chen L, Zhao J, Song J, Jameson PE. Cytokinin dehydrogenase: a genetic target for yield improvement in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(3):614–30. 10.1111/pbi.13305.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Yang D, Luo Y, Kong X, Huang C, Wang Z. Interactions between exogenous cytokinin and nitrogen application regulate tiller bud growth via sucrose and nitrogen allocation in winter wheat. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021;40(1):329–41. 10.1007/s00344-020-10106-3.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Ihsan MZ, El-Nakhlawy FS, Ismail SM, Fahad S, Daur I. Wheat phenological development and growth studies as affected by drought and late season high temperature stress under arid environment. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:795. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00795.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Cseresnyés I, Mikó P, Kelemen B, Füzy A, Parádi I, Takács T. Prediction of wheat grain yield by measuring root electrical capacitance at anthesis. Int Agrophys. 2021;35(2):159–65. 10.31545/intagr/136711.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Supplementation of P-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria, Rhodopseudomonas palustris improved soil fertility, P nutrient, growth, and yield of Cucumis melo L.

- Yield gap variation in rice cultivation in Indonesia

- Effects of co-inoculation of indole-3-acetic acid- and ammonia-producing bacteria on plant growth and nutrition, soil elements, and the relationships of soil microbiomes with soil physicochemical parameters

- Impact of mulching and planting time on spring-wheat (Triticum aestivum) growth: A combined field experiment and empirical modeling approach

- Morphological diversity, correlation studies, and multiple-traits selection for yield and yield components of local cowpea varieties

- Participatory on-farm evaluation of new orange-fleshed sweetpotato varieties in Southern Ethiopia

- Yield performance and stability analysis of three cultivars of Gayo Arabica coffee across six different environments

- Biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different types of plants feeds: Potency as a pest on various agricultural plants

- Antidiabetic activity of methanolic extract of Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn. fruit in alloxan-induced Swiss albino diabetic mice

- Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance

- Nicotinamide as a biostimulant improves soybean growth and yield

- Farmer’s willingness to accept the sustainable zoning-based organic farming development plan: A lesson from Sleman District, Indonesia

- Uncovering hidden determinants of millennial farmers’ intentions in running conservation agriculture: An application of the Norm Activation Model

- Mediating role of leadership and group capital between human capital component and sustainability of horticultural agribusiness institutions in Indonesia

- Biochar technology to increase cassava crop productivity: A study of sustainable agriculture on degraded land

- Effect of struvite on the growth of green beans on Mars and Moon regolith simulants

- UrbanAgriKG: A knowledge graph on urban agriculture and its embeddings

- Provision of loans and credit by cocoa buyers under non-price competition: Cocoa beans market in Ghana

- Effectiveness of micro-dosing of lime on selected chemical properties of soil in Banja District, North West, Ethiopia

- Effect of weather, nitrogen fertilizer, and biostimulators on the root size and yield components of Hordeum vulgare

- Effects of selected biostimulants on qualitative and quantitative parameters of nine cultivars of the genus Capsicum spp.

- Growth, yield, and secondary metabolite responses of three shallot cultivars at different watering intervals

- Design of drainage channel for effective use of land on fully mechanized sugarcane plantations: A case study at Bone Sugarcane Plantation

- Technical feasibility and economic benefit of combined shallot seedlings techniques in Indonesia

- Control of Meloidogyne javanica in banana by endophytic bacteria

- Comparison of important quality components of red-flesh kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis) in different locations

- Efficiency of rice farming in flood-prone areas of East Java, Indonesia

- Comparative analysis of alpine agritourism in Trentino, Tyrol, and South Tyrol: Regional variations and prospects

- Detection of Fusarium spp. infection in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) during postharvest storage through visible–near-infrared and shortwave–near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- Forage yield, seed, and forage qualitative traits evaluation by determining the optimal forage harvesting stage in dual-purpose cultivation in safflower varieties (Carthamus tinctorius L.)

- The influence of tourism on the development of urban space: Comparison in Hanoi, Danang, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Optimum intra-row spacing and clove size for the economical production of garlic (Allium sativum L.) in Northwestern Highlands of Ethiopia

- The role of organic rice farm income on farmer household welfare: Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Exploring innovative food in a developing country: Edible insects as a sustainable option

- Genotype by environment interaction and performance stability of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars grown in Dawuro zone, Southwestern Ethiopia

- Factors influencing green, environmentally-friendly consumer behaviour

- Factors affecting coffee farmers’ access to financial institutions: The case of Bandung Regency, Indonesia

- Morphological and yield trait-based evaluation and selection of chili (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes suitable for both summer and winter seasons

- Sustainability analysis and decision-making strategy for swamp buffalo (Bubalus bubalis carabauesis) conservation in Jambi Province, Indonesia

- Understanding factors affecting rice purchasing decisions in Indonesia: Does rice brand matter?

- An implementation of an extended theory of planned behavior to investigate consumer behavior on hygiene sanitation-certified livestock food products

- Information technology adoption in Indonesia’s small-scale dairy farms

- Draft genome of a biological control agent against Bipolaris sorokiniana, the causal phytopathogen of spot blotch in wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum): Bacillus inaquosorum TSO22

- Assessment of the recurrent mutagenesis efficacy of sesame crosses followed by isolation and evaluation of promising genetic resources for use in future breeding programs

- Fostering cocoa industry resilience: A collaborative approach to managing farm gate price fluctuations in West Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Field investigation of component failures for selected farm machinery used in small rice farming operations

- Near-infrared technology in agriculture: Rapid, simultaneous, and non-destructive determination of inner quality parameters on intact coffee beans

- The synergistic application of sucrose and various LED light exposures to enhance the in vitro growth of Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni)

- Weather index-based agricultural insurance for flower farmers: Willingness to pay, sales, and profitability perspectives

- Meta-analysis of dietary Bacillus spp. on serum biochemical and antioxidant status and egg quality of laying hens

- Biochemical characterization of trypsin from Indonesian skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis) viscera

- Determination of C-factor for conventional cultivation and soil conservation technique used in hop gardens

- Empowering farmers: Unveiling the economic impacts of contract farming on red chilli farmers’ income in Magelang District, Indonesia

- Evaluating salt tolerance in fodder crops: A field experiment in the dry land

- Labor productivity of lowland rice (Oryza sativa L.) farmers in Central Java Province, Indonesia

- Cropping systems and production assessment in southern Myanmar: Informing strategic interventions

- The effect of biostimulants and red mud on the growth and yield of shallots in post-unlicensed gold mining soil

- Effects of dietary Adansonia digitata L. (baobab) seed meal on growth performance and carcass characteristics of broiler chickens: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Analysis and structural characterization of the vid-pisco market

- Pseudomonas fluorescens SP007s enhances defense responses against the soybean bacterial pustule caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines

- A brief investigation on the prospective of co-composted biochar as a fertilizer for Zucchini plants cultivated in arid sandy soil

- Supply chain efficiency of red chilies in the production center of Sleman Indonesia based on performance measurement system

- Investment development path for developed economies: Is agriculture different?

- Power relations among actors in laying hen business in Indonesia: A MACTOR analysis

- High-throughput digital imaging and detection of morpho-physiological traits in tomato plants under drought

- Converting compression ignition engine to dual-fuel (diesel + CNG) engine and experimentally investigating its performance and emissions

- Structuration, risk management, and institutional dynamics in resolving palm oil conflicts

- Spacing strategies for enhancing drought resilience and yield in maize agriculture

- Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types

- Investigating Spodoptera spp. diversity, percentage of attack, and control strategies in the West Java, Indonesia, corn cultivation

- Yield stability of biofertilizer treatments to soybean in the rainy season based on the GGE biplot

- Evaluating agricultural yield and economic implications of varied irrigation depths on maize yield in semi-arid environments, at Birfarm, Upper Blue Nile, Ethiopia

- Chemometrics for mapping the spatial nitrate distribution on the leaf lamina of fenugreek grown under varying nitrogenous fertilizer doses

- Pomegranate peel ethanolic extract: A promising natural antioxidant, antimicrobial agent, and novel approach to mitigate rancidity in used edible oils

- Transformative learning and engagement with organic farming: Lessons learned from Indonesia

- Tourism in rural areas as a broader concept: Some insights from the Portuguese reality

- Assessment enhancing drought tolerance in henna (Lawsonia inermis L.) ecotypes through sodium nitroprusside foliar application

- Edible insects: A survey about perceptions regarding possible beneficial health effects and safety concerns among adult citizens from Portugal and Romania

- Phenological stages analysis in peach trees using electronic nose

- Harvest date and salicylic acid impact on peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) properties under different humidity conditions

- Hibiscus sabdariffa L. petal biomass: A green source of nanoparticles of multifarious potential

- Use of different vegetation indices for the evaluation of the kinetics of the cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) growth based on multispectral images by UAV

- First evidence of microplastic pollution in mangrove sediments and its ingestion by coral reef fish: Case study in Biawak Island, Indonesia

- Physical and textural properties and sensory acceptability of wheat bread partially incorporated with unripe non-commercial banana cultivars

- Cereibacter sphaeroides ST16 and ST26 were used to solubilize insoluble P forms to improve P uptake, growth, and yield of rice in acidic and extreme saline soil

- Avocado peel by-product in cattle diets and supplementation with oregano oil and effects on production, carcass, and meat quality

- Optimizing inorganic blended fertilizer application for the maximum grain yield and profitability of bread wheat and food barley in Dawuro Zone, Southwest Ethiopia

- The acceptance of social media as a channel of communication and livestock information for sheep farmers

- Adaptation of rice farmers to aging in Thailand

- Combined use of improved maize hybrids and nitrogen application increases grain yield of maize, under natural Striga hermonthica infestation

- From aquatic to terrestrial: An examination of plant diversity and ecological shifts

- Statistical modelling of a tractor tractive performance during ploughing operation on a tropical Alfisol

- Participation in artisanal diamond mining and food security: A case study of Kasai Oriental in DR Congo

- Assessment and multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service values in Southwest China’s mountainous and hilly region

- Analysis of agricultural emissions and economic growth in Europe in search of ecological balance

- Bacillus thuringiensis strains with high insecticidal activity against insect larvae of the orders Coleoptera and Lepidoptera

- Technical efficiency of sugarcane farming in East Java, Indonesia: A bootstrap data envelopment analysis

- Comparison between mycobiota diversity and fungi and mycotoxin contamination of maize and wheat

- Evaluation of cultivation technology package and corn variety based on agronomy characters and leaf green indices

- Exploring the association between the consumption of beverages, fast foods, sweets, fats, and oils and the risk of gastric and pancreatic cancers: Findings from case–control study

- Phytochemical composition and insecticidal activity of Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. extract on life span and biological aspects of Spodoptera littoralis (Biosd.)

- Land use management solutions in response to climate change: Case study in the central coastal areas of Vietnam

- Evaluation of coffee pulp as a feed ingredient for ruminants: A meta-analysis

- Interannual variations of normalized difference vegetation index and potential evapotranspiration and their relationship in the Baghdad area

- Harnessing synthetic microbial communities with nitrogen-fixing activity to promote rice growth

- Agronomic and economic benefits of rice–sweetpotato rotation in lowland rice cropping systems in Uganda

- Response of potato tuber as an effect of the N-fertilizer and paclobutrazol application in medium altitude

- Bridging the gap: The role of geographic proximity in enhancing seed sustainability in Bandung District

- Evaluation of Abrams curve in agricultural sector using the NARDL approach

- Challenges and opportunities for young farmers in the implementation of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 of the Republic of Croatia

- Yield stability of ten common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes at different sowing dates in Lubumbashi, South-East of DR Congo

- Effects of encapsulation and combining probiotics with different nitrate forms on methane emission and in vitro rumen fermentation characteristics

- Phytochemical analysis of Bienertia sinuspersici extract and its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities

- Evaluation of relative drought tolerance of grapevines by leaf fluorescence parameters

- Yield assessment of new streak-resistant topcross maize hybrids in Benin

- Improvement of cocoa powder properties through ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted alkalization

- Potential of ecoenzymes made from nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) leaf and pulp waste as bioinsecticides for Periplaneta americana

- Analysis of farm performance to realize the sustainability of organic cabbage vegetable farming in Getasan Semarang, Indonesia

- Revealing the influences of organic amendment-derived dissolved organic matter on growth and nutrient accumulation in lettuce seedlings (Lactuca sativa L.)

- Identification of viruses infecting sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.) in Benin

- Assessing the soil physical and chemical properties of long-term pomelo orchard based on tree growth

- Investigating access and use of digital tools for agriculture among rural farmers: A case study of Nkomazi Municipality, South Africa

- Does sex influence the impact of dietary vitD3 and UVB light on performance parameters and welfare indicators of broilers?

- Design of intelligent sprayer control for an autonomous farming drone using a multiclass support vector machine

- Deciphering salt-responsive NB-ARC genes in rice transcriptomic data: A bioinformatics approach with gene expression validation

- Review Articles

- Impact of nematode infestation in livestock production and the role of natural feed additives – A review

- Role of dietary fats in reproductive, health, and nutritional benefits in farm animals: A review

- Climate change and adaptive strategies on viticulture (Vitis spp.)

- The false tiger of almond, Monosteira unicostata (Hemiptera: Tingidae): Biology, ecology, and control methods

- A systematic review on potential analogy of phytobiomass and soil carbon evaluation methods: Ethiopia insights

- A review of storage temperature and relative humidity effects on shelf life and quality of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit and implications for nutrition insecurity in Ethiopia

- Green extraction of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) phytochemicals: Prospective strategies and roadblocks

- Potential influence of nitrogen fertilizer rates on yield and yield components of carrot (Dacus carota L.) in Ethiopia: Systematic review

- Corn silk: A promising source of antimicrobial compounds for health and wellness

- State and contours of research on roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in Africa

- The potential of phosphorus-solubilizing purple nonsulfur bacteria in agriculture: Present and future perspectives

- Minor millets: Processing techniques and their nutritional and health benefits

- Meta-analysis of reproductive performance of improved dairy cattle under Ethiopian environmental conditions

- Review on enhancing the efficiency of fertilizer utilization: Strategies for optimal nutrient management

- The nutritional, phytochemical composition, and utilisation of different parts of maize: A comparative analysis

- Motivations for farmers’ participation in agri-environmental scheme in the EU, literature review

- Evolution of climate-smart agriculture research: A science mapping exploration and network analysis

- Short Communications

- Music enrichment improves the behavior and leukocyte profile of dairy cattle

- Effect of pruning height and organic fertilization on the morphological and productive characteristics of Moringa oleifera Lam. in the Peruvian dry tropics

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Bioinformatics investigation of the effect of volatile and non-volatile compounds of rhizobacteria in inhibiting late embryogenesis abundant protein that induces drought tolerance”

- Corrigendum to “Composition and quality of winter annual agrestal and ruderal herbages of two different land-use types”

- Special issue: Smart Agriculture System for Sustainable Development: Methods and Practices

- Construction of a sustainable model to predict the moisture content of porang powder (Amorphophallus oncophyllus) based on pointed-scan visible near-infrared spectroscopy

- FruitVision: A deep learning based automatic fruit grading system

- Energy harvesting and ANFIS modeling of a PVDF/GO-ZNO piezoelectric nanogenerator on a UAV

- Effects of stress hormones on digestibility and performance in cattle: A review

- Special Issue of The 4th International Conference on Food Science and Engineering (ICFSE) 2022 - Part II

- Assessment of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid profiles and ratio of omega-6/omega-3 of white eggs produced by laying hens fed diets enriched with omega-3 rich vegetable oil

- Special Issue on FCEM - International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation - Part II

- Special Issue on FCEM – International Web Conference on Food Choice & Eating Motivation: Message from the editor

- Fruit and vegetable consumption: Study involving Portuguese and French consumers

- Knowledge about consumption of milk: Study involving consumers from two European Countries – France and Portugal