Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

-

Anders Holm Welling

Abstract

Objectives

Music festivals are often a source of joy, but also a risk of injury. While previous studies suggest music can relieve pain, its effect has not been tested in festival settings, nor has the effect of high-energy vs soothing music been compared. We hypothesized that guests at a heavy metal music festival would experience less pain when listening to thrash heavy metal compared to relaxing music, with the effect being influenced by music preference and increased with higher alcohol intake.

Methods

This factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial assessed pain during a 5°C cold pressor test (CPT) at a heavy metal festival. Participants were randomized to listen to either Slayer’s “Raining Blood” or Enya’s “Orinoco Flow” during their first CPT, and the opposite song during the second CPT. The primary outcome was pain during the CPT, assessed as area under the curve (AUC). Music fondness and breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) were measured before each CPT.

Results

Forty-five adults, aged 19–58 years, were included, and completed both CPTs. Significantly more pain was reported while listening to Enya (AUC 1,155 [IQR 588–1,507]) vs Slayer (AUC 975 [IQR 682–1,492]) (p = 0.048). Higher BrAC was associated with decreased pain (p = 0.042). Participants with higher fondness of Enya experienced significantly more pain than those who liked the song less (p = 0.021). Fondness of Slayer had no effect on pain perception (p = 0.7).

Conclusion

Listening to thrash heavy metal, specifically “Raining Blood” by Slayer during painful stimuli results in lower pain intensity than listening to relaxing music in the form of “Orinoco Flow” by Enya. The findings’ impact on pain in a clinical setting should be explored.

Abbreviations

- AUC

-

area under the curve

- BMI

-

body mass index

- BrAC

-

breath alcohol concentration

- CI

-

confidence interval

- CPT

-

cold pressor test

- IQR

-

interquartile range

- NRS

-

numeric rank scale

1 Introduction

From a medical perspective, millions of festival guests worldwide are at risk of injuries each year [1,2]. Pain, both acute and chronic, is one of the most common reasons for seeking medical assistance either as the primary symptom or secondary to other diseases [3,4]. Various analgesics are available, but greater efficacy often comes with more severe side effects, particularly with opioids. These side effects can affect all organ systems and, in severe cases, lead to respiratory depression and death [5]. Therefore, exploring non-pharmacological analgesic methods is warranted.

There is a growing body of evidence that music may decrease pain and related stress [6,7], pin-pointed by the Jamaican singer-songwriter Bob Marley, “One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain” [8]. The underlying mechanisms behind reduced pain during music exposure are not fully understood but suggest that listening to music triggers the release of endorphins and other neurotransmitters in the brain associated with pleasure and reward, which in turn inhibits pain perception [9]. Additionally, listening to preferred music may serve as a distraction, diverting attention from painful stimuli and shifting focus to the auditory experience instead [7].

Pain studies involving music have primarily focused on “relaxing music” [10], potentially biased by the researchers’ own preferences (pure speculations from our part), often comparing it to no music or placebo in the form of equal soft non-rhythmic noises [7,8,9]. One study found that heavy metal fans experienced empowerment and joy when listening to death metal while non-fans reported fear and tension [10]. However, the analgesic effects of heavy metal vs soft music, and the role of music preference, remain underexplored.

Another important and potentially synergistic factor to include in heavy metal analgesic studies is the consumption of alcohol. This is particularly pronounced at heavy metal festivals where alcohol consumption is deeply embedded in the culture [11], often as part of the “Nordic” or “Viking” tribute. It could possibly result in a relatively high proportion of medical assessments, and even procedures at the festival being performed while the subject is intoxicated.

While moderate alcohol intake can be enjoyed responsibly by many individuals, and often enhances social skills (up to a certain point) [12], excessive alcohol consumption poses a serious risk, particularly concerning accidents and injuries [13]. Alcohol has a negative impact on cognitive control, decision making, and reaction time [14], and an increased likelihood of accidents is well documented [13]. Studies conclude that alcohol contributes up to 40% of all emergency department injury contacts [15,16].

The aim of this study was to assess pain during a cold pressor test (CPT) while listening to either thrash heavy metal or relaxing music in a real-live setting at a large heavy metal festival, exploring the potential synergy from other related factors especially alcohol and music preference.

We hypothesized that guests at a heavy metal music festival would experience less pain when listening to thrash heavy metal compared to relaxing music, with the effect being influenced by music preference and increased with higher breath alcohol concentration (BrAC).

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

The CoPainHell-study was a 2 × 2 factorial randomized non-blinded crossover study. It was approved by the Danish Regional Ethics Committee (Reg. nr. H-24027715) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06471985, CPH_2024) before participant inclusion. The study adhered to the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Study settings

The CoPainHell-study was conducted during the 2024 version of the annual Copenhell metal festival (19 June – 22 June), located at the old naval shipyard on Refshaleøen, Copenhagen, Denmark. The festival attracts more than 35,000 attendees plus staff and is described as 4 days of “hell on earth,” making it one of the largest heavy metal music festivals in northern Europe [17].

For the non-initiated, Copenhell covers all genres within heavy metal music. It is a genre of rock music that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s, primarily in the United Kingdom and United States, with roots in blues, psychedelic, and acid rock. Heavy metal includes numerous sub-genres including doom, black, death, speed, and thrash metal. The genre is characterized by a thick, monumental sound from distorted guitars, extended guitar solos, emphatic beats, screaming, growling, and loudness. The culture associated with heavy metal often flirts with satanism, gothics, and other “dark” subcultures.

2.3 Study population

Participants were introduced to the study by an advertisement on Copenhell’s Facebook site 10 days prior to the festival. Testing took place from 19 June to 22 June, 2024, at the Festival Site of Copenhell. Before inclusion, participants received verbal and written information about the trial and signed a consent form. All participants were informed about the possibility of pulling out of the study at any time, if they no longer wished to participate. Participants were given four beer tokens after the second CPT test for their participation in the study.

Inclusion criteria were age >18 years old and a BrAC ranging from 0.0 to 1.5‰ while being deemed fit by the investigator at the time of giving informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were skin lesions or wounds on dominant arm, current illness (a flu, cold etc.), diabetes of any degree or other known neuropathies, upper extremity circulatory disease (e.g., Raynaud’s syndrome), or pregnancy.

Post-inclusion pull-out criteria were a BrAC above 2.5‰ and/or if participants were deemed unfit to participate by the investigator before the second CPT.

2.4 Intervention/control

A randomized crossover with active comparator design was chosen to test the hypothesis of “thrash heavy metal” vs “relaxing” music’s effect on pain.

Participants were exposed to two songs: Slayer’s “Raining Blood” and Enya’s “Orinoco Flow” representing two very different musical genres [18]. Randomization decided which song was played during the first CPT, with the opposite song being played during the second CPT. All other aspects of the interventions remained identical.

Wikipedia states that “Raining Blood” (“Reign in Blood” album, Slayer, Def Jam, 1986) is about overthrowing heaven [19]. Raining blood is ranked as the eighth greatest metal song of all time by the magazine Rolling Stone [20], and categorized as thrash metal due to the aggressive fast tempo.

“Orinoco Flow” (”Watermark” album, Enya, Geffen/WEA, 1988) is described by Wikipedia “as the itinerary for the most expensive gap year of all time, representing a new-age cliché of generic ‘bubble bath’ music” [21].

2.5 Outcomes

The primary outcome was the total amount of pain, assessed as the area under the curve (AUC), while participants were exposed to Slayer or Enya and held their lower arm in 5°C cold water.

The secondary outcomes were the following:

Participant’s fondness of “Raining Blood” and “Orinoco Flow.”

BrAC before each pain test session.

Pain at the start of the CPT (t0) and at 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300 s.

Time taken to reach pain tolerance is defined as the time when participants perceived the pain as unbearable and removed their hand from the water.

Heart rate during the CPT at 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, and 300 s.

Other variables recorded were age, sex, height, weight (used to calculate body mass index [BMI]), chronic pain conditions, analgesic medication use, use of other drugs, and weekly alcohol consumption.

2.6 Study set-up

2.6.1 Randomization and blinding

Randomization was accomplished using sealedenvelope.com (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, England) in blocks of six in a 1:1 manner, generated online using smartphones at the site. Generation was done by authors A.H.W. and A.B.N. Participants remained blinded to the randomization until the CPT started. From this point, blinding was not always feasible due to spontaneous singing, headbanging, air guitars (with their non-submerged hand), and other clues indicating the played music. However, majority of the participants sat still with their eyes closed.

Following inclusion and randomization, demographic variables were collected (Table S1).

Demographics – CoPainHell study

| Variable | Overall (n = 45) | Group 1 (n = 21) | Group 2 (n = 24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 20 (44%) | 9 (43%) | 11 (46%) | |

| Age | 36 (19–58) | 37 (19–58) | 35 (19–56) | |

| Height (cm) | 176.8 (174.3–179.2) | 177.2 (173.6–180.9) | 176.4 (172.9–179.9) | |

| Weight (kg) | 85.1 (79.2–91.0) | 83.3 (76.3–90.4) | 86.6 (77.0–96.2) | |

| BMI | 27.3 (25.4–29.3) | 26.9 (23.7–30.0) | 27.7 (25.1–30.4) | |

| Alcohol use | <10 weekly | 39 (87%) | 19 (91%) | 20 (83%) |

| >10 weekly | 6 (13%) | 2 (9%) | 4 (17%) | |

| Use of narcotics | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Chronic pain conditions | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%)* | |

| Daily analgesic use | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%)** | |

| BrAC 1 (n = 34) (‰) | 0.42 (0.00–0.72) | 0.31 (0.00–0.82) | 0.42 (0.20–0.70) | |

| BrAC 2 (n = 40) (‰) | 1.00 (0.60–1.46) | 0.65 (0.36–1.16) | 1.18 (0.84–1.81) | |

| “Raining Blood” | Fondness Rating | 8 (7–9) [5–10] | 8 (7–10) [5–10] | 8 (7.3–9) [6–10] |

| “Orinoco Flow” | Fondness Rating | 6 (3–7) [1–10] | 5 (3–7.5) [1–10] | 6 (4–7) [1–9] |

Age is presented as mean value and range, height, weight, and BMI (body mass index) as means with 95% CI. BrAC variables presented with median and 25, 75 percentiles. “Fondness Rating” is presented with median rating, 25th and 75th percentiles in () and min and max in [].

* = 1 Klippel–Trénaunay syndrome in the leg, 1 neck pain ** = Aspirin 75 mg daily.

2.6.2 Music fondness

Participants were taken to another room where they were exposed to a 30-s teaser of both “Raining Blood” and “Orinoco Flow.” They were asked to rate the two songs between 0 and 10 with 0 being maximum dislike and 10 being maximum enjoyment. The music was played at maximum volume using JBL Tune 760NC headphones (Harman, Stamford, USA).

2.6.3 Breath alcohol test

Before the CPT, the participant BrAC (‰) was assessed using an ALKOtest PRO breathalyzer (ALKOtest ApS, Skodsborg, Denmark). Participants were asked not to drink 15 min before the BrAC test to eliminate false high measurements.

2.6.4 CPT

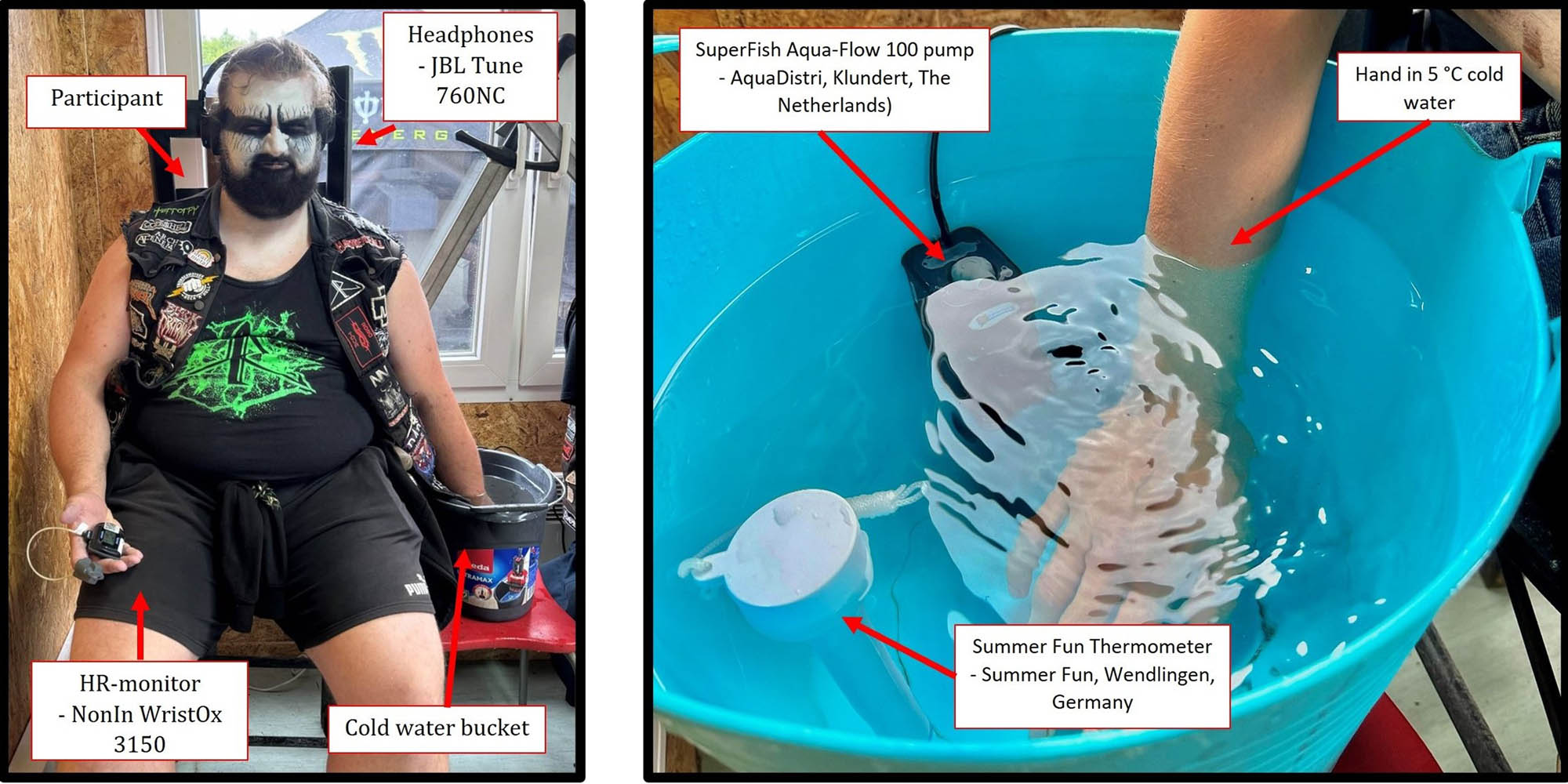

The CPT was chosen as the pain exposure methodology due to the test’s ability to activate both central intrinsic inhibitory and excitatory pain modulation [22,23] and the low risk of injuries compared to mechanical or heat tests, especially in inebriated test subjects. Participants were instructed to submerge their dominant hand and 5 cm of their wrist into the 5°C cold, circulating water for as long as possible up to a maximum of 5 min. The water was cooled by designated refrigerators, checked for temperature before and during each test with a Summer Fun Thermometer (Summer Fun, Wendlingen, Germany) and circulated with a SuperFish Aqua-Flow 100 pump (AquaDistri, Klundert, The Netherlands) (Figure 1).

CoPainHell study set-up. Participant gave written consent to figure appearing in a publication. Heart rate (HR).

Pain scores during the CPT were recorded on a numeric rank scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being intolerable pain. Withdrawal of the arm automatically resulted in assignment of the score 10 for the rest of the test duration.

The participant’s pulse rate during the CPT was monitored with a NonIn WristOx 3150 (Nonin Medical Inc., Minnesota, USA) on the non-dominant hand.

Following the first CPT, participants had a wash-out period of at least 2 h, where they could enjoy the festival on their own before returning to a second CPT test, identical to the first. This time, however, the music would be the opposite song compared to the previous CPT. Once again, the participants had their BrAC measured prior to the CPT as alcohol intake during the wash-out period might have occurred. Participants were, again, asked not to drink 15 min before the BrAC test.

2.7 Sample size

No prior studies provided data for a formal power calculation. However, we aimed to include up to 40 participants, where each participant represents 2.5% of the total population. This allowed for description of normality and 95% confidence intervals (CI). To account for an assumption of 5 potential dropouts, we included 45 participants in total. A significance level of 5% was set for the study.

2.7.1 Statistical analyses

Data are presented with descriptive statistics, parametric or non-parametric where appropriately dependent on the distribution, including means with 95% CI or medians with 25th and 75th interquartile range (IQR). Data are also presented visually by boxplots, scatterplots, and histograms.

2.7.2 Primary analysis

Pain responsiveness is analyzed as cumulated pain by AUC calculations for NRS measurements during CPT using the formula

AUC for the two songs is compared by Wilcoxon’s signed rank test for related samples.

2.7.3 Additional analyses

The AUC pain score and its correlation with potentially predictive factors, including music-fondness, BrAC, BMI, and sex, were analyzed by Spearman’s rho, univariate and subsequent multiple regression analysis. A factor reduction approach was included in the multiple regression analysis to potentially reduce co-variance, but without effect. The results are presented with 95% CI.

All data analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29.0.1.0 (IBM, New York, USA) and Python version 3.9.27 (Python Software Foundation, Delaware, USA).

2.8 Participant and public involvement

As part of the research team, both members of the Heavy Metal community and people enjoying relaxing music were involved in the design of the study from the early phases, in the conduct and analyses of results.

3 Results

A total of >300 people responded by email within 10 h of the online Facebook advertisement on Sunday, 9 June, 2024. The first 45 were invited to participate, and 12 of the invited participants did not show up, after which the next volunteers were included for a total of 45 participants who completed both CPT tests. Participants were randomized to group 1 (n = 21) and group 2 (n = 24). Two participants were mistakenly allocated to group 2 instead of group 1.

Group 1 listened to Slayer during the first CPT and Enya during the second CPT. Group 2 listened to Enya during the first CPT and Slayer during the second CPT. No participant was lost in the washout period and thus 90 CPT tests were available for analysis (Figure 2).

CoPainHell participant flow-chart. Cold pressor test (CPT). Slayer = listening to “Raining Blood,” Enya = listening to “Orinoco Flow.”

Participants had a mean age of 36 years (range 19–58) and the female to male ratio was 20:25 (Table 1). The water temperature was held at a median 5°C (IQR 4–6) throughout all CPTs. Withdrawal of the hand during the first CPT before the 5-min limit occurred with one participant in group 1 and three participants in group 2. During the second CPT only one participant in each group withdrew their hand.

3.1 Primary outcome

Figures 3 and 4 show the pain responses during the first and second CPT. The median AUC-pain difference between Slayer (975 [IQR 682–1,492]) and Enya (1,155 [IQR 588–1,507]) was significant (p = 0.048).

Pain during 5°C CPT listening to Slayer and Enya. Boxplot of pain responses in 45 participants during the two CPTs. Red boxes represent group 1 who listened to Slayer during CPT 1 and Enya during CPT 2. Blue boxes represent group 2 who listened to Enya during CPT 1 and Slayer during CPT 2. Box’s midline represents median with upper and lower parts being 25th and 75th percentiles. NRS = Numeric Rank Scale.

Cumulated pain during 5°C CPT listening to Slayer and Enya. AUC of pain responses in 45 participants during the two CPTs, stratified into listening to Slayer (red) or Enya (blue).

Figure 3 also shows an inverse parabolic pain response, mainly for the Slayer exposure, with increased pain during the first 90 s, followed by reduced pain response. Additionally, a non-significant reduced pain response was seen between the first and second CPT (AUC 1,095 [IQR 795–1,635] vs AUC 1,050 [IQR 682–1,440], respectively, p = 0.06).

As shown in Figures 3 and 4, a substantial variation in pain responses was seen between participants, with a significant positive correlation in pain responses within participants during the two CPTs (rho 0.419, p = 0.04).

3.2 Music fondness

Overall, participants had significantly higher fondness ratings for Slayer than Enya, with a median score of 8 (IQR 7–9) vs 6 (IQR 3–7) (p < 0.001). Six participants rated both songs equally and six participants rated Enya higher than Slayer.

There was a positive correlation between Enya fondness rating and pain score (rho = 0.344, p = 0.021). No similar correlation was observed between Slayer fondness rating and pain score (rho = −0.059, p = 0.7).

Age, sex, and BMI: No significant differences in pain during the two CPTs were observed between the age, BMI, or sex in univariate correlation analyses.

3.3 BrAC

A total of 90 BrAC tests were performed. However, due to drinking immediately before the BrAC test, 16 of the 90 were excluded, leaving 74 BrAC tests to be analyzed. The median BrAC at the first CPT was 0.42‰ (IQR 0.0–0.72‰) and had increased significantly at the second CPT to 1.0‰ (IQR 0.6–1.46‰), p < 0.001. There was a maximum of 1.3‰ at the first CPT and 2.2‰ at the second CPT, with a significant correlation between BrAC and AUC-pain (rho = −0.237, p = 0.042).

The results of the multivariate regression analysis are shown in Table 2, and although none of the variables survived and came out as significant, the analysis suggested increased pain from listening to Enya, being fond of Enya, male sex, low alcohol content, and less pain during the second CPT compared to the first.

Multivariate regression analysis of factors for pain intensity during CPT

| Effect | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1,010 | (620 to 1,402) | <0.001 |

| 2nd CPT | −112 | (−355 to 131) | 0.36 |

| Enya’s “Orinoco Flow” | 107 | (−115 to 329) | 0.34 |

| BMI | 16.5 | (−0.92 to 34) | 0.06 |

| Enya rating | 44.3 | (−5.3 to 94) | 0.08 |

| Sex | −68.1 | (−291 to 155) | 0.55 |

| BrAC | −64.2 | (−288 to 160) | 0.57 |

Intercept: Male-sex, CPT1, Slayer “Raining Blood,” Breath Alcohol Content (BrAC [‰]) = 0, Body Mass Index (BMI) = 0.

3.4 Pulse rate

A relatively high pulse rate was seen in both music groups during the CPTs with a maximum at 30 and 60 s (median 98 bpm [IQR 84–113, maximum 146 bpm]) preceding maximum pain, but without significant differences in overall pulse rate responses (AUC-pulse [p = 0.75]). A trend toward lower pulse rate during the second CPT was seen in both music groups (p = 0.11).

4 Discussion

This study showed that participants experienced significantly more pain during a CPT while listening to Enya’s “Orinoco Flow,” a so-called relaxing song, compared to the high-energetic violent thrash rhythm of Slayer’s “Raining Blood.” Furthermore, we confidently postulate that this was the first time a study like this has been performed in “Hell on Earth.”

This finding contrasts with another recent music-pain study by Valevicius and colleagues arguing that more pain relief is felt from “relaxing music” [24]. Thus, the group assessed pain during thermal heat test while playing songs called “Cotton Blues,” “Jamaicare,” “Légende Celtique,” etc. However, having listened to these songs in the name of science, we, as authors, believe that all tracks fall within the same “relaxing” music category as Enya, which inflicts pain as demonstrated by our study.

Even more interesting was the finding that the participants who had high fondness of Enya at the pre-CPT music assessment reported most pain, both when listening to Enya and Slayer. This correlation was not found in participants who had high fondness of Slayer. This suggests a potentially important predictive and easily obtained risk factor for pain by simply exposing participants to Enya. It may also have a predictive value in other painful scenarios such as postoperative pain, but this needs further exploring.

The observed effect appears to be influenced more by the music genre than the individual’s appreciation of the specific song. Thus, our study “rocks” the boat in music and pain research by challenging the current focus on relaxing music seen in other studies [6,7,9,25]. Future research should include a broader range of music genres and perhaps allow participants to select their own preferred music genre or song, as this approach has been shown to outperform experimenter-selected music in reducing pain [24].

Although the individualized approach will result in a possibly more complicated study design and data management, it could promote participant and public involvement in the study design. A previous functional MRI study allowed subjects to choose their own relaxing music (but not heavy metal music) during noxious stimulation [25]. The study found a modest (10%) pain reduction concomitant with activity in the brain stem and spinal cord, and these neural changes were indicative of engagement of the descending analgetic system. In detail, music during pain vs pain alone engaged specific brain areas, namely, the limbic and paralimbic regions, frontal-temporal, and sensory cortex. Spinal cord activity was located to the rostral ventromedial medulla, the dorsolateral pontine tegmentum and the periaqueductal grey area, and the sixth cervical spinal cord segment. These areas of the brain are involved in affective components of pain and in turn activate the descending analgetic, or inhibitory, system to modulate spinal cord noxious activity [26].

Our study suggests that more upbeat music may produce greater changes, which may also explain the observed reduction in pain midway through the sessions but only when listening to Slayer. This suggests a better activation of descending inhibition via more activity in affective systems.

Our study confirms several other findings from the nociceptive research field. A reduced pain response during the second CPT was registered, which is supported by the descending pain modulation theory or perhaps the anticipation of pain [27,28]. In the regression analysis, the protective effect from female sex on pain was supported [29], although non-significant. An interesting finding in our study was that the pain responses during our CPT were lower than in previous studies [22,23]. While we have no direct explanation for this finding (apart from alcohol and music), it may be a characteristic of the hardcore metal community mentality, which should be explored in future studies.

Furthermore, our study also confirmed the analgesic effect of alcohol and the previously observed focused intake in the heavy metal population, which must be taken into consideration in future studies. Alcohol is, with robust evidence, proven to be an effective analgesic for short term pain [30]. A small study on humans shows that drinking alcohol leads to the release of an endogenous opioid [31]. Animal models suggest that alcohol inhibits the nociceptive transmission via non-opioid pathways by binding to N-methyl-d-Aspartate and GABA receptors at the spinal cord in mice [30,32].

Interestingly, people who had high fondness of Enya experienced significantly more pain than those who had high fondness of Slayer. Previous studies have tried to link different personality characteristics to music preferences [33], but the findings were inconclusive. Most likely the obtained sensation of well-being from listening to music is related to the passion for the melody and rhythm rather than lyric content [34]. This passion induces joy and empowerment, which are factors that in turn may impact pain processing [10]. As the American philosopher Henry David Thoreau said, “When I hear music, I fear no danger. I am invulnerable.” We suggest that this may depend on the exact music.

4.1 Limitations and strengths

The active comparator study design limits our ability to explore the analgesic effect from the individual songs, meaning we cannot determine whether Slayer causes analgesia or Enya induces pain. However, this design demonstrated that thrash heavy metal music is associated with significantly less pain compared to relaxing music during CPT. In contrast to most pain studies that are conducted in quiet surroundings, our study took place in a real-life “hell-ish” setting to increase external validity, although our assessment of facial expressions was impaired by facial painting and therefore not included (please refer Figure 1 again).

The thermometers we used to measure water temperature lack detailed accuracy specifications and could introduce bias. However, since the same thermometer was consistently used in both groups, the potential bias would affect both groups equally. Due to randomization, we believe this reduces the impact of such bias on our comparative results.

Inclusion of a larger cohort with more participants who had a higher fondness for relaxing music might have improved our study. However, gathering heavy metal fans is difficult outside of mosh-pits, and we do believe that standardization of the CPT would be complicated in this setting. Nonetheless, the impressive response rate of over 300 emails within 10 h is impressive and “we salute you.”

5 Conclusion

Listening to thrash heavy metal, specifically “Raining Blood” by Slayer during painful stimuli results in lower pain intensity than listening to relaxing music in the form of “Orinoco Flow” by Enya. The findings’ impact on pain in a clinical setting should be explored.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Louise Haahr Nielsen, Trine Hildebrandt Nielsen, Aslak Broby Johansen, Julia Højrup Blauert, and Casper Pedersen for their support with logistics and study procedures. A special thanks to the restaurant Alchemist in Copenhagen for lending us a refrigerator, and to the Copenhell crew and participants without whom this study would not been possible.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013) and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board (Danish Regional Ethics Committee (Reg. no. H-24027715)).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards. Any identifiable patients have provided their signed consent to publication.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. Anders H. Welling contributed to the conceptualization, design, data collection, data-analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript review. Anders B. Nathansen contributed to the design and data collection. Sandra E. L. T. Pitter contributed to the design, data collection, data-analysis, and manuscript review. Jesper Mølgaard contributed to the conceptualization, design, and data analysis. Anthony H. Dickenson contributed to the conceptualization, data analysis, and manuscript review. Eske K. Aasvang contributed to the conceptualization, design, data collection, data-analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript review.

-

Competing interests: The study was supported by Copenhell (in the form of beer tokens and study equipment), but the sponsor had no role in the planning or conduction of the study. The authors state no other conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The salary for employees was funded by departmental funds administered by EKA. The study materials (a total of 3,000 Euros) were funded by the Copenhell festival. Copenhell festival had no role in the study conceptualization, design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or submission of the article for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and all authors had full access to all the data in the study. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

-

Supplementary material: Table S1 (CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial).

References

[1] Stagelund S, Jans Ø, Nielsen K, Jans H, Wildgaard K. Medical care and organisation at the 2012 Roskilde Music Festival: A prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58:1086–92. 10.1111/aas.12342.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Hutton A, Ranse J, Verdonk N, Ullah S, Arbon P. Understanding the characteristics of patient presentations of young people at outdoor music festivals. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2014;29:160–6. 10.1017/S1049023X14000156.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:165–9. 10.1053/ajem.2002.32643.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Hasselström J, Liu‐Palmgren J, Rasjö‐Wrååk G. Prevalence of pain in general practice. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:375–85. 10.1016/S1090-3801(02)00025-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, Sehgal N, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11:105–10. 10.36076/ppj.2008/11/s105.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Garza-Villarreal EA, Wilson AD, Vase L, Brattico E, Barrios FA, Jensen TS, et al. Music reduces pain and increases functional mobility in fibromyalgia. Front Psychol. 2014;5:90. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Linnemann A, Kappert MB, Fischer S, Doerr JM, Strahler J, Nater UM. The effects of music listening on pain and stress in the daily life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:1–10. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00434.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Arnold CA, Bagg MK, Harvey AR. The psychophysiology of music-based interventions and the experience of pain. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1–17. 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1361857.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Schaefer HE. Music-evoked emotions - Current studies. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:600. 10.3389/fnins.2017.00600.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Thompson WF, Geeves AM, Olsen KN. Who enjoys listening to violent music and why? Psychol Pop Media Cult. 2019;8:218–32. 10.1037/ppm0000184.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Butkovic A, Rancic Dopudj D. Personality traits and alcohol consumption of classical and heavy metal musicians. Psychol Music. 2017;45:246–56. 10.1177/0305735616659128.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Fairbairn CE, Sayette MA. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1361–82. 10.1037/a0037563.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Taylor B, Irving HM, Kanteres F, Room R, Borges G, Cherpitel C, et al. The more you drink, the harder you fall: A systematic review and meta-analysis of how acute alcohol consumption and injury or collision risk increase together. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:108–16. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Bjork JM, Gilman JM. The effects of acute alcohol administration on the human brain: Insights from neuroimaging. Neuropharmacology. 2014;84:101–10. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.039.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Chikritzhs T, Livingston M. Alcohol and the risk of injury. Nutrients. 2021;13:2777. 10.3390/nu13082777.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Roche AM, Watt K, McClure R, Purdie DM, Green D. Injury and alcohol: a hospital emergency department study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2001;20:155–66. 10.1080/09595230124932.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] COPENHELL. Copenhell Profile. CopenhellDk; n.d. https://www.copenhell.dk/en/profile (accessed July 9, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Tillekens G, Mulder J. The four dimensions of popular music. The Netherlands: SoundscapesInfo; 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Wikipedia.org. Raining Blood. WikipediaOrg; n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raining_Blood (accessed July 9, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

[20] ROLLING STONE. The 100 Greatest Heavy Metal Songs of All Time. RollingstoneCom 2023. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-lists/100-greatest-heavy-metal-songs-1234688425/procreation-of-the-wicked-celtic-frost-1234689551/(accessed July 9, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Wikipedia.org. Orinoco Flow. WikipediaOrg; n.d. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orinoco_Flow (accessed July 9, 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Johansen A, Schirmer H, Stubhaug A, Nielsen CS. Persistent post-surgical pain and experimental pain sensitivity in the Tromsø study: Comorbid pain matters. Pain. 2014;155:341–8. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Streff A, Kuehl LK, Michaux G, Anton F. Differential physiological effects during tonic painful hand immersion tests using hot and ice water. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:266–72. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.05.011.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Valevicius D, Lépine Lopez A, Diushekeeva A, Lee AC, Roy M. Emotional responses to favorite and relaxing music predict music-induced hypoalgesia. Front Pain Res. 2023;4:1–12. 10.3389/fpain.2023.1210572.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Dobek CE, Beynon ME, Bosma RL, Stroman PW. Music modulation of pain perception and pain-related activity in the brain, brain stem, and spinal cord: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Pain. 2014;15:1057–68. 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.07.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Bannister K, Dickenson AH. What the brain tells the spinal cord. Pain. 2016;157:2148–51. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000568.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Peng W, Huang X, Liu Y, Cui F. Predictability modulates the anticipation and perception of pain in both self and others. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2019;14:747–57. 10.1093/scan/nsz047.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Carlsson K, Andersson J, Petrovic P, Petersson KM, Öhman A, Ingvar M. Predictability modulates the affective and sensory-discriminative neural processing of pain. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1804–14. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.027.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Yang MMH, Hartley RL, Leung AA, Ronksley PE, Jetté N, Casha S, et al. Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025091. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025091.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Thompson T, Oram C, Correll CU, Tsermentseli S, Stubbs B. Analgesic effects of alcohol: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled experimental studies in healthy participants. J Pain. 2017;18:499–510. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.11.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Mitchell JM, O’Neil JP, Janabi M, Marks SM, Jagust WJ, Fields HL. Alcohol consumption induces endogenous opioid release in the human orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(116):116ra6. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Neddenriep B, Bagdas D, Contreras KM, Ditre JW, Wolstenholme JT, Miles MF, et al. Pharmacological mechanisms of alcohol analgesic-like properties in mouse models of acute and chronic pain. Neuropharmacology. 2019;160:107. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107793.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Greenberg DM, Baron-Cohen S, Stillwell DJ, Kosinski M, Rentfrow PJ. Musical preferences are linked to cognitive styles. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131151. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131151.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Powell M, Olsen KN, Vallerand RJ, Thompson WF. Passion for violently themed music and psychological well-being: a survey analysis. Behav Sci. 2022;12:486. 10.3390/bs12120486.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)