Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate a panel of inflammatory biomarkers in plasma from forklift truck operators (FLTOs) and healthy controls, and their relation to neck pain characteristics.

Methods

From employees in a warehouse, 26 FLTOs were recruited and 24 healthy age- and sex-matched controls (CONs) were recruited via advertisement. The inclusion criterion for FLTOs was that they should operate reach decker and/or counterbalanced tilting mast forklift trucks. All participants were asked to answer a questionnaire covering demographic data, pain intensity numeric rating scale (NRS), anatomical spread, psychological distress, and health aspects. Pain sensitivity was measured using a pressure algometer. Blood samples were collected and analyzed for inflammatory proteins in plasma using a panel of 71 cytokines and chemokines. Multivariate data analysis including orthogonal partial least square-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed to identify significant biomarkers.

Results

Thirty percent of FLTOs reported NRS > 3 in the neck. Shoulder pain was common in 26% of the FLTOs. Pain and discomfort that most often prevented completion of activities were in the neck (20%), lower back (32%), and hips (27%). The FLTOs reported significantly (p = 0.04) higher levels of anxiety than the CON group and they had significantly lower pressure pain thresholds in the trapezius muscle on both right (p < 0.001) and left sides (p = 0.003). A significant OPLS-DA model could discriminate FLTOs from CON based on nine inflammatory proteins where the expression levels of four proteins were upregulated and five proteins were downregulated in FLTOs compared to CONs. Twenty-nine proteins correlated multivariately with pain intensity.

Conclusions

The profile of self-reported health, pain intensity, sensitivity, and plasma biomarkers can discriminate FLTOs with pain from healthy subjects. A combination of both self-reported and objective biomarker measurements can be useful for better understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying work-related neck and shoulder pain.

1 Introduction

Neck pain is a prevalent problem in the general and working population causing reduced work ability and sick leave [1]. The prevalence of chronic neck and shoulder pain is high in subjects with high exposure to awkward working positions, repetitive movements, and movements with high precision [2,3,4]. Neck pain may be a feature of many disorders that occurs above the shoulder blades [5]. Although several muscles of the shoulder region are affected [6], chronic trapezius myalgia is a very frequent clinical diagnosis in subjects reporting chronic neck/shoulder pain [7]. Although several pathophysiological models have been proposed, the pathogenic processes underlying the translation of exposure to muscle pain risk factors have not been sufficiently elucidated. Patients with pain in the neck and shoulder region often report that their symptoms are aggravated by monotonous and heavy work tasks [8]. Recently, it has been reported that forklift truck operators (FLTOs) have an increased risk of neck pain [9]. They are exposed to repetitive arm work, unnatural neck positions, and extensive neck rotation when driving, loading, and unloading the forklift on shelves at different levels [10]. However, studies measuring neck pain characteristics especially objective markers among a working cohort such as FLTOs are lacking. It has been reported that muscle structure and changes in muscle biochemistry related to inflammatory processes in particular substances related to nociception and pain such as glutamate, serotonin, prostaglandin E2, bradykinin, and IL6 could be of importance [11,12,13]. In a field study during 8 h work, significantly increased levels of glutamate, an important signaling molecule in the development of pathological pain, have been reported in women with chronic work-related trapezius myalgia [14]. Inflammatory biomarkers associated with pain in neck and upper extremities have been reported previously [15,16,17], and in a review by Barbe et al. [18], it was suggested that inflammation may play a role in work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Due to the complexity of the pain system, no unidimensional reliable biomarker for pain has been identified to date. It is more reliable to identify clusters of interacting molecules that together provide an improved understanding of the activated molecular pathways in chronic pain that can be detected in blood. Multivariate data analysis (MVDA) considers the complex intercorrelations between the concentrations of different molecules and is designed to handle data sets with low subject-to-variable ratios and multiple intercorrelated variables [19].

The aim of this study was to analyze inflammatory biomarkers in plasma from FLTOs with and without reported neck and shoulder pain and healthy controls and their correlation with pain characteristics using advanced multivariate data analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and procedure

This case–control study was performed in 2017 in a Swedish warehouse. FLTOs were recruited among the employees in the warehouse and healthy age- and sex-matched subjects were recruited via advertisement. A total number of 26 FLTOs and 24 controls (CONs) were included in this study. The inclusion criteria for FLTOs were that they should operate reach decker and/or counterbalanced tilting mast trucks. All participants answered a questionnaire covering demographic data, pain intensity, anatomical spreading, psychological distress, and health aspects. Measurement of pain sensitivity was performed, and blood samples were collected from all subjects.

All participants received verbal and written information about the study before informed written consent was obtained and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board at the University of Linköping, Sweden (Dnr: 2013/418-31, Dnr: 2016/477-32).

2.2 Self-reported measures

2.2.1 Numeric rating scale (NRS)

Pain intensity in the previous 7 days was reported using a NRS (0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain). The subjects were instructed to report an average pain rating over the last 7 days. The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire [20] was used to identify areas of the body causing musculoskeletal problems. Hence, subjects rated pain using a body map to indicate ten symptom sites: neck, shoulders, upper back, elbows, upper back, low back, wrist/hands, hips/thighs, knees, and ankles/feet and rated average pain during the last 7 days at each site. There were three FLTOs who did not answer questions regarding these ten symptom sites.

The FLTOs rated pain intensity in the neck and the shoulders before and after a working day. High pain was defined as NRS > 4.

2.2.2 Psychological distress

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for measuring the psychological distress. The subscales HADS-depression and HADS-anxiety have seven items, scoring range between 0 and 21, in which a lower score indicates a lower possibility of anxiety or depression. HADS is frequently used in clinical practice and research and has good psychometric characteristics [21,22].

2.2.3 Quality of life

The quality-of-life scale (QOLS) is a 16-item instrument that measures the quality of life which includes material and physical well-being, relationships with other people, social, community and civic activities, personal development, and fulfillment [23]. The QOLS is scored by adding up the score on each item to yield a total score for the instrument. Scores can range from 16 to 112.

2.3 Measurements of pressure pain threshold (PPT)

A handheld manual electronic pressure algometer (Somedic, Hörby, Sweden) was used to assess the PPT in kilopascal (kPa) [24]. The pressure was applied at a rate of 30 kPa/s, with a 1-cm diameter probe. All participants were instructed to press a button when they felt the first sensation of pain, not merely pressure. The maximum pressure was set at 600 kPa, at which point the application of pressure ceased. The test sites were located at three points along the upper part of the trapezius muscle, bilaterally, and at three points over the belly of the tibialis anterior muscle, bilaterally. The tibialis anterior muscle was used as control muscle. Each location was tested three times, and the mean value was used.

2.4 Sample collection

Venous blood samples were collected (FLTOs = 25 and CONs = 24) in two 8 ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes before the physical function tests and PPT measurements. One FLTO was not able to provide blood samples. The samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min and the separate layers of plasma from the two blood samples, approximately 5–6 ml in total, were collected into a 12 ml Falcon tube and mixed gently. The plasma was aliquoted in small portions and stored at −86°C until analysis.

2.5 Measurements of biomarkers

A commercially available panel of 71 pro- and anti-inflammatory proteins (cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) (U-PLEX, Meso Scale Discovery, Maryland, USA) was used for biochemical analyses on plasma (see Table S1). The plasma samples were thawed and analyzed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The light intensity of all the different proteins examined was converted into concentrations (pg/ml). Data were collected and analyzed using the MESO QUICKPLEX SQ 120 instrument equipped with DISCOVERY WORKBENCH data analysis software.

2.6 Statistical analysis

For the analysis of self-reported data, Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the FLTOs and CONs, and data were presented as median value (min–max). The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics (version 24.0; IBM Corporation, Route 100 Somers, New York, USA).

MVDA was used to investigate the differences between the concentration of the biomarkers in FLTOs and CONs, and the clinical data using SIMCA-P+ version 17.0 (Sartorius, Umeå, Sweden). MVDA is a recommended method in biomarker research where the number of variables exceeds the number of observations. The procedure to compute multivariate correlation models has been described earlier [25] and was in accordance with the methodology presented by Wheelock [19]. Partial component analysis (PCA) including only biomarkers was performed as the first step to investigate outliers. PCA extracts and displays systematic variation in the data matrix. The presence of any statistically measured outliers was detected using a score plot in combination with Hotelling’s T 2 (strong outliers) and distance to model in X-space (moderate outliers). Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was used to investigate the multivariate correlation between group membership and inflammatory proteins. The following parameters are reported in the evaluation of the OPLS-DA model. Variable influence on projection (VIP) refers to which biomarkers that are most important to group separation. p(corr) is the loading of each X-variable scaled as a correlation coefficient that is comparable between models. Biomarkers with VIP ≥ 1.0 (or VIPpred if more than one component is identified) and |p(corr)| > 0.3 are considered to be significant. R 2 describes the goodness of fit – the fraction of sum of squares of all the variables explained by a principal component and Q 2 describes the goodness of prediction – the fraction of the total variation of the variables that can be predicted using principal component cross-validation methods. Q 2 should not be greater than R 2 and the differences should not be greater than 0.3. coefficient of variation-analysis of variation (CV-ANOVA), which is a SIMCA diagnostic tool for assessing model reliability, was also used and p value ≤0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant model. The correlation between significant biomarkers and pain intensity was analyzed where NRS = 0–3 was defined as low pain, NRS = 4–6 was defined as high pain, and NRS = 7–10 was defined as severe pain.

3 Results

3.1 Self-reported data

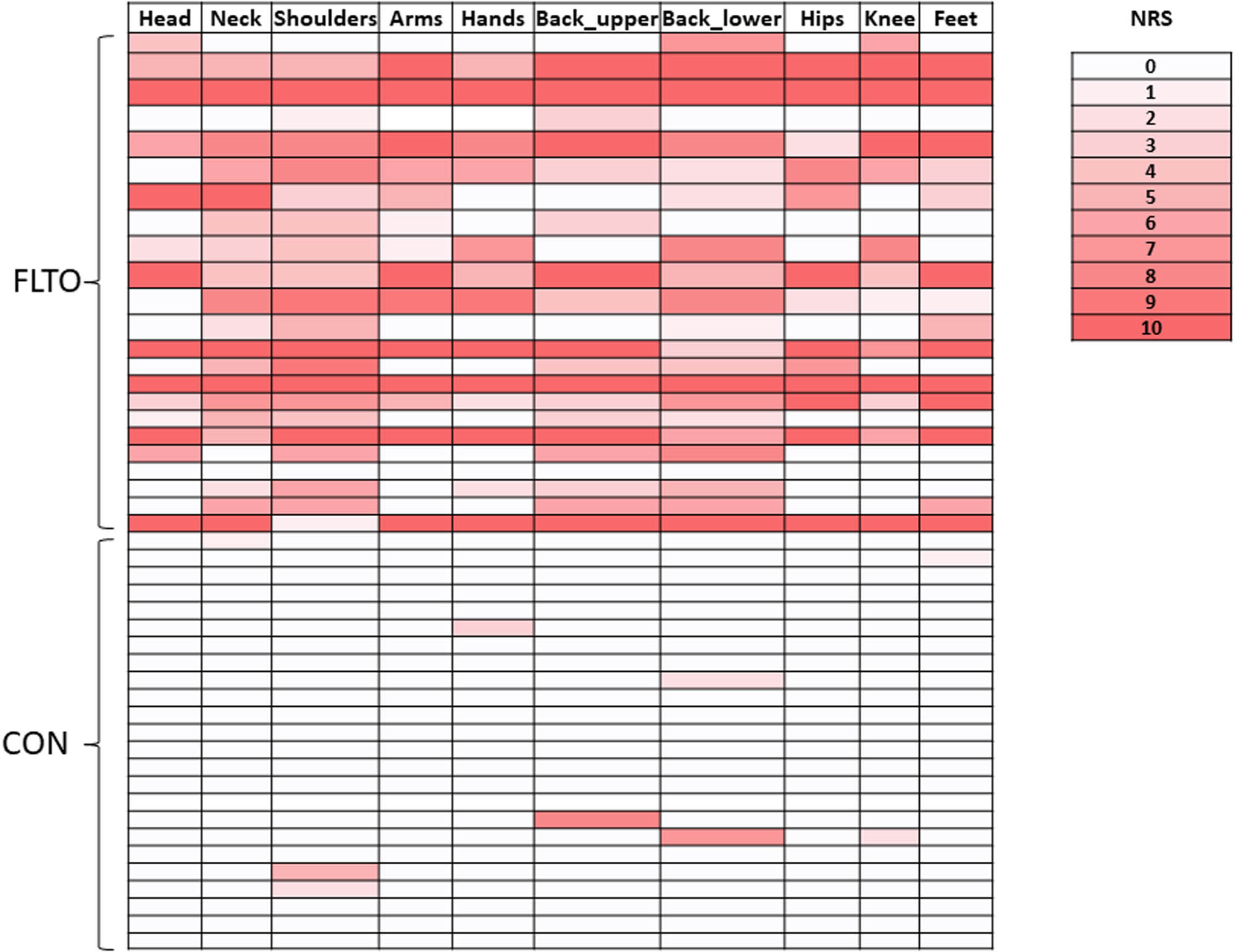

The pattern of average pain intensity during the last month in the head, neck, shoulder, arms, hands, back-upper, back-lower, hips, knee, and feet is presented for FLTOs (n = 23) and CONs (n = 24) in Figure 1. In FLTOs, 82% reported musculoskeletal symptoms in at least one body part during the past 7 days. The most prevalent sites for symptoms (NRS > 3) among the FLTOs were the neck (30%), shoulders (26.3%), and lower back (26.3%). Pain and discomfort which frequently limited various activities were in the neck (20%), lower back (31.6%), and hip (26.9%).

Individual pain intensity ratings according to NRS for the different anatomical sites in forklift truck operators (FLTOs) and in healthy controls (CONs).

As shown in Figure 2, the number of subjects who rated high pain (NRS > 4) in the neck and shoulder after a working day increased from five to nine afterward. There were significant differences in pain intensity between the FLTOs and CON groups (Table 1). The FLTOs reported significantly higher anxiety levels (p < 0.05) than the CON group (Table 1).

Pain intensity in the neck and the shoulders for the 7 last days, together with before and after a working day in FLTOs. Pain intensity ratings were dichotomized into two groups. The gray color represents pain intensity NRS 0–3 and the black color represents NRS 4–10.

Self-reported data for forklift operators (FLTOs) and healthy controls (CONs)

| Variables | FLTO (n = 23) | Healthy (n = 24) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42 (21–67) | 37 (23–56) | 0.240 |

| NRS – head | 3 (0–10) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| NRS – neck | 5 (0–10) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| NRS – shoulder | 6 (0–10) | 0 (0–5) | <0.001 |

| NRS – arms | 5 (0–10) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| NRS – hands | 3.5 (0–10) | 0 (0–3) | <0.001 |

| NRS – upper back | 4 (0–10) | 0 (0–8) | <0.001 |

| NRS – low back | 6 (0–10) | 0 (0–7) | <0.001 |

| NRS – hips | 2 (0–10) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| NRS – knee | 3 (0–10) | 0 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| NRS – feet | 3 (0–10) | 0 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| HAD – depression | 2 (0–18) | 2 (0–10) | 0.921 |

| HAD – anxiety | 4 (0–20) | 2 (0–8) | 0.041 |

| PCS | 7 (0–44) | 7 (0–15) | 0.923 |

Abbreviations: NRS, pain intensity measured using a numeric rating scale; PCS, pain catastrophizing.

Values are presented in median (minimum-maximum). The pain rating (NRS) is average pain over the last 7 days at each site.

The statistically significant p-values are marked in bold.

3.2 Pain sensitivity

The mean value for PPTs was significantly lower in the trapezius muscle (both right [p < 0.001] and left [p = 0.003] sides) in the FLTOs compared to CONs: trapezius right: FLTOs = 352 ± 142 kPa vs CON = 531 ± 107; trapezius left: FLTOs = 401 ± 148 kPa vs CON = 525 ± 115 kPa. There were significantly (p = 0.03) lower PPT in the tibialis muscle left (460 ± 157 kPa) in FLTOs compared to CON (567 ± 74 kPa). In the right tibialis muscle, the FLTOs had lower PPT (483 ± 179 kPa) than CON (564 ± 68 kPa) but were not statistically significant (p = 0.60).

3.3 Biochemical analysis

Multivariate data analysis was performed to identify differences in the levels of inflammatory proteins in plasma from FLTOs and CONs. A significant OPLS-DA model (two components, R 2 = 0.83, Q 2 = 0.45, CV-ANOVA p = 5.75 × 10−5) could discriminate FLTOs from CONs based on nine inflammatory proteins (Figure 3 and Table 2). Levels of M-CSF, IL-16, MIP-1α, and IL-17A/F were higher in FLTOs and IL-9, MIP1B/CCL4, IL-17A, and Eotaxin were lower compared to CON (Figure 4).

Score plot of the OPLS-DA model (two components, R 2 = 0.83, Q 2 = 0.45 CV-ANOVA p = 5.75 × 10−5) discriminating FLTOs from CON based on inflammatory proteins; the most important proteins are shown in Table 2. The colors refer to reported pain intensity (NRS) in the neck from 0 (blue) to 10 (red) as shown in the color gradient staple on the right.

Most important proteins (VIPpred > 1.0) for the discrimination between FLTOs and health controls (CON)

| Proteins | VIPpred | p(corr) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-CSF | 2.51 | 0.59 | <0.001 |

| IL-16 | 2.46 | 0.58 | <0.001 |

| MIP1α/CCL3 | 1.81 | 0.43 | 0.020 |

| IL-9 | 1.78 | −0.42 | 0.034 |

| MIP1B/CCL4 | 1.70 | −0.40 | 0.058 |

| IL-17A/F | 1.68 | 0.40 | 0.010 |

| IL-17A | 1.57 | −0.37 | 0.119 |

| Eotaxin | 1.46 | −0.35 | 0.479 |

| Eotaxin-3 | 1.42 | 0.34 | 0.001 |

The sign of p(corr) represents increased () and decreased (−) levels of the proteins in FLTOs. Thus, the levels of M-CSF, IL-16, MIP-1α, and IL-17A/F were higher in FLTOs compared to CON. The p-values in the right column represent statistical significance (p < 0.05) in the concentrations of the biomarkers between FLTOs and CONs using univariate nonparametric data analysis Mann–Whitney.

![Figure 4

Concentrations of most important proteins (i.e., variable of importance [VIP] > 1) in forklift operators (FLTOs) and in healthy controls (CONs).](/document/doi/10.1515/sjpain-2023-0142/asset/graphic/j_sjpain-2023-0142_fig_004.jpg)

Concentrations of most important proteins (i.e., variable of importance [VIP] > 1) in forklift operators (FLTOs) and in healthy controls (CONs).

3.4 Multivariate correlation analysis

A significant OPLS (two components, R 2 = 0.89, Q 2 = 0.56, CV-ANOVA p = 0.005) was achieved when investigating pain intensity of the shoulders as a dependent variable (Y variable) and all inflammatory proteins as X variables (Figure 5). The size of the circles refers to NRS in the shoulder and the color refers to NRS in the neck. The bigger circle indicates higher pain in the shoulder and the red color indicates severe pain in the neck. Subjects with high pain in the shoulder and neck are clustering on the right side of the ellipse. There were 27 proteins (VIPpred > 1.0, |p(corr)| > 0.4) that multivariately correlated to pain intensity (NRS) and they are shown in Table 3. The mean concentration of the sex most important proteins (VIPpred > 1.50) in subjects with low pain (NRS 0–3), moderate pain (NRS 4–6), and severe pain (NRS 7–10) are shown in Figure 6 indicating a low concentration of inflammatory biomarkers in FLTOs with low pain.

OPLS (orthogonal partial least) model showing multivariate correlation of pain in the shoulder (NRS-shoulders as y-variable) to inflammatory biomarkers in FLTOs. The size of the circles refers to NRS in the shoulder and the color refers to NRS in the neck. The bigger circle indicates higher pain in the shoulder and the red color indicates severe pain in the neck. Subjects with high pain in the shoulder and neck are clustering on the right side of the ellipse.

Most important proteins (VIPpred > 1.0 and p(corr) > 0.40) that multivariately correlated with pain intensity in the forklift operators

| Proteins | VIPpred | p(corr) |

|---|---|---|

| IL-17C | 1.93 | 0.73 |

| MCP-3 | 1.72 | 0.65 |

| IL-22 | 1.69 | 0.64 |

| IL-23 | 1.63 | 0.61 |

| IL-17B | 1.55 | 0.58 |

| IL-9 | 1.51 | 0.57 |

| VEGF-A | 1.50 | 0.56 |

| IL-21 | 1.47 | −0.55 |

| IL-33 | 1.46 | 0.55 |

| IL-1β | 1.42 | 0.53 |

| IL-12p70 | 1.41 | 0.53 |

| IL-17F | 1.40 | 0.53 |

| IL-13 | 1.39 | 0.52 |

| I-309 | 1.35 | 0.51 |

| IL-29/IFN-L1 | 1.32 | −0.49 |

| IL-3 | 1.31 | 0.49 |

| IL-17A/F | 1.30 | 0.49 |

| IL-8 | 1.29 | 0.49 |

| TRAIL | 1.26 | 0.47 |

| FLT3L | 1.25 | −0.47 |

| IL-7 | 1.25 | 0.47 |

| IL-12/IL-23p40 | 1.23 | −0.46 |

| IFN-β | 1.19 | 0.45 |

| IL-17D | 1.13 | 0.43 |

| IL-17E/IL-25 | 1.11 | 0.42 |

| IL-2 | 1.10 | 0.41 |

| IL-31 | 1.07 | 0.40 |

The sign of p(corr) represents (−) negative and () positive association of proteins to pain intensity.

The distribution of the most important proteins correlated with pain intensity in shoulders in FLTOs. The FLTOs are grouped according to their pain intensity, i.e., low pain (NRS 0–3), moderate pain (NRS 4–6), and severe pain (NRS 7–10). NRS, numeric rating scale.

4 Discussion

This study identified a group of inflammatory biomarkers in plasma that were altered in FLTOs with reported neck pain compared to CONs. Further, we found concentrations of several of the biomarkers that multivariately correlated to pain in shoulders.

In FLTOs, 82% reported musculoskeletal symptoms in at least one body part during the past 7 days. FLTOs reported problems mainly in the neck, shoulders, and lower back. These results indicate that FTLOs exhibit signs of chronic neck pain and are in agreement with the previous study by our research group where the FLTO cohort was studied using questionnaires and inclinometer with video recording [10]. The load of the work differed depending on the type of forklift truck that was used. There were repeated working positions with longer moments with a strongly rotated head or strong extension of the neck. In addition, there were longer periods during which there were no opportunities for support to relieve the arms. In this study, we found significantly higher pain sensitivity (low PPT) in trapezius muscle in FLTOs compared to CONs; this might be a consequence of the load of the work on the neck and arms. Reduced PPT in occupationally active subjects with symptoms of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders [26] has been reported to be a relevant measurement in working populations suffering from musculoskeletal disorders [27,28,29,30]. Unfavorable working posture and excessive repetition are known physical factors that can lead to work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) [31]; therefore, future intervention studies aimed to decrease the risk of MSDs among FLTOs are warranted.

The need for objective biomarkers for the improvement of diagnostic tools and understanding mechanisms behind work-related neck and shoulder pain is desirable [13]. Genetic variants associated with neck and shoulder pain have been reported recently from the UK biobank cohort [32]. The role of inflammation in developing pain in subjects with work-related MSD has been highlighted [18]. As a result, this study measured a panel of 71 inflammatory proteins in plasma to capture the biological mechanism ongoing in FLTOs with neck and shoulder pain. We found that the concentrations of M-CSF, IL-16, MIP-1α/CCL3, IL-17A/F, and Eotaxin-3/CCL26 were increased in plasma from FLTOs compared to healthy subjects. M-CSF (macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1) is a cytokine that promotes the release of proinflammatory chemokines such as MIP-1α/CCL3 and Eotaxin-3/CCL26, and thereby, those proteins together play an important role in innate immunity and in inflammatory processes. IL-16 is a lymphocyte chemoattractant protein with a broad spectrum of both pro- and anti-inflammatory biological activities. Increased levels of IL-16 have been reported in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) showing a potential role as a mediator of the inflammatory process [33]. IL-17A/F belongs to the IL-17 family (A–F), which is involved in driving inflammatory response [34]. IL-17 can directly induce chronic pain by binding to the receptor IL-17R or indirectly induce chronic pain by regulating infiltrating immune cells and pain mediator production [35]. It has been reported that IL-17A acts as a pain mediator in inflammation-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia [36]. Increased levels of IL-17A have been reported in patients with RA and animal models of neuropathic, low back, and cancer pain [37,38,39,40]. In patients with lumbar disc herniation, an increased level of IL-17 was positively correlated with pain intensity preoperatively [41]. Interestingly in this study, the levels of two other family members, IL-17C and IL-17B, showed a positive correlation with reported pain intensity where FTLOs who reported pain 7–10 had increased concentrations of IL-17C and IL-17B. The role of the immune system in chronic pain has been highlighted previously [42]. Elevated levels of MIP-1α/CCL3 in subjects with chronic neck pain have been reported [17] suggesting that a systemic inflammatory response is present in subjects with chronic neck pain. The presence of widespread inflammation in work-related MSDs has been reported by measuring pro-inflammatory cytokines in a rat model [43].

The concentrations of several of the inflammatory proteins correlated with self-reported pain intensity in FLTOs where a trend from low to high concentration mirrored the reported pain intensity from low to severe pain. Recently, Dong et al. reported that musculoskeletal pain among workers with posture load was associated with an increase in inflammatory cytokines [44]. Elevated levels of several chemokines have been reported in patients with whiplash injuries suggesting a local tissue injury can be detected as a systemic up-regulation of chemokine [45]. The FLTOs showed significantly higher pain sensitivity and had increased levels of inflammatory biomarkers. All these findings are consistent and support the previously reported role of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the modulation and regulation of chronic neck pain and work-related MSDs [46,47,48]. The increased concentrations of the inflammatory markers may induce sensitization of the peripheral nociceptors [49] that cause increased pain sensitivity and thereby the subjects report higher pain intensity. The aim of the inflammatory process is to remove the initiating stimulus that causes the injury in the tissue, but when the body is affected by the unfavorable posture, awkward work positions, and prolonged static force as for the FLTOs, and is exposed to repeated bouts of damage, it may affect and hinder the healing process and subjects develop chronic work-related muscle pain because of the presence of a continuously low-grade inflammation [50]. In a rat model, Barr et al. [43] showed that a localized injury caused by exposure to a highly repetitive forelimb-intensive task induces a systemic inflammatory response. This finding in the animal study can be translated to humans showing that the FLTOs’ exposure to awkward work positions has caused tissue injury that can be measured as inflammation in the blood.

5 Conclusion

The profile of self-reported health, pain intensity, sensitivity, and inflammatory proteins in the blood can discriminate FLTOs with pain from CONs. This study contributes to the literature by providing the first report on the use of self-reported physiological measures and objective measurements of inflammatory biomarkers to understand the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying work-related neck and shoulder pain in the working population.

-

Research ethics: Research involving human subjects complied with all relevant national regulations, institutional policies and is in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration (as amended in 2013) and has been approved by the authors’ Institutional Review Board of the University of Linköping, Sweden (Dnr: 2013/418-31; Dnr: 2016/477-32).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas, took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

-

Competing interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council of southeastern Sweden (FORSS) and ALF Grants, Region Ostergotland.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated and/or analysed in this study are not publicly available as the Ethical Review Board has not approved the public availability of these data.

-

Supplementary Material: This article contains supplementary material (followed by the link to the article online).

-

Artificial intelligence/Machine learning tools: Not applicable.

References

[1] Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D, Buchbinder R, Mansournia MA, Bettampadi D, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neck pain in the general population, 1990-2017: systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Bmj. 2020;368:m791.10.1136/bmj.m791Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Rolander B, Lindmark U, Johnston V, Wagman P, Wåhlin C. Organizational types in relation to exposure at work and sickness – a repeated cross-sectional study within public dentistry. Acta Odontol Scand. 2020;78(2):132–40.10.1080/00016357.2019.1659411Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Larsson B, Søgaard K, Rosendal L. Work related neck-shoulder pain: a review on magnitude, risk factors, biochemical characteristics, clinical picture and preventive interventions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):447–63.10.1016/j.berh.2007.02.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Etana G, Ayele M, Abdissa D, Gerbi A. Prevalence of work related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among bank staff in jimma city, southwest ethiopia, 2019: an institution-based cross-sectional study. J Pain Res. 2021;14:2071–82.10.2147/JPR.S299680Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Côté P, Carragee EJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(4 Suppl):S14–23.10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643efbSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Andersen LL, Hansen K, Mortensen OS, Zebis MK. Prevalence and anatomical location of muscle tenderness in adults with nonspecific neck/shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2011;12:169.10.1186/1471-2474-12-169Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Juul-Kristensen B, Kadefors R, Hansen K, Byström P, Sandsjö L, Sjøgaard G. Clinical signs and physical function in neck and upper extremities among elderly female computer users: the NEW study. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;96(2):136–45.10.1007/s00421-004-1220-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Christensen JO, Knardahl S. Work and neck pain: A prospective study of psychological, social, and mechanical risk factors. Pain. 2010;151(1):162–73.10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Flodin U, Rolander B, Löfgren H, Krapi B, Nyqvist F, Wåhlin C. Risk factors for neck pain among forklift truck operators: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2018;19(1):44.10.1186/s12891-018-1956-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Rolander B, Forsman M, Ghafouri B, Abtahi F, Wåhlin C. Measurements and observations of movements at work for warehouse forklift truck operators. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2022;28(3):1840–8.10.1080/10803548.2021.1943866Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Gerdle B, Hilgenfeldt U, Larsson B, Kristiansen J, Søgaard K, Rosendal L. Bradykinin and kallidin levels in the trapezius muscle in patients with work-related trapezius myalgia, in patients with whiplash associated pain, and in healthy controls – A microdialysis study of women. Pain. 2008;139(3):578–87.10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Flodgren GM, Crenshaw AG, Alfredson H, Fahlström M, Hellström FB, Bronemo L, et al. Glutamate and prostaglandin E2 in the trapezius muscle of female subjects with chronic muscle pain and controls determined by microdialysis. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):511–5.10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Shook MA. Chronic work-related myalgia: neuromuscular mechanisms behind work-related chronic muscle pain syndromes. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 2008;16(3):241–2.10.1080/10582450802162265Search in Google Scholar

[14] Larsson B, Rosendal L, Kristiansen J, Sjøgaard G, Søgaard K, Ghafouri B, et al. Responses of algesic and metabolic substances to 8 h of repetitive manual work in myalgic human trapezius muscle. Pain. 2008;140(3):479–90.10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Carp SJ, Barbe MF, Winter KA, Amin M, Barr AE. Inflammatory biomarkers increase with severity of upper-extremity overuse disorders. Clin Sci (Lond). 2007;112(5):305–14.10.1042/CS20060050Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Rechardt M, Shiri R, Matikainen S, Viikari-Juntura E, Karppinen J, Alenius H. Soluble IL-1RII and IL-18 are associated with incipient upper extremity soft tissue disorders. Cytokine. 2011;54(2):149–53.10.1016/j.cyto.2011.02.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Teodorczyk-Injeyan JA, Triano JJ, McGregor M, Woodhouse L, Injeyan HS. Elevated production of inflammatory mediators including nociceptive chemokines in patients with neck pain: a cross-sectional evaluation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2011;34(8):498–505.10.1016/j.jmpt.2011.08.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Barbe MF, Barr AE. Inflammation and the pathophysiology of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20(5):423–9.10.1016/j.bbi.2006.03.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Wheelock ÅM. Trials and tribulations of ‘omics data analysis: assessing quality of SIMCA-based multivariate models using examples from pulmonary medicine. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9(11):2589–96.10.1039/c3mb70194hSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Crawford JO. The nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire. Occup Med. 2007;57(4):300–1.10.1093/occmed/kqm036Search in Google Scholar

[21] Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77.10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Burckhardt CS, Archenholtz B, Bjelle A. Measuring the Quality of life of women with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus: a swedish version of the quality of life scale (QOLS). Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21(4):190–5.10.3109/03009749209099220Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Sjörs A, Larsson B, Persson AL, Gerdle B. An increased response to experimental muscle pain is related to psychological status in women with chronic non-traumatic neck-shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2011;12:230.10.1186/1471-2474-12-230Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Olausson P, Gerdle B, Ghafouri N, Sjöström D, Blixt E, Ghafouri B. Protein alterations in women with chronic widespread pain--An explorative proteomic study of the trapezius muscle. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11894.10.1038/srep11894Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Gold JE, Punnett L, Katz JN. Pressure pain thresholds and musculoskeletal morbidity in automobile manufacturing workers. Int Arch Occup Env Health. 2006;79(2):128–34.10.1007/s00420-005-0005-3Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Schenk P, Laeubli T, Klipstein A. Validity of pressure pain thresholds in female workers with and without recurrent low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(2):267–75.10.1007/s00586-006-0124-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Hägg GM, Åström A. Load pattern and pressure pain threshold in the upper trapezius muscle and psychosocial factors in medical secretaries with and without shoulder/neck disorders. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1997;69(6):423–32.10.1007/s004200050170Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Binderup AT, Holtermann A, Søgaard K, Madeleine P. Pressure pain sensitivity maps, self-reported musculoskeletal disorders and sickness absence among cleaners. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84(6):647–54.10.1007/s00420-011-0627-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Nunes AMP, Moita J, Espanha M, Petersen KK, Arendt-Nielsen L. Pressure pain thresholds in office workers with chronic neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Pract. 2021;21(7):799–814.10.1111/papr.13014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(3):285–323.10.1002/ajim.20750Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Meng W, Chan BW, Harris C, Freidin MB, Hebert HL, Adams MJ, et al. A genome-wide association study finds genetic variants associated with neck or shoulder pain in UK Biobank. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(8):1396–404.10.1093/hmg/ddaa058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Blaschke S, Schulz H, Schwarz G, Blaschke V, Müller GA, Reuss-Borst M. Interleukin 16 expression in relation to disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):12–21.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Maione F. Commentary: IL-17 in Chronic Inflammation: From Discovery to Targeting. Front Pharmacology. 2016;7:250.10.3389/fphar.2016.00250Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Jiang X, Zhou R, Zhang Y, Zhu T, Li Q, Zhang W. Interleukin-17 as a potential therapeutic target for chronic pain. Front Immunol. 2022;13:999407.10.3389/fimmu.2022.999407Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Richter F, Natura G, Ebbinghaus M, von Banchet GS, Hensellek S, König C, et al. Interleukin-17 sensitizes joint nociceptors to mechanical stimuli and contributes to arthritic pain through neuronal interleukin-17 receptors in rodents. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):4125–34.10.1002/art.37695Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Sarkar S, Justa S, Brucks M, Endres J, Fox DA, Zhou X, et al. Interleukin (IL)-17A, F and AF in inflammation: a study in collagen-induced arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177(3):652–61.10.1111/cei.12376Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Li JK, Nie L, Zhao YP, Zhang YQ, Wang X, Wang SS, et al. IL-17 mediates inflammatory reactions via p38/c-Fos and JNK/c-Jun activation in an AP-1-dependent manner in human nucleus pulposus cells. J Transl Med. 2016;14:77.10.1186/s12967-016-0833-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Kim CF, Moalem-Taylor G. Interleukin-17 contributes to neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury in mice. J Pain. 2011;12(3):370–83.10.1016/j.jpain.2010.08.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[40] Huo W, Liu Y, Lei Y, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Mao Y, et al. Imbalanced spinal infiltration of Th17/Treg cells contributes to bone cancer pain via promoting microglial activation. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;79:139–51.10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.024Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Cheng L, Fan W, Liu B, Wang X, Nie L. Th17 lymphocyte levels are higher in patients with ruptured than non-ruptured lumbar discs, and are correlated with pain intensity. Injury. 2013;44(12):1805–10.10.1016/j.injury.2013.04.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Marchand F, Perretti M, McMahon SB. Role of the immune system in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(7):521–32.10.1038/nrn1700Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Barr AE, Barbe MF, Clark BD. Systemic inflammatory mediators contribute to widespread effects in work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(4):135–42.10.1097/00003677-200410000-00003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Dong Y, Jiang P, Jin X, Jiang N, Huang W, Peng Y, et al. Association between long-term static postures exposure and musculoskeletal disorders among university employees: A viewpoint of inflammatory pathways. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1055374.10.3389/fpubh.2022.1055374Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Kivioja J, Rinaldi L, Ozenci V, Kouwenhoven M, Kostulas N, Lindgren U, et al. Chemokines and their receptors in whiplash injury: elevated RANTES and CCR-5. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21(4):272–7.10.1023/A:1010931309088Search in Google Scholar

[46] Farrell SF, de Zoete R, Cabot PJ, Sterling M. Systemic inflammatory markers in neck pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(9):1666–86.10.1002/ejp.1630Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Matute Wilander A, Kåredal M, Axmon A, Nordander C. Inflammatory biomarkers in serum in subjects with and without work related neck/shoulder complaints. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:103.10.1186/1471-2474-15-103Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Barbe MF, Gallagher S, Popoff SN. Serum biomarkers as predictors of stage of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. JAAOS – J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:10–6.10.5435/JAAOS-21-10-644Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Milligan ED, Maier SF. “Listening” and “talking” to neurons: implications of immune activation for pain control and increasing the efficacy of opioids. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56(1):148–69.10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Barr AE, Barbe MF. Inflammation reduces physiological tissue tolerance in the development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2004;14(1):77–85.10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial Comment

- From pain to relief: Exploring the consistency of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Christmas greetings 2024 from the Editor-in-Chief

- Original Articles

- The Scandinavian Society for the Study of Pain 2022 Postgraduate Course and Annual Scientific (SASP 2022) Meeting 12th to 14th October at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

- Comparison of ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block versus continuous paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing proximal femur surgeries

- Clinical Pain Researches

- The effect of tourniquet use on postoperative opioid consumption after ankle fracture surgery – a retrospective cohort study

- Changes in pain, daily occupations, lifestyle, and health following an occupational therapy lifestyle intervention: a secondary analysis from a feasibility study in patients with chronic high-impact pain

- Tonic cuff pressure pain sensitivity in chronic pain patients and its relation to self-reported physical activity

- Reliability, construct validity, and factorial structure of a Swedish version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS) in patients with chronic pain

- Hurdles and potentials when implementing internet-delivered Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: a retrospective appraisal using the Quality implementation framework

- Exploring the outcome “days with bothersome pain” and its association with pain intensity, disability, and quality of life

- Fatigue and cognitive fatigability in patients with chronic pain

- The Swedish version of the pain self-efficacy questionnaire short form, PSEQ-2SV: Cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation in a population of patients with musculoskeletal disorders

- Pain coping and catastrophizing in youth with and without cerebral palsy

- Neuropathic pain after surgery – A clinical validation study and assessment of accuracy measures of the 5-item NeuPPS scale

- Translation, contextual adaptation, and reliability of the Danish Concept of Pain Inventory (COPI-Adult (DK)) – A self-reported outcome measure

- Cosmetic surgery and associated chronic postsurgical pain: A cross-sectional study from Norway

- The association of hemodynamic parameters and clinical demographic variables with acute postoperative pain in female oncological breast surgery patients: A retrospective cohort study

- Healthcare professionals’ experiences of interdisciplinary collaboration in pain centres – A qualitative study

- Effects of deep brain stimulation and verbal suggestions on pain in Parkinson’s disease

- Painful differences between different pain scale assessments: The outcome of assessed pain is a matter of the choices of scale and statistics

- Prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia according to three fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria: A secondary analysis study

- Sex moderates the association between quantitative sensory testing and acute and chronic pain after total knee/hip arthroplasty

- Tramadol-paracetamol for postoperative pain after spine surgery – A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study

- Cancer-related pain experienced in daily life is difficult to communicate and to manage – for patients and for professionals

- Making sense of pain in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): A qualitative study

- Patient-reported pain, satisfaction, adverse effects, and deviations from ambulatory surgery pain medication

- Does pain influence cognitive performance in patients with mild traumatic brain injury?

- Hypocapnia in women with fibromyalgia

- Application of ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral block or intercostal nerve block for acute herpes zoster and prevention of post-herpetic neuralgia: A case–control retrospective trial

- Translation and examination of construct validity of the Danish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia

- A positive scratch collapse test in anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome indicates its neuropathic character

- ADHD-pain: Characteristics of chronic pain and association with muscular dysregulation in adults with ADHD

- The relationship between changes in pain intensity and functional disability in persistent disabling low back pain during a course of cognitive functional therapy

- Intrathecal pain treatment for severe pain in patients with terminal cancer: A retrospective analysis of treatment-related complications and side effects

- Psychometric evaluation of the Danish version of the Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire in patients with subacute and chronic low back pain

- Dimensionality, reliability, and validity of the Finnish version of the pain catastrophizing scale in chronic low back pain

- To speak or not to speak? A secondary data analysis to further explore the context-insensitive avoidance scale

- Pain catastrophizing levels differentiate between common diseases with pain: HIV, fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome, and breast cancer survivors

- Prevalence of substance use disorder diagnoses in patients with chronic pain receiving reimbursed opioids: An epidemiological study of four Norwegian health registries

- Pain perception while listening to thrash heavy metal vs relaxing music at a heavy metal festival – the CoPainHell study – a factorial randomized non-blinded crossover trial

- Observational Studies

- Cutaneous nerve biopsy in patients with symptoms of small fiber neuropathy: a retrospective study

- The incidence of post cholecystectomy pain (PCP) syndrome at 12 months following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation in 200 patients

- Associations between psychological flexibility and daily functioning in endometriosis-related pain

- Relationship between perfectionism, overactivity, pain severity, and pain interference in individuals with chronic pain: A cross-lagged panel model analysis

- Access to psychological treatment for chronic cancer-related pain in Sweden

- Validation of the Danish version of the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain

- Associations between cognitive test scores and pain tolerance: The Tromsø study

- Healthcare experiences of fibromyalgia patients and their associations with satisfaction and pain relief. A patient survey

- Video interpretation in a medical spine clinic: A descriptive study of a diverse population and intervention

- Role of history of traumatic life experiences in current psychosomatic manifestations

- Social determinants of health in adults with whiplash associated disorders

- Which patients with chronic low back pain respond favorably to multidisciplinary rehabilitation? A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial

- A preliminary examination of the effects of childhood abuse and resilience on pain and physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis

- Differences in risk factors for flare-ups in patients with lumbar radicular pain may depend on the definition of flare

- Real-world evidence evaluation on consumer experience and prescription journey of diclofenac gel in Sweden

- Patient characteristics in relation to opioid exposure in a chronic non-cancer pain population

- Topical Reviews

- Bridging the translational gap: adenosine as a modulator of neuropathic pain in preclinical models and humans

- What do we know about Indigenous Peoples with low back pain around the world? A topical review

- The “future” pain clinician: Competencies needed to provide psychologically informed care

- Systematic Reviews

- Pain management for persistent pain post radiotherapy in head and neck cancers: systematic review

- High-frequency, high-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation compared with opioids for pain relief after gynecological surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free adults and adults with musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review

- Noninvasive transcranial brain stimulation in central post-stroke pain: A systematic review

- Short Communications

- Are we missing the opioid consumption in low- and middle-income countries?

- Association between self-reported pain severity and characteristics of United States adults (age ≥50 years) who used opioids

- Could generative artificial intelligence replace fieldwork in pain research?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increases

- Original Experimental

- Confirmatory study of the usefulness of quantum molecular resonance and microdissectomy for the treatment of lumbar radiculopathy in a prospective cohort at 6 months follow-up

- Pain catastrophizing in the elderly: An experimental pain study

- Improving general practice management of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: Interdisciplinarity, coherence, and concerns

- Concurrent validity of dynamic bedside quantitative sensory testing paradigms in breast cancer survivors with persistent pain

- Transcranial direct current stimulation is more effective than pregabalin in controlling nociceptive and anxiety-like behaviors in a rat fibromyalgia-like model

- Paradox pain sensitivity using cuff pressure or algometer testing in patients with hemophilia

- Physical activity with person-centered guidance supported by a digital platform or with telephone follow-up for persons with chronic widespread pain: Health economic considerations along a randomized controlled trial

- Measuring pain intensity through physical interaction in an experimental model of cold-induced pain: A method comparison study

- Pharmacological treatment of pain in Swedish nursing homes: Prevalence and associations with cognitive impairment and depressive mood

- Neck and shoulder pain and inflammatory biomarkers in plasma among forklift truck operators – A case–control study

- The effect of social exclusion on pain perception and heart rate variability in healthy controls and somatoform pain patients

- Revisiting opioid toxicity: Cellular effects of six commonly used opioids

- Letter to the Editor

- Post cholecystectomy pain syndrome: Letter to Editor

- Response to the Letter by Prof Bordoni

- Response – Reliability and measurement error of exercise-induced hypoalgesia

- Is the skin conductance algesimeter index influenced by temperature?

- Skin conductance algesimeter is unreliable during sudden perioperative temperature increase

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to “Chronic post-thoracotomy pain after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study of preoperative risk factors”

- Obituary

- A Significant Voice in Pain Research Björn Gerdle in Memoriam (1953–2024)